by DGR News Service | Jul 1, 2019 | Building Alternatives

Editors Note: At Deep Green Resistance, we have a fundamental critique of agriculture, which is the most destructive activity human beings have ever done. However, horticulture, permaculture, and small-scale cultivation of biodiverse polycultures can be done in a sustainable way that enhances local ecology. This food source will be essential as industrial food systems collapse due to climate instability and human cultures are forced to adopt localized systems, and the generation and strengthening of these systems will give people more autonomy for resistance work.

by Isabel Marlens / Image: Association for Temperate Agroforestry

Hou Xueying, a mother from Shanghai, was tired of food safety scares and of a city life disconnected from the land. So she moved her family to the country to learn about sustainable farming. Her parents disapproved; they had struggled to give her a comfortable life in the city — they could not understand why she would throw it away. When she got to the country, she found that the older generation of farmers could only tell her how to grow as they did, using chemical fertilizers, toxic insecticides.

Still, she persisted, and today she runs a diversified organic farm that is, in her words, a “self-reliant ecosystem.” She raises a wide variety of animals and crops, making use of ingenious techniques — like allowing ducks into the rice paddies — to fertilize plants and eliminate pests without using chemicals. She’s also turned her farm into a place of learning, teaching children from the city where their food comes from. Through all of this, Hou Xueying has found a community that shares her values for the first time. She believes that the importance of the farming way of life extends far beyond putting good food on the table. As she explains in the short film, Farmed with Love, “Only conscious foodies can save the world.”

~~~

Many of us have heard some version of this statistic: the average age of farmers worldwide hovers around sixty years old. In the U.S., farmers over sixty-five outnumber farmers under thirty-five by a margin of six to one. People like Hou Xueying are going against the tide which has been tugging young people from the land for a long time, leaving older people alone on farms, with no one to take their place once they’re gone (except, increasingly, robots). So truly, as this older generation of farmers retires — a generation that widely embraced large-scale industrial farming — the question grows more pressing: who will grow the food of the future and what will their farms look like?

Every person on earth needs food every day. Every day, food is tended, harvested, transported, stored, and served up on our tables. In a very real sense, food cannot be separated from life itself. And so it has been said that changing the way we grow and eat food is one of the most powerful tools we have for changing our economies and society as a whole.

So when we ask: what will the farms of the future look like? We should really be asking — what do we want the future to look like? And then answers may begin to emerge.

Though many are enamored of technological solutions, others have pointed to tech’s inescapable environmental impacts, to the way it strengthens corporate monopolies, and to the already evident, and as yet unforeseen, effects that it has on society, including on human health and happiness. When I look at the young people I know, at the issues that concern them most, four points of focus rise to the surface. These can be rather broadly categorized as: climate and the environment, diversity in its myriad forms, economic inequality, and a lack of community, loneliness. Young people don’t want to work the land if that means working long hours for low pay, using dangerous chemicals, while the fruits of their labor are borne away to profit corporate executives they will never meet. But that doesn’t mean a future in which we don’t work the land at all. In fact, it means quite the opposite.

~~~

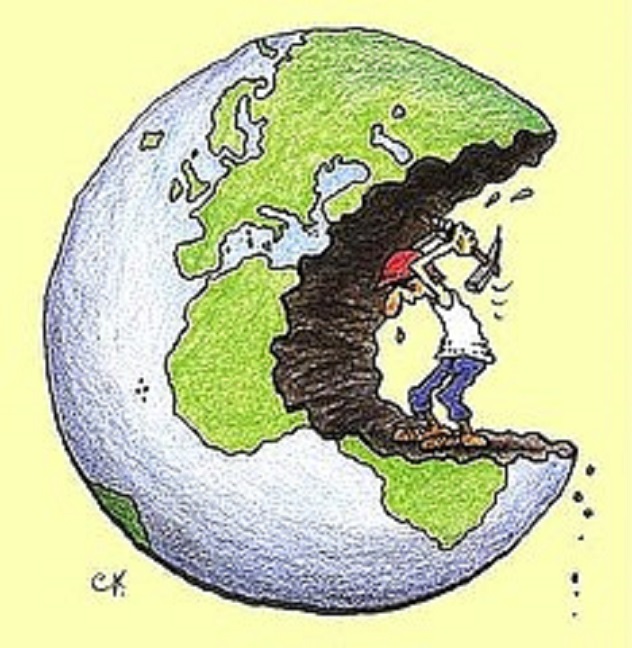

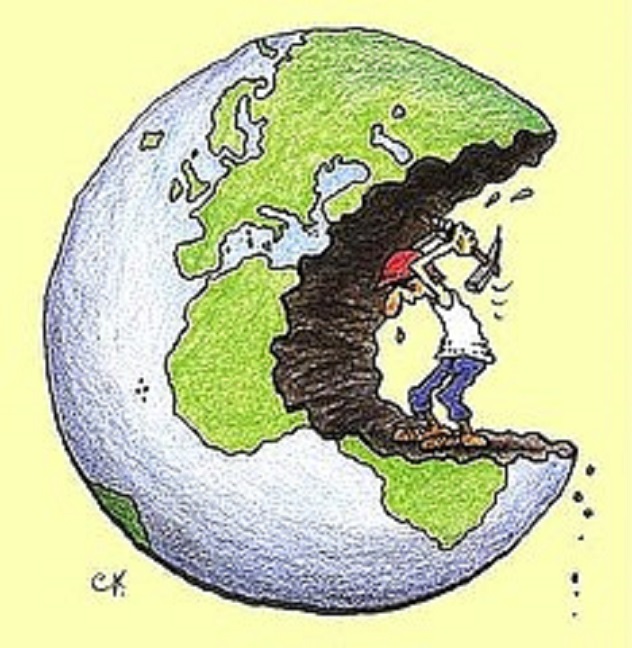

Climate change and agriculture are inextricably intertwined.

As I’m sure many of us know by now, our globalized industrial food system is a major contributor to anthropogenic climate change. The machinery and chemicals involved in industrial farming rely heavily on fossil fuels. So does packaging and refrigeration, not to mention the transport of food around the world by truck, ship, and plane. Many countries import and export nearly identical quantities of the same products. All of this creates economic activity, which adds to indicators of “progress” like GDP; not reflected in these numbers are the environmental costs of all the fossil fuels burned in the process.

At the same time, more and more of the forests, grasslands, and wetlands that helped maintain the nearly perfect balance of the carbon cycle until the start of the industrial revolution are being cleared to make way for livestock or annual crops, which do not play the same role in sequestering carbon. This wreaks more havoc with the earth’s natural climate-stabilizing systems.

On the other side of the coin, the changing climate is threatening agriculture as we know it. Increasingly extreme temperatures and weather events harm food crops. Studies show that the parts of the global South where people are already food insecure are being hit hardest. Many of these regions are less industrialized, less “developed” parts of the world, and so contributed little to the creation of this crisis — and yet, they are suffering the most.

In short, industrial monocultures — those big farms you see with acres and acres of corn or soy, not to mention those giant cattle feedlots — are systems that degenerate, they die,over time. They produce more carbon emissions than they sequester. Their pesticides kill insects, including pollinators, a trend which may soon initiate “the collapse of nature.”

Every year, they suck the nutrients from the soil, and replace them with toxic chemicals. They draw water from local watersheds, pollute it, and let it run off into gutters, or evaporate when hot weather comes, rather than employing management techniques that would allow it to sink back down to replenish local aquifers. Eventually, land treated this way becomes barren, eroding away to create dead zones in rivers and oceans or being lifted up by the wind to join the particulate matter in the air, poisoning the lungs of human beings (it’s telling that a recent report showed that Fresno and Bakersfield, in the heart of California’s industrial farm-filled Central Valley, have the worst particulate pollution in the USA). The air is truly brown in such places. The crops grown on these farms are sent off by truck or ship to factories where they’re processed and packaged — using more resources — and finally delivered to our homes, often in a form that’s as bad for our bodies as the dust is for our lungs.

This is what agriculture looks like in a globalized corporate economy, where, like the nutrients from the soil, the livelihood is sucked from farming communities and siphoned up into the coffers of a few giant corporations .

But as I’m sure many of us know by now, this is not what agriculture has to look like, by any means. Farms can be regenerative, living systems, that produce a bounty but no waste. They can supply the needs of a local community — if that community is willing embrace the idea of eating a mostly seasonal, locally adapted diet — with no need for long-distance transport by trucks, ships, or planes. Farms do not have to be net carbon emitters — plants absorb CO2 when they photosynthesize, and only emit it very slowly, through respiration and decomposition; studies show that, if managed correctly, farms, orchards, and even animal grazing systems can become places that sink and sequester CO2.

Not only that, but these are the same kinds of diversified farming systems that make people most resilient in the face of climate change. If we grow one kind of bean, for example, as a cash crop, and then the summer is too hot for that variety, we lose absolutely everything — all of our profits, which we would have used to buy food throughout the year. If we grow a diverse variety of crops, however, all with slightly different climactic limitations, then not only will a heat wave fail to do us in, but we can feed ourselves, right from our own backyards, no matter what happens. In fact, there are many points in favor of small diversified farms. Even minimal diversification has been shown to increase crop yields, while intensive permaculture systems — which have only recently been recognized by science — have the potential to completely transform our concept of productivity, and of what a “farm” is.

But that’s only the beginning.

~~~

When we talk about “diversified farms,” we usually mean crop diversity. But there is also wild biodiversity, human diversity, cultural diversity, language diversity, diversity in ways of thinking and being — all of which oppose the corporate consumer human monoculture which is so swiftly, insidiously spreading. Researchers have correlated biodiversity with language diversity, while others have found that certain regions function as “bio-cultural refugia,” harboring “place specific social memories related to food security and stewardship of biodiversity.” It’s easy to see these ideas brought to life in the context of a local food culture — crop varieties, local species and geography, language, and other aspects of culture like food preparation, celebrations, ways of passing knowledge on to the next generation, are all intimately connected. Lose any one element and the whole system is threatened.

Colonizers have long removed Indigenous people from their land knowing that this in turn will deprive them of their food culture, and so make them dependent on the colonizer’s economy — creating widening ripples of destruction.

In the same way that a colonizing culture hopes to put the world to work for a single purpose (usually, creating wealth for a specific set of colonizing elites) vast industrial farms destroy diverse ecosystems and replace them with a single species, like corn. This has been a driving force behind the sixth mass extinction which is urgently threatening all life on earth. But human beings are animal species too, after all, who could be playing supportive roles in diverse ecosystems, rather than acting as agents of destruction. In fact, corn now has a bad reputation in many parts of the world, but the corn, and the humans who first helped it to evolve thousands of years ago, are not to blame. There are few things more beautiful than the gemlike kernels of the heirloom corn varieties which long provided the basis of a healthy, vibrant, balanced diet for people throughout what is now Mexico and the United States — and which still does so for some today. These varieties are adapted to be drought-resistant, to withstand extremes of heat or cold, and are integral to many aspects of the cultures that rely upon them for survival.

This brings us back to the idea of a changing climate, of extremes. Over all the years that people have been planting seeds, they have been participating in a process of evolutionary adaptation: they’ve been selecting the seeds that thrived in their particular soil, with their particular weather conditions, their particular light. Seeds banks are great — especially those that save only Indigenous, non-corporate patented varieties; but they are not enough. We need living seed banks, seeds planted every year — eased into an uncertain future — if we want a real hope for survival.

Not only that, but farmers who grow a single crop for export instead of growing for their local community are at the mercy of another force as volatile the weather: the global economy. Many of us remember The Grapes of Wrath, the image of men dousing oranges with kerosene, throwing potatoes into the river and guarding them with guns, while the children of the migrant laborers looked on, starving. Modern versions of this still happen. Millions of people are hungry, and yet the amount of food we waste every day is absolutely staggering.

As John Steinbeck wrote, back in 1939, in a passage that still captures the essence of the global food system today:

“There is a crime here that goes beyond denunciation. There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolize. There is a failure here that topples all our success. The fertile earth, the straight tree rows, the sturdy trunks, and the ripe fruit. And children dying of pellagra must die because a profit cannot be taken from an orange.”

~~~

Of course, the global economy in general is vastly unequal. This relates to the food system in different ways in different parts of the world. In wealthy, industrially developed countries, fresh, local, organic foods are generally thought of as being accessible only to high-income people (and to a great extent this is true), while organic farming is thought of as an occupation accessible only to people with privilege (also true, in some cases). Meanwhile, in the less “developed” world, locally grown and adapted foods, along with farming, are often stigmatized as backward, while the fat and sugar-filled processed foods that have wreaked havoc with the health of the developed world are held up as symbols of the future.

I believe that it’s generally wrong to tell anyone what they should or should not be eating, but it is important to question these kinds of assumptions. At the moment, high quality, local, organic food is a symbol of privilege in developed countries. But this is due to a rigged economic system — in which tax laws, trade agreements, government subsidies, and absolutely outrageous advertising budgets for things like sugary drinks and processed foods, systematically bolster multinational corporations — and not because of any quality inherent to the food itself. Once, not so long ago, it was the less economically privileged people who grew fresh, heirloom organic produce — of a quality that many of us can only dream about today — in backyards, on farms, in empty lots. Today, we think of processed and fast foods as being the cheapest options. But this, again, is because governments are doling out subsidies to corn and soy farmers, raising insurance and loan rates on fruit and veggie farmers, and handing ever more power to big business. We think of growing one’s own food as something that is only accessible to those with privilege, and to a great extent this is true as well. Land is prohibitively expensive, and time, under capitalism, is the most scarce, the most precious resource of all. The typical CEO is paid 162 times what his low-level employees make per year, and so many must work multiple jobs and eighty-hour weeks if they want to feed their families. Of course, the poor quality of affordable foods contributes to health problems that take up more time and increase financial burdens.

These are horrible structural injustices, and the structures that perpetrate them have to be dismantled. Yet, while the food system is a great place to start, we must not forget that many of the people who have been responsible for growing food over the last several hundred years have done so in the context of slavery, or of exploitative tenant or migrant farming, leaving legacies of trauma connected to land and food that cannot, and should not, be easily forgotten.

However, despite these absolutely undeniable wrongs, many are beginning to agree that without food sovereignty (defined here as,“The right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems,”) we cannot have meaningful control over our lives, or our futures. As Leah Penniman, of Soul Fire Farm in Albany, New York, points out, there is a lot of racism built into the food system — food apartheid, as she describes it — and the separation of certain people from land and good food has not been an accident. She is one of many at the forefront of a movement that is reconnecting systemically marginalized people to land and to food.

This can be as simple as growing fresh food in vacant lots, on rooftops, on the grounds of community buildings like libraries, schools, churches. “Crop swaps,” or movements like #FoodIsFree — ways of trading produce for low or no cost — are amazing solutions that not only equalize the local food game, but also bring people together, building real community.

Meanwhile, in the global South, some are rejecting the idea that leaving the land for polluted, overpopulated cities is a sign of progress. One’s income might be higher working in an urban sweatshop than it would be in a rural village. But that increased income does not necessarily reflect an increased quality of life. In villages where people own their own land and live as they have for generations — using clean water, eating local foods, making clothes and other goods from locally sourced materials, relying on community support for things like child care — a comfortable life can cost almost nothing. (This is why corporate land grabs, for purposes like mining, logging, oil drilling and factory farming, are among the most pressing human rights issues of our time.) In confirmation of this, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN has declared that small family farming is the only way to feed a growing population, while the economic powers that be have confirmed it by creating a climate in which those who fight for land rights must fear for their lives.

In the end, you could say it comes down to this: if we all divest our time, energy and money from the corporations that fill megastores and supermarkets, and invest instead in ourselves, in local farmers and small local businesses, then we can keep money and precious resources circulating in our communities. When we do so, the creation of local food economies can play a meaningful role in equalizing society as a whole. And there are added benefits. When people and local governments reclaim their resources, it weakens the economic power of corporations, and strengthens democracy. Not only that, but societies that don’t leave people desperate are societies where people are less likely to turn against each other. There is the potential for a decline in xenophobia and conflict, and for diverse communities to unite, instead, against the real enemies: those who profit enormously off a system of gross injustice, and inequality.

~~~

Nashira is an urban ecovillage near the Colombian city of Cali. It is run entirely by women, most from low-income families, and many of whom were left as single mothers by decades of civil conflict. Other women living at Nashira are survivors of domestic or sexual abuse. All are looking for a safe place to raise children, and a way to put food on the table.

Nashira can provide them with both — and more. It is a self-sustaining ecovillage, with a matriarchal democratic system of governance, that is built and operates on strict ecological principles. The fact that Nashira residents grow their own food as a community, as well as producing and selling sustainable food for income, has given a lot of these women and their families true safety, freedom, and stability for the first time in their lives.

Around the world, ecovillages more or less like Nashira are emerging. They are home to every kind of person, and yet they tend to share one thing in common: a focus on the importance of growing food as a community for sustainability, economic independence, health, and happiness.

There has been a lot of discussion about how best to name our time in history — the “Technological Age,” perhaps? — but George Monbiot has declared that it can most accurately be described as “The Age of Loneliness.” Our mental health statistics are grim — including, notably, the suicide statistics for farmers struggling in the industrial food system (here are some from the USA and India). We work long hours and are dependent on a few corporations for all of our basic needs (looking at you, Amazon), while technology is allowing for ever fewer human interactions (many people I know have their groceries delivered while they’re at work, and never see the inside of a store at all). While online communities have emerged that do serve beneficial purposes, it’s simply not enough. Human beings are social animals. We’re evolved to rely upon each other — for everything. We’re calmed by interdependent, mutually beneficial relationships, by support and sharing. We’re also calmed, strengthened, and satisfied by working with living plants and animals, especially when, by doing so, we’re securely able to feed our families. Around the world, growing food has proven beneficial for prisoners, school children, youth in foster care,unhoused peoples and trauma survivors.

And of course, we all know that there’s nothing better than food for bringing people together. Whether it’s organizing a work party to pick berries, planning produce-trading parties, preparing potlucks for celebration, or simply running into friends at a local market during daily shopping, the interactions we have in the context of a local food culture make the world a less lonely place.

~~~

Ok, so the farms of the future should be regenerative, diverse, accessible, community-oriented, places of celebration. But for many of us — in particular those who are interested in actually becoming farmers — there are still a lot of barriers in the way of getting started.

The cost of land is the biggest. In the USA, between 1992 and 2012, three acres of farmland were lost to development every minute. Particularly near urban centers — where organic farmers find their largest markets — real estate developers are able to pay so much more than farmers can afford (banks are nervous about lending to farmers under the best of circumstances, and for young farmers starting out with student debt the prospects are even worse). At the moment, with real estate developers making bank on new developments, GDP rising when food is transported across national borders, and the fossil fuel industry still benefiting from long distances between growers and consumers — as bizarre as that sounds in our burning world — there remains little incentive for those in power to change this system. Fortunately, a number of organizations and local governments have taken on the difficult work of exploring alternative models of land ownership, setting up farmland trusts, and giving low or no interest loans to beginning farmers. Models like Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), in which community members pay for food shares at the start of a growing season, provide farmers with critical financial safety nets that help them stay afloat.

Gaining rights to water and finding land not contaminated by industry can present further obstacles. So can overcoming expectations like, “I’m entitled to eat fresh strawberries in winter no matter where I live” — when in fact, eating seasonal, locally adapted produce is likely to lead to a higher quality overall diet, especially for those willing to take it on as a creative challenge. The same goes for countering statements like “organic agriculture is less productive,” or “small farms cannot feed the world.” While the first may sometimes appear to be true if you’re comparing organic versus conventional large scale production of the same crop, the statistics are usually cherry-picked to support corporate interests, and the whole conversation shifts if you expand your discussion to include different agricultural models — like highly diversified, integrated systems. When it comes to comparing large versus small farms, a lot of data is already in: small or medium family farms produce over 80% of the world’s food, using only 12% of the agricultural land. A huge problem lies in the fact that, to a very alarming extent, big agribusiness funds agricultural research in universities.

Then there are the challenges of obtaining local farming knowledge, particularly in regions where most people left the land long ago. Finally, there is the difficulty of overcoming stigmas, as Hou Xueying had to do, against working the land — fighting the idea that a farming life is “backward” and not modern — following these ideas to their source and cutting them off at the roots. We can only hope that as new food cultures take shape, and old ones evolve the world over, this process is able to spread and grow of its own accord.

~~~

Fortunately, this growth has already begun.

People around the world are hard at work creating diverse, living versions of the farms of the future. As a way of life, it would be nice to think that it could really catch on, and one day be accessible to most of us. We’ll just need to continue fighting for access, giving one another support, unearthing the solid, tangible proof that a local food future is real, and not some fantasy we’ll soon abandon, a vague dream of what might have been, that we talk about in bitter tones while the robots get on with the planting.

For more local food inspiration, see Local Futures’ curated collection of short films on food and farming.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Isabel Marlens is a Special Projects Coordinator for Local Futures. She studied Ecology and English Literature at Bennington College, has a Permaculture Design Certificate from Quail Springs Permaculture, and has done native plant conservation and education, forest ecology research, and research and writing for various documentary films and online publications in the areas of social and environmental justice.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 12, 2018 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives

by Frances Moore Lappé / Local Futures

People yearn for alternatives to industrial agriculture, but they are worried. They see large-scale operations relying on corporate-supplied chemical inputs as the only high-productivity farming model. Another approach might be kinder to the environment and less risky for consumers, but, they assume, it would not be up to the task of providing all the food needed by our still-growing global population.

Contrary to such assumptions, there is ample evidence that an alternative approach—organic agriculture, or more broadly “agroecology”—is actually the only way to ensure that all people have access to sufficient, healthful food. Inefficiency and ecological destruction are built into the industrial model. But, beyond that, our ability to meet the world’s needs is only partially determined by what quantities are produced in fields, pastures, and waterways. Wider societal rules and norms ultimately shape whether any given quantity of food produced is actually used to meet humanity’s needs. In many ways, how we grow food determines who can eat and who cannot—no matter how much we produce. Solving our multiple food crises thus requires a systems approach in which citizens around the world remake our understanding and practice of democracy.

Today, the world produces—mostly from low-input, smallholder farms—more than enough food: 2,900 calories per person per day. Per capita food availability has continued to expand despite ongoing population growth. This ample supply of food, moreover, comprises only what is left over after about half of all grain is either fed to livestock or used for industrial purposes, such as agrofuels.1

Despite this abundance, 800 million people worldwide suffer from long-term caloric deficiencies. One in four children under five is deemed stunted—a condition, often bringing lifelong health challenges, that results from poor nutrition and an inability to absorb nutrients. Two billion people are deficient in at least one nutrient essential for health, with iron deficiency alone implicated in one in five maternal deaths.2

The total supply of food alone actually says little about whether the world’s people are able to meet their nutritional needs. We need to ask why the industrial model leaves so many behind, and then determine what questions we should be asking to lead us toward solutions to the global food crisis.

Vast, Hidden Inefficiencies

The industrial model of agriculture—defined here by its capital intensity and dependence on purchased inputs of seeds, fertilizer, and pesticides—creates multiple unappreciated sources of inefficiency. Economic forces are a major contributor here: the industrial model operates within what are commonly called “free market economies,” in which enterprise is driven by one central goal, namely, securing the highest immediate return to existing wealth. This leads inevitably to a greater concentration of wealth and, in turn, to greater concentration of the capacity to control market demand within the food system.

Moreover, economically and geographically concentrated production, requiring lengthy supply chains and involving the corporate culling of cosmetically blemished foods, leads to massive outright waste: more than 40 percent of food grown for human consumption in the United States never makes it into the mouths of its population.3

The underlying reason industrial agriculture cannot meet humanity’s food needs is that its system logic is one of disassociated parts, not interacting elements. It is thus unable to register its own self-destructive impacts on nature’s regenerative processes. Industrial agriculture, therefore, is a dead end.

Consider the current use of water in agriculture. About 40 percent of the world’s food depends on irrigation, which draws largely from stores of underground water, called aquifers, which make up 30 percent of the world’s freshwater. Unfortunately, groundwater is being rapidly depleted worldwide. In the United States, the Ogallala Aquifer—one of the world’s largest underground bodies of water—spans eight states in the High Plains and supplies almost one third of the groundwater used for irrigation in the entire country. Scientists warn that within the next thirty years, over one-third of the southern High Plains region will be unable to support irrigation. If today’s trends continue, about 70 percent of the Ogallala groundwater in the state of Kansas could be depleted by the year 2060.4

Industrial agriculture also depends on massive phosphorus fertilizer application—another dead end on the horizon. Almost 75 percent of the world’s reserve of phosphate rock, mined to supply industrial agriculture, is in an area of northern Africa centered in Morocco and Western Sahara. Since the mid-twentieth century, humanity has extracted this “fossil” resource, processed it using climate-harming fossil fuels, spread four times more of it on the soil than occurs naturally, and then failed to recycle the excess. Much of this phosphate escapes from farm fields, ending up in ocean sediment where it remains unavailable to humans. Within this century, the industrial trajectory will lead to “peak phosphorus”—the point at which extraction costs are so high, and prices out of reach for so many farmers, that global phosphorus production begins to decline.5

Beyond depletion of specific nutrients, the loss of soil itself is another looming crisis for agriculture. Worldwide, soil is eroding at a rate ten to forty times faster than it is being formed. To put this in visual terms, each year, enough soil is washed and blown from fields globally to fill roughly four pickup trucks for every human being on earth.6

The industrial model of farming is not a viable path to meeting humanity’s food needs for yet another reason: it contributes nearly 20 percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, even more than the transportation sector. The most significant emissions from agriculture are carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. Carbon dioxide is released in deforestation and subsequent burning, mostly in order to grow feed, as well as from decaying plants. Methane is released by ruminant livestock, mainly via their flatulence and belching, as well as by manure and in rice paddy cultivation. Nitrous oxide is released largely by manure and manufactured fertilizers. Although carbon dioxide receives most of the attention, methane and nitrous oxide are also serious. Over a hundred-year period, methane is, molecule for molecule, 34 times more potent as a heat-trapping gas, and nitrous oxide about 300 times, than carbon dioxide.7

Our food system also increasingly involves transportation, processing, packaging, refrigeration, storage, wholesale and retail operations, and waste management—all of which emit greenhouses gases. Accounting for these impacts, the total food system’s contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, from land to landfill, could be as high as 29 percent. Most startlingly, emissions from food and agriculture are growing so fast that, if they continue to increase at the current rate, they alone could use up the safe budget for all greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.8

These dire drawbacks are mere symptoms. They flow from the internal logic of the model itself. The reason that industrial agriculture cannot meet the world’s needs is that the structural forces driving it are misaligned with nature, including human nature.

Social history offers clear evidence that concentrated power tends to elicit the worst in human behavior. Whether for bullies in the playground or autocrats in government, concentrated power is associated with callousness and even brutality not in a few of us, but in most of us.9 The system logic of industrial agriculture, which concentrates social power, is thus itself a huge risk for human well-being. At every stage, the big become bigger, and farmers become ever-more dependent on ever-fewer suppliers, losing power and the ability to direct their own lives.

The seed market, for example, has moved from a competitive arena of small, family-owned firms to an oligopoly in which just three companies—Monsanto, DuPont, and Syngenta—control over half of the global proprietary seed market. Worldwide, from 1996 to 2008, a handful of corporations absorbed more than two hundred smaller independent companies, driving the price of seeds and other inputs higher to the point where their costs for poor farmers in southern India now make up almost half of production costs.10 And the cost in real terms per acre for users of bio-engineered crops dominated by one corporation, Monsanto, tripled between 1996 and 2013.

Not only does the industrial model direct resources into inefficient and destructive uses, but it also feeds the very root of hunger itself: the concentration of social power. This results in the sad irony that small-scale farmers—those with fewer than five acres—control 84 percent of the world’s farms and produce most of the food by value, yet control just 12 percent of the farmland and make up the majority of the world’s hungry.11

The industrial model also fails to address the relationship between food production and human nutrition. Driven to seek the highest possible immediate financial returns, farmers and agricultural companies are increasingly moving toward monocultures of low-nutrition crops such as corn—the dominant US crop—that are often processed into empty-calorie “food products.” As a result, from 1990 to 2010, growth in unhealthy eating patterns outpaced dietary improvements in most parts of the world, including the poorer regions. Most of the key causes of non-communicable diseases are now diet-related, and by 2020, such diseases are predicted to account for nearly 75 percent of all deaths worldwide.12

A Better Alternative

What model of farming can end nutritional deprivation while restoring and conserving food-growing resources for our progeny? The answer lies in the emergent model of agroecology, often called “organic” or ecological agriculture. Hearing these terms, many people imagine simply a set of farming practices that forgo purchased inputs, relying instead on beneficial biological interactions among plants, microbes, and other organisms. However, agroecology is much more than that. The term as it is used here suggests a model of farming based on the assumption that within any dimension of life, the organization of relationships within the whole system determines the outcomes. The model reflects a shift from a disassociated to a relational way of thinking arising across many fields within both the physical and social sciences. This approach to farming is coming to life in the ever-growing numbers of farmers and agricultural scientists worldwide who reject the narrow productivist view embodied in the industrial model.

Recent studies have dispelled the fear that an ecological alternative to the industrial model would fail to produce the volume of food for which the industrial model is prized. In 2006, a seminal study in the Global South compared yields in 198 projects in 55 countries and found that ecologically attuned farming increased crop yields by an average of almost 80 percent. A 2007 University of Michigan global study concluded that organic farming could support the current human population, and expected increases without expanding farmed land. Then, in 2009, came a striking endorsement of ecological farming by fifty-nine governments and agencies, including the World Bank, in a report painstakingly prepared over four years by four hundred scientists urging support for “biological substitutes for industrial chemicals or fossil fuels.”13 Such findings should ease concerns that ecologically aligned farming cannot produce sufficient food, especially given its potential productivity in the Global South, where such farming practices are most common.

Ecological agriculture, unlike the industrial model, does not inherently concentrate power. Instead, as an evolving practice of growing food within communities, it disperses and creates power, and can enhance the dignity, knowledge, and the capacities of all involved. Agroecology can thereby address the powerlessness that lies at the root of hunger.

Applying such a systems approach to farming unites ecological science with time-tested traditional wisdom rooted in farmers’ ongoing experiences. Agroecology also includes a social and politically engaged movement of farmers, growing from and rooted in distinct cultures worldwide. As such, it cannot be reduced to a specific formula, but rather represents a range of integrated practices, adapted and developed in response to each farm’s specific ecological niche. It weaves together traditional knowledge and ongoing scientific breakthroughs based on the integrative science of ecology. By progressively eliminating all or most chemical fertilizers and pesticides, agroecological farmers free themselves—and, therefore, all of us—from reliance on climate-disrupting, finite fossil fuels, as well as from other purchased inputs that pose environmental and health hazards.

In another positive social ripple, agroecology is especially beneficial to women farmers. In many areas, particularly in Africa, nearly half or more of farmers are women, but too often they lack access to credit.14 Agroecology—which eliminates the need for credit to buy synthetic inputs—can make a significant difference for them.

Agroecological practices also enhance local economies, as profits on farmers’ purchases no longer seep away to corporate centers elsewhere. After switching to practices that do not rely on purchased chemical inputs, farmers in the Global South commonly make natural pesticides using local ingredients—mixtures of neem tree extract, chili, and garlic in southern India, for example. Local farmers purchase women’s homemade alternatives and keep the money circulating within their community, benefiting all.15

Besides these quantifiable gains, farmers’ confidence and dignity are also enhanced through agroecology. Its practices rely on farmers’ judgments based on their expanding knowledge of their land and its potential. Success depends on farmers’ solving their own problems, not on following instructions from commercial fertilizer, pesticide, and seed companies. Developing better farming methods via continual learning, farmers also discover the value of collaborative working relationships. Freed from dependency on purchased inputs, they are more apt to turn to neighbors—sharing seed varieties and experiences of what works and what does not for practices like composting or natural pest control. These relationships encourage further experimentation for ongoing improvement. Sometimes, they foster collaboration beyond the fields as well—such as in launching marketing and processing cooperatives that keep more of the financial returns in the hands of farmers.

Going beyond such localized collaboration, agroecological farmers are also building a global movement. La Via Campesina, whose member organizations represent 200 million farmers, fights for “food sovereignty,” which its participants define as the “right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods.” This approach puts those who produce, distribute, and consume food—rather than markets and corporations—at the heart of food systems and policies, and defends the interests and inclusion of the next generation.

Once citizens come to appreciate that the industrial agriculture model is a dead end, the challenge becomes strengthening democratic accountability in order to shift public resources away from it. Today, those subsidies are huge: by one estimate, almost half a trillion tax dollars in OECD countries, plus Brazil, China, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Russia, South Africa, and Ukraine.16 Imagine the transformative impact if a significant share of those subsidies began helping farmers’ transition to agroecological farming.

Any accurate appraisal of the viability of a more ecologically attuned agriculture must let go of the idea that the food system is already so globalized and corporate-dominated that it is too late to scale up a relational, power-dispersing model of farming. As noted earlier, more than three-quarters of all food grown does not cross borders. Instead, in the Global South, the number of small farms is growing, and small farmers produce 80 percent of what is consumed in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.17

The Right Path

When we address the question of how to feed the world, we need to think relationally—linking current modes of production with our future capacities to produce, and linking farm output with the ability of all people to meet their need to have nutritious food and to live in dignity. Agroecology, understood as a set of farming practices aligned with nature and embedded in more balanced power relationships, from the village level upward, is thus superior to the industrial model. This emergent relational model offers the promise of an ample supply of nutritious food needed now and in the future, and more equitable access to it.

Reframing concerns about inadequate supply is only the first step toward necessary change. The essential questions about whether humanity can feed itself well are social—or, more precisely, political. Can we remake our understanding and practice of democracy so that citizens realize and assume their capacity for self-governance, beginning with the removal of the influence of concentrated wealth on our political systems?

Democratic governance—accountable to citizens, not to private wealth—makes possible the necessary public debate and rule-making to re-embed market mechanisms within democratic values and sound science. Only with this foundation can societies explore how best to protect food-producing resources—soil, nutrients, water—that the industrial model is now destroying. Only then can societies decide how nutritious food, distributed largely as a market commodity, can also be protected as a basic human right.

This post is adapted from an essay originally written for the Great Transition Initiative.

Featured image: TompkinsConservation.org

Endnotes

1. Food and Agriculture Division of the United Nations, Statistics Division, “2013 Food Balance Sheets for 42 Selected Countries (and Updated Regional Aggregates),” accessed March 1, 2015, http://faostat3.fao.org/download/FB/FBS/E; Paul West et al., “Leverage Points for Improving Global Food Security and the Environment,” Science 345, no. 6194 (July 2014): 326; Food and Agriculture Organization, Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets (Rome: FAO, 2013), http://fao.org/docrep/018/al999e/al999e.pdf.

2. FAO, The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015: Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress (Rome: FAO, 2015), 8, 44, http://fao.org/3/a-i4646e.pdf; World Health Organization, Childhood Stunting: Context, Causes, Consequences (Geneva: WHO, 2013), http://www.who.int/nutrition/events/2013_ChildhoodStunting_colloquium_14Oct_ConceptualFramework

_colour.pdf?ua=1; FAO, The State of Food and Agriculture 2013: Food Systems for Better Nutrition (Rome: FAO, 2013), ix, http://fao.org/docrep/018/i3300e/i3300e.pdf.

3. Vaclav Smil, “Nitrogen in Crop Production: An Account of Global Flows,” Global Geochemical Cycles 13, no. 2 (1999): 647; Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40% of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill (Washington, DC: Natural Resources Defense Council, 2012), http://www.nrdc.org/food/files/wasted-food-IP.pdf.

4. United Nations Environment Programme, Groundwater and Its Susceptibility to Degradation: A Global Assessment of the Problem and Options for Management (Nairobi: UNEP, 2003), http://www.unep.org/dewa/Portals/67/pdf/Groundwater_Prelims_SCREEN.pdf; Bridget Scanlon et al., “Groundwater Depletion and Sustainability of Irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 24 (June 2012): 9320; David Steward et al., “Tapping Unsustainable Groundwater Stores for Agricultural Production in the High Plains Aquifer of Kansas, Projections to 2110,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 37 (September 2013): E3477.

5. Dana Cordell and Stuart White, “Life’s Bottleneck: Sustaining the World’s Phosphorus for a Food Secure Future,” Annual Review Environment and Resources 39 (October 2014): 163, 168, 172.

6. David Pimentel, “Soil Erosion: A Food and Environmental Threat,” Journal of the Environment, Development and Sustainability 8 (February 2006): 119. This calculation assumes that a full-bed pickup truck can hold 2.5 cubic yards of soil, that one cubic yard of soil weighs approximately 2,200 pounds, and that world population is 7.2 billion people.

7. FAO, “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use,” March 2014, http://fao.org/resources/ infographics/infographics-details/en/c/218650/; Gunnar Myhre et al., “Chapter 8: Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing,” in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013), 714, http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_Chapter08_FINAL.pdf.

8. Sonja Vermeulen, Bruce Campbell, and John Ingram, “Climate Change and Food Systems,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 37 (November 2012): 195; Bojana Bajželj et al., “Importance of Food-Demand Management for Climate Mitigation,” Nature Climate Change 4 (August 2014): 924–929.

9. Philip Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (New York: Random House, 2007).

10. Philip Howard, “Visualizing Consolidation in the Global Seed Industry: 1996–2008,” Sustainability 1, no. 4 (December 2009): 1271; T. Vijay Kumar et al., Ecologically Sound, Economically Viable: Community Managed Sustainable Agriculture in Andhra Pradesh, India (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009), 6-7, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSOCIALDEVELOPMENT/Resources/244362-1278965574032/CMSA-Final.pdf.

11. Estimated from FAO, “Family Farming Knowledge Platform,” accessed December 16, 2015, http://www.fao.org/family-farming/background/en/.

12. Fumiaki Imamura et al., “Dietary Quality among Men and Women in 187 Countries in 1990 and 2010: A Systemic Assessment,” The Lancet 3, no. 3 (March 2015): 132–142, http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/langlo/PIIS2214-109X%2814%2970381-X.pdf.

13. Jules Pretty et al., “Resource-Conserving Agriculture Increases Yields in Developing Countries,” Environmental Science & Technology 40, no. 4 (2006): 1115; Catherine Badgley et al., “Organic Agriculture and the Global Food Supply,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 22, no. 2 (June 2007): 86, 88; International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development, Agriculture at a Crossroads: International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2009).

14. Cheryl Doss et al., “The Role of Women in Agriculture,” ESA Working Paper No. 11-02 (working paper, FAO, Rome, 2011), 4, http://fao.org/docrep/013/am307e/am307e00.pdf.

15. Gerry Marten and Donna Glee Williams, “Getting Clean: Recovering from Pesticide Addiction,” The Ecologist (December 2006/January 2007): 50–53,http://www.ecotippingpoints.org/resources/download-pdf/publication-the-ecologist.pdf.

16. Randy Hayes and Dan Imhoff, Biosphere Smart Agriculture in a True Cost Economy: Policy Recommendations to the World Bank (Healdsburg, CA: Watershed Media, 2015), 9, http://www.fdnearth.org/files/2015/09/FINAL-Biosphere-Smart-Ag-in-True-Cost-Economy-FINAL-1-page-display-1.pdf.

17. Matt Walpole et al., Smallholders, Food Security, and the Environment (Nairobi: UNEP, 2013), 6, 28, http://www.unep.org/pdf/SmallholderReport_WEB.pdf.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 22, 2017 | Building Alternatives

by Jason Hickel / Local Futures

The economist Branko Milanovic recently wrote a blog post titled “The illusion of degrowth in a poor and unequal world.” He penned it, he says, following a conversation he had with a proponent of degrowth.

As it turns out, that proponent was me.

First, let me say that I have a lot of respect for Milanovic’s work on inequality. I cite him all the time. But unfortunately he doesn’t have a strong grasp of degrowth. Let’s look at his argument in detail:

Milanovic rejects degrowth because he believes it is unfeasible. He notes, correctly, that if we were to cap global GDP at its present level then the only way to eradicate poverty would be through redistribution: reduce the income share of the richest and shift it to the poorest. He thinks this is a terrible idea. If we bring all of the poorest up to $5,500 per person per year (the global mean income), then in order to stay within the GDP cap everyone above this level (almost all of whom live in the West) will have to take an income cut, with the richest taking the biggest hit. This would also require “gradual and sustained reduction of production” in rich nations, with economic activity slashed to one-third of its present size.

Milanovic calls this “the immiseration of the West,” and he dismisses it as “not even vaguely likely to find any political support anywhere.” Forget about it, he says; we need growth. Let’s focus instead on reducing our consumption of emissions-intensive goods and services by taxing them, and “think about how new technologies can be harnessed to make the world more environmentally friendly.”

This is exactly the argument that Milanovic articulated during our email exchange. I responded by pointing out some of its problems and by gesturing in the direction of relevant literature he might find useful, but he never replied. Apparently he had made up his mind, and was ready to take a public stance. So let me publicly lay out some thoughts in response.

Degrowth does not call for immiseration.

Milanovic’s argument is leveled against a straw man. If he had read the literature on degrowth, he would know that it does not call for immiseration.

Imagine cutting the GDP per capita of the US down to less than half its present size, in real terms. This might sound horrible on the face of it, but it would be equivalent to US GDP per capita in the 1970s. Folks who lived through the 70s remember them as heady days. And the poverty rate was lower back then – and happiness levels higher – than now. Real wages were higher, too. The only difference is that people consumed less unnecessary stuff. It’s not clear why Milanovic considers this to be so dreadful.

There are lots of other examples we might cite. The GDP per capita of Europe is 40% lower than that of the US. I live in Europe: it is hardly a dystopia. Costa Rica has a GDP per capita that is one-fifth that of the US, but it has life expectancy that outstrips that of Americans, and levels of happiness that rival those of Scandinavians. All of these examples prove that we don’t need ecology-busting levels of income and consumption to live good lives. The literature is very clear on this: just check out Tim Jackson’s Prosperity Without Growth, Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful, Firamonti’s Well-Being Economy, Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, or anything by Giorgos Kallis.

In fact, degrowth calls for human flourishing.

Proponents of degrowth don’t just want to redistribute income within the already-existing economy, as Milanovic wrongly assumes. We want to redistribute income in a way that improves social goods, like universal healthcare and education, which are key to reducing poverty and improving people’s lives. Not only are universal systems cheaper and more efficient at achieving these outcomes than private ones (healthcare in the UK costs one-third that in the US), but having them in place also improves the “purchasing power” (if you will) of incomes. Think about it: if Americans didn’t have to pay exorbitant prices for healthcare and higher education, they would need a lot less income to live good lives.

In this way, decommoditizing key social goods is a good way to take pressure off the planet. We can even extend this insight to housing. Housing in London, where I live, is obscenely expensive. Most people spend half of their income just to keep a roof over their heads. If the housing stock was even partially decommoditized, Londoners would be able to work much less than they do now – producing less unnecessary stuff in the process – and still have the same quality of life that they presently enjoy.

Degrowth demands a different kind of economy.

Of course, all of this requires that we shift to a different kind of economy altogether – one that supports and promotes the commons, and focuses on improving human well-being rather than only on improving monetary incomes. This is where Milanovic makes a key mistake. The point of degrowth is to reduce the material throughput of the economy not by shrinking the existing one (which would surely be painful), but by shifting to a better one: one more in line with our planet’s ecology.

To be honest, I’m surprised that Milanovic didn’t jump on a more obvious issue, namely, that if our economy stopped growing it would more or less immediately bump up against financial crisis. Why? Because our economy is shot through with debt, and debt comes with interest; and because interest is a compound function, all of us have to run around producing more and more each year, shoveling money into the pockets of the rich, just to pay it down. If we halt the rat race, the whole house of cards will collapse. And it doesn’t help that, given fractional reserve banking, our money system itself is based on debt.

So if we want to throw off the tyranny of growth we’ll have to have some kind of debt jubilee, and get rid of our debt-based money system. These necessary changes are not compatible with the logic of the existing economy. We need a different kind of economy.

Trying to eradicate poverty through growth is going to immiserate everyone.

Milanovic rejects degrowth and claims that we should stick with the existing plan for eradicating poverty: more growth. But he hasn’t thought through the implications of this.

We need to remember that the existing distribution of global growth is skewed heavily toward the rich. David Woodward points out that even during the most equitable period of the past few decades, only 5% of new income from annual global growth went to the poorest 60% of humanity. At this rate of trickle-down, it will take more than 100 years to get everyone above $1.25 per day, and 207 years to get everyone above $5 per day. And in order to get there we will have to grow the global economy to 175 times its present size.

That’s 175 times more extraction, production and consumption than we’re already doing. And to reach Milanovic’s minimum of $5,500 per year would require much more than this by far. Even if this kind of growth was physically possible, it would cause catastrophic ecological crisis that would more than wipe out any gains made against poverty. Redistribution may not seem feasible to Milanovic, but the existing plan is much less feasible still.

Yes, one might argue that we can improve the share of growth that goes to the poorest. That would be an important first step, to be sure. But as long as the rest of the world continues to grow, increasing aggregate material throughput and emissions, we’re going to be in trouble. In fact, we’re already in trouble even at existing levels of throughput and emissions, and we can see it all around us: rapid deforestation, collapsing fish stocks, mass species extinction, soil depletion and of course climate change, with the poorest getting hit hardest by far.

Milanovic believes we can reign these problems in with more “environmentally friendly” growth. But that’s a pipe dream. And this brings me to my last point:

Green growth is not a thing.

Milanovic likes to run numbers, so let’s look at some.

First, emissions. As we know, emissions rise more or less in line with GDP growth. Climate scientists Anderson and Bows (2011) say that if we want to stay under 2°C, rich nations will have to reduce emissions by 8-10% per year. Since the dominant assumption in the literature is that reductions greater than 3-4% per year are incompatible with a growing economy (Stern 2006; UK CCC 2008; Hof and Vuuren 2009), they conclude that the only way to prevent catastrophic climate change is by reducing economic activity.

This conclusion is in keeping with that of other studies (e.g., Raftery et al 2017). Keep in mind that the existing rate of decarbonization is only about 1.6% per year. Schandl et al (2016) suggest that some rich nations might be able to bump this up to a maximum of 4.7% per year in the future if they roll out a high and fast-rising carbon price, and somehow manage to double their material efficiency. But even this extreme best-case scenario is a far cry from the 10% we need.

Of course, some think we’ll be able to buy time by deploying new technology, the most “promising” being bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). But there is a growing consensus that BECCS won’t work. The technology has never been proven at scale, and it probably won’t appear in time to prevent us blowing the 2°C budget (which is only 19 years away). Even if it did, it would require that we create plantations for biofuel equivalent to three times the size of India. Think about the consequences for the global food supply: hardly good for poverty-reduction.

But let’s be charitable and assume that Milanovic is right – that we can somehow manage to reduce emissions by reducing the consumption of high-emission goods and services. Of course, in order to keep the economy growing, we would still have to increase the consumption of other goods and services. Milanovic sees no problem with this. I don’t know why. Maybe he believes that new technology will make us more efficient, and we will be able to grow the GDP without growing material throughput.

This is known as “absolute decoupling”. But unfortunately absolute decoupling is not a thing. Take two recent studies:

Ward et al (2016) find that even the most optimistic projections of efficiency improvements yield no absolute decoupling in the medium and long term. The authors state: “this result is a robust rebuttal to the claim of absolute decoupling”; “decoupling of GDP growth from resource use, whether relative or absolute, is at best only temporary. Permanent decoupling (absolute or relative) is impossible… because the efficiency gains are ultimately governed by physical limits.”

Schandl et al (2016) find the same thing. Even in their best-case scenario projection, global material consumption still grows steadily. The authors conclude: “Our research shows that while some relative decoupling can be achieved in some scenarios, none would lead to an absolute reduction in energy or materials footprint.”

* * *

I laid all this evidence out for Milanovic, but he didn’t engage with it. Instead, he chooses to believe, against all available evidence, that we can continue with indefinite exponential GDP growth without causing ecological collapse.

Milanovic accuses us – incorrectly – of wanting “the immiseration of the West” in order to eradicate poverty in the global South. But his blind faith in growth, and his implicit denial of scientific evidence, is sure to lead to ecological collapse – entrenching the misery of the poor and immiserating the rest of us in the process.

**NOTE: Milanovic responded to this post by insisting that degrowth is not politically feasible. But I disagree: people are ready for a new economy. See my argument here.

This essay originally appeared as Why Branko Milanovic is wrong about de-growth, on Jason Hickel’s blog. For permission to repost this and other Local Futures blog posts, contact: info@localfutures.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 29, 2017 | Building Alternatives

Featured image: Monique Quesada

by Jason Hickel / Local Futures

Earlier this summer, a paper published in the journal Nature captured headlines with a rather bleak forecast. Our chances of keeping global warming below the 2C danger threshold are very, very small: only about 5%. The reason, according to the paper’s authors, is that the cuts we’re making to greenhouse gas emissions are being cancelled out by economic growth.

In the coming decades, we’ll be able to reduce the carbon intensity of the global economy by about 1.9% per year, if we make heavy investments in clean energy and efficient technology. That’s a lot. But as long as the economy keeps growing by more than that, total emissions are still going to rise. Right now we’re ratcheting up global GDP by 3% per year, which means we’re headed for trouble.

If we want to have any hope of averting catastrophe, we’re going to have to do something about our addiction to growth. This is tricky, because GDP growth is the main policy objective of virtually every government on the planet. It lies at the heart of everything we’ve been told to believe about how the economy should work: that GDP growth is good, that it’s essential to progress, and that if we want to improve human wellbeing and eradicate poverty around the world, we need more of it. It’s a powerful narrative. But is it true?

Maybe not. Take Costa Rica. A beautiful Central American country known for its lush rainforests and stunning beaches, Costa Rica proves that achieving high levels of human wellbeing has very little to do with GDP and almost everything to do with something very different.

Every few years the New Economics Foundation publishes the Happy Planet Index – a measure of progress that looks at life expectancy, wellbeing and equality rather than the narrow metric of GDP, and plots these measures against ecological impact. Costa Rica tops the list of countries every time. With a life expectancy of 79.1 years and levels of wellbeing in the top 7% of the world, Costa Rica matches many Scandinavian nations in these areas and neatly outperforms the United States. And it manages all of this with a GDP per capita of only $10,000, less than one-fifth that of the US.

In this sense, Costa Rica is the most efficient economy on earth: it produces high standards of living with low GDP and minimal pressure on the environment.

How do they do it? Professors Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea argue that it’s all down to Costa Rica’s commitment to universalism: the principle that everyone – regardless of income – should have equal access to generous, high-quality social services as a basic right. A series of progressive governments started rolling out healthcare, education and social security in the 1940s and expanded these to the whole population from the 50s onward, after abolishing the military and freeing up more resources for social spending.

Costa Rica wasn’t alone in this effort, of course. Progressive governments elsewhere in Latin America made similar moves, but in nearly every case the US violently intervened to stop them for fear that “communist” ideas might scupper American interests in the region. Costa Rica escaped this fate by outwardly claiming to be anti-communist and – horribly – allowing US-backed forces to use the country as a base in the contra war against Nicaragua.

The upshot is that Costa Rica is one of only a few countries in the global South that enjoys robust universalism. It’s not perfect, however. Relatively high levels of income inequality make the economy less efficient than it otherwise might be. But the country’s achievements are still impressive. On the back of universal social policy, Costa Rica surpassed the US in life expectancy in the late 80s, when its GDP per capita was a mere tenth of America’s.

Today, Costa Rica is a thorn in the side of orthodox economics. The conventional wisdom holds that high GDP is essential for longevity: “wealthier is healthier”, as former World Bank chief economist Larry Summers put it in a famous paper. But Costa Rica shows that we can achieve human progress without much GDP at all, and therefore without triggering ecological collapse. In fact, the part of Costa Rica where people live the longest, happiest lives – the Nicoya Peninsula – is also the poorest, in terms of GDP per capita. Researchers have concluded that Nicoyans do so well not in spite of their “poverty”, but because of it – because their communities, environment and relationships haven’t been plowed over by industrial expansion.

All of this turns the usual growth narrative on its head. Henry Wallich, a former member of the US Federal Reserve Board, once pointed out that “growth is a substitute for redistribution”. And it’s true: most politicians would rather try to rev up the GDP and hope it trickles down than raise taxes on the rich and redistribute income into social goods. But a new generation of thinkers is ready to flip Wallich’s quip around: if growth is a substitute for redistribution, then redistribution can be a substitute for growth.

Costa Rica provides a hopeful model for any country that wants to chart its way out of poverty. But it also holds an important lesson for rich countries. Scientists tell us that if we want to avert dangerous climate change, high-consuming nations are going to have to scale down their bloated economies to get back in sync with the planet’s ecology, and fast. A widely-cited paper by scientists at the University of Manchester estimates it’s going to require downscaling of 4-6% per year.

This is what ecologists call “de-growth”. This calls for redistributing existing resources and investing in social goods in order to render growth unnecessary. Decommoditizing and universalizing healthcare, education and even housing would be a step in the right direction. Another would be a universal basic income – perhaps funded by taxes on carbon, land, resource extraction and financial transactions.

The opposite of growth isn’t austerity, or depression, or voluntary poverty. It is sharing what we already have, so we won’t need to plunder the earth for more.

Costa Rica proves that rich countries could theoretically ease their consumption by half or more while maintaining or even increasing their human development indicators. Of course, getting there would require that we devise a new economic system that doesn’t require endless growth just to stay afloat. That’s a challenge, to be sure, but it’s possible.

After all, once we have excellent healthcare, education, and affordable housing, what will endlessly more income growth gain us? Maybe bigger TVs, flashier cars, and expensive holidays. But not more happiness, or stronger communities, or more time with our families and friends. Not more peace or more stability, fresher air or cleaner rivers. Past a certain point, GDP gains us nothing when it comes to what really matters. In an age of climate change, where the pursuit of ever more GDP is actively dangerous, we need a different approach.

This essay originally appeared in The Guardian.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 4, 2017 | Building Alternatives, Strategy & Analysis

by Helena Norberg-Hodge / Local Futures

While we mourn the tragedy that fear, prejudice and ignorance “trumped” in the US Presidential election, now is the time to go deeper and broader with our work. There is a growing recognition that the scary situation we find ourselves in today has deep roots.

To better understand what happened—and why—we need to broaden our horizons. If we zoom out a bit, it becomes clear that Trump is not an isolated phenomenon; the forces that elected him are largely borne of rising economic insecurity and discontent with the political process. The resulting confusion and fear, unaddressed by mainstream media and politics, has been capitalized on by the far-right worldwide.

Almost everywhere in the world, unemployment is increasing, the gap between rich and poor is widening, environmental devastation is worsening, and a spiritual crisis—revealed in addiction, domestic assaults, and suicide—is deepening.

From a global perspective it becomes apparent that these many crises—to which the rise of right-wing sentiments is intimately connected—share a common root cause: a globalized economic system that is devastating not only ecosystems, but also the lives of hundreds of millions of people.

How did we end up in this situation?

Over the last three decades, governments have unquestioningly embraced “free trade” treaties that have allowed ever larger corporations to demand lower wages, fewer regulations, more tax breaks and more subsidies. These treaties enable corporations to move operations elsewhere or even to sue governments if their profit-oriented demands are not met. In the quest for “growth,” communities worldwide have had their local economies undermined and have been pulled into dependence on a volatile global economy over which they have no control.

Corporate rule is not only disenfranchising people worldwide, it is fueling climate change, destroying cultural and biological diversity, and replacing community with consumerism. These are undoubtedly scary times. Yet the very fact that the crises we face are linked can be the source of genuine empowerment. Once we understand the systemic nature of our problems, the path towards solving them—simultaneously—becomes clear.

Trade unions, environmentalists and human rights activists formed a powerful anti-trade treaty movement long before Trump came on the scene. And his policies already show that he is about strengthening corporate rule, rather than reversing it.

Re-regulating global businesses and banks is a prerequisite for genuine democracy and sustainability, for a future that is shaped not by distant financial markets but by society. By insisting that business be place-based or localized, we can start to bring the economy home.

Around the world, from the USA to India, from China to Australia, people are reweaving the social and economic fabric at the local level and are beginning to feel the profound environmental, economic, social and even spiritual benefits. Local business alliances, local finance initiatives, locally-based education and energy schemes, and, most importantly, local food movements are springing up at an exponential rate.

As the scale and pace of economic activity are reduced, anonymity gives way to face-to-face relationships, and to a closer connection to Nature. Bonds of local interdependence are strengthened, and a secure sense of personal and cultural identity begins to flourish. All of these efforts are based on the principle of connection and the celebration of diversity, presenting a genuine systemic solution to our global crises as opposed to the fear-mongering and divisiveness of the dominant discourse in the media.

Moreover, localized economies boost employment not by increasing consumption, but by relying more on human labor and creativity and less on energy-intensive technological systems—thereby reducing resource use and pollution. By redistributing economic and political power from corporate monopolies to millions of small businesses, localization revitalizes the democratic process, re-rooting political power in community.

The far-reaching solution of a global to local shift can move us beyond the left-right political theater to link hands in a diverse and united people’s movement for secure, meaningful livelihoods and a healthy planet.

Republished with permission of Local Futures. For permission to repost this or other entries on the Economics of Happiness Blog, please contact info@localfutures.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 9, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health, Building Alternatives

by John Boik, PhD / Local Futures

It’s not often that a scientist gets to use the words love, creativity, and wisdom in a paper, especially when writing about economics. Perhaps that’s because economics, the dismal science, is obsessed with dismal systems – make that abysmal systems, relative to need.

To be clear, I’m not speaking of the specific policies of the US, the EU, China, the World Bank or others. I’m speaking of dominant economic systems as wholes – especially their underlying conceptual models (macro and micro) and the worldviews upon which they are based.

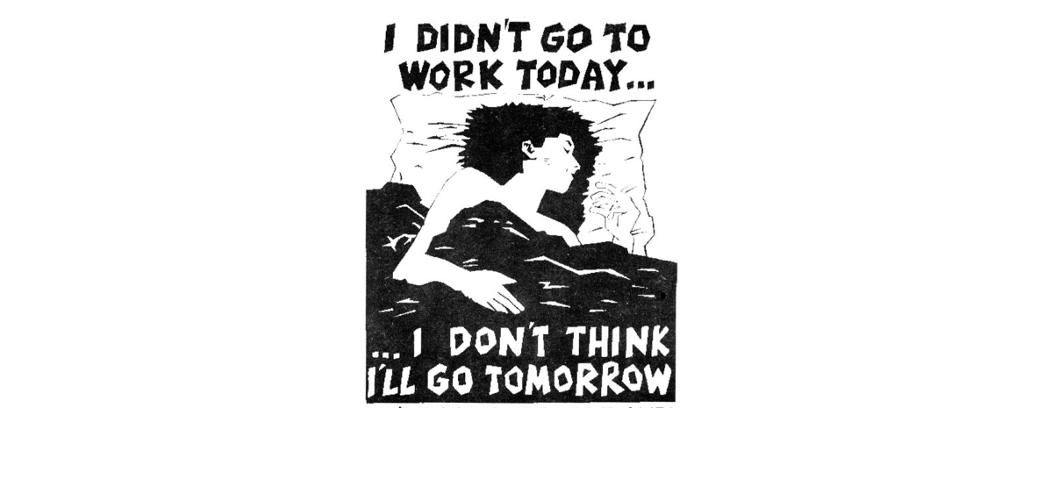

A human has only so many minutes in life. Time is the bedrock scarcity. If a person isn’t doing something meaningful in a given moment, he’s doing something less than meaningful. He’s wasting at least some of his potential. By meaningful, I don’t mean productive, in an economic sense. I mean important to the person, to her own wellbeing. The Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef identifies nine categories of human need: subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity, and freedom. Others might make a slightly different list, but the important concept is that meaning stems from addressing real human needs.

It’s not that we should be doing something meaningful with our time, it’s that we want to. We want to express and receive affection, for example, and to fulfill the other eight needs. We want to, that is, unless external pressures so exhaust, distract, distort, or confuse us that we lose touch with who we are.

Current economic systems are dismal-abysmal because they waste our precious time. As a case in point, only 13 percent of workers worldwide are engaged in their jobs. This means, in effect, that 87 percent of workers feel more or less forced to go to work. Short of force, why would someone spend half their waking hours (or more), day after day, doing something that didn’t engage them?

Except for receiving a paycheck, it appears that most workers don’t really care about their jobs. That’s not surprising. Work doesn’t count as a real human need. It’s only a vehicle by which some needs can be (but for most people aren’t) met. Work doesn’t meet our needs because economic systems, as they exist, didn’t evolve to fulfill the real needs of ordinary people. They evolved largely under pressures exerted by powerful people and groups who wanted to maintain and expand their own privileges.

Suppose that we pause to reevaluate. Using insights from psychology, environmental sciences, public health, complex systems science, sociology, and other fields – that is, using as clear and scientifically sound a picture as we can muster of what humans and natural environments actually need in order to thrive – we can ask ourselves the following question: What economic system designs, out of all conceivable ones, might be among the best at helping us meet real needs?

Strange as it might sound, this question is rarely asked in academia, the science and technology sector, or elsewhere. Or if it is asked, the investigation usually lacks imagination. Surely we can move beyond a discussion of capitalism vs. socialism, as if these were the only two possibilities. A wide-open, largely unexplored space of interesting, potentially viable systems exists.

In my recent paper, “Optimality of Social Choice Systems: Complexity, Wisdom, and Wellbeing Centrality,” I call on the academic community, as well as the science and technology sector, to begin a broad exploration in partnership with other segments of society into what optimality means with respect to economic and political system design. I term this nascent program wellbeing centrality, due to the central role that the elevation of wellbeing would play in systems that help us to fulfill real needs.

Viewed abstractly, economic and political systems are problem-solving systems. One could call them technologies of a sort. As such, they are subject to scientific inquiry and engineering innovation aimed at discovering new designs that improve problem-solving capacity. Further, if we seek ideas for new designs, we don’t have to look far. Nature provides a blueprint.

From a complex systems science perspective, the environment is replete with successful problem-solving systems (cells, organisms, immune systems, ecosystems, and so on). Although all look different physically, successful systems tend to exhibit similar underlying mathematical properties. That is, nature has hit upon a good problem-solving approach, and repeats it widely. If we wish our problem-solving systems to be successful, to be as good as they can be, we might want to pay close attention to what nature does.

Moreover, we can view the nine needs Max-Neef identifies as gifts of nature, stemming from eons of evolution over countless ancestral species, to help us focus on and solve problems that matter. Our need to express and receive affection, for example, is also responsible, in part, for our tendency to seek cooperation in solving difficult problems.

In short, “good” economic systems would produce economies of meaning that help us to help one another live meaningful lives—to meet real needs and solve problems that matter.