by DGR News Service | Oct 2, 2023 | Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Protests & Symbolic Acts

Editor’s Note: We bring to you a combination of two posts. The first is about a mass arrest of activists during climate protests on September 18. The protests were part of a global coordinated climate action. The second is about the new permits issued in the US for offshore oil drilling. For a president who ran his election on not allowing any more drillings, the move is a shift from his electoral promises. Though reflecting a lack of integrity, it still does not come as a surprise. Both the Democratic and Republican parties have shown, time and again, to favor corporations over nature, people, justice and freedom. This crackdown on protestors and permission for new drilling projects are just a reflection of that. As much as we oppose fossil fuels and oil drilling, DGR does not believe a renewable transition to be a solution to it. And calling a climate emergency to pursue that purpose would be folly.

114 Climate Defenders Arrested While Blocking Entry to NY Federal Reserve

By Brett Wilkins/Common Dreams

A day after tens of thousands of climate activists marched through Manhattan’s Upper East Side demanding an end to oil, gas, and coal production, thousands more demonstrators hit the streets of Lower Manhattan Monday, where more than 100 people were arrested while surrounding the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to protest fossil fuel financing.

Protesters chanted slogans like “No oil, no gas, fossil fuels can kiss my ass” and “We need clean air, not another billionaire” as they marched from Zuccotti Park—ground zero of the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement—to pre-selected sites in the Financial District. Witnesses said many of the activists attempted to reach the New York Stock Exchange but were blocked by police.

“We’re here to wake up the regulators who are asleep at the wheel as they continue to let Wall Street lead us into ANOTHER financial crash with their fossil fuel financing,” the Stop the Money Pipeline coalition explained on social media.

Protests against 300-mile-long oil pipeline through the Appalachians

Local and national media reported New York Police Department (NYPD) officers arrested 114 protesters and charged them with civil disobedience Monday after they blocked entrances to the Fed building. Most of those arrested were expected to be booked and released.

“I’m being arrested for exercising my First Amendment right to protest because Joe Manchin is putting a 300-mile-long pipeline through my home state of West Virginia and President [Joe] Biden allowed him to do it for nothing in return,” explained Climate Defiance organizer Rylee Haught on social media, referring to the right-wing Democratic senator and the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

As she was led away by an NYPD officer, a tearful Haught said Biden “sold us out.”

“He promised to end drilling on federal lands, and he’s selling out Appalachia’s future for profit,” she added.

The demand is: declare a climate emergency

Responding to the “block-long” line of arrestees, Climate Defiance asked: “Why are we getting handcuffed while people who literally torch the planet get celebrated for their ‘civility’ and their ‘moderation’?”

Alicé Nascimento of New York Communities for Change told WABC that the protests—which are part of Climate Week and are timed to coincide with this week’s United Nations Climate Ambition Summit—are “our last resort.”

“We’re bringing the crisis to their doorstep and this is what it looks like,” said Nascimento.

As they have at similar demonstrations, protesters called on Biden to stop approving new fossil fuel projects and declare a climate emergency. Some had a message for the president and his administration.

“We hold the power of the people, the power you need to win this election,” 17-year-old Brooklynite Emma Buretta of the youth-led protest group Fridays for Future told WABC. “If you want to win in 2024, if you do not want the blood of my generation to be on your hands, end fossil fuels.”

‘Gross Denial of Reality’: Biden Infuriates With Approval of More Offshore Drilling

By Julia Conley/Common Dreams

Rejecting the corporate media’s narrative that U.S. President Joe Biden’s newly-released offshore drilling plan includes the “fewest-ever” drilling leases, dozens of climate action and marine conservation groups on Friday said the president had “missed an easy opportunity to do the right thing” and follow through on his campaign promise to end all lease sales for oil and gas extraction in the nation’s waters.

The U.S. Interior Department announced Friday its five-year plan for the National Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, including three new areas in the Gulf of Mexico where fossil fuel companies will be permitted to drill.

Government won’t reach it’s climate goals whith new drilling leases

Biden promised “no new oil drilling, period” as a presidential candidate, but he announced the plan six months after the administration’s approval of the Willow oil drilling project in Alaska incensed climate advocates.

The industries have already bought 9,000 drilling leases – to which the new leases will be added. This is “incompatible with reaching President Biden’s goal of cutting emissions by 50-52% by 2030,” said the Protect All Our Coasts Coalition, citing the findings of Biden’s own Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its Office of Atmospheric Protection earlier this year.

Texan citizens suffer under pollution in the Gulf region

While the final plan scales back from the eleven sales that were originally proposed, said the coalition, “the plan is a step backwards from the climate goals the administration has set and for environmental justice communities across the Gulf South, who are already experiencing the disproportionate impact of fossil fuel extraction across the region.”

The coalition includes the Port Arthur Community Action Network, which has called attention to the risks posed to public health in the Gulf region by continued fossil fuel extraction.

“Folks in Port Arthur, Texas die daily from cancer, respiratory, heart, and kidney disease from the very pollution that would come from more leases and drilling,” said John Beard, the founder, president, and executive director of the group. “If Biden is to truly be the environmental president, he should stop any further leasing and all forms of the petrochemical build-out, call for a climate emergency, and jumpstart the transition to clean green, renewable energy, and lift the toxic pollution from overburdened communities.”

Our fossil fuel-lifestyle incompatible with the survival of the earth

Kendall Dix, national policy director of Taproot Earth, dismissed political think tanks that applauded the “historically few lease sales” on Friday.

“The earth does not recognize political ‘victories,'” said Dix, pointing to an intrusion of saltwater in South Louisiana’s drinking water in recent weeks, which has been exacerbated by the fossil fuel-driven climate crisis.

“As the head of the United Nations [António Guterres] has said, continued fossils fuel development is incompatible with human survival,” he added. “We need to transition to justly sourced renewable energy that’s democratically managed and accountable to frontline communities as quickly as possible.”

Biden’s drilling plans break his campaign promises

Along with groups in the Gulf region, national organizations on Friday condemned a plan that they said blatantly ignores the repeated warnings of international energy experts and the world’s top climate scientists who say no new fossil fuel expansion is compatible with a pathway to limiting planetary heating to 1.5°C.

“Sacrificing millions of acres in the Gulf of Mexico for oil and gas extraction when scientists are clear that we must end fossil fuel expansion immediately is a gross denial of reality by Joe Biden in the face of climate catastrophe,” said Collin Rees, United States program manager at Oil Change International. “Doubling down on oil drilling is a direct violation of President Biden’s prior commitments and continues a concerning trend.”

Rees noted that 75,000 people marched in New York City last week to demand that Biden declare a climate emergency and end support for any new fossil fuel extraction projects.

Protesters fear the destruction of land based communities and wildlife

“End Fossil Fuels is pretty clear,” said Rees, referring to campaigners’ rallying cry. “Not ‘hold slightly fewer lease sales,’ not ‘talk about climate action’—End. Fossil. Fuels.”

Despite Biden’s campaign promises, Rees noted, the U.S. is currently “on track to expand fossil fuel production more than any other country by 2050.”

“I feel disgusted and incredibly let down by Biden’s offshore oil drilling plan. It piles more harm on already-struggling ecosystems, endangered species and the global climate,” said Brady Bradshaw, senior oceans campaigner at the Center for Biological Diversity, another member of the Protect All Our Coasts Coalition. “We need Biden to commit to a fossil fuel phaseout, but actions like this condemn us to oil spills, climate disasters, and decades of toxic harm to communities and wildlife.”

Inflation Reduction Act serves industrial extension

The lease sales, said Sarah Winter Whelan of the Healthy Ocean Coalition, also represent a missed opportunity by the administration to treat the world’s oceans “as a climate solution, not a source for further climate disaster.”

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, negotiated by the White House last year, the government is required to offer at least 60 million acres of offshore gas and oil drilling leases before developing new wind power projects of similar scope.

“A single new lease sale for offshore oil and gas exploration is one too many,” said Whelan. “Communities around the country are already dealing with exacerbating impacts from climate disruption caused by our reliance on fossil fuels. Any increase in our dependence on fossil fuels just bakes in greater impacts to humanity.”

Gulf communities, added Beard, “refuse to be sacrificed” for fossil fuel profits.

“We say enough is enough,” he said.

by DGR News Service | Sep 11, 2023 | ACTION, The Problem: Civilization

Wednesday, September 6, 2023

“Violence on the Land is Violence on our Bodies”: Appalachian Frontline Women’s Divestment Delegation Highlights Dangers of Mountain Valley Pipeline in Meeting with UBS Bank

Joint press release with Divest Invest Protect and The Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International

SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA, California— On September 6, a delegation of frontline women leaders from Appalachia and advocates met with UBS Bank to highlight concerns of human rights violations along the Mountain Valley Pipeline, as well as environmental harms in the Appalachian region as a result of the pipeline.

During the meeting, the Appalachian Frontline Women’s Divestment Delegation provided testimony and shared stories, data and research on the multiple ways that the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) and its construction pose a serious threat to communities, water, air quality and the global climate.

Originally expected to be completed in 2018, the MVP Mainline now runs five years behind schedule and $3 billion over budget. UBS Bank is one of the banks financing MVP, and during the meeting, delegates highlighted that since the project’s inception, the joint owners of Mountain Valley Pipeline have sustained financial losses. In May, 2022, RGC Resources, parent company of Roanoke Gas, disclosed a $29.6 million impairment charge on MVP. Similarly, NextEra announced an $800 million loss in February, 2022, and stated that it was reevaluating its investment in MVP. Additionally, Mountain Valley LLC has incurred millions in fines and settlements for environmental violations and billions of dollars’ worth of expenses in legal battles, permit negotiations, and costly construction delays.

Delegation members provided eye witness accounts and detailed information about specific impacts Indigenous communities and communities of color face in regards to the construction and operation of MVP. The pipeline route will go through Black, Indigenous, Latino, and low-income communities across Appalachia who would experience the brunt of environmental injustice. According to the company’s own 2017 Final Environmental Impact Statement, elderly, disabled, poor, and medically underserved residents are over-represented in the path of the project. Pollution caused by pipelines and methane gas infrastructure has been linked to several adverse health effects, including respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. The racial inequities that will ensue from the MVP construction route are so indisputable that the Virginia Air Pollution Control Board denied an air permit on environmental justice grounds. Additionally, construction of MVP has already damaged sacred sites on the homeland of the Monacan Indian Nation, Occaneechi, Saponi, and Tutelo tribes, including a burial mound near Roanoke, Virginia, which dates back several thousand years.

In June 2023, a provision in the Fiscal Responsibility Act approved all remaining permits for the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Another provision stripped the judiciary of any authority to assess the legality of the permits, and therefore opportunity for challenges and input from local communities, forcing the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals to dismiss two long-standing legal challenges against the MVP that had been staving off construction for years. Construction is now moving forward on the MVP Mainline following Congressional intervention deemed unconstitutional by well-regarded legal scholars.

Delegates shared research on how MVP can negatively impact local ecosystems and the global climate. Experts state that MVP will emit over 89 million metric tons of greenhouse gas pollution annually, equivalent to the pollution from 24 average US coal plants. The pipeline route will cut across over 1,000 waterways and harm the ecosystems of multiple species of concern, including six federally endangered or threatened species and an additional four state listed species. The pipeline will also run over terrain susceptible to landslides in an active seismic zone, raising concerns over pipeline ruptures and explosions. Delegates highlighted the August 2023 Notice of Proposed Safety Order by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) stating that conditions along the MVP may “pose a pipeline integrity risk to public safety, property, or the environment.”

The Appalachian Frontline Women’s Divestment Delegation, organized by the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) and Divest Invest Protect (DIP) includes: Dr. Crystal A Cavalier, Ed.D, MPA (Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation), Adjunct Professor and Co-Founder, 7 Directions of Service; Dr. Emily Satterwhite, Professor and Director of Appalachian Studies (Appalachian Resident); Crystal Mello, Community Organizer, POWHR (Appalachian Resident); Michelle Cook (Diné), Founder of Divest Invest Protect; with Osprey Orielle Lake, Founder and Executive Director of Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN).

“Violence on the land is violence on our bodies. MVP is literally a death sentence for many in our communities and region, threatening our health and livelihoods. Our communities are disproportionately burdened with health hazards through policies and practices that force us to live near sources of toxic waste, such as pipelines, sewage works, mines, landfills, power stations, compressor stations, major roads, and emitters of airborne particulate matter. As a result, our communities suffer higher rates of health problems attendant on hazardous pollutants.” Dr. Crystal A Cavalier, Ed.D, MPA (Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation), Adjunct Professor and Co-Founder, 7 Directions of Service

“Mountain Valley Pipeline, a fly-by-night LLC is incapable of construction in compliance with environmental laws. MVP’s leadership clearly has no idea what they’re doing— but that hasn’t stopped them from rushing to place corroded and defective pipes in our land and water before PHMSA’s Notice of Proposed Safety Order can take effect. MVP is putting our lives at risk and then prosecuting us in the courts for trying to protect ourselves.” – Dr. Emily Satterwhite, Professor and Director of Appalachian Studies (Appalachian Resident)

“We’ve been devastated by the forward progress of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. We’re being sacrificed and it’s hard to imagine at times that this is even real. We’re literally in the fight for our lives – The struggle for my home, the struggle for clean air and water, the struggle for the planet, it’s a constant stresser in my life and in the lives of others in my community. We’ll never give up on protecting our home.” Crystal Mello, Community Organizer, POWHR (Appalachian Resident)

“The Appalachian Mountains, the oldest mountains in the world, her peoples, and countless other species, are under an urgent threat from the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP). We call for everyone to listen to the Mountains; the river’s babbling brook; the Fish; the Black Bear; the Hell Bender; and Falcon, and even the stones. Life itself cries out for urgent intervention against risks of fire and catastrophic explosions; their siren song sings screaming, Stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Our peoples of Appalachia were not created to be sacrificed to their altars of money and profit. Our peoples of Appalachia were not created to serve corporate extractivists agendas that destroy our bodies, health, water, and lands. We will protect our Mother the Mountain and we will protect one another. Our Mother the Mountain, she who is worthy of adoration and defense. The berry jewels of her forests, her glittering crystal silver waters, her golden harvests of grain and corn. She provides all we need for eternity and only requires respect for this opulence. UBS in this historic moment needs to do their due diligence to prevent risks relating to their financing; to respect internationally recognized human rights obligations to both people, planet, and the earth’s biodiversity.” – Michelle Cook (Diné), Founder of Divest Invest Protect

“The Mountain Valley Pipeline will have disastrous impacts for frontline communities who will experience the worst of fossil fuel pollution, for biodiverse species whose very habitats will be destroyed, and for our global climate which cannot take another pipeline project. It is time to end the era of fossil fuels for the health of our communities and planet. We must stop the very worst of the climate crisis before it is too late. We are calling for financial institutions to listen to communities and science, conduct thorough due diligence, and stop the harms of fossil fuel extraction. UBS and other banks have an opportunity to be leaders in the just transition by divesting from fossil fuels and instead financing projects that support the well-being of communities, ecosystems, and our planet. Now is the time for financial institutions to firmly respect international human rights standards and climate agreements as we collectively move towards a clean, just, and healthy future for all. There is no time to lose!” – Osprey Orielle Lake, Founder and Executive Director of Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN)

MEDIA CONTACT

Katherine Quaid, WECAN International, katherine@wecaninternational.org

Michelle Cook, Divest Invest Protect, divestinvestprotect@gmail.com

This press release is also available online.

Photo by Elijah Mears on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Apr 21, 2023 | ANALYSIS, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling

Editor’s Note: Mainstream environmental organizations propose electric vehicles (EVs) as a solution to every environmental crisis. It is not only untrue, but a delusion. It does not matter to the hundreds of lives lost whether they were killed for extraction of fossil fuel for traditional internal combustion (IC) cars, or for extraction of materials necessary for manufacturing EVs. What matters is that they are dead, never to come back, and that they died so a portion of humans could have convenient mobility. DGR is organizing to oppose car culture: both IC and EVs.

By Benja Weller

I am a rich white man in the richest time, in one of the richest countries in the world (…)

Equality does not exist. You yourself are the only thing that is taken into account.

If people realized that, we’d all have a lot more fun.

ZDF series Exit, 2022, financial manager in Oslo,

who illegally traded in salmon

Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn

Vor uns liegt ein weites Tal

Die Sonne scheint mit Glitzerstrahl

(We drive drive drive on the highway

Ahead of us lies a wide valley

The sun shines with a glittering beam)

Kraftwerk, Single Autobahn / Morgenspaziergang, 1974

Driving a car is a convenient thing, especially if you live in the countryside. For the first time in my life I drive a car regularly, after 27 years of being “carless”, since it was left to me as a passenger. It’s a small Suzuki Celerio, which I call Celery, and fortunately it doesn’t consume much. Nevertheless, I feel guilty because I know how disturbing the engine noise and exhaust fumes are for all living creatures when I press the gas pedal.

So far, I have managed well by train, bus and bicycle and have saved a lot of money. As a photographer, I used to take the train, then a taxi to my final destination in the village and got to my appointments on time. Today, setting off spontaneously and driving into the unknown feels luxurious.

However, my new sense of freedom is in stark contrast to my understanding of an intact environment: clean air, pedestrians and bicyclists are our role models, children can play safely outside. A naive utopia? According to the advertising images of the car industry, it seems as if electric cars are the long-awaited solution: A meadow with wind turbines painted on an electric car makes you think everything will be fine.

“Naturally by it’s very nature.” says the writing on an EV of the German Post, Neunkirchen, Siegerland (Photo by Benja Weller)

In Germany, the car culture (or rather the car cult) rules over our lives so much that not even a speed limit on highways can be achieved. The car industry has been receiving subsidies from the government for decades and journalists are ridiculed when they write about subsidies for cargo bikes.

Right now, this industry is getting a green makeover: quiet electric cars that don’t emit bad air and are “CO2 neutral” are supposed to drive us and subsequent generations into an environmentally friendly, economically strong future. On Feb. 15, 2023, the green party Die Grünen published in its blog that the European Union will phase out the internal combustion engine by 2035: “With the approval of the EU Parliament on Feb. 14, 2023, the transformation of the European automotive industry will receive a reliable framework. All major car manufacturers are already firmly committed to a future with battery-electric drives. The industry now has legal and planning certainty for further investment decisions, for example in setting up its own battery production. The drive turnaround toward climate-friendly vehicles will create future-proof jobs in Europe.”

That’s good news – of course for the automotive industry. All the old cars that will be replaced with new ones by 2035 will bring in more profit than old cars that will be driven until they expire. That the EU along with the car producers, are becoming environmentalists out of the blue is hard to believe, especially when you see what cars drive on German roads.

In recent years, a rather opulent trend became apparent: cars with combustion engines became huge in size and gasoline consumption increased, all in times of ecological collapse and global warming. These oversized SUVs are actually called sport-utility vehicles, even if you only drive them to get beer at the gas station. Small electric cars seem comfortable enough and have a better environmental footprint than larger SUVs. But the automotive industry is not going to let the new electromobility business go to waste that easily and is offering expensive electric SUVs: The Mercedes EQB 350 4matic, for example, which weighs 2.175 tons and has a 291-hp engine, costs €59,000 without deducting the e-car premium.

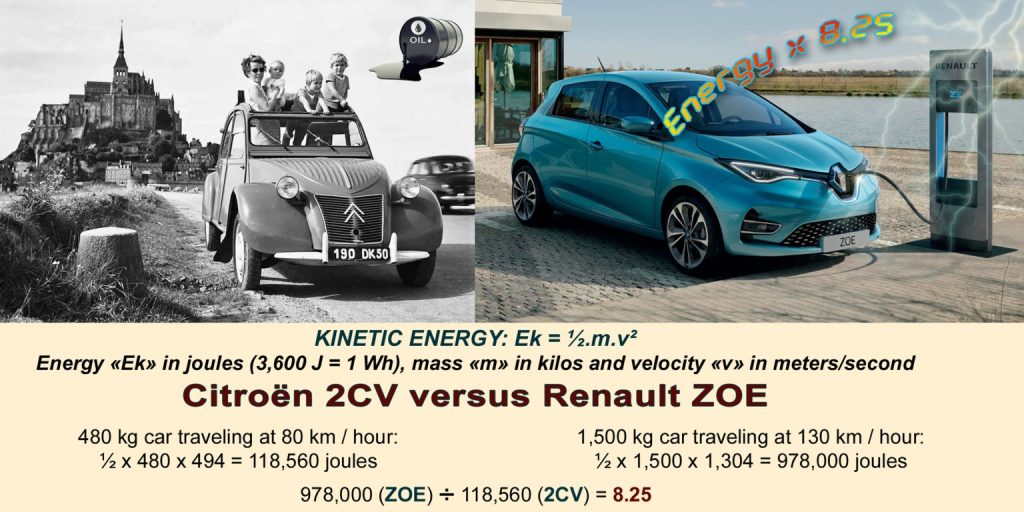

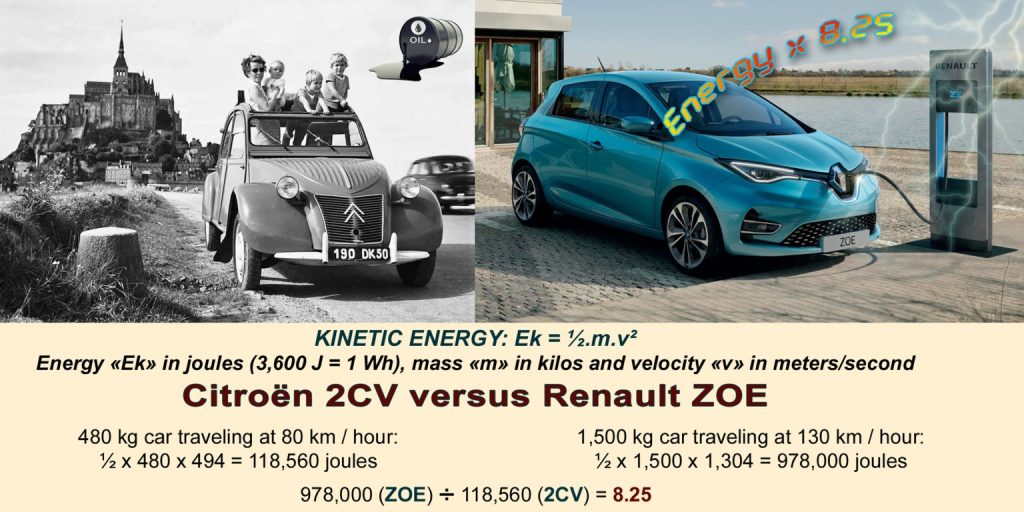

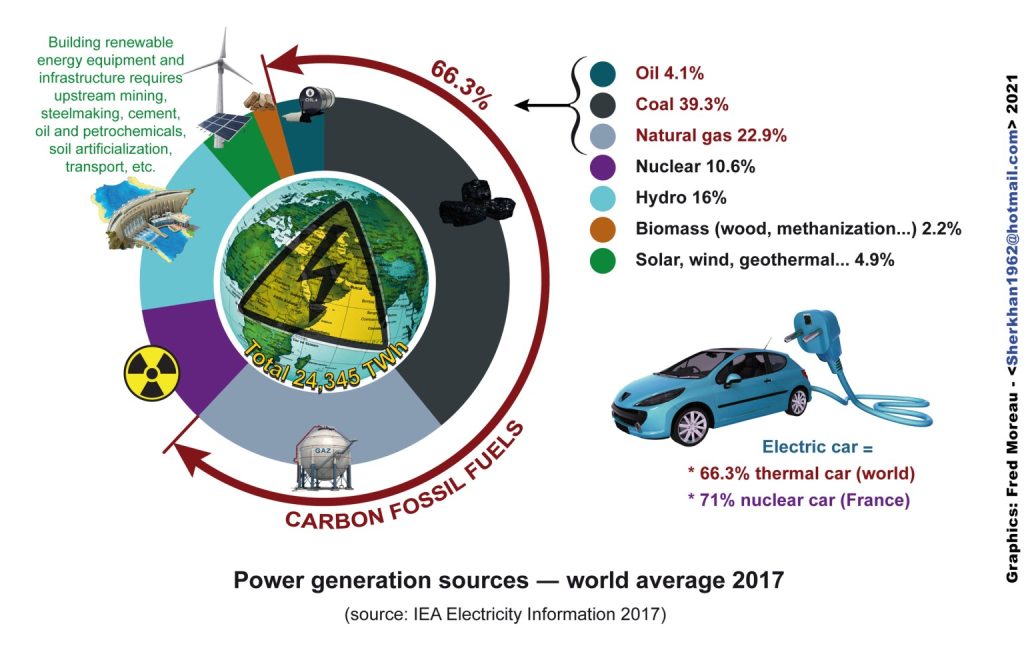

Comparing the Citroen 2CV and the Renault Zoe electric car shows that the Zoe uses about 8 times more kinetic energy. (Graph by Frederic Moreau)

If we look at all the production phases of a car and not just classify it according to its CO2 emmissions, the negative impact of the degradation of all the raw materials needed to build the car becomes visible. This is illustrated by the concept of ecological backpack, invented by Friedrich Schmidt-Bleek, former head of the Material Flows and Structural Change Department at the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy. On the Wuppertal Institute’s website, one can read that “for driving a car, not only the car itself and the gasoline consumption are counted, but also proportionally, for example, the iron ore mine, the steel mill and the road network.”

“In general, mining, the processing of ores and their transport are among the causes of the most serious regional environmental problems. Each ton of metal carries an ecological backpack of many tons, which are mined as ore, contaminated and consumed as process water, and weigh in as material turnover of the various means of transport,” the Klett-Verlag points out.

Car production requires large quantities of steel, rubber, plastic, glass and rare earths. Roads and infrastructure suitable for cars and trucks must be built from concrete, metal and tar. Electric cars, even if they do not emit CO2 from the exhaust, are no exception. Added to this is the battery, for which electricity is needed that is generated at great material expense, a never-ending cycle of raw material extraction, raw material consumption and waste production.

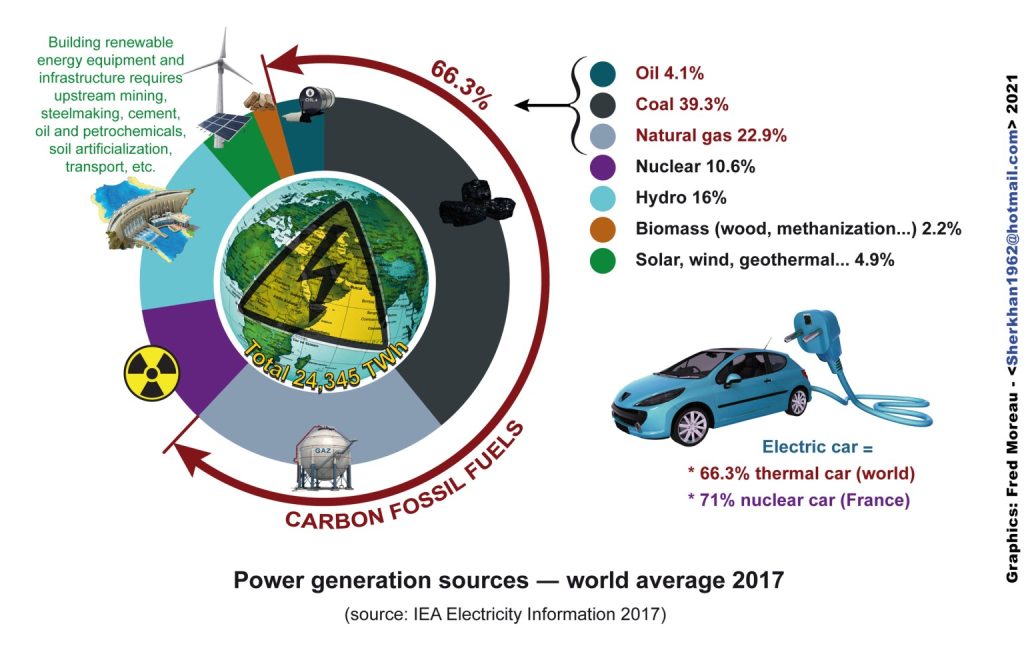

Power generation sources for electric vehicles (Graph by Frederic Moreau)

Lithium is a component of batteries needed for electric cars. For the production of these batteries and electric motors, raw materials are used “that are in any case finite, in many cases already available today with limited reserves, and whose extraction is very often associated with environmental destruction, child labor and overexploitation,” as Winfried Wolf writes in his book Mit dem Elektroauto in die Sackgasse, Warum E-Mobilität den Klimawandel beschleunigt (With the electric vehicle into the impasse, why e-mobility hastens climate change).

What happens behind the scenes of electric mobility, which is touted as “green,” can be seen in the U.S. campaign Protect Thacker Pass. In northern Nevada, a state in the western U.S., resistance is stirring against the construction of an open-pit mine by the Canadian company Lithium Americas, where lithium is to be mined. Here, a small group of activists, indigenous peoples and local residents have united to raise awareness of the destructive effects of lithium mining for electric car batteries and to prevent the lithium mine in the long term with the Protect Thacker Pass campaign.

Thacker Pass is a desert area (also called Peehee muh’huh in the native language of the Northern Paiute) that was originally home to the indigenous peoples of the Northern Paiute, Western Shoshone, and Winnemuca Tribes. The barren landscape is still home to some 300 species of animals and plants, including the endangered Kings River pyrg freshwater snail, jack rabbit, coyote, bighorn sheep, golden eagle, sage grouse, and pronghorn, and is home to large areas of sage brush on which the sage grouse feeds 70-75% of the time, and the endangered Crosby’s buckwheat.

For Lithium Americas, Thacker Pass is “one of the largest known lithium resources in the United States.” The Open-pit mining would break ground on a cultural memorial commemorating two massacres perpetrated against indigenous peoples in the 19th century and before. Evidence of a rich historical heritage is brought there by adjacent caves with burial sites, finds of obsidian processing, and 15,000-year-old petroglyphs. For generations, this site has been used by the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone tribes for ceremonies, traditional gathering and hunting, and educating young Native people. Now it appears that the history of the colonization of Thacker Pass is repeating itself.

According to research by environmental activists, the lithium mine would lower the water table by 10 meters in one of the driest areas in the U.S., as it is expected to use 6.4 billion gallons of water per year for the next 40 years. This would be certain death for the Kings River pyrg freshwater snail. Mining one ton of lithium generally consumes 1.9 million liters of water at a time when there is a global water shortage.

The mine would discharge uranium, antimony, sulfuric acid and other hazardous substances into the groundwater. This would be a major threat to animal and plant species and also to the local population. Their CO2 emissions would come up to more than 150,000 tons per year, about 2.3 tons of CO2 for every ton of lithium produced. So much for CO2-neutral production! Thanks to a multi-billion dollar advertising industry, mining projects are promoted as sustainable with clever phrases like “clean energy” and “green technology”.

About half of the local indigenous inhabitants are against the lithium mine. The other half are in favor of the project, hoping for a way out of financial hardship through better job opportunities. Lithium Americas’ announcement that it will bring an economic boost to the region sounds promising when you look at the job market there. But there’s no guarantee that working conditions will be fair and jobs will be payed well. According to Derrick Jensen, jobs in the mining industry are highly exploitative and comparable to conditions in slavery.

Oro Verde, The Tropical Forest Foundation, explains: “With the arrival of mining activities, local social structures are also changing: medium-term social consequences include alcohol and drug problems in the mining regions, rape and prostitution, as well as school dropouts and a shift in career choices among the younger generation. Traditional professions or (subsistence) agriculture are no longer of interest to young people. Young men in particular smell big money in the mines, so school dropouts near mines are also very common.”

Seemingly paradoxically, modern industrial culture promotes a rural exodus, which in turn serves as an argument for the construction of mines that harm the environment and people. Indigenous peoples have known for millennia how to be locally self-sufficient and feed their families independently of food imports. This autonomy is being repeatedly snatched away from them.

Erik Molvar, wildlife biologist and chair of the Western Watersheds Project, says of the negative impacts of lithium mining in Thacker Pass that “We have a responsibility as a society to avoid wreaking ecological havoc as we transition to renewable technologies. If we exacerbate the biodiversity crisis in a sloppy rush to solve the climate crisis, we risk turning the Earth into a barren, lifeless ball that can no longer sustain our own species, let alone the complex and delicate web of other plants and animals with which we share this planet.”

We share this planet with nonhuman animal athletes: The jack rabbit has a size of about 50cm (1.6 feet), can reach a speed of up to 60 km/h (37mph) and jump up to six meters (19.7 feet) high from a standing position. In the home of the jack rabbit, 25% of the world’s lithium deposits are about to be mined. To produce one ton of lithium, between 110 and 500 tons of earth have to be moved per day. Since lithium is only present in the clay rock in a proportion of 0.2-0.9%, it is dissolved out of the clay rock with the help of sulfuric acid.

According to the Environmental Impact Statement from the Thacker Pass Mine (EIS), approximately 75 trucks are expected to transport the required sulfur each day to convert it to sulfuric acid in a production facility built on site. This means that 5800 tons of sulfuric acid would be left as toxic waste per day. Sulfur is a waste product of the oil industry. How convenient, then, that the oil industry can simply continue to do “business as usual.”

Nevada Lithium, another company that operates lithium mines in Nevada states: “Electric vehicles (EVs) are here. The production of lithium for the batteries they use is one of the newest and most important industries in the world. China currently dominates the market, and the rest of the world, including the U.S., is now responding to secure its lithium supply.” The demand for lithium is causing its prices to skyrocket: Since the demand for lithium for the new technologies is high and the profit margin is 46% according to Spiegel, every land available will be used to mine lithium.

Lithium production worldwide would have to increase by 400% to meet the growing demand. With this insane growth rate as a goal, Lithium Americas has begun initial construction at Thacker Pass on March 02, 2023. But environmentalists are not giving up, they are holding meetings, educating people about the destructive effects of lithium mining, and taking legal action against the construction of the mine.

Let’s take a look at the production of German electric cars.

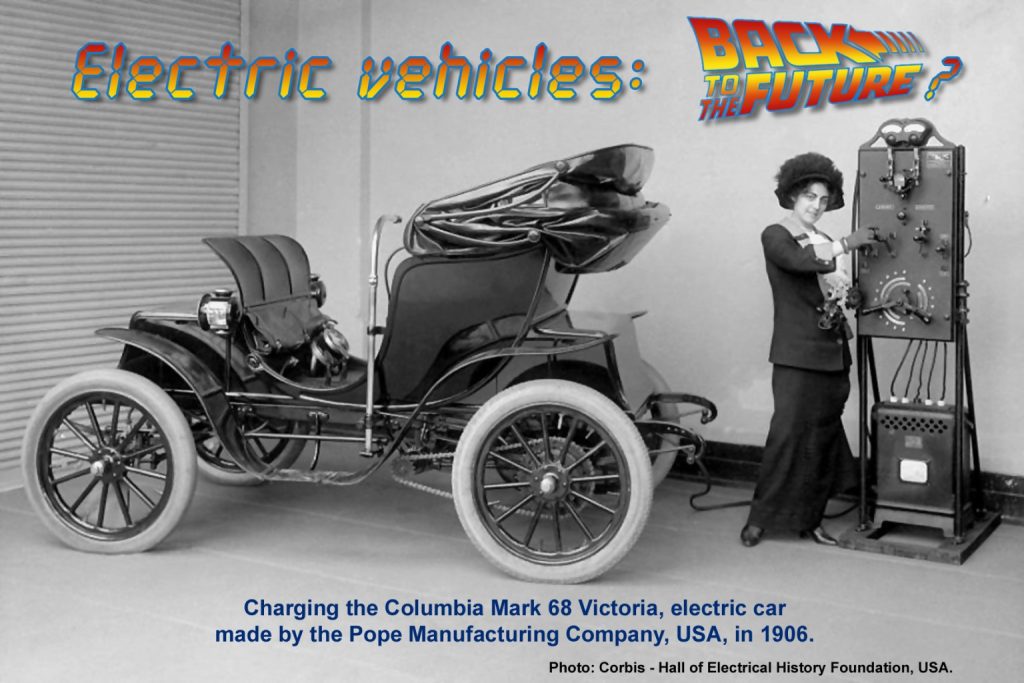

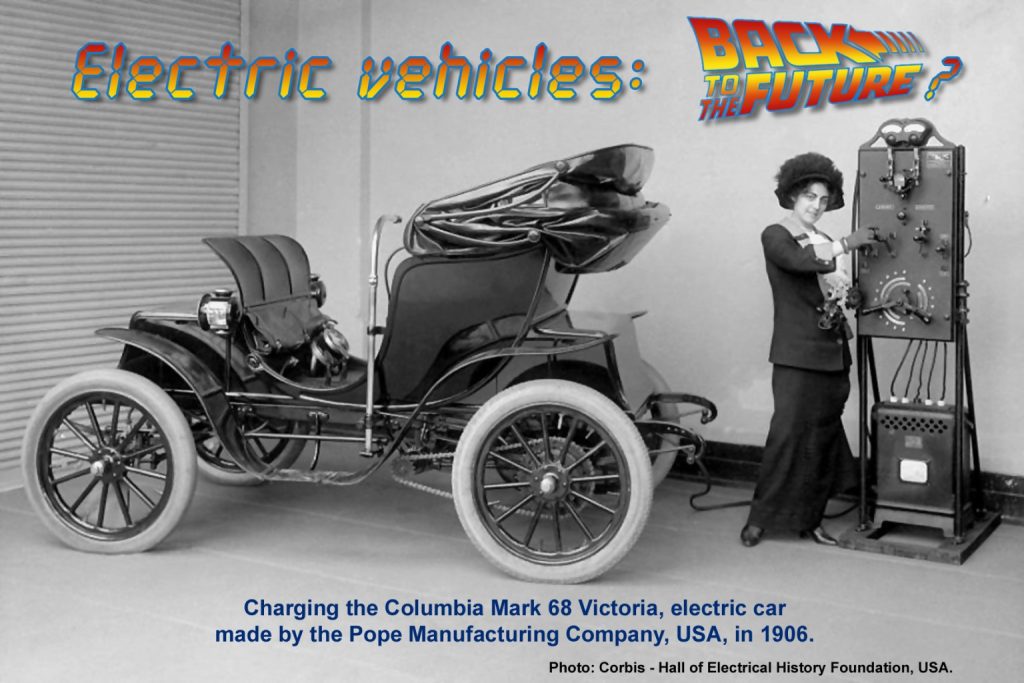

Meanwhile, this is the third attempt to bring electric cars to the market in Germany. In the early 20th century, Henry Ford’s internal combustion engine cars replaced electric-powered cars on the roads.

Graph by Frederic Moreau

“In fact, three decades ago, there were similar debates about the electric car as today. In 1991, various models of electric vehicles were produced in Germany and Switzerland,” writes Winfried Wolf. “At that time, it was firmly assumed that the leading car companies would enter into the construction of electric cars on a large scale.”

He goes on to write about a four-year test on the island of Rügen that tested 60 electric cars, including models by VW, Opel, BMW and Daimler-Benz passenger cars from 1992 to 1996. The cost was 60 million Deutsche Mark. The Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IFEU) in Heidelberg, commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Research, concluded that electric cars consume between 50 percent (frequent drivers) and 400 percent more primary energy per kilometer than comparable cars with internal combustion engines. The test report states that the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) in Berlin also sees its rejection of the electric car strategy confirmed.

There is no talk of these test results in times of our current economic crisis: also German landscapes and its water bodies must make way for a “green” economic policy. We can see the destructive effects of electric car production centers in the example of Grünheide, a town in Brandenburg 30 km from Berlin.

Manu Hoyer, together with other environmentalists in the Grünheide Citizens’ Initiative, rebel against the man who wants to discover life on other planets because the Earth is not enough: Elon Musk. She explains in an article by Frank Brunner in the magazine Natur how Tesla proceeded to build the Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg with supposedly 12,000 employees: First, they deforested before there was even a permit, and when it was clear that the electric car factory would be built, Tesla planted new little trees elsewhere as compensation.

The neutral word “deforestation” does not explain the cruel process behind it: Wildlife have their habitat in trees, shrubs and in burrows deep in the earth. In the Natur article, Manu Hoyer recalls that the sky darkened “with ravens waiting to devour the dead animals among the felled trees.”

In the book The Day the World Stops Shopping, J.B. MacKinnon describes, based on a study of clearing in Australia, that the scientific consensus is that the majority, and in some cases all, of the individuals living at a site will die when the vegetation disappears.

It doesn’t sound pretty, but it’s the reality when you read that animals are “crushed, impaled, mauled or buried alive, among other things. They suffer internal bleeding, broken bones or flee into the street where they are run over.” Many would stubbornly resist giving up their habitat.

In this, they are like humans. Nobody gives up her piece of land or his house without a fight when it is taken away from him; animals and humans both love the good life. But the conditions of wild animals play no role in our civil society, they should be available anytime to be exlpoited for our needs.

In order not to incite nature lovers, legal regulations are supposed to lull them into the belief that what is happening here is morally right. Behind this is a calculus by the large corporations, which in return for symbolic gestures can continue the terror against nature blamelessly.

In December 2022, Tesla was granted permission to buy another 100 hectares of forest to expand the car factory site to 400 hectares. The entire site had long been available for new industrial projects, although it is also a drinking water protection area. The Gigafactory uses 1.4 million cubic meters of water annually in a federate state plagued by drought.

Manu Hoyer tells Deutschlandfunk radio that dangerous chemicals are said to have leaked only recently and contaminated firefighting water seeped into the groundwater during a fire last fall. Another environmentalist, Steffen Schorcht, who studied biocybernetics and medical technology, criticizes local politicians for their lethargy in the face of environmental destruction. He sees no other way to fight back than to join forces with other citizens and international organizations outside of politics.

The beneficiaries are not the people who make up the bulk of the population. Tesla cars go to drivers who are happy to spend 57,000€ for a car with a maximum of 535 horsepower.

I can still remember how, as a child, I used to drive with my parents on vacation to the south of France, Italy or Austria in the Citroën 2CV model (two horsepower). Such a car trip was more adventure than luxury, but the experiences during the simple camping vacations in Europe’s nature have remained formative childhood memories.

The author sitting on the hood of a Citroën 2CV in Tuscany, Italy, 1989 (Photo: private)

Today, we have to go a big step further than just living a “simple life” individually. The car industry is pressing the gas pedal, taking the steering wheel out of our hands and driving us into the ditch. It’s time to get out, move our feet and stand up against the car industry.

The BDI, Federation of German Industries, writes in its 2017 position paper on the interlocking of raw materials and trade policy in relation to the technologies of the future that without raw materials there would be no digitalization, no Industry 4.0 and no electromobility. This statement confirms that our western lifestyle can only be financed through the destruction of the last natural habitats on Earth.

The mining of lithium and other so-called “raw materials” for new technologies is related to our culture, which imposes a techno-dystopia on the functioning organism Earth, that nullifies all biological facts. If we want to save the world, it seems to me, we should not become lobbyists for the electric car industry. Rather, we should organize collectively, learn from indigenous peoples, defend the water, the air, the soil, the plants, the wildlife, and everyone we love. The brave environmentalists in Grünheide and Thacker Pass are showing us how.

Homo sapiens have done well without cars for 200,000 years and will continue to do so. All we need is the confidence that our feet will carry us.

Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn, Kraftwerk buzzed at the time

as an ode to driving a car

I glide over the asphalt to the points in lonely nature,

give myself a time-out from the confines of the small town

Bus schedules in German villages are an old joke

Buy me a Mercedes Benz, cried Janis Joplin devotedly,

without an expensive car, life is only half as valuable

Car-free Sundays during the oil crisis as a nostalgic anecdote

Driving means freedom and compulsion at the same time, asphalt is forced upon topsoil

with millions of living beings per tablespoon of earth

You must go everywhere: To the supermarket, to school, to work, to the store,

to the club, to friends, and to the trail park

Be yourself! they tell you, but without a car you’re not yourself,

on foot with a lower social status than on wheels

The speed limit dismissed each time, which party stands for the wild nature,

our ancient living room? Don’t vote for them, they deceive too

Believe yourself! they say, but what else can you believe, grown up believing

that this civilization is the only right one

Drive, drive, drive and the airstream flies in your hair –

Freedom, the one moment you have left

Featured image: A view of Thacker Pass by Max Wilbert

by DGR News Service | Apr 3, 2023 | ANALYSIS, Listening to the Land

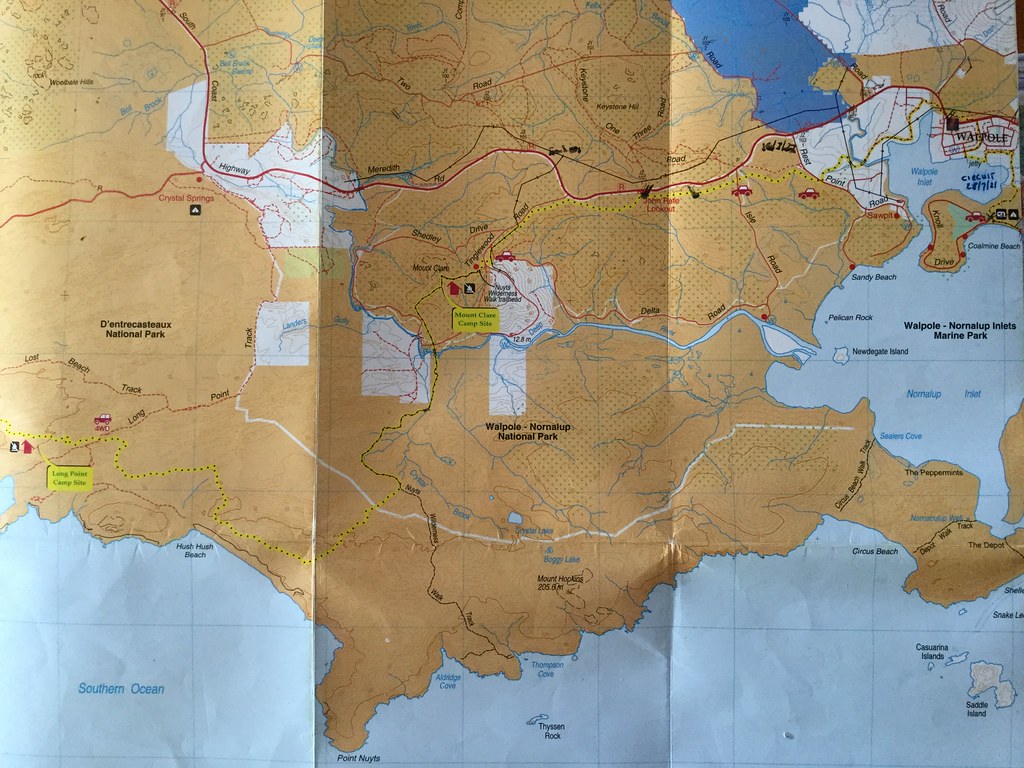

Editor’s Note: In the following piece, Sue Coulstock invites you in Nuyts Wilderness Walk. Along the journey, she shares her reflections on Australia’s colonial past, and the many nonhumans who call the wilderness their homes.

By Sue Coulstock

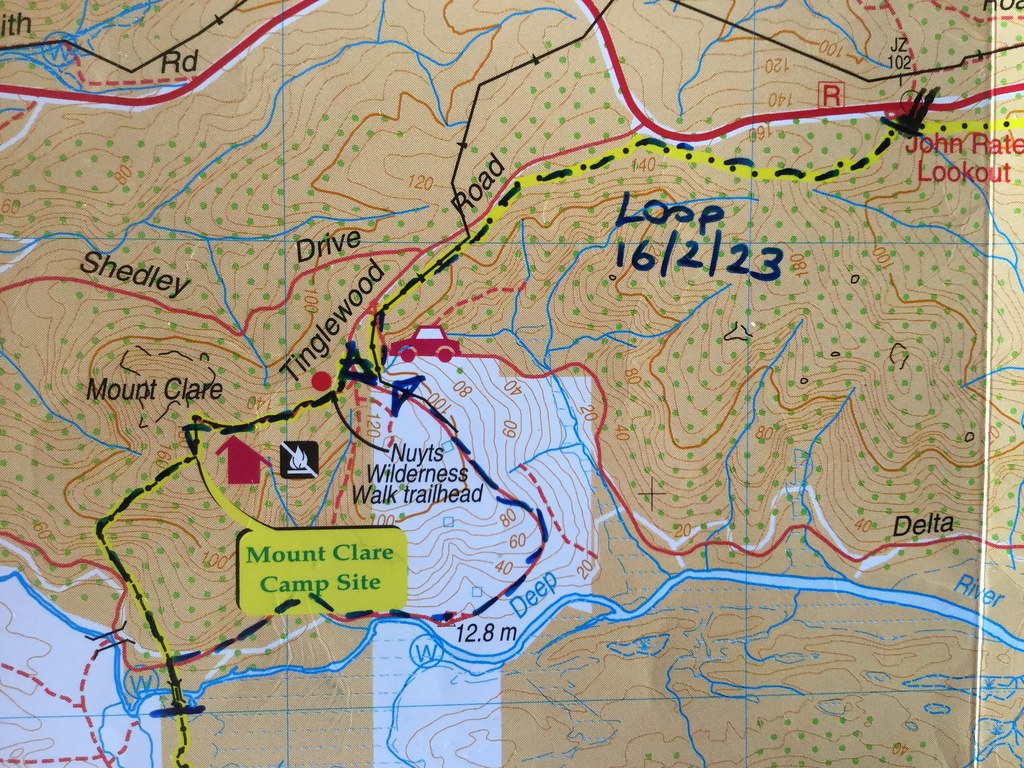

Recently we did an impromptu reconnaissance hike in a pocket of remnant old-growth Karri/Tingle forest, in preparation for doing the Nuyts Wilderness Walk for the first time later this Southern autumn. I’ve blogged our hikes for years to share with overseas friends and thought I’d share this one with fellow DGR people from all over the world. Many of you will be consciously limiting overseas travel, so I wanted to give you a vicarious walking experience in Australia with us.

As we were exhausted from working a bit too hard, we set out without a particular walk target, just to enjoy the forest and possibly have our lunch at the Mt Clare hut.

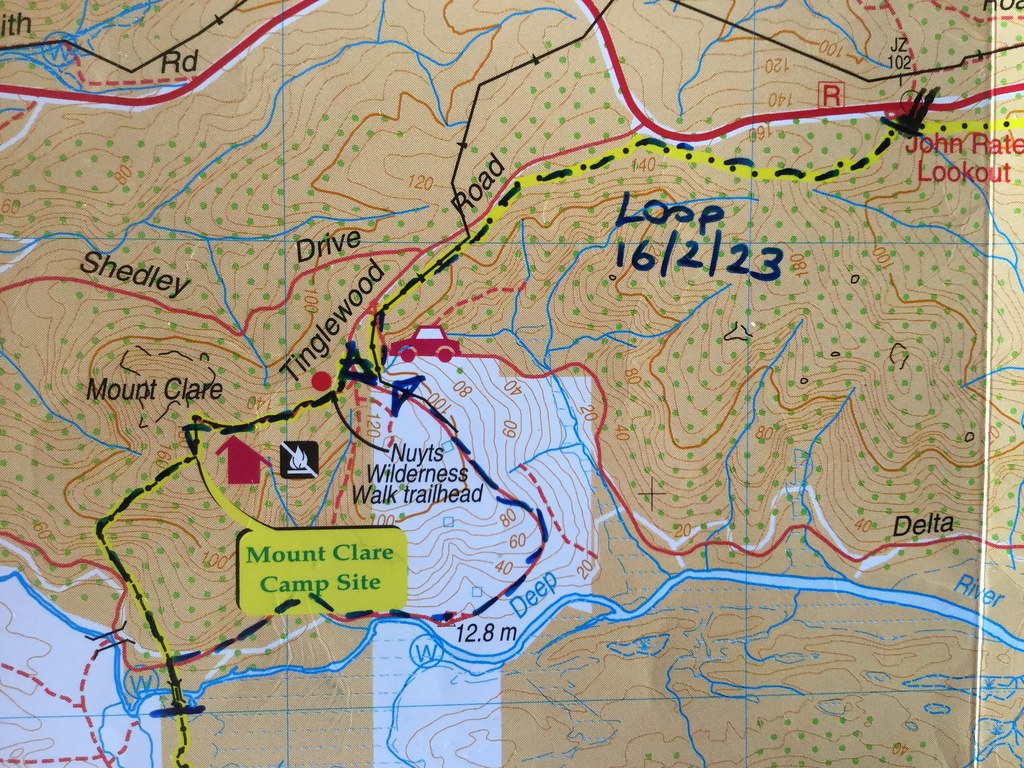

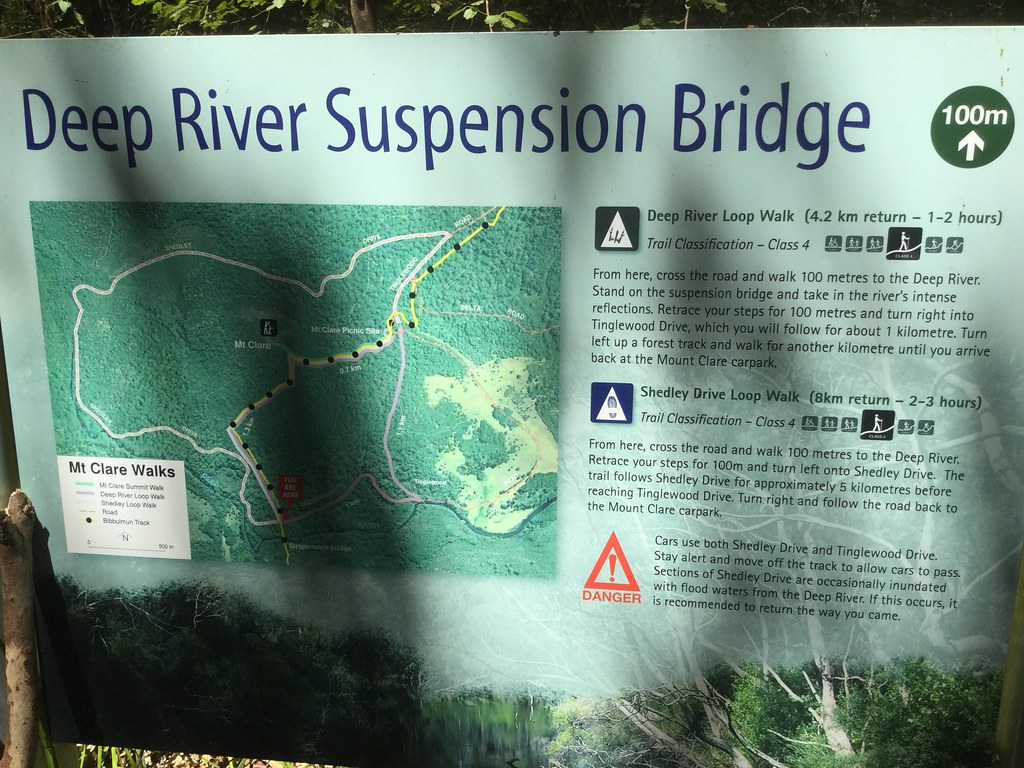

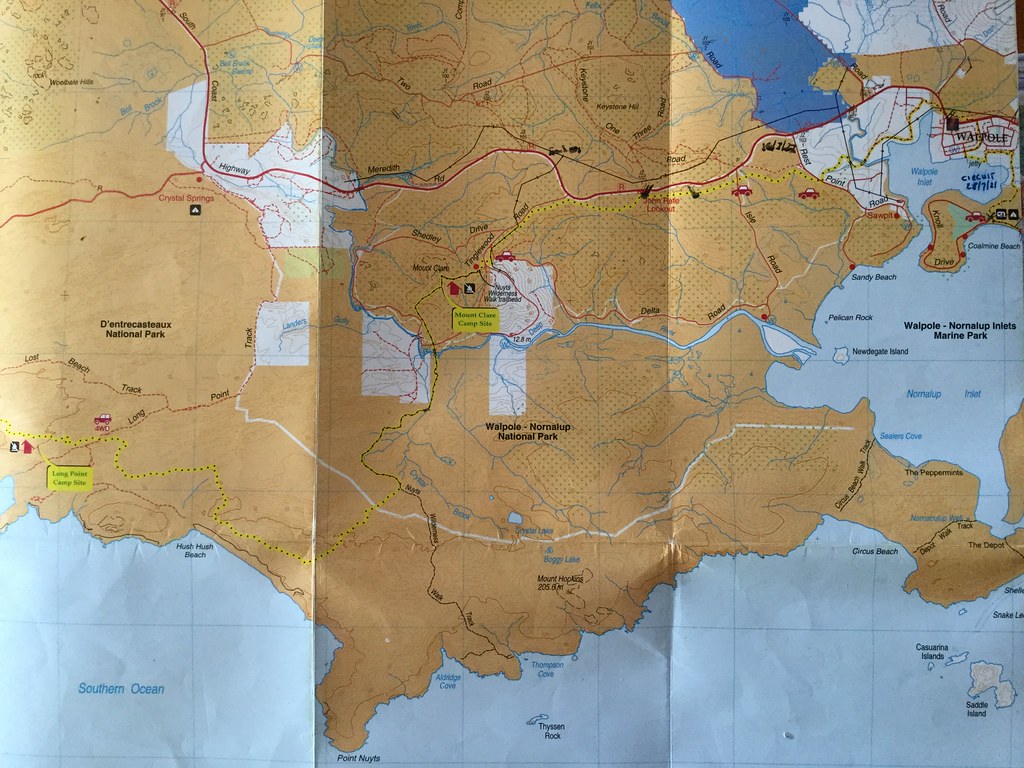

Here’s a context map of this special part of the world. There are no roads south of the Deep River; it’s walk-only. That situation is a little analogous to the amazing South Cape Bay Walk in Tasmania, where the road ends at Cockle Creek and from there you hike to the ocean – in that case, to the southernmost point of Tasmania.

There are sadly so few areas left in the world like this. We are such a terribly destructive culture. 250 years ago Australia was still unmarred by European civilisation and its large-scale annihilation of native ecosystems and cultures. Many people don’t think it’s even a problem. It’s not helped by the fact that Australia, like the US, has a highly urbanised population. Most Westerners essentially grow up in captivity and have little exposure to or understanding of natural ecosystems. I met kids in socially disadvantaged parts of London who had never seen a tree that hadn’t been planted by humans, and who didn’t even have an interest in such things. I went on a bush camp with privileged high schoolers from Sydney’s Northern Beaches who screamed when they saw insects and who immediately got out their pocket wet wipes when they got a bit of mud on their legs when we went hiking. They were ecstatic to get back to the shopping complexes that were their natural habitat. People can live and die entirely swallowed up in dystopia, so far from their roots as biological beings that they may as well live on a space station.

This is at the start of our walk at John Rate Lookout.

And we shall be your Hobbity guides today, so that if you live far across the seas, you can have a vicarious experience of this ancient ecosystem, which I shall do my level best to make vivid for you through photos and prose, so that hopefully you will be able to feel that part of you went walking with us.♥

There’s a boardwalk at the lookout with steps leading to the Bibbulmun track and a sign suggesting people walk into Walpole. We were heading in the other direction.

John Rate, perhaps unwittingly part of the machine that pulled down the Old Growth Forests, got a mention on this sign but I bet his much-feted understanding couldn’t have held a candle to the ecological understanding of the Noongar people who used to live in this forest. He’s celebrated for “discovering” a species of Tingle tree, as Captain Cook was celebrated for “discovering” Australia. It’s an odd way of looking at Australian history, to imagine people could have lived here for 60,000 years ignorant of this tree or of the continent beneath their feet.

You have to read the tourist information signs in the forest areas with a large grain of salt. It’s better to get into the forest and let it inform you.

Brett and I are so aware that urban and agricultural landscapes are terribly scarred and ecologically degraded, even the ones considered picturesque. It’s funny how the Western euphemism for degradation is “development” – I laughed when I heard a story about an Indigenous man from a rainforest saying, “What do you mean you want to develop this forest? It’s already developed – it took millions of years to get to this point!”

We treasure being able to immerse ourselves in relatively unspoilt areas, and to listen, with our bodies, minds and hearts, to what nature is saying to us. This is like coming home, on a fundamental level. It is like visiting a living cathedral, and learning about the respect and kinship you are supposed to have with the web of life. It is learning your place, which is as one species among many, and not as the alleged cream of creation, nor as the self-proclaimed pinnacle of evolution. It is learning about yourself as a biological being, walking for hours as your ancestors did on the African plains, down from the trees with hairless skin to help with evaporative cooling.

I’d not felt that energetic when I woke up that morning, and we had considered shorter walks even than the open-ended “John Rate Lookout to maybe Mt Clare hut if we can make it that far.” Yet we ended up walking for hours without committing to that in the first place, just because it was so magnificent to be in this forest.

Hollow spaces, nooks and crannies everywhere. The whole place teeming with life, despite the fact that we’ve tried to crush life out of these forests, and have significantly succeeded in doing so. I’d love to travel back in time 250 years and stand in this place, before this country took the dubious honour of having the worst rate of mammal extinctions in the world and people bulldozed entire ecosystems off the face of the earth.

One of the things nature teaches is that we’re all both eating, and becoming food for others in turn. The feathers of this Port Lincoln Ringneck Parrot were left behind after it became a meal for another creature. When its body has been through and partly become that creature, the expelled remains become food for decomposers and nutrition for plant roots. We are stardust and we go around and around to make this glorious diversity of life on earth with each other. Or at least we are supposed to.

Civilised humans on the other hand like to be at the end of every food chain, taking and taking, eating everything and never giving back, not even after death, when our bodies are nowadays typically either burnt to a cinder with the help of fossil fuels, or entombed in a box of furniture-grade wood (from the body of a tree) six feet under and far out of the reach of the soil organic layer where decomposition occurs and feeds a plethora of species including, finally, plants – but oh no, why should we give back? Why should we admit we’re part of all of this when we can pretend to be above it – above the web of life which birthed us? When we can make believe we are some superior being only owed and never owing, not a mere part of the biosphere but its appointed master and annihilator?

A song about world views…

It really is insane, all this crazy desperate need

For unknowable magic, strange supernatural power

You’re flying through space at a million miles an hour

For 4 billion years, the sun keeps coming up

It’s all too wonderful for words but for you it’s not enough

You should step out of the shadows yeah and step into the light

All too wonderful for words, but precious few in Western culture who truly see it and who deeply care for it. The astronomical things sketched in the song, or the beauty and intricacy of the biosphere – which for our society is primarily a resource to be exploited, not Life to be honoured. Your life is cheap, if you’re an ordinary citizen, as many have found out and are continuing to find out when push comes to shove; and it’s even cheaper if you’re some other being, especially if you’re not “cute” (i.e. big-eyed and rounded and resembling the human infant), or if you’re as visually and behaviourally different to Homo allegedly sapiens as a tree or a slime mould. To The Economy, you’re just a commodity, valued according to the money you can make someone else. It’s The Economy, stupid. There is no community – not a human community, not a biotic community – these things don’t matter, when push comes to shove; the best they get from the power structures of our society is lip service, pretence and equivocation.

From the time I was a young child and first disappeared into the wooded foothills of the Italian Alps with only a four-legged canine companion in the late 1970s, I felt embraced by the natural world, safe, welcome; and I felt an ever-increasing awe and love for it as I got to know it better. When I was an adolescent, I began to look through the microscope of biology, ecology, physiology, biochemistry, physics etc at the natural world, like Gulliver’s Travels to Brobdingnag where he was suddenly tiny and could see the world in much more detail than ever before; like a Fantastic Voyage into the bloodstream of the biosphere. My awe and love for the natural world continued to grow.

I still feel this embrace, and my inner response to it, every time I go out to where nature is still writ large and still breathing. From the time I was a child, I’ve touched branches and reeds on the sides of trails with affection, loved the aroma of leaves and flowers and of earth after rain (for which we can thank the actinomycetes), and liked to feel raindrops on my skin. I’ve delighted in the presence of ants, bees, dragonflies, ladybirds, butterflies, scrolly-antennaed moths, chirpy crickets, praying mantises. And that’s just some of the insects…if I were to enumerate other sources of delight in nature, I could fill volumes (and I have).

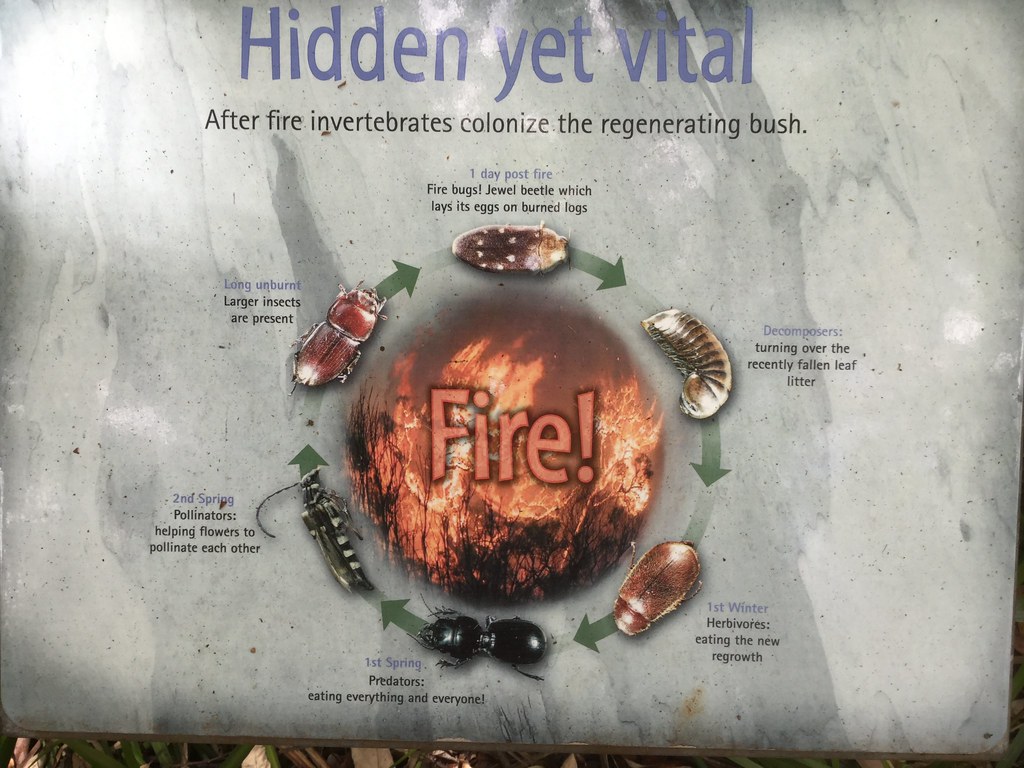

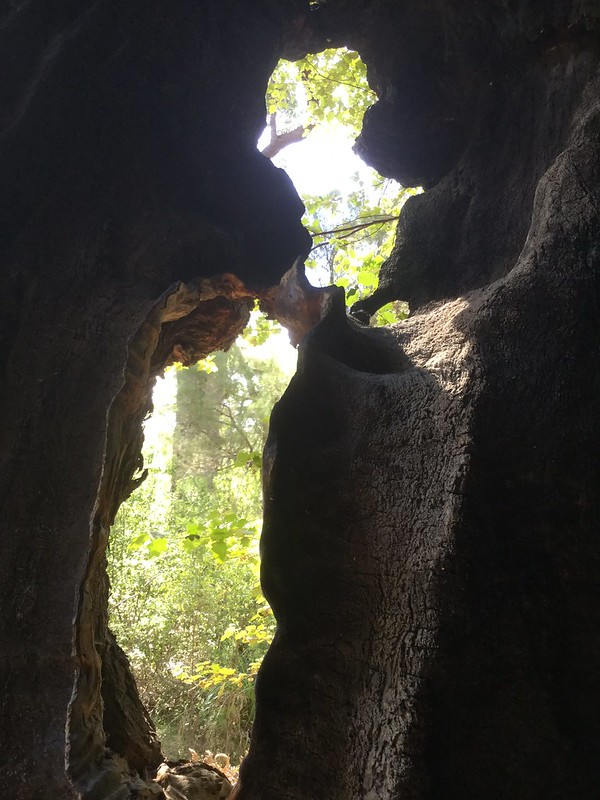

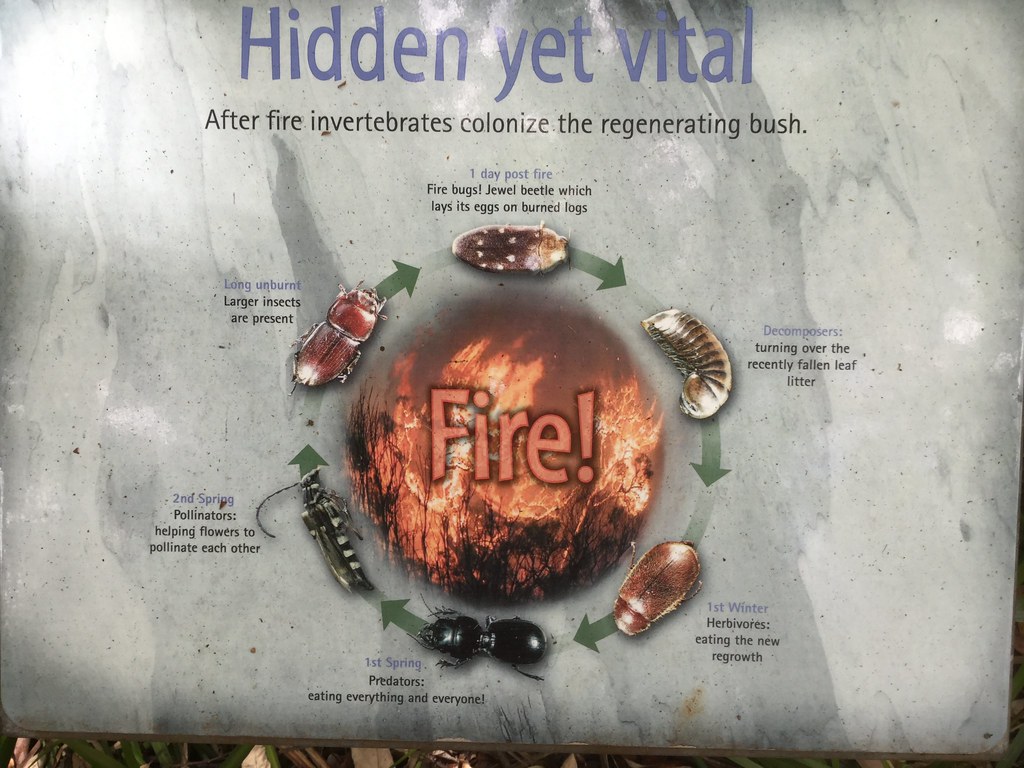

So let’s turn our attention to some of the special trees on this hike. Close to Walpole there are three species of Eucalyptus referred to as Tingles, which grow into veritable giants, especially in girth. Over the hundreds of years, a lot of them get their bases carved out by fire, which is a normal feature of sclerophyll vegetation such as we steward at Red Moon Sanctuary, and also, at longer intervals, of the eucalyptus forests in the higher-rainfall areas towards Walpole. Indigenous Australians prevented major wildfires with mostly cool-burning cultural burning practices, at the right times to reduce risk and encourage biodiversity, such as the plants and the animals they depended on for food. In a summer-dry ecosystem where microbial decomposition activity is seriously inhibited, the right fire at the right time (generally small-scale, cool, and near the start of reliable rains) can be a helpful tool for turning dry dead plant material into nutrient-rich ash, which gives a boost to soils, promotes new growth in plants and allows for spectacular flowering. It also gives a good start to the seedlings that have the space and light to grow when dry dead material is converted to ash. Good plant growth and flowering in turn benefits grazing and nectar-feeding animals.

Another benefit of fire is that it tends to create shelter and nesting hollows in the older trees and in fallen trunks, which benefit birds, mammals such a possums, insects, etc etc. In the bases of many old Tingle trees, these are more like caves!

The next photo has Brett standing in the base of the tree for scale.

Now I’m zooming in, and you may see him better!

Now we’re looking up at the tree.

There is rather too much of it to get even half of it into frame. Since we actually didn’t know we were going to do a walk we’d not done before when we set out in the morning, we didn’t take the good camera that usually accompanies us for documentation. These snaps were taken on an iPod, which is a bit limited and produces a bit of distortion, most notably in people photos.

Next, Brett spotted a bright orange bracket fungus with an unusual shape.

It’s probably a Curry Punk (Piptoporus australiensis). The guide book says “edibility unknown” and that made me recall an answer I got when I was little and asked which fungi you could eat, and was told, “You can eat all fungi, but some of them only once.”

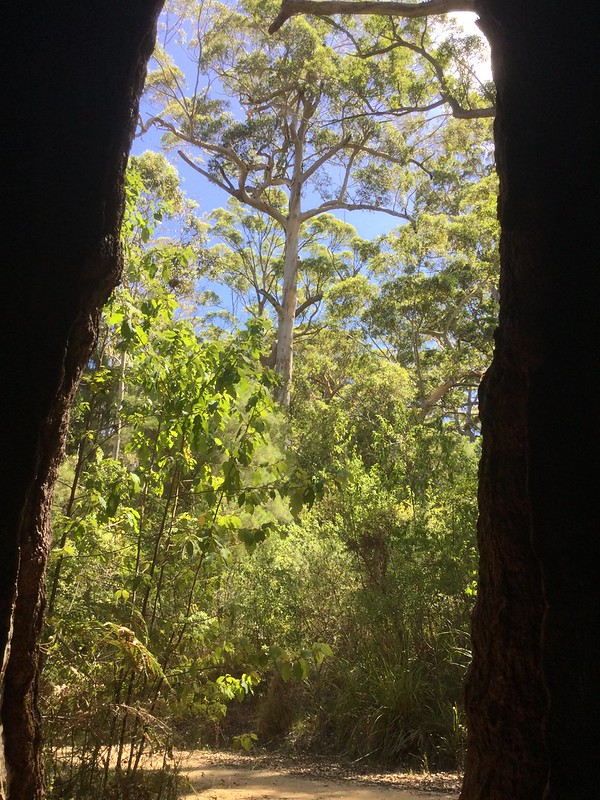

Since we knew people overseas or in cities would be interested, we took photos of quite a few different hollow Tingle-tree bases. (By the way, not all of them are hollow!)

So here’s another.

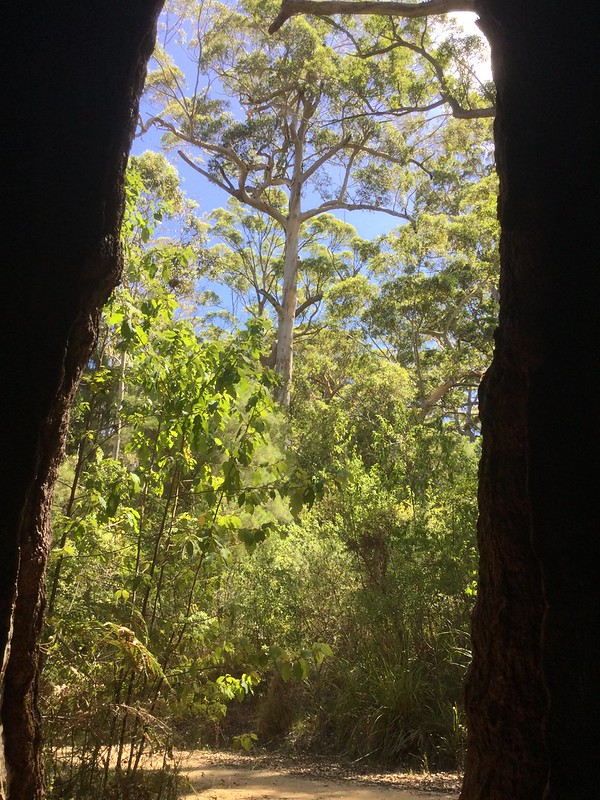

I went inside this tree but couldn’t look out of the “window”, it was too far up for me! So Brett photographed through it from the outside. The ground outside the tree is usually significantly higher than inside because the fire carves right down into the buttresses.

This was the view out. You can’t see it properly, but in the first one Brett pretended he’d been speared through the head with his walking stick. So I hereby dub this photograph “The Spearhead From Space“ (after an old Dr Who episode – my husband is a big fan).

This would be quite a nice place to overnight in if you brought a camping mattress and some mosquito veils. The base would easily accommodate a Queen-sized bed, not that you’d bring one of those. It also has great views.

This was the “door”…

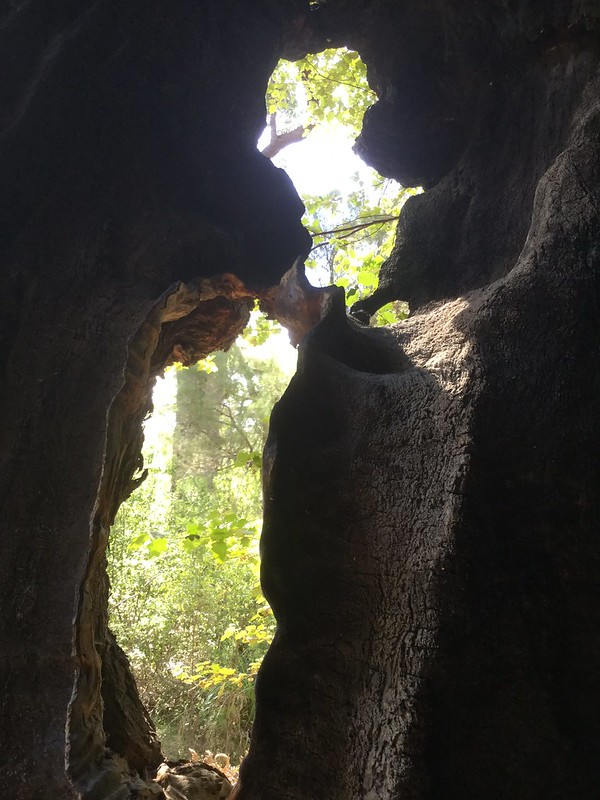

This was the roof, considerably above me.

And this is another window.

We continued on our merry way. The temperature in the forest was most pleasant, even though we had been cooking already in the sunlight on the way there. The moment you step into this tall forest, you are mostly walking in shade or dappled sunlight; only occasionally there is a burst of full sun. This is how life makes conditions for nurturing more life; creates a wonderland of species and habitat and microclimates and even influences the weather.

And we Westerners chainsawed, logged and bulldozed most of these forests into oblivion, and much of what is left into a shadow of its former glory. This is one of the little patches in which old-growth trees can still be found. Most of South-Western Australia’s forests and woodlands were converted to farmland, where pastures and monoculture crops swelter under the sun in summer and exposed soils dry out and die. Because we think what we do is so superior to what the Indigenous people who lived here for 60,000 years did. And we won’t last 60,000 years, we’ve already destroyed much of Australia in under 250 – we’re a short-term thrill with chronic delusions, mostly about how clever and superior we are, and how our technology will save us.

This next photo, Brett was very adamant should be called ” The Moss-Tache”…

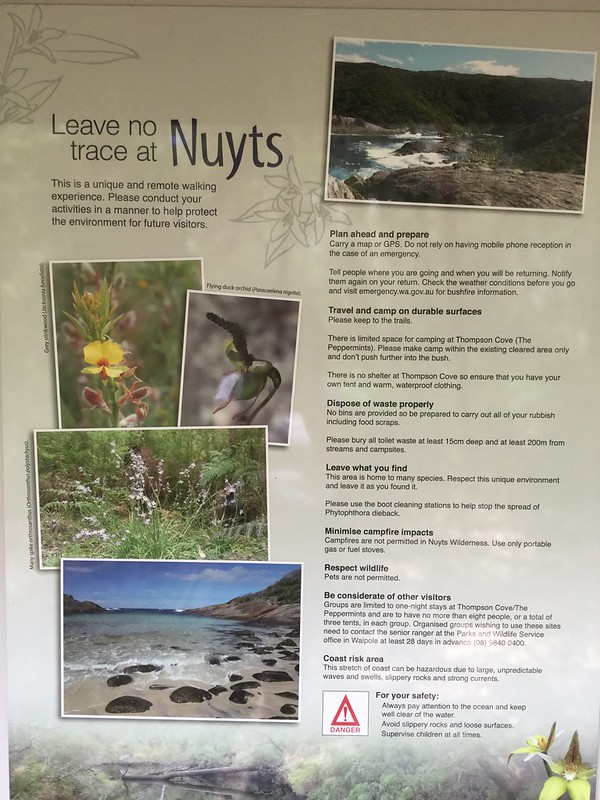

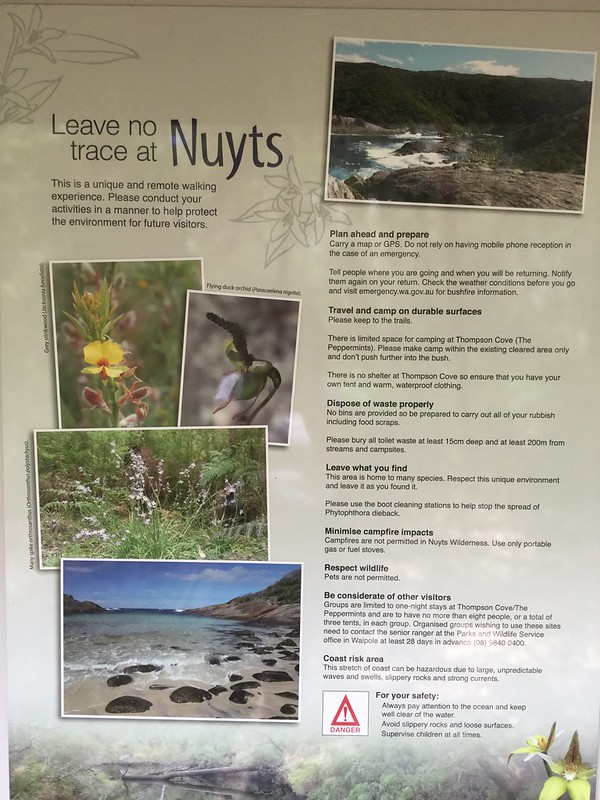

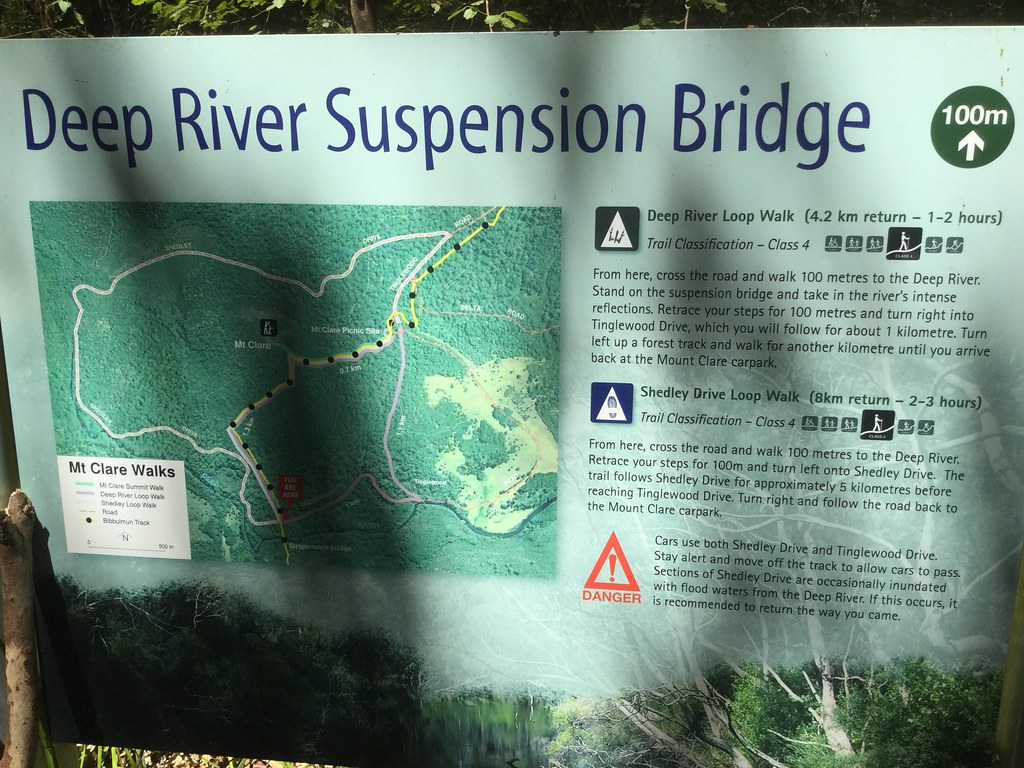

And then we were crossing Tingledale Drive, and arrived in the Nuyts Wilderness trailhead area, where there were lots of information signs.

We continued up Mt Clare – at this point the Bibbulmun Track and the start of the Nuyts Wilderness Track overlap, as you can see on the context map at the start of this photoessay. The climb up was on a gentle slope.

There were more information signs…

If you look closely behind the third Tingle in the background in the next photo you can just see the roof of the Mt Clare camping hut. You may have to look lower down than you are expecting as these trees are enormous…

Usually we stop and rest at these huts all along the Bibbulmun trail – they appear at approximately day walk intervals. However – and this was a first for us – the Mt Clare hut had been freshly repainted and reeked of industrial solvents, so we tried the open-air outdoors table instead. It too was most malodorous, as perplexing a phenomenon in such a near-pristine ecosystem as when you go mountain climbing with a chain smoker. So we checked our map and decided to have lunch at the gazetted suspension bridge across the Deep River, which sounded very interesting. We haven’t been across a suspension bridge on a hike since our half year in Launceston in 2009, where we were frequent hikers on the Cataract Gorge trails.

On the way there were some major tree hugging opportunities. Here’s a Tingle with a solid base.

An old-growth Tingle is not easy to hug. It’s a bit more like leaning in affectionately, but there’s no way the arms go anywhere near around even a fifth of the 12m circumference. Nevertheless, I think the intention is perceived in some way. These are ancient beings hundreds of years old. No wonder Tolkien wrote about Ents.

I don’t know how anybody can think cutting one of these down is fine and dandy, but in this world, every day, we are losing such trees to insane humans working in an insane economic system. I don’t know how anyone can think they make it right by “replanting” another tree. It would take hundreds of years to get to the same life stage, if it even lived that long – and natural forests plant themselves, thank you very much, and unlike plantations, are a treasure trove of genetic diversity and relationships. Humans only had to start planting trees after their own activities obliterated most of the trees on this Earth. We owe much more than we can ever repay, and it’s farcical to talk about carbon credits and biodiversity offsets. It’s a veneer of greenwash to conceal a core of ongoing and ever accelerating destruction, while people abuse words like “sustainable” and “love” and make “Centres of Excellence” for biological research which is never allowed to say no to profit and “progress”.

Here’s some upwards photos of the same tree! I got much of the trunk in the first one, but needed another to look at its crown in the canopy.

We had a kilometre to go until the Deep River; beautiful forest, and a fairly steep descent. As we approached the river valley, granite started peeping out of the ground.

The photos visually flatten out the actual steepness – in the next photo, we were upslope and across a small tributary valley from the dog who was climbing the slope on the other side!

“C’mon, keep up!” – says the dog, looking back at us. She could smell the water and was keen for the promised swim. When I know we have definite swimming opportunities ahead, I tell her there is a “splish” coming up. Dogs find words easier if you use onomatopoeia. This is also why when we’re talking to her, a car (or car trip) is a “brroom-brroom!” and the mention of this word at home gets excited leaps from her and immediate attempts to herd us out of the front door. I should film it sometime.

Descending towards the Deep River, there were some majestic Karri trees. The binomial name for this one is Eucalyptus diversicolor, and you’ll understand why looking at its bark.

I actually love the fact that on the remote and serious trails, things aren’t constantly manicured and tidied up for the convenience of typical urban walkers. I like having to climb obstacles in places like this and to use my wits and my body to work out puzzles, instead of having a kind of pedestrian freeway presented to me, as is the case for the touristy spots like Bluff Knoll and the Granite Skywalk. I enjoy having to look closely at where I am going, and figuring things out. Not having such opportunities is just another way of dumbing down our world, our inner lives, and our physicality. I come properly alive in wild places. The animal I am recognises what gave birth to me, to us, long ago.

And then we were at the suspension bridge.

We stopped in the middle of this wobbly, free-swinging bridge to drink in the views of the Deep River. I took two photos, to the west and to the east, which you are about to see. But just before I took them, I asked Brett to please stop jumping up and down, because I was taking a picture. And he said, “I’m not jumping up and down!”

“Hahaha…sorry!” Long time no suspension bridge. (But it’s exactly the sort of thing my husband has been known to do…not to deliberately interfere with photography, but just for the joy of it…♥)

And once arrived at the other side, our delighted dog cooled herself down in the Deep River.♥ We’d been giving her intermittent drinks from a bottle we take especially for her – in summer, there’s not much water in this landscape. Jess is nearly 11 now and needs extra TLC, plus a sofa recovery day after a long hike, but so far she is still coping well with extended walking and would be outraged to be left behind when we do something so fun. In her prime she used to run rings around my endurance horse, or our mountain bikes, and cover at least twice the distance we did; plus she swam like a hydrofoil as a young dog. I actually think it’s kinder to an animal to put it down when it gets to the point it can’t do the things it enjoys the most anymore, and not let it linger. We’re not at that point and right now she’s on excellent arthritis treatment that re-lubricates the joints. She also these days really enjoys her sofa recovery days, combined with good grub, which allow her body to rest and repair. In a way, we’re a bit like that ourselves these days.

Fabulous dog.♥

We lunched on the steps of the bridge, in the shade, with a breeze blowing on us and the water flowing by. Brett had made us our favourite hiking salad: Just cut carrots and cheddar cheese into cubes, mix in a roughly 3:1 ratio, dress with lemon juice and cayenne pepper. Even the dog likes it. We also had salt and vinegar peanuts, half a home-grown Cox’s Orange Pippin apple each, and water from the drink bottles, mine with a splash of lemon.

Morning tea en route to Walpole had been ice cream made by the Meadery – double coffee for him; hazelnut on top, chocolate on the bottom for me. Normally we do that after a hike, but today we put it in the tank first. Waiting at home to balance us up in the evening was a big dish of moussaka, with home-grown zucchini, potatoes, tomatoes, herbs; kangaroo mince from Woolies (we’re currently out of home-grown beef mince), cheese sauce on the top potato layer, tons of grated pepper.

Kangaroo is equivalent to venison; the top predators were largely removed on the respective continents and neither the common deer species or the Western Grey Kangaroo are endangered, but the landscape has to be protected from overgrazing (and not just by kangaroos) or we’re going to accelerate bird and small mammal extinctions, not to mention flora, insects etc. We’re happy to co-graze wild kangaroos and emus with the cattle and equines on the pasture/permie previously cleared fraction of our place and don’t deter them; we welcome their presence and, excepting for our vegetable garden, deliberately made the fence passable to them but not to the livestock. (Top and bottom polybraids in the internal fences are hot but the middle is not, so they can slip through without getting zapped. Also, for boundary fences, have you heard of kangaroo gates?)

Occasionally local Noongar people will take a roo for their traditional food from the healthy local populations, including from Red Moon Sanctuary; and we eat the odd one that gets put down due to injuries like broken bones. A local octogenarian bushie friend who died last year brought us the occasional fresh roadkill he found by the highway; Trowunna Wildlife Sanctuary in Tasmania does the same to feed their charges. We don’t have Tasmanian Devils, but we do have a dog and stomachs of our own and these carcasses need taking off the roads. It’s not for everyone, but we’re fine with it if it’s fresh (and Jess prefers it when it’s not, and will track down her own). If you grew up in the city you may be appalled, but we didn’t and we do live close to the cycle of life and its realities. Also I’m a very good cook, and we’re both foodies – so don’t imagine that there are taste or food safety compromises.

Alas, the food that nurtures, repairs and powers us, and the acceptance that we should give ourselves in turn to the nurture, repair and powering of other beings when our lives end, instead of locking ourselves away like misers when we’re dead. Hat firmly off to Indigenous Australian traditional burials, and the sky burials in the Himalayas, and any other culture who recognises that we are part of the circle and need to act and live like it.

And then we were homeward bound again, for variety taking the loop route via Tingledale Drive back to the Bibbulmun (see map at start).

There were more Tingles with hollowed-out bases whose cubbies I tried out.

There was an agricultural clearing in this valley with something that looked like an outdoor education camp.

It was really hot on the road – removing a forest will change the microclimate. Local cattle were looking to rest under shade trees. Many of the big-business paddocks near where we live haven’t got a single tree in them and it should be illegal to keep animals in shadeless pastures – but the big corporations have got into the beef game and are making their own rules, which are all about maximising profit and pushing family farmers out of business. It’s expensive and time-consuming to plant shelter belts as we did, and you won’t break even financially on them through increased livestock productivity – we do it because it’s the right thing for umpteen reasons including livestock welfare, biodiversity conservation, soil conservation, the water cycle, water quality in rivers/estuaries etc, but having worked as an environmental scientist and seen how this goes, I don’t expect environmental and animal welfare issues to be given more than lip service and occasional window dressing projects by our powers that be. Money and greed drive basically everything in our culture, and big business is good at obfuscating and at finding scapegoats for a largely ignorant public to swallow.

Glory be, in this non-corporate little valley someone was deliberately planting Peppermint trees by the roadside for shade. You can see them in this view back towards the south-east. We have planted clumps of them too; a decade later they become enormous and make welcome shelter areas for birds, insects and domestic pasture inhabitants.

Mature shade trees are very popular things…

We rather felt like lying down under one of these trees ourselves, at this point. There is a world of difference between spending a summer midday in a tall forest, or walking on a road through a clearing. And to be honest, our feet were beginning to hurt after several hours of serious hiking that hadn’t strictly been on the agenda when we woke up – and it’s not as much fun to hike on vehicle tracks than twisty-turny walk trails.

Occasionally, remnant roadside trees provided a bit of shade. We were very happy to get to the Bibbulmun track intersection and back into the proper forest, where Brett was keen to pose for a photo.

He is such a drama queen. I’ve got a very similar photo of him at the tail end of our 8-hour loop climbing Cradle Mountain and returning via the Twisted Lakes, from years and years ago…

We were very happy to be out of the sun again.

Fallen forest trees make such great habitat opportunities…and it’s so annoying when ignorant people take their chainsaws and 4WDs into forests to “tidy up” and get a trailer load of firewood, thinking they’ve done some kind of community service when they’ve actually made wildlife homeless. This is where we are at – with a largely ecologically ignorant population of zoo humans thinking like this, about this and hundreds of other situations involving other species. Where do you even begin, and what hope if it conflicts with their existing world views, which are so precious to many and almost written in stone? That’s adult…it was a lot better working with adolescents, who were more open-minded and willing to look critically at the everyday and “normal” than their alleged elders and betters, than it is to try to have discussions like this with adults who have shut shop.

Thankfully I also know adults who haven’t shut shop, and continue to learn and to modify their working hypotheses; and they love the natural world. Those are my tribe, and it’s a small tribe, possibly endangered, but much loved and appreciated!♥

And that’s all the photos! We got back to John Rate Lookout, where we immediately took off our hiking boots to air our hot and tired feet, and drove home barefoot, listening to mostly acoustic music and chatting about this and that while fantasising about large cups of tea and bed rest. What an excellent day – and such an unexpected long adventure on a completely new-to-us trail! I couldn’t sleep for ages that night due to all the metaphorical champagne bubbles fizzing around inside of me. A day like this makes up for so many days of toil and staying home, for living on a smallholding in the middle of nowhere and no longer travelling much in the world. A day of wonder where you see and embrace wild nature, and she sees and embraces you.

♥ ♥ ♥

All the photos in this piece were taken by Sue Coulstock and Brett Coulstock.

Featured image: A numbat by The Last Stand via Flickr(CC BY-NC 2.0)

by DGR News Service | Feb 20, 2023 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Obstruction & Occupation, Protests & Symbolic Acts, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: In order to fill the void of fossil fuel supplies caused by the Russia-Ukraine War, countries are opening their land for coal extraction. We recently covered the resistance in Lützerath, Germany. A similar story seems to be unraveling in Australia. The following piece, originally published in Public Eye, follows the tragic Aboriginal land grabbing by corporations spanning two continents. Despite local resistance and vigil for over 400 days, the mines have not yet been stopped.

By Adrià Budry Carbó / Public Eye

With the war in Ukraine forcing Europe to seek alternatives to Russian fossil fuels, Australia is opening dozens of coal mines – and sacrificing its natural and cultural heritage in the process. Local authorities are invoking the consequences of the European war to get projects approved, despite the fact that behind the scenes it is the interests of Glencore and Adani – both based in Switzerland – that are ultimately at play.

In remote areas of Queensland, Aboriginal people and environmentalists are organising resistance to the shovel-and-dynamite lobby, but are coming under increasing pressure from mining groups.

Ochre earth gets everywhere, as gritty as those who walk on it, omnipresent in the semi-desert landscape. A pale-yellow column of smoke – up to 50 metres high – stands out against the horizon. With no high ground to cause an echo, the blast from the deep scar of the Carmichael mine rings out with a sharp bang. The mine is located in the geological basin of Galilee, in the heart of Queensland in north-eastern Australia.

Coedie MacAvoy has witnessed this scene often. Born and raised in the region, the son of an Elder of the Wangan and Jagalingou people (a guardian of wisdom), the 30-year-old introduces himself with pride. He relates the number of days he has spent occupying the small plot of land situated just in front of the Adani Group’s concession, which the company wants to transform into one of the largest coal mines in the world. On this October afternoon, the count is at 406 days – the same number of days as the camp of the Waddananggu (meaning “discussion” in the Wirdi language) has existed.

This vigil was not enough to prevent the start of production last December, but it’s a big thorn in the side of the ambitious multinational. The company is controlled by the Indian billionaire Gautam Adani, who became the third richest man in the world (net worth USD 142.4 billion) thanks to booming coal prices (see below). In April 2020, he set up a commercial branch in Geneva with the aim of offloading its coal, and registered with a local fiduciary. According to Public Eye’s sources, Adani benefitted from the support of Credit Suisse, which enabled it to raise USD 27 million in bonds in 2020. After Coal India, Adani has the largest number of planned new coal mines (60) according to the specialist platform Global Coal Mine Tracker. Glencore occupies sixth position in this ranking with 37 planned.

Gautam Adani controls one third of India’s coal imports. As reported by The New Yorker in November 2022, the billionaire is well known in his own country too – for bulldozing villages and forests to dig gigantic coal mines.

In Waddananggu, the ceremonial flames of those known here as “traditional owners” have been burning since 26 August 2021. They are accompanied by various people who come and go; young climate and pro-Aboriginal activists, sometimes together with their children – around 15 people in total. Those who emerge from the tents and barricades to observe the thick column of smoke that is dispersing into the distance are told: “Don’t breathe that shit in!”.

The Austral protestors, the war and the billionaire

With sunburned shoulders, a feather in her felt hat covering her blond hair, Sunny films the cloud of dust moving away to the north-west, towards the surrounding crops and scattered cattle. Sunny denounces the destruction of Aboriginal artefacts that are as old as the hills, and is documenting all the blasts from this mine which – after around 15 years of legal wrangling – is expanding at top speed.

After two years of pandemic, coal mines are producing at full throttle to capitalise on historically high prices. Following the invasion of Ukraine on 24th February last year, Australian coal (the most suitable substitute for Russian coal in terms of quality) is selling at three times the average price of the past decade. Countries highly dependent on Russian fossil fuels, like Poland, have been begging Australia to increase its exports of thermal coal. In Queensland, the authorities even took advantage of the situation to support particularly unpopular projects, such as Adani’s.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, 3.3 million tonnes of Australian coal have been exported to Europe, according to data provided to Public Eye by the specialist agency Argus Media. Close to half of these exports (1.4 million tonnes) was dispatched on 11 bulk carriers from the Abbot Point terminal, which opens onto the Coral Sea in the north-east of the country, and is also controlled by Adani.

Sunny is indignant: “They shouldn’t detonate when the wind is like this”, she says. “They shouldn’t do it at all – but even less so today!”

For Adani, the objective is to reach 10 million tonnes’ production until the end of 2022. If the group seems to be in a tearing hurry, it’s because its project was initially aiming to produce 60 million tonnes per year, transported 300 kilometres via a dual railway line to Abbot Point. This port is only a few dozen kilometres from the Great Barrier Reef: designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981, it is considered to be “endangered”, according to a report by UN experts published at the end of November 2022. From here, coal is loaded onto bulk carriers to be burned – primarily in Indian, Chinese and Korean power-plants – nearly 10,000 kilometres from there.

For Grant Howard, a former miner from the region of Mackay who spent 30 years working in the industry, the mine is an environmental and logistical aberration: “Carmichael only makes commercial sense because Adani owns all the infrastructure and makes the Indian population pay too much for energy”.

Grant became an environmentalist and withdrew to the “bush” to be closer to nature. He denounces this “anachronistic” project that is threatening to act as a Trojan Horse for other mega mining projects in the Galilee Basin, which had not been exploited until Gautam Adani’s teams arrived.

“People who continue to extract thermal coal don’t have a moral compass”, he laments.

Australia has the third-largest coal reserves in the world, enough to continue production for four centuries.

When contacted, Credit Suisse claims to be fulfilling its responsibilities in relation to climate change. “We recognise that financial flows should also be aligned with the objectives set by the Paris Agreement”, its media service states, providing assurances that, in 2021, the bank reduced its financial exposure to coal by 39 percent.

On the other hand, the spokesperson did not specify whether a client like Adani, which makes most of its revenues from coal and is planning to open new thermal coal mines, would be excluded from financing in the future. “The position of Credit Suisse in terms of sustainability is based on supporting our clients through the transition towards low-carbon business models that are resilient to climate change”, they explain.

The country’s bloody history

For Coedie MacAvoy, this is very much a personal affair. In support of the fight of his “old man” – his father Adrian Burragubba went bankrupt in legal proceedings against the multinational – he occupied the Carmichael site on his own in 2019 in order to “reclaim pieces of property” on his ancestral lands. In doing so he created a blockade against Adani’s construction teams. He survived two weeks of siege before the private security services completely cut off his supply lines.

The same man has led the rebellion since August 2021, but he is no longer alone. “I am contesting the basic right of the government to undertake a compulsory acquisition of a mining lease”, declares Coedie. With piercing green eyes, a rapper’s flow, and his totem tattooed on his torso, the rebel-looking, young man – who has an air of fight the power – is happy to continue the lineage of activists occupying the trees. “I’m not a greenie from inner Melbourne”, asserts the Aborigine.