by DGR News Service | Sep 12, 2019 | Culture of Resistance, Strategy & Analysis, The Solution: Resistance

Editor’s note: this article references Spiral Theory, which is a strategic approach adopted by some revolutionary movements in which violent acts are undertaken against state targets with the intention of provoking an indiscriminate repressive response against an associated social group that is relatively uninvolved with the action itself. This repressive response is sought for its ability to radicalize a population that is currently apolitical or unsupportive of violent revolution.

by Liam Campbell

Cuba’s revolution is a testament to how powerful a small number of dedicated, intelligent, and organised people can be. Despite seemingly impossible odds, a few dozen people managed to overthrow a despotic government which was supported by the might of the United States government. Many figures played key roles in Cuba’s Movimiento 26 de Julio (July 26th Movement), but Fidel Castro was unquestionably the central leader and architect. How did a boy raised in a rural setting, by a mostly illiterate family, manage to outsmart and outmanoeuvre a sophisticated and well connected government? Let’s explore this question.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Cuba was essentially a corporatocracy owned by a handful of American monopolies. It was a playground for wealthy Americans, only a short distance from Florida, where the priveleged could consume voraciously. All of this glitz and glamour was supported by a dark underbelly of corruption, poverty, and the near slavery conditions of Cuba’s working classes. Castro famously wrote that it was a nation were teachers had no classrooms and where peasants had no land, but where imperialists were able to siphon millions of dollars of public funds into private coffers.

It was in this climate of extreme corruption and inequity that Castro first became involved in politics. His Mother, who could not read or write, insisted that he should have the best education; despite being thrown out of his first boarding school for unruly behaviour, Castro was eventually invited to attend Cuba’s most prestigious university, in Havana. Crime and violence were commonplace, even in the universities, and people often commented that “if you are to be politically effective, you need to be willing to wield a gun.” It was in this extreme climate that Castro began organising marches and other protest actions, primarily against corruption. For protection, Castro pragmatically joined a gang that supported his political activism. Havana had become a heavily disenfranchised city, having seen successive, failed independence movements; leaders of these movements were either bought out or killed. Few people had faith in the institutions of the government and there was a growing sentiment that revolution would be necessary.

Upon graduating, Castro opened a small law firm in Havana, which meagerly supported his true passion: political organising. He had become a talented orator and was an increasingly recognised figure among the political circles of the city. He eventually decided to run for political office as a member of the Orthodox Party, which was influenced by Jesuit Nationalists from the Spanish Civil War. Castro ran on an anti-corruption platform and openly opposed American imperialism and influence over Cuba. Before the start of the election, on March 10th, General Batista led a coup and took over the government as dictator; this coup destroyed any remaining faith in political processes and was deeply unpopular among the public. In this changing climate, people sought out audacious leaders rather than run-of-the-mill politicians, and Castro prepared himself for this role.

The period after Batista’s coup was difficult for many Cubans, including Castro who began to experience extreme economic hardship. It was at his lowest point that Castro decided “I have to deliver a blow, I have to spark a revolution.” He organised a group of fellow revolutionaries and planned an audacious assault on the Mancada Army Barracks. It was understood that their odds of success were low, but they believed that “even if it fails, it will be heroic and have symbolic value.” In total, nearly 80 revolutionaries agreed to the assault — it resulted in a massacre.

In the end, 8 revolutionaries were killed outright, 12 were wounded, and 60 were captured, tortured, and eventually executed. Batista made a critical mistake by organising mass retaliations and engaging in a national crackdown, which was deeply unpopular and turned Castro and the other revolutionaries into public heroes; they had dared to defy a violent, unpopular, authoritarian regime. This was a very famous example of Spiral Theory working in favour of a revolutionary movement, and it was a mistake that Batista would repeat throughout his brief career. After Castro was captured, he was saved from execution by an Archbishop who intervened on his behalf, and he was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Castro used his trial as a public platform to make impassioned calls for revolution, it was during this spectacle that he made the famous remark “condemn me, it does not matter, history will absolve me.”

While in prison, Castro was strongly influenced by the writings of Marxist authors who proposed that the workers should own the fruits of production, and that one state should be ruled by one party. Castro claimed that “prison [was] a terrific school.” He wrote his seminal book History Will Asbolve Me, which was snuck out, a few pages at a time, by his wife. This book had a profound impact on Cuban readers because it spoke of unemployment, empty schools for lack of teachers, farmers who did not own the land, and the extreme inequity between those who worked and those who ruled; it was a book about social justice. His writing fit within norms of 1950s Cuba, which was leaning toward centre left.

After 22 months of confinement, Castro was released from prison after Batista issued amnesty orders — I speculate that he did so in order to inhibit Castro from continuing his state-sponsored writing. Castro was only 29 years old, but he had become a recnogised political figure in Cuba. After release, he began the 26th of July Movement, in memory of the Macada Barracks assault. He traveled abroad, organised likeminded revolutionaries, and trained extensively. When his rebels were ready, in 1956, he set sail on a 65′ yatch for Cuba. In total, there were 82 people aboard and they were prepared to die for Cuban independence. They were spotted before landing and were met with overwhelming military force at the beach. Most of were killed, but Castro and 17 others survived the ambush and fled into the mountains to organise a guerilla insurgency. The struggle was wildly asymetrical, so they focused on building strong relationships with local communities and developing an international reputation. Within 3 months they reappeared on the front page of the New York Times in a series of 3 articles written by Herbert Matthew; this started the legend of Fidel Castro. Castro and his rebels began developing regional trust by providing aid to peasant communities throughout the mountains. They focused on healthcare, food, and security. These efforts were successful and support grew rapidly among the disenfranchised and neglected communities of the region.

The story was different in Cuba’s cities. Batista began brutal crackdowns on anyone who was thought to be affiliated with anti-government activism, including members of the July 26th Movement. A group called the Student Revolutionary Directorate stormed the Presidential Palace in 1957 in an attempt to assassinate Batista, but their leader was gunned down and they failed in the attempt. Batista launched a series of extreme crackdowns, which accidentally targeted innocent people and resulted in widespread backlash, another example of Spiral Theory in action. In Santiago, the July 26th underground faction engaged in fierce urban warfare and bore the brunt of repression; their leader was eventually ambushed and killed. These martyrs became the focus of peaceful public protests and Batista’s harsh, sweeping reprisals generated increasingly intense public backlash.

It was around this time that political forces in Cuba recognised that Castro was the leading contender for national leadership, and they traveled into the Sierra Maestro mountains to meet him. Both opposition leaders and members of the July 26th Movement formed an assembly in the mountains and they produced The Manifesto of the Sierra Maestro, which worked out the details of a future coalition government. The document called for a democratic republic, free elections, and returning to the constitution of 1940. Castro signed the document but realised early on that he had the unequivocal support of both his rebels and the people, and so he didn’t need politics anymore. According to his worldview, the purpose of revolution is to subvert society, to take people from the bottom, and everyone else, and create something entirely new.

In 1958, Batista decided to engage in all-out warfare again Castro by deploying 10,000 troops against Castro’s 300 rebels. Within a month, they had fully encircled the revolutionaries, but they had been drawn deep into the territory of Castro’s loyalists. Although they were profoundly outnumbered and outgunned, Castro issued a simple order: “hit them where they least expect it.” The revolutionaries engaged in hit-and-run tactics, used their agility, and leveraged their community support to devastate Batista’s large, but wavering, army. In response, Batista ordered inreasingly brutal reprisals against both revolutionaries and the communities of the Sierra Maestro mountains; these horrific actions were documented and resulted in the United States withdrawing military support in order to avoid international scrutiny. This was the beginning of the end for Batista.

In August of 1958, Castro’s rebels left the mountains and fanned out across Cuba, finally going on the offensive. They recognised that Batista had lost international support, was despised by the public, and that his troops were wavering after demoralising attacks. This offensive involved extensive sabotage and culminated in Che Guevara derailing an armoured train and taking Santa Clara. This was the last straw and Batista’s forces began to break ranks. In the beginning of 1959, Batista fled Cuba with his friends and a stolen fortune of over $100 million. On January 2nd, Fidel Castro and his army staged a 200 mile victory march to Havana, where he spoke at every stop. His use of media energised the public and created a sense of victory, unity, and possibility. The rest is history.

This is how a tiny number of people overthrew a repressive government which was backed by the might of the American empire.

by DGR News Service | Aug 23, 2019 | Direct Action, People of Color & Anti-racism, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

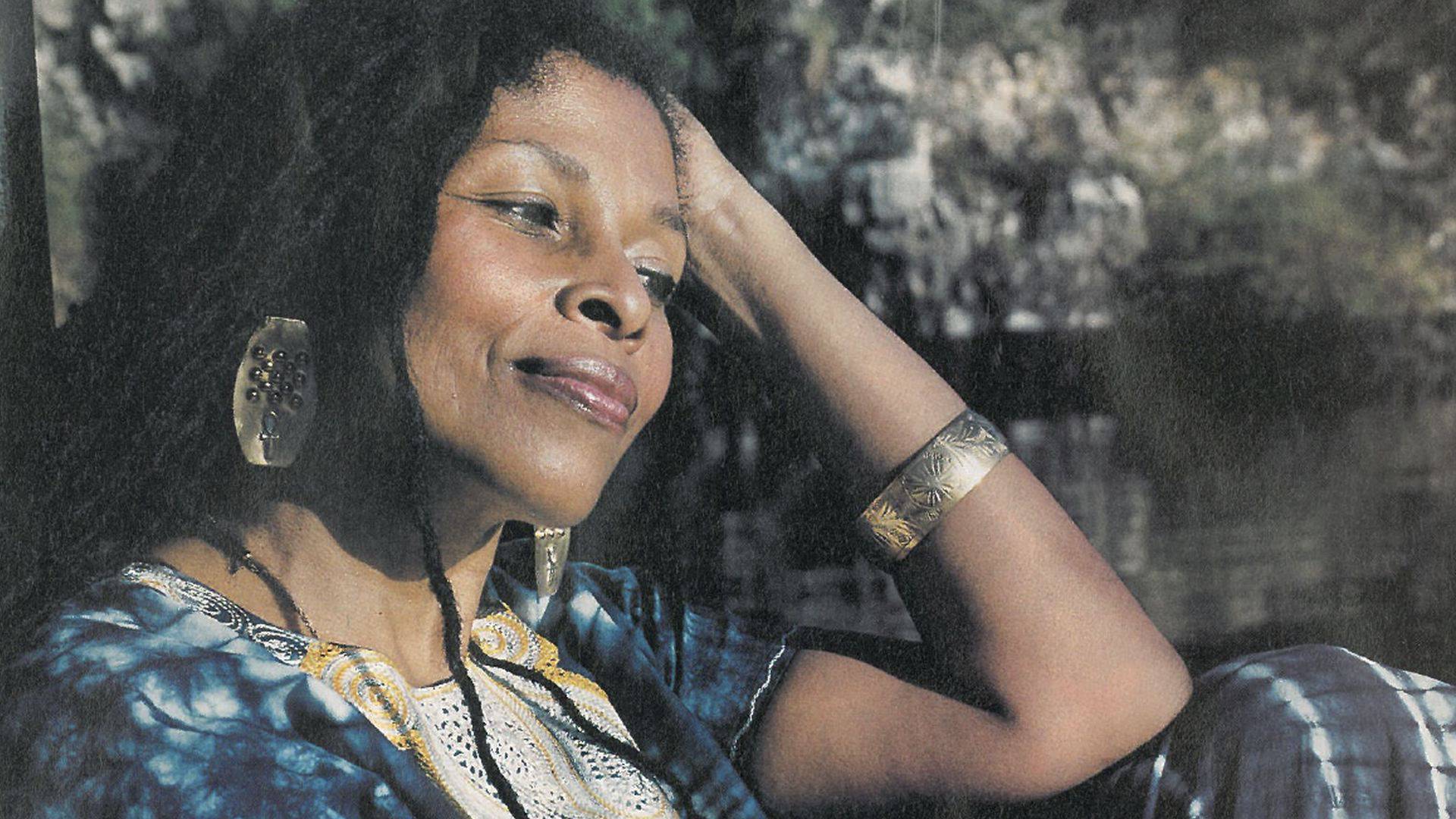

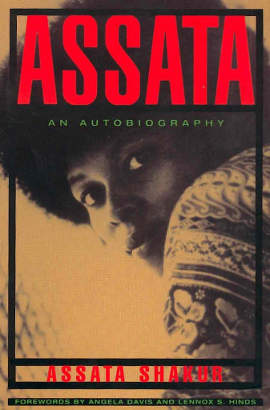

By Norris Thomlinson / Originally published on DGR Hawaii / Featured image by Angela Davis, CC BY 4.0

Once you understand something about the history of a people, their heroes, their hardships and their sacrifices, it’s easier to struggle with them, to support their struggle. For a lot of people in this country, people who live in other places have no faces.”

–Assata Shakur

A World Apart

I grew up in the same country as Assata Shakur, but as a poor black woman, her autobiography reveals an experience a world apart from my own middle class, white male upbringing. She ably captures these differences in a series of anecdotes revealing that she did in fact grow up in a different country: “amerika”, while I enjoyed the facades of democracy, peace, and justice in America. I’ve been aware of the shocking statistics of incarceration rates of people of color, disproportionate distribution of wealth, heartbreaking inequity in education systems, increased exposure to toxins, decreased lifespans, and on and on. But I haven’t read much by black authors about their personal experiences navigating these systems of oppression and injustice. Shakur’s autobiography is surprisingly easy to read and even enjoyable, despite and because of its humorous tragedy, and makes an excellent introduction to a different reality for those of us born into white and/or male privilege.

Beyond her personal insights into the impacts of class, race, and gender, Shakur shares her astute political analysis, and draws a logical line from her childhood acceptance of the systems of America to her adult revolutionary struggle against amerika. Based on voracious reading, observation of the world around her, and careful thinking, she developed a radical analysis of structures of power and how to fight them. She understands that “What we are taught in the public school system is usually inaccurate, disorted, and packed full of outright lies” and that “Belief in these myths can cause us to make serious mistakes in analyzing our current situation and in planning future action.” She links the “interventions” and invasions of the US abroad to its theft of indigenous land and oppression of people of color at home.

Shakur knows none of this is an accident, fixable by asking those in power to change their ways. The people need to fight back, using violence if necessary:

“…the police in the Black communities were nothing but a foreign, occupying army, beating, torturing, and murdering people at whim and without restraint. I despise violence, but i despise it even more when it’s one-sided and used to oppress and repress poor people.”

Horizontal Hostility

Shakur explains that while those in power use schooling, media, the police, and COINTELPRO to divide and conquer those who might oppose them, the solution is simple (though not necessarily easy):

“The first thing the enemy tries to do is isolate revolutionaries from the masses of people, making us horrible and hideous monsters so that our people will hate us.”

“It’s got to be one of the most basic principles of living: always decide who your enemies are for yourself, and never let your enemies choose your enemies for you.”

“Some of the laws of revolution are so simple they seem impossible. People think that in order for something to work, it has to be complicated, but a lot of times the opposite is true. We usually reach success by putting the simple truths that we know into practice. The basis of any struggle is people coming together to fight against a common enemy.”

“Arrogance was one of the key factors that kept the white left so factionalized. I felt that instead of fighting together against a common enemy, they wasted time quarreling with each other about who had the right line.”

Parallels with Deep Green Resistance

It seems many of Shakur’s insights directly informed the Deep Green Resistance book, or the authors came to the same conclusions after studying similar history. For example, Shakur clearly states the need for a firewall between an aboveground and a belowground:

“An aboveground political organization can’t wage guerrilla war anymore than an underground army can do aboveground political work. Although the two must work together, they must have completely separate structures, and any links between the two must remain secret.”

She sees one of the main flaws of the Black Panther Party as having mixed aboveground political work with a militancy more appropriate for a belowground, especially in attempting to defend their offices at all costs against police raids. While understandable as symbolic of their pride and a willingness to fight for what was theirs, the simple reality was that the Panthers weren’t ready to go up against the military might of the state, and it was suicide to attempt to hold this symbolic territory. In asymmetric warfare, you must give way where the enemy is strong, and strike where the enemy is weak.

Perhaps most importantly, Shakur emphasizes several times the necessity of discipline and of careful, logical, long-term planning. She recounts an embarassing situation where she and some friends smoke marijuana in a public park while carrying radical literature, risking beatings or arrest by relinquishing full control of their faculties. After another revolutionary group helps them out of their precarious situation, a dazed Shakur resolves to take the struggle more seriously. This contrasts sharply with the drug- and sex-fueled Weathermen and their contemporaneous white radicals, whose self-indulgence in machismo and rebelliousness resulted in a strategy of instigating fistfights and rioting in the streets.

It reassures me that so many of Shakur’s hard-won lessons are foundational to Deep Green Resistance, as it reinforces my confidence in DGR as a well-researched analysis of historical movements and a solid guide to proceeding from here:

“There were sisters and brothers who had been so victimized by amerika that they were willing to fight to the death against their oppressors. They were intelligient, courageous and dedicated, willing to make any sacrifice. But we were to find out quickly that courage and dedication were not enough. To win any struggle for liberation, you have to have the way as well as the will, an overall ideology and strategy that stem from a scientific analysis of history and present conditions.

[…]

Every group fighting for freedom is bound to make mistakes, but unless you study the common, fundamental laws of armed revolutionary struggle you are bound to make unnecessary mistakes. Revolutionary war is protracted warfare. It is impossible for us to win quickly. […] One of the hardest lessons we had to learn is that revolutionary struggle is scientific rather than emotional. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t feel anything, but decisions can’t be based on love or on anger. They have to be based on the objective conditions and on what is the rational, unemotional thing to do.”

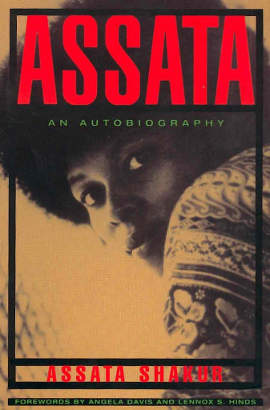

Read This Book

If you want to better understand racism, read this book. If you enjoy a well-told story of a unique and fascinating life, read this book. If you’re interested in historical revolutionary movements, read this book. If you’re interested in a modern revolutionary movement, read this book, read Deep Green Resistance, and let’s start putting the theory into practice.

“It crosses my mind: i want to win. i don’t want to rebel, i want to win.”

–Assata Shakur

by DGR News Service | Jul 23, 2019 | Direct Action, Education, Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: this article contains extensive excerpts from the Irish Republican Army’s Green Book, one of their key training documents during their 20th-century struggle against British occupation.

Written by Liam Campbell

“Don’t be seen in public marches, demonstrations or protests. Don’t be seen in the company of known Republicans, don’t frequent known Republican houses. Your prime duty is to remain unknown to the enemy forces and the public at large.”

Like all successful underground organisations, the Irish Republican Army maintained a strict firewall between their aboveground and underground movements, this ensured that publicly identifiable individuals could not be pressured into revealing underground militants, providing a certain level of safety for both groups. The Irish Republican Army also emphasized the importance of abstaining from alcohol or other drugs, which they identified as the single greatest threat to any guerilla organisation.

“Many in the past have joined the Army out of romantic notions, or sheer adventure, but when captured and jailed they had after-thoughts about their allegiance to the Army. They realised at too late a stage that they had no real interest in being volunteers. This causes splits and dissension inside prisons and divided families and neighbours outside.”

When recruiting, the Irish Republican Army recognised that successful underground members had certain characteristics; they were intelligent, reliable, and they were capable of giving their total allegiance to the cause. These characteristics ensured that they would consistently obey often difficult orders from the chain of command, regardless of the personal cost, and despite any personal issues they may have with their superior officers. Certain qualities could disqualify a person as a candidate: emotionalism, sensationalism, and adventurism were among them.

“The enemy, generally speaking, are all those opposed to our short-term or long-term objectives. But having said that, we must realise that all our enemies are not the same and therefore there is no common cure for their enmity. The conclusion then is that we must categorise and then suggest cures for each category. Some examples: We have enemies through ignorance, through our own fault or default and of course the main enemy is the establishment.”

One of the most essential features of the Green Book was the precision with which it defined enemies. You cannot wage a successful war if your targets are poorly defined. The Irish Republican Army identified three categories of enemy:

Enemies through ignorance are those individuals who can be cured through education. Tactics included marches, demonstrations, wall slogans, press statements, publications, and person-to-person communication. The Green Book stressed that self education was essential, which included ideological understanding and also tactical knowledge about how to organise large groups of people and how to successfully execute different actions.

Enemies through our own fault are the ones created by the Irish Republican Army’s actions, which includes personal conduct and the collective conduct of the movement. These enemies vary greatly. The elderly woman whose door was pulled off its hinges by an IRA member evading capture who doesn’t receive an immediate apology and recompense, the family and friends of an informer who has been punished without their being notified of the reason, and also the collateral victims of violence.

Members of the establishment who consciously take actions to maintain the status quo in politics, media, policing, and business. Although some of these enemies are clearly identifiable, most of them operate with various degrees of anonymity as bureaucratic cogs in a vast machine of oppression; this means that one of the greatest challenges is accurately identifying establishment members. Surprisingly, execution is not always the best way to make a member of the establishment ineffective, often it is better to expose them as liars, hypocrites, collaborators, or subjects of public ridicule.

“Many figures of speech have been used to describe Guerrilla Warfare, one of the most apt being ‘The War of the Flea’ which conjured up the image of a flea harrying a creature of by comparison elephantine size into fleeing (forgive the pun). Thus it is with a Guerrilla Army such as the I.R.A. which employs hit and run tactics against the Brits while at the same time striking at the soft economic underbelly of the enemy, not with the hope of physically driving them into the sea but nevertheless expecting to effect their withdrawal by an effective campaign of continuing harassment contained in a fivefold guerrilla strategy.”

The Irish Republican Army’s strategy included a war of attrition, the destruction of high-value assets, to make large regions ungovernable, to sustain a propaganda campaign, and to protect the movement against criminals, collaborators, and informers. The Green Book emphasized that volunteers need to achieve more than just killing enemy personnel, they must also create and maintain support systems that would not only carry the movement through the war, but would also facilitate a smooth transition after military victory had been achieved.

“Most volunteers are arrested on or as a result of a military operation. This causes an initial shock resulting in tension and anxiety. All volunteers feel that they have failed, resulting in a deep sense of disappointment. The police are aware of this feeling of disappointment and act upon this weakness by insults such as “you did not do very well: you are only an amateur: you are only second-class or worse”. While being arrested the police use heavy-handed `shock` tactics in order to frighten the prisoner and break down his resistance. The prisoner is usually dragged along the road to the waiting police wagon, flung into it, followed by the arresting personnel, e.g., police or Army. On the journey to the detention centre the prisoner is kicked, punched and the insults start. On arrival he is dragged from the police wagon through a gauntlet of kicks, punches and insults and flung into a cell.”

Capture was one of the greatest fears that volunteers lived with on a daily basis, so the Green Book addressed these concerns in detail and prepared volunteers for that possibility. This section was broken down into the actual arrest, the interrogation, and the legal process. There were three categories of torture that volunteers could face: physical, subtle psychological, and humiliation. Physical torture often took the form of beatings, kicking, punching, and cigarette burns. Psychological torture could include threats to family, friends, and self, or threats of assassination and disfigurement. Humiliation included being stripped naked, remarks about the prisoner’s sexual organs, and removing symbolic defense mechanisms.

One of the ways the Green Book prepared volunteers was by reminding them that they could only be held and tortured for a maximum of 7 days. Although the experience would likely be horrific, it could only last for a relatively brief duration; if they confessed or capitulated during their interrogation they could easily face a lifetime in prison where they would experience much of the same torture. One of the coping strategies they employed was to form images in their minds or on the surrounding walls, directing their concentration away from the interrogators and diverting it toward positive or neutral ideas, even something as simple as a flickering candle or a leaf.

Overall, what the Green Book does is it clearly lays out the ideological foundations of the movement, the requirements of its volunteers, the methodology for identifying and categorising enemies, the tactics that should be employed, and it also addresses the greatest fears of volunteers and teaches them how to cope in the event that they must face them. These are the foundational psychological requirements that are needed to recruit and retain effective underground guerillas. They must know why they are taking action, what their actions will achieve, how to behave, who they are targeting, and they need to know that they will be able to overcome their fears should they need to face them.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 27, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

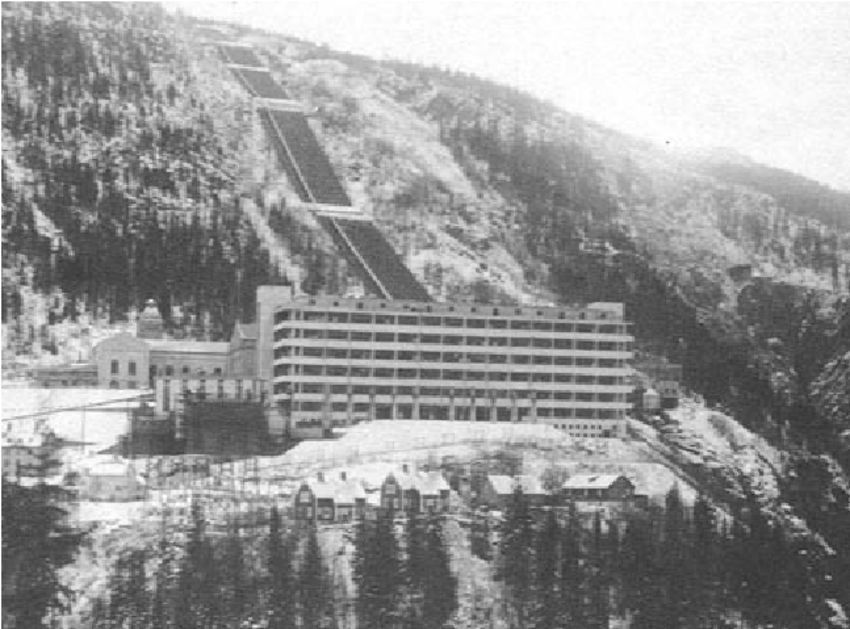

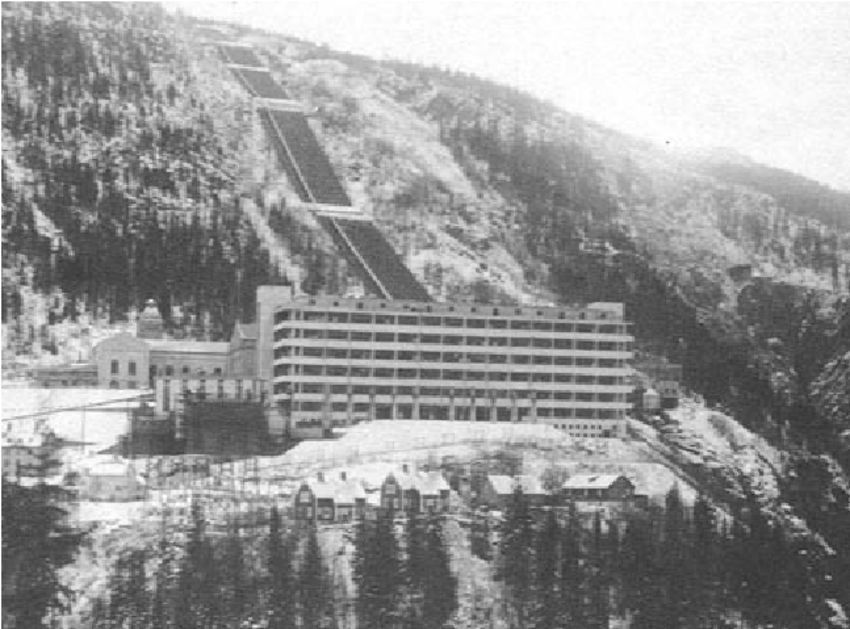

Featured image: Vemork hydroelectric plant, Norway

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

“The tough gangster type of detective fiction was of little use [in underground operations], and, in fact, likely to be a danger. Help and support to the Norwegian resistance could only be provided by [people] of character, who were prepared to adapt themselves and their views—even their orders at times—to other people and other considerations, once they saw that change was necessary. Common sense and adaptability are the two main virtues required in anyone who is to work underground, assuming a deep and broad sense of loyalty, which is the basic essential.” —Colonel John S. Wilson, leader of the Norwegian Section of the Special Operations Executive in British Exile during WWII

Thomas Gallagher’s 1975 book “Assault in Norway: Sabotaging the Nazi Nuclear Program” details a Norwegian-British covert operation carried out over the winter of 1942-43. I recommend this book for revolutionaries and serious activists, as it contains many details of how serious clandestine operations should be carried out, how to utilize intelligence and scouting, secure communications, subterfuge, proper use of terrain and other tactical advantages, and more.

The story revolves around the nuclear arms race. By 1942, U.S. and British nuclear physicists had discovered that creating an atomic bomb was a scientific possibility. This frightened them to no end, since they knew well that Germany had the most advanced nuclear research program on the planet.

Assuming that Germany had at least a 2-year research advantage, they began to look for vulnerabilities in the Nazi research program that could slow their progress toward a bomb.

A key element in this early nuclear research was “heavy water”—an isotope of standard water that can only be isolated and concentrated through the use of vast amounts of electricity. At the time, the only plant in Europe capable of creating significant amounts of heavy water was at the Norsk Hydro plant at Vemork, in Nazi-occupied Norway.

Hoping to stop the flow of heavy water in Germany, British and Norwegian-exile military intelligence hatched a plan to sabotage the Vemork plant and destroy the stockpiles of heavy water held there.

Vemork was situated in a natural fortress, located in a steep mountain valley perched on a ledge on a nearly sheer cliffside. Aerial bombing would almost certainly fail, so the plan they devised was to be carried out on foot.

In October 1942, four Norwegians tasked with reconnaissance and preparation parachuted onto the Hardanger Plateau, at the time 3500-square miles of wild, virtually inhabited land. They survived there for five frigid months, eating reindeer moss and the reindeer themselves, scouting the Vemork site, detailing the habits of guards and workers, and assessing approaches to the plant. Aided by a sympathetic local population, including workers at the plant, they gathered detailed intelligence on the location.

In February, six more men parachuted into the region. They connected with the original team and created a detailed sabotage plan, which they then carried out. I won’t share any more details here, as the harrowing story is worth reading in full.

Unlike many other World War II narratives, this is not a run-and-gun firefight story. It is a story of minute planning, survival and travel in a harsh environment, and precision action carried out using terrain advantages and intelligence-driven decision making.

As such, it is an ideal story for those of us engaged in asymmetric struggle to study.

Max Wilbert is a third-generation organizer who grew up in Seattle’s post-WTO anti-globalization and undoing racism movement, and works with Deep Green Resistance. He is the author of two books.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 7, 2019 | White Supremacy

by Max Wilbert / Counterpunch

In his book Capitalism and Slavery, Trinidadian historian Dr. Eric Williams writes that “Slavery was not born of racism: rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.”

Williams, like many others, argues that racism was created by the powerful to justify subjugation that was already in progress. In other words, the desire to exploit came first, and racism was developed as a moral system to justify the exploitation.

This has profound implications for how we approach the topic of dismantling racism and white supremacy.

Most people today know that race and racism are not “natural.” Scientifically, there is no such thing as “race.” Of course, there are differences in skin color between different groups of people. And it is possible to lump people into rough geographic groups based on their heritage and specific physical characteristics. But the concept of race is a vast oversimplification of this natural variation.

The fact that race is an artificial construct becomes clear when you study how “mixed-race” people are perceived in society today. In general, society considers a person who is half white and half black to be… black. In these sorts of examples, race is exposed as a set of stereotypes, a shorthand that people use to categorize people into a set of expectations and social boxes.

This, of course, isn’t to say that race isn’t “socially real.” In our culture, race is a material reality. But it’s a fuzzy one, a constructed one. This becomes obvious when we study the history of race and racism, and when we examine how these concepts have evolved over time to better serve the (fractured, not unitary) ruling class.

For another example of how race functions as a system of power, we can look at how various ethnic groups have shifted in and out of the privileged class “white” over time. The book How the Irish Became White traces this phenomenon, examining how mostly dirt-poor Irish immigrants to the US were treated as a sub-human race of lesser innate worth and intelligence, and how over time, the Irish became accepted as “white” in return for their largely collective agreement to oppress blacks and other non-white peoples.

Racism functions today, as it has historically, as a system used to justify the oppression and exploitation of billions of people of color worldwide. In his pioneering book The Nazi Doctors, Dr. Robert Jay Lifton writes that people cannot continue to commit atrocities without having them fully rationalized. He calls these justifications a “claim to virtue.” For the Nazis Lifton studied in particular, the mass murder of Jews was justifiable to create Lebensraum (“living space”) for the Aryan race.

Similarly, racism allows white supremacists (both overt and covert) to claim virtue as they brutally exploit people. The ideology of slavery and colonization relies on the idea that Black and indigenous peoples are “sub-human” and need to be “civilized.” Early white historians of slavery such as Ulrich B. Phillips wrote that slavery lifted the African people from barbarism, protected them, and benefited them.

From claiming that non-white people were separate species, to racist IQ tests, to Trump claiming Central American refugees are disease-ridden rapists, these campaigns of virtue have continued for hundreds of years.

If racism was born primarily out of political necessity to justify exploitation—this changes the way that we approach dismantling racism. Instead of a cultural attitude or idea that can educated away, this understanding has us see racism as fundamentally linked to a material system of exploitation. In fact, we could say that racism IS material exploitation.

Today, this system of racist exploitation takes many forms.

It takes the form of a massive private prison system that profits from the enslavement of the largest prison population in the world, a population that is disproportionately black, Latino, and indigenous. There are more black people in prison today than were in prison at the height of slavery, and these people are forced to work for free or slave wages (often $1 per hour or less) for private profit.

It takes the form of a complicit educational system that dehumanizes black and brown children from birth while railroading them on the school-to-prison pipeline.

It takes the form of an economic system that uses redlining, payday loans, and other predatory financial practices to steal from the poor black and brown people of this country, leaving people destitute and facing homelessness, disease, cold, and hunger.

It takes the form of the war on drugs, which originated in the crack cocaine epidemic in black inner cities started in the 1980’s. In 1996, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Gary Webb, who worked for The Mercury News newspaper in San Rose, launched his “Dark Alliance” series of articles with this: “For the better part of a decade, a San Francisco Bay Area drug ring sold tons of cocaine to the Crips and Bloods street gangs of Los Angeles and funneled millions in drug profits to a Latin American guerrilla army run by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.” This drug ring “opened the first pipeline between Colombia’s cocaine cartels and the black neighborhoods of Los Angeles” and, as a result, “helped spark a crack explosion in urban America.” This helped fuel the drug war, a key pillar of US internal counterinsurgency strategy, and led to massively profitable asset forfeiture programs, internal security business, and a booming private prison system. After this report, Webb was attacked by the three largest newspapers in the country, run out of his job, went bankrupt, and eventually ‘killed himself’ with two self-inflicted gunshots.

It takes the form of a fossil fuel and real-estate boom making billions of dollars while bulldozing through indigenous lands and building on top of burial grounds and sacred sites, and more broadly of environmental racism through which toxic and radioactive industries, waste, and facilities are offloaded onto communities of color.

It takes the form of a US and western foreign policy that backs right-wing coups and wars in places like Honduras, Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, The Philippines, and elsewhere for the sake of geopolitical and financial power, then demonizes refugees fleeing from this violence who can then be exploited for low wage jobs, prostitution, and practical slavery while they live in fear.

It takes the form of global trade agreements like NAFTA which impoverish millions of poor people of color globally and make it even more profitable and easy for corporations to make billions on the exploitation of cheap labor in sweatshops, maquiladoras, and electronics factories.

These are just a few examples.

***

Feminist author Marilyn Frye described oppression as being similar to a birdcage. Examine any one bar of the cage, and it appears to be no obstacle. After all, a bird can simply fly around it. Only when you consider the inter-relationship between the different bars do you get a sense of how the cage works to immobilize and confine the occupant.

Racism works in a similar way. Education, prisons, mass media, banks, war, politicians, non-profits, developers, drugs and alcohol, entertainment, and various other institutions and forces combined form a cage that is locked tightly around people of color.

This brutal system is responsible for the deaths of millions and an obscene amount of suffering.

The routine public executions of black and brown people conducted by the police are a terrorist tactic no different from the lashing of slaves. For both white and black and brown community, these displays clearly teach and enforce the power hierarchy. Body cameras have only made these dominance displays more public, and thus more effective.

***

When we understand how racism functions, we are better able to plan our attack against it.

If racism is a system of power set up to benefit the ruling class, education (the favorite method of liberals) can never be enough. Fundamentally, racism is not based on ignorance; it’s based on power and exploitation. That doesn’t mean education is worthless, but it does mean that ending racism is primarily a power struggle, not a matter of changing minds. Education is necessary, but not sufficient.

A radical approach to dismantling racism requires dismantling the material institutions that uphold and benefit from white supremacy.

To call this understanding of racism “economic” is an oversimplification. Systems of oppression function mostly to steal from the poor and reward the rich, but they are not purely rational. And this approach doesn’t mean subordinating racism to class struggle. Racism is not “less important” than class struggle, and arguments that it is (mainly from white people) have rightly drawn a lot of criticism from people of color activists.

That said, radical people of color have long understood that racism is one key pillar in a system of domination and exploitation that is much broader than racism alone. Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition in Chicago is a key example, bringing together black, Puerto Rican, working class white, and socialist groups, not to subordinate their struggles to a larger goal, but to coordinate their fight against the ruling class as a united front.

***

Modern white supremacy has its foundation in ideas and in culture, but it expresses itself primarily through economic power, military power, police power, media power, and so on. These are all concrete institutions that can be destroyed. I believe that too little attention is paid to vulnerabilities in the global system of white supremacist empire.

This line of thought has not been explored much by radical leftists. Revolutionary traditions have been dominated by strains of Marxism, which focus on seizing state and corporate power and institutions, not on destroying or incapacitating them.

The revolutionary strategy “Decisive Ecological Warfare” (DEW) was originally described in 2011 as an emergency measure to address the environmental crisis. However, this strategy has implications for the fight against racism as well.

The DEW strategy calls for underground guerilla cells to target key nodes in global industrial infrastructure, such as energy systems, communications, finance, trade hubs, and so on. The goal is to cause “cascading systems failure” in the global capitalist economy while minimizing civilian casualties. If successful, this strategy could fatally damage capitalism and deal a major blow to the power of white supremacy.

The first objection most people in the global north have to this strategy is reflexive: we are dependent on capitalist systems for survival. This is the depraved genius of any abusive system; white supremacist capitalism systematically exterminates alternative ways to live, and thus makes us dependent upon the same system that exploits and murders us. It’s the exact same method used by abusive men to control and coerce their wives and girlfriends.

Capitalism does not care about us. The state does not care about us. In the face of global ecological collapse, these institutions will leave us to die while the rich retreat to gated communities with armed guards. They make us dependent on their system then profit from our misery and death. We need to build alternative grassroots institutions, food systems, self-defense groups, and communities outside of capitalism. This is essential whether we pursue DEW or not. But without DEW and other forms of offensive struggle, the corporate-state will destroy alternative communities whenever possible. Defending these spaces will be a losing battle without larger changes.

No war is won through defense alone.

No one strategy is a magic bullet. But Decisive Ecological Warfare offers revolutionaries a weapon that could strike decisive blows against white supremacist, capitalist power structures, and create opportunities for new types of communities based on justice to exist and flourish.

Max Wilbert is a writer, activist, and organizer with the group Deep Green Resistance. He lives on occupied Kalapuya Territory in Oregon.