by DGR News Service | Aug 14, 2023 | ACTION, Listening to the Land

Editor’s Note: In the Fight for Who We Love series, we introduce you to a species. These nonhuman species are what inspires most of us to join environmental movements and to continue to fight for the natural world. We hope you find this series inspiring, informative, and a break from news on industrial civilization. Let us know what you think in the comments! Also, if there is a species that you want us to cover in the upcoming months, please make suggestions. Today they are polar bears.

By Kim Olson and Benja Weller

When there’s talk about climate change affecting other species, people often think of polar bears. Because yes, their habitat is being destroyed — and we’ll get to that.

But the reason we’re writing about polar bears today is because long before I (Kim) knew anything about climate change or melting ice caps, they were my favorite wild animal. Because to me, they represent patience and intelligence, strength and resilience, playfulness and beauty.

FOOD + BEHAVIOR

A polar bear stretches in Kaktovik, Alaska. Photo: Kim Olson

Like much of the wild world (what’s left), polar bears must put in some serious effort and time to acquire their next meal, and as the largest terrestrial carnivorous mammal on earth, that’s no small amount.

So how much food do they need, then?

“Polar bears need to consume approximately 4.4lbs [2kg] of fat daily or a 121lbs [55kg] seal provides about 8 days’ worth of energy. Polar bears can eat 100lbs [45kg] of seal blubber in one sitting.”

–Nature Magazine

A typical polar bear meal doesn’t vary a whole lot and includes one main course: seals (ringed, but also bearded, hooded and harped). But when food is scarce, they’re opportunistic eaters and will munch on berries, fish, plants, birds, small mammals — basically whatever they can find, which unfortunately also includes human garbage.

Hunting patiently on an ice sheet

While polar bears use their semi-webbed, big-ass paws (about 12in / 30cm, which is bigger than most human heads!) to wander the snowy ground and doggy paddle around the Arctic Ocean like nobody’s business, they aren’t aquatic animals. So they have to hunt usually at the edge of sea ice or next to a seal’s breathing hole.

Once the bears locate a suitable place to hunt, they get comfortable and prepare themselves for a potentially long wait. This most common “still-hunting” method, which they’re the most successful at, requires that the bears barely move for hours and sometimes even days.

Days! I don’t know about you, but I find that kind of commitment and patience remarkable. Because in an age where instant gratification is a thing, us civilized humans may sometimes feel it’s unbearable to have to wait longer than even thirty minutes for a meal when we’re hungry. But polar bears? They’ve got the patience thing down. I mean, they have to. Because, contrary to popular belief, food doesn’t actually come from the grocery store.

When not about to pounce on a seal, polar bears are generally slow-moving creatures, ambling leisurely and deliberately to conserve their strength. At times they may wander for miles, their huge paws helping to keep them from sinking too deeply into the snow.

A bear walks across the snowy ground in Kaktovik, Alaska. Photo: Kim Olson

EVOLUTION + HABITAT

Harsh climate made polar bears become specialists

Polar bears diverged from brown bears but it’s not clear when — some estimates say a few hundred thousand years while newer guesses put it at a few million years.

But no matter when the split occurred, polar bears developed some unique characteristics that help them survive in a harsh climate where average winter temperatures are around -29°F / -2°C.

Most bears live north of the Arctic Circle in the US, Canada, Greenland, Norway, and Russia, and spend much of their lives on sea ice hunting (some sources say up to 50% of their time).

3 fun facts you may not know about polar bears:

- Their skin is black, which helps them absorb heat from the sun (when they have it, which is not much in the winter that far north!).

- Their fur (the thickest of all bears) is not white and is not actually hair. The outer layer of fur is in fact clear, hollow tubes. But because of the way these tubes reflect the visible light wavelengths, the fur appears white. And the hollow tubes provide insulation against the frigid temps and repel water.

- They don’t (typically) hibernate. Since their main food source (seals) is available only during the winter, only pregnant females hibernate (and in case you’re wondering, twins cubs are the most common), and even then it’s not a full hibernation like other bears do.

A mama bear with her two cubs in Kaktovik, Alaska. Photo: Kim Olson

QUICK STATS

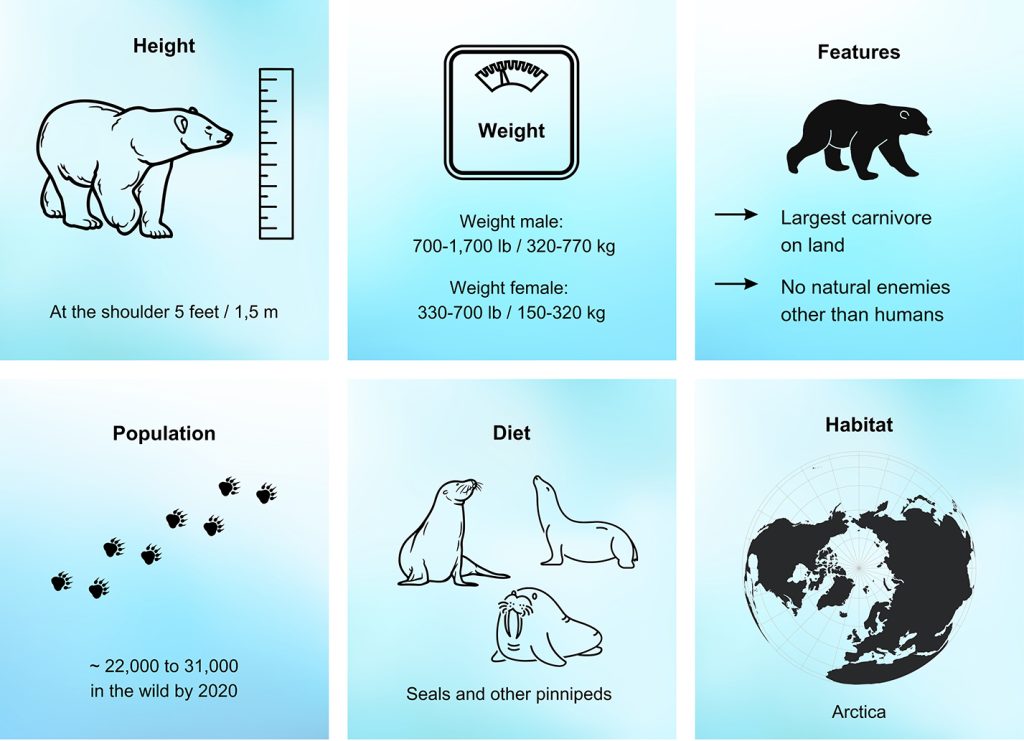

Size: Males are about 2-3 times larger than females.

Length: 6-8′ [1.8-2.4m] females, 8-10′ [2.4-3m] males, 12″ [.3m] newborn

Height: up to 5′ [1.5m] at shoulder on all four paws, 7-11′ [3.3m] standing upright

Weight: 300-700lb [136-318kg] females, 700-1700lb [318-771kg] male, 1-1.5lb [.5-.7kg] newborn

Paws: webbed paws up to ~12” [30cm] across, which makes them good paddles

Lifespan: 20-30 years in the wild

Running Speed: 25mph [40kph]

Swimming Speed: 6mph [10kph] for up to 62mi [100km] continuously

Walking Speed: 3.4mph [5.5kph]

A solo polar bear walking in Kaktovik, Alaska. Photo: Kim Olson

THE BIGGEST THREAT

Melting ice sheets due to global warming

Most of us have seen pictures or videos of starving polar bears in the news. Skinny polar bears searching for food or sitting on an ice sheet with nothing around them but water are heart-wrenching to watch.

Photos and videos like those show the devastating effects of global warming, and are warning signs that express the conclusion in a BBC article by Helen Briggs and Victoria Grill: “Polar bears will be wiped out by the end of the century unless more is done to tackle climate change, a study (by Nature Climate Change) predicts.“

The single most important threat to the long-term survival of polar bears is loss of sea ice due to global warming, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. National Geographic writes about the bears in the Beaufort Sea region, who are among the best studied: “Their numbers have fallen 40 percent in the last ten years.”

Polar bear babies need fat

In our times of warmer climate, sea ice melts earlier in the spring and forms later in the autumn, forcing polar bears to walk or swim longer distances to the remaining ice sheets.

The second effect of melting sea ice is that the bears stay on land longer fasting and living off their fat stores. In both cases, the extra energy loss affects their ability to effectively reproduce and raise babies. When the mother is too skinny, a couple of problems arise:

Initially she can’t have as many babies as a healthy mom can. But when she does have cubs, they have a greater risk of dying by starvation due to the lack of fat in the mother’s milk. This can only mean that the entire population of polar bears decline.

Fossil fuel extraction in the Arctic

Pollution and the exploration of new oil and gas resources are also major threats to these white predators. As we’ve outlined in the article about Adélie penguins, there’s persistent organic pollutants (POPs) being moved from warmer areas to the cold Antarctic and Arctic.

If bears eat seals, they also consume POPs, and high levels of POPs rob polar bears of their vitamin A, thyroid hormones, and some antibodies which impairs their growth, reproduction, and the strength to fight off diseases.

Oil is toxic for animals in the Arctic

As easy-to-access oil and gas resources become scarcer, the industries explore in the most remote places to find this so-called “black gold.” Unhinged, they try to exploit the beautiful Arctic, even though offshore oil operations pose a great risk to the polar bears.

When oil spills into the sea, it affects the bear’s fur, reducing its insulating effect. The bears unknowingly ingest the oil which can cause long-term liver and kidney damage, even if it’s a small amount. Oil spills can wipe out entire populations when they happen in places where there’s a high density of polar bear dens.

Despite sitting around most of the time, National Geographic says that these high-energy beasts can burn through 12,325 calories a day, which is equivalent to 40 (!) burgers.

The polar bears can’t just adapt to melting ice sheets and change their hunting methods in an instant — evolution doesn’t work like that.

Two polar bears play fight in Kaktovik, Alaska. Photo: Kim Olson

WHY THEY’RE SPECIAL

If you ask us, a world without the magnificent polar bears is a world worse off. So they are one more reason #whywefight.

FURTHER READING + SOURCES

Featured Image: A female polar bear with her two cubs in Kaktovik, Alaska. Photo: Kim Olson

The 2023 DGR conference is scheduled for late August in northern California. This annual gathering is an opportunity for our community to share skills, reflect on our work, strengthen our connections, and plan for the future. While this conference is only open to DGR members, we do invite friends and allies on a case-by-case basis. If you’re interested in attending, please contact us, and if you’d like to donate to support the conference, click here.

by DGR News Service | Dec 5, 2022 | ACTION, Culture of Resistance

Editor’s note: The Rojava conflict, also known as the Rojava Revolution, is a political upheaval and military conflict taking place in northern Syria and Iraq known among Kurds as Western Kurdistan or Rojava.

In this social revolution a prominent role is played by women both on the battlefield and within the newly formed political system, as well as the implementation of democratic confederalism, a form of libertarian socialism that emphasizes decentralization, gender equality and the need for local governance through direct democracy.

As an eco-feminist organization, DGR agrees with Women Defend Rojava that all women should aspire to the principles of self-defense. That this consciousness must be established in society as a culture of resistance. The power of the State will always attack those who resist and rise up against patriarchal violence and fight for a free life. As part of the women’s revolution, the Rojava takes an important role in building alternatives to the current patriarchal-capitalist world system and defending them.

“A society can not be free with out women’s liberation” (Abdullah Öcalan)

This is an open letter from Women Defend Rojava and other signatories requesting an investigation into Turkey’s alleged use of chemical weapons in Kurdish people based in Syria and Iraq.

Open letter from Women Defend Rojava

On the occasion of November 30, the Day of Remembrance of all Victims of Chemical Warfare, we write with deep concern about disturbing allegations of the use of prohibited weapons by the Turkish military in its ongoing military operations against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Moreover, we are writing at a time in which the Turkish state is once again targeting civilians inside Syria and mobilizing for another possible ground invasion.

On October 18, local media released video footage showing the impacts of alleged chemical weapons exposure on two PKK guerrillas. Both were among 17 of the group’s fighters who lost their lives as a result of alleged chemical attacks in recent months.

The footage followed a report published by the NGO International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) last month that examined other allegations of Turkish chemical weapons use and called for an international investigation based on its findings.

In 2021, human rights monitors and local media reported at least once instance of civilian harm potentially caused by alleged Turkish chemical weapons use. The authors of the IPPNW report attempted to meet with the impacted civilians, but were blocked from doing so by the Kurdistan Regional Government.

We understand that the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) can only investigate allegations of chemical weapons use when a request is made by a state party.

However, it is our view that these existing mechanisms do not reflect the realities of warfare today. Peoples without states and non-state political and military actors are deeply involved in modern conflicts. So are autocratic regimes that stifle the voices of those who wish to hold their governments to account for their behavior in war.

Both of these conditions are relevant here. The Kurdish people do not have a government that can speak up for them. They live under repressive regimes with powerful allies in the West—Turkey, for example, is supported by its NATO allies despite consistent evidence of serious human rights abuses.

This means that, while Kurds are disproportionately more likely to be subjected to war crimes and violations of international law as a result of their status as an oppressed minority, they are also disproportionately less likely to have access to justice mechanisms to hold perpetrators accountable.

In order to be effective, human rights law and the laws of war must be implemented as universally as possible, free from political considerations. There should be as many avenues as possible for credible allegations of human rights violations and violations of the laws of war to be investigated by impartial international bodies—particularly serious violations like the use of prohibited weapons.

Furthermore, these investigations should not simply be aimed at the historical record. They should build towards justice and accountability for all who violate international law, as well as durable political solutions to ongoing conflicts.

To that end, we the undersigned make the following recommendations:

To the OPCW:

- Amend investigation procedures to allow greater access to justice and accountability for alleged chemical weapons use.

- Investigate allegations that Turkey may have used chemical weapons in Iraqi Kurdistan.

To the government of Turkey:

- End all cross-border military activity in Iraq and Syria immediately.

- Cooperate fully with local and international investigations of alleged chemical weapons use and other alleged war crimes and human rights abuses and hold perpetrators accountable if violations are found.

- Return to peace negotiations with the PKK to resolve the Kurdish issue by political means.

To the Kurdistan Regional Government:

- Allow international investigators full access to impacted regions and communities to determine if Turkey has used chemical weapons in its military operations.

To concerned governments:

- Request an investigation of alleged Turkish chemical weapons use via existing OPCW mechanism.

- End arms sales and security assistance to Turkey.

- Pressure Turkey to end cross-border military operations in Iraq and Syria.

- Support and assist in return to peace negotiations between Turkey and the PKK to resolve the Kurdish issue by political means.

To international civil society:

- Support the demands listed here by signing this letter and engaging with relevant governments and international institutions.

November 30, 2022

Signatories:

- Souad Abdelrahman, Head of Palestine Women’s Association – Palestine

- Dr Goran Abdullah – Scotland

- Ismet Agirman, Kurdish activist – UK

- Prof Dr Tayseer A. Alousi, Secretary General of the Arab Assembly for Supporting Kurdish Issue and President Sumerian Observatory for Human Rights – Netherlands

- Dr Maha Al-Sakban, Centre for Women’s Human Rights board member – Iraq

- Mick Antoniw MS, Senedd Constituency Member, Welsh Labour Group, Counsel General and Minister for the Constitution – Wales

- Chiara Aquino, PhD Candidate, University of Edinburgh – Scotland

- Benedetta Argentieri, Journalist and filmmaker – Italy

- Rezgar Bahary, Journalist – UK

- Naamat Bedrdine, Politician and writer – Lebanon

- Walden Bello, International Adjunct Professor of Sociology, SUNY Binghamton, and recipient ot the Right Livelihood Award (aka Alternative Nobel Prize) in 2003 – USA

- Janet Biehl, Independent scholar, author, artist – USA

- Jonathan Bloch, Writer – UK

- Baroness Christine Blower, House of Lords – UK

- Debbie Bookchin, Journalist and author – USA

- Prof Bill Bowring, School of Law, Birkbeck College, University of London – UK

- Jane Byrne, Teacher – UK

- Robert Caldwell, Assistant Professor of Indigenous Studies, University at Buffalo – USA

- Campaign Against Criminalising Communities (CAMPACC) – UK

- CND (Campaign Against Nuclear Disarmament) – UK

- Margaret Cerullo, Hampshire College – USA

- Maggie Cook, UNISON NEC member – UK

- Mary Davis FRSA, Visiting Professor of Labour History at Royal Holloway University of London – UK

- Defend Kurdistan Initiative – UK

- Mary Dibis, Mousawat for Women – Lebanon

- Penelope Dimond, Writer and actor – UK

- Gorka Elejabarrieta Diaz, Basque Senator, Director EH Bildu International Relations Department – Basque Country

- Federal Executive Committee of Women’s Union Courage – Germany

- Silvia Federici, Author and Professor Emerita of Social Science, Hofstra University – USA

- Andrew Feinstein , Executive Director, Shadow World Investigations – UK

- Dr Phil Frampton, Author – UK

- Freedom Socialist Party – Australian Section

- Freedom Socialist Party – USA Section

- Andreas Gavrielidis, Greek-Kurdish Solidarity

- Lindsey German, Convenor Stop the War Coalition – UK

- Selay Ghaffar, Exiled women’s rights activist from Afghanistan

- Prof Barry Gills, Fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science – UK

- Dr Sarah Glynn, Writer – France

- Mustafa Gorer, Kurdish activist – UK

- Kirmanj Gundi, KHRO (Kurdistan Human Rights Observer) – UK

- Prof Michael Gunter, General Secretary of EU Turkey Civic Commission (EUTCC) – USA

- Rahila Gupta, Chair of Southall Black Sisters – UK

- Kazhal Hamarashid, Board member of the Toronto Kurdish Community Centre – Canada

- Niaz Hamdi, KHRO (Kurdistan Human Rights Observer) – UK

- John Hendy QC, Barrister – UK

- Nick Hildyard, Policy analyst – UK

- Ava Homa, Writer, journalist and activist – Canada/USA

- Srecko Horvat, Co-founder of DiEM25 & Progressive International

- Dr Stephen Hunt, PiK Ecology Network – UK

- John Hunt, Journalist – UK

- Alia Hussein, Women’s Affairs Committee of the General Federation of Iraqi Trade Unions – Iraq

- Lord Hylton, House of Lords – UK

- Serif Isildag, Journalist – UK

- Ruken Isik, Adjunct Lecturer at American University – USA

- Dafydd Iwan, Former President Plaid Crymru – Wales

- Jin Women’s Association – Lebanon

- Ramsey Kanaan, Publisher, PM Press – UK

- James Kelman, Author – Scotland

- Gulay Kilicaslan, Department of Law and Legal Studies, Carleton University – Kanada

- Nida Kirmani, Women Democratic Front, Haqooq-e-Khalq Party – Pakistan

- Nimat Koko Hamad, Associate researcher and gender specialist – Sudan

- Kongra Star Women’s Movement – Rojava & Syria

- Claudia Korol, Founder of Popular Education Collective Pañuelos en Rebeldía, Feministas de Abya Yala – Argentina

- Balazs Kovacs, Consultant – UK

- Kurdish Women’s Relations Office (REPAK) – Kurdistan Region of Iraq

- Şeyda Kurt, Journalist and Writer – Germany

- Coni Ledesma, International Women’s Alliance (IWA) Europe – Netherlands

- Dr Anjila Al-Maamari, Center for Strategic Studies to Support Women and Children – Yemen

- Aonghas MacNeacail, Scottish Gaelic poet – Scotland

- Fazela Mahomed, Kurdish Human Rights Action Group – South Africa

- Saleh Mamon, Campaign Against Criminalising Communities (CAMPACC) – UK

- Dr Carol Mann, Director of Women in War – France

- Mike Mansfield QC, Barrister – UK

- Dr Thomas Jeffrey Miley, Lecturer of Political Sociology, Fellow of Darwin College, University of Cambridge – UK

- Zahraa Mohamad, Journalist – Lebanon

- Francie Molloy, MP for Mid Ulster – Ireland

- David Morgan, Journalist – UK

- Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb, Green Party Member of the House of Lords – UK

- Maryam Namazie, Human rights activist, commentator, and broadcaster – UK

- Dr Marie Nassif-Debs, President of Association Equality-Wardah Boutros – Lebanon

- Doug Nicholls, General Secretary, General Federation of Trade Unions – UK

- Margaret Owen, O.B.E., President Widows for Peace through Democracy – UK

- Prof Felix Padel, Research associate at Center for World Environmental History, University of Sussex – UK

- Sarah Parker, Anti-Capitalist Resistance – UK

- Patriotic Democratic Socialist Party (PPDS) – Tunisia

- Peace in Kurdistan Campaign – UK

- Maxine Peake, Actress – UK

- Rosalind Petchesky, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Political Science, Hunter College & the Graduate Center, City University of New York – USA

- Dr Thomas Phillips, lecturer in law at Liverpool John Moore University – UK

- Eleonora Gea Piccardi, University of Coimbra, PhD candidate – Italy

- Ulisse Pizzi, Geologist, UK engineering consultancy – UK

- Dr Anni Pues, International human rights lawyer – UK

- Radical Women – USA

- Radical Women – Australia

- Bill Ramsay, Ex-President Educational Institute of Scotland and Convenor of Scottish National Party – Scotland

- Ismat Raza Shahjahan, President of Women Democratic Front – Pakistan

- Trevor Rayne, Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! – UK

- Gawriyah Riyah Cude, Women’s Trade Union Forum – Iraq

- Dimitri Roussopoulos, Writer, editor, publisher, political activist – Canada

- Nighat Said Khan, Women Democratic Front, Women Action Forum WAF – Pakistan

- Dr Michael Schiffmann, Linguist, English Department of the University of Heidelberg, Translator – Germany

- Paul Scholey, Morrish Solicitors – UK

- Bert Schouwenburg, International Trade Union Advisor – UK

- Chris Scurfield, Political activist – UK

- Stephen Smellie, Deputy Convenor UNISON Scotland and NEC member – Scotland

- Geoff Shears, Vice-Chair of the Centre for Labour and Social Studies(CLASS) – UK

- Tony Shephard, Musician and graphic designer – UK

- Tony Simpson, Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation – UK

- Radha D’Souza, Professor of law at the University of Westminster – UK

- Oskar Spong, Operator – UK

- Chris Stephens MP, Glasgow South West – Scotland

- Steve Sweeney, International Editor, Morning Star – UK

- Tooba Syed, Women Democratic Front – Pakistan

- Greta Sykes, Writer and artist – UK

- Tim Symonds, Novelist – UK

- Joly Talukder, General Secretary of the Bangladesh Garment Workers Trade Union Centre – Bangladesh

- Latifa Taamalah Women’s Committee – Tunisia

- Shavanah Taj, General Secretary Wales TUC – Wales

- Lisa-Marie Taylor, CEO of FiLiA – UK

- Saadia Toor, Women Democratic Front – Pakistan

- Tom Unterrainer, Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation – UK

- Prof Abbas Vali, Professor of Modern Social and Political Theory – UK

- Dr Federico Venturini, University of Udine – Italy

- Andy Walsh, Chair, Greater Manchester Law Centre – UK

- Julie Ward, Former MEP – UK

- Arthur West, Secretary, Kilmarnock and Loudon Trades Union Council – Scotland

- Prof Kariane Westrheim, Chair of EU Turkey Civic Commission (EUTCC) – Norway

- Alex Wilson, PhD student at York University in Toronto, Ontario – Canada

- Dr Fiona Woods, Lecturer, Technological University Shannon – Ireland

- Paula Yacoubian, Member of Parliament – Lebanon

- Rosy Zúñiga, Latin America and Caribbean Popular Education Council CEAAL – Mexico

by DGR News Service | Sep 9, 2022 | NEWS, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: By biomass, krill are the most abundant species in the world and the main food source for all baleen whales — including blue whales, the largest animals on the planet and the largest ever known to have existed.

Regardless of how abundant it is — see Passenger Pigeons, Buffalo, or Great Auks — any species that becomes economically valuable in a growth economy will likely experience decline and collapse. That is the nature of endless growth.

Krill are no different. Between overfishing that has more than quadrupled in 15 years and global climate destabilization that has already warmed the Antarctic by 2.5° C since the 1940s, Krill, like all life on Earth, are in trouble — yet another sign that industrial civilization is driving an ongoing ecological collapse and accelerating us deeper into the 6th mass extinction (an extermination, in this case) of life on Earth.

by Elizabeth Claire Alberts / Mongabay

- Antarctic krill are one of the most abundant species in the world in terms of biomass, but scientists and conservationists are concerned about the future of the species due to overfishing, climate change impacts and other human activities.

- Krill fishing has increased year over year as demand rises for the tiny crustaceans, which are used as feed additives for global aquaculture and processed for krill oil.

- Experts have called on the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the group responsible for protecting krill, to update its rules to better protect krill; others are calling for a moratorium on krill fishing.

- Antarctic krill play a critical role in maintaining the health of our planet by storing carbon and providing food for numerous species.

Antarctic krill — tiny, filter-feeding crustaceans that live in the Southern Ocean — have long existed in mind-boggling numbers. A 2009 study estimated that the species has a biomass of between 300 million and 500 million metric tons, which is more than any other multicellular wild animal in the world. Not only are these teensy animals great in number, but they’re known to lock away large quantities of carbon through their feeding and excrement cycles. One study estimates that krill remove 23 million metric tons of carbon each year — about the amount of carbon produced by 35 million combustion-engine cars — while another suggests that krill take away 39 million metric tons each year. Krill are also a main food source for many animals for which Antarctica is famous: whales, seals, fish, penguins, and a range of other seabirds.

But Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) are not “limitless,” as they were once described in the 1960s; they’re a finite resource under an increasing amount of pressure due to overfishing, pollution, and climate change impacts like the loss of sea ice and ocean acidification. While krill are nowhere close to being threatened with extinction, the 2022 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicated that there’s a high likelihood that climate-induced stressors would present considerable risks for the global supply of krill.

“Warming that is occurring along the Antarctic Peninsula and Scotia Sea has caused the krill stocks in those areas to shrink and the center of that population has moved southwards,” Kim Bernard, a marine ecologist at Oregon State University, wrote to Mongabay via email while stationed in the Antarctic Peninsula. “This tells us already that krill numbers aren’t endless.”

Concerns are amassing around one place in particular: a krill hotspot and nursery at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula known as “Area 48,” which harbors about 60 million metric tons of krill. Not only has this area become a key foraging ground for many species that rely on krill, but it also attracts about a dozen industrial fishing vessels each year. The amount of krill they catch has been steadily increasing over the years. In 2007, vessels caught 104,728 metric tons in Area 48; in 2020, they caught 450,781 metric tons.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the group responsible for protecting krill, has imposed rules to try and regulate krill fishing in the Southern Ocean, but many conservationists and scientists say the rules need to be updated to reflect the changing dynamics of the marine environment. That said, many experts argue that the Antarctic krill fishery can be sustainable if managed correctly.

Antarctic krill are under pressure due to overfishing, pollution, and climate change impacts like the loss of sea ice and ocean acidification. Image courtesy of Dan Costa.

Approaching krill ‘trigger level’

Fishing nations started casting their nets for Antarctic krill in the 1970s, believing these small crustaceans could provide a valuable source of animal protein that would alleviate world hunger. But in the 1980s, interest in krill fishing waned, partly because no one was sure how to remove the high levels of fluoride in their exoskeletons. It was also generally difficult to process krill into food fit for human consumption and to successfully sell these foods to consumers.

But krill fishing never really stopped. In fact, it’s been gaining momentum ever since krill was identified as a suitable animal feed. Now krill is mainly used as a feed additive in the global aquaculture industry, as well as to produce krill oil that goes into omega-3 dietary supplements.

In 1982, the CCAMLR was established to address concerns that the Antarctic krill fishery could have a substantial impact on the marine ecosystem of the Southern Ocean. In 2010, the CCAMLR established a rule limiting catches to 5.61 million metric tons across four subsections of Area 48 where krill fishing was concentrated. The rule also dictated that krill fishing in these areas must stop if the total combined catch reached a “trigger level” of 620,000 metric tons.

So far, total catches have not exceeded this boundary. But krill fishing nations, which currently include Norway, China, South Korea, Ukraine and Chile, are inching closer to it as they expand their operations.

“As long as catches were significantly below the trigger level, I think people felt like, ‘Oh, we don’t need to be too worried,’” Claire Christian, executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC), told Mongabay. “They’re still not there yet, but as they’ve been getting closer, there’s been more pressure on CCAMLR scientists and policymakers to look at the fishery and develop a more comprehensive management system.”

Stuart Corney, an Antarctic krill expert at the University of Tasmania, said a primary concern is that most krill fishing is concentrated at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where krill are known to spawn, creating “localized depletion.”

“If we overexploit the krill in that region, it can have significant implications for the population in a greater area of Antarctica … so it needs to be carefully managed efficiently,” Corney told Mongabay.

Another issue with the current catch limits is that they don’t consider the impacts of climate change, according to Bernard.

“This is particularly important at the Antarctic Peninsula where the fishing effort is greatest because the Antarctic Peninsula is one of the most rapidly warming regions on the planet,” Bernard said. “There is also evidence that areas along the Antarctic Peninsula such as the Gerlache Strait are important overwintering grounds for Antarctic krill, particularly for the juveniles and larvae that shelter in the bays and fjords along the Peninsula at that time of year. There is no seasonal closure on the krill fishery and because of delayed sea ice formation in the region around the Gerlache Strait the fishery can extend into winter. When that happens, the fishery could remove massive numbers from the next reproductive cohort of the population.”

Krill are known to lock away large amounts of carbon through their feeding and excrement cycles. Image courtesy of Aker.

Not only will global heating deplete the sea ice that krill depend upon, but research has suggested that warming waters will impact krill growth, possibly leading to a 40% decline in the mass of individual krill by the end of the century. Other research has argued that ocean acidification, another impact of climate change, will reduce krill development and hatchling rate and lead to an eventual collapse in 2300.

Progress and setbacks

In 2019, CCAMLR members agreed on a scientific work plan with the view of adopting new conservation measures based on it in 2021. This process was delayed due to COVID-19, but CCAMLR members are expected to reinvigorate these discussions at the next meeting in October, said Nicole Bransome, a marine ecologist at Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy.

“Hopefully, the scientists will have been able to put all of the science together … and come up with a new measure that spreads the catch out in space to reduce the impacts on predators,” Bransome told Mongabay. However, she said she’s concerned about a possible move to increase krill catch limits, which was discussed at last year’s meeting.

“Preliminary analysis suggests that the overall catch level could go up, but as of last year’s meeting, there were still a lot of uncertainties with that model and the parameters used in that model,” she said. “We would rather see that if the catch limits change, they’re based on a robust model and good science.”

While many experts say krill fishing can be sustainable if managed correctly, others call for stronger measures to protect krill.

Over the past decade, conservationists and scientists have been proposing the establishment of three new marine protected areas (MPAs) in East Antarctica, the Antarctic Peninsula and the Weddell Sea, ranging over 4 million square kilometers (1.5 million square miles) of the Southern Ocean, which would help protect krill with no-take zones.

“There is now strong scientific evidence that we need strict protection of at least 30% of the global ocean to effectively protect it,” said Christian of ASOC.

Yet the CCAMLR, which makes decisions based on consensus, has rejected the MPA proposal year after year.

Sophie Nodzenski, a senior campaigner at the Changing Markets Foundation, an NGO that works to expose irresponsible corporate practices and to foster sustainability, said the CCAMLR’s continued rejection of the MPAs had led her organization to call for a moratorium on krill fishing. (The Bob Brown Foundation, an Australian NGO that works to protect the natural world, has previously called for a similar ban on krill fishing to be put in place.)

“We are aware it’s a strong stand,” Nodzenski told Mongabay. “But there is a climate emergency, and there is a worry about how krill fishing is exacerbating the threats from climate change. So why don’t we just put a moratorium in place?”

In a report released Aug. 11 — for the first World Krill Day — the Changing Market Foundation details concerns for the planned expansion of the krill industry, which could push catch limits past the current trigger points. It also reveals how Norwegian company Aker Biomarine dominates the industry, supplying krill feed for farmed salmon operations around the world.

Consumers could alleviate pressure on krill “by pushing for a change in the way we are harvesting krill,” Nodzenski said. “If there’s less demand for products, eventually you could see a knock-on effect on the krill harvesting.”

Krill is fished so it can be used as a feed additive in the global aquaculture industry, as well as to produce krill oil that goes into omega-3 dietary supplements. Image courtesy of Pete Harmsen.

Is change coming?

The report also casts doubt on the CCAMLR’s ability to make timely decisions to protect krill.

“This is because CCAMLR’s decision-making process is based on consensus; as long as some members oppose changes to the status quo (in this regard, China and Russia), decisions cannot go ahead,” the authors write. “This means that, for the foreseeable future, it is difficult to envisage how management measures regarding krill can evolve and adapt to our rapidly changing climate.”

Yet other experts say the CCAMLR has the capacity to authorize effective changes.

“CCAMLR has a range of mechanisms it can use to further ecosystem protection,” Bransome of Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy said. “Lots of progress has been made … and we are looking to CCAMLR to achieve additional protections at the upcoming CCAMLR meeting.”

Corney from the University of Tasmania said he believes it’s important for fishing nations to continue working together through the CCAMLR to protect the Southern Ocean.

“If some nations started pulling out of CCAMLR … they’re not bound by the rules [and] they can do their thing,” Corney said. “We want all nations to remain in CCAMLR. We want them to sign up for the agreements that are reached. That means we have to accept the structure that is there.”

While opinions differ about how to manage the krill fishery, experts tend to agree on one thing: krill are too valuable to lose in this moment of climate crisis.

Antarctic krill are also a main food source for many animals, including whales, seals, fish, penguins, and a range of other seabirds. Image by Brett Wilks /Australian Antarctic Division.

“Even though Antarctic krill are seemingly far removed from our lives, some of that excess carbon dioxide we’ve pumped into the air is exported to the sea floor by krill, where it will remain for thousands of years,” Bernard said. “Without Antarctic krill, Earth would be even hotter than it already is.”

Citations:

Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E. A., Jessopp, M. J., & Loeb, V. (2009). A re-appraisal of the total biomass and annual production of Antarctic krill. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 56(5), 727-740. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2008.12.007

Tarling, G. A., & Thorpe, S. E. (2017). Oceanic swarms of Antarctic krill perform satiation sinking. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1869), 20172015. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.2015

Belcher, A., Henson, S. A., Manno, C., Hill, S. L., Atkinson, A., Thorpe, S. E., … Tarling, G. A. (2019). Krill faecal pellets drive hidden pulses of particulate organic carbon in the marginal ice zone. Nature Communications, 10(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08847-1

Spiller, J. (2016). Frontiers for the American century: Outer space, Antarctica, and cold war nationalism. Springer.

Pörtner, H., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., … Rama, B. (Eds.) (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Retrieved from IPCC website: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

Klein, E. S., Hill, S. L., Hinke, J. T., Phillips, T., & Watters, G. M. (2018). Impacts of rising sea temperature on krill increase risks for predators in the Scotia Sea. PLOS ONE, 13(1), e0191011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191011

Kawaguchi, S., Ishida, A., King, R., Raymond, B., Waller, N., Constable, A., … Ishimatsu, A. (2013). Risk maps for Antarctic krill under projected Southern Ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change, 3(9), 843-847. doi:10.1038/nclimate1937

Changing Markets Foundation. (2022). Krill, Baby, Krill: The corporations profiting from plundering Antarctica. Retrieved from https://changingmarkets.org/portfolio/fishing-the-feed/

Banner image caption: Antarctic krill. Image courtesy of Dan Costa.

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

by DGR News Service | Jul 29, 2022 | Climate Change, NEWS

Editor’s note: As the climate crisis accelerates, extreme weather is causing crop failures and other disasters. Today’s article shares a grim projection: the world may see more than 1 billion climate refugees by 2050.

This problem is not new. Throughout the last 10,000 years, many civilizations have grown powerful, destroyed their land and water, and collapsed. Our situation today is only different because of scale. Modern civilization is global, and so the problems are worse.

Industrial civilization is a failed experiment. Wealthy consumer societies have been built by vast quantities of fossil energy and harvesting the natural world. Reversing this crisis will require a basic restructuring of our entire society. The economics of growth are obsolete. Destructive industries must be dismantled. Population must be stabilized and then reduced. Consumerism must be abandoned. Wild nature must be protected and allowed to expand and repair itself. And as centralized systems for food production and other necessities fail, new grassroots structures will need to be created.

“The media report on these crises as though they are all separate issues. They are not. They are inextricably entangled with each other and with the culture that causes them…

These problems are urgent, severe, and worsening… [they] are not hypothetical, projected, or “merely possible” like Y2K, asteroid impacts, nuclear war, or supervolcanoes. These crises are not “possible” or “impending”—they are well underway and will continue to worsen. The only uncertainty is how fast, and thus how long our window of action is.”

– From the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet

NB: This report is anthropocentric and focused purely on government aid programs which have limited ability to solve systemic issues.

From The Institute for Economics and Peace / September 9, 2020

Today marks the launch of the inaugural Ecological Threat Register (ETR), that measures the ecological threats countries are currently facing and provides projections to 2050. The report uniquely combines measures of resilience with the most comprehensive ecological data available, to shed light on the countries least likely to cope with extreme ecological shocks. The report is released by leading international think-tank the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP), which produces indexes such as the Global Peace Index and Global Terrorism Index.

Key Results

- 19 countries with the highest number of ecological threats are among the world’s 40 least peaceful countries including Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Chad, India and Pakistan.

- Over one billion people live in 31 countries where the country’s resilience is unlikely to sufficiently withstand the impact of ecological events by 2050, contributing to mass population displacement.

- Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa are the regions facing the largest number of ecological threats.

- 3.5 billion people could suffer from food insecurity by 2050; which is an increase of 1.5 billion people from today.

- The lack of resilience in countries covered in the ETR will lead to worsening food insecurity and competition over resources, increasing civil unrest and mass displacement, exposing developed countries to increased influxes of refugees.The Ecological Threat Register analyses risk from population growth, water stress, food insecurity, droughts, floods, cyclones, rising temperatures and sea levels. Over the next 30 years, the report finds that 141 countries are exposed to at least one ecological threat by 2050. The 19 countries with the highest number of threats have a combined population of 2.1 billion people, which is around 25 per cent of the world’s total population.The ETR analyses the levels of societal resilience within countries to determine whether they have the necessary coping capacities to deal with future ecological shocks. The report finds that more than one billion people live in countries that are unlikely to have the ability to mitigate and adapt to new ecological threats, creating conditions for mass displacement by 2050. The country with the largest number of people at risk of mass displacements is Pakistan, followed by Ethiopia and Iran. Haiti faces the highest threat in Central America. In these countries, even small ecological threats and natural disasters could result in mass population displacement, affecting regional and global security.

Regions that have high resilience, such as Europe and North America, will not be immune from the wider impact of ecological threats, such as a significant number of refugees. The European refugee crisis in the wake of wars in Syria and Iraq in 2015 saw two million people flee to Europe and highlights the link between rapid population shifts with political turbulence and social unrest.

However, Europe, the US and other developed countries are facing fewer ecological threats and also have higher levels of resilience to deal with these risks. Developed countries which are facing no threats include Sweden, Norway, Ireland, and Iceland. In total there are 16 countries facing no threats.

Steve Killelea, Founder & Executive Chairman of the Institute for Economics and Peace, said:

“Ecological threats and climate change pose serious challenges to global peacefulness. Over the next 30 years lack of access to food and water will only increase without urgent global cooperation. In the absence of action civil unrest, riots and conflict will most likely increase. COVID-19 is already exposing gaps in the global food chain”.

Many of the countries most at risk from ecological threats are also predicted to experience significant population increases, such as Nigeria, Angola, Burkina Faso and Uganda. These countries already struggle to address ecological issues. They already suffer from resource scarcity, low levels of peacefulness and high poverty rates.

Steve Killelea, said:

“This will have huge social and political impacts, not just in the developing world, but also in the developed, as mass displacement will lead to larger refugee flows to the most developed countries. Ecological change is the next big global threat to our planet and people’s lives, and we must unlock the power of business and government action to build resilience for the places most at risk.“

Food Insecurity

The global demand for food is projected to increase by 50 per cent by 2050, meaning that without a substantial increase in supply, many more people will be at risk of hunger. Currently, more than two billion people globally face uncertain access to sufficient food. This number is expected to increase to 3.5 billion people by 2050 which is likely to affect global resilience.

The five most food insecure countries are Sierra Leone, Liberia, Niger, Malawi and Lesotho, where more than half of the population experience uncertainty in access to sufficient food to be healthy. COVID-19 has exacerbated levels of food insecurity and given rise to substantial price increases, highlighting potential volatility caused by future ecological change.

In high income countries, the prevalence of undernourishment is still high at 2.7 per cent, or one in 37 people do not have sufficient food to function normally. Undernourishment in developed countries is a byproduct of poverty; Colombia, Slovakia and Mexico have the highest undernourishment rates of OECD countries.

Water Stress

Over the past decade, the number of recorded water-related conflict and violent incidents increased by 270 per cent worldwide. Since 2000, most incidents have taken place in Yemen and Iraq, which highlights the interplay between extreme water stress, resilience and peacefulness, as they are among the least peaceful countries as measured by the Global Peace Index 2020.

Today, 2.6 billion people experience high or extreme water stress – by 2040, this will increase to 5.4 billion people. The majority of these countries are located in South Asia, Middle East, North Africa (MENA), South-Western Europe, and Asia Pacific. Some of the worst affected countries by

2040 will be Lebanon, Singapore, Israel and Iraq, while China and India are also likely to be impacted. Given the past increases in water-related conflict this is likely to drive further tension and reduce global resilience.

Natural Disasters

Changes in climate, especially the warming of global temperatures, increases the likelihood of weather-related natural disasters such as droughts, as well as increasing the intensity of storms and creating wetter monsoons. If natural disasters occur at the same rate seen in the last few decades, 1.2 billion people could be displaced globally by 2050. Asia Pacific has had the most deaths from natural disasters with over 581,000 recorded since 1990. Earthquakes have claimed the most lives in the region, with a death toll exceeding 319,000, followed by storms at 191,000.

Flooding has been the most common natural disaster since 1990, representing 42 per cent of recorded natural disasters. China’s largest event were the 2010 floods and landslides, which led to 15.2 million displaced people. Flooding is also the most common natural disaster in Europe, accounting for 35 per cent of recorded disasters in the region and is expected to rise.

19 countries included in the ETR are at risk of rising sea levels, where at least 10 per cent of each country’s population could be affected. This will have significant consequences for low-lying coastal areas in China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand over the next three decades – as well as cities with large populations like Alexandria in Egypt, the Hague in the Netherlands, and Osaka in Japan.

The Institute for Economics and Peace is an international and independent think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. It has offices in Sydney, Brussels, New York, The Hague, Mexico City and Harare.

Photo illustration of climate refugees by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash.

by DGR News Service | Nov 17, 2021 | Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

This story first appeared in Opendemocracy.

The young indigenous leadership of Múte Bourup Egede is battling for green sovereignty in a time of climate collapse.

By Adam Ramsay and Aaron White

In 2016, Greenland’s then minister responsible for economic development, Vittus Qujaukitsoq, welcomed the appointment of Rex Tillerson, the former CEO of Exxon Mobil, as US secretary of state. Despite representing the centre-Left party Siumut (Forward) and being surrounded by some of the most visible consequences of the warming world, Qujaukitsoq and his colleagues saw the growing potential for mining and drilling brought by the melting glaciers on the world’s biggest island as an opportunity to bring in the cash which would allow the long-desired independence from Denmark.

They aren’t alone. While the melting of Arctic ice is causing the world’s oceans to overflow and disrupting its weather systems, it has also unleashed a whole new geopolitical race. Earlier this year, the US Geological Survey estimated that the region’s rocks contain 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil, and 30% of undiscovered gas – carbon sinks which have been greedily eyed up by states and oil companies alike. And many of these reserves lie in the seas west of Greenland – where there are an estimated 17.5 billion undiscovered barrels of oil, enough to supply the whole planet for six months, at current usage rates.

And because the Arctic is the fastest warming part of the planet, the ice shielding these prehistoric deposits from prying drills is thinning, and disappearing, at an alarming rate.

But if some see this as an opportunity, others understand the absurdity of using climate change as a means to extract more fossil fuels and further change the climate. And this, alongside broader questions about mining, have shaped politics in the country this year.

In the spring, the governing Siumut party split, and its liberal coalition partners, the Democrats, resigned from the government, triggering a snap election in May.

The winner was the eco-socialist party Inuit Ataqatigiit. And in June, the new government banned all future oil and gas exploration from Greenland’s territory.

“The price of oil extraction is too high. This is based upon economic calculations, but considerations of the impact on climate and the environment also play a central role in the decision,” the government stated in July.

It’s not just oil and gas drilling that are contentious. When Donald Trump notoriously inquired about purchasing the island in 2019, he’d just had a briefing on its deposits of a number of minerals, many of which are likely to play a crucial role in the geopolitics of the coming decades. Among these are large quantities of uranium, and what are thought to be the world’s second biggest reserves of rare earth minerals – demand for which has soared in recent years because of their use in batteries for electric cars, computer chips and other tools of the high tech, low carbon economy.

Seen that way, Trump’s statement was probably less a random outburst and more a crude expression of the reality of Greenland’s role in the future of global geopolitics.

Biden, as ever, works in more subtle ways. In February, in discussion with tech giants like Alphabet (Google) and Facebook, he signed an executive order instigating a review of the supply chain of rare earth metals due to a global shortage and China’s dominance of the market. It seems implausible that the review won’t have produced significant discussion in US intelligence circles about the world’s largest deposits outside China, just a few hundred miles from Maine.

In March, the Polar Research and Policy Initiative expressed concerns about “the security implications of China’s near monopoly of rare earths and other minerals for the UK and its North American, European and Pacific allies”, especially given their significance to “strategically important sectors such as defence and security, green energy and technology”. The think tank called on the ‘five eyes’ intelligence alliance between the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada to team up with Greenland as part of a strategic resources partnership.

Greenland, says the website Mining Technology, “could be vital for tipping the scales in a trade war between global superpowers”.

In the midst of this global gallop for Greenland, with the world’s major powers, billionaire investors and intelligence agencies getting in on the act, the country has had some coverage in the global media of late.

What is often left out of the conversation, however, is the fascinating domestic dynamics among this Arctic island’s 57,000 people. Greenlanders’ struggle for sovereignty in the context of global capitalism, extractivism and climate collapse is an inspiring example of 21st-century indigenous resistance.

A young socialist indigenous climate leader

“There are two issues that have been important in this election campaign: people’s living conditions is one. And then there is our health and the environment,” Inuit Ataqatigiit leader Múte Bourup Egede told the Greenlandic public broadcaster KNR following his election victory in April.

Egede, 34, is the youngest prime minister Greenland’s had since it achieved a degree of home rule in the 1970s, and has led the democratic socialist and pro-independence party since 2018.

This [election] has sent shivers down the spine of many mining executives

In the recent election, the party, known as IA, centred its campaign on its opposition to an international mining project by Greenland Minerals, an Australian-based and Chinese-owned company that is seeking to extract uranium and neodymium from the Kvanefjeld mine in the south of the country. Neodymium is a crucial component of a broad range of technologies, from some kinds of wind turbine to electric cars, because it can be used to make small, lightweight, but powerful and permanent magnets, while uranium is used for both nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

“We must listen to the voters who are worried. We say no to uranium mining,” Egede told the KNR. His party also promised to ban all explorations of radioactive deposits, and, while it does not oppose the mining of rare earth minerals in principle, it insists it must be better regulated.

Egede and the IA won 37% of the vote, ending the tenure of Siumut, the party which had been in power for most of the time since 1979. Siumut was supportive of the Kvanefjeld mining project, assisting Greenland Minerals to gain preliminary approval and ending a previous zero tolerance policy for uranium mining.

There is now a bill being debated in the Greenland parliament to ban the uranium mining project and all mining that contains radioactive by-products.

According to Mark Nuttall, an anthropologist at the University of Alberta and the head of the Climate and Society research programme at the Greenland Climate Research Centre: “This [election] has sent shivers down the spine of many mining executives as to what kind of future mining would take place in Greenland.”

Under the direction of Egede, the IA-led government has also taken several significant steps in recent months to curb fossil fuel production.

Last week in Glasgow, Egede announced that Greenland will be joining the Paris Agreement. In 2016, under the leadership of Siumut, Greenland had invoked a territorial exemption to the climate agreement when Denmark joined.

Greenland, which is technically a self-governing territory of Denmark, claimed at the time that the country was dependent on its oil, gas and natural mineral reserves for its economy.

“The Arctic region is one of the areas on our planet where the effects of global warming are felt the most, and we believe that we must take responsibility collectively. That means that we, too, must contribute our share,” Egede said last week.

Egede’s government also pledged to develop its renewable energy capability, especially hydropower: “Greenland has hydropower resources that exceed our country’s needs. These large hydropower resources can be utilised in collaboration with national and international investors who need large amounts of cheap and renewable energy.”

The Northwest Passage

The rush for the rare earth minerals vital to so many low carbon technologies isn’t the only way that climate change is moving the country from the periphery of global geopolitics to its core. When the huge container ship the Ever Given blocked the Suez Canal in March, the world was reminded how much of its trade passes through its two major transcontinental waterways – Suez and Panama.

As much of the Arctic Ocean becomes ice-free for greater parts of the year, new potential trade routes open up, most significantly, the Northwest Passage across the top of North America, and the Northern Sea Route, above Eurasia.

The vast majority of Greenland’s settlements – including the capital, Nuuk – lie on the west coast of the country, along the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay. When travelling from Asia or western North America to Europe or the east coast of North America through the Northwest Passage, this is the final stretch, positioning Nuuk as a potential hub on a future major shipping route.

The struggle for sovereignty

Nearly 90% of the population of Greenland are indigenous Inuit people, who have inhabited the island for thousands of years. Although they’ve been colonised for the last thousand years by Nordic powers, they have maintained their own language and culture.

Norsemen first settled on the island in the tenth century, and in 1261 Greenland formally became part of Norway. In 1814 Greenland became a Danish territory – and in 1953 the island became fully integrated into the Danish state. (During World War II, when Denmark was conquered by the Nazis, Greenland was de facto under US control.)

“The official Danish view was that Greenland was actually a dependency; it wasn’t a colony in the sense of its colonies in the West Indies and other places,” Nuttall explained. This, he said, was “because of this historic view that Greenland had long been part of this Nordic Commonwealth from the Norse settlements of the tenth century onwards”.

But the Inuit people don’t always see it that way. During the Black Lives Matter global movement in 2020, younger Greenlanders, including the 21-year-old hip hop artist Josef Tarrak-Petrussen, called for the removal of Danish colonial statues in Nuuk.

Denmark finally granted home rule in 1979. And in 2008 Greenland voted in favour of the Self-Government Act, which transferred more power to the island’s government – and effectively marked the beginning of state formation.

This self rule act recognises Greenland as a nation with the right to independence if it chooses it. Currently Greenland has nearly full sovereignty, with the exception of the areas of foreign policy and defence. The Arctic island currently receives an annual grant of around $585m from Denmark.

In recent years, questions around sovereignty have in many ways defined the political and environmental policies of the island. Many of the political parties support independence.

However, this financial dependence on Denmark makes the prospect of full independence quite difficult: the grant accounts for nearly 20% of the island’s income, while fishing makes up around 90% of its exports.

In order to gain full autonomy from Denmark, Greenland needs to develop a self-sufficient economy. However, this likely requires the development of lucrative extractive industries which will deepen the island’s dependence on (foreign) international capital.

“If we go back ten years, mining was seen as the major way to [become politically independent], and there was great excitement,” said Nuttall.

However in recent years this attitude towards mining has changed considerably due to a host of factors including a downturn in global commodity markets, a greater emphasis on renewable energy and attention given to the climate crisis.

“Mining is going to be one pillar of an economic development strategy that will include other things such as the development of tourism, expansion of the fishing industry… and expanding renewables,” Nuttall explained.

The current government is now focusing on investments in the island’s enormous hydropower potential, which has the potential to grow as glaciers melt and which will allow a reduction in petrol imports, one of the country’s main expenses. Kalistat Lund, the minister for agriculture, self-sufficiency, energy and environment, stated that the government is “working to attract new investments for the large hydropower potential that we cannot exploit ourselves”.

The island is also currently expanding its airports and promoting tourism. Currently the only flights available to Greenland are from Reykjavik or Copenhagen.

Greenland often appears in discussions about climate change – usually in the context of films of starving polar bears, adorable Arctic foxes and rutting muskox; or melting glaciers diverting the Gulf Stream and raising global sea levels, flooding cities across the planet. Ice cores from Greenland, like those of Antarctica, help us understand historic variations in the composition of our atmosphere and in our climate, and have been vital for scientists’ understanding of the science of climate change.

These things are all true, and each Arctic species being pushed to extinction by the warming of the world is a tragedy. But what’s also true is that Greenland is home to tens of thousands of people, with their own history and culture, politics and organisations; a people who, after a thousand years of colonisation, are starting to assert both their independence from Denmark and their sovereignty in the face of the global market. And, who, along with other indigenous communities around the world, are starting to lead a fightback against the industrial, extractive capitalism that’s killing the planet.