by DGR News Service | May 7, 2019 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

By Will Falk and Sean Butler / Voices for Biodiversity

On December 18, 2018, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Wild Fish Conservancy threatened the Trump administration with a lawsuit under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for allowing salmon fisheries to take too many salmon, which the critically endangered Southern Resident orcas depend on for food.

The impulse to protect the orcas is a good one. Southern Resident orcas are struggling to survive — only 75 remain. According to the statement by the Center for Biological Diversity and Wild Fish Conservancy, “The primary threats to Southern Resident killer whales are starvation from lack of adequate prey (predominantly Chinook salmon), vessel noise …that interferes with … foraging … and toxic contaminants that bioaccumulate in the orcas’ fat.”

You probably assume, when reading that list of primary threats to the orcas, that the threatened lawsuit would demand an end to these harmful activities. But it doesn’t. Instead, the organizations are merely asking the National Marine Fisheries Service — the agency responsible for issuing permits to Pacific coast fisheries — to deal with alleged violations of the ESA.

The Center for Biological Diversity and the Wild Fish Conservancy aren’t asking that activities harmful to Chinook salmon, and consequently to the Southern Resident orcas, be stopped. They aren’t asking for noisy vessels that disturb the whales’ foraging behaviors to be prohibited. They aren’t even asking for an end to the toxic contaminants that accumulate in the whales’ fat.

Why aren’t they asking for any of these things? Because under American law they aren’t allowed to ask for them.

All they are asking is that these harmful activities receive the proper permits.

Right now, laws like the Endangered Species Act are the main legal means for protecting threatened species and habitat in the United States. But these laws only allow us to challenge permit applications and ask that projects complete the permit process.

While it may hard to believe, these permits are designed to give permission to cause harm. Regulatory agencies only regulate the amount of harm that takes place. They do not, and cannot, stop ecocide. Instead they allow for softer, sometimes slower versions of ecocide.

To understand this, it helps to know a bit about how the Endangered Species Act actually works. The Act prohibits any person, including any federal agency, from “taking” an endangered species without proper authorization. “Take” is defined as: “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.”

You might expect that the Act completely prohibits any activity that “takes” an endangered species. But it doesn’t. Under the Act, federal agencies may harm members of an endangered species as long as the activity is “not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species.”

While that may sound more promising, it isn’t. When a proposed action is likely to jeopardize an endangered species, the agency can then issue an Incidental Take Statement (ITS), which merely sets a limit on the number of individuals of an endangered species that can be taken.

In other words, a species that has already endured so much destruction can legally be further harmed if that harm is in compliance with certain terms and the correct forms are filled out.

So an ITS allows a federal agency to harm endangered species. But there are also Incidental Take Permits (ITPs). These allow private entities to harm endangered species. All a private entity needs to do to get an ITP is create a plan that purportedly minimizes and mitigates harm to an endangered species.

The irony is not lost on Professor J.B. Ruhl, who describes the situation in his aptly-titled law review article, “How to Kill Endangered Species, Legally”:

“Rather, when we strip away its noble purpose… at bottom the ESA is little different from the modern pollution control statutes which broadly prohibit a defined activity with one hand, then with the other hand give back authority to do the same activity under regulated conditions.”

In the original 1973 version of the Endangered Species Act, ITS and ITP exemptions did not exist. They are the result of amendments passed by Congress in 1982 to undermine several pro-environmental Supreme Court decisions that interpreted the Act as broadly protecting endangered species. Those amendments are a powerful and dangerous loophole.

In a 2011 report, a trial attorney with the Environmental Crimes Section of the U.S. Department of Justice, Patrick Duggan, found that ITPs are being issued at alarming rates — and with ever-broader scopes. “In the first decade after the 1982 Amendments, there were 14 ITPs issued, by August 1996, there were 179, and by April 2010, there were 946 approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) alone.” Even FWS has acknowledged this trend of permissiveness, recently noting how the number of approved plans has “exploded.”

Most people mistakenly believe that regulations are being enforced by regulatory agencies. They’re not. Some environmental lawyers call this the “regulatory fallacy.” Not surprisingly, this drains focus from potentially more effective tactics by funneling it into a belief that government agencies will actually protect people and natural communities by denying permits.

The system isn’t working — and it’s very unlikely that it will protect the critically endangered Southern Resident orcas. But why doesn’t it work?

To begin to understand why the Endangered Species Act is failing, it’s helpful to acknowledge perhaps the most fundamental assumption of the Act and all similar pollution control statutes, as Professor Ruhl calls them. That assumption is that we have an inalienable right to use the natural world for our own purposes.

The answer to the regulatory fallacy, then, is to turn this on its head. If we truly want to protect endangered species like the Southern Resident orcas, our laws cannot treat them and their essential food source as objects or property. Instead, we must acknowledge their inherent rights to exist, and create laws that uphold and enforce those rights. True sustainability requires transforming the status of nature from a legal object to a rights-bearing subject.

This transformation begins with granting nature the legal right to challenge the conduct of someone else in court. As Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas wrote in his famous 1972 dissent in Sierra Club v. Morton, this “would be simplified and also put neatly in focus if we fashioned a federal rule that allowed environmental issues to be litigated before federal agencies or federal courts in the name of the inanimate object about to be despoiled, defaced, or invaded by roads and bulldozers…”

In the US, the rights-based approach has been pioneered by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), a nonprofit, public interest law firm. Since 2006, CELDF has helped dozens of communities in ten states enact rights of nature laws. Their model uses a “Community Bill of Rights,” which declares that citizens of the city or county have a right to clean air, clean water, etc., and that the natural communities within its borders have a right to exist, flourish, regenerate and naturally evolve. Natural communities are specifically granted legal standing and citizens are empowered to bring lawsuits to enforce these rights. This is similar to the way guardians represent children in court.

Southern Resident orcas range from as far south as California and along the coasts of Oregon and Washington. If the communities along the West Coast had rights of nature laws, they could now bring a lawsuit on behalf of the Southern Resident orcas, with claims that fishery practices, dams, shipping activities and pollution violate the whales’ rights to exist, flourish, regenerate and naturally evolve. They could ask the courts to completely ban harmful fishery practices in order to protect the rights of nature, and to order those responsible for harm to pay for the regeneration of the natural community. They could seek this relief from the courts because the fundamental rights of the ocean and its residents are being violated.

What’s more, because the plaintiff in such a lawsuit would be a whole population of salmon or whales, or even an entire ecosystem like the Salish Sea, the damages awarded would be measured according to the losses suffered by the natural communities themselves. And any award of damages would go toward the restoration of those communities, rather than to human plaintiffs who might not use it to benefit the ecosystem that has been damaged.

“We’d be having very different conversations and much more effective results if we approached recovery with the orcas’ best interests in mind,” says Elizabeth M. Dunne, Esq., who is part of a coalition that helped draft the Declaration for the Rights of the Southern Resident Orcas, led by the grassroots community group, Legal Rights for the Salish Sea. Dunne explains that, “by signing the Declaration, we want people, organizations and governments to recognize that the Southern Residents’ have inherent rights, to recognize that we have a responsibility to protect those rights, and to commit to taking concrete actions to protect and advance those rights.”

Environmentalists who engage within today’s regulatory framework and rights of nature proponents begin in the same place. They both want to protect the natural world. But the way they frame the issue could not be more different. Environmentalists who rely on regulatory laws frame the issue as one of improperly prepared reports or how many parts per million of toxins may permissibly be released into water supplies. For example, the Center for Biological Diversity and Wild Fish Conservancy want to protect the Southern Resident orcas, but all they can ask for under the ESA is that the responsible federal agency “reinitiate and complete consultation on the Pacific Coast salmon fisheries” with new scientific information.

Rights of nature proponents, on the other hand, affirm nonhumans’ value as subjective beings, framing the issue in terms of whether a proposed action violates their fundamental rights. Though we cannot put an orca on the witness stand to testify about the impacts that the National Marine Fisheries Service’s plan has on her species, empowering humans to speak for her through enforcement of her legal rights brings nature’s voice directly into the courtroom.

Originally listed as endangered in 2005, Southern Resident orca numbers have continued to decline. The Center for Biological Diversity reports that the population is at its lowest point in 34 years. And, “In 2014, a population viability study estimated that under status quo conditions, the Southern Resident killer whales…would reach an expected population size of 75 in one generation (or by 2036).” Instead, it was just four years later that the Southern Resident orca population stood at 75.

In the end, the only measure of success in this case should be the whales’ recovery. The people of Washington aren’t concerned that regulations haven’t been followed— we’re concerned that our neighbors, the Southern Resident orcas, are starving. We’re horrified that these beautiful animals’ right to life is not being respected and that their ecosystem is being destroyed. And we’re outraged because deep down we believe that the natural world does have inherent value — and therefore inherent rights.

It’s time to stop begging for regulatory table scraps. It’s time to have the courage of our convictions and create new laws that recognize the inherent rights of the Southern Resident orcas and the Salish Sea as a whole to exist, flourish and evolve.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 6, 2019 | Male Supremacy

Featured image: screenshot of a video taken of transactivists assaulting women at a presentation in Buenos Aires, Argentina. See video link below.

by Luis Velázquez Herrera / FRIA (Independent Radical Feminists of Argentina)

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, a group of radical women are about to speak in the middle of a crowd at the assembly “Ni Una Menos” (Not one more woman) that took place anticipating preparations for the coming March 8th, you can listen to the noise and a unison shout against them to “go away!”

There is a man standing beside them yelling with a defying fighting pose, pointing at them aggressively. He is dressed in a plaid miniskirt and white shirt. He is far taller than the average women present.

From the multitude of radical women that are preparing to speak, a woman with a calm expression appears, she wears a black blouse and short hair, asks for the microphone: “Freedom of speech, female partners, freedom of speech”!

Her name is Ana; she knows she is unwelcome, as are her partners from FRIA/Feministas Radicales Independientes de Argentina (Independent Radical Feminists of Argentina) and RADAR Feministas Radicales de Argentina (Radical Feminists of Argentina). They are attending what they thought was a democratic assembly to present their abolitionist stance against sexual exploitation. The man dressed in a miniskirt, who hasn´t stopped threatening them through shouts and flinging fists in the air, throws himself over her to take away the microphone.

Surrounding women stopped him and took him away. They defend themselves. A woman wearing a yellow jacket stands out and drives him away vehemently. She is thin and short in contrast to him. You can see in her face the fury for survival, the rage of knowing she is being invaded, and the rest of the radical women act with her. You can see many women stopping the hands of the man. They know he is a man, even though he claims vocally to be otherwise. He has invaded them and they stop him.

In a feminist assembly, women would take out the violent man in a shout for self-defense, protecting the women being harassed. Very likely, they would make a complaint to set a criminal record against a potential woman-killer and would continue talking about immediate and future security for harassed women, and all women.

But this does not happen. It is February 15, 2019. Three decades ago feminism, in the dawn of neoliberalism, changed from being about and for women to caring for aggressors and covering up pimps—in general, to protect men. Because of this, harassed women are forced to abandon the venue, being booed by the public. Nobody will protect them or even consider their safety. Nobody but themselves will take a stance against that violence; they will withdraw, scared, hurt, damaged by the support that other women gave (in a self-proclaimed feminist assembly) to a man harassing women. I found the name of the name of that woman in social media, who, in spite of the hooting crowd, came out to speak calmly before being physically attacked. Her name is Ana Marcocavallo, 43 years old, psychologist and professor in pedagogy. She lives in Buenos Aires and is a radical feminist who forms part of FRIA/Feministas Radicales Independientes de Argentina, we had a phone interview and chatted.

I´ve read what happened, are you okay?

At the moment it was quite terrible, emotionally, physically and politically…

Did you attend as member of a group?

I am part of an organization called FRIA, but at that moment various groups attended, FRIA, RADAR, Abolicionistas Independientes (Independent Abolitionists), and if I’m correct, Mujeres Autoconvocadas (Self-summoned Women) among many.

How did you arrive to Radical Feminism?

I followed the typical path many do to feminism, arriving through mainstream feminism, liberal feminism. I got to radical feminism fairly recently, only four or five years ago, which was due to fellow feminists who taught me, who gave me readings, which honestly, I read reluctantly. In that way I discovered a new world where I felt that all the ideas I had myself, and which I discarded as wrong, had a place and there were more people who thought like I did.

How has it been to organize as Radicals?

Honestly, it was difficult. At the beginning there were many radicals spread afar, placard radicals [closet radicals] so to say. It was important to find each other as fellow mates, first with small groups to then realize that these groups grew or that other small groups, with which we could coordinate, existed. But by small groups I´m talking of very small groups. For example, some groups from a whole province would only have two members. Currently, we are organized through a WhatsApp group of Radical Feminists from different provinces and the capital, from different gathering groups, a little of everything, and through that group we are discussing things, organizing, generating a tighter Radical Feminist nucleus. At least now we know others are around, even though we might not agree on all our contents.

Through social media we are in contact with radical feminists from México, Uruguay, Paraguay, Spain, US, UK… and we can see that in those countries they are living the same as we are, an advance of Liberal Feminism, which is made up of a combination of ideas like Queer Theory, transactivism and legalization of prostitution, things you won’t see in other countries. I believe that in Argentina, we live a weird case, other countries have told us, where people who are trans, drags and transactivists are also prostitution abolitionists, which you will never find in other countries.

This is how historical reality is marking us through “transfeminines” who have been building the abolitionist movement, who have left us with disputable laws regarding gender definitions, but what I believe is that these theories go hand in hand, prostitution legalization is leading transactivism and Queer Theory, who breaking a split within the abolitionist movement.

The fact that some people with radical ideas who were also trans or drags or that reified that identity, generated a kind of strategic unit where feminist women that preceded us renounced to some matters. For example, the Ley de Identidad de Género (Gender Identity Law) in Argentina, which turned out to be an incredibly deceitful law.

Why an assembly called “Ni Una Menos” (Not one more woman) has among their members people that favor sexual exploitation and are pro-transactivism?

Precisely, it is paradoxical. Basically, the problem lies in that Ni Una Menos in Argentina is in favor of legalizing prostitution and adopts a Liberal Feminist stance. As such, us abolitionists, we fight for our spaces and are being cornered, to the point we do not know if it is convenient for us to go after those particular spaces or try to generate new ones.

How does the phenomenon of the Green Wave and these last happenings relate?

The Green Wave is specifically a fight for legal abortion, for it to be safe and free. What happens within feminism is the occurrence of strategic units, where we are united by basic principles but differentiated by others. In this case, the Green Wave has such populous numbers because all sectors offer support, pro-legal prostitution, abolitionists of prostitution, Radical Feminists and Liberal Feminists.

That does not happen in Mexico, we never prefer to march next to Liberal Feminists under any circumstance….

Of course, what happens is that just by numbers, Radical Feminists cannot lose the chance to march with them but we march separately. It is like throwing wood to a fire, it does us no good, politically speaking, because in this moment we are being isolated, followed and threatened by liberal feminism, the kind of feminism that does not think like we do, which means, the greater majority.

What would you say to a feminist in the effort of understanding what transactivism is?

Transactivism is difficult to explain, but what we dispute is not the existence of trans people—we are not in favor of the annihilation of trans people, what we are accused here in Argentina, where we get compared with Nazis—but that our struggles can converge in some point. Meanwhile in other points, when they oppose radically against feminism, we will never accept them passively as machismo has always imposed over us women.

And those matters are the redefinition of what being a woman, where we are not allowed to define ourselves as women, which is what patriarchy has always done, it has told us “women are that which are not men,” and now it turns out that we are “cis-women,” the “women that are not trans,” that is what we are discussing now.

We argue against the current definition of gender, from the transactivism vantage, it is defined as “identity.” We have a vision of gender as oppression, oppression by material causes, not merely ideological. From transactivism’s vantage point, gender is the cause of oppression. We think that gender itself is the oppression. These theoretical differences are interpreted by transactivism as a denial of their identity, but basically it is a tautology to believe that “women are women,” that “women’s day is women’s day.”

We do not deny their existence, nor their struggle or problems. What we deny is that their problems comingle with ours, to have our spaces colonized, and of course, that they hetero-define us, which is to say, that we cannot define ourselves by ourselves, because that erases us as political subjects, and if women are troubled by something, it goes beyond countries and specific problems, and it is precisely that we are women and that we have particular pains and pangs for being born with determined genitals.

Drawing by Amanda Dziurza

And how would you explain abolitionism?

For me, abolitionism was one of the gateways to radical feminism. Radical Feminism is abolitionist by nature, however, not all abolitionists are Radical Feminists, because to begin with, not all abolitionists are feminists. It is a weird phenomenon, but that is how reality works.

Abolitionist feminisms, as I understand it, is the feminism that opposes rape culture and prostitution culture. Prostitution is seen as rape; simultaneously, pornography is understood as the educational method for prostitution and rape.

We are accused for being against the prostitution system, meant as normalization of men’s will and capacity to do to women’s bodies whatever they wish to, privately, through marriage, or publicly, through any other media or means, rape for pay, is that we are moving against prostituted women and their rights, which is false, a fallacy, a misrepresentation. In the same way as radical feminists, we are against a definition of gender by transactivism. And we are accused of being against trans people, the cause of their sufferings, their murders, and so on, which ignores that the perpetrators are men and not us feminists.

Under this stance it is that the assembly Ni Una Menos, asked you to present ourselves as an abolitionist block rather than Radical Feminists.

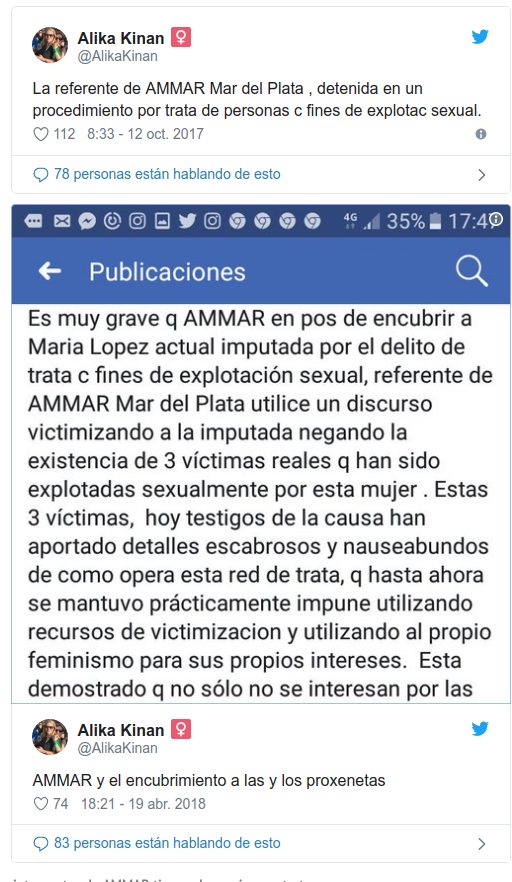

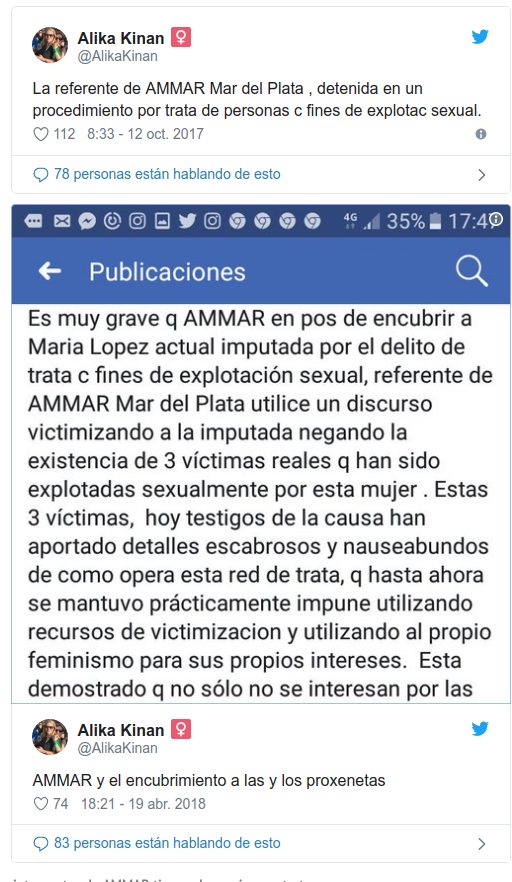

I asked him to present us as cold, RADAR, nothing more, and they present us as radical feminists, so right there the situation that will not let us talk arises, encouraged by Georgina Orellano who shouted at us “TERFs, TERFs, TERFs!” Georgina as you know is the most visible faces of AMMAR, which is the group that carries out regulationism, the pro-pimping.

It wasn´t that long ago that I saw some member of AMMAR with legal complaints for prostitution…

They have complaints for prostitution and even several of them remain under legal process. And precisely, many of the stances they present themselves with is to attack the Anti-Prostitution Law that has taken us so many years to obtain. One of our requirements is that the Anti-Prostitution Law is inviolable.

And even when they are marked by prostitution complaints they still receive support?

Yes, because there is a lot of misrepresentation going on, extortive appeals to the feminine socialization that we must embrace at all costs, we feel guilt that we are the sole root cause, we feel guilt to have exclusive spaces, so we have to adhere to all other causes, because otherwise, it will be our fault they are discriminated, it is our fault they suffer. Dialogue is channeled that way.

So you get up there to speak with other fellows of the assembly Ni Una Menos…

There were many of us, we were eight women, they snatched the microphone from my hands, and started chanting so that we would not be allowed to speak. There were some women asking “let them speak, I am not in agreement with them, but they must have the right to speak,” at some point I got the microphone back. The turmoil was loud, and I stepped ahead and shouted “Freedom of speech, women, freedom of speech!” so that I could read my plea and following me my fellow team from RADAR their own pleads. At that moment, I´m not sure to say if it was or not a transfeminine, or a person self-considered binary, I can´t tell, but he started an attack against me which was stopped by my friends.

Practically, he threw himself to punch you, did he hit you?

Luckily no, first he grabbed me by my t-shirt neck and supposedly was trying to snatch the microphone with the other hand, but he had the attitude that he was about to punch me, so I pushed him backwards. I swear, I reconstruct the moment through the videos from all perspectives, because honestly at that moment a fellow woman mate grabbed him from his back and pulled him, and from what I see, he also throws punches against her, that luckily don’t reach her, because surely because other people from other groups were transactivists, recognized his strength and threw him to the ground. It seems to me of extreme severity that the whole assembly shouted supporting support for transactivism after a women or many might have been punched. And it is incredibly severe that, not only he attacked me, but that he tried to punch a minor.

After this moment, what happened? Did you leave?

After this this moment in the assembly there were many people that tried to intervene for us, so that we had our right to speak, some fellow members would dissuade me, “come on, come on” but I said “no, we will stay, we will not go down.” Many people intervened, but told us, “no, there is no solution.” A representative of Ni Una Menos, took the microphone, spoke instead of us, against us. Georgina Orellano also spoke against us asking that we should not get the microphone, that we should not be allowed to speak. They insisted that we left, I said again no, that we would speak, and well, the third time my fellow members told me to leave, realized there was no solution, not to say that the supposedly democratic assembly was expelling us, and that we needed security because there were women, some very young, minors, and nobody listened. It could have gone much worse. When we left, we did it alone, by ourselves with very young members, but nobody of NUM guarded our security, and there was no communique, nobody talked about it, it was made invisible. This got to social media by our own complaints.

I read that the comments that insulted the radicals were directed mostly against young women, was this so?

No, liberals are also very young. Last year a historical feminist of abolitionism called Raquel Diselfeld was among the few that were with us in the middle of the turmoil. For example, she talked on the assembly of sexual liberty for women, pleasure, orgasms, she talked about how this has nothing to do with prostitution and she was booed by a bunch of girls who were not even yet born when this woman was already fighting for our rights, which means, that not only young feminists are in radical feminism, they are in all kinds, and fortunately the youngest of them are mobilized by general feminism, radical and liberal feminism. It is a time when young women are acquiring a level of consciousness that when we were of their young age didn’t have.

When you attended the assembly of Ni Una Menos could you foresee the attack?

We did foresee that something like this could occur. We always remain optimists, to strive for the best, that is to say, that we would be prevented from speaking and that we would have to withdraw.

During this week and the previous one, a kind of social media war was held against us, where many venues published notes that I consider terrible apologies for crime; for example, a news server called Página 12, asked for organizations that are contrary to radical feminism or that don’t manifest any posture, to abandon their tepidness and attack us.

And during these two or three weeks many articles of political parties misrepresented our posture and in social media there were many attacks and threats, even to set us on fire or break the teeth of radical feminists.

One always takes it with good spirit, the things that happen on the internet, everybody blathers on social media, but nobody is direct. I would at least consider that there would be somebody that would consider it literally and in effect that was what happened. We tried to get there the most possibly organized in our security to avoid this kind of things, but we did not expect that it would spread with such virulence and particularly, with such approval from organizations like Ni Una Menos as did the rest of the assembly.

Did you know the aggressor? Had he threatened you before?

I did not know him, but some members of RADAR noticed that this person was taking pictures of them.

So, how did you feel? How do you feel now?

Honestly, what I think now is I’m glad it did not escalate, it could’ve been much worse, I could’ve been injured if it wouldn’t have been for the intervention of my fellow companions that exposed themselves way too much, but it didn’t get any worse by miracle.

At this moment, I am hurt, emotionally fatigued, very tired, in this moment I feel personal desolation because the whole abolitionist block to which we belong, is not repudiating a violent physical action against a fellow woman, even though it would have or not been me. It establishes a very serious precedent that we do not repudiate a violent action against a woman in spaces that should be safe, we are seen as hate speech, meanwhile we would never intend or even occur to punch a person, trans or transactivist or woman transactivist, queer or even women against women’s rights, like those that are against legalizing abortion. We have never done it and never will, what we have suffered are threats and physical violence.

Let me understand you, liberal feminists have not repudiated the violence, but neither abolitionists have positioned themselves against the violence you lived through?

A letter for general repudiation has been prepared, and it has been signed by too few, the majority of signatures come from radical feminists, we are helping ourselves, but we are not having the slightest help of the Argentinian abolitionist block, we are receiving support from the rest of the world, as I said, US, UK, Mexico, Uruguay, Chile … but basically in Argentina we are not receiving enough support, and that truly breaks my heart.

What is your analysis of this situation?

I believe that the general objective of the attack was an excuse for legalization of prostitution adherents to blame radical feminists of breaking the abolitionist block, just as is happening now. There is a part of abolitionism that does not want to be related with our posture. We are not telling them to adhere to our posture, but simply to repudiate the physical attack.

It seems like bullying in school, a boy bullies another boy and there is a reaction of the bystanders like a great public that also engages in a passive way, because that way they avoid being the attack target. I believe the situation is like this or at least I understand it this way.

Regarding yourself, what follows next? How are you coping with all of this?

I am currently keeping out of the streets for a week, I need protection, I won’t go out with other people, at least for a week. There are actions I cannot participate in, for example next Tuesday there will be a meeting pro-choice to which I will not be able to go, so that my face is not recognized and to avoid other situations. As I said before, I work in institutions of pedagogy sponsored by the city government. So if I say something or they say I said something against the Gender Identity Law (which states that any person has the gender with which they themselves self-designate, without any other norm or explanation, simply put, I call myself a man and I am a man, I do not even have to change my dress code), the situation would be dangerous for me, I could lose my job.

I had to go through something like that, some transfeminine summoned men to find my address and attack me, luckily they didn’t, but I understand, it is a tough situation, a hard emotional punch…

Exactly, it’s a situation to fear, if you really have to yield to getting silenced.

It is a tactic of these people, I believe we have to take some time for ourselves, but what they can’t predict is that we continue in dialogue with other women.

I believe that all we can do is create alternative spaces and to continue honest theory and spread it, but by some way it is as if we were mute, the prejudice is so big that we will not be heard.

Editor’s note: Feminist Current’s Raquel Rosario Sanchez also interviewed two members of (FRIA), Maira and Ana; read this interview here.