by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 10, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

Mayanga family slaughtered by illegal colonizers while planting food on traditional land

Warning: this article includes graphic images that some readers may find disturbing.

by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

In a shocking escalation of the ongoing violent conflict devastating the Indigenous binational autonomous nation of Moskitia, a Mayanga family of three was killed in a brutal attack by ‘Colonos’ at the Llano Sucio site of the Alamikamba community in the Awala Prinsu territory on November 27, 2016. The attack sent shockwaves through the already war torn territories of Moskitia.

The family’s names and ages were documented by community members; and, the Miskito community continues to seek international solidarity amidst this tragedy and related ongoing devastation. The Mayanga individuals who lost their lives in this most recent and exceptionally brutal attack, have been identified as:

Bernicia Dixon Peralta, age 30 (family and community members claim she was between 3 and 5 months pregnant);

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

Feliciano Benlis Flores, age 37;

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

And, their 11 year old son, Feliciano Benlis Dixon.

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

Reports from the community indicate the family was on the receiving end of threats from invading Colonos – heavily armed Mestizo settlers encroaching on Miskito territory, acting as agents of a large scale land grab. They also say these threats were fully realized last weekend while the family was attempting to plant seeds on their traditional land.

Eklan James Molina, mayor of Alamikamba, which is located in the municipality of Prinzapolka, has demanded a thorough investigation of the massacre. In a statement to one of the few independent news outlets in Nicaragua, La Prensa, he charged: “As mayor, I ask the police and the army to follow up on the case. You have to get to the bottom of why it [occurred].”

In the article published by La Prensa, unverified claims surfaced suggesting the deceased family’s land had been illegally sold to the violent, encroaching settlers by a mysterious third party. Nancy Elizabeth Henriquez, deputy of the YATAMA Indigenous political party – the only real political opposition to the Sandinista state in the region at this time – has dismissed such claims as already having been settled in a court of law; and, explicitly categorized this recent massacre as a revenge killing. In her statement to La Prensa, she relayed, “The owner sued and won the right [to the land] that is theirs; and the Colonos killed the entire family for revenge.” She cited ongoing ethnic clashes as one potential reason the Nicaraguan National Police continue to allow such atrocities to take place with impunity.

Moskitia, a lesser known conflict zone where the violent and heavily armed Meztizo settlers from the Pacific coast and interior of Nicaragua continue to invade traditional and legal Miskito land, has been experiencing escalations in terrorism and violence since June of 2015, according to an official statement issued by the Miskito Council of Elders in August of this year. In a statement published by The Ecologist in October, the elders explained:

“Since ancient times we’ve [cared for] our forests, because apart from being our only means of sustenance, we understand that any alteration to [them] attracts risks; alters our form of life; puts existence itself at risk; causes drastic changes [to] the climate; alters the ecosystem; and breaks our link with our ancestors.

[For] little more than five years, [we] have experienced the largest internal colonization [of] our history. The presence of ‘Colonos’ has drastically altered our form of life. In such a short time [the invasion] has destroyed tens of thousands of hectares of our forests, which has led to [the drying of] our rivers, [causing] the animals [to] migrate and the climate to alter, and us to emigrate. Our large forests are now deserts, occupied for the livestock, and [we] can do nothing to curb the advance of the settlers as they have the support of the Government of Nicaragua and [we] are alone.”

***

At this point, the much hyped November presidential election in Nicaragua has come and gone. President Daniel Ortega managed to further consolidate power and formally establish the foundations for a family dynasty and authoritarian dictatorship. All fanfare aside, Fidel Castro’s recent death means little in a pragmatic sense to the quasi-socialist, former Sandinista revolutionary, Ortega; his contradictory embrace of neoliberalism has carved out even more geopolitical space for a disturbing emerging brand of neoliberal authoritarianism – more in line with Putin’s newly conservative Russia, the theocratic regime of Iran, and the authoritarian capitalism embraced by China, than Fidel’s revolutionary ideals in Cuba. It is thus likely no coincidence that all three of the aforementioned nations have sought a stake in the notorious Nicaragua trans-oceanic canal. After mounting skepticism regarding whether the environmentally catastrophic, human rights disaster would actually come to fruition, recent reports have cited the monstrous development project may be poised to move forward after all. At least 11 non-violent protestors were recently injured amid the growing anti-canal movement.

Another recent report from La Prensa indicates the continued violent expansion of the agricultural frontier into the Indigenous nation of Moskitia – which includes the second largest tropical rainforest in the Western Hemisphere after the Amazon, referred to as the ‘lungs of Mesoamerica’ – may also be tied to Russia’s increasing imperialist presence in the region. A key player in the re-militarization of Nicaragua, Russia recently sold the impoverished nation an estimated 80 million dollars’ worth of military war tanks (some suggesting to suppress ongoing internal dissent) and is launching a strange new imperial drug war in the region. It is unclear what stake Russia has in fighting a drug war in Central America, but the La Presna report suggests that they may be hoping for a payoff in agricultural land appropriated through recent land grabs and ongoing deforestation.

Featured image: A young Miskitu girl stands before an armed indigenous resistance force in Muskitia, Nicaragua. From Ecologist Special Report: The Pillaging of Nicaragua’s Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, by Courtney Parker

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 12, 2016 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

by Brett Spencer / Intercontinental Cry

On Monday, November 7th, the day after Nicaragua’s primary elections, supporters of the Miskito indigenous party, Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka, or Sons of Mother Earth (YATAMA), took to the streets of Puerto Cabezas to celebrate a regional victory for Indigenous Peoples. It had just been announced that Brooklyn Rivera, the leader of YATAMA, had won political office.

Supporters of YATAMA celebrate news of victory during a speech by Brooklyn Rivera. Photo: Brett Spencer

Local polls concluded that YATAMA had secured the victory despite numerous allegations of electoral fraud. Nine out of twelve people IC interviewed at four polling stations in Puerto Cabezas reported the fraud in favor of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), led by Nicaragua’s current president, Daniel Ortega.

“There is serious doubt about the transparency, the cleanliness and the purity of this process,” said Mr. Rivera. Other than YATAMA, “there is no real opposition” and “no international observation of the elections,” he concluded.

Despite these allegations, YATAMA supporters planned to march across the town at 2:00 pm. However, it was learned around that time that the victory would not be acknowledged until the vote was recounted in Managua, without the presence of YATAMA officials.

The announcement created a sense of unease as the streets filled with Miskito of all demographics in support of Brooklyn Rivera’s re-election as a deputy in the National Assembly.

Mr. Rivera was ousted from office in September of 2015, following a rise in violence over an endemic land conflict between the Miskito and Sandinista settlers known to the Miskito as colonos.

Puerto Cabezas reacts to news of a YATAMA victory. Photo: Brett Spencer

The indigenous population swelled the streets with gracious enthusiasm following an optimistic speech by Mr. Rivera. However, shortly after the start of the march, police began to line the main street in riot gear, preventing the march from continuing.

Miskito youth began throwing stones at the officers and the police began firing rubber bullets into the crowd, provoking more outrage. A group of YATAMA supporters overtook the governor’s office, removing office equipment including computers. The crowd began to compile makeshift weapons to fend off the police, who began using tear gas in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

Many of the women and children took safety in a bar overlooking the conflict, only to have tear gas thrown at them by the police officers.

Police fire rubber bullets at Miskito youth: Brett Spencer

“This was suppose to be a peaceful march, but the police started instigating,” said Walt, who works at the bar where we took safety. “But the people have to march to get results around here, otherwise the result would not be the same.”

YATAMA’s supporters eventually overtook the police around 6:00 pm, who retreated to the police station. After the sun had set, a group of Miskito youth, angry with the police for stopping the march, broke into several shops owned by Sandinista supporters.

Photo: Brett Spencer

The following morning, the local Sandinista radio station, Bilwi Stereo, blamed the conflict on the participation of foreigners, discrediting the power and agency of YATAMA’s wide support base. Puerto Cabezas became militarized overnight, with trucks of heavily armed soldiers patrolling the empty streets.

The streets remained calm but ill at ease, as relations between the Miskito and the Sandinista government continue to deteriorate. “We need something better for our people,” said Hector Williams, the Wihta Tara, or “Great Judge” of the Miskito separatist movement. “This is La Moskitia, it is not Nicaragua.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 16, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Intercontinental Cry

The Southern Autonomous Region of Nicaragua is home to nine indigenous and afro-descendant communities represented by the Rama-Kriol Territorial Government.

On May 3, 2016 Rama-Kriol Territorial President Hector Thomas signed an agreement with the Nicaraguan Canal Development Commission giving consent for the indefinite lease of 173km of communal land to develop the canal.

Communal representatives have denounced this action, claiming they have not been consulted and have not seen the terms of the agreement, which would remove several communities from their ancestral land.

According to international law (ILO Convenant 169 & The UN Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) the government must obtain the free, prior and informed consent of the communities to use their land.

Over the past month, community members have given documented testimony and are organizing a formal legal appeal against this illegal land concession.

This short film documents this series of events and the response of the communities.

Donate to Intercontinental Cry to support indigenous media like this film.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 10, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest

By Carlos Enrique Maibeth-Mortimer / Intercontinental Cry

There is a crisis erupting in Nicaragua’s North Caribbean Autonomous Region that spans across all social and economic boundaries, affecting everything from human rights to ecosystem preservation to climate change. The Indigenous Miskitu and Mayagna Peoples, whose traditional cultural practices are inseparably linked to the environment and who exist at the forefront of imminent climate shifts capable of displacing entire communities, are under attack. The situation is one that world doesn’t yet know about. It is incumbent upon all of us to change that–to do what we can to empower the Native Peoples of Nicaragua, and stop the destruction.

Settlers are attacking Indigenous communities with automatic firearms, killing, plundering and forcing residents to flee their ancestral lands. Foreign companies have entered the territory illegally and are burning the region’s precious stronghold of biodiversity and natural resources at an alarmingly rapid rate.

Disturbing reports continually come to light of dozens of killings and kidnappings, particularly of Miskitu Indigenous men and women. Thousands of Indigenous refugees have been forced to flee their communities to the relative safety of more urban areas. With no support services intact to deal with the influx of refugees in the already strained resources of the urban regions, those fleeing the violence continue to suffer a lack of food and lack of medical attention upon arrival. The murderous ‘colonos’ operate with complete impunity. As a result, the attacks continue unrestrained by Nicaraguan law enforcement, contributing to a climate of escalation. There is a real and valid concern regarding the virtual media blackout, in both local and international spheres, where little to no reporting focuses on the critical situation unfolding.

Inhabitants of the Atlantic Coast, or Costeños as they are collectively known to the rest of Nicaragua, represent a unique diversity of ethnic groups including Indigenous Miskitu, Mayagna, and Rama, Garífuna (descended from African slaves and Carib Indians), English-speaking Creoles (descendants of African slaves), and Mestizos (mixed race Latin Americans descended from European colonizers and Native peoples).

The region was deeply impacted – scarred even – by the revolutionary war of the 1980’s, when US-backed counter-revolutionaries mounted attacks against the Sandinistas from military bases in Honduras, just across the Coco (Wangki) River.

In 1987, with the war raging, the Autonomy Statute for the Atlantic Coast was enacted and amended to the Nicaraguan Constitution. The new law recognized the multi-ethnic nature of the communities of the Atlantic coast; and in particular, noted Indigenous peoples’ rights to identity, culture and language. The new Autonomous Regions were divided between the North and the South.

In 2003 the Nicaraguan National Assembly finally passed the Communal Property Regime Law 445 and the Demarcation Law to address Indigenous concerns regarding land demarcation and natural resources after much pressure from international institutions.

Indigenous people have legal ownership to significant portions of their ancestral lands as assured by Nicaraguan law, in addition to the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention 169 ratified by Nicaragua in 2010 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Yet realities have differed from legalities. Although the Autonomy Agreement recognized collective land holdings, Indigenous people did not actually hold the legal title to their lands for a long time. In recent years, while Indigenous people have been waiting for formal title to be issued to their lands, false titles have been issued in Managua or elsewhere, selling land illegally to settlers from outside the region. It is a sad reality that although Law 445 calls for the removal of illegal settlers from Indigenous lands, it is increasingly undeniable that the exact opposite has taken place.

Violent conflicts over Indigenous land rights have been increasingly erupting in the remote areas of the Northern Caribbean Autonomous Region. Since September 2015, the Miskitu settlements of Wangki, Twi-Tasba Raya, and Li Aubra, have come under especially heavy attack. Reports indicate as many as 80 Miskitu men have been killed or kidnapped from these regions alone; while as many as 2,000 refugees fled their homes and communities in fear for their very lives. These particular villages have been hit especially hard by the violent conflict and, despite pleas for help at municipal and national levels, have received no measure of protection or even investigation, much less prosecution.

Transnational lumber companies siphoning profits from the region’s natural resources have been operating out of nearby Honduras. They are carrying out sophisticated lumbering operations utilizing helicopters and cargo boats to facilitate the rapid export of extracted wood. Nicaragua is home to the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve, one of the largest tropical rainforests in the Americas, second only to the Amazon. The world can no longer stand by while this stronghold of biodiversity and climate-stabilizing carbon-mitigating forest is sacrificed to next quarter’s profits.

Pleas for help have seemed to fall on deaf ears in the capital city of Managua. The Nicaraguan government has not officially acknowledged any of the most recent and most egregious killings, illegal land occupation or deforestation issues. The socialist central government has not offered any plan for addressing this escalating humanitarian crisis, for providing any gestures of protection to the Indigenous communities under attack nor assistance to the refugees. Many Indigenous to the region cannot help but suspect that human rights violations and land rights violations may be happening with the silent consent of the central Nicaraguan government.

While much attention has been given to the Nicaraguan government’s sale of a concession to a Chinese investment firm for an ill-conceived canal to run through the Southern Caribbean Autonomous Region, virtually no media attention has focused on the current urgent crisis in the Northern Region.

Thousands of illegal settlers have clear cut precious rainforest – indifferent to immediate or long term impacts – and have begun to establish cattle ranches and lumber operations that are completely inappropriate to the ecology of the region. The environmental impact mirrors the destructive patterns playing out in the Amazon Basin.

The Bosawas Biosphere Reserve is located in the North Caribbean Autonomous Region in an area historically occupied by Indigenous Mayagna and Miskitu people. The reserve has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site due to its unique ecological and biocultural significance. The negative impacts on this vulnerable area in particular have consequences not only for Nicaragua, but also for the whole planet. Tropical rainforests hold 50 percent more carbon than trees elsewhere. To this end, deforestation of tropical forests actually causes much more carbon to be released. The problems associated with illegal human migration to the region and its effect on the natural ecology and rates of deforestation are grave, with worldwide ecological consequences.

Although there are differences among settler groups, what they have in common is an environmentally destructive cultural mentality. It is not a coincidence that the settler groups who have inflicted the worst environmental destruction have simultaneously inflicted the worst violence against Indigenous Miskitu and Mayagna.

The critical cultural differences between the Native populations and the non-Indigenous settlers can result in vastly different outcomes for the natural environment. These key cultural differences include: property regimes, expansion patterns, agricultural practices and long-term economic strategies. Indigenous communities hold land in common, meaning that they have collective ownership of their territories. Mestizo settlers, on the other hand, exercise a private property model and parcel out land that they have settled and/or seized.

Significant differences in the use and care of livestock can have a major environmental impacts. On average, only 10 percent of Indigenous families have cattle, whereas mestizo settlers average one cow per family. The low cattle count among Indigenous families, along with their nucleated communities, means that cattle are kept within the limits of the village, along with other livestock like pigs. The Indigenous people of the region contain their animals within the perimeter of their communities, whereas crops are planted in wooded areas up to a two-hour radius from community centers.

When mestizo settlers move into the region they re-shape and redistribute the land with the driving purpose of raising cattle and in anticipation of obtaining even more cattle in the future. After clear-cutting invaluable rainforest land, they immediately begin sowing grass seed and other crops. Within one season, their crop fields are converted into more pasture land. Indigenous farmers, on the other hand, will cut back specific plots of rainforest but will only use these plots for a year or two. They then allow them to grow back and move on to another area to develop communal plots. This traditional Indigenous practice of land management allows the rain forest to regenerate and recover — a sustainable method the Indigenous biostewards of the region have practiced for thousands of years.

On the other hand, mestizo settlers often cause irreversible damage to the rainforest. Settler occupations seem bent on developing as much pasture as possible. If they have the economic means, they raise more cattle and continually increase the herd size. If they do not have the means for raising cattle, they sell this land to settlers who do have cattle. This is the way in which mestizo settlers illegally appropriate traditional Indigenous territory and cash in on the destructive practices they inflict on it soon after. This type of land speculation and ‘economic development’ is almost nonexistent among Indigenous groups, and many view it as a direct challenge to their inherent values. Ironically, many mestizos use this conservative approach to concoct a false narrative that Indigenous people are lazy and undeserving of their vast quantities of land.

Even with growing populations, indigenous communities have a relatively low environmental impact compared to their mestizo non-Indigenous counterparts. The differences in environmental impact and lifestyles between Indigenous and mestizo communities put land tenure and environmental conservation in perspective.

Significant progress towards honoring Indigenous land rights must be a crucial component in the creation of a multi-stakeholder enforced strategy to protect the environmental integrity of the Autonomous Region of Northern Caribbean. It becomes especially critical when considering the overarching role tropical rainforests play in regulating the Earth’s climate.

The two factors of tropical deforestation and human-induced global warming are inextricably connected. There is a definite consensus in the scientific community that deforestation is one of the innate causes behind global warming. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, “… Between 25 to 30 percent of the greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere each year —1.6 billion tons — are caused by deforestation.” Contributing to deforestation is by definition contributing to global warming.

It’s important to really drive home the compounding effects of the destruction of tropical rainforest: is it is even more damaging to the environment than destruction of other types of forest because of the unique ecology of rainforests. Compared to boreal forests, which are much more expansive, each square hectare of tropical rainforest holds nearly 50 percent more carbon.

The carbon within tropical rainforests is split pretty evenly between soils and flora. When tropical rainforests are clear-cut,massive amounts of carbon are released. Warmer temperatures cause soil to more rapidly decompose.

Tropical forests sequester more carbon because they grow year round and faster than other forest types. When protected and preserved, tropical rainforests are able to actually take in more carbon than they release into the atmosphere, critically reducing the adverse effects of fossil fuel emissions. To put things in clear perspective, tropical rainforests produce 20 percent of the world’s oxygen and 30 percent of the world’s freshwater.

When tropical forestland is transformed into pasture and overused, it leads to a steady cycle of desertification. Rainforests hold together the soil and ensure that it is saturated with rich nutrients. Over time, cattle grazing on pasture land created by clear-cutting forest will quantifiably weaken the soil. Monsoon seasons that are prevalent in Eastern Nicaragua steadily wash away any topsoil that no longer has forests holding it together or nourishing it. Without trees this lower-level soil cannot adequately absorb water. This further leaves areas more susceptible to flooding and landslides. Manure, fertilizer and pesticide runoff are contaminating and acidifying nearby waterways, killing off flora and fauna that are critical to the integrity of intact forests. During the summer months, this lower-level soil bakes and cracks, slowly developing into desert.

Lest it seem the many and crucial challenges facing the Indigenous people of Nicaragua are insurmountable in the face of such great adversity, Native Miskitu and Mayagna continue to defy the odds and act as trailblazers. Their actions set a prime example of what can be accomplished, even with minimal resources.

Although many of the Native people of Nicaragua are not familiar with the Pan-Indigenous American movement known as Idle No More, their actions are living embodiments of the mantra. They have consistently and repeatedly sought assistance and protection from local and national authorities, yet their pleas for help have fallen on deaf ears. No meaningful action has been taken by any government authority. The problem of Indigenous land rights violations and removal of the settlers has been presented to the OAS (Organization of American States) and the IACHR (Inter-American Court of Human Rights). The issue has even been formally raised at the United Nations Permanent Forums on Indigenous peoples.

NGOs played a supportive role in pressuring the Nicaraguan government to institute necessary jurisprudence in protecting environment and Indigenous land rights; the problem is that the laws are not being respected or enforced. The government continues to ignore the laws both at the national and local level. Mounting anecdotal evidence points to the possibility of corrupt officials contributing to the problem, at virtually every level of government. Through their inexcusable silence and inaction in the face of the escalating crisis, government at all levels is complicit at least in actively undermining Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their legal territories.

This is an ongoing crisis in the Autonomous Region of Northern Caribbean Nicaragua. The Indigenous cultures of the region are inseparably linked to the natural environment. The legal protections for Native people and the rain forest are being flagrantly violated by increasingly violent mestizo colonists (‘colonos’). Government at all levels has proven ineffectual in the face of the crisis. There has been no media coverage of this crisis, the escalation of violence, or the plight of refugees fleeing the areas of conflict.

It’s also important for us to help stop the destruction of the tropical rainforest, which is critically important to all of us. Government inaction in the face of mounting numbers of refugees and killings is morally corrupt and warrants international outcry.

The Indigenous Miskitu and Mayagna are not passive victims, but they are facing a tremendous challenge to address a problem of this magnitude. They are in desperate need of assistance to overcome this crisis.

5 WAYS YOU CAN HELP

- It is very important for international media outlets to focus on what is happening in this remote region. Spreading the word through social media will be key to applying international pressure to help the refugees and stop the killing of both the Indigenous people and the rainforest.

- There is an equal need for conventional media coverage. To that end, you can reach out to your favorite news outlet and encourage them to take on the story

- Costa Rica, Mexico, and the U.S. government have issued travel bans to Nicaragua, nevertheless, there is a growing need for humanitarian aid and witnesses to document what’s happening on the ground.

- If you want to support the Miskitu and Mayagna from home, consider organizing a community event or any kind of online action to make sure the world knows what’s happening.

- You can also ask the Ortega government to do the right thing, by working with the Miskitu and Mayagna to secure their ancestral territory, addressing the ongoing land theft and responding to the brutal attacks that are being carried out at the hands of the Colonos.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 18, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

By Laura Hobson Herlihy / Cultural Survival

The Miskitu people (pop. 185,000) live in Muskitia, a rainforest region that stretches along the Central American Caribbean coast from Black River, Honduras to just south of Bluefields, Nicaragua. Two-thirds of Muskitia and the Miskitu people reside in Nicaragua. The Miskitu people in Nicaragua today are in a crisis situation. Armed mestizo colonists are attacking their communities, pillaging and confiscating their rainforest lands. This article is a cry for help.

The Miskitu people have legal ownership of their lands guaranteed by Nicaraguan Law 445, the ILO Convention 169, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Yet, mestizo colonists (called, colonos) from the interior and Pacific coast have invaded, and now illegally occupy, nearly half of their lands. In September 2015, violence over land conflicts erupted in the Miskitu territories of Wangki Twi-Tasba Raya and Li Aubra. These territories are located near the Coco or Wangki River, the international border between Nicaragua and Honduras.

Since September, mestizo colonists with automatic weapons have killed, injured, and kidnapped more than 80 Miskitu men with impunity. In fear for their lives, between 1-2,000 Miskitu refugees have fled to Waspam and Puerto Cabezas-Bilwi and Honduran border communities. The refugees–mainly women, children, and elders–are suffering from starvation and lack medical supplies. Children have not attended school for six months. Meanwhile, periodic attacks continue on Miskitu communities in Wangki Twi-Tasba Raya.

Much of the violence now occurring revolves around article 59 of the Communal Property Law (law 445). Article 59 requires the Nicaraguan state to complete saneamiento, the cleansing or the removal of colonists and industries from Indigenous and Afro-descendant territories. The current Nicaraguan government publically agreed to saneamiento but has not responded. Similarly, the government still has not provided protection to the Miskitu communities under attack or assistance to the refugees. As a result of the government’s delayed reaction to the crisis, the Miskitu people now suspect the Sandinista (FSLN) state to be complicit with the colonists’ invasion of their Indigenous territories.

In a separate but related issue, the FSLN government passed the Canal Law (Act 840) that approved the Chinese-backed (HKND) inter-oceanic canal to cut through the ancestral homeland of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples along the Nicaraguan Caribbean coast. Tensions are rising over Indigenous territoriality and land rights, especially between the Miskitu people and President Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista government. The tense situation over land rights today bares eerie similarities to the war-torn years of the 1980s in Nicaragua, when Ortega first served as President (1985-1990) and the Miskitu fought as counter-revolutionary warriors in the Contra war within the Sandinista revolution (1979-1990).

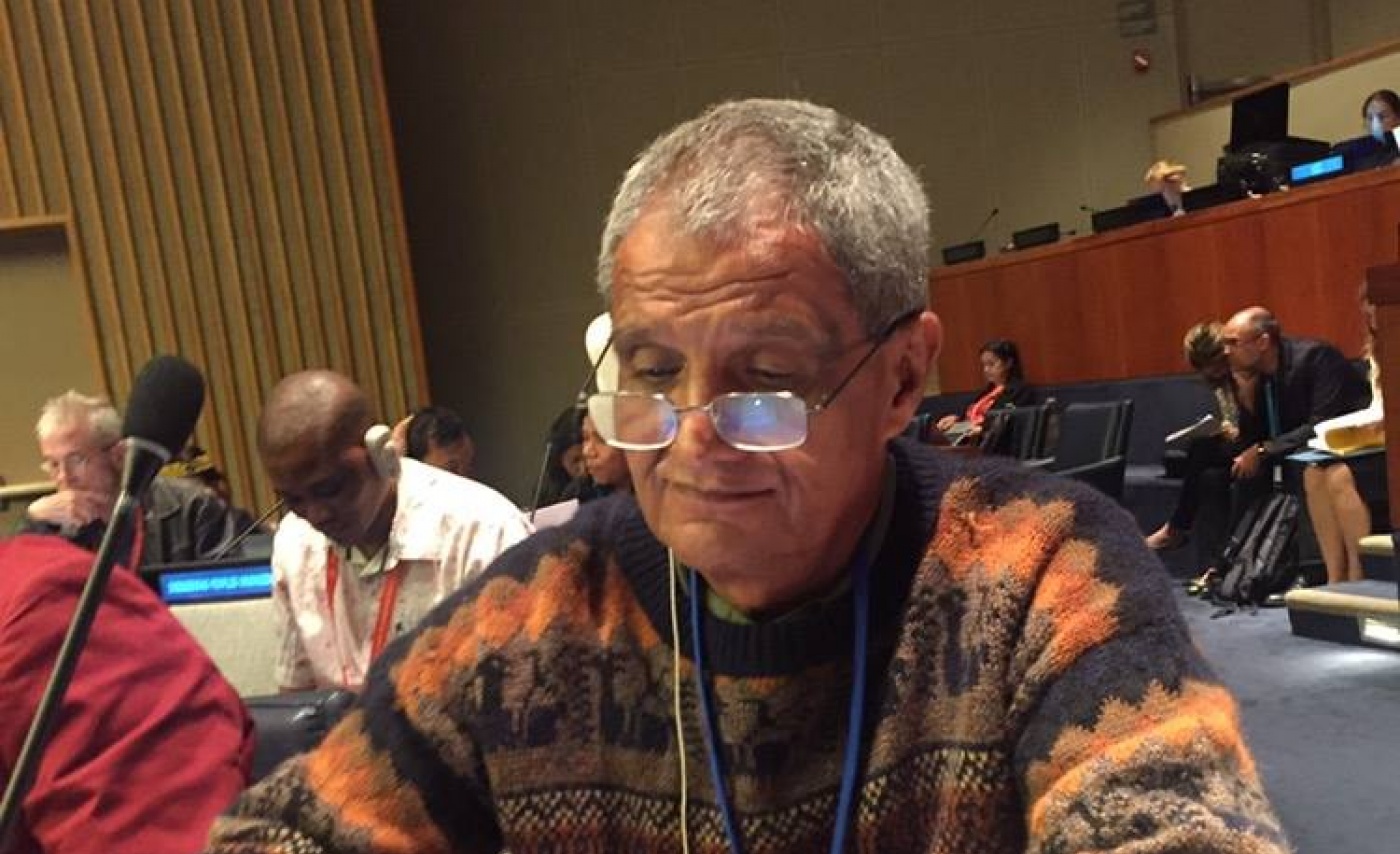

As a US anthropologist who has worked for over twenty years with the Honduran and Nicaraguan Miskitu people, I had the opportunity to attend the 2016 United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (May 9-20). On Thursday, May 12, I recorded Miskitu leader Brooklyn Rivera’s intervention in the session, “Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples.” Rivera has served as the Líder Máximo (literally, Highest Leader) of the Nicaraguan Miskitu people for over 30 years; after rising to power as a military leader in the revolution and war, Rivera in 1987 founded and became the long-term director of the Indigenous organization Yatama (Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka/Sons of Mother Earth). Special thanks to Costa Rican anthropologist Fernando Montero (ABD, Columbia) for transcribing Rivera’s United Nations intervention in Spanish and translating it to the English below.

English Version

My name is Brooklyn Rivera. I am both a son and the highest leader of the Miskitu people of the Nicaraguan Muskitia. As we know, the rights of Indigenous peoples are essentially human rights. According to Article 1 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous people have the right, both as peoples and as individuals, to the full enjoyment of their human rights and fundamental liberties. In my country of Nicaragua, the rights of Indigenous people have suffered severe setbacks in the last several years. Indeed, the current Sandinista government–contrary to its rhetoric in international forums and in flagrant violation of the rights of Indigenous peoples–freely acts against Indigenous peoples, advancing a consistent policy of aggression and internal colonialism.

Consider the following within the specific sphere of Indigenous peoples’ rights: the government imposes violence against our communities by means of settlers who invade ancestral territories, carrying out armed attacks, murders, kidnappings, rape, and displacement, producing refugees, most of whom are women, children, and people of old age. All this occurs in the face of governmental and institutional passivity, even complicity. Moreover, the Nicaraguan government is currently implementing a policy of militarization in our communities and fishing territories, committing murders such as that of our brother and leader Mario Lehman last September. In like manner, the government is overtly trampling on our communities’ right to ancestral autonomy by interfering with the election of their leaders according to their own practices and customs, devoting itself to destroying the structure and traditional procedures of our communities with the aim of replacing them with the so-called Sandinista Leadership Committees, part of their party structure. In this way they create and impose a spurious and noxious structure parallel to Indigenous authorities. You will understand that, by applying this policy, the government and the ruling party are fomenting division within families and communities, destroying their social fabric, cultural values and [imposing] heightened suffering and poverty. In addition, in open violation of the right to work, the Sandinista government denies jobs and government positions to Indigenous professionals and technicians, demanding that they become members of their party before considering them for these positions.

With regard to the sphere of the environment of our peoples in Nicaragua, I must first point out the dispossession of lands and territories suffered by Miskitu communities perpetrated by cattle ranchers, mining companies, and wealthy sectors linked to the government and the ruling party, who use settlers as spearheads. In this invasion, armed settlers arrive in our lands, advance the agricultural frontier, occupy extensions of territory, and destroy the habitats and ecosystems of Indigenous peoples, preying on their fauna, flora, and marine ecology. Needless to say, this extractivist policy involves the looting of ancestral communal resources such as forests, flora, mineral resources, water resources, and land itself with the illegal land sales in which settlers participate. I must also mention the promotion of megaprojects such as the interoceanic canal and the Tumarin hydroelectric dam in Awaltara, both of which violate Indigenous peoples’ right to prior, free, and informed consent. These megaprojects render entire communities vulnerable to disappearing along with their culture and language. This is the case of the Rama people, a small, vulnerable people in danger of extinction who reside in the Southern Moskitia. In the face of this crude reality and despite its demonstrated lack of political will and its disrespect for international laws and institutions—not to mention my own arbitrary, illegal expulsion from the National Parliament—once again we demand from the Nicaraguan government:

1. The immediate application of the recommendations issued last December by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in reference to the cleansing [“saneamiento”] of Indigenous territories and the protection of our communities in the face of settler invasion;

2. The immediate enactment of the precautionary measures suggested by the OAS’ Human Rights Commission on behalf of the Indigenous communities in the regions of Tasba Raya and Wangki Li Auhbra (location in the municipality of Waspam), approved in October 2015 and expanded in January 2016;

3. The immediate launch of a process of genuine dialogue and negotiation with Indigenous peoples via their organizations and leaders to reach real solutions based on respect for Indigenous peoples and the recognition of their dignity, as outlined in existing frameworks;

4. Finally, the immediate restitution of the undersigned as legislator, in accordance with his status as a popularly elected official put in power thanks to the votes of Indigenous peoples, whose constitutional and legal rights were violated with my arbitrary and illegal expulsion from Parliament.

I end my intervention by asking all participants, especially the Indigenous peoples in this forum, to engage in active solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Nicaragua and their organizations as they resist and demand dignity, rights, and justice from the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

Thank you, Mr. President.

En Espanol

Soy Brooklyn Rivera, hijo del pueblo mískitu de la Mosquitia nicaragüense y su dirigente principal. Como sabemos, los derechos de los pueblos indígenas son esencialmente derechos humanos. Como se establece en el artículo 1 de la Declaración de la ONU sobre los Pueblos Indígenas, los indígenas tienen derecho como pueblos o como individuos al disfrute pleno de todos sus derechos humanos y las libertades fundamentales. El país de donde vengo yo, Nicaragua, en los últimos años ha experimentado un grave retroceso en el ejercicio de los derechos de nuestros pueblos indígenas, recogido en el marco legal interno y externo del país. En efecto, el actual gobierno sandinista, contrario a su retórica en los foros internacionales y en abierta violación de los derechos de los pueblos indígenas reconocidos en la Constitución Política y en las demás leyes y los instrumentos internacionales suscritos, se dedica a actuar libremente en su contra impulsando toda una política de agresión y colonialismo interno.

Veamos: en el ámbito específico de los derechos humanos de nuestros pueblos indígenas, a través de los colonos invasores de los territorios ancestrales, impone una situación de violencia en contra de nuestras comunidades mediante ataques armados, cometiendo asesinatos, secuestros, violaciones y desplazamentos, produciendo refugiados, mayormente niños, mujeres y ancianos. Todo esto ocurre ante la pasividad y aun la complicidad del gobierno y sus instituciones. Más aún, el gobierno nicaragüense implementa una política de militarización de las comunidades y las áreas de pesca, en las que cometen asesinatos como en el caso del crimen del hermano dirigente Mario Lehman ocurrido en el mes de septiembre pasado. De la misma forma, el gobierno aplica un abierto atropello al derecho de autonomía ancestral de nuestras comunidades en la elección de sus autoridades basada en los usos y costumbres, cuando a través de sus turbas partidarias y con el acompañamiento de sus policías y hasta de militares, aún así sin el mínimo respeto a las leyes y formas organizativas propias, se empecina en destruir la estructura y los procedimientos tradicionales de nuestras comunidades con el fin de sustituirlos con los llamados Comités de Liderazgo Sandinista, una estructura de su partido en el poder, creando e imponiendo así una estructura espuria y nociva, paralela a las autoridades indígenas. Como comprenderán, aplicando esta política el gobierno y su partido crean división entre las familias y comunidades, destruyendo sus tejidos sociales, valores culturales y mayor sufrimiento y pobreza. Además, el gobierno sandinista en abierta discriminación al derecho al trabajo, niega a los profesionales y técnicos de los pueblos indígenas el derecho al trabajo cuando exige que debe convertir a ser miembro de su partido para ocupar cargos o empleo en el país.

En relación al ámbito del medio ambiente de nuestros pueblos en Nicaragua, debo iniciar señalando el despojo de las tierras y territorios que sufren las comunidades en la Mosquitia de parte de los terratenientes ganaderos, empresas mineras y grupos adinerados vinculados al gobierno y a su partido, utilizando a los colonos como punta de lanza. En la invasión, los colonos armados llegan a nuestras tierras, aplican un avance agropecuario, ocupan extensiones de territorio y destruyen los hábitats y los ecosistemas de los pueblos indígenas, cometiendo depredaciones ambientales en su fauna, flora y entorno marino. Lógicamente, con esta política extractivista pasa por el saqueo de los bienes comunales ancestrales tales como los bosques, la flora, los recursos mineros, los recursos hídricos y la misma tierra con el tráfico ilegal de parte de los colonos. También aquí debo mencionar el impulso de los megaproyectos tales como el canal interocéanico y el hidroeléctrico Tumarín en Awaltara, en ambos casos violentando el derecho al consentimiento previo, libre e informado de los pueblos, impulsan sus megaproyectos en los que exponen la desaparición de comunidades enteras junto con su cultura y su idioma. Tal es el caso del pueblo Rama, pueblo pequeño, vulnerable y en proceso de extinción, ubicado en la Mosquitia Sur. Ante esta cruda realidad y a pesar de su falta de voluntad política demostrada y de su irrespeto a las leyes y las instituciones internacionales, así como de mi expulsión arbitrario e ilegal del Parlamento Nacional, como un esfuerzo de solución al conflicto impuesto, una vez más exigimos al gobierno nicaragüense:

- La inmediata aplicación de las recomendaciones de la Relatora Especial de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, emitidas en el mes de diciembre pasado, referentes al cumplimiento de la etapa de saneamiento de los territorios y de la protección de nuestras comunidades ante la invasión de los colonos;

- El inmediato cumplimiento de las medidas cautelares presentadas de parte de la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de la OEA a favor de las comunidades indígenas de la zona de Tasba Raya y de Wangki Li Auhbra en el municipio de Waspam, y abrobadas en el mes de octubre 2015 y ampliadas en enero de 2016;

- La inmediata apertura de un proceso genuino de diálogo y negociaciones con los pueblos indígenas a través de sus organizaciones y líderes que conduzcan a unas soluciones reales basadas en el respeto y el reconocimiento de la dignidad y los derechos de nuestros pueblos reconocidos en las normativas;

- Finalmente, la restitución inmediata del suscrito como legislador electo popularmente con los votos de sus pueblos indígenas, violentando mis derechos constitucionales y legales con el despojo arbitrario e ilegal cometido durante mi expulsión del Parlamento.

Termino mi intervención requiriendo a todas y todos los participantes, mayormente a los pueblos indígenas de este foro, una solidaridad activa con los pueblos indígenas y sus organizaciones en Nicaragua en el marco de su resistencia y demanda de dignidad, derecho y justicia ante el gobierno sandinista en Nicaragua.

Gracias, Presidente.