by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 8, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Weather Underground, 1969

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

The key problem with identifying successful strategies is that the context of historical resistance is different from the present. Their goals were often different as well. There’s a difference between destroying or expelling a foreign power, and forcing a power to negotiate or offer concessions, and dismantling a domestic system of power or economics. Such differences are the reason we’ve used relatively few anticolonial movements as case studies; their context and strategy are too different.

Resistance groups often fall prey to several major strategic failures. We’ll discuss five big ones here:

- A failure to adhere to the principles of asymmetric struggle.

- A failure to devise a consistent strategy and goal.

- An inappropriate excess of hope; ignoring the scope of the problem.

- A failure to adequately negotiate the relationship between aboveground and underground operations.

- An unwillingness or inability to use the required tactics.

The first of these is a failure to adhere to the principles of asymmetric struggle. Yes, most resisters want to fight the good fight, and an out-and-out fight can be tempting. But that can only happen where resisters have superior forces on their side, which is almost never. The original IRA engaged in and lost pitched battles on more than one occasion.

In occupied Europe, writes M. R. D. Foot, “whenever there was a prospect that a large partisan force could be set up, people started asking for heavy weapons” instead of the submachine guns they were usually delivered. But artillery was always short on the front lines of conventional conflict, its presence drastically cut the mobility of a resistance group, and ammunition was hard to come by. “Bodies of resisters who clamoured for artillery were victims of the fallacy of the national redoubt … and of the old-fashioned idea that a soldier should stand and fight. The irregular soldier is usually much more use to his cause if he runs away, and fights in some other time and place of his own choosing.”16

Former Black Panthers have identified a similar problem with BPP strategy, specifically with their habit of equipping offices and houses to use as pseudofortresses. Explains Curtis Austin, “Using offices inside the ghetto as bases of operations was also a mistake. As a paramilitary organization, it should not have made defending clearly vulnerable offices a matter of policy. Sundiata Acoli echoed these sentiments when he noted this policy ‘sucked the BPP into taking the unwinnable position of making stationary defenses of BPP offices.… small military forces should never adopt as a general action the position of making stationary defences of offices, homes, buildings, etc.’ The frequency and quickness with which they were surrounded and attacked should have led them to develop a policy that would have allowed them to move from one headquarters to another with speed and stealth. Instead, the fledgling group constantly found itself defending sandbagged and otherwise well-fortified offices until their limited supplies of ammunition expired.”17

Early Weather Underground and SDS strategy similarly ignored the importance of surprise in planning actions by advertising and promoting open conflicts with the state and police in advance. This was criticized by other groups at the time. Writes Ron Jacobs, “From the Yippies’ vantage point, the idea of setting a date for a battle with the state was ridiculous: it provided the police with a greater capacity to counter-attack, and it also took away the element of surprise, the activists’ only advantage.… Pointing out the differences between the planned, offensive violence of Weatherman and Yippie’s spontaneous, defensive version, Abbie Hoffman termed Weatherman’s confrontations ‘Gandhian violence for the element of purging guilt through moral witness.’ ”18 (This analysis is interesting, if perhaps surprising and a little ironic, given the Yippies’ propensity for symbolic and theatrical actions.)

A most notable example of this problem was the “Days of Rage” gathering in Chicago in 1969. According to Weatherman John Jacobs, the intent of the Days of Rage was to confront the forces of the state and “shove the war down their dumb, fascist throats and show them, while we were at it, how much better we were than them, both tactically and strategically, as a people.”19 Jacobs told the Black Panthers that 25,000 protesters would be present.20 However, only about 200 showed up, met by more than a 1,000 trained and well-equipped police. In a speech the day of the event, Jacobs changed tack and argued for the importance of fighting for righteous and moral (rather than tactical or strategic) reasons: “We’ll probably lose people today … We don’t really have to win here … just the fact that we are willing to fight the police is a political victory.”21 The protesters then started something of a riot, smashing some police cars and luxury businesses, but also miscellaneous cars, a barbershop, and the windows of lower- and middle-class homes22—not a great argument for superior strategy and tactics. The police quickly dispatched the protesters with tear gas, batons, and bullets. In the following days, almost 300 people were arrested, including most of the Weather Underground and SDS leadership. The Black Panthers—who were not afraid of political violence or of fighting the police—denounced the action as foolish and counterproductive. The Weather Underground, at least, did seem to learn from this when they went underground and used tactics better suited to an asymmetric conflict. (How effective their tactics were while underground is another question.)

All of this brings us to the second common strategic problem of resistance groups. Although their drive and values may be laudable—and although their revolutionary commitment is not in question—many resistance groups have simply failed to devise a consistent strategy and goal. In order for a strategy to be verifiably feasible, it has to have an endpoint that can be described as well as a clear and reasonable path or steps that connect the implementation of the strategy to the endpoint.

Some people call this the “A to B” factor. Does a proposed strategy actually lay out a reasonable path between point A and point B? If you can’t explain how the strategy might work or how you can implement it, you certainly can’t evaluate the strategy effectively.

It seems dead obvious when put in these terms, but a real A to B strategy is often missing in resistance groups. The problems may seem so insurmountable, the risk of group schisms so concerning, that many movements just stagger along, driven by a deep desire for justice and in some cases a need to fight back. But this leads to short-term, small-scale thinking, and soon the resisters can’t see the strategic forest for the tactical trees.

This problem is not a new one. M. R. D. Foot describes it in his writings about resistance against the Nazis in Occupied Europe. “Less well-trained clandestines were more liable to lose sight of their goal in the turmoil of subversive work, and to pursue whatever was most easy to do, and obviously exasperating to the enemy, without making sure where that most easy course would lead them.”23

It’s good and courageous to want to fight injustice, but resisters who only fight back on a piecemeal basis without a long-term strategy will lose. Often the question of real strategy doesn’t even enter into discussion. Jeremy Varon wrote in his book on the Weather Underground and the German Red Army Faction that “1960s radicals were driven by an apocalyptic impulse resting on a chain of assumptions: that the existing order was thoroughly corrupt and had to be destroyed; that its destruction would give birth to something radically new and better; and that the transcendent nature of this leap rendered the future a largely blank or unrepresentable utopia.”24 Certainly they were correct that the existing order was (and still is) thoroughly corrupt and deeply destructive. The idea that destroying it would inevitably lead to something better by conventional human standards is more slippery. But the main problem is the profound gap in terms of their strategy and objective. They had virtually no plan beyond their choice of tactics which, in the case of the Weather Underground, became largely symbolic in nature despite their use of explosives. Their uncritical “apocalyptic” beliefs about the nature of revolution—something shared by many other militant groups—almost guaranteed that they would fail to develop an effective long-term strategy, a problem to which we’ll return later on.

It’s very interesting—and hopefully illuminating—that a group like the Weather Underground did so many things right but completely fell down strategically. We keep coming back to them and criticizing them not because their actions were necessarily wrong, but because they were on the right track in so many ways. The internal organization of the Weather Underground as a clandestine group was highly developed and effective, for example. And their desire to bring the war home, their commitment to action, far surpassed that of most leftists agitating against the Vietnam War.

But as Varon observed, “The optimism of American and West German radicals about revolution was based in part on their reading of events, which seemed to portend dramatic change. They debated revolutionary strategy, and their activism in a general way suggested the nature of the liberated society to come. But they never specified how turmoil would lead to radical change, how they would actually seize power, or how they would reorganize politics, culture, and the economy after a revolution. Instead, they mostly rode a strong sense of outrage and an unelaborated faith that chaos bred crisis, and that from crisis a new society would emerge. In this way, they translated their belief that revolution was politically and morally necessary into the mistaken sense that revolution was therefore likely or even inevitable.”25

All of this brings us to a third common flaw in resistance strategy—an excess of hope. Obviously, we now know that a 1960s American revolution was far from inevitable. So why did the Weather Underground and others believe that it was? To some degree, this sort of anchorless optimism is a coping mechanism. Resistance groups are up against powerful foes, and believing that your desired victory is somehow inevitable can help morale. It can also be wrong. We should remember former prisoner of war James Stockdale’s “very important lesson”: “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”26

Another factor is what you might call the bubble or silo effect. People tend to self-sort into groups of people they have something in common with. This can lead to activists being surrounded by people with similar beliefs, and even becoming socially isolated from those who don’t share their ideas. Eventually, groupthink occurs, and people start to believe that far more people share their perspective than actually do. It’s only a short step to feeling that vast change is imminent. This is especially true if the goal is nebulous and difficult to evaluate.

The false belief that “the revolution is nigh” is hardly limited to ’60s or leftist groups, of course. Even World War II German dissidents like Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, a conservative but anti-Nazi politician, fell prey to the same misapprehension. Writes Allen Dulles: “Despite Goerdeler’s realization of the Nazi peril, he greatly overestimated the strength of the relatively feeble forces in Germany which were opposing it. Optimistic by temperament, he was often led to believe that plans were realities, that good intentions were hard facts. As a revolutionary he was possibly naïve in putting too much confidence in the ability of others to act.”27

Significantly, but perhaps not surprisingly, his naïveté extended not just to potential resisters but even to Hitler. Prior to the July 20 plot, he firmly believed that if only he could sit down and meet with Hitler, he could rationally convince him to admit the error of his ways and to resign. His friends were barely able to stop him from trying on more than one occasion, which would have obviously been foolish and dangerous to the resistance because of their planned assassination.28 Of course, Nazi Germany was not just a big misunderstanding, and after the failed putsch, Goerdeler was arrested, tortured for months by the Gestapo, and then executed.

The fourth common strategic flaw is a failure to adequately negotiate the relationship between aboveground and underground operations. We touched on this on a number of occasions in the organization section. Many groups—notably the Black Panthers—failed to implement an adequate firewall between the aboveground and underground. But we aren’t just talking about organizational partitions and separation; the history of resistance has showed again and again the larger strategic challenge of coordinating cooperative aboveground and underground action.

This has a lot to do with building mutual support and solidarity. The Weather Undeground in its early years was notably abysmal at this. Their attitude and rhetoric was aggressively militant. The organization, in the words of its own members (written after the fact), had a “tendency to consider only bombings or picking up the gun as revolutionary, with the glorification of the heavier the better,” an attitude which even alienated other armed revolutionary organizations like the BPP.29 Indeed, the Weather Underground would deliberately seek confrontation for the sake of confrontation even with people with whom it professed alignment. For example, in one action during the Vietnam War, Weather Underground members went to a working-class beach in Boston and erected a Vietcong flag, knowing that many on the beach had family in the US armed forces. When encircled, instead of discussing the war, they aggressively ratcheted up the tension, idealistically believing that after a brawl both sides could head over to the bar for a serious chat. Instead, the Weather Underground got their asses kicked.30

Now, there’s something to be said for pushing the limits of “legitimate” resistance. There’s something to be said for giving hesitant resisters a kick in the pants—or at least a good example—when they should be doing better. But that’s not what the Weather Underground did. In part the problem was their lack of a clear and articulable strategy. In his memoir, anarchist Michael Albert relates a story about being asked to attend an early Weather Underground action so that he could see what they do. “About ten of us, or thereabouts, piled into a subway car heading for the stop nearest a large dorm at Boston University. While in the subway, trundling along underground, one of the Weathermen, according to prearranged agreement, stood up on his seat to give a speech to his captive audience of other subway riders. He nervously yelled out ‘Country Sucks, Kick Ass,’ and promptly sat down. That was their entire case. It was their whole damn enchilada.”31 What are people supposed to get from that? By contrast, no one reading the Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Plan would be confused about their strategy and goals.

But the Weather Underground’s most ineffective actions in the aboveground vs. underground department were those that actually harmed aboveground organizations. Their actions in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) are a prime example. SDS was a broad-based organization with wide support, which focused on participatory democracy, direct action, and nonviolent civil disobedience for civil rights and against the war. Before the formation of the Weather Underground, a group called the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), led by Bernardine Dohrn, later a leader of the Weather Underground, essentially hijacked SDS. They gained power at a 1969 national SDS convention and expelled members of a rival faction (the Progressive Labor Party and Worker Student Alliance). They hoped to push the entire organization into more militant action, but their coup caused a split in the organization, which rapidly disintegrated in the following years. In the decades since, no leftist student organization has managed to even approach the scale of SDS.

The bottom line is that RYM took a highly functional aboveground group and destroyed it. The Weather Underground’s exaltation of militancy got in the way of radical change and caused a permanent setback in popular leftist organizing. What the Weather Underground members failed to realize is that not everyone is going to participate in underground or armed resistance, and that everyone does not need to participate in those things. The civil rights and antiwar movements were appropriate places for actionists to try to build nonviolent mass movements, where very important work was being done, and SDS was a crucial group doing that work. Aboveground and underground groups need each other, and they must work in tandem, both organizationally and strategically. It’s a major strategic error for any faction—aboveground or underground—to dismiss the other half of their movement. To arrogantly destroy a functioning organization is even worse.

There is a fifth common strategic failure, which in some ways is the most important of them all: the unwillingness or inability to apply appropriate tactics to carry out the strategy. Is your resistance movement using its entire tool chest? A resistance movement that is fighting to win considers every operation and every tactic it can possibly employ. That doesn’t mean that it actually uses every tool or tactic. But nothing is simply dismissed without consideration.

The Weather Underground, to return again to their example, was a group which began with an earnest desire to fight back, to “bring the war home,” and express genuine solidarity with the people of Vietnam and other countries under American attack by taking up arms. Initially, this was meant to include attacks on human beings in key positions in the military-industrial complex. Indeed, before they went underground, as we’ve already discussed, the Weather Underground was eager to attack even low-level representatives of the state hierarchy, specifically police. Shortly after going underground, they changed their strategy.

The turning point in the Weather Underground’s strategy of violence versus nonviolence was the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion. In the spring of 1970, an underground cell there was building bombs in preparation for a planned attack on a social event for noncommissioned officers at a nearby army base. However, a bomb detonated prematurely in the basement, killing three people, injuring two others (who fled), and destroying the house. After the explosion, the Weather Underground took what you could call a nonviolent approach to bombings—they attacked symbols of power like the Pentagon and the Capitol building, but went out of their way to case the scenes before detonation to ensure that there were no human casualties.

Rather ironically, their post–Greenwich Village tactical approach again became largely symbolic and nonviolent, much like the aboveground groups they criticized. Lacking connections to other movements and organizations, and lacking a clear strategic goal, the Weather Underground’s efforts were doomed to be ineffective.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There’s one nagging thought that always returns to me when I’m studying WWII resistance strategy: resisters in Occupied Europe were brave, even heroic, but their actions alone did not bring down the Nazis. Resisters weakened the Nazis, hampered their actions, disrupted their logistics, and destroyed materiel. But they lacked the resources and organization to decisively engage and defeat Hitler’s forces. It took a conventional military assault by the Allies to finish the job. And the overwhelming majority of this was done by the Russians, with their large army relying heavily on infantry tactics. We can speculate about whether guerrilla uprisings in occupied countries would have eventually developed and ended Nazi rule, but that’s not what happened during the actual years of occupation.

For those of us who want to stop this culture from killing the planet, there are no capital “A” Allies with vast resources and armies. That’s the nature of our predicament. We may be able to ally ourselves with powers of lesser evil, the way that Spanish Anarchists allied themselves with Spanish Republicans and Soviets in Spain, or the way antebellum abolitionists allied themselves with Union Republicans against the Confederate South. But that will only get us so far, and joining the lesser evil can be dangerous.

How, then, would a successful resistance movement expand its actions beyond resistance that merely hampers to that which decisively dismantles civilization’s centralized systems of power, those that are allowing it to steal from the poor and destroy the planet? We’ll return to this in the Core Strategy chapter, but there are three main answers in terms of any theoretical deep green resistance movement’s “allies.” One is that the depletion of finite resources, along with the dead-ending of that pyramid scheme called industrial capitalism, will provoke a cascading industrial and economic collapse. Indeed, just during the time we’ve been writing this book, we’ve seen a banking crisis turn into a major credit crisis, which has cascaded into a recession and simmering global economic crisis. That disruption will undermine the ability of those in power to exercise their influence and concentrate wealth, and generally throw industrial civilization into a state of disarray.

A second answer is ecological and climate collapse. Cheap oil has so far insulated urban industrial people from most effects of increasing and catastrophic damage to the biosphere. But industrial collapse will mean the end of that insulation, and will mean that thousands of years of civilization’s “ecological debt” will come due. Furthermore, the earth is not just a passive battlefield—it’s alive, and it’s fighting on the side of the living.

A third, more tentative answer is that as all of this transpires, less overtly militant aboveground forces may fight against those in power out of self-interest. Once those in power no longer have the “energy slaves” offered by cheap oil and industry, they will (once again) increasingly try to extract that labor from human beings, from literal slaves. Hopefully people in the minority world, where the rich and powerful minority live, will have the good sense to see that and fight back against this enslavement, as so many people in the majority world, where the impoverished minority live, have already been doing for so long. But this is a more tenuous proposition. Popular resentment may be quick to build against a particular head of state or particular political party. Developing a mass culture of resistance against an entire economic or political system, however, can take decades. People who are privileged and entitled take a long time to change, if they change at all. More likely they will side with someone who makes big but ultimately empty promises.

Good strategy is part planning and part opportunity, and success depends on the effective use of both. In his book Guerrilla Strategies: An Historical Anthology, Gérard Chaliand suggests that the lessons of revolutionary warfare in the mid-twentieth century boil down to two key points. First, he writes, “The conditions for the insurrection must be as ripe as possible, the most favorable situation being one in which foreign domination or aggression makes it possible to mobilize broad support for a goal that is both social and national. Failing this, the ruling stratum should be in the middle of an acute political crisis and popular discontent should be both intense and wide ranging.” Second, he suggests, “The most important element in a guerrilla campaign is the underground political infrastructure, rooted in the population itself and coordinated by middle-ranking cadres. Such a structure is a prerequisite for growth and will provide the necessary recruits, information, and local logistics.”15

We’re clearly heading into a period of prolonged emergency, although the crisis will vary between chronic and acute over time. That increases the prospects for revolutionary—or rather, devolutionary—struggle, especially if radical organizations are able to anticipate and effectively seize opportunities offered by particular crises. It’s unlikely that mass support will be rallied for anticivilizational causes in the foreseeable future, because most people are happy to get the material benefits of this culture and ignore the consequences. However, an increase in political discontent can be beneficial even if it doesn’t create a majority.

Chaliand’s second conclusion is key, and even I find it a bit surprising that he would rank underground development so highly. But it makes sense; aboveground organizational infrastructure, though it may be hard work, is comparatively easy to expand. Underground infrastructure seems troublesome or irrelevant in times where resistance movements are too marginal or inactive to pose a threat. But as soon as they become successful enough to provoke significant repression, the underground becomes indispensible, and creating it at that point is extremely difficult.

The use of a crisis as an opportunity isn’t a new idea, but it has played a key role in strategic theory. Napoleon Bonaparte said that “the whole art of war consists of a well-reasoned and extremely circumspect defensive followed by rapid and audacious attack.” A similar opinion was shared by British strategist Basil Liddell Hart. As a foot soldier in World War I, Liddell Hart was injured in a gas attack and became horrified by the needless bloodshed. After the war he tried to develop strategy that would avoid the kind of carnage he’d been part of. In his book Strategy: The Indirect Approach (first published in 1941), he argued for a military strategy that has a lot in common with asymmetric strategy. Rather than attempting to carry out a direct assault on enemy military forces, he recommended making an indirect and unexpected attack on the adversary’s support systems, to decisively end the war and avoid prolonged and bloody battles.

Resisters can learn from this kind of approach. Often, because of the disorganized nature of many resistance movements, initial offensive actions are tentative and poorly coordinated. Sometimes these are celebrated because, well, at least they’re something. But they are rarely effective in and of themselves, and they may tip the hand of the resistance and allow those in power to seize the initiative.

When I’m looking for an analogy for civilization, I often think of the Borg from Star Trek. Relentlessly expansionist and essentially colonial, they insist that every indigenous culture they encounter “adapt to service” them—that every individual either assimilate to their basic imperative or die. Like any coercive hegemony, they insist that resistance is futile. They’re fundamentally industrial. They have overwhelming military force, and they’re very good at adapting to resistance. The good guys only get a few shots with their phasers before the Borg adapt, making the weapons virtually useless. Then the good guys have to rejig their tactics or run away until they have a better chance.

That’s basically what happens when a resistance group makes a token attack at the wrong time. If, instead of being “rapid and audacious,” an operation is slow and timid, the effect may be to point out the enemy’s weakness and allow them to shore it up. It removes the element of surprise. And that applies whether the resistance movement is using armed tactics, sabotage, or nonviolence.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 26, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of a presentation given at the 2016 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference by DGR’s Dillon Thomson and Jonah Mix on the failure of the contemporary environmental movement to meaningfully stop the destruction of the planet. Using examples from past and current resistance movements, Mix and Thomson chart a more serious, strategic path forward that takes into account the urgency of the ecological crises we face. Part 1 can be found here, and a video of the presentation can be found here.

If you want to make a decisive strike against the industrial system, you need two things: a target and a strategy. Many organizations use the CARVER matrix as the gold standard for target selection. The United States Military has used the CARVER matrix to identify targets in every war since Vietnam. Police agencies use CARVER to target organized crime. Even CEOs use it when they are trying to buy another company. Since the American military, the police, and CEOs are kicking our asses in this struggle, we should look at what’s made them so effective.

CARVER is an acronym. It stands for Criticality, Accessibility, Recuperability, Vulnerability, Effect, and Recognizability. Criticality means, how important is the target? Accessibility: how easy is it to get to the target? Recuperability: how long will it take the system to replace or repair the target? Vulnerability: how easy is it to damage the target? Effect: how will losing the target hurt the system? Recognizability: how easy is the target to identify?

Some of these things tend to group together and others don’t. Plenty of targets may be recognizable, vulnerable, and easily accessible. Those targets aren’t usually critical, though, and they can usually be repaired easily. Examples include a Starbucks windows or a police station. Other targets are critical, almost impossible to repair, and have a massive effect, but they are hard to identify, access, and damage. These include oil refineries and hydroelectric dams.

The purpose of CARVER is to identify which target hits the most categories with the greatest impact. You will never find a target that is critical, accessible, not recuperable, vulnerable, highly effective, and recognizable, but with CARVER, you can figure out which target is most likely to succeed. The matrix is simple: you sit down with a list of targets and assign each one a score from 1 to 10 in every category. You then add up or average the scores. There are arguments about adding versus averaging, but you can do either one. You then look for which target has the highest score.

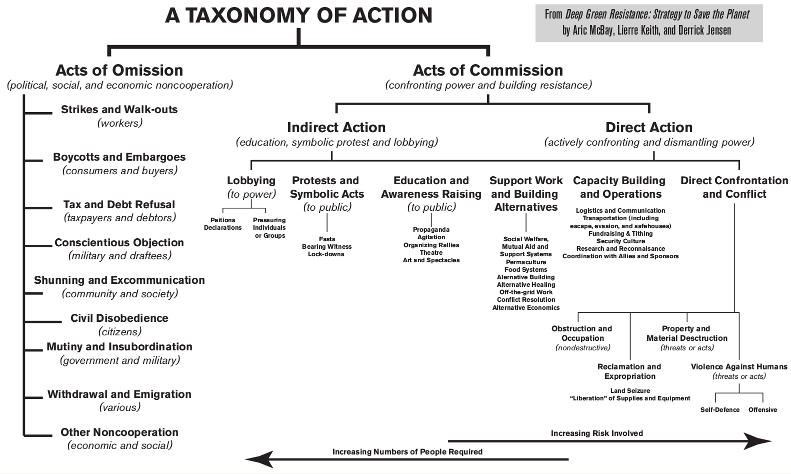

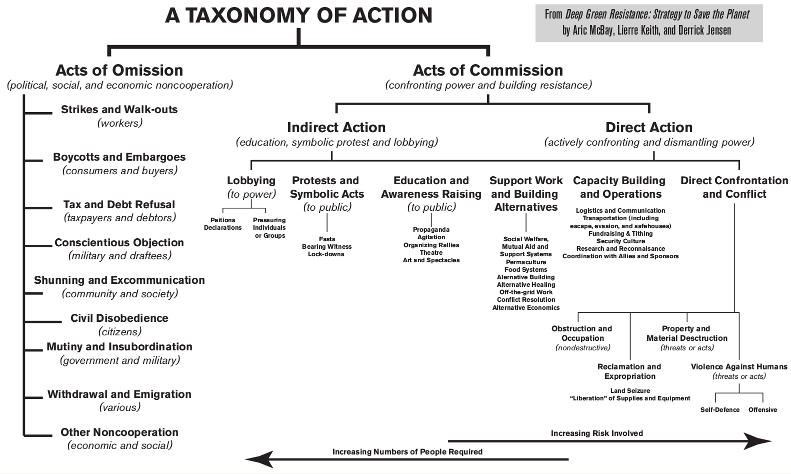

Let’s say you’ve decided on a target using CARVER. Now you need to decide what to do. DGR uses a chart called the Taxonomy of Action. The Taxonomy of Action organizes a variety of strategies and approaches that activists can against any system but especially against industrial civilization. We divided them into two categories: acts of omission (not doing something) and are acts of commission (doing something). Acts of omission are usually low-risk but require a lot of people. These include strikes, boycotts, and protests. Acts of commission require fewer people but come with greater risk.

Click for larger image

To be clear, when DGR talks about the need for offensive and underground action, the intent is not to disparage acts of omission. All of it is needed: we need boycotts, strikes, protests, workers’ cooperatives, permaculture groups, songs and plays, and more. Our movement isn’t inherently ineffective; it’s just incomplete. Many other organizations happily focus on the lower-risk acts of omission, and they are valuable. However, there is a lack of discussion about the higher-risk offensive actions. This does not mean that defensive actions aren’t valuable or that the people who do them are somehow lazy or traitorous.

There are four major categories of offensive action:

1) Obstruction and occupation;

2) Reclamation and expropriation;

3) Property and material destruction; and

4) Violence against humans.

Obstruction and occupation mean seizing a node of infrastructure and holding it, which prevents the system from using that node to extract or process resources. Reclamation and expropriation mean seizing resources from the system and putting them to our use. Property and material destruction is exactly what it sounds like: damaging the system so that it cannot be used. Defensive and offensive violence against humans is a last resort.

These four tactics work together. For example, a hypothetical underground could seize a mining outpost and reclaim explosives that are later used for material destruction. A group of aboveground activists could occupy an oil pipeline checkpoint while underground actors take the opportunity to strike at the pipeline down the road. Again, this is all strictly hypothetical. The point is that just as our movement needs both offense and defense, it also needs different kinds of offense done together in strategic pursuit of a larger goal.

This is a lot of information and it is a little abstract. The need for security culture can make it even more difficult to talk about these things as concretely as we would like. We’ve often found that the best method is to look to history to see which struggles have succeeded through the use of these tactics and how. Historical struggles have used these tactics and come out victorious. I’m going to describe two historical movements and one ongoing movement in more detail. All of these movements have utilized a broad range of tactics described in the Taxonomy of Action.

The first example is the African National Congress. The goal of the ANC was equal rights for all South Africans regardless of their ethnicity. It put pressure on the South African apartheid government to implement constitutional reform and return the freedoms denied under the apartheid regime.

Power pylons sabotaged by Umkhonto We Sizwe

From 1912 to 1960, the ANC existed as an aboveground organization. It organized strikes, boycotts, protests, demonstrations, and alternative political education. These actions were all aboveground because the ANC figured it could achieve its goals by making its activities visible to the public and the government. In 1960, though, the government enacted the Pass Laws, which required blacks to carry identification cards. The ANC had protested similar oppression before, but the Pass Laws were much more stringent.

The opposition came to a head in a town called Sharpeville, where police killed 69 protesters and injured 180 more. After the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC was deemed illegal and driven underground. In response, the militant wing of the ANC formed in 1961. It was called the Umkhonto we Sizwe or “Spear of the Nation.”

Umkhonto we Sizwe had the same goal as the ANC but a different strategy. The situation was more desperate and the ANC’s aboveground strategies hadn’t worked. Umkhonto we Sizwe decided to use guerrilla warfare to bring the South African government to the bargaining table. In the early stages, the ANC underground did most of the organization and strategy for Umkhonto we Sizwe, but Umkhonto we Sizwe later broke off and developed its own command structure.

In the early 1960s it began sabotaging government installations, police stations, electric pylons, pass offices, and other symbols of apartheid rule. In the mid-1960s through the mid-70s, Phase 2 focused on political mobilization and developing underground structures. The Revolutionary Council was established in 1969 to train military cadres as part of a long-term plan to build a robust underground network. Most of this training took place in neighboring countries. In Phase 3, from the mid-1970s to 1983, Umkhonto we Sizwe engaged in large-scale guerrilla warfare and armed attacks. It sabotaged railway lines, administrative offices, police stations, oil refineries, fuel depots, the COVRA nuclear plant, military targets, and military personnel.

When it began Phase 4 in 1983, Umkhonto we Sizwe wanted to take the war into the white areas and make it a people’s war. The Revolutionary Council was replaced by the Political Military Council, which controlled and integrated the activities of the now-numerous sections of the organization. It continued attacks on economic, strategic, and military installations in white suburbs.

The ANC and Umkhonto we Sizwe simultaneously rejected the values of the system and attacked the structure, which successfully ended apartheid. ANC’s work to promote mass political struggle combined with Umkhonto we Sizwe’s armed struggle succeeded in pressuring the apartheid government to legitimize the ANC in 1990, and South Africa held its first multiracial elections in April, 1994. Nelson Mandela became South Africa’s first black president.

Umkhonto We Sizwe combatants

Despite Nelson Mandela’s fame, his specific actions are largely unacknowledged. He had an integral role in creating Umkhonto we Sizwe. He himself organized sabotage and assassinations. Concerning these actions, Mandela himself said, “I do not deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the Whites.”

The next example is the Irish Republican Army. Its goal was the end of British rule to form a free, independent republic. Despite Irish resistance, Great Britain had colonized and oppressed the Irish people for 500 years. The IRA developed a new strategy to make the occupation impossible: guerrilla warfare.

The Irish Republican Army was the underground wing of the aboveground Sinn Féin or Irish Republican Party. The Sinn Féin formed a breakaway government and declared independence from Britain. The British government declared Sinn Féin illegal in 1919, and the need for new strategy led to the creation of the IRA, just as Umkhonto we Sizwe grew out of the ANC in South Africa. Heavy repression led to broad support for the IRA within Ireland.

The IRA operated in “flying columns” of 15 to 30 people who trained in guerrilla warfare, often up in the hills with sticks as substitutes for rifles. Its tactics included hit-and-run raids, ambushes, and assassinations. It blew up police and military bases, destroyed coast guard stations, burnt courthouses and tax collector’s offices, and killed police and military personnel.

The IRA understood that an independent Irish republic was only achievable through confrontation with the British. It chose tactics based on the available resources and training. This was an asymmetrical conflict. The IRA was an underdog against the British military, but its broad base of support provided the necessary food, supplies, safe houses, and medical aid.

Military historians have concluded that the IRA waged a highly successful campaign against the British because the British military determined that the IRA could not be defeated militarily.

Flying Column No. 2 of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade of the Old IRA, photographed in 1921

The final example of a successful movement that uses the full spectrum described by the Taxonomy of Action is the contemporary Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta or MEND. Since Nigeria’s independence from British colonial rule, multinational oil companies like Chevron and Royal Dutch Shell have enjoyed the support of successive dictators to appropriate oil from the Niger Delta. The people living in the delta have seen their way of life destroyed. Most are fishing people, but the rivers are full of oil. People have been dispossessed in favor of foreign interests and rarely see any revenue from the oil.

Here we see the same pattern that we saw in South Africa and Ireland. Over the past 20 years, the Ogoni people have led a large nonviolent civil disobedience movement in the Niger Delta. Ken Saro-Wiwa was a poet turned activist who protested the collusion between the government and the oil companies. He and eight others were executed in 1995 under what many believe were falsified charges designed to silence his opposition to the oil interests in Nigeria. In his footsteps came people who saw the government’s reaction to nonviolent activism and advocated using force to resist what they saw as the enslavement of their people.

MEND’s goals are the control of oil production/revenue for the Ogoni people and the withdrawal of the Nigerian military from the Niger Delta. It intends to reach them by destroying the capacity of the Nigerian government to export oil from the Niger Delta, which would force the multinational companies to discontinue operations and likely precipitate a national budgetary and economic crisis. Its tactic: sabotage.

MEND sabotages oil infrastructure with very few people and resources. It has resorted to bombings, theft, guerrilla warfare, and kidnapping foreign oil workers for ransom. It is organized into underground cells with a few spokespeople who communicate with international media. Leaders are always on the move and extremely cautious. They do not take telephone calls personally, knowing that soldiers hunting for them have electronic devices capable of pinpointing mobile phone signals. Fighters wear masks to protect their identities during raids, use aliases, and rely on clandestine recruitment.

MEND’s organizational structure has proven effective, and despite its small numbers and hodge-podge networking, it has been quite successful. Between 2006 and 2009, it made a cut of more than 28% in Nigerian oil output. In total, it has reduced oil output in the Niger Delta by 40%. This is an incredible number given its lack of resources.

MEND

These are just a few examples of movements that have used a broad spectrum of actions on the Taxonomy of Action chart. They demonstrate that the precedent for full-spectrum resistance has been set many times; many more groups have utilized force because they understand that those in power understand the language of force best. They tried nonviolence, asking nicely, and making concessions, but it doesn’t always work – and when it doesn’t work, this does.

This is a message that MEND sent to the Shell Oil Company: “It must be clear that the Nigerian government cannot protect your workers or assets. Leave our land while you can or die in it.” You have heard about people building bombs, picking up guns, and committing sabotage. These types of resistance are necessary if an environmental movement is to succeed like the IRA, ANC, or MEND succeeded, but this doesn’t mean that the only role in a militant struggle is either blowing something up or staying home and keeping quiet. As Lierre Keith said, “For those of us who can’t be active on the front lines – and this will be most of us – our job is to create a culture that will encourage and promote political resistance. The main tasks will be loyalty and material support.”

During the armed struggle against the British, only about 2% of people involved with the Irish Republican Army ever took up arms. For every MEND soldier, there were hundreds or even thousands of Nigerians who would help them in any way they could. The first role of an aboveground activist is underground promotion.

Underground promotion is anything that creates the conditions for an underground to develop and work effectively. There are, broadly speaking, two types of underground promotion. The first is passive promotion, which describes after-the-fact or roundabout promotion. This is all some people can safely do. You might talk about failures in the modern environmental movement, and even if you don’t suggest a militant solution, frank discussion of our situation may inspire people to look further. You can shift the culture slowly toward resistance values, and if sabotage does occur, you can support it – or if that’s not safe for you, you can at least take the opportunity to criticize the system and not those who struck against it.

If you are in a position to be more vocal, you can explicitly critique traditional environmentalist ideology. This includes critiquing pacifism or a defense-focused movement, arguing in public and among comrades for the necessity of revolutionary violence or strategic militancy, and promoting or encouraging such acts whenever possible. This is especially important after acts of sabotage or militancy do occur.

If you are an aboveground activist who takes on the project of underground promotion, or, hypothetically, an underground activist, you need to have good security culture. Security culture is a set of customs in a community that people adopt to make sure that anyone who performs illegal or sensitive action has their risks minimized and their safety supported. You are practicing security culture when you consider what you say or do in light of its potential effects on the people around you.

Security culture can be broken down into simple “dos and don’ts.” The first “do” is to keep all sensitive information on a strict need-to-know basis. This includes names, plans, past actions, and even loose ideas. Unless there is a tangible material benefit to sharing information and it can be done safely, you need to keep quiet. People bragging to their friends or getting drunk and letting a name slip have undone more radical movements than all the bullets, bombs, and prisons combined. A good way to make sure you follow this rule is to assume that you are always being monitored.

I wrote this assuming that FBI agents or police may read it. I don’t know if they will or not; they very well may not. The decision to take surveillance as a given reminds us not to say anything in public that they shouldn’t hear. That doesn’t mean we should be paranoid or always worry about who is an infiltrator or a plant, because if we are following security culture well, it shouldn’t matter. When you practice security culture well, it doesn’t make you paranoid; it frees you from paranoia.

Security culture boils down to respecting people’s boundaries and learning to establish your own. Feminism is essential to the radical struggle because patriarchy celebrates boundary breaking. Masculinity demands that men don’t respect “no” and blow past anyone who says, “I don’t want to do that” or “I don’t want to talk about that.” True security culture means that we develop the skills to say no and the skills to say nothing at all if we don’t feel safe or think that speaking will be valuable.

There’s a great article called “Misogynists Make Great Informants: How Gender Violence on the Left Enables State Violence in Radical Movements.” It’s about the role that masculine culture and macho posture can play in wrecking our movements. Boundary setting is the end-all and be-all of security culture. The best way to cultivate boundary setting in a community is to adopt a strict and central role for feminism in your movement.

“Don’ts” are even simpler: don’t ask questions that could endanger people involved in direct action. This is the flipside of need-to-know: if you don’t need to know it, don’t ask it. Even if you do need to know it, considering waiting for someone to bring it to you. If they bring it to you in a way that isn’t safe, you also need to say no.

You need to make sure that your underground promotion doesn’t cross the line into incitement. If you tell a crowd of people, “go out and blow up this dam,” or “that bridge,” you’ve crossed the line from promotion to incitement. Incitement has serious legal consequences for you or other people in the movement. You should talk to a lawyer or another experienced activist if you want to know where the line is, as it does vary state by state.

Finally, of course, don’t speak to the police or the FBI. They are not your friends. They can lie to you. If they come to you and say, “We know that someone is doing this and you need to tell us about it,” don’t trust them. You will never lose anything by asking for a lawyer and you will never gain anything by talking to the cops.

We also encourage people to avoid drugs, alcohol, and other non-political illegal activities that might compromise their ability to follow these rules. Good activists who fell into addiction or became otherwise compromised have hurt our movement.

None of us have come to our positions lightly. Most of us in the environmental movement started out as liberals. We bought the right soap, went to the right marches, and some of us even put our bodies on the line in protests and direct actions. Each one of us, for whatever reason, has come to the conclusion that this isn’t enough. We love the planet too much not to consider every option. We respectfully ask that you sit with whatever feelings you have, whether moral uncertainty, anger, or something else, and if you don’t feel in your heart that the next step needs to be taken, we don’t judge or condemn you. We need you. The struggle needs you to do one of the million other jobs that a nonviolent activist can do for this movement.

But we’d ask that you do one thing before you decide: go down to a riverbank, watch the salmon spawn, watch bison roam, look up at the sky, listen to songbirds and crickets, and ask yourself, if these people could talk, what would they ask of me? What would the pine tree cry out over the hum of the chainsaw blades? The starfish mother who is watching her babies cook to death in an acid ocean – if she could speak, what would she ask you to do? These people matter. Their lives matter, every bit as much as our lives matter to you and me. And they need us. They need us to be smart, strong, strategic, and effective.

We welcome everyone, supporters, promoters, and warriors, to move past fifty years of frustration and insufficient action toward a strategic environmental movement that will do what it takes.

I often hear people say, “I can’t handle violence, I can’t stand violence.” And I say, “I can’t stand violence either.” I can’t stand violence against indigenous people, against bison and wolves, against centipedes and snails, and against women. I can’t stand violence against the people whose lives are fodder for this system. We in DGR don’t like violence any more than you do.

If you are a human being in civilization, especially an American or a white man like me, you can’t choose between violence and nonviolence. That question was decided for me long ago; my life is based on violence. Our lives as human beings in civilization are based on violence. The question is whether we will use that violence to keep killing the world or use it to bring about something new. I encourage you to remember that there is violence out there already. It is happening to people who can’t tell us what’s going on. It happens to people whose screams we don’t hear because we aren’t listening. If you read this and say, “I just can’t handle violence,” I say welcome aboard, because we can’t handle it either.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 25, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of a presentation given at the 2016 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference by DGR’s Dillon Thomson and Jonah Mix on the failure of the contemporary environmental movement to meaningfully stop the destruction of the planet. Using examples from past and current resistance movements, Mix and Thomson chart a more serious, strategic path forward that takes into account the urgency of the ecological crises we face. Part 2 can be found here, and a video of the presentation can be found here.

For the past several thousand years, this beautiful planet has been the site of a dysfunctional relationship between civilization, the way of life characterized by the emergence and growth of cities, and the more-than-human communities that it exploits. For the vast majority of our time on earth, humans fit into the logic of whatever land base we happened to inhabit. We watched and listened, we felt, and we communicated with the land to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship. This created the conditions for our long-term survival.

Living examples of this older way of life still exist. Small-scale subsistence cultures have lived in place for thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years. Among these are the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert, the Kawahiva of the Brazilian Amazon, the Kogi of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of Columbia, and the people of the Nilgiri Hills in India. To this day, subsistence culture is the only time-tested mode of human sustainability on this planet. It is also the way of life that is being destroyed the fastest by civilization.

Civilization, which began just over ten thousand years ago in the Fertile Crescent, marks the beginning of a fundamentally different way of relating to the planet. The human element began to impose its own logic over the logic of the land. Before, human culture had been an extension of an ecosystem. Now we see our culture as separate from nature, a value system opposed to the principles and the workings of nature.

Ever since the emergence of civilization, life on earth has suffered. That’s how we know that the relationship is dysfunctional. Every living system on the planet is in decline, and the rate of decline is accelerating. Not a single peer-reviewed scientific article published in the last thirty years contradicts this statement. You shall know a tree by its fruit, and by its fruit, industrial civilization stands condemned. Or at least it should.

The fruits of civilization are the drawdown of living systems and natural vitality. We must analyze the values and behaviors that have oriented this culture against the planet.

Why should civilization stand condemned? First of all, it commits the cardinal sin: it does not benefit the land on which it is based. All beings and communities must benefit the land where they live in order to survive long-term. That is basic ecology. You have to give back as much or more than you take. Civilization is like a bad houseguest. It takes far more than its fair share and what it gives back is toxic and inedible. It values production over life. To civilization, the needs of the economic system outweigh the needs of the natural world.

The natural world can thrive without an industrial economy, but no human economy can exist without a healthy natural world. It’s embarrassing that this point must be made, but if you look at our culture’s behavior or listen to the talking heads on the radio or TV, you can quickly see we value our economic system above all else.

Our way of life requires widespread violence. This culture would quickly collapse without astounding violence against the earth, non-human communities, and members of our own species. How many people are aware that there are over 27 million human slaves today? The industrial supply chain enslaves more people today than any other period in human history.

You find slavery alive and well in the cotton in your shirt, the tantalum in your cellphone, and the beans in your cup of coffee. It is in the mines, the fields, and the raw materials processing that we don’t have to see because of our position in the supply chain. We are at the end, the “capital C” Consumers.

Professor Kevin Bales arrived at that 27 million number, which he calls the most conservative estimate for the number of slaves in the world today. It accounts for people who are forced into slavery at gunpoint and kept there by threat of direct violence to them or their families. It does not include millions more wage slaves, sweatshop laborers, and people coerced into slave-like conditions through economic hardship, usually at the hands of predatory multinational corporations.

Sweatshop, China

Our culture’s stories say that humans have the right to control and abuse the natural world. This is an issue of entitlement. Our culture feels that we are entitled to rip the tops off mountains, extract bauxite, turn it into aluminum, and make beer cans. Our culture thinks it is okay to torture animals in vivisection labs in order to make shampoo. Our culture thinks that we can exempt ourselves from the natural cycles of life and death. It believes in infinite growth on a finite planet. Our culture behaves as if it can destroy the planet and live on it too.

Violence is part of our culture and has been from the very beginning. It is part of the fabric of civilization and the fabric of our economy. Why? In part, this is due to the economic reward. Violence feeds the bottom line of business.

I have been calling the relationship between civilization and the planet dysfunctional, but it is more like a one-sided war. This goes far beyond disrespect. The behavior of this culture constitutes a form of hatred that is akin to hatred of one’s own flesh. Those who suffer the consequences of civilization are our kin, our family. How can a culture commit atrocity after atrocity against the earth and not hold a deep hatred of the natural world at its core?

In The Culture of Make Believe, Derrick Jensen writes, “Hatred felt long enough no longer feels like hatred, it feels like economics, it feels like religion, it feels like tradition.” This is hatred of our larger earth-body, our larger self, and our sense of self based upon this hatred is no more sustainable than our economy. The cultural stories that we inherit do not tell us that our flesh is continuous with the flesh of the world. Our stories don’t tell us that we are kin with the oak tree, the jaguar, and the soil.

Though scientists understand that everything is connected on a molecular level, most of their research is pressed into the service of extractive industry. Science’s stories have not led to a mutually beneficial relationship with the land. Most of the stories we receive are stories of separation. We can go back to Rene Descartes: “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes created an artificial division between mind and matter that persists today.

The stories we inherit are stories of human supremacy. They tell us that we are superior to all other life forms and that we have the right to act accordingly.

We are animals among animals. The beings and communities that we are pushing to extinction are not inferior. They are not resources and they do not exist for our use and exploitation. This is a message to the animal in all of you: this is war. Civilization has been at war with the earth for 12,000 years. This is a call to those who want to fight back strategically against civilization – and win.

The environmental movement was created to deal with the dysfunctional relationship between civilization and the natural world. It can be traced back to different starting points. Many people say that the contemporary environmental movement in the West has its roots in the Romantic movement of the 18th century. The conservation movement came in the 19th century. In the 20th century came Aldo Leopold’s land ethic, described in A Sand County Almanac. In 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring brought even greater visibility to the environmental movement.

Though it’s been more than fifty years since 1962, every living system on the planet is in decline. This decline is accelerating. Why? Many environmental groups have done good work here and there, but by and large, the environmental movement has remained a defensive movement. Our losses are permanent and our victories are often defensive and temporary. We may save a patch of forest for a few years or decades – until it gets cut down. We may save a river or watershed – until they are poisoned.

Rosa Durando lives in Florida, where she is a member of the Palm Beach Audubon Society, the County Land Use Advisory Board, the Citizens Task Force on Zoning, and the countywide Council on Beaches and Shores. She has been a full-time environmentalist worker-watchdog for the past ten years. She says, “Sometimes I feel like a total failure. Other times I tell myself I’ve done well by getting concessions. I don’t think any environmentalists are really successful. The other side is too powerful and too rich. The best we can hope for are safeguards to avoid total destruction next year.”

Durando is one of the honest few among us who speak about the uphill battle of land defense work. The one point I disagree with is that the best we can hope for is to avoid total destruction next year. DGR thinks that there is another path forward to stop the destruction entirely.

Strategies in war include both defense and offense. Defense is anything that prevents an opposing force from gaining territory, power, or resources. Maybe a developer wants to clear-cut one hundred acres of old-growth forest. You take him to court and fight to save half the land. That defensive action is valuable and good; we need everyone working as hard as they can to do things like that. In the end, though, the developer still gets fifty acres. The best possible outcome of a defensive action is that things stay the same. You cannot win a war through defense alone. This is where offensive action comes in.

Offensive action directly takes territory, resources, or power from the opposition. 99% of what industrial civilization does is offensive. It dams rivers and strip-mines mountains. It rounds up African Americans and throws them in jail. It rapes women and commits genocide. Every time the system acts it gains power, territory, or resources. With few exceptions, the system doesn’t act defensively. Without serious opposition, it doesn’t have to.

On the flipside, the environmental movement is too busy fighting defensive battles to focus on offensive gains. The contemporary environmental movement cannot conceive of an offensive campaign against ecocide. This isn’t a recipe for victory. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, one of my heroes, said, “When developers win a battle, it’s in concrete. When environmentalists with a battle, it’s only for thirty days.”

Marjory Stoneman Douglas, champion of the Florida Everglades

This quote captures the heart of the matter. The developers fight offensive battles. They are gaining territory and holding onto it. Environmentalists fight defensive battles. At best we are delaying their forward march. To be clear, we are not doing this because we are stupid, lazy, or unwilling to take risks. We’re doing it because we are up against a massive system with guns, bombs, and jails. It controls the nightly news, talk radio, schools, and everything else that prevents the environmental movement from doing more than slowing it down.

Most of us don’t have anything but a few bucks, some picket signs, our bodies, and a love for the living planet. There are strategies that not only address that inequality but also leverage it in an offensive and effective approach. One of my favorite quotations is from Malcolm X: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made.”

Malcolm X was speaking about the wound that white America and white people had inflicted on Africans, but his words also describe our violence against the earth. Slowing this violence isn’t progress; even stopping it isn’t progress. Progress would be healing the wound that the blow made. Our enemy is industrial civilization. It’s not capitalism, corporations, or even fossil fuels. These things must be done away with, but they are all expressions of a deeper problem. To end the destruction of the living world, we have to end industrial civilization itself.

Like every system, industrial civilization has two components: its structure and its values. “Structure” describes the real-world, material things that make up a system. “Values” describes the ideology invented to defend that system.

The structure of industrial civilization is clear. It includes the energy grid, extraction infrastructure, communications infrastructure, financial systems, and technology industry. All of these components work toward one of three goals: accessing resources, extracting resources, or processing resources to make them usable for industrial civilization. Everything from clear-cuts and strip-mines to police violence, genocide, and rape is about the control of resources.

Our resistance has to focus on stopping the control, extraction, and processing of resources by industrial civilization. At the center of these processes is the energy grid. Without the energy grid, you can’t spin the drills that kill mountains, run the computers that decide where the murdered mountains go, or keep the lights on in the buildings that take the murdered mountains and turn them into our cell phone batteries. Without power provided by an energy grid, industrial civilization has nothing.

Next is the extraction infrastructure, the part of the system that seizes resources. “Resources” refers to bodies, bones, and blood, living and breathing creatures – the living planet. Extraction infrastructure seizes them and grinds them up. Mining, logging, fracking, refining, and wind and solar energy are all are part of this infrastructure. Extraction infrastructure is organized by communications infrastructure, which includes phone lines, cell towers, and the internet.

Extraction and communications rely on the financial system that keeps capital flowing so that multinational corporations can invest in extraction processes. The technology industry makes extraction more efficient. The systems that enable industrial civilization are interconnected and codependent. The energy grid needs the technology industry, which needs communications. Extraction needs the energy grid and financial systems. Each system depends on the others.

In looking at this structural complexity, it is important to remember that it makes up only one component of industrial civilization. Civilization also relies on values, ideology, and stories to justify its actions. At the core of these stories is the value that industrial civilization prizes above all else: growth.

Endless expansion requires three conditions: hierarchy, stability, and efficiency. Hierarchy is the ranking of lives and communities. Industrial civilization needs hierarchy because a free and egalitarian social system would make endless expansion impossible. White supremacy, patriarchy, and human supremacy are myths central to industrial civilization because they justify the exploitation of Africans, indigenous people, Latinas and Latinos, women, and the more-than-human world.

Stability ensures a steady baseline upon which a system can expand. To cultivate stability, industrial civilization encourages comfort and ignorance. When people have refrigerated food and five hundred channels on TV, we don’t see the destruction around us – or care about it. That doesn’t mean that everyone inside industrial civilization is comfortable or ignorant. Largely, the people who are comfortable and ignorant are those at the top. Those at the bottom – the non-human world, people of color, and women – are largely aware of the violence that the system perpetrates in their lives. To stymie resistance, then, the system works to control all avenues for education and confrontation.

Finally, efficiency enables more expansion. The myth of consumerism teaches that as people buy more, the markets grow, production increases, and more production equals more growth.

The progress myth teaches that human beings arose in a state of primitivism, stupidity, and weakness – and that we are moving toward a grander design. We achieve that grander design by destroying the world around us.

Human beings aren’t moving toward a grander design any more than pigs, centipedes, or whales are moving toward a grander design. No one talks about the day when pigs or centipedes will seize control of the planet and make it better for pigs or centipedes. We like to believe the progress myth because without it, you can’t justify the destruction of the earth. This is where our culture’s love of science comes in. Advanced science is necessary to make superconductors, defoliants, and everything else that kills the planet.

Effective resistance to a system requires that you reject its values and attack its structures. It can never take place on the system’s terms. It can never leave the structure of the system in place. If there is one single flaw holding the modern environmental movement back, it’s our inability to stand firm against more than one aspect of the system at a time.

For example, I used to live in Bellingham, Washington. Bellingham is a major site of controversy over coal trains. Extraction infrastructure murders mountains across the country, packs them into trains, and carries them to the ports in Bellingham. From there they are shipped up to Vancouver and across the ocean to China to keep the lights on in factories where children sew our shoes. Smart, brave people fought back against the coal trains. But what would it talk to attack the entire extraction infrastructure?

Let’s say you defend the structure and retain the values. You call up the company that owns the port and say, “Hey, I only want union labor to unload the coal.” They probably wouldn’t listen to you, but let’s say you succeed. Unions are great, but you haven’t attacked the structure. The coal is still flowing. More importantly, you haven’t rejected the system’s values because you’ve adopted as a given that human beings have the right to ship coal at all.

Let’s say you want to attack the structure. You call up your congressperson or representative and demand that they replace coal trains with wind farms and solar panels. Again, they probably wouldn’t listen, but with enough pressure, you might slow down coal exports – and that’s great. You’ve made a hit against the structure – on the assumption that wind farms, solar panels, or electricity are justified. The system can pat you on the back and promise not to rely on coal so heavily. Then it can strip-mine a mountain, dam a river, kill just as many living creatures, and sell you a “renewable” product. The system took a hit, but with its values untouched, it recovered quickly.

If you want to reject the values of the system, you could sell your car, move into a smaller house, grow your own food, or sew your own clothes. You could condemn the entire system of industrial civilization. You could drop out and be very vocal about it – and that’s great. Even if you’ve rejected the values, though, the coal trains keep rolling. The structure remains intact.

How could one strike at coal trains in a way that rejects the concept of coal trains, wind farms, solar panels, or electricity itself? How could one do damage not only to the structure but also to the ideology that justifies it? You could take a blowtorch, crowbar, or some dynamite and destroy the rail line. Suddenly the coal trains aren’t going anywhere. More importantly, the system can’t recover on its own terms.

Loaded coal trains, Norfolk, VA, USA

Remember, industrial civilization values expansion, comfort, hierarchy, and efficiency. If you condemn coal trains because they’re wasteful and solar is more efficient, or because coal trains are noisy and solar is quiet, or because coal trains clog up transportation and solar power eliminates congestion, that’s great. The system wants efficiency. It wants comfort, so it will happily replace coal trains with something more efficient, quieter, less disruptive, and still fundamentally destructive to the earth.

But if you strike against coal trains because the very idea of a living planet is incompatible with electricity, coal trains, wind farms, or anything else that destroys the earth, you’ve given the system an ultimatum that it can’t easily escape. This is all hypothetical; I’m not telling you to blow up or destroy anything. The point isn’t that successful resistance requires bombs, it’s that it requires a hard stance against the system in its entirety. The values of industrial civilization and the values of a healthy culture that is capable of living in communion with the earth are incompatible. By pushing that contradiction instead of capitulating to the system’s values, we can strengthen our cause.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 11, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

It’s also worth looking at the principles that guide strategic nonviolence. Effective nonviolent organizing is not a pacifist attempt to convince the state of the error of its ways, but a vigorous, aggressive application of force that uses a subset of tactics different from those of military engagements.

Gene Sharp recognized this, and Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler followed Sharp’s strategic tradition in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. They understand that there is no dividing line between “violent” and “nonviolent” tactics, but rather a continuum of action. Furthermore, they also understand the need for tactical flexibility; sticking to only one tactic, such as mass demonstrations, gives those in power a chance to anticipate and neutralize the resistance strategy. In terms of strategy, they argue “that most mass nonviolent conflicts to date have been largely improvised” and could greatly benefit from greater preparation and planning.5 I would argue that the same applies to any resistance movement, regardless of the particular tactics it employs.

Having assessed the history of nonviolent resistance strategy in the twentieth century, Ackerman and Kruegler offer twelve strategic principles “designed to address the major factors that contribute to success or failure” in nonviolent resistance movements. They class these as principles of development, principles of engagement, and principles of conception.

Their principles of development are as follows:

Formulate functional objectives. The first principle is clearly important in any resistance movement using any tactics. “All competent strategy derives from objectives that are well chosen, defined, and understood. Yet it is surprising how many groups in conflict fail to articulate their objectives in anything but the most abstract terms.”6

Ackerman and Kruegler also observe that “[m]ost people will struggle and sacrifice only for goals that are concrete enough to be reasonably attainable.” As such, if the ultimate strategic goal is something that would require a prolonged and ongoing effort, the strategy should be subdivided into multiple intermediate goals. These goals help the resistance movement to evaluate its own success, grow support and improve morale, and keep the movement on course in terms of its overall strategy. This is especially important when the dominant power structure has been in control for a long time (as opposed to a recent occupier). “The tendency to view the dominant power as omnipotent can best be undermined by a steady stream of modest, concrete achievements.”7 This is especially relevant to groups that have very large, ambitious goals like abolishing capitalism, ending racism, or bringing down civilization.

Develop organizational strength. Ackerman and Kruegler write that “to create new groups or turn preexisting groups and institutions into efficient fighting organizations” is a key task for strategists.8 They also note that the “operational corps”—who we’ve been calling cadres—have to organize themselves effectively to deal with threats to organizational strength, specifically “opportunists, free-riders, collaborators, misguided enthusiasts who break ranks with the dominant strategy, and would-be peacemakers who may press for premature accommodation.”9 These threats damage morale and undermine the effectiveness of the strategy.

Secure access to critical material resources. They identify two main reasons for setting up effective logistical systems: for physical survival and operations of the resisters, and to enable the resistance movement to disentangle itself from the dominant culture so that various noncooperation activities can be undertaken. “Thought should be given, at an early stage, to controlling sufficient reserves of essential materials to see the struggle through to a successful conclusion. While basic goods and services are used primarily for defensive purposes, such other assets as communications infrastructure and transportation equipment form the underpinnings of offensive operations.”10 In particular, they suggest stockpiling communications equipment.

Cultivate external assistance. The benefits of cultivating external assistance and allies should be clear. Combating an enemy with global power requires as many allies and as much solidarity as resisters can rally.

Expand the repertoire of sanctions. The fifth principle is key because it is highly transferable. By “expand the repertoire of sanctions,” they simply mean to expand the diversity of tactics the movement is capable of carrying out effectively. They also encourage strategists to evaluate the risk versus return of various tactics. “Some sanctions can be very inexpensive to wield or can operate at very low risk. Unfortunately, such sanctions may also have a correspondingly low impact. A minute of silence at work to display resolve is a case in point. Other sanctions are grand in design, costly, and replete with risk. They also may have the greatest impact.”11

Their second group of principles consists of principles of engagement:

Attack the opponents’ strategy for consolidating control. This is specifically intended for mass movements, but essentially the authors mean to undermine the control structure of those in power, to generally subvert them, and to ensure that any repression or coercion those in power attempt to carry out is made difficult and expensive by the resistance.