It is easy to get lost. The digital world exists parallel to the real, and just by flicking a finger across a piece of glass, one can open a doorway to all of the happenings any other human has written of, or photographed, or filmed. My morning ritual includes making a cup of tea, hopefully before my daughter has woken, and through the steam that rises from my cup I read what news of the wider world has come through my various feeds.

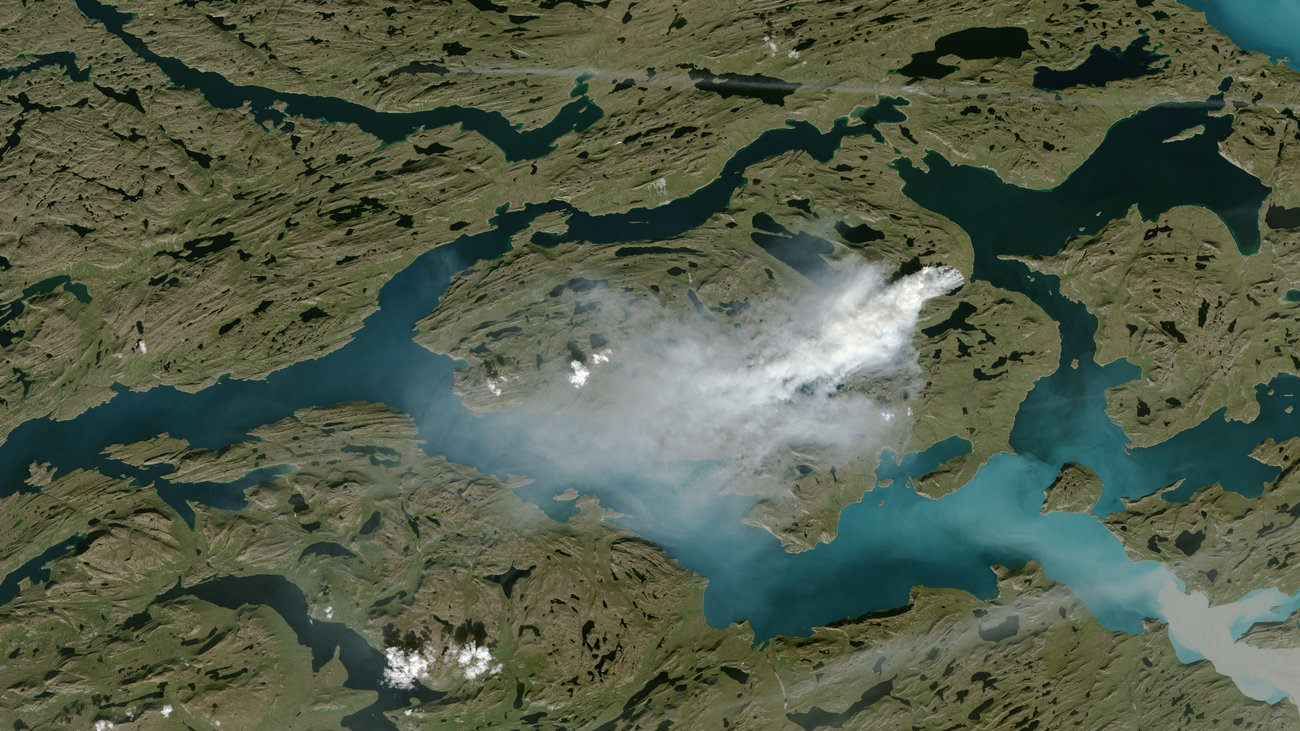

Fires rage in the Arctic, and in Greece, and in the American West. Heat has gripped the globe from Japan to Algeria to Portugal. There are floods, and parched farm fields, desperate refugees, and the most grotesque horror show of state sponsored famine and homicide in Yemen.

Pounding footsteps move across the floor from my daughter’s bedroom through the kitchen. I exit the digital. My daughter lumbers to me with tired eyes and I know she wants to be picked up, and to be held.

“Oh, my girl. My wonderful girl.”

She doesn’t say anything, her head on my shoulder, facing away so that I can smell her long hair. My exhale is deep and satisfied. She is right where I want to be. An hour later as we walk our stone driveway to go feed our chickens and ducks, I watch her small legs plodding along in pink plastic rain boots. The air is cool, actually, and I realize that this is my real, and that all of those terrible things I read about in the quiet dawn are far away, if they exist at all.

—

I have a fascination with orienteering. A while back a friend gave me his compass, which his father had given to him. I already had a compass, a cheap one that stayed packed in my camping bag. This new one my friend gave to me is much nicer. It has a weight to it that makes it feel significant and truthful, like the weight of a proper kitchen knife or an old, leather bound dictionary.

Upon receiving this gift from my friend, I realized I only ever used a compass to figure out which direction was which, but that I really had no idea how to properly use a compass in accordance with a map. So I began to read instructions on how to do so online, and even watched some videos on orienteering.

The word “orient” is saddled with an enormous historical and social burden. It is a derivation of the latin word for “east,” (the opposite being “occident,” a derivation of “west”) and is typically used to refer to the continent of Asia. Of course, what is “east” (or west, for that matter) really depends on where you are standing, so to conceive of the orient as Asia is to be speaking from a European perspective geographically, or at least as one influenced by European perspective. This is all rather contemporary though, as in Ancient Rome, anything south of the city of Rome was the Orient, as they had drawn in their minds an east-west line running through that city, and made determinations based on whether one lived above or below it. We seem to often set ourselves as a fixed point, the pivot of the spinning needle that whirls around us.

A map is wonderful, as it is a representation of terrain. But if you don’t know where you are, a map can be worse than useless. A compass is very useful, as it can point you in a cardinal direction. But without a map, the name of any given direction becomes trivia.

To “orient” seems to literally mean to find east, the direction we know we can reliably look to find the rising sun. When lost, one must orient themselves or remain so. One must align the compass with the map before shooting a bearing and heading out into the wilderness.

—

In my moments of greater clarity, I want to absolve myself of all political inclination. If I ask myself, point blank, “what is it I am most concerned about?” the answer comes quite quickly: Ecology, the living world. My great worry regarding the world at large centers on the fact that human industrial civilization is every day bringing the web of life closer to the brink of total collapse. Through climate change, extinctions, pollution, the promulgation of invasive species, and the conversion of wild spaces into regions managed and exploited for extraction and production, human civilization is destroying everything upon which it stands. With such an insurmountable threat bearing down, it seems silly to get drawn into conflicts over petty human arguments. Of course, most of what is trumpeted by the TV and print news seems to be just this, at least in comparison to the storm looming over us.

But it happens. I get pulled into the gyre. Despite my desire to stay focused on the material world beneath my feet, the political nature of industrial collapse maintains itself as undeniably evident. As the conditions under which people exist continue to get worse, conflicts expand, and those in power exploit these circumstances for their own gain. Thus it is that ideologues create out groups of others – immigrants, Muslims, black folk, the poor – who they soak with blame for the downward trend lines that define our age. So it is that we have endless wars at home and abroad, with piles of dead victims of drone assassination and cages full of terrified children.

Like it or not, collapse is political. Will the downward slope of Hubbert’s peak be pocked with debt prisons or bread lines? Will the despair of climate chaos be met with concentration camps or communes? Will we slouch towards Olduvai while erecting walls or by tearing them down? Even if we believe all our best efforts will fail us, even if we believe that the wounds we have inflicted on the world are too deep to heal, and that a great suffering is certain, wouldn’t at the end of it all we prefer to fail at decency than to succeed at evil?

Of course, determining the difference can be quite tricky. All men mean well, it is said. Good and evil are meaningless terms, like north and south. If you know nothing of the terrain, if you have no map, you’re likely to just walk downhill because it’s easier.

—

“The core question that brings liberalism, conservatism, nationalism and identity politics into conflict with each other is a fundamental one: who has the authority to describe society? Whose version of history will be heard?”

This is an excerpt from a recent editorial in The Guardian by William Davies entitled, “The Free Speech Panic: How the Right Concocted a Crisis.” I was struck by the clarity of this concept. So much of the current argument, or rather, the tangled mess of arguments surrounding politics, individual identity, national identity, and so forth stems from this very conundrum. Who gets to draw the map? By whose standards do we orient ourselves?

Daily the world is changing in ways that were not foretold by those who have been tasked with explaining reality. By neglecting to confront the crisis of net energy decline, by declining to confront the crisis of debt based money on a finite planet, by declining to confront the crisis of ecological overshoot, the social caste of media makers and politicians have left people scraping to understand the knock on effects that have rippled through society because of these very crises.

People are finding themselves lost in a wilderness of information that runs contrary to the official “everything is fine” narrative put forth by the state and capital. In this rugged and dark place, people are seeking to orient themselves so that they can understand just what is required of them in order to survive and to provide a future for themselves and their families. Whether it is a young college student wondering if it makes sense to take on a debt load in order to attain an education, or a middle age worker wondering why the hell it is so damn hard to pay for a home, and food, and healthcare for their family, people eventually recognize that the explanations for the world around them that they are being fed by those in power do not match the geography of their day to day existence.

When the political narrative one has been given fails, all a person can do is look around and scan the horizon for recognizable features, looking for enough of the familiar so they can finally mark an X and at least understand where exactly they stand.

To orient oneself in a social space can be difficult, and one ultimately does so by recognizing who they are not. Other people become boundary markers, warnings of what not to do, how not to be. Group identities form, people join teams, they carry flags, we don’t necessarily know who we are, but we damn well know we aren’t them.

You’re with us or you’re against us. Better dead than red. Bash the fash! West is best. Resist! Traitor!

Who gets to draw the map? As climate change progresses and the wealth gap grows wider and the pain and struggle of every day life grows more intolerable for the average person, this question will be the hill we die on.

—

My wife plunges a knife into a dark green watermelon. It is near perfectly round and about the size of a bowling ball. The second one we pulled from our garden this summer, it is at a perfect stage of ripeness. Standing in the kitchen the three of us spit small black seeds into a glass bowl as we enjoy the sweetness of the fruit.

The rinds get dumped in the chicken paddock, and I lock the door to the coop. The sun has set behind me as I walk silently back towards the house. Even when we tell people how to get here, our little plot of land can be very hard to find.

Originally published on Pray for Calamity. Republished with permission.