by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 16, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

By Stephany Seay / Buffalo Field Campaign

Winter is setting in. Snow is accumulating, and with the snow comes migration. The deep snows of Yellowstone’s high plateau drive elk, buffalo, deer, moose, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep down to lower elevations. Unfortunately for hundreds of wild buffalo, this migration can mean the end of their lives; not because food is hard to find — winter is extremely challenging, but they are well-equipped to use their huge heads to “crater” through snow to get to the life-giving grasses below — but because the lower-elevation grasslands they seek are located in Montana where they enter a deadly conflict zone put in place by livestock interests.

As the buffalo begin their winter migration, BFC volunteers begin their own, returning to camp from all points of the compass to stand with the buffalo. The early snowfall necessitates the opening of our Gardiner camp along the Park’s north boundary, which we will do this Saturday; it’s been quite a few years since we opened up Gardiner camp this early. Patrols are preparing for another difficult season of documenting all actions made against the buffalo, monitoring their migration, and sharing our stories and first-hand experiences in an effort to end this war against wild buffalo. Will you join us?

In the Hebgen Basin, west of Yellowstone National Park, at least ten buffalo have already been killed by treaty hunters, and Montana’s state hunt will begin on Saturday, with other treaty hunts to follow. In addition to six months of combined state and treaty hunts, Yellowstone National Park, the Montana Department of Livestock, and even some tribal entities, are aiming to capture and kill hundreds more buffalo. Through hunting and slaughter, the Interagency Bison Management Plan agencies intend to kill nearly 1,000 Yellowstone buffalo. There are fewer than 5,000 left, and the Yellowstone population — the world’s most important — is made up of America’s last continuously wild herds. Ecologically extinct throughout their native range, and not yet federally protected, bison are endangered. In 2014 we filed a petition with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to protect wild bison under the Endangered Species Act, and sometime this fall the USFWS is expected to issue their finding. If they issue a negative finding, rejecting ESA protection — and no thanks to politics, we expect they will — we are prepared to take the next step.

Come stand with the buffalo if you can, help keep us on the front lines, and continue to spread the word to save these sacred herds.

Wild is the Way ~ Roam Free!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 11, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

Elvira Nascimento

Cyntia Beltrão reports from Brazil on what may be the country’s worst environmental disaster ever, at the Samarco open pit project jointly owned by Vale and BHP Billiton:

Last Thursday, November 5th, two dams containing mine tailings and waste from iron ore mining burst, burying the small historic town of Bento Rodrigues, district of Mariana, Minas Gerais state. The village, founded by miners, used to gain its sustenance from family farming and from labor at cooperatives. For many years, the people successfully resisted efforts to expel them by the all-powerful mining company Vale (NYSE: VALE, formerly Vale do Rio Doce, after the same river now affected by the disaster). Now their land is covered in mud, with the full scale of the death toll and environmental impacts still unknown.

Officially there are almost thirty dead, including small children, with several still missing. The press and the government hide the true numbers. Independent journalists say that the number of victims is much larger.

The environmental damage is devastating. The mud formed by iron ore and silica slurry spread over 410 miles. It reached one of the largest Brazilian rivers, the Rio Doce (“Sweet River”), at the center of our fifth largest watershed. The Doce River already suffers from pollution, silting of margins, cattle grazing in the basin land, and several eucalyptus plantations that drain the land. This year Southeastern Brazil, a region with a normally mild climate, endured a devastating drought. Authorities imposed water rationing on several major cities. Meanwhile, miners contaminate ground water and exploit lands rich in springs. The Doce River, once great and powerful, is now almost dry, even in its estuary. The mud of mining waste further injures the life of the river.

We do not know if the mud is contaminated by mercury and arsenic. Samarco / Vale says it isn’t, but we know that its components, iron ore and silica, will form a cement in the already dying river. This “cement” will change the riverbed permanently, covering the natural bed and artificially leveling its structure. The mud is sterile, and nothing will grow where it was deposited. A fish kill is already occuring. We do not know the full extent of impacts on river life or for those who depend on the river’s waters.

Soon the dirty mud will reach the sea, where it will cause further damage, to the important Rio Doce estuary and to the ocean.

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 9, 2015 | Male Supremacy, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis, Women & Radical Feminism

Artwork by Summer-Rain Bentham, Vancouver Rape Relief and Women’s Shelter

PART ONE: First steps for an effective fight-back

In the face of a worldwide crisis of male violence against women, radical feminists are preparing for a grassroots resurgence. This is the first in a series looking at effective strategies to take back women’s space and challenge male violence. Part Two is here.

By Tara Prema / Gender is War

Western patriarchy arrived on the Pacific Coast of North America less than two hundred years ago. In some places, it hasn’t completely eradicated traditional cultures. These notes come from unceded indigenous land on the frontlines of the white male supremacist invasion.

Here, as elsewhere, our enemies publicly intimidate women activists with impunity. We face death threats, violence, stalking, and censorship from both the right and the left. This war of words is part of the escalating global war on women.

Brutality is everywhere we look. In Canada, men have murdered or “disappeared” over twelve hundred indigenous women in the past decade. Currently, the rate of male-on-female homicide is rising sharply – in some communities, it has doubled in a few years. Rape, assault, and sex trafficking have reached an all-time high and they are still growing. The victims are women and girls of all ages, races, nationalities, and social classes; however, males inflict much greater violence on indigenous women and women of color.

At the same time, women-centered spaces are disappearing and our feminist networks are divided by infighting. Male supremacists of all stripes aim their rage at targets of opportunity. The backlash is here and it’s worse than expected.

It’s time for emergency measures. That means strategic decisions about which battles to fight, against whom, and on whose turf. When the goal is to stop men from killing women, we must teach and learn how to fight back to protect ourselves and each other. In order to do that, we must join together for mutual aid and avoid becoming casualties ourselves.

Most of us are traumatized. Part of healing involves getting to the point of responding to threats effectively and learning to deal with fear, anger, and helplessness in a healthy way – by taking back our power.

Strategic Action: an introduction

Our position is one of asymmetric struggle against entrenched systems of patriarchal violence and domination that go back thousands of years in the West. Our strategy is like a guerrilla resistance movement against an occupying force that seems unbeatable – at least at first.

Success in asymmetric conflicts lies in making sure we are prepared for effective, sustainable action that moves toward the goals we’ve chosen. Campaigns that lead nowhere drain our energy and expose us to our enemies. Successful symbolic actions are excellent for boosting morale and recruiting but they are not ends in themselves. The outcome of each action doesn’t have to be large, but the goal should be.

The most useful analysis of effective strategies in asymmetric conflicts comes from the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. DGR divides effective actions into three categories:

- shaping actions bring about the conditions where resistance is possible

- sustaining actions allow resistance to begin and continue

- decisive actions are capable of bringing down patriarchal institutions.

Creating Conditions and Capacity

Like any other human endeavor, whether building a house or planting a field, sustained grassroots action requires certain pre-conditions. For this movement, we must develop the capacity to reach out, organize, and defend ourselves and each other. There are dozens of ways that women around the world are creating the conditions to successfully challenge male domination and hold space for our sisters. For example:

- Women-only groups, gatherings, and discussions about liberation

- Naming the problem and naming the agent (male violence) in our speech and writing

- Anti-violence campaigns as part of healing and trauma recovery (and vice versa)

- Creating affinity groups and mutual aid networks

- Hosting women’s self-defense trainings

- Speaking out in public against male violence when it’s safe to do so

- Speaking privately with our sisters when it’s not

Strategic feminist actions are campaigns with achievable outcomes that lead toward a larger goal.

Networks of resistance are essential for our survival. Many of our networks are secret out of necessity. In the past year, we’ve seen radical women take back space by organizing our own conferences, like Radfem Riseup and Radfems Respond. Others are pushing back against censorship by mobilizing en masse, as fans of Meghan Murphy did when her publisher was threatened with boycotts.

When the goal is empowering a generation of women to fight male violence and rape, a crucial tactic is developing those skills — for example, by training women to teach others self-defense and protective strategies as the Warrior Sisters do. We might also consider public demonstrations that women are ready and able to physically fight men and win.

Creating a loud, visible culture of resistance is a longer-term goal that can lead to larger group mobilizations and decisive victories, like local uprisings to expel violent males from our communities. (It wouldn’t be the first time – see the Gulabi gang in India.)

The first task of a strategic activist is to find others who share the same values, in order to sustain our morale and bring ideas to action. When there’s no group nearby, we can travel to the nearest get-together, find or create radical feminist spaces online, and start our own groups.

- Most groups start with just a few people. Talk to strong female friends and acquaintances to find those who share the same goals and values.

- Launch a petition – either online or on paper. It can be a demand letter (“Fund women’s shelters!”) or a general call for support (“Yes I support organizing against male violence in my community”). The email addresses you collect become your outreach list.

- Start or join an online discussion forum or a private Facebook group for radical feminists in your region. Reach out, ask for advice, find out what other women are doing or would like to do.

- Call a meeting. The ones who show up are the organizing committee for future events and gatherings. (Make sure to set a time and place for the next meeting.)

- Host an event: a film screening, a book discussion, a street demo, or a radical feminist speaker from out of town. Keep that signup sheet handy.

- Prepare and discuss a basis of unity. Set out goals, guidelines, and responsibilities early on. Make sure there’s agreement on the group’s direction, how to screen new members, and how to end relationships with those who disrupt the group or don’t share its goals.

Often it’s not safe to organize. But we do it anyway – outside of the public eye, anonymously, or under a nom de guerre. Every woman who is publicly feminist has to deal with more than her share of hate. That’s why it’s so important to get together and watch each others’ backs. The goal of our enemies is to isolate and terrorize women in order to neutralize us. Don’t let them win.

- Take safety precautions, like keeping home and work addresses private.

- Follow security culture guidelines.

- Let other organizers know about any threats immediately.

- Post security people at public events.

- Accompany activists who are targeted.

- Inspect incoming packages, email messages, friend requests, and other invitations before opening or responding.

- Block hostile individuals on social media so they can’t see personal details, friends, and family.

- Use security measures (like data backups and two-step verification) on computers, websites, and email.

- Have an emergency plan and a bugout bag for leaving home in a hurry.

- Report credible threats to your group’s security coordinator. Police are often indifferent or abusive, but it may be useful to report the threat in case the target is forced to defend herself.

- Keep event locations secret until hours before, or disclose them only to registered participants.

Male violence has taken the lives of thousands of women while terrorizing millions more. We have choices: We can keep our heads down and hope the violence passes us by. We can spend time and energy on ineffective or counter-productive tactics. Or we can connect our networks and grow a coalition with the power to confront the killers and win.

Remember: Solidarity between women has survived repression for more than a millennium in some parts of the world. Male supremacists have done their worst and we are still here fighting back. Our reality and our wisdom will outlive the dominant culture’s delusions.

Parts Two (published here) and Three of this series will look at strategies for sustaining and decisive actions

We hope other radical feminists find this introduction useful, and we welcome your feedback as we draft the next chapters in this series.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 7, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action

In early October, news emerged that India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change was blocking the implementation of a high-level government panel’s report on tribal rights that recommended the creation of stringent rules to safeguard indigenous people from displacement. Meanwhile, two state governments have begun implementing a much different set of guidelines — issued in August without any interference — that allow the private sector to manage 40 percent of forests for profit at the expense of indigenous forest dwellers. In addition, another ordinance passed this year will permit private corporations to easily acquire land and forests from indigenous communities and carry out ecologically harmful mining. These legislative and policy decisions are usually made without the knowledge of indigenous communities whose lives, livelihoods and ecosystems will be worsened by these irresponsible actions of the government. Hence, indigenous communities in Uttar Pradesh, a northern state and Odisha, in the east, are strengthening their organizing to protect their rivers, lands, forests and hills from “development” that would displace thousands of local residents and destroy the environment.“People from my community and I were beaten, detained or jailed unnecessarily for opposing tree felling in our forests, some years ago,” said Nivada Debi, a feisty 38-year-old woman from the Tharu Adivasi community in Uttar Pradesh. “We visited the police station multiple times for their release. The government did not assist the injured. Despite the police and government indifference, we will fight for our land and environment.”A mother of four children subsisting on the forests, Debi is active in grassroots resistance that started nearly 20 years ago and has grown into the All India Union of Forest Working People, or AIUFWP. The group is made up of many indigenous people who subsist on forests and are collectively protecting forests from poachers and encroachers.

Debi was among hundreds — from the AIUFWP, the allied Save Kanhar Movement and other resistance groups — who traveled to Lucknow in July 2015 for a rally protesting the continued incarceration of their comrades fighting land grabbing in other districts of Uttar Pradesh. Roma Malik, the AIUFWP deputy general secretary, and Sukalo Gond, an Adivasi, which means original inhabitant, were among those arrested on June 30, before they were to address a large public gathering about the illegal land acquisition for the Kanhar dam and the violent repression of its opponents by the state. Another member of AIUFWP, Rajkumari, who prefers to go by her first name, was jailed on April 21, after 39 Adivasis and Dalits, who are considered outside the caste hierarchy, were brutally shot at by the police during a peaceful protest on April 18. The demonstration, which began on April 14 — the birthday of B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian constitution and an icon for many Indians, particularly Dalits — was opposing the construction of a dam across the Kanhar river in the Sonbhadra district of southeastern Uttar Pradesh.

Rajkumari was released toward the end of July while Gond and Malik were freed in September. However, others are still imprisoned on fabricated charges. Courts are delaying hearing their cases or denying them bail.

AIUFWP members, some of whom were previously involved with other local resistance movements, have been actively opposing the construction of the Kanhar dam for years. It would submerge over 10,000 acres of land from more than 110 villages in Uttar Pradesh and the neighboring states of Chattisgarh and Jharkhand, displacing thousands of local people and disrupting their lives and livelihoods. The dam was approved by the Central Water Commission of India in 1976, but was abandoned in 1989 after facing fierce opposition, especially from the local people whose lives and ecosystem would be destroyed by the proposed dam. However, construction resumed in December 2014, violating orders to stop it from the National Green Tribunal — a government body that adjudicates on environmental protection, forest conservation and natural resource disputes. No social impact assessment was done, nor were the necessary environmental or forest clearances — mandated by the Forest Conservation Act — obtained by the state government.

“Since this dam can destroy our survival and also adversely impact the surroundings, we have been opposing its construction and related land acquisition for many years,” said Shobha, a determined 42-year-old Dalit. “On December 23, 2014, the police caned some of our comrades when we were peacefully protesting the revival of building the dam earlier that month. However, the police falsely accused some leaders of our struggle of attacking the sub-divisional magistrate.” Shobha, who also prefers to go only by her first name, is among the vocal leaders of a women’s agricultural laborers union, which has allied with AIUFWP, in the village of Bada.

Around 400 miles from Sonbhadra, in the Kalahandi and Rayagada districts of southern Odisha, live the Dongria Kondhs, an indigenous community of over 8,000 people. They have been fighting tirelessly to protect their sacred mountain, the nearly 5,000-foot high Niyamgiri, from large private corporations — like Vedanta Limited — that are trying to mine bauxite in the area to produce aluminum. Supporters of the Dongria Kondhs were arrested in Delhi on August 9 outside the Reserve Bank of India, as they peacefully highlighted Vedanta’s illegitimate and harmful mining in the Niyamgiri. Vedanta’s mining would violate the Forest Rights Act, which states that indigenous communities are entitled to remain in the forests — and utilize the produce, land and water in the forests — while conserving and protecting them.

“The Niyamgiri symbolizes a parent to our community,” said Sadai Huika, a steadfast 45-year-old Dongria Kondh woman from Tikoripada village. “While the streams that originate from it help our farming, the plants and grass that grows on it feed our cattle and goats. We cannot exist without it and will safeguard it from anyone trying to harm it.”

Huika and people from hundreds of villages near the Niyamgiri are active members of the Niyamgiri Protection Forum, which originated around 2003 to resist attempts by Vedanta to begin mining where the Kondhs live, with the support of the Odisha state government. At every one of the 12 village council meetings with government officers held in 2013 atop the Niyamgari, community members stated that they would not allow mining nearby.

Kumuti Majhi, an elderly Dongria Kondh man and one of the forum’s leaders, is among the few people who have traveled within and outside Odisha to advocate against mining and garner vital support for their struggle. He has met ministers to explain how significant the Niyamgiri is to his community and their reasons for safeguarding it.

By organizing protests locally and with allies around the world — and meetings with Vedanta’s shareholders and empathetic government officials, who the forum has enlightened about the need to protect the Niyamgiri — the group has stalled the mining.

“We know that extracting bauxite from the Niyamgiri will pollute our environment and also affect all living beings here,” Majhi said. “Hence, we will stop anyone coming to plunder the Niyamgiri, despite police harassment and false charges against us and our families.”

Pushpa Achanta is a Bangalore-based freelance journalist, blogger and writer on development and human interest issues. She is the lead author of a book titled Ripples: The Right to Water and Sanitation for Whom, published in July 2013 by the Indian Social Institute in Bangalore. Her articles have appeared in collections of essays and features on different subjects. She also enjoys penning verse, taking nature photography and mentoring youth.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 6, 2015 | Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the second in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the first part.

- Gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014.

- Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of local communities.

- With gold prices continuing to rise overall despite recent drops and Suriname’s political economy deeply entrenched in resource extraction, conservationists worry mining expansion will be hard to stop.

High gold prices combined with lax land use regulations have led to an explosion in mining in Suriname. A recent report by the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) finds that gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014, and is threatening the health and ways of life of many communities in the region.

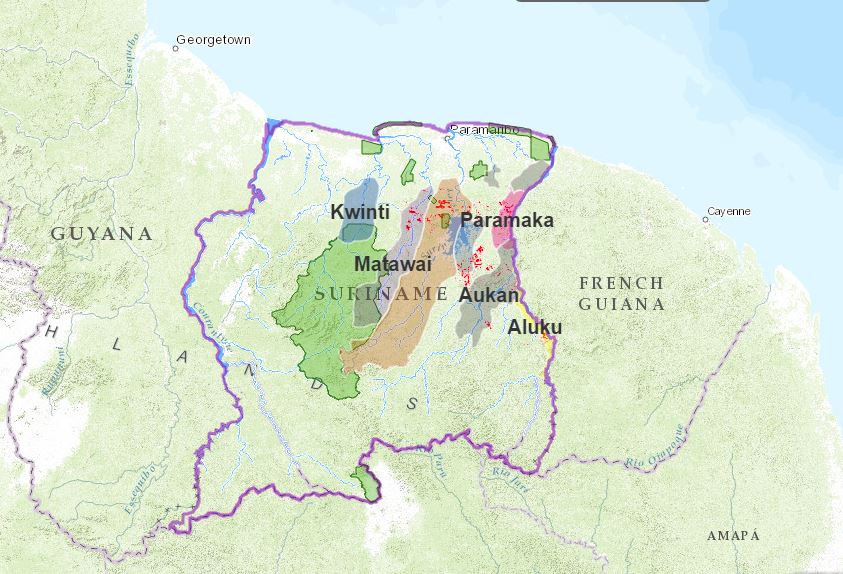

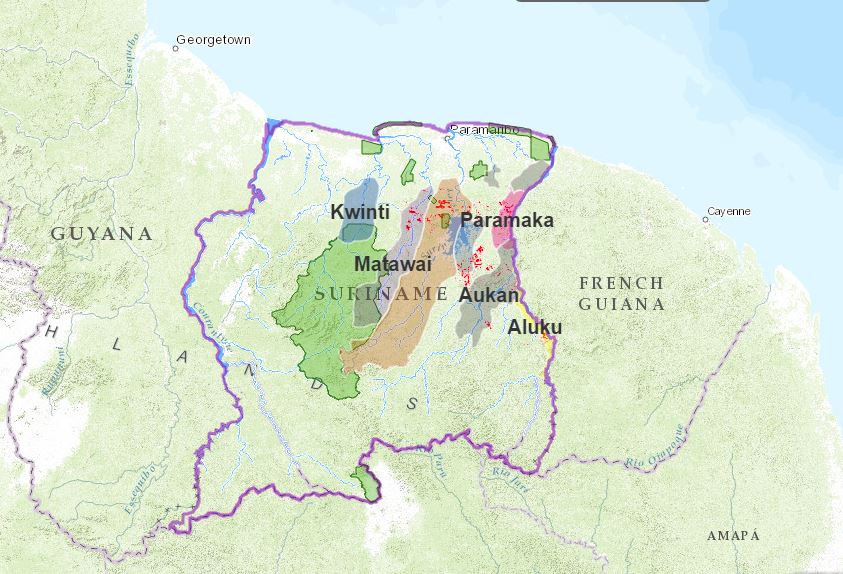

Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of the Maroons – descendants of formerly enslaved people of African heritage who escaped from plantations during Dutch colonial rule and established thriving communities in the country’s hinterlands after successfully fighting for their freedom.

Suriname’s six main Maroon communities all reside along rivers leading upstream deep into the rainforest, the report says. The majority of Maroons live in the central-eastern part of the country – where the mineral-rich Greenstone Belt and gold deposits are located. Through statistical analysis, the ACT discovered that encroachment of gold mining is significantly more severe within Maroon territories than outside of them. The team writes that only one Maroon community far from the Greenstone Belt is currently not seeing any gold mining on their lands.

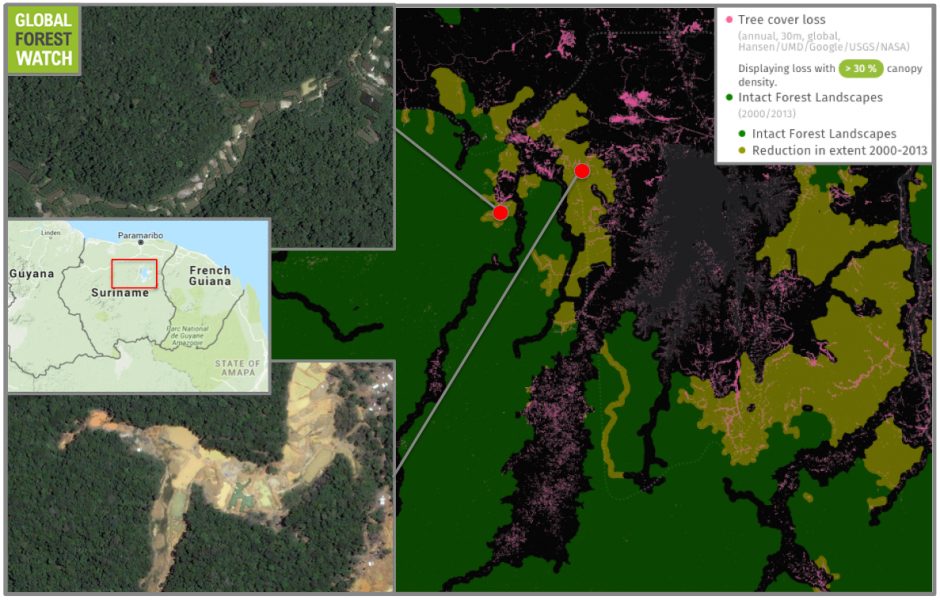

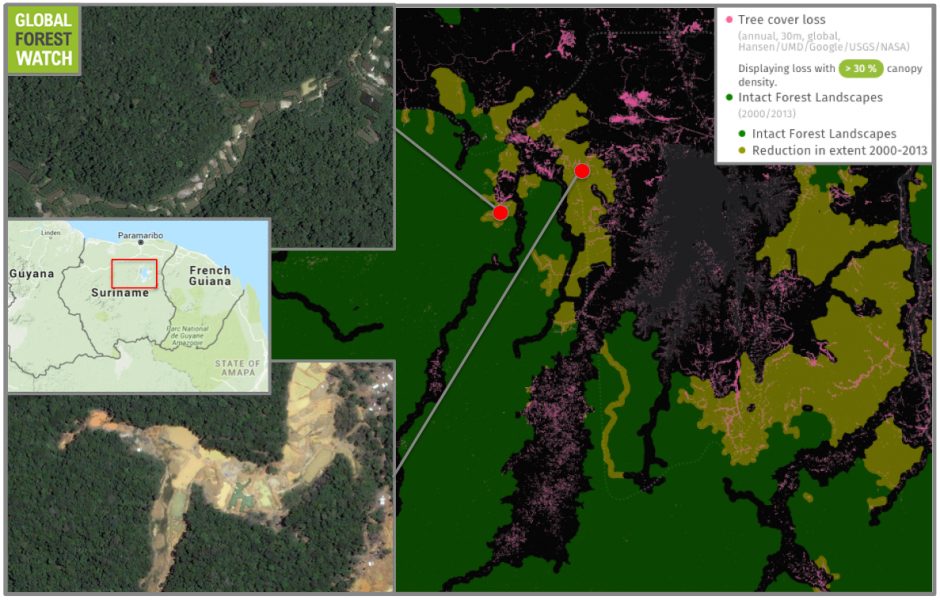

Suriname boasts large tracts of intact forest landscapes (IFLs), which are continuous, undisturbed areas of primary forest. However, Global Forest Watch shows significant IFL degradation, with the country experiencing nearly 17,000 hectares of tree cover loss in its IFLs between 2001 and 2014. Much of this is happening in areas with gold mining activity.

Mining extent (red) in Maroon-occupied areas. Image courtesy of the ACT.

For some Maroon groups, small-scale gold mining has become a major component of their landscape and their daily lives. In many of their villages – particularly in Paramaka, Aukan and Matawai communities – villagers have become economically dependent on gold mining. Anthropologist Marieke Heemskerk has shown that in some Maroon villages, 70 to 80 percent of households get their regular income from family members working in gold mines. Villagers with informal concessions are able to collect fees from the garimpeiros – the Brazilian miners – and others working on their lands, and some have become quite wealthy as a result.

The Matawai Maroons who live along the Saramacca River in central Suriname, are among the smallest of the Maroon communities in terms of population. Their territory covers about 560,000 hectares and many of their villages are among the most remote and least-known in the country. Consequently, the Saramacca River, the surrounding ecosystem and the villages themselves remained relatively quiet and peaceful while other Maroon communities were contending with the pressures of inland colonization and resource extraction.

The northern portion of the Matawai territory, however, is located in the reaches of the Greenstone Belt. Being close to populated settlements, they are easily accessible via roads. This has allowed rapid expansion, with a number of the northern Matawai villages located at ground-zero for Suriname gold mining.

“According to our calculations derived from deforestation data, 81.51% of all deforestation in the Matawai territory is due to gold mining,” the report says.

Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.

Four Matawai villages – Nyun Jakobkondre, Balen, Misalibi, and Bilawatra have been particularly impacted by the large gold mines that encircle them. In fact, much of the small-scale mining in the region is done by Maroons themselves, which is threatening their traditional livelihoods of hunting, fishing, woodworking, etc.

“As more Maroons in the Matawai community and elsewhere are becoming dependent on partaking in mining for household income, these and other local practices are eroding,” said Rudo Kemper, GIS and Web Development Coordinator for the ACT. “Many of the Matawai youth in particular are no longer as interested in traditional activities, as they know that there are lucrative profits to be made working in the mines.”

To make matters worse, mining activities has polluted waterways with mercury, which is used to separate the gold ore from sediment. Mercury can act as a neurotoxin, and has contaminated river fish, which are no longer safe to eat. Arable land is also threatened. According to Kemper, “in areas like Nyun Jakobkondre, the gold mining is taking place so close to the village that fertile land for cultivation is becoming scarcer.”

Nieuw Koffiekamp, a village settled by Maroons after it was relocated because of floods, is now located right in the middle of one of the most prosperous and mineral-rich veins of the Greenstone Belt. Known as Gros Rosebel, the area was one of the first industrial mining concessions in Suriname. Villagers have been using the area for sustainable livelihoods for generations, but the ACT report alleges they were neither consulted with nor informed about the concession. Years later, the government set up a task force dedicated to relocating the village once more. The village continues to fight for its existence, despite being literally fenced in by gold mining activity. Community members argue they have the right to extract resources from their own land and thus participate in small-scale gold mining.

Even Brownsberg Nature Park, a 14,000-hectare reserve and popular tourist destination, hasn’t been spared from the clutches of mining. From early on, gold miners have been active within its boundaries, where an estimated 924 hectares of primary forest has been lost to gold mining. In 2012, deforestation in the park reached an all-time high, with 200 hectares of forest cleared. In that same year, public awareness about mining inside Brownsberg began increasing when WWF–Guianas published a report with aerial photography of the damage to the park. “Since then,” Kemper said, “the rates of small-scale mining in the boundaries of the park have dropped somewhat, although deforestation caused by mining in the park [continues] to expand.”

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining boom threatens communities in Suriname

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 4, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the first in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the second part.

- High gold prices are leading to an increase in mining activity.

- Mining activities threaten Suriname’s primary forests, some of the most-intact in South America.

- Mercury released from the mining process can be toxic, and is showing up in human population centers far downstream.

Record high gold prices over much of the past decade have triggered a massive gold rush across much of the Amazon basin, resulting in the destruction of thousands of hectares of pristine rainforest and the contamination of major rivers with toxic heavy metals. A newly released report published by the Amazon Conservation Team titled “Amazon Gold Rush: Gold Mining in Suriname” explores the rapid expansion and impacts of gold mining in Suriname through cartography and digital storytelling.

It finds that from 2000 to 2014, the extent of gold mining in the South American country increased by 893 percent.

While the Amazon rainforests of Brazil and Peru are well-known, Suriname’s vast and ancient rainforests remain one of the world’s best-kept natural secrets, according to the online report. But demand for the age-old elemental metal threatens to destroy them.

“According to our calculations, deforestation caused by gold mining has been growing steadily since the turn of the century and rapidly in the past five years,” GIS and Web Development Coordinator at the Amazon Conservation Team, Rudo Kemper told mongabay.com. The average rate of deforestation since 2000 is close to 3,000 hectares per year, but in 2014 an estimated 5,712 hectares of forest cover was lost to gold mining, he said. The REDD+ for the Guiana Shield regional collaborative study on gold mining shows similar trends, reporting a near-doubling (97 percent increase) of deforestation from 2008 to 2014 and attributing a total of 53,668 hectares of deforestation to gold mining in 2014.

Compared to many other South American countries, Suriname still holds much of its forest cover. According to Global Forest Watch, Suriname lost 0.7 percent of its tree cover from 2001 through 2014 – a small proportion compared to Brazil’s 6.9 percent. However, Suriname’s intact forest landscapes – large, continuous areas of primary forest – do show degradation since 2000.

The Guiana Shield, as Kemper puts it, is one of three cratons of the South American tectonic plate. “It is a tropical rainforest region covered with unique table-top mountains called tepuis,” he said. “It has the largest expanse of undisturbed tropical rainforest in the world, and one of the highest rates of biodiversity.” Suriname is among the most forested countries in the world, as the report highlights. In 2012, 95 percent of the country’s entire area was classified as forest. Globally surpassed only by its neighbor French Guiana, Suriname’s pristine rainforest harbors numerous unique species of fauna like the Guianan cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola rupicola), the famous blue poison dart frog (Dendrobates tinctorius), the red-faced spider monkey (Ateles paniscus), and the pale-throated sloth (Bradypus tridactylus). Jaguars, tapirs, and giant anteaters also call the region home. The mineral-rich Greenstone Belt region, where most of the gold mining in Suriname takes place, is primarily composed of the forested highlands of the Guiana Shield. Conservationists worry that deforestation caused by rapidly expanding gold mining activities is negatively impacting the habitat of many unique species.

Suriname rainforest. Photo courtesy of the Amazon Conservation Team.

Since the 1960s, development and resource extraction incursions into the country’s interior have become commonplace. These encroachments have taken the form of dam-building, logging, bauxite mining, and as of the turn of the century, small-scale and industrial gold mining, the report says. Given that it is one of the world’s smallest countries, Suriname’s annual rate of gold production might not compare to that of larger countries like South Africa, China, Russia or Peru. But relative to its land area, Suriname actually ranks tenth in global gold production.

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining explodes in Suriname, puts forests and people at risk.