by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 5, 2017 | Toxification

by Intercontinental Cry

In southeastern Utah, not far from many of America’s famed national parks, lies America’s last remaining uranium mill. After more than 36 years in operation, the leaders of the nearby Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s White Mesa community worry that lax regulations and aging infrastructure are putting their water supply, and their way of life, at risk.

Learn more about the White Mesa Mill at the Grand Canyon Trust.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 16, 2017 | Mining & Drilling

Featured image: A humble warning at the Canyon mine. Photo: Garet Bleir

by John Ahni Schertow / Intercontinental Cry

A Canadian company, Energy Fuels Inc., is about to begin mining high-grade uranium ore just 5 miles from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

If the project goes ahead, the Colorado River could be exposed to dangerous levels of radiation, threatening the water supply for 40 million people downstream, including residents of Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Don’t like the sound of that? Head over to Thunderclap now to raise your voice!

The Canyon Mine, which pre-dates a 2012 ban on uranium mining near the Canyon’s rim, would annually extract 109,500 tons of ore for use in US nuclear reactors. Post-extraction, 750 tonnes of radioactive ore would be transported daily from the Canyon Mine to the White Mesa Mill uranium processing facility in Utah, traversing Arizona in unmarked flatbed trucks covered only with tarpaulins.

The Canyon mine, located 5 miles from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Photo: Garet Bleir

The toxic material would pass through several towns, Navajo communities and the city of Flagstaff en route to the processing facility, which is only three miles from the White Mountain Ute tribal community.

From extraction to transport and processing, every stage of the uranium project could expose this iconic landscape, its watershed and inhabitants to high levels of radiation.

There’s more. With President Trump’s recent cuts to the EPA, and the Koch Brothers’ campaign to remove the uranium mining ban, the entire Grand Canyon region faces an unprecedented threat.

The good news is that an indigenous-led movement is emerging to fight this threat.

The Havasupai Nation, whose only water source is threatened by the Canyon Mine, has teamed up with several environmental organizations to ask federal judges to intervene before the mine causes any harm.

Meanwhile, members of the Navajo Nation are working to establish a ban on the transport of uranium ore through their reservation and the White Mesa Ute are leading protests against the processing facility.

The Navajo Nation has already been devastated by 523 abandoned uranium mines and 22 wells that have been closed by the EPA due to high levels of radioactive pollution. According to the EPA, “Approximately 30 percent of the Navajo population does not have access to a public drinking water system and may be using unregulated water sources with uranium contamination.” A disproportionate number of the 54,000 Navajo living on the reservation now suffer from organ failure, kidney disease, loss of lung function, and cancer.

The Canyon mine could have a similar impact on the Havasupai Nation and millions of Americans who depend on water from the Colorado River.

IC is currently at the Grand Canyon covering this breaking story and we need your help to stay there!

Photo: Garet Bleir

IC will be onsite for the next four weeks, investigating the risks and impacts of the Canyon Mine and bringing you exclusive updates from the emerging resistance movement.

We will look at the history of the Energy Fuels processing mill and cover the outcome of the Havasupai lawsuit. We will collect expert testimony, conduct interviews with key players and introduce you to some of the people affected by uranium mining.

We’re launching a crowdfunding campaign later this month to let us complete this vital investigative journalism project.

To build momentum for this fundraising campaign, we need 100 people to join us on Thunderclap and help us send a message that the Grand Canyon has allies!

Head over to Thunderclap now to pledge your support!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 11, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Toxification

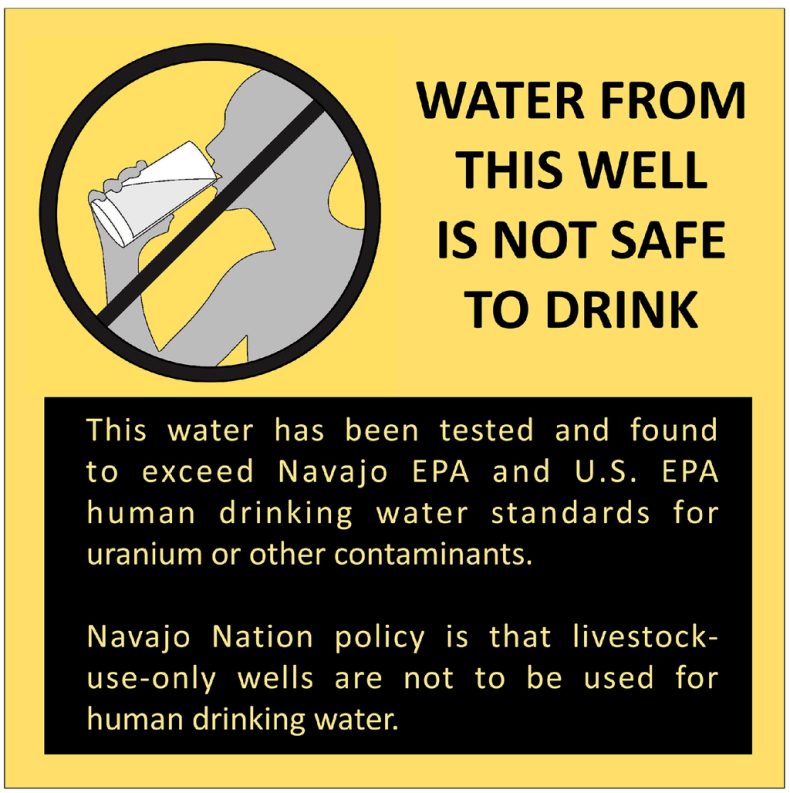

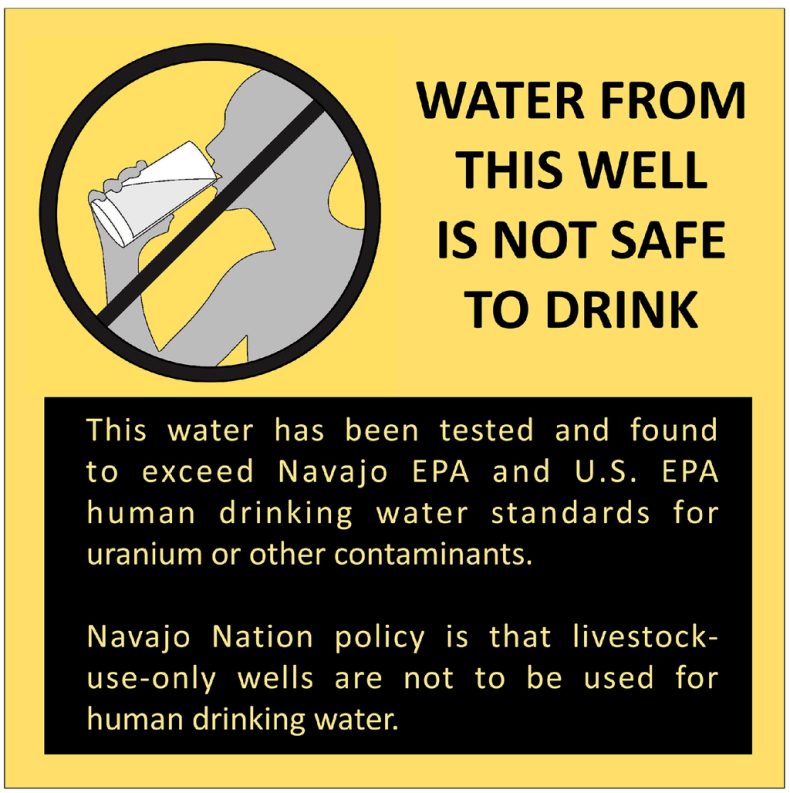

Featured image: Figure from EPA Pacific Southwest Region 9 Addressing Uranium Contamination on the Navajo Nation

By Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

Recent media coverage and spiraling public outrage over the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has completely eclipsed the ongoing environmental justice struggles of the Navajo. Even worse, the media continues to frame the situation in Flint as some sort of isolated incident. It is not. Rather, it is symptomatic of a much wider and deeper problem of environmental racism in the United States.

The history of uranium mining on Navajo (Diné) land is forever intertwined with the history of the military industrial complex. In 2002, the American Journal of Public Health ran an article entitled, “The History of Uranium Mining and the Navajo People.” Head investigators for the piece, Brugge and Gobel, framed the issue as a “tradeoff between national security and the environmental health of workers and communities.” The national history of mining for uranium ore originated in the late 1940’s when the United States decided that it was time to cut away its dependence on imported uranium. Over the next 40 years, some 4 million tons of uranium ore would be extracted from the Navajo’s territory, most of it fueling the Cold War nuclear arms race.

Situated by colonialist policies on the very margins of U.S. society, the Navajo didn’t have much choice but to seek work in the mines that started to appear following the discovery of uranium deposits on their territory. Over the years, more than 1300 uranium mines were established. When the Cold War came to an end, the mines were abandoned; but the Navajo’s struggle had just begun.

Back then, few Navajo spoke enough English to be informed about the inherent dangers of uranium exposure. The book Memories Come to Us in the Rain and the Wind: Oral Histories and Photographs of Navajo Uranium Miners and Their Families explains how the Navajo had no word for “radiation” and were cut off from more general public knowledge through language and educational barriers, and geography.

The Navajo began receiving federal health care during their confinement at Bosque Redondo in 1863. The Treaty of 1868 between the Navajos and the U.S. government was made in the good faith that the government – more specifically, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) – would take some responsibility in protecting the health of the Navajo nation. Instead, as noted in “White Man’s Medicine: The Navajo and Government Doctors, 1863-1955,” those pioneering the spirit of western medicine spent more time displacing traditional Navajo healers and knowledge banks, and much less time protecting Navajo public health. This obtuse, and ultimately short-sighted, attitude of disrespect towards Navajo healers began to shift in the late 1930’s; yet significant damage had already been done.

Founding director of the environmental cancer section of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Wilhelm C. Hueper, published a report in 1942 that tied radon gas exposure to higher incidence rates of lung cancer. He was careful to eliminate other occupational variables (like exposure to other toxins on the job) and potentially confounding, non-occupational variables (like smoking). After the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was made aware of his findings, Hueper was prohibited from speaking in public about his research; and he was reportedly even barred from traveling west of the Mississippi – lest he leak any information to at-risk populations like the Navajo.

In 1950, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) began to study the relationship between the toxins from uranium mining and lung cancer; however, they failed to properly disseminate their findings to the Navajo population. They also failed to properly acquire informed consent from the Navajos involved in the studies, which would have required informing them of previously identified and/or suspected health risks associated with working in or living near the mines. In 1955, the federal responsibility and role in Navajo healthcare was transferred from the BIA to the USPHS.

In the 1960’s, as the incidence rates of lung cancer began to climb, Navajos began to organize. A group of Navajo widows gathered together to discuss the deaths of their miner husbands; this grew into a movement steeped in science and politics that eventually brought about the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) in 1999.

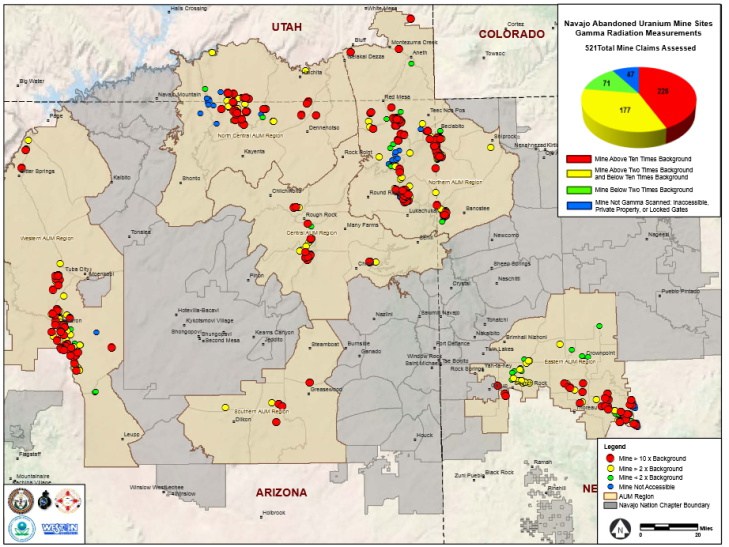

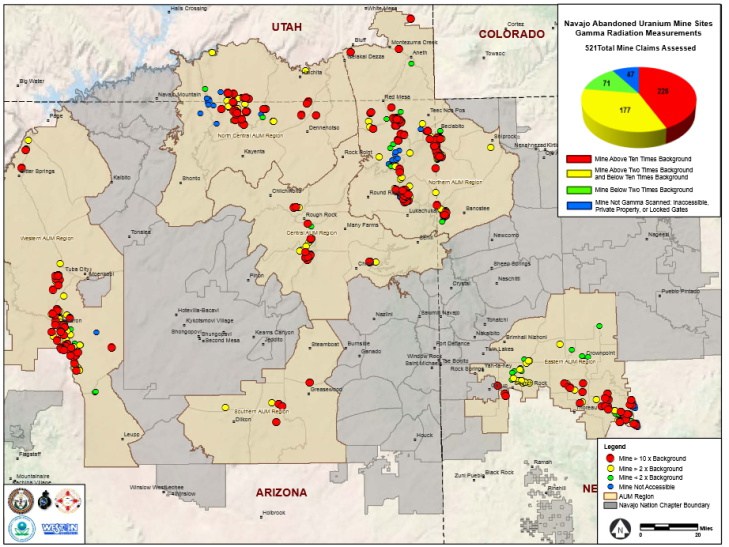

Cut to the present day. According to the US EPA, more than 500 of the existing 1300 abandoned uranium mines (AUM) on Navajo lands exhibit elevated levels of radiation.

Navajo abandoned uranium mines gamma radiation measurements and priority mines. US EPA

The Los Angeles Times gave us a sense of the risk in 1986. Thomas Payne, an environmental health officer from Indian Health Services, accompanied by a National Park Service ranger, took water samples from 48 sites in Navajo territory. The group of samples showed uranium levels in wells as high as 139 picocuries per liter. Levels In abandoned pits were far more dangerous, sometimes exceeding 4,000 picocuries. The EPA limit for safe drinking water is 20 picocuries per liter.

This unresolved plague of radiation is compounded by pollution from coal mines and a coal-fired power plant that manifests at an even more systemic level; the entire Navajo water supply is currently tainted with industry toxins.

Recent media coverage and spiraling public outrage over the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has completely eclipsed the ongoing environmental justice struggles of the Navajo. Even worse, the media continues to frame the situation in Flint as some sort of isolated incident.

Madeline Stano, attorney for the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, assessed the situation for the San Diego Free Press, commenting, “Unfortunately, Flint’s water scandal is a symptom of a much larger disease. It’s far from an isolated incidence, in the history of Michigan itself and in the country writ large.”

Other instances of criminally negligent environmental pollution in the United States include the 50-year legacy of PCB contamination at the Mohawk community of Akwesasne, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation (HNR) situated in the Yakama Nation’s “front yard.”

While many environmental movements are fighting to establish proper regulation of pollutants at state, federal, and even international levels, these four cases are representative of a pervasive, environmental racism that stacks up against communities like the Navajo and prevents them from receiving equal protection under existing regulations and policies.

Despite the common thread among these cases, the wave of righteous indignation over the ongoing tragedy in Flint has yet to reach the Navajo Nation, the Mohawk community of Akwesasne, the Yakama Nation – or the many other Indigenous communities across the United States that continue to endure various toxic legacies in relative silence.

Current public outcry may be a harbinger, however, of an environmental justice movement ready to galvanize itself towards a higher calling, one that includes all peoples across the United States, and truly shares the ongoing, collective environmental victories with all communities of color.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 10, 2012 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling

By Uranium Network

A foreign uranium mining conglomerate will be allowed to exploit the precious Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania after the World Heritage Committee (WHC) decided, at its July 2012 session in Russia, to accept what was described as a “minor boundary change” of the site. The change had been requested by the Government of Tanzania, in order to make way for the development of a major uranium mine, Mkuju River Uranium Project, owned by Russian ARMZ and Canadian Uranium One.

The decision to allow the boundary change would allow the Mkuju River uranium project, situated in the South of the Selous Game Reserve at its transition to the Selous Niassa Wildlife Corridor, to go forward.

The Tanzanian Government lobbied heavily for the boundary change, after declaring its intent to ” win the battle” against the UNESCO WHC.

Dozens of environmental groups around the world, many of them members of the German-based Uranium Network, decried the WHC decision which could lead to the creation of 60 million tons of radioactive and poisonous waste by the mine during its 10-year lifespan (139 million tons if a projected extension of the mine should be implemented). The radioactive wastes pose a serious threat to Selous Game Reserve which is home to the world’s largest elephant population and other wildlife. No proven methods exist to keep the radioactive and toxic slush and liquids from seeping into surface waters, aquifers or spreading with the dry season wind into the Reserve.

It remains completely unclear how the company or the Government of Tanzania will guarantee that the impact of millions of tons of radioactive and toxic waste will be “limited”. The WHC decision appears to be influenced by heavy corporate and government lobbying and not by sound science. It sets a horrible precedent that could threaten other World Heritage Sites with similar dangerous and damaging exploitation.

The decision is in stark contrast to previous decisions of the WHC of 2011 stating that mining activities would be incompatible with the status of Selous Game Reserve, a World Heritage site.

The environmental groups question whether WHC members have fully understood and given adequate attention to the implications of a uranium mine – including diesel generators, uranium mill, housing, heavy truck roads, as well as the creation of millions of tons of radioactive and toxic waste which should be contained safely and separate from the environment for thousands of years.

Uranium mining creates radioactive dust, contaminates waterways and groundwater aquifers and depletes often precious water supplies. Once abandoned, the radioactive contamination from the mines can persist for decades or even hundreds of years.

The WHC’s decision was made at a time when Russia was chairing the WHC session in St. Petersburg, Russia; Mkuju River uranium project – which basically lives or dies with the decision on the boundary change – is majority owned by Russian ARMZ, a subsidiary of ROSATOM – who bought it from Australian Mantra Resources earlier in 2012.

The environmental groups urge the World Heritage Committee to reconsider its decision on the Selous Game Reserve Boundary Change and call upon the Government of Tanzania to refrain from licensing a uranium mine in Selous Game Reserve or on lands cut out from it.

From Hamsayeh.net:

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 14, 2012 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, The Solution: Resistance

By Ahni / Intercontinental Cry

The Cree Nation of Mistissini has made their position clear. They are unequivocally opposed to any uranium development in Eeyou Istchee (Cree for “The People’s Land”).

On June 5, Chief Richard Shecapio carried the words of his community to a Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) public hearing in Mistissini, Quebec.

“We want to put an end to the question of uranium development once and for all, right now. We know where this is going and we don’t want any uranium mining at all”.

Those words will sound familiar to anyone keeping a close watch of the mining industry’s very Canadian adventures. Indeed, This is the third time in less than two years the Cree Nation has asserted its position.

That position isn’t going to change any time soon.

Chief Shecapio went on to explain that his Council will do “whatever it takes” to implement a moratorium on uranium development. “In light of the lack of social acceptability, cultural incompatibility and the lack of a clear understanding of the health and environmental impacts of uranium mining, it would be reckless for us as a people to move forward and allow the licensing of Strateco’s advanced exploration project. We are seeking a moratorium on uranium mining and exploration on our traditional lands as well as in the province of Quebec”, said Chief Shecapio.

Strateco Resources Inc. is trying to establish an underground exploration program at its Matoush Project in northern Quebec. The recent CNSC hearing was in regards to the company’s application for a license to go ahead with the exploration program.

Chief Shecapio continued, the Cree Peoples “have always been the guardians and protectors of the land and will continue to be. For the Crees of Mistissini, the land is a school of its own and the resources of the land are the material and supplies they need. Cree traplines are the classrooms. What is taught on these traplines to the youth is the Cree way of life, which means living in harmony with nature. This form of education ensures our survival as a people. Any form of education that leads to survival is a high standard of education. Cree form of education teaches us to be humble, respectful, responsible, disciplined, independent, sharing and compassionate”.

“Because our people are still active on the land, hunting, trapping and consuming the animals, we are concerned that traditional foods may become contaminated with radionuclides, posing a threat to those who eat them. High levels of radionuclides in moose and caribou tissues have been reported in animals near uranium mines. This indirect exposure can lead to serious health issues for the people who eat contaminated animals”, expressed Chief Shecapio.

The CNSC maintains a very different perspective on the matter. The Commission, which is supposedly in charge of protecting “the health, safety and security of Canadians as well as the environment” asserts that Strateco’s project is low risk.

Government officials in India and Tanzania said the same thing about uranium development projects there, and, well, look how that turned out.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter. As long as the Cree Nation of Mistissini remains steadfast and their support-base grows, the project will undoubtedly be put to rest.

When it comes to uranium, even “low risk” is too much risk.

From Intercontinental Cry: http://intercontinentalcry.org/cree-first-nation-wholly-rejects-uranium-exploration/