by DGR News Service | May 3, 2025 | NEWS, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: “A new report from Harvard’s Electricity Law Initiative says unless something changes, all U.S. consumers will pay billions of dollars to build new power plants to serve Big Tech.

Data centers are forecast to account for up to 12% of all U.S. electricity demand by 2028. They currently use about 4% of all electricity.

Historically, costs for new power plants, power lines and other infrastructure is paid for by all customers under the belief that everyone benefits from those investments.

‘But the staggering power demands of data centers defy this assumption,’ the report argues.”

AI burns through a lot of resources. And thanks to a paradox first identified way back in the 1860s, even a more energy-efficient AI is likely to simply mean more energy is used in the long run.

For most users, “large language models” such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT work like intuitive search engines. But unlike regular web-searches that find and retrieve data from anywhere along a global network of servers, AI models return data they’ve generated from scratch. Like powering up a nuclear reactor to use a calculator, this tailored process is very inefficient.

“This move is part of a national trend. The data center industry is booming all over, from Virginia to Texas to Oregon, and utilities across the country are responding by building new fossil fuel resources or delaying retirements, all at a time when scientists agree that cutting fossil fuel emissions is more urgent than ever. More than 9,000 MW of fossil fuel generation slated for closure has been delayed or is at risk of delay, and more than 10,800 MW of new fossil fuel generation has been planned, according to the sustainability research and policy center Frontier Group.

The backslide into fossil fuels is alarming to environmental and consumer advocates, and not only because it stands to slow down climate action and extend the harmful effects of fossil fuel use. Some also question the purported growth in demand — meaning utilities could be doubling down on climate-warming coal and gas to meet energy demand that won’t actually materialize.”

By M.V. Ramana / COUNTERPUNCH

One bright spot amidst all the terrible news last couple of months was the market’s reaction to DeepSeek, with BigTech firms like Nvidia and Microsoft and Google taking major hits in their capitalizations. Billionaires Nvidia’s Jensen Huang and Oracle’s Larry Ellison—who had, just a few days back, been part of Donald Trump’s first news conference—lost a combined 48 billion dollars in paper money. As a good friend of mine, who shall go unnamed because of their use of an expletive, said “I hate all AI, but it’s hard to not feel joy that these asshats are losing a lot of money.”

Another set of companies lost large fractions of their stock valuations: U.S. power, utility and natural gas companies. Electric utilities like Constellation, Vistra and Talen had gained stock value on the basis of the argument that there would be a major increase in demand for energy due to data centers and AI, allowing them to invest in new power plants and expensive nuclear projects (such as small modular reactor), and profit from this process. [The other source of revenue, at least in the case of Constellation, was government largesse.] The much lower energy demand from DeepSeek, at least as reported, renders these plans questionable at best.

Remembering Past Ranfare

But we have been here before. Consider, for example, the arguments made for building the V. C. Summer nuclear project in South Carolina. That project came out of the hype cycle during the first decade of this century, during one of the many so-called nuclear renaissances that have been regularly announced since the 1980s. [In 1985, for example, Oak Ridge National Laboratory Director Alvin Weinberg predicted such a renaissance and a second nuclear era—that is yet to materialize.] During the hype cycle in the first decade of this century, utility companies proposed constructing more than 30 reactors, of which only four proceeded to construction. Two of these reactors were in South Carolina.

As with most nuclear projects, public funding was critical. The funding came through the 2005 Energy Policy Act, the main legislative outcome from President George W. Bush’s push for nuclear power, which offered several incentives, including production tax credits that were valued at approximately $2.2 billion for V. C. Summer.

The justification offered by the CEO of the South Carolina Electric & Gas Company to the state’s Public Service Commission was the expectation that the company’s energy sales would increase by 22 percent between 2006 and 2016, and by nearly 30 percent by 2019. In fact, South Carolina Electric & Gas Company’s energy sales declined by 3 percent by the time 2016 rolled in. [Such mistakes are standard in the history of nuclear power. In the 1970s, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and utility companies were projecting that “about one thousand large nuclear power reactors” would be built “by the year 2000 and about two thousand, mostly breeder reactors, by 2010” on the basis of the grossly exaggerated estimates of how rapidly electricity production would grow during the same period. It turned out that “utilities were projecting four to nine times more electric power would be produced in the United States by nuclear power in 2000 than actually happened”.] In the case of South Carolina, the wrong projection about energy sales was the basis of the $9 billion plus spent on the abandoned V. C. Summer project.

The Racket Continues

With no sense of shame for that failure, one of the two companies involved in that fiasco recently expressed an interest in selling this project. On January 22, Santee Cooper’s President and CEO wrote, “We are seeing renewed interest in nuclear energy, fueled by advanced manufacturing investments, AI-driven data center demand, and the tech industry’s zero-carbon targets…Considering the long timelines required to bring new nuclear units online, Santee Cooper has a unique opportunity to explore options for Summer Units 2 and 3 and their related assets that could allow someone to generate reliable, carbon emissions-free electricity on a meaningfully shortened timeline”.

A couple of numbers to put those claims about timelines in perspective: the average nuclear reactor takes about 10 years to go from the beginning of construction—usually marked by when concrete is poured into the ground—to when it starts generating electricity. But one cannot go from deciding to build a reactor to pouring concrete in the ground overnight. It takes about five to ten years needed before the physical activities involved in building a reactor to obtain the environmental permits, and the safety evaluations, carry out public hearings (at least where they are held), and, most importantly, raise the tens of billions of dollars needed. Thus, even the “meaningfully shortened timeline” will mean upwards of a decade.

Going by the aftermath of the Deepseek, the AI and data center driven energy demand bubble seems to have crashed on a timeline far shorter than even that supposedly “meaningfully shortened timeline”. There is good reason to expect that this AI bubble wasn’t going to last, for there was no real business case to allow for the investment of billions. What DeepSeek did was to also show that the billions weren’t needed. As Emily Bender, a computer scientist who co-authored the famous paper about large language models that coined the term stochastic parrots, put it: “The emperor still has no clothes, but it’s very distressing to the emperor that their non-clothes can be made so much more cheaply.”

But utility companies are not giving up. At a recent meeting organized by the Nuclear Energy Institute, the lobbying organization for the nuclear industry, the Chief Financial Officer of Constellation Energy, the company owning the most nuclear reactors in the United States, admitted that the DeepSeek announcement “wasn’t a fun day” but maintained that it does not “change the demand outlook for power from the data economy. It’s going to come.” Likewise, during an “earnings call” earlier in February, Duke Energy President Harry Sideris maintained that data center hyperscalers are “full speed ahead”.

Looking Deeper

Such repetition, even in the face of profound questions about whether such a growth will occur, is to be expected, for it is key to the stock price evaluations and market capitalizations of these companies. The constant reiteration of the need for more and more electricity and other resources also adopts other narrative devices shown to be effective in a wide variety of settings, for example, pointing to the possibility that China would take the lead in some technological field or the other, and explicitly or implicitly arguing how utterly unacceptable that state of affairs would be. Never asking whether it even matters who wins this race for AI. These tropes and assertions about running out of power contribute to creating the economic equivalent of what Stuart Hall termed “moral panic”, thus allowing possible opposition to be overruled.

One effect of this slew of propaganda has been the near silence on the question of whether such growth of data centers or AI is desirable, even though there is ample evidence of the enormous environmental impacts of developing AI and building hyperscale data centers. Or for that matter the desirability of nuclear power.

As Lewis Mumford once despaired: “our technocrats are so committed to the worship of the sacred cow of technology that they say in effect: Let the machine prevail, though the earth be poisoned, the air be polluted, the food and water be contaminated, and mankind itself be condemned to a dreary and useless life, on a planet no more fit to support life than the sterile surface of the moon”.

But, of course, we live in a time of monsters. At a time when the levers of power are wielded by a megalomaniac who would like to colonize Mars, and despoil its already sterile environment.

by DGR News Service | Apr 27, 2025 | ANALYSIS, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: “I think we’re in the midst of a collapse of civilization, and we’re definitely in the midst of the end of the American empire. And when empires start to fail, a lot of people get really crazy. In The Culture of Make Believe, I predicted the rise of the Tea Party. I recognized that in a system based on competition and where people identify with the system, when times get tough, they wouldn’t blame the system, but instead, they would indicate it’s the damn Mexicans’ fault or the damn black people’s fault or the damn women’s fault or some other group. The thing that I didn’t predict was that the Left would go insane in its own way. I anticipated the rise of an authoritarian Right, but not authoritarianism more generally, to which the Left is not immune. The collapse of empire results in increased insecurity and the demand for stability. The cliché about Mussolini is that he made the trains run on time, that he brought about stability.” – Derrick Jensen

It’s not just stupid people. People can be very smart as individuals, but collectively we are stupid. Postmodernism is a case in point. It starts with a great idea, that we are influenced by the stories we’re told and the stories we’re told are influenced by history. It begins with the recognition that history is told by the winners and that the history we were taught through the 1940s, 50s and 60s was that manifest destiny is good, civilization is good, expanding humanity is good. Exemplary is the 1962 film How the West Was Won. It’s extraordinary in how it regards the building of dams and expansion of agriculture as simply great. Postmodernism starts with the insight that such a story is influenced by who has won, which is great, but then it draws the conclusion that nothing is real and there are only stories.

“This is the cult-like behavior of the postmodern left: if you disagree with any of the Holy Commandments of postmodernism/queer theory/transgender ideology, you must be silenced on not only that but on every other subject. Welcome to the death of discourse, brought to you by the postmodern left.”

Explainer: what is postmodernism?

Daniel Palmer, Monash University

I once asked a group of my students if they knew what the term postmodernism meant: one replied that it’s when you put everything in quotation marks. It wasn’t such a bad answer, because concepts such as “reality”, “truth” and “humanity” are invariably put under scrutiny by thinkers and “texts” associated with postmodernism.

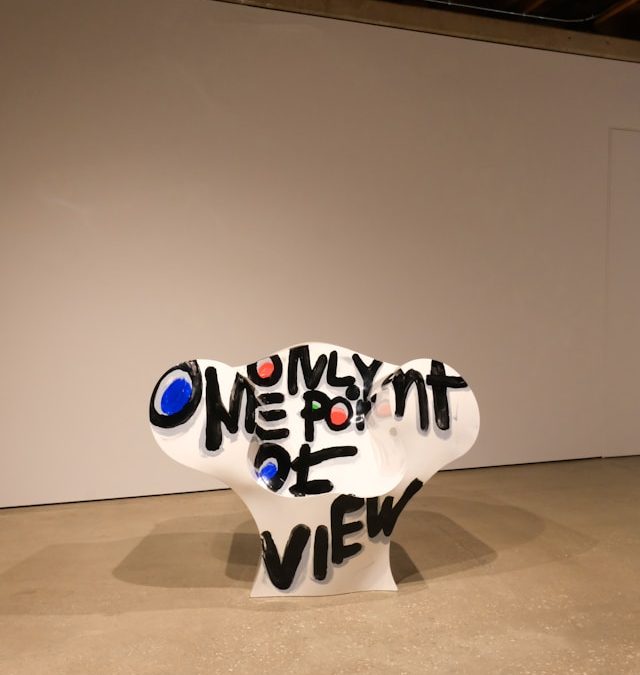

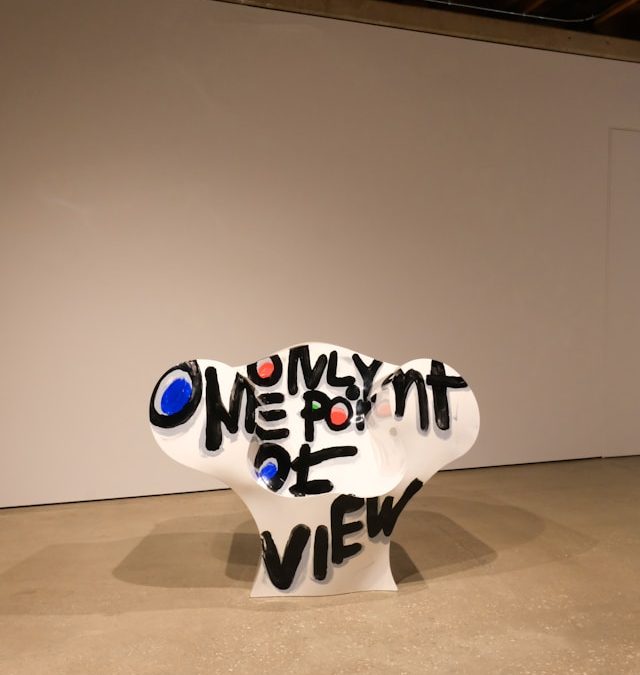

Postmodernism is often viewed as a culture of quotations.

Take Matt Groening’s The Simpsons (1989–). The very structure of the television show quotes the classic era of the family sitcom. While the misadventures of its cartoon characters ridicule all forms of institutionalised authority – patriarchal, political, religious and so on – it does so by endlessly quoting from other media texts.

This form of hyperconscious “intertextuality” generates a relentlessly ironic or postmodern worldview.

Relationship to modernism

The difficulty of defining postmodernism as a concept stems from its wide usage in a range of cultural and critical movements since the 1970s. Postmodernism describes not only a period but also a set of ideas, and can only be understood in relation to another equally complex term: modernism.

Modernism was a diverse art and cultural movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries whose common thread was a break with tradition, epitomised by poet Ezra Pound’s 1934 injunction to “make it new!”.

The “post” in postmodern suggests “after”. Postmodernism is best understood as a questioning of the ideas and values associated with a form of modernism that believes in progress and innovation. Modernism insists on a clear divide between art and popular culture.

But like modernism, postmodernism does not designate any one style of art or culture. On the contrary, it is often associated with pluralism and an abandonment of conventional ideas of originality and authorship in favour of a pastiche of “dead” styles.

Postmodern architecture

The shift from modernism to postmodernism is seen most dramatically in the world of architecture, where the term first gained widespread acceptance in the 1970s.

One of the first to use the term, architectural critic Charles Jencks suggested the end of modernism can be traced to an event in St Louis on July 15, 1972 at 3:32pm. At that moment, the derelict Pruitt-Igoe public housing project was demolished.

Built in 1951 and initially celebrated, it became proof of the supposed failure of the whole modernist project.

Jencks argued that while modernist architects were interested in unified meanings, universal truths, technology and structure, postmodernists favoured double coding (irony), vernacular contexts and surfaces. The city of Las Vegas became the ultimate expression of postmodern architecture.

Famous theorists

Theorists associated with postmodernism often used the term to mark a new cultural epoch in the West. For philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, the postmodern condition was defined as “incredulity towards metanarratives”; that is, a loss of faith in science and other emancipatory projects within modernity, such as Marxism.

Marxist literary theorist Fredric Jameson famously argued postmodernism was “the cultural logic of late capitalism” (by which he meant post-industrial, post-Fordist, multi-national consumer capitalism).

In his 1982 essay Postmodernism and Consumer Society, Jameson set out the major tropes of postmodern culture.

These included, to paraphrase: the substitution of pastiche for the satirical impulse of parody; a predilection for nostalgia; and a fixation on the perpetual present.

In Jameson’s pessimistic analysis, the loss of historical temporality and depth associated with postmodernism was akin to the world of the schizophrenic.

Postmodern visual art

In the visual arts, postmodernism is associated with a group of New York artists – including Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman – who were engaged in acts of image appropriation, and have since become known as The Pictures Generation after a 1977 show curated by Douglas Crimp.

By the 1980s postmodernism had become the dominant discourse, associated with “anything goes” pluralism, fragmentation, allusions, allegory and quotations. It represented an end to the avant-garde’s faith in originality and the progress of art.

But the origins of these strategies lay with Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, and the Pop artists of the 1960s in whose work culture had become a raw material. After all, Andy Warhol was the direct progenitor of the kitsch consumerist art of Jeff Koons in the 1980s.

Postmodern cultural identity

Postmodernism can also be a critical project, revealing the cultural constructions we designate as truth and opening up a variety of repressed other histories of modernity. Such as those of women, homosexuals and the colonised.

The modernist canon itself is revealed as patriarchal and racist, dominated by white heterosexual men. As a result, one of the most common themes addressed within postmodernism relates to cultural identity.

American conceptual artist Barbara Kruger’s statement that she is “concerned with who speaks and who is silent: with what is seen and what is not” encapsulates this broad critical project.

The discourse of postmodernism is associated with Australian artists such as Imants Tillers, Anne Zahalka and Tracey Moffatt.

Australia has been theorised by Paul Taylor and Paul Foss, editors of the influential journal Art & Text, as already postmodern, by virtue of its culture of “second-degree” – its uniquely unoriginal, antipodal appropriations of European culture.

If the language of postmodernism waned in the 1990s in favour of postcolonialism, the events of 9/11 in 2001 marked its exhaustion.

While the lessons of postmodernism continue to haunt, the term has become unfashionable, replaced by a combination of others such as globalisation, relational aesthetics and contemporaneity.

Daniel Palmer, Senior Lecturer, Art History & Theory Program, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo by Mike Von on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Apr 19, 2025 | ACTION, The Problem: Civilization

A Wild Earth Day!

On April 22:

Meet free-roaming bison and baby prairie dogs! Learn about oceans that need us and fires that don’t! Take a fast trip through human history, from cave art to the current mess! Get inspired by tales of resistance and songs of love! All donations go directly to help fund our annual conference.

And you can double your impact by giving during A Wild Earth Day!

A dedicated activist has offered to sponsor this year’s conference through her small business in Philadelphia. Richter Renovations will match gifts during the Earth Day fundraiser, up to $2000.

So get your biophilia on and mark your calendars! 6PM PST/9PM EST.

DGR CONFERENCE!

The annual conference will be in Philadelphia this year, August 1-5. Derrick and I will both be there. The conference is always a weekend of radical fun and friendship so let your enthusiasm build!

Click here for full information.

USA TOUR!

And we could really use your help. Since we are going to be traveling across the country, we want to make a whole tour of it. If you want to host us for a talk, we’ll go anywhere.

We’re calling it the “Don’t Cancel Me Tour.” The t-shirts will be easy; the events will take some courage. But we believe in you. I never guessed saving the planet would start with facing down the Cancel Mob, but here we are. Drop us a note (contact@deepgreenresistance.org) if you want to help.

STORE!

Our website is undergoing a massive overhaul. A new section is now complete–the DGR store! We have beautifully designed t-shirts and hoodies in a rainbow of colors, all of them declaring loving loyalty to the living planet. Check it out here.

HELP!

We can’t do any of this without your generous donations. We want to say thank you with some awesome premiums.

If you donate $100, you get some free books. For a $200 donation, you get books and the t-shirt of your choice. For a $500 donation, you get all the above and a batch of (in)famous gluten-free brownies. For a $1000 donation, all of that plus a private Zoom call with Derrick and the bears.

So check out our merch, put on your courage, and no matter what: find what you love, defend your beloved.

Stay strong!

Lierre (and Derrick and Deanna)

PLEASE DONATE

Deep Green Resistance Inc

PO Box 903

Crescent City, CA 95531-8002

Banner Photo by Shamblen Studios on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Apr 1, 2025 | ANALYSIS, The Problem: Civilization

By Tom Murphy / Do the Math

Surfing YouTube, I came across an interview of Ezra Klein by Stephen Colbert. He was promoting a new book called Abundance, basically arguing that scarcity is politically-manufactured by “both sides,” and that if we get our political act together, everybody can have more. Planetary limits need not apply. I’ve often been impressed by Klein’s sharp insights on politics, yet can’t reconcile how someone so smart misses the big-picture perspectives that grab my attention.

He’s not alone: tons of sharp minds don’t seem to be at all concerned about planetary limits or metastatic modernity, which for me has been a source of perennial puzzlement.

The logical answer is that I’m not the sharpest tool in the shed. Indeed, many of these folks could run cognitive/logical circles around me. And maybe that’s the end of the story. Yet it’s not the end of this post, as I try to work out what accounts for the disconnect, and (yet again) examine my own assuredness.

Imagined Basis

What is the basis of pundit-level rejection of my premise? Oh yeah: my premise is that modernity is a fleeting, patently unsustainable mode of life on Earth that will self-terminate on a historically relevant (i.e., brief) timescale—likely to convincingly crest the peak this century. Modernity can’t last.

I will reconstruct how I think an ultra-smart person might react, were I to present in conversation the premise that modernity can’t last—based on past interactions with such folks. Two branches stand out.

One branch would be the unwittingly spot-on admission of “I don’t see why not.” I could not have identified the core problem any better, and would be tempted to say: “Wow—what a courageous first step in recognizing our limited faculties. That humble confession is very big of you.” My not having the wit to prove conclusively to such folks that modernity can’t work (and I would say that no human possesses such mental powers) says very little about the complex reality of our future—operating without giving a flip as to what happens in human brains. But it’s also quite far from demonstrating convincingly how something as unsustainable as modernity—dependent on one-time exploitation of non-renewable resources—might possibly address the host of interacting elements that will contribute to its crumbling.

That branch aside, the common reply I want to spend more time on goes something like: “Just look at the past. No one could have foreseen the amazingness of today, and we ought to recognize that we are likewise ill-equipped to speculate on the future. In other words, anyone expressing your premise in the last 10,000 years would have turned out to be wrong [well, so far]. Chances, are: so are you.”

Damn. Blistering. How can one get up from that knockout? And the thing is, it’s a completely valid bit of logic. I also appreciate the intellectual humility involved. Why, then, am I so stubborn on this point? Is it because I want to be popular or rich? Then I’m even stupider than I thought, because those things are basically guaranteed to be incompatible with such a message. Is it because I crave end-times, having been dealt a bad hand and never “good at the game?” Nope: I thrived as an all-in astrophysicist and had/have a rather privileged and comfortable life that I would personally, selfishly prefer not to have disrupted. Is it out of fear of collapse? Getting warmer: that was a big early motivation—the alarming prospect of losing what I held until recently to be a glorious civilization. But at this point all I can say is that based on multiple lines of evidence I really think it’s the truth, and can’t easily or honestly argue myself out of this difficult spot. Denial, anger, bargaining, and depression don’t help us come to terms with the hard reality..

Returning to the putative response: I’ll name it as lazy. It’s superficial. It’s a shortcut, sidling up to: “Collapse hasn’t happened yet—in fact quite the opposite—and thus most likely will not.” It declines to examine the constituent pieces and arguments, falling back on a powerful and persuasive bit of logic straight out of the left brain. It has all the hallmarks: certain, crisp, abstract, decontextualized, logical, clever.

It carries the additional dual advantage of simultaneously avoiding unpleasant confrontation of a scary prospect and inviting starry-eyed wonder at magic the future might bring. No wonder it’s so magnetically attractive as a go-to response!. We’re both driven to it and attracted by it! The very smartest among us, in fact, often have the most to lose, and may therefore be among the most psychologically attached to modernity. We mustn’t forget that every human has a psychology, and is capable of impressive levels of denial for any number of reasons.

Some Metaphors

Its time for a few metaphors that help to frame my approach. I offer two related ones, because none are perfect. Together, they might work well enough for our purposes.

TAKE ONE

Imagine that someone tees up a golf ball in an indoor space full of hard objects: concrete walls and steel shelves—maybe loaded with heavy glass goblets and vases, etc. Poised to deliver a smashing blow to the ball with an over-sized driver, they ask me: “What do you think will happen if I hit this ball?” Imagining a comical movie scene where the ball makes a series of wild-ass bounces shattering priceless collectables as it goes, it might seem impossible to guess what all might or might not happen. So, I “cheat” and say: “The ball will come to rest.”

And guess what: I’m right! No matter how crazy the flight, it is guaranteed that in fairly short order, the ball will no longer be moving. I could even put a timescale on it: stopped within 10 seconds, or maybe even 5—depending on the dimensions of the room. I can say this because each collision will remove a fair bit of energy from the ball, and the smaller the room, the shorter the time between energy-sapping events.

During the middle of the experiment, it is clear that mayhem is happening, and it’s essentially impossible to predict what’s next. That’s where we are in modernity. So, yes: some intellectual humility is called for. We could not have predicted any of the particulars, after all. But one can still stand by the prediction that the ball will come to rest, much as one can say modernity will wind itself down.

TAKE TWO

The golf ball metaphor does 80% of the work, but I don’t fully embrace it because the ball is at maximum destructive capacity at the very beginning, its damage-potential decaying from the first moment. Modernity took some time to accelerate to present speed, now at a fever pitch. For this, I think of a rock tumbling down a slope.

I do a fair bit of hiking, sometimes off trail where—careful as I am—I might occasionally dislodge a rock on a steep slope. What happens next is entirely unpredictable (even if deterministic given initial conditions). Most of the time the rock just slides just a few centimeters; sometimes it will lazily tumble a few meters; or more rarely it will pick up speed and hurtle hundreds of meters down the slope in a kinetic spectacle. Kilometer scales are not entirely out of the question in some locations.

Still, for all these scenarios, I am sure of one thing: the rock will come to rest—possibly in multiple fragments. I can also put a reasonable timescale on it, mid-journey, based on its behavior to that point. I can tell if it’s picking up speed. I can evaluate if the slope is moderating or will soon come to an end. It’s not impossible to make a decent guess for how long it might go, even if unable to predict what hops, collisions, or deflections it might execute along the way.

Maybe the phrase “a rolling stone gathers no moss” can be re-interpreted as: kinetic mayhem is no basis for a healthy, relational ecology. If tumbling boulders were the normal/default state of things, mountains would not last long (or more to the point: never come into being!). Likewise, one species driving millions of others to extinction in mere centuries is not a normal, sustainable state of affairs. That $#!+ has to stop.

Modernity’s Turn

Modernity is far more complex than a tumbling rock. But one side effect of this is a multitude of facets to consider. When many of them line up to tell a similar story…well, that story becomes more compelling. I offer a few, here.

POPULATION

Global human population has been a super-exponential, in that the annual growth rate as a percentage of the total has steadily climbed through the millennia and centuries (0.04% after agriculture began, up to 2% in the 1960s). It is no shock to anyone that we may be straining (or overtaxing) what the planet can support. Indeed, the growth rate has been decreasing for the last 60 years, and the drop appears to be accelerating lately. Almost any model predicts a global peak before this century is over, and possibly as soon as the next 15–20 years. This is, of course, highly relevant to modernity. Economies will shrink and possibly collapse (being predicated on growth) as population falls from a peak. Such a turn could precipitate a whole new phase that “no one could have seen coming.” I’m looking at you, pundits!

The argument of “just look to the past” and imagining some sort of extrapolation begins to seem dubious or even outright silly in the context of a plummeting population. Let’s face it: we don’t know how it plays out. Loss of modern technological capabilities is not at all a mental stretch, even if such “muscles” are rarely exercised.

RESOURCES

Modernity hungry!. Fossil fuels have played a huge role in the dramatic acceleration of the past few centuries. We all know this is a limited-time prospect. Oil discoveries peaked over a half-century ago, so the writing is on the wall for production decline on a timescale of decades. Pretending that solar and wind will sweep in as substitutes involves a fair bit of magical thinking and ignorance of myriad practical details (back to the “I don’t see why not” response). We face an unprecedented transition as fossil fuels wane, so that the acceleration of the past is very likely to run out of steam. Even holding steady involves an unsubstantiated leap of faith—never fleshed out as to how it all could possibly work. “I don’t see why not” is about the best one can expect.

Mined materials are likewise non-renewable and being consumed at an all-time-high rate. Ore grade has fallen dramatically, so that we now must pursue increasingly marginal and deeper deposits and thus impact more land, while discharging an ever-increasing volume of mine tailings. This happened fast: most material extraction has occurred in the last century (or even 50 years). We would be foolish to imagine an extrapolation of the past or even maintaining similar levels of activity for any long duration. More realistically, these practices will be undercut by declining population and energy availability. I’ve spent plenty of time pointing out that recycling can at best stretch out the timeline, but not by orders of magnitude.

WATER/AGRICULTURE

Agricultural productivity has also steadily increased, but on the back of “mining” non-renewable resources like ground water and soils—not to mention an extraordinary dependence on finite fossil fuels. Okay: at least water and soils can renew on long timescales, but our rate of depletion far outstrips replenishment. Land turned to desert by overuse stops even trying to maintain soils, while also suppressing water replenishment by squelching rainfall. This is yet another domain where the fact that the past has involved a steady march in one direction is quite far from guaranteeing that direction as a constant of nature. Its very “success” is what hastens its failure. The simple logic of “hasn’t happened yet” blithely bypasses a lot of context sitting in plain sight.

CLIMATE CHANGE

I don’t usually stress climate change, because I view it as one symptom of a more general disease. Moreover, should we magically eliminate climate change in a blink, my assessment is hardly altered since so many other factors are contributing to the overall phenomenon of modernity’s unsustainability. I include climate change here because it seems to be the one element that has percolated to the attention of the pundit-class as a potential existential threat. It isn’t yet clear how modernity trucks on without fossil fuels. Yet, even if we were to curtail their use by 2050, the climate damage may be great enough to reverse modernity’s fortunes (actually, the most catastrophic legacy of CO2 emissions may be ocean acidification rather than climate change). Again, the “logic” of extrapolation becomes rather dubious. The faith-based assumption is that we will “technology” our way out of the crisis, which becomes perfectly straightforward if ignoring all the other factors at play. Increased materials demand to “technofix” our ills (and the associated mining, habitat destruction, pollution) puts a fly in the ointment. But most concerning to me is what we already do with energy. Answer: initiate a sixth mass extinction by running a resource-hungry, human supremacist, global market economy. Most climate change “solutions” assign top priority to maintaining the destructive juggernaut at full speed—without question.

ECOLOGICAL COLLAPSE

This brings me to the ultimate peril. As large, hungry, high-maintenance mammals on this planet, we are utterly dependent on a healthy, vibrant, biodiverse ecology—in ways we can’t begin to fathom. It’s beyond our meat-brain capacity to appreciate. Long-term survival at the hands of evolution has never once required cognitive comprehension of the myriad subtle relationships necessary for a stable community of life. An amoeba, mayfly, newt, or hedgehog gets on just fine without such knowledge. What is required is fitting into the niches and interrelationships patiently worked out through the process of evolution. Guess what: in a flash, we jumped the tracks into a patently non-ecological lifestyle not vetted by evolution to be viable. It appears to be not even close.

This is not just a theoretical concern. Biologists are pretty clear that a sixth mass extinction is underway as a direct result of modernity. The dots are not particularly hard to connect. We mine and spew/dispose materials alien to the community of life into the environment. Good luck, critters! We eliminate or shatter wild space in favor of “developed” land: exterminating, eradicating, displacing, and impoverishing the life that depends on that land and its resident web of life. The struggle can take decades to resolve as populations ebb—generation after generation—on the road to inevitable failure. Even this decades-long process is effectively instant compared to the millions of years over which the intricate web was crafted.

I have pointed out a number of times that we are now down to 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass per human on the planet. It was 80 kg per person in 1800 and 50,000 kg per person before the start of the agricultural revolution—when humans held a roughly proportionate share of mammal biomass compared to the other mammal species. In my lifetime (born 1970), the average decline in vertebrate populations has been roughly 70%. Fish, insects, birds decline at 1–2% per year, which compounds quickly. Extinction rates are now hundreds of times higher than the background, almost all of which has transpired in the last century.

Just like the golf ball in the room or the rock tumbling down the mountainside, these figures allow us to place approximate, relevant timescales on the phenomenon of ecological collapse—and that timescale is at the sub-century level. We’re watching its opening act, and the rate is alarming. The consequences, however, are easily brushed aside in ignorance. Try it yourself: mention to someone that humans can’t survive ecological collapse and—Family Feud style—I’d put my money on “I don’t see why not” being among the most frequent responses.

So, Don’t Give Me That…

I think you can see why I’m not swayed by the tidy and fully-decontextualized lazy logic of extrapolation offered by some of the smartest people. This psychologically satisfying logic can have such a powerfully persuasive pull that it short-circuits serious considerations of the counterarguments. This is especially true when the relevant subjects are uncomfortable, inconvenient, unfamiliar, and also happen to be beyond our capacity to cognitively master. Just because we can’t understand something doesn’t render it non-existent. Seeking answers from within our brains gets what it deserves: garbage in—garbage out.

We used the metaphors of a golf ball or rolling stone necessarily coming to rest. Likewise, a thrown rock will return to the ground, or a flying contraption not based on the aerodynamic principles of sustainable flight will fail to stay aloft. Modernity has no ecological context (no rich set of evolved interrelationships and co-dependencies with the rest of the community of life) and is rapidly demonstrating its unsustainable nature on many parallel, interconnected fronts. This would seem to make the default position clear: modernity will come to rest on a century-ish timescale, the initial reversal possibly becoming evident in mere decades. [Correction: I think it will likely be mostly stopped on a century timescale, but it may take millennia to fully melt into whatever mode comes next.]

Retreating to the logic of extrapolation or basic unpredictability amounts to a faith-based approach that deflects any actual analysis: a cowardly dodge. Given the multi-layer, parallel concerns all pointing to a temporary modernity, it would seem to put the burden of proof that “the unsustainable can be sustained” squarely on the collapse-deniers. The default position is that unsustainable systems fail; that non-ecological modes lack longevity; that unprecedented and extreme departures do not become the rule; that no species is capable of going-it alone. Arguing the extraordinary obverse demands extraordinary evidence, which of course is not availing itself.

When logic suggests an attractive bypass, recognize that logic is only a narrow and disconnected component of a more complete, complex reality. Most importantly, the logic of extrapolation only serves to throw up a cautionary flag, without even bothering to address the relevant dynamics. That particular flag is later recognized as a misfire once the appropriate elements are given due consideration: this time is different, because modernity is outrageously different from the larger temporal and ecological context. Pretending otherwise requires turning a spider’s-worth of blind eyes to protect a short-term, ideological, emotionally “safe” agenda. Pretend all you want: it won’t change what’s real.

Photo by CHRIS ARJOON on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Mar 12, 2025 | ACTION, Protests & Symbolic Acts, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: “In recent years, the Southeast Asian country of Vietnam experienced a boom in renewable energy investments driven by generous feed-in tariffs, under which the state committed to buying electricity for 20 years at above-market prices. However, the high tariffs increased losses for Vietnam’s state-owned power utility EVN, the only buyer of the generated electricity, and led to an increase in power prices for households and factories. Authorities have repeatedly tried to reduce the high tariffs. Now they are considering a retroactive review of the criteria set for accessing the feed-in tariffs.”

“It’s really hard to build wind farms in Arizona, and if you put this into place, it’s just pretty much wiping you out,” said Troy Rule, a professor of law at Arizona State University and a published expert on renewable energy systems. “It’s like you’re trying to kill Arizona’s wind farm industry.”

United States Congressional House Republicans are seeking to prevent the use of taxpayer dollars to incentivize what they describe as “green energy boondoggles” on agricultural lands, citing subsidies that could cost taxpayers hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade.

They are expensive to build, just finding their footing on this side of the Atlantic, and have faced backlash from parties as varied as beachfront property owners and fishermen to coastal businesses and fossil fuel backers(most of the developers have fossil fuel ties).

The future of Humboldt County’s offshore wind industry appears increasingly uncertain following mass layoffs at RWE and Vineyard Offshore, the multinational energy companies leading efforts to develop commercial-scale floating wind farms on the North Coast. The job cuts come in response to widespread market uncertainty following President Donald Trump’s efforts to ban offshore wind development in the United States.

A critical permit for an offshore wind farm planned near the New Jersey Shore has been invalidated by an administrative appeals board.

By Malaka Rodrigo / Mongabay

COLOMBO — In a dramatic turn of events, Indian tycoon Gautam Adani’s Green Energy Limited (AGEL) has withdrawn from the second phase of a proposed wind power project in northern Sri Lanka. The project, which was planned to generate 250 MW through the installation of 52 wind turbines in Mannar in the island’s north, faced strong opposition since the beginning due to serious environmental implications and allegations of financial irregularities.

While renewable energy is a crucial need in the era of climate change, Sri Lankan environmentalists opposed the project, citing potential ecological damage to the sensitive Mannar region. Additionally, concerns arose over the way the contract was awarded, without a competitive bidding process.

The former government, led by President Ranil Wickremesinghe, had inked an agreement with AGEL, setting the power purchase price at $0.82 per unit for 20 years. This rate was significantly higher than rates typically offered by local companies. “This is an increase of about 70%, a scandalous deal that should be investigated,” said Rohan Pethiyagoda, a globally recognized taxonomist and former deputy chair of the IUCN’s Species Survival Commission.

Legal battles

Five lawsuits were filed against this project by local environmental organizations, including the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society, the Centre for Environmental Justice and the Environmental Foundation Ltd. In January, the newly elected government expressed its desire to cancel the initial agreement and to renegotiate its terms and conditions, citing the high electricity tariff. Environmentalists welcomed the decision, believing the project would be scrapped entirely. However, their relief was short-lived when AGEL clarified that the project itself was not canceled, only the tariff agreement.

Government spokesperson Nalinda Jayatissa later confirmed that the project would proceed after renegotiating a lower power purchase rate. However, two weeks later, AGEL announced its complete withdrawal from the project, a decision widely believed to be influenced by the government’s stance.

Wind energy potential

Sri Lanka has been exploring wind energy potential for more than two decades, with the first large-scale wind farm in Mannar named Thambapavani commissioned in 2020. This facility, comprising 30 wind turbines, currently generates 100 MW of power. With an additional 20 turbines planned, the Mannar wind sector would have surpassed 100 towers.

The Adani Group had pledged an investment totaling $442 million, and already, $5 million has been spent in predevelopment activities. On Feb. 15, the Adani Group formally announced its decision to leave the project. In a statement, the group stated: “We would respectfully withdraw from the said project. As we bow out, we wish to reaffirm that we would always be available for the Sri Lankan government to have us undertake any development opportunity.”

Environmentalists argue that Mannar, a fragile peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow land strip, cannot sustain such extensive development. “If built, this project would exceed the carrying capacity of the island,” Pethiyagoda noted.

Mannar is not only a growing tourism hub, known for its pristine beaches and archaeological sites, but also Sri Lanka’s most important bird migration corridor. As the last landmass along the Central Asian Flyway, the region hosts millions of migratory birds, including 20 globally threatened species, he added.

Sampath Seneviratne of the University of Colombo, who has conducted satellite tracking research on migratory birds, highlighted the global importance of Mannar. “Some birds that winter here have home ranges as far as the Arctic Circle,” he said. His research has shown how extensively these birds rely on the Mannar Peninsula.

Although mitigation measures such as bird monitoring radar have been proposed to reduce turbine collisions, power lines distributing electricity remain a significant threat, particularly to species like flamingos, a major attraction in Mannar. The power lines distributing electricity from the already established wind farm near the Vankalai Ramsar Wetland and are already proven to be a death trap for unsuspecting feathered kind.

Nature-based tourism

Given Mannar’s ecological significance, conservationists say the region has greater potential as a destination for ecotourism rather than large-scale industrial projects. “Mannar’s rich biodiversity and historical value make it ideal for nature-friendly tourism, which would also benefit the local community,” Pethiyagoda added.

With AGEL’s withdrawal, Sri Lanka now faces the challenge of balancing its renewable energy ambitions with environmental conservation. However, there are other sites in Sri Lanka having more wind power potential, and Sri Lankan environmentalists hope ecologically rich Mannar will be spared from unsustainable wind farms projects.

Photo by Dattatreya Patra on Unsplash