by DGR News Service | May 19, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Listening to the Land, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home, Toxification, White Supremacy

In this statement, Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (the People of Red Mountain), oppose the proposed Lithium open pit mines in Thacker Pass. They describe the cultural and historical significance of Thacker Pass, and also the environmental and social problems the project will bring.

We, Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (the People of Red Mountain) and our native and non-native allies, oppose Lithium Nevada Corp.’s proposed Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine.

This mine will harm the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, our traditional land, significant cultural sites, water, air, and wildlife including greater sage grouse, Lahontan cutthroat trout, pronghorn antelope, and sacred golden eagles. We also request support as we fight to protect Thacker Pass.

”Lithium Nevada Corp. (“Lithium Nevada”) – a subsidiary of the Canadian corporation Lithium Americas Corp. – proposes to build an open pit lithium mine that begins with a project area of 17,933 acres. When the Mine is fully-operational, it would use 5,200 acre-feet per year (equivalent to an average pumping rate of 3,224 gallons per minute) in one of the driest regions in the nation. This comes at a time when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation fears it might have to make the federal government’s first-ever official water shortage declaration which will prompt water consumption cuts in Nevada. Meanwhile, despite Lithium Nevada’s characterization of the Mine as “green,” the company estimates in the FEIS that, when the Mine is fully-operational, it will produce 152,703 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions every year.

Mines have already harmed the Fort McDermitt tribe.

Several tribal members were diagnosed with cancer after working in the nearby McDermitt and Cordero mercury mines. Some of these tribal members were killed by that cancer.

In addition to environmental concerns, Thacker Pass is sacred to our people. Thacker Pass is a spiritually powerful place blessed by the presence of our ancestors, other spirits, and golden eagles – who we consider to be directly connected to the Creator. Some of our ancestors were massacred in Thacker Pass. The name for Thacker pass in our language is Peehee mu’huh, which in English, translates to “rotten moon.” Pee-hee means “rotten” and mm-huh means “moon.” Peehee mu’huh was named so because our ancestors were massacred there while our hunters were away. When the hunters returned, they found their loved ones murdered, unburied, rotting, and with their entrails spread across the sage brush in a part of the Pass shaped like a moon. To build a lithium mine over this massacre site in Peehee mu’huh would be like building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery. We would never desecrate these places and we ask that our sacred sites be afforded the same respect.

Thacker Pass is essential to the survival of our traditions.

Our traditions are tied to the land. When our land is destroyed, our traditions are destroyed. Thacker Pass is home to many of our traditional foods. Some of our last choke cherry orchards are found in Thacker Pass. We gather choke cherries to make choke cherry pudding, one of our oldest breakfast foods. Thacker Pass is also a rich source of yapa, wild potatoes. We hunt groundhogs and mule deer in Thacker Pass. Mule deer are especially important to us as a source of meat, but we also use every part of the deer for things like clothing and for drumskins in our most sacred ceremonies.

Thacker Pass is one of the last places where we can find our traditional medicines.

We gather ibi, a chalky rock that we use for ulcers and both internal and external bleeding. COVID-19 made Thacker Pass even more important for our ability to gather medicines. Last summer and fall, when the pandemic was at its worst on the reservation, we gathered toza root in Thacker Pass, which is known as one of the world’s best anti-viral medicines. We also gathered good, old-growth sage brush to make our strong Indian tea which we use for respiratory illnesses.

Thacker Pass is also historically significant to our people.

The massacre described above is part of this significance. Additionally, when American soldiers were rounding our people up to force them on to reservations, many of our people hid in Thacker Pass. There are many caves and rocks in Thacker Pass where our people could see the surrounding land for miles. The caves, rocks, and view provided our ancestors with a good place to watch for approaching soldiers. The Fort McDermitt tribe descends from essentially two families who, hiding in Thacker Pass, managed to avoid being sent to reservations farther away from our ancestral lands. It could be said, then, that the Fort McDermitt tribe might not be here if it wasn’t for the shelter provided by Thacker Pass.

We also fear, with the influx of labor the Mine would cause and the likelihood that man camps will form to support this labor force, that the Mine will strain community infrastructure, such as law enforcement and human services. This will lead to an increase in hard drugs, violence, rape, sexual assault, and human trafficking. The connection between man camps and missing and murdered indigenous women is well-established.

Finally, we understand that all of us must be committed to fighting climate change. Fighting climate change, however, cannot be used as yet another excuse to destroy native land. We cannot protect the environment by destroying it.

Sign the petition from People of Red Mountain: https://www.change.org/p/protect-thacker-pass-peehee-mu-huh

Donate: https://www.classy.org/give/423060/#!/donation/checkout

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

by DGR News Service | May 18, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Culture of Resistance, Education, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

- The Philippine government has suspended work on a bridge that would connect the islands of Coron and Culion in the coral rich region of Palawan.

- Activists, Indigenous groups and marine experts say the project would threaten the rich coral biodiversity in the area as well as the historical shipwrecks that have made the area a prime dive site.

- The Indigenous Tagbanua community, who successfully fought against an earlier project to build a theme park, say they were not consulted about the bridge project.

- Preliminary construction began in November 2020 despite a lack of government-required consultations and permits, and was ordered suspended in April this year following the public outcry.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.

Featured image: The Indigenous Tagbanua community of Culion has slammed the project for failing to obtain their permission that’s required under Philippine law. Image by anne jimenez via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

by Keith Anthony S. Fabro

PALAWAN, Philippines — Nicole Tayag, 30, learned to snorkel at 5 when her father took her to the teeming waters of Coron to scout for potential tourist destinations back in 1995. One particularly biodiverse site they found was the Lusong coral garden, southwest of this island town in the Philippines’ Palawan province.

“Even just at the surface, I saw how lively the place was,” Tayag told Mongabay. “We drove our boat for so many times that I remember the passage as one of the places I see dolphins jumping and rays flying up the water. It has inspired me to see more underwater, which led me to my career as a scuba diver instructor now.”

Tayag said she holds a special place in her heart for Lusong coral garden. So when she heard that a government-funded bridge would be built through it, she said was concerned about its impact on the marine environment and tourism industry. Before the pandemic, the 644-hectare (1,591-acre) Bintuan marine protected area (MPA), which covers this dive site, received an average of 3,000 tourists weekly, generating up to 259 million pesos ($5.4 million) in annual revenue. Bintuan is one of the MPAs in the Philippines considered by experts as being managed effectively.

The planned 4.2 billion peso ($88.6 million) road from Coron to the island of Culion would run just over 20 kilometers (12.5 miles), of which only about an eighth would constitute the actual bridge span, according to a government document obtained by Mongabay.

Tayag said they’ve been hearing about the project for 20 years now. “[I] didn’t give much thought about it before, really.” Then, in March this year, Mark Villar, secretary of the Philippine Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), posted the project’s conceptual design on his Facebook page.

Tayag said she was shocked that the project was finally going through. “I was even more shocked when I realized it’s so close to historical dive sites and to coral garden,” she said.

Part of President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure program, construction of the Coron-Culion bridge was scheduled from 2020 to 2023. By November 2020, site clearing had already started in the area designated for the bridge’s access road. But on April 7 this year, the Philippine government announced it was suspending the project to ensure mitigating measures for its environmental impact are in place. This follows a public outcry from academics, civil society groups and nonprofit organizations that say the project is fraught with risks and irregularities.

“Without the concerned citizens and organizations who raised the alarm bell in this project, this would have gone in the way of so many so-called infrastructure projects, which are disregarding our sacred rights to a balanced and healthful ecology,” said Gloria Ramos, head of the NGO Oceana Philippines.

Cultural heritage collapse

Tayag is part of a group, Buklod Calamianes, that initiated an online petition seeking to stop the project. They warned of the damage that the bridge construction could pose to the marine environment, as it would sit within a 5-km (3-mi) radius of seven of the top underwater attractions in Coron and Culion. In addition to the Lusong coral garden, these dive sites include six Japanese shipwrecks from World War II.

“Heavy sedimentation from the construction will settle upon these fragile shipwrecks and potentially cause the collapse of these precious historical underwater sites,” said the petition, which has been signed by more than 19,000 people.

Palawan Studies Center executive director Michael Angelo Doblado said the shipwrecks need to be protected because they’re historically significant heritage sites of local and global importance. “These are evidence that important battles between the American and Japanese air and sea forces happened there.”

Doblado, who is also a professor of history at Palawan State University, said the occurrence of these shipwrecks also highlights that the Calamianes island group that includes Coron and Culion was important for the Japanese forces, whose weapons and other equipment relied on Coron as a source of manganese.

“For these wrecks and its local importance to Coron and its people, that would be left to them to decide,” he told Mongabay. “Is it really important for them historically as a municipality that they will be willing to preserve and protect it? Or will they be willing to sacrifice and give it up as a price for development?

“It also begs the question, if tourism is one of the major earners of Coron, and the proposed bridge … will boost its tourism, is it not ironic that the shipwrecks … will be directly affected by this infrastructure project that is supposed to boost tourism?”

The government had touted the bridge as improving connectivity between the islands to boost the tourism and agriculture sectors, among other benefits. But if it really wants to help the local tourism sector, Doblado said, the government “should have carried out a construction plan that skirts or avoids destroying or affecting these shipwrecks which are famous dive sites and considered as artificial reefs that promote aquatic growth and diversity in that area.”

This would swell the construction cost, he said, but would be vital to saving not only the historical underwater ruins but the marine environment and tourism industry in the long run.

Impact on marine ecosystems

The Philippines has around 25,000 square kilometers (9,700 square miles) of coral reefs, the world’s third-largest extent, and its waters are known for the highest biodiversity of corals and shore fishes, a 2019 study noted. However, the same study showed that the country, located at the apex of the Pacific Coral Triangle, lost about a third of its reef corals over the past decade, and none of the reefs surveyed were in a condition that qualified as “excellent.”

The bridge project added to concerns about the loss of hard-coral cover. Tayag’s group estimated that it would affect 334 hectares (825 acres) of corals, as well as 140 hectares (346 acres) of mangroves. It said the heavy sedimentation, runoff and silt from the construction could cloud the water, blocking the sunlight that’s essential for the growth of the algae that, in turn, nourish the corals.

Coral expert Wilfredo Licuanan from De La Salle University in Manila told Mongabay that the corals and the abundance of sea life they support are quite sensitive to water quality change due to sedimentation. “If you have sediments … their feeding structures are clogged, light penetration is hindered … and then there’s general smothering of life on the sea bottom.”

When corals are undernourished, he said, it can prevent the calcium carbonate accumulation that constitutes reef growth and that takes tens of thousands of years. “If the corals are not able to produce enough calcium carbonate, your reef is not able to continue to grow and … will start eroding,” Licuanan said.

Once that happens, the reefs will not be able to keep up with climate change-induced sea level rise, and will cease to protect the coastlines from big waves and to serve as habitat for many other species, including those that feed fishing communities. “So, all the ecosystem services of coral reefs are dependent on the position of calcium carbonate skeleton,” Licuanan said.

“Any construction activity, be it road building, resort construction, anything of that sort requires that you move earth,” Licuanan said. “You dig, you relocate soil, and so on. And almost always, that means a lot of the soil gets mobilized and is brought to the sea, causing sedimentation.”

That impact to the reef ecosystem will reverberate up to the residents who depend on it for their livelihoods, said Miguel Fortes, a marine scientist and professor at the University of the Philippines. “If you destroy one, you’re actually destroying the other,” he said in an Oceana online forum.

Fortes said it takes about 35 years for damaged coral reefs to recover. That compares to about 25 years for mangroves and a year for seagrass, both of which are useful in mitigating climate change, he said. In Coron and Culion, these ecosystems provide estimated annual economic benefits of 3.7 billion pesos ($77.2 million), on top of the 4.1 billion pesos ($85.2 million) generated by the islands’ recreation zones.

Coron Bay’s fisheries production is an important spawning and nursery ground, said Jomel Baobao, a fisheries management specialist with the nonprofit Path Foundation Inc., one of the partner implementers of the USAID Fish Right project. The five communities adjacent to the bridge project alone stand to benefit from a total estimated yield of 89 million pesos ($1.8 million) annually.

“A USAID-funded larval dispersal study showed that Bintuan area is the sink for larvae that come from different sources, making it a rich nursery ground,” Baobao told Mongabay. He added that Coron Bay serves to funnel larvae from the Sulu Sea and West Philippine Sea, and any disruption to that flow could affect fishing yields in Bintuan and other areas.

“The narrowest portion in the bay located in Bintuan where the bridge will be constructed is significant to water exchange between these two seas,” Baobao said. This might be affected if there will be ecosystem loss or destruction in the area because of the bridge.”

The area’s reefs are home to economically important species such as red grouper, lobster and round scad, as well as giant clams, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. Among the coral species that flourish around the Calamianes island group are two endangered ones: Pectinia maxima and Anacropora spinosa. In the Philippines, the latter is found only in the Calamianes.

No green permits

Preliminary tree cutting and clearing of the road leading to the bridge entrance reportedly began in November 2020, raising fears that it could trigger siltation that could jeopardize the marine park.

In a 2020 paper, Licuanan said that management actions, such as enhanced regulation of road construction on slopes leading to the sea and rivers that open into the sea, and consequent limitations on government infrastructure programs that impinge on these critical areas, are crucial in conserving the country’s remaining coral reefs.

“Road building practices locally are particularly destructive because they [the DPWH and private contractors] rarely prioritize soil conservation,” he told Mongabay.

But despite the recent activity, the project has not received the green light from the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), a provincial government agency. PCSD spokesman John Vincent Fabello told Mongabay that no strategic environmental plan (SEP) clearance has been issued to the DPWH for the project. The clearance would essentially guarantee that the high-impact project is located outside ecologically critical zones like marine parks.

“They [DPWH] don’t have an SEP clearance yet,” Fabello said. “Government big-ticket projects still have to [go] through the SEP clearance system of the PCSD. Administrative fines shall be imposed if building commences without the necessary clearance and permits from PCSD and related agencies.”

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) said it will also require the DPWH to undertake an environmental impact assessment to obtain an environmental compliance certificate and tree cutting permit for the project. “Government projects will still go through the permitting; you have to follow the process … but it will be faster,” said DENR regional director Maria Lourdes Ferrer.

The DPWH confirmed it had not undertaken the required public consultations, feasibility study, or permit applications prior to the start of construction activities. DPWH regional director Yolanda Tangco said they fast-tracked the construction work because the initial 250 million pesos ($5.2 million) in project funding released to the agency in 2020 would have to be returned to the treasury if it was not spent within two years.

Fortes said this reasoning is unacceptable because projects should not only be politically expedient but also based on scientific evidence and actual user needs.

“To me, this means money still supersedes more vital imperatives [such as] cultural and ecological,” he said. “Poor planning is evident here because it entails huge sacrifices.”

Tangco said her office expects to receive additional construction funding for 2021 to 2023 from the national government. “But if we have decided not to continue it, we will remove it [in our proposal]. Most probably, we will revert the funding and terminate the contract,” she said.

She added that in the feasibility study expected to be completed in July 2021, the public works office is considering two more route options: “Our alignment isn’t fixed. If we can find an alignment with lesser impacts to the environment and Indigenous people, we will pursue that and issue variation and change orders [to the contractor].”

Indigenous communities fight back

The Indigenous Tagbanua community of Culion has slammed the project for failing to obtain their permission through a process of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), required under Philippine law.

“We don’t want that bridge here because we fear that it will affect many — our seas, our livelihoods, our lands we inherited from our ancestors,” Indigenous federation chairman Larry Sinamay, who organized a rally on April 5, told Mongabay. “Where would we get our food when our place is destroyed by this project?”

“The social and sacred value of this traditional space to the Tagbanua should be respected by every member of the community, even us outsiders, tourists and developers,” said Kate Lim, an archaeologist who has conducted studies in the region. “The concept of ancestral domain is that it’s communal and utilized by everyone and not just by one sector only.”

In a letter dated March 31, the federation of 24 Tagbanua communities appealed to the national government to halt the project’s preliminary construction activities, pending impact assessments.

“If we receive no response to our plea, we will be forced to seek legal remedies to fight for our Indigenous rights provided under the Philippine Constitution, Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act, and other laws related to environment and natural resources,” the federation said at the time.

The Tagbanuas have experience standing up to projects they see as imperiling their environment and culture. In 2017, they banded together to stop a proposed Nickelodeon theme park, which also lacked the necessary scientific studies, consultations and permits.

“Even if we are battling a pandemic, we can’t forget that our battle to protect Palawan’s natural resources must go on,” said Anna Oposa, executive director of Save Philippine Seas, who joined the Tagbanuas in fighting the Nickelodeon project. “The Tagbanua IPs have the experience and power to block or at the very least significantly delay this potentially destructive project and come to a consensus with other stakeholders.”

While the public pressure has prompted the government to suspend the project, the community says it isn’t dropping its guard.

“In a time of pandemic and lockdowns, projects are easily sneaked in and started out of the public’s eye who are confined in their homes,” Tayag said.

“We are closely monitoring these bateltelan [hard-headed] officials. We trust that the government offices looking into this project will do what is right and not just focus on its ‘good intention.’”

Citations:

Licuanan, W. Y., Robles, R., & Reyes, M. (2019). Status and recent trends in coral reefs of the Philippines. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 142, 544-550. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.013

Licuanan, W. Y. (2020). Current management, conservation, and research imperatives for Philippine coral reefs. Philippine Journal of Science, 149(3), ix-xii. Retrieved from https://philjournalsci.dost.gov.ph/publication/regular-issues/past-issues/98-vol-149-no-3-september-2020/1225-current-management-conservation-and-research-imperatives-for-philippine-coral-reefs-2

by DGR News Service | May 17, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Education, Indirect Action, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Toxification

Nearly 100,000 people have signed a petition calling for the closure of a controversial oil and gas facility that has sickened residents of the U.S. Virgin Island. We in DGR deeply care about social justice, so we think it is important to expect president Biden to act against structural racism by shutting down an oil and gas facility that is poisoning a predominantly black community. But there are many oil refineries in the world and each one is poisoning their surrounding communities, human and nunhuman. As long as this cultures addiction to fossil fuels continues, it will obviously continue poisoning human and nonhuman communities.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

By Reynard Loki

A controversial oil refinery on St. Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands, is in the government’s crosshairs after a third incident in just three months has sickened people. On May 5, after gaseous fumes were released from one of the oil refining units of Limetree Bay Refining, residents of the unincorporated Caribbean territory reported a range of symptoms, including burning eyes, nausea and headaches, with at least three people seeking medical attention at the local hospital. At its peak in 1974, the facility, which opened in 1966, was the largest refinery in the Americas, producing some 650,000 barrels of crude oil a day. It restarted operations in February after being shuttered for the past decade.

A Limetree spokesperson said that there was a release of “light hydrocarbon odors” resulting from the maintenance on one of the refinery’s cokers, high heat level processing units that upgrade heavy, low-value crude oil into lighter, high-value petroleum products. The noxious odor stretched for miles around the refinery, remaining in the air for days and prompting the closure of two primary schools, a technical educational center and the Bureau of Motor Vehicles (BMV), which local officials said was shuttered because its employees “are affected by the strong, unpleasant gas like odor, in the atmosphere.”

Limetree and the U.S. government conducted their own air quality testing, with different results. The National Guard found elevated levels of sulfur dioxide, while the company said it detected “zero concentrations” of the chemical just hours later. “We will continue to monitor the situation, but there is the potential for additional odors while maintenance continues,” said Limetree, which is backed by private equity firms EIG and Arclight Capital, the latter of which has ties to former President Donald Trump. “We apologize for any impact this may have caused the community.”

The May 5 incident follows two similar incidents in April at the refinery that the Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR) concluded were caused by the emission of excess sulfur dioxide from the burning of hydrogen sulfide, one of the impurities in petroleum coke, a coal-like substance that accounts for nearly a fifth of the nation’s finished petroleum product exports, mainly going to China and other Asian nations, where it is used to power manufacturing industries like steel and aluminum. Days after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) told the company that it was violating the Clean Air Act after the April incidents, Limetree agreed to resume sulfur dioxide monitoring, while contesting the violation. “If EPA makes a determination that the facility’s operations present an imminent risk to people’s health, consistent with its legal authorities, it will take appropriate action to safeguard public safety,” the agency said in a statement. The Biden EPA withdrew a key federal pollution permit for Limetree on March 25, but stopped short of shutting down the facility altogether.

Care2 has launched a public petition—already signed by more than 98,000 people—urging President Biden to shut down the Limetree Bay Refining facility. The petition also notes the risk that the refinery poses to the island’s biodiverse wildlife, saying that “turtles, sharks, whales, and coral reefs… [are] threatened by the Limetree Bay Refining plant—both by what it’s done in the past, and by what it’s spewing right now.” The group also frames the human rights and environmental justice aspect of the ongoing public health situation on the island in historical terms: “On top of the obvious problem that no person should be poisoned with oil, St. Croix is an island with a highly disenfranchised population. The vast majority of residents are Black, the [descendants] of enslaved Africans brought to work on sugar and cotton plantations. For generations, the U.S. government has cared little about the well-being of people there.” (One recent example happened in the wake of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, which landed on the island in September of 2017. Even two months after the storms hit, many residents of St. Croix who were evacuated to Georgia were unable to return home, and felt abandoned by the government. “I feel like we are the forgotten people and no one has ever inquired how do we feel,” said one of the St. Croix evacuees at the time.)

After the May 5 incident, Limetree said, “Our preliminary investigations have revealed that units are operating normally.” Perhaps it is normal for such facilities to emit toxic fumes. But what’s not normal is the fact that such fumes should present a constant threat to people and the environment, and that, according to the environmental group Earthjustice, about 90 million Americans live within 30 miles of at least one refinery. Adding insult to injury is the fact that Black people are 75 more likely to live near toxic, air-polluting industrial facilities, according to Fumes Across the Fence-Line, a report produced by the NAACP and the Clean Air Task Force, an air pollution reduction advocacy group. That report also found that more than 1 million African Americans face a disproportionate cancer risk “above EPA’s level of concern” due to the fact that they live in areas that expose them to toxic chemicals emanating from natural gas facilities.

You don’t need to live next door to a refinery to feel its impact on your health; in fact, you can be several miles away. A study conducted last year by researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) found an increased risk of multiple cancer types associated with living within 30 miles of an oil refinery. “Based on U.S. Census Bureau data, there are more than 6.3 million people over 20 years old who reside within a [30-mile] radius of 28 active refineries in Texas,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Stephen B. Williams, chief of urology and a tenured professor of urology and radiology at UTMB. “Our team accounted for patient factors (age, sex, race, smoking, household income and education) and other environmental factors, such as oil well density and air pollution and looked at new cancer diagnoses based on cancers with the highest incidence in the U.S. and/or previously suspected to be at increased risk according to oil refinery proximity.”

In granting Limetree’s permit in 2018—a move that E&E News reported was made to “cash in on an international low-sulfur fuel standard that takes effect in January [2020]”—Trump’s EPA said that the refinery’s emissions simply be kept under “plantwide applicability limit.” But then in a September 2019 report on Limetree—which has been at the center of several pollution debacles and Clean Air Act violations for decades—the agency said that “[t]he combination of a predominantly low income and minority population in [south-central] St. Croix with the environmental and other burdens experienced by the residents is indicative of a vulnerable community,” and added the new requirement of installing five neighborhood air quality monitors. “[G]iven several assumptions and approximations… and the potential impacts on an already overburdened low income and minority population, the ambient monitors are necessary to assure continued operational compliance with the public health standards once the facility begins to operate,” the agency stated. Limetree has appealed this ruling with the EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board, arguing that “the EPA requirements are linked to environmental justice concerns that are unrelated to operating within the pollution limits of the permit.”

“It is unclear when the EPA’s appeals board will rule on the permit dispute. The Biden-run EPA could withdraw the permit, and it is also reviewing whether the refinery is a new source of pollution that requires stricter air pollution controls,” reports Reuters, adding that the White House declined to comment.

President Biden has made environmental justice a central part of his policy, including the overhaul of the EPA External Civil Rights Compliance Office, which is responsible for enforcing civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex or disability. “For too long, the EPA External Civil Rights Compliance Office has ignored its requirements under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,” states Biden’s environmental justice plan. “That will end in the Biden Administration. Biden will overhaul that office and ensure that it brings justice to frontline communities that experience the worst impacts of climate change and fenceline communities that are located adjacent to pollution sources.”

Now it is time for Biden to make good on his campaign promise. John Walke, senior attorney and director of clean air programs with the Natural Resources Defense Council, told Reuters in March that the situation in St. Croix “offers the first opportunity for the Biden-Harris administration to stand up for an environmental justice community, and take a strong public health and climate… stance concerning fossil fuels.”

Earth | Food | Life contributor Sharon Lavigne has previously written about a similar issue in another region before. Lavigne is the founder and president of RISE St. James, a grassroots faith-based organization dedicated to opposing the siting of new petrochemical facilities in a heavily industrialized area along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as “Cancer Alley.” Writing in Truthout in October 2020 about St. James Parish, Louisiana, the predominantly Black and low-income community where she lives, Lavigne pointed out that “Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden mentioned St. James Parish in his clean energy plan speech because we’re notorious for having the country’s highest concentration of chemical plants and refineries, [one of] the highest cancer rates, the worst particulate pollution and one of the highest mortality rates per capita from COVID-19 in the nation,” She added, “For those of us living here, it’s not just Cancer Alley; it’s death row.”

The stated mission of the EPA is “to protect human health and the environment.” When so many Americans face a disproportionate cancer risk simply by living near toxic industrial sites such as oil and gas refineries, the EPA is derelict in its duty. The Limetree Bay Refining facility has presented President Biden with an early test of his commitment to environmental justice. Considering the facility’s terrible legacy of ecological and civil rights violations, three new public health incidents in just the past two months, and the disproportionate and ongoing health risks faced by the community’s predominantly Black and low-income population, it is finally time for the federal government to revoke Limetree’s license to operate on St. Croix. This is a perfect chance for President Biden to show the country and the world just how serious he is about environmental justice.

Reynard Loki is a writing fellow at the Independent Media Institute, where he serves as the editor and chief correspondent for Earth | Food | Life. He previously served as the environment, food and animal rights editor at AlterNet and as a reporter for Justmeans/3BL Media covering sustainability and corporate social responsibility. He was named one of FilterBuy’s Top 50 Health & Environmental Journalists to Follow in 2016. His work has been published by Yes! Magazine, Salon, Truthout, BillMoyers.com, AlterNet, Counterpunch, EcoWatch and Truthdig, among others.

by DGR News Service | May 16, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Building Alternatives, Climate Change, Culture of Resistance, Strategy & Analysis

This article originally appeared on Roarmag.

Editor’s note: Asking questions, questions that emerge from your empathy if you care for life on the planet, and questions that emerge from your confusion if you see that so many things are going so badly wrong, is a very important, crucial step. We completely agree with the last paragraph of this article and our answer is DGR’s Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy.

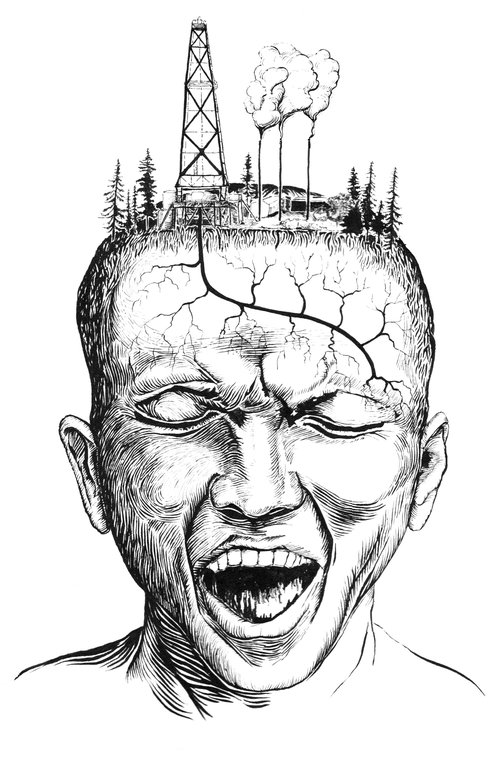

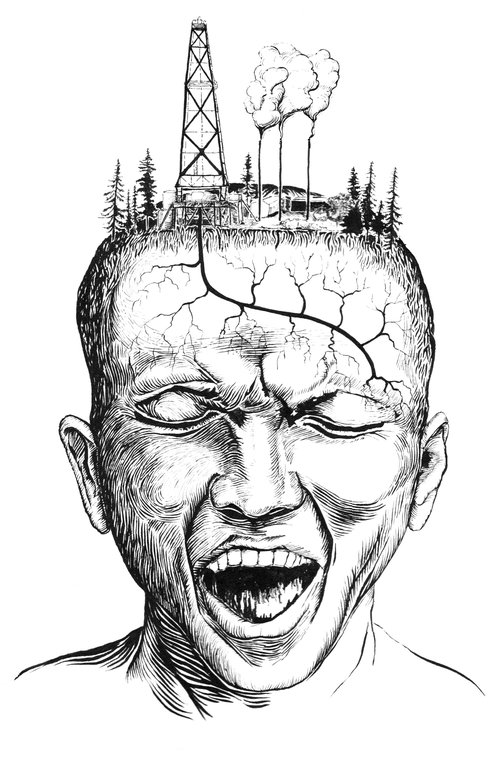

Featured image: “Frack Off” by Nell Parker.

By John Holloway

This is an adapted version of John Holloway’s presentation at the “Crisis of Nation States — Anarchist Answers” conference.

We do not know how to stop the planetary destruction caused by capital — but by asking the right questions we can find our way forward together.

We live in a failed system. It is becoming clearer every day that the present organization of society is a disaster, that capitalism is unable to secure an acceptable way of living. The COVID-19 pandemic is not a natural phenomenon but the result of the social destruction of biodiversity and other pandemics are likely to follow. The global warming that is a threat to both human and many forms of non-human life is the result of the capitalist destruction of established equilibria. The acceptance of money as the dominant measure of social value forces a large part of the world’s population to live in miserable and precarious conditions.

The destruction caused by capitalism is accelerating. Growing inequality, a rise in racist violence, the spread of fascism, increasing tensions between states and the accumulation of power by police and military. Moreover, the survival of capitalism is built on an ever-expanding debt that is doomed to collapse at some point.

The situation is urgent, we humans are now faced with the real possibility of our own extinction.

How do we get out of here? The traditional answer of those who are conscious of the scale of social problems: through the state. Political thinkers and politicians from Hegel to Keynes and Roosevelt and now Biden have seen the state as a counterweight to the destruction wreaked by the economic system. States will solve the problem of global warming; states will end the destruction of biodiversity; states will alleviate the enormous hardship and poverty resulting from the present crisis. Just vote for the right leaders and everything will be all right. And if you are very worried about what is happening, just vote for more radical leaders — Sanders or Corbyn or Die Linke or Podemos or Evo Morales or Maduro or López Obrador — and things will be fine.

The problem with this argument is that experience tells us that it does not work. Left-wing leaders have never fulfilled their promises, have never brought about the changes that they said they would. In Latin America, the left-wing politicians who came to power in the so-called Pink Wave at the start of this century, have been closely associated with extractivism and other forms of destructive development. The Tren Maya which is Mexican president López Obrador’s favorite project in Mexico at the moment is just the latest example of this. Left-wing parties and politicians may be able to bring about minor changes, but they have done nothing at all to break the destructive dynamic of capital.

THE STATE IS NOT THE ANSWER

But it is not just experience that tells us that the state is not the counterweight to capital that some make it out to be. Theoretical reflection tells us the same thing. The state, which appears to be separate from capital, is actually generated by capital and depends on capital for its existence. The state is not a capitalist and its workers do not on the whole generate the income it needs for its existence. That income comes from the exploitation of workers by capital, so that the state actually depends on that exploitation, that is, on the accumulation of capital, to reproduce its own existence.

The state is obliged, by its very form, to promote the accumulation of capital. Capital, too, depends on the existence of an instance — the state — that does not act like a capitalist and that appears to be quite separate from capital, to secure its own reproduction. The state appears to be the center of power, but in fact power lies with the owners of capital, that is, with those persons who dedicate their existence to the expansion of capital. In other words, the state is not a counterweight to capital: it is part of the same uncontrollable dynamic of destruction.

The fact that the state is bound to capital means that it excludes us. State democracy is a process of exclusion that says: “Come and vote every four or five years, then go home and accept what we decide.” The state is the existence of a body of full-time officials who assume the responsibility of ensuring the welfare of society — in a way compatible with the reproduction of capital, of course. By assuming that responsibility, they take it away from us. But, whatever their intentions, they are unable to fulfill the responsibility, because they do not have the countervailing power that they appear to have: what they do and how they do it is shaped by the need to ensure the reproduction of capital.

Just now, for example, politicians are talking of the need for a radical change in political direction as the world emerges from the pandemic, but at no point does any politician or government official suggest that part of that change in direction must be the abolition of a system based on the pursuit of profit.

If the state is not the answer to ending capitalist destruction, then it follows that channeling our concerns into political parties cannot be the answer either, since parties are organizations that aim to bring about change through the state. Attempts to bring about radical change through parties and the taking of state power have generally ended in the creation of authoritarian regimes at least as bad as those they fought to change.

ASKING WE WALK

So, if the state is not the answer, where do we go? How do we get out of here? We come to a conference like this, of course, to discuss anarchist answers. But there are at least three problems: firstly, there are not the millions of people here that we need for a real change of direction; secondly, we have no answers; and thirdly, the label “anarchist” probably does not help.

Why are there not millions of people here? There is certainly a widespread growing feeling of anger, desperation and an awareness that the system is not working. But why is this anger channeled either towards left-reformist parties and candidates (Die Linke, Sanders, Corbyn, Tsipras) or to the far right, and not towards efforts that push against-and-beyond the system? There are many explanations, but one that seems important to me is Leonidas Oikonomakis’ comment on the election of Syriza in Greece in 2015 that, even after years of very militant anti-statist protest against austerity, it still seemed to people that the state was the “only game in town.”

When we think of global warming, of stopping violence against women, of controlling the pandemic, of resolving our economic desperation in the present crisis, it is still hard not to think that the state is where the answers lie, even when we know that it is not.

Perhaps we have to give up the idea of answers. We have no answers. It cannot be a question of opposing anarchist answers to state answers. The state gives answers, wrong answers. We have questions, urgent questions, new questions because this situation of impending extinction has never existed before. How can we stop the destructive dynamic of capital? The only answer that we have is that we do not know.

It is important to say that we do not know, for two reasons. Firstly because it happens to be true. We do not know how we can bring the present catastrophe to an end. We have ideas, but we really do not know. And secondly, because a politics of questions is very different from a politics of answers. If we have the answers, it is our duty to explain them to others. That is what the state does, that is what vanguardist parties do. If we have questions but no answers, then we must discuss them together to try and find ways forward. “Preguntando caminamos,” as the Zapatistas say: “Asking we walk.”

The process of asking and listening is not the way to a different society, it is already the creation of a different society. The asking-listening is already a mutual recognizing of our distinct dignities. We ask-and-listen to you because we recognize your dignity. This is the opposite of state politics. The state talks. It pretends to ask-and-listen but it does not and cannot because its existence depends on reproducing a form of social organization based on the command of money.

Our asking-listening is an anti-identitarian movement. We recognize your dignity not because you are an anarchist or a communist, or German or Austrian or Mexican or Irish, or because you are a woman or Black or Indigenous. Labels are very dangerous — even if they are “nice” labels — because they create identitarian distinctions. To say “we are anarchists” is self-contradictory because it reproduces the identitarian logic of the state: we are anarchists, you are not; we are German, you are not. If we are against the state, then we against its logic, against its grammar.

A MOVEMENT OF SELF-DETERMINATION

We have no answers, but our walking-asking does not start from zero. It is part of a long history of walking-asking. Just in these days we are celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune and the centenary of the Kronstadt Uprising. In the present, we have the experience of the Zapatistas to inspire us, just as they are preparing their journey across the Atlantic to connect with the walkers-askers against capital in Europe this summer. And of course we look to the deeply ingrained practice of councilism in the Kurdish movement in the terribly difficult conditions of their struggle. And beyond that, the millions of cracks in which people are trying to organize on an anti-hierarchical, mutually recognitive basis.

It is simply not true that the state is the only game in town. We must shout from the rooftops that there is another, long-established game: the game of doing things ourselves, collectively.

Organization in the communal or council tradition is not on the basis of selection-and-exclusion but on the basis of a coming-together of those who are there, whether in the village or the neighborhood or the factory, with all their differences, their squabbles, their madnesses, their meannesses, their shared interests and common concerns.

The organization is not instrumental: it is not designed as the best way of reaching a goal, for it is itself its own goal. It does not have a defined membership since its aim is to draw in, not to exclude. Its discussions are not aimed at defining the correct line, but at articulating and accommodating differences, at constructing here and now the mutual recognition that is negated by capitalism.

This does not mean a suppression of debate, but, on the contrary, a constant process of discussion and critique aimed not at eliminating or denouncing or labeling the opponent but at maintaining the creative tension that arises from holding together ideas that push in slightly different directions. An always difficult mutual recognizing of dignities that pull in different directions.

The council or commune is a movement of self-determination: through asking-listening-thinking we shall decide how we want the world to be, not by following the blind dictates of money and profit. And, perhaps more and more important, it is an assumption of our responsibility for shaping the future of human life.

If we reach the point of extinction, it will be of no help to say on the last day: “It is all the fault of the capitalists and their states.” No. It will be our fault if we do not break the power of money and take back from the state our responsibility for the future of human life.

John Holloway is a professor of sociology in the Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. His books include Change the World without Taking Power (Pluto Press, London, 2002, 2019) and Crack Capitalism (Pluto Press, London, 2010).

by DGR News Service | May 15, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Human Supremacy, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

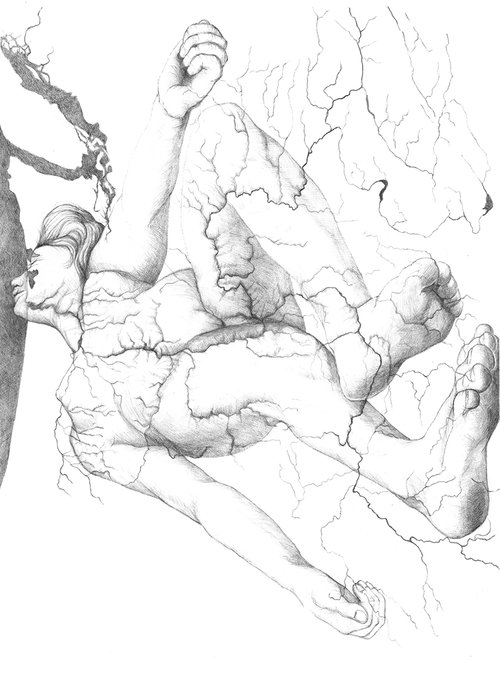

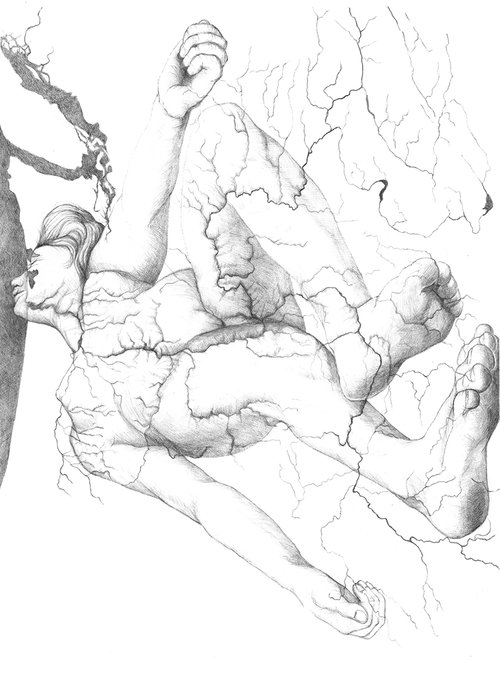

This is an edited transcript of this Deep Green episode. Featured image: “Watershed” by Nell Parker.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about aquifers.

As we know, this culture is drawing down aquifers around the world. Aquifers are underground rivers, lakes, seeps – it’s underground water and they can be anywhere from just six inches below the surface down to about 10,000 feet and they are being drawn down around the world.

We’ve heard of the Ogallala aquifer – it’s is an absolutely huge aquifer that has been used for irrigation for the last hundred years – it’s being drawn down terribly. Aquifers can recharge but it’s very slow. The other thing that’s happening to aquifers around the world is that they’re being poisoned – sometimes unintentionally as people pollute the ground and it leaches down into the groundwater and sometimes intentionally as in fracking or fracking for geothermal. The latter are “green”; where they put chemicals down and then explode the rocks into a billion pieces so they can frack out the oil or they can then allow the heated water to escape to the surface which they use to generate electricity. When you poison an aquifer – if recharging an aquifer takes a long, long, long, long, long time – detoxifying an aquifer takes that same amount of time, longer. I don’t even know how long it takes before an aquifer would become detoxified. It’s all a very, very, very stupid idea.

I’ve said many times that my environmentalism – I love the natural world, I love bears, I love salmon and I love trees – but my environmentalism also emerges from a fundamental conservatism, that I think it’s really, really, stupid to create a mess that you can’t fix. You know, if you drive salmon extinct that’s a mess you can’t fix because you can’t bring them back, and if you toxify an aquifer you’ve created a mess that you can’t fix. This is something I learned very young from my mom. If you make a mess you clean it up and if you cannot clean up that mess you don’t make it in the first place.

None of that is the point on why I want to bring this up. There are a lot of studies that have been done about who lives in these aquifers. They make up about 40% of the microbial habitat on the planet and account for I think 20% of the microbial population on the planet – viruses, archaea, bacteria and also fungi down to maybe a hundred feet; fungi don’t go much lower in the aquifer. Without bacteria we would all die almost instantly. Bacteria do the real work of life on this planet.

There have been a fair number of studies done on who lives down there;

and I have seen a fair number of people express concern over the drawdown of aquifers; and this concern is always expressed in terms of if “we keep drawing it down we can’t draw down more”. “If we empty the Ogallala aquifer how are we going to irrigate?” It’s always self-centered. The same with toxification; “if we toxify this water then when we put in a well our water is going to catch on fire or we won’t be able to drink the water.”

They may exist but I have yet to see one person, one person, in the entire world express concern for the aquifer communities as communities themselves. That person may exist but I’ve never heard of them and if that person does care about those communities as communities, as biomes – I mean there are people who say “gosh I love the grasslands” and “I wish the grasslands were there because I love buffalo and I love buffalo for their own sake”; “I love beavers for their own sake”; “I love old growth forests for their own sake.” I’ve never heard anybody say the Ogallala aquifer should not be drained because it is a biome, a community, of its own and has the right to exist for its own sake without us drawing it down and without us toxifying it. If anybody does care about them and works on these issues, I would love to interview you; but this is not an ad for that. I want to raise the issue.

It took me years of thinking about aquifers before it occurred to me that they’re their own communities

and now I’m the only person I know who thinks about this – that when they’re drawn out that’s harming those communities. I want for that to start to become part of the public conversation about aquifers – that not only do aquifers provide water for us and for everybody else; not only do aquifers provide hugely – here’s one thing, when an aquifer collapses the soil subsides above it and I just read an article a few days ago about how that that causes tremendous harm to infrastructure; it’s like and..? AND..? And how about the ecological infrastructure? How about the communities who live down there? How about the surface native communities? I want to make it part of the public conversation that aquifers exist for their own sake. They have their own beingness and their own communities and those communities are just as important to them as your community is to you and my community is to me.