by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 11, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Botswana government resettlement camps are poorly supplied, and diseases like HIV/AIDS are rife. © Fiona Watson/Survival International

By Survival International

Survival International has launched a campaign calling for an end to a draconian system in Botswana which has broken Bushmen families apart and denied them access to their land. Critics such as veteran anti-apartheid activist Michael Dingake have compared the system to the apartheid-era pass laws.

The call comes in the fiftieth anniversary year of Botswana’s independence.

After having been brutally evicted and forced into government camps between 1997 and 2002, the Bushmen won a historic court victory in 2006 recognizing their right to live on their land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

Since then, however, this right has only been extended to the small number of Bushmen named in court papers. Their children and close relatives are forced to apply for permits just to visit them, or risk seven years in prison, and children born and brought up in the reserve have to apply for a permit when they turn 18. Many fear that once the current generation has passed away, the Bushmen will be shut out of their land forever.

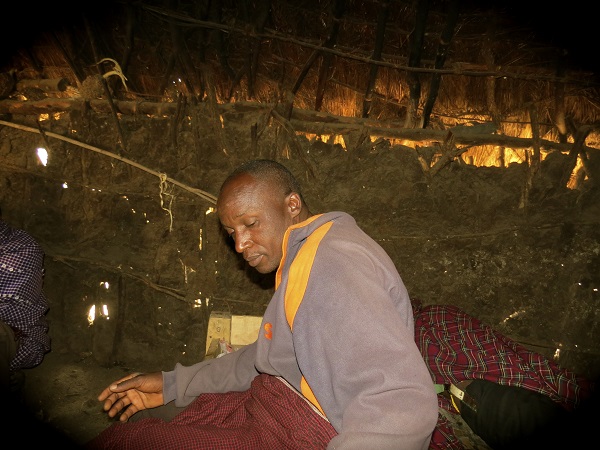

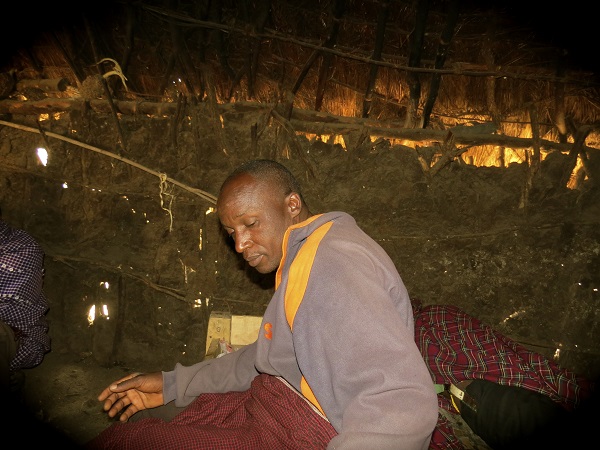

Most Bushmen are still forced to live in government resettlement camps, rather than on their land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve

© Dominick Tyler

On the subject of the fiftieth anniversary, one Bushman told Survival: “I don’t even know anything about these celebrations. They are doing this so that people will not think they are a bad government. They are celebrating; we are not. We’re still feeling the same way. They’ve been celebrating for the last 49 years.”

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “The Botswana government has viciously persecuted the Bushmen for decades, first with violent evictions and then with a permit system designed to break families apart. If Botswana still wants to be seen as a “shining light” of democracy in Africa, it needs to listen to the Bushmen, uphold its own court’s ruling and end this appallingly unjust restriction on the Bushmen’s right to live on their ancestral land in the Central Kalahari reserve. I hope that this historic year will mark the end of the decades long persecution of the Bushmen.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 16, 2016 | Lobbying

Featured image: The Baka have lived sustainably in the central African rainforest for generations as hunter-gatherers

© Selcen Kucukustel/Atlas

By Survival International

Survival International has launched a formal complaint about the activities of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in Cameroon.

This is the first time a conservation organization has been the subject of a complaint to the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), using a procedure more normally invoked against multinational corporations. Survival International has launched a formal complaint about the activities of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in Cameroon.

The complaint charges WWF with involvement in violent abuse and land theft against Baka “Pygmies” in Cameroon, carried out by anti-poaching squads which it in part funds and equips.

Before beginning its work in Cameroon, WWF failed to consider what impact it would have on the Baka. As a result, WWF has contributed to serious human rights violations and broken the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It supports conservation zones on Baka land, to which the Baka are denied access, as well as the anti-poaching squads that have violently abused Baka men and women, and other rainforest tribes, for well over a decade.

Forced out of the forest, many Baka communities complain of a serious decline in their health. Living on the roadside, they are increasingly exposed to malaria and other diseases.

© Survival International

The international conservation organization has thereby violated both OECD human rights guidelines and its own policy on indigenous peoples, and Survival’s legal team has therefore submitted a formal complaint.

Baka have repeatedly testified to Survival about the activities of these anti-poaching squads in the region. In 2015 one Baka man said: “When they came to beat me here in my home, my wife and I were sleeping. They beat me with machetes. They beat my wife with machetes.”

Survival International is calling for a new approach to conservation that respects tribal peoples’ rights. Tribal peoples have been dependent on and managed their environments for millennia. Despite this, big conservation organizations are partnering with industry and tourism and destroying the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world – tribes. They are the environment’s best allies, and should be at the centre of conservation policy.“They are letting the elephants die out in the forest at the same time as they are stopping us from eating,” another Baka man told Survival. Today, the destruction of Baka land through logging, mining and the trafficking of wildlife continues, provoking concern among tribespeople that their land is being destroyed, even as they are denied access to large parts of it in the name of conservation.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said today: “WWF knows that the men its supporters fund for conservation work repeatedly abuse, and even torture, the Baka, whose land has been stolen for conservation zones. It hasn’t stopped them, and it treats criticism as something to be countered with yet more public relations. It calls on companies to stick to the same OECD guidelines it routinely violates itself. Both conservation and development have been allowed to trump human rights for decades and millions of people in Africa and Asia have suffered as a result. It’s time the big conservation organizations got their act together. If WWF really can’t stop the guards it funds in Cameroon from attacking Baka, then perhaps it should be asking itself if it has any right to be there at all.”

Survival International is the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights. We help tribal people defend their lives, protect their lands and determine their own futures. Founded in 1969.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 1, 2016 | Agriculture, Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Two Anuak women in the Gambella Province of Ethiopia. By Julio Garcia on March 18, 2007.

By Cultural Survival

On December 28, 2015 Ethiopia’s Agricultural Ministry revoked their contract with Karuturi Global Limited, an Indian company who in 2010 won a concession for 100,000 hectares of land to be developed for industrial agriculture for export in the Gambella region of southern Ethiopia, home to the Indigenous Anuak, Mezenger, Nuer, Opo, and Komo peoples. The Agricultural Ministry’s land investment agency cancelled the concession on the grounds that by 2012 Karuturi had developed only 1,200 hectares of land within the initial two year period of the contract.

Since 2013 the company began spiraling out of control, when it was found guilty of tax evasion in in a similar land grab venture in Kenya, and the following year had its operations was taken over by Stanbic Bank.

Karaturi’s Managing Director Sai Ramakrishna has challenged the Agricultural Ministry’s project termination in Ethiopia, telling Bloomberg Business, “I don’t recognize this cancellation,” and is seeking arbitration. If international arbitration is granted, Karuturi will advocate for the continuation of the company’s commercial agriculture plan. Ethiopian officials have dismissed their claims.

Karuturi Global’s project failure resembles that of many foreign investors who have purchased land under the Ethiopian government’s push to lease Indigenous lands to foreign investors, in what many term “land grabbing.” According to Bloomberg, none of these farms in Ethiopia have reported any success in exporting crops.

Ethiopia’s land leasing plans were described as a roadmap to development. Called “villagisation,” the plan involved removing the Indigenous Peoples who sustain themselves from their lands practising farming, hunting, gathering, and pastoralism, and grouping them into established villages, with the idea that the land would be used to produce large scale industrial agriculture to sustain the population’s food needs. Jobs would be created, turning Indigenous Peoples into wage workers who could then buy foods. But Karaturi’s plans were different–aiming to export grains for sale abroad rather than selling them locally, despite Ethiopia’s ban on the export of cereal crops.

The socio-economic transformation promised by the regional government was never realized. Rather, villagisation has meant the forced removal of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands and the creation of an aid-dependant food source. Obang Metho, Anuak human rights activist from Gambella, explained in a video with local media Ethiopian Satellite Television, “This was not empty land. People have been living on this land for generations. When I grew up we didn’t have an office job to earn wages, people depend on land. Our supermarket is going to the field. The field was our bank. When you take away our lands, you are taking away our livelihood, our futures.”

An aerial view of the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya where many Anuak people turned to for shelter after forced removal from Gambella. Photograph taken on November 1, 2011 by Oxfam International

On a morning in late 2010 the Anuak peoples living in the province of Gambella were met by regional government officials and soldiers. Without their knowledge or consent the Ethiopian government had sold an estimated 42% of Anuak land to foreign investors. The Anuak people were forced to leave their only known livelihoods, including essential food sources, and move to government sponsored “villages” which soon turned into refugee camps. In 2012, Human Rights Watch published its report, “’Waiting Here for Death’ Forced Displacement and “Villagization” in Ethiopia’s Gambella Region” documenting the “forcible moving tens of thousands of indigenous people in the western Gambella region from their homes to new villages under a ‘villagization’ program.”

“In their old village there was a school under a mango tree. In the new village, donor money had paid for a new school building. The children, however, were too hungry to attend, roaming instead in the forest looking for food… but now the government can show the world there is a ‘school’” –Anuak refugee displaced to the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya (from The Guardian’s article, Ethiopia’s rights abuses ‘being ignored by US and UK aid agencies’.)

Since their displacement in 2010 the Anuak have become refugees – many having turned to the crowded refugee camps in South Sudan and Kenya. As a result of their forced displacement many of the Anuak, and other Indigenous Peoples of the southwest, have endured scores of human rights violations including documented cases of rape, torture, extrajudicial imprisonment and famine, while these conditions were ignored by donor agencies USAID and DfiD.

Now, Ethiopia, USAID and Dfid have a chance to right their wrongs, and return the lands to the Indigenous Peoples turned into development refugees. But the Agriculture Ministry has said that the rest of the land will return to a “land bank” for future re-investment.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples clearly states in Article 28.1

Indigenous peoples have the right to redress, by means that can include restitution or, when this is not possible, just, fair and equitable compensation, for the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used, and which have been confiscated, taken, occupied, used or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent.

For the survival of the Indigenous Peoples of Gambella, International aid agencies must take an active role to bring these displaced communities access to lands and a means of sustainable livelihoods.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 10, 2016 | Agriculture, Colonialism & Conquest

By Mary Louisa Cappelli, PhD, JD / Globalmother.org

Featured image: Barabaig pastoralist

Katesh — After a fifty-year struggle against land grabbing by foreign agribusiness corporations, nomadic pastoralists in the Hanang District of Eastern Tanzania have finally won Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy pursuant to the 1999 Land Act No. 5. With legal assistance from The Ujamaa Community Resource Team, The Barabaig and Masai in the villages of Mureru, Mogitu, Dirma, Gehandu and Miyng’enyi now have much needed access to approximately 5,500 hectares of grazing land for their cattle.

While several villages have benefited from the decision to enforce the 1990 Land Act No. 5, the Barabaig of the Basuto Plains have not been recognized in the latest issuance of Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy. The Barabaig have been engaged in a fifty-year struggle to maintain their cultural integrity against the jurisprudent land policies of privatization and villagization, which have systematically suspended their constitutional rights and legal protections. The powerful infiltration of neoliberal forces culminating in land and resource grabbing has fashioned a geographical landscape of displaced indigenous peoples struggling to restructure their lives in uninhabitable terrain that supports relatively few life forms. While recording mythohistories amongst the Barabaig women, I have had the opportunity to witness first hand how the Barabaig have resisted globalizing forces that have pushed them to the farthest regions of the Basuto Plains.

Barabaig drinking from what remains of sole water source

Land Policy

The restructuring of socio-geographic areas in the interest of globalization has been most visible in the legal system in regards to land policy jurisprudence and administration, demonstrating how global discourse circulates in such a powerful system as to suspend constitutional rights and protections of the Barabaig Peoples. For many years, first President of the United Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere’s philosophy on land holdings has shaped Tanzanian land policy. Rejecting the commoditization of land, Nyerere believed land was God’s gift to humanity and therefore could not be privatized. In his discussion of land holdings, he argues:

This land is not mine, but the efforts made by me in clearing that land enable me to lay claim of ownership over the cleared piece of ground. But it is not really the land itself that belongs to me but only the cleared ground, which will remain mine as long as I continue to work on it. By clearing that ground I have actually added to its value and have enabled it to be used to satisfy a human need. Whoever then takes this piece of ground must pay me for adding value to it through clearing it by my own labour. (Nyerere 1966)

This philosophy treats land as a fundamental right of human needs and not as commodity. This sentiment is further expressed in “The Nyerere Doctrine of Land Value” in the case of Attorney- General v. Lohay Akonaay and Another (Sabine 1964). [i] Accordingly, it is the public who possess land rights and an individual has a right to occupancy to use the common land belonging to the public. The duration of the Right to Occupancy can last from anywhere between 33 to 99 years depending on location and usage. The 1923 Land Ordinance of 1923 to 1999 referred to this title as a Deemed Right of Occupancy, based on occupation to confer ownership. “The majority of the people living in the rural areas—and who form more that 80% of the population of Tanzania hold their land under this system” (Peter 2007).

Today, President John Magufuli is the trustee of Tanzanian public lands and it is Magufuli who has the power and authority to decide what is in the public’s interest in terms of land decisions. Magufuli holds the power to “repossess land on behalf of the public for construction of roads, schools, hospitals etc.” (Peter 2007). Land can and has been taken from indigenous peoples without compensation for the land. In return the occupier is compensated for unexhausted improvements to the land, including houses, structures, crops; however, the occupier is not compensated for the land itself.

Legal Decisions Support Agribusiness Ventures

The implementation of the commoditization of land and resources can be seen in the 1960 decision to cultivate wheat in the Arusha Region of Hanang District. The United Republic of Tanzania along with the Canadian Food Aid Programme launched the Basotu Wheat Complex securing ten thousand acres of Barabaig land for wheat farming. In 1970, the National Agriculture and Food Corporation (NAFCO) expanded the project developing several large scale wheat farms securing 120,000 hectares of Barabaig pasture land, including homesteads, water sources, sacred burial grounds, and wild life.

Sadly, many Barabaig were unaware of the legal maneuvering for their land and first found out about it when tractors ploughed through their homesteads. According to reports and interviews, NAFCO failed to give due process to people living on their land at the time and were deemed to be trespassers on their own property. Chief Daniel recalls how he was jostled from sleep and ordered to leave. “We were forced off our own land by gunpoint,” he said.

A girgwagedgademga (council of women) with Chief Daniel

In the 1981 Case of National Agricultural and Food Corporation v. Mulbadaw Village Council and Others, the Barabaig sought legal protection and sued the National Agricultural and Food Corporation (NAFCO) for trespass on their land at the High Court of Tanzania in Arusha. While the High Court of Tanzania (D`Souza, Ag. J.) ruled in favor of the Barabaig Plaintiffs, stating that the Barabaig occupied land under customary title, the Court of Appeal of Tanzania overturned the decision and ruled in favor of NAFCO stating that, “The Plaintiffs/Respondents – Mulbadaw Village Council did not own the land in dispute or part of it because they did not produce any evidence to the effect of any allocation of the said land in dispute by the District Development Council as required by the Villages and Ujamaa Villages Act of 1975” (Peter 2007). In effect, the Village Council had trespassed by entering their own traditional lands, the Court of Appeals ruling that the villagers failed to meet the burden of proof that they were natives within the meaning of the law.

Legal analysis of case precedence is evidence that the Tanzanian government discounted Barabaig collective customary rights, discounted Barabaig tripartite land holding practices, ignored detrimental ecological effects derived from alienation of pastoral lands, and moreover privileged the privatization and commodification of land and foreign and national interests over local indigenous rights. Political power backed by powerful interest groups proved in this case study that power is not the same as law and that in the world of nation-states, placelessness and dispossession is a political byproduct of globalization.

In 1987, Tanzania, submitting to pressure to follow “global norms of behaviour,” decreed the Extinction of Customary Land Right Order. This extinguished land occupation under customary law, precluding Barabaig from exercising customary land rights protection (Larson and Aminzade 2009). Subsequently, when the Barabaig migrated during dry seasons, they left their lands with little evidence of occupancy, resulting in encroachment by external forces. The government began the process of Villagization, whereby the Barabaig were given portions of unused land deemed unsuitable for commercial purposes with little water resources. The Barabaig were subsequently settled (land-locked) in villages. The Villagization of the Barabaig drastically interfered with customary land practices, nomadic land use patterns, and livestock herding traditions.

According to Shivjii Chairman of the Presidential Commission of Enquiry into Land Matters, the movement of people into villages was achieved with “little regard to existing land tenure systems and the culture and custom in which they are rooted” (2007). The Barabaig surrendered their traditional migratory herding strategies and were forced to graze their cattle in a migratory cycle marked by a restricted one-day distance from their homestead. The concentration of livestock on this pattern of limited grazing has adversely impacted its ecosystems resulting in a “decline of levels of pastoral production and welfare” (Peter 2007).

Mama Paulina and widow

The Land Tenure reform is based on the premise that indigenous land tenure systems act as an obstruction to development and that more formal registered land title will encourage rural land users to make investments to improve their land investments through the provision of credit. The Tanzanian administrative structure grants each village a statutory title to land and further argues that granting titles and providing credit for land improvements will thwart encroachment by external forces; however, under the Customary Land Ordinance this has led to the holding of double titles leading to further complications of legality of ownership. The Barabaig case provides contrary evidence demonstrating that both objectives have failed to ward off encroachment by outsiders to enclose land for crop cultivation.

In addition, Land Use Appropriation by Foreign interests have interfered with traditional migratory patterns to water sources, denying Barabaig access to water during the dry seasons. Traditionally, Barabaig herders migrated eastward out of the village in the dry season to gain access to permanent water sources on the shores of Lake Balangda Lelu. The land allocation plans fail to recognize the indigenous needs of water sources; moreover, these allocations do not take into account the complexity of the traditional land use patterns in and beyond village boundaries. Because the Barabaig follow an animistic belief system that recognizes the interdependency and reverence of all life forms, displacement from their land and ancestral gravesites disrupts their sacred patterns of worship and traditional ways of being and living in the world.

The Barabaig were unaware of the Land Use Planning Provisions at the time and hence did not object to them because they did not realize how it would limit their migratory grazing patterns and obstruct their traditional livelihoods. According to Barabaig Chief Leader Daniel, plans were purposefully “ambiguous” and unclear with little account taken of their pastoral economy. Facing starvation, many pastoralists experienced a sense of cultural, spiritual and economic placelessness, and have been forced to give up their livelihood and migrate to squatter settlement areas in Arusha or Dar es Salam. “They fill the perio-urban shanties to eke out a living as best they can in the informal economy or become burdens of the state as the industrial and commercial sectors have no capacity to absorb more workers” (Lane 1990).

The issuance of Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy provides a temporary legal tourniquet against the inhumane assault on indigenous livelihoods. According to Attorney Edward Ole Lekaita from The Ujamaa Community Resource Team in the Arusha District, efforts have begun once again to take up the legal gamut to secure customary title deeds for the Barabaig of the Basuto plains.

About the author: An interdisciplinary ethnographer, Mary Louisa Cappelli is a graduate of USC, UCLA, and Loyola Law School whose research focuses on how indigenous peoples of the global South struggle to hold onto their cultural traditions and ways of life amidst encroaching capital and globalizing forces. She previously taught in the Interdisciplinary Program at Emerson College and is the director of Globalmother.org, a Tanzanian WNGO, which engages in participatory action research and legislative advocacy in Africa and Central America.

References:

Aminzade, R. and Larson, E. “Nation-building in post-colonial nation-states: the cases of Tanzania and Fiji.” International Social Science Journal Vl. 59: (2009):1468-2451.

Lane, R. Charles. “Barabaig Natural Resource Management: Sustainable Land use under Threat of Destruction.” United Nations Research Institute for Social Development Discussion. Discussion Paper (1990): No 12.

Nyerere, J. K. Freedom and Unity: A Selection from Writings and Speeches

1952-1965. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Peter, Maina, Chris. “Human Rights of Indigenous Minorities in Tanzania and the Court of Law.” Journal of Group and Minority Rights, 2007.

Sabine, G. H. A History of Political Theory, London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, (1964): 527-528.