by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 27, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

Despite the limitations created by their smaller numbers, resistance movements do have real strategic choices, from the loftiest overarching strategy to the most detailed tactical level. Let’s explore beyond the default palette of actions. Resisters can and must do far better than the strategy of the status quo.

There is a finite number of possible actions, and a finite amount of time, and resisters have finite resources. There are no perfect actions. Prevailing dogma puts the onus on dissenters to be “creative” enough to find a “win-win” solution that pleases those in power and those who disagree, that stops the destruction of the planet but permits the continuation of business as usual and lifestyles of conspicuous consumption. If resisters fall prey to this belief, if they accept its absurd and contradictory premises, they are engineering their own defeat before the fact. If resisters believe this, they are accepting all blame for the actions of those in power, accepting that the problems they face are theirfault for not being “innovative” enough, rather than the fault of those in power for deliberately destroying the world to enrich themselves.

At the highest strategic level, any resistance movement has several general templates from which to choose. It may choose a war of containment, in which it attempts to slow or stop the spread of the opponent. It may choose a war of disruption, in which it targets systems to undermine their power. It may choose a war of public opinion, by which to win the populace over to their side. But the main strategy of the left, and of associated movements, has been a kind of war of attrition, a war in which the strategists hope to win by slowly eroding away the personnel and supplies of the other side, thus wearing down the omnicidal power structures and public opposition to change more quickly than those forces can destroy our communities, more quickly than they can gobble up biodiversity, more quickly than they can burn the remaining fossil fuels. Of course, this strategy has been an abysmal failure.

A strategy of attrition only works when there is an indefinite amount of time to maneuver, to prolong or delay conflict. Obviously that’s not the case in the current situation, which is urgent and worsening. Furthermore, to achieve success in a war of attrition, the resistance must be able to wear down the enemy more quickly than it gets worn down; again, in the present case, those in power are not being worn down at all (except in the degree to which they are so rapidly consuming the commodities required for their own reign to continue).

Furthermore, a resistance movement fighting a war of attrition must reasonably expect that it will be in a better strategic position in the future than it is at the current time. But who genuinely believes that we—however you would define “we”—are moving toward a better strategic position? And in order to get ahead in a war of attrition, resisters would have to have more disposable resources than their opponent.

Another crucial element in a war of attrition is reliable recruitment and growth. It doesn’t matter how many enemy bridges a group takes out if the adversary can build them faster than they can be destroyed. And on every level, civilization is recruiting and growing faster than resistance forces. To keep pace, resistance fighters would have to destroy dams more quickly than they are built, get people to hate capitalism faster than children are inculcated to love it, and so on. So far, at least, that’s not happening.

Of course, we are not in a two-sided war of attrition. Those in power aren’t holding back, but have been actively attacking. And those in the resistance haven’t even been fighting a comprehensive war of attrition; it’s more like a moral war of attrition. Rather than trying to erode the material basis of power, we’ve been hoping that eventually they’ll run out of bad things to do, and perhaps then they’ll come around to our way of thinking.

A movement that wanted to win would be smarter and more strategic than that. It would abandon the strategy of moral attrition. It would identify the most vulnerable targets those in power possess. It would strike directly and decisively at their infrastructure—physical, economic, political—and do it while there is still a planet left.

Strategy and tactics form a continuum; there’s no clear dividing line between them. So the tactics available, which will be discussed in the next chapter, Tactics and Targets, guide strategy, and vice versa. But strategy forms the base. If resistance action is a tree, the tactics are spreading branches and leaves, finely divided and numerous, while the strategy is the trunk, providing stability, cohesion, and rootedness. If resisters ignore the necessity and value of strategy, as many would-be resistance groups do—they are all tactics, no strategy—then they don’t have a tree, they have loose branches, tumbleweeds blowing this way and that with changing winds.

Conceptually, strategy is simple. First understand the context: where are we, what are our problems? Then, develop the goal(s): where do we want to be? Identify the priorities. Now figure out what actions are needed to get from point A to point B. Finally, identify the resources, people, and specific operations needed to carry out those activities.

Here’s an example. Let’s say you love salmon. Here’s the context: salmon have been all but wiped out in North America, because of dams, industrial logging, industrial fishing, industrial agriculture, the murder of the oceans, and global warming. The goal is for the salmon population not only to stop declining, but to increase. The difference between a world in which salmon are being wiped out, and one in which they are thriving, comes down to those six obstacles. Overcoming them would be the priority in any successful strategy to save the salmon.

What actions must be taken to honor this priority? Remove the dams. Stop industrial forms of logging, fishing, and agriculture. Stop the massive production and dumping of plastics. Stop global warming, which means stop the burning of fossil fuels. In all these cases, existing structures and practices have to be demolished for salmon to survive, for the goal to be accomplished.4

Now it’s time to proceed to the operational and tactical side of this strategy. According to the US Army field manual, all operations fit into one of three “all encompassing” categories: decisive, sustaining, or shaping.

Decisive operations “are those that directly accomplish the task” or objective at hand. In our salmon example, a decisive operation might be taking out a dam or preventing a clear-cut above a salmon spawning stream. Decisive operations are the centerpiece of strategy.

Sustaining operations “are operations at any echelon that enable shaping and decisive operations” by offering direct support to those other operations. These supporting operations might include funding or logistical support, communications, security, or other aid and services. In the salmon example, this might mean providing transportation to people taking out a dam, bringing food to tree-sitters, or helping to research timber sale appeals. It might mean running an escape line or safehouse, or providing prisoner support.

Shaping operations “create and preserve conditions for the success of the decisive operation.” They alter the circumstances of the conflict and help bring about the conditions required for victory. Shaping operations could include carrying out a campaign on the importance of removing dams, undermining a particular logging company, or helping to develop a culture of resistance that values effective action and refuses to collaborate. However, shaping operations are not necessarily broad-based or indirect. If an allied underground cell were to attack a nearby pipeline as a distraction, allowing the main group to take out a dam, that diversionary measure would be considered a shaping operation. The lobby effort that created the Clean Water Act could even be considered a shaping operation, because it helps to preserve the conditions necessary for victory.

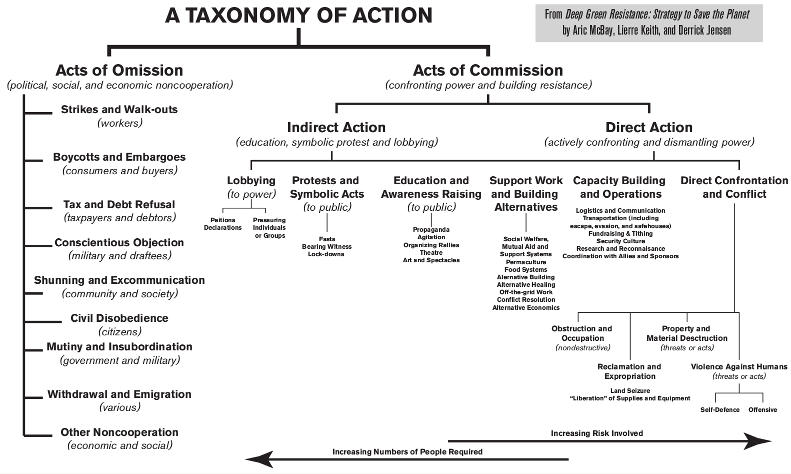

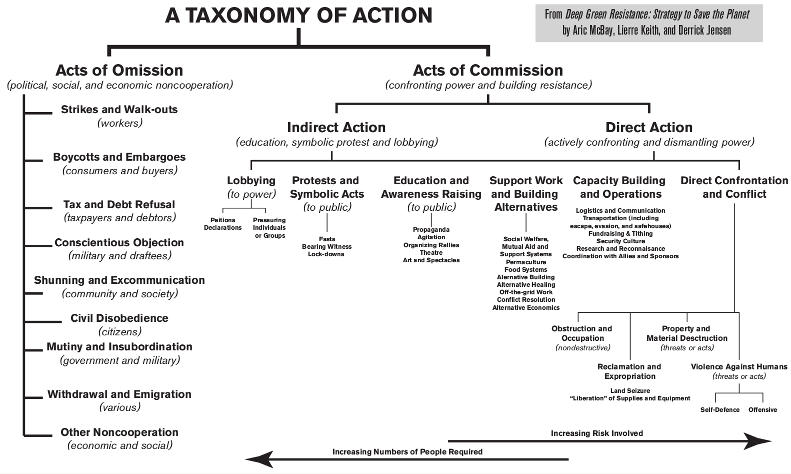

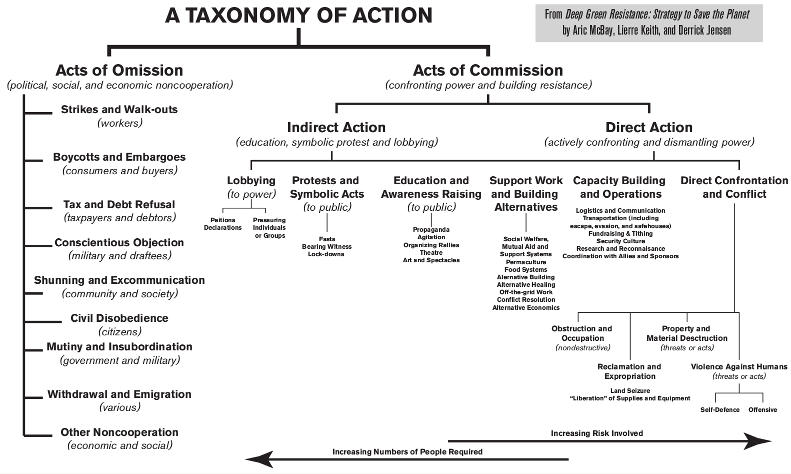

If you review the taxonomy of action chart, you’ll see that the actions on the left consist mostly of shaping operations, the actions along the center-right consist mostly of sustaining operations, and the right-most actions are generally decisive.

Click for larger image

These categories are used for a reason. Every effective operation—and hence every effective tactic—must fall into one or more of these categories. It must do one of those things. If it doesn’t—if that operation’s or tactic’s contribution to the end goal is undefined or inexpressible—then successful resisters don’t waste time on that tactic.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 24, 2018 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

“Forests precede civilizations and deserts follow them.”

– François-René de Chateaubriand

New research in the prestigious journal Nature estimates that “the global number of trees has fallen by approximately 46% since the start of human civilization.”

The study also suggests that about 15 billion trees are being cut down each year, and that the average age of forests has declined significantly over the last few thousand years.

The study was led by researchers at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies with contributions from scientists at universities and research institutions in Utah, Chile, the UK, Finland, Italy, France, Switzerland, New Zealand, The Netherlands, Germany, Czech Republic, Brazil, and China.

While fossil fuels have only been burned on a large scale for 200 years, land clearance has been a defining characteristic of civilizations – cultures based around cities and agriculture – since they first emerged around 8,000 years ago.

This land clearance has impacts on global climate. When a forest ecosystem is converted to agriculture, more than two thirds of the carbon that was stored in that forest is lost, and additional carbon stored in soils rich in organic materials will continue to be lost to the atmosphere as erosion accelerates.

Modern science may give us an idea of the magnitude of the climate impact of this pre-industrial land clearance. Over the past several decades of climate research, there has been an increasing focus on the impact of land clearance on modern global warming. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its 2004 report, attributed 17% of global emissions to cutting forests and destroying grasslands – a number which does not include the loss of future carbon storage or emissions directly related to this land clearance, such as methane released from rice paddies or fossil fuels burned by heavy logging equipment.

Some studies show that 50% of the global warming in the United States can be attributed to land clearance – a number that reflects the inordinate impact that changes in land use can have on temperatures, primarily by reducing shade cover and evapotranspiration (the process whereby a good-sized tree puts out thousands of gallons of water into the atmosphere on a hot summer day – their equivalent to our sweating).

So if intensive land clearance has been going on for thousands of years, has it contributed to global warming? Is there a record of the impacts of civilization in the global climate itself?

10,000 years of Climate Change

According to author Lierre Keith, the answer is a resounding yes. Around 10,000 years ago, humans began to cultivate crops. This is the period referred to as the beginning of civilization, and, according to the Keith and other scholars such as David Montgomery, a soil scientist at the University of Washington, it marked the beginning of land clearance and soil erosion on a scale never before seen – and led to massive carbon emissions.

“In Lebanon (and then Greece, and then Italy) the story of civilization is laid bare as the rocky hills,” Keith writes. “Agriculture, hierarchy, deforestation, topsoil loss, militarism, and imperialism became an intensifying feedback loop that ended with the collapse of a bioregion [the Mediterranean basin] that will most likely not recover until after the next ice age.”

Montgomery writes, in his excellent book Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, that the agriculture that followed logging and land clearance led to those rocky hills noted by Keith.

“It is my contention that the invention of [agriculture] fundamentally altered the balance between soil production and soil erosion – dramatically increasing soil erosion.

Other researchers, like Jed Kaplan and his team from the Avre Group at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland, have affirmed that preindustrial land clearance has had a massive impact on the landscape.

“It is certain that the forests of many European countries were substantially cleared before the Industrial Revolution,” they write in a 2009 study.

Their data shows that forest cover declined from 35% to 0% in Ireland over the 2800 years before the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The situation was similar in Norway, Finland, and Iceland, where 100% of the arable land was cleared before 1850.

Similarly, the world’s grasslands have been largely destroyed: plowed under for fields of wheat and corn, or buried under spreading pavement. The grain belt, which stretches across the Great Plains of the United States and Canada, and across much of Eastern Europe, southern Russia, and northern China, has decimated the endless fields of constantly shifting native grasses.

The same process is moving inexorably towards its conclusion in the south, in the pampas of Argentina and in the Sahel in Africa. Thousands of species, each uniquely adapted to the grasslands that they call home, are being driven to extinction.

“Agriculture in any form is inherently unsustainable,” writes permaculture expert Toby Hemenway. “We can pass laws to stop some of the harm agriculture does, but these rules will reduce harvests. As soon as food gets tight, the laws will be repealed. There are no structural constraints on agriculture’s ecologically damaging tendencies.”

As Hemenway notes, the massive global population is essentially dependent on agriculture for survival, which makes political change a difficult proposition at best. The seriousness of this problem is not to be underestimated. Seven billion people are dependent on a food system – agricultural civilization – that is killing the planet.

The primary proponent of the hypothesis – that human impacts on climate are as old as civilization – has been Dr. William Ruddiman, a retired professor at the University of Virginia. The theory is often called Ruddiman’s Hypothesis, or, alternately, the Early Anthropocene Hypothesis.

Ruddiman’s research, which relies heavily on atmospheric data from gases trapped in thick ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland, shows that around 11,000 years ago carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere began to decline as part of a natural cycle related to the end of the last Ice Age. This reflected a natural pattern that has been seen after previous ice ages.

This decline continued until around 8000 years ago, when the natural trend of declining carbon dioxide turned around, and greenhouse gases began to rise. This coincides with the spread of civilization across more territory in China, India, North Africa, the Middle East, and certain other regions.

Ruddiman’s data shows that deforestation over the next several thousand years released 350 Gigatonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, an amount nearly equal to what has been released since the Industrial Revolution. The figure is corroborated by the research of Kaplan and his team.

Around 5000 years ago, cultures in East and Southeast Asia began to cultivate rice in paddies – irrigated fields constantly submerged in water. Like an artificial wetland, rice paddies create an anaerobic environment, where bacteria metabolizing carbon-based substances (like dead plants) release methane instead of carbon dioxide and the byproduct of their consumption. Ruddiman points to a spike in atmospheric methane preserved in ice cores around 5000 years ago as further evidence of warming due to agriculture.

Destruction of the land as the root

The anti-apartheid organizer Seve Biko wrote in the 1960’s that “One needs to understand the basics before setting up a remedy. A number of organizations now currently ‘fighting against apartheid’ are working on an oversimplified premise. They have taken a brief look at what is, and have diagnosed the problem incorrectly. They have almost completely forgotten about the side effects and have not even considered the root cause. Hence whatever is improved as a remedy will hardly cure the condition.”

The same could be said of much of the modern environmental movement. While coal, oil, and gas are without a doubt worthwhile targets for opposition, the “climate” movement has forgotten the primary importance of the meadows, the grasslands, the forests, the mountains, and the rivers.

Without this, the movement has been led astray. It’s no wonder that ineffective solutions and tepid reforms that actually strengthen global empire are being promoted, instead of what is actually needed: revolutionary overthrow of this system of power.

Image: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Kate Evans/CIFOR, https://www.flickr.com/photos/cifor/35035343564

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 15, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

I do not wish to kill nor to be killed, but I can foresee circumstances in which both these things would be by me unavoidable. We preserve the so-called peace of our community by deeds of petty violence every day. Look at the policeman’s billy and handcuffs! Look at the jail! Look at the gallows! Look at the chaplain of the regiment! We are hoping only to live safely on the outskirts of this provisional army. So we defend ourselves and our hen-roosts, and maintain slavery.

—Henry David Thoreau, “A Plea for Captain John Brown”

Anarchist Michael Albert, in his memoir Remembering Tomorrow: From SDS to Life after Capitalism, writes, “In seeking social change, one of the biggest problems I have encountered is that activists have been insufficiently strategic.” While it’s true, he notes, that various progressive movements “did just sometimes enact bad strategy,” in his experience they “often had no strategy at all.”1

It would be an understatement to say that this inheritance is a huge problem for resistance groups. There are plenty of possible ways to explain it. Because we sometimes don’t articulate a clear strategy because we’re outnumbered and overrun with crises or immediate emergencies, so that we can never focus on long-term planning. Or because our groups are fractured, and devising a strategy requires a level of practical agreement that we can’t muster. Or it can be because we’re not fighting to win. Or because many of us don’t understand the difference between a strategy and a goal or a wish. Or because we don’t teach ourselves and others to think in strategic terms. Or because people are acting like dissidents instead of resisters. Or because our so-called strategy often boils down to asking someone else to do something for us. Or because we’re just not trying hard enough.

One major reason that resistance strategy is underdeveloped is because thinkers and planners who do articulate strategies are often attacked for doing so. People can always find something to disagree with. That’s especially true when any one strategy is expected to solve all problems or address all causes claimed by progressives. If a movement depends more on ideological purity than it does on accomplishments, it’s easy for internal sectarian arguments to take priority over getting things done. It’s easier to attack resistance strategists in a burst of horizontal hostility than it is to get things together and attack those in power.

The good news is that we can learn from a few resistance groups with successful and well-articulated strategies. The study of strategy itself has been extensive for centuries. The fundamentals of strategy are foundational for military officers, as they must be for resistance cadres and leaders.

PRINCIPLES OF WAR AND STRATEGY

The US Army’s field manual entitled Operations introduces nine “Principles of War.” The authors emphasize that these are “not a checklist” and do not apply the same way in every situation. Instead, they are characteristic of successful operations and, when used in the study of historical conflicts, are “powerful tools for analysis.” The nine “core concepts” are:

Objective. “Direct every military operation toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective.” A clear goal is a prerequisite to selecting a strategy. It is also something that many resistance groups lack. The second and third requirements—that the objective be both decisive and attainable—are worth underlining. A decisive objective is one that will have a clear impact on the larger strategy and struggle. There is no point in going after one of questionable or little value. And, obviously, the objective itself must be attainable, because otherwise efforts toward that operation objective are a waste of time, energy, and risk.

Offensive. “Seize, retain, and exploit the initiative.” To seize the initiative is to determine the course of battle, the place, and the nature of conflict. To give up or lose the initiative is to allow the enemy to determine those things. Too often resistance groups, especially those based on lobbying or demands, give up the initiative to those in power. Seizing the initiative positions the fight on our terms, forcing them to react to us. Operations that seize the initiative are typically offensive in nature.

Mass. “Concentrate the effects of combat power at the decisive place and time.” Where the field manual says “combat power,” we can say “force” more generally. When Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest summed up his military theory as “get there first with the most,” this is what he was talking about. We must engage those in power where we are strong and they are weak. We must strike when we have overwhelming force, and maneuver instead of engaging when we are outmatched. We have limited numbers and limited force, so we have to use that when and where it will be most effective.

Economy of Force. “Allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts.” In order to achieve superiority of force in decisive operations, it’s usually necessary to divert people and resources from less urgent or decisive operations. Economy of force requires that all personnel are performing important tasks, regardless of whether they are engaged in decisive operations or not.

Maneuver. “Place the enemy in a disadvantageous position through the flexible application of combat power.” This hinges on mobility and flexibility, which are essential for asymmetric conflict. The fewer a group’s numbers, the more mobile and agile it must be. This may mean concentrating forces, it may mean dispersing them, it may mean moving them, or it may mean hiding them. This is necessary to keep the enemy off balance and make that group’s actions unpredictable.

Unity of Command. “For every objective, ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander.” This is where some streams of anarchist culture come up against millennia of strategic advice. We’ve already discussed this under decision making and elsewhere, but it’s worth repeating. No strategy can be implemented by consensus under dangerous or emergency circumstances. Participatory decision making is not compatible with high-risk or urgent operations. That’s why the anarchist columns in the Spanish Civil War had officers even though they despised rulers. A group may arrive at a strategy by any decision-making method it desires, but when it comes to implementation, a hierarchy is required to undertake more serious action.

Security. “Never permit the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage.” When fighting in a panopticon, this principle becomes even more important. Security is a cornerstone of strategy as well as of organization.

Surprise. “Strike the enemy at a time or place or in a manner for which they are unprepared.” This is key to asymmetric conflict—and again, not especially compatible with a open or participatory decision-making structures. Resistance movements are almost always outnumbered, which means they have to use surprise and swiftness to strike and accomplish their objective before those in power can marshal an overpowering response.

Simplicity. “Prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and clear, concise orders to ensure thorough understanding.” The plan must be clear and direct so that everyone understands it. The simpler a plan is, the more reliably it can be implemented by multiple cooperating groups.

In fact, these strategic principles might as well come from a different dimension as far as most (liberal) protest actions are concerned. That’s because the military strategist has the same broad objective as the radical strategist: to use the decisive application of force to accomplish a task. Neither strategist is under the illusion that the opponent is going to correct a “mistake” if this enemy gets enough information or that success can occur by simple persuasion without the backing of political force. Furthermore, both are able to clearly identify their enemy. If you identify with those in power, you’ll never be able to fight back. An oppositional culture has an identity that is distinct from that of those in power; this is a defining element of cultures of resistance. Without a clear knowledge of who your adversary is, you either end up fighting everyone (in classic horizontal hostility) or no one, and, in either case, your struggle cannot succeed.

In the US Army’s field manual on guerrilla warfare, entitled Special Forces Operations, the authors go further than the general principles of war to kindly describe the specific properties of successful asymmetric conflict. “Combat operations of guerilla forces”—and, I would add, resistance and asymmetric forces in general—“take on certain characteristics that must be understood.”2 Six key characteristics must be in place for resistance operations:

Planning. “Careful and detailed.… [p]lans provide for the attack of selected targets and subsequent operations designed to exploit the advantage gained.… Additionally, alternate targets are designated to allow subordinate units a degree of flexibility in taking advantage of sudden changes in the tactical situation.” In other words, it is important to employ maneuvering and flexible application of combat power. It’s important to emphasize that planning is notabout coming up with a concrete or complex scheme. The point is to plan well enough that they have the flexibility to improvise. It might sound counterintuitive, but the goal is to create an adaptable plan that offers many possibilities for effective action that can be applied on the fly.

Intelligence. “The basis of planning is accurate and up-to-date intelligence. Prior to initiating combat operations, a detailed intelligence collection effort is made in the projected objective area. This effort supplements the regular flow of intelligence.” That’s strategic and operational intelligence. On a tactical level, “provisions are made for keeping the target or objective area under surveillance up to the time of attack.”

Decentralized Execution. “Guerrilla combat operations feature centralized planning and decentralized execution.” It is necessary to have a coherent plan, and in order for that plan to be a surprise, the details often have to be kept secret. A centralized plan allows separate cells to carry out their work independently but still accomplish something through coordination and building toward long-term objectives. Decentralized execution is needed to reach multiple targets for a group that lacks a command and control hierarchy.

Surprise. “Attacks are executed at unexpected times and places. Set patterns of action are avoided. Maximum advantage is gained by attacking enemy weaknesses.” When planning a militant action, resisters don’t announce when or where. The point is not to make a statement, but to make a decisive material impact on systems of power. This can again be enhanced by coordination between multiple cells. “Surprise may also be enhanced by the conduct of concurrent diversionary activities.”

Short Duration Action. “Usually, combat operations of guerrilla forces are marked by action of short duration against the target followed by a rapid withdrawal of the attacking force. Prolonged combat action from fixed positions is avoided.” Resistance groups don’t have the numbers or logistics for sustained or pitched battles. If they try to draw out an engagement in one place, those in power can mobilize overwhelming force against them. So underground resistance groups appear, accomplish their objectives swiftly, and then disappear again.

Multiple Attacks. “Another characteristic of guerrilla combat operations is the employment of multiple attacks over a wide area by small units tailored to the individual missions.” Again, coordination is required. “Such action tends to deceive the enemy as to the actual location of guerrilla bases, causes him to over-estimate guerrilla strength and forces him to disperse his rear area security and counter guerrilla efforts.” That is, when those in power don’t know where an attack will come, they must spend effort to defend every single potential target—whether that means guarding them, increasing insurance costs, or closing down vulnerable installations. And as forces become more dispersed in order to guard sprawling and vulnerable infrastructure, they become less concentrated and correspondingly make easier targets.

Other writers on resistance struggles have shared these understandings. Che Guevara outlined similar strategy and tactics in his book Guerilla Warfare (1961), which itself followed from Mao Tse-Tung’s 1937 book on the subject. Colin Gubbins, former head of the British Special Operations Executive, wrote two pamphlets on the subject for use in Occupied Europe (written not long after Mao’s book). These pamphlets—The Partisan Leader’s Handbook and The Art of Guerilla Warfare—were based in part on what the British learned from T. E. Lawrence, but also from their attempts to quash resistance warfare in Ireland, Palestine, and elsewhere. In The Partisan Leader’s Handbook, Gubbins touched on the elements of surprise (“the most important thing in everything you undertake”), mobility, secrecy, and careful planning. “The whole object of this type of warfare is to strike the enemy, and disappear completely leaving no trace; and then to strike somewhere else and vanish again. By these means the enemy will never know where the next blow is coming,” he wrote.

Gubbins also urged resisters to “never engage in any operation unless you think success is certain.” Small resistance units don’t have the numbers or morale to absorb unnecessary losses. Resistance groups should only engage the enemy at points and times where they can overwhelm. The first step to take before any action is to plan a safe line of retreat, and “break off the action as soon as it becomes too risky to continue.” A newly founded resistance group often lacks the experience and training to accurately gauge how risky a situation is, which is why Gubbins recommends erring on the side of caution. It is better to learn iteratively and build up from a number of small successes than to get caught attempting operations that are too large and apt to end in failure. The takeaway message: successful resistance movements choose their battles carefully.

Just as asymmetric strategies require specific characteristics for success, they also have definite limitations.3 Resistance forces typically have “limited capabilities for static defensive or holding operations.” They often want to hold territory, to stand and fight. But when they try, it usually gets them killed, unless they’ve spent years developing extensive social and military groundwork and have a large force and popular support. Another limitation is that, especially in the beginning, resistance forces lack “formal training, equipment, weapons, and supplies” that would allow them to undertake large-scale operations. This can be gradually remedied through ongoing recruitment and training, good logistics, and the security and caution required to limit losses through attrition; however, resistance forces are often dependent on local supporters and auxiliaries—and perhaps an outside sponsoring power—for their supplies and equipment. If they can’t find those supporters, they will probably lose.

Communications offer another set of limitations. Communications in underground groups are often difficult, limited, and slow. This also applies to organizational command; the more decentralized an organization is, the longer it takes to propagate decisions, orders, and other information. And because resistance groups have small numbers and finite resources, “the entire project is dependent upon precise, timely, and accurate intelligence.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 8, 2018 | Direct Action

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “A Taxonomy of Action” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There are four basic ways to directly confront those in power. Three deal with land, property, or infrastructure, and one deals specifically with human beings. They include:

Obstruction and occupation;

Reclamation and expropriation;

Property and material destruction (threats or acts); and

Violence against humans (threats or acts)

In other words, in a physical confrontation, the resistance has three main options for any (nonhuman) target: block it, take it, or break it.

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful … tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful … tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Expropriation has been a common tactic in various stages of revolution. “Loot the looters!” proclaimed the Bolsheviks during Russia’s October Revolution. Early on, the Bolsheviks staged bank robberies to acquire funds for their cause.36 Successful revolutionaries, as well as mainstream leftists, have also engaged in more “legitimate” activities, but these are no less likely to trigger reprisals. When the democratically elected government of Iran nationalized an oil company in 1953, the CIA responded by staging a coup.37 And, of course, guerilla movements commonly “liberate” equipment from occupiers in order to carry out their own activities.

Sabotage is an essential part of war and resistance to occupation. This is widely recognized by armed forces, and the US military has published a number of manuals and pamphlets on sabotage for use by occupied people. The Simple Sabotage Field Manual published by the Office of Strategic Services during World War II offers suggestions on how to deploy and motivate saboteurs, and specific means that can be used. “Simple sabotage is more than malicious mischief,” it warns, “and it should always consist of acts whose results will be detrimental to the materials and manpower of the enemy.”38 It warns that a saboteur should never attack targets beyond his or her capacity, and should try to damage materials in use, or destined for use, by the enemy. “It will be safe for him to assume that almost any product of heavy industry is destined for enemy use, and that the most efficient fuels and lubricants also are destined for enemy use.”39 It encourages the saboteur to target transportation and communications systems and devices in particular, as well as other critical materials for the functioning of those systems and of the broader occupational apparatus. Its particular instructions range from burning enemy infrastructure to blocking toilets and jamming locks, from working slowly or inefficiently in factories to damaging work tools through deliberate negligence, from spreading false rumors or misleading information to the occupiers to engaging in long and inefficient workplace meetings.

Ever since the industrial revolution, targeting infrastructure has been a highly effective means of engaging in conflict. It may be surprising to some that the end of the American Civil War was brought about in large part by attacks on infrastructure. From its onset in 1861, the Civil War was extremely bloody, killing more American combatants than all other wars before or since, combined.40 After several years of this, President Lincoln and his chief generals agreed to move from a “limited war” to a “total war” in an attempt to decisively end the war and bring about victory.41

Historian Bruce Catton described the 1864 shift, when Union general “[William Tecumseh] Sherman led his army deep into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and South Carolina, destroying their economic infrastructures.”42Catton writes that “it was also the nineteenth-century equivalent of the modern bombing raid, a blow at the civilian underpinning of the military machine. Bridges, railroads, machine shops, warehouses—anything of this nature that lay in Sherman’s path was burned or dismantled.”43 Telegraph lines were targeted as well, but so was the agricultural base. The Union Army selectively burned barns, mills, and cotton gins, and occasionally burned crops or captured livestock. This was partly an attack on agriculture-based slavery, and partly a way of provisioning the Union Army while undermining the Confederates. These attacks did take place with a specific code of conduct, and General Sherman ordered his men to distinguish “between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly.”44

Catton argues that military engagements were “incidental” to the overall goal of striking the infrastructure, a goal which was successfully carried out.45 As historian David J. Eicher wrote, “Sherman had accomplished an amazing task. He had defied military principles by operating deep within enemy territory and without lines of supply or communication. He destroyed much of the South’s potential and psychology to wage war.”46 The strategy was crucial to the northern victory.

In resistance movements, offensive violence is rare—virtually all violence used by historical resistance groups, from revolting slaves to escaping concentration camp prisoners to women shooting abusive partners, is a response to greater violence from power, and so is both justifiable and defensive. When prisoners in the Sobibór extermination camp quietly killed SS guards in the hours leading up to their planned escape, some might argue that they committed acts of offensive violence. But they were only responding to much more extensive violence already committed by the Nazis, and were acting to avert worse violence in the immediate future.

There have been groups which engaged in systematic offensive violence and attacks directed at people rather than infrastructure. The Red Army Faction (RAF) was a militant leftist group operating in West Germany, mostly in the 1970s and 1980s. They carried out a campaign of bombings and assassination attempts mostly aimed at police, soldiers, and high-ranking government or business officials. Another example would be the Palestinian group Hamas, which has carried out a large number of violent attacks on both civilians and military personnel in Israel. (It is also a political party and holds a legally elected majority in the Palestinian National Authority. It’s often ignored that much of Hamas’s popularity comes from its many social programs, which long predate its election to government. About 90 percent of Hamas’s activities are these social programs, which include medical clinics, soup kitchens, schools and literacy programs, and orphanages.48)

It’s sometimes argued that the use of violence is never justifiable strategically, because the state will always have the larger ability to escalate beyond the resistance in a cycle of violence. In a narrow sense that’s true, but in a wider sense it’s misleading. Successful resistance groups almost never attempt to engage in overt armed conflict with those in power (except in late-stage revolutions, when the state has weakened and revolutionary forces are large and well-equipped). Guerilla groups focus on attacking where they are strongest, and those in power are weakest. The mobile, covert, hit-and-run nature of their strategy means that they can cause extensive disruption while (hopefully) avoiding government reprisals.

Furthermore, the state’s violent response isn’t just due to the use of violence by the resistance, it’s a response to the effectiveness of the resistance. We’ve seen that again and again, even where acts of omission have been the primary tactics. Those in power will use force and violence to put down any major threat to their power, regardless of the particular tactics used. So trying to avoid a violent state response is hardly a universal argument against the use of defensive violence by a resistance group.

The purpose of violent resistance isn’t simply to do violence or exact revenge, as some dogmatic critics of violence seem to believe. The purpose is to reduce the capacity of those in power to do further violence. The US guerilla warfare manual explicitly states that a “guerrilla’s objective is to diminish the enemy’s military potential.”49 (Remember what historian Bruce Catton wrote about the Union Army’s engagements with Confederate soldiers being incidental to their attacks on infrastructure.) To attack those in power without a strategy, simply to inflict indiscriminant damage, would be foolish.

The RAF used offensive violence, but probably not in a way that decreased the capacity of those in power to do violence. Starting in 1971, they shot two police and killed one. They bombed a US barracks, killing one and wounding thirteen. They bombed a police station, wounding five officers. They bombed the car of a judge. They bombed a newspaper headquarters. They bombed an officers’ club, killing three and injuring five. They attacked the West German embassy, killing two and losing two RAF members. They undertook a failed attack against an army base (which held nuclear weapons) and lost several RAF members. They assassinated the federal prosecutor general and the director of a bank in an attempted kidnapping. They hijacked an airliner, and three hijackers were killed. They kidnapped the chairman of a German industry organization (who was also a former SS officer), killing three police and a driver in the attack. When the government refused to give in to their demands to release imprisoned RAF members, they killed the chairman. They shot a policeman in a bar. They attempted to assassinate the head of NATO, blew up a car bomb in an air base parking lot, attempted to assassinate an army commander, attempted to bomb a NATO officer school, and blew up another car bomb in another air base parking lot. They separately assassinated a corporate manager and the head of an East German state trust agency. And as their final militant act, in 1993 they blew up the construction site of a new prison, causing more than one hundred million Deutsche Marks of damage. Throughout this period, they killed a number of secondary targets such as chauffeurs and bodyguards.

Setting aside for the time being the ethical questions of using offensive violence, and the strategic implications of giving up the moral high ground, how many of these acts seem like effective ways to reduce the state’s capacity for violence? In an industrial civilization, most of those in government and business are essentially interchangeable functionaries, people who perform a certain task, who can easily be replaced by another. Sure, there are unique individuals who are especially important driving forces—people like Hitler—but even if you believe Carlyle’s Great Man theory, you have to admit that most individual police, business managers, and so on will be quickly and easily replaced in their respective organizations.50 How many police and corporate functionaries are there in one country? Conversely, how many primary oil pipelines and electrical transmission lines are there? Which are most heavily guarded and surveilled, bank directors or remote electrical lines? Which will be replaced sooner, bureaucratic functionaries or bus-sized electrical components? And which attack has the greatest “return on investment?” In other words, which offers the most leverage for impact in exchange for the risk undertaken?

As we’ve said many times, the incredible level of day-to-day violence inflicted by this culture on human beings and on the natural world means that to refrain from fighting back will not prevent violence. It simply means that those in power will direct their violence at different people and over a much longer period of time. The question, as ever, is which particular strategy—violent or not—will actually work.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 1, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “A Taxonomy of Action” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

As we’ve made clear, acts of omission are not going to bring down civilization. Let’s talk about action with more potential. We can split all acts of commission into six branches:

- lobbying;

- protests and symbolic acts;

- education and awareness raising;

- support work and building alternatives;

- capacity building and logistics;

- and direct confrontation and conflict.

The illustration “Taxonomy of Action” groups them by directness. The most indirect tactics are on the left, and become progressively more direct when moving from left to right. More direct tactics involve more personal risk. (The main collective risk is failing to save the planet.) Direct acts require fewer people.

Figure 6-1. Click for larger image.

Lobbying seems attractive because if you have enough resources (i.e., money), you can get government to do things for you, magnifying your actions. Success is possible when many people push for minor change, and unlikely when few people push for major change. But lobbying is too indirect—it requires us to try to convince someone to convince other people to make a decision or pass a law, which will then hopefully be enacted by other people, and enforced by yet a further group.

Lobbying via persuasion is a dead end, not just in terms of taking down civilization, but in virtually every radical endeavor. It assumes that those in power are essentially moral and can be convinced to change their behavior. But let’s be blunt: if they wanted to do the right thing, we wouldn’t be where we are now. Or to put it another way, their moral sense (if present) is so profoundly distorted they are almost all unreachable by persuasion.

And what if they could be persuaded? Capitalists employ vast armies of professional lobbyists to manipulate government. Our ability to lobby those in power (which includes heads of governments and corporations) is vastly outmatched by their ability to lobby each other. Convincing those in power to change would require huge numbers of people. If we had those people, those in power wouldn’t be convinced—they would be replaced. Convincing them to mend their ways would be irrelevant, because we could undertake much more effective action.

Lobbying is simply not a priority in taking down civilization. This is not to diminish or insult lobbying victories like the Clean Water Act and the Wildlife Act, which have bought us valuable time. It is merely to point out that lobbying will not work to topple a system as vast as civilization.

When effective, demonstrations are part of a broader movement and go beyond the symbolic. There have been effective protests, such as the civil rights actions in Birmingham, but they were not symbolic; they were physical obstructions of business and politics. This disruption is usually illegal. Still, symbolic protests can get attention. Protests are most effective at “getting a message out” when they focus on one issue. Modern media coverage is so superficial and sensational that nuances get lost. But a critique of civilization can’t be expressed in sound bytes, so protests can’t publicize it. And civilization is so large and so ubiquitous that there is no one place to protest it. Some resistance movements have employed protests, to show strength and attract recruits, but the majority of people will never be on our side; our strategy needs to be based on effectiveness, not just numbers.

For public education to work, several conditions must be met. The resistance education and propaganda must be able to outcompete the mass media. The general public must be able and willing to unravel the prevailing falsehoods, even if doing that contravenes their own social, psychological, and economic self-interest. They must have accessible ways to change their actions, and they must choose morally preferable actions over convenient ones. Unfortunately, none of these conditions are in place right now.

Another drawback of education is its built-in delay; it may take years before a given person translates new information into action. But as we know, the planet is being murdered, and the window for effective action is small. For deep green resisters, skills training and agitation may be more effective than public education.

Education won’t directly take down civilization, but it may help to radicalize and recruit people by providing a critical interpretation of their experiences. And as civilization continues to collapse, education may encourage people to question the underlying reasons for a declining economy, food crises, and so on.

These support structures directly enable resistance. The Quakers’ Society of Friends developed a sturdy ethic of support for the families of Quakers who were arrested under draconian conditions of religious persecution (see Chapter 4: “Loyalty, Material Support, & Leadership”). People can take riskier (and more effective) action if they know that they and their families will be supported.

Building alternatives won’t directly bring down civilization, but as industrial civilization unravels, alternatives have two special roles. First, they can bolster resistance in times of crisis; resisters are more able to fight if they aren’t preoccupied with getting food, water, and shelter. Second, alternative communities can act as an escape hatch for regular people, so that their day-to-day work and efforts go to autonomous societies rather than authoritarian ones.

To serve either role, people building alternatives must be part of a culture of resistance—or better yet, part of a resistance movement. If the “alternative” people are aligned with civilization, their actions will prolong the destructiveness of the dominant culture. Let’s not forget that Hitler’s V2 rockets were powered by biofuel fermented from potatoes. The US military has built windmills at Guantanamo Bay, and is conducting research on hybrid and fuel-cell vehicles. Renewable energy is a necessity for a sustainable and equitable society, but not a guarantee of one. Militants and builders of alternatives are actually natural allies. As I wrote in What We Leave Behind, “If this monstrosity is not stopped, the carefully tended permaculture gardens and groves of lifeboat ecovillages will be nothing more than after-dinner snacks for civilization.” Organized militants can help such communities from being consumed.

In addition, even the most carefully designed ecovillage will not be sustainable if neighboring communities are not sustainable. As neighbors deplete their landbases, they have to look further afield for more resources, and a nearby ecovillage will surely be at the top of their list of targets for expansion. An ecovillage either has to ensure that its neighbors are sustainable or be able to repel their future efforts at expansion.

In many cultures, what might be considered an “alternative” by some people today is simply a traditional way of life—perhaps the traditional way of life. Peoples struggling with displacement from their lands and dealing with attempts at assimilation and genocide may be mostly concerned with their own survival and the survival of their way of life. And for many indigenous groups, expressing their traditional lifestyle and culture may be in itself a direct confrontation with power. This is a very different situation from people whose lives and lifestyles are not under immediate threat.

Of course, even people primarily concerned with the perpetuation of their traditional cultures and lifestyles are living with the fact that civilization has to come down for any of us to survive. People born into civilization, and those who have benefitted from its privilege, have a much greater responsibility to bring it down. Despite this, indigenous peoples are mostly fighting much harder against civilization than those born inside of it.

Every successful historical resistance movement has rested upon a subsistence base of some kind. Establishing that base is a necessary step, but that alone is not sufficient to stop the world from being destroyed.

Capacity Building and Logistics

Capacity building and logistics are the backbone of any successful resistance movement. Although direct confrontation and conflict may get the glory, no sustained campaign of direct action is possible without a healthy logistical and operational core. That includes the following:

Resistance movements of all kinds must be able to screen recruits or volunteers to assess their suitability and to exclude infiltrators. Members of the group must share certain essential viewpoints and values (either assured through screening or teaching) in order to maintain the group’s cohesion and focus.

Resisters need to be able to communicate securely and rapidly with one another to share information and coordinate plans. They may also need to communicate with a wider audience, for propaganda or agitation. Many resistance groups have been defeated because of inadequate communications or poor communications security.

Resistance requires funding, whether for offices and equipment, legal costs and bail, or underground activities. In aboveground resistance, procurement is mostly a subset of fund raising, since people can buy the items or materials they need. In underground resistance, procurement may mean getting specialized equipment without gathering attention or simply getting items the resistance otherwise would be unable to get.

Of course, fund raising isn’t just a way to get materials, but also a way to support mutual aid and social welfare activities, support arrestees and casualties or their families, and allow core actionists to focus on resistance efforts rather than on “making a living.”

People and equipment need access to transportation in order to reach other resisters and facilitate distribution of materials. Conventional means of transportation may be impaired by collapse, poverty, or social or political repression, but there are other ways. The Underground Railroad was a solid resistance transportation network. The Montgomery bus boycott was enabled by backup transportation systems (especially walking and carpooling) coordinated by civil rights organizers who scheduled carpools and even replaced worn-out shoes.

Security is necessary for any group big enough to make a splash and become a target for state intelligence gathering and repression. Infiltration is definitely a concern, but so is ubiquitous surveillance. This does not apply solely to people or groups considering illegal action. Nonviolent, law-abiding groups have been and are surveilled and disrupted by COINTELPRO-like entities. Many times it is the aboveground resisters who are more at risk as working aboveground means being identifiable.

Research and reconnaissance are equally important logistical tools. To be effective, any strategy requires critical information about potential targets. This is true whether a group is planning to boycott a corporation, blockade a factory, or take out a dam.

Imagine how foolish you’d feel if you organized a huge boycott against some military contractor, only to find that they’d recently converted to making school buses. Resistance researchers can help develop a strategy and identify potential targets and weaknesses, as well as tactics likely to be useful against them. Research is also needed to gain an understanding of the strategy and tactics of those in power.

There are certain essential services and care that keep a resistance movement running smoothly. These include services like the repair of equipment, clothing, and so on. Health care skills and equipment can be extremely valuable, and resistance groups should have at least basic health care capabilities, including first aid and rudimentary emergency medicine, wound care, and preventative medicine.

Coordination with allies and sponsors is often a logistical concern. Many historical guerilla and insurgent groups have been “sponsored” by other established revolutionary regimes or by states hoping to foment revolution and undermine unfriendly foreign governments. For example, in 1965 Che Guevera left postrevolutionary Cuba to help organize and train Congolese guerillas, and Cuba itself had the backing of Soviet Russia. Both Russia and the United States spent much of the Cold War “sponsoring” various resistance groups by training and arming them, partly as a method of trying to put “friendly” governments in power, and partly as a means of waging proxy wars against each other.

Resistance groups can also have sponsors and allies who are genuinely interested in supporting them, rather than attempting to manipulate them. Resistance in WWII Europe is a good example. State-sponsored armed partisan groups and other partisan and underground groups supported resistance fighters such as those in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Direct Conflict and Confrontation

Ultimately, success requires direct confrontation and conflict with power; you can’t win on the defensive. But direct confrontation doesn’t always mean overt confrontation. Disrupting and dismantling systems of power doesn’t require advertising who you are, when and where you are planning to act, or what means you will use.

Back in the heyday of the summit-hopping “antiglobalization” movement, I enjoyed seeing the Black Bloc in action. But I was discomfited when I saw them smash the windows of a Gap storefront, a Starbucks, or even a military recruiting office during a protest. I was not opposed to seeing those windows smashed, just surprised that those in the Black Bloc had deliberately waited until the one day their targets were surrounded by thousands of heavily armed riot police, with countless additional cameras recording their every move and dozens of police buses idling on the corner waiting to take them to jail. It seemed to be the worst possible time and place to act if their objective was to smash windows and escape to smash another day.

Of course, their real aim wasn’t to smash windows—if you wanted to destroy corporate property there are much more effective ways of doing it—but to fight. If they wanted to smash windows, they could have gone out in the middle of the night a few days before the protest and smashed every corporate franchise on the block without anyone stopping them. They wanted to fight power, and they wanted people to see them doing it. But we need to fight to win, and that means fighting smart. Sometimes that means being more covert or oblique, especially if effective resistance is going to trigger a punitive response.

That said, actions can be both effective and draw attention. Anarchist theorist and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin argued that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.”30 The intent of the deed is not to commit a symbolic act to get attention, but to carry out a genuinely meaningful action that will serve as an example to others.