by DGR News Service | Nov 13, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

This article is based on communication from a comrade in the Negros province of the Philippines. There is ongoing destruction of the natural world in this area due to road construction, a planned airport, and clearing of the rainforest. The people on the front lines, being most affected, are calling for international solidarity and support.

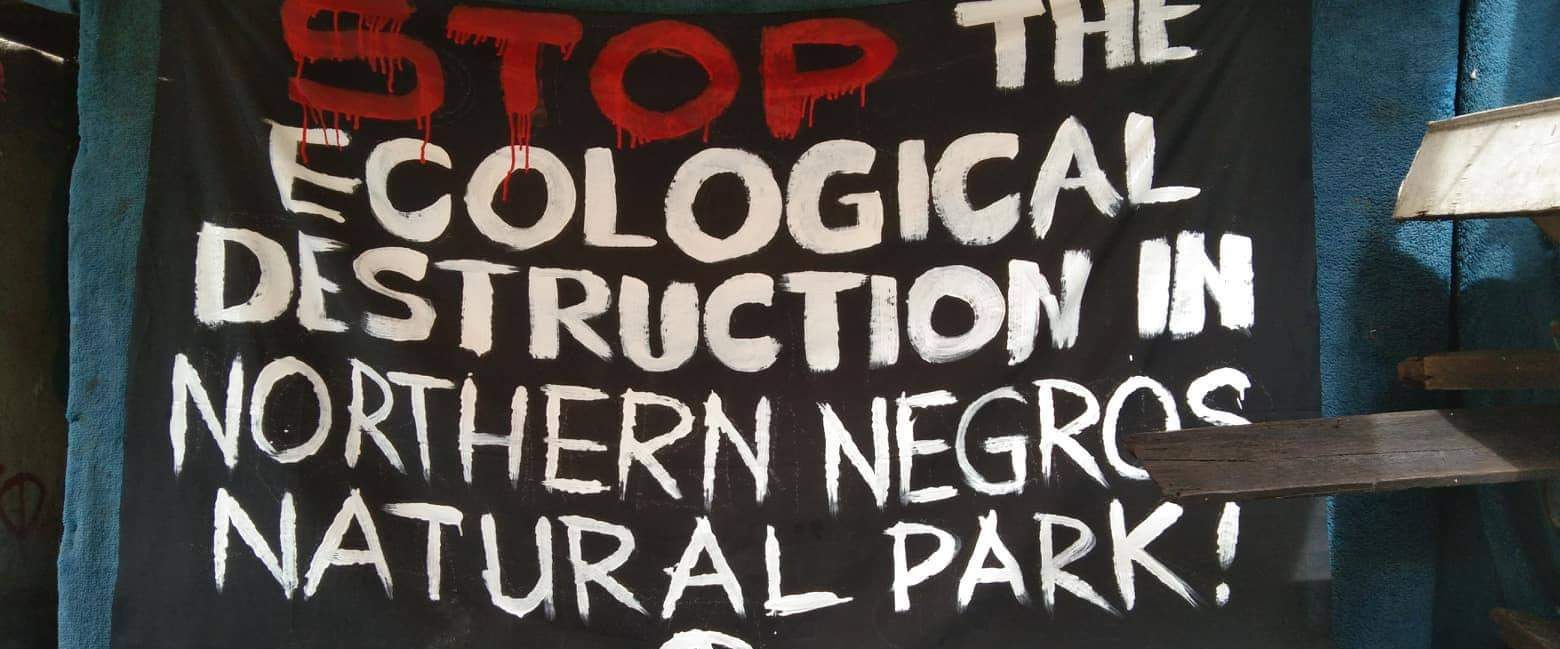

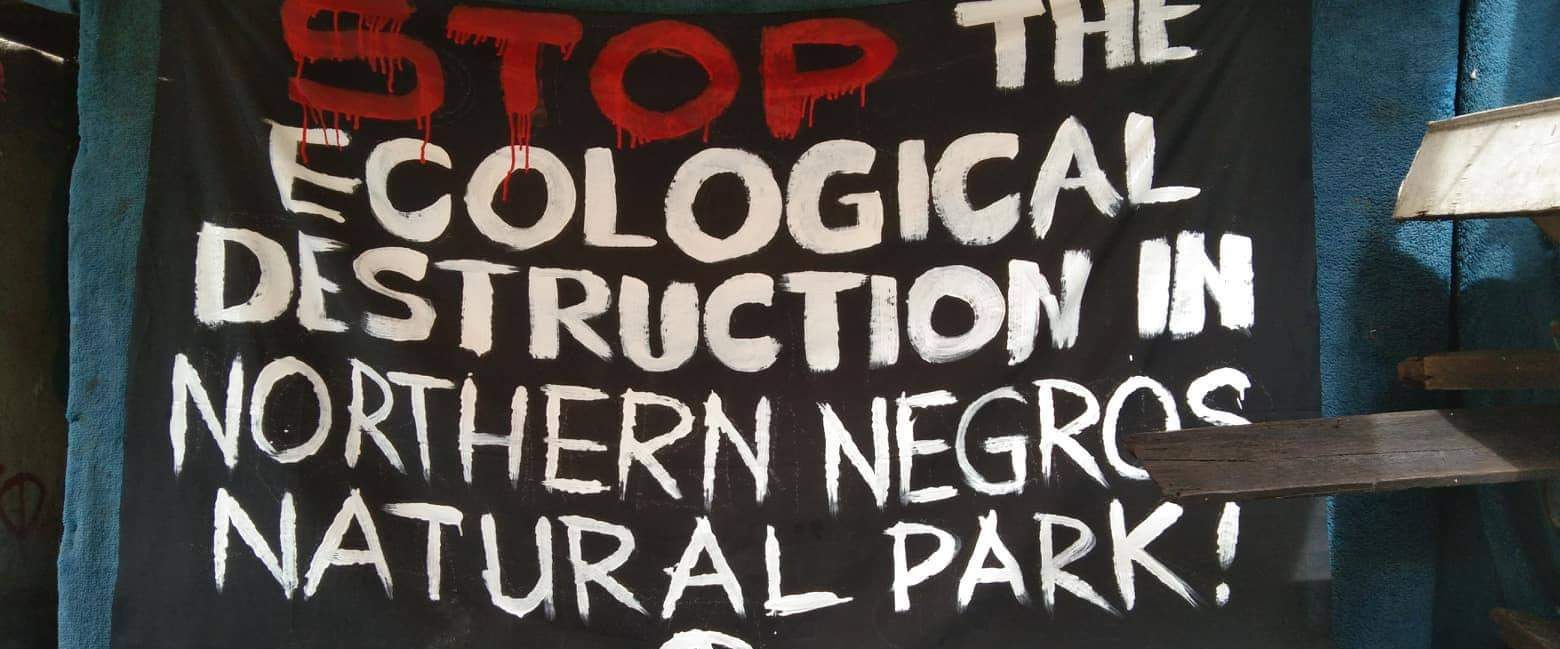

On October the 18th this year, the first direct action regarding the Northern Negros National Park was taken by a group of concerned people. Food Not Bombs Bacolod Volunteers and concerned citizens have started a campaign to raise awareness about the ongoing destruction of the rainforest in the Negros area of the Philippines. The group has begun disseminating information to ensure other know about the ongoing harm being caused and to stand firmly IN SOLIDARITY WITH THE FOREST.

The group, focused their work in the city of Bacolod distributing printed placards, information flyers & leaflets and have been clear they are in direct opposition to any act of destruction. Food Not Bombs Bacolod condemns these injustices and the actions of the Local Government of Negros Island which sanctions the destruction of the remaining rainforest of the island.

About Northern Negros National Park

The Northern Negros Natural Park is a protected area of the Philippines located in the northern mountainous forest region of the island of Negros in the Visayas. It is spread over five municipalities and six cities in the province of Negros Occidental and is the province’s largest watershed and water source for seventeen municipalities and cities including the Bacolod metropolitan area.

The park belongs to the Negros–Panay Biogeographic Region. It is one of two remaining lowland forests on Negros island, the other being in the Dumaguete watershed area in Mount Talinis on the southern end of the island in Negros Oriental.

The park is a habitat to important fauna including the Visayan spotted deer, Visayan warty pig, Philippine naked-backed fruit bat, and the endangered Negros shrew.

Number of endemic and threatened species of birds have been documented in the park, which includes the Visayan hornbill, Negros bleeding-heart, white-winged cuckooshrike, flame-templed babbler, white-throated jungle flycatcher, Visayan flowerpecker and green-faced parrotfinch.

Flora documented within the park include hardwood tree species (Dipterocarps), as well as palms, orchids, herbs and trees with medicinal value. Very rare is the local species of the cycas tree (locally called pitogo), probably a Cycas vespertilio, considered living fossil from the times of dinosaurs. Another prehistoric flora is present in the park like the tree ferns and the also protected Agathis philippinensis, (locally known as almaciga).

While We Were Distracted

As we know during 2020 most nations have been preoccupied trying to survive lockdown. During this time the local government of Negros Island, Protection And Management Board, Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) failed in its responsibilities to protect the remaining watershed and rainforest. Road construction on the island started in the midst of Global Pandemic.

Instead the DENR legitimized the road construction on the Island and in doing so has increased the likelihood of communities on the island being destroyed in the medium to long term. The DENR, along with the Department of Public Works and the Department of Highways have acted in a way that swept aside the needs of local communities, that ignored the rights of the natural world and in doing so have colluded to strengthen their power. In short they have become the mechanism and tool of destruction for the island.

The Aerotroplis Project

The plans to build a new International Airport in Manila has also hit the radar of environmental activists. The people and environmental groups in Bulakan and Bulacan have shared concerns about the devastation this will cause to the natural world, to wildlife (including fish) populations, bird populations, air pollution, and airplanes flying in the sky. As always the focus is on economic benefits rather than the health of planet or people. There has been little or no analysis of the environmental impact.

Leon Dulce, national coordinator of Kalikasan-People’s Network for the Environment (Kalikasan-PNE), told the BusinessMirror that the presence of the bird populations are bioindicators of good ecological health. He stated “This is of crucial importance in these times when there are multiple epidemiological risks from pandemics, socioeconomic loss, and climate emergency all emerging from the disrupted environment. Massive land-reclamation activities in Manila Bay threatens the last remaining wetlands where migratory birds roost. The Bulacan Aerotropolis is one of the biggest threats that will destroy 2,500 hectares of mangroves and fisheries. It is outrageous that transportation mega infrastructure is being touted for economic recovery when global transportation is expected to remain disrupted until 2021.”

Critical Mass Ride

Following the actions from Food Not Bombs Bacolad, on November 8th Local Autonomous Networks held a discussion to consider the ongoing problem. They agreed to organize a coordinated Critical Mass Ride. The ride involved concerned people in the Archipelago from the different islands of the Philippines gathering to travel around the main city to raise awareness.

Following the actions from Food Not Bombs Bacolad, on November 8th Local Autonomous Networks held a discussion to consider the ongoing problem. They agreed to organize a coordinated Critical Mass Ride. The ride involved concerned people in the Archipelago from the different islands of the Philippines gathering to travel around the main city to raise awareness.

Food Not Bombs and Local Autonomous Networks have issued a call to action to support them in opposing the road construction and the subsequent destruction of the Rainforest that will kill the livelihood of hundreds of families.

The call to action in the Archipelago is just a start. They have been clear they will not stop nor be silenced until the destruction planned has been stopped. They are calling for International Solidarity to all readers.

Join The Resistance. Join The Fight!

Save the Remaining Forest & Watershed of Northern Negros Natural Park, Stop the Patag-Silay-Calatrava-Cadiz Road Construction. STOP the Bulacan Aerotropolis Project.

by DGR News Service | Oct 21, 2020 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

Communal house of uncontacted Indians inside the Uru Eu Wau Wau territory, photographed in 2005. © Rogério Vargas Motta/IBAMA (Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources).

Survival International / October 14, 2020

The survival of several uncontacted tribes is now at risk after fires were set inside their territories. Activists have described this year’s Amazon fires, and President Bolsonaro’s war on indigenous peoples, as “the gravest threat to the survival of uncontacted tribes for a generation.”

Four tribal territories face an especially serious crisis:

– The famed Papaya Forest on Bananal Island, the world’s largest fluvial island. It’s inhabited by uncontacted Ãwa people. Eighty per cent of the forest burned in fires last year – fires have been seen this year in one of the last areas of intact forest. More than 100,000 head of cattle now graze on the island.

– The Ituna Itatá (“Smell of Fire”) indigenous territory in Pará state, inhabited exclusively by uncontacted Indians. This reserve was the most heavily deforested indigenous territory in 2019, as land grabbers and cattle ranchers invaded. In the first four months of 2020, another 1,319 hectares of forest were destroyed, an increase of almost 60% compared to the same period last year.

– The Arariboia territory in the eastern Amazon state of Maranhão: uncontacted Awá inhabit this territory, which has already been extensively invaded. Amazon Guardians of the neighboring Guajajara tribe are warning daily that illegal loggers are destroying the forest at alarming rates. (The Ãwa people of Bananal Island and the Awá tribe of Maranhão state are distinct peoples).

– The Uru Eu Wau Wau territory. Uncontacted Indians inside this territory shot and killed famed Amazon expert Rieli Franciscato last month – campaigners fear the group is being forced out of the forest by the invasions.

Many of the fires are being started to clear the rainforest for logging and ranching, and millions of tons of soya, beef, timber and other products are imported into Europe and the US each year.

APIB (the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil) has launched a campaign to highlight the links between Bolsonaro, his agribusiness backers, and the genocidal violence being committed against indigenous peoples across the country. They are asking people and companies around the world to stop buying products that are fuelling the destruction of their territories.

Survival has launched a global action calling on supermarkets in Europe and the US to stop buying Brazilian agribusiness products until indigenous rights are upheld.

Ângela Kaxuyana, spokesperson from COIAB, the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon, said: “Land grabbing, deforestation and arson directly threaten the lives of our uncontacted relatives. The destruction of the territories that are their only sources of life, from where they obtain their food (fauna, flora and water), could end in their extermination.” “A grilagem de terra, o desmatamento e os incêndios criminosos ameaçam diretamente a vida dos nossos parentes em isolamento voluntário. A destruição dos territórios que são suas únicas fontes de vida, de onde garantem sua alimentação (fauna, flora e água), podem levá-los ao extermínio”.

Tainaky Tenetehar, one of the Guajajara Guardians who protect the Arariboia reserve for the Guajajara people and their uncontacted neighbors, said today: “We fight to protect this forest, and many of us have been killed doing so, but the invaders keep coming. They have damaged the forest so much in recent years that their fires are now much bigger, and more serious, than before, as the forest is so dry and vulnerable. The loggers must be evicted – only then can the uncontacted Awá survive and thrive.”

Survival’s Senior Researcher Sarah Shenker said: “In many parts of Brazil, uncontacted tribes’ territories are the last significant areas of rainforest left. Now they are being targeted by land grabbers, loggers and ranchers emboldened by Bolsonaro’s open support for them. Consumers in the US and Europe must understand that there’s a direct connection between the food on their supermarket shelves and this genocidal destruction – and act accordingly. Uncontacted tribes are the most vulnerable peoples on the planet, and at the same time nature’s best guardians, by far. We cannot let their land go up in flames.”

by DGR News Service | Oct 18, 2020 | ANALYSIS, The Problem: Civilization

We Indigenous people are fighting to save the Amazon, but the whole planet is in trouble because you do not respect it

by Nemonte Nenquimo / Originally published in The Guardian, Oct. 12 2020

Featured image: Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo shows evidence of crude oil contamination in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. Photograph: Mitch Anderson / Amazon Frontlines

Dear presidents of the nine Amazonian countries and to all world leaders that share responsibility for the plundering of our rainforest,

My name is Nemonte Nenquimo. I am a Waorani woman, a mother, and a leader of my people. The Amazon rainforest is my home. I am writing you this letter because the fires are raging still. Because the corporations are spilling oil in our rivers. Because the miners are stealing gold (as they have been for 500 years), and leaving behind open pits and toxins. Because the land grabbers are cutting down primary forest so that the cattle can graze, plantations can be grown and the white man can eat. Because our elders are dying from coronavirus, while you are planning your next moves to cut up our lands to stimulate an economy that has never benefited us. Because, as Indigenous peoples, we are fighting to protect what we love – our way of life, our rivers, the animals, our forests, life on Earth – and it’s time that you listened to us.

In each of our many hundreds of different languages across the Amazon, we have a word for you – the outsider, the stranger. In my language, WaoTededo, that word is “cowori”. And it doesn’t need to be a bad word. But you have made it so. For us, the word has come to mean (and in a terrible way, your society has come to represent): the white man that knows too little for the power that he wields, and the damage that he causes.

You are probably not used to an Indigenous woman calling you ignorant and, less so, on a platform such as this. But for Indigenous peoples it is clear: the less you know about something, the less value it has to you, and the easier it is to destroy. And by easy, I mean: guiltlessly, remorselessly, foolishly, even righteously. And this is exactly what you are doing to us as Indigenous peoples, to our rainforest territories, and ultimately to our planet’s climate.

It took us thousands of years to get to know the Amazon rainforest. To understand her ways, her secrets, to learn how to survive and thrive with her. And for my people, the Waorani, we have only known you for 70 years (we were “contacted” in the 1950s by American evangelical missionaries), but we are fast learners, and you are not as complex as the rainforest.

When you say that the oil companies have marvellous new technologies that can sip the oil from beneath our lands like hummingbirds sip nectar from a flower, we know that you are lying because we live downriver from the spills. When you say that the Amazon is not burning, we do not need satellite images to prove you wrong; we are choking on the smoke of the fruit orchards that our ancestors planted centuries ago.

When you say that you are urgently looking for climate solutions, yet continue to build a world economy based on extraction and pollution, we know you are lying because we are the closest to the land, and the first to hear her cries.

I never had the chance to go to university, and become a doctor, or a lawyer, a politician, or a scientist. My elders are my teachers. The forest is my teacher. And I have learned enough (and I speak shoulder to shoulder with my Indigenous brothers and sisters across the world) to know that you have lost your way, and that you are in trouble (though you don’t fully understand it yet) and that your trouble is a threat to every form of life on Earth.

You forced your civilisation upon us and now look where we are: global pandemic, climate crisis, species extinction and, driving it all, widespread spiritual poverty. In all these years of taking, taking, taking from our lands, you have not had the courage, or the curiosity, or the respect to get to know us. To understand how we see, and think, and feel, and what we know about life on this Earth.

I won’t be able to teach you in this letter, either. But what I can say is that it has to do with thousands and thousands of years of love for this forest, for this place. Love in the deepest sense, as reverence. This forest has taught us how to walk lightly, and because we have listened, learned and defended her, she has given us everything: water, clean air, nourishment, shelter, medicines, happiness, meaning. And you are taking all this away, not just from us, but from everyone on the planet, and from future generations.

It is the early morning in the Amazon, just before first light: a time that is meant for us to share our dreams, our most potent thoughts. And so I say to all of you: the Earth does not expect you to save her, she expects you to respect her. And we, as Indigenous peoples, expect the same.

Nemonte Nenquimo is cofounder of the Indigenous-led nonprofit organisation Ceibo Alliance, the first female president of the Waorani organisation of Pastaza province and one of Time’s 100 most influential people in the world.

by DGR News Service | Sep 4, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

This piece was originally published in Earth Island Journal.

Zambia and Zimbabwe plan to move ahead with the $4 billion Batoka Gorge Dam that would displace villagers, wildlife, and a vibrant rafting industry along the Zambezi River.

by Rebecca Wilbear/Earth Island Journal

More than 50 men traverse the steep, rocky gorge. They balance as many as three kayaks on their back each, along with other equipment for rafting companies offering trips in the Batoka Gorge. Sweat glistens on their skin; they earn a dollar for each kayak. These porters come from the Indigenous Tokaleya villages situated along the edge of the gorge, on either side of the Zambia-Zimbabwe border. For the Tokaleya, the Zambezi River is an essential and sacred deity. It’s also a source of income. Tens of thousands of tourists raft the Zambezi’s rapids each year, drawn to the region’s rich ecosystem. Alongside the Tokeleya, birds, fish, and other wildlife make their home in the gorge.

Yet the section of the river that runs through Batoka Gorge is threatened. In June 2019, the General Electric Company of the United States and the Power Construction Corporation of China signed a deal with the Zambian and Zimbabwean governments to build and finance the Batoka Gorge Dam. The danger from a massive hydroelectric project, which was first proposed nearly 70 years ago, has become urgent.

Africa’s fourth largest river, the Zambezi flows through six countries. The Batoka Gorge section begins at the bottom of Victoria Falls, the largest waterfall in the world, also called Mosi-oa-Tunya, or “The Smoke That Thunders.” A few miles from Livingstone, Zambia, massive roaring waters spill from the sky and turn clear green as the river races through steep, dark canyon walls down the 50-mile gorge. The river then meanders for another 200 miles until it reaches Lake Kariba, the world’s largest reservoir by volume and an example of what Batoka Gorge could become.

I am a river guide, and in October 2019, I embarked on a four-day trip down Batoka Gorge as part of a two-week river guide training. Most of our guides, Melvin Ndelelwa, James Linyando, and Emmanuel Ngenda, were from the Tokaleya villages. Ndelelwa, who was a porter before becoming a river guide, pulled out a picture of a fish he caught at a hidden pool below the falls. It was almost as big as he is. His father was a porter his whole life. Becoming a raft guide in Zambia is hard work. The possibility of learning to guide energizes the porters.

Ndelelwa explains how his younger brother carves ebony root to make Nyami Nyami necklaces. The Nyami Nyami is a mythic river god, a serpent with the head of a fish. Legend has it, this god is angry that his sweetheart is trapped downstream behind the giant Kariba Dam. In 1956, a year into construction, the Nyami Nyami flooded the river, wreaking havoc on the construction site. The odds of another flood in 1957 were a thousand to one. Yet the river rose three meters higher than before, destroying the bridge, cofferdam, and parts of the main wall.

The guides told us that the Nyami Nyami would protect us when we wear the necklace that honors his sweetheart. On the river, I touched mine often, praying for safe passage. I am terrified of big water and scared of flipping. The Zambezi is a huge volume river with little exposed rock. It is extremely challenging, with long and powerful rapids, steep gradients, and big drops. Flipping is common. In high-pressure areas, you can’t even depend on your life jacket to keep your head above water.

On the river, I clung to the raft in awe and terror at the size of the waves. October is the dry season, when the water is low. In December, the rains raise the river and turn it muddy brown. Linyando navigated ahead in a safety kayak while Ngenda captained our raft. At one point between rapids, he pointed out the camouflaged crocodiles sun-bathing on rocks.

Halfway through the training, I was invited to guide the most challenging rapid, Gulliver’s Travels. I had already guided the rapid just prior called Devil’s Toilet Bowl twice, but my angle was off on this third attempt. The raft flipped backwards. I went deep underwater. It was dark and silent. A shaft of light appeared. Then more light. I surfaced. We turned the boat upright, but my confidence was shaken. I thought of backing out of Gulliver’s Travels, until the guides encouraged me. Back in the boat, I sent the raft through.

Throughout the trip, I felt that the guides protected me. Ndelelwa offered his sandal for the steep hike out after I lost my shoe. “This is my home,” he said. “It’s easy for me to walk barefoot.” Later, when I encountered a puff adder — a venomous snake with a bite that can be deadly — near my sleeping bag, Ngenda helped me move closer to the fire. “We sleep here,” he said. “The snakes don’t like fire.” It smolders all night smoking fish for breakfast, a staple food in villages along the gorge.

IN 2015, THE WORLD BANK funded an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) that concluded that the dam is a “cheap” solution to the “electricity deficit” of Zambia and Zimbabwe. An airport and road have already been constructed. The reservoir of the 550-foot tall mega-dam will be 16 square miles and a half-mile from the put-in just below Victoria Falls, impacting a UNESCO World Heritage Site sacred to the Tokaleya peoples. The entire canyon will be drowned and destroyed.

IN 2015, THE WORLD BANK funded an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) that concluded that the dam is a “cheap” solution to the “electricity deficit” of Zambia and Zimbabwe. An airport and road have already been constructed. The reservoir of the 550-foot tall mega-dam will be 16 square miles and a half-mile from the put-in just below Victoria Falls, impacting a UNESCO World Heritage Site sacred to the Tokaleya peoples. The entire canyon will be drowned and destroyed.

If the dam build goes ahead, wildlife who live and breed in the gorge will be lost or displaced. The Cornish jack and bottlenose fish need fast-moving water to survive. The extremely rare Taita falcon is endemic to Batoka Gorge — it nests and breeds only here. The hooves of the small klipspringer antelope are designed to jump up and down the canyon. They will not be able to live on top. Leopards that live in the gorge will be forced to move to higher ground, becoming more vulnerable to hunting and poaching.

The ecological damage is layered with the human toll. Downstream from Batoka Gorge, the Kariba Dam, built in the late 1950s, displaced 57,000 Indigenous Gwembe Tonga and Kore Kore peoples, while stranding thousands of animals on islands. Kariba Dam has also demonstrated that imprisoning a river damages water quality, reduces the amount of water available for people and wildlife downstream, and harms the fertility of the land. Dams can also spread waterborne diseases such as malaria and schistosomiasis, while mega-dams may cause earthquakes and destructive floods.

Plus, the lifespan of a dam is 50 years. Less than 30 years after construction, Kariba Dam began falling apart, causing earthquakes and operating at less than 30 percent its proposed capacity. Falling water levels have made it increasingly less productive. The Chinese construction company regularly pours concrete into the wall to keep it from buckling. If it broke, it could cause a tsunami that would impact much of Mozambique and even Madagascar, potentially killing millions.

The Batoka Gorge project will cost around four billion dollars. It is supposed to take 10 to 13 years to complete, but some locals have noticed that high cost infrastructure projects often do not reach completion in Zambia. Increasing droughts due to climate change raise the question whether there will be enough water to operate a dam. Electricity generated is likely to be sold to foreign countries for income, while local people become poorer.

The dam will also displace river guides and most likely the villages along the gorge. Tourism is the third largest industry in Zambia. The governments say the dam’s construction will create jobs, but many of these jobs go to Chinese nationals hired by Chinese companies, and after construction ends, few will be needed to operate the dam. Some say the dam will create new tourism opportunities, like parasailing and wakeboarding, but crocodiles and hippos proliferate in flat water, making these activities risky.

China is rapidly expanding its global reach, including in Africa, through its Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious infrastructure project extending to 60 countries and counting. The country has already financed two Zambian airports and the Itezhi Tezhi Dam, and owns a 60 percent share of Zambia national broadcasting service. As many less developed countries borrow big money from China for big infrastructure projects, they are incurring large debts. The debt incurred can be crushing to the food supplies, health services, and education of local people. As Daimone Siulapwa writes in the Zambian Observer, huge kickbacks are the root of the problem. They motivate Zambian leaders to negotiate deals with China. Millions of dollars go missing. Projects are not finished. The natural world and local people suffer.

Most river guides hope the dam never happens, but local rafting companies are afraid to speak out against it. They fear repercussions — from being shot to having their passport or business license revoked. International support is imperative if we want to see this river protected.

ALONG THE RIVER, villagers carve and sell wooden figurines: elephants, rhinos, lions, water buffalo. Ndelelwa always buys some, though he does not need them. I bought carvings too, and the vendor insisted on giving me a few extra.

Then Ndelelwa invited me to his village to eat nshima, a traditional thick maize porridge. We sat outside the round mud huts with grass roofs. Five children ran over to look at me with toothy smiles and a wide-eyed curiosity. As we ate from one bowl, I thanked them in their dialect, “Ndalumba.”

If the river is dammed, I wonder, what will happen to these people? How will they survive?

The last time I flipped the raft on the Zambezi, the waves were gentle. We held the perimeter rope of the capsized boat as we floated through a narrow section of canyon. Ngenda smiled as he turned the boat upright.

Dam projects are rarely stopped in industrial civilization. Save the Zambezi formed to oppose the construction of this dam. They seek help in challenging the ESIA. This dam will likely go ahead unless there is an unprecedented outcry of resistance. The Nyami Nyami protected us on the river. Perhaps his rage may once again knock down any walls placed in his path. I touch my necklace and pray for the river.

Help stop the Batoka Gorge Dam:

Rebecca Wildbear is a river and soul guide who helps people tune in to the mysteries that live within the Earth community, dreams, and their own wild Nature, so they may live a life of creative service. She has been a guide with Animas Valley Institute since 2006 and is the author of the forthcoming book Playing & Praying: Soul Stories to Inspire Personal & Planetary Transformation.

Rebecca Wildbear is a river and soul guide who helps people tune in to the mysteries that live within the Earth community, dreams, and their own wild Nature, so they may live a life of creative service. She has been a guide with Animas Valley Institute since 2006 and is the author of the forthcoming book Playing & Praying: Soul Stories to Inspire Personal & Planetary Transformation.

Featured image: the Batoka Gorge photograph by Prof. Davis, 1905. CC BY 4.0.

by DGR News Service | Aug 26, 2020 | Mining & Drilling

In this article Julia Barnes describes the process of seabed mining and calls for organized resistance to this new ecocidal extraction industry. This article was originally published in Counterpunch

They want to mine the deep sea.

We shouldn’t be surprised. This culture has stolen 90% of the large fish, created 450 de-oxygenated areas, and murdered 50% of the coral reefs. It has wiped out 40% of the plankton. It has warmed and acidified the water to a level not seen since the Permian mass extinction. And indeed, there is another mass extinction underway. Given the ongoing assault on the ocean by this culture, there is serious question as to whether the upper ocean will be inhabitable by the end of this century.

For some people, a best-case scenario for the future is that some bacteria will survive around volcanic vents at the bottom of the ocean.

Deep sea mining is about to make that an unlikely possibility. It’s being touted as history’s largest mining operation. They have plans to extract metals from deposits concentrated around hydrothermal vents and nodules – potato sized rocks – which are scattered across the sea floor. Sediment will be vacuumed up from the deep sea, processed onboard mining vessels, then the remaining slurry will be dumped back into the ocean. Estimates of the amount of slurry that will be processed by a single mining vessel range from 2 to 6 million cubic feet per day. I’ve seen water go from clear to opaque when an inexperienced diver gives a few kicks to the sea floor.

Now imagine 6 million cubic feet of sediment being dumped into the ocean. To put that in perspective, that’s about 22,000 dump trucks full of sediment – and that’s just one mining vessel operating for one day. Imagine what happens when there are hundreds of them. Thousands of them.

Plumes at the mining site are expected to smother and bury organisms on the sea floor. Light pollution from the mining equipment would disrupt species that depend on bio-luminescence. Sediment plumes released at the surface or in the water column would increase turbidity and reduce light, disrupting the photosynthesis of plankton.

A few environmental groups are calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining.

Meanwhile, exploratory mining is already underway. An obscure organization known as the International Seabed Authority has been given the responsibility of drafting an underwater mining code, selecting locations for extraction, and issuing licenses to mining companies. Some companies claim that the damage from deep sea mining could be mitigated with proper regulations. For example, instead of dumping slurry at the surface, they would pump it back down and release it somewhere deeper.

Obviously, regulations will not stop the direct harm to the area being mined. But even if the most stringent regulations were put in place, there still exists the near-certainty of human error, pipe breakage, sediment spills, and outright disregard for the rules.

As we’ve seen with fisheries, regulations are essentially meaningless when there is no enforcement. 40% of the total catch comes from illegal fishing. Quotas are routinely ignored and vastly exceeded. On land, we know that corporations will gladly pay a fine when it is cheaper to do so than it is to follow the rules. But all this misses the point which is that some activities are so immoral, they should not be permitted under any circumstances.

Permits and regulations only serve to legalize and legitimize the act of deep sea mining, when a moratorium is the only acceptable response.

Canadian legislation effectively prohibits deep sea mining in Canada’s territorial waters. Ironically, Canadian corporations are leading the effort to mine the oceans elsewhere. A spokesperson from the Vancouver-based company Deep Green Metals attempted to defend deep sea mining from an environmental perspective,

“Mining on land now takes place in some of the most biodiverse places on the planet. The ocean floor, on the other hand, is a food-poor environment with no plant life and an order of magnitude less biomass living in a larger area. We can’t avoid disturbing wildlife, to be clear, but we will be putting fewer organisms at risk than land-based operations mining the same metals.” (as cited in Mining Watch).

This argument centers on a false choice.

It presumes that mining must occur, which is absurd. Then, it paints a picture that the only area affected will be the area that is mined. In reality, the toxic slurry from deep sea mining will poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles, with heavy metals like mercury and lead expected to bio-accumulate in everyone from plankton, to tuna, to sharks, to cetaceans.

A study from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that “A very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.”

The idea that fewer organisms are at risk from deep sea mining is an egregious lie.

Scientists have known since 1977 that photosynthesis is not the basis of every natural community. There are entire food webs that begin with organic chemicals floating from hydrothermal vents. These communities include giant clams, octopuses, crabs, and 10-foot tube worms, to name a few. Conducting mining in these habitats is bad enough, but the effects go far beyond the mined area.

Deep sea mining literally threatens every level of the ocean from surface to seabed. In doing so, it puts all life on the planet at risk. From smothering the deep sea, to toxifying the food web, to disrupting plankton, the tiny organisms who produce two thirds of the earth’s oxygen, it’s just one environmental disaster after another.

The most common justification for deep sea mining is that it will be necessary to create a bright green future.

A report by the World Bank found that production of minerals such as graphite, lithium, and cobalt would need to increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the growing demand for so-called renewable energy. There is an article from the BBC titled “Electric Car future May Depend on Deep Sea Mining”. What if we switched the variables, and instead said “the future of the ocean depends on stopping car culture” or “the future of the ocean depends on opposing so-called renewable energy”. If we take into account all of the industries that are eviscerating the ocean, it must also be said that “the future of the ocean depends on stopping industrial civilization”.

Evidently this culture does not care whether the ocean has a future. It’s more interested in justifying continued exploitation under the banner of green consumerism. I do not detail the horrors of deep sea mining to make a moral appeal to those who are destroying the ocean. They will not stop voluntarily. Instead, I am appealing to you, the reader, to do whatever is necessary to make it so this industry cannot destroy the ocean.

Julia Barnes is a filmmaker, director of Sea of Life and of the forthcoming film Bright Green Lies.

Featured image: deep-sea coral, Paragorgiaarborea, on the edge of Hendrickson Canyon roughly 1,775 meters or nearly 6000 feet underwater in the Toms Canyon complex in the western Atlantic. NOAA photo.

Following the actions from Food Not Bombs Bacolad, on November 8th Local Autonomous Networks held a discussion to consider the ongoing problem. They agreed to organize a coordinated Critical Mass Ride. The ride involved concerned people in the Archipelago from the different islands of the Philippines gathering to travel around the main city to raise awareness.

Following the actions from Food Not Bombs Bacolad, on November 8th Local Autonomous Networks held a discussion to consider the ongoing problem. They agreed to organize a coordinated Critical Mass Ride. The ride involved concerned people in the Archipelago from the different islands of the Philippines gathering to travel around the main city to raise awareness.