by DGR News Service | Feb 20, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Direct Action, Mining & Drilling, Obstruction & Occupation, The Problem: Civilization

A beautfiul description of Thacker Pass by Will Falk | Feb 7, 2021

If you look across Thacker Pass from the shoulders of the Montana mountains, the land looks like a quilt the Double-H mountains in the south pulled up to their chin to keep warm during the cold winter nights. The hills that roll towards the valley floor are checkered with patterns. Much of the quilt, where the old-growth sagebrush persists, is an unbroken viridescent pattern. On the edges of the sagebrush, flaxen, rectangular patches of invasive grasses have sprung up from the wreckage created by the Bureau of Land Management’s clear-cutting chains. Separating the green and yellow patches, are lines of muddy brown where dirt roads have been built.

In places – my favorite places – the quilt bunches up into folds.

Those folds conceal nooks, crannies, alcoves, and cubbyholes where pygmy rabbits hide from prairie falcons, pronghorn antelope hide from rifle scopes, and I hide from the wind, sun, and the near-impossibility of stopping Lithium Americas’ open pit lithium mine.

Max and I received a second 24-hour notice to vacate Thacker Pass from BLM and the other lawyers we’ve been working with strongly advised us to heed this notice. They warned us that, if we were arrested, a federal judge would likely only release us from jail on the condition that we not return to Thacker Pass. If a judge released us on these conditions, to return to Thacker Pass would risk another arrest and more criminal charges filed against us. If we were arrested a second time, a judge would likely keep us incarcerated until the criminal charges filed against us were resolved.

We decided that being arrested when construction was not immediately imminent was not strategic – especially if it meant keeping us permanently away from Thacker Pass. Meanwhile, reinforcements had arrived who could hold down the occupation site and ensure a continuous presence at Thacker Pass. So, we decided it would be a good time to take a few days to shower and do some laundry.

The afternoon before we had to leave, I wandered down into Thacker Pass’ deepest refuge, into the rolling sagebrush hills that form the warmest section of the quilt – the same rolling hills, the same section of the quilt that will be ripped out for an open pit mine if Lithium Americas has its way.

But, I found no refuge there.

I took a dirt road still covered with the kind of old snow that preserves animal tracks the best. Rabbits, mice, kangaroo rats, sage grouses, red foxes, and coyotes had all found this dirt road useful before me. Seeing my clumsy, heavy boot tracks next to the artwork these creatures created with their feet embarrassed me. Every twenty yards or so, I stopped to study the tracks and to visualize the animal who had left them. When I saw rabbit and coyote tracks converge in the crimson of blood spilled over the cream of snow, the voices of coyotes a few hills away protested my voyeurism. Sacred predation, they insisted, is an intimate thing.

As I wandered, I tried to imagine what it would feel like if a member of each of the species represented by the tracks in the snow walked with me – shoulder to shoulder – to a grand, interspecies council organized to discuss how to stop the mine.

I came at last to the edge of an area that had been cleared for one of Lithium Americas’ exploratory water wells. The tracks disappeared before the clearing surrounding the well. The sagebrush seemed suspicious. The mud that squelched under my boots, upon determining the species my track belonged to, was eager to spit my feet out. I couldn’t blame the sagebrush or the mud. The last humans who had walked here were probably the same humans who bored a hole deep into the earth to learn how much water they could pump up from the earth and how many poisons they could pump down from the mine.

As I faced the sagebrush, they appeared to expect something from me. At first, I did not know what. Then, the harsh sounds of a heavy truck straining to haul a back-hoe up Highway 293, about a quarter-mile from where I stood, shattered the silence. The sage branches quivered. They trembled with fear.

It made me wonder: If sagebrush fear the trucks, do they know what Lithium Americas plans to do?

I began to narrate my premonitions. I saw a future where a line of trucks stretched for miles from Thacker Pass down Highway 293, east towards Orovada. The trucks screamed and screeched as they heaved back-hoes, excavators, tractors, and loads of the sulfuric acid needed to burn lithium from the earth. The air was thick with diesel exhaust. The ground shook as the machines thundered over the hills. Rabbits, mice, and rats scampered west out of the Pass through sagebrush roots only to find a new land already cleared for the hay fields in King’s Valley.

The activity so stressed a golden eagle mother that the eggshell surrounding her baby cracked prematurely because it was too thinly formed. Sage grouse awkwardly leapt from the valley floor towards the foothills, but they starved to death when they could not find enough habitat on the heights. Local coyotes – ever the survivors – howled at the horror of it all, tucked their tails, and, slunk over the ridgelines wondering when the new, pale humans would learn to listen to their trickster lessons.

The vision faded and I was left looking at the sagebrush that had gathered around me to listen to the terror I predicted. I second-guessed my decision to tell them. Perhaps it would have been best to let them enjoy the time they have left, I thought. Ignorance is bliss, after all.

As I faced those plants who I had just warned about the destruction that was coming, I wanted to run all the way back up the road to where my car was parked and drive as far away from Thacker Pass and the likelihood of her destruction as possible.

But, I didn’t run. I couldn’t run.

I don’t know if it was my own sense of honor or the mud sucking my feet into Thacker Pass that prevented me from fleeing. Finally, I asked aloud: “What do you need me to do?”

In response, my body turned wooden. My limbs became rigid. The hair on my arms and legs stood up like leaves drinking in the sun. I felt the machines through my roots first. My toes and fingers clinched at clumps of twitching soil. I felt vibrations through the bark that became my skin. Something big – bigger than anything I knew existed – was coming my way.

Then, I tasted the screams of my relatives on the breeze and through the root networks. They came as chemical messages – what scientists call “the release of volatile organic compounds” – that my sagebrush kin send through their communities when they are wounded. The screams were distant – just a trickle, at first. I started drinking different minerals to try to change my chemical composition to make myself displeasing to whoever was eating my family. But, then the shrieks saturated my surroundings. I frantically searched for new minerals, dug for deeper waters, and synthesized as much light as I could to create the strongest terpenoid compounds and volatile oils that I had used to protect myself before.

The chemical screams were being drowned out by the approaching, mechanical thunder.

I wished I was as fast as the pronghorn who sometimes browsed my branches. There was a moment when the thunder was strongest, the wind stopped, and the sun failed.

My legs cracked, my arms snapped, and the ripping began. My insides tore apart in a series of pops. I tried to grip the earth with the roots I had left but the dirt slipped through my grasp. With one final pop, everything went blank. There were no more minerals to taste. No sunlight to absorb. No water to drink. And, the chemical screams fell silent.

Back in my human body and soaking with sweat despite the cold temperature, I found myself clawing at my own guts as if they really had been torn out. When the wind mercifully blew this horror away, I found myself face-to-face again with the sagebrush.

“Stop them,” they said.

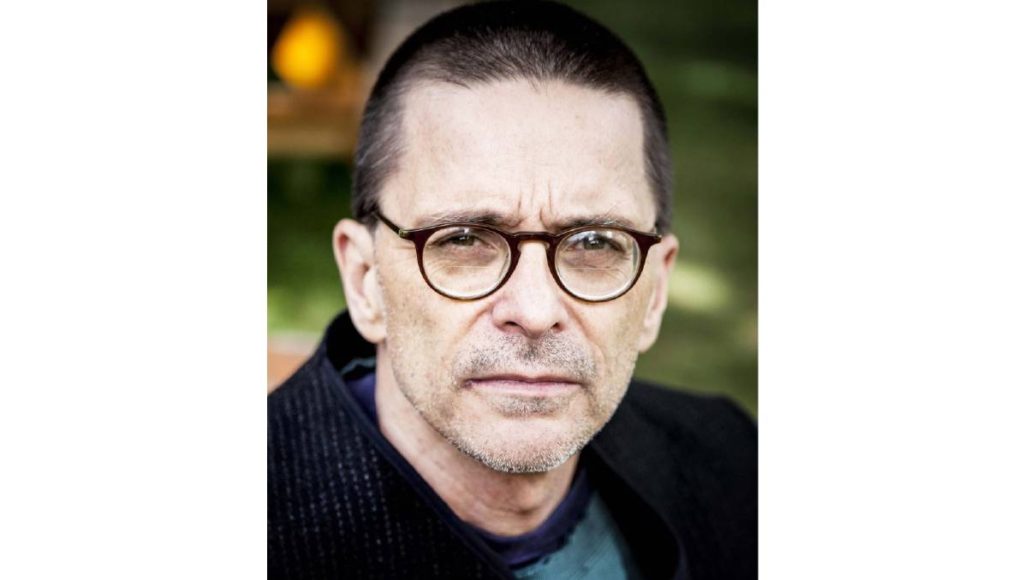

Photo by Max Wilbert

#ProtectThackerPass

For more on the issue:

by DGR News Service | Feb 19, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization

This is an excerpt from Garden Planet: The Present Phase Change of The Human Species by William H. Kotke. AuthorHouse, 2005. 146 pages. $11. Available from the Barn.

Fear is the fundamental of this cultural form.

The assertion is that the basic spiritual shift in consciousness was from a reality-view that saw the entire cosmos as alive and fecund to a reality-view that saw the earth as meaningless matter to be used to battle the scarcity of the world. On the one hand, the human is at home on the earth sharing space with other cooperating neighbor species in a reality of mystery and power. On the other hand, one lives in a world of accumulation where fear of scarcity and survival is prevalent.

On a more profound level, one has spiritually severed oneself from a reality of participation in a living, abundant world and created a reality of scarcity and violence in which one is a competitive isolate in a meaningless world.

When a tree sprouts in the forest it begins to assemble life.

The tree extends its roots and no doubt makes contact with the mycelium of a mushroom, extending its energy flow and living relationship. It raises leaves to the sun and connects with that living energy system. It connects with water in the air and soil; it connects with the diverse soil community. The tree unifies energies in its living systems.

The life of the earth functions in its balanced way because each being lives according to its particular nature. The decentralized power of all life resides in each being. In contrast, the pattern of empire culture is to centralize power over life and consequently the natural patterns disintegrate.

A golf course, for example, appears very neat and orderly. With its edged borders, well-watered grass, and trees, it represents the epitome of orderliness to the mind conditioned by the culture of civilization. In the reality of earth life, created and conditioned by cosmic forces, it is a gross disorder. Where once stood a life potentiating, balanced and perpetual, dynamic, climax ecosystem with its diverse circulating energies and manifold variety of beings, there are now a few varieties of designer plants kept alive by chemicals and artificial water supplies. A staff of maintenance people are kept busy battling the integrated life of the earth that attempts to rescue this wound by sending in the plants, animals, and other life forms that are naturally adapted to live in the area.

Human life in the culture of civilization is severed from its source in a similar way.

It is alienated from its source. This profoundly affects the psychology of the humans involved. On the one hand, we humans as forager/hunters stand on the earth. When we eat from the earth, we have a certain dignity and security. Each one of the tribe has the culturally given knowledge of how to walk out on the earth and find food and shelter. It is a direct and intimate relationship.

In the culture of empire, people are dependent on other people for their food and shelter. They do not get their sustenance from their intimate relationship with the earth but from their manipulation of other humans in some manner. They exist in a vast productive mechanism that sucks materials from the earth to build an artificial reality such as a shopping mall where humans manipulate each other in order to achieve the needs of their existence.

The integrated nature of the organic form of the whole world and the adaptation of each form within is demonstrated by their place in the balanced metabolism of the whole. There is an organism within organic life that does not practice this balance within the metabolism. It practices a linear growth plan. This organism is the cancer cell within biological life and it does accurately reflect an analogy with the culture of civilization.

The cancer cell breaks the cooperative and sharing relationship with its fellow cells and becomes “God” as it were. “I am not satisfied with what has been given with this body, I shall create a body of my own design.” Instead of remaining integrated and adapted to the body it is part of, the cancer cells create a body of their own design and use the host’s body as its energy feed. This unlimited growth system of the cancerous tumor body built by the cells begins to colonized the body, establishing new cancer tumor bodies, all functioning in a parasitic metabolism until the host body dies.

You can access the original article here.

by DGR News Service | Feb 18, 2021 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, The Problem: Civilization

This news article published by Survival International on January 27, 2021 explains how areas of protected land is likely to be opened up for use with devastating impacts for the survival of the indigenous people there.

Featured Image: Amazon Rainforest, Brazil

Senator Zequinha Marinho is pushing for the Ituna Itata area of rainforest, known to be the territory of uncontacted people, to be stripped of its protection and opened up to land grabbers and settlers.

The Ituna Itatá (“Smell of Fire”) indigenous territory in Brazil, home to uncontacted Indians, is under grave threat after it was revealed that a Brazilian Senator is plotting to open it up to settlers, loggers, ranchers and miners. Brazilian organization OPI has reported that Senator Zequinha Marinho – who has strong links to the mining and ranching lobby and is also a member of the controversial Assembly of God evangelical church – wrote to the President’s office demanding that part of the territory’s current protections be revoked.

The aim is eventually to open the entire area up.

Located in the Amazonian state of Pará, Ituna Itatá is only inhabited by uncontacted people and is already being heavily targeted and invaded by land-grabbers and loggers. Illegal logging is increasing there exponentially, and last year it was the most deforested indigenous territory in Brazil.

Another serious threat to the region is from the Canadian mining company Belo Sun who are planning to develop the country’s largest open-pit gold mine just a few miles away.

Yet the territory should have been mapped out and protected years ago – it was one of the conditions for the approval of the huge Belo Monte dam project nearby.

Please do get in touch with Survival International (see link above) if you would like to know more about how you can support their work.

by DGR News Service | Feb 17, 2021 | Male Supremacy, Male Violence, Pornography

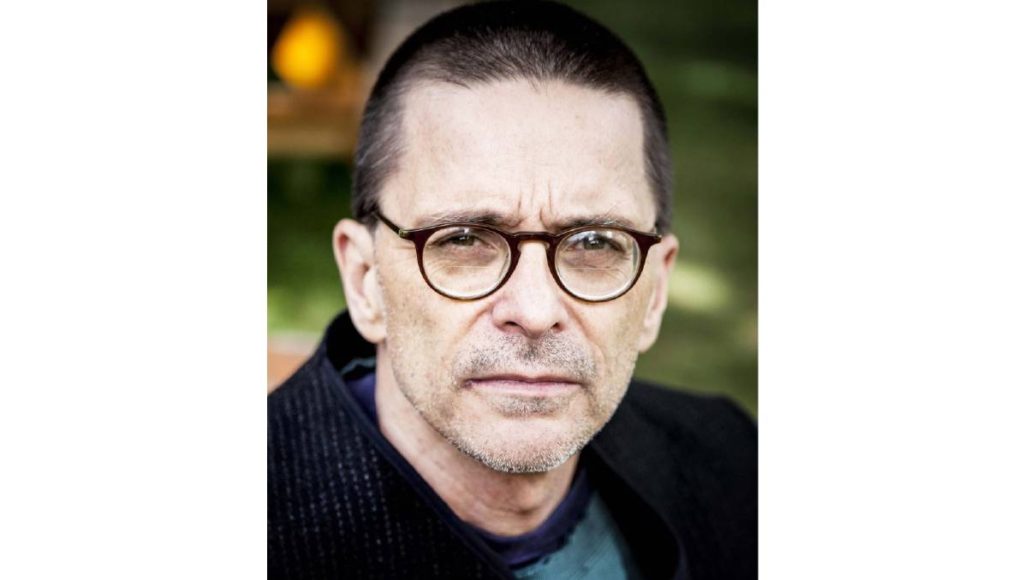

Robert Jensen (no relation to Derrick Jensen) is a very important and rare example of a man embracing radical feminism. Originally published in feminist current, you can read the original here!

When a European graduate student emailed to ask if I would participate in an assignment to “do an interview with one of my favourite authors,” I said yes. My books have not exactly been best-sellers, and so I was an easy target for anyone describing me as a “favourite author.”

But beyond my gratitude for someone noticing my writing, I was intrigued by the questions. And when I suggested we might publish the interview, I was even more intrigued by the student’s request to stay anonymous. She wrote that she was “extremely unsure of having my name on anything online. I know I am very strange (probably the strangest person I’ve ever met), but I’m not on Facebook or social media. I actually like the fact that googling my name gets no results about me. I don’t know if I’m ready yet to give up my blissful online non-existence. Is that crazy?”

It didn’t seem crazy to me, but I asked if she might want to describe herself for readers. Here is her self-description:

“I am a classically trained musician (more comfortable playing an instrument than talking in front of people), specializing in linguistics and interested in the meaning and the realities behind words and actions. Born and raised in a communist country, clandestinely listening to Radio Free Europe while growing up, having all civil liberties seriously infringed, yet being raised free by amazing parents (with the help of books and music) who knew how to help us find our identity independently of society’s impositions. I have always been profoundly enraged by any form of injustice or lie, and from a very young age I would routinely get in trouble for standing up for and defending my beliefs and people who were being abused in some way or another (something that has always been puzzling to adults and authority figures, since I am extremely shy and well behaved). I got myself almost expelled in high school for refusing to participate in an event which contradicted who I am. And I do not work on Sundays.

Seeing how the world keeps collapsing and becoming more insane, I began to think that maybe I am insane for wanting a better world than the one that’s become so normalized. Stumbling upon Robert Jensen’s books made me realize I am not the only ‘insane’ person in the world. It takes courage to pursue a path that others ignore or deny, to talk about things that others so politically correctly sweep under the rug, to want to face your fears and the pain that comes with admitting the truth, and to give a voice to the pain, fear, and humiliation of those dehumanized by our lack of humanity.”

Here is the interview, conducted over email, last month:

~~~

Who is Robert Jensen? How would you describe yourself?

Robert Jensen: I’m a simple boy from the prairie. That’s how I started describing myself when I found myself in so many places that I would have never imagined when I was growing up. I was born and raised in North Dakota with modest aspirations. I was a good student, in that well-behaved, diligent, and just slightly above average way that made teachers happy. I did what I was told and never caused trouble. I didn’t come from an intellectual or political background, and I wasn’t gifted. So, when I found myself with a Ph.D., teaching at a big university, publishing books, and politically active in feminism and the left — which involved a lot of traveling, including internationally for the first time in my life — it was all a bit hard to comprehend. I used to call a friend when I was on the road and ask, “How did a boy from Fargo, ND, end up here?” I continue to think that “I’m a simple boy from the prairie” is a pretty accurate description of me.

What was your childhood like? Were you a happy child? What are your best and worst memories from that time?

RJ: I am still searching for the words to use in public to describe my childhood. My family life was defined by the trauma of abuse and alcoholism. I spent my early years perpetually terrified and was pretty much alone in dealing with that terror. So, no, I was not a happy child. I don’t have a lot of clear memories of that time, which is one way the human mind deals with trauma, to repress conscious memories of it. I think one reason that a radical feminist critique of men’s violence and sexual exploitation resonated with me was that it provided a coherent framework to understand not only society but also my own experience. I came to see that what happened in my family was not an aberration from an otherwise healthy society but one predictable outcome of a very unhealthy society.

Which authors have been important in helping you understand that?

RJ: I gave a lecture once in which I identified the most important writers in my intellectual and political development: Andrea Dworkin (feminism), James Baldwin (critiques of white supremacy), Noam Chomsky (critiques of capitalism and imperialism), and Wes Jackson (ecological analysis). There are countless other writers who have been crucial in my development, but those are my anchors, the people who first opened up new ways of thinking about the world for me. They helped me understand not only specific issues they wrote about but how it all fits together, a coherent critique of domination.

Radical feminism is central in your writing. What is radical feminism?

RJ: Feminism is both an intellectual and a political enterprise — that is, it is an analysis and critique of patriarchy, and a movement to challenge the illegitimate authority that flows from patriarchy. Most feminist work focuses on men’s domination and exploitation of women, but feminism also should be a consistent rejection of the domination/subordination dynamic that exists in many other realms of life, most notably in white supremacy, capitalism, and imperialism. I think radical feminism accomplishes that most fully. Radical feminism identifies the centrality of men’s claim to own or control women’s reproductive power and women’s sexuality, whether through violence or cultural coercion. Radical feminism helped me understand how deeply patriarchy is woven into the fabric of everyday life and how central it is to the domination/subordination that defines the world. Here’s how I put it in a recent article:

“For thousands of years — longer than other systems of oppression have existed—men have claimed the right to own or control women. That does not mean patriarchy creates more suffering today than those other systems — indeed, there is so much suffering that trying to quantify it is impossible — but only that patriarchy has been part of human experience longer. Here is another way to say this: White supremacy has never existed without patriarchy. Capitalism has never existed without patriarchy. Imperialism has never existed without patriarchy.”

What is it like being a male radical feminist in a world dominated by the idea that “men rule,” standing up in front of men and telling them that they should stop being men?

RJ: My message isn’t that men should stop being men. A male human can’t stop being a male human, of course. But we can reject the concept of masculinity in patriarchy, which trains us to seek dominance. When people critique “toxic masculinity,” a popular phrase in the United States these days, I suggest that “masculinity in patriarchy” is more accurate. The most overtly abusive and toxic forms of masculinity should be eliminated, obviously, but so should the “benevolent sexism” that also is prevalent in patriarchy. My argument to men is simple: If we struggle to transcend masculinity in patriarchy, we can shift the obsessive focus on “how to be a man” to the more useful question of how we can be decent human beings.

What is your definition for “human being”? What about “woman,” and “man” (not as constructed by patriarchy)?

RJ: I would say that we all have to struggle to become fully human in societies that so often reward inhumanity. I don’t have a definition so much as a list of things that most of us want — a deep sense of connection to others that doesn’t undermine the exploration of our individuality; outlets for the creativity that is part of being human, which takes many different forms depending on the individual; a secure community that doesn’t demand that we suppress what makes each of us different. In other words, being human is balancing the need for commitment to a community in which we can feel safe and loved, and the equally important need for individual expression. I think that’s pretty much the same for women and men. But in patriarchy, all of that hardens into the categories of masculine (dominant) and feminine (subordinate). In that system, it’s hard for anyone to become fully human.

You speak of the advantages of being a “white man in a heterosexual relationship, holding a job that pays more than a living wage for work I enjoy, living in the United States.” What are the disadvantages of all that?

RJ: I don’t know that I would call it a disadvantage, but I think most of us who have unearned privilege and power — whether we acknowledge it or not — know we don’t deserve it, which generates in many of us a fear that whatever success we’ve had is a sham. And when we fail, the sense of entitlement leads us too often to blame that failure on others. But on the scale of troubles in this world, that doesn’t rate very high. There’s a reactionary argument in the United States that in an age of multiculturalism, somehow it is white men who are the real oppressed minority, which is just silly. My whole life I have had subtle advantages that came because the people who ran the world I lived and worked in typically looked like me and cut me breaks, often in ways I wasn’t even aware of. I have listened to a lot of mediocre white guys whine about how tough it is for them. My response is, “As a mediocre white guy myself, I can testify to how easy we have it.” When I say that I’m mediocre, I’m not being glib. Like anyone, I have various skills, but I am not exceptional in anything. I think by accepting that fact about myself, that I’m pretty average, I have been able to develop the skills I have to the fullest rather than constantly trying to prove that I’m exceptional. I used to tell students that the secret to my success was that I was mediocre, and I knew it, and so I could make the best of it. That makes it easy to be grateful for all the opportunities I’ve had.

Lately I have come across the term “ethical porn,” described as “ethical, stylish and elegant sexual adult entertainment” (“female and couple focused online porn”). Is there such a thing as pornography that is ethical? The descriptions on one of those sites state: “beautiful tasteful… very naughty photographic collections” which “show much more focus on the pleasure of passion and hot-blooded sex. The desire for sensual female arousal, with a balanced and more realistic approach to sexual gratification with more equal pleasure… porn for women that provided real meaningful and beautiful relatable sex.” Yet the whole idea, the action, and the actual techniques are exactly the same as “classic porn.” Isn’t pornography just pornography, anti-human, no matter how you do it?

RJ: We can start by recognizing that pornography produced without abusing women is better than pornography in which such abuse is routine. Pornography that doesn’t present women being degraded for men’s pleasure is better than the mainstream pornography that eroticizes men’s domination of women. But lots of questions remain, as you point out. Why does so much of the so-called ethical or feminist pornography look so similar to mainstream pornography? And, even more important, is it healthy to embrace a patriarchal culture’s obsession with getting sexual pleasure through the mediated objectification of others? In other words, one question is, “What is on the screen in pornography?” and the other is, “Why is the sexuality of so many people so focused on screens?” If through sexuality we seek not only pleasure but intimacy and connection to another person, why do we think explicit pictures will help? Do those images provide the kind of pleasure that we really want? For me, the answer is no. I don’t think graphic sexually explicit images would enhance the kind of connection my partner and I value. I realize other people come to other conclusions, but I think everyone would benefit from reflecting on what we lose when so much of life — including intimacy — is mediated, coming to us through a screen.

What are the most important qualities (virtues) of a human being? What are a person’s flaws/failings that can make you run away as far and fast as possible?

RJ: I think that when we see our own flaws in others, we are the most critical of them. So, I can’t stand people who come to judgment quickly without listening to another person long enough. In other words, I am acutely aware of how often I lack patience. The thing I value most in others, which is probably true for almost all of us, is the capacity for empathy. The older I get, the easier it has been to understand my own failings, and I hope that makes me more empathetic toward others.

What advice would you give children, especially boys, not just about masculinity and femininity but about life more generally today?

RJ: I would start by recognizing that what we do is usually more important than what we say. Adults can tell children what we believe, but kids watch us to see if we act in a way consistent with those statements. For example, I would suggest that kids experience the world directly as often as possible and be wary of letting screens — computers, video games, television — define their lives. That advice is meaningful only if I model the same behavior. It’s important to tell children not to be limited by patriarchal gender norms, but it’s even more important to avoid reinforcing those norms in everyday life.

What advice would you give young adults, or for that matter, any adult?

RJ: When I was teaching, I found myself repeating, over and over again, three things: “Both things are true;” “Reasonable people can disagree;” and “We’re all the same, and there’s a lot of individual variation in the human species.” The first is about recognizing complexity. In my media law class, for example, I would point out that an expansive conception of freedom of speech is essential to democracy, and at the same time it’s crucial that we punish some kinds of speech (libel, harassing speech in certain circumstances, threats) because speech can cause tangible harms that we want to prevent. Both things are true. The second recognizes that in assessing the complexity, we are bound to come to different conclusions and should work to understand why and not assume the other person is an idiot. The third is a reminder that we are one species and all pretty much the same, yet no two of us are exactly alike. None of those three observations are particularly deep; they’re really just truisms. But we need to be reminded of them often.

With all that has happened these past months — all those lives and livelihoods wasted to hate, racism, injustice, COVID-19, with the elections and the surrounding events — does it seem that people have learnt something from all this? Is there more empathy, more understanding, more humanity? Because from everything I see around the world, it looks like we are even more numb, asleep, and unaware, less caring, even more selfish and superficial than before.

RJ: Like always, there’s good news and bad news on that front. It’s not hard to find examples of people turning away from our shared humanity and seeking a sense of superiority and dominance, examples of greed intensifying in the face of so much deprivation. It’s also easy to find people doing exactly the opposite, taking risks to try to bring into existence a society in which empathy is the norm and resources are shared equitably. That’s just a reminder that human nature is variable and plastic — there’s a wide range of expressions of our nature, and individuals can change over time. But at this moment in the United States, it’s hard to be upbeat. Politicians routinely say two things that indicate how deeply in denial as a society we are about all this. One is, in response to the latest horror, “this is not who we are as a nation,” when it is of course a part of who we are as a nation, though some want to ignore that. The other is “there’s nothing we can’t accomplish when we work together,” which is just plain stupid. There are biophysical limits that no society can ignore indefinitely, though the modern consumer capitalist economy encourages us to ignore that reality. The ecological crises we face, including but not limited to rapid climate change, are a result of the species ignoring those limits, with the United States leading the way.

What does the future look like for our planet, for humanity? Is there any hope for us?

RJ: Let’s start with what’s fairly clear: There is no hope that a population of eight billion people with the current level of aggregate consumption today can continue indefinitely. It’s important to recognize that this consumption isn’t equally distributed, and that injustice has to be corrected. But we have to face the reality that high-energy/high-technology societies are unsustainable no matter how things are distributed. The end of the current economic and political systems will likely be in this century, maybe a lot sooner than we expect, and no one knows what will come after that. My summary of the future is “fewer and less.” There will be fewer people consuming a lot less energy and resources, and planning should focus on how to make such a future as humane as possible. Most people — even on the left or in the environmental movement — do not want to face that, at least in part because no one has a plan for how to get from where we are today to a sustainable human population with a sustainable level of consumption. But that’s the challenge. As a species, we likely will fail. But that doesn’t mean we stop trying to figure it out. We’re not going to save the world as we know it, but the intensity of human suffering and ecological destruction can be reduced.

Are the arts important for you in this struggle? Do you have a favourite musician(s)? Movies? Novels?

RJ: For a lot of people, the arts are important in coping with these realities. I am not very artistically inclined, either in talent or interests. I like to watch movies and read novels now and then, and I listen to music. But as I got older, I gravitated toward a focus on more straight-forward political and intellectual work. That said, I have two favourite singer/songwriters. One is John Gorka, whom I first heard decades ago, and I immediately fell in love with the stories in his songs. I own everything he has recorded. The second is Eliza Gilkyson. I heard one of her records in the mid-1980s and liked it but didn’t follow her career. In 2005, I met her at a political event in Austin, TX, where we both lived, and we got to be friends. I started listening to her CDs and was especially struck by the quality of her songwriting, as well as her voice. The friendship turned into a romantic relationship and we’re married now. It turned out that she and John were friends, and lately they have been teaching songwriting workshops together. I’m in the enviable position of knowing my two favourite musicians, both of whom have an incredible gift with words, of making the human experience — both the political and personal sides of life — come alive in songs.

Anything you would like to talk about, but people do not usually ask or do not want to hear.

RJ: In interviews, we tend to focus on what makes us look good. We tell a story that sounds coherent, but real life is messy. I like it when people ask me about mistakes I’ve made, stupid things I’ve done, ideas I once believed in that I now reject. There are lots of examples of that in my personal life, of course. But I’m thinking specifically of how long it took me to come to the critical analysis of the domination/subordination dynamic. In my mid-20s, I had a period of several years in which I was a harsh libertarian and a fan of the writing of Ayn Rand. At one point, I think I owned every book she had written. Looking back, I think I understand why. There’s a lot of attention, positive and negative, paid to Rand’s celebration of greed and wealth, but that was never my attraction to her books. I never wanted to be rich or find a justification for being greedy. I think she’s popular with lots of disaffected young people — the kind of person I was in my 20s — because she promises a life without emotional complexity. Rand constructs the perfect individual as a creature who chooses all relationships rationally, which describes no one who has ever lived, herself included. It’s just not the kind of animals we are. We are born into community and cannot make sense of ourselves as individuals outside of community. Her books offer the illusion that we can, by force of individual will, escape all the messiness of living with others. It’s interesting that Rand’s personal life was a train wreck, I suspect because she believed in those illusions and never really accepted the kind of creatures we human beings are. My assumption is that she was so scared of some aspects of the real world — perhaps the pain of loss and rejection — that she took refuge in the fantasy world she created. I think that’s a good reminder of how fear can drive us all to an irrational place if we let it. Anyway, when I started to understand that, I drifted away from Rand’s writing and started constructing a worldview that allowed me to face not only my own fears but also the collective fears of the culture, instead of running from them.

~~~

Robert Jensen is Emeritus Professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin and a founding board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center. He collaborates with the Ecosphere Studies program at The Land Institute in Salina, KS.

Jensen can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu. To join an email list to receive articles by Jensen, go to http://www.thirdcoastactivist.org/jensenupdates-info.html. Follow him on Twitter: @jensenrobertw

by DGR News Service | Feb 16, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, The Problem: Civilization

This article originally appeared on climateandcapitalism.

Editor’s note: The article shows very well how this culture has lost connection to landbases and food sources, evolving ever more “efficient” ways to exploit the planets resources.

by Ian Angus/Climate and Capitalism (February 3, 2021)

Fishing is as old as humanity itself. Indeed, it is older — paleontologists have found evidence that our ancestors Homo habilis and Homo erectus caught lake and river fish in east Africa a million years ago. Large shell deposits show that our Neanderthal cousins in what is now Portugal were eating shellfish over one hundred thousand years ago, as were Homo sapiens in South Africa. Island people have been fishing in the southwestern Pacific for at least thirty-five millennia.[1]

For most of our species’ existence, fish were caught to be eaten by the fishers themselves. “They may have traded dried or smoked fish to neighbors, but this trade was not commerce in any modern sense. People donated food to those who needed it, in the certain knowledge that the donors would someday need the same charity.”[2]

Fishing for sale rather than consumption developed along with the emergence of class-divided urban societies, about 5,000 years ago. Getting fish to towns and cities where people couldn’t catch it themselves required organized systems for catching, cleaning, preserving, transporting and marketing. This was particularly true in the Roman Empire, where serving fresh fish at meals was a status symbol for the rich, and fish preserved by salting was an essential source of protein for soldiers and the urban poor. In addition to boats, an extensive shore-based infrastructure was needed to provide fish for millions of citizens and slaves: “elaborate concrete vats and other remains of ancient fish-processing plants have been found all along the coasts of Sicily, North Africa, Spain, and even Brittany on the North Atlantic.”[3]

The first surviving account of fish depletion caused by overfishing was written in Rome, about 100 CE. The poet Juvenal described a feast at which the high-quality fish served to the wealthy host and important guests had to be imported from Corsica or Sicily, because

“… our waters are already Quite fished-out, totally exhausted by raging gluttony; The market-makers so continually raking the shallows With their nets, that the fry are never allowed to mature.

So the provinces stock our kitchens.”

Fish populations in rivers and coastal areas were also depleted by urban and agricultural pollution. At the same meal, Juvenal says that less-favored guests were served

“a fish from the Tiber, covered with grey-green blotches … fed from the flowing sewer.”[4]

When the Roman Empire collapsed in Europe after 500 CE, commercial fishing contracted sharply: it was no longer safe or profitable to transport food large distances for sale. Fish was still on the menu everywhere, but for several centuries, “inland and coastal (shoreline) fisheries were common but local everywhere in medieval Europe.”[5]

The first mass-produced food commodity

Beginning in the 11th century, increased political stability and renewed economic growth made possible what some historians call the “fish event horizon” — a rapid expansion of commercial fishing in the North and Baltic Seas. Fishers in Norway and Iceland had two great advantages: proximity to waters that were home to more fish than all European rivers combined, and climates that were ideal for air drying cod. Hanging gutted fish on open racks in cold winds for several months removed most of the water, leaving all the nutrients of fresh fish in hard sticks that could be eaten directly or soaked and cooked. The dried fish could be stored for years without spoiling.

“Stockfish, as wind-dried cod and ling were called in medieval times, was the first mass-produced food commodity: a stable, light, and eminently transportable source of protein. From about 1100, Norway exported commercial quantities of stockfish to the European continent. By 1350, stockfish had become Iceland’s staple export commodity. English merchants, among others, brought grain, salt, and wine to trade for stockfish, but Icelandic fishermen could not keep up with European demand. Thus, after 1400, the English developed their own migratory fishery at Iceland, carried on at seasonal fishing stations.”[6]

When Europe-wide trade reemerged, merchants found that air-dried cod from Norway and (later) salted herring from Holland commanded premium prices. Archaeological evidence from across western Europe shows “a dramatic shift from local freshwater fish to air-dried cod from Norway from the 11th century onwards.”[7] For centuries to come, preserved fish from northern waters “fed the European need for a relatively cheap, long-lasting and transportable fish food.”[8]

The market for ocean fish in the late middle ages was driven, at least in part, by declining stocks of freshwater fish, caused by expanded agriculture and the growth of towns and cities. Deforestation, erosion caused by intensive plowing, and a doubling or tripling of the urban population combined to dump masses of silt and pollutants into rivers across Europe, while thousands of new watermills, built to grind grain and cut lumber, blocked rivers and streams where migratory species spawned.[9] As a result, “even in wealthy Parisian households and prosperous Flemish monasteries, consumption of once-favored sturgeon, salmon, trout, and whitefish shrank to nothing by around 1500.”[10]

In The Ecological Rift, Foster, Clark and York show how capital’s irresistible drive to expand “sets off a series of rifts and shifts, whereby metabolic rifts are continually created and addressed — typically only after reaching crisis proportions — by shifting the type of rift generated…. [and subsequently] new crises spring up where old ones are supposedly cut down.”[11] This happened with fish in the late Middle Ages, when capitalist industries first formed, in Henry Heller’s apt phrase, “within the pores of feudalism.”[12] When intensive fishing and pollution undermined the natural processes and environments that had maintained freshwater fish populations for millennia, the fishing industry shifted geographically, moving to exploit different kinds of fish in different locations. As we will see in a future article, in modern times the fishing industry has employed a variety of metabolic shifts, with devastating impacts on ocean’s ecosystems.

The shift from freshwater to ocean fish required much greater fishing effort and investment. Catching enough cod and herring for continental markets required ocean fishers to travel further and stay at sea longer, and processing the fish onshore required more time, equipment and labor. By the 1200s, merchants from northern Germany were financing expanded fishing operations in Denmark and Norway, providing advance payments, salt and other necessities.[13] Over time, outside capital investment funded ever-larger fishing operations.

“[In the 1200s] more than five hundred English, Flemish, and French vessels gathered off Great Yarmouth to supply unnumbered English and Flemish needs, while Paris had more than thirty million salt herring annually barged up the Seine and another twelve million plus were shipped to Gascony. At the same time along the southwestern coast of Danish Scania each year for a century and more, five to seven thousand small boats caught more than a hundred million fish and the merchants from northern Germany who ran the industry shipped 10,000 to 25,000 tonnes of product.”[14]

Capitalist fishing in the Low Countries

In the late 1500s, popular rebellions in the Low Countries triggered the world’s first bourgeois revolution, founding what Marx called a “model capitalist nation.”[15] In volume 3 of Capital, he identified fishing as key factor in Holland’s economic development.[16]

The area that now comprises the Netherlands and Belgium had been part of the Spain-based Hapsburg empire, a regime that rivalled Russia’s Tsars in reactionary hostility to any form of economic or political change.[17] The Dutch Revolt, as Marxist historian Pepijn Brandon writes, overthrew Hapsburg rule in the northern provinces and “left the state firmly under the control of the merchant-industrialists … [and] liberated one of Europe’s most developed regions from the constraints of an empire in which trade and industry were always subordinated to royal interest.” The new republic “became Europe’s dominant centre of capital accumulation.”[18]

An important factor in the rise of the Dutch merchant-industrialist class, scarcely mentioned in many accounts, was the absolute dominance of the Dutch fishing industry in the North Sea.

For most of the late middle ages, Dutch fishers had to work close to shore, because their principal catch was herring, a fatty fish that spoils in a few hours unless it is quickly preserved. Catches were limited by the need to return to shore, where the fish could be gutted and preserved by soaking in barrels of brine.

In about 1400, Dutch and Flemish fishers invented gibbing, a technique of rapidly gutting and salting herring. In 1415, another invention took full advantage of that technique — a Haringbuys (herring buss), was a large, broad-bottomed ship designed not only for high-volume fishing, but also with sufficient deck space for gibbing a full day’s catch and storage capacity for up to 60 tonnes of salted fish in barrels. A crew of 12 to 14 men could work at sea for months in what was, as environmental historian John Richard writes, “essentially a floating factory.”[19]

Every year, hundreds of herring busses sailed from Dutch ports to the far north of Scotland and then followed the vast shoals of herring that annually migrated southward in the North Sea, east of England, using mile-long driftnets. Often the fleet was supported by smaller boats that regularly replenished their supply of food, barrels and salt, and took full barrels back to port.

The floating factories gave Low Country shipowners a huge advantage over their English and French competitors in the North Sea. They could stay at sea longer, travel farther, catch more fish, and deliver a commodity that needed little on-shore processing. For the next 300 years, the Dutch North Sea fishery was “the single most closely managed and technologically advanced fishery of the world.” In most years, the Dutch fleet captured 20,000 to 50,000 tonnes of fish in the North Sea, more than all other North Sea fishers combined. In one exceptional year, 1602, the Dutch fishers brought in 79,000 tonnes of fish.[20]

As economic historians Jan de Vries and Ad van der Woude point out, the economic impact of what was called the “great fishery” extended beyond the revenues derived directly from selling fish.

“This sector not only employed many workers but possessed strong forward and backward linkages to shipbuilding, ropeworks, net and sail makers, the timber trade and sawing mills, ships provisioning, salt refining, cooperage and packing, smoking houses, and long-distance trade and shipping. It is not altogether surprising that jealous foreigners saw the fisheries as the secret weapon of Dutch merchants and shipowners.”[21]

Building and equipping herring busses required more capital than the small boats used by traditional coastal fishers. De Vries and van der Woude describe the industry’s evolution from early partnerships to truly capitalist organizations.

“In its early stages, the ownership of the herring busses was in the hands of partnerships, the partenrederij prevalent also in ocean shipping, which usually included as partners the skippers of the vessels. Even the fishermen sometimes invested in the partnership, typically by supplying a portion of the nets, which their wives and children, or they themselves during the off-season, had made. However, already in the fifteenth century, many fishermen worked for wages … and over time wage labor so grew in importance that first the fishermen and later even the skipper disappeared as participants in the partnerships, leaving a partenrederij composed primarily of urban investors. In the mid-sixteenth century, when the herring buss fleet of Holland alone already numbered some 400 vessels and other economic activities were yet of a rather modest scope, these partenrederijen must have formed one of Holland’s most important fields of investment.”[22]

The success of Dutch fishing gave an impetus to a substantial shipbuilding industry. As historian Richard Unger has documented, in the 1400s ships were built one at a time by independent shipwrights and their apprentices, but by 1600 Dutch shipbuilding was concentrated in a few large operations, and “the industry shifted from a medieval handicraft to something along the lines of modern factory organization.” Journeymen were paid daily wages at rates negotiated with local guilds, and were required to work fixed hours. The industry produced between 300 and 400 ships a year, each taking six or more months to complete. Dutch shipbuilders were widely seen as the best in Europe, so a considerable part of the industry’s revenue came from ships that were commissioned by merchants from other countries. The capitalist owners of Dutch shipyards were “among the wealthiest of businessmen in a country of wealthy men.”[23]

In 1578, Adriaen Coenan. a Dutch businessman who had spent his life in the fishing industry. described herring as Holland’s “golden mountain.”[24]

In 1662, Pieter de la Court, a wealthy businessman and strong supporter of the republic, wrote a widely read and translated book — Interest van Holland (Holland’s True Interest) — to explain the Dutch Republic’s economic success. He particularly stressed the importance of fishing, claiming that it generated “ten times more profit” each year than the Dutch East India Company’s state-enforced monopoly. Fishing was economically important not just on its own, but for the impetus it gave to related industries. “More than the one half of our trading would decay, in case the trade of fish were destroyed.”

He identified fisheries, manufacturing, wholesale trading (traffick), and freight-shipping as “the four main pillars by which the welfare of the commonalty is supported, and on which the prosperity of all others depends.”[25]

Writing two centuries later with the benefit of hindsight, Karl Marx’s shortlist of the most important drivers of early Dutch capitalism was different — he identified “the predominant role of the basis laid by fishing, manufactures and agriculture for Holland’s development” — but he too saw the fishing industry as a major factor.[26] Modern research confirms that intensive fishing for profit played a critical role in the birth and growth of Dutch capitalism.

The revolution that the Dutch fishing industry began in the North Sea in the fifteenth century — the conversion of immense quantities of ocean life into commodities for sale across Europe — did not stop there. Part two of this article will examine the even greater impact of a capitalist fishery on the other side of the Atlantic.

This article is part of a continuing project on metabolic rifts. Your constructive comments, and corrections will help me get it right. —IA

References

- Brian Fagan, Fishing: How the Sea Fed Civilization (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017) provides an excellent account of current knowledge about pre-capitalist fishing.

- Fagan, Fishing, 18.

- Geoffrey Kron. “Ancient Fishing and Fish Farming,” in Gordon L. Campbell, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life (Oxford University Press, 2014).

- Juvenal: The Satires, translated by A. S. Kline, 2011. Juvenal’s social criticism frequently exaggerated for comic effect, so his account may not have been literally true.

- Richard Hoffmann, “A Brief History of Aquatic Resource Use in Medieval Europe,” Helgoland Marine Research 59, no. 1 (April 2005), 23; Richard Hoffmann, “Medieval Fishing,” in Working With Water in Medieval Europe, ed. Paolo Squatriti (Boston: Brill, 2000), 331. Fish was on the medieval menu not only for nutrition, but because the Church banned meat (but allowed fish) on over 130 days a year — every Friday, every day Advent and Lent, and on a variety of other holy days.

- Peter E. Pope, Fish into Wine: The Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 11.

- Tony J. Pitcher and Mimi E. Lam, “Fish Commoditization and the Historical Origins of Catching Fish for Profit,” Maritime Studies 14, no. 2

- Hoffman, “A Brief History of Aquatic Resource Use in Medieval Europe,” 28.

- At the end of the ninth century, there were just 200 watermills in all of England. Two hundred years later, the census known as the Domesday Book recorded 5,624. Richard Hoffmann, “Economic Development and Aquatic Ecosystems in Medieval Europe,” American Historical Review 101, no. 3 (June 1996): 640.

- Hoffmann, “Economic Development,” 650.

- John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Richard York, The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010), 78.

- Henry Heller, The Birth of Capitalism: A 21st Century Perspective (London: Pluto Press, 2011), 104.

- Hoffmann, “Medieval Fishing,” 342-3.

- Richard Hoffmann, “Frontier Foods for Late Medieval Consumers: Culture, Economy, Ecology,” Environment and History 7, no. 2 (May 2001): 148

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, (London: Penguin Books, 1976), 916. For an overview of the Dutch revolution, see Pepijn Brandon, “The Dutch Revolt: A Social Analysis,” International Socialism, October 2007.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 3, (London: Penguin Books, 1981), 450n.

- “No other major Absolutist State in Western Europe was to be so finally noble in character, or so inimical to bourgeois development.” Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State (London: Verso, 1979), 61.

- Pepijn Brandon, “Marxism and the ‘Dutch Miracle’: The Dutch Republic and the Transition-Debate,” Historical Materialism 19, no. 3 (January 2011): 127-128.

- John F. Richards, The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 51. In the off-season, a herring buss could carry other cargoes, so they were more profitable to operate than other fishing boats.

- Poul Holm et al., “The North Atlantic Fish Revolution (ca. AD 1500),” Quaternary Research, 2019, 4. The Dutch North Sea catch was small by modern standards, but far greater than any other European fishery at the time.

- Jan de Vries and Ad van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, (Cambridge University Press, 1997), 235.

- de Vries and van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 244.

- Richard W. Unger, “Technology and Industrial Organization: Dutch Shipbuilding to 1800,” Business History 17, no. 1 (1975).

- Adriaen Coenan, in Visboek (Fishbook), quoted in Louis Sicking and Darlene Abreu-Ferreira, eds., Beyond the Catch: Fisheries of the North Atlantic, the North Sea and the Baltic, 900-1850 (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 209.

- Pieter De La Court, The True Interest and Political Maxims, of the Republic of Holland (London: John Campbell, 1746), 160, 31, 94.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 3, (London: Penguin Books, 1981), 450n.