by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 19, 2015 | Gender, Rape Culture

Robert Jensen / Nation of Change

For the past year, the media have been full of discussions of the endemic sexual violence in the contemporary United States, while at the same time pop culture has been celebrating the new visibility of the transgender movement. Both of these cases — which many take to be feminist successes — actually highlight patriarchy’s ability to adapt to challenges and undermine a radical critique of the domination/subordination dynamic at the heart of institutionalized male dominance.

In 25 years of being part of a radical feminist movement, I am less optimistic than ever about the capacity of our society to face the truth about the pathology of patriarchy. This culture of denial is not limited to sex/gender, but has become the norm in regard to the unjust and unsustainable hierarchies at the core of all of this society’s social, political and economic systems — with profound human and ecological implications.

Before defending this assertion, there’s a reasonable question to consider: Who cares what I think? I am, after all, a middle-aged white man, a tenured full professor at a large state university, with a U.S. passport, married to a woman. In privilege roulette, I am a winner on all the big identity markers: race, sex/gender, economic class, nationality, sexuality (the last one is complicated; more on that later). According to the rules of progressive politics, I’m supposed to preface every assertion I make with self-abnegation. Who am I to make claims about the proper analysis of these systems of illegitimate authority, given that I live on the domination side of all these dynamics?

Humility is a virtue, and people with my unearned advantages should double-down on humility. But false humility can become a rationalization for silence. Accepting the leadership of people from oppressed groups is an important principle, and privileged voices are not always needed in some debates. But on matters of public policy we all should be part of a collective conversation, and there also are times when people with privilege can say out loud what others say quietly in private. This essay offers my own analysis, but in solidarity with many others who share these views but feel constrained in speaking, out of concern for institutional standing and/or personal relationships.

Patriarchy

This past year I have written about rape culture and trans ideology, in both cases anchoring an analysis in the problem of patriarchy. I’m often told that the term “patriarchy” is either too radical and alienating, or outdated and irrelevant. Yet it’s difficult to imagine addressing problems if we can’t name and critique the system out of which the problems emerge.

The late feminist historian Gerda Lerner defined patriarchy as “the manifestation and institutionalization of male dominance over women and children in the family and the extension of male dominance over women in the society in general.” Patriarchy implies, she continued, “that men hold power in all the important institutions of society and that women are deprived of access to such power. It does not imply that women are either totally powerless or totally deprived of rights, influence and resources.”

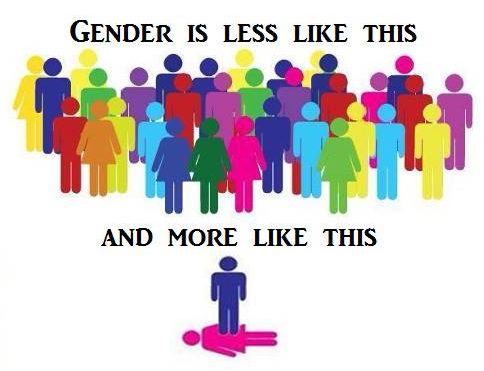

Like any resistance movement, feminism does not speak with one voice from a single unified analysis, but it’s hard to imagine a feminism that doesn’t start with the problem of patriarchy, one of the central systems of oppression that tries to naturalize a domination/subordination dynamic. In the case of feminism, this means challenging the way that patriarchy uses the biological differences between male and female (material sex differences) to justify rigid, repressive and reactionary claims about men and women (oppressive gender norms).

How should we understand the connection between sex and gender? Given that reproduction is not a trivial matter, the biological differences between male and female humans are not trivial, and it is plausible that these non-trivial physical differences could conceivably give rise to significant intellectual, emotional and moral differences between males and females. Yet for all the recent advances in biology and neuroscience, we still know relatively little about how the biological differences influence those capacities, though in contemporary culture many people routinely assume that the effects are greater than have been established. Male and female humans are much more similar than different, and in patriarchal societies based on gendered power, this focus on the differences is used to rationalize disparities in power.

In short: In patriarchy, “gender” is a category that functions to establish and reinforce inequality. While sex categories are part of any human society — and hence some sex-role differentiation is inevitable, given reproductive realities — the pernicious effects of patriarchal gender politics can, and should, be challenged.

Rape

In patriarchy, rape happens if a man forces a woman to have sex when the woman clearly has not consented or cannot consent. Only men who force women into sex in those situations are deemed to be rapists, only a small percentage of those rapes are reported to police, and an even smaller percentage of the rapists are arrested and convicted. The strategy of narrowing the definition of rape and limiting the number of men identified as rapists deflects attention from other questions about patriarchy’s eroticizing of domination and the resulting rape culture; from larger questions of how men are socialized to understand sexual activity, power and violence; and from the complex ways women are socialized to accommodate men’s demands.

Here’s one clear expression of this limiting strategy: “Rape is caused not by cultural factors but by the conscious decisions, of a small percentage of the community, to commit a violent crime.” Surprisingly, that statement is from a letter issued by one of the country’s leading anti-violence groups, the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, or RAINN. Even those working to end rape sometimes feel the need to ignore or avoid feminist insights, a phenomenon I explored in an essay last year.

Rape is a crime committed by individuals, of course, but it is committed within patriarchy, and if we were serious about reducing the number of rapes, we would be talking about the roots of that violence in patriarchy. But such an analysis doesn’t stop at what is legally defined as rape, and leads us to a painful inquiry into the patriarchal nature of what the culture accepts as “normal” sex based on men’s dominance. Those same patriarchal values define the sexual-exploitation industries (pornography, stripping, prostitution) and the routine sexual objectification of women in pop culture more generally.

So, the comfortable notion that we can condemn the bad rapists, and then all other sexual activity is beyond critique, evaporates in a feminist analysis. That doesn’t let rapists off the hook, but instead asks all of us to be honest about our own socialization. Taking rape seriously requires a feminist analysis of patriarchy, and that analysis takes us beyond rape to questions about how patriarchy’s domination/subordination dynamic structures our intimate lives, an inquiry that can be uncomfortable not only for those who endorse the dynamic but also for those who have accepted an accommodation with it.

This past year, with the media full of stories about the way in which women are particularly at risk in and around predominantly male institutions (fraternities, big-time athletics, the military), there is surprisingly little talk about patriarchy, about the socialization of men into toxic notions about masculinity-as-domination, especially in these hyper-masculine settings. The focus is diverted into questions about rules and regulations, about whether a particular university official, police officer, or commanding officer failed to hold a rapist accountable. All are relevant questions, but none is adequate to face the challenge.

What are we afraid of? The possibility that we can’t transcend patriarchy, that significant numbers of men won’t engage in the individual and collective critical self-reflection necessary? Are we worried that, without such self-reflection, we will not significantly reduce the myriad ways men not only rape but exploit women sexually?

I am not preaching from on high about this; I am a product of the same patriarchal culture and my work in feminism hasn’t magically freed me from the effects of that socialization. If anything, it’s made me more acutely aware of how easy it is to slip back into domination/subordination patterns, even when I’m trying to identify those behaviors and resist. I am worried, too, but that makes me more determined to hang onto the feminist framework.

Trans

The debate within feminism over trans, transgenderism and transsexualism (terms vary depending on speaker and context) goes back to the 1970s (the publication of Jan Raymond’s “The Transsexual Empire” in 1979 is a flash point) and continues today (the publication of Sheila Jeffreys’ “Gender Hurts: A Feminist Analysis of the Politics of Transgenderism” in 2014 is a new flash point). For a fair-minded account of the contemporary debate, see Michelle Goldberg’s recent New Yorker piece, “What is a woman? The dispute between radical feminism and transgenderism.”

In two previous essays, I articulated concerns about the transgender/transsexual ideology, rooted first in a feminist critique of the patriarchal gender norms at the heart of the trans movement, and second in the troubling ecological implications of embracing surgery and chemicals as a response to social and psychological struggles.

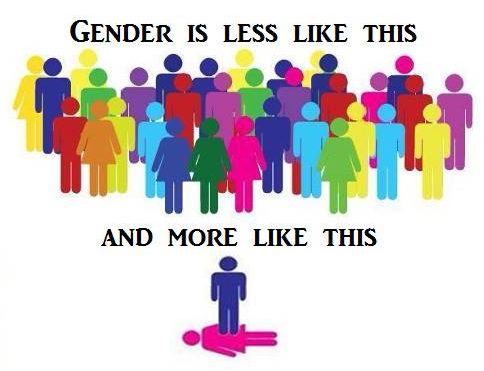

If one understands gender categories (man and woman) as being primarily socially constructed, then trans ideology actually strengthens patriarchy’s gender norms by suggesting that to express fully the traits traditionally assigned to the other gender, a person must switch to inhabit that gender category. For years, radical feminists have argued that to resist patriarchy’s rigid, repressive and reactionary gender norms, we should fight not for the right to change gender categories within patriarchy but to dismantle the system of gendered inequality.

If one understands socially defined gender categories as being primarily rooted in biological sex differences (male and female), then trans claims are not clear. If someone says, “I was born male but am actually female,” I do not understand what that means in the context of modern understandings of biology. (Note that people born “intersex,” with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not clearly fit the definitions of female or male, typically distinguish their condition from transgenderism.) Although not all transsexual people describe their experience as “being shipwrecked in the wrong body,” as one trans writer put it, I struggle to understand, no matter what the metaphor.

If there is an essence of maleness and femaleness that is non-material, in the spiritual realm, then it’s not clear how surgical or chemical changes in the body transform a person. If that essence of maleness and femaleness is material, in the biological realm, then it’s not clear how those changes in selected parts of the body transform a person.

I have been asking these questions not to attack the trans community, but because I cannot make sense of the trans movement’s claims and would like to understand. I am not suggesting that individuals who identify as trans/transgender/transsexual are somehow illegitimate or don’t have the right to their own understanding of themselves. But if that community asks for support on policy questions, such as public funding or mandatory insurance coverage for sex-reassignment surgery, the basis for that policy has to be intelligible to others.

So, I am not discounting the experience of people “whose gender identity, gender expression or behavior does not conform to that typically associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth,” the American Psychological Association’s definition of transgender. Instead, I am exploring alternatives to the trans accounts of that experience. For me, this is not an abstract question. As a child, I struggled with gender norms and sexuality. I was small and effeminate, one of those boys who clearly was not going to be able to “be a man,” as defined in patriarchy. My sexual orientation was unclear, as I struggled to understand my attraction to male and female, something that could not be openly discussed in the 1970s where I was growing up. And my early life included traumatic experiences that further complicated my self-understanding.

The story of my struggle has its ups and downs, with many moments of self-doubt and despair. Eventually, I came to terms with gender and sexuality through feminism — specifically the radical feminism that emerged from the anti-rape movement and critiques of the sexual-exploitation industries — and that politics gave me a sensible framework for understanding my history in social and political context. I often wonder what would have happened if, when I was an adolescent in the midst of those struggles, the culture had normalized trans ideology. I can’t see how a trans path, which does not demand that one wrestle with the pathology of patriarchy, would have left me better equipped to deal with gender and sexuality.

My experience doesn’t fit in the category of “gender dysphoria,” as I understand it, and I’m not projecting my experience on everyone who struggles with the brutality of patriarchy’s sex/gender system. I’m simply suggesting that the liberal ideology of the trans movement (liberal, in the sense that it focuses on an individual psychological response to structures of power and authority) is inadequate, and that demonizing those who raise relevant questions benefits no one.

Honest conversations

Supporters of patriarchy have had to yield to some of the demands of feminism, such as giving women access to previously closed-off opportunities in education, business and government. Most men committed to patriarchy have been willing to condemn the most abusive behaviors that come from institutionalized male dominance, so long as the core ideology is protected. These relatively small concessions, which do constitute a kind of progress, are often accepted as adequate, perhaps because a more direct confrontation with patriarchy is dangerous.

I think that’s why the current mainstream conversation about sexual violence so rarely confronts the patriarchal gender norms at the heart of the violence. Rather than going to the root of the problem, most commentary focuses on how changes in policy can minimize the risks to women and increase the effectiveness of criminal prosecutions of men who rape, as it is narrowly defined in the law. And given the very real suffering that results from men’s violence, anything that reduces that violence is important.

That’s also why the current mainstream conversation about trans so rarely directly challenges the rigid, repressive and reactionary gender norms of patriarchy. Rather than going to the root of the problem, most commentary focuses on how changes in individuals can alleviate their distress because of gender norms. And given the very real suffering that results from oppressive gender norms, anything that provides individual relief is important.

No one has a magic strategy to end men’s violence or eliminate oppressive gender roles. It’s possible that, given how entrenched patriarchy is worldwide, there is no way to overcome male dominance, at least not in the time available to us as the ecosphere’s capacity to support large-scale human societies erodes. But it’s difficult to imagine any progress without a deeper critique of patriarchy’s definitions of masculinity (dominance, competition, aggression) and femininity (demure, passive, objectified).

I’m not telling anyone how they must understand these issues or themselves, but I can’t see the value in suppressing critical questions out of a fear of being seen as too radical or insufficiently inclusive. Political movements are based on a shared analysis of the world, and that analysis can’t be fully developed unless relevant questions are open for discussion and debate.

My concern is that when a feminist analysis of rape in patriarchy is offered, mainstream voices dismiss it as “too radical.” Some of my friends in the movement against sexual violence have told me they feel pressure not to talk about patriarchy and feminism in their institutional work. That’s ironic, since rape crisis centers and domestic violence shelters typically were started by second-wave feminists with a radical critique. Many of those who staff those organizations today bring a radical analysis and spirit to that difficult work, but the fundraising and public-relations efforts for those centers tend to avoid the subject.

My concern is that when a feminist analysis of trans ideology is offered, mainstream voices dismiss it as not adequately inclusive. Friends have told me that they suppress their questions out of fear of being labeled transphobic and marginalized in work and personal networks. There are trans activists who incorporate a critique of patriarchy into their work, and more open conversation about these strategic questions would be beneficial to all, especially given the heightened vulnerability of people who identify as trans to sexual violence.

My concern is that we are losing the ability to face the pathology of patriarchy honestly, and we can’t fight what we can’t name. There is no guarantee of success in the struggle against patriarchy, but as James Baldwin put it more than 50 years ago, “Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

From Nation of Change: http://www.nationofchange.org/2015/01/08/feminism-unheeded/

Image Credit: Betty Wiggins, based on original work at artivismproject

by DGR News Service | Jul 19, 2014 | Gender, Women & Radical Feminism

Deep Green Resistance condemns in the strongest possible terms the decision of Monkeywrench Books in Austin, Texas to cut ties with activist Robert Jensen. Robert has received a massive amount of criticism recently for his article “Some Basic Propositions About Sex, Gender and Patriarchy”, in which he makes public his support for women. That so many have been quick to turn on a seasoned activist for the crime of saying that females exist is not surprising; the women of DGR, like thousands of radical women throughout history, know all too well the threats, insults, denunciations, and other abuse that comes to those who question the genderist ideology and stand with women in the fight for liberation from male violence.

Deep Green Resistance would like to publicly thank Robert Jensen for his activism and offer our support in this trying time. In a world where so-called “radical” communities are blacklisting actually radical women at a breakneck pace – while pedophile rapists like Hakim Bey and misogynists like Bob Black are welcomed with open arms – Robert has been a uniquely positive exception to the Left’s legacy of woman-hating. His contributions to the discussion around radical opposition to pornography, prostitution, and other forms of violence are especially valuable. DGR would like to acknowledge Robert’s efforts as a model for male solidarity work and offer our full support. The men of DGR specifically would like to extend a thanks to Robert for his huge influence in many of their lives.

by DGR News Service | Jun 21, 2014 | Gender, Repression at Home

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Despite the seeming popularity of environmental and social justice work in the modern world, we’re not winning. We’re losing. In fact, we’re losing really badly. [1]

Why is that?

One reason is because few popular strategies pose real threats to power. That’s not an accident: the rules of social change have been clearly defined by those in power. Either you play by the rules — rules which don’t allow you to win — or you break free of the rules, and face the consequences.

Play By The Rules, or Raise the Stakes

We all know the rules: you’re allowed to vote for either one capitalist or the other, vote with your dollars,[2] write petitions (you really should sign this one), you can shop at local businesses, you can eat organic food (if you can afford it), and you can do all kinds of great things!

But if you step outside the box of acceptable activism, you’re asking for trouble. At best, you’ll face ridicule and scorn. But the real heat is reserved for movements that pose real threats. Whether broad-based people’s movements like Occupy or more focused revolutionary threats like the Black Panthers, threats to power break the most important rule they want us to follow: never fight back.

State Tactic #1: Overt Repression

Fighting back – indeed, any real resistance – is sacrilegious to those in power. Their response is often straightforward: a dozen cops slam you to the ground and cuff you; “less-lethal” weapons cover the advance of a line of riot police; the sharp report of SWAT team’s bullets.

This type of overt repression is brutally effective. When faced with jail, serious injury, or even death, most don’t have the courage and the strategy to go on. As we have seen, state violence can behead a movement.

That was the case with Fred Hampton, an up-and-coming Black Panther Party leader in Chicago, Illinois. A talented organizer, Hampton made significant gains for the Panthers in Chicago, working to end violence between rival (mostly black) gangs and building revolutionary alliances with groups like the Young Lords, Students for A Democratic Society, and the Brown Berets. He also contributed to community education work and to the Panther’s free breakfast program.

These activities could not be tolerated by those in power: they knew that a charismatic, strategic thinker like Hampton could be the nucleus of revolution. So, they decided to murder him. On December 4, 1969, an FBI snitch slipped Hampton a sedative. Chicago police and FBI agents entered his home, shot and killed the guard, Mark Clark, and entered Hampton’s room. The cops fired two shots directly into his head as he lay unconscious. He was 21 years old.

The Occupy Movement, at its height, posed a threat to power by making the realities of mass anti-capitalism and discontent visible, and by providing physical focal points for the dissent that spawns revolution. While Occupy had some issues (such as the difficulties of consensus decision-making and generally poor responses to abusive behavior inside camps), the movement was dynamic. It claimed physical space for the messy work of revolution to happen, and represented the locus of a true threat.

The response was predictable: the media assaulted relentlessly, businesses led efforts to change local laws and outlaw encampments, and riot police were called in as the knockout punch. It was a devastating flurry of blows, and the movement hasn’t yet recovered. (Although many of the lessons learned at Occupy may serve us well in the coming years).

State Tactic #2: Covert Repression

Violent repression is glaring. It gets covered in the news, and you can see it on the streets. But other times, repression isn’t so obvious. A recent leaked document from the private security and corporate intelligence firm Strategic Forecasting, Inc. (better known as STRATFOR) contained this illustrative statement:

Most authorities will tolerate a certain amount of activism because it is seen as a way to let off steam. They appease the protesters by letting them think that they are making a difference — as long as the protesters do not pose a threat. But as protest movements grow, authorities will act more aggressively to neutralize the organizers.

The key word is neutralize: it represents a more sophisticated strategy on behalf of power, a set of tactics more insidious than brute force.

Most of us have probably heard about COINTELPRO (shorthand for Counter-Intelligence Program), a covert FBI program officially underway between 1956 and 1971. COINTELPRO mainly targeted socialists and communists, black nationalists, Civil Rights groups, the American Indian Movement, and much of the left, from Quakers to Weathermen. The FBI used four main techniques to undermine, discredit, eliminate, and otherwise neutralize these threats:

- Force

- Harassment (subpoenas, false accusations, discriminatory enforcement of taxation, etc.)

- Infiltration

- Psychological warfare

How can we become resilient to these threats? Perhaps the first step is to understand them; to internalize the consequences of the tactics being used against us.

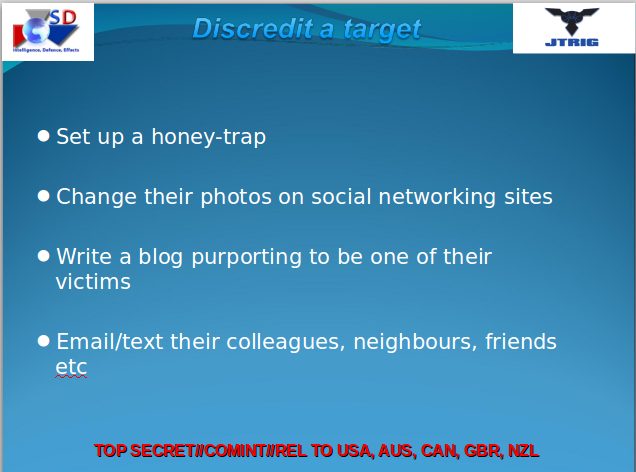

The JTRIG Leaks

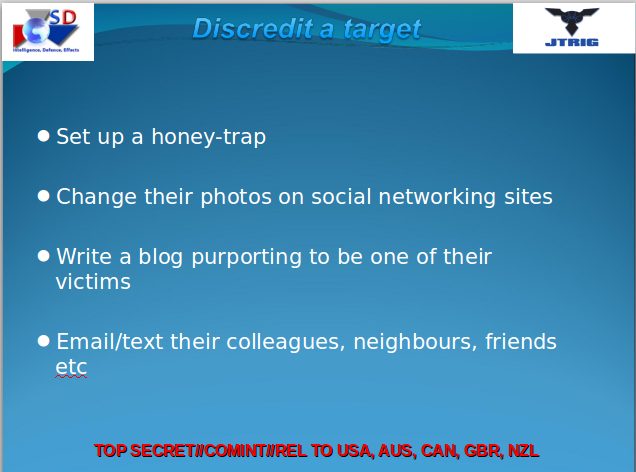

On February 24 of this year, Glenn Greenwald released an article detailing a secret National Security Agency (NSA) unit called JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group). The article, which sheds new light on the tactics used to suppress social movements and threats to power, is worth quoting at length:

Among the core self-identified purposes of JTRIG are two tactics: (1) to inject all sorts of false material onto the internet in order to destroy the reputation of its targets; and (2) to use social sciences and other techniques to manipulate online discourse and activism to generate outcomes it considers desirable. To see how extremist these programs are, just consider the tactics they boast of using to achieve those ends: “false flag operations” (posting material to the internet and falsely attributing it to someone else), fake victim blog posts (pretending to be a victim of the individual whose reputation they want to destroy), and posting “negative information” on various forums.

It shouldn’t come as a total surprise that those in power use lies, manipulation, false information, fake identities, and “manipulation [of] online discourse” to further their ends. They always fight dirty; it’s what they do. They never fight fair, they can never allow truth to be shown, because to do so would expose their own weakness.

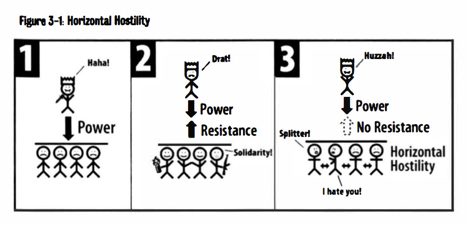

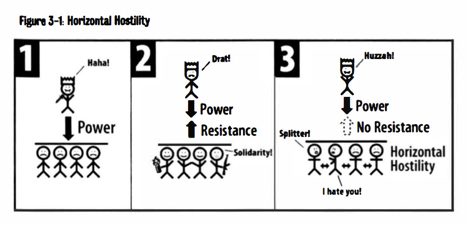

As shown by COINTELPRO, this type of operation is highly effective at neutralizing threats. Snitchjacketing and divisive movement tactics were used widely during the COINTELPRO era, and encouraged activists to break ties, create rivalries, and vie against one another. In many cases, it even led to violence: prominent, good hearted activists would be labeled “snitches” by agents, and would be isolated, shunned, and even killed.

As a friend put it,

“By encouraging horizontal, crowdsourced repression, activists’ focus is shifted safely away from those in power and towards each other.”

Are Activists Targeted?

Some organizations have ideas so revolutionary, so incendiary that they pose a threat all by themselves, simply by existing.

Deep Green Resistance is such a group. If these tactics are being used to neutralize activist groups, then Deep Green Resistance (DGR) seems a prime target. Proudly Luddite in character, DGR believes that the industrial way of life, the soil-destroying process known as agriculture, and the social system called civilization are literally killing the planet – at the rate of 200 species extinctions, 30 million trees, and 100 million tons of CO2 every day. With numbers like that, time is short.

With two key pieces of knowledge, the DGR strategy comes into focus. The first is that global industrial civilization will inevitably collapse under the weight of its own destructiveness. The second is that this collapse isn’t coming soon enough: life on Earth could very well be doomed by the time this collapse stops the accelerating destruction.

With these understandings, DGR advocates for a strategy to pro-actively dismantle industrial civilization. The strategy (which acknowledges that resisters will face fierce opposition from governments, corporations, and those who cling to modern life) calls for direct attacks on critical infrastructure – electric grids, fossil fuel networks, communications, etc. – with one goal: to shut down the global industrial economy. Permanently.

The strategy of direct attacks on infrastructure has been used in countless wars, uprisings, and conflicts because it is extremely effective. The same strategies are taught at military schools and training camps around the planet, and it is for this reason – an effective strategy – that DGR poses a real and serious threat to power. Of course, writing openly about such activities and then taking part in them would be stupid, which is why DGR is an “aboveground” organization. Our work is limited to building a culture of resistance (which is no easy feat: our work spans the range of activities from non-violent resistance to educational campaigns, community organizing, and building alternative systems) and spreading the strategies that we advocate in the hope that clandestine networks can pull off the dirty work in secret.

When I speak to veterans – hard-jawed ex-special forces guys – they say the strategy is good. It’s a real threat.

Threat Met With Backlash

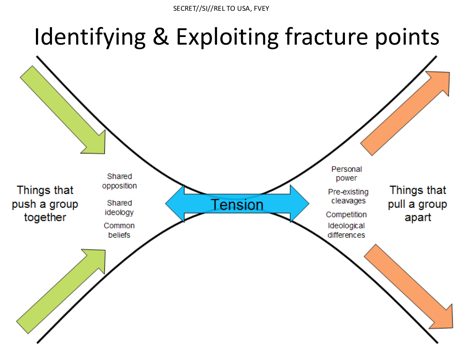

That threat has not gone unanswered. In a somewhat unsurprising twist, given the information we’ve gone over already, DGR’s greatest challenges have not come from the government, at least not overtly. Instead, the biggest challenges have come from radical environmentalists and social justice activists: from those we would expect to be among our supporters and allies. The focal point of the controversy? Gender.

The conflict has a long history and deserves a few hours of discussion and reading, but here is the short version: DGR holds that female-only spaces should be reserved for females. This offends many who believe that male-born individuals (who later come to identify as female) should be allowed access to these spaces. It’s all part of a broader, ongoing disagreement between gender abolitionists (like DGR and others), who see gender as the cultural lattice of women’s oppression, and those who view gender as an identity that is beyond criticism.

(To learn more about the conflict, view Rachel Ivey’s presentation entitled The End of Gender.)

Due to this position, our organization has been blacklisted from speaking at various venues, our organizers have received threats of violence (often sexualized), and our participation in a number of struggles has been blocked – at the expense of the cause at hand.

A Case Study in JTRIG?

Much of the anti-DGR rhetoric has been extraordinary, not for passionate political disagreement, but for misinformation and what appears to be COINTELPRO-style divisiveness. Are we the victims of a JTRIG-style smear campaign?

On February 23 of this year, the Earth First! Newswire released an anonymous article attacking Deep Green Resistance. The main subject of the article was the ongoing debate over gender issues.

(Although perhaps debate is the wrong word in this case: Earth First! Newswire has published half a dozen vitriolic pieces attacking DGR. They seem to have an obsession. On the other hand, DGR has never used organizational resources or platforms to publish a negative comment about Earth First.)

Here are a few of the fabrications contained in the February 23 article:

- “Keith and Jensen [DGR co-founders] do not recognize the validity of traditionally marginalized struggles [like] Black Power.” (a wild, false claim, given the long and public history of anti-racist work and solidarity by those two. [3])

- DGR members have “outed” transgender people by posting naked photos of them. (Completely false not to mention obscene and offensive.[4])

- DGR is “allied with” gay-to-straight conversion camps. (The lies get ever more absurd. DGR has countless lesbian and gay members, including founding members. Lesbian and gay members are involved at every level of decision making in DGR.)

- DGR requires “genital checks” for new members. (I can’t believe we even have to address this – it’s a surreal accusation. It is, of course, a lie.)

If these claims weren’t so serious, they would be laughable. But lies like this are no laughing matter.

Here is one illustrative list of tactics from the JTRIG leaks:

“Crowdsourced Repression”

The timing of these events – the Earth First! Newswire article followed the very next day by Greenwald’s JTRIG article – is ironic. Of course, it made me think: are we the victims of a JTRIG-style character assassination? Or am I drawing conclusions where there are none to be drawn?

The campaigns against DGR do have many of the hallmarks of COINTELPRO-style repression. They are built on a foundation of political differences magnified into divisive hatred through paranoia and the spread of hearsay. In the 1960s and 70s, techniques that seem similar were used to create divisions within groups like the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement.

Ultimately, these movements tore themselves apart in violence and suspicion; the powerful were laughing all the way to the bank. In many cases, we don’t even know if the FBI was involved; what is certain is that the FBI-style tactics – snitchjacketing, rumormongering, the sowing of division and hatred – were being adopted by paranoid activists.

In some ways, the truth doesn’t really matter. Whether these activists were working for the state or not, they served to destroy movements, alliances, and friendships that took decades or generations to build.

I’ll be clear: I don’t mean to claim that the “Letter Collective” (as the anonymous authors of the February 23 article named themselves) are agents of the state. To do so would be a violation of security culture. [5] Modern activists seem to have largely forgotten the lessons of COINTELPRO, and I am wary of forgetting those lessons myself. Snitchjacketing is a bad behavior, and we should have no tolerance for it unless there is substantive evidence.

But members of the “Letter Collective”, at the very least, have violated security culture by spreading rumors and unsubstantiated claims of serious misconduct. Good security culture practices preclude this behavior. In the face of JTRIG and the modern surveillance and repression state, careful validation of serious claims is the least that activists can do. Didn’t we learn this lesson in the 60s?

Divide and Conquer

By itself, verifying rumors before spreading them is a poor defense against the repression modern activists face. Instead, we must challenge divisiveness itself: one of the biggest threats to our success.

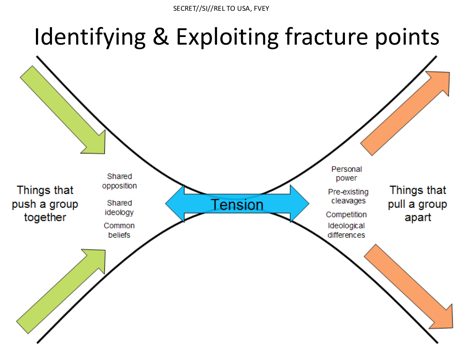

The 2011 STRATFOR leak included information about corporate strategies to neutralize activist and community movements. Essentially, STRATFOR advocates dividing movements into four character types: radicals, idealists, realists, and opportunists. These camps can then be dealt with summarily:

First, isolate the radicals. Second, “cultivate” the idealists and “educate” them into becoming realists. And finally, co-opt the realists into agreeing with industry. [6]

This is how movements are neutralized: those who should be allies are divided, infighting becomes rampant, and paranoia rules the roost. To combat these strategies, we must understand the danger they represent and how to counter them.

Fight Repression With Solidarity

We all want to win. We want to end capitalism, reverse ecological collapse, and build a culture in which social justice is fundamental. Many of us have different specific goals or strategies, but we must find similarities, overlaps, and areas where we can work together.

As Bob Ages, commenting on STRATFOR’s divide-and-conquer tactics, put it in a recent piece:

“Our response has to be the opposite; bridging divides, foster mutual understanding and solidarity, stand together come hell or high water.”

Many people across the left share 80% or more of their politics, and yet constructive criticism and mature discussion of disagreements is the exception, not the rule. We need more thoughtful behavior. Don’t spread rumors, don’t tear down other activists, and don’t forget who the real enemy is. Don’t waste your time fighting those who should be your allies – even if they are only partial allies. Let’s disagree, and let our disagreements help us learn more from each other and build alliances.

In the end, that’s our only chance of winning: together.

References

Max Wilbert lives in the Pacific Northwest, where he works to support indigenous resistance to industrial extraction projects, anti-racist initiatives, and radical feminist struggles as part of Deep Green Resistance. He makes his living as a writer and photographer, and can be contacted at max@maxwilbert.org.

From Dissident Voice

by DGR News Service | Mar 24, 2014 | Gender, Women & Radical Feminism

By Rachel / Deep Green Resistance Eugene

The following is a response to an open letter written by Bonnie Mann to Lierre Keith.

Hello Professor Mann,

You wrote an open letter recently to my friend and fellow activist Lierre Keith. You don’t know me, and I don’t know you, but as your letter discusses issues which are very important to me, and as I feel that you’ve gravely misconstrued those issues, it feels incumbent upon me to respond. You may choose to write me off as “uncritical,” since I share the views that you have dismissed as such in your letter, but I hope that you will instead choose to listen and reflect on my reasons for finding your letter uncritical at best, and in all truth, irresponsibly misleading at worst. At the risk of casting too wide a net, there are two things I’d like to address: the things you say in your letter, and the things you don’t say in your letter.

You write that you don’t support those who tried (and failed) to get Lierre’s invitation to speak rescinded, because “you don’t get ‘safe space’ in the public sense from not being subjected to attacks, or to the presence of those by whom you consider yourself to have been attacked.” You don’t specify whether by attacks you are referring to political disagreement, or the kind of rape and death threats, stalking, sexual harassment, and occasional physical assault to which I and other radical feminists are regularly subject. This ambiguity, which pervades your letter’s arguments, works to stymie direct discussion of the issues. If by “attacks” you mean “political disagreement,” then I agree. Contrary to the beliefs of many who try to blacklist radical feminist thought from the public sphere, I do not believe that mere disagreement is equivalent to physical violence.

You go on to say: “I think you get safe space, or as safe as space gets, from having your community stand by you in the face of attacks.” If that’s true, then “as safe as safe space gets” feels pretty damn unsafe when you dare to question the inevitability or the justice of gender. I and the radical feminists I know have formed a community that supports each other in the face of attacks. Unfortunately, supporting each other has not stopped the bullying, the rape and death threats, the intimidation and the stalking and the harassment. This is as safe as space gets for radical feminists who stick to their convictions instead of abandoning them. It’s disturbing to me that nowhere in your letter do you even acknowledge the reality of what we deal with every time we open our mouths to disagree with the currently popular ideology around gender.

You mention having watched a presentation of mine on gender that I wrote about a year ago, entitled “The End of Gender” (or alternatively “I Was a Teenage Liberal”), so I won’t waste time on details of my past that you, presumably, are already familiar with. Suffice it to say that my views on gender have taken the opposite trajectory from yours. One of the most easily challengeable and, frankly, one of the cheapest ways that you dismiss Lierre’s politics in your letter is by suggesting that they are less valuable because they are so old as to be archaic or outmoded. You imply this by describing how reading her arguments brings you “back in time,” and by mentioning several times that you also heard those same arguments from her thirty two years ago. That argument might seem slightly more viable if Lierre, or others in her and your generation, were the only ones who hold similar convictions today.

My very existence (much less my work as an activist) renders that line of criticism less-than-viable. You wrote that you last spoke to Lierre in 1989, but I was born in 1989, and women closer to my age are some of the most vocal and active gender-critical feminists I know. Some of us, the lucky ones, benefit from the support and guidance of women who have been feminists since before we were born. Others came to radicalism because they could see that the ideology we’ve been fed by academia and the dominant culture – individualist, neoliberal “feminism” – is actively working against the advancement of women’s human rights. Young women organize radical feminist conferences, write gender-critical analysis, fight to maintain the right of females to organize as a class, and support each other through the intimidation, threats, and ostracization that such work earns us. We do not appreciate being ignored by those who would take the easy way out in dismissing our politics.

You write that the ideology of gender that gave rise to today’s trans ideology and practice was “brand new” to you at the time you first encountered it, and that it “freaked you out” because it “didn’t match the analysis” that you held at the time, which you equate to the analysis that Lierre and I and so many others hold today. Your implication, and the dismissal it contains, is clear – radical feminist disagreement with liberal gender ideology stems from cognitive dissonance and unease toward unfamiliar ideas, not from reasoned analysis. You imply that radical feminism is an artifact from an earlier time, and that the only women who still cling to it do so because they are afraid of new ideas. Again, you write as if women of your and Lierre’s generation who share your early experience of feminism are the only radical feminists who still walk the Earth.

This argument falls completely flat for me and so many radical feminists of my generation. Liberal gender ideology has never been “brand new” for us. It is not unfamiliar to us; we grew up swimming in it. We’re not clinging to relics, we’re reaching for a politics that actually addresses the scope of the problems. It was gender-apologism that began to give us cognitive dissonance, after our experiences brought us to some uncomfortable and challenging conclusions: Female people are a distinct social class, and its members experience specific modes of oppression based on the fact that we’re female. All oppressed classes have the right to organize autonomously and define the boundaries of their own space. Gender is socially constructed; there are no modes of behavior necessarily associated with biological sex. The norms of gender function to facilitate the extraction of resources from female bodies. The extraction of resources from female bodies forms the foundation of male supremacy, and thusly, male supremacy fundamentally depends on the maintenance of gender.

Like many of radical feminism’s detractors, you have chosen to focus your response to our politics on one statement, perceived belief, or piece of writing, which is taken as a representation of us as a group in order to make it easier to misconstrue and dismiss our views. This is called scapegoating, and Lierre’s email is an oft-selected target for it. I understand that your letter was addressed to Lierre, and so it makes sense that you would focus on her stated views. However, there are multiple other more recent and detailed pieces of writing from her on the subject that you chose to ignore. Maybe the choice to exclude these was “a symptom of not listening.” Maybe it “marks a distaste for complexity, ambiguity, nuance.” I don’t pretend to know, but it was clearly a choice that allowed you to sidestep direct engagement with the basic principles and broader conclusions of radical feminist politics.

In describing your views before you adopted your current ideology around gender, you write that “we weren’t afraid of the people so much as we were afraid of the phenomenon. Why? Because if gender is a sex-class system, and that’s all it is, there is no way to explain the existence of trans women at all. That’s like white people trying to get into the slavery of the 1840s. If gender is a sex-class system, and that’s all it is, then the only “trans” should be female to male, because everybody should be trying to get out and nobody should be trying to get in – yet it’s the transition from male to female that is cited as troubling.”

First of all, if you had bothered to take a broader and more accurate view of Lierre’s gender politics and her writing on the subject, you’d have found that she does not only cite the transition from male to female as troubling. She cites the entire system of enforced stereotypes called gender as troubling, including the trans ideology that justifies enforcing the categorization of qualities and behavior, and presents cutting up people’s bodies to fit those enforced stereotypes as a solution. I do appreciate that you actually engage with some of her arguments, since most who choose to scapegoat her usually skip directly to threats and insults. However, your analysis of the two analogies you chose to address leave some things to be desired. You begin with:

“I am a rich person stuck in a poor person’s body. I’ve always enjoyed champagne rather than beer, and always knew I belonged in first class not economy, and it just feels right when people wait on me.”

This is only a reverse analogy, as you call it, if you believe that she is only intending to address the phenomenon of male people identifying themselves as female. You’re correct that this example, when applied to gender, is analogous to a female person identifying themselves as male. I do not believe that this fact lessens its illustrative power. If this “rich person stuck in a poor person’s body” tried to “transition” to higher economic status based on their inner identification with wealth, how do you think they’d be treated by actual rich people? Might the treatment of this person mirror, say, the treatment of a trans man trying to join a group of men’s rights activists (MRAs)? Here’s a better question: Even if this person was able to “pass” as wealthy by appearing and acting to be so, would their passing have any affect at all on the capitalist structures of power that keeps them in poverty in the first place? Would passing as wealthy in appearance help them acquire actual financial power? Would it retroactively grant them a silver spoon at birth and a BMW on their sixteenth birthday?

You reverse the analogy (“I’m rich, but I’ve always identified as poor, so I divest myself of my wealth and go join the working class”) and say that it’s less powerful that way. I disagree. I think that the reversed version is extremely illustrative of the flaws in your argument, and in liberal thinking more generally. You write:

“Who wouldn’t welcome you, if you really divested yourself of your wealth and joined marches in the street to increase the minimum wage?”

Do you really think that someone can divest themselves not only of their material wealth, but of their history as a wealthy person? I don’t know about you, but if a rich person voluntarily gave up their wealth and said to me “Hey fellow member of the working class! I’m just like you, and there is no difference between our experiences of the world,” I’d tell them to fuck off. Becoming penniless now is not equivalent to going hungry as a kid, struggling to afford education throughout your life, watching your parents pour their lives into multiple underpaid jobs, or having to decide between rent and medical bills. It’s insulting to suggest that someone can shrug off years of privilege and entitlement and safety at will. In large part, growing up with privilege is the privilege. The punishment meted out to males who disobey the dictums of masculinity (a punishment that is yet another negative effect of the sex caste system) can be severe, and of course it’s indefensible. However, it is distinct from the systematic exploitation that females experience because we are female.

You go on to the second analogy: “I am really native American. How do I know? I’ve always felt a special connection to animals, and started building tee pees in the backyard as soon as I was old enough. I insisted on wearing moccassins to school even though the other kids made fun of me and my parents punished me for it. I read everything I could on native people, started going to sweat lodges and pow wows as soon as I was old enough, and I knew that was the real me. And if you bio-Indians don’t accept us trans-Indians, then you are just as genocidal and oppressive as the Europeans.”

You respond: “Maybe we thought gender was a ‘a class condition created by a brutal arrangement of power,’ and only that, but we would never have made the same claim about being native American. Why? It’s blatently reductive. It’s reducing a rich set of histories, cultures, languages, religions, and practices to the effect of a brutal arrangement of power – which is of course a very important part of it. But “being native American” is not merely an effect of power, in the way we thought gender was.”

Your objections to these analogies consistently prove the points that you’re trying to challenge. Of course gender cannot be parallel to “being native American” in this or any other analogy. Gender is parallel to colonial ideology in this analogy. More specifically, male supremacy is parallel to the colonialial power relation in this analogy, and gender is parallel with the stereotypes that colonialism imposes onto the colonized. The “drunk Indian” stereotype, or the image of the “savage,” only have anything to do with “being native American” because the ideology and practice of white supremacy was and continues to be imposed by Europeans on an entire continent’s peoples in order to exploit them. The female stereotypes we call “femininity” (domestic laborer, mother, infantalized sex object) only have anything to do with being female because the ideology (gender) and practice (patriarchy) of male supremacy was and is imposed by males onto females in order to exploit them. Of course it’s reductive to condense an entire distinct, specific set of experiences, the good and bad and everything in between, into a brutal arrangement of power – and this is exactly what gender does.

Gender takes the lived experiences of being female or being male and reduces those experience to sets of stereotypes. Transgender ideology retains those same oppressive stereotypes, but liberalizes their application by asserting that anyone can embody either set of stereotypes, regardless of their biological sex. This does not take away the destructiveness and reductiveness of the stereotypes, and in fact it reinforces them. The existence of outlaws requires the law, and maintaining an identity as a “gender outlaw” requires that the law – the sex castes – be in full effect for the rest of us. If “twisting free” of gender and the power relations of male supremacy is possible for a few of us, doesn’t that mean that those of us who fail to twist free are choosing the oppression we experience under gender? Perhaps we’re not trying hard enough to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps. How about other oppressive power arrangements – do the colonized, the racially subjugated, or those in poverty ever get to “twist free” of the power relations they live within? Do racial stereotypes, for instance, “take on a life of their own in the imaginary domain”? To defend gender as even occasionally being estranged from the machinations of power is to defend male supremacy, and to argue that any aspect of society can be apolitical is to completely ignore the ways that hegemony actually functions.

The only other groups of people who have argued to me that gender stereotypes are natural, biological, or apolitical, aside from gender-apologists, are fundamentalist christians and MRA’s. Forgive me if I don’t see how this is remotely progressive. This represents an adjustment in the rhetoric of patriarchy – not resistance to it. These stereotypes are not arbitrary; just like the stereotype of the Indian “savage,” or of the lazy (brown) immigrant, or of the freeloading (brown) “welfare queen,” the stereotypes called gender function to facilitate the extraction of resources. In the case of the “savage” Indian stereotype, the resource in question was and still is land. In the case of women, the resources are labor, reproduction, and sex, and the stereotypes (housewife, mother, infantalized sex object) come to match. It’s not an accident that these stereotypes correspond with the resources that women are exploited for. This is the purpose of gender. What does it mean that those in the academy almost universally embrace the idea that these regressive stereotypes must be reformed, justified, normalized, fetishized, idealized, and extended – but never challenged at their root?

I think you’re right that misogyny is not the conscious reasoning of every male person who begins identifying themselves as female. When I was a high school teacher, I had male students who were told by counselors that they were sick with “gender dysphoria” and put on hormones by doctors because they failed to live up to masculine stereotypes. These boys aren’t consciously out to invade female space – but they, and the abuse that they receive at the hands of the medical and psychiatric establishments, certainly aren’t poster children for why gender castes deserve to be rationalized or maintained. The fact that some males have a negative experience of gender does not erase the fact that structurally, on the macro level, gender exists to facilitate the extraction of resources from female bodies. Gender is the chain, and male supremacy is the ball. Just because males sometimes trip over that chain does not erase the fact that the ankle it’s cuffed to is always female.

I think you’re right that when you say that we “negotiate and take up and resist and contest or affirm these structures in profoundly complex ways and sometimes deeply individual, creative, and unique ways,” but it sounds like you’re using the fact that individuals have varied experiences to dismiss or minimize the reality of the larger structures that those experiences occur within. Individual experiences may not always match up with the larger structures of exploitation, but this does not mean that those larger structures become irrelevant. I also think you’re right that each of us “seeks a way of living, a way of having the world that is bearable.” But this does not erase the fact that gender, the stereotypes that it is composed of, and the exploitation it facilitates, compose one of the oppressive systems preventing us from finding a bearable, much less a safe or just, way of having the world.

You end your letter by, yet again, expressing a patronizing disapproval that Lierre has held the same convictions for thirty two years. I agree that we should constantly be seeking new information, new perspectives, and actively incorporating them into our politics. However, holding consistent core convictions isn’t always an indication of stagnation or dogmatism – sometimes it’s called “having principles.” Would you use this argument against others who stick to their political guns in the face of backlash and opposition? Indigenous communities that have fought for sovereignty for centuries? The women who struggled through the generations for suffrage?

Putting radical feminist principles (like the right of females to organize autonomously) into practice comes with a cost. I and others have come to accept that cost after challenging, painful analysis of radical feminism’s merits. You dismiss Lierre’s radical feminism as an “uncritical” relic from a simpler time, but for me and others in my position, radical feminism has been a lifeline of critical thought. We grew up within a “feminism” that uncritically accepted the inevitability and the naturalness of gender, the neoliberal primacy of individualism, and ultimately, the unchallengeability of male supremacy. You characterize those who hold firm to feminist political convictions as fetishizing clean lines, simplicity, and the safety of familiarity. I’m here to tell you that my worldview was a lot simpler and more familiar back when I believed that gender stereotypes were voluntary, natural, defensible, inevitable, even holy. My life was a lot simpler and safer when I was content to keep quiet and continue parroting liberal nonsense. You’re right that individual experiences of gender differ, and you’re right that the situation is complicated, but complexity does not have to derail the fight against male supremacy on behalf of women as a class – at least, it doesn’t have to for all of us.

-Rachel

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 1, 2013 | Gender, Male Violence, Women & Radical Feminism

By Kourtney Mitchell / Deep Green Resistance

The following speech was originally given at the Stop Porn Culture Conference at Wheelock College, Boston, in July 2013.

Hello everyone, my name is Kourtney Mitchell and I am a political activist and a member of the group Deep Green Resistance. We are a radical organization dedicated to social, political and environmental justice. As an organization we ally ourselves with indigenous communities, women, people of color and the poor. Our aim is to stop the destruction of the planet and the oppression of people and animals.

We are a relatively new organization just a couple of years old but we are growing and have numerous chapters with hundreds of activists around the world who are all dedicated to stopping the genocide of the planet.

So, I’ll offer just a brief background on my experience as a man with pro-feminist activism and educating men. I attended university and it was there that I first received academic and activist training in feminism and anti-violence through the peer education program on campus.

The peer education program consists of graduate students, faculty, and staff who train undergraduate volunteers. The training includes education about the widespread violence that women face and volunteers learn to give presentations to peers on rape, sexual assault, relationship violence, and feminism.

In turn, peers would then join our organizing efforts and events. This was the most profoundly significant and life changing time for me. To travel around the country raising awareness of violence against women, facilitating workshops, speak-outs, and protests was fulfilling, not to mention meaningful. The training threw me into another world, one in which violence and misogyny could no longer be ignored. Our advisors did a really comprehensive job of giving us an adequate scope of the problem, and creating a sense of urgency about these issues.

They helped facilitate the creation of a student culture based on the belief that it is possible to end violence against women, and knowing that possibility helped galvanize us to take action. Many of us went on to make this our life’s work.

My primary role in the campus activist community was recruiting and teaching men about pro-feminism and anti-violence. I helped lead the male ally program, which included a weekly discussion group, activism in the community, pro-feminist art and performance, and collaborations with other similar programs around the country.

I remember vividly the anxiety of pouring over every detail of presentations I would be giving to men, worrying if the way I presented concepts was too complicated or if men would shut down for the rest of the talk if I said something too complicated. I left some events feeling like no one was reachable, but I also walked away feeling really good about the successes which were accomplished.

Many men joined our organizations and became quite active – some because they just felt it was the right thing to do, but many more because of personal experiences and the experiences of their loved ones. Several men randomly wandered into our office and left planning to attend the next ally meeting, and sure enough did continue coming. This was just one of the many things that kept me optimistic about bringing more men to pro-feminist ideas and activism.

Unfortunately, the campus activist community was largely liberal and very much influenced by queer theory. Pornography was widely accepted, and a real revolution against the patriarchal order was more joked about than seriously considered. It wasn’t until I was introduced to the radical feminist perspective that I began to see the flaws of the liberal approach to pro-feminist education.

The liberal approach leaves out an important aspect of the violence men commit against women: that men hate women. It’s important to say that out loud and allow it to inform our actions. The dominant culture is insane. Its norms and values are pathological, and it socializes people into roles that encourage, even necessitate abuse and exploitation in order to fulfill accepted social roles.

The systems of rewards in this culture makes it appear as if the masculine identity and domination imperative are in our best interest, and dissent is seen as blasphemy — a violation of a sacred order.

And that sacred order is gender.

Masculinity fraternizes men into a veritable cult, one that requires violence and callousness in order to ensure the privileges of membership. The liberal approach has been able to raise the awareness of some men concerning the male violence, but it doesn’t challenge men on the mechanism of their oppression of women.

Just when I thought we could really get somewhere with bringing men into pro-feminist activism, the radical analysis gave me a hard dose of reality. I had always thought that if we could just get men to stop and think for a minute, to look around and see the world for what it really is, to get them to cultivate some empathy, then maybe we could start to see a reversal of toxic male culture. What I learned was that it’s hard enough to get men to consider feminism at all let alone to consider challenging their own behavior.

Once you start to get too radical, most men shut down or lash out against it. A few really do embrace it, and that’s something I hold on to—that there are some men out there who are thoughtful enough, and self-reflective enough, and honest enough to internalize the hard truths—but I also realize that most men will never be genuine allies. In fact, most so-called radical men have proven that they are not only incapable of understanding the radical feminist analysis of gender but that they will actively fight against women who espouse it.

The liberal approach to activism is disheartening because it constantly conditions activists to keep working to build an impossible mass movement, and it keeps people hopeful that this can actually happen if they keep spending time and resources on it.

We talk to men about the violence, give them all the evidence they need, and it’s still like trying to drill a hole through a brick wall. I could just as easily take a more passive approach when talking to men and cut them some slack because patriarchy and masculinity do cause men suffering, but last time I checked, emotionally and psychologically mature adults don’t ignore or gloss over the hard truths. Instead those hard truths need to be faced, and men have no excuse to stay passive on this.

Genuine alliance with women means prioritizing the goals of liberation as they are articulated by women and for women, no matter the insecurity and defensiveness men may feel.

As a radical political person of color, I do not accept surface-level activism against white supremacy and privilege. I see the impact of racist oppression in and on my community every single day, and it would be antithetical to my interest in the preservation of my people to avoid engaging with racist culture on a radical level. The oppression of my people needs to end by any means necessary, and this includes the end of the social construction of race.

I wrote an article critiquing white backlash against militant anti-racism, and of course I received still more white backlash. I believe that some white people will agree with me and I hope this is true for pro-feminist alliance with women as well.

Even at my young age I feel that I have spent a long time trying to find the right way to tell men the truth of the widespread violence that women face, but it seems as though the violence is only increasing. I can only imagine the road that some of the women here have walked and the frustration they feel in seeing the violence continue and grow exponentially.

It’s too much. The radical analysis is needed. The situation is urgent and getting worse by the day and I feel like it oftentimes takes so long to educate men and get them to do something, anything.

Some have said to me that I’m impatient. I say I’m fed up. So many men have sided with the violence of this culture and have made themselves the enemy of women and their genuine liberation. And this is pretty simple to me – if a man is an enemy of women, then he is an enemy of mine. Men need to be told, regardless of whether or not they want to hear it, that nothing less than the complete dismantling of patriarchy is acceptable, and men who don’t declare their allegiance to women have sided with the oppressors and they should be treated as such.

Men must try and understand what it takes to become real allies – constant self-critique, checking our privilege, and becoming mindful and aware of when our socialization is causing us to behave in abusive ways. We need to deconstruct this socialized person we’ve been conditioned to become and discover who we are as human beings.

I’ve been told that ultimately men aren’t ready to make comprehensive personal and political changes and to dismantle male culture, and I say so what? It’s ridiculous to think how many men will reject the simple suggestion that they try to become decent human beings. You can’t argue with a person like that. Meanwhile, women are raped on public transportation while the driver looks on and does nothing. A girl is raped in class and the teacher does nothing about it. Women are locked in basements for a decade, or enslaved or beaten or killed. At what point do we as men admit that men hate women and want to harm them?

When do we as men prioritize the safety, integrity and autonomy of women and give men the ultimatum: either you’re with women or you’re against them.

If you want to look at this from the perspective of approaching men in a way that encourages them to engage with us, rather than shutting down and ignoring us, then I can understand that. Sometimes you need to meet people where they are so you can increase the chance of them actually listening and considering what you have to say. This is a long process and oftentimes it takes several intense conversations on these issues with the same men over a period of time to get it to click. Sadly, we don’t always have that kind of time, and most men wouldn’t take the time anyway.

I think it’s important to focus our efforts on constantly engaging and challenging men on their abuse and misogyny and demonstrating to men who insist on continuing that abuse that they will be met with resistance. We will put an end to their abuse using whatever means we have to. They are the ones who cannot be reasoned with, and force is the only language they understand.

A crucial aspect of genuine alliance with women is that it’s our responsibility to educate other men, not women’s responsibility. Saying it’s a women’s issue ignores the perpetrator. It is unfair to leave this work to women who daily endure the onslaught of patriarchal violence. Women have a right to organize away from men, and to demand that we take responsibility for our actions. No, most of us men did not ask for this kind of world. And no, most of us didn’t play an integral part in constructing it. But because we are socialized into it as members of the dominant class; because we are conditioned to use our genitals as weapons against women; and because we are rewarded for doing so, we must do the hard work of separating ourselves from this unfortunate set of affairs and confronting men who refuse to do the same. What do we value more—privilege or justice? Privilege may be comfortable for a while, maybe even for a long time, but eventually it results in the same kind of horrible state of affairs that the planet is currently enduring.

I have had some success presenting this issue to men in the following manner: what does it mean to live in a culture so oppressive to women that they have a good reason to hate us? What does it mean for us that every woman with whom we come into contact can legitimately consider us a potential rapist or batterer? Is this the kind of world we want to live in— a world in which every relationship we have with women is fraught with the anxiety of being perceived as violent simply for being a man? Personally, I do not want to live in this kind of world.

Men need to be given the radical perspective, or else we are simply training them to be ineffective in addressing the problem we claim to care so much about. Just as in radical environmentalism where we base strategy and tactics on the numbers we have so we can be most effective with those numbers, we should do the same with radical pro-feminist education of men. We leverage force against male supremacy and teach each other how to become more complete human beings, how to build loving and nurturing communities, and how to abandon the pathology central to our abuse. This work hasn’t ever been and won’t ever be easy, but it’s necessary and we have a planet and its community of life to save.

Time is short. We should not be prepared to accept any more of this violence. We have a responsibility to ourselves, our loved ones, and future generations to end the violence or die trying.

Thank you.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 28, 2013 | Gender

By John Stoltenberg

This article was originally published by Feminist Current, and is republished here with permission from the author.

I understand—I really do—why a lot of people raised to be a man are seeking a gendered sense of self that is separate and distinct from all that has been called out lately as toxic masculinity. These days a penised person* would have to be really clueless not to notice all the manhood-proving behaviors that have been critiqued as hazardous to well-being (one’s own and others’). However much that penised person accepts the mounting critique of standard-issue masculinity, he might reasonably be wondering what manhood-authenticating behaviors are exempt from it: What are the ways to “act like a man” that definitively keep one from being confused with “men behaving badly”? Or, put more personally: What exactly does one do nowadays to inhabit a male-positive gendered identity that feels—and is—worthy of respect (by oneself and others)?

At the same time—as if in an alternate universe—there are legions of people raised to be a man who have been exposed to the criticism of masculinity but are rejecting and resisting the critique with all their might, almost at a cellular level, the way a body’s immune system generates antibodies to fend off an invading infection. For these penised people, criticism of any masculinity is experienced as an attack on all masculinity. Simmering resentment, eruptive anger, and backlash are but a few symptoms of their abreaction. What’s going on inside—where they feel their authentic “This is who I am”—is a life-and-death struggle against what they perceive portends personal annihilation.

For the sake of clarity, I’ll name these two characterizations Reformers and Conservers. Of course these are not the only segments of the penised population. But I’m going to assume they are both prominent enough that most readers will recognize them in broad outline. And I’m going to assume, further, that most readers place some sort of valuation on these two personas. One is better than the other, most readers are probably thinking. One is Good Guy and one is Bad Guy. And no matter whether you believe that Reformers are the real good guys or Conservers are the real good guys, what will likely be on your mind is that one does a superior job of “doing masculinity” while the other does an inferior job.

Notice how the better-than/worse-than categorization scheme comes mentally into play? It kicks in like a habit whenever one’s acculturated higher cortex is presented with any question having to do with manhood. The brain has been conditioned since childhood to perceive the social gender identity manhood through a lens of better than/worse than. It’s how we all learned to experience the identity, and it’s how we all know to recognize “who’s the man there.” It’s also how some of us embody credible manhood if and when we can, and it’s what all of us try to keep safe from if and when we can’t. Because this interior superior/inferior typology is intractably linked to interactional cognition of the gender identity manhood, it’s no wonder that neither Resisters nor Conservers get round to thinking about the template very critically.

But we must do that. We actually must. Our lives depend upon it.

For reasons implicit in my opening paragraph about Reformers, the notion of “healthy masculinity” has caught on in many circles the past few years. People convene about it, organize and workshop about it, tweet and blog about it, and in general work conscientiously at making the concept mean something viable and valuable that will fill an emptiness in Reformers’ lives—the yawning void left when, beginning a few decades ago, “He acts just like a man” began to shift from laudatory to derogatory.

Conservers, of course, don’t think there’s anything unwell about masculinity at all. And they definitely believe that masculinity ought not be impugned—as, in truth, it is—by the expression “healthy masculinity.” Imagine how a patient in a cancer ward would feel if a newly enlightened roommate began rejoicing about having healthy cancer. Probably offended. Maybe pissed off. Similarly a Conserver will never be persuaded that the masculinity he aspires to and embodies is unhealthy, or an affliction of some sort. Instead, the Conserver will regard the innuendo of “healthy masculinity” as itself a form of life-threatening attack.

Now, call me crazy, but I don’t see much long-term promise in talking only to Reformers or only to Conservers. And I certainly see no advantage in sending a message—“healthy masculinity”—that is sure to exacerbate the gender anxiety of anyone who doesn’t believe that subscribing to analog masculinity somehow makes a person sick. Shutting off communications with Conservers from the get-go by talking of “healthy and unhealthy masculinity” is at best vain and counterproductive and at worst inflammatory. Numerically Conservers represent a lot of penised people; they probably represent more than Reformers, who are still a minority inside the Conserver-dominant culture. But besides being a triggering turnoff to Conservers, there’s an even bigger problem with talking of “healthy masculinity”: It’s based on a well-meaning but ultimately faulty premise. It’s not the right fix for the problem. It’s actually a “cure” that reinvigorates a “disease.”

Many folks of goodwill want whatever’s wrong with the social gender identity manhood to be fixed comprehensively. Their hope is that the fix will avert all those male-gender-identity flare-ups that are well known to cause collateral damage. They want to live in a world where there is no need to be afraid of someone simply because they were born penised and socialized to be a man. In short, they want more harmony among human beings than we are presently accustomed to on the planet.

But here’s the rub: Any movement or campaign to remedy manhood cannot itself replicate the better-than/lesser-than oneupsmanship upon which—inside everyone’s head—manhood is definitionally predicated. Every time our acculturated brains want to identify certain penised people who are “doing masculinity” superiorly, we are reactivating the same mental scripts that were imprinted in us when we watched, or participated in, our earliest mano-a-mano fights. Someone was the victor. Someone was the loser. That was the way we learned the meaning of “manhood.” And that winner/loser, dominant/subordinate definitional prototype does not just vanish into thin air.

Instead we have to figure out a way to retrain brains, and reframe what the problem is precisely. To explain what I mean, I’m going to digress a bit and talk about what’s known as bystander-intervention training.

Basically bystander-intervention training is a program to equip penised people with communication skills, empathy, emotional intelligence, relational tactics, and a sense of personal agency to intervene when they see another penised person about to commit a sexual assault. Bystander-intervention training is widely regarded as one of the most effective means of primary sexual-assault prevention in social situations such as bars and parties where there are likely to be observers.

A big part of the program is teaching trainees (who tend to be Reformers) how to address one or several other penised people (often but not always Conservers) in a way that will effectively interrupt a probable assault-in-progress, create an exit option for a probable victim, and—here’s the tricky part—not precipitate a cockfight with the probable perp.

There are many worthy aspects of bystander-intervention training but the one I want to focus on is this: It is practice acting out of one’s moral agency without trying to prove one’s manhood. This is a discipline that is learnable, replicable, and rememberable. One reason a trainee knows the discipline is important is that he knows darn well what will happen if he does try to prove his manhood in such a situation: The contretemps will turn to combat of one sort or another, because the very act of trying to demonstrate one’s own manhood vis-à-vis another penised person will fuel the other person’s manhood-demonstrating responses (which are fired up already, as evidenced by the sexual-assault-in-progress).