by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 29, 2013 | Climate Change

By John Vidal / The Guardian

The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has reached 399.72 parts per million (ppm) and is likely to pass the symbolically important 400ppm level for the first time in the next few days.

Readings at the US government’s Earth Systems Research laboratory in Hawaii, are not expected to reach their 2013 peak until mid May, but were recorded at a daily average of 399.72ppm on 25 April. The weekly average stood at 398.5 on Monday.

Hourly readings above 400ppm have been recorded six times in the last week, and on occasion, at observatories in the high Arctic. But the Mauna Loa station, sited at 3,400m and far away from major pollution sources in the Pacific Ocean, has been monitoring levels for more than 50 years and is considered the gold standard.

“I wish it weren’t true but it looks like the world is going to blow through the 400ppm level without losing a beat. At this pace we’ll hit 450ppm within a few decades,” said Ralph Keeling, a geologist with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography which operates the Hawaiian observatory.

“Each year, the concentration of CO2 at Mauna Loa rises and falls in a sawtooth fashion, with the next year higher than the year before. The peak of the sawtooth typically comes in May. If CO2 levels don’t top 400ppm in May 2013, they almost certainly will next year,” Keeling said.

CO2 atmospheric levels have been steadily rising for 200 years, registering around 280ppm at the start of the industrial revolution and 316ppm in 1958 when the Mauna Loa observatory started measurements. The increase in the global burning of fossil fuels is the primary cause of the increase.

The approaching record level comes as countries resumed deadlocked UN climate talks in Bonn. No global agreement to reduce emissions is expected to be reached until 2015.

“The 400ppm threshold is a sobering milestone, and should serve as a wake up call for all of us to support clean energy technology and reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, before it’s too late for our children and grandchildren,” said Tim Lueker, an oceanographer and carbon cycle researcher with Scripps CO2 Group.

The last time CO2 levels were so high was probably in the Pliocene epoch, between 3.2m and 5m years ago, when Earth’s climate was much warmer than today.

From The Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/apr/29/global-carbon-dioxide-levels

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 26, 2013 | Mining & Drilling

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

The first Tar Sands mine in the United States is an open wound on the landscape: a three acre pit, the bottom puddled with water and streaked with black tar. Berms of broken earth a hundred feet tall stand on all sides. To the north and south, Seep Ridge Road – a narrow, rutted, dirt affair – is in the midst of a state-funded transfiguration into a 4-lane paved highway that may soon be clogged with afternoon traffic jams of oil tankers and construction equipment. Clearcuts and churned soil stretch to either side of the road, marking the steady march of progress.

This is the Uintah Basin of eastern Utah – a rural county, known for providing the best remaining habitat in the state for Rocky Mountain Elk, White Tailed Deer, Black Bear, and Cougar. In the last decade, it’s become the biggest oil-extraction region on the state, and in the last five years fracking has exploded. There are over 10,000 well pads in the region. And now, the Tar Sands are coming.

Thirty two thousand acres of state lands situated on the southern rim of the basin – some 50 square miles – have been leased for Tar Sands extraction. If all goes according to plan, the mine at PR Springs that I’m looking at would produce 2,000 barrels of oil per day by late this year, with planned increases to 50,000 barrels per day in the future.

Dozens of similar mines are planned across the whole region. Along with their friends in state and local governments, energy corporations are collaborating to turn this region into an energy colony – a sacrifice zone to the gods of progress, growth, and desecration.

Twelve to 19 billion barrels of recoverable tar sands oil is estimated to be located under the rocky bluffs of eastern Utah, mostly in the southern portion of Uintah County. It’s a drop in the bucket for global production, but it means total biotic cleansing for this land.

Crude oil, tar sands, oil shale, and fracking: these are the wages of a dying way of life, and the ozone pollution that is already reaching record levels in this remote, sparsely-populated region is evidence of the moral bankruptcy of this path. There is no claim to morality in this path. It leads only to death, for us and for all life.

Alongside the test pit and scattered throughout the landscape, drill pads for seismologic assessment and roads to the pads have already been cut through the forests and shrubs, leaving behind a patchwork of shattered sagebrush and mangled juniper – testament to the Earth-crushing consequences of this “development”.

Situated at 8,000 feet of elevation, this wild region is called the Tavaputs Plateau. Unmarked, often muddy dirt roads make travel dangerous, and deep valleys plunge thousands of feet to the rivers that drain the region – the White River to the north, and the Green to the west. Both flow into the Colorado River, which provides drinking water for more than 11 million people downstream.

Resistance to tar sands and oil shale projects in Utah dates at least back to the 1980’s, when David Brower and other alienated conservationists fought off the first round of energy projects in this region. Thirty years later, the fight is on again.

It is likely that the PR Springs mine will be the bellwether of Tar Sands mining in the United States. If the project is stopped, it will be a major blow to the hopes of the Tar Sands industry in this country, while if it goes ahead smoothly, it may open the floodgates for more projects in Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming.

That is why resistance to this project is so important. That resistance is building. Strong organizations based in Moab (Before it Starts and Living Rivers) and Salt Lake City (Utah Tar Sands Resistance and Peaceful Uprising) are working together to organize against the project, and individuals and allies have been scouting the site and preparing to take action this summer.

Campouts at PR Springs will take place in May and June with more gatherings likely throughout the summer. An action camp will take place the fourth week of July, with activists and concerned people from across the country gathering to support one another, prepare for action, and make plans. All are welcome.

Time is short. There is no time to waste, and we are few. If we are to succeed, we will need your help, your solidarity.

Looking out across a landscape that might soon be a wasteland, my gaze wanders across the juniper, scrub oak, and sagebrush that wrap gently over the hillsides and drop into the valleys. The setting sun casts waning light on the treetops, and a small herd of Elk climbs a ridge in the distance and disappears into the brush. Overhead, the few clouds in the broad sky fade from red to deep purple, then to darkness.

The last birds of the day sing their goodnight songs, and the stars begin to appear, thousands of them, lighting up the night sky and casting a dull glow across the countryside. I take a deep breath, tasting the cool night air spiced with the scents of the land.

The bats are out, flitting about snatching tasty morsels out of midair. I can hear their voices. They are calling to me. Tiny voices carrying across miles to whisper in your ear like the tickle of a warm breeze. “Fight back,” they say. “Please, fight back. This is our home. We need you to do what it takes to stop this. Whatever it takes to stop this. Whatever it takes.”

Whatever it takes.

_____________________________________________________

Companies involved in Tar Sands projects in the Utah include Red Leaf Resources (which also works in the Oil Shale business and is based in Salt Lake City), MCW Energy Group, Crown Asphalt Ridge LLC, and U.S. Oil Sands, a Calgary, Alberta based company.

Red Leaf Resources is currently working on a shale oil operation in the same region as the PR Springs mine, which could eventually produce 10,000 barrels of oil per day. Other large oil shale operations are planned for region by the Estonian company Enefit.

You can learn more about the resistance to Utah Tar Sands projects at the following websites:

http://www.tarsandsresist.org/

http://www.peacefuluprising.org/topic/current-campaigns/stop-tar-sands

Max Wilbert is a writer and community organizer living in occupied Goshute territory otherwise known as Salt Lake City, UT. He originally hails for occupied Duwamish territory known as Seattle, and organizes primarily with the Great Basin Chapter of Deep Green Resistance to fight injustice and promote strategies towards the dismantling of industrial civilization.

You can contact Max Wilbert at greatbasin@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 26, 2013 | Mining & Drilling, Worker Exploitation

By Mongabay

Mobile device giant Samsung has admitted to using tin sourced from a controversial mining operation on the Indonesian island of Bangka, where unregulated mining kills 150 miners a year and causes substantial environmental damage, reports The Guardian and Mongabay-Indonesia.

Samsung’s admission came after a campaign by Friends of the Earth, which led to nearly 16,000 customers contacting the company. In an email sent the customers and the NGO, Samsung said it is investigating the matter.

“While we do not have a direct relationship with tin suppliers from Bangka Island, we do know that some of the tin that we use for manufacturing our products does originate from this area,” Samsung said. “We are also undertaking a thorough investigation of our supply chain in the region to better understand what is happening, and what part we play.”

Bangka and neighboring island Belitung account for about 90 percent of Indonesia’s tin production. Mining on the islands involves more than half the population, but is largely unregulated, leading to a raft of ills. An investigation last year by the Guardian and Friends of the Earth found widespread use of child labor, clearing of forests, and degradation to coral reefs. Accidents kill scores of people each year.

After the investigation, Friends of the Earth called on Samsung and Apple to disclose whether they use tin from Bangka in their smartphones and tablets. To date only Samsung has admitted to sourcing Bangka tin, a point highlighted by Friends of the Earth.

“It’s great Samsung has taken an industry lead by tracking its supply chains all the way to Indonesia’s tin mines and committing to taking responsibility for helping tackle the devastating impact that mining tin for electronics has on people and the environment,” said Craig Bennett of Friends of the Earth in a statement.

“Rival Apple is already playing catch-up on the high street in terms of smartphone sales – it’s time it followed Samsung’s lead by coming clean about its whole supply chains too.”

From Mongabay: “Samsung admits to using tin linked to child labor, deforestation; Apple mum on sourcing“

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 25, 2013 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

On April 19th, myself and other organizers from the Salt Lake City community attended the Morning Energy Update, a meeting hosted by the Utah State Office of Energy Development. The meeting was held in a small conference room at the World Trade Center Utah building.

The room was full – us five or six activists mixed in with energy industry businesspeople, State and County officials, and one or two journalists. I sat next to Cody Stewart, the energy advisor to Gary Herbert, the Governor of the State of Utah.

The main topic of the meeting was the development of Oil Shale in eastern Utah, in Uintah and Grand Counties – areas already hard hit by oil and gas extraction and threatened with Tar Sands extraction.

Rikki Hrenko, the CEO of Enefit American Oil (an Estonian shale oil corporation) was the keynote. She presented about the “economic sustainability” and moderate environmental impact of the project.

I responded with the following statement:

http://picosong.com/FkPw/

Any claims about oil shale having a low impact are simply ridiculous – we are talking about strip mining a vast area of wild lands in the watershed of the Colorado, whose water is already so taxed by cities and agriculture that the river never reaches the ocean. Instead, it simply turns into a stream, then a trickle, then cracked mud for the last 50 miles.

The WorldWatch Institute states that oil shale is simply an awful idea:

“Studies conducted so far suggest that oil shale extraction would adversely affect the air, water, and land around proposed projects. The distillation process would release toxic pollutants into the air—including sulfur dioxide, lead, and nitrogen oxides. Existing BLM analysis indicates that current oil shale research projects would reduce visibility by more than 10 percent for several weeks a year. And NRDC states that in a well-to-wheel comparison, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from oil shale are close to double those from conventional crude, with most of them occurring during production. According to the Rand Corporation, producing 100,000 barrels of oil shale per day would emit some 10 million tons of GHGs.

The BLM reports that mining and distilling oil shale would require an estimated 2.1 to 5.2 barrels of water for each barrel of oil produced—inputs that could reduce the annual flow of Colorado’s White River by as much as 8.2 percent. Residues that remain from an in-situ extraction process could also threaten water tables in the Green River Basin, the agency says.

NRDC notes that the infrastructure needed to develop oil shale would impose equally serious demands on local landscapes. The group warns that impressive arrays of wildlife would be displaced as land is set aside for oil shale development. And it says that while open pit mining would scar the land, in-situ extraction would require leveling the land and removing all vegetation.

In addition to the environmental impacts of oil shale, vast amounts of energy are required to support production. In Driving it Home, NRDC cites Rand Corporation estimates that generating 100,000 barrels of shale oil would require 1,200 megawatts of power—or the equivalent of a new power plant capable of serving a city of 500,000 people. Proponents of oil shale have a stated goal of producing one million barrels of the resource per day.”

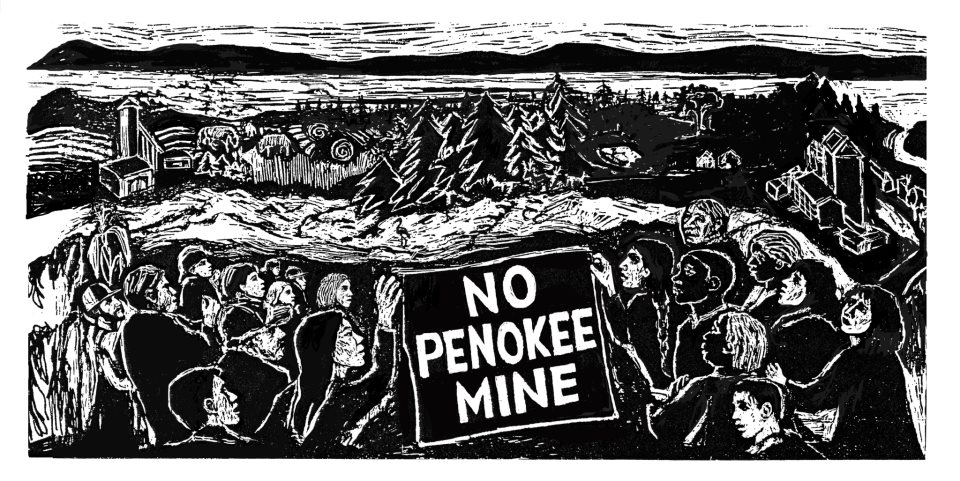

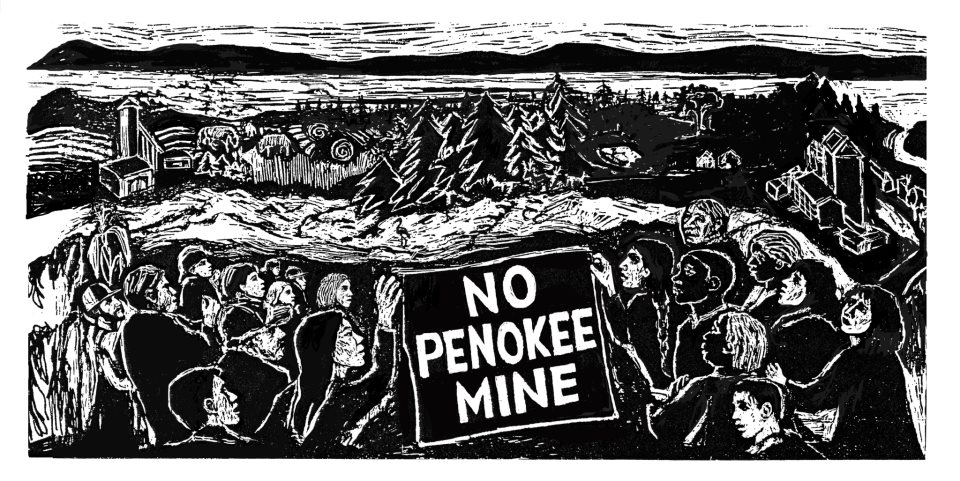

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 24, 2013 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

By Thistle Pettersen and Beth Ulion / Deep Green Resistance

A proposed iron mining effort would create the largest open pit mine in the world in northern Wisconsin.The 22,000 acres of mountain-top removal-style strip mining would potentially dump millions of tons of waste rock into the headwaters of the Bad River, polluting everything downstream including beautiful Copper Falls State Park, the Bad River Ojibwe Reservation, crucial wetland Kakagon Sloughs, and Lake Superior.

Many local residents fear that the huge mine will eat into nearby sulfide-mineral deposits, causing sulfuric acid mine drainage to leach into the surrounding watershed for decades.

The Wisconsin State legislature recently slashed environmental regulations in an attempt to make an easier entry for Gogebic Taconite (G-Tac), a Florida-based company owned by the Cline Group, is also well known for its coal mining operations in Illinois and West Virginia.

This is just one struggle in a worldwide battle against extreme resource extraction – but this time, it’s one we can win. Activists have a good head start, and there is a lot of dedicated support for those who are planning to occupy the Penokee Hills to deliver a message to G-Tac: we are drawing a line in the sand, and they will not be allowed one inch of this sacred land.

Bad River Tribal members are asking for solidarity from allies all over the Great Lakes Region.

Activists will gather at the Central Wisconsin Action Camp May 17-19th in Stevens Point, WI.

This is a great opportunity to meet others from around Central and South Wisconsin and throughout the midwest, and build direct-action skills for this historic struggle.

The crew organizing this event could really use a little help, too! Especially for those of you who are in or near Stevens Point or Madison, assistance in organizing logistics like camp setup, food, etc, as well as additional skill trainings, are greatly appreciated!

As capacity may be somewhat limited, and with the intention of building a solid group of anti-mining activists who can move into the future together, organizers are asking that you please register on the website:

centralwiactioncamp.wordpress.com

centralwiactioncamp@gmail.com

If you are unable to make it to the action camp, you can still plug in by traveling even farther north the following weekend, May 24th-26th for a benefit variety show and camp out at Copper Falls State Park. The variety show fund raiser will be at the Bad River Lodge and Casino on Friday night, the 24th. Money raised at this community-building event will go towards the Penokee Hills Education Project to defend the land from harmful mining. The Red Cliff hoop dancers, Thistle and Thorns, and Barbara With are all acts on this bill that will make it a very special night of performances and comradeship with locals.

The campout is being organized by members of the Bad River Tribe and will include tours of the land where the mine is slated to be put in. Mike Wiggins, chair of the Bad River, will greet and spend time with campers. It will be a beautiful and educational weekend in the great north woods!

If you are interested in attending either of these two weekends or both of them, please contact DGR member Thistle Pettersen to plug into ride shares happening from Madison. thistle@riseup.net.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 21, 2013 | ANALYSIS, Mining & Drilling

By Joshua Headley / Deep Green Resistance New York

We ought not at least to delay dispersing a set of plausible fallacies about the economy of fuel, and the discovery of substitutes [for coal], which at present obscure the critical nature of the question, and are eagerly passed about among those who like to believe that we have an indefinite period of prosperity before us. –William Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question (1865)

There are, at present, many myths about green energy and its efficiency to address the demands and needs of our burgeoning industrial civilization, the least of which is that a switch to “renewable” energy will significantly reduce our dependency on, and consumption of, fossil fuels.

The opposite is true. If we study the actual productive processes required for current “renewable” energies (solar, wind, biofuel, etc.) we see that fossil fuels and their infrastructure are not only crucial but are also wholly fundamental to their development. To continue to use the words “renewable” and “clean” to describe such energy processes does a great disservice for generating the type of informed and rational decision-making required at our current junction.

To take one example – the production of turbines and the allocation of land necessary for the development, processing, distribution and storage of “renewable” wind energy. From the mining of rare metals, to the production of the turbines, to the transportation of various parts (weighing thousands of tons) to a central location, all the way up to the continued maintenance of the structure after its completion – wind energy requires industrial infrastructure (i.e. fossil fuels) in every step of the process.

If the conception of wind energy only involves the pristine image of wind turbines spinning, ever so wonderfully, along a beautiful coast or grassland, it’s not too hard to understand why so many of us hold green energy so highly as an alternative to fossil fuels. Noticeably absent in this conception, though, are the images of everything it took to get to that endpoint (which aren’t beautiful images to see at all and is largely the reason why wind energy isn’t marketed that way).

Because of the rapid growth and expansion of industrial civilization in the last two centuries, we are long past the days of easy accessible resources. If you take a look at the type of mining operations and drilling operations currently sustaining our way of life you will readily see degradation and devastation on unconscionable scales. This is our reality and these processes will not change no matter what our ends are – these processes are the degree with which “basic” extraction of all of the fundamental metals, minerals, and resources we are familiar with currently take place.

In much the same way that the absurdities of tar sands extraction, mountaintop removal, and hydraulic fracturing are plainly obvious, so too are the continued mining operations and refining processes of copper, silver, aluminum, zinc, etc. (all essential to the development of solar panels and wind turbines).

It is not enough – given our current situation and its dire implications – to just look at the pretty pictures and ignore everything else. All this does, as wonderfully reaffirming and uplifting as it may be, is keep us bound in delusions and false hopes. As Jevons affirms, the questions we have before us are of such overwhelming importance that it does no good to continue to delay dispersing plausible fallacies. If we wish to go anywhere from here, we absolutely need uncompromising (and often brutal) truth.

A common argument among proponents of supposed “green” energy – often prevalent among those who do understand the inherent destructive processes of fuels, mining and industry – is that by simply putting an end to capitalism and its profit motive, we will have the capacity to plan for the efficient and proper management of remaining fossil fuels.

However, the efficient use of a resource does not actually result in its decreased consumption, and we owe evidence of that to William Stanley Jevons’ work The Coal Question. Written in 1865 (during a time of such great progress that criticisms were unfathomable to most), Jevons devoted his study to questioning Britain’s heavy reliance on coal and how the implication of reaching its limits could threaten the empire. Many covered topics in this text have influenced the way in which many of us today discuss the issues of peak oil and sustainability – he wrote on the limits to growth, overshoot, energy return on energy input, taxation of resources and resource alternatives.

In the chapter, “Of the economy of fuel,” Jevons addresses the idea of efficiency directly. Prevalent at the time was the thought that the failing supply of coal would be met with new modes of using it, therefore leading to a stationary or diminished consumption. Making sure to distinguish between private consumption of coal (which accounted for less than one-third of total coal consumption) and the economy of coal in manufactures (the remaining two-thirds), he explained that we can see how new modes of economy lead to an increase of consumption according to parallel instances. He writes:

The economy of labor effected by the introduction of new machinery throws laborers out of employment for the moment. But such is the increased demand for the cheapened products, that eventually the sphere of employment is greatly widened. Often the very laborers whose labor is saved find their more efficient labor more demanded than before.

The same principle applies to the use of coal (and in our case, the use of fossil fuels more generally) – it is the very economy of their use that leads to their extensive consumption. This is known as the Jevons Paradox, and as it can be applied to coal and fossil fuels, it so rightfully can be (and should be) applied in our discussions of “green” and “renewable” energies – noting again that fossil fuels are never completely absent in the productive processes of these energy sources.

We can try to assert, given the general care we all wish to take in moving forward to avert catastrophic climate change, that much diligence will be taken for the efficient use of remaining resources but without the direct questioning of consumption our attempts are meaningless. Historically, in many varying industries and circumstances, efficiency does not solve the problem of consumption – it exasperates it. There is no guarantee that “green” energies will keep consumption levels stationary let alone result in a reduction of consumption (an obvious necessity if we are planning for a sustainable future).

Jevons continues, “Suppose our progress to be checked within half a century, yet by that time our consumption will probably be three or four times what it now is; there is nothing impossible or improbable in this; it is a moderate supposition, considering that our consumption has increased eight-fold in the last sixty years. But how shortened and darkened will the prospects of the country appear, with mines already deep, fuel dear, and yet a high rate of consumption to keep up if we are not to retrograde.”

Writing in 1865, Jevons could not have fathomed the level of growth that we have attained today but that doesn’t mean his early warnings of Britain’s use of coal should be wholly discarded. If anything, the continued rise and dominance of industrial civilization over nearly all of the earth’s land and people makes his arguments ever more pertinent to our present situation.

Based on current emissions of carbon alone (not factoring in the reaching of tipping points and various feedback loops) and the best science readily available, our time frame for action to avert catastrophic climate change is anywhere between 15-28 years. However, as has been true with every scientific estimate up to this point, it is impossible to predict that rate at which these various processes will occur and largely our estimates fall extremely short. It is quite probable that we are likely to reach the point of irreversible runaway warming sooner rather than later.

Suppose our progress and industrial capitalism could be checked within the next ten years, yet by that time our consumption could double and the state of the climate could be exponentially more unfavorable than it is now – what would be the capacity for which we could meaningfully engage in any amount of industrial production? Would it even be in the realm of possibility to implement large-scale overhauls towards “green” energy? Without a meaningful and drastic decrease in consumption habits (remembering most of this occurs in industry and not personal lifestyles) and a subsequent decrease in dependency on industrial infrastructure, the prospects of our future are severely shortened and darkened.

BREAKDOWN is a biweekly column by Joshua Headley, a writer and activist in New York City, exploring the intricacies of collapse and the inadequacy of prevalent ideologies, strategies, and solutions to the problems of industrial civilization.

Photo by Andreas Gücklhorn on Unsplash