by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 16, 2016 | Building Alternatives

by David Fleming and Shaun Chamberlin

This originally appeared in Local Futures

What follows are some excerpts from the late David Fleming’s Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2016). The excerpts have been chosen by the book’s editor, Shaun Chamberlin. Extensive references are given in the dictionary itself, but are omitted here.

Localisation. Localisation stands, at best, at the limits of practical possibility, but it has the decisive argument in its favour that there will be no alternative.

Does that mean the end of travel? On the contrary, it means the end of mass dislocation – and the recovery of place. Almost wherever you go in the market economy, you find yourself in the same place – in the globalised market with its shared banality, its fullness; at the end of every lane is a busy road and a housing estate like the one at the beginning of it. You cannot get out of a globalised world, because there is no out. Localisation means the protection of distinctiveness: when you are out, you are somewhere else, in a different in.

Travel now finds its purpose, taking you to a place which is not in essentials identical to the one you have left, but to one that is interesting and finds you interesting, that wants to hear your song, that dances to a different tune.

See also: Delocalisation, Local Wisdom, Presence, Scale

Needs and Wants. A distinction between needs and wants has been made by many critics in the green movement and its predecessors, who have argued that consumption in response to our needs is justifiable and sustainable, but consumption in response to our wants is not.

Yet this notion that needs are good and wants bad does not survive inspection. For the anthropologists Douglas and Isherwood, it is a “curious moral split [that] appears under the surface of most economists’ thoughts on human needs”. Lean Logic argues that those economists have it somewhat back-to-front.

The heaviest burden of the modern economy, by far, is that imposed by its own elaborations. Any large-scale economy requires massive infrastructures and material flows just to support itself and keep existing. Such sprawling industrial economies have massively multiplied our needs, our ‘regrettable necessities’. Regardless of whether we want them, we need the sewage systems, heavy-goods transport, police-forces… Given the substantial scale of the task of feeding, raising and schooling a suburban family, and the increasing challenge of such routine needs as finding a post office, many of us undoubtedly need cars. The collapse of local self-reliance was both the cause and the effect of the massive elaboration of transport, and when that need can no longer be met, its life-sustaining function will be bitterly recognised.

It is, then, the elaboration of needs by large-scale industrial life that causes the trouble. Our wants are squeezed-out, much-missed and light by comparison, not least because they often involve labour-intensive crafts and services – pianists, craftsmen, dress-makers, waitresses, gardeners with minimum environmental impact. Some wants are also needs, of course, and they cannot be cleanly separated, but if we focus our efforts on finding a way, under the stresses of the climacteric, of achieving a substantial and rapid liquidation of our needs, we will be getting somewhere.

See also: Growth, Intentional Waste, Invisible Goods, Lean Economics, Scale, Slack

No Alternative, The Fallacy of. (1) The fallacy that there is no alternative (but you may not have looked hard enough). (2) The fallacy that, because there is no alternative to the particular strategy that is being discussed, that strategy must be feasible. Example: It is argued that the other big energy options are not going to provide solutions in the future, and that therefore the solution is a vast expansion of nuclear energy. But this is a non sequitur: the lack of feasibility of the other options tells us nothing about whether an expansion of nuclear power is feasible or not.

Peasant. A person practicing small-scale, mixed, energy-efficient, fertility-conserving farming designed chiefly for local subsistence. It is integrated into local culture. It is the defining practice of the community. This model of farming, however, became briefly obsolete in the market economy, with its abundant cheap energy, enabling a different one to develop which did not need to supply its own energy and sustain its own fertility.

Peasant farming is a skilled and efficient way of sustaining food production within the limits of the ecology. It is an eco-ethic, sustaining the measured synergy with nature that we find in Tao philosophy. It has the five properties of resilience.

But it has a flaw. It is highly productive, so it yields a surplus, and this is a tempting resource for the gradual evolution of an urban civic society, with its unstoppable implications of growth, hubris and trouble. Is there a way of learning from that dismal cycle, and sustaining, instead, a localised, community-based, decentralised society, without the seeds of its own destruction…?

Place. Space whose local narrative can still be heard, and could be heard again, given the chance. Place is the practical, located, tangible, bounded setting which protects us from abstractions, generalities and ideologies and opens the way to thinking as discovery. On this scale, there is elegance, and some relief from the need to be right, for if you are wrong, the small scale of place allows for revision and repair, supported by conversation.

Place is the endangered habitat of our species.

See also: County, Harmless Lunatic, Home, Identity, Localisation, Parish, Practice, Proximity Principle, Regrettable Necessities, Scale, Transition

Protection. The act of caring for something that you value, or for which you are responsible – it is a deep behaviour which, in some senses, is shared by all living things. It is widely supposed to be a good thing, except in the case of economies, which are required to dance to the single tune of perpetual competition. True, natural selection is a condition of all living things, too. But species with less intelligence than ours use both. It is time we caught up.

Lean Economics is about protecting the right of local economies to proceed on a different basis.

On such matters, market economics is far from neutral. It takes the view that the competitive market is the only sound basis for economy, politics and culture, and it advocates its case with evangelical conviction: if there is a society somewhere which is not based on the market, it needs to be saved.

In a taut, competitive, growing market, it is true that protectionism is not a good idea. …

But, of course, there are circumstances in which free, unprotected trade is not what an economy needs, and we are coming to a time when they can be discussed without inviting derision. Competitive free trade comes with a commitment to growth, i.e. to the rubbing out of diversity and local self-reliance, to resource-depletion, pollution, the loss of social capital and resilience – and eventual collapse. It is too late to consider protection against these things; the damage has already been done. But protection of what is left of indigenous food production and steps toward local self-reliance and reduced dependence on fossil fuels for every aspect of food production would be rational.

See also: Local Currency, Nation

System-Scale Rule. The key rule governing systems-design: large-scale problems do not require large-scale solutions; they require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework.

Time, Fallacies of.

The Permanent Present. The fallacy which gives undue emphasis to the present when considering an option with long-term consequences. Examples include arguments that our present ability to import food justifies permanent burial of agricultural land under new housing, that joining the Eurozone is justified by today’s low interest rates there, that the state of the jobs market at the moment calls for migrant labour, that the current price of oil opens the way to a long-term expansion of air travel. This presumption of a constant present is a leading symptom of the dementia that afflicts the judgment of governments – dementia absens: the patient is so elevated, so far removed from ordinary life, so taken up with a global vision, so protected by experts, so busy, so short of sleep, and so absent, that he or she has no sense of time or place. (Abstraction, Presence).

And there is a risk that the values of the present may crowd out all other values. The question, “What is right?”, short-circuits to the answer, “Whatever is now”.

The Irrelevant Past. An argument that affirms that now is a special case in that the present has achieved standards of reason and ethics which have not been available before. The fallacy typically cites the fact that this is the twenty-first century as proof that the argument is correct:

“By the end of the 20th century, the independent sector had emerged pre-eminent in the British education system but the only vision the independent sector has today remains entrenched in the 20th century… We need new vision for the independent sector in the 21st century… It is no longer tenable in 2008 to retain 20th century apartheid thinking.” (Anthony Seldon (2008), “Enough of this Educational Apartheid”.)

The Irrelevant Past argument begs the question: if the proposal would change things around from how they were in the past, it is self-evidently a good thing.

Here is the scientist-philosopher Mary Warnock being sympathetic with the unfortunates who are so stuck in the past that they are opposed to genetically-modified crops:

“[For] many confused and vaguely frightened people, the new biotechnology seems to have opened up possibilities of changing the genes of plants and animals in a way which nature, or God as the Creator, never intended. … [And now] the argument has moved on [to] the myth of an unnatural creature being formed in the laboratory whose growth and behaviour could not be controlled. It was upon such fears that Mary Shelley played, as long ago as 1818, in her story of Frankenstein.”

Oh dear. Perhaps we should learn from the future?

See also: Feedback, Systems Thinking

Transformation, The Great. The Great Transformation has already happened. It was the revolution in politics, economics and society that came with the market economy, and which hit its stride in Britain in the late eighteenth century. Most of human history had been bred, fed and watered by another sort of economy, but the market has replaced, as far as possible, the social capital of reciprocal obligation, loyalties, authority structures, culture and traditions with exchange, price and the impersonal principles of economics.

Unfortunately, the critics of economics have had a tendency to discuss the whole structure as a tissue of misconceptions. It is a critique that fails. The strength of economics is its considerable, if far from complete, understanding of the flows and comparative advantages that underlie trade, jobs, capital and incomes, and the logic of optimising behaviour, all backed by glittering accomplishment in mathematics. That makes it a powerful analytical instrument, so that just a few misconceptions – such as a failure to understand the informal economy or resource depletion – can have leverage: like a baby monkey at the controls of a Ferrari, they can turn it into an instrument with extraordinarily destructive potential. If it were a tissue of errors, it would not be dangerous: it is its 90 percent brilliance which makes it so.

Economics has therefore been seductive. The market economy is effective for sustaining social order: the distribution of goods, services and other assets is facilitated by buying and selling, supporting a network of exchange to which everyone has access. It provides suppliers with the incentive to know their markets and respond to them; it uses ‘pull’ rather than top-down regulation, and it learns from experience, so it is effective and efficient. It supports a more egalitarian society than any other large-scale state has been capable of and it saves a great deal of trouble: it has appealed to minds glad of a cognitive technology which enabled them to make decisions according to mathematical models, and with little fear of contradiction.

“Douce commerce”, sweet commerce, wrote Jacques Savary, an early management consultant, in a textbook for businessmen (1685), “makes for all the gentleness of life.” The authorities themselves agreed: commerce is the most “innocent and legitimate way of acquiring wealth”, observed an edict of the French government in 1669; it is “the fertile source which brings abundance to the state and spreads it among its subjects”.

Indeed, the government’s main task in a mature market economy is to keep it free of obstacles that might stop it growing – like a bemused farmer would treat the enchanted goose: keep the foxes out so that it can go on magically laying its golden eggs.

Its achievements and answers sound authoritative and final, but what is truly most significant about them is how naïve they are – if the flow of income fails, the powerfully-bonding combination of money and self-interest will no longer be available on its present all-embracing scale, and perhaps not at all. And it must inevitably fail, as the market’s taut competitiveness demands ever-increasing productivity and thus relies on the impossibility of perpetual growth.

In the meantime, the reduction of a society and culture to dependence on mathematical abstraction has infantilised a grown-up civilisation and is well on the way to destroying it. Civilisations self-destruct anyway, but it is reasonable to ask whether they have done so before with such enthusiasm, in obedience to such an acutely absurd superstition, while claiming with such insistence that they were beyond being seduced by the irrational promises of religion. Every civilisation has had its irrational but reassuring myth. Previous civilisations have used their culture to sing about it and tell stories about it. Ours has used its mathematics to prove it.

Yet, when this relatively short-lived market-society is gone, we will miss its essential simplicity, its price mechanism, its self-stabilising properties, its impersonal exchange, the comforts it delivers to many, and the freedoms it underwrites. Its failure will be destructive.

And the end is in sight; during the early decades of the century, the market will lose its magic. It is the aim of Lean Logic to suggest some principles for the design of a replacement.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2016 | Building Alternatives, Repression at Home, Toxification

Originally published in the September/October 2012 issue of Orion. Now republished for the first time online.

In an era of government-sanctioned polluters, communities must defend themselves

Several years ago I spoke at a benefit for an organization working to prevent a toxic waste site from being built in their community. Yet another toxic waste site, the organizers clarified, since there already was one. It should surprise no one that their community was primarily poor, primarily people of color, and that the toxic waste was being brought in so that distant corporations could reap bigger profits.

The organization had been fighting the dump for years, on every level, from filing lawsuits to holding protests to physically blockading the dump site. Several people at the benefit commented on the bizarre role that the police played in all of this. Many of the cops lived in the community and were themselves opposed to the toxic dump. But when they put on their uniforms and headed off to work, their jobs included arresting their neighbors who were trying to protect the neighborhoods where their own children lived and played.

We’ve all heard of dues-paying union cops busting the heads of strikers because their capitalist bosses tell them to. And of cops arresting protesters trying to prevent the cops’ own water supplies from being toxified (while of course not arresting the capitalists who are toxifying the water supplies). And I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s had fantasies that at the next economic summit or World Bank meeting, members of the police will experience an epiphany of conscience and realize they share class interests not with those they’re protecting but rather with those at whom they’re pointing their guns. And in this fantasy the police then turn as one to join the protesters and face their real enemy.

At the benefit we shared all sorts of fantasies like these, and we all laughed at how unrealistic they were. There have been instances in which the police have worked with the people to stop government or corporate atrocities, but they’re too rare.

And then we shared some other fantasies, which all consisted in one way or another of police choosing to enforce laws that are already on the books, laws that protect our communities. Laws like the Clean Air Act, or the Clean Water Act, or for that matter laws against rape. We fantasized about what it might be like to have police enforce carcinogen-free zones, or dam-free zones, or WalMart-free zones, or rape-free zones.

And then again we laughed, since we knew that these fantasies, too, were unrealistic. It’s not the job of the police to protect you from living in a toxified landscape, even if that landscape is being toxified illegally.

In fact — and this may or may not be surprising to you — the police are under no legal obligation to protect you at all. This fact has been upheld in courts again and again. In one case, two women in Washington DC were upstairs in their townhouse when they heard their roommate being assaulted downstairs. Several times they phoned 911 and each time were told police were on their way. A half hour later their roommate stopped screaming, and, assuming the police had arrived, they went downstairs. But the police hadn’t arrived, and so for the next fourteen hours all three women were repeatedly beaten and raped. The women sued the District of Columbia and the police for failing to protect them, but the district’s highest court ruled against them, saying that it is “a fundamental principle of American law that a government and its agents are under no general duty to provide public services, such as police protection, to any individual citizen.”

So there you have it. Time and again, many similar cases have yielded the same case law, at local, state, and federal levels. But a lot of rape victims already know this; only 6 percent of rapists spend even one night in jail. And the people in that community who were having a toxic waste dump crammed down their throats with the professional support of the police also know this. As do the human and nonhuman people of the Gulf of Mexico, who are still being killed or injured by the Deepwater catastrophe — and who will experience far more of the same, since the U.S. government is supporting more deepwater drilling. As one technical advisor to the oil and gas industry put it, “We are seeing deep-water drilling coming back with a vengeance in the Gulf.”

So here’s the question: if the police are not legally obligated to protect us and our communities — or if the police are failing to do so, or if it is not even their job to do so — then if we and our communities are to be protected, who, precisely is going to do it? To whom does that responsibility fall? I think we all know the answer to that one.

A lot of people seem to love to talk about the virtues of self- and community-reliance, but where are they when we need to defend our communities?

Fortunately there are many examples of communities rising up to defend themselves from wrongdoing from which we can and should learn. Pre-Revolutionary — or you could say revolutionary yet pre-1776 — American patriots, sick and tired of rule by a distant elite (sound familiar?), increasingly refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Crown Courts and other institutions, and put in place their own systems of justice. The same has been true for the Irish in their struggle for independence. The same was true of the Spanish anarchists: part of their project included pushing fascists out of their communities and another part consisted of putting in place their own neighborhood systems of justice and community protection.

I think often of something a former head of “security” for South Africa under apartheid said: that what they’d been most afraid of from the revolutionary group the African National Congress had never been the ANC’s sabotage or even their violence, but rather that the ANC might be able to convince the mass of South Africans to not believe in law and order as such, which in this case meant the law and order imposed by the apartheid regime, which in this case meant the legitimacy of the exploitative apartheid government, which in this case meant that their greatest fear was that the ANC would convince the majority of people to withdraw their consent to be governed by an elite that does not have their best interests at heart.

In our case, we don’t need an ANC to convince us of the illegitimacy of many of the actions of those in power. Those in power are doing a great job of convincing us by their own actions. If the Gulf catastrophe (and the continuation of deepwater drilling) doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If fracking and the poisoning of our groundwater doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the governmental response to global warming — ranging from vindictiveness against climate scientists to denial to measures that at very best are completely incommensurate with the threat — doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the total toxification of the environment, with its inevitable health consequences for both humans and nonhumans, doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. I routinely ask the people at my talks whether they have had someone they love die of cancer, and at least 75 percent almost always say yes.

And when I ask people at my talks if they believe that state and federal governments take better care of corporations or of human beings, no one — and I mean no one — ever says human beings. Reframing the question to consider whether governments take better care of corporations or the planet — our only home — yields the same result.

If police are the servants of governments, and if governments protect corporations better than they do human beings (and far better than they do the planet), then clearly it falls to us to protect our communities and the landbases on which we in our communities personally and collectively depend. What would it look like if we created our own community groups and systems of justice to stop the murder of our landbases and the total toxification of our environment? It would look a little bit like precisely the sort of revolution we need if we are to survive. It would look like our only hope.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 30, 2015 | Building Alternatives, Indigenous Autonomy

By Intercontinental Cry

RE-LEARNING THE LAND is the story of a Blackfoot community in southern Alberta, Canada, and how they have re-taken control of their education system within Red Crow Community College. The film traces the decolonization of their learning and the development of an innovative program, Kainai Studies, within Red Crow College, the same site as a former Residential School. The Kainai Studies program is reclaiming and teaching to a new generation the Blackfoot knowledge system that sustained their community on their land for thousands of years.

The film raises a host of important questions related to the purpose of education and what it takes to create a deep ecological consciousness and connection with our local environment. By witnessing how students and faculty within Red Crow College are re-building relationships with the land around them, we see a greater sense of purpose, confidence and identity from amongst those participating and learning within the Kainai Studies program.

RE-LEARNING THE LAND explores how education can be used both to wipe out particular ways of knowing and lead to suffering, as in the case of residential schools, or else to promote healing and a transformation of individual and community through a reconnection to history and place. Based on a very different cosmology, set of values and ways of teaching, RE-LEARNING THE LAND is a subtle exploration of how an indigenous way of learning can create transformational relationships with the land, its beings, the community and one’s own self.

RE-LEARNING THE LAND

- Produced by: Enlivened Learning

- Directed, filmed and edited by: Udi Mandel, Kelly Teamey

- Additional Footage by: Narcisse Blood, Ryan Heavy Head

- Artwork by: Ali Hodgson, Manuela Pereira

- Official Website: films.enlivenedlearning.com

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Jun 22, 2015 | Building Alternatives, Gender, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the second part here.

Time is Short: You mentioned some problems of radical groups—lack of respect for women and lack of a strategy. Could you expand on that?

Michael Carter: Sure. To begin with, I think both of those issues arise from a lifetime of privilege in the dominant culture. Men in particular seem prone to nihilism; I certainly was. Since we were taught—however unwittingly—that men are entitled to more of everything than women, our tendency is to bring this to all our endeavors.

I will give some credit to the movie “Night Moves” for illustrating that. The men cajole the woman into taking outlandish risks and they get off on the destruction, and that’s all they really do. When an innocent bystander is killed by their action, the woman has an emotional breakdown. She’s angry with the men because they told her no one would get hurt, and she breaches security by talking to other people about it. Their cell unravels and they don’t even explore their next options together. Instead of providing or even offering support, one of the men stalks and ultimately kills the woman to protect himself from getting caught, then vanishes back into mainstream consumer culture. So he’s not only a murderer but ultimately a cowardly hypocrite, as well.

Honestly, it appears to be more of an anti-underground propaganda piece than anything. Or maybe it’s just a vapid film, but it does have one somewhat valid point—that we white Americans, particularly men, are an overprivileged self-centered lot who won’t hesitate to hurt anyone who threatens us.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

That’s a fictional example, but any female activist can tell you the same thing. And of course misogyny isn’t limited to underground or militant groups; I saw all sorts of male self-indulgence and superiority in aboveground circles, moderate and radical both. It took hindsight for me to recognize it, even in myself. That’s a central problem of radical environmentalism, one reason why it’s been so ineffective. Why should any woman invest her time and energy in an immature movement that holds her in such low regard? I’ve heard this complaint about Occupy groups, anarchists, aboveground direct action groups, you name it.

Groups can overcome that by putting women in positions of leadership and creating secure, uncompromised spaces for them to do their work. I like to reflect on the multi-cultural resistance to the Burmese military dictatorship, which is also a good example of a combined above- and underground effort, of militant and non-violent tactics. The indigenous people of Burma traditionally held women in positions of respect within their cultures, so they had an advantage in building that into their resistance movements, but there’s no reason we couldn’t imitate that anywhere. Moreover, if there are going to be sustainable and just cultures in the future, women are going to be playing critical roles in forming and running them, so men should be doing everything possible to advocate for their absolute human rights.

As for strategy, it’s a waste of risk-taking for someone to cut down billboards or burn the paint off bulldozers. It’s important not to equate willingness with strategy, or radicalism and militancy with intelligence. For example, I just noticed an oil exploration subcontractor has opened an office in my town. Bad news, right? I had a fleeting wish to smash their windows, maybe burn the place down. That’ll teach ‘em, they’ll take us seriously then. But it wouldn’t do anything, only net the company an insurance settlement they’d rebuild with and reinforce the image of militant activists as mindless, dangerous thugs.

If I were underground, I’d at least take the time to choose a much more costly and hard-to-replace target. I’d do everything I could to coordinate an attack that would make it harder for the company to recover and continue doing business. And I’d only do these things after I had a better understanding of the industry and its overall effects, and a wider-focused examination of how that industry falls into the mechanism of civilization itself.

By widening the scope further, you see that ending oil and gas development might better be approached from an aboveground stance—by community rights initiatives, for example, that have outlawed fracking from New York to Texas to California. That seems to stand a much better chance of being effective, and can be part of a still wider strategy to end fossil fuel extraction altogether, which would also require militant tactics. You have to make room for everything, any tactic that has a chance of working, and begin your evaluation there.

To use the Oak Flat copper mine example, now the mine is that much closer to happening, and the people working against it have to reappraise what they have available. That particular issue involves indigenous sacred sites, so how might that be respectfully addressed, and employed in fighting the mine aboveground? Might there be enough people to stop it with civil disobedience? Is there any legal recourse? If there isn’t, how might an underground cell appraise it? Are there any transportation bottlenecks to target, any uniquely expensive equipment? How does timing fit in? How about market conditions—hit them when copper prices are down, maybe? Target the parent company or its other subsidiaries? What are the company’s financial resources?

An underground needs a strategy for long-term success and a decision-making mechanism that evaluates other actions. Then they can make more tightly focused decisions about tactics, abilities, resources, timing, and coordinated effort. The French Resistance to the Nazis couldn’t invade Berlin, but they sure could dynamite train tracks. You wouldn’t want to sabotage the first bulldozer you came across in the woods; you’d want to know who it belonged to, if it mattered, and that you weren’t going to get caught. Maybe it belongs to a habitat restoration group, who can say? It doesn’t do any good to put a small logging contractor out of business, and it doesn’t hurt a big corporation to destroy machinery that is inexpensive, so those questions need to be answered beforehand. I think successful underground strikes must be mostly about planning; they should never, never be about impulse.

TS: There are a lot of folks out there who support the use of underground action and sabotage in defense of Earth, but for any number of reasons—family commitments, physical limitations, and so on—can’t undertake that kind of action themselves. What do you think they can do to support those willing and able to engage in militant action?

MC: Aboveground people need to advocate underground action, so those who are able to be underground have some sort of political platform. Not to promote the IRA or its tactics (like bombing nightclubs), but its political wing of Sinn Fein is a good example. I’ve heard a lot of objections to the idea of advocating but not participating in underground actions, that there’s some kind of “do as I say, not as I do” hypocrisy in it, but that reflects a misunderstanding of resistance movements, or the requirements of militancy in general. Any on-the-ground combatant needs backup; it’s just the way it is. And remember that being aboveground doesn’t guarantee you any safety. In fact, if the movement becomes effective, it’s the aboveground people most vulnerable to harm, because they’re going to be well known. In that sense, it’s safer to be underground. Think of the all the outspoken people branded as intellectuals and rounded up by the Nazis.

The next most important support is financial and material, so they can have some security if they’re arrested. When environmentalists were fighting logging in Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island in the 1990s, Paul Watson (of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society) offered to pay the legal defense of anyone caught tree spiking. Legal defense funds and on-call pro-bono lawyers come immediately to mind, but I’m sure that could be expanded upon. Knowing that someone is going to help if something horrible happens, combatants can take more initiative, can be more able to engineer effective actions.

We hope there won’t be any prisoners, but if there are, they must be supported too. They can’t just be forgotten after a month. As I mentioned before, even getting letters in jail is a huge morale booster. If prisoners have families, it’s going to make a big difference for them to know that their loved ones aren’t alone and that they will have some sort of aboveground material support. This is part of what we mean when we talk about a culture of resistance.

TS: You’ve participated in a wide range of actions, spanning the spectrum from traditional legal appeals to sabotage. With this unique perspective, what do you see as being the most promising strategy for the environmental movement?

MC: We need more of everything, more of whatever we can assemble. There’s no denying that a lot of perfectly legal mainstream tactics can work well. We can’t litigate our way to sustainability any more than we can sabotage our way to sustainability; but for the people who are able to sue the enemy, that’s what they should be doing. Those who don’t have access to the courts (which is most everyone) need to find other roles. An effective movement will be a well-organized movement, willing to confront power, knowing that everything is at stake.

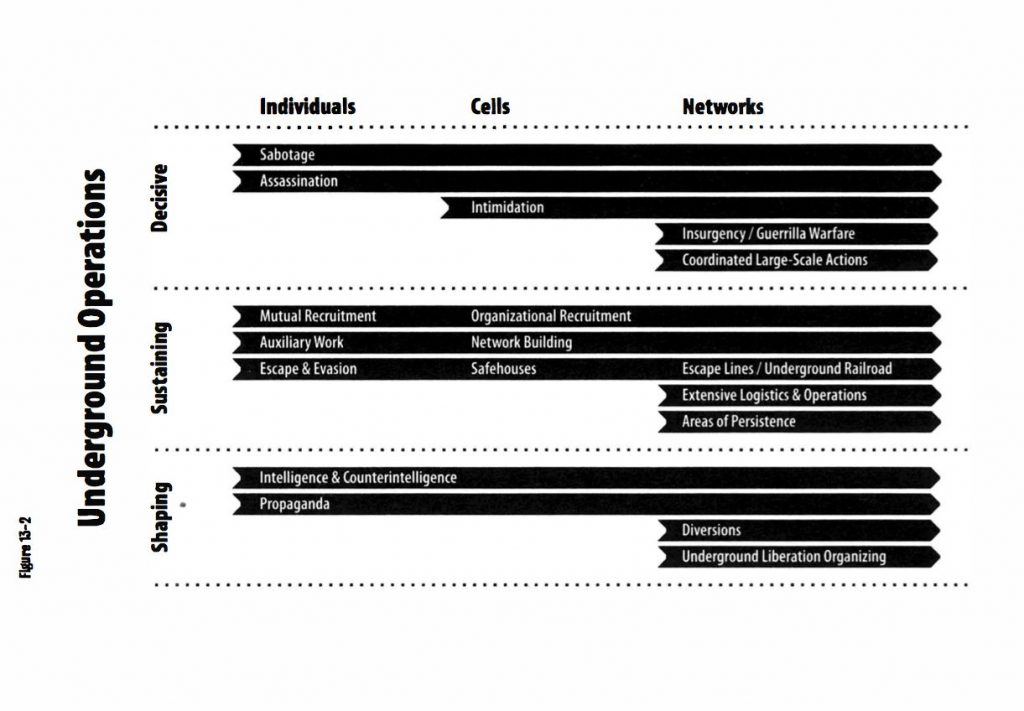

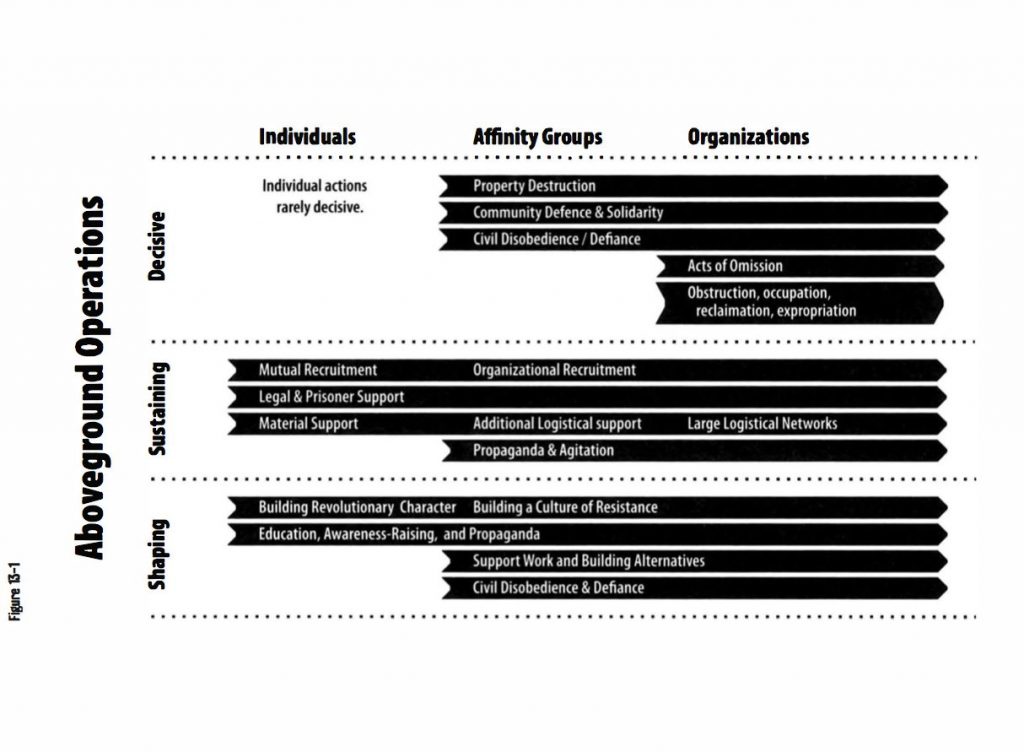

Decisive Ecological Warfare is the only global strategy that I know of. It lays out clear goals and ways of arranging above- and underground groups based on historical examples of effective movements. If would-be activists are feeling unsure, this might be a way for them to get started, but I’m sure other plans can emerge with time and experience. DEW is just a starting point.

Remember the hardest times are in the beginning, when you’re making inevitable mistakes and going through abrupt learning curves. When I first joined Deep Green Resistance, I was very uneasy about it because I still felt burned out from the ‘90s struggles. What I’ve discovered is that real strength and endurance is founded in humility and respect. I’ve learned a lot from others in the group, some of whom are half my age and younger, and that’s a humbling experience. I never really understood what a struggle it is for women, either, in radical movements or the culture at large; my time in DGR has brought that into focus.

Look at the trans controversy; here are males asking to subordinate women’s experiences and safe spaces so they can feel comfortable. It’s hard for civilized men to imagine relationships that aren’t based on the dominant-submissive model of civilization, and I think that’s what the issue is really about—not phobia, not exclusionary politics, but rather role-playing that’s all about identity. Male strength traditionally comes from arrogance and false pride, which naturally leads to insecurity, fear, and a need to constantly assert an upper hand, a need to be right. A much more secure stance is to recognize the power of the earth, and allow ourselves to serve that power, not to pretend to understand or control it.

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

MC: Three things: first, the planet wants to live. It wants biological diversity, abundance, and above all topsoil, and that’s what will provide any basis for life in the future. I think humans want to live, too; and more than just live, but be satisfied in living well. Civilization offers only a sorry substitute for living well to only a small minority.

The second is that activists now have a distinct advantage in that it’s easier to get information anonymously. The more that can be safely done with computers, including attacking computer systems, the better—but even if it’s just finding out whose machinery is where, how industrial systems are built and laid out, that’s much easier to come by. On the other hand the enemy has a similar advantage in surveillance and investigation, so security is more crucial than ever.

The third is that the easily accessible resources that empires need to function are all but gone. There will never be another age of cheap oil, iron ore mountains, abundant forest, and continents of topsoil. Once the infrastructure of civilized humanity collapses or is intentionally broken, it can’t really be rebuilt. Then humans will need to learn how to live in much smaller-scale cultures based on what the land can support and how justly they treat one another. That will be no utopia, of course, but it’s still humanity’s best option. The fight we’re now engaged in is over what living material will be available for those new, localized cultures—and more importantly, the larger nonhuman biological communities—to sustain themselves. What polar bears, salmon, and migratory birds need, we will also need. Our futures are forever linked.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Apr 25, 2015 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the third part here.

Time is Short: Your actions weren’t linked to other issues or framed in a greater perspective. How important do you think having well-framed analysis is in regards to sabotage and other such actions?

Michael Carter: It is the most important thing. Issue framing is one of the ways that dissent gets defeated, as with abortion rights, where the issue is framed as murder versus convenience. Hunger is framed as a technical difficulty—how to get food to poor people—not as an inevitable consequence of agriculture and capitalism. Media consumers want tight little packages like that.

In the early ‘90s, wilderness and biodiversity preservation were framed as aesthetic issues, or as user-group and special interests conflict; between fishermen and loggers, say, or backpackers and ORVers. That’s how policy decisions and compromises were justified, especially legislatively. My biggest aboveground campaign of that time was against a Montana wilderness bill, because of the “release language” that allowed industrial development of roadless federal lands. Yet most of the public debate revolved around an oversimplified comparison of protected versus non-protected acreage numbers. It appeared reasonable—moderate—because the issue was trivialized from the start.

That sort of situation persists to this day, where compromises between industry, government, and corporate environmentalists are based on political framing rather than biological or physical reality—an area that industry or motorized recreationists would agree to protect might have no capacity for sustaining a threatened species, however reasonable the acreage numbers might look. Activists feel obliged to argue in a human-centered context—that the natural world is our possession, whether for amusement or industry—which is a weak psychological and political position to be in, especially for underground fighters.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

When I was one of them, I never felt I had a clear stance to work from. Was I risking a decade in prison for a backpacking trail? No. Well then what was I risking it for? I chose not to think that deeply, just to rampage onward. That was my next worst mistake after bad security. Without clear intentions and a solid understanding of the situation, actions can become uncoordinated, and potentially meaningless. No conscientious aboveground movement will support them. You can get entangled in your own uncertainty.

If I were now considering underground action—and of course I’m not, you must choose to be aboveground or underground and stick with it, another mistake I made—I would view it as part of a struggle against a larger power structure, against civilization as a whole. It’s important to understand that this is not the same thing as humanity.

TS: You called civilization a plan based on agriculture. Could you expand on that?

MC: Nothing else that the dominant culture does, industrial forestry and fishing, generating electricity, extracting fossil fuels, is as destructive as agriculture. None of it’s possible without agriculture. There’s some forty years of topsoil left, and agriculture is burning through it as if it will last forever, and it can’t. Topsoil is the sand in civilization’s hourglass, the same as fossil fuels and mineral ores; there is only so much of it. When it comes to physical limits, civilization has no rationality, or even a sense of its own ultimate self-interest; only a hidden-in-plain-sight secret that it’s going to consume everything. In a finite world it can never function for long, and all it’s doing now is grinding through the last frontiers. If civilization is still continuing twenty years from now, it won’t matter how many wilderness areas are designated; civilization is going to consume those wilderness areas.

TS: How is that analysis helpful? If civilization can never be sustained, doesn’t that remove any hope of success?

MC: If we’re serious about protecting life and promoting justice, we have to acknowledge that civilized humanity will never voluntarily take the steps needed for a sustainable way of life, because its history is entirely about war and occupation. That’s what civilization does: wage war and occupy land. It appears as though this is progress, that it’s humanity itself, but it’s not. Civilization will always make power and dominance its priority, and will never allow its priority to be challenged.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

For example, production of food could be fairly easily converted from annual grains to perennial grasses, producing milk, eggs, and meat. Polyface Farms in Virginia has demonstrated how eminently possible this is; on a large scale that would do enormous good, sequestering carbon and lowering diabetes, obesity, and pesticide and fertilizer use. But grass can’t be turned into a commodity; it can’t be stored and traded, so it can never serve capitalism’s needs. So that debate will never come up on CNN, because it falls so far outside the issue framing. Hardly anyone is discussing what’s really wrong, only which capitalist or nation state will get to the last remaining resources first and how technology might cope with the resulting crises.

Another example is the proposed copper mine at Oak Flat, near Superior, Arizona. The Eisenhower administration made the land off-limits to mining in 1955, and in December 2014 the US Senate reversed that with a rider to a defense authorization bill, and Obama signed it. Arizona Senator John McCain said, “To maintain the strength of the most technologically-advanced military in the world, America’s armed forces need stable supplies of copper for their equipment, ammunition, and electronics.” See how he justifies mining copper with military need? He’s closed the discussion with an unassailable warrant, since no one in power—and hardly anyone in the public at large—is going to question the military’s needs.

TS: Are you saying there’s no chance of voluntary reform?

MC: I’m saying that it’s going to be a fight. Significant social change is usually involuntary, contrary to popular notions about “being the change you want to see in the world” and “majority rules.” Most southern whites didn’t want the US Civil Rights Movement to exist, much less succeed. In the United States democracy is mostly a fictional theory anyway, because a tiny financial and political elite run the show.

For example, in the somewhat progressive state of Oregon, the agriculture lobby successfully defeated a measure to label foods containing genetically modified organisms. A majority of voters agreed they shouldn’t know what’s in their food, their most intimate need, because those in power had enough money to convince them. There’s little hope in trying to reason with the people who run civilization, or who are otherwise trapped by it, politically or financially or however. So long as the ruling class is able to extract wealth from the land and our labor, they will. If they’ve got the machinery and fuel to run their economy, they will eventually find the political bypasses to make it happen. It will consume lives and land until there’s nothing left to consume. When the soil is gone, that’s essentially it for the human species.

Oak Flat, Arizona

What’s the point of compromising with a political system that’s patently insane? A more sensible way of approaching the planet’s predicament would be to base tactical decisions on a strategy to strip power from those who are destroying the planet. This is the root, what we have to mean when we call it a radical—root-focused—struggle.

Picture a world with no food, rising temperatures, disease epidemics, drought, war. We see it unfolding now. This is what we’re fighting against. Or rather we’re fighting for a world that can live, a world of forests and prairies and free flowing rivers that build and stabilize soil and sustain biological diversity and abundance. Our love of the world must be what guides us.

TS: You’re suggesting a struggle that completely changes how humans have arranged themselves, the end of the capitalist economy, the eventual collapse of the nation-state model of society. That sounds impossibly difficult. How might resisters approach that?

MC: We can begin by building a movement that functions as a cultural replacement for the culture we’re stuck in now. Since civilized culture isn’t going to support anyone trying to take it apart, we need other systems of material, psychological, and emotional support.

This would be particularly important for an underground movement. Ideally they would have a community that knows their secrets and works alongside them, just as militaries do. Building that network will be difficult to do in secret, because if they’re observing tight security, how do they even find others who agree with them? But because there’s little one or two people can do by themselves, they’ll have to find ways to do it. That’s a problem of logistics, however, and it’s important to separate it from personal issues.

When I was doing illegal actions, I wanted people to notice me as a hardcore environmentalist, which under the circumstances was foolish and narcissistic to the point of madness. If you have issues like that—and lots of people do, in our bizarre and hurtful culture—you need to resolve them with self-reflection and therapy, not activism. The most elegant solution would be for your secret community to support and acknowledge you, to help you find the strength and solidarity you need to do hard and necessary work, but there are substitutes available all the same.

TS: You’ve been involved with aboveground environmental work in the years since your underground actions. What have you worked on, and what are you doing now?

MC: I first got involved with forestry issues—writing timber sale appeals and that sort of thing. Later I helped write petitions to protect species under the Endangered Species Act. I burned out on that, though, and it took me a long time to get drawn back in. Aboveground people need the support of a community, too—more than ever. Derrick Jensen’s book A Language Older Than Words clarified the global situation for me, answered many questions I had about why things are so difficult right now. It taught me to be aware that as civilized culture approaches its end, people are getting ever more self-absorbed, apathetic, and cruel. Those who are still able to feel need to stand by each other as well as they can.

When Deep Green Resistance came into being, it was a perfect fit, and I’ve been focused on helping build that movement. Susan Hyatt and I are doing an essay series on the psychology of civilization, and how to cultivate the mental health needed for resistance. I’m also interested in positive underground propaganda. Having stories to support what people are doing and thinking is important. It helps cultivate the confidence and courage that activists need. That’s why governments publish propaganda in wartime; it works.

TS: So you think propaganda can be helpful?

MC: Yes, I do. The word has a negative connotation for some good reasons, but I don’t think that attempting to influence thoughts and actions with media is necessarily bad, so long as it’s honest. Nazi Germany used propaganda, but so did George Orwell and John Steinbeck. If civilization is brought down—that is, if the systems responsible for social injustice and planetary destruction are permanently disabled—it will require a sustained effort for many years by people who choose to act against most everything they’ve been taught to believe, and a willingness to risk their freedom and lives to bring it about. Entirely new resistance cultures will be needed. They will require a lot of new stories to sustain a vision of who humans really are, and what our lives are for, how they relate to other living things. So far as I know there’s little in the way of writing, movies, any sort of media that attempts to do that.

Edward Abbey wrote some fun books, and they were all we had; so we went along hoping we’d have some of that fun and that everything might come out all right in the end. We no longer have that luxury for self-indulgence. I’m not saying humor doesn’t have its place—quite the opposite—but the situation of the planet and social situation of civilization is now far more dire than it was during Abbey’s time. Effective propaganda should reflect that—it should honestly appraise the circumstances and realistically compose a response, so would-be resisters can choose what their role is going to be.

This is important for everyone, but especially important for an underground. In World War II, the Allies distributed Steinbeck’s propaganda novel The Moon is Down throughout occupied Europe. It was a short, simple book about how a small town in Norway fought against the Nazis. It was so mild in tone that Steinbeck was accused by some in the US government of sympathizing with the enemy for his realistic portrayal of German soldiers as mere people in an awful situation, and not superhuman monsters. Yet the occupying forces would shoot anyone on the spot if they caught them with a copy of the book. Compare that to Abbey’s books, and you see how far short The Monkey Wrench Gang falls of the necessary task.

TS: Can you suggest any contemporary propaganda?

Derrick Jensen’s Endgame books are the best I can think of, and the book Deep Green Resistance. There’s some negative-example propaganda worth mentioning, too. The book A Friend of the Earth, by T.C. Boyle. The movies “The East” and “Night Moves” are both about underground activists, and they’re terrible movies, at least as propaganda for effective resistance. “The East” is about a private security firm that infiltrates a cell whose only goals are theater and revenge, and “Night Moves” is even worse, about two swaggering men and one unprepared woman who blow up a hydroelectric dam.

The message is, “Don’t mess with this stuff, or you’ll end up dead.” But these films do point out some common problems of groups with an anarchistic mindset: they tend to belittle women and they operate without a coherent strategy. They’re in it for the identity, for the adrenaline, for the hook-up prospects—all terrible reasons to engage. So I suppose they’re worth a look for how not to behave. So is the documentary film “If a Tree Falls,” about the Earth Liberation Front.

Social change movements can suffer from problems of immaturity and self-infatuation just like individuals can. Radical environmentalism, like so many leftist causes, is rife with it. Most of the Earth First!ers I knew back in the ‘90s were so proud of their partying prowess, you couldn’t spend any time with them without their getting wasted and droning on about it all the next day. One of the reasons I drifted away from that movement was it was so full of arrogant and judgmental people, who seemed to spend most of their time criticizing their colleagues for impure living because they use paper towels or drive an old pickup instead of a bicycle.

This can lead to ridiculous guilt-tripping pissing matches. It’s no wonder environmentalists have such a bad reputation among the working class, when they’re indulging in self-righteous nitpicking that’s really just a reflection of their own circumstantial advantages and lack of focus on effectively defending the land. Tell a working mother to mothball her dishwasher because you heard it’s inefficient, see how far you get. It’s one of the worst things you can say to anyone, especially because it reinforces the collective-burden notion of responsibility for environmental destruction. This is what those in power want us to think. Developers build new golf courses in the desert, and we pretend we’re making a difference by dry-brushing our teeth. Who cares who’s greener than thou? The world is being gutted in front of our eyes.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 6, 2014 | Building Alternatives, Colonialism & Conquest, Defensive Violence, Indigenous Autonomy

By Frank Coughlin / Deep Green Resistance New York

Humility. An important word you rarely hear in our culture anymore. Our culture seems to be going in the opposite direction, everything with a superlative. Everything bigger, faster, better, stronger. Everything new, shiny, pretty, expensive. But never humble. “Dude, love that car. It’s so humble.” Yeah, you never hear that.

Politically on the left, in the “fight” as we call it, we’re just as guilty. We have a tendency towards ego, self-righteousness, hyper-individualism. We want our movements to be better, stronger, bigger. We want the big social “pop-off”, the “sexy” revolution, perhaps our face on the next generation’s t-shirts. But we never ask for humility. As we near what most scientists predict to be “climate catastrophe”, I’ve been thinking a lot about humility. I recently was able to travel to Chiapas, Mexico to learn about the Zapatista movement. I was there for a month, working with various groups in a human rights capacity. While I was there to provide some type of service, I left with a profound respect for a true revolutionary humility. This essay is not designed to be a complete history of the Zapatista movement, but perhaps it can provide some context.

The Zapatistas are an indigenous movement based in the southern state of Chiapas, Mexico. The name is derived from Emiliano Zapata, who led the Liberation Army of the South during the Mexican Revolution, which lasted approximately from 1910-1920. Zapata’s main rallying cry was “land and liberty”, exemplifying the sentiments of the many indigenous populations who supported and formed his army. The modern-day Zapatistas declare themselves the ideological heirs to these struggles, again representing many indigenous struggles in southern Mexico. While the Zapatistas became public in 1994, as their name implies, their struggle is the culmination of decades of struggle. Many of the mestizos (non-indigenous) organizers came from the revolutionary student struggles of the 60s and 70s in Mexico’s larger cities. In 1983, many of these organizers, along with their indigenous counterparts, who represented decades of indigenous organizing in the jungles of Mexico, formed the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN).

From 1983 to their dramatic declaration of war against the Mexican government in 1994, the EZLN formed and trained a secret army under the cover of the Lacandon Jungle. After a decade of organizing and training in the context of extreme poverty, an army of indigenous peasants, led by a mix of mestizos and indigenous leaders, surprised the world by storming five major towns in Chiapas. They chose the early morning hours of January 1st, 1994, the day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect. The connection with NAFTA was intentional because the destructive neoliberal policies inherent in the agreement were viewed as a death sentence to indigenous livelihoods. They used old guns, machetes, and sticks to take over government buildings, release prisoners from the San Cristobal jail, and make their first announcement, The First Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle. With most wearing the now signature pasamontañas over their faces, they declared war on the Mexican government, saying:

We are a product of 500 years of struggle: first against slavery, then during the War of Independence against Spain led by insurgents, then to avoid being absorbed by North American imperialism, then to promulgate our constitution and expel the French empire from our soil, and later the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz denied us the just application of the Reform laws and the people rebelled and leaders like Villa and Zapata emerged, poor men just like us. We have been denied the most elemental preparation so they can use us as cannon fodder and pillage the wealth of our country. They don’t care that we have nothing, absolutely nothing, not even a roof over our heads, no land, no work, no health care, no food nor education. Nor are we able to freely and democratically elect our political representatives, nor is there independence from foreigners, nor is there peace nor justice for ourselves and our children.

But today, we say ENOUGH IS ENOUGH…

We, the men and women, full and free, are conscious that the war that we have declared is our last resort, but also a just one. The dictators are applying an undeclared genocidal war against our people for many years. Therefore we ask for your participation, your decision to support this plan that struggles for work, land, housing, food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace. We declare that we will not stop fighting until the basic demands of our people have been met by forming a government of our country that is free and democratic.

Very true to the words of Zapata, that it is “better to die on your feet than live on your knees”, the EZLN fighters engaged in a self-described suicide against the Mexican government. As Subcommandante Marcos, now known as Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, the public face of the EZLN, stated, “If I am living on borrowed time, it is because we thought that we would go to the world above on the first of January. When I arrived at the second day, and the following, it was all extra.”1

What followed was a war of government repression. The quiet mountain towns of Chiapas were flooded with advanced military equipment and troops. A twelve-day battle ensued, with rebel retreats and civilian massacres, finally ending with a cease-fire. Following this “peace agreement”, the EZLN no longer offensively attacked, but refused to lay down their arms. The government engaged in raids, attacks on civilian populations, and initiated a paramilitary war. Formal peace accords, known as the San Andres Accords, were signed between the government and the EZLN leadership in February of 1996. They addressed some of the root causes of the rebellion, such as indigenous autonomy and legal protections for indigenous rights. While signed in 1996, the agreements did not make it to the Mexican congress until 2000. There they were gutted, removing key principles as signed by the EZLN, such as the right of indigenous autonomy. Much has been written on the history of the EZLN after the failure of the peace accords, including the march to Mexico City, as well as the EZLN’s attempts at fostering a larger social movement force. The EZLN released their “Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle”, which highlights their call to the Mexican and international populations to work to ”find agreement between those of us who are simple and humble and, together, we will organize all over the country and reach agreement in our struggles, which are alone right now, separated from each other, and we will find something like a program that has what we all want, and a plan for how we are going to achieve the realization of that program…”

In 2003, the EZLN released a statement that began the process of radically restructuring the Zapatista communities with the development of autonomous municipalities, called caracoles (conch shell). The name caracole was picked because as Marcos once explained, the conch shell was used to “summon the community” as well as an “aid to hear the most distant words”. The caracoles and their respective “councils of good government” (as opposed to the “bad government” of Mexico) were designed to organize the rebel municipalities as well as to push forward the original mandate of indigenous autonomy. With the failure of the San Andres accords, the Zapatistas openly decided that they would follow the word of the accords that they had signed, regardless of the Mexican government’s policy. In line with their mandate to “lead by obeying”, the EZLN, the armed aspect of the Zapatistas, separated themselves from the work of the civil society and abdicated control of the Zapatista movement to the caracoles.

The objective was “to create — with, by, and for the communities — organizations of resistance that are at once connected, coordinated and self-governing, which enable them to improve their capacity to make a different world possible. At the same time, the project postulates that, as far as possible, the communities and the peoples should immediately put into practice the alternative life that they seek, in order to gain experience. They should not wait until they have more power to do this. “What has occurred in the past decade is that the Zapatistas have put the original demand for indigenous autonomy into practice by creating autonomous governments, health systems, economic systems, and educational systems. In doing so, they have stayed true to the ideals of “leading from below” and a rejection of the ideal to overtake state power. They have “constructed a world in which they have realized their own vision of freedom and autonomy, and continue to fight for a world in which other worlds are possible.”

Their fight is very much alive today, more than twenty years after its first public appearance. My recent visit was to the Oventik caracole, located in the Zona Alta region. Myself and three others were sent as human rights observers with El Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas (Fray Bartolome de Las Casa Human Rights Center) to the small community of Huitepec, immediately north of the mountain town of San Cristobal de Las Casas. Here the community is placed in charge of protecting the large Zapatista reserve of Huitepec from loggers, poachers, and government forces. As observers, our task was to accompany the Zapatista families on their daily walks through the 100+ acre reserve, keep track of any intrusions on the autonomous land, and document any infractions. We lived in a simple house, with a fire to cook on and wood panels for sleeping. There was no running water, minimal electricity, and no forms of electronic communication, even with the close proximity to the town of San Cristobal.

Through these eyes we learned of the daily struggle of the Zapatistas. The community consisted of eight Zapatista families. Originally fifteen families, many of them had left Zapatismo to suffer against poverty with the “bad” government. The families who stayed as Zapatistas were indigenous to the area, having struggled to protect the land long before the Zapatista’s uprising in 1994. The families lived in poverty, dividing their time between protecting the reserve, growing flowers for sale in San Cristobal, and working their rented fields two hours away. Their days started with the sunrise and often ended long after the sun had set. Their hands were strong and their walk through the mountains fast, evidence of a lifetime of hard labor. They told us of life before the uprising, coming to Zapatismo, their struggles with inner council decisions, and their hopes for the future.

We bombarded them with questions, testing the theories of the Zapatistas we had read in books and working to understand the structure of their autonomy. Most spoke Spanish fluently, but outside of our conversations, they spoke their indigenous language. Often times, long questions were answered with a pause and then a “Si!,” only to find out later that much had been lost in translation. The Zapatistas taught us to recognize medicinal plants on our walks, how to cut firewood, helped our dying cooking fires, and shared tea and sweet bread with us. For much of our time together we sat in silence, staring at the fire, each unsure of what to say to people from such different cultures. We, the foreigners, sat in silence in the reserve, lost in our thoughts, struggling to understand the lessons in front of us.

Fortunately, there was little work to be done in our role as human rights observers. As the families stated, most of the repressive tactics of the “bad” government in that area have been rare in recent years. Paramilitary and military forces still affect Zapatista communities, as evidenced by the assassination of José Luis López, known as “Galeano” to the community, a prominent teacher in the caracole of La Realidad in May of 2014. In addition, a week prior to our arrival, paramilitary forces had forcibly displaced 72 Zapatista families from the San Manuel community.

As I look back on my experience, I am forced to place it in the context of what we on the left are doing here in the US and I think back to the humility of the experience. The backdrop of the experience was always in the context of the severe poverty the community struggled against. The families cleaned their ripped clothes as best they could, walked for hours in the jungle in plastic, tired shoes, and spoke of their struggle to place food in their stomachs. They told us of the newborn who had died a few weeks prior to our arrival. They softly commented on the lack of rain in their fields, which meant that no crops had grown. When asked what they would do, they shrugged their shoulders, stared off into the horizon, and quietly said “I don’t know.”

One of the elders (names intentionally left out for security reasons) told us of what he felt for the future. He told us that little by little, more and more Zapatistas are asking the EZLN to take up arms again. He felt they were at a similar social situation as they were in 1993, prior to the uprising. And then he said something that truly humbled me. He said, “we love this land, and if we’re going to die anyway, it would be better to die fighting.” His face was filled with a distant look, touched by sadness, but also of determination. And then there was silence. No theories, no Che t-shirts, no rhyming slogans. No quotes, no chest thumping, no sectarianism. Just the honesty of someone who has nothing left to lose and everything to gain. In that moment, I was gifted the glimpse of the true humility of revolutionary thought. Here was a man who has struggled to survive his entire life. He fights in the way he knows how. He has a simple house and wears the same tucked in dirty dress shirt. He works in the fields as well as the communal government. He knows that the fight he and his community face are against massive transnational corporations who wish to extract the precious resources underneath his ancestral land. He knows that they will hire the government, paramilitary forces, and the police to intimidate and coerce him into submission, likely killing him and his family if he refuses. He lives in an area of the world that has been described as one of the most affected by climate change. And because of this climate change, a force that he did not cause, his children will not have food for the winter. He does not talk of Facebook posts, of petitioning politicians, of symbolic protests. There is no mention of hashtags, things going “viral”, “working with the police”, buying organic, fad diets, or identity politics. There are no self-congratulatory emails after symbolic protests. He doesn’t say anything about “being the change,” “finding himself,” or engaging in a never-ending debate on the use of violence versus non-violence. He simply states “we are part of this land and we will die to protect it,” and then continues walking.

I find myself thinking about that community as I re-enter the world of activism here in New York City. We are bombarded with the temptations of an insane and immoral culture of consumption. As I write this, young black men are being assassinated by police officers, inequality is at an all-time high, the newspapers are filled with “Fashion Week” events, and people are camping out in front of the Apple store for their new Iphones. On the left, communities are organizing around every type of campaign, with a growing focus on climate change. While there is some great grassroots work being done, even in the insanity of New York City, I can’t help but see the lack of humility that exists in our progressive communities. I include myself in this critique, and write as a member of the Left.

Our conversations are dominated with rhetoric and sectarianism. We talk in the language of books and posts, not in material experiences. We speak of “developing” the third world, as though our complicity in a globally destructive system of capitalism is somehow as invisible as we would like to believe. We use our politically correct language and speak of our “individual oppression”. We wait for perfection, for the “revolution”, wearing our “radical” clothes, speaking our “radical” talk in our “radical” spaces that are devoid of any connection to the material world. And at the end of the day, the destruction around us, the destruction that we are complicit in, continues. Something that has embedded itself in my thoughts this past year is exemplified by two quotes.

One is a quote by Che Guevara, in which he says, “At the risk of sounding ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love.” The second is a lyric by the group “The Last Poets”, where they proclaim, “Speak not of revolution until you are willing to eat rats to survive, come the Revolution.” Quite different ideas, and yet, as I return to the craziness of New York City, I see how similar they are. Revolution is a term often thrown about without a clear definition. Some people see revolution in the context of an armed uprising of oppressed peoples, others, like the CEOs of Chevrolet, see revolution in terms of their new car line. Others see a “revolution of ideas” transforming the world. For the Zapatistas, it is based in the “radical” idea that the poor of the world should be allowed to live, and to live in a way that fits their needs. They fight for their right to healthy food, clean water, and a life in commune with their land. It is an ideal filled with love, but a specific love of their land, of themselves, and of their larger community. They fight for their land not based in some abstract rejection of destruction of beautiful places, but from a sense of connectedness. They are part of the land they live on, and to allow its destruction is to concede their destruction. They have shown that they are willing to sacrifice, be it the little comforts of life they have, their liberty, or their life itself.

We here in the Left in the US talk about the issues of the world ad nauseum. We pontificate from afar on theories of oppression, revolutionary histories, and daily incidences of state violence. We speak of climate change as something in the future. But so often we are removed from the materiality of the oppression. Climate change is not something in the future, but rather it is something that is killing 1,000 children per day, roughly 400,000 people per year. Scientists are now saying that the species extinction rate is 1,000 times the natural background extinction rate, with some estimates at 200 species a day, because of climate change. Black men are being killed at a rate of one every 28 hours in the US. One in three women globally will be sexually assaulted in their lifetime. There are more global slaves than ever in human history, with the average cost of a slave being $90. It is estimated that there is dioxin, one of the most horrific chemicals we have created and a known carcinogen, in every mother’s breast milk. We read about “solidarity” with the oppressed and work for “justice”. We speak of “loving the land” and wanting to “protect” nature. But how can we say we “love” these people/places/things when the actions we take to protect them have been proven to be wholly ineffective and stand no chance of achieving our stated goals?

We are told to focus on small lifestyle reforms, petitioning politicians who have shown that they do not listen to us, and relying on a regulatory system that is fundamentally corrupt. We are bombarded with baseless utopian visions of a “sustainable world”, complete with solar panels, wind turbines, abundance, and peace. But these are false visions, meant to distract us. Our entire world infrastructure is based in an extractive, destructive process, without which our first world way of life is entirely impossible. Everything from the global wars, increasing poverty, the police state, and climate change are built around this foundational injustice. These injustices are inherent and are not “reformable”. If it were our child being slaughtered to mine the rare earth minerals necessary for our technology, would we perhaps have a different view of our smartphone? If our land were being irradiated by runoff from solar panel factories, would we think differently about green energy? If our brother was murdered by a police officer to protect a system of racial oppression, would we be OK with just posting articles on Facebook about police brutality? If paramilitaries were going to murder our family to gain access to timber, would we engage in discussions on the justifications for pacifism?

In the face of the horrific statistics of our dying planet, we need a radically different tactic. We need a radical humility. As an example, just to temper the slaughter of the 400,000 human beings being killed by climate change would require a 90% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. That means no more industrial food production, no more travel, no more development of green energy, no electricity, no internet, no police state, and I’m sorry to say, no fucking iPhone 6. Tell me how our movements even touch on the reality of our current situation? I think that for the majority of the Left in the “developed world”, if we truly had love as our foundation, our actions would have much more humility.

For me, this is what Che is speaking to. Those who truly want to change the world need to base their reality in a reality of love. It is love, with all its beauty and romanticism, but also with its inherent responsibility, that powers those who are willing to sacrifice. With that love comes a loss of self and the beginning of humility. Most of us here in the global north who fight for global justice must learn this humility. We, as a whole, are more privileged than any other population has ever been in human history. History has shown that we will not give up this privilege. We will not “eat rats” voluntarily, no matter how radical we may think we are. These things can only be taken from us. If we truly want a world of justice, we must understand this fact and accept the humility to forget ourselves.