![Tribe, Ranchers Say Proposed Lithium Mine in Wikieup Will ‘Ruin’ Their Water [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/dsc_8868.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Jun 22, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Toxification

This article originally appeared on the Protect Thacker Pass Blog.

Featured image: Photo of Damon Clarke, chairman of the Hualapai Tribe by Josh Kelety

Thacker Pass gets a mention in this article in the Phoenix New Times about another proposed lithium mine in Arizona, one that would use the same sulfuric acid leaching process that the Thacker Pass lithium mine would use. It’s also yet another mine threatening the water and land of indigenous people.

“The brewing tension surrounding the project in Wikieup represents a broader fight over lithium mining that is taking place in other states. Increasing use of electric cars and renewable energy has caused demand for lithium to soar, with projections for even more needed in the near future. But some observers are raising red flags, like in Wikieup, about the potential harmful environmental impacts of lithium mines.”

In this case the mining company is Hawkstone Mining, another foreign mining company (Australian, like Jindalee, the mining company that wants to mine lithium just across the OR border from Thacker Pass).

As members of the Hualapai Tribe noted, the mining would disturb their cultural sites (just like the Thacker Pass mine would disturb the cultural sites of the Paiute Shoshone people), and could use up or contaminate ground water in a state in the middle of extraordinary drought.

“There is no water in the state of Arizona. Everyone is fighting for water. Here, in this area, it’s arid and there’s not a lot of water. Whatever water there is here has already been taken by farming and ranching. To allow a big industry to come in that’s going to use tons of water and ruin our water system … then it’s a big problem. This place can’t support something that uses a lot of water, whether it’s lithium or not. We’re all in support of changing our consumption of fossil fuels. But at the cost of the environment just to get that for more cellphones and whatever else, it’s a problem.”

— Hualapai Tribe Councilmember Richard Powskey

Peehee mm’huh / Thacker Pass is a special, unique and wonderful place. AND our effort at Thacker Pass is representative of a growing struggle throughout the American West as mining companies ramp up to meet projected lithium demand for EV batteries and energy storage and an ever-increasing number of devices.

As we said when we began this fight: this is just the beginning. We take a stand at Peehee mm’huh for all the land and water that may otherwise be stolen for lithium for cars and gadgets and technology that we do not “need” to live well on this beautiful Earth.

Join us to #ProtectThackerPass and all the other lands under threat from mining.

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

![Tribal Members Aim to Stop Lithium Nevada Corporation From Digging Up Cultural Sites in Thacker Pass [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/SageGrouse-980x667-1.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Jun 15, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

Fort McDermitt, Nevada – As soon as July 29, 2021, Lithium Nevada Corporation (LNC) plans to begin removing cultural sites, artifacts, and possibly human remains belonging to the ancestors of the Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples for the proposed Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine.

According to a motion for preliminary injunction filed by four environmental organizations in the case Western Watersheds Project v. United States Department of the Interior, LNC intends to begin “mechanical trenching” operations at seven undisclosed sites within the project area, each up to “40 meters” long and “a few meters deep.” The corporation also plans to dig up to 5 feet deep at 20 other undisclosed sites, all pursuant to a new historical and cultural resources plan that has never been subject to meaningful, government-to-government consultation with the affected Tribes or to National Environmental Policy Act analysis.

Daranda Hinkey, Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone tribal member and secretary of a group formed by Fort McDermitt tribal members to stop the mine, Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) states: “From an indigenous perspective, removing burial sites or anything of that sort is bad medicine. Our tribe believes we risk sickness if we remove or take those things. We simply do not want any burial sites in Thacker Pass or anywhere in the surrounding area to be taken. The ones who passed on were prayed for and therefore should stay in their place, no matter what. We need to respect these places. The people at Lithium Nevada wouldn’t go and dig up their family gravesite because they found lithium there, so why are they trying to do that to ours?”

LNC’s Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine would harm the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, their traditional land, and traditional foods like choke cherry, yapa, ground hog, and mule deer. It would also harm water, air, and wildlife including sage grouse, Lahontan cutthroat trout, pronghorn antelope, and sacred golden eagles.

Thacker Pass is named Peehee mu’huh in Paiute. Peehee mu’huh means “rotten moon” in English and was named so because Paiute ancestors were massacred there while the hunters were away. When the hunters returned, they found their loved ones murdered, unburied, rotting, and with their entrails spread across the sage brush in a part of the Pass shaped like a moon. According to the Paiute, building a lithium mine over this massacre site at Peehee mu’huh would be like building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery.

Land and water protectors have occupied the Protect Thacker Pass camp in the geographical boundaries of LNC’s open pit lithium mine since January 15. Will Falk, attorney and Protect Thacker Pass organizer, says: “Our allies, the People of Red Mountain, do not want to see their ancestors disturbed and their sacred land destroyed. We plan on stopping Lithium Nevada and BLM from digging these cultural sites up.”

On Tuesday, June 15th at 11am PST / 2pm EST, we will be phone banking to Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) to ask that she rescind (cancel) the Record of Decision for Thacker Pass, delay the project for consultation, and meet with Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) to discuss the issues here.

During this phone bank, we will be live streaming a press conference featuring Fort McDermitt tribal members and other concerned people. Please join us by filling out the information on this form and join us to #ProtectPeeheeMu’huh / #ProtectThackerPass!

SIGN UP HERE: https://forms.gle/z4Y2w2dKaw7WMHwE6

Event hosted by People of Red Mountain, One Source Network, Moms Clean Air Force, and Protect Thacker Pass. Please share widely!

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

by DGR News Service | May 19, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Listening to the Land, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home, Toxification, White Supremacy

In this statement, Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (the People of Red Mountain), oppose the proposed Lithium open pit mines in Thacker Pass. They describe the cultural and historical significance of Thacker Pass, and also the environmental and social problems the project will bring.

We, Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (the People of Red Mountain) and our native and non-native allies, oppose Lithium Nevada Corp.’s proposed Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine.

This mine will harm the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, our traditional land, significant cultural sites, water, air, and wildlife including greater sage grouse, Lahontan cutthroat trout, pronghorn antelope, and sacred golden eagles. We also request support as we fight to protect Thacker Pass.

”Lithium Nevada Corp. (“Lithium Nevada”) – a subsidiary of the Canadian corporation Lithium Americas Corp. – proposes to build an open pit lithium mine that begins with a project area of 17,933 acres. When the Mine is fully-operational, it would use 5,200 acre-feet per year (equivalent to an average pumping rate of 3,224 gallons per minute) in one of the driest regions in the nation. This comes at a time when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation fears it might have to make the federal government’s first-ever official water shortage declaration which will prompt water consumption cuts in Nevada. Meanwhile, despite Lithium Nevada’s characterization of the Mine as “green,” the company estimates in the FEIS that, when the Mine is fully-operational, it will produce 152,703 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions every year.

Mines have already harmed the Fort McDermitt tribe.

Several tribal members were diagnosed with cancer after working in the nearby McDermitt and Cordero mercury mines. Some of these tribal members were killed by that cancer.

In addition to environmental concerns, Thacker Pass is sacred to our people. Thacker Pass is a spiritually powerful place blessed by the presence of our ancestors, other spirits, and golden eagles – who we consider to be directly connected to the Creator. Some of our ancestors were massacred in Thacker Pass. The name for Thacker pass in our language is Peehee mu’huh, which in English, translates to “rotten moon.” Pee-hee means “rotten” and mm-huh means “moon.” Peehee mu’huh was named so because our ancestors were massacred there while our hunters were away. When the hunters returned, they found their loved ones murdered, unburied, rotting, and with their entrails spread across the sage brush in a part of the Pass shaped like a moon. To build a lithium mine over this massacre site in Peehee mu’huh would be like building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery. We would never desecrate these places and we ask that our sacred sites be afforded the same respect.

Thacker Pass is essential to the survival of our traditions.

Our traditions are tied to the land. When our land is destroyed, our traditions are destroyed. Thacker Pass is home to many of our traditional foods. Some of our last choke cherry orchards are found in Thacker Pass. We gather choke cherries to make choke cherry pudding, one of our oldest breakfast foods. Thacker Pass is also a rich source of yapa, wild potatoes. We hunt groundhogs and mule deer in Thacker Pass. Mule deer are especially important to us as a source of meat, but we also use every part of the deer for things like clothing and for drumskins in our most sacred ceremonies.

Thacker Pass is one of the last places where we can find our traditional medicines.

We gather ibi, a chalky rock that we use for ulcers and both internal and external bleeding. COVID-19 made Thacker Pass even more important for our ability to gather medicines. Last summer and fall, when the pandemic was at its worst on the reservation, we gathered toza root in Thacker Pass, which is known as one of the world’s best anti-viral medicines. We also gathered good, old-growth sage brush to make our strong Indian tea which we use for respiratory illnesses.

Thacker Pass is also historically significant to our people.

The massacre described above is part of this significance. Additionally, when American soldiers were rounding our people up to force them on to reservations, many of our people hid in Thacker Pass. There are many caves and rocks in Thacker Pass where our people could see the surrounding land for miles. The caves, rocks, and view provided our ancestors with a good place to watch for approaching soldiers. The Fort McDermitt tribe descends from essentially two families who, hiding in Thacker Pass, managed to avoid being sent to reservations farther away from our ancestral lands. It could be said, then, that the Fort McDermitt tribe might not be here if it wasn’t for the shelter provided by Thacker Pass.

We also fear, with the influx of labor the Mine would cause and the likelihood that man camps will form to support this labor force, that the Mine will strain community infrastructure, such as law enforcement and human services. This will lead to an increase in hard drugs, violence, rape, sexual assault, and human trafficking. The connection between man camps and missing and murdered indigenous women is well-established.

Finally, we understand that all of us must be committed to fighting climate change. Fighting climate change, however, cannot be used as yet another excuse to destroy native land. We cannot protect the environment by destroying it.

Sign the petition from People of Red Mountain: https://www.change.org/p/protect-thacker-pass-peehee-mu-huh

Donate: https://www.classy.org/give/423060/#!/donation/checkout

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

by DGR News Service | May 9, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

By Straquez

The Colonial Years

Of course, Mexico has been in the front line of atrocities and destruction that come out of mining. Mexico is a land blessed with wide biodiversity that includes minerals that have caught the attention of foreign companies who then act as the machinery to do what this industrial culture does best –converting the living into the dead. High revenue for the company stakeholders, negative benefit for the inhabitants and nothing but endless destruction for the land.

It is said that Aztecs used to embellish and protect their bodies with jewelry, such as necklaces with charms and pedants, armlets, bracelets, leg bracelets, and rings. They would also use tools and vases fabricated with precious metals like gold and silver. These metals were found in deposits located on the surface and not underground like nowadays, this allowed the usage of such mineral resources without much effort or effect.

In 1521, Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was taken over by the Spanish army consolidating Mexico’s Conquest. From then on, mining as an industry started in Mexico as Spaniards started to exploit places where mineral deposits could be located. Mining was carried out mostly in the North and Center of what is now modern day Mexico. Many important mineral deposits started to be discovered in places that later would become famous as they would generate wealth (for whom?) and human settlements. It was only a matter of time before the land subject to mining would be turned into cities such as Guanajuato, San Luis Potosi, Zacatecas, Taxco, Chihuahua and Durango.

Mines kept spreading and mining created many jobs and wealth (I hate to be repetitive, but whose wealth?). Is there even a mention of all the evils done to the indigenous land and people? Not at all, the history of mining is portrayed as progress, as an unquestionable good thing, as a victory and in no terms as a defeat or loss. The whole History of Civilization is pretty much like that, now that I think of it.

After Independence

When the Independence movement of Mexico started in 1810, mining projects were negatively affected and had to be stopped. It was not until 1823 when the movement ended that mining activity was restarted. Remember that I mentioned my surname Straffon being from Cornwall, England? Well, it was precisely during these years that the British Real del Monte Company was established thanks to English capital. This company provided both technology and workforce, some of it straight from Cornwall to re-establish silver mines located in Real del Monte, Hidalgo. 1,500 tons of equipment including 9 steam engines with their large boilers, 5 for pumping, 2 for crushing ore and 2 for use in powering saw mills; various pumps; large cast iron pipes to connect the pumps to be placed at the bottom of the mines with the surface. And so started the rebuilding and modernization of the district’s mining industry. The Cornish miners had brought the Industrial Revolution to Mexico.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Mexico was entering a major political transformation as new laws and codes were created. During Porfirio Diaz’ administration, for example, most of the railroad infrastructure was built all through the country, focusing on the main mining centers that were already established. Then the American corporations showed up offering the means for better extraction as mines during the times of Nueva España were certainly used, but could not be exploited to their maximum because Spain lacked the technology and resources to do so.

The Fresnillo Company, Mazapil Cooper Co., Peñoles Mining Co., and Pittsburg & Mexico Tin Mining Co. were some of the companies looking to make a profit out of Mexico’s mines. Parallel industries started to rise, the economy diversified and the country’s elite dreamed of Mexico being on its way to becoming a world economy. Metallurgical processes were improved with maximum return on capital and mineral processing efficiency as the main goal. The bonanza would cease somewhat in the 1960s when the mining industry was nationalized and mine administration passed to the charge of Mexican professionals.

Then came NAFTA, and in 1992 mining laws were modified substantially in order to accommodate the demands of big national and transnational corporations. Compared to the prior 300 years, production of gold and silver doubled even though several communities resisted the exploitation. Social and environmental damage increased substantially as a consequence due to legal impunity and the ability of the mining organizations to trample over human rights. The Mexican Mining Law of 1992 is a unique and unconstitutional piece of legislation, and rides roughshod over earlier laws which allowed for judicial challenges and which consequently made it difficult for companies to carry on their business with impunity. The solution of the mining organizations was, of course, to create a whole web of corruption that extends to the three branches of government. We are still living the influence of NAFTA until this very day. Business as usual.

Keep on Digging

Doctor María Teresa Sánchez Salazar has set out very interesting mine “conflict maps” which consider many parameters including land conflict, environmental conflict, social conflict, labor conflict or a combination of those factors. Data shows that 75% of these conflicts have to do with land, that is, land grabs by the mining companies or due to environmental conflicts, and almost 70% of them happen in open-pit mines. Another interesting number – 60% of the conflicts have involved foreign company owned mines.

She adds that there are places where conflict started due to land grab and the subsequent leasing to mining companies and the implementation of ways to displace people from their native lands. Of a total of 181 natural areas, 57 have been leased for mining. Eight of them focus more than 75% of the surface to this activity. Twenty of them have at least 93% of their surface leased. One example is the Rayón National Park in Michoacan, its land is practically 100% leased for mining as well as Huautla Mountain Range that is between Morelos, Puebla and Guerrero.

Safety is also an issue for the Mexican mining sector. There are powerful cartels that have quite an influence in the entire country, including mining states such as Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa and Guerrero. Mines have been object of many armed robberies that have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Extortion, threats and employee kidnapping have been the most common crimes reported by the mining companies.

If this was a Robin Hood kind of deal then I should certainly support it, but in the end workers are the most affected, operations are seldom slowed down and the exploitation just does not stop. If the criminal gangs were to take over, not much would change as, let’s be honest, both companies and cartels pretty much operate the same way but at a different scale.

Bacadéhuachi

In times prior to the year 1600, this area was inhabited by Opata indigenous settlements. In the year 1645 a mission named San Luis Gonzága de Bacadéhuachi was founded by the Jesuit missionary Cristóbal García. Its current inhabitants dedicate their lives to taking care of livestock and making cheese, bread and tortillas which are sold among themselves; within the world economy, they don’t have much of a choice. Being only 270 kilometers away from Hermosillo, capital of the State of Sonora, the road takes 5 hours to transit due to the uneven and complex terrain that in turn makes it a dangerous travel.

This town is on the same route of the high mountain range that takes you to Chihuahua, its neighbor state. This is a high-risk road as armed conflicts are constantly raging between groups that are looking to take control of this area. Some months ago, armed men went into the municipality creating such a situation and ending the peaceful environment to the point that the Mexican National Guard and the State Police now have to be constantly present.

Bacadehuachi has around 500 houses, most of them made of adobe, occupied by around 1,083 people according to the The National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). It has cobblestone roads and few are made of concrete due to the minimal vehicle transit. It is more common to see people on horses or donkeys than in motor vehicles. Everything is around the corner, there are no gas stations nearby. It has 3 municipal police officers that issue around 10 different fines a year. There is only one health center for basic checkups and a doctor is available every 3 days.

Regarding education, only one preschool, one primary school and one secondary school exist. For those who want to receive higher education, their only choice is to go to Granados, a municipality 50 kilometers away from the town. The road is risky to say the least, young students must stay at the neighboring town and go back to their families at the weekends in a municipality sponsored bus. To go to college is a victory, a luxury, a rare occurrence for the townspeople.

Don’t Know What I’m Selling

Miguel Teran is a farmer and former owner of La Ventana ranch. He sold his land to Bacanora Lithium for the Sonora Lithium Project. He asserts that the first explorations started back in 1994. Geologists came to the La Ventana ranch in government cars. They took some soil samples, came back 8 years later, measured the land and after that they never came back. Ten years ago, Bacanora Lithium carried out some studies. They drilled around 115 holes with the permission of Miguel and then they offered to buy the land.

I told them: you know what you’re buying, but I don’t know what I’m selling. Don’t take advantage of me. That’s how the negotiation started, but they wanted to pay as if it was a mere piece of land.”

Miguel wasn’t disappointed yet he acknowledges that he could have made a better deal as he has since found out what treasure lies in the 1,900 hectares that were sold and integrated into the Sonora Lithium Project. For the time being and until the mineral is extracted, Miguel may allow his cows to graze there as stipulated in the contract.

I am within my rights until I get in the way, but I have already bought some land.” Finally, he adds, “sometimes my car battery would fail and they would tell me that I had lithium here, but I only know about horses and chickens; not lithium.”

The Trauma of Our Technological Selves

As a city-dweller, my experience with Nature has been for the most part parks and decorative gardens. Since I live so disconnected from the land itself, I can only enter into relationship with my own species, our creations and the animals we call pets. For a long time I’ve been scared of insects and even though working in a garden has helped diminish the feeling, I still feel uncomfortable in certain scenarios. Soil and its minerals are even weirder to me, because I had never considered them something other than a resource, a component that can be used for my benefit through technology. They don’t seem alive, they don’t seem to have any other purpose than sitting there for us to transform them into something else.

Perhaps my biggest realization during my journey to connect with the land is the enormous damage that Capitalism, Colonialism and Industrialism have inflicted on the planet. It has reached the point that we are also physically, psychologically, emotionally and spiritually bent and broken enough for us to barely notice the indifference and violence around us. Indifference and violence done to each other and to ourselves. And yet, those who notice don’t always take action. Even less, those who know and take action don’t have a clear idea, much less a strategy to stop the abuse.

This is not something that modern technology can fix. Not the electric cars, not the solar cells nor the electric batteries. Not the tote bags and the bamboo toothbrushes that you can use as compost. Our home is being gutted and we just stand there watching, unsure on what to do. When you actually want to stop a killer, you go ahead and do it. You don’t offer knives from recycled metal or whips made out of hemp. You go ahead and put an end to the abuse by neutralizing any capacity to inflict damage that the perpetrator might have. You stop the killing, you stop the behavior, you commit yourself to do so.

Today I read that only 3% of world’s ecosystems remain intact. Civilization is going down regardless of what we do. Nothing can grow indefinitely without collapsing. The real question is what will be left when our civilization goes down. Our struggle resides in stopping it before there is nothing left.

Cristopher Straffon Marquez a.k.a. Straquez is a theater actor and language teacher currently residing in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Artist by chance and educator by conviction, Straquez was part of the Zeitgeist Movement and Occupy Tijuana Movement growing disappointed by good intentions misled through dubious actions. He then focused on his art and craft as well as briefly participating with The Living Theatre until he stumbled upon Derrick Jensen’s Endgame and consequently with the Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet both changing his mind, heart and soul. Since then, reconnecting with the land, decolonizing the mind and fighting for a living planet have become his goals.

by DGR News Service | May 4, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Toxification

In this article Rebecca Wildbear talks about how civilization is wasting our planet’s scarce water sources for mining in its desperate effort to continue this devastating way of life.

By Rebecca Wildbear

Nearly a third of the world lacks safe drinking water, though I have rarely been without. In a red rock canyon in Utah, backpacking on a week-long wilderness training in my mid-twenties, it was challenging to find water. Eight of us often scouted for hours. Some days all we could find to drink was muddy water. We collected rain water and were grateful when we found a spring.

Now water is scarce, and the demand for it is growing. Globally, water use has risen at more than twice the rate of population growth and is still increasing. Ninety percent of water used by humans is used by industry and agriculture, and when groundwater is overused, lakes, streams and rivers dry up, destroying ecosystems and species, harming human health, and impacting food security. Life on Earth will not survive without water.

In the Navajo Nation in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico, a third of houses lack running water, and in some towns, it is ninety percent. Peabody Energy Corporation, the largest coal producer and a Fortune 500 company, pulled so much water from the Navajo aquifer before closing its mining operation that many wells and springs have run dry. Residents now have to drive 17 miles to wait in line for an hour at a communal well, just to get their drinking water.

Worldwide, the majority of drinkable water comes from underground reservoirs called aquifers. Aquifers feed streams, lakes, and rivers, but their waters are finite. Large aquifers exist beneath deserts, but these were created eons ago in wetter times. Expert hydrologists say that like oil, once the “fossil” waters of ancient reservoirs are mined, they are gone forever.

Peabody’s Black Mesa Mine extracted, pulverized, and mixed coal with water drawn from the Navajo aquifer to form a slurry. This was sent along a 273-mile-long pipeline to the Mojave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, to power Los Angeles. Every year, the mine extracted 1.4 billion gallons (4,000+ acre feet) of water from the aquifer, an estimated 45 billion gallons (130,000+ acre feet) in all.

Pumping out an aquifer draws down the water level and empties it forever. Water quality deteriorates and springs and soil dry out. Agricultural irrigation and oil and coal extraction are the biggest users of waters from aquifers in the U.S. Some predict that the Ogallala aquifer, once stretching beneath five mid-western states, may be able to replenish after six thousand years of rainfall.

Rain is the most accurate measure of available water in a region, yet over-pumping water beyond its capacity to refill is widespread in the western U.S. and around the world. The Middle East ran out of water years ago—it was the first major region in the world to do so. Studies predict that two thirds of the world’s population are at risk of water shortages by 2025. As ground water levels fall, lakes, rivers, and streams are depleted, and the land, fish, trees, and animals die, leaving a barren desert.

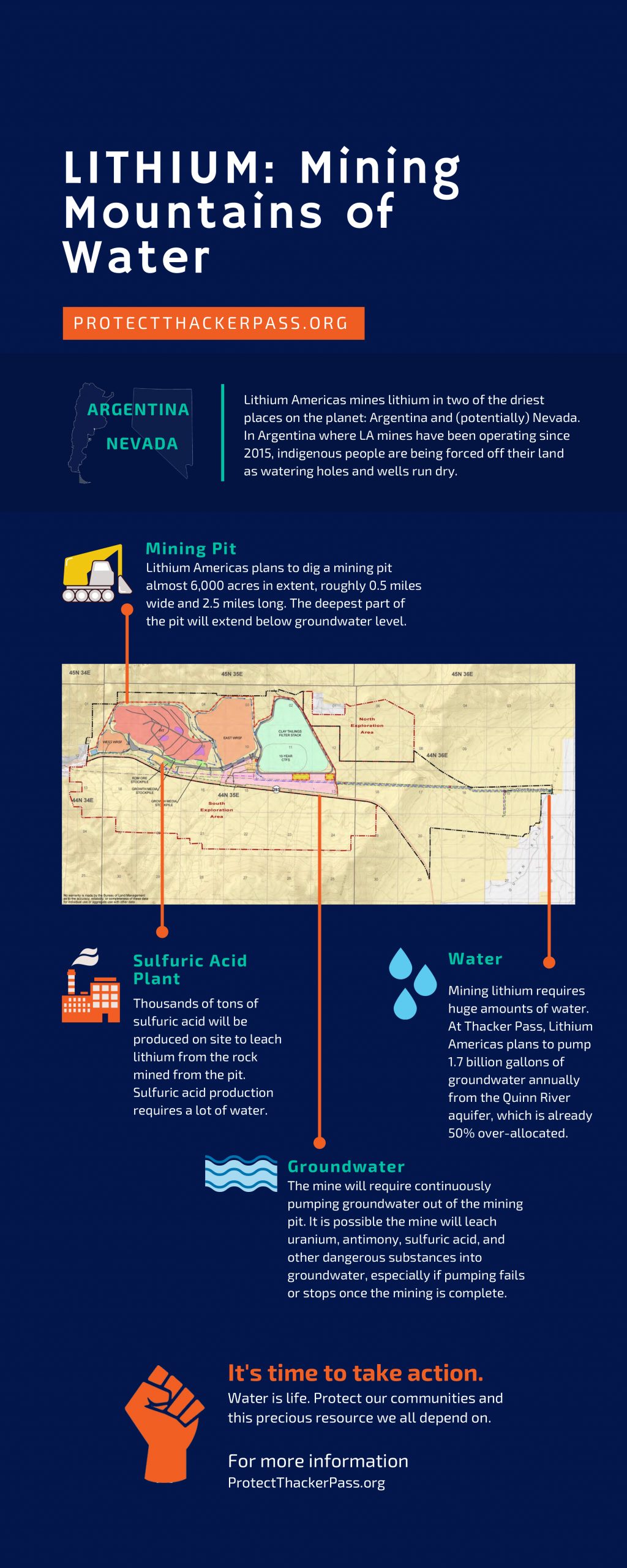

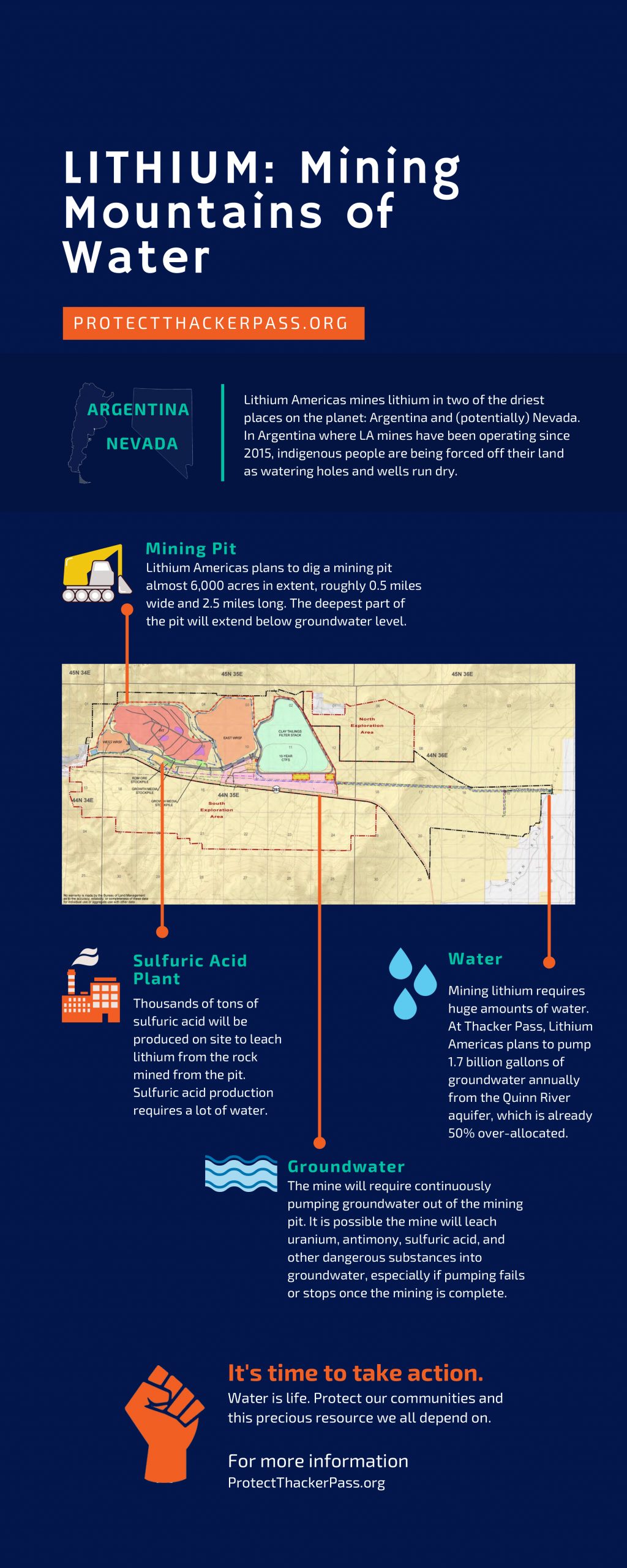

Mining in the Great Basin

The skyrocketing demand for lithium, one of the minerals needed for the production of electric cars, is based on the misperception that green technology helps the planet. Yet, as Argentine professor of thermodynamics and lithium mining expert Dr. Daniel Galli said at a scientific meeting, lithium mining is “really mining mountains of water.” Lithium Americas plans to pump massive amounts of water—up to 1.7 billion gallons (5,200 acre feet) annually—from an aquifer in the Quinn River Valley in Nevada’s Great Basin, the largest desert in the United States.

Thacker Pass, the site of the proposed 1.3 billion dollar open-pit lithium mine, would pump 1,200 acre feet more water per year than Peabody Energy Corporation extracted from the Navajo aquifer. Yet, the Quinn River aquifer is already over-allocated by fifty percent, and more than 10 billion gallons (30,000 acre feet) per year. Nevada is one of the driest states in the nation, and Thacker Pass is only the first of many proposed lithium mines in the state. Multiple active placer claims (7,996) have been located in 18 different hydrographic basins.

Deceit about water fuels these mines. Lithium Americas’ environmental impact assessment is grossly inaccurate, according to hydrologist Dr. Erick Powell. By classifying year-round creeks as “ephemeral” and underreporting the flow rate of 14 springs, Lithium Americas is claiming there is less water in the area than there actually is. This masks the real effects the mine would have—drying up hundreds of square miles of land, drawing down the groundwater level, sucking water from neighboring aquifers—all while claiming its operations would have no effect.

Peabody Energy Corporation’s impact assessment similarly misrepresented how their withdrawals would harm the Navajo aquifer. Peabody Energy used a flawed method to measure the withdrawals, according to former National Science Research Fellow Daniel Higgins. Now Navajo Nation wells require drilling down 2,000–3,000 feet, and the water is depressurized and slow to flow to the surface.

Thacker Pass lithium mine would pump groundwater at a disturbing rate, up to 3,250 gallons per minute. Once used, wastewater would contaminate local groundwater with dangerous heavy metals, including a “plume” of antimony that would last at least 300 years. Lithium Americas plans to dig the mine deeper than the groundwater level and keep it dry by continuously pumping water out, but when the pumping stops, groundwater would seep back in, picking up the toxins.

It hurts me to think about this. I imagine water being rapidly extracted from my own body, my bloodstream poisoned. The best tasting water rises to the surface when it is ready, after gestating as long as it likes in the dark Earth. Springs are sacred. When I feel welcome, I place my lips on the earthy surface and fill my mouth with their sweet flavor and vibrant texture.

Mining in the Atacama Desert

Thirteen thousand feet above sea level, the indigenous Atacamas people live in the Atacama Desert, the most arid desert in the world and the driest place on Earth. For millennia, they have used their scarce supply of water and sparse terrain carefully. Their laws and spirituality have always been intertwined with the health and well-being of the land and water. Living in mud-brick homes, pack animals, llama and alpaca, provide them with meat, hide, and wool.

But lithium lies beneath their ancestral land. Since 1980, mining companies have made billions in the Salar de Atacama region in Chile, where lithium mining now consumes sixty-five percent of the water. Some local communities need to have water driven in, and other villagers have been forced to abandon their settlements. There is no longer enough water to graze their animals. Beautiful lagoons hundreds of flamingos call home have gone dry. The birds have disappeared, and the ground is hard and cracked.

In addition to the Thacker Pass mine proposal, Lithium Americas has a mine in the Atacama Desert, a joint Canadian-Chilean venture named Minera Exar in the Cauchari-Olaroz basin in Jujuy, Argentina. Digging for lithium began in Jujuy in 2015, and there is already irreversible damage, according to a 2018 hydrology report. Watering holes have gone dry, and indigenous leaders are scared that soon there will be nothing left.

Even more water is needed to mine the traces of lithium found in brine than in an open-pit mine. At the Sales de Jujuy plant, the wells pump at a rate of more than two million gallons per day, even though this region receives less than four inches of rain a year. Pumping water from brine aquifers decreases the amount of fresh groundwater. Freshwater refills the spaces emptied by brine pumping and is irreversibly mixed with brine and salinized.

The Sanctity of Water

As a river guide, I live close to water. Swallowed by its wild beauty, I am restored to a healthier existence. Far from roads, cars, and cities, I watch water swirl around rocks or ripple over sand. I merge with its generous flow, floating through mountains, forest, or canyon. Rivers teach me how to listen to the currents—whether they cascade in a playful bubble, swell in a loud rush, or ebb in a gentle silence—for clues about what lies ahead.

The indigenous Atacamas peoples understand that water is sacred and have purposefully protected it for centuries. Rather than looking at how nature can be used, our culture needs to emulate the Atacamas peoples and develop the capacity to consider its obligations around water. Instead of electric cars, what we need is an ethical approach to our relationship with the land. Honoring the rights of water, species, and ecosystems is the foundation of a sustainable society. Decisions can be made based on knowledge of the land, weather patterns, and messages from nature.

For millennia, indigenous peoples have perceived water, animals, and mountains as sentient. If humans today could recognize their intelligence, perhaps they would understand that underground reservoirs have a value and purpose, beyond humans. When I enter a cave, I am walking into a living being. My eyes adjust to the dark. Pressing my hand against the wall, I steady myself on the uneven ground, hidden by varying amounts of water. Pausing, I listen to a soft dripping noise, echoing like a heartbeat as dew slides off the rocks. I can almost hear the cave breathing.

The life-giving waters of aquifers keep everything alive, but live unseen under the ground. As a soul guide, I invite people to be nourished by the visions of their dreams, a parallel world that is also seemingly invisible. Our dominant culture dismisses the value of these perceptions, just as it usurps water by disregarding natural cycles. Yet to create a sustainable world, humans need to be able to listen to nature and their dreams. The depths of our souls are inextricably linked to the ancient waters that flow underground. Dreams arise like springs from an aquifer, seeding our visionary potential, expanding our consciousness, and revealing other ways to live, radically different than empire.

Water Bearers

I set my backpack down on a high sandstone cliff overlooking a large watering hole. Ten feet below the hole, the red rock canyon drops into a much larger pool. My friend hikes down to it, filling her cookpot with water. She balances it atop her head on the way up, moving her hips to keep the pot steady. Arriving back, she pours the water into the smaller hole from which we drink and returns to the large pool to gather more.

Women in all societies have carried water throughout history. In many rural communities, they still spend much of the day gathering it. Sherri Mitchell of the Penobscot Nation calls women “the water bearers of the Universe.” The cycles in a woman’s body move in relation with the Earth’s tides, guiding them to nourish and protect the waters of Earth. We all need to become water bearers now.

Indigenous peoples, who have always been the Earth’s greatest defenders, protect eighty percent of global diversity, even though they comprise less than five percent of the world’s population. They understand water is sacred, and the world’s groundwater systems must be defended. For six years, indigenous peoples have been fighting to prevent lithium mining in the Salinas Grandes salt flats, in Jujuy, Argentina. Five hundred indigenous people camped on the land with signs: “No to lithium. Yes, to water and life in our territories.”

In February 2021, President Biden signed executive orders supporting the domestic mining of “critical” minerals like lithium, but two lawsuits, one by five Nevada-based conservation groups, have been filed against the Bureau of Land Management for approving the Thacker Pass lithium mine. Environmentalists Max Wilbert and Will Falk are organizing a protest to protect Thacker Pass. Local residents, including Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples, are speaking out, fighting to protect their land and water.

We can see when a river runs dry, but most people are not aware of the invisible, slow-burning disaster happening under the ground. Some say those who oppose lithium mining should give up cell phones. If that is true, perhaps those who favor mines should give up drinking water. Protecting water needs to be at the center of any plan for a sustainable future.

The “fossil water” found in deserts should be used only in emergency, certainly not for mining. Sickened by corporate water grabbing, I support those trying to stop Thacker Pass Lithium mine and aim to join them. The aquifers there have nurtured so many for so long—eagles, pronghorn antelope, mule deer, old-growth sagebrush, hawks, falcons, sage-grouse, and Lahontan cutthroat trout. I pray these sacred wombs of the Earth can live on to nourish all of life.

For more on the issue:

![Tribe, Ranchers Say Proposed Lithium Mine in Wikieup Will ‘Ruin’ Their Water [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/dsc_8868.jpg)

![Tribal Members Aim to Stop Lithium Nevada Corporation From Digging Up Cultural Sites in Thacker Pass [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/SageGrouse-980x667-1.jpg)