by DGR News Service | Nov 17, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Obstruction & Occupation

Bobby Arbess aka Reuben Garbanzo / Friends of Carmanah/Walbran

Sixty years of logging have left only five percent of the primary low-elevation ancient temperate rainforests of Vancouver island remaining. These are some of the world’s most biologically productive forests, attaining higher levels of plant biomass than any ecosystem on earth. The logging industry liquidated the vast majority of these diverse native old-growth forest ecosystems, replacing them with even-aged monoculture tree plantations.

In 1991, 78 days of civil disobedience successfully halted 16 kilometres of scheduled road development through the last, expansive roadless ancient forest wilderness of the Walbran Valley on south Vancouver island. The Road Stops Here campaign combined prolonged tree-sits, road blockades, office occupations, street theatre, dramatic banner hangings, international support and massive public pressure to protect the land a few kilometres upstream from Canada’s iconic Pacific Rim National Park/West Coast Trail. This area is now known as ‘ground zero’ in British Columbia’s ancient forest movement, and a new battle is heating up.

The 16,000 hectare Carmanah/Walbran Provincial Park established in 1994 was a bittersweet victory for environmental activists who fought to save the valley’s ecologically outstanding ancient forests. The park boundaries were drawn up at a roundtable of stakeholders dominated by transnational forest companies owning timber licenses in the valley. The largest and oldest western redcedar trees in the world live at the confluence of three main branches of the watershed, at the heart of the wilderness now known as the Central Walbran Ancient Forest. The 485 hectares north of Walbran river, though designated a “special management zone”, was excluded from full park protection.

Twenty-five years of intense public scrutiny and regulatory provisions have limited “harvesting” to one cutblock in the Central Walbran Ancient Forest. The area is once again the focus of a direct action struggle to keep industrial destruction such as chainsaws, heli-logging and road building out of this wild rainforest of giant trees adjoining the park.

Ongoing road building on steep slopes of the unprotected land-base opens more and more old-growth remnants to clearcut logging. In reaction, there is a growing resurgence of public support, particularly in rural communities, for preserving the unfragmented wilderness of the Ancient Forest. Before a twelve-year government policy of shutting down local unionized mills in favour of raw log exports, the rural communities were based on thriving forestry towns. Now they watch the last massive trees pass their windows on the backs of the same log trucks which exported their livelihoods.

In June 2015, logging company Teal Jones submitted a plan for eight cutblocks in the area. With approval given for a heli-logging operation to high-grade cut a grove of 500-1200 year old trees, logging is now imminent in this pocket wilderness within the traditional Pacheedaht First Nations territory.

There is a slow-growing yet persistent expression of opposition to the logging within the indigenous community, to the chagrin of band council leaders. These leaders maintain a close relationship with the logging company and manage their own logging operations elsewhere in their territory, with plans to build and run a sawmill to generate jobs and revenues.

Many economic alternatives to continued old-growth logging are being proposed to address the high unemployment and poverty in the community:

- ethnocultural forest tourism

- harvesting of non-timber and other traditional forest products such as mushrooms, berries, and basketry materials

- ecologically-managed second growth plantations

- value-added production of finished wood products

- maximizing employment per cubic metre of wood and minimizing impacts on the land, waterways and biological diversity who depend on healthy and old-growth forests for their continued survival

The remaining old-growth forests of the Walbran valley harbor the highest concentrations of the Marbled Murrelet, an endangered seabird, anywhere outside of Alaska. The forests also shelter other old-growth dependent birds including the Western Screech owl, Western Pygmy owl, and Northern Goshawk, all listed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) as vulnerable or threatened. Fifteen years of old-growth forest canopy research has revealed hundreds of species found nowhere else in the world, inhabiting suspended soil habitats of the forest canopy. These unique microhabitats are found as much as two hundred feet off the forest floor, and are not supported by second-growth forests.

Climate activists are now pointing out the critical ecological role these old forests play for the whole world in sequestering atmospheric carbon and buffering against runaway climate change.

The provincial government has ignored several requests to protect the area, including a petition card campaign of 6000 signatures presented in the legislature in September.

Activists built a witness camp in mid-September to host a continuous presence of observers watching for the start of logging in approved cutblock 4424. Others recently established a “checkpoint” action camp on a main road into the area. In autonomous actions of non-violent civil disobedience, they have erected sporadic road barricades denying access to logging and road-building crews. Company officials have requested that activists move their camp to allow for preparation of a large landing for loading logs onto trucks. So far the activists have not responded to this request and a confrontation in this area may be imminent.

The activists are calling for people to converge on Vancouver Island to observe, support, or participate in actions; make supporting donations through their website; contact BC residents and politicians; and spread the news of the threats and the resistance. They encourage members of the international community to join the Friends of Carmanah/Walbran Facebook group to stay in the loop of daily developments and to access action updates, relevant links and articles, road instructions, and carpool information.

The Friends of Carmanah/Walbran is a loose-knit community of people around the world sharing the passion, resources and collective action to protect this ancient forest, once and for all.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 16, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

By Stephany Seay / Buffalo Field Campaign

Winter is setting in. Snow is accumulating, and with the snow comes migration. The deep snows of Yellowstone’s high plateau drive elk, buffalo, deer, moose, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep down to lower elevations. Unfortunately for hundreds of wild buffalo, this migration can mean the end of their lives; not because food is hard to find — winter is extremely challenging, but they are well-equipped to use their huge heads to “crater” through snow to get to the life-giving grasses below — but because the lower-elevation grasslands they seek are located in Montana where they enter a deadly conflict zone put in place by livestock interests.

As the buffalo begin their winter migration, BFC volunteers begin their own, returning to camp from all points of the compass to stand with the buffalo. The early snowfall necessitates the opening of our Gardiner camp along the Park’s north boundary, which we will do this Saturday; it’s been quite a few years since we opened up Gardiner camp this early. Patrols are preparing for another difficult season of documenting all actions made against the buffalo, monitoring their migration, and sharing our stories and first-hand experiences in an effort to end this war against wild buffalo. Will you join us?

In the Hebgen Basin, west of Yellowstone National Park, at least ten buffalo have already been killed by treaty hunters, and Montana’s state hunt will begin on Saturday, with other treaty hunts to follow. In addition to six months of combined state and treaty hunts, Yellowstone National Park, the Montana Department of Livestock, and even some tribal entities, are aiming to capture and kill hundreds more buffalo. Through hunting and slaughter, the Interagency Bison Management Plan agencies intend to kill nearly 1,000 Yellowstone buffalo. There are fewer than 5,000 left, and the Yellowstone population — the world’s most important — is made up of America’s last continuously wild herds. Ecologically extinct throughout their native range, and not yet federally protected, bison are endangered. In 2014 we filed a petition with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to protect wild bison under the Endangered Species Act, and sometime this fall the USFWS is expected to issue their finding. If they issue a negative finding, rejecting ESA protection — and no thanks to politics, we expect they will — we are prepared to take the next step.

Come stand with the buffalo if you can, help keep us on the front lines, and continue to spread the word to save these sacred herds.

Wild is the Way ~ Roam Free!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 11, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

Elvira Nascimento

Cyntia Beltrão reports from Brazil on what may be the country’s worst environmental disaster ever, at the Samarco open pit project jointly owned by Vale and BHP Billiton:

Last Thursday, November 5th, two dams containing mine tailings and waste from iron ore mining burst, burying the small historic town of Bento Rodrigues, district of Mariana, Minas Gerais state. The village, founded by miners, used to gain its sustenance from family farming and from labor at cooperatives. For many years, the people successfully resisted efforts to expel them by the all-powerful mining company Vale (NYSE: VALE, formerly Vale do Rio Doce, after the same river now affected by the disaster). Now their land is covered in mud, with the full scale of the death toll and environmental impacts still unknown.

Officially there are almost thirty dead, including small children, with several still missing. The press and the government hide the true numbers. Independent journalists say that the number of victims is much larger.

The environmental damage is devastating. The mud formed by iron ore and silica slurry spread over 410 miles. It reached one of the largest Brazilian rivers, the Rio Doce (“Sweet River”), at the center of our fifth largest watershed. The Doce River already suffers from pollution, silting of margins, cattle grazing in the basin land, and several eucalyptus plantations that drain the land. This year Southeastern Brazil, a region with a normally mild climate, endured a devastating drought. Authorities imposed water rationing on several major cities. Meanwhile, miners contaminate ground water and exploit lands rich in springs. The Doce River, once great and powerful, is now almost dry, even in its estuary. The mud of mining waste further injures the life of the river.

We do not know if the mud is contaminated by mercury and arsenic. Samarco / Vale says it isn’t, but we know that its components, iron ore and silica, will form a cement in the already dying river. This “cement” will change the riverbed permanently, covering the natural bed and artificially leveling its structure. The mud is sterile, and nothing will grow where it was deposited. A fish kill is already occuring. We do not know the full extent of impacts on river life or for those who depend on the river’s waters.

Soon the dirty mud will reach the sea, where it will cause further damage, to the important Rio Doce estuary and to the ocean.

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 7, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action

In early October, news emerged that India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change was blocking the implementation of a high-level government panel’s report on tribal rights that recommended the creation of stringent rules to safeguard indigenous people from displacement. Meanwhile, two state governments have begun implementing a much different set of guidelines — issued in August without any interference — that allow the private sector to manage 40 percent of forests for profit at the expense of indigenous forest dwellers. In addition, another ordinance passed this year will permit private corporations to easily acquire land and forests from indigenous communities and carry out ecologically harmful mining. These legislative and policy decisions are usually made without the knowledge of indigenous communities whose lives, livelihoods and ecosystems will be worsened by these irresponsible actions of the government. Hence, indigenous communities in Uttar Pradesh, a northern state and Odisha, in the east, are strengthening their organizing to protect their rivers, lands, forests and hills from “development” that would displace thousands of local residents and destroy the environment.“People from my community and I were beaten, detained or jailed unnecessarily for opposing tree felling in our forests, some years ago,” said Nivada Debi, a feisty 38-year-old woman from the Tharu Adivasi community in Uttar Pradesh. “We visited the police station multiple times for their release. The government did not assist the injured. Despite the police and government indifference, we will fight for our land and environment.”A mother of four children subsisting on the forests, Debi is active in grassroots resistance that started nearly 20 years ago and has grown into the All India Union of Forest Working People, or AIUFWP. The group is made up of many indigenous people who subsist on forests and are collectively protecting forests from poachers and encroachers.

Debi was among hundreds — from the AIUFWP, the allied Save Kanhar Movement and other resistance groups — who traveled to Lucknow in July 2015 for a rally protesting the continued incarceration of their comrades fighting land grabbing in other districts of Uttar Pradesh. Roma Malik, the AIUFWP deputy general secretary, and Sukalo Gond, an Adivasi, which means original inhabitant, were among those arrested on June 30, before they were to address a large public gathering about the illegal land acquisition for the Kanhar dam and the violent repression of its opponents by the state. Another member of AIUFWP, Rajkumari, who prefers to go by her first name, was jailed on April 21, after 39 Adivasis and Dalits, who are considered outside the caste hierarchy, were brutally shot at by the police during a peaceful protest on April 18. The demonstration, which began on April 14 — the birthday of B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian constitution and an icon for many Indians, particularly Dalits — was opposing the construction of a dam across the Kanhar river in the Sonbhadra district of southeastern Uttar Pradesh.

Rajkumari was released toward the end of July while Gond and Malik were freed in September. However, others are still imprisoned on fabricated charges. Courts are delaying hearing their cases or denying them bail.

AIUFWP members, some of whom were previously involved with other local resistance movements, have been actively opposing the construction of the Kanhar dam for years. It would submerge over 10,000 acres of land from more than 110 villages in Uttar Pradesh and the neighboring states of Chattisgarh and Jharkhand, displacing thousands of local people and disrupting their lives and livelihoods. The dam was approved by the Central Water Commission of India in 1976, but was abandoned in 1989 after facing fierce opposition, especially from the local people whose lives and ecosystem would be destroyed by the proposed dam. However, construction resumed in December 2014, violating orders to stop it from the National Green Tribunal — a government body that adjudicates on environmental protection, forest conservation and natural resource disputes. No social impact assessment was done, nor were the necessary environmental or forest clearances — mandated by the Forest Conservation Act — obtained by the state government.

“Since this dam can destroy our survival and also adversely impact the surroundings, we have been opposing its construction and related land acquisition for many years,” said Shobha, a determined 42-year-old Dalit. “On December 23, 2014, the police caned some of our comrades when we were peacefully protesting the revival of building the dam earlier that month. However, the police falsely accused some leaders of our struggle of attacking the sub-divisional magistrate.” Shobha, who also prefers to go only by her first name, is among the vocal leaders of a women’s agricultural laborers union, which has allied with AIUFWP, in the village of Bada.

Around 400 miles from Sonbhadra, in the Kalahandi and Rayagada districts of southern Odisha, live the Dongria Kondhs, an indigenous community of over 8,000 people. They have been fighting tirelessly to protect their sacred mountain, the nearly 5,000-foot high Niyamgiri, from large private corporations — like Vedanta Limited — that are trying to mine bauxite in the area to produce aluminum. Supporters of the Dongria Kondhs were arrested in Delhi on August 9 outside the Reserve Bank of India, as they peacefully highlighted Vedanta’s illegitimate and harmful mining in the Niyamgiri. Vedanta’s mining would violate the Forest Rights Act, which states that indigenous communities are entitled to remain in the forests — and utilize the produce, land and water in the forests — while conserving and protecting them.

“The Niyamgiri symbolizes a parent to our community,” said Sadai Huika, a steadfast 45-year-old Dongria Kondh woman from Tikoripada village. “While the streams that originate from it help our farming, the plants and grass that grows on it feed our cattle and goats. We cannot exist without it and will safeguard it from anyone trying to harm it.”

Huika and people from hundreds of villages near the Niyamgiri are active members of the Niyamgiri Protection Forum, which originated around 2003 to resist attempts by Vedanta to begin mining where the Kondhs live, with the support of the Odisha state government. At every one of the 12 village council meetings with government officers held in 2013 atop the Niyamgari, community members stated that they would not allow mining nearby.

Kumuti Majhi, an elderly Dongria Kondh man and one of the forum’s leaders, is among the few people who have traveled within and outside Odisha to advocate against mining and garner vital support for their struggle. He has met ministers to explain how significant the Niyamgiri is to his community and their reasons for safeguarding it.

By organizing protests locally and with allies around the world — and meetings with Vedanta’s shareholders and empathetic government officials, who the forum has enlightened about the need to protect the Niyamgiri — the group has stalled the mining.

“We know that extracting bauxite from the Niyamgiri will pollute our environment and also affect all living beings here,” Majhi said. “Hence, we will stop anyone coming to plunder the Niyamgiri, despite police harassment and false charges against us and our families.”

Pushpa Achanta is a Bangalore-based freelance journalist, blogger and writer on development and human interest issues. She is the lead author of a book titled Ripples: The Right to Water and Sanitation for Whom, published in July 2013 by the Indian Social Institute in Bangalore. Her articles have appeared in collections of essays and features on different subjects. She also enjoys penning verse, taking nature photography and mentoring youth.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 6, 2015 | Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the second in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the first part.

- Gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014.

- Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of local communities.

- With gold prices continuing to rise overall despite recent drops and Suriname’s political economy deeply entrenched in resource extraction, conservationists worry mining expansion will be hard to stop.

High gold prices combined with lax land use regulations have led to an explosion in mining in Suriname. A recent report by the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) finds that gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014, and is threatening the health and ways of life of many communities in the region.

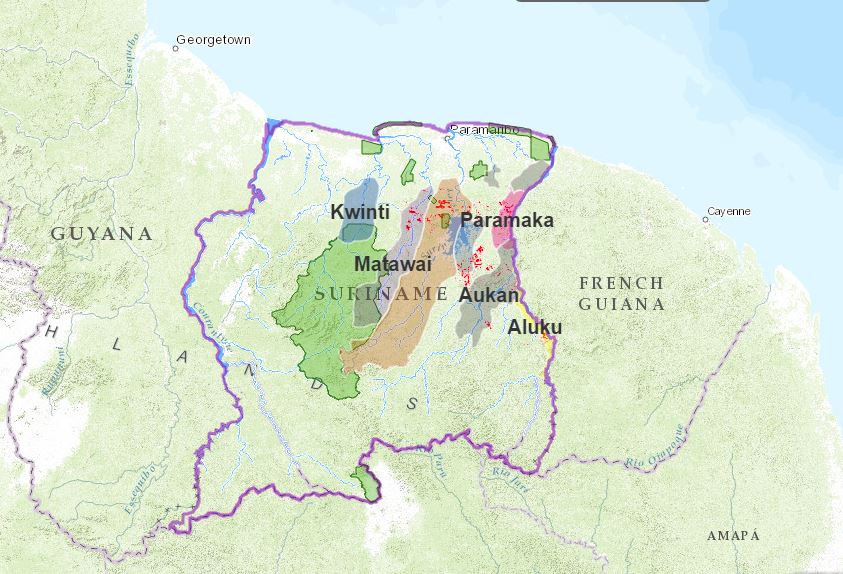

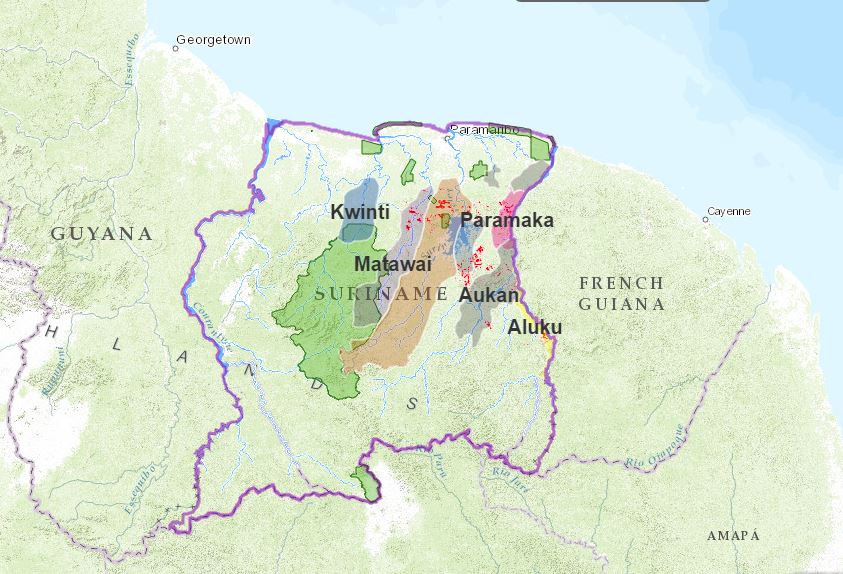

Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of the Maroons – descendants of formerly enslaved people of African heritage who escaped from plantations during Dutch colonial rule and established thriving communities in the country’s hinterlands after successfully fighting for their freedom.

Suriname’s six main Maroon communities all reside along rivers leading upstream deep into the rainforest, the report says. The majority of Maroons live in the central-eastern part of the country – where the mineral-rich Greenstone Belt and gold deposits are located. Through statistical analysis, the ACT discovered that encroachment of gold mining is significantly more severe within Maroon territories than outside of them. The team writes that only one Maroon community far from the Greenstone Belt is currently not seeing any gold mining on their lands.

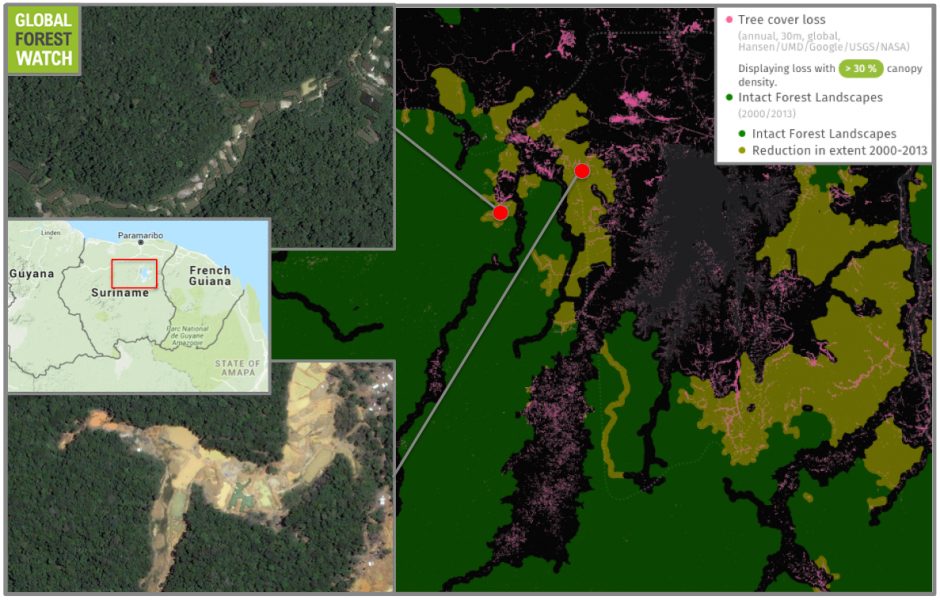

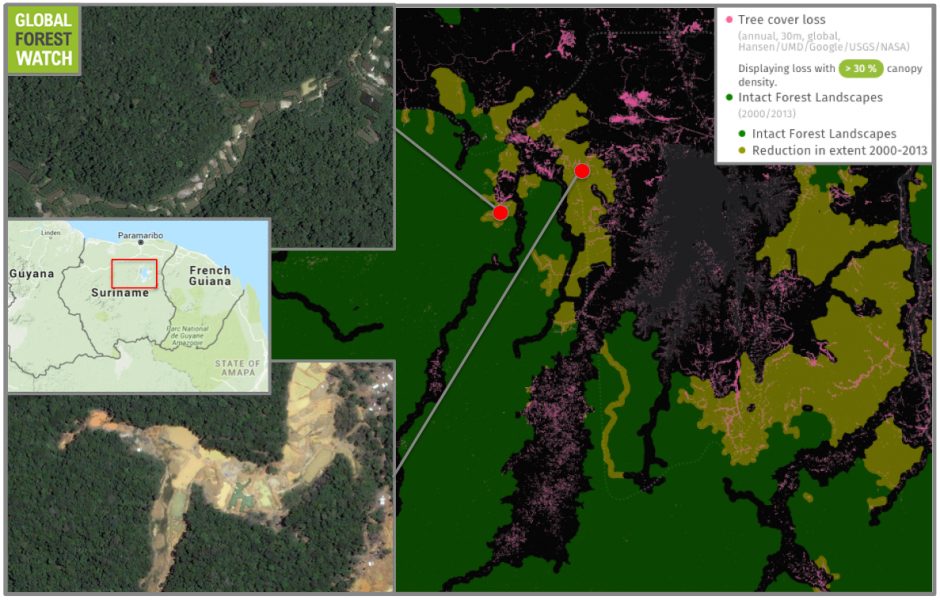

Suriname boasts large tracts of intact forest landscapes (IFLs), which are continuous, undisturbed areas of primary forest. However, Global Forest Watch shows significant IFL degradation, with the country experiencing nearly 17,000 hectares of tree cover loss in its IFLs between 2001 and 2014. Much of this is happening in areas with gold mining activity.

Mining extent (red) in Maroon-occupied areas. Image courtesy of the ACT.

For some Maroon groups, small-scale gold mining has become a major component of their landscape and their daily lives. In many of their villages – particularly in Paramaka, Aukan and Matawai communities – villagers have become economically dependent on gold mining. Anthropologist Marieke Heemskerk has shown that in some Maroon villages, 70 to 80 percent of households get their regular income from family members working in gold mines. Villagers with informal concessions are able to collect fees from the garimpeiros – the Brazilian miners – and others working on their lands, and some have become quite wealthy as a result.

The Matawai Maroons who live along the Saramacca River in central Suriname, are among the smallest of the Maroon communities in terms of population. Their territory covers about 560,000 hectares and many of their villages are among the most remote and least-known in the country. Consequently, the Saramacca River, the surrounding ecosystem and the villages themselves remained relatively quiet and peaceful while other Maroon communities were contending with the pressures of inland colonization and resource extraction.

The northern portion of the Matawai territory, however, is located in the reaches of the Greenstone Belt. Being close to populated settlements, they are easily accessible via roads. This has allowed rapid expansion, with a number of the northern Matawai villages located at ground-zero for Suriname gold mining.

“According to our calculations derived from deforestation data, 81.51% of all deforestation in the Matawai territory is due to gold mining,” the report says.

Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.

Four Matawai villages – Nyun Jakobkondre, Balen, Misalibi, and Bilawatra have been particularly impacted by the large gold mines that encircle them. In fact, much of the small-scale mining in the region is done by Maroons themselves, which is threatening their traditional livelihoods of hunting, fishing, woodworking, etc.

“As more Maroons in the Matawai community and elsewhere are becoming dependent on partaking in mining for household income, these and other local practices are eroding,” said Rudo Kemper, GIS and Web Development Coordinator for the ACT. “Many of the Matawai youth in particular are no longer as interested in traditional activities, as they know that there are lucrative profits to be made working in the mines.”

To make matters worse, mining activities has polluted waterways with mercury, which is used to separate the gold ore from sediment. Mercury can act as a neurotoxin, and has contaminated river fish, which are no longer safe to eat. Arable land is also threatened. According to Kemper, “in areas like Nyun Jakobkondre, the gold mining is taking place so close to the village that fertile land for cultivation is becoming scarcer.”

Nieuw Koffiekamp, a village settled by Maroons after it was relocated because of floods, is now located right in the middle of one of the most prosperous and mineral-rich veins of the Greenstone Belt. Known as Gros Rosebel, the area was one of the first industrial mining concessions in Suriname. Villagers have been using the area for sustainable livelihoods for generations, but the ACT report alleges they were neither consulted with nor informed about the concession. Years later, the government set up a task force dedicated to relocating the village once more. The village continues to fight for its existence, despite being literally fenced in by gold mining activity. Community members argue they have the right to extract resources from their own land and thus participate in small-scale gold mining.

Even Brownsberg Nature Park, a 14,000-hectare reserve and popular tourist destination, hasn’t been spared from the clutches of mining. From early on, gold miners have been active within its boundaries, where an estimated 924 hectares of primary forest has been lost to gold mining. In 2012, deforestation in the park reached an all-time high, with 200 hectares of forest cleared. In that same year, public awareness about mining inside Brownsberg began increasing when WWF–Guianas published a report with aerial photography of the damage to the park. “Since then,” Kemper said, “the rates of small-scale mining in the boundaries of the park have dropped somewhat, although deforestation caused by mining in the park [continues] to expand.”

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining boom threatens communities in Suriname

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 4, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the first in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the second part.

- High gold prices are leading to an increase in mining activity.

- Mining activities threaten Suriname’s primary forests, some of the most-intact in South America.

- Mercury released from the mining process can be toxic, and is showing up in human population centers far downstream.

Record high gold prices over much of the past decade have triggered a massive gold rush across much of the Amazon basin, resulting in the destruction of thousands of hectares of pristine rainforest and the contamination of major rivers with toxic heavy metals. A newly released report published by the Amazon Conservation Team titled “Amazon Gold Rush: Gold Mining in Suriname” explores the rapid expansion and impacts of gold mining in Suriname through cartography and digital storytelling.

It finds that from 2000 to 2014, the extent of gold mining in the South American country increased by 893 percent.

While the Amazon rainforests of Brazil and Peru are well-known, Suriname’s vast and ancient rainforests remain one of the world’s best-kept natural secrets, according to the online report. But demand for the age-old elemental metal threatens to destroy them.

“According to our calculations, deforestation caused by gold mining has been growing steadily since the turn of the century and rapidly in the past five years,” GIS and Web Development Coordinator at the Amazon Conservation Team, Rudo Kemper told mongabay.com. The average rate of deforestation since 2000 is close to 3,000 hectares per year, but in 2014 an estimated 5,712 hectares of forest cover was lost to gold mining, he said. The REDD+ for the Guiana Shield regional collaborative study on gold mining shows similar trends, reporting a near-doubling (97 percent increase) of deforestation from 2008 to 2014 and attributing a total of 53,668 hectares of deforestation to gold mining in 2014.

Compared to many other South American countries, Suriname still holds much of its forest cover. According to Global Forest Watch, Suriname lost 0.7 percent of its tree cover from 2001 through 2014 – a small proportion compared to Brazil’s 6.9 percent. However, Suriname’s intact forest landscapes – large, continuous areas of primary forest – do show degradation since 2000.

The Guiana Shield, as Kemper puts it, is one of three cratons of the South American tectonic plate. “It is a tropical rainforest region covered with unique table-top mountains called tepuis,” he said. “It has the largest expanse of undisturbed tropical rainforest in the world, and one of the highest rates of biodiversity.” Suriname is among the most forested countries in the world, as the report highlights. In 2012, 95 percent of the country’s entire area was classified as forest. Globally surpassed only by its neighbor French Guiana, Suriname’s pristine rainforest harbors numerous unique species of fauna like the Guianan cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola rupicola), the famous blue poison dart frog (Dendrobates tinctorius), the red-faced spider monkey (Ateles paniscus), and the pale-throated sloth (Bradypus tridactylus). Jaguars, tapirs, and giant anteaters also call the region home. The mineral-rich Greenstone Belt region, where most of the gold mining in Suriname takes place, is primarily composed of the forested highlands of the Guiana Shield. Conservationists worry that deforestation caused by rapidly expanding gold mining activities is negatively impacting the habitat of many unique species.

Suriname rainforest. Photo courtesy of the Amazon Conservation Team.

Since the 1960s, development and resource extraction incursions into the country’s interior have become commonplace. These encroachments have taken the form of dam-building, logging, bauxite mining, and as of the turn of the century, small-scale and industrial gold mining, the report says. Given that it is one of the world’s smallest countries, Suriname’s annual rate of gold production might not compare to that of larger countries like South Africa, China, Russia or Peru. But relative to its land area, Suriname actually ranks tenth in global gold production.

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining explodes in Suriname, puts forests and people at risk.