Violence and Its Aftermath

A different version of this interview appeared in A Language Older Than Words

Derrick Jensen: What is the relationship between atrocity and silence?

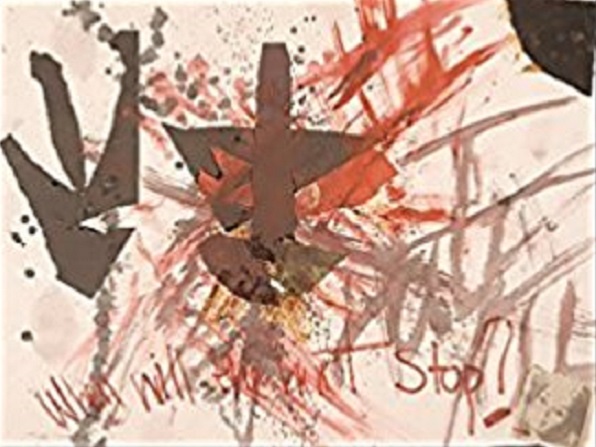

Judith Herman: Atrocities are actions so horrifying they go beyond words. For people who witness or experience atrocities, there is a kind of silencing that comes from not knowing how to put these experiences into words. At the same time, atrocities are the crimes perpetrators most want to hide. This creates a powerful convergence of interest: No one wants to speak about them. No one wants to remember them. Everyone wants to pretend they didn’t happen.

DJ: In Trauma and Recovery, you write, “In order to escape accountability the perpetrator does everything in his power to promote forgetting.”

JH: This is something with which we are all familiar. It seems that the more extreme the crimes, the more dogged and determined the efforts to deny that the crimes happened. So we have, for example, almost a hundred years after the fact, an active and apparently state-sponsored effort on the part of the Turkish government to deny there was ever an Armenian genocide. We still have a whole industry of Holocaust denial. I just came back from Bosnia where, because there hasn’t been an effective medium for truth-telling and for establishing a record of what happened, you have the nationalist governmental entities continuing to insist that ethnic cleansing didn’t happen, that the various war crimes and atrocities committed in that war simply didn’t occur.

DJ: How does this happen?

JH: On the most blatant level, it’s a matter of denying the crimes took place. Whether it’s genocide, military aggression, rape, wife beating, or child abuse, the same dynamic plays itself out, beginning with an indignant, almost rageful denial, and the suggestion that the person bringing forward the information–whether it’s the victim or another informant–is lying, crazy, malicious, or has been put up to this by someone else. Then of course there are a number of fallback positions to which perpetrators can retreat if the evidence is so overwhelming and irrefutable it cannot be ignored, or rather, suppressed. This, too, is something we’re familiar with: the whole raft of predictable rationalizations used to excuse everything from rape to genocide: the victim exaggerates; the victim enjoyed it; the victim provoked or otherwise brought it on herself; the victim wasn’t really harmed; and even if some slight damage has been done, it’s now time to forget the past and get on with our lives: in the interests of preserving peace–or in the case of domestic violence, preserving family harmony–we need to draw a veil over these matters. The incidents should never be discussed, and preferably they should be forgotten altogether.

DJ: Something I wonder, as I watch corporate spokespeople utter absurdities to defend, for example, the polluting of rivers or the poisoning of children, is whether these people believe their own claims. I’ll give an example: I live less than three miles from the Spokane River, in Washington state, which begins about forty miles east of here as it flows out of Lake Coeur d’Alene. Lake Coeur d’Alene, one of the most beautiful lakes in the world, is also one of the most polluted with heavy metals. There are days when more than a million pounds of lead drains into the lake from mine tailings on the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River. Hundreds of migrating tundra swans die here each year from lead poisoning as they feed in contaminated wetlands. Some of the highest blood lead levels ever recorded in human beings were from children in this area. Yet just last summer the Spokesman-Review, the paper of record for the region, wrote that concern over this pollution is unnecessary because “there are no dead [human] bodies washing up on the river banks.” To return to the original question, to what degree do both perpetrators and their apologists believe their own claims? Did my father, to provide another example, really believe his claims that he wasn’t beating us?

JH: Do perpetrators believe their own lies? I have no idea, and I don’t have much trust in those who claim they do. Certainly we in the mental health profession don’t have a clue when it comes to what goes on in the hearts and minds of perpetrators of either political atrocities or sexual and domestic crimes.

For one thing, we don’t get to know them very well. They aren’t interested in being studied–by and large they don’t volunteer–so we study them when they’re caught. But when they’re caught, they tell us whatever they think we want to hear.

This leads to a couple of problems. The first is that we have to wend our way through lies and obfuscation to attempt to discover what’s really going on. The second problem is even larger and more difficult. Most of the psychological literature on perpetrators is based on studies of convicted or reported offenders, which represents a very small and skewed, unrepresentative group. If you’re talking about rape, for example, since the reporting rates are, by even the most generous estimates, under twenty percent, you lose eighty percent of the perpetrators off the top. Your sample is reduced further by the rates at which arrests are made, charges are filed, convictions are obtained, and so forth, which means convicted offenders represent about one percent of all perpetrators. Now, if your odds of being caught and convicted of rape are basically one in one hundred, you have to be extremely inept to become a convicted rapist. Thus, the folks we are normally able to study look fairly pathetic, and often have a fair amount of psychopathology and violence in their own histories. But they’re not representative of your ordinary, garden-variety rapist or torturer, or the person who gets recruited to go on an ethnic cleansing spree. We don’t know much about these people. And the one thing victims say most often is that these people look normal, and that nobody would have believed it about them. That was true even of Nazi war criminals. From a psychiatric point of view, these people didn’t look particularly disturbed. In some ways that’s the scariest thing of all.

DJ: Given the misogyny, genocide, and ecocide endemic in our culture, I wonder how much of that normality is only seeming.

JH: If you’re part of a predatory and militaristic culture, then to behave in a predatory and exploitative way is not deviant, per se. Of course there are rules as to who, if you want to use these terms, might be a legitimate victim, a person who may be attacked with impunity. And most perpetrators are exquisitely sensitive to these rules.

DJ: To your understanding, what are the levels of rape and childhood sexual abuse in this country?

JH: The best data we have is that one of four women will be raped over a lifetime. For childhood sexual abuse I like to quote Diana Russell’s data, which I believe is still the standard by which these studies are measured. She asked a random sample of 900 and some women to participate in a survey of crime victimization. The interviews were in-depth, and conducted in the subjects’ native languages by trained interviewers. She found that 38 percent of females had a childhood experience that met the criminal code definition of sexual assault. Some people have said that because Russell’s study was done in California, it’s not representative, but the results from other studies have been, while slightly lower, still in the same ballpark. It’s a common experience. It’s less common for boys, but there is still a substantial risk for them as well.

DJ: I remember reading something like 7 to 10 percent.

JH: I’d say a fair estimate would be around ten percent for boys, and two to three times that for girls. It is a little more difficult to determine levels of sexual abuse for boys, because most are victimized by male perpetrators, which adds a layer of secrecy and shame to the child’s experience.

DJ: This is a huge percentage of the population which has been severely traumatized. Why isn’t this front page news every day?

JH: Actually there is a point to be made here as well. One of the questions Diana asked her informants who disclosed childhood abuse was: What impact do you think this has had on your life? Only about one in four said it had done great or long-lasting damage. Virtually everyone said, “It was horrible at the time, and I hated it.” But half of the women considered themselves to have recovered reasonably well, and didn’t see that it had affected their lives in a major way. I say this not to minimize the importance of what happened, but to give due respect and recognition to the resilience and resourcefulness of victims, most of whom recover without any formal intervention.

Part of the reason for this is that not all traumas are equal. Diana and I took a look at the factors that seemed to lead to long-lasting impact, and they were the kinds of things you would expect. Women who reported prolonged, repeated abuse by someone close–father, stepfather, or another member of the immediate family–abuse that was very violent, that involved a lot of bodily invasion, or that involved elements of betrayal were the ones who had the most difficulty recovering.

But you were asking why this isn’t front page news. The answer is partly that this isn’t new. And it’s also not something unique to this country. Wherever studies of comparable sophistication are carried out, the numbers are pretty much the same. We may have a lot more street and handgun violence than, for example, Northern Europe and Scandinavia, but private crimes are an international phenonemon.

DJ: But they aren’t ubiquitous to all human cultures. I’ve read in multiple sources that prior to contact with our culture there have been some indigenous cultures in which rape and child abuse were rare or nonexistent. I know that the Okanagan Indians of what is now British Columbia, for example, had no word in their language for either rape or child abuse. They did have a word that meant the violation of a woman. Literally translated it meant someone looked at me in a way I don’t like.

JH: I think it would be hard to establish that rape was nonexistent in a culture. How would you determine that? But you can certainly say there is great variation. The anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday looked at data from over one hundred cultures as to the prevalence of rape, and divided them into high- or low-rape cultures. She found that high rape cultures are highly militarized and sex segregated. There is a lot of difference in status between men and women. The care of children is devalued and delegated to subordinate females. She also found that the creation myths of high rape cultures recognize only a male deity rather than a female deity or a couple. When you think about it, that is rather bizarre. It would be an understandable mistake to think women make babies all by themselves, but it’s preposterous to think men do that alone. So you’ve got to have a fairly elaborate and counterintuitive mythmaking machine in order to fabricate a creation myth that recognizes only a male deity. There was another interesting finding, which is that high rape cultures had recent experiences–meaning in the last few hundred years–of famine or migration. That is to say, they had not reached a stable adaptation to their ecological niche.

Sadly enough, when you tally these risk factors, you realize you’ve pretty much described our culture.

DJ: I’d like to back up for a moment to define some terms. Can you tell me more about the phenomenon of psychological trauma?

JH: Trauma occurs when people are subjected to experiences that involve extreme terror, a life threat, or exposure to grotesque violence. The essential ingredient seems to be the condition of helplessness.

In the aftermath of such experiences it is normal and predictable that traumatized people will experience particular symptoms of psychological distress. Most people experience these transiently, and recover more or less spontaneously. Others go on to have prolonged symptoms we’ve come to call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

It’s important to note, by the way, that PTSD doesn’t merely affect “helpless” women and children. We see it in combat veterans. We see it in prisoners of war. Concentration camp survivors. We see it with survivors of natural disasters, fires, and industrial and automobile accidents. We see it in cops. Sophisticated police departments now include traumatic stress debriefing for their officers involved in any sort of critical incident such as a shooting. They had discovered that within two years of involvement in a critical incident, enormous numbers of well-trained, valuable, experienced police officers were being lost to disabilities, physical complaints, substance abuse, or psychiatric problems. We see it in firefighters who have to rescue people from burning buildings, and who sometimes have to bring out dead bodies. We see it in rescue workers who have to clear away bodies after a flood or earthquake. We see it most commonly in the civilian casualties, if you will, of our private war against women and children, that is, the survivors of rape and domestic violence.

DJ: What are the symptoms?

JH: It’s easiest to think about symptoms in three categories. The first are called symptoms of hyperarousal. In the aftermath of a terrifying experience people see danger everywhere. They’re jumpy, they startle easily, and they have a hard time sleeping. They’re irritable, and more prone to anger. This seems to be a biological phenomenon, not just a psychological one.

The second thing that happens is that people relive the experience in nightmares and flashbacks. Any little reminder can set them off. For example, a Vietnam veteran involved in helicopter combat might react years later when a news or weather helicopter flies overhead.

DJ: All through my teens and twenties when someone would ask me to go water skiing, my response externally would be to say, “No, thanks,” but my internal response was, “Fuck you.” I never could figure out why until a few years ago I asked my mom, and she said that there were beatings associated with water skiing trips when I was a small child. I never knew that. I just always knew that water skiing pissed me off.

JH: Sometimes people understand the trigger, but sometimes they won’t have complete memory of the event. They may respond to the reminder as you did, by becoming terrified or agitated or angry.

DJ: And it doesn’t have to be so dramatic as the stereotypical Vietnam vet who goes berserk when he hears a car backfire.

JH: A lot of times it’s more subtle. Someone who was raped in the backseat of a car may have a lot of feelings everytime she gets into a car, particularly one that resembles the one in which she was raped.

This reliving, these intrusions, are not a normal kind of remembering, where the smell of cinammon rolls, for example, may remind you of your grandmother. Instead, people say it’s like playing the same videotape over and over. It’s a repetitive and often wordless reexperiencing. People remember the smells, the sounds, or if it was raining, if it was cold. The images. It was dark. Sexual abuse survivors often say, “I felt like I was smothering. I thought I was going to choke.” But it’s very hard for people to remember it in a kind of fluid verbal narrative that is modifiable according to the circumstances. People can’t give you the short form and the long form, and describe it differently and understand it differently over time. It’s just a repetitive sequence of terrifying images and sensations.

DJ: Is that symptom also physiological?

JH: Oh, yes. Studies have shown that traumatic memories are perceived and encoded in the brain differently from regular memories.

The third group of symptoms that people have–and these are almost the opposite of the intrusive nightmares and flashbacks, the dramatic symptoms–is a shutting down of feelings, a constriction of emotions, intellect, and behavior. It’s characteristic of people with PTSD to oscillate between feeling overwhelmed, enraged, terrified, desperate, or in extreme grief and pain, and feeling nothing at all. People describe themselves as numb. They don’t feel anything, they aren’t interested in things that used to interest them, they avoid situations that might remind them of the trauma. You, for example, probably avoided water skiing in order to avoid the traumatic memories. Water skiing may not be much to give up, but people sometimes avoid relationships, they avoid sexuality, they make their lives smaller, in an attempt to stay away from the overwhelming feelings.

In addition, one finds all kinds of physical complaints. In fact, the more the culture shames people for admitting psychological weakness, the more these symptoms manifest themselves physically. Rather than seeking psychological help, people go to the doctor seeking sleeping pills, or go to the neighborhood bar to get the number one psychoactive drug available without prescription, which is alcohol. We see a lot of alcohol and substance abuse as a secondary complication of PTSD.

DJ: Where does dissociation fit into all this?

JH: It’s central. Dissociation itself is really quite fascinating, and I don’t think any of us can quite pretend to understand it. We all seem to have the capacity to dissociate, though for some people the capacity is greater. And certain circumstances seem to call it up: it involves a mental escape from experience at a time when physical escape is impossible.

When I teach, I quite often use automobile accidents to exemplify this. I’ll ask people, “Can you describe what it was like in the moment before impact, the moment of impact, and the moment after?”

People often describe a sense of derealization: this isn’t happening. They also describe depersonalization: this is happening, but to someone else, while I sit outside watching the crash and feeling very sorry for the person in the car. They may feel as though they’re watching a movie. They describe a slowing of time. They describe a sense of tunnel vision, where they focus only on a few details such as sounds or smells or imagery, but where context and peripheral detail fall away. Some people describe alterations of pain perception; we’ve all heard stories of people who walk on broken legs until they get to safety, and then collapse, or people who are able to ignore their own pain while they rescue others. And then, of course, some people have amnesia. Memory gaps in the aftermath. They’ll say, “I remember the moment before, and then the next thing I know I was on the shoulder outside the car.” Even with no head trauma and no loss of consciousness, there will often be a loss of memory. All of these, of course, are not specific to car wrecks, but happen with all sorts of psychological trauma.

DJ: Dissociation sounds like a very good thing.

JH: You’d think so. But more and more of the research is zeroing in on dissociation as a predictor of more longlasting symptoms. For example, some studies were done after the San Francisco earthquake, and the Oakland fire, two big disasters that happened in the last decade. Each is a single event that affected lots of people, and invoked large-scale responses by emergency personnel. So researchers had a couple of chances to interview and examine many survivors, and then to call them up three, six, and more months later to see how they were doing. Well, the folks who dissociated during the earthquake turned out to be more likely to have PTSD later. There seems to be something about that altered state of consciousness that is protective at the moment, but gets you into trouble later on. By the way, people who dissociated at the time of the fire also tended to lose some of their adaptive coping in the moment. They either behaved helplessly, almost like zombies or as if they were paralyzed, or they lost the capacity to judge danger realistically. The rescue people had the most trouble with this latter group, because they would insist on going back into burning houses to rescue possessions or animals. They exposed themselves to danger, seemingly heedless of the consequences.

DJ: What’s the difference between trauma and captivity?

JH: Trauma can emerge from a single event like a fire, earthquake, or auto accident, where you’re in the situation, you survive it, and then you get on with your life. You may continue to relive it in fantasy, but it’s not happening over and over. Even if you live in an earthquake or flood zone you still have a choice as to whether to rebuild or move away.

Based on my work with domestic abuse survivors, as well as victims of political terror, I began to ask: What happens when a person is exposed not to a single terrifying incident, but rather to prolonged, repeated trauma? I came to understand the similarities between concentration or slave labor camps or torture situations on the one hand, and on the other hand, the situation of domestic or sexual violence, where the perpetrator may beat or sexually abuse his wife or children for years on end. We see this also in the sex trade, where there’s a criminally organized traffic in women and kids, and we sometimes see this sort of captivity in some religious cults, where people are not free to leave.

In situations where the trauma happens over and over, and where it is imposed by human design (as opposed to the effects of weather, or some other nonhuman force), one sees a series of personality changes in addition to simple PTSD. People begin to lose their identity, their self-respect. They begin to lose their autonomy and independence.

Because people in captivity are most often isolated from other relationships–that this is so in normal captivity is obvious and intentional, but it is overwhelmingly the case in domestic violence as well, as perpetrators often demand their victims increasingly cut all other social ties–they are forced to depend for basic survival on the very person who is abusing them. This creates a complicated bond between the two, and it skews the victim’s perception of the nature of human relationships. The situation is even worse for children raised in these circumstances, because their personality is formed in the context of an exploitative relationship, in which the overarching principles are those of coercion and control, of dominance and subordination.

Whether we are talking about adults or children, it often happens that a kind of sadistic corruption enters into the captive’s emotional relational life. People lose their sense of faith in themselves, in other people. They come to believe or view all relationships as coercive, and come to feel that the strong rule, the strong do as they please, that the world is divided into victims, perpetrators, bystanders, and rescuers. They believe that all human relations are contaminated and corrupted, that sadism is the principle that rules all relationships.

DJ: Might makes right. “Social Darwinism.” The selfish gene theory. You’ve just described the principles that undergird our political and economic systems.

JH: And there are other losses involved. A loss of basic trust. A loss of feeling of mutuality of relatedness. In its stead is emplaced a contempt for self and others. If you’ve been punished for showing autonomy, initiative, or independence, after a while you’re not going to show them. In the aftermath of this kind of brutalization, victims have a great deal of difficulty taking responsibility for their lives. Often, people who try to help get frustrated because we don’t understand why the victims seem so passive, seem so unable to extricate themselves or to advocate on their own behalf. They seem to behave as though they’re still under the perpetrator’s control, even though we think they’re now free. But in some ways the perpetrator has been internalized.

Captivity also creates disturbances in intimacy, because if you view the world as a place where everyone is either a victim, a perpetrator, an indifferent or helpless bystander, or a rescuer, there’s no room for relationships of mutuality, for cooperation, for responsible choices. There’s no room to follow agreements through to everyone’s mutual satisfaction. The whole range of cooperative relational skills, and all the emotional fulfillment that goes with them, is lost. And that’s a great deal to lose.

DJ: It seems to me that part of the reason for this loss is not simply the physical trauma itself, but also the fact that the traumatizing actions can’t be acknowledged.

JH: And much more broadly, because they take place within a relationship motivated by a need to dominate, and in which coercive control is the central feature.

When I teach about this, I describe the methods of coercive control perpetrators use. It turns out that violence is only one of the methods, and it’s not even one of the most frequent. It doesn’t have to be used all that often; it just has to be convincing. In the battered women’s movement, there’s a saying: “One good beating lasts a year.”

DJ: What constitutes a good beating?

JH: If it’s extreme enough, when the victim looks into the eyes of the perpetrator she realizes, “Oh, my God, he really could kill me.”

What goes along with this violence are other methods of coercive control that have as their aim the victim’s isolation, and the breakdown of the victim’s resistance and spirit.

DJ: Such as?

JH: You have capricious enforcement of lots of petty rules, and you have concomitant rewards. Prisoners and hostages talk about this all the time: if you’re good, maybe they’ll let you take a shower, or give you something extra to eat. You have the monopolization of perception that follows from the closing off of any outside relationships or sources of information. Finally, and I think this is the thing that really breaks people’s spirits, perpetrators often force victims to engage in activities that the victims find morally reprehensible or disgusting. Once you’ve forced a person to violate his or her moral codes, to break faith with him- or herself–the fact that it’s done under duress does not remove the shame or guilt of the experience–you may never again even need to use threats. At that point the victim’s self-hatred, self-loathing, and shame will be so great that you don’t have to beat her up, because she’s going to do it herself.

DJ: That reminds me of something I read about those who collaborated with the Nazis: “A man who had knowingly compromised himself did not revolt against his masters, no matter what idea had driven him to collaboration: too many mutual skeletons in the closet. . . . There were so many proofs of the absolute obedience that could be expected of men of honor who had drifted into collaboration.”

JH: Perpetrators know this. These methods are known, they’re taught. Pimps teach them to one another. Torturers in the various clandestine police forces involved in state-sponsored torture teach them to each other. They’re taught at taxpayer expense at our School of the Americas. The Nazi war criminals who went to Latin America passed on this knowledge. It is apparently a point of pride among many Latin American torturers that they have come up with techniques the Nazis didn’t know about.

DJ: We’ve spent a lot of time delving into the abyss, and I think what I would like to do now is emerge on the other side. But first, there’s something else about victims I would like to explore. You’ve written that symptoms of PTSD can be interpreted as attempts to tell their story.

JH: People not only relive the experiences in memory, but sometimes behave in ways that reenact the trauma. So a combat vet with PTSD might sign up for especially risky duty, or reenlist in the special forces. Later he may get a job in another high risk line of work. A sexual survivor may engage in behaviors likely to result in another victimization. Especially regarding revictimization after child abuse, the data are really very sobering. One way to view all this is that the person is trying desperately to tell the story, in action if necessary. That’s a bit teleological, but we do know that when people are finally able to put their experiences into words in a relational context, where they can be heard and understood, they often get quite a bit of relief.

DJ: You wrote in Trauma and Recovery that “When the truth is finally recognized, survivors can begin their recovery.” How does that work? What happens inside survivors when the truth is recognized?

JH: I wish I knew. It’s miraculous. I don’t understand it. I just observe it, and try to facilitate it. I think it’s a natural healing process that has to do with the restoration of human connection and agency. If you think of trauma as the moment when those two things are destroyed, then there is something about telling the trauma story in a place where it can be heard and acknowledged that seems to restore both agency and connection. The possibility of mutuality returns. People feel better.

The most important principles for recovery are restoring power and choice or control to the person who has been victimized, and facilitating the person’s reconnection with her or his natural social suports, the people who are important in that person’s life. In the immediate aftermath, of course, the first step is always to reestablish some sense of safety in the survivor’s life. That means getting out of physical danger, and that means also creating some sort of minimally safe social environment in which the person has people to count on, to rely on, to connect to. Nobody can recover in isolation.

It’s only after safety is established that it becomes appropriate for this person to have a chance to tell the trauma story in more depth. There we run into two kinds of mistakes. One is the idea that it’s not necessary to tell the story, and that the person would be much better off not talking about it.

DJ: It’s over. Just get on with your life.

JH: That may work for a while, and it might be the right choice in any given circumstance, but there comes a time eventually where if the story isn’t told it festers. So one mistake is suppressing it, which comes back to the silencing we spoke of earlier. These are horrible things and nobody really wants to hear or think about them. The victim doesn’t, the bystander doesn’t, the perpetrator certainly doesn’t. So there’s a very natural tendency on everyone’s part to say, “Let’s forget the whole thing.”

The other mistake is to try to push people into talking about it prematurely, or when the circumstances aren’t right, or when it isn’t the person’s choice. It’s almost as though we respond with either numbing or intrusion; we either want to withdraw and avoid hearing the story, or we want the victim to tell all in grotesque detail. Sometimes there’s a kind of a voyeuristic fascination that gets engaged. If the timing, pacing, and setting isn’t right, all you’re going to have is another reenactment. You’re not going to have the integrative experience of putting the story into a context that makes meaning out of it and gives a sense of resolution, which is what you’re really aiming for. You don’t want just a simple recitation of facts, you want the person to be able to talk about how it felt, how she feels about it now, what it meant to her then, what it means to her now, how she made sense of it then, how she’s trying to make sense of it now. It’s in that kind of processing that people reestablish their sense of continuity with their own lives and connection with others.

DJ: This seems to be tied to mourning what was lost.

JH: Part of the motivation for the idea of “Let’s not talk about it” is the belief that you can go back to the way you were before the trauma, and what people find is that’s just not possible. Once you’ve seen, up close, the evil human beings are capable of, you’re not going to see the world the same way, you’re not going to see other people the same way, and you’re not going to see yourself the same way. We can all fantasize about how brave or cowardly we would be in extreme situations, but people who’ve been exposed know what they did, and what they didn’t do. And almost inevitably they failed to live up to some kind of expectation of themselves. There has to be a sense of grieving what was lost. It’s only after that mourning process that people can come through it and say, “That was a hard lesson, and I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy, but I am stronger or wiser.” There is a way that people learn from adversity. People will say, “I had a crisis of faith and I found out what’s important, what I really believe in.”

DJ: How especially does an abused child mourn what he’s never known?

JH: It’s what you’ve never had that is the hardest to grieve. It’s unfair. You only get one childhood, and you were cheated out of the one that every child is entitled to.

DJ: What comes next?

JH: The recovery doesn’t end with the telling and hearing of the story. There is another step after that, which has to do with people reforming their connections, moving from a preoccupation with the past to feeling more hopeful for the future, feeling that they have a future, that it’s not just a matter of enduring and going through life as a member of the walking dead. Instead there is an ability to knowingly affirm life even after surviving the worst other people have to dish out. And I do think that what renews people is the hope and belief that their own capacity to love has not been destroyed. When people feel damned and doomed, and feel they can’t go on living, the fear often has to do with the feeling that they have been so contaminated with the perpetrator’s hate, and taken so much of it into themselves, that there is nothing left but rage, and hate, and distrust, and fear and contempt.

When people go through mourning, and through their crisis of faith, what they come back to as bedrock is their own capacity to love. Sometimes that connection is frail and tenuous, but whether it is with animals, nature, music, or other humans, that’s the bedrock to which they must return, to that one caring relationship the perpetrator was never able to destroy. And then they build from there.

I think as people move into their lives again, the ones who do best are the ones who’ve developed what Robert Jay Lifton calls a survivor mission. I’ve seen it happen so many times, that people turn this experience around, and make it a gift to others. That really is the only way you can transcend an atrocity. You can’t bury it. You can’t make it go away. You can’t dissociate it. It comes back. But you can transcend it, first by telling the truth about it, and then by using it in the service of humanity, saying, “This isn’t the way we want to live. We want to live differently.”

In the aftermath of terror many survivors find themselves much clearer and more daring about going after what they want in life, and in relationships. They straighten things out with their families and lovers and friends, and they often say, “This is the kind of closeness I want, and this is the kind of stuff I don’t want.” When people are sensitized to the dynamics of exploitation, they are able to say, “I don’t want this in my life.” And they often become very courageous about speaking truth to power.

I have heard so many survivors say, “I know what terror is. I will live in fear every day for the rest of my life. But I also know that I will be all right, and that I feel all right.” And I have heard them join others in saying, “This is the thing we want to protect, and this is the thing we want to stop. We don’t know how we’re going to do it, but we do know that this is what we want. And we’re not indifferent.” Sometimes through atrocity people discover in themselves courage that they didn’t know they had.

Originally published in the May 1998 issue of The Sun (under the pseudonym Richard Marten)

I would be interested in knowing the source of Jensen’s statement that “There are days when more than a million pounds of lead drains into the lake from mine tailings on the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River.” Thanks.

You can google “million pounds lead Coeur d’Alene River”

Thanks for finally writing about > Out of the Ashes: An interview with Judith Herman < Loved it!