by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling

by Jen Moore / Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Stories of bloody, degrading violence associated with Canadian mining operations abroad sporadically land on Canadian news pages. HudBay Minerals, Goldcorp, Barrick Gold, Nevsun and Tahoe Resources are some of the bigger corporate names associated with this activity. Sometimes our attention is held for a moment, sometimes at a stretch. It usually depends on what solidarity networks and under-resourced support groups can sustain in their attempts to raise the issues and amplify the voices of those affected by one of Canada’s most globalized industries. But even they only tell us part of the story, as Todd Gordon and Jeffery Webber make painfully clear in their new book, The Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America (Fernwood Publishing, November 2016).

“Rather than a series of isolated incidents carried out by a few bad apples,” they write, “the extraordinary violence and social injustice accompanying the activities of Canadian capital in Latin America are systemic features of Canadian imperialism in the twenty-first century.” While not completely focused on mining, The Blood of Extraction examines a considerable range of mining conflicts in Central America and the northern Andes. Together with a careful review of government documents obtained under access to information requests, Gorden and Webber manage to provide a clear account of Canadian foreign policy at work to “ensure the expansion and protection of Canadian capital at the expense of local populations.”

Fortunately, the book is careful, as it must be in a region rich with creative community resistance and social movement organizing, not to present people as mere victims. Rather, by providing important context to the political economy in each country studied, and illustrating the truly vigorous social organization that this destructive development model has awoken, the authors are able to demonstrate the “dialectic of expansion and resistance.” With care, they also show how Canadian tactics become differentiated to capitalize on relations with governing regimes considered friendly to Canadian interests or to try to contain changes taking place in countries where the model of “militarized neoliberalism” is in dispute.

The spectacular expansion of “Canadian interests” in Latin America

We are frequently told Canadian mining investment is necessary to improve living standards in other countries. Gordon and Webber take a moment to spell out which “Canadian interests” are really at stake in Latin America—the principal region for Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) in the mining sector—and what it has looked like for at least two decades: “liberalization of capital flows, the rewriting of natural resource and financial sector rules, the privatization of public assets, and so on.”

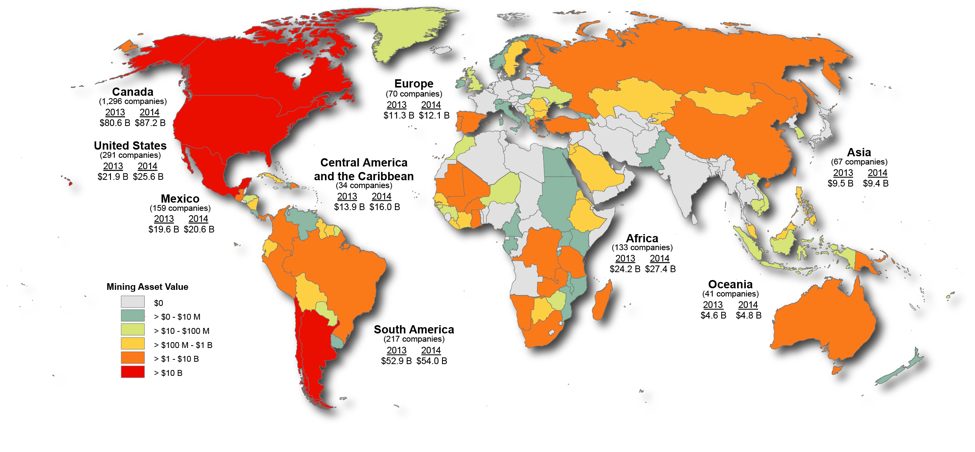

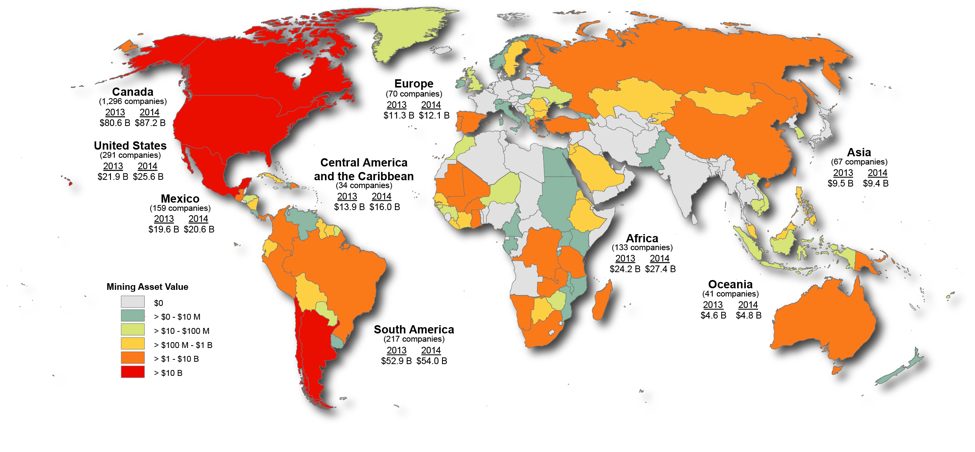

Cumulative CDIA in the region jumped from $2.58 billion in stock in 1990 to $59.4 billion in 2013. These numbers are considerably underestimated, the authors note, since they do not include Canadian capital routed through tax havens. In comparison, U.S. direct investment in the region increased proportionately about a quarter as much over the same period. Despite having an economy one-tenth the size of the U.S., Canadian investment in Latin America and the Caribbean is about a quarter the value of U.S. investment, and most of it is in mining and banking.

Canadian mining investment abroad

To cite a few of the statistics from Gordon and Webber’s book, Latin America and the Caribbean now account for over half of Canadian mining assets abroad (worth $72.4 billion in 2014). Whereas Canadian companies operated two mines in the region in 1990, as of 2012 there were 80, with 48 more in stages of advanced development. In 2014, Northern Miner claimed that 62% of all producing mines in the region were owned by a company headquartered in Canada. This does not take into consideration that 90% of the mining companies listed on Canadian stock exchanges do not actually operate any mine, but rather focus their efforts on speculating on possible mineral finds. This means that, even if a mine is eventually controlled by another source of private capital, Canadian companies are very frequently the first face a community will see in the early stages of a mining project.

The results have been phenomenal “super-profits” for private companies like Barrick Gold, Goldcorp and Yamana, who netted a combined $2.8-billion windfall in 2012 from their operating mines, according to the authors. (Canadian mining companies earned a total of $19.3 billion that year.) Between 1998 and 2013, the authors calculate that these three companies averaged a 45% rate of profit on their operating mines when the Canadian economy’s average rate of profit was 11.8%.

Compare this to Canada’s miserly Latin American development aid expenditures of $187.7 million in in 2012—a good portion of this destined for training, infrastructure and legislative reform programs intended to support the Canadian mining sector. Or consider that the same year $2.8 billion was taken out of Latin America by three Canadian mining firms, remittances back to the region from migrants living in Canada totalled only $798 million (much more than Canadian aid).

Without spelling out the long-term social and environmental costs of these operations—costs that are externalized onto affected communities—or going into the problematic ways that private investment and Canadian aid can be used to condition local support for a mine project, Gordon and Webber posit that “super-profits” may be precisely the “Canadian interests” the government’s foreign policy apparatus is set up to defend—not authentic community development, lasting quality jobs or a reliable macroeconomic model.

State support for “militarized neoliberalism”

The argument that the role of the Canadian state is “to create the best possible conditions for the accumulation of profit” is central to Gordon and Webber’s book. From the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) down, Canadian agencies and foreign policy have been harnessed to justify “Canadian plunder of the wealth and resources of poorer and weaker countries.” Furthermore, they write, Canada has actively supported the advancement of “militarized neoliberalism” in the region, as country after country has returned to extractive industry, and export-driven and commodity-fuelled economic growth, which comes with high costs for affected-communities and other macroeconomic risks:

The extractive model of capitalism maturing in the Latin American context today does not only involve the imposition of a logic of accumulation by dispossession, pollution of the environment, reassertion of power of the region by multinational capital, and new forms of dependency. It also, necessarily and systematically involved what we call militarized neoliberalism: violence, fraud, corruption, and authoritarian practices on the part of militaries and security forces. In Latin America, this has involved murder, death threats, assaults and arbitrary detention against opponents of resource extraction.

The rapid and widespread granting of mining concessions across large swaths of territory (20% of landmass in some countries), regardless of who lives there or how they might value different lands, water or territory, has provoked hundreds of conflicts and powerful resistance from the community level upward. In reaction, and in order to guarantee foreign investment, in many parts of the region states have intensified the demonization and criminalization of land- and environment-defenders, while state armed forces have increased their powers, and para-state armed forces expanded their territorial control.

Far from being a countervailing force to this trend, the Canadian state has focused its aid, trade and diplomacy on those countries most aligned with its economic interests. It is not unusual to see public gestures of friendship or allegiance toward governments “that share [Canada’s] flexible attitude towards the protection of human rights,” such as Mexico, post-coup Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia. Meanwhile, Canada has used diverse tactics (in Venezuela and Ecuador, for example) to contain resistance and influence even modest reforms.

Canada’s ‘whole-of-government’ approach in Honduras

One of the more detailed examples in Blood of Extraction of Canadian imperialism in Central America covers Canada’s role in Honduras following the military-backed coup in June 2009. Documents obtained from access to information requests provide new revelations and new clarity into how Canadian authorities tried to take advantage of the political opportunities afforded by the coup to push forward measures that favour big business. Once again, though other economic sectors are discussed, mining takes centre stage.

After the terrible experience of affected communities with Goldcorp’s San Martin mine (from the year 2000 onward), Hondurans successfully put a moratorium on all new mining permits pending legal reforms promised by former president José Manuel Zelaya. On the eve of the 2009 coup, a legislative proposal was awaiting debate that would have banned open-pit mining and the use of certain toxic substances in mineral processing, while also making community consent binding on whether or not mining could take place at all. The debate never happened.

Instead, shortly after the coup, and once a president more friendly to “Canadian interests” was in place following a questionable election, the Canadian lobby for a new mining law went into high gear. A key goal for the Canadian government, according to an embassy memo, was “[to facilitate] private sector discussions with the new government in order to promote a comprehensive mining code to give clarity and certainty to our investments.” Another embassy record said that mining executives were happy to assist with the writing of a new mining law that would be “comparable to what is working in other jurisdictions” and developed with a resource person with whom their “ideologies aligned.”

In a highly authoritarian and repressive context, and under the deceptive banner of corporate social responsibility, the Canadian Embassy—with support from Canadian ministerial visits, a Honduran delegation to the annual meeting of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), and overseas development aid to pay for technical support—managed to get the desired law passed in early 2013, lifting the moratorium. Then, in June 2014, with full support from Liberals and Conservatives in the House of Commons and the Senate, Canada ratified a free trade agreement with Honduras, effectively declaring that “Honduras, despite its political problems, is a legitimate destination for foreign capital,” write Gordon and Webber.

Contrary to the prevailing theory in Canada that sustaining and increasing economic and political engagement with such a country will lead to improved human rights, the social and economic indicators in Honduras have gotten worse. Since 2010, the authors note, Honduras has the worst income distribution of any country in Latin America (it is the most unequal region in the world). Poverty and extreme poverty rates are up by 13.2% and 26.3%, respectively, after having fallen under Zelaya by 7.7% and 20.9%. Compounding this, Honduras is now the deadliest place to fight for Indigenous autonomy, land, the environment, the rule of law, or just about any other social good.

A strategy of containment in Correa’s Ecuador

In contrast to how Canada has more strongly aligned itself with Latin American regimes openly supportive of militarized neoliberalism, the experience in Ecuador under the administration of President Rafael Correa illustrates how Canada considers “any government that does not conform to the norms of neoliberal policy, and which stretches, however modestly, the narrow structures of liberal democracy…a threat to democracy as such.”

In the chapter on Ecuador, Gordon and Webber provide a detailed account of Canada’s “whole-of-government” approach to containing modest reforms advanced by Correa and undermining the opposition of affected communities and social movements to opening the country to large-scale mining. A critical moment in this process occurred in mid-2008, when a constitutional-level decree was issued in response to local and national mobilizations against mining. The Mining Mandate would have extinguished most or all of the mining concessions that had been granted in the country without prior consultation with affected communities, or that overlapped with water supplies or protected areas, among other criteria. It also set in place a short timeline for the development of a new mining law.

The Canadian embassy immediately went to work. Meetings between Canadian industry and Ecuadorian officials, including the president, were set up to ensure a privileged seat at talks over the new mining law. Gordon and Webber’s review of documents obtained under access to information requests further reveals that the embassy even helped organize pro-mining demonstrations together with industry and the Ecuadorian government. Embassy records describe their intention “to create sympathy and support from the people” as part of a “a pro-image campaign,” which included “an aggressive advertisement campaign, in favour of the development of mining in Ecuador.” Meanwhile, behind closed doors, industry threatened to bring international arbitration against Ecuador under a Canada–Ecuador investor protection agreement (which a couple of investors eventually did).

Ultimately, the authors conclude, Canadian diplomacy “played no small part” in ensuring that the Mining Mandate was never applied to most Canadian-owned projects, and that a relatively acceptable new mining law was passed in early 2009. While embassy documents show the Canadian government considered the law useful enough to “open the sector to commercial mining,” it was still not business-friendly enough, particularly because of the higher rents the state hoped to reap from the sector. As a result, the embassy kept up the pressure, including using the threat of withholding badly needed funds for infrastructure projects until mining company concerns were addressed and dialogue opened up with all Canadian companies.

Not discussed in The Blood of Extraction, we also know the pressure from Canadian industry continued for many more years, eventually achieving reforms, in 2013, that weakened environmental requirements and the tax and royalty regime in Ecuador. Meanwhile, as the door opened to the mining industry, mining-affected communities and supporting organizations were feeling the walls of political and social organizing space cave in, as they faced persistent legal persecution and demonization from the state itself, while the serious negative impacts of the country’s first open-pit copper mine started to be felt.

Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy”

The Blood of Extraction is a helpful portrait of “the drivers behind Canadian foreign policy.” Gordon and Webber lay bear “a systematic, predictable, and repeated pattern of behaviour on the part of Canadian capital and the Canadian state in the region,” along with its systemic and almost predictable harms to the lives, wellbeing and desired futures of Indigenous peoples, communities and even whole populations. They call it Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy.”

The problem is not Goldcorp or HudBay Minerals, Tahoe Resources or Nevsun. These companies are all symptoms of a system on overdrive, fuelling the overexploitation of land, communities, workers and nature to fill the pockets of a small transnational elite based principally in the Global North. If we cannot see how deeply enmeshed Canadian capital is with the Canadian state—how “Canadian interests” are considered met when Canadian-based companies are making super-profits, even through violent destruction—we cannot get a sense of how thoroughly things need to change.

Jen Moore is the Latin America Program Coordinator at Mining Watch Canada, working to support communities, organizations and networks in the region struggling with mining conflicts.

This article was published in the November/December 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 9, 2016 | Mining & Drilling

Featured image by Tony Webster / Flickr

by Steve Horn / Desmog

In the two months leading up to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ decision to issue to the Dakota Access pipeline project an allotment of Nationwide 12 permits (NWP) — a de facto fast-track federal authorization of the project — an army of oil industry players submitted comments to the Corps to ensure that fast-track authority remains in place going forward.

This fast-track permitting process is used to bypass more rigorous environmental and public review for major pipeline infrastructure projects by treating them as smaller projects.

Oil and gas industry groups submitted comments in response to the Corps’ June 1 announcement in the Federal Register that it was “requesting comment on all aspects of these proposed nationwide permits” and that it wanted “comments on the proposed new and modified NWPs, as well as the NWP general conditions and definitions.” Based on the comments received, in addition to other factors, the Corps will make a decision in the coming months about the future of the use of the controversial NWP 12, which has become a key part of President Barack Obama’s climate and energy legacy.

Beyond Dakota Access, the Army Corps of Engineers (and by extension the Obama Administration) also used NWP 12 to approve key and massive sections of both Enbridge’s Flanagan South pipeline and TransCanada’s southern leg of theKeystone XL pipeline known as the Gulf Coast Pipeline. Comments submitted as a collective by environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, National Wildlife Federation, several 350.org local chapters, the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, Corporate Ethics International, and others, allege NWP 12 abuses by the Obama administration.

Image Credit: Regulations.gov

The groups say NWP was never intended to authorize massive pipeline infrastructure projects and that that kind of permitting authority should no longer exist. Instead, they argued in their August 1 comment, federal agencies should be required to issue Clean Water Act Section 404 permits and do a broader environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

“Simply put, the Congress did not intend the NWP program to be used to streamline major infrastructure projects like the Gulf Coast Pipeline, the Flanagan South Pipeline, and the Dakota Access Pipeline,” reads their comment. “For the reasons explained herein, we strongly oppose the reissuance of NWP 12 and its provisions that allow segmented approval of major pipelines without any project-specific environmental review or public review process.”

“Oil companies have been using this antiquated fast-track permit process that was not designed to properly address the issues of mega-projects such as the Dakota Access pipeline,” Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Networkstated in the environmental groups’ press release at the closing of the NWP 12 comment period. “Meanwhile, tribal rights to consultation have been trampled and Big Oil is allowed to put our waters, air and land at immense risk. This cannot continue, it’s time for an overhaul.”

Industry groups, on the other hand, made their own arguments for the status quo.

Industry: Keep NWP 12 Alive, Presidential Campaign Ties

Many industry groups chimed in on the future of NWP 12. They included the American Petroleum Institute (API), Ohio Oil and Gas Association, West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association, Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, the Baker Botts Texas Industry Project (a who’s who of petrochemical corporations such as Halliburton, ExxonMobil, Shell Oil, Chevron, Marathon Petroleum, Kinder Morgan, and BP, as of 2008), coal and natural gas utility company Southern Company, and others.

One of those other commenters was the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance (DEPA), a lobbying and advocacy consortiumspearheaded by Harold Hamm, founder and CEO of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) giant Continental Resources, as well asenergy aide to the Donald Trump presidential campaign and potential future U.S. Secretary of Energy.

Continental Resources, as reported by DeSmog, will send some of its oil through Dakota Access and previously signed a shipping contract for the Keystone XL pipeline.

“DEPA applauds the Corps for its efforts to reissue the NWPs as they are an important regulatory vehicle to authorize activities that have minimal individual and cumulative adverse environmental effects under the Clean Water Act, Section 404 Program,” wrote DEPA. “These permits are critical to DEPA’s members in their day to day operations.”

Another commenter was Berkshire Hathaway Energy, a “most of the above” energy sources utility company (including coal and natural gas) owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway holding company. Buffett serves as a fundraiser for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

“Berkshire Hathaway Energy supports the Corps’ intention to issue NWPs,” wrote Berkshire Hathaway Energy. “The continued implementation of the NWPs is essential to the ongoing operation of Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s businesses — particularly in circumstances when timely service restoration is critical.”

Obama “Climate Test” Guidelines

On August 1, 2016, the day the commenting period closed for the future of NWP 12 and just days after the Army Corps issued a slew of NWP 12 determinations for Dakota Access, the Obama White House’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) issued a 34-page guidance memorandum, which could have potential implications for the environmental review of projects like Dakota Access.

That memo, while non-binding, calls for climate change considerations when executive branch agencies weigh what to do about infrastructure projects under the auspices of NEPA.

“Climate change is a fundamental environmental issue, and its effects fall squarely within NEPA’s purview,” wrote CEQ. “Climate change is a particularly complex challenge given its global nature and the inherent interrelationships among its sources, causation, mechanisms of action, and impacts. Analyzing a proposed action’s GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions and the effects of climate change relevant to a proposed action — particularly how climate change may change an action’s environmental effects — can provide useful information to decision makers and the public.”

NWP 12 does not receive mention in the memo. Neither does Dakota Access, Keystone XL, nor Flanagan South.

The non-binding guidance, which some have pointed to as an example of the Obama White House applying the “climate test” to the permitting of energy infrastructure projects, has been met with mixed reaction by the fossil fuel industry and its legal counsel.

The Center for Liquefied Natural Gas, a pro-fracked gas exports group created by API, denounced the CEQ memo. So too did climate change denier U.S. Sen. James Inhofe (R-OK), as well as U.S. Rep. Cynthia Lummis (R-WY).

Industry attorneys, however, do not view the guidance with the same level of trepidation, at least not across the board. On one hand, the firms Holland & Knight and K&L Gates — both of which work with industry clients ranging from Chevron and ExxonMobil to Chesapeake Energy and Kinder Morgan — have pointed to the risk of litigation that could arise as a result of the NEPA guidance. On the other end of the spectrum, the firms Squire Patton Boggs and Greenberg Traurig LLP do not appear to be quite as alarmed.

Greenberg Traurig — whose clients include Duke Energy, BP, Arch Coal, and others — jovially pointed out in a memo thatCEQ‘s NEPA guidance does not take lifecycle supply chain greenhouse gas emissions into its accounting. The firm also points out that, with agency deference reigning supreme throughout the memo, “agencies should exercise judgment when considering whether to apply this guidance to the extent practicable to an on-going NEPA process.”

Francesca Ciliberti-Ayres, one of the Greenberg Traurig memo co-authors, formerly served as legal counsel for pipeline giant El Paso Corporation.

Similar to Greenberg Traurig, the firm Patton Boggs attempted to quell its clients’ fears in its own memo written in response to the CEQ guidance memo. Patton Boggs’ clients also have included a number of oil and gas energy companies and lobbying groups, such as API, ConocoPhillips, Halliburton, Marathon Oil, and others.

“The new guidance has the potential to add substantial time and expense to all environmental reviews for companies and other entities currently undergoing the NEPA process — and for future actions,” Patton Boggs’ attorneys wrote.

“However, it will likely take some time for agencies to acclimate their review processes to the new requirements. Interested persons and companies would help themselves both by developing internal off the shelf information to accommodate the new review requirements and by working with federal agencies to develop efficient methodologies to expedite consideration on this issue, minimize any additional review time and add clarity to the process.”

J. Gordon Arbuckle, a Patton Boggs memo co-author, has previously worked on permitting projects such as the massive Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the Alaska Natural Gas Pipeline, the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, and others.

Using NWP 12 to permit major pipeline projects in a quiet and less transparent manner made its debut in the Obama White House. However, it remains unclear whether its use, or the somewhat contradictory NEPA guidelines from CEQ, will ultimately shape Obama’s climate legacy in the years to come.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 28, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Indirect Action

Featured image: Candelaria residents erect a fence around the Suyul Lagoon to help protect it from intruders. (Waging Nonviolence/Sandra Cuffe)

By Sandra Cuffe / Waging Nonviolence

The reeds and grasses are as tall as Sebastián Pérez Méndez, if not taller. The vegetation is so thick it’s hard to see the water in the Suyul Lagoon that he and other local Maya Tzotzil residents are working hard to protect. Pérez Méndez crosses the road to point out where aquatic plants serve as a natural filter for the water as it flows out the lagoon, located in the highlands of Chiapas, in southern Mexico.

“The water is under threat,” he said. Pérez Méndez is the top authority of the Candelaria ejido, a tract of communally-held land in the municipality of San Cristóbal de las Casas. “We’re not going to allow it.”

Communities in Chiapas are organizing to protect the Suyul Lagoon and communal lands from a planned multi-lane highway between the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque, where Mayan ruins are a popular tourist destination. Candelaria residents continue to take action locally to protect the lagoon. They also traveled from community to community along the proposed highway route, forming a united movement opposing the project.

It all started back in 2014 when government officials showed up in Candelaria looking for ejido authorities, including Pérez Méndez’ predecessor. It was the first residents had heard about plans for the highway. The indigenous inhabitants had not been consulted and were not shown detailed plans.

“They realized that [the government officials] were only seeking signatures,” Pérez Méndez said.

No one person or group is authorized to make a decision that would affect ejido lands, however, and there are strict conditions in place to ensure elected ejido leaders are accountable to members, he explained. An extraordinary assembly was held to discuss the highway project.

The Candelaria ejido was established in 1935, a year after a new agrarian law enacted during the Lázaro Cárdenas administration led to widespread land reform throughout Mexico. More than 2,000 people live in the 1,600-hectare ejido, and more than 800 of them are ejidatarios — legally recognized communal land holders whose rights have been passed down for generations. Only ejidatarios as a whole have the power to make decisions on issues like the highway project.

Candelaria residents paint over graffiti to fix up a roadside sign proclaiming their opposition to the highway project. (Waging Nonviolence/Sandra Cuffe)

“The ejido said no,” said Guadalupe Moshan, who works for the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, or FrayBa, supporting Candelaria and other communities in Chiapas. “They didn’t sign.”

Candelaria leaders sought assistance from FrayBa in 2014, after they were approached by government officials and pressured to sign a document indicating their consent to the highway project that would involve a 60-meter-wide easement through communally-held lands. Officials told community members that the highway was already approved and that they would be well compensated, but that there would consequences if they refused to sign, Moshan said.

“They told them they would suspend government programs and services,” she explained. In the days following the extraordinary ejido assembly rejecting the project, there was unusual activity in the area, according to Moshan. Helicopters flew over theejido, unknown individuals entered at night, and trees were marked, she said.

Protecting the Suyul Lagoon remains at the heart of Candelaria’s opposition to the planned highway. The lagoon provides potable water not only for Candelaria, but also for several nearby communities, said ejido council secretary Juan Octavio Gómez. Aside from the highway itself, project plans eventually shown to the community leaders include a proposed eco-tourism complex right next to the lagoon. That isn’t in the communities’ interest, Gómez explained.

“Water is life. We can’t live without it,” he said. “Without this lagoon, we don’t have another option for water.”

Fed by a natural spring, the Suyul Lagoon never runs dry. Local residents are careful to protect the water and lands in the ejido, where the majority of residents live from subsistence agriculture, sheep rearing and carpentry. They engage in community reforestation, but have plans to plant more trees, Gómez said.

The Suyul Lagoon is also sacred to local Maya Tzotzil. Ceremonies held every three years in its honor involve rituals, offerings, music and dance.

“It is said that it’s the navel of Mother Earth,” Pérez Méndez said.

Candelaria residents didn’t sit back and relax after rejecting the highway project in their extraordinary assembly. They have been organizing ever since. The Suyul Lagoon lies just outside the Candelaria ejido, but it belongs to ejidatarios by way of an agreement with the supportive land owner. Aside from the highway project and potential eco-tourism complex, the lagoon has caught the attention of companies, whose representatives have turned up in the area expressing interest in establishing a bottling plant.

It’s cold in February up in the highlands, but community members have been out all day, erecting a fence around the Suyul Lagoon to protect it from intruders. White fence posts are visible under the treeline across the sea of reeds. Like so many other local initiatives, fence materials are collectively financed by the ejido and the labor is all voluntary, communal work.

While residents continue stringing barbed wire from post to post, others take paintbrushes to one of their roadside signs. Locals have erected large signs next to roads in and around their ejido, announcing their opposition to the tourist highway.

A sign along the road leading to Candelaria informs passers-by of opposition to the planned super-highway. (Waging Nonviolence/Sandra Cuffe)

“We’re also already organized with the other communities,” Pérez Méndez said. “All the communities reject the super-highway.”

After they were approached by government officials, Candelaria ejido residents traveled from community to community along the entire planned highway route. Some communities hadn’t heard of the project at all, while others said they were pressured into signing documents indicating their consent, Pérez Méndez said. As a result of Candelaria’s visits, community organizing along the highway route led to the formation of a united front of opposition, the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory.

Candelaria also recently got together with other indigenous communities in the highlands to issue a joint statement rejecting the tourist super-highway and a host of other government and corporate projects and policies.

“Our ancestors, our grandfathers and our grandmothers have always taken care of these blessed lands, and now it’s our turn to [not only take] care of the lands, but also to defend them,” reads the February 10 communiqué.

“The neoliberal capitalist system, in its ambition to exploit natural assets, invades our lands,” the statement continues. “The government and transnational companies are violently imposing their mega-projects.”

Back along the edge of the Suyul Lagoon, Candelaria residents continue to string barbed wire from post to post. They’ve been at it for a while now, according to Pérez Méndez, but they’ve now stepped up their efforts and hope to finish the fence by the end of the month.

Pérez Méndez surveys the progress, protected from the unrelenting sun and icy wind by his hat and white sheep’s wool tunic. He becomes pensive when asked if he thinks communities will be able to defeat the highway project.

“Yes,” the ejido leader said, after giving it some thought. “We can stop it.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2016 | Building Alternatives, Repression at Home, Toxification

Originally published in the September/October 2012 issue of Orion. Now republished for the first time online.

In an era of government-sanctioned polluters, communities must defend themselves

Several years ago I spoke at a benefit for an organization working to prevent a toxic waste site from being built in their community. Yet another toxic waste site, the organizers clarified, since there already was one. It should surprise no one that their community was primarily poor, primarily people of color, and that the toxic waste was being brought in so that distant corporations could reap bigger profits.

The organization had been fighting the dump for years, on every level, from filing lawsuits to holding protests to physically blockading the dump site. Several people at the benefit commented on the bizarre role that the police played in all of this. Many of the cops lived in the community and were themselves opposed to the toxic dump. But when they put on their uniforms and headed off to work, their jobs included arresting their neighbors who were trying to protect the neighborhoods where their own children lived and played.

We’ve all heard of dues-paying union cops busting the heads of strikers because their capitalist bosses tell them to. And of cops arresting protesters trying to prevent the cops’ own water supplies from being toxified (while of course not arresting the capitalists who are toxifying the water supplies). And I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s had fantasies that at the next economic summit or World Bank meeting, members of the police will experience an epiphany of conscience and realize they share class interests not with those they’re protecting but rather with those at whom they’re pointing their guns. And in this fantasy the police then turn as one to join the protesters and face their real enemy.

At the benefit we shared all sorts of fantasies like these, and we all laughed at how unrealistic they were. There have been instances in which the police have worked with the people to stop government or corporate atrocities, but they’re too rare.

And then we shared some other fantasies, which all consisted in one way or another of police choosing to enforce laws that are already on the books, laws that protect our communities. Laws like the Clean Air Act, or the Clean Water Act, or for that matter laws against rape. We fantasized about what it might be like to have police enforce carcinogen-free zones, or dam-free zones, or WalMart-free zones, or rape-free zones.

And then again we laughed, since we knew that these fantasies, too, were unrealistic. It’s not the job of the police to protect you from living in a toxified landscape, even if that landscape is being toxified illegally.

In fact — and this may or may not be surprising to you — the police are under no legal obligation to protect you at all. This fact has been upheld in courts again and again. In one case, two women in Washington DC were upstairs in their townhouse when they heard their roommate being assaulted downstairs. Several times they phoned 911 and each time were told police were on their way. A half hour later their roommate stopped screaming, and, assuming the police had arrived, they went downstairs. But the police hadn’t arrived, and so for the next fourteen hours all three women were repeatedly beaten and raped. The women sued the District of Columbia and the police for failing to protect them, but the district’s highest court ruled against them, saying that it is “a fundamental principle of American law that a government and its agents are under no general duty to provide public services, such as police protection, to any individual citizen.”

So there you have it. Time and again, many similar cases have yielded the same case law, at local, state, and federal levels. But a lot of rape victims already know this; only 6 percent of rapists spend even one night in jail. And the people in that community who were having a toxic waste dump crammed down their throats with the professional support of the police also know this. As do the human and nonhuman people of the Gulf of Mexico, who are still being killed or injured by the Deepwater catastrophe — and who will experience far more of the same, since the U.S. government is supporting more deepwater drilling. As one technical advisor to the oil and gas industry put it, “We are seeing deep-water drilling coming back with a vengeance in the Gulf.”

So here’s the question: if the police are not legally obligated to protect us and our communities — or if the police are failing to do so, or if it is not even their job to do so — then if we and our communities are to be protected, who, precisely is going to do it? To whom does that responsibility fall? I think we all know the answer to that one.

A lot of people seem to love to talk about the virtues of self- and community-reliance, but where are they when we need to defend our communities?

Fortunately there are many examples of communities rising up to defend themselves from wrongdoing from which we can and should learn. Pre-Revolutionary — or you could say revolutionary yet pre-1776 — American patriots, sick and tired of rule by a distant elite (sound familiar?), increasingly refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Crown Courts and other institutions, and put in place their own systems of justice. The same has been true for the Irish in their struggle for independence. The same was true of the Spanish anarchists: part of their project included pushing fascists out of their communities and another part consisted of putting in place their own neighborhood systems of justice and community protection.

I think often of something a former head of “security” for South Africa under apartheid said: that what they’d been most afraid of from the revolutionary group the African National Congress had never been the ANC’s sabotage or even their violence, but rather that the ANC might be able to convince the mass of South Africans to not believe in law and order as such, which in this case meant the law and order imposed by the apartheid regime, which in this case meant the legitimacy of the exploitative apartheid government, which in this case meant that their greatest fear was that the ANC would convince the majority of people to withdraw their consent to be governed by an elite that does not have their best interests at heart.

In our case, we don’t need an ANC to convince us of the illegitimacy of many of the actions of those in power. Those in power are doing a great job of convincing us by their own actions. If the Gulf catastrophe (and the continuation of deepwater drilling) doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If fracking and the poisoning of our groundwater doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the governmental response to global warming — ranging from vindictiveness against climate scientists to denial to measures that at very best are completely incommensurate with the threat — doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the total toxification of the environment, with its inevitable health consequences for both humans and nonhumans, doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. I routinely ask the people at my talks whether they have had someone they love die of cancer, and at least 75 percent almost always say yes.

And when I ask people at my talks if they believe that state and federal governments take better care of corporations or of human beings, no one — and I mean no one — ever says human beings. Reframing the question to consider whether governments take better care of corporations or the planet — our only home — yields the same result.

If police are the servants of governments, and if governments protect corporations better than they do human beings (and far better than they do the planet), then clearly it falls to us to protect our communities and the landbases on which we in our communities personally and collectively depend. What would it look like if we created our own community groups and systems of justice to stop the murder of our landbases and the total toxification of our environment? It would look a little bit like precisely the sort of revolution we need if we are to survive. It would look like our only hope.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 11, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

By Katie Fite / WildLands Defense

This article first appeared on Counterpunch

Featured Image: Virgin River with banks trampled like a feedlot by Cliven Bundy cattle. May 2015.

In Oregon, an armed occupation of Malheur Wildlife Refuge headquarters is being led by self-proclaimed “patriots” from Nevada. They are defending a public lands ranching family’s “right” to set fires and break the law.

In Nevada, Cliven Bundy owes more than a million dollars in grazing fees. An armed confrontation broke out when BLM began to impound his trespass livestock. The government backed down. For almost two years, no action has been taken while the Bundy camp becomes ever more brazen. This past summer, when Cliven Bundy went to the Nevada legislature to support a bill to turn over federal authority of public land to the state, he was treated to a barbecue by Nevada Congressman Mark Amodei.

Cliven Bundy is not the only Nevada Rancher being given proprietary treatment by Nevada federal land managers. Settlement deals and BLM coddling reward hostile ranchers at the expense of the public’s land.

Argenta Allotment Settlement

There has been prolonged, severe drought in Nevada. In 2014, defiant public lands ranchers resisted Battle Mountain BLM drought closures and cattle cuts in the Argenta allotment. They were emboldened by the Bundy incident. The ranchers set up a “Grass Camp,” aided by instigator Grant Gerber, across from the BLM office. They have waged an intimidation campaign against agency staff. They whined incessantly to cattle friendly Nevada politicians Amodei and Senator Heller. The Elko paper did not really report, but instead was a worshipful cheerleader against the BLM. The ranchers denied there even was a drought. At the very same time, they received lavish federal drought disaster relief payments.

The cattle damage became so severe that by late summer the local BLM finally closed the sensitive sage-grouse habitats in mountain pastures of the Shoshone Range to grazing. The ranchers and states rights politician John Carpenter appealed the protective closure. In spring 2015, an Interior Department Office of Hearings and Appeals administrative law judge finished review of a mountain of documents, and ruled in favor of the closure.

But within weeks, BLM folded. All of Argenta was again flung open to grazing. Leadership under Nevada BLM Director John Ruhs had forced a settlement deal indulging the ranchers’ every whim. Ruhs, bonded at the hip with the Cattlemen, had been “Acting” Director, and then officially became Nevada Director.

Nevada BLM Director John Ruhs

The deal was greased through by the “National Riparian Team,” composed of livestock industry sycophants from within BLM and the Forest Service, and outside cattle consultants.

The Team, while claiming to be a neutral party, immediately took the ranchers’ side – with Team members railing against perceived interference by the local BLM staff that had sought to control cattle damage to the public lands. So it’s no surprise the settlement flung open sensitive closed sage-grouse habitats to full bore grazing. Herds of several hundred cows were allowed to trample and devour “forage” across the drought-stricken public land in 2015.

The settlement put the Team in charge of a Coordinated Monitoring Group “(CMG”) dominated by ranchers and a token enviro group to take control of monitoring, to direct management actions, and run interference with the local BLM so the Argenta ranchers would not be accountable for grazing damage or trespass.

The cabal bars the public and press from observing their monitoring of grazing damage, and from their closed door discussions that dictate management. The group tells BLM what to do to keep the ranchers happy.

The result has been grazing chaos, and wanton damage of lands and waters. Wildlands Defense (WLD) and colleagues visited Argenta to observe and document conditions. Cattle were scattered all over the allotment, and riparian areas ravaged. When we asked BLM where cows were supposed to be present, the local BLM managers did not even know. All was in the hands of the Team and CMG.

Cattle trampling dries out and destroys sage-grouse brood habitats.

Scads of new cattle projects are also laid out in the settlement. A July Team memo plans new barbed wire fencing and water projects incrementally sprawled across Argenta. The Team embraces injurious grazing practices – severe cattle trampling soil disturbance and high use of native grasses. Why the projects? So ranchers don’t have to work to control their cows. This frontloads Argenta with band-aid fences around prominent degraded areas (and long term monitoring sites) close to roads, prior to any thorough Land Health assessment. There never has been any grazing study since the 1976 passage of FLPMA. The ranchers can then claim conditions within the little fenced areas are “improving,” and insulate against cattle cuts in an assessment.

Monitoring cage illustrating how severe cattle use is. Our site visits found such cages destroyed in some areas since the CMG group took over.

This fall, BLM obediently issued a Decision giving the ranchers six new permanent fences, plus “temporary” water troughs and a pipeline. WLD and Wild Horse Education appealed the first battery of projects, which are terrible for wildlife. Sage-grouse and other wildlife are killed by flying into or becoming entangled with wire. The projects also shift intensive impacts onto other areas. We also challenged the Ruhs Settlement – which has altered grazing, established the exclusive closed meetings, and directed the projects. BLM claims we can’t appeal the Settlement.

Now over the holidays, BLM proposed more projects. The ranchers, through the cover of the Team and CMG, are essentially now running the public lands.

North Buffalo Settlement

Days after BLM caved in Argenta, one of the very same permittees, Filippini Ranch, rewarded BLM appeasement efforts by unleashing their cattle on the nearby North Buffalo allotment. North Buffalo, like Argenta, was closed for drought protection. It is home to a very small struggling population of sage-grouse, whose habitat is also being consumed by foreign gold mines.

BLM could not help but notice the cows turned out illegally, since the ranch owner told about the trespass to the Elko newspaper, flaunting his power. Leadership under Ruhs promptly rewarded this trespass with another Settlement deal. Just as in Argenta, a North Buffalo Settlement flung open the closed lands. BLM charged Filippini around $100 for willful trespass – a small price for being allowed access to tens of thousands of dollars worth of public lands “forage” for which the permittees pay a pittance.

Uncapped abandoned test well site in now Wilderness lands where rancher claimed water rights.

DeLong and Humboldt County Settlement

There is yet another Settlement deal gift to a powerful rancher, this time in Winnemucca BLM lands. The powerful Delong ranching operation and Humboldt County had sued BLM over a raft of access issues primarily involving cattle water projects, many in Wilderness areas with no access roads. The projects had not been recognized by BLM when compiling project lists following the passage of the Black Rock Wilderness legislation in 2000. The lawsuit involved arcane regulations originating in the 1800s and early 1900s. BLM issued a scoping letter this fall proposing to maintain, reconstruct and access 15 cattle projects, access private inholdings, and maintain irrigation ditches – mainly in the North Jackson, South Jackson and Black Rock Wilderness in the South Jackson allotment.

BLM did not tell the public in its confusing letter that the proposal was based on yet another recent Settlement deal. We only learned of this when querying the BLM staff.

BLM field trip in area where rancher is being allowed access for cattle water project.

Hold Your Wild Horses

BLM leadership has knowingly looked away from a series of purposeful and blatant violations of the Code of Federal Regulations by a rancher (Borba) in the Fish Creek wild horse Herd Management Area in Battle Mountain country.

The rancher was found to be in “willful trespass,” grazing his livestock outside the boundaries of his legally authorized use for eight months. Under pressure from politicians Heller and Amodei, the BLM reduced the trespass and lowered fees.

The rancher and Eureka County also became upset over a local BLM decision to manage wild horses to incrementally reduce the population. The BLM removed over 200 wild horses, and then planned to use the PZP fertility control drug, and release horses given fertility control back to the HMA. In a stand-off reminiscent of an old western movie, the county and rancher showed up onsite and demanded the BLM not release the horses.

The BLM caved, and the horses were hauled away. After a lengthy legal battle the horses were returned to the range months later.

The disgruntled rancher began a social media campaign to rile the public against “government abuse.” Claims were made that he was never in trespass. He videotaped himself repeatedly breaking the law, and put it on social media. The penalties for the acts committed clearly state that the permittee will face fines, possible jail time and “shall” lose the right to graze on public lands.

Ruhs met with the rancher, County and local BLM Manager Furtado at Fish Creek, and sided with cattleman over his own staff. The BLM state office has now put the brakes on the fertility control program for the Fish Creek wild horses. This winter, the permittee is grazing livestock as if nothing happened.

Is It Continued Bungling, Political Interference or Tacit Support?

Badly bungling the Bundy situation and failing to act for almost two years now, the BLM opened the floodgates of rancher defiance and Sagebrush Rebel hell. The Ruhs Settlement deals reward powerful public lands ranchers who hate the agency and the very concept of public good and public lands. Allowing violations of federal law to go unaddressed has created an environment where any concept of law appears meaningless. The Settlements in Argenta, North Buffalo, Jackson Mountain/DeLong, coupled with BLM leadership ignoring blatant Fish Creek rancher law-breaking, embolden the very parties who want to see the public lands become unmanageable by the federal government.

Safety of BLM employees on the ground has been jeopardized. The ranchers want removed anyone who might attempt to protect the environment. Their intimidation campaign is demanding Battle Mountain District Manager Doug Furtado be fired. The local office has been rendered powerless.

Appointment of Ruhs as Nevada Director, sweetheart settlement deals and toleration of overt law-breaking all have taken place under national BLM Director Neil Kornze, a native of Elko, Nevada and son of a mining engineer.

Is this ineptitude on the part of BLM leadership, political interference, or something else? Kornze increasingly appears to be either the most bungling BLM Director ever – or a fellow traveler with the Nevada public Land Grab crowd. While we continue to see PR photos of the BLM Director on outdoor excursions, important areas of the American West are being handed over to the welfare ranchers through a policy of capitulation and appeasement – resulting in a de facto loss of federal control and stealth Land Grab.