by DGR News Service | Oct 25, 2019 | Male Supremacy, Women & Radical Feminism

Editors note: Gerda Lerner (1920-2013) was a historian, author and teacher. She was a professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and a visiting scholar at Duke University. Lerner was one of the founders of the field of women’s history, and was a former president of the Organization of American Historians. She taught what is considered to be the first women’s history course in the world at the New School for Social Research in 1963.

This excerpt comes from the final chapter of the book The Creation of Patriarchy (1983), and summarizes portions of the preceding chapters. While some of Lerner’s claims may in retrospect be overly optimistic (for example, she could not have predicted the explosion in internet pornography as a primary sex-education tool of patriarchy), the book as a whole is a excellent introduction to the topic of patriarchy and its origins.

By Gerda Lerner

Patriarchy is a historic creation formed by men and women in a process which took nearly 2500 years to its completion. In its earliest form patriarchy appeared as the archaic state. The basic unit of its organization was the patriarchal family, which both expressed and constantly generated its rules and values. We have seen how integrally definitions of gender affected the formation of the state. Let us briefly review the way in which gender became created, defined, and established.

The roles and behavior deemed appropriate to the sexes were expressed in values, customs, laws, and social roles. They also, and very importantly, were expressed in leading metaphors, which became part of the cultural construct and explanatory system.

The sexuality of women, consisting of their sexual and their reproductive capacities and services, was commodified even prior to the creation of Western civilization. The development of agricutlure in the Neolithic period fostered the inter-tribal “exchange of women,” not only as a means of avoiding incessant warfare by the cementing of marriage alliances but also because societies with more women could produce more children. In contrast to the economic needs of hunting/gathering societies, agriculturists could use the labor of children to increase production and accumulate surpluses. Men-as-a-group had rights in women which women-as-a-group did not have in men. Women themselves became a resource, acquired by men much as the land was acquired by men. Women were exchanged or bought in marriages for the benefit of their families; later, they were conquered or bought in slavery, where their sexual services were part of their labor and where their children were the property of their masters. In every known society it was women of conquered tribes who were first enslaved, whereas men were killed. It was only after men had learned how to enslave the women of groups who could be defined as strangers, that they then learned how to enslave men of those groups and, later, subordinates from within their own societies.

Thus, the enslavement of women, combining both racism and sexism, preceded the formation of classes and class oppression. Class differences were, at their very beginnings, expressed and constituted in terms of patriarchal relations. Class is not a separate construct from gender; rather, class is expressed in genderic terms.

By the second millennium B.C. in Mesopotamian societies, the daughters of the poor were sold into marriage of prostitution in order to advance the economic interests of their families. The daughters of men of property could command a bride price, paid by the family of the groom to the family of the bridge, which frequently enabled the bride’s family to secure more financially advantageous marriages for their sons, thus improving the family’s economic position. If a husband or father could not pay his debt, his wife and children could be used as pawns, becoming debt slaves to the creditor. These conditions were so firmly established by 1750 B.C. that Hammurabic law made a decisive improvement in the lot of debt pawns by limiting their terms of service to three years, where earlier it had been for life.

The product of this commodification of women—bridge price, sale price, and children—was appropriated by men. It may very well represent the first accumulation of private property. The enslavement of women of conquered tribes became not only a status symbol for nobles and warriors, but it actually enabled the conquerors to acquire tangible wealth through selling or trading the product of the slaves’ labor and their reproductive product, slave children.

…

To step outside of patriarchal thought means: Being skeptical toward every known system of thought; being critical of all assumptions, ordering values and definitions.

Testing one’s statement by trusting our own, the female experience. Since such experience has usually been trivialized or ignored, it means overcoming the deep-seated resistance within ourselves toward accepting ourselves and our knowledge as valid. It means getting rid of the great men in our heads and substituting for them ourselves, our sisters, our anonymous foremothers.

Being critical toward our own thought, which is, after all, thought trained in the patriarchal tradition. Finally, it means developing intellectual courage, the courage to stand alone, the courage to reach farther than our grasp, the courage to risk failure. Perhaps the greatest challenge to thinking women is the challenge to move from the desire for safety and approval to the most “unfeminine” quality of all—that of intellectual arrogance, the supreme hubris which asserts to itself the right to reorder the world. The hubris of the god-makers, the hubris of the male system-builders.

The system of patriarchy is a historic construct; it has a beginning; it will have an end. Its time seems to have nearly run its course—it no longer serves the needs of men or women and in its inextricable linkage to militarism, hierarchy, and racism it threatens the very existence of life on earth.

What will come after, what kind of structure will be the foundation for alternate forms of social organization we cannot yet know. We are living in an age of unprecedented transformation. We are in the process of becoming. But we already know that woman’s mind, at last unfettered after so many millennia, will have its share in providing vision, ordering, solutions. Women at long last are demanding, as men did in the Renaissance, the right to explain, the right to define. Women, thinking themselves out of patriarchy add transforming insights to the process of redefinition.

As long as both men and women regard the subordination of half the human race to the other as “natural,” it is impossible to envision a society in which differences do not connote either dominance or subordination. The feminist critique of the patriarchal edifice of knowledge is laying the groundwork for a correct analysis of reality, one which at the very least can distinguish the whole from a part. Women’s History, the essential tool in creating feminist consciousness in women, is providing the body of experience against which new theory can be tested and the ground on which women of vision can stand.

A feminist world-view will enable women and men to free their minds from patriarchal thought and practice and at last to build a new world free of dominance and hierarchy, a world that is truly human.

by DGR News Service | Aug 5, 2019 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Male Supremacy, The Solution: Resistance, Women & Radical Feminism

Editors Note: This essay by Deep Green Resistance co-founder Lierre Keith was originally published on the DGR News Service in August 2015 under the title, “The Girls and the Grasses.” We think it an exceptional piece, and would like to share it again. [Photo by Max Wilbert, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.]

by Lierre Keith

Captured in a test tube, blood may look like a static liquid, but it’s alive, as animate and intelligent as the rest of you. It also makes up a great deal of you: of your 50 trillion cells, one-quarter are red blood cells. Two million are born every second. On their way to maturation, red blood cells jettison their nuclei―their DNA, their capacity to divide and repair. They have no future, only a task: to carry the hemoglobin that will hold your oxygen. They don’t use the oxygen themselves–they only transport it. This they do with exquisite precision, completing a cycle of circulation through your body every twenty seconds for a hundred days. Then they die.

The core of hemoglobin is a molecule of iron. It’s the iron that grasps the oxygen at the surface of your lungs, hangs on through the rush of blood, then releases it to wanting cells. If iron goes missing, the body, as ever, has a fallback plan. It adds more water to increase blood volume; thin blood travels faster through the fine capillaries. Do more with less.

All good except there’s less and less oxygen offered to the cells. Another plan kicks in: increased cardiac output. The heart ups its stroke volume and its rate. To keep you from exploding, the brain joins in, sending signals to the muscles enfolding each blood vessel, telling them to relax. Now blood volume can increase with blood pressure stable.

But still no iron arrives. At this point, the other organs have to cooperate, giving up blood flow to protect the brain and heart. The skin makes major sacrifices, which is why anemics are known for their pallor. Symptoms perceived by the person―you―will probably increase as your tissues, and then organs, begin to starve.

If there is no relief, ultimately all the plans will fail. Even a strong heart can only strain for so long. Blood backs up into the capillaries. Under the pressure, liquid seeps out into surrounding tissues. You are now swelling and you don’t know why. Then the lungs are breached. The alveoli, the tiny sacs that await the promise of air, stiffen from the gathering flood. It doesn’t take much. The sacs fill with fluid. Your body is drowning itself. This is called pulmonary edema, and you are in big trouble.

I know this because it happened to me. Uterine fibroids wrung a murder scene from me every month; the surgery to remove them pushed me across the red cell Rubicon. I knew nothing: my body understood and responded. My eyes swelled, then my ankles, my calves. Then I couldn’t breathe. Then it hurt to breathe. I finally stopped taking advice from my dog―Take a nap! With me!–and dragged myself to the ER, where, eventually, all was revealed.

Two weeks later, the flood had subsided, absorbed back into some wetland tissue of my body, and I felt the absence of pain as a positive. Breathing was exquisite, the sweetest thing I could imagine. Every moment of effortless air was all I could ever want. I knew it would fade and I would forget. But for a few days, I was alive. And it was good.

Our bodies are both all we have and everything we could want. We are alive and we get to be alive. There is joy on the surface of the skin waiting for sunlight and soft things (both of which produce endorphins, so yes: joy). There is the constant, stalwart sound of our hearts. Babies who are carried against their mothers’ hearts learn to breathe better than those who aren’t. There is the strength of bone and the stretch of muscle and their complex coordination. We are a set of electrical impulses inside a watery environment: how? Well, the nerves that conduct the impulses are sheathed by a fatty substance called myelin―they’re insulated. This permits “agile communication between distant body parts.” Understand this: it’s all alive, it all communicates, it makes decisions, and it knows what it’s doing. You can’t possibly fathom its intricacies. To start to explore the filigree of brain, synapse, nerve, and muscle is to know that even the blink of your eyes is a miracle.

Our brains were two million years in the making. That long, slow accretion doubled our cranial capacity. And the first thing we did with it was say thank you. We drew the megafauna and the megafemales, sculpted and carved them. The oldest known figurative sculpture is the Goddes of Hohle Fels, and 40,000 years ago someone spent hundreds of hours carving Her. There is no mystery here, not to me: the animals and the women gave us life. Of course they were our first, endless art project. Awe and thanksgiving are built into us, body and brain. Once upon a time , we knew we were alive. And it was good.

__________

And now we leave the realm of miracles and enter hell.

Patriarchy is the ruling religion of the planet. It comes in variations―some old, some new, some ecclesiastical, some secular. But at bottom, they are all necrophilic. Erich Fromm describes necrophilia as “the passion to transform that which is alive into something unalive; to destroy for the sake of destruction; the exclusive interest in all that is purely mechanical.” In this religion, the worst sin is being alive, and the carriers of that sin are female. Under patriarchy, the female body is loathsome; its life-giving fat-cells vilified; its generative organs despised. Its natural condition is always ridiculed: normal feet must be turned into four-inch stubs; rib cages must be crushed into collapse; breasts are varyingly too big or too small or excised entirely. That this inflicts pain―if not constant agony―is not peripheral to these practices. It’s central. When she suffers, she is made obedient.

Necrophilia is the end point of sadism. The sadistic urge is about control–“the passion to have absolute and unrestricted control over a living being,” as Fromm defined it. The objective of inflicting pain and degradation is to break a human being. Pain is always degrading; victimization humiliates; eventually, everyone breaks. The power to do that is the sadist’s dream. And who could be more broken to your control than a woman who can’t walk?

Some nouns: glass, scissors, razors, acid. Some verbs: cut, scrape, cauterize, burn. These nouns and verbs create unspeakable sentences when the object is a seven-year-old girl with her legs forced open. The clitoris, with its 8,000 nerve endings, is always sliced up. In the most extreme forms of FGM, the labia are cut off and the vagina sewn shut. On her wedding night, the girl’s husband will penetrate her with a knife before his penis.

You don’t do this to a human being. You do it to an object. That much is true. But there is more. Because the world is full of actual objects—cardboard boxes and abandoned cars—and men don’t spend their time torturing those. They know we aren’t objects, that we have nerves that feel and flesh that bruises. They know we have nowhere else to go when they lay claim to our bodies. That’s where the sadist finds his pleasure: pain produces suffering, humiliation perhaps more, and if he can inflict that on her, it’s absolute proof of his control.

Behind the sadists are the institutions, the condensations of power, that hand us to him. Every time a judge rules that women have no right to bodily integrity—that upskirt photos are legal, that miscarriages are murder, that women should expect to be beaten—he wins. Every time the Fashion Masters make heels higher and clothes smaller, he smiles. Every time an entire class of women—the poorest and most desperate, at the bottom of every conceivable hierarchy—are declared legal commodities for sex, he gets a collective hard-on. Whether he personally uses any such women is beside the point. Society has ruled they are there for him, other men have ensured their compliance, and they will comply. He can kill one—the ultimate sex act for the sadist—and no one will notice. And no one does.

There is no stop to this, no natural endpoint. There is always another sentient, self-willed being to inflame his desire to control, so the addiction is forever fed. With other addictions, the addict bottoms out, his life becomes unmanageable, and the stark choice is stop or die. But the sadist isn’t hurting himself. There’s no looming bottom to hit, only an endless choice of victims, served up by the culture. Women are the feast at our own funeral, and he is happy to feed.

_____

If feminism was reduced to one word, it would be this: no. “No” is a boundary, spoken only by a self who claims one. Objects have neither; subjects begin at no. Feminists said no and we meant it.

The boundary of “no” extended outward, an insult to one being an injury to all: “we” is the word of political movements. Without it, women are cast adrift in a hostile, chaotic sea, holding our breath against the next Bad Thing. With the lens of feminism, the chaos snaps into sharp focus. We gave words to the Bad Things, then faced down denial and despair to see the pattern. That’s called theory. Then we demanded remedies. That’s what subjects, especially political subjects, do. Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the British suffragettes, worked at the Census Office as a birth registrar. Every day, young girls came in with their newborns. Every day, she had to ask who the father was, and every day the girls wept in humiliation and rage. Reader, you know who the fathers were. That’s why Pankhurst never gave up.

To say no to the sadist is to assert those girls as political subjects, as human beings with the standing that comes from inalienable rights. Each and every life is self-willed and sovereign; each life can only be lived in a body. Not an object to be broken down for parts: a living body. Child sexual abuse is especially designed to turn the body into a cage. The bars may start as terror and pain but they will harden to self-loathing. Instilling shame is the best method to ensure compliance: we are ashamed—sexual violation is very good at that—and for the rest of our lives we will comply. Our compliance is, of course, his control. His power is his pleasure, and another generation of girls will grow up in bodies they will surely hate, to be women who comply.

_______

What has been done to our bodies has been done to our planet. The sadist exerts his control; the necrophiliac turns the living into the dead. The self-willed and the wild are their targets and their necrotic project is almost complete.

Taken one by one, the facts are appalling. In my lifetime, the earth has lost half her wildlife. Every day, two hundred species slip into that longest night of extinction. “Ocean” is synonymous with the words abundance and plenty. Fullness is on the list, as well as infinity. And by 2048, the oceans will be empty of fish. Crustaceans are experiencing “complete reproductive failure.” In plain terms, their babies are dying. Plankton are also disappearing. Maybe plankton are too small and green for anyone to care about, but know this: two out of three animal breaths are made possible by the oxygen plankton produce. If the oceans go down, we go down with them.

How could it be otherwise? See the pattern, not just the facts. There were so many bison on the Great Plains, you could sit and watch for days as a herd thundered by. In the central valley of California, the flocks of waterbirds were so thick they blocked out the sun. One-quarter of Indiana was a wetland, lush with life and the promise of more. Now it’s a desert of corn. Where I live in the pacific northwest, ten million fish have been reduced to ten thousand. People would hear them coming for a whole day. This is not a story: there are people alive who remember it. And I have never once heard the sound that water makes when forty million years of persistence finds it way home. Am I allowed to use the word “apocalypse” yet?

The necrophiliac insists we are mechanical components, that rivers are an engineering project, and genes can be sliced up and arranged at whim. He believes we are all machines, despite the obvious: a machine can be taken apart and put back together. A living being can’t. May I add: neither can a living planet.

Understand where the war against the world began. In seven places around the globe, humans took up the activity called agriculture. In very brute terms, you take a piece of land, you clear every living thing off it, and then you plant it to human use. Instead of sharing that land with the other million creatures who need to live there, you’re only growing humans on it. It’s biotic cleansing. The human population grows to huge numbers; everyone else is driven into extinction.

Agriculture creates a way of life called civilization. Civilization means people living in cities. What that means is: they need more than the land can give. Food, water, energy have to come from someplace else. It doesn’t matter what lovely, peaceful values people hold in their hearts. The society is dependent on imperialism and genocide. Because no one willing gives up their land, their water, their trees. But since the city has used up its own, it has to go out and get those from somewhere else. That’s the last 10,000 years in a few sentences.

The end of every civilization is written into the beginning. Agriculture destroys the world. That’s not agriculture on a bad day. That’s what agriculture is. You pull down the forest, you plow up the prairie, you drain the wetland. Especially, you destroy the soil. Civilizations last between 800 and maybe 2,000 years—they last until the soil gives out.

What could be more sadistic then control of entire continents? He turns mountains into rubble, and rivers must do as they are told. The basic unit of life is violated with genetic engineering. The basic unit of matter as well, to make bombs that kill millions. This is his passion, turning the living into the dead. It’s not just individual deaths and not even the deaths of species. The process of life itself is now under assault and it is losing badly. Vertebrate evolution has long since come to a halt—there isn’t enough habitat left. There are areas in China where there are no flowering plants. Why? Because the pollinators are all dead. That’s five hundred million years of evolution: gone.

He wants it all dead. That’s his biggest thrill and the only way he can control it. According to him it was never alive. There is no self-willed community, no truly wild land. It’s all inanimate components he can arrange to this liking, a garden he can manage. Never mind that every land so managed has been lessened into desert. The essential integrity of life has been breached, and now he claims it never existed. He can do whatever he wants. And no one stops him.

__________

Can we stop him?

I say yes, but then I have no intention of giving up. The facts as they stand are unbearable, but it’s only in facing them that pattern comes clear. Civilization is based on drawdown. It props itself up with imperialism, conquering its neighbors and stripping their land, but eventually even the colonies wear out. Fossil fuel has been an accelerant, as has capitalism, but the underlying problem is much bigger than either. Civilization requires agriculture, and agriculture is a war against the living world. Whatever good was in the culture before, ten thousand years of that war has turned it necrotic.

But what humans do they can stop doing. Granted every institution is headed in the wrong direction, there’s no material reason the destruction must continue. The reason is political: the sadist is rewarded, and rewarded well. Most leftists and environmentalists see that. What they don’t see is the central insight of radical feminism: his pleasure in domination.

The real brilliance of patriarchy is right here: it doesn’t just naturalize oppression, it sexualizes acts of oppression. It eroticizes domination and subordination and then institutionalizes them into masculinity and femininity. Men become real men by breaking boundaries—the sexual boundaries of women and children, the cultural and political boundaries of indigenous people, the biological boundaries of rivers and forests, the genetic boundaries of other species, and the physical boundaries of the atom itself. The sadist is rewarded with money and power, but he also gets a sexual thrill from dominating. And the end of the world is a mass circle jerk of autoerotic asphyxiation.

The real brilliance of feminism is that we figured that out.

What has to happen to save our planet is simple: stop the war. If we just get out of the way, life will return because life wants to live. The forests and prairies will find their way back. Every dam will fail, every cement channel, and the rivers will ease their sorrows and meet the ocean again. The fish will know what to do. In being eaten, they feed the forest, which protects the rivers, which makes a home for more salmon. This is not the death of destruction but the death of participation that makes the world whole.

Sometimes there are facts that require all the courage we have in our hearts. Here is one. Carbon has breached 400 ppm. For life to continue, that carbon needs to get back into the ground. And so we come to grasses.

Where the world is wet, trees make forests. Where it’s dry, the grasses grow. Grasslands endure extreme heat in summer and vicious cold in winter. Grasses survive by keeping 80 percent of their bodies underground, in the form of roots. Those roots are crucial to the community of life. They provide physical channels for rain to enter the soil. They can reach down fifteen feet and bring up minerals from the rocks below, minerals that every living creature needs. They can build soil at an extraordinary rate. The base material they use to make soil is carbon. Which means the grasses are our only hope to get that carbon out of the sky.

And they will do it if we let them. If we could repair 75 percent of the world’s grasslands—destroyed by the war of agriculture—in under fifteen years, the grasses would sequester all the carbon that’s been released since the beginning of the industrial age. Read that again if you need to. Then take it with you wherever you go. Tell it to anyone who will listen. There is still a chance.

The grasses can’t do it alone. No creature exists independent of all others. Repairing the grasslands means restoring the ruminants. In the hot, dry summer, life goes dormant on the surface of the soil. It’s the ruminants who keep the nutrient cycle moving. They carry an ecosystem inside themselves, especially the bacteria that digests cellulose. When a bison grazes, she’s not actually eating the grass. She’s feeding it to her bacteria. The bacteria eat the grass and then she eats the bacteria. Her wastes then water and fertilize the grasses. And the circle is complete.

The grasslands have been eradicated for agriculture, to grow cereal grains for people. Because I want to restore the grasses, I get accused of wanting to kill six billion people. That’s not a random number. In 1800, at the beginning of the Industrial Age, there were one billion people. Now there are seven billion. Six billion are only here because of fossil fuel. Eating a non-renewable resource was never a plan with a future. Yet pointing that out somehow makes me a mass murderer.

Start with the obvious. Nothing we do at these numbers is sustainable. Ninety-eight percent of the old-growth forests and 99 percent of the grasslands are gone, and gone with them was most of the soil they built. There’s nothing left to take. The planet has been skinned alive.

Add to that: all civilizations end in collapse. All of them. How could it be otherwise if your way of life relies on destroying the place you live? The soil is gone and the oil is running out. By avoiding the facts, we are ensuring it will end in the worst possible way.

We can do better than mass starvation, failed states, ethnic strife, misogyny, petty warlords, and the dystopian scenarios that collapse brings. It’s very simple: reproduce at less than replacement numbers. The problem will take care of itself. And now we come to the girls.

What drops the birthrate universally is raising the status of women. Very specifically, the action with the greatest impact is teaching a girl to read. When women and girls have even that tiny bit of power over their lives, they choose to have fewer children. Yes, women need birth control, but what we really need is liberty. Around the world, women have very little control over how men use our bodies. Close to half of all pregnancies are unplanned or unwanted. Pregnancy is the second leading cause of death for girls age 15-19. Not much has changed since Emmeline Pankhurst refused to give up.

We should be defending the human rights of girls because girls matter. As it turns out, the basic rights of girls are crucial to the survival of the planet.

Can we stop him?

Yes, but only if we understand what we’re up against.

He wants the world dead. Anything alive must be replaced by something mechanical. He prefers gears, pistons, circuits to soft animal bodies, even his own. He hopes to upload himself into a computer some day.

He wants the world dead. He enjoys making it submit. He’s erected giant cities where once were forests. Concrete and asphalt tame the unruly.

He wants the world dead. Anything female must be punished, permanently. The younger they are, the sooner they break. So he starts early.

A war against your body is a war against your life. If he can get us to fight the war for him, we’ll never be free. But we said every woman’s body was sacred. And we meant it, too. Every creature has her own physical integrity, an inviolable whole. It’s a whole too complex to understand, even as we live inside it. I had no idea why my eyes were swelling and my lungs were aching. The complexities of keeping me alive could never be left to me.

One teaspoon of soil contains a million living creatures. One tiny scoop of life and it’s already more complex than we could ever understand. And he thinks he can manage oceans?

We’re going to have to match his contempt with our courage. We’re going to have to match his brute power with our fierce and fragile dreams. And we’re going to have to match his bottomless sadism with a determination that will not bend and will not break and will not stop.

And if we can’t do it for ourselves, we have to do it for the girls.

Whatever you love, it is under assault. Love is a verb. May that love call us to action.

Lierre Keith is the author of six books. Visit her website at www.lierrekeith.com

This essay first appeared August 8, 2015 on RadFem Repost.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 4, 2016 | Gender

New Books Highlight the Debate between Radical Feminism and Transgender Movement

by Robert Jensen

Within feminism there has been for decades an often divisive debate about transgenderism. With increasing mainstream news media and pop culture attention focused on the issue, understanding that feminist debate is more important than ever.

Two new feminist books that analyze transgenderism (Sheila Jeffreys’ Gender Hurts: A Feminist Analysis of the Politics of Transgenderism and Michael Schwalbe’s Manhood Acts: Gender and the Practices of Domination, which includes a chapter on “The Limits of Trans Liberalism”) are helpful for those who are concerned about the harms that result from the imposition of traditional gender roles but do not embrace the ideological assumptions and assertions of the transgender movement.

The propositions below are not taken directly from those books, whose authors may not agree with my phrasings. I am not trying to summarize their arguments but instead hope to bring greater clarity to the debate with a concise account of my position, which is rooted in a radical feminist analysis of sex and gender. I present these ideas as a series of propositions to make it easier for readers to identify where they may agree or disagree.

Biological and Cultural

We are a sexually dimorphic species, male and female. Although there is variation, the vast majority of humans are born with distinctly male or female reproductive systems, sexual characteristics, and/or chromosomal structure. Intersex people are born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit the definitions of female or male; the number of people in this category depends on the degree of ambiguity used to mark the category. Intersex conditions are distinct from transgenderism.

The biological differences between males and females that are tied to reproduction are not trivial; no species can ignore reproductive realities. Not all females have children, but only females can bear and breastfeed children, which no male can do. Therefore, human communities have always, and will always, recognize two distinct sex categories, male and female. There has always been, and always will be, some sex-role differentiation in human communities.

Other observable or measurable physical differences (average height, muscle mass, etc.) between males and females may be socially relevant depending on circumstances. Sex-role differentiation based on those differences may be appropriate if it can be shown to be necessary in the interests of everyone in a society. This claim is asserted far more often that is demonstrated.

People from varying ideological positions also claim that these biological differences give rise to significant differences in moral, intellectual, or emotional characteristics between males and females. While it is plausible that differences in reproductive organs and hormones could result in these kinds of differences, there is no clear evidence for these claims. Given the complexity of the human organism and the limits of contemporary research, it’s unlikely we will gain definitive understanding of these questions in the foreseeable future. In the absence of evidence of the biological bases for moral, intellectual, or emotional differences, we should assume that all or part of any differences in observed behavior between males and females in these matters are a product of cultural training, while remaining open to alternative explanations.

In short: males and females are far more similar than different.

Patriarchy

Today’s existing sex-role differentiation is the product of a patriarchal society based on male dominance. In that system, males are socialized into patriarchal masculinity to become men, and females are socialized into patriarchal femininity to become women.

In patriarchy, sex-role differentiation supports male power and helps make the system’s domination/subordination dynamic seem natural and normal. Moral, intellectual, and emotional traits are assigned differentially to each sex, creating what we today typically call gender roles. This patriarchal system of control—which is complex, adapting to changing conditions and to resistance—is designed to justify and perpetuate male dominance.

The gender roles in patriarchy are rigid, repressive, and reactionary. These roles constrain the healthy flourishing of both males and females, but females experience by far the most significant psychological and physical injuries from the system.

In patriarchy, gender is a category that functions to establish and reinforce inequality.

Radical Feminism

In contemporary culture, “radical” is often used dismissively as a synonym for “crazy” or “extreme.” In this context, it describes an analysis that seeks to understand, address, and eventually eliminate the root causes of inequality.

Radical feminism opposes patriarchy and male dominance. Radical feminism, which challenges the naturalizing of the process by which patriarchal societies turn male/female into man/woman, rejects patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender roles.

Radical feminist politics addresses a wide range of issues, including men’s violence and sexual exploitation of women and children. Many radical feminists critique the gendered dress/grooming/presentation norms imposed on females in patriarchy, such as hyper-sexualized clothing, make-up, and ritualized behaviors of subordination, arguing for the elimination of these practices, not for males to adopt them as well.

The goal of radical feminism is a world without hierarchy, in which males and females would be free to explore the range of human experiences—especially experiences of love, whether sexual or not—in an egalitarian context.

Transgender

Transgender is defined as “A term for people whose gender identity, expression or behavior is different from those typically associated with their assigned sex at birth.” The transgender movement rejects the automatic sorting of males and females into the categories of man and woman, but does not necessarily reject gender roles. Some in the transgender movement embrace patriarchal gender roles typically attached to the cultural categories of masculinity and femininity.

While not all people who identify as transgender have sex-reassignment surgery or use hormones or other treatments to modify their bodies, the transgender movement as a whole accepts and/or embraces these practices.

Most radical feminists, who seek to eliminate patriarchy and patriarchal gender ideology, disagree with this transgender approach. Most radical feminists believe liberation is achieved through a political project that transcends patriarchal gender, rather than accepting those gender roles and merely seeking to allow people to move between the categories. Radical feminist politics focuses on challenging the patriarchal gender ideology that restricts the freedom of most individuals, especially women and others who lack power, to explore the fullest range of human experiences.

Nothing in a radical feminist analysis minimizes the social and/or psychological struggles of—nor provides support for violence against—people who identify as transgender or people who do not conform to patriarchal gender norms but do not identify as transgender. Radical feminism is not the cause of those struggles or the source of that violence but rather advocates for an egalitarian society with maximal freedom without violence.

Ecology

Many people, whether radical feminist or not, are critical of high-tech medicine’s manipulation of the body through the reckless use of hormones and chemicals (which rarely have been proved to be safe) or the destruction of healthy tissue to conform to arbitrary beauty standards (cosmetic surgery such as breast augmentation, nose jobs, etc.).

From this ecological approach, such medical practices are part of a deeper problem in the industrial era of our failing to understand ourselves as organisms, shaped by an evolutionary history, and part of ecosystems that impose limits on all organisms.

People are not machines, and treating the human body like a machine is inconsistent with an ecological understanding of ourselves as living beings who are part of a larger living world.

Public Policy

The state should not limit people’s freedom to choose, when those choices do not harm others. Disagreements can, and do, arise over identifying and assessing harms.

Transgender claims have led to a variety of policy debates, especially concerning the integrity of female-only spaces that are designed to foster a sense of safety and expressive freedom for females generally (such as cultural institutions) and particularly to create safety for females who have been victims of male violence (such as rape crisis and domestic violence centers). Forcing female-only spaces to accommodate people who identify as transgender reinforces patriarchy as a system and harms individual females.

Public funding for sex-reassignment surgery (such as through Medicare) raises serious public health questions that cannot be resolved by simplistic freedom-to-choose arguments.

Transgender practices involving children that are questionable on public health grounds (such as the use of puberty blockers) raise serious moral questions about our collective obligation for children’s welfare.

Intellectual Practice and Rhetoric

As in any contentious political debate, angry and uncivil words have been exchanged. People on all sides should be respectful and careful in choices of language.

Labeling a radical feminist position on these public policy issues as inherently “transphobic” or describing radical feminist arguments on the issues as “hate speech” are diversionary tactics that undermine productive intellectual and political discussion. A critique of an idea is not a personal attack on any individual who holds the idea.

This critical analysis does not demand that people accept these principles in constructing an individual sense of self. These propositions are relevant to such individual decisions, but are presented in the context of collective decision-making about public policy.

Conclusion

Transgenderism is a liberal, individualist, medicalized response to the problem of patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender norms. Radical feminism is a radical, structural, politicized response. On the surface, transgenderism may seem to be a more revolutionary approach, but radical feminism offers a deeper critique of the domination/subordination dynamic at the heart of patriarchy and a more promising path to liberation.

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include Arguing for Our Lives: A User’s Guide to Constructive Dialogue (City Lights, 2013) and Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity (South End Press, 2007).

by DGR News Service | Apr 27, 2025 | ANALYSIS, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: “I think we’re in the midst of a collapse of civilization, and we’re definitely in the midst of the end of the American empire. And when empires start to fail, a lot of people get really crazy. In The Culture of Make Believe, I predicted the rise of the Tea Party. I recognized that in a system based on competition and where people identify with the system, when times get tough, they wouldn’t blame the system, but instead, they would indicate it’s the damn Mexicans’ fault or the damn black people’s fault or the damn women’s fault or some other group. The thing that I didn’t predict was that the Left would go insane in its own way. I anticipated the rise of an authoritarian Right, but not authoritarianism more generally, to which the Left is not immune. The collapse of empire results in increased insecurity and the demand for stability. The cliché about Mussolini is that he made the trains run on time, that he brought about stability.” – Derrick Jensen

It’s not just stupid people. People can be very smart as individuals, but collectively we are stupid. Postmodernism is a case in point. It starts with a great idea, that we are influenced by the stories we’re told and the stories we’re told are influenced by history. It begins with the recognition that history is told by the winners and that the history we were taught through the 1940s, 50s and 60s was that manifest destiny is good, civilization is good, expanding humanity is good. Exemplary is the 1962 film How the West Was Won. It’s extraordinary in how it regards the building of dams and expansion of agriculture as simply great. Postmodernism starts with the insight that such a story is influenced by who has won, which is great, but then it draws the conclusion that nothing is real and there are only stories.

“This is the cult-like behavior of the postmodern left: if you disagree with any of the Holy Commandments of postmodernism/queer theory/transgender ideology, you must be silenced on not only that but on every other subject. Welcome to the death of discourse, brought to you by the postmodern left.”

Explainer: what is postmodernism?

Daniel Palmer, Monash University

I once asked a group of my students if they knew what the term postmodernism meant: one replied that it’s when you put everything in quotation marks. It wasn’t such a bad answer, because concepts such as “reality”, “truth” and “humanity” are invariably put under scrutiny by thinkers and “texts” associated with postmodernism.

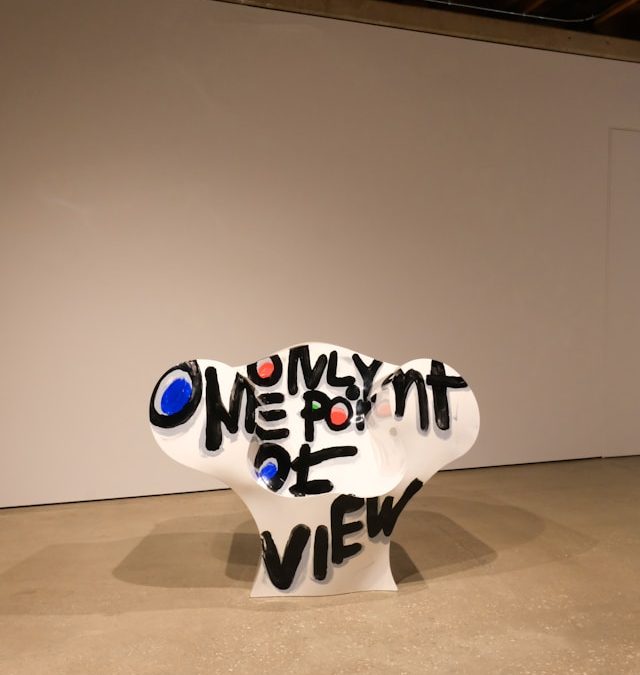

Postmodernism is often viewed as a culture of quotations.

Take Matt Groening’s The Simpsons (1989–). The very structure of the television show quotes the classic era of the family sitcom. While the misadventures of its cartoon characters ridicule all forms of institutionalised authority – patriarchal, political, religious and so on – it does so by endlessly quoting from other media texts.

This form of hyperconscious “intertextuality” generates a relentlessly ironic or postmodern worldview.

Relationship to modernism

The difficulty of defining postmodernism as a concept stems from its wide usage in a range of cultural and critical movements since the 1970s. Postmodernism describes not only a period but also a set of ideas, and can only be understood in relation to another equally complex term: modernism.

Modernism was a diverse art and cultural movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries whose common thread was a break with tradition, epitomised by poet Ezra Pound’s 1934 injunction to “make it new!”.

The “post” in postmodern suggests “after”. Postmodernism is best understood as a questioning of the ideas and values associated with a form of modernism that believes in progress and innovation. Modernism insists on a clear divide between art and popular culture.

But like modernism, postmodernism does not designate any one style of art or culture. On the contrary, it is often associated with pluralism and an abandonment of conventional ideas of originality and authorship in favour of a pastiche of “dead” styles.

Postmodern architecture

The shift from modernism to postmodernism is seen most dramatically in the world of architecture, where the term first gained widespread acceptance in the 1970s.

One of the first to use the term, architectural critic Charles Jencks suggested the end of modernism can be traced to an event in St Louis on July 15, 1972 at 3:32pm. At that moment, the derelict Pruitt-Igoe public housing project was demolished.

Built in 1951 and initially celebrated, it became proof of the supposed failure of the whole modernist project.

Jencks argued that while modernist architects were interested in unified meanings, universal truths, technology and structure, postmodernists favoured double coding (irony), vernacular contexts and surfaces. The city of Las Vegas became the ultimate expression of postmodern architecture.

Famous theorists

Theorists associated with postmodernism often used the term to mark a new cultural epoch in the West. For philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, the postmodern condition was defined as “incredulity towards metanarratives”; that is, a loss of faith in science and other emancipatory projects within modernity, such as Marxism.

Marxist literary theorist Fredric Jameson famously argued postmodernism was “the cultural logic of late capitalism” (by which he meant post-industrial, post-Fordist, multi-national consumer capitalism).

In his 1982 essay Postmodernism and Consumer Society, Jameson set out the major tropes of postmodern culture.

These included, to paraphrase: the substitution of pastiche for the satirical impulse of parody; a predilection for nostalgia; and a fixation on the perpetual present.

In Jameson’s pessimistic analysis, the loss of historical temporality and depth associated with postmodernism was akin to the world of the schizophrenic.

Postmodern visual art

In the visual arts, postmodernism is associated with a group of New York artists – including Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman – who were engaged in acts of image appropriation, and have since become known as The Pictures Generation after a 1977 show curated by Douglas Crimp.

By the 1980s postmodernism had become the dominant discourse, associated with “anything goes” pluralism, fragmentation, allusions, allegory and quotations. It represented an end to the avant-garde’s faith in originality and the progress of art.

But the origins of these strategies lay with Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, and the Pop artists of the 1960s in whose work culture had become a raw material. After all, Andy Warhol was the direct progenitor of the kitsch consumerist art of Jeff Koons in the 1980s.

Postmodern cultural identity

Postmodernism can also be a critical project, revealing the cultural constructions we designate as truth and opening up a variety of repressed other histories of modernity. Such as those of women, homosexuals and the colonised.

The modernist canon itself is revealed as patriarchal and racist, dominated by white heterosexual men. As a result, one of the most common themes addressed within postmodernism relates to cultural identity.

American conceptual artist Barbara Kruger’s statement that she is “concerned with who speaks and who is silent: with what is seen and what is not” encapsulates this broad critical project.

The discourse of postmodernism is associated with Australian artists such as Imants Tillers, Anne Zahalka and Tracey Moffatt.

Australia has been theorised by Paul Taylor and Paul Foss, editors of the influential journal Art & Text, as already postmodern, by virtue of its culture of “second-degree” – its uniquely unoriginal, antipodal appropriations of European culture.

If the language of postmodernism waned in the 1990s in favour of postcolonialism, the events of 9/11 in 2001 marked its exhaustion.

While the lessons of postmodernism continue to haunt, the term has become unfashionable, replaced by a combination of others such as globalisation, relational aesthetics and contemporaneity.

Daniel Palmer, Senior Lecturer, Art History & Theory Program, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

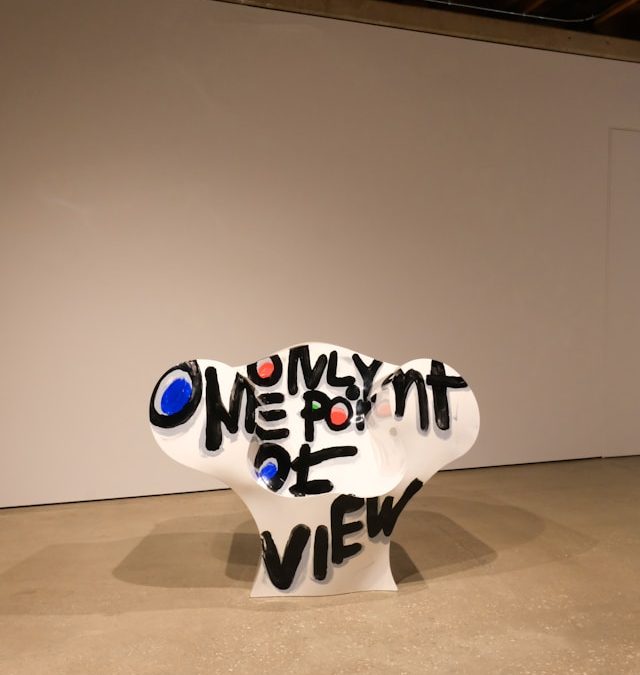

Photo by Mike Von on Unsplash

![]()