by DGR News Service | Mar 1, 2022 | ANALYSIS

Editor’s note: It is far too easy for radicals with a systemic analysis to become paralyzed at the scope of necessary change. At its best, radical analysis informs strategic actions in the here-and-now that helps us create a better future. At worst, it enables a nihilistic resignation that prevents people from taking action. We advocate for the middle ground: using radical analysis to inform a practical radical politics in the here and now.

But lest we become tempted to engage in tepid reformism, we must remember that practicality does not mean compromising on fundamental issues. When it comes to ecology, for example, any conflict between the ecologically necessary and politically feasible must be settled in favor of the ecologically necessary. However, the ecologically necessary will not spontaneously evolve; we must work for it, starting here and now.

This piece from pro-feminist and environmental activist Robert Jensen dives into this thorny balance, and challenges each us: what can you begin doing now that is based in a radical understanding of the problems we face, and also is practical and effective in the context of a profoundly conservative society? We welcome discussion in the comments section.

by Robert Jensen / February 4, 2022

We need to be practical when it comes to politics, to work for policies that we can enact today, inadequate though they may be to answer calls for social justice and ecological sustainability. We also need to maintain a relentlessly radical analysis, to highlight the failures of systems and structures of power, aware that policies we might enact today won’t resolve existing crises or stave off collapse. Both things are true, and both things are relevant to the choices we make.

Politics is the art of the possible, and politics also is the pursuit of goals that are impossible. We can pursue reforms today, knowing them to be inadequate, with revolutionary aims for tomorrow, knowing that the transformation needed will likely come too late. These two obligations pull us in different directions, often generating anger and anxiety. But it is easier—or, at least, should be easier—to handle that tension as we get older. Aging provides more experience with frustration, along with greater capacity for equanimity. Frustration is inevitable given our collective failure, our inability as a species to confront problems in ways that lead to meaningful progress toward real solutions. Equanimity allows us to live with that failure and remember our moral obligation to continue struggling. Frustration reminds us that we care about the ideals that make life meaningful. Equanimity makes living possible as we fall short of those ideals.

If these sound like the ramblings of an old person, well, this past year I got old. Not necessarily in years, because not everyone would consider sixty-three to be old. Not in health, because I’m holding up fairly well. But I am old in outlook, in my current balance of frustration and equanimity. For me, getting old has meant no longer seeing much distinction between righteous indignation and self-righteous indignation. I have let go of any sense of moral superiority that I felt in the past, but at the same time I have grown more confident in the soundness of the framework of analysis I use to understand the world. I also am more aware that offering what I believe to be a compelling analysis doesn’t always matter much to others. I have not given up, but I have given over more to the reality of limits, both of humans and the biophysical limits of the ecosphere. With age, I have gotten more practical while my analysis has gotten more radical.

In this essay I want to present a case for a practical radical politics—holding onto radical analyses while making decisions based on our best reading of the threats and opportunities in the moment. This requires consistency in analysis (which is always a good thing) while being wary of dogmatism in strategy (which is almost always a bad thing). My plan is to articulate the values on which my worldview is based; identify the hierarchical systems within the human family that undermine those values; and describe the history of the ecological break between the human family and the larger living world. From the analytical, I will offer thoughts on coping with the specific political moment of 2022 in the United States and with long-term global ecological realities. I have no grand strategy to propose, but instead will try to face my fears about the tenuous nature of life today politically and the even more tenuous nature of what lies ahead ecologically.

Working for what is possible requires commitment. Recognizing what is not possible requires humility. All of it requires us to embrace the anguish that is inevitable if we face the future without illusions.

VALUES

Dignity, Solidarity, Equality

In a multicultural world, we should expect conflict over differences in value judgments. But at the level of basic values—not judgments about how to live those values, but the principles we hold dear—there is considerable unanimity. No matter what religious or secular philosophical system one invokes, it’s common for people to agree on the (1) inherent dignity of all people, (2) importance of solidarity for healthy community life, and (3) need for a level of equality that makes dignity and solidarity possible. Most conflicts over public policy emerge from the many devils lurking in the details, but we can at least be clearer about those conflicts if we articulate basic principles on which most people agree.

The dignity of all people is an easy one. If someone were to say “People in my nation/religion/ethnic group have greater intrinsic value than others,” most of us would treat that person as a threat to the body politic. People may believe that their nation embodies special political virtues, or that their religion has cornered the market on spiritual insights, or that their ethnic group is a source of pride. But very few will actually say that they believe that their children are born with a greater claim to dignity than children born at some other spot on Earth.

Solidarity is an easy one, too. Except for the rare eccentric, we all seek a sense of connection in community with others. Humans are social animals, even “ultrasocial” according to some scholars. We may value our privacy and sometimes seek refuge from others in a harried world, but more important than occasional solitude is our need for a sense of belonging. Today, that solidarity need not be limited to people who look like me, talk like me, act like me. Solidarity in diversity—connecting across differences—is exciting and enriching.

Equality may seem more contentious, given the political wrangling over taxing wealth and providing a social safety net. But there is ample evidence that greater equality makes social groups stronger and more cohesive, leading to better lives for everyone. Hoarding wealth is a feature of the many societies since the invention of agriculture (more on that later), but even people with a disproportionate share of the world’s wealth acknowledge the corrosive effects of such dramatic disparities and support higher taxes on the rich.

That’s why some version of the “ethic of reciprocity”—the claim that we should treat others as we would like to be treated—shows up in so many religious and secular philosophical systems. In the first century BCE, the Jewish scholar Hillel was challenged by a man to “teach me the whole Torah while I stand on one foot.” Hillel’s response: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. That is the whole Torah, while the rest is the commentary thereof; go and learn it.” In Christianity, Jesus phrased it this way in the Sermon on the Mount: “So whatever you wish that someone would do to you, do so to them; for this is the law and the prophets” (Matt. 7:12). In Islam, one of the Prophet Muhammad’s central teachings was, “None of you truly believes until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself” (Hadith 13). In secular Western philosophy, Kant’s categorical imperative is a touchstone: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” Rooted in this ethic, it’s not a big leap to Marx’s “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs,” which is why a third of respondents to a US survey identified the phrase as coming from the US Constitution and another third said they weren’t sure.

Acknowledging these common values doesn’t magically resolve conflicts over public policy or bridge cultural divides. Fear, arrogance, and greed can lead people to ignore their values. But asking people to affirm these values, which most of us claim to hold, creates a foundation for public dialogue about the hierarchies we see all around us.

Against Hierarchy

If everyone took those values seriously, everyone would reject the violence, exploitation, and oppression that defines so much of the modern world. Only a small percentage of people in any given society are truly sociopaths—people incapable of empathy, who are not disturbed by cruel and oppressive behavior. So, a critique of the suffering that hierarchies produce should resonate with most people and lead to widespread resistance. Yet systems based on these domination/subordination dynamics endure, for reasons that are fairly simple to articulate:

+ Almost all of the systems and institutions in which we live are hierarchical.

+ Hierarchical systems and institutions deliver to those in a dominant class certain privileges, pleasures, and material benefits, and a limited number of people in a subordinated class are allowed access to those same rewards.

+ People are typically hesitant to give up privileges, pleasures, and benefits that make us feel good.

+ But those benefits clearly come at the expense of the vast majority of those in a subordinated class.

+ Given the widespread acceptance of basic notions about what it means to be a decent person, the existence of hierarchy has to be justified in some way other than crass self-interest.

One of the most common arguments for systems of domination and subordination is that they are “natural”—immutable, inevitable, just the way things are. Even if we don’t like things this way, we have no choice but to accept it. Oppressive systems work hard to make it appear that the hierarchies—and the disparities in wealth, status, and power that flow from them—are natural and beyond modification. If men are stronger in character with greater leadership ability than women, then patriarchy is inevitable and justifiable, even divinely commanded in some faith traditions. If the United States is the vehicle for extending modern democracy, then US domination of the world is inevitable and justifiable. If white people are smarter and more virtuous than people of color, then white supremacy is inevitable and justifiable. If rich people are smarter and harder working than poor people, then economic inequality is inevitable and justifiable.

All these claims require a denial of reality and an evasion of responsibility, and yet all these claims endure in the twenty-first century. The evidence presented for the natural dominance of some people is that those people are, on average, doing better and therefore must in some way be better. That works only if one believes that the wealth of the world should be distributed through a competitive system (a debatable point, if one takes those commitments to dignity, solidarity, and equality seriously) and that the existing “meritocracy” in which people compete is fair (a point that requires ignoring a tremendous amount of evidence about how the systems are rigged to perpetuate unearned privilege). This so-called evidence—that people who succeed in systems designed to advantage them are actually succeeding on their merit, which is proof they deserve it all—is one of the great shell games of history. That’s why it is crucial for unjust hierarchies to promote a belief in their naturalness; it’s essential to rationalizing the illegitimate authority exercised in them. Not surprisingly, people in a dominant class exercising that power gravitate easily to such a view. And because of their control over key storytelling institutions (especially education and mass communication), those in a dominant class can fashion a story about the world that leads some portion of the people in a subordinate class to internalize the ideology.

Instead of accepting this, we can evaluate these hierarchal systems and acknowledge that they are inconsistent with the foundational values most of us claim to hold.

SYSTEMS

People—you, me, our ancestors, and our progeny—have not been, are not, and will not always be kind, fair, generous, or agreeable. Human nature includes empathy and compassion, along with the capacity for greed and violence. Attention to how different social systems channel our widely variable species propensities is important. Because in all social systems people have been capable of doing bad things to others, we impose penalties on people who violate norms, whether through unwritten rules or formal laws. For most of human history prior to agriculture, in our gathering-and-hunting past, egalitarian values were the norm and band-level societies developed effective customs for maintaining those norms of cooperation and sharing. As societies grew in size and complexity, those customary methods became less effective, and hierarchies emerged and hardened.

To challenge the pathologies behind the routine violence, exploitation, and oppression that define the modern world, we have to understand how contemporary systems of power work to naturalize hierarchies. Listed in order from the oldest in human history to the most recent, the key systems are patriarchy, states and their imperial ambitions, white supremacy, and capitalism.

Patriarchy

Systems of institutionalized male dominance emerged several thousand years ago, after the beginning of agriculture, which changed so much in the world. Men turned the observable physiological differences between male and female—which had been the basis for different reproductive and social roles but generally with egalitarian norms—into a system of dominance, laying the foundation for the other hierarchical systems that would follow. Within families, men asserted control over women’s bodies, especially their sexual and reproductive capacities, and eventually extended male dominance over women in all of society.

As with any human practice, the specific forms such control take has varied depending on place and changed over time. Men’s exploitation of women continues today in rape, battering, and other forms of sexual coercion and harassment; the sexual-exploitation industries that sell objectified female bodies to men for sexual pleasure, including prostitution and pornography; denial of reproductive rights, including contraception and abortion; destructive beauty practices; and constraints on women’s economic and political opportunities. In some places, women remain feudal property of fathers and husbands. In other places, women are a commodity in capitalism who can be purchased by any man.

Some of these practices are legal and embraced by the culture. Some practices are illegal but socially condoned and rarely punished. Men along the political continuum, from reactionary right to radical left, engage in abusive and controlling behaviors that are either openly endorsed or quietly ignored. Feminist organizing projects have opened some paths to justice for some women, but success on one front can go forward while ground is lost elsewhere. After decades of organizing work, the anti-rape movement has raised awareness of men’s violence at the same time that the sexual-exploitation industries are more accepted than ever in the dominant culture.

No project for global justice in the twenty-first century is meaningful without a feminist challenge to patriarchy.

States and Imperialism

Around the same time that men’s domination of women was creating patriarchy, the ability of elites to store and control agricultural surpluses led to the formation of hierarchical states and then empires. Surplus-and-hierarchy predate agriculture in a few resource-rich places, but the domestication of plants and animals triggered the spread of hierarchy and a domination/subordination dynamic across the globe.

Historians debate why states emerged in the first place, but once such forms of political organization existed they became a primary vehicle for the concentration of wealth and conquest. States maintain their power by force and ideology, using violence and the threat of violence as well as propaganda and persuasion.

States have taken many different forms: the early empires of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China; the Greek city-states and Roman Republic-turned-Empire; Mesoamerican empires such as the Maya and Mexica/Aztec; feudal states; modern nation-states with various forms of governance; and today’s liberal democracies. Levels of wealth concentration and brutality, toward both domestic and foreign populations, have varied depending on place and changed over time. But even in contemporary democracies, the majority of the population has a limited role in decision-making. And some of the modern states that developed democratic institutions—including, but not limited to, Great Britain, France, and the United States—have been as brutal in imperial conquest as any ancient empire. European states’ world conquest over the past five hundred years, first accomplished through violence, continues in the form of economic domination in the postcolonial period. When imperial armies go home, private firms continue to exploit resources and labor, typically with local elites as collaborators.

In the first half of its existence, the United States focused on continental conquest to expand the land base of the country, resulting in the almost complete extermination of indigenous people. After that, US policymakers in the past century turned their attention to global expansion, achieving dominance in the post-World War II era.

Global justice in the twenty-first century requires acknowledging that the First World’s wealth is tied to the immiseration of the Third World. The power concentrated in states should be turned to undo the crimes of states.

White Supremacy

While human beings have always had notions of in-group and outsiders, we have not always categorized each other on the basis of what we today call race. The creation of modern notions of whiteness grew out of Europeans’ desire to justify the brutality of imperialism—conquest is easier when the people being conquered are seen as inferior. Racial categories later become central to the divide-and-conquer strategies that elites throughout history have used to control the majority of a population and maintain an unequal distribution of wealth and power.

In the early years of the British colonies in North America, rigid racial categories had not yet been created; there were no clear laws around slavery; and personal relationships and alliances between indentured servants and African slaves were not uncommon. When white workers began to demand better conditions, the planter elite’s solution was to increase the use of African slaves and separate them from poor European workers by giving whites a higher status with more opportunities, without disturbing the basic hierarchical distribution of wealth and power. This undermined alliances among the disenfranchised, leading white workers to identify more with wealthy whites while blacks were increasingly associated with the degradation inherent in slavery.

Not all white people are living in luxury, of course. But all other social factors being equal, non-white people face more hostile behaviors—from racist violence to being taken less seriously in a business meeting, from discrimination in hiring to subtle exclusion in social settings. While all people, including whites, experience unpleasant interactions with others, white people do not carry the burden of negative racial stereotypes into those interactions.

The limited benefits that elites bestowed on white workers have been referred to as “the wages of whiteness,” which is in large part psychological. White workers in this system get to think of themselves as superior to non-whites, especially black and indigenous people, no matter how impoverished they may be or how wide the gap between their lives and the lives of wealthy white people.

Although race is only one component of how wealth and power are distributed in hierarchical economies today, global justice is impossible without the end of white supremacy.

Capitalism

Patriarchy, imperialism, and white supremacy obviously are hierarchical systems, and it has become increasingly difficult for people to make moral arguments for them. But capitalism’s supporters assert that a so-called free-market system is the essence of freedom, allowing everyone to make uncoerced individual choices. That’s true, but only in textbooks and the fantasies of economists.

First, what is capitalism? Economists debate exactly what makes an economy capitalist, but in the real world we use it to identify a system in which (1) most property, including the capital assets necessary for production, is owned and controlled by private persons; (2) most people must rent themselves for money wages to survive; (3) the means of production and labor are manipulated by capitalists using amoral calculations to maximize profit; and (4) most exchanges of goods and services occur through markets. I did not say “free markets” because all markets in modern society are constructed through law (rules about contracts, currency, use of publicly funded infrastructure), which inevitably will advantage some and disadvantage others. Some disadvantages, such as living near manufacturing facilities that produce toxic waste, are what economists call “externalities,” the consequences of transactions that affect other people or ecosystems but aren’t reflected in the prices of goods or services. The term externality converts a moral outrage into the cost of doing business, borne mostly by poor people and non-human life.

“Industrial capitalism”—made possible by discoveries of new energy sources, sweeping technological changes, and concentrations of capital in empires such as Great Britain—was marked by the development of the factory system and greater labor specialization and exploitation. The term “finance capitalism” is used to mark a shift to a system in which the accumulation of profits in a financial system becomes dominant over the production processes. This financialization has led not only to intensified inequality but also to greater economic instability, most recently in the collapse of the housing market that sparked the financial crisis of 2007-08.

Today in the United States, most people understand capitalism through the experience of wage labor (renting oneself to an employer for money) and mass consumption (access to unprecedented levels of goods and services that are cheap enough to be affordable for ordinary people and not just elites). In such a world, everyone and everything is a commodity in the market.

This ideology of market fundamentalism is often referred to as “neoliberalism,” the new version of an economic definition of “liberal” from the nineteenth century that advocated minimal interference of government in markets. These fundamentalists assume that the most extensive use of markets possible, along with privatization of many publicly owned assets and the shrinking of public services, will unleash maximal competition and result in the greatest good—and that all this is inherently just, no matter what the results. If such a system creates a world in which most people live near or below the poverty line, that is taken not as evidence of a problem with market fundamentalism but evidence that fundamentalist principles have not been imposed with sufficient vigor. It is an article of faith that the “invisible hand” of the market always provides the preferred result, no matter how awful the consequences may be for large numbers of people and ecosystems.

Capitalism’s failures are easy to catalog: It is fundamentally inhuman (it not only allows but depends on the immiseration of a substantial portion of the world’s population to generate wealth), anti-democratic (the concentration of that wealth results in the concentration of power and undermines broad public participation), and unsustainable (the level of consumption threatens the stability of the ecosphere).

Capitalism is not the only unjust and unsustainable economic system in human history, of course. But global justice and ecological sustainability are impossible to imagine if we do not transcend capitalism and the fantasy of endless growth.

ECOLOGICAL BREAKS

The domination/subordination dynamic that is prevalent within the human family also defines the relationship between the human family and the larger living world today. That doesn’t mean that every person or every cultural tradition seeks to dominate and control the non-human world; there is considerable variation based on geography, history, and technological development. But today, virtually everyone—with varying levels of complicity, of course—is caught up in economic relationships that degrade ecosystems and undermine the ability of the ecosphere to sustain large-scale human life for much longer.

The idea that we humans, rather than the ecospheric forces, control the world emerged about ten thousand years ago at a key fault line in human history, the invention of agriculture, when soil erosion and degradation began the drawdown of the ecological capital of ecosystems beyond replacement levels. This destruction was intensified about five thousand years ago when people learned to smelt metals and started exhausting the carbon of forests in the Bronze and Iron ages. The Industrial Revolution and fossil fuels ramped up the assault on the larger living world, further intensified with the dramatic expansion of the petrochemical industries in the second half of the twentieth century. This history brings us to the brink of global ecological breakdown.

Today we face not only the longstanding problems of exhausted soils, but also chemical contamination of ecosystems and our own bodies; species extinction and loss of biodiversity; and potentially catastrophic climate disruption. Scientists warn that we have transgressed some planetary boundaries and are dangerously close to others, risking abrupt and potentially irreversible ecological change that could eliminate “a safe operating space for humanity.” All of these crises are a derivative of the overarching problem of overshoot, which occurs when a species uses biological resources beyond an ecosystem’s ability to regenerate and pollutes beyond an ecosystem’s capacity to absorb waste. The human species’ overshoot is not confined to specific ecosystems but is global, a threat at the planetary level.

How did we get here? Another look at human history is necessary to understand our predicament and the centrality of agriculture.

Like all organisms, gathering-and-hunting humans had to take from their environment to survive, but that taking was rarely so destructive that it undermined the stability of ecosystems or eliminated other species. Foraging humans were not angels—they were, after all, human like us, capable of being mean-spirited and violent. But they were limited in their destructive capacity by the amount of energy they could extract from ecosystems. Their existence did not depend on subordinating other humans or dominating the larger living world.

That changed with the domestication of plants and animals, especially annual grains such as wheat. Not all farming is equally destructive; differences in geography, climate, and environmental conditions have dictated different trajectories of development in different parts of the world. But the universal driver of this process is human-carbon nature: the quest for energy, the imperative of all life to seek out energy-rich carbon. Humans play that energy-seeking game armed with an expansive cognitive capacity and a species propensity to cooperate—that is, we are smart and know how to coordinate our activities to leverage our smarts. That makes humans dangerous, especially when we began to believe that we do not just live in the world but could own the world.

This deep history reminds us of the depth of our predicament. Capitalism is a problem but even if we replaced it with a more humane and democratic system, most people either are accustomed to a high-energy life or aspire to it. White supremacy is morally repugnant but achieving racial justice will not change people’s expectations for material comfort. The power of states, especially to extract wealth from other places, is dangerous, but constraining state power does not guarantee ecosphere stability. Transcending the foundational hierarchy of patriarchy, as liberating as that would be, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for social transformation.

Achieving greater levels of justice in the cultural, political, and economic arenas does not change the fact that the aggregate consumption of nearly eight billion people is unsustainable. In the past one hundred years, the population had doubled twice because of the dense energy of fossil fuels and the technology made possible by that energy. We will not be able to maintain this way of living much longer.

Today we know that continuing that fossil-fueled spending spree will lead to climate-change dystopias. Despite the fantasies of the technological fundamentalists, no combination of renewable energy sources can meet the material expectations of today’s human population. No advanced technology can change the laws of physics and chemistry. The future will be marked by a down-powering, either through rational planning or ecospheric forces that are more powerful than human desires. The slogan for a sustainable human future must be “fewer and less”: fewer people consuming far less energy and material resources.

I have no plan to achieve that result. No one else does either. No one has a plan that will make that transition easy or painless. There likely is no transition possible without disruption, dislocation, and death beyond our capacity to imagine. Our task is to continue trying without taking refuge in wishful thinking or succumbing to nihilism.

THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES: WHAT LIES AHEAD

The worldview I have outlined presents a consistent critique of not only the abuses of the powerful but the abusive nature of hierarchical systems. In a world built on hierarchies, there will never be permanent solutions to the injustice within the human family or to the unsustainable relationship between the human family and the larger living world.

This argues for a radical politics that is not afraid to articulate big goals and focus on long-term change. Not everyone with left/progressive politics will agree on every aspect of my analysis, nor is it possible to get widespread agreement on specific strategies for change—the left is full of contentious people who have substantive disagreements. However, people with radical politics usually agree on the depth of the changes needed over the long haul. But a long-term commitment to social and ecological transformation does not mean that today’s less ambitious political struggles are irrelevant. If a policy change that can be made today lessens human suffering or slightly reduces ecological destruction, that’s all to the good. Even better is when those small changes help set the stage for real transformation.

In some historical moments, the immediate threats to an existing democratic system that is flawed but functioning require special focus. A retrenchment of democracy would not only increase human suffering and ecological degradation but also make the longer and deeper struggles to change the system more difficult. The United States in 2022 faces such a threat.

My Political Life and Our Moment in History

In my political life as an adult, the two-party system in the United States has offered few attractive choices for the left. I reached voting age in 1976, about the time that the mainstream of the Democratic Party started shifting to the center/right and the mainstream of the Republican Party began moving from the center/right to more reactionary stances on most issues. The New Deal consensus that had defined post-World War II politics broke down, the radical energy of the 1960s dissipated, and left-wing critiques of economic policy were pushed to the margins.

But US society was changed for the better in many ways by that radical activism, most notably on issues of race, sex, and sexuality—civil rights, women’s rights, and lesbian/gay rights. Activists also won more breathing room to advocate for radical ideas free from most overt state repression. Many progressive people and ideas found their way into higher education and media institutions, even if the power structures in government and the economy didn’t change much. But that didn’t stop the ascendancy of neoliberalism, marked by the election of Margaret Thatcher as UK prime minister in 1979 and Ronald Reagan as US president in 1980.

When I became politically active in the 1990s, radical organizing focused on those power structures and hierarchical systems. We saw our work as not only fighting right-wing reactionary policies championed by the Republican Party but also challenging the moderates who controlled the Democratic Party. The epitome of that corporate-friendly politics was the 1996 presidential race, pitting Bill Clinton against Bob Dole, an election in which it was easy to understand why so many on the left claimed there wasn’t “a dime’s worth of difference” between the two candidates. (We always should be careful, however, given the parties’ different positions on rights for people of color, women, and lesbians and gay men, and also because that phrase came in the 1968 presidential campaign of former Alabama Governor George Wallace, hardly a progressive.)

In our organizing, we had no illusions that a radical politics would catch fire immediately, but the patient work of articulating a radical agenda and organizing people outside the electoral system seemed sensible. I continued to vote in every election, but like many on the left I was fond of an Emma Goldman quote (sometimes attributed to Mark Twain): “If voting changed anything, they’d make it illegal.”

Today, the assault on representative democracy from the right may leave us with voting that is legal but irrelevant in what is now called an “illiberal democracy.” No matter what the limits of our attenuated democratic system, its de facto death at the hands of authoritarianism would be a disaster.

Solidarity against the Right

The political terrain is in some ways unchanged—the dominant forces in the United States remain committed to capitalism and US domination of the global economy. But democratic socialist electoral and organizing successes in the past decade have created new opportunities within the Democratic Party, demonstrated most visibly by the unexpected strength of Bernie Sanders in the presidential primaries in 2016 and 2020, and the election to the US House of Representatives of the “squad” of progressive women of color. Building popular movements together with electoral campaigns has demonstrated that the left can press the moderate leadership of the Democratic Party from the outside and inside.

But in that same period, a new threat has emerged: the erosion of the central norms of liberal democracy from a right-wing populist movement that found a charismatic authoritarian leader in Donald Trump. Whatever the limits of liberal democracy in capitalism, that system provides the foundation from which radical political activity can go forward. This new threat is serious, and unprecedented in my lifetime.

The two democratic norms most unstable at the moment are the peaceful transfer of power based on acceptance of results from open, competitive elections; and rational political engagement based on shared intellectual principles about truth-seeking. A significant segment of the Republican Party, including many of the most visible party leaders, have abandoned the core principle of democracy and the core principle of modern intellectual life that makes democracy possible.

None of this suggests there was a mythical golden age of US politics when the democratic system produced deep democracy. The John Birch Society and Ku Klux Klan were authentic manifestations of US culture, just as labor organizing and the civil rights movement were. Concentrations of wealth have always distorted democracy, and hierarchies have always intentionally marginalized some people. But a political system based on a peaceful transfer of power after rational engagement—no matter how imperfectly it may work at times—is better than a political system that abandons those principles.

Today, a functional two-party system no longer exists. Whatever the failures of the Democratic Party to deliver on rhetoric about freedom and justice, it remains committed to those democratic and intellectual principles. The Republican Party of today is a rogue operation, openly thuggish and ready to abandon minimal democratic protocols after abandoning minimal intellectual standards. A majority of Republicans believe that the 2020 presidential election was stolen from Trump without being able to produce any credible evidence, and a majority are likely to make the same claim if the 2024 presidential election is won by a Democrat. Almost all Republican politicians either endorse these positions or are afraid to challenge them in public for fear of alienating a significant number of core Republican voters.

Where will this lead? The direst warnings suggest a coming civil war. The best-case scenario is years of struggle over power that bring simmering social and ecological crises to full boil. I am not in the prediction business and do not know if the worst can be averted. But for now, a practical radical politics should put aside ideological differences with the moderate wing of the Democratic Party and do whatever is necessary to repel the threat to liberal democracy from the Republican Party. The difference between the two parties can no longer be measured in dimes and is now about decibels: The destructive rhetoric of the anti-democratic forces on the right is threatening to drown out any possibility of rational engagement, endangering the peaceful transfer of power in future elections.

Some on the left will counter with “the lesser of two evils is still evil.” This is a dangerous sentiment for two reasons. First, is it accurate to cast political opponents as evil? I strongly support national health insurance to provide the same basic care for everyone. Are people who reject that policy evil? I strongly opposed the US invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. Are people who supported those military actions evil? We need not settle on a single definition of what constitutes evil—philosophers and theologians have been fussing with that for millennia—to agree that the term is unhelpful in parsing most contemporary policy debates. Second, what if there were a case in which competing political forces both deserved the term evil but there was a meaningful distinction in the intensity of the evil, and the distinction meant saving lives. Wouldn’t we want to side with the lesser? Hypotheticals are of little value, given the complexity of such decisions in the real world. But to suggest that it is morally superior to never make such calculations is simplistic and irresponsible.

A practical radical politics requires collaboration with forces that can challenge the intensified reactionary politics of the Republican Party while we pursue projects to expand and deepen social justice. One organizer has called for a “block and build” strategy—block the white nationalists, theocrats, and corporate oligarchs, while building practices that support multiracial democracy in all our projects.

Debate within the Left

As we participate in a united front against authoritarianism, minimizing for the time being the serious disagreements with mainstream Democrats and rational Republicans, we should reflect on the intellectual traps in which the left finds itself ensnared. On social justice, there is not enough critical self-reflection. On ecological sustainability, there is too much magical thinking.

I don’t want to get bogged down in the debate over “cancel culture,” the banishment or shunning of anyone who breaks from a group’s doctrine. The term has been so successfully commandeered by the right-wing that it has become an impediment to productive conversation. Simply proclaiming a commitment to freedom of expression doesn’t resolve the problem, since there is no simple, obvious analysis of that freedom that can easily resolve policy disputes. “It’s complicated” may be a cliché, but it applies here.

For purposes of this essay, I will offer what should not be controversial: On matters that are long settled in both moral and scientific realms, such as the equality of racial groups, the left need not spend time on debate. On matters that are not settled in either realm, such as the definition and etiology of transgenderism, respectful debate should be encouraged. And on matters of public policy—how we can best ensure dignity, solidarity, and equality—any reasonable proposal offered in good faith should get a hearing.

After three decades of participation in a variety of left and feminist movements, I would also highlight the need to guard against expressions of intellectual superiority and assumptions of moral superiority. I offer this with painful awareness of my own failings in the past, and with a pledge to work toward greater humility. This is crucial for two reasons. The principled reason is simply that everyone can be wrong, has been wrong, and will be wrong again sometime. Adopting a posture of certainty ignores our capacity for failure. The practical reason is that no one likes arrogant people who think they are always right and always better than everyone else. Haughty and smug people make ineffective political organizers, which I know from my own failures.

I am not arguing that people on the left are uniquely subject to these traps, but rather that people on the left are people and, like everyone, capable of haughtiness and smugness. This is of particular concern on college campuses, one of the sites where the left is strongest. In thirty years of work in universities, I saw how intellectual and moral posturing on the left undermined a healthy intellectual culture and drove away those well-intentioned centrist and conservative people who were willing to debate in good faith but did not want to be hectored.

Leftists tend to think of themselves as critically minded, and so this call for greater critical self-reflection and humility will no doubt bristle. So will the suggestion that the left’s ecological program is based on magical thinking. But the major progressive environmental proposal, the Green New Deal, shows that the left is prone to reality-denial on ecological matters and can get caught up in technological fundamentalism. That faith-based embrace of the idea that the use of evermore advanced technology is always a good thing—even to solve the problems caused by the unintended consequences of previous advanced technology—is perhaps the most dangerous fundamentalism in the world today.

Human-carbon nature makes it difficult to move toward a dramatically lower population with dramatically less consumption; it’s easy to understand why a call for limits isn’t popular. But rather than talk about the need for “fewer and less,” most of the left places the ecological crises exclusively at capitalism’s door. The Green New Deal and similar proposals seem to assume that once the corporations profiting from exploitation are tamed or eliminated, a more democratic distribution of political power will lead to the renewable technologies that will allow high-energy lifestyles to continue. This illusion shows up in the promotional video “A Message from the Future” that features U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a leading progressive voice in Congress. This seven-and-a-half minute video elegantly combines political analysis with engaging storytelling and beautiful visuals to make a case for the Green New Deal. But one sentence reveals the fatal flaw of the analysis: “We knew that we needed to save the planet and that we had all the technology to do it [in 2019].” First, talk of saving the planet is misguided. As many have pointed out in response to such rhetoric, the Earth will continue with or without humans. Charitably, we can interpret that phrase to mean “reducing the damage that humans do to the ecosphere and creating a livable future for humans.”

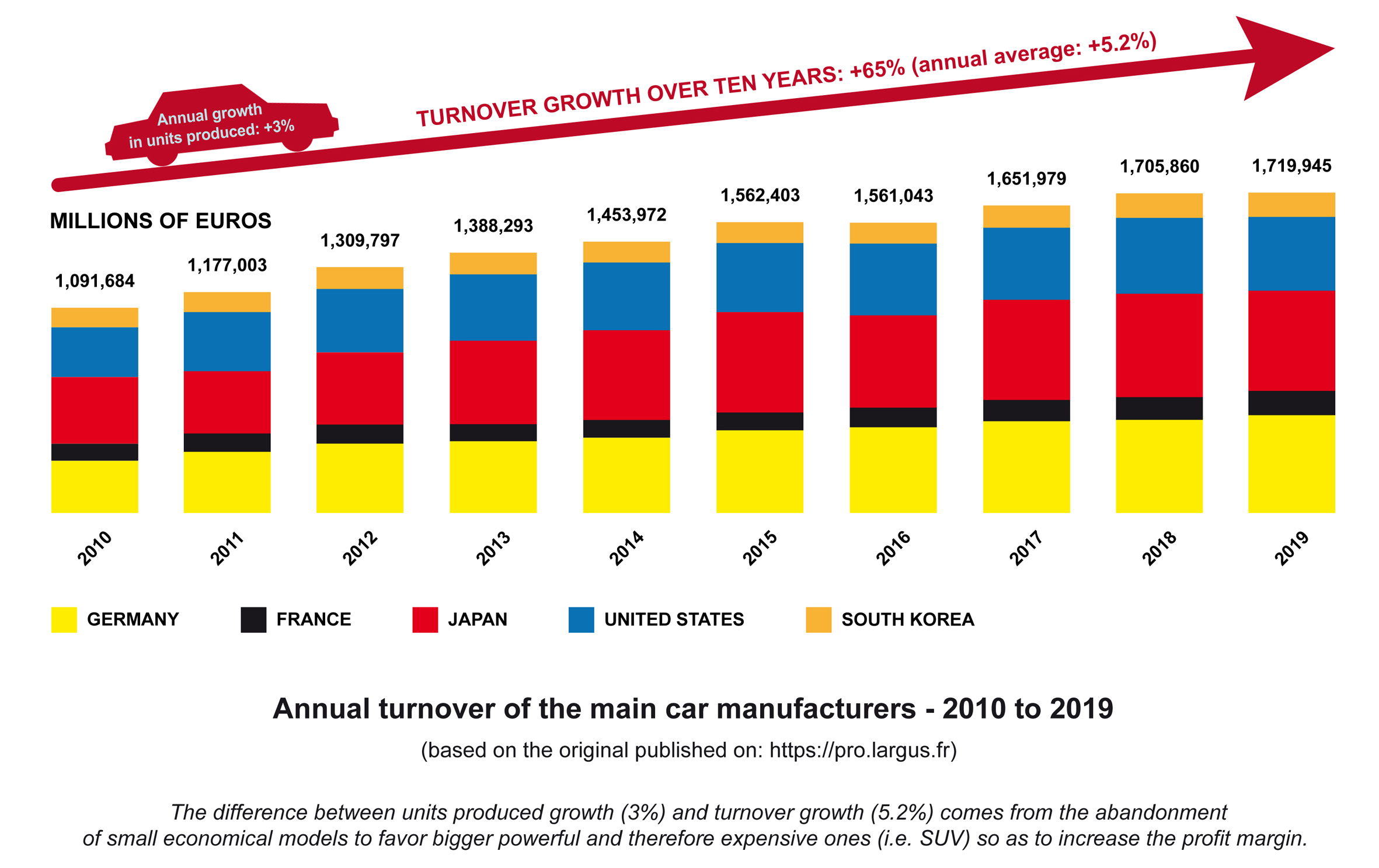

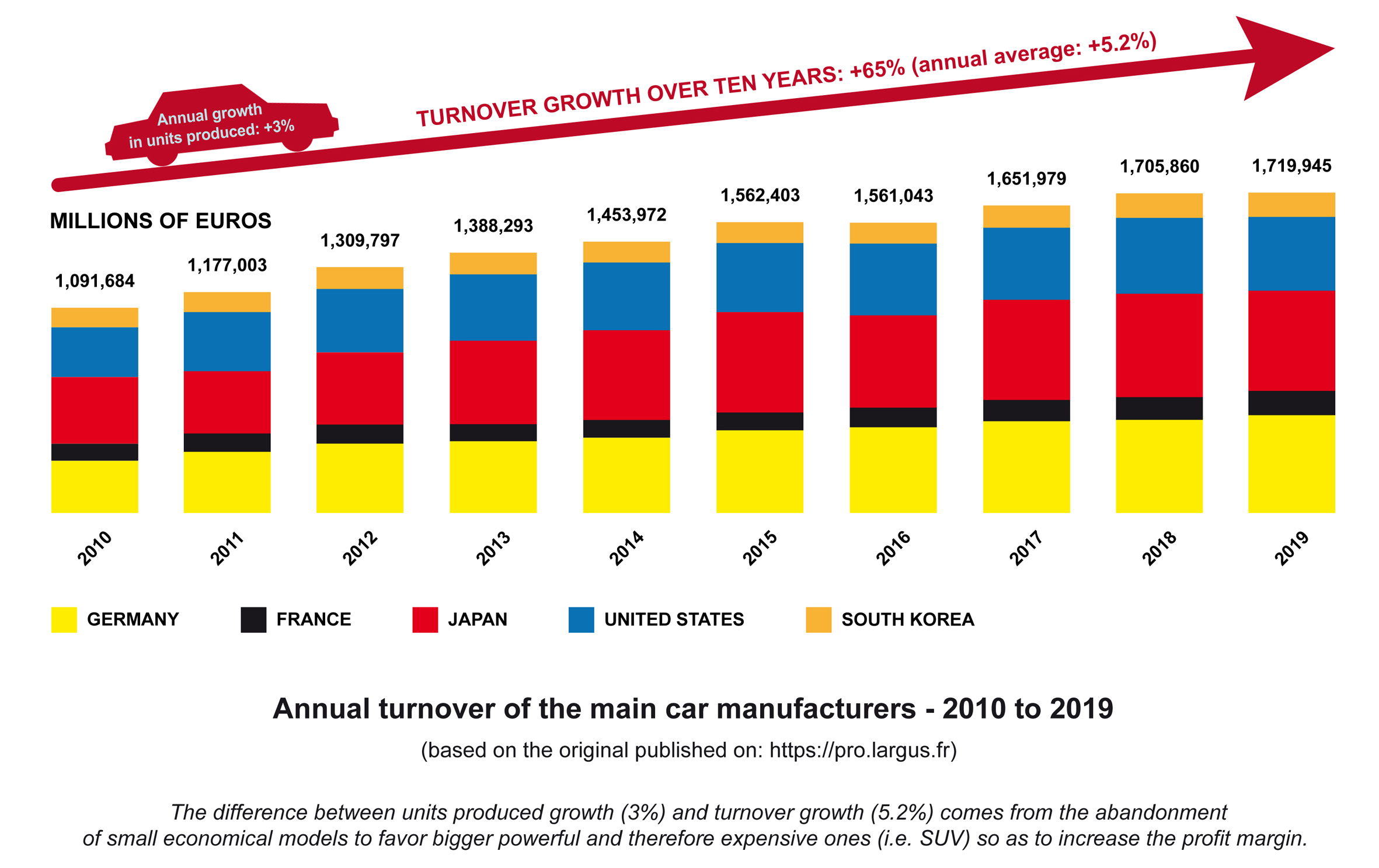

The problem is that we don’t have all the technology to do that, and if we insist that better gadgets can accomplish that we will fail. Overly optimistic assessments of renewable energy and energy-saving technologies promote the false hope that we have the means to maintain existing living arrangements. The problem is not just that the concentration of wealth leads to so much wasteful consumption and so many wasted resources, but that the infrastructure of our world was built by the dense energy of fossil fuels that renewables cannot replace. Without that dense energy, a smaller human population is going to live in dramatically different fashion. The Green New Deal would be a step toward ecological sustainability if it included a call to take population reduction seriously along with a commitment to lowering consumption. Neither is part of the standard progressive pitch. For example, instead of advocating the end of car culture and a dramatic reduction in travel overall, progressives typically double down on electric cars, largely ignoring the destructive ecological costs of mining and production required for such vehicles and their batteries.

Reactionary and right-wing political movements defend current systems and peddle the illusion that no change is needed in how we live. Centrist and moderate political movements peddle the illusion that a kinder-and-gentler capitalism will keep modern society afloat. Progressive and left political movements peddle the illusion that a democratic socialist system will suddenly make an unsustainable level of consumption sustainable. Those on the left who reject the business-as-usual pseudo-solutions of the right and center are themselves embracing a version of business-pretty-much-as-usual that would slow the mad rush to collapse but does not set us on a new course.

ANGUISH

In this essay I have tried to be analytical, evaluating evidence and presenting my assessments to others, who can use the same intellectual tools to reach their own conclusions. But we humans are more than rational calculating machines, of course. Our capacity for reason can guide our actions, but we all are driven by emotion, passion, and the non-rational aspects of our psychology.

One of those very human emotions is fear. Franklin D. Roosevelt is remembered for taking on fear in his first inaugural address in 1933: “[L]et me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

Whatever the value of that stirring rhetoric to a nation stuck in the Great Depression in 1933, many of the fears of today are not nameless, unreasoning, or unjustified. While the threats we face in the economic and political arenas are not new in human history, the ecological crises are unprecedented in scale and scope, and heightened fear is appropriate. We are not facing discrete environmental problems that have solutions but rather multiple cascading ecological crises that have no solutions, if we demand solutions that allow us to maintain existing living arrangements. Prediction is a fool’s game, but even more foolish is to pretend that economic growth and the existing world population can continue indefinitely.

We should encourage people to be honest about these easy-to-name, reasonable, and justified fears that produce real anguish for many of us. It’s increasingly common for people to speak of grief in the face of such immense human suffering and ecospheric destruction, but I think the term anguish better captures the range of emotions—distress, dread, depression—and the degree of psychological pain and anxiety that comes with those feelings.

To update FDR: The main thing we have to fear is our fear of naming reasonable and justified fears. When people feel that anguish, it is counterproductive to tell them to ignore it. Asking people to deny what they know to be true and to suppress the emotions generated by that knowledge is a losing game. “Don’t worry, be happy” makes for a catchy song but a lousy approach to politics.

There’s no algorithm that can tell us when the structural trends that create these unjust and unstable conditions will result in the kind of dramatic changes that warrant the term collapse. Triggering events are unpredictable; the speed with which systems collapse will vary; and the suffering will not be spread evenly or equitably around the world. But when that process intensifies, we can expect a loss of social resilience, the capacity of a society to cooperate effectively to achieve shared goals. In the past, there also have been benefits when hierarchical and ecologically destructive societies collapsed—many people on the bottom of a society may live freer without those hierarchies, and the larger living world has more options for regenerating when human overshoot is finally checked. But today it’s hard to imagine anyone committed to dignity, solidarity, and equality applauding collapse. Still, collapse appears inevitable. But how we react to those changes is not set in stone. Whatever the future holds and wherever one sits in the social hierarchies, fear of what is coming makes sense—intellectually and emotionally. That fear is based on a rational assessment of reality and an awareness of the role of emotion in our lives. Given the magnitude of the threats, it’s not surprising that many people turn away. But to be fully alive today is to face those fears and live with anguish, not for one’s own condition in the world but for the condition of all of humanity and the larger living world, for a world that in some places is in collapse and is everywhere else on the brink.

A practical approach to decisions we must make today, informed by radical analyses that help us understand the potential for tomorrow, will not magically allay our fears or alleviate our anguish. No honest account of the world can do that. James Baldwin offered good advice about dealing with terror: “If you’ve got any sense, you realize you’d better not run. Ain’t no place to run. So, you walk toward it. At least that way you’ll know what hit you.” Our task is not to run from our fears but embrace them, not to ignore our anguish but share it with others.

Robert Jensen is an emeritus professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin and a founding board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center. He collaborates with New Perennials Publishing and the New Perennials Project at Middlebury College.

Jensen is the co-author, with Wes Jackson, of An Inconvenient Apocalypse: Environmental Collapse, Climate Crisis, and the Fate of Humanity, which will be published in September 2022 by the University of Notre Dame Press. He is also the host of “Podcast from the Prairie” with Jackson.

Jensen is the author of The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson: Searching for Sustainability (University Press of Kansas, 2021); The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men (2017); Plain Radical: Living, Loving, and Learning to Leave the Planet Gracefully (2015); Arguing for Our Lives: A User’s Guide to Constructive Dialogue (2013); All My Bones Shake: Seeking a Progressive Path to the Prophetic Voice, (2009); Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity (2007); The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege (2005); Citizens of the Empire: The Struggle to Claim Our Humanity (2004); and Writing Dissent: Taking Radical Ideas from the Margins to the Mainstream (2001).

Jensen can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu. To join an email list to receive articles by Jensen, go to http://www.thirdcoastactivist.org/jensenupdates-info.html. Follow him on Twitter: @jensenrobertw

Originally published in Counterpunch.

Photo by Tania Malréchauffé on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Feb 5, 2022 | ANALYSIS, Reclamation & Expropriation

Editor’s note: This piece details the history of the enclosure movement, focusing on western civilization. Enclosure is an ongoing process by which land that was previously seen as collective, belonging to everyone or purely to nature, is privatized. Enclosure has long been a tenet of capitalism, and more broadly of civilization. Exploitation and destruction of land follows.

by Ian Angus

In 1542, Henry VIII gave his friend and privy councilor Sir William Herbert a gift: the buildings and lands of a dissolved monastery, Wilton Abbey near Salisbury. Herbert didn’t need farmland, so he had the buildings torn down, expelled the monastery’s tenants, and physically destroyed an entire village. In their place he built a large mansion, and fenced off the surrounding lands as a private park for hunting.

In May 1549, officials reported that people who had long used that land as common pasture were tearing down Herbert’s fences.

“There is a great number of the commons up about Salisbury in Wiltshire, and they have plucked down Sir William Herbert’s park that is about his new house, and diverse other parks and commons that be enclosed in that county, but harm they do to [nobody]. They say they will obey the King’s master and my lord Protector with all the counsel, but they say they will not have their commons and their grounds to be enclosed and so taken from them.”

Herbert responded by organizing an armed gang of 200 men, “who by his order attacked the commons and slaughtered them like wolves among sheep.”[1]

The attack on Wilton Abbey was one of many enclosure riots in the late 1540s that culminated in the mass uprising known as Kett’s Rebellion, discussed in Part Two. There had been peasant rebellions in England in the Middle Ages, most notably in 1381, but they were rare. As Engels wrote of the German peasantry, their conditions of life militated against rebellion. “They were scattered over large areas, and this made every agreement between them extremely difficult; the old habit of submission inherited by generation from generation, lack of practice In the use of arms in many regions, and the varying degree of exploitation depending on the personality of the lord, all combined to keep the peasant quiet.”[2]

Enclosure, a direct assault on the peasants’ centuries-old way of life, upset the old habit of submission. Protests against enclosure were reported as early as 1480, and became frequent after 1530. “Hundreds of riots protesting enclosures of commons and wastes, drainage of fens and disafforestation … reverberated across the century or so between 1530 and 1640.”[3]

Elizabethan authorities used the word “riot” for any public protest, and the label is often misleading. Most were actually disciplined community actions to prevent or reverse enclosure, often by pulling down fences or uprooting the hawthorn hedges that landlords planted to separate enclosed land.

“The point in breaking hedges was to allow cattle to graze on the land, but by filling in the ditches and digging up roots those involved in enclosure protest made it difficult and costly for enclosers to re-enclose quickly. That hedges were not only dug up but also burnt and buried draws attention to both the considerable time and effort which was invested in hedge-breaking and to the symbolic or ritualistic aspects of enclosure opposition. … Other forms of direct action against enclosure included impounding or rescuing livestock, the continued gathering of previously common resources such as firewood, trespassing in parks and warrens, and even ploughing up land which had been converted to pasture or warrens.”[4]

The forms of anti-enclosure action varied, from midnight raids to public confrontations “with the participants, often including a high proportion of women, marching to drums, singing, parading or burning effigies of their enemies, and celebrating with cakes and ale.”[5] (I’m reminded of Lenin’s description of revolutions as festivals of the oppressed and exploited.) Villagers were very aware of their rights — it was joked that some farmers read Thomas de Lyttleton’s Treatise on Tenures while ploughing — so physical assaults on fences and hedges were often accompanied by petitions and legal action.

Many accounts of what’s called the enclosure movement focus on the consolidation of dispersed strips of leased land into compact farms, but most enclosure riots actually targeted the privatization of the unallocated land that provided pasture, wood, peat, game and more. For cottagers who had no more than a small house and an acre or two of poor quality land, access to those resources was a matter of life and death. “Commons and common rights, so far from being merely a luxury or a convenience, were really an integral and indispensable part of the system of agriculture, a lynch pin, the removal of which brought the whole structure of village society tumbling down.”[6]

Coal wars

In the last decades of the 1500s, farmers in northern England faced a new threat to their livelihoods, the rapid expansion of coal mining, which many landlords found was more profitable than renting farmland. Thousands who were made landless by enclosure ultimately found work in the new mines, but the very creation of those mines required the dispossession of farmers and farmworkers. The search for coal seams left pits and waste that endangered livestock; actual mines destroyed pasture and arable land and polluted streams, making farming impossible.

The prospect of mining profits produced a new kind of enclosure — expropriation of mineral rights under common land. “Wherever coal-mining became important, it stimulated the movement towards curtailing the rights of customary tenants and even of small freeholders, and towards the enclosure of portions of the wastes.” In the landlords’ view, it wasn’t enough just to fence off the mining area, “not only must the tenants be prevented from digging themselves, they must be stripped of their power to refuse access to minerals under their holdings, or to demand excessive compensation.”[7]

As a result, historian John Nef writes, tenant farmers “lived in constant fear of the discovery of coal under their land,” and attempts to establish new mines were often met by sabotage and violence. “Many were the obscure battles fought with pitchfork against pick and shovel to prevent what all tenants united in branding as a mighty abuse.” Fences were torn down, pits filled in, buildings burned, and coal was carried off. In Lancashire, the enclosures surrounding one large mine were torn down sixteen times by freeholders who claimed “freedom of pasture.” In Derbyshire in 1606, a landlord complained that twenty-three men “armed with pitchforks, bows and arrows, guns and other weapons,” had threatened to kill everyone involved if mining continued on the manor.[8]

In these and many other battles, commoners heroically fought to preserve their land and rights, but they were unable to stop the growth of a highly-profitable industry that was supported physically by the state and legally by the courts. As elsewhere, capital defeated the commons.

Turning point

In the early 1500s, capitalist agriculture was new, and the landowning classes were generally critical of the minority who enclosed common land and evicted tenants. The commonwealth men whose sermons defended traditional village society and condemned enclosure were expressing, in somewhat exaggerated form, views that were widely held in the aristocracy and gentry. While anti-enclosure laws were drafted and introduced by the royal government, they were invariably approved by the House of Commons, which “almost by definition, represented the prospering section of the gentry.”[9]

As the century progressed, however, growing numbers of landowners sought to break free from customary and state restrictions in order to “improve” their holdings. In 1601, when Sir Walter Raleigh argued that the government should “let every man use his ground to that which it is most fit for, and therein use his own discretion,”[10] a large minority in the House of Commons agreed.

As Christopher Hill writes, “we can trace the triumph of capitalism in agriculture by following the Commons’ attitude towards enclosure.”

“The famine year 1597 saw the last acts against depopulation; 1608 the first (limited) pro-enclosure act. … In 1621, in the depths of the depression, came the first general enclosure bill — opposed by some M.P.s who feared agrarian disturbances. In 1624 the statutes against enclosure were repealed. … the Long Parliament was a turning point. No government after 1640 seriously tried either to prevent enclosures, or even to make money by fining enclosers.”[11]

The early Stuart kings — James I (1603-1625) and Charles I (1625-1649) — played a contradictory role, reflecting their position as feudal monarchs in an increasingly capitalist country. They revived feudal taxes and prosecuted enclosing landlords in the name of preventing depopulation, but at the same time they raised their tenants’ rents and initiated large enclosure projects that dispossessed thousands of commoners.

Enclosure accelerated in the first half of the 1600s — to cite just three examples, 40% of Leicestershire manors, 18% of Durham’s land area, and 90% of the Welsh lowlands were enclosed in those decades.[12] Even without formal enclosure, many small farmers lost their farms because they couldn’t pay fast rising rents. “Rent rolls on estate after estate doubled, trebled, and quadrupled in a matter of decades,” contributing to “a massive redistribution of income in favour of the landed class.”

It was a golden age for landowners, but for small farmers and cottagers, “the third, fourth, and fifth decades of the seventeenth century witnessed extreme hardship in England, and were probably among the most terrible years through which the country has ever passed.[13]

Fighting back

Increased enclosure was met by increased resistance. Seventeenth century enclosure riots were generally larger, more frequent, and more organized than in previous years. Most were local and lasted only a few days, but several were large enough to be considered regional uprisings — “the result of social and economic grievances of such intensity that they took expression in violent outbreaks of what can only be called class hatred for the wealthy.”[14]

The Midland Revolt broke out in April 1607 and continued into June. The rebels described themselves as “diggers” and “levelers,” labels later used by radicals during the civil war, and they claimed to be led by “Captain Pouch,” a probably mythical figure whose magical powers would protect them.[15] Martin Empson describes the revolt in his history of rural class struggle, Kill all the Gentlemen:

“Events in 1607 involved thousands of peasants beginning in Northamptonshire at the very start of May and spreading to Warwickshire and Leicestershire. Mass protests took place, involving 3,000 at Hilmorton in Warwickshire and 5,000 at Cotesback in Leicestershire. In a declaration produced during the revolt, The Diggers of Warwickshire to all other Diggers, the authors write that they would prefer to ‘manfully die, then hereafter to be pined to death for want of that which those devouring, encroachers do serve their fat hogs and sheep withal.’”[16]

These were well-planned actions, not spontaneous riots. Cottagers from multiple villages met in advance to discuss where and when to assemble, arranged transportation, and provided tools, meals and places to sleep for the rebels who would spend days tearing down fences, uprooting hedges and filling in ditches. Local militias could not stop them — indeed, “many members of the militia themselves became involved in the rising, either actively or by voting with their feet and failing to attend the muster.”[17]

The movement was only stopped when mounted vigilantes, hired by local landlords, attacked protestors near the town of Newton, massacring more than 50 and injuring many more. The supposed leaders of the rising were publicly hanged and quartered, and their bodies were displayed in towns throughout the region.

The Western Rising was less organized, but it lasted much longer, from 1626 to 1632. Here the focus was “disafforestation” — Charles I’s privatization of the extensive royal forests in which thousands of farmers and cottagers had long exercised common rights. The government appointed commissions to survey the land, propose how to divide it up, and negotiate compensation for tenants. The largest portions were leased to investors, mainly the king’s friends and supporters, who in turn rented enclosed parcels to large farmers.”[18]

Generally speaking, the forest enclosures seem to have been fair to freeholders and copyholders who could prove that they had common rights, but not to those who had never had formal leases, or couldn’t prove that they had. The formally landless were excluded from the negotiations and from the land they had worked on all their lives.

For at least six years, landless workers and cottagers fought to prevent or reverse enclosures in Dorset, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, and other areas where the crown was selling off public forests.

“The response of the inhabitants of each forest was to riot almost as soon as the post-disafforestation enclosure had begun. These riots were broadly similar in aim and character, directed toward the restoration of the open forest and involving destruction of the enclosing hedges, ditches, and fences and, in a few cases, pulling down houses inhabited by the agents of the enclosers, and assaults on their workmen.”[19]

Declaring “here were we born and here we will die,” as many as 3,000 men and women took part in each action against forest enclosures. Buchanan Sharp’s study of court records shows that the majority of those arrested for anti-enclosure rioting identified themselves not as husbandmen (farmers) but as artisans, particularly weavers and other clothworkers, who depended on the commons to supplement their wages. “It could be argued that there were two types of forest inhabitants, those with land who went to law to protect their rights, and those with little or no land who rioted to protect their interests.”[20]

The longest continuing fight against enclosure took place in eastern England, in the fens. From the 1620s to the end to the century, thousands of farmers and cottagers resisted large-scale projects to drain and enclose the vast wetlands that covered over 1400 square miles in Lincolnshire and adjacent counties. Aiming to create “new land” that could be sold to investors and rented to large tenant farmers, the drainage projects would dispossess thousands of peasants whose lives depended on the region’s rich natural resources.

The result was almost constant conflict. Historian James Boyce describes what happened in 1632, when constables tried to arrest opponents of draining a 10,000 acre common marsh, in the Cambridgeshire village of Soham:

“The constables charged with arresting the four Soham resistance leaders so delayed entering the village that they were later charged for not putting the warrant into effect. When they finally sought to do so, an estimated 200 people poured onto the streets armed with forks, staves and stones. The next day a justice ordered 60 men to support the constables in executing the warrant but over 100 townspeople still stood defiant, warning ‘that if any laid hands of any of them, they would kill or be killed’. When one of the four was finally arrested, the constables were attacked and several people were injured. A justice arrived in Soham on 11 June with about 120 men and made a further arrest before the justice’s men were again ‘beaten off, the rest never offering to aid them’. Another of the four leaders, Anne Dobbs, was eventually caught and imprisoned in Cambridge Castle but on 14 June 1633, the fight was resumed when about 70 people filled in six division ditches meant to form part of an enclosure. Twenty offenders were identified, of whom fourteen were women.”[21]

Militant and often violent protests challenged every drainage project. As elsewhere in England, fenland rioters uprooted hedges, filled ditches and destroyed fences, but here they also destroyed pumping equipment, broke open dykes, and attacked drainage workers, many of whom had been brought from the Netherlands. “By the time of the civil war the whole fenland was in a state of open rebellion.”[22]

Revolution in the revolution

For eleven years, from 1629 to 1640, Charles I tried to rule as an absolute monarch, refusing to call Parliament and unilaterally imposing taxes that were widely viewed as oppressive and illegal. When his need for more money finally forced him to call Parliament, the House of Commons refused to approve new taxes unless he agreed to restrictions on his powers. The king refused and civil war broke out in 1642, leading to Charles’s defeat and execution in 1649. From then until 1660, England was a republic.

Many histories of the civil was treat it as purely a conflict within the ruling elite: it often seems, Brian Manning writes, “as if the other 97 per cent of the population did not exist or did not matter.”[23] In fact, as Manning shows in The English People and the English Revolution, poor peasants, wage laborers and small producers were not just followers and foot soldiers — they were conscious participants whose actions influenced and often determined the course of events. The fight for the commons was an important part of the English Revolution.

“Between the assembling of the Long Parliament in·1640 and the outbreak of the civil war in 1642 there was a rising tide of protest and riot in the countryside. This was directed chiefly against the enclosures of commons, wastes and fens, and the invasions of common rights by the king, members of the royal family, courtiers, bishops and great aristocrats.”[24]

Between 1640 and 1644 there were anti-enclosure riots in more than half of England’s counties, especially in the midlands and north: “in some cases not only the fences but the houses of the gentry were attacked.”[25]

The wealthiest landowners were outraged. In July 1641, the House of Lords complained that “violent breaking into Possessions and Inclosures, in riotous and tumultuous Manner, in several Parts of this Kingdom,” was happening “more frequently … since this Parliament began than formerly.” They ordered local authorities to ensure “that no Inclosure or Possession shall be violently, and in a tumultuous Manner, disturbed or taken away from any Man,”[26] but their orders had little effect. “Constables not only repeatedly failed to perform their duties against neighbours engaged in the forcible recovery of their commons, but were also sometimes to be found in the ranks of the rioters themselves.”[27]

The rioters hated the landowners’ government and weren’t reluctant to say so. When an order against anti-enclosure riots was read in a church in Wiltshire in April 1643, for example, one parishioner stood and “most contemptuously and in dishonor of the Parliament and their authority said that he cared not for their orders and the Parliament might have kept them and wiped their arses with them.”[28]

In 1645, anti-enclosure protestors in Epworth, Lincolnshire, replied to a similar order that ‘”They did not care a Fart for the Order which was made by the Lords in Parliament and published in the Churches, and, that notwithstanding that Order, they would pull down all the rest of the Houses in the Level that were built upon those Improvements which were drained, and destroy all the Enclosures.”[29]

The most intense conflicts took place in the fens. To cite just one case, in February 1643, in Axholme, Lincolnshire, commoners armed with muskets opened floodgates at high tide, drowning over six thousand acres of recently drained and enclosed land, and then closed the gates to prevent the water from flowing out at low tide. Armed guards then held the position for ten weeks, threatening to shoot anyone who attempted to let the water out.[30]

Many more examples could be cited. The years 1640 to 1660 weren’t just a time of revolutionary civil war, they were decades of anti-enclosure rebellion.

Defeat

Two centuries later, in The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote that “all previous historical movements were movements of minorities, or in the interests of minorities.” That was certainly true of the English Revolution — Parliament could not have overthrown the monarchy without the support of small producers, peasants and wage-workers, but the plebeians got little from the victory. As Digger leader Gerard Winstanley wrote to the “powers of England” in 1649: “though thou hast promised to make this people a free people, yet thou hast so handled the matter, through thy self-seeking humour, that thou has wrapped us up more in bondage, and oppression lies heavier upon us.”[31]

Since the king was one of the largest and most hated enclosers, many anti-enclosure protesters expected Parliament to support their cause, but their hopes were disappointed — no surprise, since almost all MPs were substantial landowners. Both houses of Parliament repeatedly condemned anti-enclosure riots, and no anti-enclosure measures were adopted during the civil war or by the republican regime in the 1650s. The last attempt to regulate (not prevent) enclosure occurred in 1656, when a Bill to do that was rejected on first reading: the Speaker said “he never liked any Bill that touched upon property,” and another MP called it “the most mischievous Bill that ever was offered to this House.”[32]

Like the royal government it replaced, the republican government in the 1650s raised revenue by selling off royal forests and supported the drainage and enclosure of the fens. It passed laws that eliminated all remaining feudal restrictions and charges on landowners, but made no changes to the tenures of farmers and cottagers. “Thus landlords secured their own estates in absolute ownership, and ensured that copyholders remained evictable.”[33]

In Christopher Hill’s words, in the seventeenth century struggle for land, “the common people were defeated no less decisively than the crown.”[34]

The last wave

There were sporadic anti-enclosure protests in the last years of the seventeenth century, especially in the fens, but for all practical purposes, the uprisings of 1640 to 1660 were the last of their kind. In the early 1700s, peasant resistance mostly involved illegally hunting deer or gathering wood on enclosed land, not tearing down fences. Long memories of brutal defeats, reinforced by fear of ruling class forces that were now even stronger, discouraged any return to mass action.

Until the mid-1700s, the large landlords who owned most of English farmland seem to have been more interested in reaping the rewards of previous victories than in enclosing the remaining open fields and commons. About a quarter of the country’s farmland was still worked in open fields in 1700, but so long as rents covered costs, with a substantial surplus, few landlords chose to make changes.

When a new wave of enclosures began about 1755, spurred first by falling grain prices and then by rising prices during Napoleonic wars, the social and economic context was very different. English capitalist society, we might say, had become more “civilized.” In place of the rough methods of earlier years, enclosure became a structured bureaucratic process, subject to political oversight and regulation. Enclosure required detailed surveys and plans prepared by lawyers and professional enclosure commissioners, all accepted by the owners and tenants of three-quarters of the land involved (which was often a small minority of the people affected), then written into a Bill which had to be approved by a Parliamentary committee and both houses of Parliament.

Marx referred to the resulting Enclosure Acts as “decrees by which the landowners grant themselves the peoples’ land as private property, decrees of expropriation of the people.”[35]

Most Parliamentary enclosures seem to have carefully followed the law, including fairly allocating land or compensation to leaseholders large and small, but the law did not recognize customary common rights. Just as with the cruder methods of previous centuries, Parliamentary enclosure didn’t just consolidate land: it eliminated common rights and dispossessed the landless commoners who depended on them. When a 20th century historian called this “perfectly proper,” because the law was obeyed and property rights protected, Edward Thompson replied:

“Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery, played according to fair rules of property and law laid down by a parliament of property-owners and lawyers. …

“What was ‘perfectly proper’ in terms of capitalist property-relations involved, none the less, a rupture of the traditional integument of village custom and of right: and the social violence of enclosure consisted precisely in the drastic, total imposition upon the village of capitalist property-definitions.”[36]

There were some local riots after enclosure was approved, often in the form of stealing or burning fence posts and rails, but as J.M. Neeson has shown, most resistance took the form of “stubborn non-compliance, foot-dragging and mischief,” before an enclosure Bill went to London. Villagers refused to speak to surveyors or gave them inaccurate information, sent threatening letters, stole record books and field plans, and in general tried to force delays or drive up the landlords’ costs. In some cases, villagers petitioned Parliament to reject the proposed bill, but that was expensive and rarely successful.[37]