by DGR News Service | May 23, 2019 | Alienation & Mental Health, Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy

By Elisabeth Robson / Art for Culture Change

On May 9, 2019 Blue Origin — Jeff Bezos’ space exploration company — posted this video of Jeff Bezos speaking at the Going to Space to Benefit Earth event. One of the visions of Blue Origin, as outlined on the web site, and the focus of Mr. Bezos’ presentation is that millions of people must live and work in space in order to “preserve Earth” and that we will “go to space to tap its unlimited resources and energy.”

He begins his presentation by making some true statements — that the Earth is not infinite (who knew!) and will eventually run out of energy for our use (again, who knew!). Mr. Bezos then quickly veers into human supremacy in the extreme, with a couple of innocuous sounding but telling remarks: that our lives are better than our parent’s lives, which were better than our grandparent’s lives (really better? Or just more energy intensive?) — completely ignoring all the non-humans we share this planet with — and that we could power our culture’s current energy needs if only we covered Nevada in solar cells. “It is mostly desert, anyway,” he says, ignoring the fact that deserts are in fact teeming with amazing life of all kinds from beautiful desert flowers to lizards, birds, tortoises, and so many more; ignoring the fact that solar farms in Nevada and other areas are bulldozed of all life before the toxic and deadly shining solar cells are installed.

As Mr. Bezos correctly points out, if we continue growing (GDP, energy use, etc.) at 3% a year, our historical trend in the modern era, we’d have to cover the entire surface of the Earth with solar panels to supply our energy needs in 200 years. Unintentionally, he’s hit upon a big problem with renewables: the land use requirements are unsustainable, and aside from the fact that along with running out of fossil fuel energy, we will eventually run out of the raw materials to make solar cells, wind turbines, batteries, smart grids, and so on long before 200 years passes. Of course, as he says, it is ridiculous to cover the Earth with solar panels, so we need something else.

Something else will include efficiency: our technology will continue to become more efficient, but Mr. Bezos acknowledges that growth in energy use will far outstrip energy efficiency. This relationship between greater efficiency and greater resource use is known as Jevons’ Paradox, discovered by William Stanley Jevons in 1865. Energy efficiency never reduces the amount of energy we use, because the more efficient our devices and cars and lighting and heating become, the cheaper they get, and the more we use. One example Mr. Bezos uses is air transportation: 50 years ago it took 109 gallons of fuel to fly one person from LA to NYC; today it takes only 24 gallons. And indeed, air travel is growing faster than any other transportation sector and is expected to double in the next 20 years, far outstripping the gains in efficiency made by airline companies. Efficiency gains just lead to more growth.

So, yet again, we need something else. Mr. Bezos never questions that growth is bad. He never suggests that maybe we should de-grow our population, our economy, our consumption, anything. He never contemplates that growth might not always be a good thing if it leads to the suffering of multitudes. No, he charges on assuming that growth is what’s best for everyone. Of course he does. As the CEO of amazon.com he is the embodiment of growth at all costs, including the lives of his own employees.

Does he even for a second think about the lives of non-humans at all? I don’t think so.

Unlimited demand + limited resources = rationing. This is the equation Mr. Bezos shows the audience, and he is correct. But rather than suggest we limit our demand, he focuses on how awful the rationing will be. According to him, that rationing means our children’s lives will be worse than our parent’s lives, and our grandparent’s lives. Again, I am blown away by the human supremacy of this thinking. It assumes that our lives have indeed, until now, been getting better. Which assumes that “our” means humans, because it surely cannot mean non-humans, whose lives have been getting demonstrably worse. Much worse. And which humans is he talking about? Clearly only the humans in the so-called Western developed world, because most humans on this planet have more recently been stripped of their land and livelihoods by colonization and “sustainable development”, and forced into menial, poverty-level jobs in factories, mines, and oil fields where their lives are demonstrably worse than they were before. For proof of this, simply imagine (or better yet, read the stories about) the life of a Native American Indigenous person who lived free on the land before white colonization and genocide and compare that with the life of a Native American relegated to living in poverty on a reservation with no access to land for traditional use, clean water, clean air, or cultural sites and activities. Mr. Bezos is arguing, as all techno-utopians do, that progress is always good. Only for people like you, Mr. Bezos.

And what is wrong with rationing? Well, god-forbid, it means we’d have to use less of everything we’re accustomed to using now. (Rich) Americans — 5% of the global population — would have to stop using the 25% of the resources on this planet that we use now. The horror! Cutting back and using less is fundamentally anathema to the American Dream(TM) — the idea that if we just work hard enough we can all achieve that fantasy of progress: having more money, owning more stuff, and of course, the unarticulated implication of using more energy that goes with that. “More” is the stuff American Dreams are made of.

The choice Mr. Bezos presents us with is between “stasis and rationing” and “dynamism and growth”. For Mr. Bezos, the choice is easy: we want dynamism and growth.

And here’s the good news: if we move out into space, we’ll have access to more! To unlimited resources!

Mr. Bezos’ solution to continued dynamism and growth is O’Neill colonies: giant tubes in space filled with a million people each. Here’s what he envisions this would look like:

[see photo here]

These will be easy to get to from Earth, easy to move amongst so we can visit our friends and neighbors. We can have the atmosphere of the best day on Hawai’i, the best cities, the best recreational spaces (complete with a deer and a bird flying over!). We can have it all, if we are willing to leave the planet behind, willing to forgo our “planetary chauvinism” as he (and a clip from Isaac Asimov) says.

Earth will, according to Bezos, be zoned for “residential”, “light industry” and people going to college. That’s weird. Why would people want to go to college on the planet, but not on the colony? He never says why. He also doesn’t mention “other species” in his zoning plans for Earth… at all. Or forests, rivers, mountains, glaciers, prairies, or wild places of any kind. Or how we’ll go about cleaning up the pollution and what will be no longer needed nuclear power plants, roads, buildings, and so much more we’ve left in our wake. He just says Earth “will be a beautiful place that people will visit.”

A trillion humans in space means a thousand Einsteins and a thousand Mozarts, according to Bezos. He doesn’t mention a thousand white rhinos, or a thousand passenger pigeons, or a thousand great auks. Of course not, because — oops! — we already killed off those species with our insatiable greed and inability to set limits on ourselves. As if a beautiful sunset isn’t as valuable as a Mozart concerto, and a thousand physics geniuses is somehow better than an entire species. Mr. Bezos claims this would be a great civilization. Only for people who care only about people, Mr. Bezos. Yes, there are a still a few of us who care about more than that.

Mr. Bezos says it won’t be up to him to build this future; it will be up to the (presumably younger) people he points to in the front row. It will be those people and their children and grandchildren, those people who will need to create the companies and the infrastructure to move to space… well they’d better hurry because we have only a couple of decades to get our CO2 emissions down to zero to avoid catastrophic climate change, and I’m not sure you can build a million colonies in space each big enough to hold a million people in two decades. Perhaps Mr. Bezos envisions that all of Earth’s remaining resources will be used up in this process? In which case it is unlikely that Earth will be a “beautiful place to visit” once we’re done building these big metal tubes in space.

The rest of the presentation is an advertisement for Blue Origin and how the company is putting all the basic infrastructure — the road to space — into place so that future generations can take it from there, with gratuitous phallic images of rockets launching into space accompanied by rousing movie music. Jeff Bezos’ childhood fantasy come true.

At no time in this entire presentation does Mr. Bezos mention non-human species, except implicitly when he mentions (and shows fantastical pictures of) “recreational opportunities” and “agriculture” in the colonies. It is as if, for Bezos, “nature” doesn’t exist except for recreation and food. Who, I want to ask him, is going to be responsible for building the web of life on these colonies so his deer and his bird and the pollinators (not shown) in the colonies will actually exist for more than a few weeks, days, or hours? Unfortunately, knowing what we know about Jeff Bezos, it is entirely possible that the graphical rendering of the colonies shows a robotic deer and a robotic bird, and that pollination occurs entirely via miniature drones. And what about the soil in which the plants in the “agriculture” areas and the trees shown in the “recreational” spaces grow? It is likely that the soil, too, is artificial, and artificially fertilized… oops! Synthetic fertilizer is made from petroleum products, which implies that either we find fossil fuels out in space somewhere (where we’ll be putting all the “heavy industry” of the future, according to Bezos), or that we continue mining the Earth for fossil fuels so we can grow food in space. Or maybe once established, we’ll all be pooping out the fertilizer in these closed-circuit biospheres in space. Because that’s been so successful in the past.

Who knows what is in Bezos’ addled mind. I do know one thing that isn’t there: a fundamental respect for nature, for billions of years of evolution, for the intricacy of the web of life that supports us here on planet Earth, a web of life we know virtually nothing about in comparison to what there is to know. He very obviously sees humans as separate from nature; anyone who imagines we can live in space must believe that to some degree. What Mr. Bezos fails to understand is that we are completely, utterly, inextricably part of nature; that we are human animals, and that our attempts to pretend otherwise will last only as long as the planetary ecosystem here on Earth, the ecosystem that continues to function at some diminished capacity, despite the damages we keep inflicting on the one and only planet we know of that supports life.

To fantasize that it is somehow better to try to recreate in space what we once had on Earth, than it is to contemplate limiting our demand just a bit so we can continue to live on this beautiful blue planet is human supremacy in the extreme. This won’t be a popular position, I know. Humans, especially Americans, love a new frontier to explore, and almost everyone I know gets excited about new technology and launching things into space.

But launching ourselves into space with the idea that we can somehow live without the planet to whom we are tethered with blood, guts, bacteria, cells, water, phytoplankton, oxygen, breath, fish, birds, trees, … every living thing on Earth… is the insane hallucination of someone who’s been “successful” as measured by little bits of green paper and numbers on a computer screen, but who has absolutely no idea that his fantasy, like the paper and the numbers, is a delusion.

by DGR News Service | May 18, 2019 | Toxification

True change can only be driven by revolutionary action and long-term radical organizing — not chemical collusion and compromise.

Last year, I volunteered to plant native species at the Spencer Creek-Coyote Creek wetlands southwest of Eugene, Oregon. This site, owned by the McKenzie River Trust (MRT), is an important riparian area at the confluence of two streams and is habitat for a wide range of plants, mammals, amphibians, birds, and other forms of life.

After arriving at the site, we learned during the orientation that herbicides had been applied in the area we were to be working to remove undesired plants. This did not sit well with me. I contacted McKenzie River Trust several months later and met with their conservation director to discuss chemical use. He explained that organizations like MRT are tasked with conserving large areas of land and don’t have the volunteer resources or staff to conduct non-chemical restoration. I suggested that MRT engage the community in dialogue around these issues in order to attempt an alternative.

The McKenzie River Trust disclosed that it has used pesticides including Glyphosate (aquatic formulation), triclooyr 3A, clethodim, aminipyralid, clopyralid, and flumioxazin over the past two years. MRT also uses chemicals at the Green Island site at the confluence of the Willamette and McKenzie rivers. The organization even has job descriptions that include specific reference to “Chemical control of invasive species… apply herbicides” in the activities list. It maintains a certified herbicide expert on staff. A representative of McKenzie River Trust told me that the organization has changed its volunteer policy to prevent the sort of herbicide exposure volunteers had earlier this year at the Spencer-Coyote Wetlands — but this doesn’t address the ecological impacts, or impacts on local residents.

I sympathize with relatively small organizations like McKenzie River Trust. They are operating in a bind whereby they are forced to either concede important habitat to aggressive invasive species, use poison, or attempt to mobilize the community to maintain land by hand. As they write in a fact sheet, “When working on large acreages, [herbicides] are the most efficient and cost-effective tool at our disposal.”

However, there is no excuse for manufacturing these substances, let alone deliberately releasing them into the environment.

We all assume that restoration and conversation groups have the best interests of the natural world at heart. But many of these groups regularly use chemical pesticides for land management, including chemicals that have been shown to cause cancer, birth defects, hormonal issues, and other health problems in humans and other species. This includes not just small local groups like The McKenzie River Trust and The Center for Applied Ecology, which are based in my region of western Oregon, but also large NGOs like The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

I have spoken with representatives of each of these organizations, and have confirmed that they actively use chemical herbicides.

The Nature Conservancy, for instance, uses organophosphate herbicides (the class that includes Glyphosate, the active ingredient of the popular weed-killer RoundUp) and a range of other chemicals on non-native species in the Willow Creek Preserve in southwest Eugene as well as thousands of other locations globally. The organization notes on its website that “herbicide use to control invasive species is an important land management strategy.”

The intentional release of toxic chemicals into the environment is an ironic policy for environmental groups, given that the modern environmental movement was founded on opposition to the use of pesticides (a category which includes herbicides). The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring is taken by many as the beginning of the modern environmental movement.

Pesticides are a persistent, serious threat to all forms of wildlife and to the integrity of ecology on this planet.

Amphibians, due to their permeable skin, are especially sensitive to the effects of pesticides. These creatures often spend their entire lives on the ground or underground, where pesticides may seep. Even at concentrations of 1/10th the recommended level, many pesticides cause harm or are fatal to amphibians.

Bees exposed to herbicides may be unable to fly, have trouble navigating, experience difficulty foraging and nest building. Exposure may lead to the death of bees and larva. One study showed that Glyphosate effects bees’ ability to think and retain memory “significantly.”

While herbicides are less toxic to birds and large mammals than other pesticides that are used to kill bugs and small animals like mice, several studies have shown interference with reproduction. Not all poisoning results in immediate death. Impacts might include reduced body mass, reproductive failure, smaller broods, weakening, or other effects.

Pesticides, in general, are implicated in dramatic collapses in bat populations, threaten invertebrates, and kill or harm fish. Additionally, they bioaccumulate in flesh — that is, their levels concentrate in the bodies of predators (including humans) and scavengers that eat poisoned rats or other animals that we deem as pests.

Pesticides are applied much more widely than most people realize. They are used along roads, in parks, in front of businesses, and along power lines. In forestry and agriculture, thousands of tons of chemicals are applied in Oregon every year. The Oregon Department of Transportation uses herbicides to spray roadsides across the state. A recent “off-label” use of a herbicide has caused the death of hundreds of Ponderosa pines along a 12-mile stretch near Sisters, OR. Across much of the United States, insecticides are sprayed widely in cities and water bodies to kill mosquitoes. And private organizations and individuals use pesticides widely as well. A southern California study that took place between 1993 and 2016 found a 500 percent increase in the number of people with glyphosate in their bloodstream during that period, and a 1208 percent increase in the average levels of glyphosate they had in their blood.

The effects of these chemicals on humans can be disastrous. Pesticides are linked to neurological, liver, lymphatic, endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, mental health, immune, and reproductive damage, as well as cancer risk. As far back as 1999, pesticide use was believed to kill 1 million humans per year. Yet these toxic chemicals continue to be used today.

***

According to permaculture expert Tao Orion, author of Beyond the War on Invasive Species, more volunteer work, or active harvesting, perhaps through collaboration with Indigenous groups, can eliminate the need for chemicals entirely. “If you’re considering that one or two people are going to manage 500 acres,” she said, “you’re setting yourself up for herbicide use. It’s a cop-out… Tending these areas may cause rare plants to increase. There is a lot of evidence now that this is indeed the case. But that goes against the [commonly accepted] American wilderness ideology.”

Orion says the use of toxic herbicide mixes is common as well. “I did an interview with the founder of the Center for Applied Ecology, and he said ‘we often just mix up RoundUp and 2, 4-D, that’s a surefire mix we’ve found,’” Orion said. As some may remember, 2, 4-D is one-half of the Agent Orange defoliant that was widely used in the ecocidal Vietnam War and has been linked to extremely serious human and non-human health issues.

In her book Beyond the War on Endangered Species, Orion details Agribusiness giant Monsanto and other pesticide industry corporations making a deliberate shift to market and sell chemicals to ecological restoration organizations. This is often done with the help of incomplete or poorly executed science claiming that pesticides are harmless. Jonathan Lundgren disagrees. This Presidential Early Career award winner for Science and Engineering was forced out of his USDA research scientist position after exposing damage caused by pesticides. Lundgren says that the science of pesticide safety “is for sale to the highest bidder.”

TNC and other restoration organizations are heavily influenced by research produced by land-grant colleges. Land-grant schools were set up in the late 1800’s to provide education on agriculture, engineering, and warfare. These schools maintain a fundamentally extractive, colonial mindset. “The pesticide manufacturers fund research and professorships at universities like Oregon State and other land-grant colleges,” Orion said. She also explained that these groups regularly receive grants from the federal government and sometimes from corporations directly. Land grant schools were a major factor in the industrialization of agriculture over the past 130 years.

One result of this corporatization of science is a revolving door between big organizations like The Nature Conversancy and industry. For instance, TNC’s managing director for Agriculture and Food Systems, Michael Doane, worked at Monsanto for 16 years prior to joining the organization.

The Nature Conservancy’s collaboration with big business goes well beyond Monsanto. Its “Business Council” is made up of a select group of 14 corporations including BNSF, Bank of America, Boeing, BP, Cargill, Caterpillar, Chevron, Dow Chemical, Duke Energy, Monsanto, and PepsiCo. Previous partners include mining giant Rio Tinto, ExxonMobil, and Phillips. The Nature Conservancy has received 10’s of millions in funding from these corporate partners, who are collectively responsible for a substantial portion of global ecocide and who have profited to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars.

I spoke with a local beekeeper who called TNC to inquire about pesticide use at Willow Creek. The TNC representative confirmed the use of multiple different herbicides. Though the beekeeper explained his fear for his bees, and described health concerns related to an elderly family member with Parkinson’s disease (a malady they believe is connected to past RoundUp exposure), the TNC representative refused to entertain any neighborly idea of notifying adjacent landowners about chemical use.

“He told me ‘this is private land, and we can do whatever the hell we want,’” the beekeeper told me.

This response is not a surprise: The Nature Conservancy’s entire approach is based on privatization. At the Willow Creek site, and most Nature Conservancy properties, land is not accessible by the public. Fences block access and signs warn against trespassing.

This privatization model mirrors the Royal “hunting preserve” and “King’s forest” commonly found in historic monarchies. It’s an approach that is regularly critiqued by other conservation groups, who see responsible interaction with the land as essential for creating a land ethic. Groups like Survival International regularly report on the negative impacts this approach has on Indigenous people throughout the world, especially in Africa, where TNC and other large groups such as the World Wildlife Fund regularly purchase and privatize lands once held in common. According to Survival International, this approach is often counterproductive. The group notes that Indigenous people’s presence on ancestral lands is actually the number one predictor of biological diversity and ecosystem health.

***

Given the decades-long effort by chemical companies to market their products as safe and the clear evidence this is not the case, it’s important to grow a mass movement that questions the use of chemicals.

Locals, including Orion, members of the Stop Aerial Spraying Coalition, and the beekeeper I spoke with want TNC and other conservation groups to change their approach to eliminate chemical use, and appreciate TNC’s experimentation with prescribed fire, which may reduce or eliminate the need for chemicals. Prescribed burning is a traditional practice among many Indigenous communities. Other chemical-free practices that can reduce undesirable species and increase biodiversity include targeted grazing, reintroduction of extirpated species, hand removal, and beneficial harvesting.

These approaches aren’t as fast as poison, but they can be sustainable.

The Nature Conservancy does some good work. So do many nonprofits, especially the smaller, grassroots organizations. However, cases like this illustrate why lasting environmental victories aren’t likely to emerge from large environmental NGOs or from corporate collaboration. TNC’s refusal to engage in political struggle over pressing issues such as drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, let alone global climate change and major threats to the planet, show the limitations of these groups. Their defensive work to protect a given species or area is important, but this “whack-a-mole” method cannot proactively address the global issues we face.

The perils of collaboration with corporations can be seen throughout the environmental movement, not just in this case. Corporations and wealthy individuals have long recognized the existential threat posed by a radical environmental movement. When you question the destruction of one mountain or meadow or forest, it isn’t long until you question capitalism and industrialism too. Thus, they direct their funding to mainstream environmental groups, which present technological and policy change as the solution. I’ve called this a “pressure relief valve” for popular discontent. Others have labeled it one half of the “twin tactics of control: reform and repression.”

We must be wary of foundation funded and large NGOs. Nonprofits that are reliant on outside funding always must speak to the lowest common denominator: the funders. They must avoid offending these individuals and groups, and must supply deliverables to meet grant requirements. This focus on short term bullet-points relegates broader visioning to the fringes, and results in institutions and organizations with a systemic inability to think big or lead revolutionary change.

Despite the massive nonprofit industrial complex, every indicator of ecological health is heading in the wrong direction. I have always advocated both reform and revolution. But in today’s world, there is no shortage of tepid, chemical-soaked reform. To turn this around, we will need fundamental changes in the economic system and the structure of society, changes that can only be driven by revolutionary action and long-term radical organizing — not chemical collusion and compromise.

by DGR News Service | May 14, 2019 | Climate Change, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

Editor’s Note: This 2012 research article from University of Utah physicist and researcher Timothy Garrett concludes that “If civilization does not collapse quickly this century, then CO2 levels will likely end up exceeding 1000 ppmv.” We see this as further evidence that the Deep Green Resistance strategy of purposefully accelerating a managed collapse will provide the best chance for continuation of life on this planet.

No way out? The double-bind in seeking global prosperity alongside mitigated climate change.

Abstract. In a prior study (Garrett, 2011), I introduced a simple economic growth model designed to be consistent with general thermodynamic laws. Unlike traditional economic models, civilization is viewed only as a well-mixed global whole with no distinction made between individual nations, economic sectors, labor, or capital investments. At the model core is a hypothesis that the global economy’s current rate of primary energy consumption is tied through a constant to a very general representation of its historically accumulated wealth. Observations support this hypothesis, and indicate that the constant’s value is λ = 9.7 ± 0.3 milliwatts per 1990 US dollar. It is this link that allows for treatment of seemingly complex economic systems as simple physical systems. Here, this growth model is coupled to a linear formulation for the evolution of globally well-mixed atmospheric CO2 concentrations. While very simple, the coupled model provides faithful multi-decadal hindcasts of trajectories in gross world product (GWP) and CO2. Extending the model to the future, the model suggests that the well-known IPCC SRES scenarios substantially underestimate how much CO2 levels will rise for a given level of future economic prosperity. For one, global CO2 emission rates cannot be decoupled from wealth through efficiency gains. For another, like a long-term natural disaster, future greenhouse warming can be expected to act as an inflationary drag on the real growth of global wealth. For atmospheric CO2 concentrations to remain below a “dangerous” level of 450 ppmv (Hansen et al., 2007), model forecasts suggest that there will have to be some combination of an unrealistically rapid rate of energy decarbonization and nearly immediate reductions in global civilization wealth. Effectively, it appears that civilization may be in a double-bind. If civilization does not collapse quickly this century, then CO2 levels will likely end up exceeding 1000 ppmv [emphasis added]; but, if CO2 levels rise by this much, then the risk is that civilization will gradually tend towards collapse.

Originally published as Garrett, T. J.: No way out? The double-bind in seeking global prosperity alongside mitigated climate change, Earth Syst. Dynam., 3, 1-17, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-3-1-2012, 2012.

https://www.earth-syst-dynam.net/3/1/2012/esd-3-1-2012.html

by DGR News Service | May 13, 2019 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, The Solution: Resistance

via The Pinyon-Juniper Alliance

The Pinyon-Juniper Alliance was formed several years ago to protect Pinyon-Pine and Juniper forests from destruction under the BLM’s and Forest Service’s misguided “restoration” plan. Since that time, we have attended public meetings, organized petitions, talked with politicians and locals, coordinated with other groups, written articles and given presentations, and commented on public policy.

Things now are worse than ever. The latest project we’ve seen aims to remove PJ forest from more than 130,000 acres of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. That’s more than 200 square miles in one project.

Everywhere we go, we see juniper trees cut. Most recently, just this past weekend in Eastern Oregon, an entire mountainside was littered with chainsawed juniper trees. Earlier today, one of our organizers spoke with an elder from the Ely-Shoshone Tribe. She told us about two conversations she had with agency employees who referred to old pinyon-pines as “useless” trees that needed to be removed. She responded by saying “I wouldn’t be here without those trees,” and told them about the importance of pine nuts to Great Basin indigenous people.

And still the mass destruction continues.

However, looming behind these atrocities is an even bigger threat. Due to global warming, drought is becoming almost continuous throughout most of the intermountain West. The possibility of a permanent dust bowl in the region appears increasingly likely as governments worldwide have done nothing to avert climate catastrophe.

Pinyon-Pine and Juniper are falling to the chainsaw. However, they have been able to survive the saws of men for two hundred years. It is unlikely they will be able to survive two hundred years of unabated global warming.

The biggest threat to Pinyon-Juniper forests isn’t chainsaws or the BLM. The biggest threat is the continuation of industrial civilization, which is leading to climate meltdown. Stopping industrial civilization would limit this threat, and would also stop the flow of fossil fuels that powers the ATVs and Masticators and Chainsaws currently decimating Pinyon-Juniper forests.

Derrick Jensen has said that often people who start out trying to protect a certain forest or meadow end up questioning the foundations of western civilization. We have undergone this process ourselves.

Given our limited time, energy, and resources, our responsibility is to focus on what we see as the larger threats. Therefore, the founders of the Pinyon-Juniper Alliance have turned to focus on revolutionary work aimed at overturning the broader “culture of empire” and the global industrial economy that powers it. We are not leaving the PJ struggle behind. If you are engaged in this fight, please reach out to us. We need to network, share information, and work together to have a chance of success. We are shifting the form of our struggle. If this struggle is won, it will result in a world that Pinyon-Juniper forest can inhabit and spread across freely once again. And if it’s lost, our work at the local level is unlikely to matter. There are few revolutionaries in the world today, and we have a responsibility to do what is necessary.

by DGR News Service | May 9, 2019 | Climate Change

By Elisabeth Robson / Art for Culture Change

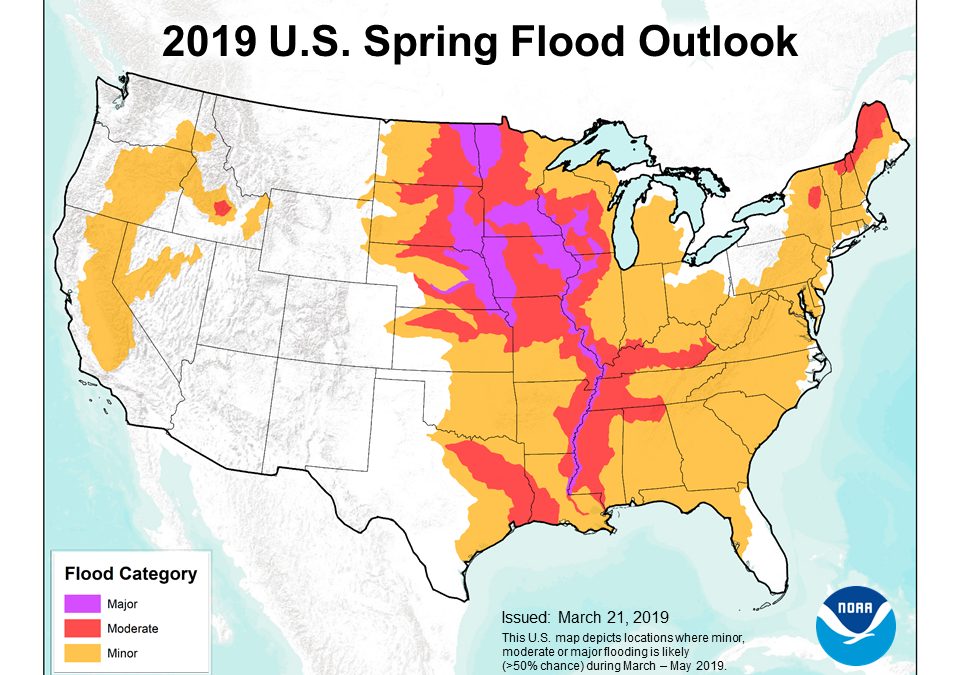

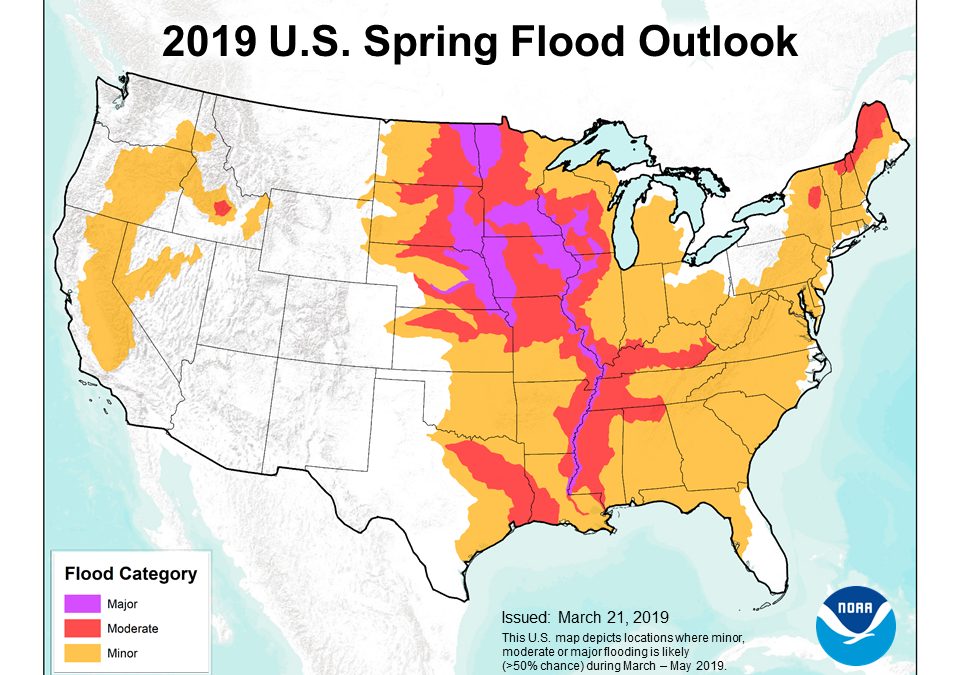

The catastrophic flooding across the midwest isn’t getting much coverage on the coasts, but it is a multibillion $ disaster for multiple states and indigenous nations.

Over a million wells may be contaminated.

Farmers will lose their farms.

The top soil is washing away.

The cattle losses have yet to be tallied but are likely to be huge.

8 EPA superfund sites have been inundated and no one knows what toxic nastiness is washing into the ground and water from those sites.

And of course all the little ways toxins make their way into the water from inundated septic systems, landfill sites, dumps, oil on the ground, and flooded energy infrastructure.

The flood waters are washing not just soil, but decades of accumulated synthetic fertilizers and many other toxins, into the Mississippi river, all of which will eventually flow into the Gulf of Mexico. The yearly “dead zone” in the Gulf is already notorious–agriculture runoff creates algae growth, which in turn creates hypoxic zones, and all marine life in those zones dies from lack of oxygen.

This year’s “dead zone” could be the largest ever.

This winter, we can expect high food prices throughout the country. The flooded region produces wheat, corn, and soy, used to feed millions of feed lot cattle, and produce our industrial food products (bread, cereals, etc.)

The fields have not only lost topsoil; many are now covered with sand and other debris. It will be years, decades, or more before these fields return to full production–of course, their “full production” now is based on industrial agriculture, so it’s highly unnatural, but it does feed much of this country, so it’s something to keep in mind.

And of course along with those losses, many farmers will now be out of work.

Once upon a time, long ago, before the rivers in this country were dammed and levied and corralled into submission, flooding like this used to bring nutrients to the prairies and regenerate the land. Once upon a time, floods like this were a temporary hardship for a long term gain in productivity for all the wild things of the vast prairies of the continent.

In our modern times, flooding like this is a disaster, one that will have decades of repercussions of poisoned soil and water, poverty, and misery.

Image by NOAA of 2019 Spring Flood Outlook for the USA.

by DGR News Service | May 8, 2019 | Human Supremacy

By Beth Robson / Art for Culture Change

I love the cover of the New York Times Magazine, by Pablo Delcan, for this week’s big story, “The Problem with Putting a Price on the End of the World.”

The article discusses the challenge with pricing carbon emissions properly so that we use less fossil fuels: because fossil fuels are so fundamental to every aspect of how we live in this modern culture, to price emissions higher means bringing a world of hurt to people who just want to be able to afford a home, or to commute to work, or put the next meal on the table.

The basic problem with pricing carbon as a solution to climate change is not, as the article states (and most people like to claim), that it is a “market failure”.

The problem is that pricing carbon doesn’t address the underlying issue: that our modern culture is inherently unsustainable, no matter how much we pay for the energy to run it.

The article argues that pricing carbon leads to a sluggish economy, which is bad.

No, what’s bad is the economy, period. Our modern economy is based on continual growth. We can’t “fix” the economy; we have to abolish it. Eliminate it. And to do that we need a vision of what is to replace it (and no, not “clean energy”!!) — because without a vision, people just get angry when they can no longer afford the necessities of life.

Unfortunately but unsurprisingly, this article pins hopes for the future on “clean” energy (something that doesn’t actually exist), and a growth economy based on renewables, within the framing of shifting away from fossil fuels not because carbon is expensive, but because renewables are a better, cheaper option, cause less pollution and less carbon, and will create jobs (i.e., basically the same argument as The Green New Deal). This approach simply changes the energy source that runs our unsustainable economy; it doesn’t change the underlying problem: the economy and the way we live our lives because of that economy.

The real problem of putting a price on the world (whether that’s carbon, or “ecosystem services”) is that it turns everything in the world into a commodity, into something that can be calculated into our growth economy. And it is our economy: our consumer-based, capitalist, infinitely growing economy that is killing the planet. It doesn’t matter how you power that economy—with so-called “clean” energy or fossil fuels.

As long as we have growth—more people, buying more stuff, building more roads, houses, cars—we are in trouble.

As long as we think of nature as property—as something that can be bought and sold on the market, rather than as something we are, that we must prioritize above all else, because without nature, we do not exist—we will never succeed in solving the existential crisis in which we find ourselves today.

Pablo Delcan’s cover for the magazine is a good reminder that we cannot sell planet Earth and expect to survive. We have already sold most of the planet as “property”, and once we think of nature as property, then we use it and destroy it for profit.

Our only way forward is to see nature as intrinsically valuable for its own sake, and to remember that we are not consumers, that money is just a figment of our imagination, and that the real world, the physical world, filled with intact and flourishing ecosystems, is the only thing that matters.

Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash