by DGR News Service | Mar 8, 2016 | Protests & Symbolic Acts, Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Sheyla Juruna/flickr

By Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

Let me say upfront: I like fun, and I like sex. But I’m sick to death of hearing that we need to make environmentalism fun and sexy. The notion is wrongheaded, disrespectful to the human and nonhuman victims of this culture, an enormous distraction that wastes time and energy we don’t have and undermines whatever slight chance we do have of developing the effective resistance required to stop this culture from killing the planet. The fact that so many people routinely call for environmentalism to be more fun and more sexy reveals not only the weakness of our movement but also the utter lack of seriousness with which even many activists approach the problems we face. When it comes to stopping the murder of the planet, too many environmentalists act more like they’re planning a party than building a movement.

For instance, there’s a video on YouTube of supermodels stripping, allegedly to warn us about global warming. How better to warn us than for a supermodel to shimmy out of her clothes to the accompaniment of a driving rock beat? The tagline beneath the video says, “No matter what your politics are, I think we can all get behind the notion of supermodels stripping.”

Well, not me. The video reinforces the values of a deeply misogynistic culture, where women’s bodies are routinely displayed for consumption by men, where pornography is a 90 billion dollar industry and the single largest commercial use of the internet. And in a movement that already loses women in droves because they’re objectified, harassed, raped, and silenced by men they’d considered comrades, do we really want to use recruiting tools that further this objectification?

Contrast the supermodel strippers with the Message from Sheyla Juruna, also on YouTube. A spokesperson for the indigenous Juruna peoples of the Xingu River in Brazil, Sheyla Juruna stares straight into the camera and says: “The Belo Monte dam is a project of death and destruction. It will decimate our populations and all of our biodiversity . . . We’ve already attempted various forms of dialogue with the government, doing everything we can to block this project, but we have not been heard. I think that it is now time for us to go to war against Belo Monte. No more dialogue. Now is the time to make more resolute and serious acts of resistance against this project.”

I guarantee that Sheyla Juruna did not become an activist for the fun and sex.

What’s more, the “fun and sexy” approach to environmentalism attempts to mobilize techniques that were developed for selling products toward building a movement. Showing a woman’s orgasmic face as she picks up a bottle of fabric softener may influence some people to purchase that brand. But becoming an activist is an entirely different process from buying fabric softener. The former requires fortitude, discipline, and dedication, while the latter requires four dollars to purchase the “natural brand that makes your laundry fluffy, cuddly, and static-free.”

In the arena of public relations, the U.S. military understands all too well something that environmentalists completely fail to grasp: How many recruiting ads have you seen selling the military as fun and sexy? None. An adventure, yes. Service to the community, yes. The few, the proud, yes. All of which, by the way, could and should be said about activism. Recruitment based on fun and sex will attract those who are in it for the fun and sex. Which means that either there will be a very high rate of attrition among such recruits or, far worse, the activism itself will become superficial enough to retain them. It ought to be obvious but in case it’s not: You can’t build a serious movement on superficiality.

The problems themselves are neither fun nor sexy, and the work of resolving these problems is anything but superficial. Organizing is hard work, sometimes tedious, often enraging, and, at this point in the ongoing murder of the planet, nearly always heartbreaking. Sheyla Juruna’s message isn’t about fun and games. Her message is about life and death — her own, that of her people, and that of the land without whom her people are no longer themselves.

Unfortunately, the notion that activism (they never dare call it resistance) has to be fun and sexy pervades the entire environmental movement, from the most self-styled radical to the most mainstream reformist. I have in my hands the most recent issue of the Earth First! Journal, which includes a photo from the most recent Earth First! Rendezvous (events that have a well-deserved reputation for drunken debauchery) depicting young men and women making a naked human pyramid. Remind me what this has to do with stopping this culture from killing the planet? Can you imagine Freedom Riders making coed naked human pyramids, painting their faces, or bringing papier-mâché puppets to sit-ins?

Or consider a recent campaign involving college students stripping to their underwear (do you see a theme?) and running around their campuses. A promotional article titled “Expose Coal Company Lies — With Your Underwear” begins, “Who doesn’t love a good cause that you can support by taking off your pants?” The “project” is a partnership between the Sierra Club and a “stylish underwear brand” called PACT. The Sierra Club, we are told, reports: “Over the past few weeks, students from coal-powered campuses have already used the underwear line in conjunction with organized events such as flash mobs, where students spontaneously [sic] strip down to their ‘Beyond Coal’ underwear, and a race to renewables, a cross-campus underwear run to advocate for the use of cleaner fuel sources.” An embedded video of the “underwear flash mob” is so thoroughly embarrassing (and depressing) that I truly hope you don’t look it up. Beneath the video, the text reads, “Hats Pants off to the Sierra Club and PACT!”

Do I really need to explore what’s wrong with (and creepy about) Sierra Club leaders and underwear makers encouraging young people to take off their clothes, much less pretending this is activism? I’m thinking about a recent global warming campaign where “3,000 people in New Delhi formed an enormous elephant threatened by rising seas — a plea to world leaders not to ignore the ‘elephant in the room.’” I’m thinking about face painting, and I’m thinking about puppets. And I’m thinking how spectacle supplants reality.

I’m also thinking about a conversation I had with some First Nations people in Vancouver, British Columbia, who described how, during the anti-Olympics protests, some Indian warriors were standing firm, alongside some of their nonindigenous allies, facing down police over the desecration of their lands. And they looked behind them and saw a physical separation between themselves on the one hand, and a big cohort of mostly white protesters on the other. But the separation was far more than physical, because the people in front were all dead serious, and behind them were any number of people wearing bunny costumes or running around in cardboard models of bobsleds.

When and why and how did partying and spectacle and debauchery become a substitute for serious political organizing and resistance? How did taking off one’s pants and running around become a political act? And where does dignity fit into any of this? There is, of course, a role for absurdity in political discourse. But the role of absurdity in political discourse is to ridicule and humiliate those in power, not ourselves.

The Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising took up arms in defense of their lives. The Shawnee war chief Tecumseh took up arms in defense of his people and his land. Harriet Tubman risked her own life to free her people. We, on the other hand, have a long way to go to form a serious resistance movement.

Originally published in the January/February 2012 issue of Orion.

First published online here.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 13, 2016 | Male Violence, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis, Women & Radical Feminism

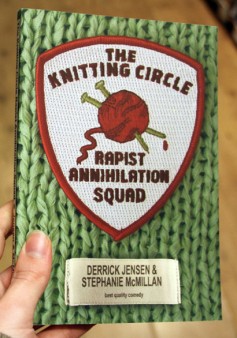

This is the second part of a series. Read the first part at Toward Strategic Feminist Action.

By Tara Prema / Gender is War

Developing an effective response to the worldwide crisis of male violence

Strategic Feminism is a framework for collective action against patriarchal violence. The framework is based on acknowledging that the struggle for women’s liberation can – and must – adapt the lessons of asymmetric conflicts, such as guerrilla uprisings against occupying armies. We can apply the lessons of successful insurgencies to our aboveground organizing. And we must do so. It is a matter of life and death: every minute, men rape, abuse, abduct, and murder girls and women. Time is short – we must prepare for worse still to come.

Strategic Feminism draws on the excellent analysis of asymmetric conflict in Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. In Part One, we discussed the crisis of male violence against women and sketched a solution based on organizing for action in our communities. Here in Part Two, we look at more ways to begin and sustain our work for radical social change.

We call this model Strategic Feminism because it’s outcome-oriented and focused on creating a movement that addresses the material conditions affecting women’s lives.

Sustaining a movement: Feminism in collapse

How can we create a movement in a time of collapse? How do we come together as a force for change when individuals burn out, groups fall apart, and coalitions fracture? When feminists are fighting each other on questions of gender, motherhood, sexuality, and privilege?

And how to do we take these steps now, when every day brings more signs of cultural, economic, and environmental collapse? How do we adapt our strategies to a world order that is reeling from one crisis to the next? This is our challenge.

As radical women, we must pledge to protect each other and the places we love, just as women have done since the time they burned us as witches.

Keeping the spirit

Keeping the spirit

At the core of this movement, there is an intangible force with a measurable impact. It’s an attitude, a mindset, a determination that compels us to push back against oppression. It’s the warrior mindset, the stand-and-fight stance of someone defending her home and the ones she loves.

Many burn with righteous anger. This is important – anger lets us know when people are hurting us and the ones we love. It’s part of the process of healing from trauma. Anger can rouse us from depression and move us past denial and bargaining. It is a step toward acceptance and taking action.

Rewriting the trauma script includes asserting our truth and lived experiences, and naming abuses instead of glossing over them. It includes discovering (and rediscovering) that we can rely on each other instead of on men. It’s mustering the courage to confront male violence. But it’s not going to be easy.

Acknowledge and #NameTheProblem

We can’t fight a problem we can’t identify, especially when it is deliberately obscured. It’s not surprising that naming the problem has become a political act. And the problem is male violence against women. We shouldn’t have to say “she was raped” when we know that “men raped her.”

Reclaim what was taken from us

- Learning (and re-learning and reminding each other) that our bodies and spirits belong to us, we deserve to be safe, and we have the capacity to defend ourselves

- Fighting isolation and connecting with other women who have a similar fighting spirit

- Creating a culture of resistance to male violence

Taking action

Strategies are the paths to the goal. Tactics are the means to implement strategies. Part of a strategy for sustaining a movement is networks of peer support, mutual aid, and solidarity. We start by coming together with our peers, women who share the same goals and principles.

Goal: Develop a thriving network capable of effective action

Strategy: Find women allies and start a group

Tactics:

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.- When you get an invitation, go!

- Use a petition or sign-on letter to gather potential recruits.

- Screen and interview volunteers.

- Discuss and write up a basis of unity

- Hold meetings, discussions, films, work parties, and benefit shows.

- Keep a signup sheet and a list of participants.

- Retain volunteers through appreciation and peer support.

- Raise money for projects and community campaigns.

Strategy: Start with an existing group

- Entryism – add members until your crew has a majority

- Headhunting – join in order to recruit members to your group

- Affinity group – organize an action team within the group

- Symbiosis – utilize the group’s resources and membership for your project

Strategy: Build a coalition

- Circulate a sign-on letter

- Organize against a common political enemy

- Host an event: A symposium, press conference, rally, or direct action

- Pledge to support and not publicly denounce each other

- Collaborate together on an ongoing project

Strategy: Keep each other safe and supported

- Have designated safe houses and emergency plans

- Set up a legal defence fund and legal team before they’re needed

- Create a mutual aid network so women activists can support each other

- Make and distribute an activist safety/security plan to stop online hackers and physical attackers

- Prioritize peer support and peer counseling, whether it’s formal or informal.

- Keep a “not wanted” list to weed out known disruptors

- Host group self-defense and security awareness trainings

Choosing our battles

How do we decide on a particular project, campaign, action or strategy? We can ask:

- Is it effective? What will it achieve?

- What are our goals (immediate and long-term )? How does this action lead there?

- Who is working with us?

- Do we have community support? From which communities?

- What decision-makers are we targeting?

- What are our strategies and tactics? (Legal, confrontational, revolutionary?)

- Do we have the resources? (People power, funds, vehicle?)

- How can we get the resources? (Recruiting, crowdfunding, direct appeals?)

- What are the possible negative outcomes? How can we mitigate the negatives?

Some actions and projects aren’t intended to lead to concrete results – they are symbolic in nature but still useful for boosting morale, getting media attention, and recruiting volunteers.

Male allies

Male allies can – and should – make substantial contributions to the movement. Consider asking women what we need to sustain our work, and then providing that without judgment or trying to exercise veto power. Men who take on ally roles should turn to other men for peer support and take time to debrief with them regularly.

Remember to regroup

Every campaign, project, and group will stall eventually. We invariably reach the point when it seems our efforts are going nowhere and our adversaries are dragging us down. This is when we must re-group and re-commit ourselves or fail. Every goal worth fighting for is going to face a serious backlash from those in power.

In spite of all our planning, our groups and coalitions still fall apart due to lack of unity, loss of commitment, burnout, and the divisive pressures of racism, classism, misogyny, and disruption from outsiders. Overall, things are not going to get better on their own. In the endgame of capitalism, the situation for women as a class worldwide is deteriorating at a fearsome rate. It’s up to us to prepare for the worst.

In the short term, this anti-feminist backlash is intensifying. Planning now is crucial. Some readers may not see the immediate need for this laundry list of tactics and strategies. But the day is coming when the need for community networks of trust will be urgent, because so much of what we rely on now has collapsed.

These notes come from unceded indigenous territory on the frontier of resistance to the western patriarchal invasion.

by DGR News Service | Feb 12, 2016 | Culture of Resistance, Strategy & Analysis

Edited transcription of an interview by John Carico for The Fifth Column

How do you feel about Dr. Jill Stein and the Green Party of America?

I’m not a huge fan of the Green Party. I did a talk ten years ago at the Bioneers conference, which is about social change and environmentalism. One year their tagline was “the shift is hitting the fan,” about paradigm shifting. The thing that broke my heart was, so far as I know, I was the only person there who talked about power and psychopathology. I don’t think you can talk about social change without talking about power, and I don’t think you can talk about the destruction of the planet without talking about psychopathology. The Green Party has a lot of really good ideas, but how do you actually put them in place, given that those in power are sociopaths and the entire system rewards sociopathic behavior?

That doesn’t mean we need to give up or do nothing. A doctor friend of mine says the first step to a cure is proper diagnosis. If part of the disease that’s killing the planet is this sociopathological behavior, then fighting that sociopathological behavior needs to be part of our response.

I have voted Green in a couple of elections, and would vote again for a local Green. On the national level, the voting I’ve done was pretty much symbolic. I voted for Nader. I voted for a friend one time. The last time that I voted for any mainstream candidate was against Reagan in ‘84, and you pretty much had to vote against Reagan. But, interestingly, in 1980 I voted for Reagan and then realized I was an idiot, and voted Democrat in ’84. By ’88, I had an awakening and realized the whole system was just full of crap.

I do believe in voting on a local level. Voting on a national level may not change much, but locally, you can protect some things.

What warnings would you give young environmentalists as to how to differentiate green-washing from effective efforts?

The best way we learn is by making mistakes. The advice I give to young activists is to find what they love and defend it. Probably at some point, when they run up against the economic system, they’ll find themselves screwed over. That’s a lesson we all have to learn.

By the mid 1990s, I had already recognized that this culture is inherently destructive, but the “salvage rider” was still a big lesson for me. In ’95, activists all over the country had been able to shut down the Forest Service timber sales using the appeal process. Basically, if you could show the timber sales were breaking the law, you could appeal to have them stopped. Then they would have to produce a new document. Then you would stop them again by showing where they violated the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, etc. We were successful enough that Congress passed the salvage rider, wherein any timber sales that they wanted would be exempt from environmental regulations. The lesson was that any time you win using their rules to stop the injustice and stop the destruction, they will change the rules on you. There is really no substitute for learning this lesson yourself.

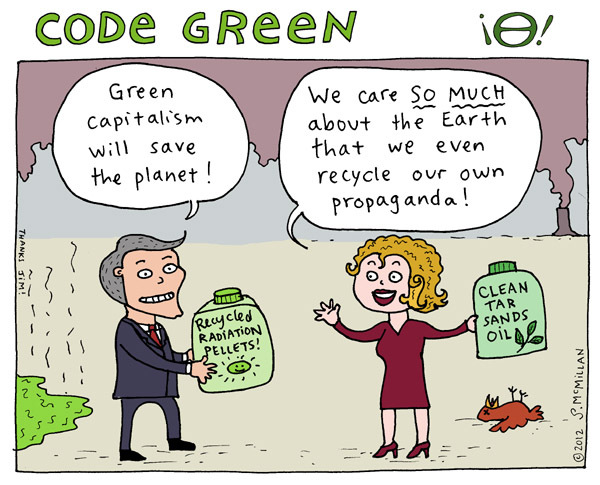

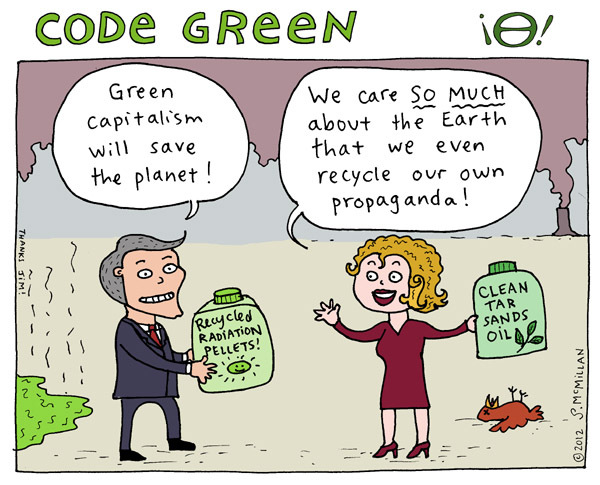

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

Recognizing Greenwashing comes down to what so many indigenous people have said to me: we have to decolonize our hearts and minds. We have to shift our loyalty away from the system and toward the landbase and the natural world. So the central question is: where is the primary loyalty of the people involved? Is it to the natural world, or to the system?

What do all the so-called solutions for global warming have in common? They take industrialization, the economic system, and colonialism as a given; and expect the natural world to conform to industrial capitalism. That’s literally insane, out of touch with physical reality. There has been this terrible coup where sustainability doesn’t mean sustaining the natural ecosystem, but instead means sustaining the economic system.

So when figuring out if something is greenwashing, ask, “Does this thing primarily help sustain the economic system or the natural world?”

That’s one of the problems I have with industrial solar and wind energy. They are primarily aimed at extending the party, not aimed at protecting salmon.

I would also ask young people to think about the linkages. A solar cell may be really groovy and you can power your pot grow but where did the solar cell come from? It required mining. It required global infrastructure. Even climate activists ignore these linkages. I heard one activist say, “Solar power has no costs, only benefits.” Tell that to the lake in Bhatu, China, who is now completely dead as a result of rare earth mining. Tell that to the people, human and nonhuman, who no longer can sustain themselves from the lake or from the land poisoned all around it.

A friend of mine says, “A lot of environmentalists start by wanting to protect one specific piece of land, and move on to questioning the entire culture of western civilization.” Once you start asking the questions, they don’t stop. “Why are they trying to destroy this piece of land?” leads to, “Why do they want to destroy other pieces of land?” Then you ask, “Why do we have an economic system based on destroying land? What is the history of this economic system? What happens when it runs out of frontiers? What happens when you have overshoot?” It’s important for young activists never to stop asking those questions.

Can you name successful revolutions of the past that you think we should look to when forming our own strategies? Where colonizing powers withdrew, and left the economy to its people?

Economy is a really hard word when you have a global economic system. We can talk about the Irish kicking the British out, or the Vietnamese kicking out the United States, but the real winner in Vietnam is Coca Cola, because Vietnam is still tied into the global economic system.

I think it’s great that the Indians and Irish kicked out the British and that the Vietnamese kicked out the U.S., so I’m not attacking revolution when I say this. But one of the problems is that when you defeat a certain mindset, it will often find expression in another way. When the United States illegalized chattel slavery, the underlying entitlement, where white people felt entitled to the lives and labor of the African Americans, was still there and found expression in a new way with the Jim Crow Laws. We see this all the way up to today with mass incarceration of African American males in such shameful ways. Like I said earlier, we need to keep looking at the linkages and, unfortunately, this makes one depressed. Because when you see a victory, oftentimes, you also see a backlash and a reconfiguration and reestablishment of the underlying bigotry.

We see this too with monotheism’s movement toward science, especially mechanistic science, where the world is not alive. The monotheism of the Christian sky-god did the initial heavy lifting by taking meaning out of the world and leaving it up there. Mechanistic science is really just an extension. We can say, “Wow, we really got rid of the superstition and the bigotry that has to do with Christianity,” but this belief in science is even scarier. At least with the Christian sky-god there was someone above humans. Now humans are making themselves into this new god and think they control the whole planet.

Having said that as a preamble, the film The Wind That Shakes the Barley highlights one of the smart things the Irish did. The film starts off with all these Irish guys playing hurling. When I saw this at first, I thought, “What the hell does this have to do with the Irish liberation struggle?” As I mentioned, one of the things we have to do is to decolonize ourselves. They did this in part by playing Irish sports, using Gaelic Language, and reading Gaelic Literature. A successful revolution begins with breaking identification with the dominat system. First comes the emotional part. After that, it’s all strategy and tactics; you look around and ask, “What do we want to do, blow something up, vote, peaceful strikes?”

This ties back into everything we’ve talked about so far. Are we identifying with a system or are we identifying with those we are trying to protect? We can say the civil rights movement was successful in the sense that African Americans now have a provisional right to vote. Of course mass incarceration targets black males and thus takes away their right to vote, but the movement was still successful in that it accomplished some aims. This was done by identifying as black voters. So, identifying is very important.

Several years out from the writing of Decisive Ecological Warfare, is there anything you would change in terms of strategy that you’ve learned since?

We don’t know because no one is doing it. All I know is that there are more than 450 dead zones in the world and only one of those has recovered — in the Black Sea. The Soviet Union collapsed, making agriculture no longer economically feasible there. They stopped agriculture and the dead zone has recovered enough that they now have a commercial fishery. That makes clear to me that the planet will bounce back when this culture stops killing it, presuming there’s anything left.

The image that keeps coming to mind is this body, which is the earth, and it keeps bleeding out because it’s been stabbed 300 times. All these people are trying to heal this body, and they are doing CPR and putting on bandages and everything else. But they’re not stopping the killer who’s still stabbing the person to death. We have to stop that primary damage. We have to recognize that we can’t have it all. We can’t have a way of life that relies on industrial capitalism and continue to have a planet.

Now, I haven’t really answered your question, mostly because of what I said at first: nobody’s doing it, so we don’t know what mistakes there are in the strategy. I’ve been saying for fifteen years that if space aliens came down to earth and were doing what industrial civilization is doing to the planet, we would put in place Decisive Ecological Warfare. We would destroy their infrastructure. This is an important point. We can make a very strong argument that World War II was won by the Allies, primarily in the killing fields of Russia. But I would argue that either first or second most important was the destruction of German industrial capacity. Similarly, the North won the Civil War not just because they had better generals, but because they destroyed the South’s capacity to wage war.

I don’t care how we do it; we can do it by voting, if that works. But we have to find a way to stop this culture from waging war on the planet.

Will Potter’s Green Is the New Red talks about the crackdown against Green movements. Do you have any advice for people who want to speak openly about resistance but are afraid of the repercussions? Where is the line between security culture and the need for movement building? The Invisible Committee says we need to tie the actions that have been done into a narrative. Is the problem that the media never covers the actions of those who, for instance, did direct action against fracking in New Jersey, and that any direct action the media does cover seems to follow the horrible lone wolf narratives? Do you think this stifles our movement?

What you say makes a lot of sense. Coverage of direct actions, and the true reasons behind those actions, can’t be left to mainstream media. The movement needs people aboveground who can publish the narrative, and another separate group which is underground, to actually do it. Both roles are critical, but we need a firewall. Many activists have been arrested partly because they tried to do both. We in Deep Green Resistance are trying to fill that aboveground role, as is the North American Animal Liberation Front Press Office.

As for security culture…I think, sometimes, about the whole marijuana legalization movement (I realize this isn’t so much a successful revolutionary movement as a successful social movement). They’ve done a good job pushing an agenda that would have been unthinkable thirty years ago. They’ve done this by using this model, by being below ground with the growers and above ground with NORML. We can say the same thing about the IRA.

You need that firewall when you live in a security state, but we shouldn’t feel unnecessarily paranoid. Although surveillance is everywhere and they pretend they are God, those sitting at the top are not actually omniscient. Living in northern California, where the pot economy basically runs the entire economy, has helped me to a healthy understanding that the Panopticon is not as all seeing as it wants to be. (Again, I know there is a difference between A) growing marijuana, which many cops probably smoke or view with sympathy, and B) ending capitalism, which would freak out all the cops.)

I’m very naive about many things, including drug culture. But I used to teach at Pelican Bay, a Supermax Prison, and students told me that if you dropped them into any city in the world, they could find drugs within 15 minutes. I couldn’t even find a bathroom in 15 minutes! That means the underground economy is surviving the Panopticon very well; it isn’t omniscient.

The Green Scare did not succeed because of the power of the Panopticon, or because of brilliant police work. The cases of sabotage were solved by good old-fashioned stoolie, because Jake Ferguson was an abuser, junkie and a snitch. Basic security culture probably would have defeated the investigations.

Can you give a critique of anarchists and why you see a lot of their work as ineffective?

I had a conversation a couple years ago with a very famous, dedicated anarchist who has some critiques of anarchism, but didn’t want me to use his name because he knows if he says anything critical about anarchism he will get death threats. One of the big problems is that anarchism is open membership, in that anyone can become an anarchist simply by identifying as an anarchist. He says many who call themselves anarchist, aren’t; they are just antisocial and have found an ideological excuse for their bad behavior. He says anarchists have a long tradition of fighting for the eight-hour work day, or fighting againt fascism as in Spain. He says there needs to be a way to kick out people who are simply sociopaths who call themselves anarchists. I mean, here’s a quote by an anarchist/queer theorist: “Smashing the institutions of patriarchal racist capitalism goes hand in hand with being a repulsive perverted freak.” Seriously? We’re supposed to put this person in the same category as Goldman or Kropotkin? Are we going to let that person in, even if they are just a prick? Any group will have nutjobs: Republicans, Democrats, stamp collectors. But anarchism is so small, so vocal, and so open that the nut jobs really stand out and can discredit the larger group.

I’m also concerned about effectiveness. The individualist anarchists (as opposed to collectivist anarchists) have an active hostility toward organization. DGR isn’t alone in getting attacked for this, for being perceived as hierarchical. I’ve seen writing on this going back 40 years, with anybody who believes you can have an organization with a stable schema immediately being attacked as Stalinist. They attack the organization simply because it’s an organization. There is a great line by Samuel Huntington that says “The west won the world, not by the strength of its ideals, but by its application of organized violence.” (He’s actually a supporter of the western empire; he says it’s a good thing.)

I talk about this in Endgame. I have become convinced that the single most important invention of the dominant culture, which has allowed it to destroy the planet, is the top-down bureaucratic military style organization. I’m not saying we need to model our organizations after this, but it is really effective. It is how this culture was able to murder the Native Americans. They had one big army. In my experience, people can generally be very contentious. It’s really hard to get together on the same page.

I had a friend who was trying to start an environmental organization years ago. An indigenous member warned that 95% of the time would be spent dealing with personality conflicts, and the other 5% actually doing the work. It’s an accomplishment, albeit a terrible one, that the U.S. Military gets 5 million people to act toward one aim: killing brown people, or whatever it is they are doing. They have propaganda on TV and in print, they have the capitalist system which rewards bad behavior, they have an organizational schema and, on the other side, we are supposed to defeat them without being organized?

Civil War General McClellan lost against Lee due to piecemeal efforts. McClellan attacked in one place and Lee moved his troops back. McClellan attacked another place, and Lee moved his troops back. The Turkish military had a strategy of attacking in piecemeal, and lost every battle for nearly two hundred years. The Russians would attack en masse and the Turkish army would send in one unit at a time and get slaughtered. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a terrible racist but brilliant Civil War strategist, said, “The way you win a battle is getting there first with the most.” In any conflict you want local superiority.

You asked why I see anarchist strategy as oftentimes ineffective: if you’re fighting an organized force, you should try to be organized as well.

Can you give a definition of Radical Feminism, and a response to some of your detractors who’ve accused DGR of transphobia?

The question I would ask is “Given that we live in a rape culture, do you believe women have the right to bathe, sleep, organize, and gather, free from the presence of males?” If you do believe that women have that right, you will be accused of transphobia; you will receive death threats. If you are a woman, you will receive rape threats. I’ve been de-platformed over this, some trans activists have threatened to kill the children of DGR activists over this. All because I believe that women have the right to gather free from the presence of males.

I want to make clear that no one in DGR is telling anyone how to live. I don’t give a shit! I’m not saying people who identify as trans should get paid less for their work, or that they shouldn’t have whatever sexual partner they want. I’m not suggesting they should be kicked out of their house, or should be de-platformed from a university, or that anything bad should happen to them.

Somebody wrote me and said, “I have a a little five-year-old boy who loves to wear frilly clothes, loves to dance ‘like a girl’, and sing ‘like a girl’; doesn’t this make him transgender?” I wrote back and asked, “Are you saying only little girls can wear frilly clothes? Why can’t we just say ‘this is a little boy who likes to play with dolls, and sing in a high voice?’ Why can’t we just love and accept this child for who he is? What does it even mean to dance ‘like a girl’? ”

Shoddy thinking makes me angry. I know the trans allies are going to get mad when I say, “Women should be able to gather alone” because they will then ask, “Who are women? Aren’t trans who identify as women, in fact women?” My definition of woman is human female, and my definition of female is based on biology. Some species are dimorphic. Just like there are male marijuana plants and female marijuana plants, and male hippopotami and female hippopotami, there are male humans and female humans.

I want to say two things before anyone offers a counter-definition of ‘woman’:

1. A definition cannot be tautological. You cannot use a word to define itself. You cannot say, “A woman is someone who identifies as a woman,” any more than you can say, “A square is something that sort of resembles a square.”

2. A definition must have a clearly defined metric. If I said, “Here is a three sided thing, it’s a square,” you would say, “No, it’s not a square because a square has 4 sides.” You have to be able to verify. I can say I’m a vegetarian but I had great ribs for dinner. This destroys not only the word ‘vegetarian’ but also the word ‘definition.’ I would ask those who disagree with my definition, “What is your better definition that is verifiable, for the word ‘woman’?” and second, “Is the fact that I have a different definition for the word ‘woman’, which is defensible linguistically, so important that you think it’s acceptable for men to threaten to rape women?”

I’ve never publically discussed this point before, but I think this is an important issue to discuss. It’s part of a larger post-modern social movement that values what we think and what we feel over what is real. This takes us right back to the greenwashing, with people saying, “We have to come up with the economy we want.” No, first we have to figure out what the Earth will allow!

This culture has a deep hate for the embodied and for what is natural. Here’s a great example: I have coronary artery disease, and I told my doctor I was feeling better since I had been diagnosed. This was right before Obamacare kicked in, so I didn’t have insurance yet. The pain got less in that time, and I asked why. The doctor said that when the arteries get clogged, the body sends out capillaries all around it to basically do its own version of bypass surgery. I had never heard that before. We all think it’s some miraculous thing when someone cuts open your chest and does bypass surgery, but we don’t even think about it when the body does it itself. There is tremendous wisdom of knowledge in the body, and we have to learn to respect it. This is important, both on a larger global scale and on the personal scale. I think it’s really important to recognize how this culture devalues the body. How I feel is way less important than what is.

Can you talk a bit about left sectarianism?

This goes back to the machine-like organizational structure of the dominant culture, which I am not valorizing, but do recognize as really fucking effective. It’s been able to get people past sectarianism.

Over the years, I’ve gotten thousands of pieces of hate mail, of which only a couple hundred were from right wingers. I’ve gotten hate mail from anti-car activists because I drive a car, vegans because I eat meat, and anarchists because I believe in laws against rape. I’ve never understood why animal rights activists and hunters don’t work together to protect the habitat. I wouldn’t have a problem with that. I do believe in temporary alliances. Once that’s done, animal rights activists can sabotage the hunts.

There’s a great example from 300 or 400 CE. These two sects of Christianity fought, same name but one had an umlaut, and one didn’t. They killed each other — hundreds of people! — over the question “Do you believe the fires of hell are literal or figurative?”

I was talking to a guy about the left always attacking each other. He mentioned that where he lived in West Virginia, there used to be a single KKK chapter consisting of three brothers. Now they have three chapters, because they can’t stand each other. So it’s not just a problem on the left.

Instead of getting mad at sectarianism, which I’ve been doing for the past fifteen years, we need to figure out what to do about it. It’s probably part of the human condition.

My friend Jeanette Armstrong, an indigenous activist and writer, told me once, “We, in our community, have just as many squabbles as white people do. The difference is I know my great-grandchild might marry your great-grandchild, so we figure out how to get along.” I really like that. I think we just have to ask “What are we really trying to do?”

What’s wrong with me having a really strong disagreement with a trans activist, for example, and them having a really strong disagreement with me? We can both continue doing our work and, at worst, ignore each other. There are plenty of people with whom I disagree. Families have different political views all the time and still love each other.

The question I’ve been asked over the years that cracks me up is what it’s like at my house on Thanksgiving. One of my sisters is a petroleum engineer, and she used to be married to a guy who did cyanide heat leaching and owned a gold mine. Now she’s married to a guy who used to work for the NSA and now works for the Israeli Military. What do we talk about? We talk about football. My brother is a huge Seattle Seahawks fan, so go, Hawks! I don’t talk about environmental stuff; it’d just start an argument. So I don’t understand why we activists can’t agree to disagree.

Noam Chomsky, who really disagrees with the anti-industrial perspective, is another great example. I was scheduled to give a talk in Scotland, and they wanted to ask me about Chomsky blasting anti-industrialism. I really disagree with him on this, but I really respect his work, so my agent, a really smart person and also Chomsky’s agent, said just to say “I’m not attacking Chomsky. We just have a disagreement on this.” I don’t understand why we can’t do this more often. There is a limit, of course. Roman Polanski is a rapist, so it makes sense to talk about his personal life.

I can’t stand Richard Dawkins, have critiqued his work a lot, and have heard, individually, that he’s pompous. But I’ve never heard that he’s a rapist or anything so I don’t know why I wouldn’t just keep my critiques focused on his work.

I think film is really detrimental to communication, because it’s so removed from real life and the way we communicate. In order to move a film story forward, you need dramatic tension. So a lot of times you have people fighting who wouldn’t fight in real life, and because we learn to communicate from the stories we take in, we learn to be even more contentious than we otherwise would be.

I know someone who was on Bill Maher and was relatively polite. They got mad and said, “If you are ever on the show again, you have to interrupt people and be contentious, because that’s what makes the show work. We want Jerry Springer, we want people to throw chairs.” We may not really want that, but that’s what works for the spectacle. And then we learn that’s acceptable behavior.

I’m writing a book right now with a coauthor. We had a significant conflict Saturday, but both parties handled it in a mature fashion. We still have a significant disagreement, but we strengthened our friendship because we handled it maturely.

What are your thoughts on Prison Abolition?

When talking about prison abolition, I get a little nervous because I can’t wrap my head around it. Obviously the prison system is horrendous. But I’m not a prison abolitionist, because when I taught at the Supermax, the students agreed that the only way for prison abolition to work is if you’re going to kill a bunch of people. I knew a kid who was put out for prostitution at age four, and really, what chance did this kid have? He was really fucked up by the time he was six. Another kid was living on the streets of Oklahoma at six with his little brother. This guy is now doing life for murder. Probably the first time he knew where his next meal was coming from was when he got to prison.

My creative writing students used to pass around jellybeans, but warned me never to take anything from one inmate. He had tortured a person to death, and since getting to prison, he’d poisoned three people. Something, obviously, had happened to this guy.

A friend had a student who said to her, “I am so broken, I need to be kept out of society.”

Another guy — not sure if he was executed or died on death row — killed his wife and kid and put each heart in a separate pocket because “the blood couldn’t mix.” When he was on trial, he pulled out one of his eyes because “that’s how the feds were putting stuff into his brain.” That didn’t work, so he pulled out his other eye and ate it. I’m not saying he needed to be in prison as it currently exists, but he definitely needed to be separated from society. Or removed. What do you do with Ted Bundy?

I’m not saying that Ted Bundy makes the case for locking up some fifteen year old, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t eliminate for-profit prisons and the prison industrial complex. And I’m mostly against the death penalty — though I think Tony Hayward of BP should be executed, it’s outrageous as it is because it’s racist and classist. But the whole culture is completely messed up, and we can’t simply abolish all prisons without addressing the rest of the problems.

I had a student who said if he could change one thing about society’s perception of drug dealers, he’d destroy the stereotype of the drug dealer in an Armani suit. He said, “You try living in Oakland with three children and working at McDonalds; you can’t do it. Drug dealing puts food on the table.” Now he’s in prison which doesn’t help anybody.

Before I went to work in the prison system, I was completely apolitical on the drug war, because I never thought about it. But I became highly politicized because a lot of my students would have been perfectly fine neighbors as long as you either A) kept them off drugs, or B) made the drug legal like cigarettes. Many of my stdents did terrible things to get money for drugs, but if it had just been like cigarettes, they never would have murdered people.

One student was in because he was a marijuana dealer in the 1970s, and shot dead someone who tried to rob him. If he had been a shoe salesman and shot someone who tried to rob him, he wouldn’t have gone to jail for even one night, much less for the rest of his life.

A friend who was a police abolitionist went into communities known for police brutality, and got push back because the police are only one threat. The communities also have armed drug gangs, sometimes just as organized and just as nasty as the cops. The local people had no interest in police abolition until there was a community defense that made it practical. Similarly, Craig O’Hara said that anarchism is not about the eradication of all laws, but about making society such that you don’t need them. That’s it, exactly. You can’t push theoretical ideals at the expense of what people need for safety right now. I’ve seen anarchists get mad at women for calling the cops for rape!

I talked to Christian Parenti years ago about police. He observed that police have two functions: to stop meth addicts from bashing in the head of Grandma, and to bash in the heads of strikers. Two roles: to protect and serve, and to protect and serve the capitalists. Police like to emphasize the prior, whereas anti-police activists like to emphasize the latter. Parenti said they spend most of their time making sure people don’t drive 80 mph through a school zone. I don’t have a problem with someone getting a ticket for driving 80 mph through a school zone. But their most important social role is to bash in the heads of strikers.

We need to realize that our broad cultural conditions are really really, really terrible, and that something needs to be done about Ted Bundy until we have a society where Ted Bundys aren’t made.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2016 | Building Alternatives, Repression at Home, Toxification

Originally published in the September/October 2012 issue of Orion. Now republished for the first time online.

In an era of government-sanctioned polluters, communities must defend themselves

Several years ago I spoke at a benefit for an organization working to prevent a toxic waste site from being built in their community. Yet another toxic waste site, the organizers clarified, since there already was one. It should surprise no one that their community was primarily poor, primarily people of color, and that the toxic waste was being brought in so that distant corporations could reap bigger profits.

The organization had been fighting the dump for years, on every level, from filing lawsuits to holding protests to physically blockading the dump site. Several people at the benefit commented on the bizarre role that the police played in all of this. Many of the cops lived in the community and were themselves opposed to the toxic dump. But when they put on their uniforms and headed off to work, their jobs included arresting their neighbors who were trying to protect the neighborhoods where their own children lived and played.

We’ve all heard of dues-paying union cops busting the heads of strikers because their capitalist bosses tell them to. And of cops arresting protesters trying to prevent the cops’ own water supplies from being toxified (while of course not arresting the capitalists who are toxifying the water supplies). And I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s had fantasies that at the next economic summit or World Bank meeting, members of the police will experience an epiphany of conscience and realize they share class interests not with those they’re protecting but rather with those at whom they’re pointing their guns. And in this fantasy the police then turn as one to join the protesters and face their real enemy.

At the benefit we shared all sorts of fantasies like these, and we all laughed at how unrealistic they were. There have been instances in which the police have worked with the people to stop government or corporate atrocities, but they’re too rare.

And then we shared some other fantasies, which all consisted in one way or another of police choosing to enforce laws that are already on the books, laws that protect our communities. Laws like the Clean Air Act, or the Clean Water Act, or for that matter laws against rape. We fantasized about what it might be like to have police enforce carcinogen-free zones, or dam-free zones, or WalMart-free zones, or rape-free zones.

And then again we laughed, since we knew that these fantasies, too, were unrealistic. It’s not the job of the police to protect you from living in a toxified landscape, even if that landscape is being toxified illegally.

In fact — and this may or may not be surprising to you — the police are under no legal obligation to protect you at all. This fact has been upheld in courts again and again. In one case, two women in Washington DC were upstairs in their townhouse when they heard their roommate being assaulted downstairs. Several times they phoned 911 and each time were told police were on their way. A half hour later their roommate stopped screaming, and, assuming the police had arrived, they went downstairs. But the police hadn’t arrived, and so for the next fourteen hours all three women were repeatedly beaten and raped. The women sued the District of Columbia and the police for failing to protect them, but the district’s highest court ruled against them, saying that it is “a fundamental principle of American law that a government and its agents are under no general duty to provide public services, such as police protection, to any individual citizen.”

So there you have it. Time and again, many similar cases have yielded the same case law, at local, state, and federal levels. But a lot of rape victims already know this; only 6 percent of rapists spend even one night in jail. And the people in that community who were having a toxic waste dump crammed down their throats with the professional support of the police also know this. As do the human and nonhuman people of the Gulf of Mexico, who are still being killed or injured by the Deepwater catastrophe — and who will experience far more of the same, since the U.S. government is supporting more deepwater drilling. As one technical advisor to the oil and gas industry put it, “We are seeing deep-water drilling coming back with a vengeance in the Gulf.”

So here’s the question: if the police are not legally obligated to protect us and our communities — or if the police are failing to do so, or if it is not even their job to do so — then if we and our communities are to be protected, who, precisely is going to do it? To whom does that responsibility fall? I think we all know the answer to that one.

A lot of people seem to love to talk about the virtues of self- and community-reliance, but where are they when we need to defend our communities?

Fortunately there are many examples of communities rising up to defend themselves from wrongdoing from which we can and should learn. Pre-Revolutionary — or you could say revolutionary yet pre-1776 — American patriots, sick and tired of rule by a distant elite (sound familiar?), increasingly refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Crown Courts and other institutions, and put in place their own systems of justice. The same has been true for the Irish in their struggle for independence. The same was true of the Spanish anarchists: part of their project included pushing fascists out of their communities and another part consisted of putting in place their own neighborhood systems of justice and community protection.

I think often of something a former head of “security” for South Africa under apartheid said: that what they’d been most afraid of from the revolutionary group the African National Congress had never been the ANC’s sabotage or even their violence, but rather that the ANC might be able to convince the mass of South Africans to not believe in law and order as such, which in this case meant the law and order imposed by the apartheid regime, which in this case meant the legitimacy of the exploitative apartheid government, which in this case meant that their greatest fear was that the ANC would convince the majority of people to withdraw their consent to be governed by an elite that does not have their best interests at heart.

In our case, we don’t need an ANC to convince us of the illegitimacy of many of the actions of those in power. Those in power are doing a great job of convincing us by their own actions. If the Gulf catastrophe (and the continuation of deepwater drilling) doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If fracking and the poisoning of our groundwater doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the governmental response to global warming — ranging from vindictiveness against climate scientists to denial to measures that at very best are completely incommensurate with the threat — doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the total toxification of the environment, with its inevitable health consequences for both humans and nonhumans, doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. I routinely ask the people at my talks whether they have had someone they love die of cancer, and at least 75 percent almost always say yes.

And when I ask people at my talks if they believe that state and federal governments take better care of corporations or of human beings, no one — and I mean no one — ever says human beings. Reframing the question to consider whether governments take better care of corporations or the planet — our only home — yields the same result.

If police are the servants of governments, and if governments protect corporations better than they do human beings (and far better than they do the planet), then clearly it falls to us to protect our communities and the landbases on which we in our communities personally and collectively depend. What would it look like if we created our own community groups and systems of justice to stop the murder of our landbases and the total toxification of our environment? It would look a little bit like precisely the sort of revolution we need if we are to survive. It would look like our only hope.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 13, 2016 | Alienation & Mental Health

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

Featured image: Utah snow by Max Wilbert

Sitting on the patio at the Park City Library on a crisp September afternoon, I admire the beauty of this season’s new dusting of snow on mountains awash in the golds, reds, and greens of fall. I arrived in Park City last week thinking I will live in Utah again for the first time in almost 10 years.

The mountains’ timelessness makes it hard to believe it’s been 10 years since I packed my parents’ 1992 black Chevy suburban on a cold December night in Cedar City in 2005 before making the long drive to Iowa to be closer to my family in the Midwest. The joy that the sight of new snow has always produced for me makes it hard to believe its been 10 years since I last watched the good, thick Utah snow gather behind me to cloud the scene from my rear-view mirror as I pulled away softening the reminders of what and who I left behind.

Almost immediately after recognizing this beauty, I feel a deep pang of anxiety. I have been reading about the impacts climate change will have on Utah’s snow. I know, for example, that many scientists agree with Porter Fox, the author of DEEP: The Story of Skiing and the Future of Snow, that there will be no snow in Utah by the end of this century if climate change cannot be stopped.

My memories make it incredibly painful to imagine a Utah without snow, but this is the reality confronting us. Loving the snow as I do and understanding what the snow means to both humans and non-humans in Utah, I cannot help but call human-produced climate change “suicidal.”

***

I am intimately familiar with suicide. Sometime in the ten years after leaving Utah, I developed what my doctors have called “major depressive disorder.” When I was a public defender in Kenosha, WI, I tried to kill myself in April, 2013 and, again, in August, 2013.

I have spent the last two years trying to understand the darknesses that led me to attempt to take my own life those two times. I’ve always possessed a certain type of melancholy, but it takes more than a simple disposition for melancholy to develop suicidal depression.

Many theories exist for why I took the road to attempted suicides.

First, I have a history of traumatic head injuries including a brain contusion I suffered in a high school football game. I cannot remember what happened, but I do remember watching the game film the next morning and seeing my head bounce like a ball on the turf after I was knocked completely off my feet. I do not know if I suffered full-blown concussions playing college football at the University of Dayton, but I do remember my head hurting an awful lot. This theory supports the view that depression is truly a mental illness. My doctors tell me my brain struggles to recycle serotonin, and that this could be a result of the head injuries.

Another theory roots the depression I experience in my history of disconnection from any one place. I’ve never lived anywhere for long and this perpetual moving creates a feeling of spiritual vertigo for me. I was born in Evansville, IN, moved to Bedford, IN, moved to Salt Lake City, went to Cedar City, UT, re-joined my family in Waterloo, IA, headed to Dayton for college, then Madison, WI for law school, and on to Milwaukee to work in the public defender’s office. I lived in all of these places before I was 26. Each uprooting came with its own specific pains. Eventually, however, like a plant who will not take to new soil, I rejected the idea I could ever grow roots anywhere.

The final theory for my suicide attempts – and the one that makes the most sense to me – points to an overwhelming mixture of exhaustion, guilt, and despair I built as a public defender watching client after client dragged away to prison while I woke every morning to read news reports of ever more environmental destruction. I worked 60 and 70 hour weeks and it never seemed to matter. I could not keep my clients out of prison. I brought my case files home and some nights woke up at 3 AM to get a head start on the day. The more I lost, the stronger my feelings of guilt grew. It was my fault. I needed to work harder. The harder I worked, the more exhausted I became. The more exhausted I became, the harder it was to fight the guilt. The more guilt I felt, the harder I told myself I needed to work.

On top of this, I recognized – and still do – the fact that the planet’s life support systems are under attack by forces like climate change causing a growing number of scientists to predict human extinction by as soon as 2050. Carcinogens have seeped so deeply into the earth that every mother in the world has contaminants like dioxin in her breast milk; humans have successfully poisoned the most sacred physical bond between mother and child.

Meanwhile, nearly 50 percent of all other species are disappearing. Between 100-200 species a day are going extinct around the world. One quarter of the world’s coral reefs have been murdered. In the United States, alone, 95% of old growth forests are gone. In 70 countries worldwide there are no longer any original forests at all.

I often try to apologize for listing off these facts, or explain that perhaps I fixate on these things because I have a mental illness. I will not do that any longer. These atrocities are happening. Unless you are a sociopath, to truly contemplate these facts, to understand what they mean, to feel their implications comes with a profound emotional cost. I might have a mental illness, but it is natural to feel despair when confronted with the possibility of the destruction of all life on the planet.

***

I return to Utah after spending two years on the road supporting indigenous-led land-based environmental struggles. Why, just months after trying to commit suicide, did I set out for the front lines of the environmental movement?

Well, my experiences tell me that emotional states like despair, by themselves, are illusions and cannot hurt me on their own. Afflicted as I often am with a poor self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy, I learned that even when those thoughts arise, I do not have to entertain them. I can let them flash across the movie screen in my mind without ever attaching any meaning to them.

Despair by itself cannot kill me. I can kill me. Feeling the despair, I can grind several pills into powder, snort the powder to numb the pain, and then drink down the rest of the pills. Similarly, feeling the despair, I could put a gun to my temple or jump from a bridge. But, in each of these cases, it will not be the despair that kills me. It will be a physical action that kills me.

I find this realization to be deeply empowering. While I cannot always control my emotional state, I can control my actions. No matter how much despair I feel, I can refuse to act on that despair. Following this idea, I started to understand that I was not going to heal my mental illness with thoughts alone. I was not going to think my way out of depression. In order to heal, I needed to take tangible steps to alleviate the despair I was feeling.

First, I went up to central British Columbia to volunteer at the Unist’ot’en Camp. The Unist’ot’en Camp is an indigenous cultural center and pipeline blockade on the traditional, unceded territory of the Unist’ot’en clan of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation. I helped to build a bunkhouse on the precise GPS coordinates of a pipeline that would carry fossil fuels from the Fort McMurray tar-sands in Alberta over Unist’ot’en territory to a refinery in Kitimat, BC where the fossil fuels would be processed and shipped to be burned in markets world wide. I helped to break trails and walked the trapline on Unist’ot’en territory in the winter. Most of my time was spent sleeping on floors and couches in Victoria, BC as I volunteered for fundraising and organizing efforts to support the Camp.

I ran out of money in Canada and found it difficult to find work as a non-citizen, so I returned to my parents’ home in San Ramon, CA. Before long, though, I was encouraged to head to Hawai’i to write about Kanaka Maolis’ (native Hawaiians’) efforts to prevent the Thirty Meter Telescope from being constructed on the summit of their most sacred mountain, Mauna Kea. I spent 37 nights at 9,200 feet sleeping on the cold ground. I saw more snow than beaches in Hawai’i and was present when the police tried to force a way through 800 Kanaka Maoli as they blocked the construction equipment from gaining Mauna Kea’s summit. The police arrested 12 people that day, but were forced to turn back when boulders were rolled into the one road leading to the construction site.

Sometimes people try to thank me for my environmental activism. I always want to tell them not to thank me. I had to do it. All the thanks should go to the Unist’ot’en Clan and Kanaka Maoli for their bravery in protecting the Earth.

There’s a darker side to my decision to give up on a mainstream lifestyle to more effectively support environmental causes. I quit my job, gave up my apartment lease, sold my car, and broke up with the woman I was dating (a woman who stayed with me through the suicide attempts) in order to take off for Canada. It was not long before my money ran out and I was relying entirely on the generosity of others to help me along the way.

There are times when I wonder if it really is all that brave to turn my back on the normal responsibilities adults in this culture must attend to for basic survival. Getting a real job terrifies me. Maybe all I was doing on the road was avoiding putting my life back together after the suicide attempts?

***

While I ponder the snow from the Park City Library, I am reminded that I should be working on several of the online content writing gigs I have taken in an effort to re-build a sustainable income for myself. While I was on the road, I got sick of being broke. I became profoundly lonely for familiar places. I began to crave consistency in my day-to-day life.

I have a friend here in Park City, for example – the truest kind of friend who earned my trust after years of selfless communication and sincere concern for my well-being – who reminded me while I was on the road that I was always welcome in Utah. Her words were deeply encouraging, but I also knew I might not have enough money to get to Utah to see her. The truth is, to maintain relationships, you have to – at least sometimes – see those with whom you seek relationship.

The content writing gigs are a reminder of the long path facing me back to financial self-sufficiency. I would be lying if I did not confess the despair I sometimes feel when I realize just how out of control I let my personal life get. My student loans did not pay themselves. My resume can not magically produce an explanation for the hole in my work history. I still do not have enough money in my bank account to pay a first month rent and deposit to secure my own place to live.

Looking at my situation, the darkness begins to creep back in. I feel a deep sense of guilt wondering if I’ve sold out the environmental movement in order to build a community for myself. What right do I have to slow down right now? How can I look the Unist’ot’en Clan or Kanaka Maoli in the eye while their homes are under attack and I’m writing content for personal injury lawyers? Seeing the beauty of the snow on Park City’s peaks, knowing Utah may soon be too hot for snow to exist, why am I not running back to the front lines?

When these thoughts begin to spiral, I know I am in danger. I begin to hear that old whispering, suggesting a way out. I remember that there is a route to numb this confusion. It would not take too much of an effort to make it all fade away.

There the snow is again, though, and I know I will never try to kill myself again. I see the dark, heavy clouds weighing on the mountains’ shoulders. The chill in the air is a comfort because it brings the promise of water. As the powder spreads down the mountainsides, I know for another season, at least, there will be snowmelt, the streams will swell, and life will flourish across the land.

The snow in Park City brings a lesson. The snow is the future. Where there is snow, there is water and where there is water, there is life. Despair is the inability to see a livable future. Those who are destroying the planet are also destroying our future. When they clear-cut a forest, they clear-cut the future for those living in the forest. When they dam a river, they dam that river’s future. When they burn their fossil fuels and boil the Earth’s temperatures so that the snow in Park City disappears, they’re burning and boiling Park City’s future.

The snow, then, gives me my medicine for despair. The snow is the future. Fight for the snow, fight to ensure that the snow will continue to fall, and seeing the snow fall will bring the ability to see a livable future.

Colorado Plateau, southern Utah

Thoughts of suicide still sometimes fleet across my mind. Suicide’s mystique fades after you’ve gone through the spiritual process and the physical actions to produce your own death. The scariest part about it is that it really isn’t that scary at all. Suicide can come so easily.

But, the snow falls, and I know I cannot help the snow if I am dead. I am still engaged in war with my own demons and have had to re-consider my capacity, but if I can defeat those demons maybe I can become a stronger activist than I ever thought possible. The snow is too beautiful, the joy I feel seeing the snow is too strong, and the first stirrings of a feeling of belonging in Park City are too compelling for me to ever give in like that again.

Will Falk is a former public defender turned environmental writer and activist. He has been engaged in support for aboriginal sovereignty on the front lines at the Unist’ot’en Camp in so-called British Columbia and on Mauna Kea in Hawai’i. He is in the process of moving to Park City, Utah.

Keeping the spirit

Keeping the spirit Start with a small circle: each one invite one.

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.