by DGR News Service | Sep 15, 2020 | Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

This is the fourth part in the series. In the previous essays, we have explored the need for a collapse, the relationship between a Dyson sphere and overcomsumption, and our blind pursuit for ‘progress.’ In this piece, Elisabeth describes how the Dyson sphere is an extension of the drive for so-called “green energy.”

By Elisabeth Robson

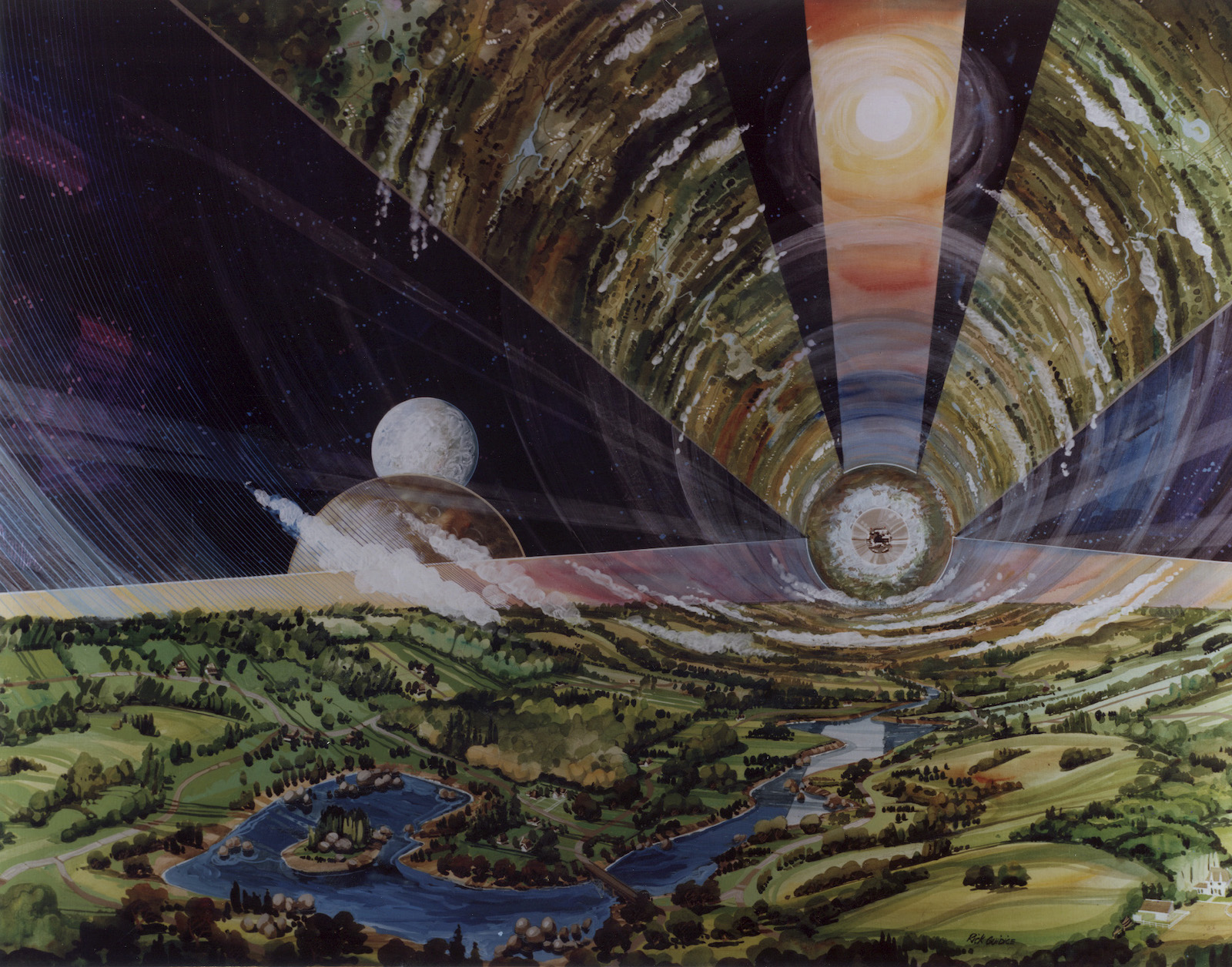

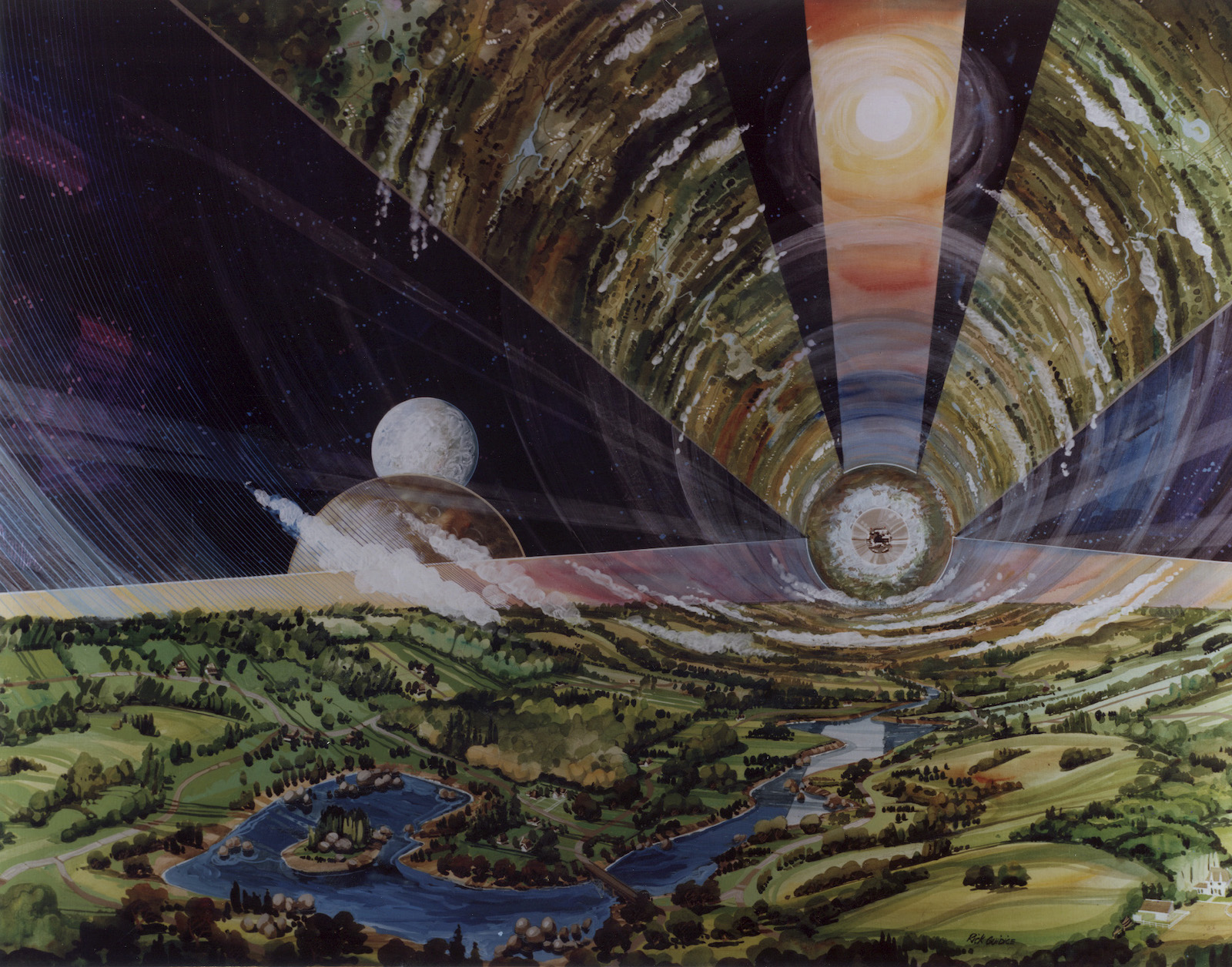

Techno-utopians imagine the human population on Earth can be saved from collapse using energy collected with a Dyson Sphere–a vast solar array surrounding the sun and funneling energy back to Earth–to build and power space ships. In these ships, we’ll leave the polluted and devastated Earth behind to venture into space and populate the solar system. Such a fantasy is outlined in “Deforestation and world population sustainability: a quantitative analysis” and is a story worthy of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. It says, in so many words: we’ve trashed this planet, so let’s go find another one.

In their report, Mauro Bologna and Gerardo Aquino present a model that shows, with continued population growth and deforestation at current rates, we have a less than 10% chance of avoiding catastrophic collapse of civilization within the next few decades. Some argue that a deliberate and well-managed collapse would be better than the alternatives. Bologna and Aquino present two potential solutions to this situation. One is to develop the Dyson Sphere technology we can use to escape the bonds of our home planet and populate the solar system. The other is to change the way we (that is, those of us living in industrial and consumer society) live on this planet into a ‘cultural society’, one not driven primarily by economy and consumption, in order to sustain the population here on Earth.

The authors acknowledge that the idea of using a Dyson Sphere to provide all the energy we need to populate the solar system is unrealistic, especially in the timeframe to avoid collapse that’s demonstrated by their own work. They suggest that any attempt to develop such technology, whether to “live in extraterrestrial space or develop any other way to sustain population of the planet” will take too long given current rates of deforestation. As Salonika describes in an earlier article in this series, “A Dyson Sphere will not stop collapse“, any attempt to create such a fantastical technology would only increase the exploitation of the environment.

Technology makes things worse

The authors rightly acknowledge this point, noting that “higher technological level leads to growing population and higher forest consumption.” Attempts to develop the more advanced technology humanity believes is required to prevent collapse will simply speed up the timeframe to collapse. However, the authors then contradict themselves and veer back into fantasy land when they suggest that higher technological levels can enable “more effective use of resources” and can therefore lead, in principle, to “technological solutions to prevent the ecological collapse of the planet.”

Techno-utopians often fail to notice that we have the population we do on Earth precisely because we have used technology to increase the effectiveness (and efficiency) of fossil fuels and other resources* (forests, metals, minerals, water, land, fish, etc.). Each time we increase ‘effective use’ of these resources by developing new technology, the result is an increase in resource use that drives an increase in population and development, along with the pollution and ecocide that accompanies that development. The agricultural ‘green revolution’ is a perfect example of this: advances in technology enabled new high-yield cereals as well as new fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, irrigation, and mechanization, all of which prevented widespread famine, but also contributed to an ongoing explosion in population, development, chemical use, deforestation, land degradation and salinization, water pollution, top soil loss, and biodiversity loss around the world.

As economist William Stanley Jevons predicted in 1865, increasing energy efficiency with advances in technology leads to more energy use. Extrapolating from his well-proved prediction, it should be obvious that new technology will not prevent ecological collapse; in fact, such technology is much more likely to exacerbate it.

This mistaken belief that new technology can save us from collapse pervades the policies and projects of governments around the world.

Projects like the Green New Deal, the Democrat Party’s recently published climate plan, and the UN’s sustainable development goals and IPCC recommendations. All these projects advocate for global development and adoption of ‘clean technology’ and ‘clean industry’ (I’m not sure what those terms mean, myself); ’emissions-free’ energy technologies like solar, wind, nuclear and hydropower; and climate change mitigation technologies like carbon capture and storage, smart grids, artificial intelligence, and geo-engineering. They tout massive growth in renewable energy production from wind and solar, and boast about how efficient and inexpensive these technologies have become, implying that all will be well if we just keep innovating new technologies on our well worn path of progress.

Miles and miles of solar panels, twinkling like artificial lakes in the middle of deserts and fields; row upon row of wind turbines, huge white metal beasts turning wind into electricity, and mountain tops and prairies into wasteland; massive concrete dams choking rivers to death to store what we used to call water, now mere embodied energy stored to create electrons when we need them–the techno-utopians claim these so-called clean’ technologies can replace the black gold of our present fantasies–fossil fuels–and save us from ourselves with futuristic electric fantasies instead.

All these visions are equally implausible in their capacity to save us from collapse.

And while solar panels, wind turbines, and dams are real, in the sense that they exist–unlike the Dyson Sphere–all equally embody the utter failure of imagination we humans seem unable to transcend. Some will scoff at my dismissal of these electric visions, and say that imagining and inventing new technologies is the pinnacle of human achievement. With such framing, the techno-utopians have convinced themselves that creating new technologies to solve the problems of old technologies is progress. This time it will be different, they promise.

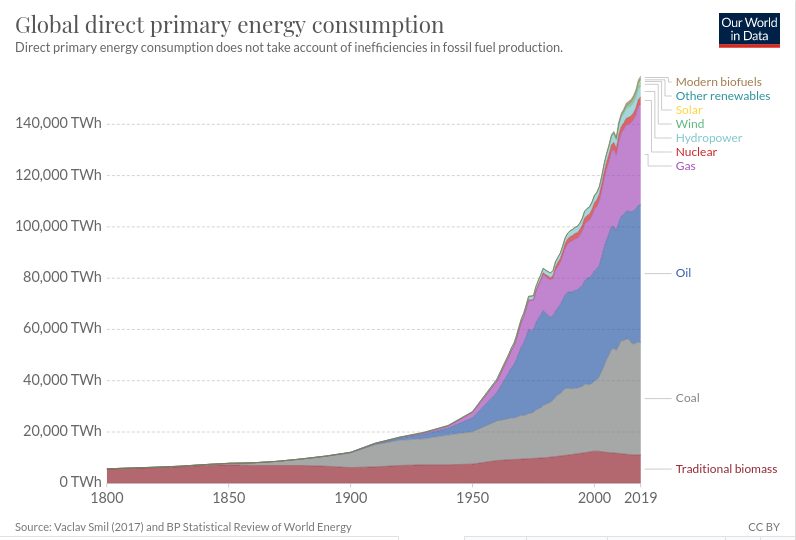

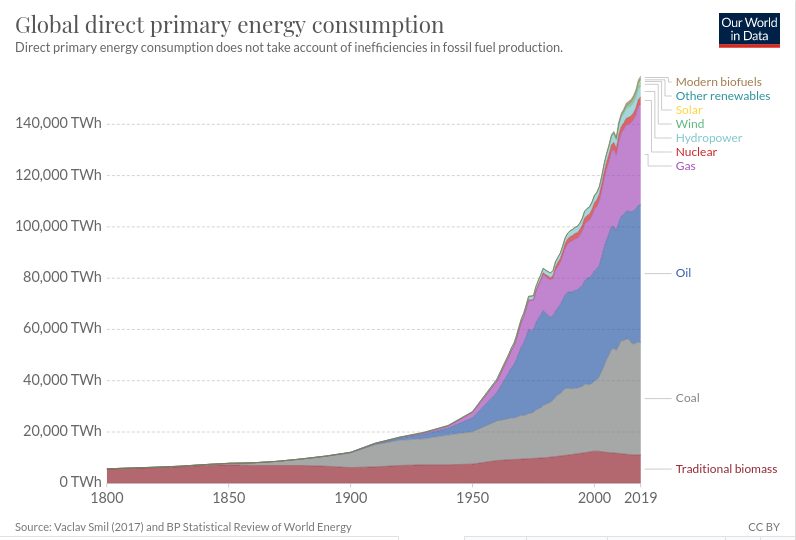

And yet if you look at the graph of global primary energy consumption:

it should be obvious to any sensible person that new, so-called ‘clean’ energy-producing technologies are only adding to that upward curve of the graph, and are not replacing fossil fuels in any meaningful way. Previous research has shown that “total national [US] energy use from non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-quarter of a unit of fossil-fuel energy use and, focussing specifically on electricity, each unit of electricity generated by non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-tenth of a unit of fossil-fuel-generated electricity.”

In part, this is due to the fossil fuel energy required to mine, refine, manufacture, install, maintain, and properly dispose of materials used to make renewable and climate mitigation technologies. Mining is the most destructive human activity on the planet, and a recent University of Queensland study found that mining the minerals and metals required for renewable energy technology could threaten biodiversity more than climate change. However, those who use the word “clean” to describe these technologies conveniently forget to mention these problems.

Wind turbines and solar arrays are getting so cheap; they are being built to reduce the cost of the energy required to frack gas: thus, the black snake eats its own tail. “Solar panels are starting to die, leaving behind toxic trash”, a recent headline blares, above an article that makes no suggestion that perhaps it’s time to cut back a little on energy use. Because they cannot be recycled, most wind turbine blades end up in landfill, where they will contaminate the soil and ground water long after humanity is a distant memory. Forests in the southeast and northwest of the United States are being decimated for high-tech biomass production because of a loophole in EU carbon budget policy that counts biomass as renewable and emissions free. Dams have killed the rivers in the US Pacific Northwest, and salmon populations are collapsing as a result. I could go on.

The lies we tell ourselves

Just like the Dyson Sphere, these and other technologies we fantasize will save our way of life from collapse are delusions on a grand scale. The governor of my own US state of Washington boasts about how this state’s abundant “clean” hydropower energy will help us create a “clean” economy, while at the same time he fusses about the imminent extinction of the salmon-dependent Southern Resident Orca whales. I wonder: does he not see the contradiction, or is he willfully blind to his own hypocrisy?

The face of the Earth is a record of human sins (1), a ledger written in concrete and steel; the Earth twisted into skyscrapers and bridges, plows and combines, solar panels and wind turbines, mines and missing mountains; with ink made from chemical waste and nuclear contamination, plastic and the dead bodies of trees. The skies, too, tell our most recent story. Once source of inspiration and mythic tales, in the skies we now see airplanes and contrails, space junk and satellites we might once have mistaken for shooting stars, but can no longer because there are so many; with vision obscured by layers of too much PM2.5 and CO2 and NOx and SO2 and ozone and benzene. In the dreams of techno-utopians, we see space ships leaving a rotting, smoking Earth behind.

One of many tales of our Earthly sins is deforestation.

As the saying goes, forests precede us, and deserts follow; Mauro Bologna and Gerardo Aquino chose a good metric for understanding and measuring our time left on Earth. Without forests, there is no rain and the middles of continents become deserts. It is said the Middle East, a vast area we now think of as primarily desert, used to be covered in forests so thick and vast the sunlight never touched the ground (2). Without forests, there is no home for species we’ve long since forgotten we are connected to in that web of life we imagine ourselves separate from, looking down from above as techno-gods on that dirty, inconvenient thing we call nature, protected by our bubble of plastic and steel. Without forests, there is no life.

One part of one sentence in the middle of the report gives away man’s original sin: it is when the authors write, “our model does not specify the technological mechanism by which the successful trajectories are able to find an alternative to forests and avoid collapse“. Do they fail to understand that there is no alternative to forests? That no amount of technology, no matter how advanced–no Dyson Sphere; no deserts full of solar panels; no denuded mountain ridges lined with wind turbines; no dam, no matter how wide or high; no amount of chemicals injected into the atmosphere to reflect the sun–will ever serve as an “alternative to forests”? Or are they willfully blind to this fundamental fact of this once fecund and now dying planet that is our only home?

A different vision

I’d like to give the authors the benefit of the doubt, as they end their report with a tantalizing reference to another way of being for humans, when they write, “we suggest that only civilisations capable of a switch from an economical society to a sort of ‘cultural’ society in a timely manner, may survive.” They do not expand on this idea at all. As physicists, perhaps the authors didn’t feel like they had the freedom to do so in a prestigious journal like Nature, where, one presumes, scientists are expected to stay firmly in their own lanes.

Having clearly made their case that civilized humanity can expect a change of life circumstance fairly soon, perhaps they felt it best to leave to others the responsibility and imagination for this vision. Such a vision will require not just remembering who we are: bi-pedal apes utterly dependent on the natural world for our existence. It will require a deep listening to the forests, the rivers, the sky, the rain, the salmon, the frogs, the birds… in short, to all the pulsing, breathing, flowing, speaking communities we live among but ignore in our rush to cover the world with our innovations in new technology.

Paul Kingsnorth wrote: “Spiritual teachers throughout history have all taught that the divine is reached through simplicity, humility, and self-denial: through the negation of the ego and respect for life. To put it mildly, these are not qualities that our culture encourages. But that doesn’t mean they are antiquated; only that we have forgotten why they matter.”

New technologies, real or imagined, and the profits they bring is what our culture reveres.

Building dams, solar arrays, and wind turbines; experimenting with machines to capture CO2 from the air and inject SO2 into the troposphere to reflect the sun; imagining Dyson Spheres powering spaceships carrying humanity to new frontiers–these efforts are all exciting; they appeal to our sense of adventure, and align perfectly with a culture of progress that demands always more. But such pursuits destroy our souls along with the living Earth just a little bit more with each new technology we invent.

This constant push for progress through the development of new technologies and new ways of generating energy is the opposite of simplicity, humility, and self-denial. So, the question becomes: how can we remember the pleasures of a simple, humble, spare life? How can we rewrite our stories to create a cultural society based on those values instead? We have little time left to find an answer.

* I dislike the word resources to refer to the natural world; I’m using it here because it’s a handy word, and it’s how most techno-utopians refer to mountains, rivers, rocks, forests, and life in general.

(1) Susan Griffin, Woman and Nature

(2) Derrick Jensen, Deep Green Resistance

In the final part of this series, we will discuss what the cultural shift (as described by the authors) would look like.

Featured image: e-waste in Bangalore, India at a “recycling” facility. Photo by Victor Grigas, CC BY SA 3.0.

by DGR News Service | Sep 14, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Human Supremacy, NEWS, The Problem: Civilization

Our use of plastics has threatened oceans and the marine biodiversity. But our efforts for plastic cleanup, may well threaten a less-known marine ecosystem. This article was originally published in DW.com

Little is known about the neuston, but marine biologists fear this community of organisms living on the ocean surface could be decimated as nets sweep up plastic pollution.

In May 2017, shells started washing up along the Ligurian coast in Italy. They were small and purple and belonged to a snail called Janthina pallida that is rarely seen on land. But the snails kept coming — so many that entire stretches of the beach turned pastel.

An unusual wind pattern had beached the animals. And for the people who walked the shore, this offered a rare encounter with a wondrous ecosystem that most of us have never heard about: The neuston.

The neuston, from the Greek word for swimming, refers to a group of animals, plants and microorganisms that spend all or large parts of their life floating in the top few centimeters of the ocean.

It’s a mysterious world that even experts still know little about. But recently, it has been the source of tensions between a project trying to clean up the sea by skimming plastic trash off its surface, and marine biologists who say this could destroy the neuston.

A world between worlds

The neuston comprises a multitude of weird and wonderful creatures. Many, like the Portuguese man-of-war, which paralyzes its prey with venomous tentacles up to 30 meters long, are colored an electric shade of blue, possibly to protect themselves against the sun’s UV rays, or as camouflages against predators.

There are also by-the-wind sailors, flattish creatures that raise chitin shields from the water like sails; slugs known as sea dragons that cling to the water’s surface from below with webbed appendages; barnacles that build bubble rafts as big as dinner plates; and the world’s only marine insects, a relation of the pond skater.

Between the Worlds

They live “between the worlds” of the sea and sky, as Federico Betti, a marine biologist at the University of Genoa, puts it. From below, predators lurk. From above, the sun burns. Winds and waves toss them about. Depending on the weather, their environment may be warm or cool, salty or less so.

But now, they face another — manmade — threat from nets designed to catch trash. A project called The Ocean Cleanup, run by Dutch inventor Boyan Slat, has raised millions of dollars in donations and sponsorship to deploy long barriers with nets that will drift across the ocean in open loops to sweep up floating garbage.

Plastic and marine life are moved by currents

“Plastic could outweigh fish in the oceans by 2050. To us, that future is unacceptable,” The Ocean Cleanup declares on its website. But Rebecca Helm, a marine biologist at the University of North Carolina Asheville, and one of the few scientists to study this ecosystem, fears that The Ocean Cleanup’s proposal to remove 90% of the plastic trash from the water could also virtually wipe out the neuston.

One focus of Helm’s studies is where these organisms congregate. “There are places that are very, very concentrated and areas of little concentration, and we’re trying to figure out why,” says Helm. One factor is that the neuston floats with ocean currents, and Helm worries that it might collect in the exact same spots as marine plastic pollution. “Our initial data show that regions with high concentrations of plastic are also regions with high concentrations of life.”

The Ocean Cleanup says Helm’s concerns are based on “misguided assumptions.”

“It’s true that neustonic organisms will be trapped in the barriers,” says Gerhard Herndl, professor of Aquatic Biology at the University of Vienna and one of project’s scientific advisors. “But these organisms have dangerous lives. They’re adapted to high losses because they get washed ashore in storms and they have high reproductive rates. If they didn’t, they’d already be extinct.”

Helm says they just don’t know how quickly these creatures reproduce, and in any case recovering from passing storm is very different from surviving The Ocean Clean Up’s systems which could be in place for years.

Still a lot to learn about the neuston

In December, The Ocean Cleanup and Helm participated in a symposium on the topic hosted by the Institute for Risk and Uncertainty at the University of Liverpool in the UK. Since then, direct communication between them has stopped, says Helm. “They’re not interested in talking to me anymore.”

Both sides agree that much is still unknown about the neuston. But one thing that has been established is that most of the oceans’ fish spend part of their lifecycle in the neuston. “More than 90% of marine fish species produce floating eggs that persist on the surface until hatching,” Betti says.

The Ocean Cleanup has undertaken one of the few studies into this ecosystem, collecting data on the neuston on the relative abundance of neuston and floating plastic debris in the eastern North Pacific Ocean during a 2019 expedition to the Pacific Garbage Patch, an area where plastic pollution has accumulated on a vast scale. But it is not yet sharing what it has found. The information was being prepared for publication in an as of yet unspecified journal, probably some time next year, an Ocean Cleanup spokesperson said.

Is the solution inshore?

Helm believes the best way to tackle the marine plastic problem would be to position the barriers closer to land — across river mouths and bays — to catch garbage before it reaches the sea.

“Stopping the flow of plastic into the ocean is the most cost-effective — and literally effective — way to ensure that it’s not entering our environment,” she says. As for the plastic already floating in open waters, she does not believe it is worth sacrificing parts of neuston and wants to see more research first.

The Ocean Cleanup has made barriers across rivers a part of its mission. But it is also going ahead with its original vision of pulling trash from the open water. In late 2018, the project deployed a 600-meter, u-shaped prototype net into the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

The system ran into difficulties, failing to retain plastic as hoped, and needing to be brought shore for repairs and a design upgrade, after which Ocean Cleanup says it gathered haul of plastic that it will recycle and resell to help fund future operations. Over the next two years, the project hopes to deploy up to 60 such barriers to collect drifting flotsam. Helm isn’t the only one concerned about these plans.

“We should think twice about every action we take in the sea,” Betti says. “In nature, nothing is as easy as we think, and often, we’ve done a lot of damage while trying to do a good thing.”

This article was first published on www.dw.com. You can find the full and original article here:

https://www.dw.com/en/environment-conservation-plastic-oceans/a-54436603

Featured Image: A Portuguese man-of-war by Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons 2.0

by DGR News Service | Sep 13, 2020 | Colonialism & Conquest, The Problem: Civilization

Another Massive Clearcutting Proposal Threatens Southeast Alaska’s Economy, Wildlife, Carbon Stores

JUNEAU, ALASKA (Tlingit: A’aakw Kwáan lands) — The Trump administration announced plans today for yet another massive timber sale that would destroy more than 5,100 acres of critical old-growth habitat in the Tongass National Forest in Southeast Alaska.

“Shame on the Trump administration’s Forest Service for having the gall to continue to burden and overwhelm Southeast Alaskans with yet another needless and money-losing timber sale when we are in the midst of a pandemic and a controversial Alaska Roadless Rulemaking process,” said Dan Cannon, Tongass Forest Program Manager for Southeast Alaska Conservation Council. “As Alaskans await Secretary Perdue’s decision on the Roadless Rule, they will yet again have to advocate for the protection of critical old-growth habitat in their backyards. We don’t know how many times we need to say it: Timber only contributes 1% to Southeast Alaska’s economy, while the fishing and tourism industries contribute 26%. Stop making Southeast Alaskans’ lives more difficult by threatening our true economic drivers.”

The U.S. Forest Service’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the South Revilla Integrated Resource Project timber sale proposes chainsawing 5,115 acres of old-growth forest near Ketchikan. It also would allow bulldozing or rebuilding more than 80 miles of damaging logging roads costing U.S. taxpayers more than $11 million. The public will have until Oct. 19 to provide comments.

“This assault on America’s largest rainforest will destroy important habitat for salmon, bears and wolves, and worsen the climate crisis,” said Randi Spivak, Public Lands Director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “Clearcutting the Tongass and wiping out enormous carbon stores is like cutting off part of the planet’s oxygen supply. It’s mind-boggling that the Trump administration wants to decimate this spectacular old-growth forest and erase one of the solutions to averting catastrophic climate change.”

This project and the proposed elimination of the Roadless Area Conservation Rule on the Tongass are part of the Trump administration’s relentless efforts to clearcut large swaths of remaining old-growth across the national forest, consistent with its policy of increasing logging nationwide.

“As forests across the America’s burn, the last thing we need to do is destroy old-growth forests in the Tongass Rainforest — one of the United States’ best defenses against furthering the climate crisis,” said Osprey Oreille Lake, Executive Director for the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN). “Existing within the territories of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsmishian peoples, the Tongass is a vital ecosystem necessary to the traditional life-ways of local Indigenous communities. Destroying critical old-growth in the Tongass, not only devastates wildlife habitat and harms the climate, but disregards the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples and further perpetuates modern genocidal policies. We must stand together for our forests, communities and the climate.”

The roughly 17 million-acre Tongass is the largest national forest in the United States. Since time immemorial it has been the traditional homelands of the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian peoples. Alaska Native people rely on the area for culture, traditional hunting, fishing and livelihoods. People from around the world visit the Tongass for world-class recreation, sport and commercial fishing.

“It was just over two months ago that a federal judge threw out the largest logging project we’ve seen in decades because the Forest Service failed to provide communities with basic information like where it intended to log,” said Olivia Glasscock, an attorney at Earthjustice. “Nevertheless the agency is back again with another massive timber sale targeting irreplaceable old-growth trees in the same cherished national forest. Urgent action is needed to address the climate crisis, and that includes efforts to preserve the magnificent trees that absorb carbon. Unfortunately, this destructive logging plan will only make the problem worse.”

The Tongass is the largest intact temperate rainforest left on Earth and provides vital habitat for eagles, bears, wolves, salmon and countless other species. It is a globally recognized carbon sink and helps to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change, storing approximately 8% of the total carbon stored in all U.S. national forests.

“Alaska Rainforest Defenders asked, plain and simple in our September 2018 scoping comments on the South Revilla project, that the Forest Service drop the timber part of the project,” said spokesman Larry Edwards. “As with our recently successful lawsuit against the timber component of the POWLLA project, environmentalists have no complaints over the non-timber components of this project.” Edwards added, “In the DEIS, all of the alternatives for the project are estimated to have a timber sale value appraised at a loss to taxpayers, which means that legally a timber sale could not be offered. Continuing to a final EIS would be gambling with millions of dollars of Forest Service planning effort at taxpayer expense.”

Logging the Tongass has been tremendously costly for taxpayers. A new report estimates that timber sales from the forest have cost taxpayers $1.7 billion over four decades.

“Despite a commitment to move away from unsustainable old-growth timber sales, the U.S. Forest Service continues to offer these sales in the Tongass National Forest. More clearcutting will damage the real drivers of southeast Alaska’s economy: fish, wildlife and tourism. Defenders won’t stand by and watch as the Forest Service despoils irreplaceable wildlife habitat and threatens sustainable jobs and livelihoods in Southeast Alaska,” said Nicole Whittington-Evans, Alaska Program Director for Defenders of Wildlife.

The public can comment on the project here.

###

The Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International

www.wecaninternational.org – @WECAN_INTL

The Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International is a 501(c)3 and solutions-based organization established to engage women worldwide in policy advocacy, on-the-ground projects, direct action, trainings, and movement building for global climate justice.

Featured image: Alan Wu via Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

by DGR News Service | Sep 12, 2020 | Gender, Pornography

In this piece, Trinity La Fey breaks down Maïmouna Doucouré’s film Mignonnes, which has become extremely controversial.

The Mignonnes Question

by Trinity La Fey

Frenchwoman Maïmouna Doucouré, who wrote and directed ‘Cuties’ (English translation), a film which has sparked an online petition calling for it’s removal from Netflix’s streaming platform, has defended her work against the scrutiny it has come under (largely as a result of the way Netflix chose to represent her film), by asserting that we need to not “blame the girls” in these potentially accurate portrayals of their lives and behaviors.

As one of the many who has not seen the film, I have seen the promotional material: a still image from the film and text provided by an unknown individual describing a girl “who becomes fascinated with a twerking dance crew“. The children are eleven years old. The young actors are striking poses that are not hard to see as sexually suggestive. New to social media, my burgeoning role as SJW internet troll is shocking to me, mostly in my quick adaptation to this drug. Perusing the pile-on, there were shades of every argument: from people who had seen the film, explaining that it was about the sexploitation of young females; to people who, enraged, called for it to be removed from the streaming platform altogether.

The alarming normalization of sexualizing children has long been evident in Netflix.

Perhaps not so blatantly as now, but children’s, particularly girl’s, sexualization of themselves (by the age of seven according to Dr. Jessica Taylor) is something that has also long existed in this and other modern, civilized cultures and I would argue, needs to be addressed.

As the creatrix of this soft-core child pornography, Doucouré has here deflected the legitimate question about her responsibility as storyteller to the “sex-worker” argument.

No one said anything about blaming the girls.

The argument against pornography is that real people, in this case eleven year old girls, do the things in real life, in front of a camera. In the case of feature films, often exhaustively with rehearsals, memorization and multiple takes [nearly 700 underage girls auditioned for the lead roles]. It is not just a story anymore. It is perpetuation. Psychically, it is normalization, not a challenge, for participants and audience both.

The shame never belonged to the exploited. To have been exploited is a hard thing to admit in a culture that believes that the shame does belong to the exploited. I think that explains much of the drive toward liberal feminism among young women who do not have direct experience with, or on whose livelihood still depends the pay-for-rape industrial spectrum.

I agree that the film should be taken down, but the story will and must be told.

Disappearing unpleasant or untrue or unwanted theories, arguments or stories transforms them from reasoned, hard “No“s back into question marks.

Trinity La Fey is a smith of many crafts, has been a small business creatrix since 2020; published author; appeared in protests since 2003, poetry performances since 2001; officiated public ceremony since 1999; and participated in theatrical performances since she could get people to sit still in front of her.

Featured image: Mignonnes film poster.

by DGR News Service | Sep 11, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

This article was written by Malavika Vyawahare on 1 September 2020 and originally published on Mongabay.

- People gathered in the thousands in Mauritius’s capital, Port Louis, to protest the government’s response to a recent oil spill.

- The Japanese-owned freighter M.V. Wakashio crashed into the coral reef barrier off the island’s southeastern coast on July 25 and leaked about 1,000 tons of fuel oil into the sea near ecologically sensitive areas, before breaking in half a few weeks later.

- The stranding of at least 39 dolphins and whales near the site has sparked an outcry, though a link between the Wakashio shipwreck and the beachings has not yet been established.

- In a controversial move, the Mauritian government decided to sink the front half of the ship several kilometers away from the crash site in open waters, which some experts say could have impacted the dolphin and whale populations.

Thousands of people demonstrated in Mauritius on Aug. 29 over the government’s handling of a recent ship grounding that spilled 1,000 tons oil in the seas around the island nation. In what appears to be the latest toll in the incident, dolphins and whales have beached close to where the M.V. Wakashio freighter ran aground and broke up. Thirty-nine of the mammals have beached in the week to Aug. 28. Social media is awash with photos of the stranded animals, including mothers and calves.

At a press conference Sudheer Maudhoo, the Mauritian fisheries, marine resources and shipping minister, called the beachings a “sad coincidence.” Though a link between the deaths and oil contamination has yet to be established, disaffection has swelled in the aftermath of the spill, with protesters taking to the streets of the capital, Port Louis, and wielding an inflatable dolphin with “Inaction” written on it.

The Wakashio struck the coral reef barrier off the country’s southeastern coast on July 25; the damage to its fuel tankers led to a leak on Aug. 6. The fact that the ship lay lodged in the coral reef for more than 10 days before any decisive action by the government has become a sour point for Mauritians demanding answers from the authorities.

“The oil spill became like a culmination of growing frustration in the country. Since we have this new government, there were a series of issues and the Wakashio oil spill was the last straw,” said Mokshanand Sunil Dowarkasing, a former member of parliament who now works with Greenpeace in Mauritius. The vessel lay stranded in the vicinity of at least three sites of ecological significance: Blue Bay Marine Area; Pointe d’Esny, the largest remaining wetland in Mauritius; and the coral isle of Ile aux Aigrettes, which is a nature reserve. Facing mounting pressure from abroad and within the country, the government hastened efforts to pump out the oil that remained on board, even as a ship was at the brink of breaking apart. On Aug. 15, it broke into two, but by then most of the oil on board had been removed. The situation, however, has only grown murkier since.

This article was written by Malavika Vyawahare on 1 September 2020 and originally published on Mongabay. The original article can be accessed here:

https://news.mongabay.com/2020/09/mauritians-take-to-the-street-over-oil-spill-and-dolphin-and-whale-deaths/

by DGR News Service | Sep 10, 2020 | Colonialism & Conquest

A new space race has begun. Private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin have begun the process of privatizing the night sky. What comes next? Will humans colonize the solar system and beyond? In this third in a series of articles [Part 1, Part 2] Max Wilbert asks why this culture worships “progress.”

by Max Wilbert

“The mystery of life isn’t a problem to solve, but a reality to experience.”

– Frank Herbert

It began with wood and blood; trees and muscle power; the fire and the slave. This built the first megacities on Earth. The first civilizations grew: in Mesopotamia; along the Yangtze River and the Ganges; in the Andes; in Egypt; and elsewhere.

As they grew, they displaced other societies, tribes and nations who had existed for eons. By war or trade or marriage, assimilation or extermination, they grew, and as they grew, forests shrunk.

The limits of muscle and fire soon became apparent. By cutting down the forests, by plowing the earth and turning soil carbon into human carbon, they eroded the soil, they salinized the land, and what was a Fertile Crescent became dust. But these societies had created an ideology based on “more.” The result was war and a feverish search for new sources of energy and power.

The next frontier was to dig deeper, to find carbon that was buried deep under the soil in the crust of the planet itself. The burning of coal and oil was a revolution in energy. Suddenly mines could be pumped dry and shafts sunk deeper than ever before. Goods could be moved more quickly. Factories and war machines belched great clouds of smoke into the air, and the logging became industrial. The conversion of a living planet into a necropolis accelerated.

Coal and oil, when combined with the engineering necessary to create the engine, enabled expansion on a scale never before dreamed of. Soon nations had the power to move mountains, and they did. Coal and oil enabled the construction of the first large hydroelectric dams, and now the circulatory system of the planet was bound to civilization’s endeavors as well. And before long, the next boundary was breached: that of the atom itself.

This is the story of civilizations breaking the covenant humans had lived with for 200,000 years; the story of human beings constructing ideologies and megamachines that demand limitless power, and then pursuing that power to—quite literally—the end of the Earth.

Progress as Sort of God

There is a fundamental premise underlying not just capitalism, but all civilized societies: the premise is that “progress” in technological development is an inherent good; that any harm is overshadowed by this good; and that the pursuit of technological development and the power that results should be one of the primary goals of human society. Expansion is good. Growth is good.

This premise underlies not just capitalism, but civilization itself, and much of modern science.

This article is third in a series of essays responding to a scientific study published in the journal Scientific Reports back in May. The study models the future of global civilization, tracking population growth and deforestation, and finds that there is a 90 percent chance of civilization collapsing within the next 20-40 years. I discussed their collapse prediction in the first essay in this series.

The authors of the study theorize, as Salonika pointed out in the second essay, that the only way to avoid collapse is via expansion, especially expansion in energy generation, which they suppose would allow industrial civilization to surpass ecological limits and expand throughout the solar system. They write, “if the trajectory [of civilization’s technological development] has reached the Dyson limit we count it as a success [in our model], otherwise as failure.”

They are referring to a “Dyson Sphere” or “Dyson swarm,” a theoretical megamachine which would encompass a star and capture a large portion of its power output, which could then be used by a civilization.

The idea of a Dyson sphere has been around since the 1930’s, and has a rich life in science fiction. But it is not something to dismiss. Scientists have been working on the theoretical and technical foundation for space-based solar energy harvesting devices for many decades. More deeply, it is an idea that is deeply reflective of the ideology of civilization, which demands power in unlimited quantities. It is the same idea which has underlain civilization since the first slaves were shackled in rows and lashed and set to work building monumental architecture for the emperor. It is the same idea that drove the deforestation of the planet. It is the same idea that built the Grand Coulee Dam, and the Hoover Dam, and the Three Gorges Dam, and the Belo Monte Dam, and that will build the Batoka Gorge Dam unless we stop them. It is the same idea that has infected politicians and rulers and technocrats and theocrats and entire societies for thousands of years.

It is the idea that expansion is the highest good.

Exploitation as a Proxy for “Development”

It was not under capitalism but communism that Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev coined the eponymous Kardashev scale in in his 1964 book Transmission of Information by Extraterrestrial Civilizations. The scale he proposes “is a method of measuring a civilization’s level of technological advancement based on the amount of energy they are able to use.”

The Kardashev scale ranks civilizations as Type I (a planetary civilization, which can use all the energy available on its planet of origin), Type II (which can use all the energy within a given star system), or Type III (galactic civilizations). In this scale, a Dyson sphere corresponds to a Type II civilization. Global civilization today, using Carl Sagan’s extrapolations, is approximately at Type 0.73.

In this scale, the more energy a society can appropriate for themselves, the more advanced they are.

- Those who have slaves can appropriate more energy than those who do not.

- Those who cut down the forest and burn it can appropriate more energy than those who do not.

- Those who plow the grasslands under can appropriate more energy than those who do not.

- Those who break the boundary of the atom will have more energy than those who do not.

- And those who are willing to capture sunlight itself—through a Dyson sphere or other forms of technology—will have more energy than those who do not.

It goes without saying that striving for higher levels on the scale is the goal of most people in power. From the beginning, most western science has been underpinned by a philosophy that the more human beings can control nature, the better. From Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance thinkers to Francis Bacon and the Royal Society, scientists have willingly hitched themselves to tyrants and democracies alike to fund their unending curiosity, and in return they have delivered weapons, energy, and economic development.

Control and expand: this is the ideology of conquest.

The Study of Consequences

Legendary science fiction author Frank Herbert wrote in his classic Dune that “ecology is the study of consequences.” The term is appropriate, then, to describe the study of the consequences unleashed by the decisions made by civilizations up to this point.

We’ve already spoken of the forests that are now past tense and the Fertile Crescent that is fertile no more. Agriculture—not gardening, but totalitarian agriculture—is no more than organized appropriation of primary productivity, habitat, and soil fertility from non-human species to benefit a single species (humans).

Primary productivity, or photosynthesis, is the basis of terrestrial ecology—the basis of life on land. On average, in agricultural areas, 83% of primary productivity is extracted by humans, leaving 17% for the non-humans who remain. This is a consequence of civilized agriculture, just as global warming and ocean acidification are consequences of the choice to seek energy from coal, petroleum, and natural gas.

The Fermi Paradox and The Great Filter

We cannot speak of civilization, Dyson spheres, and ecology without discussing the Drake equation and the Fermi Paradox.

Astronomer and astrophysicist Frank Drake created the Drake equation in 1961 at the first scientific meeting on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI. The equation estimates the probability that there are other intelligent life forms in the galaxy with whom we might communicate. The equation is a rough tool, more thought experiment than precise scientific measure, and plugging in different variables can give wildly different results. It’s all conjecture; life has only ever been observed on one planet.

The Drake Equation, however, does suggest that there could be as many as 15 million planets with intelligent life in the Milky Way alone; we just don’t know. This is where the Fermi Paradox comes in. The Fermi Paradox is a mystery posited by Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi: given these huge numbers, why have we found no evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence? A 2015 study concluded that Kardashev Type-III civilizations are either very rare or do not exist in the local Universe.”

Why has SETI failed?

There are many possible explanations, many of them revolving around the idea that the formation of complex life-forms is actually extremely rare, and that life on Earth has passed through some sort of “Great Filter” to arrive at this. An alternative explanation is that societies that develop the ability to transmit radio waves and travel off their own planet tend to destroy their own ecological founds and collapse.

Each of these explanations is horrifying in its own way.

The Colonization of Space

Incidentally, rockets used in spaceflight destroy the ozone layer, release as much carbon dioxide in 2 minutes as a car would produce in two centuries, and are changing the composition of the upper atmosphere, releasing gasses and particles in areas they have never before naturally existed. And this process is accelerating as corporations such as SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic begin to colonize near-Earth orbit with thousands of satellites and increasing numbers of commercial craft.

It is expected that the number of rocket launches will increase by an order of magnitude within the next few years.

Another Path

Does it have to be like this?

Some would have us believe that science, technology, and progress are the only possibility—the only option that is thinkable. But is this true?

The science of conquest is not the only type of science. There is another; a science that is based on observation, thesis, and evidence, that is based on a peer-review that does not take place in university buildings, but rather in forests, in grasslands, along rivers, in the oceans.

This is the science of the Polynesian sailors, who set out across ten thousand miles of ocean on boats made of sustainably-harvested wood, who navigated the seas and found islands like a pin in the oceanic haystack without compasses, GPS satellites, or steel-hulled boats.

It is the science of the Kalapuya people, who practiced a scientific ecology through prescribed burning of their land, cultivating species beneficial to biodiversity and abundance not just for humans, but for all life, and thus gardened the entire landscape and created one of the most diverse habitats on Earth, and of the Klamath people, who use fire to geoengineer climate on a small scale by setting their hillsides alight when inversions cause the smoke to gather in their river valley, cooling the river and triggering the salmon runs.

It is the science of the Aborigines, who encoded language and culture in songlines and land, and created a continuous culture that has lasted at least 65,000 years. It is the science of those who remain, keeping these traditions alive, who often don’t use the term science, because it is too small a word for what they do.

There are other ways to live, ways that are no less complex or rewarding, no less respectful of human intellect, but which are build on relationship.

What future do we want? The dystopian future of science fiction? A world of control? A world of Dyson spheres and continental solar arrays? A world “red in tooth and claw,” where survival of the fittest means those who will extract more ruthlessly will gain power? Or do we want a world of connection and participation, a world of mutual aid, where we give back as much or more than we take?

I dream of a world where humans practice a different kind of science—not the science of conquest but the science of cooperation.

Max Wilbert is a writer, organizer, and wilderness guide. A third-generation dissident, he came of age in a family of anti-war and undoing racism activists in post-WTO Seattle. He is the editor-in-chief of the Deep Green Resistance News Service. His latest book is the forthcoming Bright Green Lies. His first book, an essay collection called We Choose to Speak, was released in 2018. He lives in Oregon.