by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 10, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

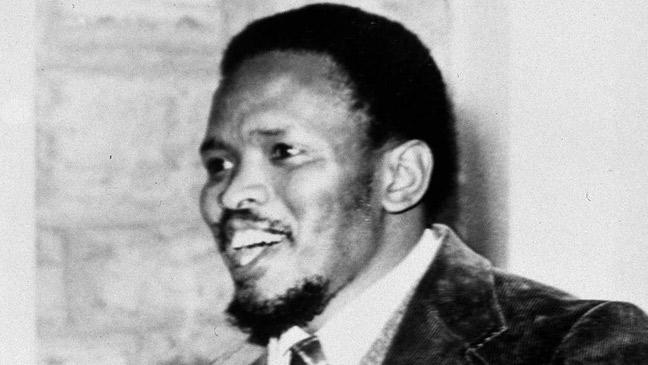

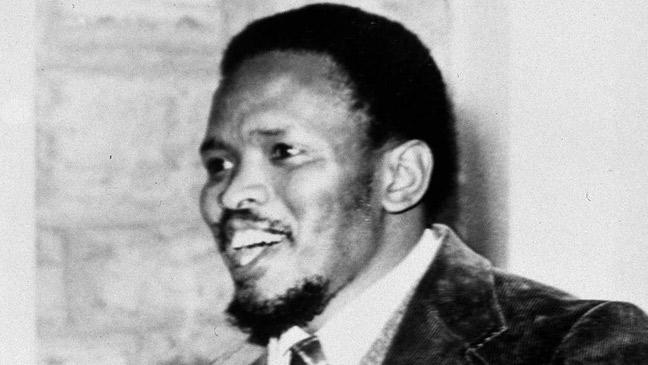

“Deep down, every liberationist is an optimist.” – Steve Biko

Steve Biko was a South African anti-apartheid activist and organizer who was murdered by the secret police in 1978. He was 32 years old when he was tortured and beaten, resulting in his death. “I Write What I Like” is a collection of writing by Biko and includes some commentary.

The collection is defined by radicalism. Biko was a believer in the mantra that freedom cannot be given, only taken. In this idea lies the core of why the liberal solution to South African apartheid remained incomplete, resulting in a highly unequal, racialized capitalist society. This is the difference between “equality” under the law and true liberation.

Biko understood that racism and apartheid were not simply technical problems. “One needs to understand the basics before setting up a remedy,” he writes. “A number of organizations now currently ‘fighting against apartheid’ are working on an oversimplified premise. They have taken a brief look at what is, and have diagnosed the problem incorrectly. They have almost completely forgotten about the side effects and have not even considered the root cause. Hence whatever is improved as a remedy will hardly cure the condition.”

Biko’s philosophy of Black Consciousness was built on undermining both the political structures that upheld apartheid as well as the internalized inferiority and superiority that still characterize race relations in many locations worldwide. He rejected integration for its own sake, recognizing that mainstream integration ideas are “white man’s integration—an integration based on exploitative values. It is an integration in which black will compete with black, using each other as rungs up a step ladder leading them to white values… these are the concepts which the Black Consciousness approach wishes to eradicate from the black man’s [sic] mind before our society is driven to chaos by irresponsible people from Coca-Cola and hamburger cultural backgrounds.”

He aimed to uphold African cultural values as important, writing “The easiness with which Africans communicate with each other is not forced by authority but is inherent in the make-up of African people… this is a manifestation of the interrelationship between man and man [sic] in the black world as opposed to the highly impersonal world in which Whitey lives.”

He understood that oppressive systems maintain their power primarily by the consent of the oppressed, which is gained via coercion, psychological tricks, propaganda, fear, and so on.

This is the reason that Biko was confident in the ability of non-violent aboveground political organizing to liberate South Africa. He was not a pacifist, and spoke in favor of the militant organizations (ANC and the PAC) that operated underground during his most active years.

These organizations had limited effectiveness in that context, but Biko strove to forge multi-generational alliances regardless, recognizing the primacy of shared goals. His approach to other groups was “tough, even aggressive language” tempered “with a basically friendly underlying spirit.”

Biko was a leader, but not an authoritarian. He promoted initiative rather than centralization. This proved to be key when many figures within various resistance movements were banned from participation in public life or sent to prison on the remote Robben Island.

He was a highly effective organizer, as one passage from his friend Aelred Stubbs C.R. makes clear. “Although Steve could hold no office in BPC because of his banning order he was constantly being consulted. It was amazing how much he knew… more than once he warned me not to get too close to certain people, white or black, whose contacts were less than desirable. He was always right. He never spoke against anyone if he could possibly help it. Even when he did, it was always in a particular context… There was this fierce integrity about them all. If you were with them you were in, and everything was given and taken. If in any way you were furthering your own ends, or trying to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds, you were out.”

Biko, like all historical figures, was no saint. His behavior was frequently sexist, and he derided feminism as an irrelevance—not an uncommon attitude at the time (or today), but inexcusable in someone fighting for justice. Like with other historical figures, we can learn from his weaknesses as well as his strength. In 2018, those lessons are still as relevant as ever.

by DGR News Service | Jan 16, 2018 | Agriculture

Agriculture did not arise from need so much as it did from relative abundance. People stayed put, had the leisure to experiment with plants, lived in coastal zones where floods gave them the model of and denizens of disturbance, built up permanent settlements that increasingly created disturbance, and were able to support a higher birthrate because of sedentism.

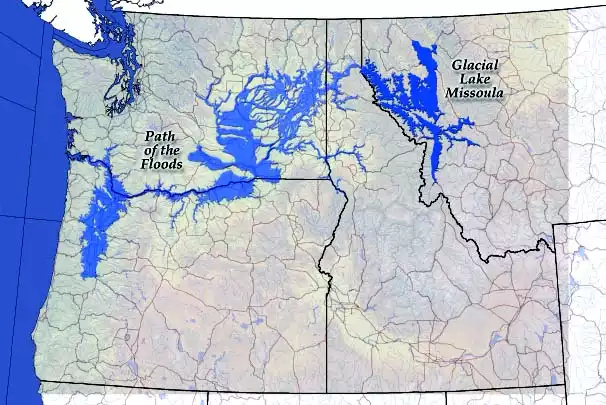

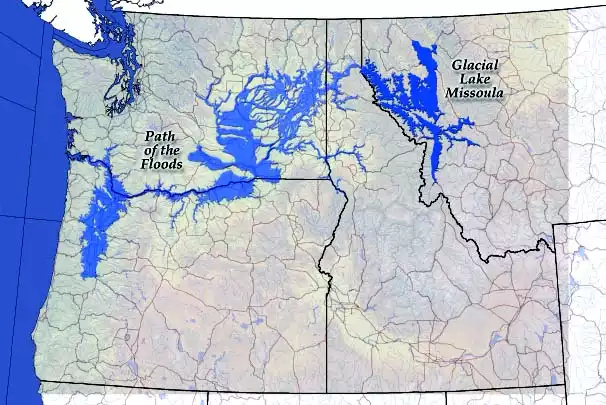

Area altered by Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

In the Middle East, this conjunction of forces occurred about ten thousand years ago, an interesting period from another angle. That date, the start of what is called the Neolithic Revolution, also coincides closely with the end of the last glaciation. As I write this, I sit in a spot that was then at the bottom of a huge lake. I live in a valley that held a lake famous to geologists, glacial Lake Missoula. The valley was formed by an ice dam that sat a couple hundred miles from here, and as the glaciers melted, the ice dam broke and re-formed many times, each time draining in a few hours a body of water the size of today’s Lake Michigan. That’s disturbance. The record of these floods can be clearly read today in giant washes and blowouts throughout the Columbia River basin in Washington State. Within the mouth of the Columbia River, several hundred miles downstream, is a twenty-five-mile-long peninsula made of sand washed downstream in these floods.

When the glaciers retreated, such catastrophic events were happening with increased frequency in floodplains around the world, especially in the Middle East. Juris Zarins of the University of Missouri has suggested that these massive disturbances and floods underlie the central Old Testament myths—the great flood, but also the Garden of Eden. Following a specific description in Genesis of the site of Eden, Zarins traces what he speculates are the four rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates system mentioned there. They would have converged in what is now the Persian Gulf, but during glaciation this would have been dry land. Further, it would have been an enormously productive plain, the sort of place that would have naturally produced an abundance of food without farming.

We call it the Garden of Eden, but it was not a garden; it was not cultivated. In fact, in Genesis, God is vengeful and specific in throwing Adam and Eve out of paradise; his punishment is that they will begin gardening. Says God, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground.” God made good on his threat, and the record now shows just how angry he was. The children of Adam and Eve would hoe rows of corn. “To condemn all of humankind to a life of full-time farming, and in particular, arable farming, was a curse indeed,” writes Colin Tudge.

At about the same time that the shapes of seeds and of butchered sheep bones were changing, so were the shapes of villages and graves. Grave goods—tools, weapons, food, and comforts—were by then nothing new in the ritual of human burials. There is even some evidence, albeit controversial, that Neanderthals, an extinct branch of the family, buried some of their dead with flowers. Burial ritual was certainly a part of hunter-gatherer life, but the advent of agriculture brought changes.

For instance, one of the world’s richest collections of early agricultural settlements lies in the rice wetlands of China’s Hupei basin on the upper Yangtze River. The region was home to the Ta-hsi culture that domesticated rice between 5,500 and 6,000 years ago. Excavation of 208 graves there found many empty of anything but the dead, while others were elaborately endowed with goods. The same pattern emerges worldwide, one of the key indicators that, for the first time in human history, some people were more highly regarded than others, that agriculture conferred social status—or, more important, more goods—to a few people.

Some of early agriculture’s graves contained headless corpses, corresponding to archaeologists finding skulls in odd places and conditions. Skulls in the Middle East, for instance, were plastered to floors or into special pits. Some of the skulls had been altered to appear older. Archaeologists take this as a sign of ancestor worship, reasoning that because of the permanent occupation of land, it became important to establish a family’s claim on the land, and veneration of ancestors was a part of that process. So, too, was a rise in the importance of the family as opposed to the entire tribe, a switch that further evidence bears out.

Coincident with this was a shift in the villages themselves. Small clutches of simple huts gave way to larger collections, but with a qualitative change as well. Some houses became larger than others. At the same time, storage bins, granaries, began to appear. Cultivated grain, more so than any form of food humans had consumed before, was storable, not just through the year, but from year to year. It is hard to overstate the importance of this simple fact as it would play out through the centuries, later making possible such developments as, for instance, the provisioning of armies. But the immediate effect of storage was to make wealth possible. The big granaries were associated with the big houses and the graves whose headless skeletons were endowed with a full complement of grave goods.

Reconstruction of the tomb of King Midas; Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey

The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey, holds one of the world’s most impressive assemblages of early agricultural remnants, including a reconstruction of a grave from a nearby city once ruled over by King Midas. He was a real guy, and his region was indeed known for its wealth in gold, taken from the Pactolus River. Yet the grave unearthed at Gordium (home of the Gordian knot) once thought to be Midas’s (but now identified as that of another in his line) was not full of gold. It was full of storage vessels for grain.

Of course to assert that agriculture’s grain made wealth possible is to assert that it also created poverty, a notion that counters the just-so story. The popular contention is that agriculture was an advance, progress that enriched humanity. Whatever the quality of our lives as hunter-gatherers, our numbers had become such that hunger forced this efficiency. Or so the story goes.

We have seen that agriculture in fact arose from abundance. More important, wealth, as distinct from abundance, is one of those dichotomous ideas only understood in the presence of its opposite, poverty. If we are to seek ways in which humans differ from all other species, this dichotomy would head the list. This is not to say that hunter-gatherers did not experience need, hard times, even starvation, just as all other animals do. We would be hard-pressed, however, to find communities of any social animal except modern humans in which an individual in the community has access to fifty, a hundred, a thousand times, or even twice as many resources as another. Yet such communities are the rule among post-agricultural humans.

Some social animals do indeed have hierarchy. Chickens and wolves have a pecking order, elk a herd bull, and bees a queen. Yet the very fact that we call the reproductive female in a hive of bees the “queen” is an imposition on animals of our ideas of hierarchy. The queen doesn’t rule, nor does she have access to forty times more food than she needs; nor does the alpha male wolf. Among elk, the herd bull is the first to starve during a rough winter, because he uses all his energy reserves during the fall rut.

The notion that agriculture created poverty is not an abstraction, but one borne out by the archaeological record. Forget the headless skeletons; they represent the minority, the richest people. A close examination of the many, buried with heads and without grave goods, makes a far more interesting platform for the question of why agriculture. Another approach to this question would be to walk the ancient settlement of Cahokia, just outside of St. Louis, Missouri, and ask: Why all these mounds?

Monk’s Mound in the ancient city of Cahokia

Cahokia was occupied until about six hundred years ago by the corn, squash, and bean culture of what is now the midwestern United States. There are a whole series of towns abandoned for no apparent reason just before the first Europeans arrived. “Mounds” understates the case, especially to those thinking the grand monuments of antiquity are part of the Old World’s lineage alone.

They are really dirt pyramids, a series of about a hundred, the largest rising close to a hundred feet high and nearly one thousand feet long on a side at its base. The only way to make such an enormous pile of dirt then was to carry it in baskets mounted on the backs of people, day in, day out, for lifetimes.

Much has been made of the creative forces that agriculture unleashed, and this is fair enough. Art, libraries, and literacy, are all agriculture’s legacy. But around the world, the first agricultural towns are marked by mounds, pyramids, temples, ziggurats, and great walls, all monuments reaching for the sky, the better to elevate the potentates in command of the construction. In each case, their command was a demonstration of enormous control over a huge force of stoop labor, often organized in one of civilization’s favorite institutions: slavery. The monuments are clear indication that, for a lot of people, life did not get better under agriculture, an observation particularly pronounced in Central America. There, the long steps leading to the pyramids’ tops are blood-stained, the elevation having been used for human sacrifice and the dramatic flinging of the victim down the long, steep steps.

Aside from its mounds, though, Cahokia is useful for considering the just-so story of agriculture’s emergence because it lies in the American Midwest, was relatively recent, and was largely contiguous and contemporaneous with surrounding hunter-gatherer territories. Like most agricultural societies, the mound builders coexisted with nomad hunters. Both groups were part of a broad trading network that brought copper from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to what is now St. Louis, and seashells from the southeastern Atlantic Coast to Montana’s Sweet Grass Hills. This coexistence gives us a chance to compare lives by comparing skeletons.

We know from their remains that the farmers were smaller, the result of general deprivation and abuse. The women, especially, were smaller. The physiques that make up a modern women’s soccer or basketball team were simply unheard of among agricultural peoples, from farming’s beginnings to only very recent times. On average, we moderns (and only those of us in the richest parts of the world) are just beginning to regain the stature that we had as hunter-gatherers, who throughout time were on average as tall as North Americans are today.

Part of this decline stems from poor diet, especially for those who provided the stoop labor. Some of it is inherent in sedentism. Almost every locale’s soil and water are deficient in one mineral or another, a fact that was not a problem for nomadic hunter-gatherers. By moving about and taking food from a variety of niches, they balanced one locale’s deficiencies against another’s excess. This is also true for the early sedentary cities that relied on seafood. They didn’t move, but the fish did, bringing with them minerals from a wide range of places.

More important, however, grain’s availability as a cheap and easily stored package of carbohydrates made it the food of the poor. It allowed one to carry baskets of dirt day after day, but its lack of nutritional balance left people malnourished and stunted. The complex carbohydrates of grains are almost instantly reduced to sugars by digestion, sometimes simply from being chewed. The skeletal record of farming peoples shows this as tooth decay, an ailment nonexistent among contemporary hunter-gatherers.

That same grain, however, could be ground to soft, energy-rich gruels that had been unavailable to previous peoples, one of the more significant changes. The pelvises from female skeletons show evidence of having delivered more children than their counterparts in the wild. The availability of soft foods meant children could be weaned earlier—at one year instead of four. Women then could turn out the masses of children that would grow up to build pyramids and mounds.

‘The maid-servant that is behind the mill’. Grinding grain on a saddle quern; Egyptian statuette. (Drawing by Martin Watts).

They could also grind the grain. Theya Molleson of the Natural History Museum in London has found a common syndrome among these women’s skeletons: the toes and knees are bent and arthritic, and the lower back is deformed. She traces this to the saddle quern, a primitive stone rolling-pin mortar and pestle used for grinding grain. These particular deformities mark lives of days spent grinding.

The baseline against which these deformities and rotten teeth are measured is just as clear. For instance, paleopathologists who have studied skeletal remains of hunter-gatherers living in the diverse and productive systems of what is now central California found them “so healthy it is somewhat discouraging to work with them.” As many societies turned to agriculture in the early days, they did so only to supplement or stabilize a basic existence of hunting and gathering. Among these people, paleopathologists found few of the difficulties associated with people who are exclusively agricultural.

The marks of agriculture on subsequent groups, however, are unmistakable. In his book The Day Before America, William H. MacLeish summarizes the record of a group in the Ohio River valley: “Almost one-fifth of the Fort Ancient settlement dies during weaning. Infants suffer growth arrests indicating that at birth their mothers were undernourished and unable to nurse well. One out of a hundred individuals lives beyond fifty. Teeth rot. Iron deficiency, anemia, is widespread, as is an infection produced by treponemata” (a genus of bacteria that causes yaws and syphilis).

The inclusion here of communicable diseases is significant and consistent with the record worldwide. Sedentary people were often packed into dense, stable villages where diseases could get a foothold, particularly those diseases related to sanitation, like cholera and tuberculosis. Just as important, the early farmers domesticated livestock, which became sources of many of our major infectious diseases, like smallpox, influenza, measles, and the plague.

Summarizing evidence from around the world, researcher Mark Cohen ticks off a list of diseases and conditions evident in skeletal and fecal remains of early farmers but absent among hunter-gatherers. The list includes malnutrition, osteomyelitis and periostitis (bone infections), intestinal parasites, yaws, syphilis, leprosy, tuberculosis, anemia (from poor diet as well as from hookworms), rickets in children, osteomalacia in adults, retarded childhood growth, and short stature among adults.

Such ills were obviously hard on the individual, as were the slavery, poverty, and oppression agriculture seems to have brought with it. And all of this seems to take us further from answering the question: Why agriculture? Remember, though, that this is an evolutionary question.

The question of agriculture can easily get tangled in values, as it should. Farming was the fundamental determinant of the quality (or lack thereof) of human life for the past ten thousand years. It made us, and makes us, what we are. We have long assumed that this fundamental technology was progress, and that progress implies an improvement in the human condition. Yet framing the question this way has no meaning. Biology and evolution don’t care very much about quality of life. What counts is persistence, or, more appropriately, endurance—a better word in that it layers meanings: to endure as a species, we endure some hardships. What counts to biology is a species’ success, defined as its members living long enough to reproduce robustly, to be fruitful and multiply. Clearly, farming abetted that process. We learned to grow food in dense, portable packages, so our societies could become dense and portable.

We were not alone in this. Estimates say our species alone uses forty percent of the primary productivity of the planet. That is, of all the solar energy striking the surface, almost half flows through our food chain—almost half to feed a single species among millions extant. That, however, overstates the case, in that a select few plants (wheat, rice, and corn especially) and a select few domestic animals (cattle, chickens, goats, and sheep for the most part, and, as a special case, dogs) are also the beneficiaries of human ubiquity. We and these species are a coalition, and the coalition as a whole plays by the biological rules. Six or so thousand years ago, some wild sheep and goats cut a deal in the Zagros Mountains of what is now Turkey. A few began hanging around the by-then longtime wheat farmers and barley growers of the Middle East. The animals’ bodies, their skeletal remains, show this transition much as the human bones do: they are smaller, more diseased, more battered and beaten, but they are more numerous, and that’s what counts. By cutting this deal, the animals suffer the abuses of society, but today they are among the most numerous and widespread species on the planet, along with us and our food crops.

Simultaneously, a whole second order of creatures—freeloaders and parasites—were cutting the same deal. Our crowding and our proximity to a few species of domestic animals gave microorganisms the laboratory they needed to develop more virulent, more enduring, and more portable configurations, and they are with us in this way today, also fruitful and multiplied. At the same time, the ecological disturbance that was a precondition of agriculture opened an ever broadening niche, not just for our domestic crops, but for a slew of wild plants that had been relegated to a narrow range. Domesticated cereals, squashes, and chenopods are not the only plants adapted to catastrophes like flood and fire. There is a range of early succession colonizers, a class of life we commonly call weeds. They are an integral part of the coalition and, as we shall see, almost as important as our evolved diseases in allowing the coalition to spread.

In all of this we can see the phenomenon that biologists call coevolution. In the waxing and waning of species that characterizes all of biological time, change does not occur in isolation. Species changeto respond to change in other species. Coalitions form. Domestication was such a change. Human selection pressure on crops and animals can be read so clearly in the archaeological record because the archaeological record is a reflection of the genetic record. We re-formed the genome of the plants just as surely as (and more significantly than) any of the most Frankensteinian projects of genetic manipulation plotted by today’s biotechnologists. The shape of life changed.

Can the same be said of the domesticates’ effects on us? Did they reengineer humans? After all, we can see the change in the human body clearly written in the archaeological record. Or at least we can if for a second we allow ourselves to lapse into Lamarckianism. In 1809, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck set forth a pre-Darwinian theory of evolution that suggested that environmentally conditioned changes in an individual would be inherited by the subsequent generations. That is, to put it in modern terms, conditioning changes the genome. This would imply that a spaniel with a docked tail would spawn stub-tailed progeny, or that a weightlifter’s children would emerge from the womb with bulging biceps. We know this is false. (Mostly we know—there are some valid neo-Lamarckian arguments.) Many of the changes in humans I’ve cited above are in fact responses to the changing conditions brought on by agriculture: the malnutrition, disease, and deformed bones were not inherited, but battered into place with each new generation.

These changes are the result of cultural, not biological, evolution. Do not discount such changes as unimportant; culture evolves as surely—and as inexorably and anarchically—as do our bodies, and it does indeed have enormous effect on our quality of life. Poverty is a direct result of cultural evolution, and despite ten thousand years of railing and warning against it, the result is still, as Christ predicted, that the poor are always with us.

By bringing this distinction between biological and cultural evolution into play, I mean to set a higher hurdle for the argument that agriculture was a powerful enough leap in technology to be read in our genome. Agriculture was social evolution, but at the same time it also instigated genuine biological evolution in humans.

Take the example of sickle-cell anemia. As with many inherited diseases, the occurrence of sickle-cell anemia varies by ethnic group, but it is particularly common in those from Africa. The explanation for this was a long time coming, until someone finally figured out that what we regard as a disease is sometimes an adaptation, a result of natural selection. Sickle-cell anemia confers resistance to malaria, which is to say, if one lives in an area infested with malaria, it is an advantage, not a disease; it is an aid to living and reproducing and passing on that gene for the condition. The other piece of this puzzle emerged only very recently. In 2001, Dr. Sarah A. Tishkoff, a population geneticist at the University of Maryland, reported the results of analysis of human DNA and of the gene for sickle-cell anemia. The gene variant common in Africa arose roughly eight thousand years ago, and some four thousand years ago in the case of a second version of the gene common among peoples of the Mediterranean, India, and North Africa. This revelation came as something of a shock for people who thought malaria to be a more ancient disease. Its origins coincide nicely with those of agriculture, which scientists say is no accident. The disturbance—clearing tropical forests first in Africa, and later in those other regions—created precisely the sort of conditions in which mosquitoes thrive. Thus, malaria is an agricultural disease.

There are similar and simpler arguments to be made about lactose intolerance, an inherited condition mostly present among ethnic groups without a long agricultural history. People who had no cows, goats, or horses had no milk in their adult diet. Our bodies had to evolve to produce the enzymes to digest it, a trick passed on in genes. Lactose is a sugar, and leads to a range of diet-related intolerances. The same sort of argument emerges with obesity and sugar diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even alcoholism. All are widespread in hunter-gatherer groups suddenly switched to an agricultural diet of dense carbohydrates and sugars. The ability of some people to survive these radical foods evolved only slowly through drastic selection pressure.

All of this points to coevolution, which is the deepest answer to the question of why agriculture. The question implies motive, which is to say we chose agriculture because it was somehow better. There are indeed arguments that it was. Yes, life might have gotten harder in the short term, but storable food provided some measure of long-term security, so there was a bargain of sorts. And while the skeletal remains show a harsh life for the masses, the wealthy were clearly better off and had access to resources, luxury, and security far beyond anything a hunter-gatherer ancestor could imagine. Yet we can raise all the counterarguments and suggest they at least balance the plusses, a contention bolstered by modern experience. That is, we have no clear examples of colonized hunter-gatherers who willingly, peacefully converted to farming. Most went as slaves; most were dragged kicking and screaming, or just plain died.

The coevolution argument provokes a clearer answer to the question: Why agriculture? We are speaking of domestication, a special kind of evolution we also call taming. We tamed the plants and animals so they could serve our ends, a sort of biological slavery, but if coevolution is true, the converse must also be true. The plants and animals tamed us. In biological terms, wheat is successful; its success is built on the fact that it tamed humans. Wheat altered us, altered our genome, to use us.

—

This is an excerpt from Against the Grain by Richard Manning

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 5, 2018 | ANALYSIS, Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: ATTA KENARE/AFP/Getty Images

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Other Plans” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

Russia is a country with a negative population growth caused by “a collapse of the birth rate and a catastrophic surge in the death rate.”64 The country has a 0.6 percent population decrease, which means it will lose 22 percent of the population by 2050. That adds up to thirty million fewer people.65

One reason for the decline is that Russia has an extremely high involuntary infertility rate. Somewhere between 13 and 20 percent of married couples are infertile, and that number may be rising.66 For women, one of the main causes was a society-wide reliance on abortion as a form of birth control, abortions often done under substandard medical conditions. The literal scars of such procedures have left many women unable to conceive or carry to term. Sexually transmitted diseases are also a culprit—rates of syphilis are literally hundreds of times higher in Russia than in other European countries.67 Marriage rates have dropped and divorce rates risen, and 30 percent of Russia’s babies are being delivered to single mothers—this in a country too poor to offer public benefits. Women can’t afford to have more children.

Add to that a mortality rate that is “utterly breathtaking.”68 Tuberculosis, AIDS, alcoholism, and the disappearance of socialized medicine have pulled the numbers up. The main two causes of death, though, are cardiovascular disease (CVD), which in thirty-five years increased 25 percent for women and an astounding 65 percent for men, and injury. The increases in CVD is traceable to smoking, poor diet, sedentarism, and severe social stress. The injury category includes “murder, suicide, traffic, poisoning and other violent causes.”69 The violence is so bad that the death rate for injury and poisoning for Russian men is twelve times higher than for British men. And both CVD and the violence are helped along by vodka, which Russians drink at an extraordinary rate, equivalent to 125 cc “for everyone, every day.”70

Population in Russia is dropping dramatically without a cataclysmic event or a Pol Pot–styled genocide, which the authors of this book are often accused of suggesting. Though each individual death is its own world of tragedy, the deaths have not collectively brought daily life—or even the government—to a halt.

Russia may best illustrate the kind of slow decline of which Greer writes; and Russia’s disintegration is not even based on energy descent, as oil and gas are still abundant. The former USSR may give us good insights into people’s responses to economic decline, and how best to survive it, but as an example it does not address the conditions of biotic collapse that are our fundamental concern.

Except in one instance: Chernobyl. Ninety thousand square miles were contaminated with radiation; 350,000 people were displaced; and there is a permanent “exclusionary zone” encompassing a nineteen-mile radius and the ghosts of seventy-six towns.

But other ghosts have come back from the dead. Because despite the cesium-137 that’s deadly for 600 years and the strontium-90 that mammal bones mistake for calcium, Chernobyl has become a miracle of megafauna: the European bison have returned, as well as, somehow, the Przewalski’s horse. There are packs—that’s plural—of wolves. There are beavers coaxing back the lost wetlands. There are wild boar. There are European lynx. There are endangered birds like the black stork and the white-tailed eagle, glorious in their eight-foot wingspans. All this even though ten years after the accident, geneticists found small rodents with “an extraordinary amount of genetic damage.” They had a mutation rate “probably thousands of times greater than normal.”71 Yet twenty years after the accident, and with multiple excursions into the contaminated area, the same researcher, Dr. Robert Baker, said flat-out, “The benefit of excluding humans from this highly contaminated ecosystem appears to outweigh significantly any negative cost associated with Chernobyl radiation.”72 Witnessing the return of bison and wolves, who could say otherwise? Even a nuclear disaster is better for living creatures than civilization. And the real, if fledgling, hope: this planet, made not by some Lord God but instead by the work of all those creatures great and small, could repair herself if we would just stop destroying.

Bison in the Chernobyl exclusion zone

There are better ways to reduce our numbers than through alcoholism, syphilis, and nuclear accidents. We don’t need to wring our hands in helpless horror, stuck in a wrenching ethical dilemma between human rights and ecological drawdown. In fact, the most efficacious way to address the twin problems of population and resource depletion is by supporting human rights.

One of the great success stories of recent years is Iran. People’s desire for children turns out to be very malleable. Even in a context of religious fundamentalism, Iran was able to reduce its birthrate dramatically. In 1979, Ayatollah Khamenei dissolved Iran’s family planning efforts because he wanted soldiers for Islam to fight Iraq (and n.b. to those who still think they can be peace activists without being feminist). The population surged in response, reaching a 4.2 percent growth rate, which is the upper limit of what is biologically possible for humans. Iran went from 34 million people in 1979 to 63 million by 1998.73 Let’s be very clear about what this means for women. Girls as young as nine were legally handed over to adult men for sexual abuse: for me, the word “marriage” does not work as a euphemism for the raping of children.

The population surge proved to be a huge social burden immediately, and Iran’s leaders “realized that overcrowding, environmental degradation, and unemployment were undermining Iran’s future.”74 Health advocates, religious leaders, and community organizers held a summit to strategize.

They knew that free birth control was essential, but it wouldn’t be enough. All the major institutions of society had to get involved. Family planning policies were reinstituted and a broad public education effort was launched. Government ministries and the television company were brought into the project: soap operas took up the subject. Fifteen thousand rural clinics were founded and eighty mobile health care clinics brought birth control to remote areas. Thirty-five thousand family planning volunteers were trained to teach people in their neighborhoods about birth control options, and there were also workplace education campaigns. The government got religious leaders to proclaim that Allah wasn’t opposed to vasectomies; after that, vasectomies increased dramatically. In order to get a marriage license both halves of the couple had to attend a class on contraception. And new laws withdrew food subsidies and health care coverage after a couple’s third child, applying the stick as a backup to the carrots.

The biggest social initiative was to raise the status of women. Female literacy went from 25 percent in 1970 to over 70 percent in 2000. Ninety percent of girls now attend school.75

In seven years, Iran’s birthrate was sliced in half from seven children per woman to under three. So it can be done, and quickly, by doing the things we should be doing anyway. As Richard Stearns writes, “The single most significant thing that can be done to cure extreme poverty is this: protect, educate, and nurture girls and women and provide them with equal rights and opportunities—educationally, economically, and socially.… This one thing can do more to address extreme poverty than food, shelter, health care, economic development, or increased foreign assistance.”76

There is no reason for people who care about human rights to fear taking on this issue. Two things work to stop overpopulation: ending poverty and ending patriarchy. People are poor because the rich are stealing from them. And most women have no control over how men use our bodies. If the major institutions around the globe would put their efforts behind initiatives like Iran’s, there is still every hope that the world could turn toward both justice and sustainability.

Photo by Jaunt and Joy on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 20, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

According to an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in July, the planet is in the midst of the 6th mass extinction event. Strikingly, the scientists who wrote the article call this a “biological annihilation.”

This isn’t a random sequence outcome of a natural societal development. The dominant global culture (industrial civilization) is a culture of imperialism. We can define that as a culture that colonizes and extracts resources as a standard way of operating.

Industrial civilization has become the dominant culture by violence, and violence maintains it.

Timber is ripped from forests and shredded for sale. Rivers are enslaved to irrigate fields and power cities. Oil is burned to propel commerce. Fracking injects poisons into the planet in order to extract even more petrochemicals. Traditional ways of life and sustainable relationships with the land are destroyed, so the only alternative is the toxic (and profitable) cycle of wage labor, debt, and poverty. Patriarchy teaches men to objectify and dominate women, and women to acquiesce. The result is a loss of bodily autonomy to the point that half of all children are unwanted by the mother, and a culture in which eating disorders are a leading cause of death among young women and teenage girls. The legacy of slavery underlies the modern prison system, where vast profits are made by locking up the powerless and oppressed.

As a friend put it, “oppression is always in service of resource extraction.”

The shiny gadgets used to enthrall us are made possible by child miners in the Congo, by workers toiling to the point of mass suicide in Foxconn factories in China, and by the exportation of e-waste to conveniently isolated locations.

And of course, the military, police, and private security (mercenaries) are ready to beat, imprison, or kill anyone who stands in the way of this system. Finally, this culture’s atomized families and recent trends like the rise of neo-liberalism help ensure we remain isolated physically and emotionally, without the strength that comes from being part of a community.

Between the threat of violence, bribery, and the sense of helplessness that comes from isolation, most people aren’t willing to resist. American culture has been built on genocide for 500 years; at this point, most settlers can’t even imagine a society not based on violence.

For those who can, we need to get serious about our strategies.

MYTHICAL STRATEGIES

In the west, and especially in the United States, most activists operate within a mythic framework of non-violent resistance that’s far different than the liberation politics of the 1960’s and 70’s. In this mythology, violence doesn’t solve anything, and non-violence has a magical ability to win conflicts—even if those victories only occur in hearts and minds.

“We win through losing,” a friend says (sarcastically) of this mindset.

Don’t get me wrong. Non-violence can be a supremely elegant and effective technique for social change. Applied correctly—forcefully—non-violence can immobilize a repressive regime or corporate power, making it impossible to move in any direction. Violence should, of course, be avoided anytime it can be.

But non-violent resistance doesn’t always work. As another friend writes in his excellent multi-part series, “The destruction of our world isn’t an ‘environmental crisis,’ nor a ‘climate crisis.’ It’s a war waged by industrial civilisaton and capitalism against life on earth–all life–and we need a resistance movement with that analysis to respond…the decision about what strategy and tactics to use depends on the circumstances, rather than being wedded to one approach out of a vague ethical dogma…the choice between using non-violence or force is a tactical decision. Those who advocate for the use of force are not arguing for blind unthinking violence, but against blind unthinking nonviolence.”

So what’s next? What happens when non-violence doesn’t work? What should you do when you have voted, petitioned, demanded, protested, raised awareness, locked down, blockaded, and it hasn’t worked?

Do you keep using the same tactics that have failed again and again, hoping they’ll work this time?

Do you give up?

This is not a theoretical question.

It’s a situation that has been faced by many resistance movements throughout history. Lately I’ve been reflecting on one in particular; the Oka Crisis that went down near Montreal in 1990.

After 400 years of gradual land theft, the Kahnesetake band of the Mohawk Nation was left with a fraction of a fraction of its traditional territory. With land “development” encroaching continuously, tensions came to a head in 1990 when plans began moving forward to expand a golf course into an extremely important site: a pine forest next to the tribal cemetery.

Members of the Kahnesetake community went through various channels to fight the expansion, including petitioning local government and the federal Indian Bureau. Nothing worked, so they began a non-violent occupation of the golf course. After a gradual escalation—police beatings, threats from masked assailants—many of the Mohawks began carrying weapons. Special police forces were called in to raid the camp, and women stood them down. Someone began shooting—from which side is impossible to say—and a policeman was killed. After a weeks-long standoff during which many more shots were exchanged, the Mohawks were eventually evicted—but the land was protected from development.

Are we committed to winning as much as those Mohawk warriors?

Species extinction, fascist and Nazi extremism, global warming, police violence, sexual assault, human trafficking, resource extraction, industrial expansion, the prison industrial system. Are we committed to stopping these injustices?

If so, we must consider all means, including the use of force and violence.

This is an emergency.

HOW A REVOLUTION MIGHT BEGIN: THE CUBAN PRECEDENT

Perhaps one of the more important lessons of revolutionary history comes from Cuba, where in 1956, a small group of revolutionaries landed near the Sierra Maestra mountains. Almost immediately, the rebels were attacked and routed. Of the original group of 80, only about 20 regrouped in the mountains.

Nonetheless, over the next several years, their movement grew. They recruited locals, coordinated with underground cells in Havana and other urban areas, and built support networks elsewhere in Latin America. By January 1959, the revolutionaries had overthrown the rule of the Batista government.

Marx informs any revolutionary, but I am not a Marxist. Like China and the Soviet Union, Cuba followed a highly centralized, industrialized development path that contains much to criticize (while still representing an inspiring alternative to the capitalist model). The events that took place after the Cuban revolution are, to me, less interesting than the methods used to carry out the revolution itself. Che’s guerilla warfare techniques were well suited to the rural countryside and have influenced every revolutionary group since. And there is much to learn from how the Cuban underground organized.

The most important lesson, I think, is that the revolutionaries just got started. They didn’t wait for the perfect conditions, which they knew would never appear. They suffered major setbacks, but they persisted, and they had unshakeable confidence that they would prevail. Despite their lack of numbers, they had a good foundational strategy. By playing to their strengths, avoiding unwise confrontations, and by gradually building strength, they defeated a force that was initially much superior and initiated a tectonic political shift from capitalist vassal state to socialist nation-building experiment.

DAKOTA ACCESS PIPELINE SABOTAGE

On July 24th, two women—Ruby Montoya and Jessica Reznicek—publicly admitted to sabotaging the Dakota Access Pipeline in an attempt to stop the desecration of native territory, the ongoing destruction of the climate, and threats to major rivers.

In an interview with them shortly after, they explained their motivations. Ruby, who was a kindergarten teacher before quitting her job to fight the pipeline, was in tears as she explained that those kids would have no future without action.

Jessica and Ruby have repeatedly called for others to take similar actions of eco-sabotage.

Last year, I published a call for ecological special forces:

“Small forces of ecological commandos that could target the fundamental sources of power that are destroying the planet. We have seen examples of this. In Nigeria, commando forces have been fighting a guerrilla war of sabotage against Shell Oil Corporation for decades. At times, they have reduced oil output by more than 60%.”

As we noted, “no environmental group has ever had that level of success. Not even close. In the U.S., clandestine ecological resistance has been relatively minimal. However, isolated incidents have taken place. A 2013 attack on an electrical station in central California inflicted millions of dollars in damage to difficult-to-replace components used simple hunting rifles. The action took a total of 19 minutes, displaying the sort of discipline, speed, and tactical acumen required for special forces operations.

“Our situation is desperate. Things continue to get worse. False solutions, greenwashing, corporate co-optation, and rollbacks of previous victories are relentless. Resistance communities are fractured, isolated, and disempowered. However, the centralized, industrialized, and computerized nature of global empire means that the system is vulnerable. Power is mostly concentrated and projected via a few systems that are vulnerable.

“Even powerful empires can be defeated. But those victories won’t happen if we engage on their terms. Ecological special forces provide a method and means for decisive operations that deal significant damage to the functioning of global capitalism and industrialism. With enough coordination, these sorts of attacks could deal death blows to entire industrial economies, and perhaps (with the help of aboveground movements, ecological limits, and so on) to industrialism as a whole.

“Implementation of this strategy will require highly motivated, dedicated, and skilled individuals. Serious consideration of security, anonymity, and tactics will be required. But this system was built by human beings; we can take it apart as well.”

That strategy, while not sufficient on its own, would help us move towards a more effective, forceful movement. Read that article here.

This may sound drastic to you. But consider: the planet is being destroyed. We’re living through the sixth great mass extinction event. The most powerful nation in the world just elected Donald Trump. There is no sign of a looming political shift, and alternative parties and movements are largely sidelined or co-opted.

CHARLOTTESVILLE COMES HOME

As I write this, I’m at my sister’s house; she’s just given birth to my (first) nephew, who has beautiful brown skin and is what’s called “mixed race.” Before long, he will emerge into the world, and he will be perceived as a black child, and then as he grows, a black man.

White supremacy is experiencing a resurgence. Days before I write this, at a neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, hundreds of virulent racists marched, chanting “blood and soil” and “white lives matter.” In front of studiously inactive police, they severely injured more than two dozen anti-racist protestors and one fascist plowed his car into a crowd of anti-racist protestors, killing a woman and severely injuring others.

The day after, as my sister lay in bed nursing her new beautiful baby boy, more white supremacists were gathering in downtown Seattle, about two miles away. Later, the Amerikkkan president defended the supremacists, saying there were “great people” involved in the white supremacist protests.

To anyone who is paying attention, this isn’t a surprise. Our nation has been built on foundation of systematic white supremacy in service of the extraction of resources. Those are the roots of this society, and the trend continues today. The everyday violence of this culture fuels its operation. The system is functioning perfectly, exploiting every possible method for economic, social, and political gain while funneling wealth to the top.

How can I make a better world for my nephew? How can I make a survivable world? My answer—at least one part of it—is by halting that everyday violence.

It’s time that we organized and carried out a revolution.

—

Max Wilbert is a writer, activist, and organizer with the group Deep Green Resistance. He lives on occupied Kalapuya Territory in Oregon.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 13, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the twelfth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Pacifism is objectively pro-Fascist. This is elementary common sense. If you hamper the war effort of one side you automatically help that of the other. Nor is there any real way of remaining outside such a war as the present one. . . . others imagine that one can somehow ‘overcome’ the German army by lying on one’s back, let them go on imagining it, but let them also wonder occasionally whether this is not an illusion due to security, too much money and a simple ignorance of the way in which things actually happen. . . . Despotic governments can stand “moral force” till the cows come home; what they fear is physical force.

—George Orwell, author and journalist

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Nonviolence has an important part to play in our resistance. That said, there are a number issues with how it is promoted. Also the advocates of nonviolence have not adequately responded to the arguments made against it.

The next four posts will explore the issues with nonviolence; the effectiveness of nonviolence; and why nonviolence has become the default tactic of western activists. Nonviolent action is a very important tool in our resistance against industrial civilisation. So is using force or self defense. When, and in what circumstance, a particular method should be used is dependent upon a number of factors.

Most activists do not hear any arguments against nonviolence; it’s generally accepted by liberal activists, and within liberal communities in general, that the use of “violence” or force is wrong and self-defeating. The state, mainstream media, and nonviolence fundamentalists have been very successful at demonising the use of force. As a result, many activists have internalised the fear and criticism directed at those willing to advocate for or use militant tactics to resist capitalism and the destruction of the natural world. [1]

Problem one with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Rewriting history to make nonviolence look more effective

Nonviolence fundamentalists have often reframed historic examples by (1) excluding important contributions made by groups using force or militant resistance and (2) overstating/exaggerating the (material) success of nonviolent movements and actions. Examples of these historical omissions and rewritings include the Indian Independence Movement, the US Civil Rights Movement and the African National Congress’ struggle to end Apartheid. [2]

Gandhi’s nonviolence movement would not have had the limited success it did without the insurrectional acts of Bhagat Singh [3] and Chandra Bose. [4] The Indian Independence movement was also assisted by the decline in British power after fighting two world wars in thirty years. [5]

The US Civil Rights Movement was largely nonviolent, but it is doubtful that participants would have been successful without the more militant strategies and tactics of Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. Groups like the Deacons for Defense provided critical armed protection from violent KKK groups and other white supremacists in the south, in many cases engaging in pitched shootouts. In other cases, their armed presence at rallies and houses where organisers lived prevented violence from taking place.

Faced with both militants and pacifists, the US government had a choice to work with Dr. King or to allow Malcolm X to gain more support. The US state ultimately chose to work with Dr King to reform civil rights laws. [6] Charles Cobb and Gabriel Carlyle argue that “although nonviolence was crucial to the gains made by the freedom struggle of the 1950s and ’60s, those gains could not have been achieved without the complementary – and under-appreciated – practice of armed self-defence.”

When Nelson Mandela was compared to Gandhi and King, Mandela’s responses was “I was not like them. For them, nonviolence was a principle. For me, it was a tactic. And when the tactic wasn’t working, I reversed it and started over.” [7]

While Mandela began by practicing only nonviolence, he realised that he could not effectively win the struggle against the South African Apartheid Government through nonviolent means alone. After this realisation, he helped to found the militant wing of the ANC, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation). The combination of nonviolent and violent strategies and tactics is what ultimately brought the South African state to the negotiating table in 1990 [8].

Ward Churchill argues that there has never been a successful revolution or social reorganisation based solely on pacifism ; some form of “violence” or force has been essential in every case. [9]

In many cases of “successful” nonviolent resistance movements, change has been decidedly partial. “Take, for example, the issue of colonization in India and South Africa. Although many sources credit nonviolent campaigns and practices with the “end” of colonization in these regions (and others), in reality both India and South Africa exist under neocolonialist rule and hierarchies; rather than an “end” to colonialist practices, nonviolent movements have perpetuated the oppressive colonialist structures of power by placing power in the hands of indigenous elites while imperial powers still maintain control of the banks.” [10]

Contrary to what nonviolent advocates and pacifists often maintain, neither Gandhi nor King were completely opposed to the use of force. On this point, Gandhi affirmed that “I do believe that, where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence. I would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honor than that she should, in a cowardly manner, become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonor,” and “it is better to be violent if there is violence in our hearts than to put on the cloak of nonviolence to cover impotence.” [11]

In response to accusations of pacifism, King said “I am no doctrinaire pacifist. I have tried to embrace a realistic pacifism…violence exercised in self-defense, which all societies, from the most primitive to the most cultured and civilized, accept as moral and legal…the principle of self-defense, even involving weapons and bloodshed, has never been condemned, even by Gandhi, who sanctioned it for those unable to master pure nonviolence.” [12]

Thus, the real views of these icons have been distorted into an dishonest, unhelpful lie.

Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan recently conducted a statistical analysis of the effectiveness of nonviolence. They compiled a list of 323 major nonviolent campaigns and violent conflicts from 1900 to 2006 and rated them as “successful,” “partially successful” or “failed.” [13]

On the whole, Chenoweth and Stephan utilize vague statistics to obscure more complex truths. They do not define violence in their analysis. They do not use a revolutionary criteria, and as a result the “Color Revolutions” and other reformist movements are classified as successful. They credit nonviolent movements with victory when international peacekeeping forces, i.e. armies, had to be called in to protect peaceful protesters. They have not published the list of campaigns and conflicts used in their original study. They explain that the list of major nonviolent campaigns was provided by “experts in nonviolence conflict,” who are likely to be biased toward promoting the efficacy of nonviolent campaigns and strategies. The “violent” conflicts they do include in their analysis are armed conflicts with over 1,000 combatant deaths: in others words, wars. Social movements and full-on wars are not comparable in this way; they do not occur under similar circumstances and factors beyond the participants’ choices influencing what sort of conflict occurs.

Chenoweth and Stephan state that they elected to include only “major” nonviolent campaigns, so weeded out ineffective nonviolent campaigns that only involved small numbers of people and yielded insignificant results. Chenoweth and Stephan took a number of measures to try to correct this bias in their study but none of these would of had a significant affect. [14]

This is the twelfth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos, 2007, page 5, Read online here

- Chapter six of Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, looks at these three examples in detail, Read online here

- See the Resistance Profile for Hindustan Socialist Republican Association on the DGR website

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, page 8-10, Read online here

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 55

- Deep Green Resistance, Lierre Keith, Aric McBay, and Derrick Jensen, 2011, page 396. Pacifism as Pathology, page 142-3

- https://www.jacobinmag.com/2013/12/bob-herbert-on-nelson-mandela-1918-2013/, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/12/06/anger-at-the-heart-of-nelson-mandela-s-violent-struggle.html, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/12/05/don-t-sanitize-nelson-mandela-he-s-honored-now-but-was-hated-then.html, http://thegrio.com/2013/12/06/why-we-have-to-celebrate-nelson-mandelas-revolutionary-past/

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 75-81, Read online here. See my article on Mandela’s path to militant resistance

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 57 and page 137

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, page 8-10. Counterpower: Making Change Happen, Tim Gee, 2011 page 127. Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 68-96, Read online here

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 74

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 92

- Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, 2012

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 43-46

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org