Green Deceit: Forest Management, EVs, and Manufactured Consent

Editor’s Note: Taking the context of Maryland’s forests, the following piece analyses how the mainstream environmental movement and pro-industry management actors have used deliberately misinterpreting to outright creation of information to justify commercial activities at the expense of forests. Industrial deforestation is harmful for the forests and the planet. The fact that this obvious piece of information should even be stated to educated adults affirms the successful (and deceitful) framing of biomass as an environmentally friendly way out of climate crisis. The same goes for deep sea mining.

By Austin

Most would agree that we live in an age of multiple compounding catastrophes, planetary in scale. There is controversy, however, regarding their interrelationships as well as their causes. That controversy is largely manufactured. In the following pages I will describe the state of “forestry” in the state of Maryland, USA, and connect that to regional, national, and international stirrings of which we should all be aware. I will continue to examine connections between international conservation organizations, the co-optation of the environmental movement, the youth climate movement, and the financialization of nature. Full disclosure. I am writing this to human beings on behalf of all the non-human beings and those yet unborn who are recognized as objects to be converted to capital or otherwise used by the dominant culture. I am not a capitalist. I am a human being. I occupy unceded land of unrecognized peoples which is characterized by poisoned air, water and soil, devastated forest ecosystems, decapitated mountains, and collapsing biodiversity. I am of this earth. It is to the land, water and all of life that I direct my affection and gratitude as well as my loyalty.

Last winter, amid deep concerns about the present mass extinction and an unshakeable feeling of helplessness, I began to search for answers and ecological allies. I compiled a running list of local, regional, national, and international organizations that seemed to have at least some interest in the environment. The list quickly swelled to hundreds of entries. I attempted to assess the organizations based upon their mission, values, goals, publications and other such things. I hoped that the best of the best of these groups could be brought together around ecological restoration and the long-term benefits of clean air, water, healthy soil supporting vigorous growth of food and medicine, and rebounding biodiversity throughout our Appalachian homeland. Progress was and continues to be slow. Along the way, I encountered an open stakeholder consultation (survey) regarding a risk assessment of Maryland’s forests. As an ethnobotanist with special interests in forest ecology and stewardship, Indigenous societies and their traditional ecological knowledge, symbiotic relationships, and intergenerational sustainability, I realize that my unique perspectives could be helpful to the team conducting the assessment. I proceeded to submit thought provoking responses to each question. Because the consultation period was exceedingly brief and outreach to stakeholders was weak at best, and because the wording of the questions felt out of alignment with the purported purpose of the survey, I sensed that something was awry. So I saved my answers and resolved to stay abreast of developments.

Summer came around, I became busy, and the risk assessment survey faded from my mind until a friend recently emailed me a draft of the document along with notice of a second stakeholder consultation and the question: should we respond? This friend happens to own land registered in the Maryland Tree Farm Program. The selective outreach to forest landowners with large acreage was an indication as to who is and who is not considered a “stakeholder” by the committee.

After reviewing the Consultation Draft: A Sustainability Risk Assessment of Maryland’s Forests I felt sick. Low to Negligible was the risk assignment for every single criteria. I re-read the document – section by section – noting the ambiguity, legalese and industry jargon, lack of definitions, contradictory statements, false claims, poorly referenced and questionable sources, and more. Have you heard of greenwashing? Every tactic was represented in the 82 page document. Naturally, then, I tracked down and reviewed many of the referenced materials and I then investigated the contributors and funders of the report.

To understand the Sustainability Risk Assessment of Maryland’s Forests, one must also review the <a href=”https://ago-item-storage.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/90fbcb6e1acd4f019ad608f77ac2f19c/Final_Forestry_EAS_FullReport_10-2021.pdfMaryland Forestry Economic Adjustment Strategy, part one and two of Maryland Department of Natural Resources Forest Action Plan, and Seneca Creek Associates, LLC’s Assessment of Lawful Sourcing and Sustainability: US Hardwood Exports, and of course American Forests Foundation’s Final Report to the Dutch Biomass Certification Foundation (DBC) for Implementation of the AFF’s 2018 DBC Stimulation Program in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, and Louisiana. Additionally, it is helpful to note that the project development lead and essential supporters each operate independent consultancies that: offer “technical and strategic support in navigating complex forest sustainability and climate issues,” “provide(s) services in natural resource economics and international trade,” and “produced a comprehensive data research study for the Dutch Biomass Certification Foundation on the North American forest sector,” according to their websites.

Noting, furthemore, that on the Advisory Committee sits a member of the Maryland Forests Association (MFA). On their website they state: “We are proud to represent forest product businesses, forest landowners, loggers and anyone with an interest in Maryland’s forests…” They also state: “Currently, Maryland’s Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard uses a limiting definition of qualifying biomass that makes it difficult for wood to compete against other forms of renewable energy,” oh yes, and this extraordinarily deceptive bit from a recent publication, There’s More to our Forests than Trees:

When the tree dies, it decays and releases carbon dioxide and methane back into the atmosphere. However, we can postpone this process and extend the duration of carbon storage. If we harvest the tree and build a house or even make a chair with the wood, the carbon remains stored in these products for far longer than the life of the tree itself! This has tremendous implications for addressing the growing levels of carbon dioxide, which lead to increased warming of the earth’s atmosphere. It means harvesting trees for long-term uses helps mitigate climate change. We can even take advantage of the fact that trees sequester carbon at different rates throughout their lifespan to maximize the carbon storage potential. Trees are more active in sequestering carbon when they are younger. As forests age, growth slows down and so does their ability to store carbon. At some point, a stand of trees reaches an equilibrium where the growth and carbon-storing ability equals the trees that die and release carbon each year. Thus, a younger, more vigorous stand of trees stores carbon at a much higher rate than an older one.

Just in case you were convinced by that last bit, my studies in botany and forest ecology support the following finding:

“In 2014, a study published in Nature by an international team of researchers led by Nathan Stephenson, a forest ecologist with the United States Geographical Survey, found that a typical tree’s growth continues to accelerate (emphasis mine) throughout its lifetime, which in the coastal temperate rainforest can be 800 years or more.

Stephenson and his team compiled growth measurements of 673,046 trees belonging to 403 tree species from tropical, subtropical and temperate regions across six continents. They found that the growth rate for most species “increased continuously” as they aged.

“This finding contradicts the usual assumption that tree growth eventually declines as trees get older and bigger,” Stephenson says. “It also means that big, old trees are better at absorbing carbon from the atmosphere than has been commonly assumed.” (Tall and old or dense and young: Which kind of forest is better for the climate?).

Al Goertzl, president of Seneca Creek (a shadowy corporation with a benign name that has no website and pumps out reports justifying the exploitation of forests) who is featured in MFA’s Faces of Forestry, wouldn’t know the difference, he identifies as a forest economist. In another publication marketing North American Forests he is credited with the statements: “There exists a low risk that U.S. hardwoods are produced from controversial sources as defined in the Chain of Custody standard of the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC).” and “The U.S. hardwood-producing region can be considered low risk for illegal and non-sustainable hardwood sourcing as a result of public and private regulatory and non-regulatory programs.” The report then closes with this shocker: “SUSTAINABILITY MEANS USING NORTH AMERICAN HARDWOODS.”

Why are forest-pimps conducting the risk assessment upon which future decisions critical to the long-term survival of our native ecosystem will be based? What is really going on here?

A noteworthy find from Forest2Market helps to clarify things:

“Europe’s largest single source of renewable energy is sustainable biomass, which is a cornerstone of the EU’s low-carbon energy transition […] For the last decade, forest resources in the US South have helped to meet these goals—as they will in the future. This heavily forested region exported over <7 million metric tons of sustainable wood pellets in 2021 – primarily to the EU and UK – and is on pace to exceed that number in 2022 (emphasis mine) due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, which has pinched trade flows of industrial wood pellets from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.”

Sustainability means using North American hardwoods.

If it has not yet become clear, the stakeholder consultation for the forest sustainability risk assessment document which inspired this piece was but a small, local, component of an elaborate sham enabling the world to burn and otherwise consume the forests of entire continents – in comfort and with the guilt-neutralizing reassurance that: carbon is captured, rivers are purified, forests are healthy and expanding, biodiversity is thriving and protected, and “the rights of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples are upheld” as a result of our consumption. (FSC-NRA-USA, p71) That is the first phase of the plan – manufacturing / feigning consent. Next the regulatory hurdles must be eliminated or circumvented. Cue the Landscape Management Plan (LMP).

“Taken together, the actions taken by AFF [American Forest Foundation] over the implementation period have effectively set the stage for the implementation of a future DBC project to promote and expand SDE+1 qualifying certification systems for family landowners in the Southeast US and North America, generally.”

“As outlined in our proposal, research by AFF and others has demonstrated that the chief barrier for most landowners to participating in forest certification is the requirement to have a forest management plan. To address this significant challenge, AFF has developed an innovative tool, the Landscape Management Plan (LMP). An LMP is a document produced through a multi-stakeholder process that identifies, based on an analysis of geospatial data and existing regional conservation plans, forest conservation priorities at a landscape scale and management actions that can be applied at a parcel scale. This approach also utilizes publicly available datasets on a range of forest resources, including forest types, soils, threatened and endangered species, cultural resources and others, as well as social data regarding landowner motivations and practices. As a document, it meets all of the requirements for ATFS certification and is fully supported by PEFC and could be used in support of other programs such as other certification systems, alongside ATFS. Once an LMP has been developed for a region, and once foresters are trained in its use, the LMP allows landowners to use the landscape plan and derive a customized set of conservation practices to implement on their properties. This eliminates the need for a forester to write a complete individualized plan, saving the forester time and the landowner money. The forester is able to devote the time he or she would have spent writing the plan interacting with the landowner and making specific management recommendations, and / or visiting additional landowners.

With DBC support, AFF sought to leverage two existing LMPs in Alabama and Florida and successfully expanded certification in those states. In addition, AFF combined DBC funds with pre-existing commitments to contract with forestry consultants to design new LMPs in Arkansas and Louisiana. DBC grant funds were used to cover LMP activities between July 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018 for these states, namely stakeholder engagement, two stakeholder workshops (one in each state Arkansas and Louisiana) and staffing.” (American Forest Foundation, 2, 7).

It is clear that global interests / morally bankrupt humans have been busy ignoring the advice of scientists, altering definitions, removing barriers to standardization / certification, and manufacturing consent; thus enabling the widespread burning of wood / biomass (read: earth’s remaining forests) to be recognized as renewable, clean, green-energy. Imagine: mining forests as the solution to deforestation, biodiversity loss, pollution, climate change, and economic stagnation. Meanwhile, mountains are scalped, rivers are poisoned, forests are gutted, biological diversity is annihilated, and the future of all life on earth is sold under the guise of sustainability.

Sustainability means USING North American hardwoods!

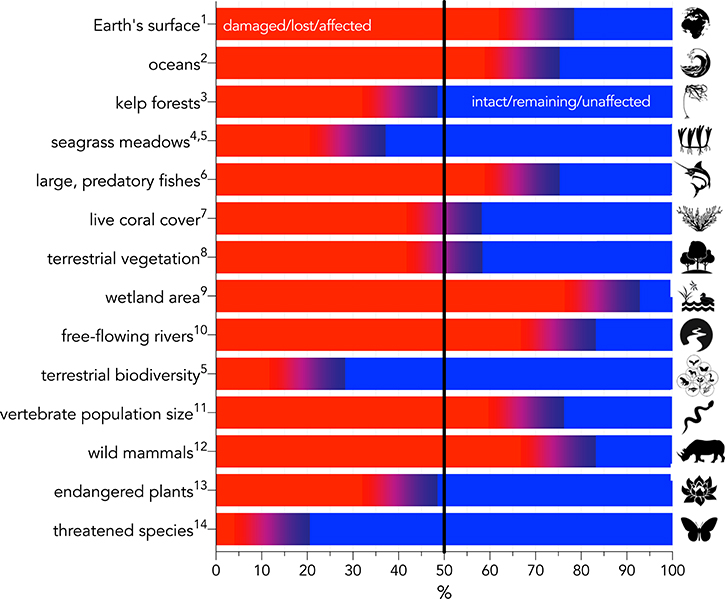

The perpetual mining of forests is merely one “natural climate solution” promising diminishing returns for Life on earth. While the rush is on to secure the necessary public consent (but not of the free, prior, and informed variety) to convert the forests of the world into clean energy (sawdust pellets) and novel materials, halfway around the planet and 5 kilometers below the surface of the Pacific another “nature based solution” that will utterly devastate marine ecosystems and further endanger life on earth – deep sea mining (DSM) – is employing the same strategy. Like the numerous other institutions that are formally entrusted with the protection of forests, water, air, biodiversity, and human rights, deep sea mining is overseen by an institution which has contradictory directives – to protect and to exploit. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has already issued 17 exploration contracts and will begin issuing 30-year exploitation contracts across the 1.7 million square mile Clarion-Clipperton zone by 2024 – despite widespread calls for a ban / moratorium and fears of apocalyptic planetary repercussions. After decades of environmental protection measures enacted by thousands of agencies and institutions throwing countless billions at the “problems,” every indicator of planetary health that I am aware of has declined. It follows, then, that these institutions are incapable of exercising caution, acting ethically, protecting ecosystems, biodiversity or indigenous peoples, holding thieves, murderers and polluters accountable, or even respecting their own regulatory processes. Haeckel sums up industry regulation nicely in a recent nature article regarding the nascent DSM industry:

“…Amid this dearth of data, the ISA is pushing to finish its regulations next year. Its council met this month in Kingston, Jamaica, to work through a draft of the mining code, which covers all aspects — environmental, administrative and financial — of how the industry will operate. The ISA says that it is listening to scientists and incorporating their advice as it develops the regulations. “This is the most preparation that we’ve ever done for any industrial activity,” says Michael Lodge, the ISA’s secretary-general, who sees the mining code as giving general guidance, with room to develop more progressive standards over time.

And many scientists agree. “This is much better than we have acted in the past on oil and gas production, deforestation or disposal of nuclear waste,” says Matthias Haeckel, a biogeochemist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany.” (Seabed Mining Is Coming — Bringing Mineral Riches and Fears of Epic Extinctions).

Of course, this “New Deal for Nature” requires “decarbonization” while producing billions of new electric cars, solar panels, wind mills, and hydroelectric dams. The metals for all the new batteries and techno-solutions have to come from somewhere, right? According to Global Sea Mineral Resources:

“Sustainable development, the growth of urban infrastructure and clean energy transition are combining to put enormous pressure on metal supplies.

Over the next 30 years the global population is set to expand by two billion people. That’s double the current populations of North, Central and South America combined. By 2050, 66 percent of us will live in cities. To support this swelling urban population, a city the size of Dubai will need to be built every month until the end of the century. This is a staggering statistic. At the same time, there is the urgent need to decarbonise the planet’s energy and transport systems. To achieve this, the world needs millions more wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicle batteries.

Urban infrastructure and clean energy technologies are extremely metal intensive and extracting metal from our planet comes at a cost. Often rainforests have to be cleared, mountains flattened, communities displaced and huge amounts of waste – much of it toxic – generated.

That is why we are looking at the deep sea as a potential alternative source of metals.”

Did you notice how there is scarcely room to imagine other possibilities (such as reducing our material and energy consumption, reorganizing our societies within the context of our ecosystems, voluntarily decreasing our reproductive rate, and sharing resources) within that narrative?

Do you still wonder why the processes of approving seabed mining in international waters and certifying an entire continent’s forests industry to be sustainable seem so similar? They are elements of the same scheme: a strategy to accumulate record profits through the valuation and exploitation of nature – aided and abetted by the non-profit industrial complex.

“The non-profit industrial complex (or the NPIC) is a system of relationships between: the State (or local and federal governments), the owning classes, foundations, and non-profit/NGO social service & social justice organizations that results in the surveillance, control, derailment, and everyday management of political movements.

The state uses non-profits to: monitor and control social justice movements; divert public monies into private hands through foundations; manage and control dissent in order to make the world safe for capitalism; redirect activist energies into career-based modes of organizing instead of mass-based organizing capable of actually transforming society; allow corporations to mask their exploitative and colonial work practices through “philanthropic” work; and encourage social movements to model themselves after capitalist structures rather than to challenge them.” (Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex | INCITE!).

The emergence of the NPIC has profoundly influenced the trajectory of global capitalism largely by inventing new conservation and the youth climate movement –

The “movement” that evades all systemic drivers of climate change and ecological devastation (militarism, capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, patriarchy, etc.). […] The very same NGOs which set the Natural Capital agenda and protocols (via the Natural Capital Coalition, which has absorbed TEEB2) – with the Nature Conservancy and We Mean Business at the helm, are also the architects of the term “natural climate solutions”. (THE MANUFACTURING OF GRETA THUNBERG – FOR CONSENT: NATURAL CLIMATE MANIPULATIONS [VOLUME II, ACT VI]).

In the words of artist Hiroyuki Hamada:

“What’s infuriating about manipulations by the Non Profit Industrial Complex is that they harvest the goodwill of the people, especially young people. They target those who were not given the skills and knowledge to truly think for themselves by institutions which are designed to serve the ruling class. Capitalism operates systematically and structurally like a cage to raise domesticated animals. Those organizations and their projects which operate under false slogans of humanity in order to prop up the hierarchy of money and violence are fast becoming some of the most crucial elements of the invisible cage of corporatism, colonialism and militarism.” (THE MANUFACTURING OF GRETA THUNBERG – FOR CONSENT: THE GREEN NEW DEAL IS THE TROJAN HORSE FOR THE FINANCIALIZATION OF NATURE [ACT V]).

We must understand that the false solutions proposed by these institutions will suck the remaining life out of this planet before you can say fourth industrial revolution.

“That is, the privatization, commodification, and objectification of nature, global in scale. That is, emerging markets and land acquisitions. That is, “payments for ecosystem services”. That is the financialization of nature, the corporate coup d’état of the commons that has finally come to wait on our doorstep.” (THE MANUFACTURING OF GRETA THUNBERG – FOR CONSENT: NATURAL CLIMATE MANIPULATIONS [VOLUME II, ACT VI].

An important point must never get lost amongst the swirling jargon, human-supremacy and unbridled greed: If we do not drastically reduce our material and energy consumption – rapidly – then We (that is, all living beings on the planet including humans) have no future.

In summary, decades of social engineering have set the stage for the blitzkrieg underway against our life-giving and sustaining mother planet in the name of sustainability industrial civilization. The success of the present assault requires the systematic division, distraction, discouragement, detention, and demonization (reinforced by powerful disinformation) and ultimately the destruction of all those who would resist. Remember also: capital, religion, race, gender, class, ideology, occupation, private property, and so forth, these are weapons of oppression wielded against us by the dominant patriarchal, colonizing, ecocidal, empire. That is not who We are. Our causes, our struggles, and our futures are one. Unless we refuse to play by their rules and coordinate our efforts, We will soon lose all that can be lost.

Learn more about deep sea mining (here); sign the Blue Planet Society petition (here) and the Pacific Blue Line statement (here). Tell the forest products industry that they do not have our consent and that you and hundreds of scientists see through their lies (here); divest from all extractive industry, and invest in its resistance instead (here). Inform yourself, talk to your loved-ones and community members and ask yourselves: what can we do to stop the destruction?

All flourishing is mutual. The inverse is also true.

“…future environmental conditions will be far more dangerous than currently believed. The scale of the threats to the biosphere and all its lifeforms—including humanity—is in fact so great that it is difficult to grasp for even well-informed experts […] this dire situation places an extraordinary responsibility on scientists to speak out candidly and accurately when engaging with government, business, and the public.” – Top Scientists: We Face “A Ghastly Future”

—Austin is an ecocentric Appalachian ethnobotanist, gardener, forager, and seed saver. He acknowledges kinship with and responsibility to protect all life, land, water, and future generations—

1 (SDE++): Sustainable Energy Transition Subsidy

2 The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity

Banner photo by Rachel Wente-Chaney on Creative Commons

Saba, also a founding member of Deep Green Resistance, is a longtime radical feminist, environmentalist, and anti-racist organizer. She studies herbal medicine and loves to spend time in the forest with her children.

Saba, also a founding member of Deep Green Resistance, is a longtime radical feminist, environmentalist, and anti-racist organizer. She studies herbal medicine and loves to spend time in the forest with her children.

![An Inconvenient Apocalypse [Review]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2022/11/yaoqi-7iatBuqFvY0-unsplash-1080x675.jpg)