Instead, what we usually hear from international conservation organizations is that parks, game reserves and other kinds of protected areas are the most important conservation success story and should be extended, improved, and strengthened worldwide. Recent research that provided a preamble to the November 2014 World Parks Congress, for instance, argued similarly that “protected areas are core to the future of life on our planet”, requiring larger coverage, representation and better management and funding[2]. Such assertions require reflection.

It is true that, in many cases, protected areas are allowing critical species and ecosystems to persist, and in this way they provide a cushion of hope in our ability to preserve some of the world’s remaining natural wealth. Biodiversity is often higher inside of protected areas than outside[3]. They can provide opportunities for improving health and well-being, support human life through invaluable environmental services, and offer opportunities for new forms of economic development and financial mechanisms, including through tourism, payments for ecosystem services, offsets, and bioprospecting. Yet the strategy based on protected areas, which defines conservation success in terms of spatial control, fails to tackle the most significant challenges to preserving biodiversity.

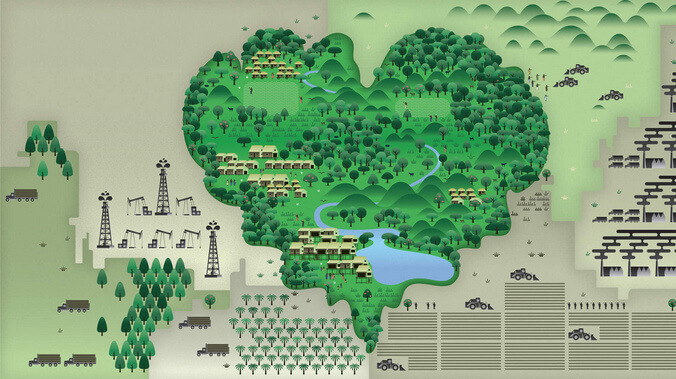

The celebration of protected areas hides ways in which the perpetuation of exclusionary conservation in many countries does not protect against so-called “development” so much as it mirrors it, as extractive industries, agribusiness, and conservation alike encroach into community and indigenous lands, and hinder local people’s ability to manage and be sustained by their territories, and to play a role in fostering biodiversity.

The “Promise” of the World Parks Congress[4] has encouragingly identified the role and rights of aboriginal peoples within community-based systems. It also pledges to “seek to redress and remedy past and continuing injustices in accord with international agreements”. Yet, state- and privately-managed conservation pursuits undertaken within former and current aboriginal ancestral territories, exercise ever greater control over large, highly biodiverse landscapes, without the needed scrutiny and appropriate responses to rights violations. The Promise’s call “to ensure that protected areas do not regress but rather progress” demands that more attention be paid to territorial jurisdiction and stewardship by indigenous peoples and local communities.

PREDATORY AND PERILOUS CONSERVATION

The idea that state conservation agencies and large international conservation NGOs have pursued their agendas at the expense of indigenous and local communities is not new. In 2003 for instance, at the fifth World Parks Congress in Durban, issues of justice and human rights were put on the table.[5] The following year, an important paper by anthropologist Mac Chapin called the conservation establishment to account for how it had dealt with indigenous communities[6]. Since then, governments endorsed and adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and work has been underway to clarify, implement and uphold rights, including in the context of conservation standards[7].

However, what lasting effect this kind of attention to human rights issues has had on the practice of state conservation is not clear. Evidence of the negative social impact of state managed conservation continues to pile up. In 2009, Dowie’s Conservation Refugees exposed how conservation organizations have become one of the biggest threats to indigenous peoples all over the world[8]. Moreover, research efforts continue to document the trampling of community rights through the accumulation of land and resources by government conservation agencies, their international NGO partners[9], and corporate tourism. Dispossession, forced resettlement and violation of the rights of local communities in places targeted for conservation have recently been documented in India, Thailand, and Central and Eastern Africa[10].

Despite the sheer volume of cases of forced evictions and destroyed livelihoods, the prominent message from last year’s World Parks Congress was clear and simple: let there be no retreat; let every country play its part in the push to achieve protected area targets; let the park rangers have more support in their war against poachers! This trend once again compels an examination of a global conservation strategy which in many countries signifies the continuation of policies of forced resettlement in order to create, extend and strengthen state managed parks and game reserves.

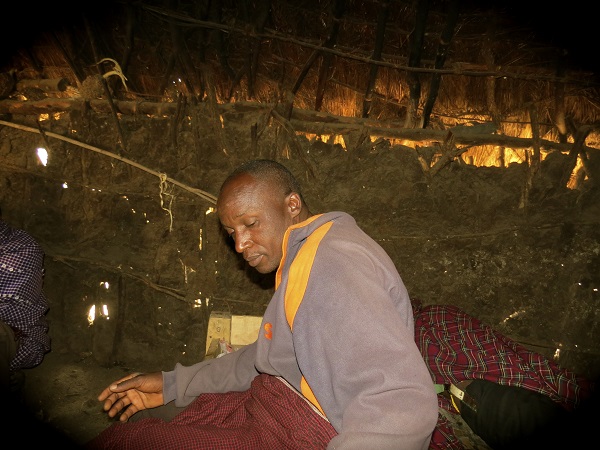

Eviction attempt, Uvinje village, north of Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania (Credit: Uvinje villagers)

To appreciate the impacts of current approaches to conservation, one only needs to take a quick look at some of the most park-friendly countries, such as Tanzania whose protected areas cover no less than one-third of the country’s territory. In Tanzania, a barrage of factors frustrate conservation efforts, including climate change, a growing human population, poverty, unsustainable resource use outside of protected areas, encroachment into park lands, and most notably an overwhelming poaching crisis. The steady expansion of the protected area network together with the need to combat the unprecedented level of organized poaching of iconic wildlife species such as elephants and rhinos have been accompanied by a relentless push for escalating security budgets[11].

Yet these challenges only partially describe the nature of the problem facing conservation in the country today. Tanzania’s pattern of forcibly displacing ancestral communities from their land and significantly hindering mobile people’s ability to seasonally access needed resources, while the tourism industry and the government conservation agencies continue to accumulate territory may be the most fundamental challenge to the conservation of biodiversity in the country[12].

On one side, disillusioned communities surrounding parks and game reserves, once stewards of their own environments, have been divested of all but tiny remnants of their ancestral lands or have been fully dispossessed, leading to destroyed livelihoods, out-migration and social conflict. Peoples integrally connected to their natural environment, such as the Maasai of Loliondo[13], and communities who in the past proactively reached out to seek a partnership with the government to implement conservation, such as Uvinje on Tanzania’s northern coast[14], have been stripped of their tenure rights and their ability to properly care for themselves and the wildlife, and portrayed as enemies of conservation. On the other side, there are the comparatively well-funded activities of an entrenched conservation machinery. Under their watch, wildlife has been imperilled by organized criminal poaching taking advantage of corruption[15] and by ill-managed trophy hunting[16].

Similar stories can be told about other countries[17], with poaching ironically reaching alarming and critical levels inside protected areas[18]. Yet overall, protected areas have come to be widely regarded as the best or even the only hope for nature’s survival.

To what extent this is a response to increased opportunities for international assistance and investment in tourism, a defensive reaction against mining and other forms of economic development that result in destruction of habitat, or a result of skepticism about the ability of human beings to live in harmony with nature, is unclear. Probably all of these factors are playing a role.

Regardless, protected areas are — under the premise the ends justify the means— being pursued at any price and by any means possible. For indigenous and rural communities who live on land targeted for conservation by the state or by conservation NGOs, even when they have been stalwart stewards of the ecosystems they inhabit, the result is devastating.

THE CULTURE OF CONSERVATION

Unfortunately, as long as we remain resigned to a culture of conservation that treats human beings as the enemy and that turns a blind eye to violations of human rights, the approach will be self-defeating. Current declines in biodiversity are not primarily a result of gaps in the number, extent and representation of parks and other kinds of protected areas, nor is the decline of iconic species caused by insufficiently strict exclusion of poor rural people from their traditional territories. What we are seeing are the consequences of a fundamentally misguided strategy being pursued by global and national conservation establishments. There are three essential problems with this strategy.

First, the pursuit of conservation through the creation of boundaries and enclosures which divide communities and nature and place nature under the strict control of powerful, unaccountable non-local institutions can only work to the extent that protected areas can be buffered from social discontent beyond their boundaries—an essentially impossible task. The marginalization and dispossession of indigenous peoples and rural communities in the name of conservation, the capturing of the tourism dollars and other economic benefits of conservation by local and national elites and by international investors, and the militarization of protected areas can only lead to increasing social conflict and disillusionment with the very idea of conservation and with the organizations promoting it. Cash payouts as a part of “benefit sharing”, even when they do actually materialize, even when they do amount to something more than crumbs, cannot compensate for losing one’s livelihood, cultural bearings, land and home.

In contrast to this trend is the growing recognition from both researchers and practitioners that biological diversity is intrinsically connected to cultural diversity, and that indigenous peoples and local communities enrich the practice of conservation. Indeed, where indigenous and local communities have been able to secure their rights to govern their territories as well as implement their values and outlook on protected areas and conservation, positive conservation outcomes have been achieved, and productive partnerships and new forms of collaboration have developed.[19] Conversely, the failure to acknowledge this has prevented national governments and the conservation establishment from benefiting from traditional ecological knowledge, from grassroots social and institutional experience in sustainably managing ecosystems, and from the home-grown, heartfelt conservation ethic which people who live on and from the land so often possess. We cannot expect to achieve conservation when the means of doing so violate the welfare of those who have fostered biodiversity.

Second, the dominant approach seems to ignore the fact that we live in an interconnected world, where local processes have global consequences and vice versa. What happens beyond parks is as critical as what happens within them, often more so. The international trade in engendered species, climate change, and the destruction of habitat by conflicts and by industrial resource extraction all affect indigenous and rural communities whose traditional territories lie within and adjacent to parks, but are not caused by them.

This problem was identified at the recent World Parks Congress:

The failure of the IUCN and the conservation sector to take seriously the surge in mining, extractive industries and other forms of development has put into question the integrity of protected and conserved areas, the maintenance of livelihoods for Indigenous peoples and local communities, and possible solutions to climate change and instability.[20]

Even when these communities are, in some places, contributing to the loss of biodiversity, as through the expansion of agriculture into ever more marginal lands and wildlife habitats, it must be recognized that these activities are intricately connected to conditions of poverty, failings of governance, and social injustice. Addressing environmental challenges in a fragmented way that does not account for these deeper drivers and that does not take into account the need to engage with a broader range of custodians of territories who could help to counter these drivers will not shield us from serious environmental consequences either within or outside of protected areas. Often, it is communities members’ practices we blame, as well as communities’ territories we turn our attention to, and in doing so, we fail to see what happens in the more industrialized and geopoliticized landscapes.

The third problem is more fundamental. It relates to the thinking underlying a culture and approach to conservation which divides people and nature. This fragmented worldview produces solutions based on fragmentation. It leads either to the belief that nature is a resource, something to be dominated and used, or to the conviction that it must be defended from human beings. Most state-led conservation approaches are based on a dualistic separation between people and the environment, in many cases leading to displacement, resettlement and to loss not only of rich biological, but also of cultural, diversity.[21]

Indigenous worldviews, on the other hand, see human beings as part of the world of nature and recognize an interconnectedness which runs deeper than simply acknowledging that our material survival depends on healthy ecosystems. In a worldview founded on interconnectedness, nature shapes who we are as human beings. And it is shaped by us—not as engineers fabricating a machine to chosen specifications, but as creatures that move within and help to make up the world of nature. Small parts called “protected areas” cannot be healthy apart from the whole.

From this perspective, the very phrase “protected area” reveals misguided thinking. Protected from what? The answer—protected from us—reveals the imbalance that calls out for correction. Indigenous worldviews suggest that it is interconnectedness that allows diversity to thrive. These views have been, more often than not, persistently disregarded in state-managed conservation and the mainstream conservation paradigm whose worldview is one of reducing the world and ways of thinking down to their component parts. Another question—protected for whom?—calls into question who it is that really benefits. As protected areas increasingly become linked to economic ventures, through payment for ecosystem services and offsets, bioprospecting and tourism, the people who benefit most are seldom those who live in or adjacent to the actual sites of conservation.

MEANINGFUL INSTITUTIONAL AND COLLECTIVE ACTION IS NEEDED

Setting conservation on a different path will require thorough changes in institutions and institutional culture, the challenging of vested interests, and new ways of thinking about human beings’ relationship with nature, all of which will be long term undertakings. Yet, there are some steps that could be taken immediately to help reframe conservation in a way that respects human rights, protects cultural diversity, and mobilizes local communities as allies in environmental conservation efforts.

REASSESSING PROTECTED AREA TARGETS AS A MEASURE OF PROGRESS

Through the Convention on Biological Diversity, the countries of the world have agreed to targets for the establishment of protected areas: at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10% of coastal and marine areas.[22]

The guidelines for achieving these targets allow for protected areas with differing management objectives, including sustainable use of resources, and allow for different forms of governance, including governance by local communities and indigenous groups. However, in their implementation the targets have provided a perfect excuse for land grabs and other unjust practices in the name of conservation. The single-minded push to create national parks and game reserves has undermined the role of people who are connected with and care about nature, and in so doing it undermines conservation.

The protected areas targets of the Convention on Biological Diversity also include a milestone that “all protected areas are effectively and equitably managed”. It is time for this milestone to be given some teeth. Unless it is aboriginal peoples specifically requesting for a park to be established on their territory, this might entail withdrawing support towards the establishment of national parks within territories inhabited by aboriginal peoples, and not counting these cases as contributing to protected area targets.

Ultimately, progress in conservation effectiveness needs to be defined also in terms of equity, shared or community-led jurisdiction and the cooperative engagement of local custodians rather than percentage of territories set aside as protected areas[23].

REORIENTING WHAT CONSERVATION BUDGETS ARE SPENT ON

Currently, much of the assistance from international conservation organizations and aid agencies for conservation in developing countries supports, either directly or indirectly, the dominant strategy based on strong, state-governed protected areas.

An alternative approach would direct more resources to initiatives such as supporting ongoing but overlooked efforts of local communities[24], and building the capacity of community-based organizations and indigenous and local governments to engage in conservation and develop sustainable economies.[25] It would also facilitate equitable partnerships for conservation, which put communities on an equal footing with government, international conservation NGOs and the tourism industry in terms of participation in decision-making, access to training and certification, and access to employment.

Conservation dollars might also be expected to achieve a greater long term impact by monitoring and addressing drivers of environmental degradation beyond protected areas, the real culprit behind loss of ecosystems and biodiversity.

Support is needed for landscape-wide approaches which include communities as full partners, which recognize and protect their assets and tenure rights inside and outside protected areas, and which aim for protection of habitats as well as sustainable and just use of natural resources beyond protected area islands.

Where powerful interests cannot be expected to partner with communities in good faith, the financing of social justice initiatives is needed: funds to support community legal action in defence of human rights, and mechanisms to ensure meaningful engagement, informed collective consent, and compliance on the part of powerful states and non-state conservation actors.

RECONNECTING PEOPLE WITH NATURE

Even in rural areas, people’s connection to their environment is changing. But this is a trend that could be reversed by taking a more socially conscious approach to conservation.

Countries that still have large areas of natural forest and savannah should not be building walls to keep people away from nature or slowly depriving areas of badly needed services and infrastructure as a way to push people away. Instead, they should support people to make decisions for the well-being of their children and grandchildren, provide requested extension services, and encourage local economies that protect biocultural diversity while also adding value to it.

The primary purpose of parks should not be to attract international tourists. Instead, more should be done to attract and assist local people to (re)connect with their territory. This is particularly true for rural people who live adjacent to protected areas. Rural people we have spoken to who live near Serengeti National Park Tanzania, for instance, miss the days when the Park regularly sent buses to take their children on trips into the park[26]. People living on the north-east side of Saadani National Park do not understand how government reclassification of their former village lands can be used to prevent them from visiting ancient sacred places.[27]

There is a need to recognize and support indigenous people’s and local communities’ ability to live well in their territories and to use their resources according to their values and knowledge. Indeed, there is growing evidence that indigenous peoples whose human rights are protected, e.g. their rights to their lands, territories and resources and right to self-determination, have ecosystems that are in much better shape than national parks and reserves managed by the State or other external actors.[28] The separation of communities from their ancestral territories undermines the interconnectedness that we so badly need and depend upon.

JUST CONSERVATION

Beyond the specific necessities of reassessing protected areas targets as a policy tool and reorienting what conservation budgets are spent on, there is a broader, longer term need to re-examine existing global and national policies and governance mechanisms for conservation. At a moment when organized poaching and international trade in endangered species is threatening the survival of too many species, in some instances fuelling armed conflicts (…even within state-governed parks and game reserves! …even though conservation spending is the highest in history!), threats within and beyond protected areas surpass the ability of any one stakeholder, approach or institution to maintain biologically and culturally diverse landscapes.

The need to re-enlist local communities as allies in conservation is urgent. This need can be met, not through “awareness-raising” programs, but through tangible steps toward recognition of rights to territory, concrete redress of social justice infringements and participation in decision-making processes, as well as effective delivery of requested services and infrastructure in areas that are often impoverished and marginalized.

Meaningful institutional inclusion, shared jurisdiction and clear recognition of diverse values and knowledge systems guiding conservation, direct training and employment and sustainable economies can lead to multi-level cooperation and concerted collective action. Meager benefit-sharing programs and draconian restrictions on inhabitation, access and use of protected areas will not suffice.

In particular, enforceable mechanisms are needed for the defence of human rights and the preventing of evictions of local communities and indigenous peoples from targeted landscapes. This must include safeguarding and in many cases reinstating communities’ land tenure rights, as well as creating systems for meaningful engagement between local communities on the one hand and government conservation agencies and conservation NGOs on the other. Just conservation is effective conservation: it is time for tangible action to make it happen.

REFERENCES

[1] Survival International, Parks Need Peoples.[2] Watson, J., Dudley, N., Segan, N. and Hockings. 2014. Theperformance and potential of protected areas. Nature, 515: 72.

[3] Coetzee, B., Gaston, K. and Chown, S. 2014. Local scale comparisons of biodiversity as a test for global protected area ecological performance: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9(8): e105824.

[4] The “Promise of Sydney” was the official communiqué of the IUCN World Parks Congress, held in Sydney in November 2014. It rests on four pillars which collectively represent the outcomes of the World Parks Congress: the core Vision; twelve Innovative Approaches;Commitments, including pledges from countries, funders and organizations; and Solutions. The four pillars “collectively represent the direction and blueprint for a decade of change that emanate from the deliberations of this World Parks Congress”.

[5] Brosius, J. P. 2004. Indigenous Peoples and Protected Areas at the World Parks Congress. Conservation Biology, 18: 609–612.

[6] Chapin, M. 2004. A challenge to conservationists. World Watch Magazine, (November/December), 17–31.

[7] United Nations, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the General Assembly on 13 September 2007; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure, endorsed by the Committee on World Food Security on 11 May 2012. Indian Law Resource Center and IUCN Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy. 2015. Conservation and Indigenous Peoples in Mesoamerica: A Guide; D. Roe, G. Oviedo, L. Pabon, M. Painter, K. Redford, L. Siegele, J. Springer, D. Thomas and K. Walker Painemilla. 2010. Conservation and human rights: the need for conservation standards. London: IIED; IIED, Conservation Initiative on Human Rights; IIED and Natural Justice, Human Rights Standards for Conservation; Campese, J., Sunderland, T., Greiber, T. and Oviedo, G. (eds.) 2009. Rights-based approaches: Exploring issues and opportunities for conservation. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR and IUCN.

[8] Mark Dowie. 2009. Conservation Refugees: The Hundred-Year Conflict between Global Conservation and Native Peoples. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[9] T.A. Benjaminsen, M. J. Goldman, M.Y. Minwary and F. P. Maganga. 2013. Wildlife management in Tanzania: State control, rent seeking and community resistance. Development and Change, 44(5): 1087–1109; T.A. Benjaminsen and I. Bryceson. 2012. Conservation, green/blue grabbing and accumulation by dispossession in Tanzania. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2): 335-355; Kumar, K.J, 2008. Reserved Parking: Marine reserves and small-scale fishing communities.SAMUDRA Dossiers. International Collective in Support of Fishworkers. Chennai, India: Nagaraj and Company Pvt Ltd

[10] Survival International, 2015. World Wildlife Day: tribespeople denounce persecution in the name of ‘conservation’; Vidal, J. How the Kalahari bushmen and other tribes people are being evicted to make way for ‘wilderness’. The Guardian, 16 November 2014; Survival International, Parks Need People; Bennet, G., J. Woodman, J. Gakelebone, S. Pani, J. Lewis. 2015. Indigenous Peoples destroyed for misguided ‘conservation’. Lecture presented at the ‘Beyond Enforcement: Communities, governance, incentives and sustainable use in combating wildlife crime’ conference, 26-28th February, Muldersdrift, South Africa; Bennett, O. and C. McDowell. 2012. Displaced: The Human Cost of Development and Resettlement. Palgrave Macmillan.

[11] (“We need a $77 million budget per year to be able to ensure all our national parks are sufficiently secured, while the current budget stands at $38 million annually,” Minister of Tourism (The East African, 28 April 2012); “[T]his includes additional millions of dollars to help countries across the region build their capacity to meet this challenge, because the entire world has a stake in making sure that we preserve Africa’s beauty for future generations,” Barack Obama (Washington Times/The Global Animal, 8 August 2013).

[12] J. Friedman-Rudovsky. The ecotourism industry is saving Tanzania’s animals and threatening its Indigenous People. Vice Magazine, 12 May 2015.

[13] D. Smith. Tanzania accused of backtracking over sale of Masai’s ancestral land. The Guardian, 16 November 2014; N. Malilk. Rich Gulf Arabs using Tanzania as a playground? Someone opened the gate. The Guardian, 17 November 2014.

[14] Orozco, A., 2014. Uvinje Village and Saadani National Park, Research For Change; Minority Rights Group International, MRG warns community land rights are under threat in Uvinje, Tanzania, 18 February 2015; ICCA Consortium, Consortium appeal to the Tanzania authorities: NO eviction of Uvinje villagers, respect communities sensitive to conservation!

[15]K. Heath. New report shows corruption and abuse rife within Tanzania wildlife sector. Wildlife News, 10 March 2015.

[16] There is no question that trophy hunting is very lucrative; whether and under which conditions it is being carried out in a sustainable way and in partnership with local communities is another question, brought to center stage by the killing of Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe: see Cooney, R. What will Cecil the Lion’s legacy be? And who will decide? The Huffington Post, 2 August 2015. Packer, C., H. Brink, B.M. Kissui, H. Maliti, H. Kushnir and T. Karo. 2010. Effects of trophy hunting on lion and leopard populations in Tanzania. Conservation Biology, 21(1): 142-153

[17] G. Bennet, J. Woodman, J. Gakelebone, S. Pani, J. Lewis. 2015.Negative impacts of wildlife law enforcement in Botswana, Cameroon and India – How tribal peoples are evicted, arrested and imprisoned in the name of conservation. Survival International; Roe, D., S. Milledge, R. Cooney, M. ’t Sas-Rolfes, D. Biggs, M. Murphree and A. Kasterine. 2014. The elephant in the room: Sustainable use in the illegal wildlife trade debate. London: IIED; Duffy R., F.A.V. St John, B. Büscher, and D. Brockington. 2015. The militarization of anti-poaching: Undermining long-term goals? Environmental Conservation (in press). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0376892915000119; D.W.S. Challender and D.C. MacMillan. 2014. Poaching is more than an enforcement problem.Conservation Letters, 7(5): 484-494.

[18] Duffy, R. 2014. Waging a war to save biodiversity: the rise of militarized conservation. International Affairs, 90: 819–834. Rhino poaching in South Africa at record levels following 18% rise in killings(The Guardian, 11 May 2015), with most taken in the Kruger National Park.

[19] Porter-Bolland, L., E.A. Ellis, M. R. Guariguata, I. Ruiz-Mallén, S. Negrete-Yankelevich, V. Reyes-García. 2015. Community managed forests and forest protected areas: An assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. Forest Ecology and Management, 268: 6-17; Ross, H., C. Grant, C. Robinson, A. Izurieta, D. Smyth and P. Rist. 2009. Co-management and Indigenous Protected Areas in Australia: achievements and ways forward. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 16(4): 242-252; Andrade, G. S. M., and J. R. Rhodes. 2012. Protected areas and local communities: an inevitable partnership toward successful conservation strategies? Ecology and Society 17(4): 14; Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs).

[20] World Parks Congress, A strategy of innovative approaches and recommendations to enhance implementation of a New Social Compactin the next decade. The vision of the new social compact that came out of the World Parks Congress is to inspire a movement towards effective and just conservation that increases the relevance and strength of protected and conserved areas by galvanizing diverse stakeholders to collectively commit to a new conservation ethic.

[21] See current stories of bans, evictions and resettlements in the sitesJust Conservation and Survival International.

[22] Aichi Biodiversity Targets

[23] “A common theme at the World Parks Congress was a recognition that the quality components of Aichi Target 11 are more important than the percentage targets” (A strategy of innovative approaches and recommendations to reach conservation goals in the next decade).

[24] Sheil, D., M. Boissière, and G. Beaudoin. 2015. Unseen sentinels: local monitoring and control in conservation’s blind spots. Ecology and Society 20(2): 39.

[25] Example of engaging communities in the wildlife trade: Roe, D (ed). 2015. Conservation, crime and communities: case studies of efforts to engage local communities in tackling illegal wildlife trade. London: IIED.

[26] Robinson, L.W., N. Bennett, L.A. King, G. Murray. 2012. “We Want Our Children to Grow Up to See These Animals”: Values and Protected Areas Governance in Canada, Ghana and Tanzania. Human Ecology,40:571-581.

[27] Orozco, A. 2014. Uvinje village and Saadani National Park, Research for Change.

[28] Tauli-Corpuz, V. Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Statement to the 14th session of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 27 April 2015, New York; Springer, J., and F. Almeida. 2015. Protected areas and the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities: Current issues and future agendas. Washington: Rights and Resources Initiative.