by DGR News Service | Oct 18, 2021 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Listening to the Land, The Problem: Civilization

This is an excerpt from the book Bright Green Lies, P. 1-7

By LIERRE KEITH

“Once our authoritarian technics consolidates its powers, with the aid of its new forms of mass control, its panoply of tranquilizers and sedatives and aphrodisiacs, could democracy in any form survive? That question is absurd: Life itself will not survive, except what is funneled through the mechanical collective.”1

LEWIS MUMFORD

There is so little time and even less hope here, in the midst of ruin, at the end of the world. Every biome is in shreds. The green flesh of forests has been stripped to grim sand. The word water has been drained of meaning; the Athabascan River is essentially a planned toxic spill now, oozing from the open wound of the Alberta tar sands. When birds fly over it, they drop dead from the poison. No one believes us when we say that, but it’s true. The Appalachian Mountains are being blown to bits, their dense life of deciduous forests, including their human communities, reduced to a disposal problem called “overburden,” a word that should be considered hate speech: Living creatures—mountain laurels, wood thrush fledglings, somebody’s grandchildren—are not objects to be tossed into gullies. If there is no poetry after Auschwitz, there is no grammar after mountaintop removal. As above, so below. Coral reefs are crumbling under the acid assault of carbon. And the world’s grasslands have been sliced to ribbons, literally, with steel blades fed by fossil fuel. The hunger of those blades would be endless but for the fact that the planet is a bounded sphere: There are no continents left to eat. Every year the average American farm uses the energy equivalent of three to four tons of TNT per acre. And oil burns so easily, once every possibility for self-sustaining cultures has been destroyed. Even the memory of nature is gone, metaphrastic now, something between prehistory and a fairy tale. All that’s left is carbon, accruing into a nightmare from which dawn will not save us. Climate change slipped into climate chaos, which has become a whispered climate holocaust. At least the humans whisper. And the animals? During the 2011 Texas drought, deer abandoned their fawns for lack of milk. That is not a grief that whispers. For living beings like Labrador ducks, Javan rhinos, and Xerces blue butterflies, there is the long silence of extinction.

We have a lot of numbers. They keep us sane, providing a kind of gallows’ comfort against the intransigent sadism of power: We know the world is being murdered, despite the mass denial. The numbers are real. The numbers don’t lie. The species shrink, their extinctions swell, and all their names are other words for kin: bison, wolves, black-footed ferrets. Before me (Lierre) is the text of a talk I’ve given. The original version contains this sentence: “Another 120 species went extinct today.” The 120 is crossed clean through, with 150 written above it. But the 150 is also struck out, with 180 written above. The 180 in its turn has given way to 200. I stare at this progression with a sick sort of awe. How does my small, neat handwriting hold this horror? The numbers keep stacking up, I’m out of space in the margin, and life is running out of time.

Twelve thousand years ago, the war against the earth began. In nine places,2 people started to destroy the world by taking up agriculture. Understand what agriculture is: In blunt terms, you take a piece of land, clear every living thing off it—ultimately, down to the bacteria—and then plant it for human use. Make no mistake: Agriculture is biotic cleansing. That’s not agriculture on a bad day, or agriculture done poorly. That’s what agriculture actually is: the extirpation of living communities for a monocrop for and of humans. There were perhaps five million humans living on earth on the day this started—from this day to the ending of the world, indeed—and there are now well over seven billion. The end is written into the beginning. As earth and space sciences scholar David R. Montgomery points out, agricultural societies “last 800 to 2,000 years … until the soil gives out.”3 Fossil fuel has been a vast accelerant to both the extirpation and the monocrop—the human population has quadrupled under the swell of surplus created by the Green Revolution—but it can only be temporary. Finite quantities have a nasty habit of running out. The name for this diminishment is drawdown, and agriculture is in essence a slow bleed-out of soil, species, biomes, and ultimately the process of life itself. Vertebrate evolution has come to a halt for lack of habitat, with habitat taken by force and kept by force: Iowa alone uses the energy equivalent of 4,000 Nagasaki bombs every year. Agriculture is the original scorched-earth policy, which is why both author and permaculturist Toby Hemenway and environmental writer Richard Manning have written the same sentence: “Sustainable agriculture is an oxymoron.” To quote Manning at length: “No biologist, or anyone else for that matter, could design a system of regulations that would make agriculture sustainable. Sustainable agriculture is an oxymoron. It mostly relies on an unnatural system of annual grasses grown in a mono- culture, a system that nature does not sustain or even recognize as a natural system. We sustain it with plows, petrochemicals, fences, and subsidies, because there is no other way to sustain it.”4

Agriculture is what creates the human pattern called civilization. Civilization is not the same as culture—all humans create culture, which can be defined as the customs, beliefs, arts, cuisine, social organization, and ways of knowing and relating to each other, the land, and the divine within a specific group of people. Civilization is a specific way of life: people living in cities, with cities defined as people living in numbers large enough to require the importation of resources. What that means is that they need more than the land can give. Food, water, and energy have to come from somewhere else. From that point forward, it doesn’t matter what lovely, peaceful values people hold in their hearts. The society is dependent on imperialism and genocide because no one willingly gives up their land, their water, their trees. But since the city has used up its own, it has to go out and get those from somewhere else. That’s the last 10,000 years in a few sentences. Over and over and over, the pattern is the same. There’s a bloated power center surrounded by conquered colonies, from which the center extracts what it wants, until eventually it collapses. The conjoined horrors of militarism and slavery begin with agriculture.

Agricultural societies end up militarized—and they always do—for three reasons. First, agriculture creates a surplus, and if it can be stored, it can be stolen, so, the surplus needs to be protected. The people who do that are called soldiers. Second, the drawdown inherent in this activity means that agriculturalists will always need more land, more soil, and more resources. They need an entire class of people whose job is war, whose job is taking land and resources by force—agriculture makes that possible as well as inevitable. Third, agriculture is backbreaking labor. For anyone to have leisure, they need slaves. By the year 1800, when the fossil fuel age began, three-quarters of the people on this planet were living in conditions of slavery, indenture, or serfdom.5 Force is the only way to get and keep that many people enslaved. We’ve largely forgotten this is because we’ve been using machines—which in turn use fossil fuel—to do that work for us instead of slaves. The symbiosis of technology and culture is what historian, sociologist, and philosopher of technology Lewis Mumford (1895-1990) called a technic. A social milieu creates specific technologies which in turn shape the culture. Mumford writes, “[A] new configuration of technical invention, scientific observation, and centralized political control … gave rise to the peculiar mode of life we may now identify, without eulogy, as civilization… The new authoritarian technology was not limited by village custom or human sentiment: its herculean feats of mechanical organization rested on ruthless physical coercion, forced labor and slavery, which brought into existence machines that were capable of exerting thousands of horsepower centuries before horses were harnessed or wheels invented. This centralized technics … created complex human machines composed of specialized, standardized, replaceable, interdependent parts—the work army, the military army, the bureaucracy. These work armies and military armies raised the ceiling of human achievement: the first in mass construction, the second in mass destruction, both on a scale hitherto inconceivable.”6

Technology is anything but neutral or passive in its effects: Ploughshares require armies of slaves to operate them and soldiers to protect them. The technic that is civilization has required weapons of conquest from the beginning. “Farming spread by genocide,” Richard Manning writes.7 The destruction of Cro-Magnon Europe—the culture that bequeathed us Lascaux, a collection of cave paintings in southwestern France—took farmer-soldiers from the Near East perhaps 300 years to accomplish. The only thing exchanged between the two cultures was violence. “All these artifacts are weapons,” writes archaeologist T. Douglas Price, with his colleagues, “and there is no reason to believe that they were exchanged in a nonviolent manner.”8

Weapons are tools that civilizations will make because civilization itself is a war. Its most basic material activity is a war against the living world, and as life is destroyed, the war must spread. The spread is not just geographic, though that is both inevitable and catastrophic, turning biotic communities into gutted colonies and sovereign people into slaves. Civilization penetrates the culture as well, because the weapons are not just a technology: no tool ever is. Technologies contain the transmutational force of a technic, creating a seamless suite of social institutions and corresponding ideologies. Those ideologies will either be authoritarian or democratic, hierarchical or egalitarian. Technics are never neutral. Or, as ecopsychology pioneer Chellis Glendinning writes with spare eloquence, “All technologies are political.”9

Sources:

- Lewis Mumford, “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics,” Technology and Culture 5, no. 1 (Winter, 1964).

- There exists some debate as to how many places developed agriculture and civilizations. The best current guess seems to be nine: the Fertile Crescent; the Indian sub- continent; the Yangtze and Yellow River basins; the New Guinea Highlands; Central Mexico; Northern South America; sub-Saharan Africa; and eastern North America.

- David R. Montgomery, Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 236.

- Richard Manning, Rewilding the West: Restoration in a Prairie Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 185.

- Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves (Boston: Mariner Books, 2006), 2.

- Mumford op cit (Winter, 1964), 3.

- Richard Manning, Against the Grain: How Agriculture Has Hijacked Civilization (New York: North Point Press, 2004), 45.

- T. Douglas Price, Anne Birgitte Gebauer, and Lawrence H. Keeley, “The Spread of Farming into Europe North of the Alps,” in Douglas T. Price and Anne Brigitte Gebauer, Last Hunters, First Farmers (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1995).

- Chellis Glendinning, “Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto,” Utne Reader, March- April 1990, 50.

by DGR News Service | Jun 7, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: The Biden administration’s budget to address the extinction crisis for the year 2021 is $22 million ($22,000,000). That is $60,273 per day, $2,511 per hour, and $41 per second.

The Biden administration’s military budged for the year 2021 is $705.39 billion ($705,390,000,000). That is $1,93 billion per day, $80,527 million per hour, and $1,34 million per second. The US military is also the single largest polluter in the world, burning about 269,230 barrels of oil per day.

The numbers alone show the preferences of this “culture” very clearly. (In my view, the term “culture” seems inappropriate to describe a societal structure that follows the logic of a cancer cell.)

Featured image: “We Live Here Too” by Nell Parker.

This is a press release from the Center for Biological Diversity, May 28.

WASHINGTON— With today’s (May 28) release of President Biden’s first full budget, the administration signaled that stemming the wildlife extinction crisis and safeguarding the nation’s endangered species will not be a top priority, despite the warnings of scientists that one million species are at risk of going extinct around the world without intervention.

The Biden administration is proposing just $22 million — a mere $1.5 million above last year’s levels — to protect the more than 500 imperiled animals and plants still waiting for protection under the Endangered Species Act. It is at the same level as what was provided for in 2010.

The budget proposal increases funding for endangered species recovery by $18 million. While this represents a modest increase from last year’s budget, the Endangered Species Act has been severely underfunded for decades, resulting in species waiting years, or even decades, for protection and already-protected species receiving few dollars for their recovery.

Based on the Fish and Wildlife Service’s own recovery plans, at least $2 billion per year is needed to recover the more than 1,700 endangered species across the country. The proposed budget fails to even come close to closing the gap in needed funding.

“It’s distressing that President Biden’s budget still ignores the extinction crisis,” said Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “What’s especially tragic is that restoring abundant wildlife populations would also reap huge benefits in helping to stop the climate crisis, reduce toxic pollution and protect wild places. This was a missed opportunity.”

During the presidential campaign, President Biden touted his early support for the Endangered Species Act when the law was passed in 1973. In January President Biden launched a review of the Trump administration’s rollbacks of the regulations implementing the Endangered Species Act and decisions to weaken protections for the monarch butterfly, spotted owl and gray wolf.

To date, however, the Biden administration has not moved to alter or reverse any Trump-era policies or decisions related to endangered species. With today’s budget, President Biden is adopting the measly funding levels of the Trump administration.

Over the past year, more than 170 conservation groups have asked for additional funding for endangered species. This request echoes similar pleas from 121 members of the House of Representatives and 21 senators.

“Every year, more of our most distinctive animals and plants will vanish right before our eyes. Perhaps for the sake of his grandchildren, President Biden will reconsider this disastrous budget proposal,” said Hartl.

Around 650 U.S. plants and animals have already been lost to extinction. Some of the plants and animals that have been deemed extinct in the United States since 2000 include: Franklin’s bumblebee from California and Oregon; the rockland grass skipper and Zestos skipper butterflies from Florida; the Tacoma pocket gopher; the Alabama sturgeon; the chucky madtom, a small catfish from Tennessee; a wildflower named Appalachian Barbara’s buttons; and the Po’ouli, a songbird from Maui. Scientists estimate that one-third of America’s species are vulnerable to extinction and 12,000 species nationwide are in need of conservation action.

| Contact: |

Brett Hartl, (202) 817-8121, bhartl@biologicaldiversity.org |

The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, nonprofit conservation organization with more than 1.7 million members and online activists dedicated to the protection of endangered species and wild places.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 24, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

by Kate Randall / World Socialist Web Site

Drug overdose deaths in the US topped 72,000 in 2017, according to new provisional estimates released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This staggering figure translates into about 200 drug overdose deaths every day, or about one every eight minutes.

The new CDC estimates are 6,000 deaths more than 2016 estimates, a rise of 9.5 percent. This has been primarily driven by a continued rise of deaths involving synthetic opioids, a category of drugs that includes fentanyl. Nearly 30,000 deaths involved these drugs in 2017, an increase of more than 9,000 (nearly 50 percent) over the previous year, according to preliminary data.

This catastrophic toll of opioid deaths casts a grim light on the state of America in the 21st century. At its root lies a society characterized by vast social inequality, corporate greed and government indifference. While the opioid crisis spares no segment of society, the most profoundly affected are workers and the poor, along with the communities where they live.

Deaths involving the stimulant cocaine also rose significantly, placing them on par with heroin and the category of natural opiates including painkillers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. The CDC estimates suggest that deaths involving the latter two drugs appear to have flattened out.

The highest mortality rates in 2017 were distributed similarly to previous years, with parts of Appalachia and New England showing the largest figures. West Virginia again saw the highest death rates, with 58.7 overdose deaths per 100,000 residents, followed by the District of Columbia (50.4), Pennsylvania (44.2), Ohio (44.0) and Maryland (37.9). Nebraska had the lowest rate, 8.2 deaths per 100,000, one-seventh the West Virginia rate.

Two states with relatively high rates of overdose deaths, Vermont and Massachusetts, saw some decreases. The CDC credits this decrease to a leveling off of synthetic opioid availability and a modest increase in these states of funding for programs to fight addiction and provide treatment and rehabilitation.

Driving the increase in overdose deaths is fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is roughly 50 times more potent that heroin. It is marketed under more than a dozen brand names in the US. Nebraska became the first state to use fentanyl in a state-sanctioned killing, using it Tuesday to execute Carey Dean Moore.

Fentanyl is also made illegally relatively easily and mixed with black market supplies of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamines and anti-anxiety medicines known as benzodiazepines. Individuals who have become addicted to prescription opioids often turn to illegally manufactured fentanyl, or related drugs that can be far more potent and dangerous, when prescription opioids are not available. Users cannot know the potency of such drugs or drug mixtures and are more likely to overdose.

The CDC reports that the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS), which identifies drugs from submissions tested for analysis, estimated that submissions testing positive have included two extremely potent drugs related to fentanyl, carfentanil and 3-methylfentanyl, which are 100 and 4 times more potent than fentanyl, respectively.

Purdue Pharma has drawn widespread criticism for its aggressive marketing and sale of the opioid OxyContin, which has a high potential for abuse, particularly for those with a history of addiction. The company also produces pain medications such as hydromorphone, oxycodone, fentanyl, codeine and hydrocodone.

Regions with high levels of unemployment and poverty have been the target of drug distributors, shipping vast quantities of opioid painkillers to these areas. For example, McKesson Corporation shipped 151 million doses of oxycodone and hydrocodone between 2007 and 2012 to West Virginia, the state with the highest rate of overdose mortality.

Workers, both employed and unemployed, have found themselves in the grip of the opioid crisis. In an interview with Vox.com, Beth Macy, author of the new book Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America, describes the high levels of addiction in Machias, Maine, an early center of the opioid crisis. People in this logging and fishing community were already on painkillers from injuries due to these jobs and then became addicted to opioids—both prescription and illegal—and continue to overdose at high rates.

A study by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health examined 4,302 opioid deaths from 2011 to 2015 among workers in all occupations in the state. It found that construction workers were six times more likely to die from opioid overdoses than the average worker, and that one in three construction-worker deaths were the result of overdoses.

There are fewer workers in farming, fishing and forestry in Massachusetts, but the report found these jobs also had an opioid mortality rate five times the average. The study found a link between higher rates of opioid abuse in occupations where back injuries are more common and paid sick leave is less so. In other words, workers become addicted to drugs—and face potential overdose—when they are forced to choose between working through pain or suffering a loss of wages.

Conservative estimates place the number of Americans with opioid abuse disorder at 2.6 million, but the real total is undoubtedly higher. To the 72,000 who succumbed to drug overdose in 2017 must be added those directly impacted by the crisis—family members, friends, coworkers, medical responders, social workers, treatment center workers, and many others.

Drug overdoses are part of a greater social crisis that is claiming the lives of increasing numbers. In December 2017, the CDC released reports revealing that life expectancy of the American working class is declining due to an increase in both drug overdoses and suicides. “Deaths of despair”—overdoses, suicides, alcohol-related deaths—are causing a dramatic increase in the mortality rate among those under the age of 44.

The decline in life expectancy, a fundamental measure of social progress, is an indication of both American capitalism’s decline and the sharp intensification of social inequality. While the richest five percent of the population owns 67 percent of the wealth, the poorest 60 percent owns just 1 percent.

Of the 72,000 Americans who died in drug overdoses in 2017, workers and the poor were the most affected. By contrast, the wealthiest Americans have access to the best medical care and technology available, and as a result live on average 20 years longer than the poorest members of US society.

The rise in drug overdoses is the product of a bipartisan assault of the social gains of the working class. Over the past 40 years, both the Democrats and Republicans have engaged in a conscious strategy to claw back the gains won by the working class in the first half of the 20th century. The response of both the Obama and Trump administrations to this crisis has amounted to a combination of indifference and disdain for the lives lost.

The Obama administration slashed the number of DEA cases brought against drug distributors by 69.5 percent between 2011 and 2014. The Trump administration last year declared the opioid epidemic a “public health emergency,” but then allocated no new funding to the states to address it. Yet hundreds of billions are budgeted to fund the myriad wars prosecuted by the US military and for the persecution of immigrants by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

A health emergency on the scale of the drug epidemic requires an emergency, socialist response. Billions of dollars must be allocated to fund rehabilitation centers, utilizing the latest scientific treatments methods. The wealth of the drug manufacturers must be expropriated and their facilities placed under the control of the working class, as part of a socialized health care system that provides free health care for all.

Originally published at WSWS. Republished with permission.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 13, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “A Taxonomy of Action” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

And here yet another temptation asserts itself. Why not wait until our cause becomes vivid and urgent enough, and our side numerous enough, to vote our opponents out of office? Why not be patient? My own answer is that while we are being patient, more mountains, forests, and streams, more people’s homes and lives, will be destroyed in the Appalachian coal fields. Are 400,000 acres of devastated land, and 1,200 miles of obliterated streams not enough? This needs to be stopped. It does not need to be “regulated.” As both federal and state governments have amply shown, you cannot regulate an abomination. You have got to stop it.

—Wendell Berry, author and farmer

We got further smashing windows than we ever got letting them smash our heads.

—Christabel Pankhurst, suffragist

What is at stake? Whippoorwills, the female so loyal to her young she won’t leave her nest unless stepped on, the male piping his mating song of pure liturgy. They are 97 percent gone from their eastern range.

What is at stake? Mycorrhizal fungi, feeding their chosen plant companions and helping to create soil, with miles of filament in a teaspoon of earth. Bluefin tuna, warm-blooded and shimmering with speed. The eldritch beauty of amanita mushrooms. The mission blue butterfly, a fairy creature if there ever was one. A hundred miles of river turned silver with fish. A thousand autumn wings urging home. A million tiny radicles anchoring into earth, each with a dream of leaves, a lace of miracles, each thread both fierce and fragile, holding the others in place.

If you love this planet, it’s time to put away the distractions that have no potential to stop this destruction: lifestyle adjustments, consumer choices, moral purity. And it’s time to put away the diversion of hope, the last, useless weapon of the desperate.

We have better weapons. If you love this planet, it’s time to put them all on the table and make some decisions.

What do we want? We want global warming to stop. We want to end the globalized exploitation of the poor. We want to stop the planet from being devoured alive. And we want the planet to recover and rejuvenate.

We want, in no uncertain terms, to bring down civilization.

As Derrick succinctly wrote in Endgame, “Bringing down civilization means depriving the rich of their ability to steal from the poor, and it means depriving the powerful of their ability to destroy the planet.” It means thoroughly destroying the political, social, physical, and technological infrastructure that not only permits the rich to steal and the powerful to destroy, but rewards them for doing so.

The strategies and tactics we choose must be part of a grander strategy. This is not the same as movement-building; taking down civilization does not require a majority or a single coherent movement. A grand strategy is necessarily diverse and decentralized, and will include many kinds of actionists. If those in power seek Full-Spectrum Dominance, then we need Full-Spectrum Resistance.1

Effective action often requires a high degree of risk or personal sacrifice, so the absence of a plausible grand strategy discourages many genuinely radical people from acting. Why should I take risks with my own safety for symbolic or useless acts? One purpose of this book is to identify plausible strategies for winning.

If we want to win, we must learn the lessons of history. Let’s take a closer look at what has made past resistance movements effective. Are there general criteria to judge effectiveness? Can we tell whether tactics or strategies from historical examples will work for us? Is there a general model—a kind of catalog or taxonomy of action—from which resistance groups can pick and choose?

The answer to each of these questions is yes.

To learn from historical groups we need four specific types of information: their goals, strategies, tactics, and organization.

Goals can tell us what a certain movement aimed to accomplish and whether it was ultimately successful on its own terms. Did they do what they said they wanted to?

Strategies and tactics are two different things. Strategies are long-term, large-scale plans to reach goals. Historian Liddell Hart called military strategy “the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy.”2 The Allied bombing of German infrastructure during WWII is an example of one successful strategy. Others include the civil rights boycotts of prosegregation businesses and suffragist strategies of petitioning and pressuring political candidates directly and indirectly through acts that included property destruction and arson.

Tactics, on the other hand, are short-term, smaller-scale actions; they are particular acts which put strategies into effect. If the strategy is systematic bombing, the tactic might be an Allied bombing flight to target a particular factory. The civil rights boycott strategy employed tactics such as pickets and protests at particular stores. The suffragists met their strategic goal by planning small-scale arson attacks on particular buildings. Successful tactics are tailored to fit particular situations, and they match the people and resources available.

Organization is the way in which a group composes itself to carry out acts of resistance. Resistance movements can vary in size from atomized individuals to large, centrally run bureaucracies, and how a group organizes itself determines what strategies and tactics it is capable of undertaking. Is the group centralized or decentralized? Does it have rank and hierarchy or is it explicitly anarchist in nature? Is the group heavily organized with codes of conduct and policies or is it an improvisational “ad hocracy?” Who is a member, and how are members recruited? And so on.

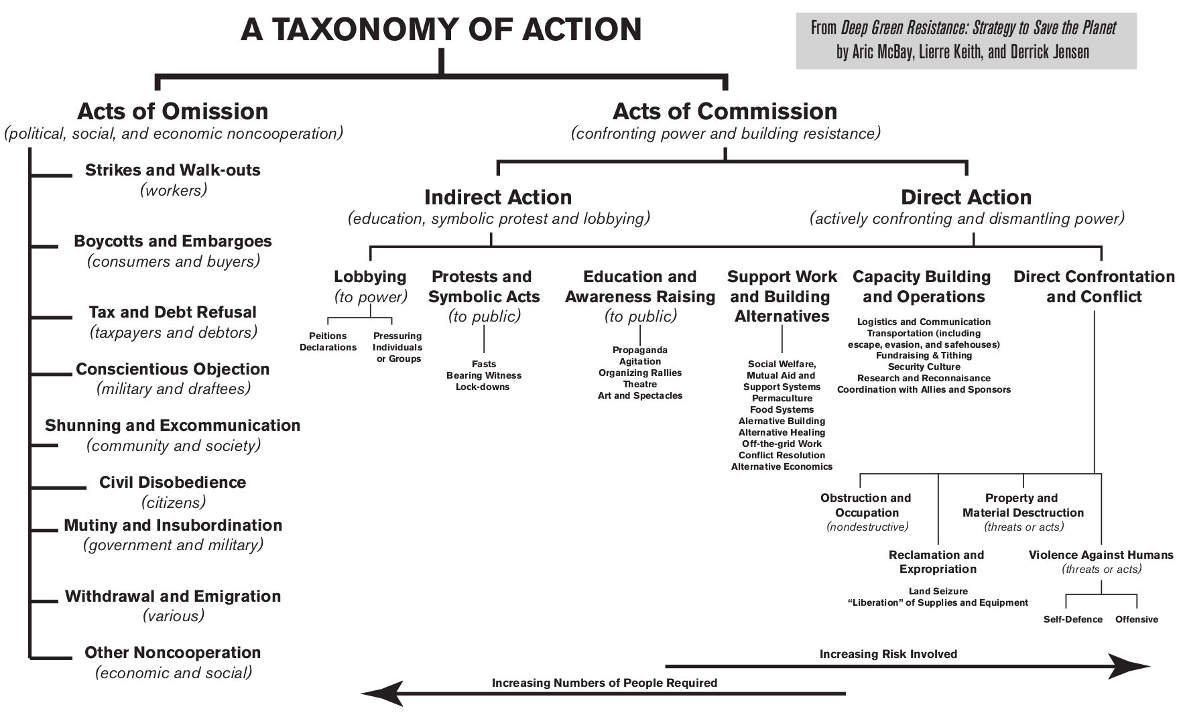

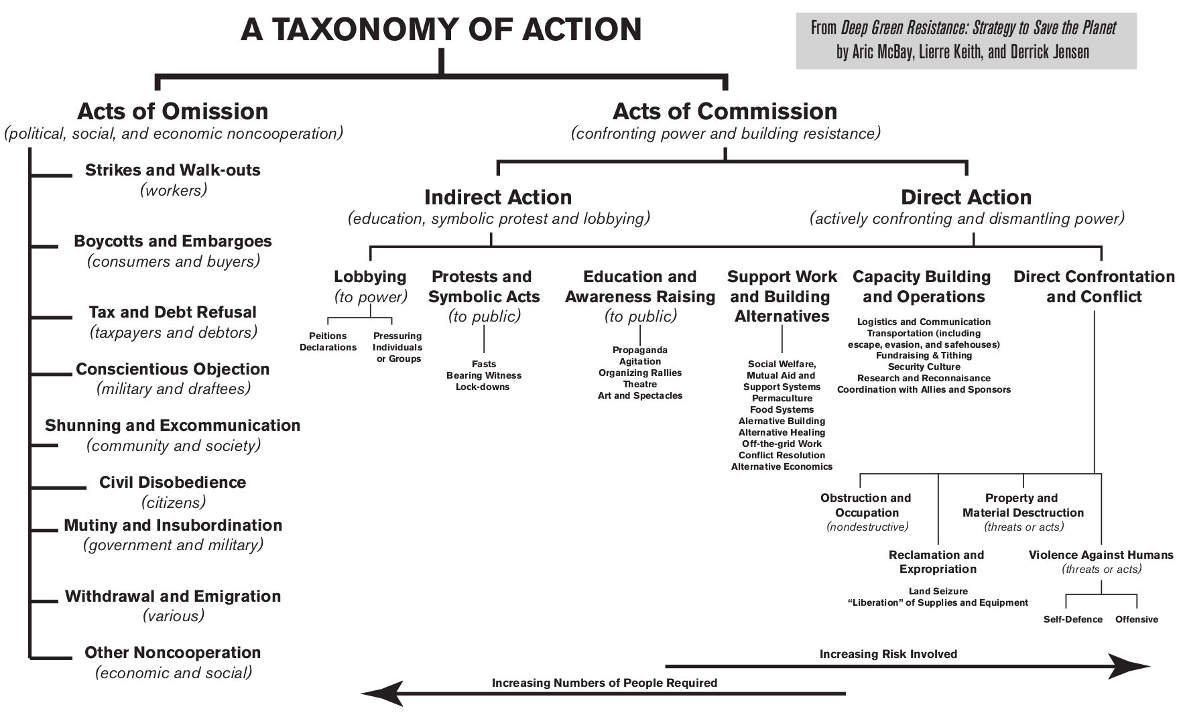

Figure 6-1. Click for larger image.

We’ve all seen biological taxonomies, which categorize living organisms by kingdom and phylum down to genus and species. Though there are tens of millions of living species of vastly different shapes, sizes, and habitats, we can use a taxonomy to quickly zero in on a tiny group.

When we seek effective strategies and tactics, we have to sort through millions of past and potential actions, most of which are either historical failures or dead ends. We can save ourselves a lot of time and a lot of anguish with a quick and dirty resistance taxonomy. By looking over whole branches of action at once we can quickly judge which tactics are actually appropriate and effective for saving the planet (and for many specific kinds of social and ecological justice activism). A taxonomy of action can also suggest tactics we might otherwise overlook.

Broadly speaking, we can divide all of our tactics and projects either into acts of omission or acts of commission. Of course, sometimes these categories overlap. A protest can be a means to lobby a government, a way of raising public awareness, a targeted tactic of economic disruption, or all three, depending on the intent and organization. And sometimes one tactic can support another; an act of omission like a labor strike is much more likely to be effective when combined with propagandizing and protest.

In a moment we’ll do a quick tour of our taxonomic options for resistance. But first, a warning. Learning the lessons of history will offer us many gifts, but these gifts aren’t free. They come with a burden. Yes, the stories of those who fight back are full of courage, brilliance, and drama. And yes, we can find insight and inspiration in both their triumphs and their tragedies. But the burden of history is this: there is no easy way out.

In Star Trek, every problem can be solved in the final scene by reversing the polarity of the deflector array. But that isn’t reality, and that isn’t our future. Every resistance victory has been won by blood and tears, with anguish and sacrifice. Our burden is the knowledge that there are only so many ways to resist, that these ways have already been invented, and they all involve profound and dangerous struggle. When resisters win, it is because they fight harder than they thought possible.

And this is the second part of our burden. Once we learn the stories of those who fight back—once we really learn them, once we cry over them, once we inscribe them in our hearts, once we carry them in our bodies like a war veteran carries aching shrapnel—we have no choice but to fight back ourselves. Only by doing that can we hope to live up to their example. People have fought back under the most adverse and awful conditions imaginable; those people are our kin in the struggle for justice and for a livable future. And we find those people—our courageous kin—not just in history, but now. We find them among not just humans, but all those who fight back.

We must fight back because if we don’t we will die. This is certainly true in the physical sense, but it is also true on another level. Once you really know the self-sacrifice and tirelessness and bravery that our kin have shown in the darkest times, you must either act or die as a person. We must fight back not only to win, but to show that we are both alive and worthy of that life.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 30, 2018 | Obstruction & Occupation

by Three Sisters Resistance Camp

Greetings, from so-called Virginia.

The unholy and hated corporate leviathan known as Dominion Energy has begun felling trees for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a project poised to cross hundreds of rivers and streams and bore underneath the Appalachian Trail. Dominion’s ACP (along with EQT’s Mountain Valley Pipeline) disproportionately target communities of color and working class families in Appalachia. These projects have been rammed through via Dominion’s political and economic monopoly over every aspect of Virginia’s energy economy.

Dominion has already commenced with clearing and surveying using crews from Utah and Texas, despite their ear numbing promises of jobs for Virginians. We send out cheerful greetings to comrades everywhere.

Water Is Life! Death to the Black Snake!

– Three Sisters Camp

ACP Resistance at Three Sisters Camp from Three Sisters on Vimeo.