by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 21, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling, Protests & Symbolic Acts

By Hannibal Rhoades / Intercontinental Cry

Last week, a 3,000 person-strong people’s caravan, or Lakbayan, formed on the island of Mindanao to protest the criminalization and murder of Indigenous Peoples and environmental defenders in the Philippines.

Uniting Indigenous Peoples, peasants, workers, faith groups, teachers and youth, the caravan marched for three days and over a hundred kilometers from Davao del Sur to Koronadal City under the banner ‘Resist imperialist plunder! Stop Lumad killings!’

Though the numbers reported vary, the organizers of the caravan say 144 indigenous people, environmental defenders and human rights activists have been the victims of extrajudicial killings during the reign of incumbent President Benigno Aquino.

In a statement released before the Lakbayan, the groups connected these killings and rights abuses to the increasing presence of the extractive industries in Mindanao and the Philippines.

“These human rights abuses glaringly persist in the ancestral domains where the big and foreign mining companies and agri-plantations operate,” they said.

These killings form part of a wider pattern. According to research by UK-based think tank Global Witness, two environmental defenders are killed every week as they work to protect their lands from being appropriated and exploited by mining companies and other industrial interests.

In recent years, the Philippines has become a hot spot for these killings. But, as is the case around the world, very few of those responsible for the murders of environmental defenders ever see a court of law. Around the world between 2002-2013, perpetrators of such killings were brought to justice in less than one percent of cases.

STOP LUMAD KILLINGS

On Sept. 1, 2015 educator Emerito Samarca and two Lumad leaders, Dionel Campos and Aurelio Sinzo, who opposed large scale mining, were brutally murdered in Lianga, Mindanao. According to local reports, the men were killed in the heart of the community by members of the Maghat/Bagani paramilitary group, attached to the 36th Infantry Battalion of the Philippine Army.

Speaking at COP21 in Paris, Clemente Bautista, National Coordinator for Kalikasan PNE, described how the Armed Forces of the Philippines and affiliated paramilitaries are implicated in the terrorization of Indigenous and peasant peoples.

“The government is using militarization to protect corporate mining in the Philippines. They use the state military forces including paramilitaries to secure mining projects, quell the people’s resistance, and sow fear among the people, particularly those in mining-affected communities. Mining corporations, military and paramilitary groups employ violence such as harassment, illegal arrest and assassination, targeting anti-mining leaders,” he said.

The killings of Samarca, Campos and Sinzo are the latest in a spate of murders that has seen 56 Lumad leaders assassinated for protecting their lands and communities.

The “Lianga Massacre,” as it has become known, sparked international outrage and a day of solidarity and action that called on the Philippine Government to Stop Lumad killings. But the more diffuse consequences of the terror these kinds of killings are designed to produce have been underreported outside of the Philippines.

The relentless persecution of the Lumad People is creating a climate of terror in Mindanao that is profoundly impacting the freedom of the Lumads to live their lives freely.

In their statement before the three-day Lakbayan, organizing group Soscskargends Agenda revealed how the rising tide of violence in Mindanao has contributed to the internal displacement of up to 40,000 Lumads. The Lianga Massacre alone forced over 3,000 local Lumads to flee their isolated villages in Surigao del Sur to nearby towns, fearing for their lives.

The constant threat of violence in Mindanao and the panic migrations that result are having a particularly negative impact on Indigenous children. According to Soscskargends Agenda, at present 9 out of 10 Lumad children have no access to formal education and 87 Lumad schools are suffering from “various forms of military violence”.

“The 36th IB Philippine Army-Magahat/Bagani rampage at the ALCADEV School shows that the Aquino government has dropped all pretenses of adhering to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international human rights instruments,” say the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines.

The Lakbayan gave the groups involved an opportunity to elevate these underrepresented issues and create a platform for several urgent demands.

The groups are calling upon the Philippine government, first and foremost, to stop the killing of Lumad people, protect indigenous and peasant schools in Mindanao, and pull the plug on the large scale multinational mining projects that they say are helping fuel poverty and violence in the Philippines.

THE RESOURCE CURSE

Mindanao has become known as the “mining capital” of the Philippines. The island is peppered with 500,000 hectares of mining concessions, an area almost eight times larger than Metro Manila, the National Capital Region of the Philippines. These concessions have overwhelmingly been granted to multinational corporations, many of which are registered in Global North nations such as Canada.

Other islands in the Philippines, estimated to be the sixth richest nation in the world in terms of mineral and metals, have experienced a similar expansion of large scale mining since the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 (Republic Act 7942). The Act liberalized the country’s mining sector, promising economic growth and development through the exploitation of the country’s natural resources with the help of multinational corporations.

However, many Filipino civil society and indigenous groups argue that the liberalization of the mining sector has led to rising poverty, not prosperity, for Filipinos.

In a recent report,* Philippine people’s network Kalikasan PNE write that, based on data from the Philippine Bureau of Internal Revenue, between 1997 to 2013 less than 10% of mining revenues generated in the Philippines stayed in the country’s economy. According to their research, mining contributes only 0.7 percent to Philippine GDP and provides just 0.7% of employment.

The significance of these figures is emphasized when the costs mining corporations inflict on ecosystems and local communities are considered. The presence of multinational mining corporations in the Philippines has unleashed a tidal wave of environmental destruction on local indigenous and rural communities, costing thousands of livelihoods, devastating ecosystems and sustainable local economies.

The Marcopper disaster at a mine the owned by Canadian multinational Placer Dome on the island of Marinduque provides a good example.

On March 24, 1996 a sealed mine tunnel connected to a pit containing 23 million metric tons of mine waste fractured, leaking between 2-3 million tons of the waste into the Boac River. Residents of twenty local villages were forced to leave their homes, some of which were totally inundated by the flash flood of mine waste.

Agricultural fields were also flooded and the rapid destruction of all aquatic life in the Boac, a key source of livelihoods for local fishing communities, led the Philippine government to declare the river dead. Local peoples had already suffered decades of chronic environmental pollution, loss of livelihoods and ill health as the result of mining.

Dozens of other mining disasters have occurred in the period since the Mining Act of 1995 was passed. “Simply put,” write the authors of Kalikasan’s report, “we have experienced two decades of mining plunder.”

RESISTANCE AND MILITARIZATION

The two decades since Mining Act of 1995 was signed into existence have also been characterized by escalating resistance efforts from Indigenous Peoples, peasants and their supporters at the local, national and international levels.

Indigenous Peoples in particular have taken a stand to defend their territories, even taking up arms to protect their lands. In some cases this sustained resistance has been successful in preventing mining projects going ahead.

In June 2015, the Indigenous B’laan people and Philippine environmental groups celebrated mining giant Glencore Xstrata’s decision to pull out of the highly contested Tampakan copper-gold mining project. The company had been attempting to get mining under way since taking ownership of the project in 2001, but met powerful resistance from the B’laan.

The Philippine government’s response to such strong, sustained and well organized resistance has been to increasingly militarize areas where multinationals are operating, as seen in the case of Samarca, Campos and Sinzo.

The organizers of the recent Lakbayan say the current Aquino government’s “vicious internal security doctrine,” Oplan Bayanihan, is being used as a cover to to attack the schools, communities and leaders of those who actively resist mining.

The stated aim of Oplan Bayanihan, a government counter insurgency program, is to squash the New People’s Army (NPA), a communist guerrilla group that has been warring with the Philippine government for over two decades. However, the powers contained in the plan are also used to criminalize anti-mining activists who threaten the interests of multinationals in regions like Mindanao.

These activists are frequently accused, by the government, military and paramilitaries, of being connected with the NPA. Branded as anti-government rebels their intimidation, incarceration and/or murder is effectively excused.

But even this systematic state repression is not stopping people standing up for their rights, says Bautista.

“We say more oppression breeds stronger resistance. Surely the government and corporations will continue to trample the rights of the indigenous people and other sectors. This will make Indigenous Peoples and ordinary people more united and their collective struggle stronger.”

Holding cultural events, forums and symbolic actions along the way, the recent Lakbayan paid testimony to this theory, as people voted with their feet and raised their voices for justice.

*The report,

Kalibutan: Stories and lessons from the Filipino people’s struggle for the environment, is not yet available online. Visit

Kalikasan PNE’s website to make inquiries and find out more.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 18, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Male Supremacy

by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

“The coercive sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada is genocide proper,” Dr. Karen Stote, professor at Wilfrid Laurier University and author of An Act of Genocide: Colonialism and Sterilization of Aboriginal Women, asserted in a statement to Intercontinental Cry (IC) . Her distinction alludes to the alternative phrasing of ‘cultural genocide’, a semantic preferred by judges, policy makers and other Canadian officials when referencing the plight of Canada’s First Nations.

Stote elaborated that, “…imposing measures to prevent births within a group, when done to undermine the ability of a group to continue to exist, is an act of genocide”. The crime is fully realized “…when [this] coercive sterilization is understood within the larger context of colonialism, as one of many policies/practices imposed on Indigenous peoples that allows the increasing encroachment of Indigenous lands and the reduction of the number of those to whom the federal government has obligations.”

Dr. Kim Anderson, Cree/Métis writer and fellow Wilfrid Laurier professor who specializes in community engaged research in Indigenous communities, supported Dr. Stote’s statement in a phone conversation with IC. “Genocide is the term for [these] systematic strategies. The ultimate end of sterilization is that people are unable to have children and that’s genocide.”

Anderson spoke of the many stories emerging from inside her own personal network of First Nations women today, stories detailing events that took place in Canada as recently as the 1960’s and 1970’s. She went on to contextualize them in reference to a larger, more compounded strategy of genocide on Canada’s First Nations’ families. Rather systematic in approach, attacks against Indigenous family structure and even more specifically, “Indigenous mothering,” have been methodically inflicted going back to first contact. Anderson painted a picture of deep sociocultural wounds from strategic attacks that pierced the most sacred parts of Indigenous life; she described how this frightening history of oppression and abuse made the sterilization era all the more traumatic, in the context of Canada’s greater colonial grand strategy.

A universal legal definition of genocide was outlined in Articles II and III of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide in 1948. According to Article II, the two main elements of genocide are the “mental” and the “physical.” The mental element considers the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.”

The physical element is itemized into five parts: killing members of the aforementioned group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to group members of the aforementioned group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to group members; “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;” “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;” and, “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

These criteria are what Stote refers to when she describes Canada’s handling of its First Nations residents as “genocide proper.” Perhaps a more palatable term to some, cultural genocide has made its way into the larger conversation; its presence there nuanced in a manner that is alternately valuable and distracting.

The terminology of “cultural genocide” is currently used by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a description of Canada’s policies of forced removal and residential schools. In relation to this – and to how much work really does still need to be done to address Canada’s colonial legacy – Anderson was quick to point out a disturbing statistic: there are more First Nations children in the Canadian welfare system now, than were removed to residential schools in the previous era.

Though care must be taken to prevent a battle of semantics from overshadowing these very real and very current issues, there are times when these nuances do matter; even more if they play host to evasion strategies of the hegemonic variety. One of the themes Stote explores in her book is Canada’s role and responsibility – in collusion with other hegemonic, western interests operating at the “UN level” – for the deletion of the article on ‘cultural genocide’ from the 1948 Genocide Convention.

To be clear, Canada actually went as far as threatening to opt out of the entire Genocide Convention if it was included, and was a direct force in the collective opposition that culminated in its removal. Interestingly enough, the measure was supported by the entire Soviet Bloc, while its critics – other than Canada – included the U.S. and most of Western Europe. There were two notable environmental factors contextualizing this sequence of events.

First of all, these circumstances were unfolding in the wake of Hitler’s genocide in Germany; and protections geared specifically at “culture” were presented as superficial in comparison. Secondly, it was all taking place on the cusp of the McCarthy era. It is conceivable that western interests were preemptively protecting other systematic strategies that were being developed – and executed – to target communist, or otherwise political groups, from appearing on the radar of Convention upholders. In any event, the terminology was omitted and with it, the legitimacy of ‘cultural genocide’ under international law. The terminology was revived in 2007 as part of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but was again ultimately excluded in favor of the more succinct expression of “genocide.”

The practices of coerced and forced sterilizations of Indigenous women – and men – must also be understood in the context of both what appears to be this large scale appeal for genocidal impunity, and as well within the violations of basic consent. The American Bar Association outlines a complex set of standards regarding a ward of the system’s ability to give consent in terms of biomedical practices and research. Indigenous peoples in some contexts – trapped in the cyclical patterns of settler violence and imperialistic intrusion upon their lives and culture – especially historically, were definitively unable to give legal consent, even when consent was sought – be it under the most pretentious of terms considering Indigenous peoples were veritable prisoners of war at this point in Canada’s history. Accordingly, an examination of historical documents by Stote revealed “problems: such as a lack of interpreters, … a lack of informed consent, [or] consent forms not being translated into the languages spoken by Indigenous peoples.”

The extent to which Canada was coloring outside the ethical lines with their practices of forced sterilization is further realized in terms of another case in point. Stote related that,

The first high dose birth control pill was being prescribed in Indigenous communities, 1964-1965 at least, before contraceptives were legalized for these purposes – in 1969 – with the intent to reduce the birth rate, and to “reduce the size of the homes the federal government would need to provide.

Considering the Catholic Church’s position on birth control, it might be assumed that their own activity in relation to Canada’s First Nations during this period would steer far and wide from the government’s unholy interventionism. It is therefore especially confusing that they actually worked in collusion with the Canadian government in terms of these methodical strategies to wipe Canada’s First Nations off the face of the planet. This unholy alliance is perhaps most evident in Canada’s long-running policy of forcibly removing Indigenous children from their homes and families, and imprisoning them in residential Christian schools funded by the state. As detailed above, this practice stands on its own as a violation of the Geneva Convention, even after the phrasing “cultural genocide” had been struck from the official document.

After a six year investigation, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that:

The Canadian government pursued this policy of cultural genocide because it wished to divest itself of its legal and financial obligations to Aboriginal people and gain control over their lands and resources. If every Aboriginal person had been ‘absorbed into the body politic’, there would be no reserves, no treaties and no Aboriginal rights.

During a recent trip to Bolivia, Pope Francis issued an apology for the “sins” the Catholic Church committed against the Indigenous of Latin America. Members of Canada’s First Nations would undoubtedly be well served by a similar statement from the (if ambivalently) human rights-oriented Pope. Canadian First Nations organizers were disappointed that former Canadian Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, did not issue a more direct appeal for an apology for the Church’s role in the residential schools when he met with the Pope recently. Assembly of First Nations Chief Perry Bellegarde strongly lamented that move (or lack of one) citing at the time:

Today would have been a powerful and appropriate day to issue that invitation and it would help survivors in their healing journey.

Enter in Justin Trudeau, Canada’s newly elected Prime Minister and Leader of the Liberal Party, who quickly responded to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s release of its final report detailing Canada’s history of residential schools on December 15, 2015. The report documents a horrific legacy of physical and sexual abuse that culminated in an official death toll of 3,200 — though Commission chairman, Justice Murray Sinclair, estimates the actual number to be much higher.Trudeau’s comments — themselves a potential harbinger of a long awaited policy pivot — came after he met with leaders from 5 First Nations communities in Ottawa on December 16th.

To bring the discussion back to coerced and forced sterilization, it is important to note that these atrocities were certainly not limited to Canada. These ethical anomalies are well documented to have occurred in many other nation states as well, including the United States of America.

In 2000, the American Indian Quarterly journal published an article entitled, “The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women.” Researchers concluded their assessment with encouraging news regarding more recent trends concerning Native autonomy in health care practices, but laced any implied optimism with a warning:

While the sterilizations that occurred in the 1960’s and 1970’s harmed Native Americans, Indian participation in their own health care since 1976 has strengthened their tribal communities. Sterilization abuse has not been reported recently on the scale that occurred during the 1970’s, but the possibility still exists for it to occur.

To punctuate that ultimately prophetic statement is a much more recent case from Peru, in which around 350,000 women – the majority of whom were Indigenous Quechua, Aymara, Shipiba, or Ashaninkas – were coercively sterilized by a government health program under the administration of former President Alberto Fujimori. (Fujimori was later sentenced to 25 years in prison for grave human rights violations not directly related to sterilizations.)

The issue of consent loomed large in Peru as well. Sometimes the procedures were done completely in secret after childbirth, and sometimes the only form of consent was a waiver signed by a relative (disturbing, from a few angles, given the language barriers.) There were a number of factors that disabled proper consent protocol, and likewise a number of negative impacts women experienced in the aftermath.

Alejandra Ballón, who has written a book about the procedures in Peru under Fujimoto, noted that, “The women lost their strength and could no longer work as farmers, but also many were abandoned by their male partners, and forced to immigrate to the cities.” In November of 2015, a mobilization of about 80 Peruvian women – victims of these practices of forced sterilizations between 1996 and 2000 – took to the streets demanding justice.

It’s impossible to know if there are similar accounts of impact on the victims of forced sterilizations in Canada, because the necessary research has not been carried out. According to Anderson, this is what makes Stote’s ongoing work so important. She also points to the need to collect the stories of Canada’s First Nation eugenics-era survivors, while they are still alive. She may even take on the latter task herself, having had a dream about it.

Anderson further contextualized Canada’s history of sterilizing its First Nations women as being spawned from this broader eugenics movement that was born out of the writings of Francis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin, who coined the term “eugenics” in 1883 . It was a movement, she points out, that Indigenous peoples were constantly targeted by.

Seven years before Nazi Germany passed the Nuremburg Race Laws that outlawed German Jews from having sexual or marital relations with anyone of German or mixed ancestry, Alberta passed “The Sexual Sterilization Act” in 1928. The legislation outlined the conditions and procedures for sterilizing individuals who were deemed to have “undesirable traits.” Five years later, in 1933, British Columbia passed a law of its own, “An Act Respecting Sexual Sterilization.” Like its eastern counterpart, British Columbia’s legislation outlined the who, the where, and the how in regards to sterilization of those who were considered wards of the state and possessed some sort of “undesirable trait.”

One has to wonder, as professor and Lakota-American, Dr. Lehman Brightman did during his historic speech at the end of “The Long Walk” in 1978 (which followed the famous occupation of Alcatraz in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s) if this “trait” was in fact resource-rich land and unconquered territory. Brightman proclaimed, regarding Natives in the United States at that time:

We won’t have any need for reservations if we don’t stop the sterilization of our youth, and of our women, and of our men.

Even amidst the height of these draconian practices, most of the time the need for actual consent was at least legally recognized. In other words, it is possible that B.C. was breaking its own laws in regards to methods used to forcibly sterilize Canadian First Nations women.

Arizona State professor, Dr. Myla Vicenti Carpio, published an article in 2004 called, “The Lost Generation: American Indian Women and Sterilization Abuse,” in which she charges that:

The United States filters monies through agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Ford Foundation for population control programs. These agencies were responsible for the sterilization of men and women in regions such as Puerto Rico, Brazil, Guatemala, Africa, and Panama.

Exact figures are unattainable in terms of just how many Native Americans were sterilized in the U.S. during the 1970’s. Brightman, who devoted much of his life’s work to the issue, put his educated guess at about 40% of all Native American women alive at that time, and 10% of Native men. Brightman figured that the total number of Native women sterilized during that decade was between 60,000 and 70,000, and has labeled it “criminal negligence and criminal genocide.” Citing the language issues, among other issues related to consent, Brightman asserted: “They’ve sterilized all of our women by trickery, by fraud and by crook. They’ve asked them to sign consent forms that they couldn’t read, in English; they’ve sterilized them without telling them about it; and they’ve sterilized them by lying to them and telling them the operation was reversible.”

Documented survivor counts are accumulating among Canada’s First Nations community as well. According to Stote: “We know (according to other researchers, i.e., Christian, 1974 and Grekul, 2004) Indigenous peoples were targeted under Alberta’s eugenic legislation (1928-1972), making up 6-8% of those sterilized overall, despite only being about 3% of the population; although in later years (1969-1972), they made up over 25% of those sterilized.”

Stote’s own research – reviewing the first of three federal files she searched in all – uncovered sterilizations performed on Indigenous women at 14 different federally operated Indian Hospitals across Canada. Another set documented sterilizations on First Nations women from 32 different northern settlements; and, a third set detailed the experiences of women from the Baffin, Keewatin, Mackenzie, and Inuvik zones.

Unfortunately for Canada’s First Nations, neither sterilizations nor history are easily reversed; and as such, neither are the sustained impacts of the genocide of eugenics. One of the surest ways to make sure these tragedies of recent history are not repeated in the present or future, is to heed the call to aggregate and document the collective and individual stories and memories of Canada’s First Nations women who are still living with the effects.

In terms of relevance in modernity for Canada’s First Nations, Stote explained to IC that:

I think the discourse of blaming individuals for social problems, for the poverty conditions in which they live, and for having children they “can’t afford” is still very much with us. It is more cost effective to blame individuals, and to view them (or their reproduction) as the cause of their situation rather than examine the larger political, economic and social system in place that creates poverty, social problems, etc. And for Indigenous women in Canada, but many other places as well, it is conditions of colonialism and the failure of the federal government (settler population in general) to uphold obligations to Indigenous peoples that is creating the marginalized status and poverty conditions in which Indigenous peoples are forced to live. These conditions of colonialism are ongoing.

These very issues have come to a head recently as yet another First Nations woman has come forward with an account of a recent sterilization that occurred outside of the boundaries of proper consent. Melika Popp, a Saskatoon woman who was sterilized after the delivery of her first child, was assured the process was reversible and shared, “I felt very targeted. It was under duress. I was definitely hormonal at that time.”

For more recent survivors like Popp, the struggle to come to terms with ongoing impacts has just begun. Others have been carrying these burdens for decades without a platform on which to speak out. In terms of what it will take to jumpstart the healing process for all, thus allowing Canada’s victims, their families, and their communities to move forward, Anderson had some words:

Story-telling and testimonial can be a healing process for people, to [realize] that their voice and their story is heard. In general, North Americans are really uninformed about Indigenous history on the continent and the brutality that was involved, and maybe are resistant to learning about that because it triggers all sorts of other feelings, like white guilt, but the only way to go forward is to work with the truth. It is also important to talk about it within the framework of assessing the family breakdown. Family is so important to Indigenous cultures…the attack therefore has been so devastating…recognizing and naming this is a significant form of healing.

According to recent reports, a surprising leader in the race to make amends on issues of forced and coerced sterilizations is the southeastern state of North Carolina. North Carolina announced their intentions to be the first state to financially compensate victims of its particularly aggressive sterilization programs, in early 2012. Estimates cite that North Carolina alone sterilized 7,600 people between 1929 and 1974. Out of 768 claims made, 220 living victims were designated to receive checks of $20,000 each. Under the compensation policy, the sterilizations had to have taken place under the state’s Eugenics Board; unfortunately, various judges and social service workers were apparently “greenlighting” them off the books as well.

Stote also weighed in with some insight about how Canadians can move forward as a whole on the trajectory towards justice and healing.

On an individual basis, I think those on whom these injustices were perpetrated should be asked about what needs to be done. Gathering the details of what happened, when, on whom, and under what conditions, would be made much easier if there was an honest and forthcoming attempt to, at the very least, acknowledge [that] this type of thing happened to Indigenous peoples in Canada. More broadly, I have consistently heard and seen Indigenous peoples struggling for the right to self-determination as peoples, to have their ways of life respected, their bodies respected, and to have settlers uphold their end of the original responsibilities and relationships that were laid out between them and Indigenous peoples. So, I see that as a great place to start. I think this will require Canadians to really take the initiative in learning our history, and to challenge those we have been allowing to make decisions on our behalf. This will ultimately need to include a restructuring of our social, political and economic life in Canada.

Keri Cheechoo, a Cree woman from the community of Long Lake #58 First Nation, and a PhD. Candidate at the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa, offered some final thoughts in a statement to IC:

As peculiar as it sounds, I awoke at about three in the morning with two words swirling in my mind: forced sterilizations. I scribbled them down on the back of a receipt and went back to sleep. The next day I began reading and engaging in dialogue with those both close to me, and in the Academy, and I began to realize that the scope of forced or coerced sterilizations in Indigenous women is both appallingly enormous and disturbingly concealed.

It is my opinion that forced or coerced sterilization is an act of violence on Indigenous women. The colonial agenda of genocide that was endorsed in the form of forced or coerced sterilization of Indigenous women contributed directly to the colonization of the land. Indigenous women are conduits, we are connected to the land in an esoteric way, and a permanent loss of reproduction and reproduction rights directly impacts our capacity to inhabit or to disrupt attempts at land theft.

I think it is important that the Canadian federal government endorse the 41st Call to Action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Report, which indicates: “We call upon the federal government, in consultation with Aboriginal organizations, to appoint a public inquiry into the causes of, and remedies for, the disproportionate victimization of Aboriginal women and girls. The inquiry’s mandate would include: i. Investigation into missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls; [and] ii. Links to the intergenerational legacy of residential schools.” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action, 2015, p. 4)

It is my growing belief that it is vital that this piece of hidden Canadian history be exposed, and that mainstream Canada become educated on the historical trauma of forced or coerced sterilizations on Indigenous women.

Author’s note: Special thanks to Dr. Karen Stote, Dr. Kim Anderson, Quanah Parker Brightman, and Keri Cheechoo for their vital input and support.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 17, 2015 | Worker Exploitation, Worker Solidarity

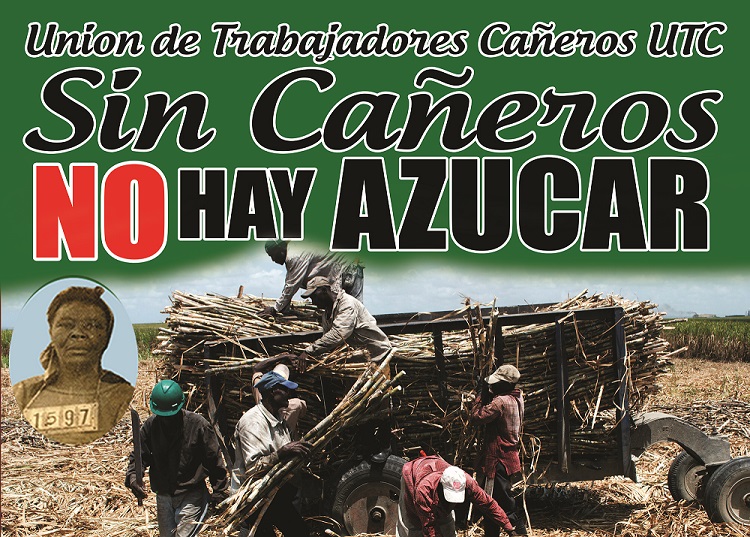

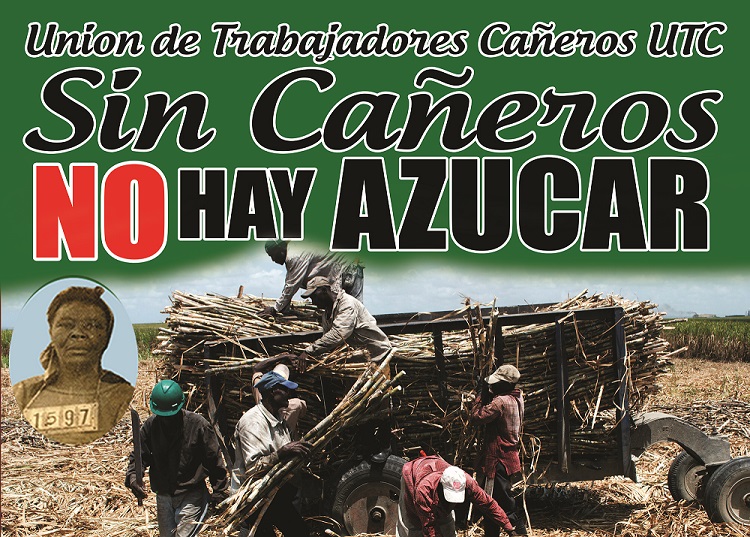

By One Struggle

On what I earn, I can’t afford shoes… We are poor, poor, poor. There are days we go to bed without food. – Batey worker from the film, “The Price of Sugar”

In the sugar plantations or bateyes of Dominican Republic, cane cutters often work barefoot. They can’t afford shoes. They can barely afford food, for that matter, despite the fact that they often work a minimum of 12 hours a day, doing the back-breaking work of cutting sugar cane by hand.

On the other side of the border that divides Hispaniola, Haitian garment workers in Port Au Prince recently blockaded a Korean factory because of bounced paychecks. For years, Haitian garment workers have been fighting wage theft and to be paid the inadequate legal minimum wage – still not enough to live off of.

Whatever the product is – the pair of pants, the t-shirt – we are the ones producing it. We labor hard, and don’t get paid. – Haitian garment worker of SOTA in Port Au Prince

This week Unión De Trabajadores Cañeros De Los Bateyes (Union of the Bateyes of Sugarcane Workers) and Sendika Ouvriye Takstil ak Abiman (SOTA) (Union of Textile and Garment Workers) will meet to discuss their common struggles against exploitation.

Specifically, they are meeting about recent actions of the DR government to strip people of Haitian descent of their citizenship. This has mostly affected the poor – cane cutters, street vendors, and service laborers. In bringing attention and their perspective to this struggle, the groups’ intentions are to put down false divisions of racism and nationalism, with the goal of working together against their common enemy – the Haitian and Dominican ruling classes.

SOTA is affiliated with the autonomous workers’ organization, Batay Ouvriye (BO) (Workers Fight), which will host a series of meetings, a press conference, and direct action in Port Au Prince.

According to one of the event organizers, “They will be three Haitian cane workers, one Dominican cane worker and the coordinator of the union. The presence of the Dominican cane worker is to deny the nationalist option and to put the class situation in concrete relief, in contrast to the bourgeois organizations here who pretend to defend their ‘compatriots.’”

There is a long history of animosity between Haiti and Dominican Republic. Both nationalism and racism are deep rooted. The DR won its independence, not from European colonialists, but from Haiti. Since then, Haitians living in the DR have faced discrimination, and thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent were massacred under Dominican dictator, Rafael Trujillo.

In 2013, the Dominican Supreme Court retroactively withdrew citizenship from anyone born in the DR to undocumented immigrants, with the provision that persons who submitted the proper documentation could apply for legal residency. The deadline for this application was summer 2015. However, many who submitted this paperwork, along with hundreds of dollars in fees, never received any notice or proper documentation from the government. Thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent left the DR, or were rounded up and dropped at the Haitian/Dominican border, often without being able to gather their belongings or to alert their families.

So now, there are hundreds of thousands of people rendered stateless, living in temporary shanty-towns along the border. They’ve been told that if they get documentation proving their country of origin from the Haitian government, then they can apply for Dominican citizenship or work visas. In fact, the Haitian government was paid by the Dominican government to facilitate this process, but Haitians living in limbo on the border have seen no results from this transaction.

Another issue affecting cane workers and low-wage laborers is that for years many paid into social security in the DR. Once they stopped working, they apply for their pensions, submitting the required paperwork to DR government and received nothing. Or, if they’ve been deported, they have no means of claiming their pension either.

This situation is not just about racism or nationalism. It is an issue of the ruling classes of both countries exploiting and stealing from the poor and working class. This summer, many demonstrations were held, especially in New York and Miami, with calls for travel boycotts against the DR and urgent appeals to avert a humanitarian crisis. Most of these demands have been voiced from people outside of the DR/Haiti, or removed from the exploitation of the bateyes and the temporary shanty-towns.

The aim with this series of meetings between workers from both countries is to bring attention to calls and demands led by the workers and people directly affected by these struggles. These are the people whose demands should be amplified, and calls for action should be followed.

Here in the U.S. we use Dominican sugar in our coffee every day. Our clothing is made in sweatshops, often sewn in Haiti (thanks to HELP and HOPE Acts). Capitalism and imperialism give us no choice, no say in how goods are produced. Our sugar and our clothing are the results of wage theft and a politic of misery for the working class in dominated countries. Boycotts and conscious consumerism pretend that with our purchasing, exploitation can be ameliorated. In reality, it is merely shifted to another part of the world. We need to understand the dynamics of capitalism/imperialism, its inherent exploitation, and we must address these issues from the interests of the working class. Who better to lead this effort than the workers themselves?

Read more at One Struggle