by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 7, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action

In early October, news emerged that India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change was blocking the implementation of a high-level government panel’s report on tribal rights that recommended the creation of stringent rules to safeguard indigenous people from displacement. Meanwhile, two state governments have begun implementing a much different set of guidelines — issued in August without any interference — that allow the private sector to manage 40 percent of forests for profit at the expense of indigenous forest dwellers. In addition, another ordinance passed this year will permit private corporations to easily acquire land and forests from indigenous communities and carry out ecologically harmful mining. These legislative and policy decisions are usually made without the knowledge of indigenous communities whose lives, livelihoods and ecosystems will be worsened by these irresponsible actions of the government. Hence, indigenous communities in Uttar Pradesh, a northern state and Odisha, in the east, are strengthening their organizing to protect their rivers, lands, forests and hills from “development” that would displace thousands of local residents and destroy the environment.“People from my community and I were beaten, detained or jailed unnecessarily for opposing tree felling in our forests, some years ago,” said Nivada Debi, a feisty 38-year-old woman from the Tharu Adivasi community in Uttar Pradesh. “We visited the police station multiple times for their release. The government did not assist the injured. Despite the police and government indifference, we will fight for our land and environment.”A mother of four children subsisting on the forests, Debi is active in grassroots resistance that started nearly 20 years ago and has grown into the All India Union of Forest Working People, or AIUFWP. The group is made up of many indigenous people who subsist on forests and are collectively protecting forests from poachers and encroachers.

Debi was among hundreds — from the AIUFWP, the allied Save Kanhar Movement and other resistance groups — who traveled to Lucknow in July 2015 for a rally protesting the continued incarceration of their comrades fighting land grabbing in other districts of Uttar Pradesh. Roma Malik, the AIUFWP deputy general secretary, and Sukalo Gond, an Adivasi, which means original inhabitant, were among those arrested on June 30, before they were to address a large public gathering about the illegal land acquisition for the Kanhar dam and the violent repression of its opponents by the state. Another member of AIUFWP, Rajkumari, who prefers to go by her first name, was jailed on April 21, after 39 Adivasis and Dalits, who are considered outside the caste hierarchy, were brutally shot at by the police during a peaceful protest on April 18. The demonstration, which began on April 14 — the birthday of B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian constitution and an icon for many Indians, particularly Dalits — was opposing the construction of a dam across the Kanhar river in the Sonbhadra district of southeastern Uttar Pradesh.

Rajkumari was released toward the end of July while Gond and Malik were freed in September. However, others are still imprisoned on fabricated charges. Courts are delaying hearing their cases or denying them bail.

AIUFWP members, some of whom were previously involved with other local resistance movements, have been actively opposing the construction of the Kanhar dam for years. It would submerge over 10,000 acres of land from more than 110 villages in Uttar Pradesh and the neighboring states of Chattisgarh and Jharkhand, displacing thousands of local people and disrupting their lives and livelihoods. The dam was approved by the Central Water Commission of India in 1976, but was abandoned in 1989 after facing fierce opposition, especially from the local people whose lives and ecosystem would be destroyed by the proposed dam. However, construction resumed in December 2014, violating orders to stop it from the National Green Tribunal — a government body that adjudicates on environmental protection, forest conservation and natural resource disputes. No social impact assessment was done, nor were the necessary environmental or forest clearances — mandated by the Forest Conservation Act — obtained by the state government.

“Since this dam can destroy our survival and also adversely impact the surroundings, we have been opposing its construction and related land acquisition for many years,” said Shobha, a determined 42-year-old Dalit. “On December 23, 2014, the police caned some of our comrades when we were peacefully protesting the revival of building the dam earlier that month. However, the police falsely accused some leaders of our struggle of attacking the sub-divisional magistrate.” Shobha, who also prefers to go only by her first name, is among the vocal leaders of a women’s agricultural laborers union, which has allied with AIUFWP, in the village of Bada.

Around 400 miles from Sonbhadra, in the Kalahandi and Rayagada districts of southern Odisha, live the Dongria Kondhs, an indigenous community of over 8,000 people. They have been fighting tirelessly to protect their sacred mountain, the nearly 5,000-foot high Niyamgiri, from large private corporations — like Vedanta Limited — that are trying to mine bauxite in the area to produce aluminum. Supporters of the Dongria Kondhs were arrested in Delhi on August 9 outside the Reserve Bank of India, as they peacefully highlighted Vedanta’s illegitimate and harmful mining in the Niyamgiri. Vedanta’s mining would violate the Forest Rights Act, which states that indigenous communities are entitled to remain in the forests — and utilize the produce, land and water in the forests — while conserving and protecting them.

“The Niyamgiri symbolizes a parent to our community,” said Sadai Huika, a steadfast 45-year-old Dongria Kondh woman from Tikoripada village. “While the streams that originate from it help our farming, the plants and grass that grows on it feed our cattle and goats. We cannot exist without it and will safeguard it from anyone trying to harm it.”

Huika and people from hundreds of villages near the Niyamgiri are active members of the Niyamgiri Protection Forum, which originated around 2003 to resist attempts by Vedanta to begin mining where the Kondhs live, with the support of the Odisha state government. At every one of the 12 village council meetings with government officers held in 2013 atop the Niyamgari, community members stated that they would not allow mining nearby.

Kumuti Majhi, an elderly Dongria Kondh man and one of the forum’s leaders, is among the few people who have traveled within and outside Odisha to advocate against mining and garner vital support for their struggle. He has met ministers to explain how significant the Niyamgiri is to his community and their reasons for safeguarding it.

By organizing protests locally and with allies around the world — and meetings with Vedanta’s shareholders and empathetic government officials, who the forum has enlightened about the need to protect the Niyamgiri — the group has stalled the mining.

“We know that extracting bauxite from the Niyamgiri will pollute our environment and also affect all living beings here,” Majhi said. “Hence, we will stop anyone coming to plunder the Niyamgiri, despite police harassment and false charges against us and our families.”

Pushpa Achanta is a Bangalore-based freelance journalist, blogger and writer on development and human interest issues. She is the lead author of a book titled Ripples: The Right to Water and Sanitation for Whom, published in July 2013 by the Indian Social Institute in Bangalore. Her articles have appeared in collections of essays and features on different subjects. She also enjoys penning verse, taking nature photography and mentoring youth.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 6, 2015 | Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the second in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the first part.

- Gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014.

- Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of local communities.

- With gold prices continuing to rise overall despite recent drops and Suriname’s political economy deeply entrenched in resource extraction, conservationists worry mining expansion will be hard to stop.

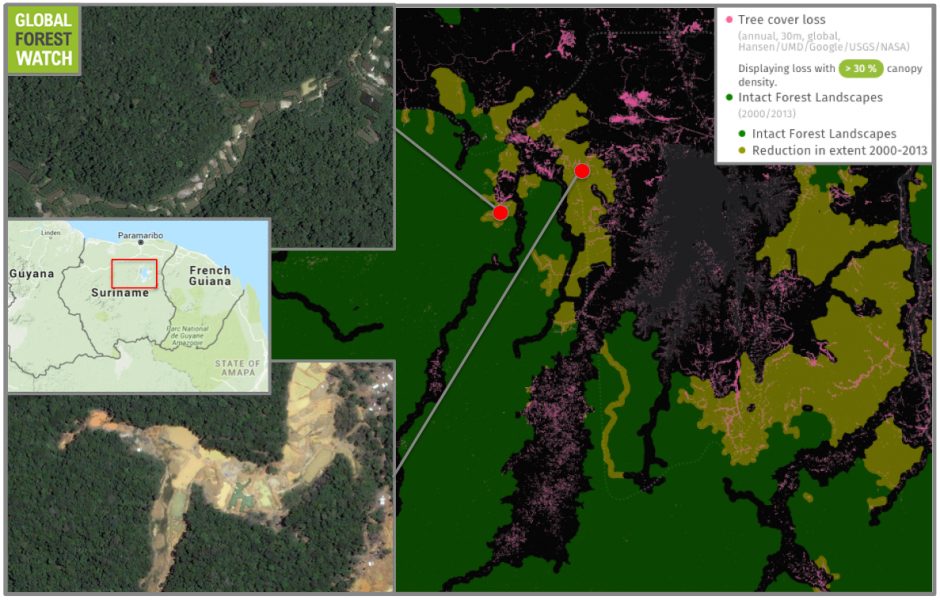

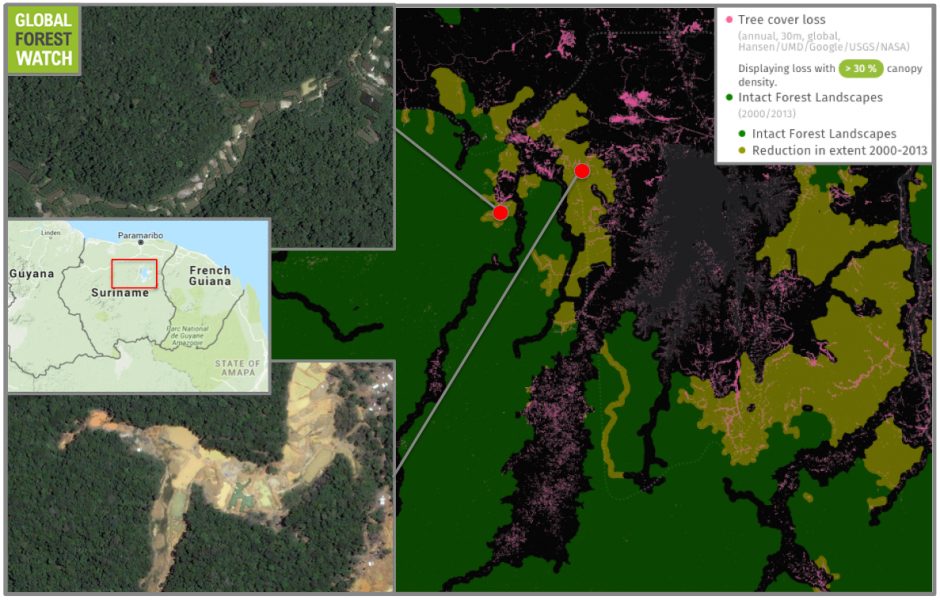

High gold prices combined with lax land use regulations have led to an explosion in mining in Suriname. A recent report by the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) finds that gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014, and is threatening the health and ways of life of many communities in the region.

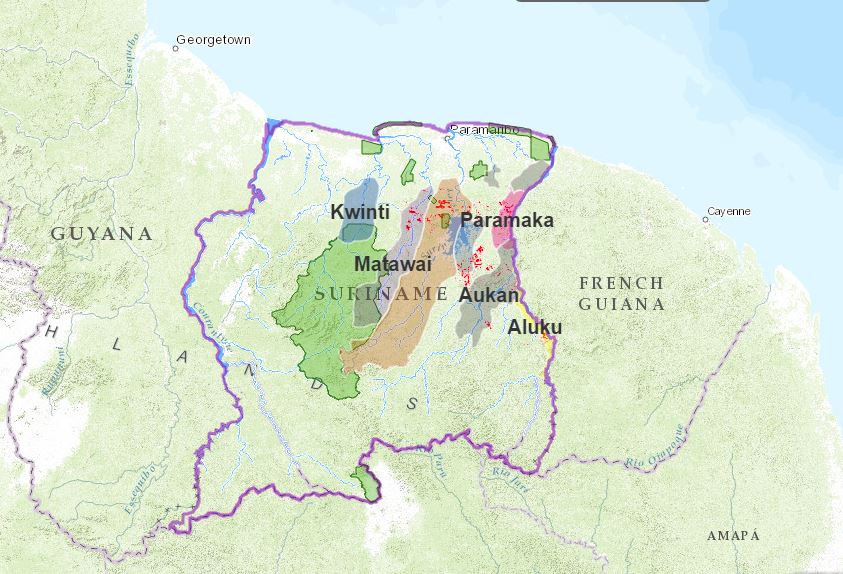

Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of the Maroons – descendants of formerly enslaved people of African heritage who escaped from plantations during Dutch colonial rule and established thriving communities in the country’s hinterlands after successfully fighting for their freedom.

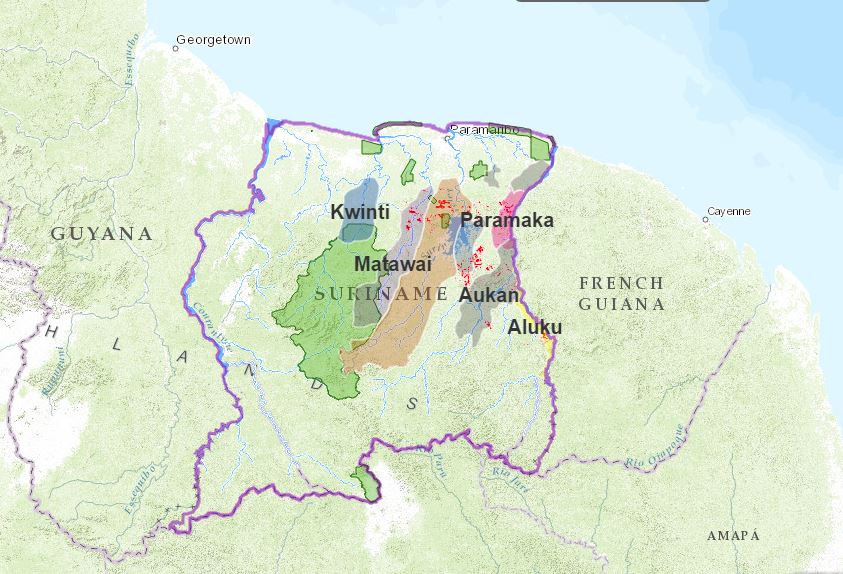

Suriname’s six main Maroon communities all reside along rivers leading upstream deep into the rainforest, the report says. The majority of Maroons live in the central-eastern part of the country – where the mineral-rich Greenstone Belt and gold deposits are located. Through statistical analysis, the ACT discovered that encroachment of gold mining is significantly more severe within Maroon territories than outside of them. The team writes that only one Maroon community far from the Greenstone Belt is currently not seeing any gold mining on their lands.

Suriname boasts large tracts of intact forest landscapes (IFLs), which are continuous, undisturbed areas of primary forest. However, Global Forest Watch shows significant IFL degradation, with the country experiencing nearly 17,000 hectares of tree cover loss in its IFLs between 2001 and 2014. Much of this is happening in areas with gold mining activity.

Mining extent (red) in Maroon-occupied areas. Image courtesy of the ACT.

For some Maroon groups, small-scale gold mining has become a major component of their landscape and their daily lives. In many of their villages – particularly in Paramaka, Aukan and Matawai communities – villagers have become economically dependent on gold mining. Anthropologist Marieke Heemskerk has shown that in some Maroon villages, 70 to 80 percent of households get their regular income from family members working in gold mines. Villagers with informal concessions are able to collect fees from the garimpeiros – the Brazilian miners – and others working on their lands, and some have become quite wealthy as a result.

The Matawai Maroons who live along the Saramacca River in central Suriname, are among the smallest of the Maroon communities in terms of population. Their territory covers about 560,000 hectares and many of their villages are among the most remote and least-known in the country. Consequently, the Saramacca River, the surrounding ecosystem and the villages themselves remained relatively quiet and peaceful while other Maroon communities were contending with the pressures of inland colonization and resource extraction.

The northern portion of the Matawai territory, however, is located in the reaches of the Greenstone Belt. Being close to populated settlements, they are easily accessible via roads. This has allowed rapid expansion, with a number of the northern Matawai villages located at ground-zero for Suriname gold mining.

“According to our calculations derived from deforestation data, 81.51% of all deforestation in the Matawai territory is due to gold mining,” the report says.

Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.

Four Matawai villages – Nyun Jakobkondre, Balen, Misalibi, and Bilawatra have been particularly impacted by the large gold mines that encircle them. In fact, much of the small-scale mining in the region is done by Maroons themselves, which is threatening their traditional livelihoods of hunting, fishing, woodworking, etc.

“As more Maroons in the Matawai community and elsewhere are becoming dependent on partaking in mining for household income, these and other local practices are eroding,” said Rudo Kemper, GIS and Web Development Coordinator for the ACT. “Many of the Matawai youth in particular are no longer as interested in traditional activities, as they know that there are lucrative profits to be made working in the mines.”

To make matters worse, mining activities has polluted waterways with mercury, which is used to separate the gold ore from sediment. Mercury can act as a neurotoxin, and has contaminated river fish, which are no longer safe to eat. Arable land is also threatened. According to Kemper, “in areas like Nyun Jakobkondre, the gold mining is taking place so close to the village that fertile land for cultivation is becoming scarcer.”

Nieuw Koffiekamp, a village settled by Maroons after it was relocated because of floods, is now located right in the middle of one of the most prosperous and mineral-rich veins of the Greenstone Belt. Known as Gros Rosebel, the area was one of the first industrial mining concessions in Suriname. Villagers have been using the area for sustainable livelihoods for generations, but the ACT report alleges they were neither consulted with nor informed about the concession. Years later, the government set up a task force dedicated to relocating the village once more. The village continues to fight for its existence, despite being literally fenced in by gold mining activity. Community members argue they have the right to extract resources from their own land and thus participate in small-scale gold mining.

Even Brownsberg Nature Park, a 14,000-hectare reserve and popular tourist destination, hasn’t been spared from the clutches of mining. From early on, gold miners have been active within its boundaries, where an estimated 924 hectares of primary forest has been lost to gold mining. In 2012, deforestation in the park reached an all-time high, with 200 hectares of forest cleared. In that same year, public awareness about mining inside Brownsberg began increasing when WWF–Guianas published a report with aerial photography of the damage to the park. “Since then,” Kemper said, “the rates of small-scale mining in the boundaries of the park have dropped somewhat, although deforestation caused by mining in the park [continues] to expand.”

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining boom threatens communities in Suriname

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 4, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

By Chris Mooney / The Washington Post

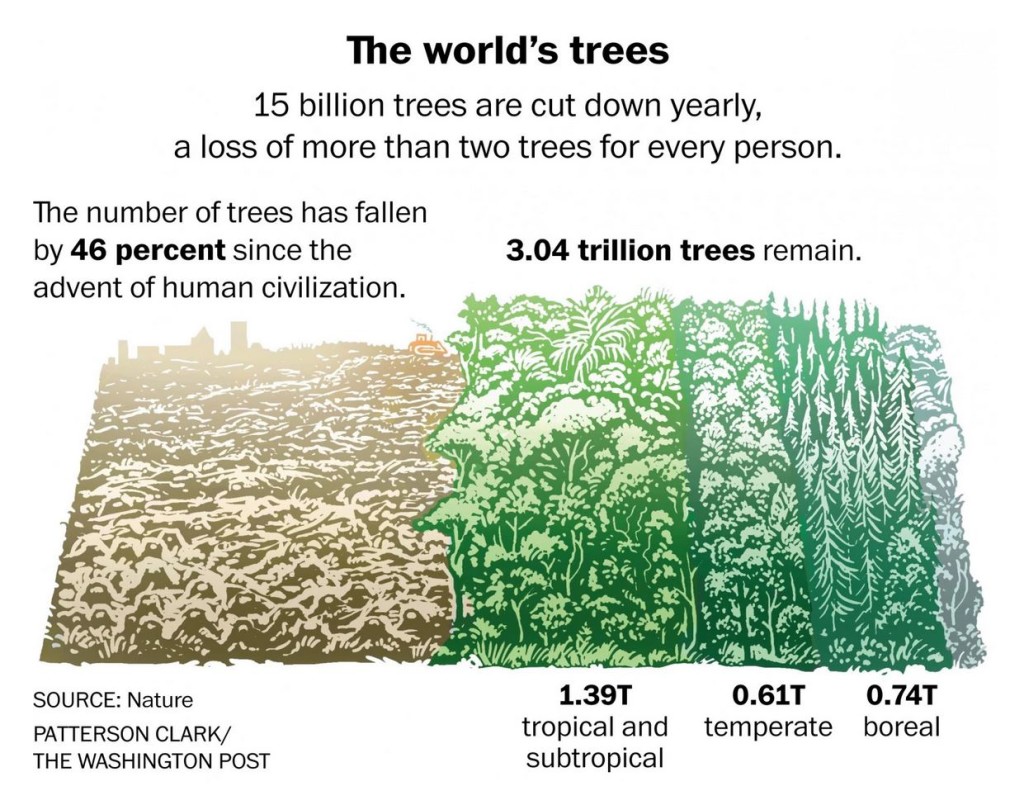

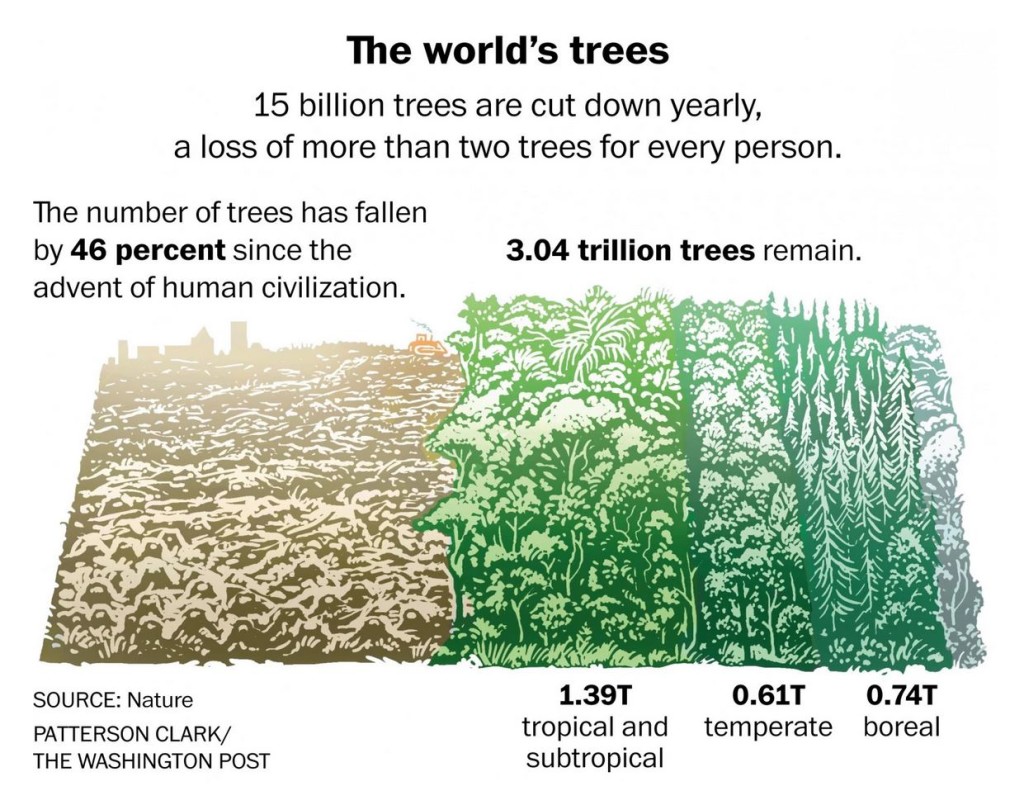

In a blockbuster study released Wednesday in Nature, a team of 38 scientists finds that the planet is home to 3.04 trillion trees, blowing away the previously estimate of 400 billion. That means, the researchers say, that there are 422 trees for every person on Earth.

However, in no way do the researchers consider this good news. The study also finds that there are 46 percent fewer trees on Earth than there were before humans started the lengthy, but recently accelerating, process of deforestation.

“We can now say that there’s less trees than at any point in human civilization,” says Thomas Crowther, a postdoctoral researcher at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies who is the lead author on the research. “Since the spread of human influence, we’ve reduced the number almost by half, which is an astronomical thing.”

Read more at The Washington Post

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 8, 2015 | Agriculture

By Joshua E. Brown / University of Vermont

A new study shows that removing native forest and starting intensive agriculture can accelerate erosion so dramatically that in a few decades as much soil is lost as would naturally occur over thousands of years.

Had you stood on the banks of the Roanoke, Savannah, or Chattahoochee Rivers 100 years ago, you’d have seen a lot more clay soil washing down to the sea than before European settlers began clearing trees and farming there in the 1700s. Around the world, it is well known that deforestation and agriculture increases erosion above its natural rate.

But accurately measuring the natural rate of erosion for a landscape — and, therefore, how much human land use has accelerated this rate — has been a devilishly hard task for geologists. And that makes environmental decision-making — such as setting allowable amounts of sediment in fish habitat and land use regulation — also difficult.

Now research on these three rivers and seven other large river basins in the U.S. Southeast has, for the first time, precisely quantified this background rate of erosion. The scientists made a startling discovery: rates of hillslope erosion before European settlement were about an inch every 2,500 years, while during the period of peak land disturbance in the late 1800s and early 1900s, rates spiked to an inch every 25 years.

“That’s more than a hundred-fold increase,” says Paul Bierman, a geologist at the University of Vermont who co-led the new study with his former graduate student and lead author Luke Reusser, and geologist Dylan Rood at Imperial College, London. “Soils fall apart when we remove vegetation,” Bierman says, “and then the land erodes quickly.”

Their study was presented online Jan. 7 in the February issue of the journal Geology. Their work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Precious resource

“Our study shows exactly how huge an effect European colonization and agriculture had on the landscape of North America,” says Dylan Rood. “Humans scraped off the soil more than 100 times faster than other natural processes!”

Along the southern Piedmont from Virginia to Alabama — that stretch of rolling terrain between the Appalachian Mountains and the coastal plain of the Atlantic Ocean — clay soils built up for many millennia. Then, in just a few decades of intensive logging, and cotton and tobacco production, as much soil eroded as would have happened in a pre-human landscape over thousands of years, the scientists note. “The Earth doesn’t create that precious soil for crops fast enough to replenish what the humans took off,” Rood says. “It’s a pattern that is unsustainable if continued.”

The scientist collected 24 sediment samples from these rivers — and then applied an innovative technique to make their measurements. From quartz in the sediment, Bierman and his team at the University of Vermont’s Cosmogenic Nuclide Laboratory extracted a rare form of the element beryllium, an isotope called beryllium-10. Formed by cosmic rays, the isotope builds up in the top few feet of the soil. The slower the rate of erosion, the longer soil is exposed at Earth’s surface, the more beryllium-10 it accumulates. Using an accelerator mass spectrometer at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the geologists measured how much beryllium-10 was in their samples — giving them a kind of clock to measure erosion over long time spans.

These modern river sediments revealed rates of soil loss over tens of thousands of years. This allowed the team to compare these background rates to post-settlement rates of both upland erosion and downriver sediment yield that have been well documented since the early 1900s across this Piedmont region.

While the scientists concluded that upland erosion was accelerated by a hundred-fold, the amount of sediment at the outlets of these rivers was increased only about five to ten times above pre-settlement levels, meaning that the rivers were only transporting about six percent of the eroded soil. This shows that most of the material eroded over the last two centuries still remains as “legacy sediment,” the scientists write, piled up at the base of hillslopes and along valley bottoms.

“There’s a huge human thumbprint on the landscape, which makes it hard to see what nature would do on its own,” Bierman says, “but the beauty of beryllium-10 is that it allows us to see through the human fingerprint to see what’s underneath it, what came before.”

“This study helps us understand how nature runs the planet,” he says, “compared to how we run the planet.”

Soil conservation

And this knowledge, in turn, can “help to inform land use planning,” Bierman says. “We can set regulatory goals based on objective data about how the landscape used to work.” Often, it is difficult to know whether conservation strategies — for example, regulations about TMDL’s (total maximum daily loads) of sediment — are well fitted to the geology and biology of a region. “In other words, an important unsolved mystery is: “How do the rates of human removal compare to ‘natural’ rates, and how sustainable are the human rates?” Rood asks.

While this new study shows that erosion rates were unsustainable in the recent past, “it also provides a goal for the future,” Rood says. “We can use the beryllium-10 erosion rates as a target for successful resource conservation strategies; they can be used to develop smart environmental policies and regulations that will protect threatened soil and water resources for generations to come.”

From University of Vermont: http://www.uvm.edu/~uvmpr/?Page=news&&storyID=19904

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 6, 2014 | Defensive Violence, Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization

By The Women’s Coordinating Committee for a Free Wallmapu

What can only be described as an act of defiance against the State of Siege imposed by the Chilean State was carried out this morning (December 31st), against the Chilean occupation and its Capitalist plunder in the province of Malleco.

The events took place nearby the town of Angol, a small distance away from a police station. It involved the complete arson of a helicopter belonging to Mininco Forestry Inc, and the partial damage of another.

The events also included the alleged assault of a police officer, who was subdued by the “assailants,” according to various media reports.

We should remember that the Chilean government had ordered more police presence to Mapuche territory, in which several reinforcements were brought from various parts of the country. This also included the use of surveillance planes, or drones, with infrared cameras and heat detectors, in order to control and monitor the movement in the area, especially at night.

Nothing worked; the permanent police presence used to prevent unidentified people from entering site proved to be a dismal failure. A private contractor is used to maintain planes and other equipment for Mininco Forestry Inc, where the two planes were set on fire, destroying one and damaging the other.

Second Helicopter Attack in the Area

This is the second time that Forestry planes have been targeted in the area of Malleco. An earlier incident included a helicopter that was shot in a rural area of Ercilla.

Forestry Companies: The Ugliest Face of Capitalism in Wallmapu

The forestry companies represent the worst aspect that Capitalism has shown to Mapuche community members in Wallmapu. Their extreme extractive activities have only generated disaster for communities, including toxic fumes, the disappearance of rivers, brooks and streams, as well as the extinction of the natural flora and fauna of the area which serve as food and medicine for the Mapuche People. These are the main effects, among others, of the industry financed by the Chilean State through Law 701.

Moreover, the enormous extensions of land currently held by the Forestry companies lie on stolen land from Mapuche communities. These corporate properties are directly related to the territorial plunder of the Mapuche People.

Three Families against a People

This business not only is targeted against the Mapuche People; it also excludes the thousands of Chileans that have maintained this industry through subsidized taxes for the last 20 years. The property concentrated by the forestry industry lies in the hands of only three families: Angelini, Matte and Carey, whom own companies such as Bosques Arauco, CMPC and Masisa respectively.

Bosques Arauco alone encompasses almost 1.2 million hectares, with Mininco Forestry Inc at 700,000 hectares, which does not include the many uncertified estates in the area.

According to an official report, the forestry companies posses almost three million hectares in southern Chile – in other words – Wallmapu. This accounts to almost 30% of our traditional Mapuche Territory [south of the Bio Bio River], in comparison with only 700,000 hectares held by Mapuche communities, accounting for only 7% of traditional territory.

From Warrior Publications: http://wccctoronto.wordpress.com/2013/12/31/mapuche-resistance-defies-the-state-of-siege/