A culture of resistance also needs the ability to think long-term. One study of student activists from the Berkeley Free Speech Movement interviewed participants five years after their sit-in. Many of them felt that the movement—and hence political action—was unsuccessful.54 Five years? Try five generations. Movements for serious social change take a long time. But a youth movement will be forever delinked from generations.

Contrast the (mostly white) ex-protestors’ attitude with the history of the Pullman porters, the black men who worked as sleeping car attendants on the railroad. The porters were both the generational and political link between slavery and the civil rights movement, accumulating income, self-respect, and the political experience they would need to wage the protracted struggle to end segregation. The very first Pullman porters were in fact formerly enslaved men. George Pullman hired them because they were people who, tragically, could act subserviently enough to make the white passengers happy. (When Pullman tried hiring black college kids from the North for summer jobs as porters, the results were often disastrous.) Yet the jobs offered two things in exchange for the subservience: economic stability (despite the gruesomely long hours) and a broadening outlook. Writes historian Larry Tye:

The importance of education was drilled into porters on the sleepers, where they got an up-close look at America’s elite that few black men were afforded, helping demystify the white race at the same time it made its advantages seem even more unfair and enticing. That was why they worked so hard for tips, took on second jobs at home, and bore the indignities of the race-conscious sleeping cars.… It was an accepted wisdom that they turned out more college graduates than anyone else. And those kids, whether or not they made lists of the most famous, grew up believing they could do anything. The result … was that Pullman porters helped give birth to the African-American professional classes.55

The porters knew that in their own lives they would only get so far. But their children were raised to carry the struggle forward. The list of black luminaries with Pullman porters in their families is impressive, from John O’Bryant (San Francisco’s first black mayor) to Florynce Kennedy to Justice Thurgood Marshall. Civil rights lawyer Elaine Jones, whose father worked as a porter to put his three kids through prestigious universities, has this to say: “All he expected in return was that we had a duty to succeed and give back. Dad said, ‘I’m doing this so they can change things.’ He won through us.”56

One reason the civil rights struggle was successful was that there was a strong linkage between the generations, an unbroken line of determination, character, and courage, that kept the movement pushing onward as it accumulated political wisdom.

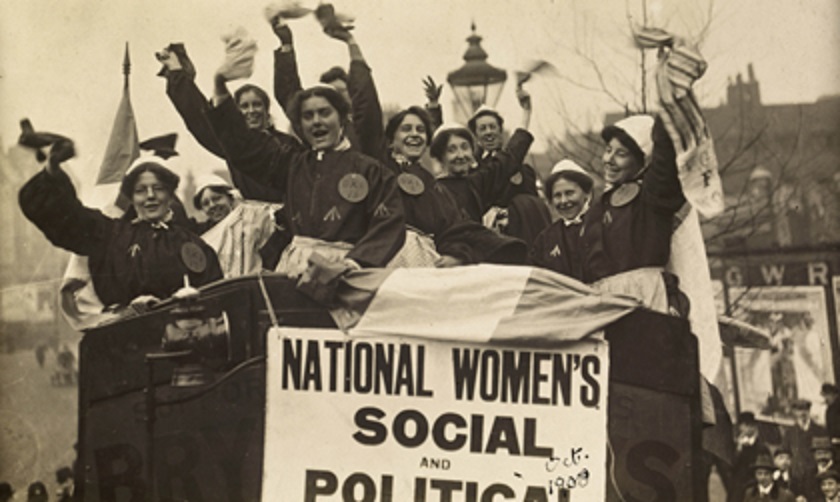

The gift of youth is its idealism and courage. That courage may veer into the foolhardy due to the young brain’s inability to foresee consequences, but the courage of the young has been a prime force in social movements across history. For instance, Sylvia Pankhurst describes what happened when the suffragist Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) embraced arson as a tactic:

In July 1912, secret arson began to be organized under the direction of Christabel Pankhurst. When the policy was fully under way, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools, and other matters as they might require. A certain exceedingly feminine-looking young lady was strolling about London, meeting militants in all sorts of public and unexpected places to arrange for perilous expeditions. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building—all the better if it were the residence of a notability—or a church, or other place of historic interest.57 (emphasis added)

Add to this that they performed these activities—including scaling buildings, climbing hedges, and running from the police—while wearing corsets and encumbered by pounds of skirting. It’s overwhelmingly the young who are willing and able to undertake these kinds of physical risks.

A great example of a working relationship between youth and elders is portrayed in the film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.58 The movie documents the Oka crisis (mentioned in Chapter 6), in which Mohawk people protected their burial ground from being turned into a golf course. The conflict escalated as the defenders barricaded roads and the local police were replaced by the army. Alanis Obomsawin was behind the barricades, so her film is not a fictional replay, but actual footage of the events. Of note here is the number of times she captured the elders—with their fully functioning prefrontal cortexes—stepping between the youth and trouble, telling them to calm down and back away. Without the warriors, the blockade never would have happened; without the elders, it’s likely there would have been a massacre.

Youth’s moral fervor and intolerance of hypocrisy often results in either/or thinking and drawing too many lines in the sand, but serious movements need the steady supply of idealism that the young provide. The psychological task of middle age is to remember that idealism helps protect against the rough wear of disappointment. Adulthood also brings responsibilities that the young can’t always understand. Having children, for instance, will put serious constraints on activism. Aging parents who need care and support cannot be abandoned. And then there’s the activist’s own basic survival needs, the demands of shelter, food, health care. The older people need the young to bring idealism and courage to the movement.

The women’s suffrage movement started with a generation of women who asked nicely. In an age when women had no right to ask for anything, they did the best they could. The struggle, like that of the Pullman porters and the succeeding civil rights movement, was handed down to the next generation. Emmeline Pankhurst recalls a childhood of fund raisers to help newly freed blacks in the US, attending her first women’s suffrage meeting at age fourteen, and bedtime stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She wrote,

Those men and women are fortunate who are born at a time when a great struggle for human freedom is in progress. It is an added good fortune to have parents who take a personal part in the great movements of their time.… Young as I was—I could not have been older than five years—I knew perfectly well the meaning of the words “slavery” and “emancipation.”59

Emmeline married Dr. Richard Pankhurst, who drafted the first women’s suffrage bill and the Married Women’s Property Act, which, when it passed in 1882, gave women control over their own wages and property. Up until then, women did not even own the clothes on their backs—men did. (The next time you buy your own shirt with your own money, remember to thank all Pankhursts great and small.) Emmeline and Richard’s daughters, Sylvia and Christabel, were the third generation of Pankhursts born to be activists. It was in large part the infusion of their youthful idealism and courage that fueled the battle for women’s suffrage. Emmeline wrote,

All their lives they had been interested in women’s suffrage. Christabel and Sylvia, as little girls, had cried to be taken to meetings. They had helped in our drawing-room meetings in every way that children can help. As they grew older we used to talk together about the suffrage, and I was sometimes rather frightened by their youthful confidence in the prospect, which they considered certain, of the success of the movement. One day Christabel startled me with the remark: “How long you women have been trying for the vote. For my part, I mean to get it.”

Was there, I reflected, any difference between trying for the vote and getting it? There is an old French proverb, “If youth could know; if age could do.” It occurred to me that if the older suffrage workers could in some way join hands with the young, unwearied, and resourceful suffragists, the movement might wake up to new life and new possibilities. After that I and my daughters together sought a way to bring about that union of young and old which would find new methods, blaze new trails.60

Emmeline raised her girls in a serious culture of resistance. As a strategist, she wisely understood that the moment was ripe for the young to push the movement on to new tactics. Thus was formed the WSPU. “We resolved to … be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. ‘Deeds, not Words’ was to be our permanent motto.”61 Those deeds would run to harassing government officials, civil disobedience, hunger strikes, and arson. They would also be successful.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 23, 2018 | Male Violence

by Heidi Hall / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

I was not yet two years out of an abusive relationship and a series of events had broken my tenuously recovered self into a million small shards – each one bearing a sharp edge to cut me again. He told me to shut the fuck up when he hit me in the face and I had come to the realization that the people around me, consciously or not, were inclined to enforce his demand.

My backpack was sitting in the corner. I only needed to double check my gear and organize some food for me and my best friend – a golden retriever named Oso. I understand it can be both emotionally taxing and dangerous to stand with someone who has become the target of an abusive person. I wish more humans had the courage of a dog.

Then there are the trees and the sky and the bare bones of the granite ridges and the never ending sound of running water and the trail in the morning and the simple living that comes from having nothing more than what you can carry on your back. There was a time when I thought I found solace in nature because it was impersonal. I have since changed my mind. There is a reason I feel much safer with the trees and the mountains and the water than I do with people. I feel loved. Unconditionally.

I remember walking through the forest on the canyon floor next to the river, one foot and one trekking pole after another, far removed from the physicality of hiking with thirty pounds on my back. I cried, I sang bits of songs and cried some more. I worked at putting away my anger at myself for what I had allowed to happen to my life. I became angry with those who had chosen, by their doubt or by their quiet apathy, to support the man who had abused me. I silently screamed “why?” at those who asked for my silence when they did not even know him. I yelled obscenities at a culture which told me if I were obedient he would not have hit me. I plotted the assassination of those who actually gave credence to the idea that he acted in self defense. Some may call this rumination and quite unhealthy. I was once told that some feelings need to be felt until you wear them out. I knew I could not bury this stuff. I chose to feel rather than fester.

And the trees listened. They did not shy away from my anger and tell me I was bad to feel what I felt. They did not say, “but you…” They did not try to tell me what I was really thinking or feeling. They did not try to fix me. They did not insist that my refusal to forgive the man was the real problem. They listened. And I kept walking.

We swam in the river that afternoon and napped on a slab of granite next to a large pool below a broad cascade. I caught a couple of trout to add to our dinner. The next morning we packed up and got on the trail early because we had to ascend an exposed and often hot southeast facing slope. This is stuff I understand. After more than forty years of backpacking I know what my responsibilities are.

We arrived at Bonnie Lake just around lunch time. We had camped here before, the second visit wilder than the first. The Sierra Nevada in California can boil up some real volatile weather in the summer and camping at the lakes near and above timberline may gift you with both humility and common sense if you are willing to learn. The first trip included wind blown rain and aiding the single pole holding up the flapping tarp while I cooked pasta shaped like little peace signs. The second trip involved torrential rain and pounding hail and using stout sticks to dig a canal so the water would continue to flow rather than pool up in our small dry space. We slept on one side of the canal and the kitchen was on the other side. When I went down to the lake to clean my fish there was the sound of a helicopter. I later learned that a group of runners left their cars in the late morning with the intention of running 100 miles through the mountains. They got wet, got scared and called for a ride. The previous day had also produced ferocious thunderstorms and the clouds had begun to build this day shortly after sunrise. I don’t know if the runners were paying attention. I think they may have expected the wilderness to comply with their terms. That is not a relationship – that is exploitation.

Unconditional love was often a topic of lecture in the abusive relationship. I was told over and over and over again that there was something wrong with me because I would not accept pornography as a part of our intimacy. He concluded that I did not love him unconditionally because I would not adopt his values and provide for his needs. I began to associate the concept of unconditional love with the image of a doormat or a bag in a boxing gym or my essence looking over its shoulder as if to walk away. This was exploitation. This was abuse.

On the surface unconditional love simply means love without any condition attached. But unconditional love is not powerlessness. You cannot love if you are dead. There is a self and there are boundaries. And the needs of one lover are no more important than the other.

So I went back to Bonnie Lake for a third time. That time we had wind – a wind which had me inventorying the trees around my campsite for potential falling limbs. If I were killed by a widow maker it would not be because the tree hates me and wants me dead. The rain falls on saints and sinners alike. I am responsible for my own well being and the wilderness will do what it does.There is no guile. There is no manipulation. There are no ultimatums given. There is no need to prove my love by performing on demand like a circus poodle. There are no lies to uncover. There is no insistence that I relinquish my agency to the wilderness and I do not expect the wilderness to bend to my will. And we share a love that is infinite, unconditional and impersonal.

Impersonal was the word that came to me after that third trip to Bonnie Lake. I was wondering if my continuing excursions to a location that seemed to want to beat me up was a kind of unhealthy relationship. I know people who will declare that an abusive man will abuse and it is not to be taken personally but it is really hard to see it that way when you are the one with the bruises. And then when I am in the wilderness I do not feel as though anything is directed at me – it just is. I sat beneath the tarp and laughed and napped, wrapped in my sleeping bag, through hailstorms and wind and cold even when I had wished for sun and warm.

Some people say an abusive person knows no other way to behave but the abuser does have enough self awareness to learn how to mimic the behaviors of someone who does not abuse. They know well enough to cover their tracks.They know precisely how and when to lie. They have the insight to understand when it may benefit them to behave like a decent person. Most abuse goes on behind closed doors. One will only rarely laugh and nap through an afternoon while in a relationship with an abuser.

But I am not certain how I would define unconditional love. I know it is not the gooey eyed infatuation which has one tolerating behaviors that may later infuriate. Nor is unconditional love the process of being subsumed into the life of another out of fear of being alone and unloved (as if love could exist side by side with demands and threats) I carry rain gear and shelter because I have respect for the summer thunderstorms. When I became afraid of my intimate partner I left for the last time.

Most of the time I do not believe there is such a thing as unconditional love. I also feel that in many circumstances the cultural concept of unconditional love is not appropriate. It is not appropriate to shame anyone because they they do not love someone who is abusing them. On the other hand someone who abuses an intimate partner, a friend, a child, an animal or the natural world is the one who deserves to be shamed and shunned.

Our culture insists we must forgive an abuser in order to heal from the abuse. My experience taught me that forgiveness leads to more abuse and I concluded that the idea of forgiveness being anything other than saying that what happened is okay is bullshit. I felt a hell of a lot worse trying to force myself to forgive and then felt worse than that because I could find no reason to forgive a man who battered both me and my dog. Like history and religion I believe the concept of forgiveness is a creation of the victor – not the victim. Or perhaps forgiveness is the creation of the apathetic bystander. Or perhaps forgiveness is preached by those privileged people who have never experienced (or deny experiencing) abuse and don’t want their individual little boat rocked by the waves of reality. Perhaps forgiveness is a clever tool for those who have something to be gained by making life easier for the abuser including the abuser himself. Perhaps unconditional love is no different.

So I came back to Bonnie Lake for the fourth time. I was coaxing a little breeze to ripple the water for my fishing. I spent the entire day exploring one side of the lake in little or no clothing. I swam out and floated on my back looking at the blue of the sky. I pulled out my watercolors and painted while lounging on a beach at a lake at 9,000 feet in elevation. We had a couple of large trout for dinner. That day of my life everything was very, very fine. I believe this is the kind of thing wilderness has to offer anyone who consistently practices personal responsibility and respect in the relationship. Perhaps that is also the root of unconditional love.

I used to believe that everyone is good in some hidden core of their being. I don’t believe that anymore. I think it is life itself which is good and one must love the life they have before they can love anyone or anything else. An abuser loves nothing. Their first victim is their own self.

Perhaps the love I sense in the wilderness is simply the pure joy of life. I can hear it in the water and the bird songs and the soft sounds of walking. I can smell it in the trees and the damp earth. I can feel it when I lie on a warm rock in the sun after a cold swim or when I climb to sit in a sunny spot in the early morning. I can see love in both the clouds and the stunningly clear sky and in the way the stars slowly overtake the darkness after the colors of sunset have faded. I know I am accepted as I am as long as I do no harm and in turn I accept wilderness with all of its danger and uncertainty and I offer my love – unconditionally.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 10, 2018 | Women & Radical Feminism

Featured image: The International Coalition Against Human Trafficking

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

“Feminism is the struggle to end sexist oppression. Therefore, it is necessarily a struggle to eradicate the ideology of domination that permeates Western culture on various levels, as well as a commitment to reorganizing society so that the self-development of people can take precedence over imperialism, economic expansion, and material desires.” – bell hooks

Last weekend, I was tabling for Deep Green Resistance at an environmental conference. A young man, who looked to be in his early 20’s, came up to the table. I approached him and asked if I could answer any questions.

He pointed at the sticker on the table: “Patriarchy + Capitalism = Pornography.” With a sneer he asked, “Do you really believe that?”

I told him I did. “So are you a SWERF,” he asked, using a common acronym for sex-worker exclusionary radical feminist. “What about agency?”

What an insane thing for a leftist to ask! Would anyone say that I’m “denying the agency of U.S. soldiers” because I oppose US imperialism? Would anyone say that I’m “excluding McDonald’s workers” because I oppose capitalism and the fast food industry?

Of course not. These arguments are self-evidently bullshit. It’s possible (and I can’t believe I have to say this) to oppose larger systems while still having sympathy, and even acting in solidarity, with those who are trapped inside those systems. And just because some women “choose” and “enjoy” working in pornography and prostitution doesn’t mean that we can’t critique the industry—and even critique these women for choices that have harmful effects on others.

The fact that a member of an oppressed class chooses to participate in the oppressive system doesn’t mean their choice can’t be criticized. After all, as the wonderful anti-porn activist Gail Dines has said, “Systems of oppression are flexible enough to absorb some members of subordinated groups; indeed, they draw strength from the illusion of neutrality provided by these exceptions.”

So why does this young white man believe that when it comes to pornography, “agency” is more important than the real, material impacts of the porn industry?

What I explained to the young man is that mass media and culture shapes the way we think. This has been a fundamental understanding of the left for decades. We can call it manufacturing consent, propaganda, or cultural hegemony.

Advertising works. Propaganda works. That’s why they use it.

That’s why Arundhati Roy, writing about right-wing police forces battling indigenous land defenders in rural India, quotes the superintendent of police chief as saying, “See Ma’am, frankly speaking this problem [sic] can’t be solved by us police or military. The problem with these tribals is they don’t understand greed. Unless they become greedy there’s no hope for us. I have told my boss: remove the force and instead put a TV in every home. Everything will be automatically sorted out.”

Take the same approach and apply it to patriarchy, and you’ll have the last 50 years of this culture: pornography becoming more and more normalized, softcore porn moving into pop culture and social media, and ubiquitous access to demeaning, woman-hating content 24/7 from the device in your pocket.

The pornography industry in the United States is more profitable than Hollywood. It’s also more profitable than the NFL, NBA, and MLB—combined. Porn sites, at any given time, have about 30 million unique visitors watching.

As Sheila Jeffries writes, “Pornography, then, educates the male public. It would be very surprising if it did not.”

Do you really think that getting paid a small amount of money in order to have a strange, smelly man aggressively fuck you is “empowering?”

Here’s the reality: prostituted women are often “physically revolted and hurt by the sex.”

Women who have escaped prostitution have higher rates of PTSD than soldiers who have been in combat.

Read that sentence again.

There are an estimated 40 million people in prostitution worldwide, most of them (more than 80 percent) women and children. Women of color make up a highly disproportionate number of prostituted women. Of the 40 million, 2.5 million are trafficked. In other words, they are sex slaves. The average age of entry to the industry is 13 years old.

Thirteen fucking years old.

But in the face of this violence, the “agency” of a few relatively wealthy “sex workers” who claim to enjoy their jobs is more important.

If we call prostitution a “job” (rather than a form of abuse), it would be by far the most dangerous job in the US, with a murder rate of 204 per 100,000. Even if we don’t call every sex act within the context of prostitution a rape, about 80 percent of prostituted women have been raped, and they are raped an average of 8-10 times per year.

As indigenous feminist Cherry Smiley writes (brilliantly) in the Globe and Mail, “Prostitution, akin to the residential school system, is an institution that continues to have devastating impacts on the lives of aboriginal women and girls, who are disproportionately involved in street-level prostitution. Prostitution is an industry that relies on disparities in power to exist. We can see clearly that women, and especially aboriginal women and girls, are funneled into prostitution as a result of systemic inequalities such as their lack of access to housing, loss of land, culture, and languages, poverty, high rates of male violence, involvement with the foster care system, suicide, criminalization, addiction, and disability. To imagine that prostitution, a system that feeds these inequalities, should be allowed or encouraged, is dangerously misguided and supports the ongoing systemic harms against our women and girls.”

The whole notion of a SWERF is ridiculous. As Jindi Mehat writes, “Supporting an argument that excludes the majority of women in prostitution, while calling the very women who consider the whole picture ‘exclusionary,’ shows how intellectually vapid and hypocritical so-called liberal feminism is. Just like calling support of prostitution, which exposes the most marginalized among us to increased levels of violence and abuse, a feminist position, this isn’t about women’s liberation, it’s about feeling good and progressive and not having to actually change anything…

“Supporting prostitution and screaming ‘SWERF’ at abolitionists isn’t feminism, it’s capitulating to male supremacy and writing marginalized women off as collateral damage. It’s living in a dream world of consequence-free individual choices. It’s refusing to go beyond scratching the surface, and instead hiding behind buzzwords and tepid half-measures while trying to silence women who are willing to dive deep no matter the cost.”

So what do we actually want?

Radical feminists generally advocate for what is called “The Nordic Model,” a legal approach in which the people (almost entirely men) who buy sex are criminalized, and the people (almost entirely women and children) who work in the industry are provided with resources and programs to help them exit the sex trade and build alternative livelihoods.

This approach has been proven to result in positive outcomes. First, it teaches sex buyers (“johns”), who are primarily men, and the broader society, that women are not for sale at any price. Second, it provides support and full decriminalization to those who are prostituted, giving them options to exit the inherently-violent industry.

In my book, that’s not exclusionary, that’s human rights. That’s feminism.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 5, 2018 | Culture of Resistance

Featured image: Black Orchid Collective

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Culture of Resistance” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

This is the history woven through the contemporary alternative culture. It takes strands of the Romantics, the Wandervogel, and the Lebensreform, winds through the Beatniks and the hippies, and splits into a series of subcultures with different emphases, from self-help and twelve-step believers to New Age spiritual shoppers. There is a set of accumulated ideas and behavioral norms that are barely articulated and yet hold sway across the left. It is my goal here to fully examine these currents so we may collectively decide which are useful and which are detrimental to the culture of resistance.

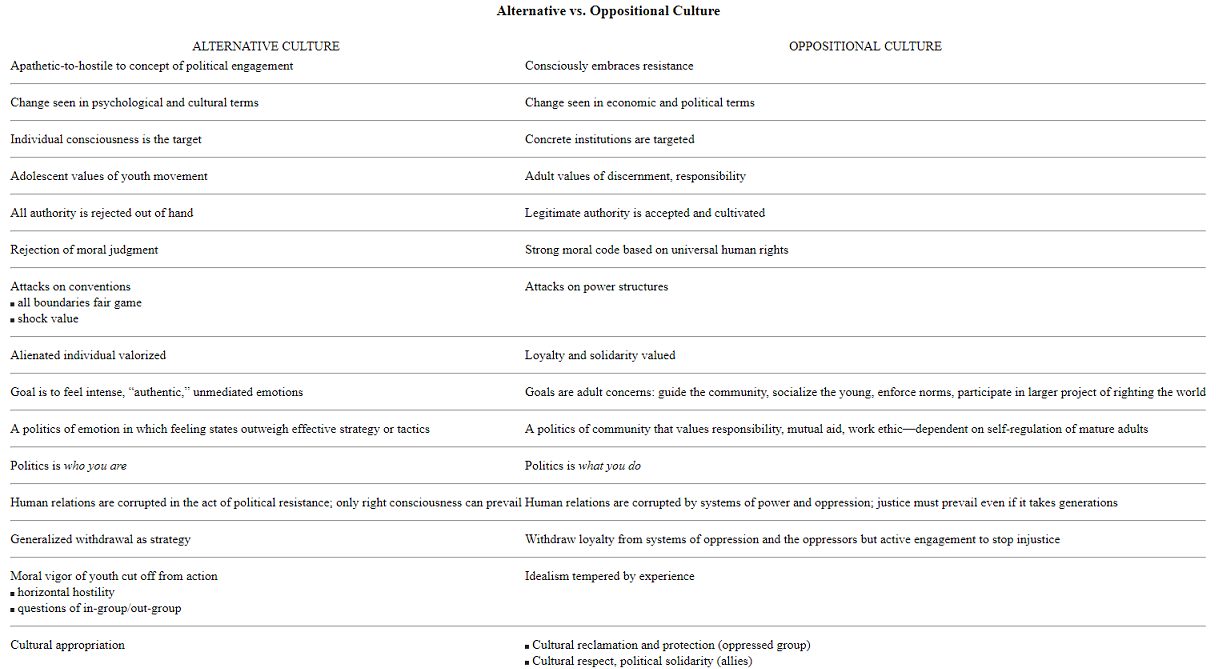

For the purposes of this discussion, I’ve set “alternative culture” against “oppositional culture,” knowing full well that real life is rarely lived in such stark terms. Many of these norms and behaviors form a continuum along which participants move with relative ease.

In my own experience, these conflicting currents have at times merged into a train wreck of the absurd and the brave, often in the same evening. The righteous vegan dinner of even more righteously shoplifted ingredients, followed by a daring attack on the fence at the military base, which included both spray painting and fervent Wicca-esque chanting—in case our energy really could bring it down—rounded out with a debrief by Talking Stick which became a foray into that happy land where polyamory meets untreated bipolar disorder (medication being a tool of The Man), a group meltdown of such operatic proportions that the neighbors called the police.

Ah, youth.

I was socialized into some of these cultural concepts and practices as a teenager. I know my way around a mosh pit, a womyn’s circle, and a chakra cleansing. I embraced much of the alternative culture for reasons that are understandable. At sixteen, fighting authority felt like life and death survival, and all hierarchy was self-evidently domination. Meanwhile, all around me, in quite varied venues, people said that personal change was political change—or even insisted that it was the only sphere where change was possible. I knew there was something wrong with that, but arguing with the New Age branch led to defeat by spiritual smugness and Gandhian clichés. The fact that I have a degenerative disease was always used as evidence against me by these people. Arguing with the militant, political branch (Did it really matter if someone ate her pizza with “liquid meat,” aka cheese? Was I really a sell-out if I saw my family on Christmas?) led to accusations of a lack of true commitment. With very little cross generational guidance and the absence of a real culture of resistance, I was left accepting some of these arguments despite internal misgivings.

Way too many potential activists, lacking neither courage nor commitment, are lost in the same confusion. It’s in the hope that we are collectively capable of something better that I offer these criticisms.

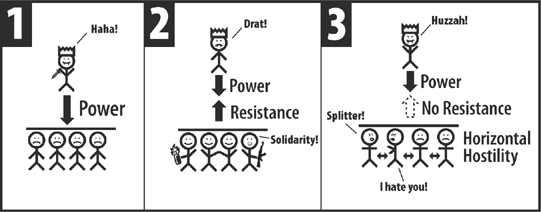

This focus on individual change is a hallmark of liberalism. It comes in a few different flavors, different enough that their proponents don’t recognize that they are all in the same category. But underneath the surface differences, the commonality of individualism puts all of these subgroups on a continuum. It starts with the virulently antipolitical dwellers in workshop culture; only individuals (i.e., themselves) are a worthy project and only individuals can change. The continuum moves toward more social consciousness to include people who identify oppression as real but still earnestly believe in liberal solutions, mainly education, psychological change, and “personal example.” It ends at the far extreme where personal lifestyle becomes personal purity and identity itself is declared a political act. These people often have a compelling radical analysis of oppression, hard won and fiercely defended. This would include such divergent groups as vegans, lesbian separatists, and anarchist rewilders. They would all feel deeply insulted to be called liberals. But if the only solutions proposed encompass nothing larger than personal action—and indeed political resistance is rejected as “participation” in an oppressive system—then the program is ultimately liberal, and doomed to fail, despite the clarity of the analysis and the dedication of its adherents.

The defining characteristic of an oppositional culture, on the other hand, is that it consciously claims to be the cradle of resistance. Where the alternative culture exists to create personal change, the oppositional culture exists to nurture a serious movement for political transformation of the institutions that control society. It understands that concrete systems of power have to be dismantled, and that such a project will require tremendous courage, commitment, risk, and potential loss of life. In the words of Andrea Dworkin,

Now, when I talk about a resistance, I am talking about an organized political resistance. I’m not just talking about something that comes and something that goes. I’m not talking about a feeling. I’m not talking about having in your heart the way things should be and going through a regular day having good, decent, wonderful ideas in your heart. I’m talking about when you put your body and your mind on the line and commit yourself to years of struggle in order to change the society in which you live. This does not mean just changing the men whom you know so that their manners will get better—although that wouldn’t be bad either.… But that’s not what a political resistance is. A political resistance goes on day and night, under cover and over ground, where people can see it and where people can’t. It is passed from generation to generation. It is taught. It is encouraged. It is celebrated. It is smart. It is savvy. It is committed. And someday it will win. It will win.27

As you can see there is a split to the root between the Romantics and the resistance, a split that’s been present for centuries. They both start with a rejection of some part of the established social order, but they identify their enemy differently, and from that difference they head in opposite directions. Again, this difference often forms a continuum in many people’s lived experience, as they move from yoga class to the food co-op to a meeting about shutting down the local nuclear power plant. But we need to understand the differences between the two poles of the continuum, even if the middle is often murky. Those differences have been obscured by two victories of liberalism: the conflation of personal change with political change, and the broad rejection of real resistance. But a merely alternative culture is not a culture of resistance, and we need clarity about how they are different.

For the alternative culture—the inheritors of the Romantic movement—the enemy is a constraining set of values and conventions, usually cast as bourgeois. Their solution is to “create an alternative world within Western society” based on “exaggerated individualism.”28 The Bohemians, for instance, were direct descendants of the Romantic movement. The Bohemian ethos has been defined by “transgression, excess, sexual outrage, eccentric behavior, outrageous appearance, nostalgia and poverty.”29 They emphasized the artist as rebel, a concept that would have been incomprehensible in the premodern era when both artists and artisans had an accepted place in the social hierarchy. The industrial age upset that order, and the displaced artist was recast as a rebel. But this rebellion was organized around an internal feeling state. Stephen Spender wrote in his appropriately titled memoir World Within World, “I pitied the unemployed, deplored social injustice, wished for peace, and held socialist views. These views were emotional.”30 Elizabeth Wilson correctly names Bohemia as “a retreat from politics.”31 She writes, “In 1838, Delphine de Girardin commented on the way in which the best-known writers and artists were free to spend their time at balls and dances because they had taken up a stance of ‘internal migration.’ They had turned their back on politics, a strategy similar to the ‘internal exile’ of East European dissidents after 1945.”32

The heroization of the individual, in whatever admixture of suffering and alienation, forms the basis of the Romantic hostility to the political sphere. The other two tendencies follow in different trajectories from that individualism. First is a valuing of emotional intensity that rejects self-reflection, rationality, and investigation. For instance, Rosseau wrote, “For us, to exist is to feel; and our sensibility is incontestably more important than reason.”33 Second is a belief that the polis, the political life of society, is yet another stultifying system for the romantic hero to reject:

Romantics … rejected the possibility of effecting change through politics. The Romantics were skeptical about merely organizational reform, about the effects of simply rearranging a society’s institutions.… The Romantics revolted not in the name of equality or to effect economic change but to enable the development of the ‘inner man.’ In this sense, they were opposed to the bourgeoisie and the radicals. Bourgeois conventions were rejected because they were shallow and artificial, and the radical’s program of social and economic change was rejected because it did nothing to free the human spirit.34

The Beatniks were inheritors of this tradition. Their main project was to “reject … the conformity and materialism of the middle class,” mostly through experimentation with drugs and sex, and to lay claim to both emotion and art as unmediated and transcendent.35 But the Beatniks were a small social phenomenon. They didn’t blossom into the hippies until the demographics of both the baby boom and the middle class provided the necessary alienated youth in the 1960s.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 26, 2018 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

“One person died and another was badly burned when a gas well exploded here last year,” my friend Adam says, pointing to an oil well set back a hundred yards from the road. We’re on the plains beneath the Front Range in Colorado, where the Rockies meet the flatlands. Oil country. Wells and fracking rigs are everywhere, scattered among the rural homes and inside city limits.

I’m on my way home from volunteering with Buffalo Field Campaign outside Yellowstone National Park, and I’ve stopped in Colorado to see friends and learn more about the fight against fracking that’s going on here.

Adam explains to me that there are thousands of wells in the area, despite widespread opposition. Cities have passed laws against fracking, been sued by industry groups in response, and lost the lawsuits. Democracy is clearly less important than profits in the United States—but that’s no surprise to anyone who is paying attention.

#

A few days earlier, Buffalo Field Campaign held the first annual Rosalie Little Thunder memorial walk through Yellowstone National Park.

We walked 8 miles past “the trap” where Yellowstone National Park uses tax money to trap and send to slaughter wild buffalo, past APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services) facilities where buffalo are captured, confined and subjected to invasive medical testing and sterilization, and past Beattie Gulch where hunters line up at Yellowstone’s boundary to shoot family groups of buffalo en masse as they walk over the Park’s border. As we walked, I watched two of Rosalie’s sisters holding hands as they walked together in honor of their sister.

Cresting a small rise, we came upon a group of more than a hundred buffalo, grazing and snorting softly to one another. As we approached the herd, indigenous organizer and musician Mignon Geli began to play her flute, accompanied by drums. As if they could sense the whispers from our hearts and the prayers carried in the music, the buffalo began to move south, further into the park and towards safety.

Safe for the moment. But by late March, that entire group may be dead. Yellowstone National Park workers—including biologists—will lure the buffalo into the trap, confine them in the “squeeze chute” for medical testing, and then ship them to slaughter. As I write this, there are about three hundred buffalo who have now been trapped, very likely including the one pictured above.

I’ve never seen a wild buffalo confined in a livestock trailer, but I’m told it’s a horrible thing. Some describe it as a metal coffin on wheels.

#

Earlier today, I gave an interview to a radio show. The host asked me about why Deep Green Resistance focuses on social justice issues in addition to saving the planet. My response was to quote my friend, who explained it more concisely than I ever could when she said, “all oppression is tied to resource extraction.”

In other words, racism doesn’t exist just for the hell of it. It was created (and is maintained) to justify the theft of land, the theft of bodies, the theft of lives. Patriarchy isn’t a system set up for fun. It’s designed to extract value from women: free and cheap labor, sexual gratification, and children (the more, the better).

I wrote earlier that protecting the buffalo requires dismantling global systems in addition to local fights. That’s because the destruction of the buffalo today is tied into the same system of “resource” extraction. Buffalo can’t be controlled like cattle, and they eat grass, which makes ranchers angry. The ranching industry exists to extract wealth and food from the land. It does this by stealing grass and land from humans and non-humans, and privatizing it for the benefit of a few.

The story is the same with fracking. The people of the front range are dealing with atrocious air quality and poisoned water. Cancers and birth defects on one hand, and big fat paychecks on the other hand, will be the legacy of the short-lived fracking boom. That, and the destruction of the last open spaces that have been preserved from urban sprawl. No vote or political party can make a difference, both because the two major parties are thoroughly capitalist and fully invested in resource extraction, and because the U.S. constitution is set up to privilege business interests above all other considerations.

#

There are differences of opinion at camp. These divides emerge during late night conversations around the woodstove and during long car rides. But looking at the rampant oppression and resource extraction we’re facing, it strikes me that we must remember to stick together. One of my friends says that we must practice radical forgiveness. Another often says that we must learn from how the buffalo take turns breaking trail in deep snow, the strongest taking the longer turns.

On the Rosalie Little Thunder memorial walk, indigenous activist Cheryl Angel spoke about how Rosalie’s fighting spirit lives on in each of us. She made a material change in the world that those of us who live have a duty to carry on.

At BFC, there is a quote from Rosalie that is often mentioned. She said, “Remind yourself every morning, every morning, every morning: ‘I’m going to do something, I’ve made a commitment.’ Not for yourself, but beyond yourself. You belong to the collective. Don’t go wandering off, or you will perish.”

Permaculture and resistance, restoration and direct action, working inside the system and revolutionary action, aboveground and underground—we all must work together to tear down the brutal empire we live within, and to build a new world from the ashes.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org