Why Decisive Dismantling and Warfare?

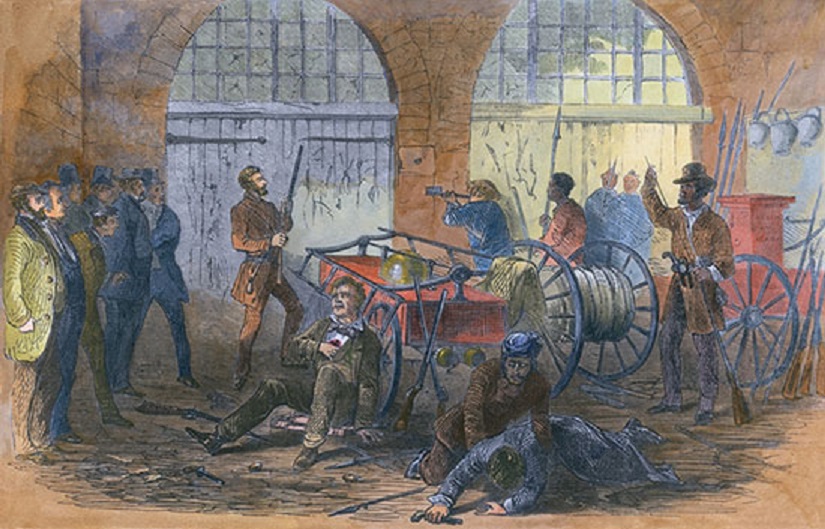

Featured image: The successful Sobibór uprising, 1943. Prisoners at the Nazi Sobibór extermination camp in Poland revolted against the Germans. About 300 of the camp’s 600 prisoners escaped, and about 50 of these survived the war.

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There is one final argument that resisters in this scenario made for actions against the economy as a whole, rather than engaging in piecemeal or tentative actions: the element of surprise. They recognized that sporadic sabotage would sacrifice the element of surprise and allow their enemy to regroup and develop ways of coping with future actions. They recognized that sometimes those methods of coping would be desirable for the resistance (for example, a shift toward less intensive local supplies of energy) and sometimes they would be undesirable (for example, deployment of rapid repair teams, aerial monitoring by remotely piloted drones, martial law, etc.). Resisters recognized that they could compensate for exposing some of their tactics by carrying out a series of decisive surprise operations within a larger progressive struggle.

On the other hand, in this scenario resisters understand that DEW depended on relatively simple “appropriate technology” tactics (both aboveground and underground). It depended on small groups and was relatively simple rather than complex. There was not a lot of secret tactical information to give away. In fact, escalating actions with straightforward tactics were beneficial to their resistance movement. Analyst John Robb has discussed this point while studying insurgencies in countries like Iraq. Most insurgent tactics are not very complex, but resistance groups can continually learn from the examples, successes, and failures of other groups in the “bazaar” of insurgency. Decentralized cells are able to see the successes of cells they have no direct communication with, and because the tactics are relatively simple, they can quickly mimic successful tactics and adapt them to their own resources and circumstances. In this way, successful tactics rapidly proliferate to new groups even with minimal underground communication.

Hypothetical historians looking back might note another potential shortcoming of DEW: that it required perhaps too many people involved in risky tactics, and that resistance organizations lacked the numbers and logistical persistence required for prolonged struggle. That was a valid concern, and was dealt with proactively by developing effective support networks early on. Of course, other suggested strategies—such as a mass movement of any kind—required far more people and far larger support networks engaging in resistance. Many underground networks operated on a small budget, and although they required more specialized equipment, they generally required far fewer resources than mass movements.

Continuing this scenario a bit further, historians asked: how well did Decisive Ecological Warfare rate on the checklist of strategic criteria we provided at the end of the Introduction to Strategy.

Objective: This strategy had a clear, well-defined, and attainable objective.

Feasibility: This strategy had a clear A to B path from the then-current context to the desired objective, as well as contingencies to deal with setbacks and upsets. Many believed it was a more coherent and feasible strategy than any other they’d seen proposed to deal with these problems.

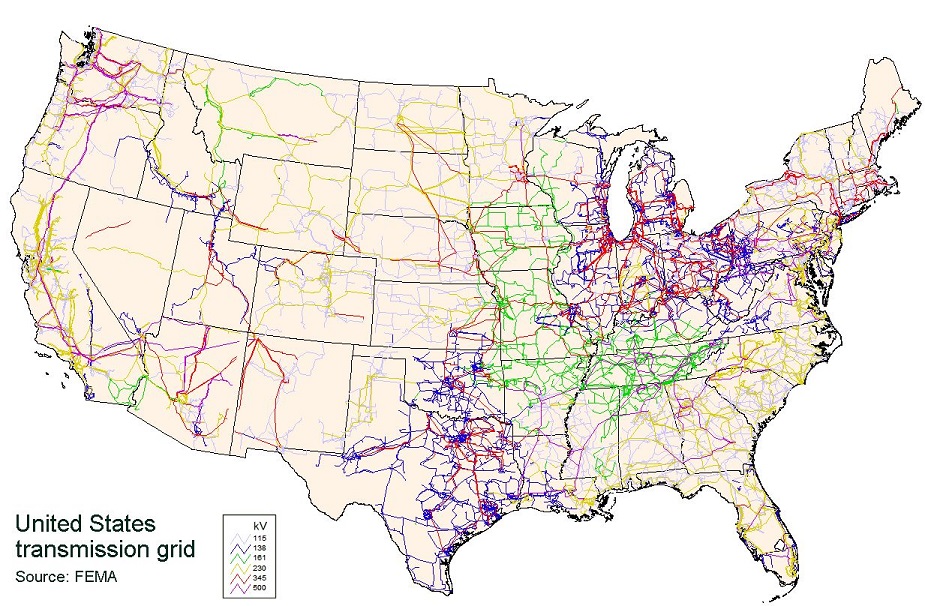

Resource Limitations: How many people are required for a serious and successful resistance movement? Can we get a ballpark number from historical resistance movements and insurgencies of all kinds?

- The French Resistance. Success indeterminate. As we noted in the “The Psychology of Resistance” chapter: The French Resistance at most comprised perhaps 1 percent of the adult population, or about 200,000 people.26 The postwar French government officially recognized 220,000 people27 (though one historian estimates that the number of active resisters could have been as many as 400,00028). In addition to active resisters, there were perhaps another 300,000 with substantial involvement.29 If you include all of those people who were willing to take the risk of reading the underground newspapers, the pool of sympathizers grows to about 10 percent of the adult population, or two million people.30 The total population of France in 1940 was about forty-two million, so recognized resisters made up one out of every 200 people.

- The Irish Republican Army. Successful. At the peak of Irish resistance to British rule, the Irish War of Independence (which built on 700 years of resistance culture), the IRA had about 100,000 members (or just over 2 percent of the population of 4.5 million), about 15,000 of whom participated in the guerrilla war, and 3,000 of whom were fighters at any one time. Some of the most critical and decisive militants were in the “Twelve Disciples,” a tiny number of people who swung the course of the war. The population of occupying England at the time was about twenty-five million, with another 7.5 million in Scotland and Wales. So the IRA membership comprised one out of every forty Irish people, and one out of every 365 people in the UK. Collins’s Twelve Disciples were one out of 300,000 in the Irish population.31

- The antioccupation Iraqi insurgency. Indeterminate success. How many insurgents are operating in Iraq? Estimates vary widely and are often politically motivated, either to make the occupation seem successful or to justify further military crackdowns, and so on. US military estimates circa 2006 claim 8,000–20,000 people.31 Iraqi intelligence estimates are higher. The total population is thirty-one million, with a land area about 438,000 square kilometers. If there are 20,000 insurgents, then that is one insurgent for every 1,550 people.

- The African National Congress. Successful. How many ANC members were there? Circa 1979, the “formal political underground” consisted of 300 to 500 individuals, mostly in larger urban centers.33 The South African population was about twenty-eight million at the time, but census data for the period is notoriously unreliable due to noncooperation. That means the number of formal underground ANC members in 1979 was one out of every 56,000.

- The Weather Underground. Unsuccessful. Several hundred initially, gradually dwindling over time. In 1970 the US population was 179 million, so they were literally one in a million.

- The Black Panthers. Indeterminate success. Peak membership was in late 1960s with over 2,000 members in multiple cities.34 That’s about one in 100,000.

- North Vietnamese Communist alliance during Second Indochina War. Successful. Strength of about half a million in 1968, versus 1.2 million anti-Communist soldiers. One figure puts the size of the Vietcong army in 1964 at 1 million.35 It’s difficult to get a clear figure for total of combatants and noncombatants because of the widespread logistical support in many areas. Population in late 1960s was around forty million (both North and South), so in 1968, about one of every eighty Vietnamese people was fighting for the Communists.

- Spanish Revolutionaries in the Spanish Civil War. Both successful and unsuccessful. The National Confederation of Labor (CNT) in Spain had a membership of about three million at its height. A major driving force within the CNT was the anarchist FAI, a loose alliance of militant affinity groups. The Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) had a membership of perhaps 5,000 to 30,000 just prior to revolution, a number which increased significantly with the onset of war. The CNT and FAI were successful in bringing about a revolution in part of Spain, but were later defeated on a national scale by the Fascists. The Spanish population was about 26 million. So about one in nine Spaniards were CNT members, and (assuming the higher figure) about one in 870 Spaniards was FAI members.

- Poll tax resistance against Margaret Thatcher circa 1990. Successful. About fourteen million people were mobilized. In a population of about fifty-seven million, that’s about one in four (although most of those people participated mostly by refusing to pay a new tax).

- British suffragists. Successful. It’s hard to find absolute numbers for all suffragists. However, there were about 600 nonmilitant women’s suffrage societies. There were also militants, of whom over a thousand went to jail. The militants made all suffrage groups—even the nonmilitant ones—swell in numbers. Based on the British population at the time, the militants were perhaps one in 15,000 women, and there was a nonmilitant suffrage society for every 25,000 women.36

- Sobibór uprising. Successful. Less than a dozen core organizers and conspirators. Majority of people broke out of the camp and the camp was shut down. Up to that point perhaps a quarter of a million people had been killed at the camp. The core organizers made up perhaps one in sixty of the Jewish occupants of the camp at the time, and perhaps one in 25,000 of those who had passed through the camp on the way to their deaths.

It’s clear that a small group of intelligent, dedicated, and daring people can be extremely effective, even if they only number one in 1,000, or one in 10,000, or even one in 100,000. But they are effective in large part through an ability to mobilize larger forces, whether those forces are social movements (perhaps through noncooperation campaigns like the poll tax) or industrial bottlenecks.

Furthermore, it’s clear that if that core group can be maintained, it’s possible for it to eventually enlarge itself and become victorious.

All that said, future historians discussing this scenario will comment that DEW was designed to make maximum use of small numbers, rather than assuming that large numbers of people would materialize for timely action. If more people had been available, the strategy would have become even more effective. Furthermore, they might comment that this strategy attempted to mobilize people from a wide variety of backgrounds in ways that were feasible for them; it didn’t rely solely on militancy (which would have excluded large numbers of people) or on symbolic approaches (which would have provoked cynicism through failure).

Tactics: The tactics required for DEW were relatively simple and accessible, and many of them were low risk. They were appropriate to the scale and seriousness of the objective and the problem. Before the beginnings of DEW, the required tactics were not being implemented because of a lack of overall strategy and of organizational development both above- and underground. However, that strategy and organization were not technically difficult to develop—the main obstacles were ideological.

Risk: In evaluating risk, members of the resistance and future historians considered both the risks of acting and the risks of not acting: the risks of implementing a given strategy and the risks of not implementing it. In their case, the failure to carry out an effective strategy would have resulted in a destroyed planet and the loss of centuries of social justice efforts. The failure to carry out an effective strategy (or a failure to act at all) would have killed billions of humans and countless nonhumans. There were substantial risks for taking decisive action, risks that caused most people to stick to safer symbolic forms of action. But the risks of inaction were far greater and more permanent.

Timeliness: Properly implemented, Decisive Ecological Warfare was able to accomplish its objective within a suitable time frame, and in a reasonable sequence. Under DEW, decisive action was scaled up as rapidly as it could be based on the underlying support infrastructure. The exact point of no return for catastrophic climate change was unclear, but if there are historians or anyone else alive in the future, DEW and other measures were able to head off that level of climate change. Most other proposed measures in the beginning weren’t even trying to do so.

Simplicity and Consistency: Although a fair amount of context and knowledge was required to carry out this strategy, at its core it was very simple and consistent. It was robust enough to deal with unexpected events, and it could be explained in a simple and clear manner without jargon. The strategy was adaptable enough to be employed in many different local contexts.

Consequences: Action and inaction both have serious consequences. A serious collapse—which could involve large-scale human suffering—was frightening to many. Resisters in this alternate future believed first and foremost that a terrible outcome was not inevitable, and that they could make real changes to the way the future unfolded.