by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 3, 2019 | Movement Building & Support

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Those in power do not hesitate to assault, imprison, torture, and sometimes murder those who fight capitalism, patriarchy, racism, the murder of the planet, and other elements of global empire.

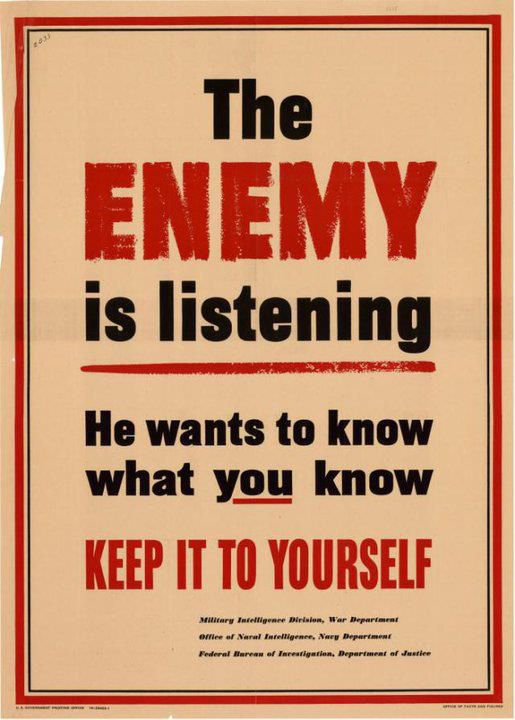

In order to do this, they need information. State agencies, private military corporations, investigators, and far-right reactionaries want to gather as much information on revolutionaries as possible. The information they want includes where you live, who you associate with, where you go, where you work, and more.

Protection of information is therefore critical to survival and effectiveness of resistance movements. This becomes even more important when you’re engaged in high-risk revolutionary work and direct action.

Militaries around the world use a procedure called operational security (OPSEC) to protect important information. While I am opposed to all imperialist militaries, we can and should learn from our adversaries. Therefore, I am writing this article to help keep you safe and make you more effective.

What is OPSEC?

OPSEC is defined as “the protection of information that, if available to an adversary, would be detrimental to you/your mission.” Implementing OPSEC is essential for revolutionaries and activists, and can also be valuable for many other people, including:

- Women facing stalking, sexual violence, or abuse

- Immigrants seeking to avoid persecution, detention, and deportation

- People of color threatened by racist persecution and violence

- Prominent individuals facing doxing and harassment

The 5-step OPSEC process

In Army Regulation 530-1, the US military defines a 5-step process for operational security. This procedure should be studied and implemented by all activists and revolutionaries. In fact, we should practice OPSEC at all times, in all situations. Rather than fostering paranoia, this allows us to ensure maximum safety based on a realistic assessment of threats and vulnerabilities.

Step 1: Identify the information you want to protect

The first step in the OPSEC procedure is the simplest. Determine which information you want to protect. This may include:

- Plans

- Procedures

- Relationships

- Locations

- Timing

- Communications

- Purchases

Step 2: Analysis of threats

The second step is to develop a “threat model.” In other words, determine who you need to protect this information from, and what their capabilities are. Then assess how these capabilities may impact you in the particular situation at hand.

In this stage, you should also ask yourself “what information does the adversary already know? Is it too late to protect sensitive information?” If so, determine what course of action you need to take to mitigate the issue, plan for ramifications, and prevent it from happening again.

You can learn about the capabilities of state agencies and private intelligence companies from the following sources:

Step 3: Analysis of vulnerabilities

Now that you know what you need to protect, and what the threats are, you can identify specific vulnerabilities.

For example, if you are trying to protect location information from state agencies and corporations, carrying a cell phone with you is a specific vulnerability, because a cell phone triangulates your location and logs this information with the service provider each time it connects to cell towers. If this phone is linked to you, your location will be regularly recorded anytime your cell phone is connected to cell towers. This process can be repeated to identify multiple vulnerabilities.

Once you have determined these vulnerabilities, you can begin to draft OPSEC measures to mitigate or eliminate the vulnerability. There are three types of measures you can take.

- Action controls eliminate the potential vulnerability itself. EXAMPLE: get rid of your cell phone completely.

- Countermeasures attack the enemy data collection using camouflage, concealment, jamming, or physical destruction. EXAMPLE: use a faraday bag to store your phone, and only remove it from the bag in specific non-vulnerable locations that you are not concerned about having recorded. NB: This method may not eliminate all dangerous data tracking, as smartphones are capable of tracking and recording location and movement data using their built-in compass and accelerometer, even when they have no access to GPS, cellular networks, or other radio frequencies.

- Counter analysis confuses the enemy via deception and cover. EXAMPLE: give your phone to a trusted friend who is moving to a different location so that your tracked location appears different than your real location during a given period.

Step 4: Assessment of risk and countermeasures

Step four is to conduct an in-depth analysis of which OPSEC countermeasures are appropriate to protect which pieces of information. Decide on the cost-benefit ratio of each countermeasure. You want to ensure that your security measures are strong and adequate, but ideally, they should not hamper the mission itself. Determine which factors are most important and make a judgement call about your course of action.

Step 5: Apply your OPSEC countermeasures

The final step is to put the plan into action. Implement your chosen action controls, countermeasures, or counter analysis methods.

Once the operation is complete, or on an ongoing basis, you should also reassess effectiveness. Conduct research, analyze any mistakes you have made, and plan for the ramifications of these mistakes. Then improve your techniques and repeat the process.

Creating a “security culture”

Operational security does not make sense for everyone. It is designed to protect groups of people engaged in high-risk activities. Therefore, OPSEC is not a hobby or something to be practiced occasionally. The OPSEC procedure should be habitual and regular, because it only takes a short period of inattention to accidentally disclose information that can have dangerous consequences.

The lessons in this article need to be combined with general activist “security culture.” and basic forensic countermeasures (a topic I will cover in another article) to protect us from threats.

It is important that we begin to shift our culture of activism towards revolutionary confrontation. This requires a serious shift in attitude. We need to look at ourselves as warriors in a life-and-death war for the future of the planet. OPSEC provides us with a procedure for increasing our safety and reminds us to treat this struggle as seriously as it really is.

—

Max Wilbert is a third-generation organizer who grew up in Seattle’s post-WTO anti-globalization and undoing racism movement, and works with Deep Green Resistance. He is the author of two books.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 8, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

by Andrew Nikiforuk / Local Futures

By now you have probably read about the so-called “tech backlash.” Facebook and other social media have undermined what’s left of the illusion of democracy, while smartphones damage young brains and erode the nature of discourse in the family. Meanwhile computers and other gadgets have diminished our attention spans along with our ever-failing connection to reality.

The Foundation for Responsible Robotics recently created a small stir by asking if “sexual intimacy with robots could lead to greater social isolation.” What could possibly go wrong?

The average teenager now works about two hours of every day – for free – providing Facebook and other social media companies with all the data they need to engineer young people’s behavior for bigger Internet profits. Without shame, technical wonks now talk of building artificial scientists to resolve climate change, poverty and, yes, even fake news.

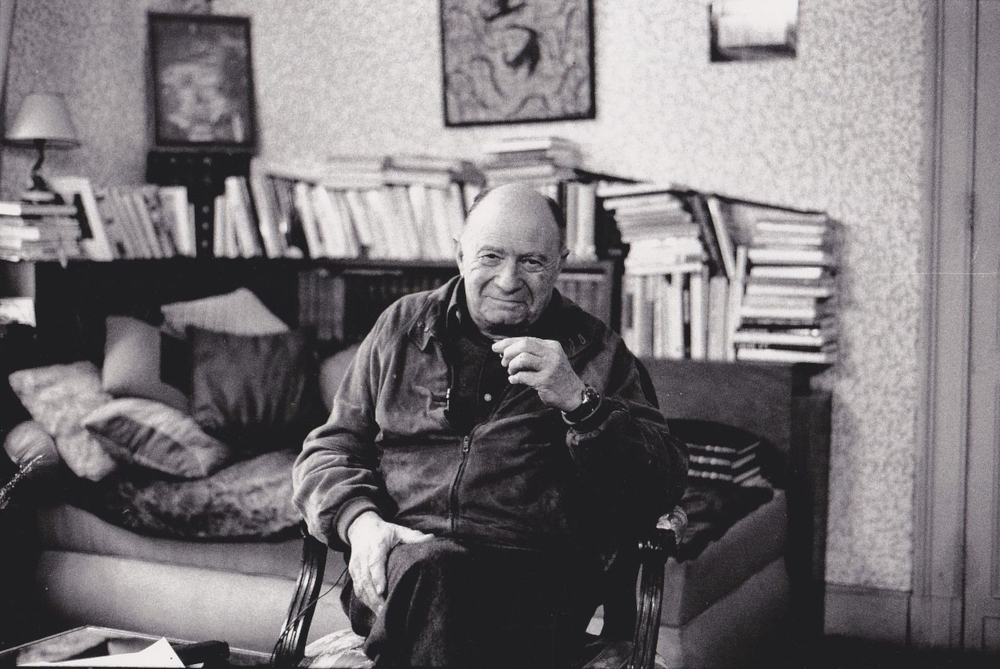

The media backlash against Silicon Valley and its peevish moguls, however, typically ends with nothing more radical than an earnest call for regulation or a break-up of Internet monopolies such as Facebook and Google. The problem, however, is much graver, and it is telling that most of the backlash stories invariably omit any mention of technology’s greatest critic, Jacques Ellul.

The ascent of technology

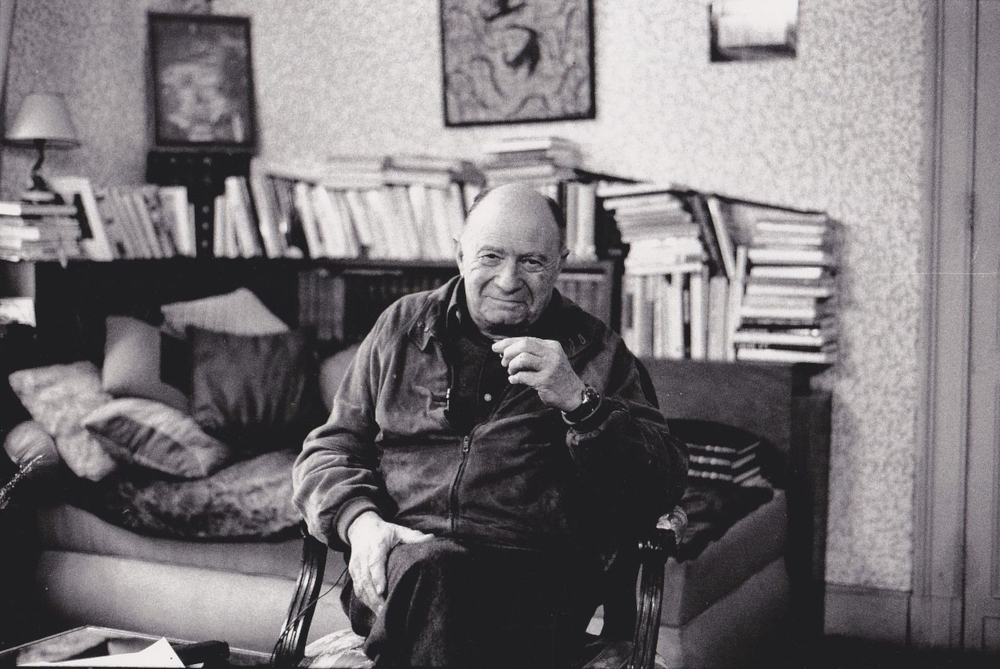

Ellul, the Karl Marx of the 20th century, predicted the chaotic tyranny many of us now pretend is the good and determined life in technological society. He wrote of technique, about which he meant more than just technology, machines and digital gadgets but rather “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency” in the economic, social and political affairs of civilization.

For Ellul, technique, an ensemble of machine-based means, included administrative systems, medical tools, propaganda (just another communication technique) and genetic engineering. The list is endless because technique, or what most of us would just call technology, has become the artificial blood of modern civilization. “Technique has taken substance,” wrote Ellul, and “it has become a reality in itself. It is no longer merely a means and an intermediary. It is an object in itself, an independent reality with which we must reckon.”

Just as Marx deftly outlined how capitalism threw up new social classes, political institutions and economic powers in the 19th century, Ellul charted the ascent of technology and its impact on politics, society and economics in the 20th. My copy of Ellul’s The Technological Society has yellowed with age, but it remains one of the most important books I own. Why? Because it explains the nightmarish hold technology has on every aspect of life, and also remains a guide to the perplexing determinism that technology imposes on life.

Until the 18th century, technical progress occurred slowly and with restraint. But with the Industrial Revolution it morphed into something overwhelming – due in part to population, cheap energy sources and capitalism itself. Since then it has engulfed Western civilization and become the globe’s greatest colonizing force. “Technique encompasses the totality of present-day society,” wrote Ellul. “Man is caught like a fly in a bottle. His attempts at culture, freedom, and creative endeavor have become mere entries in technique’s filing cabinet.”

Ellul, a brilliant historian, wrote like a physician caught in the middle of a plague or physicist exposed to radioactivity. He parsed the dynamics of technology with a cold lucidity. Yet you’ve probably never heard of the French legal scholar and sociologist despite all the recent media about the corrosive influence of Silicon Valley. His relative obscurity has many roots. He didn’t hail from Paris, but rural Bordeaux. He didn’t come from French blue blood; he was a “meteque.” He didn’t travel much, criticized politics of every stripe and was a radical Christian.

But in 1954, just a year before American scientists started working on artificial intelligence, Ellul wrote his monumental book, The Technological Society. This dense and discursive work lays out in 500 pages how technique became for civilization what British colonialism was for parts of 19th-century Africa: a force of total domination.

Ellul didn’t regard technology as inherently evil; he just recognized that it was a self-augmenting force that engineered the world on its terms. Machines, whether mechanical or digital, aren’t interested in truth, beauty or justice. Their goal is to make the world a more efficient place for more machines. Their proliferation, combined with our growing dependence on their services, inevitably led to an erosion of human freedom and unintended consequences in every sphere of life.

Ellul was one of the first to note that you couldn’t distinguish between bad and good effects of technology. There were just effects and all technologies were disruptive. In other words, it doesn’t matter if a drone is delivering a bomb or book or merely spying on the neighborhood, because technique operates outside of human morality: “Technique tolerates no judgment from without and accepts no limitations.”

Facebook’s mantra “move fast and break things” epitomizes the technological mindset. But some former Facebook executives such as Chamath Palihapitiya belatedly realized they have engineered a force beyond their control. (“The short-term dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works,” Palihapitiya has said.) That, argued Ellul, is what technology does. It disrupts and then disrupts again with unforeseen consequences, requiring more techniques to solve the problems created by the last innovation. As Ellul noted back in 1954, “History shows that every technical application from its beginnings presents certain unforeseeable secondary effects which are more disastrous than the lack of the technique would have been.”

Ellul also defined the key characteristics of technology. For starters, the world of technique imposes a rational and mechanical order on all things. It embraces artificiality and seeks to replace all natural systems with engineered ones. In a technological society a dam performs better than a running river, a car takes the place of pedestrians – and may even kill them – and a fish farm offers more “efficiencies” than a natural wild salmon migration.

There is more:

- Technique automatically reduces actions to the “one best way.”

- Technical progress is self-augmenting: it is irreversible and builds with a geometric progression. (Just count the number of gadgets telling you what to do or where to go or even what music to play.)

- Technology is indivisible and universal because everywhere it goes it shows the same deterministic face with the same consequences.

- It is autonomous, by which Ellul meant that technology has become a determining force that “elicits and conditions social, political and economic change.”

The role of propaganda

The French critic was the first to note that technologies build upon each other and therefore centralize power and control. New techniques for teaching, selling things or organizing political parties also required propaganda. Here again Ellul saw the future. He argued that in a technological society, propaganda had to become as natural as breathing air because it was essential that people adapt to the disruptions of a technological society. “The passions it provokes – which exist in everybody – are amplified. The suppression of the critical faculty – man’s growing incapacity to distinguish truth from falsehood, the individual from the collectivity, action from talk, reality from statistics, and so on – is one of the most evident results of the technical power of propaganda.” Faking the news may have been a common practice on Soviet radio during Ellul’s day, but it is now a global phenomenon leading us towards what Ellul called “a sham universe.”

We now know that algorithms control every aspect of digital life and have subjected almost aspect of human behavior to greater control by techniques, whether employed by the state or the marketplace. But in 1954 Ellul saw the beast emerging in infant form. Technology, he wrote, can’t put up with human values and “must necessarily don mathematical vestments. Everything in human life that does not lend itself to mathematical treatment must be excluded… Who is too blind to not see that a profound mutation is being advocated here?”

He also warned about the promise of leisure provided by the mechanization and automatization of work. “Instead of being a vacuum representing a break with society,” our leisure time will be “literally stuffed with technical mechanisms of compensation and integration.” Good citizens today now leave their screens at work only to be guided by robots in their cars that tell them the most efficient route to drive home. At home another battery of screens awaits to deliver entertainments and distractions, including apps that might deliver a pizza to the door. Stalin and Mao would be impressed – or perhaps disappointed – that so much social control could be exercised with such sophistication and so little bloodletting.

Ellul wasn’t just worried about the impact of a single gadget such as the television or the phone but “the phenomenon of technical convergence.” He feared the impact of systems or complexes of techniques on human society and warned the result could only be “an operational totalitarianism.” “Convergence,” he wrote, “is a completely spontaneous phenomenon, representing a normal stage in the evolution of technique.” Social media, a web of behavioral and psychological systems, is just the latest example of convergence. Here psychological techniques, surveillance techniques and propaganda have all merged to give the Russians and many other groups a golden opportunity to intervene in the political lives of 138 million North American voters.

Social media has achieved something novel, according to former Facebook engineer Sam Lessin. For the first time ever a political candidate or party can “effectively talk to each individual voter privately in their own home and tell them exactly what they want to hear… in a way that can’t be tracked or audited.” In China the authorities have gone one step further. Using the Internet the government can now track the movements of every citizen and rank their political trustworthiness based on their history of purchases and associations.

The Silicon Valley moguls and the digerati promised something less totalitarian. They swore that social media would help citizens fight bad governments and would connect all of us. Facebook, vowed the pathologically adolescent Mark Zuckerberg, would help the Internet become “a force for peace in the world.” But technology obeys its own rules and prefers “the psychology of tyranny.”

The digerati also promised that digital technologies would usher in a new era of decentralization and undo what mechanical technologies have already done: centralize everything into big companies, big boxes and big government. Technology assuredly fragments human communities, but in the world of technique centralization remains the norm. “The idea of effecting decentralization while maintaining technical progress is purely utopian,” wrote Ellul.

Towards ‘hypernormalization’

It is worth noting that the word “normal” didn’t come into currency until the 1940s, along with technological society.

In many respects global society resembles the Soviet Union just prior to its collapse, when “hypernormalization” ruled the day. A recent documentary defined what hypernormalization did for Russia: it “became a society where everyone knew that what their leaders said was not real, because they could see with their own eyes that the economy was falling apart. But everybody had to play along and pretend that it was real because no one could imagine any alternative.”

In many respects technology has hypernormalized a technological society in which citizens exercise less and less control over their lives every day and can’t imagine anything different. If you are growing more anxious about our hypernormalized existence and are wondering why you own a phone that tracks your every movement, then read The Technological Society. Ellul believed that the first act of freedom a citizen can exercise is to recognize the necessity of understanding technique and its colonizing powers. Resistance, which is never futile, can only begin by becoming aware and bearing witness to the totalitarian nature of technological society.

To Ellul, resistance meant teaching people how to be conscious amphibians, with one foot in traditional human societies, and to purposefully choose which technologies to bring into their communities. Only citizens who remain connected to traditional human societies can see, hear and understand the disquiet of the smartphone blitzkrieg or the Internet circus. Children raised by screens and vaccinated only by technology will not have the capacity to resist, let alone understand, this world any more than someone born in space could appreciate what it means to walk in a forest.

Ellul warned that if each of us abdicates our human responsibilities and leads a trivial existence in a technological society, then we will betray freedom. And what is freedom but the ability to overcome and transcend the dictates of necessity?

In 1954, Ellul appealed to all sleepers to awake. Read him. He remains the most revolutionary, prophetic and dangerous voice of this or any century.

This essay originally appeared in The Tyee, and republished by Local Futures. Republished with permission of Local Futures. For permission to repost this or any other Local Futures blog, please contact them directly at info@localfutures.org

Andrew Nikiforuk has written about energy, economics and the West for a variety of Canadian publications including The Walrus, Maclean’s, Canadian Business, The Globe and Mail, Chatelaine, Georgia Straight, Equinox and Harrowsmith. His latest book is The Energy of Slaves: Oil and the New Servitude.

Photo by Jan van Boeckel, ReRun Productions, Creative Commons licensed (CC BY-SA 4.0).

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 30, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

We live in a surveillance state. As the Edward Snowden leaks and subsequent reporting has shown, government and private military corporations regularly target political dissidents for intelligence gathering. This information is used to undermine social movements, foment internecine conflict, discover weaknesses, and to get individuals thrown in jail for their justified resistance work.

As the idea of the panopticon describes, surveillance creates a culture of self-censorship. There aren’t enough people at security agencies to monitor everything, all of the time. Almost all of the data that is collected is never read or analyzed. In general, specific targeting of an individual for surveillance is the biggest threat. However, because people don’t understand the surveillance and how to defeat it, they subconsciously stop themselves from even considering serious resistance. In this way, they become self-defeating.

Surveillance functions primarily by creating a culture of paranoia through which the people begin to police themselves.

This is a guide to avoiding some of the most dangerous forms of location tracking. This information is meant to demystify tracking so that you can take easy, practical steps to mitigating the worst impacts. Activists and revolutionaries of all sorts may find this information helpful and should incorporate these practices into daily life, whether or not you are involved in any illegal action, as part of security culture.

About modern surveillance

We are likely all familiar with the extent of surveillance conducted by the NSA in the United States and other agencies such as the GCHQ in Britain. These organizations engage in mass data collection on a global scale, recording and storing every cell phone call, text message, email, social media comment, and other form of data they can get their hands on.

Our best defenses against this surveillance network are encryption, face-to-face networking and communication, and building legitimate communities of trust based on robust security culture.

Capitalism has expanded surveillance to every person. Data collection has long been big business, but the internet and smartphones have created a bonanza in data collection. Corporations regularly collect, share, buy, and sell information including your:

- Home address

- Workplace

- Location tracking data

- Businesses you frequent

- Political affiliations

- Hobbies

- Family and relationship connections

- Purchasing habits

- And much more

Much of this information is available on the open marketplace. For example, it was recently reported that many police departments are purchasing location records from cell phones companies such as Verizon that show a record of every tower a given cell phone has connected to. By purchasing this information from a corporation, this allows police to bypass the need to receive a warrant—just one example of how corporations and the state collaborate to protect capitalism and the status quo.

Forms of location tracking

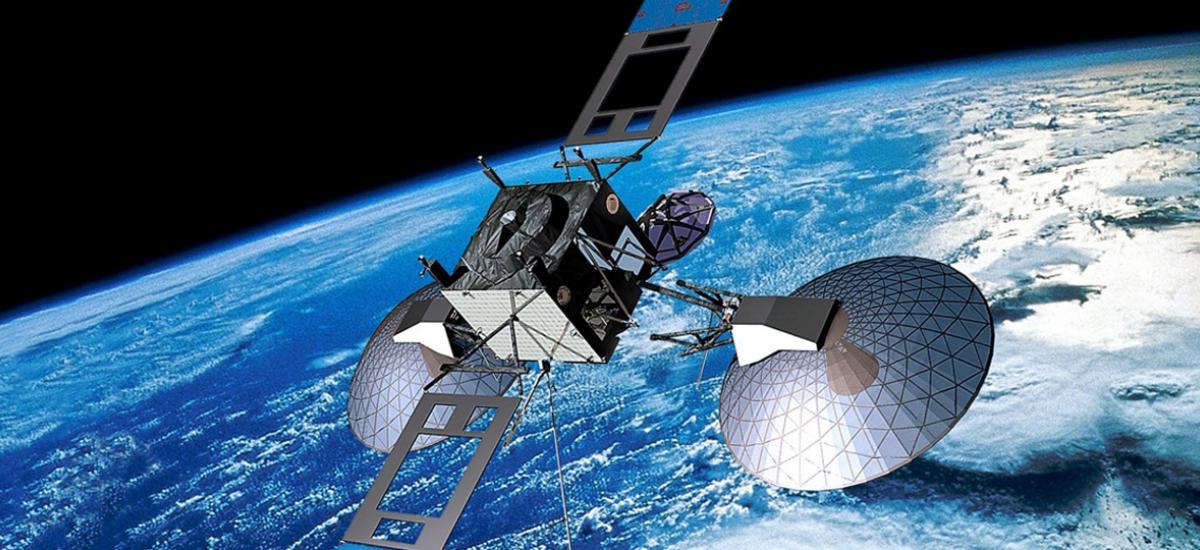

There are two main types of location tracking we are going to look at in this article: cell tower tracking and GPS geolocation.

Cell phone tracking

Whenever a cell phone connects to a cell tower, a unique device ID number is transmitted to the service provider. For most people, their cell phone is connected directly to their identity because they pay a monthly fee, signed up using their real name, and so on. Therefore, any time you connect to a cell network, your location is logged.

The more cell towers are located in your area, the more exact your location may be pinpointed. This same form of tracking applies to smartphones, older cell phones, as well as tablets, computers, cars, and other devices that connect to cell networks. This data can be aggregated over time to form a detailed picture of your movements and connections.

GPS tracking

Many handheld GPS units are “receiver only” units, meaning they can only tell you where you are located. They don’t actually send data to GPS satellites, they only passively receive data. However, this is not the case with all GPS devices.

For example, essentially every new car that is sold today includes built-in GPS geolocation beacons. These are designed to help you recover a stolen car, or call for roadside assistance in remote areas.

Additionally, many smartphones track GPS location data and store that information. The next time you connect to a WiFi or cell phone network, that data is uploaded and shared to external services. GPS tracking can easily reveal your exact location to within 10 feet.

Defeating location tracking

So how do we stop these forms of location tracking from being effective? There are five main techniques we can use, all of which are simple and low-tech.

(a) Don’t carry a cell phone. It’s almost a blasphemy in our modern world, but this is the safest way for activists and revolutionaries to operate.

(b) Use “burner” phones. A “burner” is a prepaid cell phone that can be purchased using cash at big-box stores like Wal-Mart. In the USA, only two phones may be purchased per person, per day. If it is bought with cash and activated using the Tor network, a burner phone cannot typically be linked to your identity.

WORD OF CAUTION: rumor has it that the NSA and other agencies run sophisticated voice identification algorithms via their mass surveillance networks. If you are in a maximum-security situation, you may need to use a voice scrambler, only use text messages, or take other precautions. Also note that burners are meant to be used for a short period of time, then discarded.

(c) Remove the cell phone battery. Cell phones cannot track your location if they are powered off. However, it is believed that spy agencies have the technical capability to remotely turn on cell phones for use as surveillance devices. To defeat this, remove the battery completely. This is only possible with some phones, which brings us to method number four.

(d) Use a faraday bag. A faraday bag (sometimes called a “signal blocking bag”) is made of special materials that block radio waves (WiFi, cell networks, NFC, and Bluetooth all are radio waves). These bags can be purchased for less than $50, and will block all signals while your phones or devices are inside. These bags are often used by cops, for example, to prevent remote wiping of devices in evidence storage. If you are ever arrested with digital devices, you may notice the cops place them in faraday bags.

WORD OF CAUTION: Modern smartphones include multiple sensors including a compass and accelerometer. There have been proof-of-concept experiments showing that a smartphone inside a faraday bag can still track your location by using these sensors in a form of dead reckoning. In high-security situations where you may be targeted individually, this is a real consideration.

(e) Don’t buy any modern car that includes GPS. Note that almost all rental cars contain GPS tracking devices as well. Any time a person is traveling for a serious action, it is safest to use an older vehicle. If you may be under surveillance, it is best to use a vehicle that is not directly connected to you or to the movement.

Conclusion

There are caveats here. I am not a technical expert, I am merely a revolutionary who is highly concerned about mass surveillance. Methods of location tracking are always evolving. And there are many methods.

This article doesn’t, for example, discuss the simple method of placing a GPS tracker on a car. These small magnetic devices can be purchased on the private market and attached to the bottom of any vehicle.

However, these basic principles can be applied across a wide range of scenarios, with some modification, to greatly increase your privacy and security.

Good luck!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 23, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

We live inside an unprecedented surveillance state. Government and corporations monitor all non-encrypted digital communications for the purposes of political control and profit.

Political dissidents who wish to challenge capitalism need to learn to use more secure methods for communication, research, and other digital tasks. This guide is aimed at serious dissidents and revolutionaries. It is not aimed at the everyday activist, who will likely find these practices to be overkill.

Privacy vs. Security

It is important to understand that privacy and security are two different things. Privacy is related to anonymity. Security protects from eavesdropping, but does not necessarily anonymize.

To use an analogy: privacy means that the government doesn’t know who sent the message, but can read the contents. Security means they know who sent the message, but cannot read it. This is a simplified understanding, but it’s important to distinguish between the two.

In general, most aboveground activists who are already operating in the public sphere prioritize security. Underground operators and revolutionaries generally prioritize anonymity, since being unmasked and identified is the primary danger. Of course, this is a generalization. Both security and privacy are important for anyone involved in anti-capitalist resistance.

Note that these tools require some relatively advanced technological skills. However, it’s worth learning to use these tools. Whonix is probably the easiest to use for a beginner.

Operating Systems

An operating system, or OS, is the basic software running on a computing device. Windows and Mac OS are the most common operating systems. However, Linux is the most secure family of operating systems. This guide will look at operating systems for desktop computer use.

The following information is copied from the websites for these projects.

TAILS

Tails is a live system that aims to preserve your privacy and anonymity. It helps you to use the Internet anonymously and circumvent censorship almost anywhere you go and on any computer but leaving no trace unless you ask it to explicitly.

It is a complete operating system designed to be used from a USB stick or a DVD independently of the computer’s original operating system. It is Free Software and based on Debian GNU/Linux.

Tails comes with several built-in applications pre-configured with security in mind: web browser, instant messaging client, email client, office suite, image and sound editor, etc.

Tails relies on the Tor anonymity network to protect your privacy online:

- all software is configured to connect to the Internet through Tor

- if an application tries to connect to the Internet directly, the connection is automatically blocked for security.

Tor is an open and distributed network that helps defend against traffic analysis, a form of network surveillance that threatens personal freedom and privacy, confidential business activities and relationships, and state security.

Tor protects you by bouncing your communications around a network of relays run by volunteers all around the world: it prevents somebody watching your Internet connection from learning what sites you visit, and it prevents the sites you visit from learning your physical location.

Using Tor you can:

- be anonymous online by hiding your location,

- connect to services that would be censored otherwise;

- resist attacks that block the usage of Tor using circumvention tools such as bridges.

To learn more about Tor, see the official Tor website, particularly the following pages:

- Tor overview: Why we need Tor

- Tor overview: How does Tor work

- Who uses Tor?

- Understanding and Using Tor — An Introduction for the Layman

Using Tails on a computer doesn’t alter or depend on the operating system installed on it. So you can use it in the same way on your computer, a friend’s computer, or one at your local library. After shutting down Tails, the computer will start again with its usual operating system.

Tails is configured with special care to not use the computer’s hard-disks, even if there is some swap space on them. The only storage space used by Tails is in RAM, which is automatically erased when the computer shuts down. So you won’t leave any trace on the computer either of the Tails system itself or what you used it for. That’s why we call Tails “amnesic”.

This allows you to work with sensitive documents on any computer and protects you from data recovery after shutdown. Of course, you can still explicitly save specific documents to another USB stick or external hard-disk and take them away for future use.

https://tails.boum.org/

Whonix

Whonix is a desktop operating system designed for advanced security and privacy. Whonix mitigates the threat of common attack vectors while maintaining usability. Online anonymity is realized via fail-safe, automatic, and desktop-wide use of the Tor network. A heavily reconfigured Debian base is run inside multiple virtual machines, providing a substantial layer of protection from malware and IP address leaks. Commonly used applications are pre-installed and safely pre-configured for immediate use. The user is not jeopardized by installing additional applications or personalizing the desktop. Whonix is under active development and is the only operating system designed to be run inside a VM and paired with Tor.

Whonix utilizes Tor’s free software, which provides an open and distributed relay network to defend against network surveillance. Connections through Tor are enforced. DNS leaks are impossible, and even malware with root privileges cannot discover the user’s real IP address. Whonix is available for all major operating systems. Most commonly used applications are compatible with the Whonix design.

https://www.whonix.org/

Qubes OS

Qubes OS is a security-oriented operating system (OS). The OS is the software that runs all the other programs on a computer. Some examples of popular OSes are Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, Android, and iOS. Qubes is free and open-source software (FOSS). This means that everyone is free to use, copy, and change the software in any way. It also means that the source code is openly available so others can contribute to and audit it.

Why is OS security important?

Most people use an operating system like Windows or OS X on their desktop and laptop computers. These OSes are popular because they tend to be easy to use and usually come pre-installed on the computers people buy. However, they present problems when it comes to security. For example, you might open an innocent-looking email attachment or website, not realizing that you’re actually allowing malware (malicious software) to run on your computer. Depending on what kind of malware it is, it might do anything from showing you unwanted advertisements to logging your keystrokes to taking over your entire computer. This could jeopardize all the information stored on or accessed by this computer, such as health records, confidential communications, or thoughts written in a private journal. Malware can also interfere with the activities you perform with your computer. For example, if you use your computer to conduct financial transactions, the malware might allow its creator to make fraudulent transactions in your name.

Aren’t antivirus programs and firewalls enough?

Unfortunately, conventional security approaches like antivirus programs and (software and/or hardware) firewalls are no longer enough to keep out sophisticated attackers. For example, nowadays it’s common for malware creators to check to see if their malware is recognized by any signature-based antivirus programs. If it’s recognized, they scramble their code until it’s no longer recognizable by the antivirus programs, then send it out. The best of these programs will subsequently get updated once the antivirus programmers discover the new threat, but this usually occurs at least a few days after the new attacks start to appear in the wild. By then, it’s too late for those who have already been compromised. More advanced antivirus software may perform better in this regard, but it’s still limited to a detection-based approach. New zero-day vulnerabilities are constantly being discovered in the common software we all use, such as our web browsers, and no antivirus program or firewall can prevent all of these vulnerabilities from being exploited.

How does Qubes OS provide security?

Qubes takes an approach called security by compartmentalization, which allows you to compartmentalize the various parts of your digital life into securely isolated compartments called qubes.

This approach allows you to keep the different things you do on your computer securely separated from each other in isolated qubes so that one qube getting compromised won’t affect the others. For example, you might have one qube for visiting untrusted websites and a different qube for doing online banking. This way, if your untrusted browsing qube gets compromised by a malware-laden website, your online banking activities won’t be at risk. Similarly, if you’re concerned about malicious email attachments, Qubes can make it so that every attachment gets opened in its own single-use disposable qube. In this way, Qubes allows you to do everything on the same physical computer without having to worry about a single successful cyberattack taking down your entire digital life in one fell swoop.

Moreover, all of these isolated qubes are integrated into a single, usable system. Programs are isolated in their own separate qubes, but all windows are displayed in a single, unified desktop environment with unforgeable colored window borders so that you can easily identify windows from different security levels. Common attack vectors like network cards and USB controllers are isolated in their own hardware qubes while their functionality is preserved through secure networking, firewalls, and USB device management. Integrated file and clipboard copy and paste operations make it easy to work across various qubes without compromising security. The innovative Template system separates software installation from software use, allowing qubes to share a root filesystem without sacrificing security (and saving disk space, to boot). Qubes even allows you to sanitize PDFs and images in a few clicks. Users concerned about privacy will appreciate the integration of Whonix with Qubes, which makes it easy to use Tor securely, while those concerned about physical hardware attacks will benefit from Anti Evil Maid.

How does Qubes OS compare to using a “live CD” OS?

Booting your computer from a live CD (or DVD) when you need to perform sensitive activities can certainly be more secure than simply using your main OS, but this method still preserves many of the risks of conventional OSes. For example, popular live OSes (such as Tails and other Linux distributions) are still monolithic in the sense that all software is still running in the same OS. This means, once again, that if your session is compromised, then all the data and activities performed within that same session are also potentially compromised.

How does Qubes OS compare to running VMs in a conventional OS?

Not all virtual machine software is equal when it comes to security. You may have used or heard of VMs in relation to software like VirtualBox or VMware Workstation. These are known as “Type 2” or “hosted” hypervisors. (The hypervisor is the software, firmware, or hardware that creates and runs virtual machines.) These programs are popular because they’re designed primarily to be easy to use and run under popular OSes like Windows (which is called the host OS, since it “hosts” the VMs). However, the fact that Type 2 hypervisors run under the host OS means that they’re really only as secure as the host OS itself. If the host OS is ever compromised, then any VMs it hosts are also effectively compromised.

By contrast, Qubes uses a “Type 1” or “bare metal” hypervisor called Xen. Instead of running inside an OS, Type 1 hypervisors run directly on the “bare metal” of the hardware. This means that an attacker must be capable of subverting the hypervisor itself in order to compromise the entire system, which is vastly more difficult.

Qubes makes it so that multiple VMs running under a Type 1 hypervisor can be securely used as an integrated OS. For example, it puts all of your application windows on the same desktop with special colored borders indicating the trust levels of their respective VMs. It also allows for things like secure copy/paste operations between VMs, securely copying and transferring files between VMs, and secure networking between VMs and the Internet.

How does Qubes OS compare to using a separate physical machine?

Using a separate physical computer for sensitive activities can certainly be more secure than using one computer with a conventional OS for everything, but there are still risks to consider. Briefly, here are some of the main pros and cons of this approach relative to Qubes:

Pros

- Physical separation doesn’t rely on a hypervisor. (It’s very unlikely that an attacker will break out of Qubes’ hypervisor, but if one were to manage to do so, one could potentially gain control over the entire system.)

- Physical separation can be a natural complement to physical security. (For example, you might find it natural to lock your secure laptop in a safe when you take your unsecure laptop out with you.)

Cons

- Physical separation can be cumbersome and expensive, since we may have to obtain and set up a separate physical machine for each security level we need.

- There’s generally no secure way to transfer data between physically separate computers running conventional OSes. (Qubes has a secure inter-VM file transfer system to handle this.)

- Physically separate computers running conventional OSes are still independently vulnerable to most conventional attacks due to their monolithic nature.

- Malware which can bridge air gaps has existed for several years now and is becoming increasingly common.

(For more on this topic, please see the paper Software compartmentalization vs. physical separation.)

Get Qubes

Qubes OS is free to use, can run , and integrates with Whonix for secure web browsing and internet usage via Tor.

https://www.qubes-os.org/

Summary

- TAILS is a “live” OS that runs from a USB stick or DVD, and can be used to browse anonymously from any computer. It doesn’t save files or history; it is designed mainly for ephemeral use.

- Whonix is an OS made to run as a virtual machine, and provide security and anonymity for web browsing by routing all connections via the Tor browser.

- Qubes OS is made to use as a permanent OS, and uses compartmentalization for security. Whonix is automatically installed inside Qubes. Used by Edward Snowden.

Image: Chris, https://www.flickr.com/photos/44730926@N07/32681532676, CC BY 2.0

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 15, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

Featured image: JD Lasica, Flickr, c.c. 2.0

by Steven Gorelick / Local Futures

Tucked within the pages of the January issue of the Agriview, a monthly farm publication published by the State of Vermont, was a short survey from the Department of Public Service (DPS). Described as an aid to the Department in drafting their “Ten Year Telecom Plan”, the survey contains eight questions, the first seven of which are simple multiple-choice queries about current internet and cell phone service at the respondent’s farm. The final question is the one that caught my eye:

“In what ways could your agriculture business be improved with better access to cell signal or higher speed internet service?”

Two things are immediately revealed by this question:

(a) The DPS believes that the only possible outcome from faster and better telecommunication access is that things will be “improved.”

(b) If you disagree with the DPS on point (a), they don’t want to hear about it.

A cynic might conclude that the DPS is only looking for survey results that justify decisions they’ve already made, and that’s probably true. But the department’s upbeat, one-dimensional outlook on technological change is actually the accepted norm in America. In his book In the Absence of the Sacred, Jerry Mander points out that new technologies are usually introduced through “best-case scenarios”: “The first waves of description are invariably optimistic, even utopian. This is because in capitalist societies early descriptions of new technologies come from their inventors and the people who stand to gain from their acceptance.” [1]

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have made an art of utopian hype. Microsoft founder Bill Gates, one of high-tech’s most influential boosters, gave us such platitudes as “personal computers have become the most empowering tool we’ve ever created,”[2] and my favorite, “technology is unlocking the innate compassion we have for our fellow human beings.”[3]Other prognosticators include Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who informs us that social media is “making the world more transparent” and “giving everyone a voice.” Needless to say, Gates, Zuckerberg and many others have become billionaires thanks to the public’s embrace of the technologies they touted.

The DPS survey reveals another shortcoming in how we look at technology: we tend to evaluate technologies solely in terms of their usefulness to us personally. Jerry Mander put it this way: “When we use a computer we don’t ask if computer technology makes nuclear annihilation more or less possible, or if corporate power is increased or decreased thereby. While watching television, we don’t think about the impact upon the tens of millions of people around the world who are absorbing the same images at the same time, nor about how TV homogenizes minds and cultures… If we have criticisms of technology they are usually confined to details of personal dissatisfaction.”

The DPS survey demonstrates this narrow focus: it only asks how faster telecommunications will affect the respondent’s “agriculture business”, while broader impacts – on family and community, on society as a whole and on the natural world – are out of bounds. A narrow focus is especially problematic when it comes to digital technologies, because the benefits they offer us as individuals – ultra-fast communication, the ability to access entertainment and information from all over the world – are so obvious that they can blind us to broader and longer-term impacts.

Recently, though – despite decades of hype and a continuing barrage of advertising –cracks are beginning to appear in the pro-digital consensus. The illusion that technology “unlocks compassion for our fellow human beings” has become harder to maintain in the face of what we now know: digital technologies are the basis for smart bombs, drone warfare and autonomous weaponry; they enable governments to conduct surveillance on virtually everyone, and allow corporations to gather and sell information about our habits and behavior; they permit online retailers to destroy brick-and-mortar businesses that are integral to healthy local economies.

We’ve also learned that social media doesn’t just enable us to connect with family and friends, it also provides a powerful recruitment tool for extremist groups – from neo-Nazis and white supremacists to ISIS. And all but the most die-hard Trump supporters acknowledge that social media was used to disrupt the democratic process in 2016, and that it is effectively used by authoritarian political leaders all over the world – including Mr. Trump – to spread false information and “alternative facts.”

People are even beginning to see that social media is not all that “empowering” for the individual. We recognize the addictive nature of internet use, though most of us don’t yet take it seriously: a friend will say, “I’m totally addicted to Facebook!” and we’ll just laugh. But it’s not a laughing matter: according to The American Journal of Psychiatry, “Internet addiction is resistant to treatment, entails significant risks, and has high relapse rates.”[4]The risks are highest among the young: a study of 14-24 year-olds in the UK found that social media “exacerbate children’s and young people’s body image worries, and worsen bullying, sleep problems and feelings of anxiety, depression and loneliness.”[5] Not surprisingly, a 2017 study in the US found that the suicide rate among teenagers has risen in tandem with their ownership of smartphones.[6]

Little of this should have been surprising within the digital design world. Facebook’s founding president, Sean Parker, now admits that the company knew from the start that they were creating an addictive product, one aimed at “exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” [7] Nir Eyal, corporate consultant and author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, acknowledges that “the technologies we use have turned into compulsions, if not full-fledged addictions… just as their designers intended.”[8]

These addictions have serious consequences not just for the individual, but for society as a whole: “The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works. No civil discourse, no cooperation, misinformation, mistruth.” This is not the opinion of some left-leaning Luddite, but Facebook’s former vice-president for user growth, Chamath Palihapitiya.[9]

Digital technologies are a threat to democracy in ways that go deeper than even Vladimir Putin might hope. According to former Google strategist James Williams, “The dynamics of the attention economy are structurally set up to undermine the human will. If politics is an expression of our human will… then the attention economy is directly undermining the assumptions that democracy rests on.”[10]

There is also evidence that a child’s use of computers negatively affects their neurological development.[11] Tech insiders like Sean Parker may not know for certain “what it’s doing to our children’s brains,” but Parker isn’t taking any chances: “I can control my kids’ decisions, which is that they’re not allowed to use that shit.”[12] Lots of other Silicon Valley technologists are keeping their children away from screens, in part by sending them to private schools that prohibit the use of smartphones, tablets and laptops.[13] Meanwhile, the companies they work for continue to push their addictive products onto children worldwide: Alphabet, Google’s parent corporation, provides “free” tablets to public elementary schools, while Facebook recently launched a new app called Messenger Kids – aimed specifically at pre-teens.[14]

Much of the “best case scenario” for digital technology rests on its supposed environmental benefits (remember the “paperless society”?) But illusions about “clean” technology are dissolving in the horrific toxic wasteland of Boatou, China, where rare earth metals – needed for almost all digital devices – are mined and processed.[15] Another dirty secret is the cumulative energy demand of all these technologies: it’s estimated that within the next couple of years, internet-connected devices will consume more energy than aviation and shipping; by 2040 they will account for 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions – about the same proportion as the United States today.[16]

What does all this mean for ordinary citizens? For one, we need to begin looking beyond the immediate convenience that technologies offer us as individuals, and consider their broader impacts on community, society and nature. We should remain highly skeptical about the utopian claims of those who stand to profit from new technologies. And, perhaps most importantly, we need to allow our own children to grow up – as long as possible – in nature and community, rather than in a corporate-mediated technosphere of digital screens. Doing so will require us to challenge school boards and administrators who have been sold on the idea that putting elementary school children in front of screens is the best way to “prepare them for the future.”

As for the Department of Public Service, my survey response will say that the costs of improved telecom access would far outweigh the benefits. It would be of no consequence to my farm business, which by design only involves direct sales to nearby shops and individuals. More importantly, our farm is not only an “agriculture business” it is also our home, and that’s where the impact would be greatest. Better digital access would make it easier for me and members of my family to engage in addictive behavior, from online gambling and pornography to compulsive shopping, video games and internet “connectivity” itself. It would consume the attention of my children, leaving them more vulnerable to insecurity and depression, while displacing time better spent in nature or in face-to-face encounters with friends and neighbors. There are broader impacts as well: we would be increasingly tempted to buy our needs online, thus hurting local businesses and draining money out of our local economy. And almost everything we might do online would add a further increment to the growing wealth and influence of a handful of corporations – Amazon, Google, Facebook, Apple, and others – that are already among the most powerful in the world.

These are significant impacts. But the DPS doesn’t want to hear about them.

Notes

[1] Mander, Jerry (1991) In the Absence of the Sacred, Sierra Club: San Francisco.

[2] Speech at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Feb. 24, 2004.

[3] “Bill Gates: Here’s my plan to improve our world – and how you can help”, Wired magazine, November 12, 2013

[4] Konnikova, Maria, “Is Internet Addiction a Real Thing?” The New Yorker, November 26, 2014.

[5] Campbell, Dennis, “Facebook and Twitter ‘harm young people’s mental health’”, The Guardian, May 19, 2017.

[6] “Teen suicide rate suddenly rises with heavy use of smartphones, social media,” Washington Times, Nov. 14, 2017.

[7] Solon, Olivia, “Ex-Facebook president Sean Parker: site made to exploit human ‘vulnerability’”, The Guardian, November 9, 2017.

[8] Lewis, Paul, “’Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia”, The Guardian, October 6, 2017.

[9] Wong, Julia Carrie, “Former Facebook executive: social media is ripping society apart”, The Guardian, December 12, 2017

[10] Lewis, P. op. cit.

[11] Carr, Nicholas (2010) The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, W.W. Norton.

[12] Wong, Julia Carrie, op. cit.

[13] Lewis, P. op. cit.

[14] Kircher, Madison Malone, “Facebook Releases App for Kids Under 13. What Could Possibly Go Wrong Here?” New York Magazine, December 4, 2017.

[15] Maughan, Tim, “The dystopian lake filled by the world’s tech lust”, BBC Future, April 2, 2015.

[16] “’Tsunami of data’ could consume one-fifth of global electricity by 2025”, The Guardian, December 11, 2017.