by DGR News Service | Sep 28, 2021 | Education, Strategy & Analysis, Worker Exploitation

This article is from the blog buildingarevolutionarymovement.

This post will look at the long-term cycles of the geographical centre of the capitalist economy (during capitalisms existence over the last 600 years), capitalism’s economic waves and cycles and the 10-year capitalist business cycle.

There are several theories of historical cycles that relate to societies or civilisations, these are beyond the scope of this post

Understanding capitalism’s cycles and waves are important to understanding capitalism better to be able to beat it. Also, there looks to be a relationship between capitalism’s cycles and waves, and cycles of worker and social movement expansion, and also related to the gains and concessions these movements get from capitalists.

Long-term cycles of the geographic centre of the capitalist economy

This builds on the phases of capitalism described in a previous post: Mercantile Capitalism, 14th-18th centuries; Classical/Industrial Capitalism, 19th century; Keynesianism or New Deal Capitalism, 20th century; and Finance Capitalism/Neoliberalism, late 20th century.

These ideas were likely first developed by Fernand Braudel, who described the movement of centres of capitalism, initially cities then nation-states. Braudel described them starting in Venice from 1250-1510, then Antwerp from 1500-1569, Genoa from 1557-1627, Amsterdam from 1627-1733, and London/England 1733-1896.

Immanuel Wallerstein describes as part of his ‘world-system theory’ that there have been three countries that have dominated the world system: the Netherlands in the 17th century, Britain in the 19th century and the US after World War I.

Giovanni Arrighi identifies four ‘systemic cycles of accumulation’ in his book The Long Twentieth Century. He describes a ‘structuralist model’ of capitalist world-system development over the last 600 years of four ‘long centuries’, with a different economic centre. Arrighi’s systemic cycles of accumulation were centred around: the Italian city-states in the 16th century, the Netherlands in the 17th century, Britain in the 19th century and the United States after 1945. [1] It looks like the centre is moving Eastwards in the twenty-first century. [2]

George Modelski identified long cycles that connect war cycles, economic dominance, and the political aspects of world leadership, in his 1987 book Long Cycles in World Politics. He argues that war and other destabilising events are a normal part of long cycles. Modelski describes several long cycles since 1500, each lasting from 87 to 122 years: starting with Portugal in the 16th century, the Netherlands in the 17th century, Britain in the 18th and 19th century and the US since 1945.

Capitalism’s economic waves and cycles

Several waves and cycles have been identified in the capitalist economy that relate to periods of economic growth and decline.

Kondratiev waves (also known as Kondratieff waves or K-waves) are 40 to 60-year cycles of capitalism’s economic growth and decline. This is a controversial theory and most academic economists do not recognise it. But then most academic economists think that capitalism is a good idea!

Kondratiev/Kondratieff identified the first wave starting with the factory system in Britain in the 1780s, ending about 1849. The second wave starts in 1849, connected to the global development of the telegraph, steamships and railways. The second waves’ downward phase starts about 1873 and ends in the 1890s. In the 1920s, he believed a third wave was taking place, that had already reached its peak and started its downswing between 1914 and 1920. He predicted a small recovery before a depression a few years later. This was an accurate prediction. [3]

Paul Mason in Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future describes the phases of the K-waves:

“The first, up, phase typically begins with a frenetic decade of expansion, accompanied by wars and revolutions, in which new technologies that were invented in the previous downturn are suddenly standardized and rolled out. Next, a slowdown begins, caused by the reduction of capital investment, the rise of savings and the hoarding of capital by banks and industry; it is made worse by the destructive impact of wars and the growth of non-productive military expenditure.

“However, this slowdown is still part of the up phase: recessions remain short and shallow, while growth periods are frequent and strong.

Finally, a down phase starts, in which commodity prices and interest rates on capital both fall. There is more capital accumulated than can be invested in productive industries, so it tends to get stored inside the finance sector, depressing interest rates because the ample supply of credit depresses the price of borrowing. Recessions get worse and become more frequent. Wages and prices collapse, and finally a depression sets in.

In all this, there is no claim as to the exact timing of events, and no claim that the waves are regular.” [4]

Mason describes his theory of a fourth wave starting in 1945 and peaking in 1973 when oil-exporting Arab countries introduced an oil embargo on the USA and reduced oil output. The global oil price quadrupled, resulting in several nations going into recession. Mason argues that the fourth wave did not end but was extended and is still ongoing. The downswing of the previous three cycles ended by capitalists innovating their way out of the crisis using technology. This was not the case in the current fourth cycle because the defeat of organised labour (trade unions) by neoliberal governments in the 1980s, has resulted in little or no wage growth and atomization of the working class. [5]

In On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War Kim Moody used data from three sources (Mandel, Kelly, Shaikh) to identify his theory of a third (1893-1945), fourth (1945-1982) and fifth (1982-present) long waves. The third upswing from 1893-1914, then downswings from 1914-1940. The fourth upswing from 1945-1975, downswings from 1975-1982. The fifth upswing from 1982-2007, downswings from 2007-?. [6]

Joseph Schumpeter identified several smaller cycles have been combined to form a ‘composite waveform’ that sit under the K-waves.

The Kuznets swing is a 15-25 year cycle related to infrastructure investment, construction, land and property values.

The Juglar cycle is a 7-11 year cycle related to the fluctuations in the investment in fixed capital. Fixed capital are real, physical things used in the production of goods, such as buildings or machinery.

The Kitchin cycle is a 3-5 year cycle caused by the delay it takes the management of businesses to decide to increase or decrease the production of goods based on information from the marketplaces where they sell their goods.

Business cycle

This is the roughly 10-year boom and slump cycle of the global capitalist economy. It is also known as the (economic cycle, boom-slump cycle, industrial cycle). Mainstream economics view shocks to the economy as random and therefore not cycles. There are several theories of what causes business cycles and economic crises that I will look at in a future post. Theories about the business cycle have been developed by Karl Marx, Clément Juglar, Knut Wicksell, Joseph Schumpeter, Michał Kalecki, John Maynard Keynes. Schumpeter identified four stages of the business cycle: expansion crisis, recession, recovery.

So what are the dates of the business cycle? I’ll go through the information on business cycles in the US and UK since 1945 and there is no clear agreement on the number. Something to come back to.

Howard J. Sherman in The Business Cycle Growth and Crisis under Capitalism argues that the best dates are those provided by the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). He explains that they’re not ideal but the best available and they go back a long way. Since 1945, the US has had recession in the years 1949, 1954, 1958, 1961, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1982, 1991, 2001, 2009. That is ten business cycles, eleven if you include the one that started in the last ten years. The Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI) uses these dates as well.

Sam Williams at the blog Critique of Crisis Theory is critical of the NBER dates and argues that there have only been five business cycles since 1945. He measures them based on the point they peaked rather than a recession: 1948-1957, 1957-1968, 1982-1990, 1990-2000, 2000-2007. He describes the period from 1968-1982 as one long crisis. A sixth business cycle could be added from 2007-2020.

D fisher identified 9 cycles from 1945-1991.

For the UK, I found three different sets of information of when the business cycles have been. Each indicates a different number of business cycles since 1945.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research list UK business cycles since 1945 as peak 1951, trough 1952; peak 1955, trough 1958; peak 1961, trough 1963; peak 1964, trough 1967; peak 1968, trough 1971, peak 1973, trough 1975; peak 1979, trough 1982; peak 1984, trough 1984; peak 1988, trough 1992. So that’s nine business cycles from 1945-1992.

The Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI) identifies UK business cycles since 1945 to be: trough 1952; peak 1974, trough 1975; peak 1979, trough 1981; peak 1990, trough 1992; peak 2008, trough 2010. The ECRI chart does not list anything for the current crisis but I think it it’s safe to assume that 2020 was the peak. That is five business cycles from 1945-2020.

Wikipedia lists recession in the UK since 1945 taking place in: 1956, 1961, 1973, 1975, 1980-1, 1990-1, 2008-9 and 2020-? That is seven business cycles from 1945-2020.

Endnotes

- Giovanni Arrighi: Systemic Cycles of Accumulation, Hegemonic Transitions, and the Rise of China, William I. Robinson, 2011, page 6/7, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254325075_Giovanni_Arrighi_Systemic_Cycles_of_Accumulation_Hegemonic_Transitions_and_the_Rise_of_China/link/54f4dbd80cf2ba6150642647/download

- Giovanni Arrighi: Systemic Cycles of Accumulation, Hegemonic Transitions, and the Rise of China, page 10

- Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, Paul Mason, 2015, page 35/6

- Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, page 36

- Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, CH4

- On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War, Kim Moody, 2018, page 72

by DGR News Service | Sep 14, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Education, Strategy & Analysis

This article is from the blog buildingarevolutionarymovement.

This post lists and challenges, debunks, pulls apart the following myths of capitalism:

- there is no alternative to capitalism

- capitalism is the only system that provides individual and economic freedom

- everything is better under capitalism

- as capitalism increases the size of the economy, everyone benefits

- free-market capitalism is the best way to run the global economy

- capitalist economic theory is the best

- capitalism maintains low taxes, which is good for workers and businesses

- capitalism promotes equality, work hard and you’ll get rich

- capitalism fits well with human nature

- capitalism and democracy work well together

- capitalism gradually balances differences across countries through free markets and free trade.

There is a liberal capitalist myth about progress. A determinist (set path forwards) view that things will continue to get better. I completely disagree with this perspective and it is clearly wrong if you look at history, esp the last 40 years. I will describe and challenge this myth in a future post.

I would like to start with a quote from 23 Things They Dont Tell You About Capitalism by Ha-Joon Chang:

“Most countries have introduced free-market policies over the last three decades – privatization of state-owned industrial and financial firms, deregulation of finance and industry, liberalization of international trade and investment, and reduction in income taxes and welfare payments. These policies, their advocates admitted, may temporarily create some problems, such as rising inequality, but ultimately they will make everyone better off by creating a more dynamic and wealthier society. The rising tide lifts all boats together, was the metaphor.

The result of these policies has been the polar opposite of what was promised. Forget for a moment the financial meltdown, which will scar the world for decades to come. Prior to that, and unbeknown to most people, free-market policies had resulted in slower growth, rising inequality and heightened instability in most countries. In many rich countries, these problems were masked by huge credit expansion; thus the fact that US wages had remained stagnant and working hours increased since the 1970s was conveniently fogged over by the heady brew of credit-fuelled consumer boom. The problems were bad enough in the rich countries, but they were even more serious for the developing world. Living standards in Sub-Saharan Africa have stagnated for the last three decades, while Latin America has seen its per capita growth rate fall by two-thirds during the period. There were some developing countries that grew fast (although with rapidly rising inequality) during this period, such as China and India, but these are precisely the countries that, while partially liberalizing, have refused to introduce full-blown free-market policies.

Thus, what we were told by the free-marketeers – or, as they are often called, neo-liberal economists – was at best only partially true and at worst plain wrong…the ‘truths’ peddled by free-market ideologues are based on lazy assumptions and blinkered visions, if not necessarily self-serving notions.”[1]

Myth – there is no alternative to capitalism

The argument goes that there is no viable alternative economic system. Centrally controlled governments have been tried and failed. Capitalism isn’t perfect but it’s all we’ve got. [2]

Simplistically this is an argument against planned economies which I will deal with in the free market capitalism section below. The main two examples of communist planned economies are the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. There are many different forms of communism and these are authoritarian examples. They only came to exist and survive in the violent 20th century because they had strong leadership and then used military force to defend themselves against capitalist nations that attempted to destroy them. There is of course more to their survival than this but that is for another post. I’m not in the slightest defending the horrific violence they directed to their citizens. Critics of these experiments do not acknowledge all the positive things that we can learn from the Soviet Union – self-management, collectivisation, new housing processes, increases in literacy. [3]

What I want to focus on here is that if capitalism is genuinely the only naturally existing economic system, then why do capitalists have to constantly crush any alternatives. Because, capitalists see these embryonic alternatives as a threat to their wealth, dominance and control. This is done either through extreme media manipulation and propaganda or with violence and killings. This post gives three examples of capitalists crushing alternatives: the Copenhagen squatting movement, New Age Travellers in the UK, and the US-backed 1973 military coup of the socialist government of Salvador Allende in Chile. Other examples are the tens of thousands killed after the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871 [4], German Revolution 1918-19, the EU drastic threats against the Syriza Greek government in 2015, and the demonisation of Jeremy Corbyn.

Myth – capitalism is the only system that provides individual and economic freedom

The moral argument for capitalism is based on individual freedom being a natural right that pre-exists society. Capitalist society is valued and justified because it benefits humans and enhances economic freedom, instead of limiting it.

This individual and economic freedom is a limited form of freedom. In the #ACFM episode – Trip 10 How It Feels to Be Free, several forms of freedom are discussed. These include comparing the liberal, conservative, radical and authoritarian traditions and their relationship to freedom [5]. They also discussed Isaiah Berlin’s Two Concepts of Liberty – positive and negative [6]. The negative concept is freedom from constraint to do what you want. This is described as the ‘Jeremy Clarkson concept of freedom’ or the ‘anti-woke concept of freedom [7] The positive idea is a freedom to do something and for many, this means that the material conditions have to be created, which resulted in the post-war welfare state. [8]

Myth – everything is better under capitalism

The arguement goes that capitalism has resulted in improved basic standards of living, reduction in poverty and increased life expectancy. There is also the argument that Western capitalist countries have the happiest populations because they can consume whatever products and services they like.

The truth behind this myth is that capitalism results in economic growth, which has come at huge costs – see the economic growth myths below. The myth is that capitalism intentionally results in better living standards for workers and the general population. This relates to the liberal myth about liberal progress (see a future post on this). Any reform or improvement in the living standards of workers and the general population has to be fought for by people and groups (trade unions, social movements or in parliament) who want these improvements. Historically movements challenged capitalism for higher wages which resulted in longer life expectancy and a decline in infectious diseases. The capitalists certainly don’t want these reforms if it means improved rights for workers and limits their ability to increase their profits. The capitalists are of course more than happy to use these reforms as examples of how good capitalism is, when in fact they resisted them and work to undo them. Some capitalists practice a form of Victoria philanthropy but still want to exploit their workers. In recent years life expectancy in Britain and the US has started to decline due to austerity and other reasons. [9]

And to quote Ha-Joon Chang:

“The average US citizen does have greater command over goods and services than his counterpart in any other country in the world except Luxemburg. However, given the country’s high inequality, this average is less accurate in representing how people live than the averages for other countries with a more equal income distribution. Higher inequality is also behind the poorer health indicators and worse crime statistics of the US. Moreover, the same dollar buys more things in the US than in most other rich countries mainly because it has cheaper services than in other comparable countries, thanks to higher immigration and poorer employment conditions. Furthermore, Americans work considerably longer than Europeans. Per hour worked, their command over goods and services is smaller than that of several European countries. While we can debate which is a better lifestyle – more material goods with less leisure time (as in the US) or fewer material goods with more leisure time (as in Europe) – this suggests that the US does not have an unambiguously higher living standard than comparable countries.” [10]

In terms of happiness, people are not stupid. They understand that they don’t have any influence on the direction of society, that things are going to be worse for future generations but there isn’t anything they can do about it. Buying more stuff and going on more holidays is a consolation prize that stops people looking for real change. Also, the number of antidepressant prescriptions doubled between 2008 and 2018, not a sign that people are happy.

Myth – as capitalism increases the size of the economy, everyone benefits

Capitalism results in exponential economic growth, so the arguement goes that this allows companies and individuals to benefit. This relates to the idea of, ‘A rising tide lifts all boats’ and ‘trickle-down economics‘ , where if the rich get richer, then this will benefit everyone.

And to quote Ha-Joon Chang:

“The above idea, known as ‘trickle-down economics’, stumbles on its first hurdle. Despite the usual dichotomy of ‘growth-enhancing pro-rich policy’ and ‘growth-reducing pro- poor policy’, pro-rich policies have failed to accelerate growth in the last three decades. So the first step in this argument – that is, the view that giving a bigger slice of pie to the rich will make the pie bigger – does not hold. The second part of the argument – the view that greater wealth created at the top will eventually trickle down to the poor – does not work either. Trickle down does happen, but usually its impact is meagre if we leave it to the market.” [11]

Myth – free-market capitalism is the best way to run the global economy

Capitalism produces a wide range of goods and services based on what is wanted or can solve a problem. It is argued that capitalism is economically efficient because it creates incentives to provide goods and services efficiently. The competitive market forces companies to improve how they are organised and use resources efficiently. [12]

This needs to be broken down into several arguments: the instability of capitalism, free-market vs state planning, free-market economics has only been applied in non-Western countries, corporations need to be regulated, where technology innovation happens, the impact of unlimited economic growth on the environment/planet.

Instability

Since the 1970s government have focused on ensuring price stability by managing inflation. This has not resulted in the stability of the world economy as the 2008 financial crisis shows. [13] Instability and crisis are part of the capitalist economic system. It is a cycle that starts when the memory of past economic crises fade and financial institutions figure out ways to circumvent the regulations that were put in place to stop them happening again. Rising asset prices reduce the cost of borrowing, resulting in market euphoria and risks being underestimated. Lots of money is being made and everyone wants their share of the growing economic boom (Richard Wolff Financial Panics, then and now in Capitalism Hits the Fan). Capitalism also needs crises so that businesses and wealth are destroyed, which lays the foundations for the next cycle of economic growth to start. This is known as ‘creative destruction‘.

There is also the argument that financial markets need to become more efficient so they can respond to changing opportunities and grow faster. Basically that there should not be any state restrictions on financial markets.

And to quote Ha-Joon Chang in 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism:

“The problem with financial markets today is that they are too efficient. With recent financial ‘innovations’ that have produced so many new financial instruments, the financial sector has become more efficient in generating profits for itself in the short run. However, as seen in the 2008 global crisis, these new financial assets have made the overall economy, as well as the financial system itself, much more unstable. Moreover, given the liquidity of their assets, the holders of financial assets are too quick to respond to change, which makes it difficult for real-sector companies to secure the ‘patient capital’ that they need for long-term development. The speed gap between the financial sector and the real sector needs to be reduced, which means that the financial market needs to be deliberately made less efficient.” [14]

free-market vs state planning

This myth is best dealt with by Ha-Joon Chang. He explains that there is no such thing as a free market. First, he describes the capitalist free market argument:

“Markets need to be free. When the government interferes to dictate what market participants can or cannot do, resources cannot flow to their most efficient use. If people cannot do the things that they find most profitable, they lose the incentive to invest and innovate. Thus, if the government puts a cap on house rents, landlords lose the incentive to maintain their properties or build new ones. Or, if the government restricts the kinds of financial products that can be sold, two contracting parties that may both have benefited from innovative transactions that fulfil their idiosyncratic needs cannot reap the potential gains of free contract. People must be left ‘free to choose’, as the title of free-market visionary Milton Friedman’s famous book goes.”

His response is:

“The free market doesn’t exist. Every market has some rules and boundaries that restrict freedom of choice. A market looks free only because we so unconditionally accept its underlying restrictions that we fail to see them. How ‘free’ a market is cannot be objectively defined. It is a political definition. The usual claim by free-market economists that they are trying to defend the market from politically motivated interference by the government is false. Government is always involved and those free-marketeers are as politically motivated as anyone. Overcoming the myth that there is such a thing as an objectively defined ‘free market’ is the first step towards understanding capitalism.” [15]

Robert Reich in Saving Capitalism: For The Many, Not The Few explains how the free market idea has poisoned peoples minds so that they think the negative impacts of the free market are simply unfortunate but impersonal outcomes of market forces. When in fact these outcomes benefit governing class and wealthy interests. [16]

Another challenge to the free market myth is that: “in order to secure profits, and to maintain their position of privilege against potential rivals, capitalists (both individuals and institutions) will frequently work to secure monopoly control of particular economic sectors, limiting invention and production within those sectors.” [17]

Capitalists argue against market regulation and claim that governments can’t pick winners. States construct markets, they enforce contracts, provide basic services and support the monetary system that is required for economic activity to take place. Importantly, they do this in a way that favours certain interests over others. [18]

The 2008 and 2020 economic crises have shown how capitalists advocate the free market as the only way to run the economy until a crisis comes along. At that point, they want state support and bailouts. This is known as “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor”, “Socialize Costs, Privatize Profits” and ‘lemon socialism‘. This is a good video of Richard Wolff on how American capitalism is just socialism for the rich.

We are told that we are not smart enough to leave things to the market. Ha-Joon Chang summarises this argument:

“We should leave markets alone, because, essentially, market participants know what they are doing – that is, they are rational. Since individuals (and firms as collections of individuals who share the same interests) have their own best interests in mind and since they know their own circumstances best, attempts by outsiders, especially the government, to restrict the freedom of their actions can only produce inferior results. It is presumptuous of any government to prevent market agents from doing things they find profitable or to force them to do things they do not want to do, when it possesses inferior information.”

His response to this myth:

“People do not necessarily know what they are doing, because our ability to comprehend even matters that concern us directly is limited – or, in the jargon, we have ‘bounded rationality’. The world is very complex and our ability to deal with it is severely limited. Therefore, we need to, and usually do, deliberately restrict our freedom of choice in order to reduce the complexity of problems we have to face. Often, government regulation works, especially in complex areas like the modern financial market, not because the government has superior knowledge but because it restricts choices and thus the complexity of the problems at hand, thereby reducing the possibility that things may go wrong.” [19]

Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski state that: “perhaps the strongest argument ever mounted against the left by the right is that the calculation and coordination involved in running a complex economy to satisfy disparate human needs and desires simply could not be consciously carried out. Only decentralised price signals operating through the market, miraculously aggregating an infinitude of disparate information, could guide an economy without dramatic failures, misallocations, and ultimately, authoritarian disasters.” They describe how the Second World War saw governments solve complex coordination problems. [20] In their book, People’s Republic of Walmart: How the World’s Biggest Corporations are Laying the Foundation for Socialism, they explain how most Western economies are centrally planned.

Ha-Joon Chang explains that despite the fall of communism, we are still living in planned economies. The capitalist argument goes:

“The limits of economic planning have been resoundingly demonstrated by the fall of communism. In complex modern economies, planning is neither possible nor desirable. Only decentralized decisions through the market mechanism, based on individuals and firms being always on the lookout for a profitable opportunity, are capable of sustaining a complex modern economy. We should do away with the delusion that we can plan anything in this complex and ever- changing world. The less planning there is, the better.”

Ha-Joon Chang response is:

“Capitalist economies are in large part planned. Governments in capitalist economies practise planning too, albeit on a more limited basis than under communist central planning. All of them finance a significant share of investment in R&D and infrastructure. Most of them plan a significant chunk of the economy through the planning of the activities of state-owned enterprises. Many capitalist governments plan the future shape of individual industrial sectors through sectoral industrial policy or even that of the national economy through indicative planning. More importantly, modern capitalist economies are made up of large, hierarchical corporations that plan their activities in great detail, even across national borders. Therefore, the question is not whether you plan or not. It is about planning the right things at the right levels.” [21]

Free market economics has only been applied in non-Western countries

Noam Chomsky explains that pure free-market economics (he calls it Laissez-faire principles) has only been applied to non-Western countries. Attempts by Western governments to try it have gone badly and been reversed.

Corporations need to be regulated

We are told that a strong economy needs corporations to do well. Ha-Joon Chang explains the argument:

“At the heart of the capitalist system is the corporate sector. This is where things are produced, jobs created and new technologies invented. Without a vibrant corporate sector, there is no economic dynamism. What is good for business, therefore, is good for the national economy. Especially given the increasing international competition in a globalizing world, countries that make opening and running businesses difficult or make firms do unwanted things will lose investment and jobs, eventually falling behind. Government needs to give the maximum degree of freedom to business.”

His response:

“Despite the importance of the corporate sector, allowing firms the maximum degree of freedom may not even be good for the firms themselves, let alone the national economy. In fact, not all regulations are bad for business. Sometimes, it is in the long-run interest of the business sector to restrict the freedom of individual firms so that they do not destroy the common pool of resources that all of them need, such as natural resources or the labour force. Regulations can also help businesses by making them do things that may be costly to them individually in the short run but raise their collective productivity in the long run – such as the provision of worker training. In the end, what matters is not the quantity but the quality of business regulation.” [22]

There is also the myth about the need to maximise shareholder value over the performance of the company. This results in managers focusing on increasing the share value instead of business performance. They are of course related but this approach results in managers making decisions that have negative effects on the company performance. [23]

Innovation

The capitalist argument is made by conservative MP Chris (failing) Grayling:

“If you believe in capitalism and free enterprise, then you believe that by allowing people to pursue success for themselves you create a culture of innovation and competition which benefits the whole of society. Free enterprise, business innovating in products and services, benefits the whole of our society.”

Although technological dynamism has been a strong argument for capitalism, investing in research and development it is too risky and takes too long for most capitalists to fund. The majority is publicly funded. [24]

Jeremy Gilbert argues that the creativity that leads to artistic, scientific or utilitarian inventions is not created by capitalism but instead from human interaction on the edges of capital. Then capital feeds on this creativity and transforms it into products to sell. This is why capital must locate itself near great centres of collective exchange and creativity such as London and Paris in the 19th century, New York and California in the 20th century. [25]

the impact of unlimited economic growth on the environment

It’s not possible to have infinite economic growth on a finite planet. [26] Capitalism requires that the economy grows each year. This requires that this year more things need to be made, more energy needs to be used and more people need to be born than last year. Then next year, more of all this is needed than this year.

Myth – capitalist economic theory is the best

Richard Wolff and Stephen Resnick summarise neoclassical theory’s contribution as:

“The originality of neoclassical theory lies in its notion that innate human nature determines economic outcomes. According to this notion, human beings naturally possess the inherent rational and productive abilities to produce the maximum wealth possible in a society. What they need and have historically sought is a kind of optimal social organization—a set of particular social institutions—that will free and enable this inner human essence to realize its potential, namely the greatest possible well-being of the greatest number. Neoclassical economic theory defines each individual’s well-being in terms of his or her consumption of goods and services: maximum consumption equals maximum well-being.

Capitalism is thought to be that optimum society. Its defining institutions (individual freedom, private property, a market system of exchange, etc.) are believed to yield an economy that achieves the maximum, technically feasible output and level of consumption. Capitalist society is also harmonious: its members’ different desires—for maximum enterprise profits and for maximum individual consumption—are brought into equilibrium or balance with one another.” [27]

Economics as a subject is based only on the theories of those who support it. University courses in economics are only taught by those that support capitalism. They do not teach the significant problems with capitalism or the viable alternatives. [28]

Ha-Joon Chang in 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism explains that good economic policy does not require good economists. That the most successful economic bureaucrats are not normally economists, giving examples of Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan. [29]

The author of Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy, Anatole Kaletsky recommends Beyond Mechanical Markets: Asset Price Swings, Risk, and the Role of the State by Roman Frydman and Michael D. Goldberg, which unpacks the economic assumptions mainstream economics is based on. Markets are not predictably rational or irrational. They argue instead that price swings are driven by individuals’ ever-imperfect interpretations of the significance of economic fundamentals for future prices and risk. [30]

Myth – capitalism maintains low taxes, which is good for workers and businesses

The arguement goes that low business taxes encourage companies to stay in a country and provide more jobs by reinvesting the money they would pay in tax into the company. Some also argue that low business tax generates more tax for the government. [31]

Some capitalists would prefer to pay no taxes at all. But the capitalists need the things that taxes pay for: police, schools, healthcare, transport systems. These public goods support capitalist society so there are workers to employ (exploit). [32] They also need the welfare state and public services to ensure capitalism’s survival and people do not become so desperate that they rise up and revolt.

The argument goes that low business tax (corporation tax) result in more business starting up so more jobs. Also, the advocates of low corporation tax state that low tax means businesses will reinvest to make it more competitive, [33] instead of giving shareholders a dividend. For this reinvestment argument to add up then the UK would not have the lowest worker productivity rates in the last 250 years or compared to other countries in Europe. The first article puts the drop in productivity down to: the lasting effect of the 2008 crisis for the financial system; weaker gains from computer technologies in recent years after a boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s; and intense uncertainty over post-Brexit trading relationships sapping business investment. The second article explains the decline is due to: less investment in equipment and infrastructure within the business; less spent on research and development; poor national infrastructure (roads and rail networks); and a lack of trade skills, basic literacy and numeracy skills, and lack of managerial competence.

These companies should be reinvesting in there business with more equipment, infrastructure and training. Add to this that the other issues listed in these articles can be resolved by the government but they choose not to because capitalists do not want highly skilled and well-paid workers, only working four days a week because that would give people time to start thinking and organising for how to make society better. [34] This article argues that reducing the corporate tax rate does not increase worker wages or business reinvestment.

There is also the myth/argument that if you increase taxes then the rich and businesses will relocate abroad. This article shows that the rich do not leave if you increase taxes. Also if businesses are going to relocate this will be to reduce the worker wages costs or where environmental regulations are less strict.

This telegraph article [35] from 2015 explains that corporation tax received by the government was up by 12% compared to 2014, even though the corporation tax percentage had dropped. The article does explain that company profits were up, partly because there was little wage growth. Corporation tax is based on the amount of profits a company takes. So while workers are struggling on low wages, UK company shareholders are taking more profits. It also explains that the UK has a lot more start-up companies that in the past. This is just what capitalists want, loads of small business owners who are more conservative, risk-averse and want the status quo to be maintained. This article does drone on about how unfair it is to say that companies don’t pay their fair share. Most people know that most companies pay their taxes. That complaint is directed at Amazon, Apple and the other tax-dodging big players. This article makes the case that cutting corporation tax costs the government billions.

Ha-Joon Chang challenges the capitalist myth that big government is bad for the economy. He explains that “A well-designed welfare state can actually encourage people to take chances with their jobs and be more, not less, open to changes.” [36]

Myth – capitalism promotes equality, work hard and you’ll get rich

This is the ‘American Dream’ idea that you may start poor but if you work hard, you can be successful and rich. This is also known as meritocracy. [37]

The equality that this refers to is the equality of opportunity. Ha-Joon Chang describes the capitalist argument:

“Many people get upset by inequality. However, there is equality and there is equality. When you reward people the same way regardless of their efforts and achievements, the more talented and the harder-working lose the incentive to perform. This is equality of outcome. It’s a bad idea, as proven by the fall of communism. The equality we seek should be the equality of opportunity. For example, it was not only unjust but also inefficient for a black student in apartheid South Africa not to be able to go to better, ‘white’, universities, even if he was a better student. People should be given equal opportunities. However, it is equally unjust and inefficient to introduce affirmative action and begin to admit students of lower quality simply because they are black or from a deprived background. In trying to equalize outcomes, we not only misallocate talents but also penalize those who have the best talent and make the greatest efforts.”

His response:

“Equality of opportunity is the starting point for a fair society.

But it’s not enough. Of course, individuals should be rewarded for better performance, but the question is whether they are actually competing under the same conditions as their competitors. If a child does not perform well in school because he is hungry and cannot concentrate in class, it cannot be said that the child does not do well because he is inherently less capable. Fair competition can be achieved only when the child is given enough food – at home through family income support and at school through a free school meals programme. Unless there is some equality of outcome (i.e., the incomes of all the parents are above a certain minimum threshold, allowing their children not to go hungry), equal opportunities (i.e., free schooling) are not truly meaningful.” [38]

Economic equality is really what we need to be concerned about. Danny Dorling describes how “The gap between the very rich and the rest is wider in Britain than in any other large country in Europe, and society is the most unequal it has been since shortly after the First World War.” [39]

The benefits for this myth for the capitalists is that it gives workers some hope that things can be better if they work that bit harder to chase the material benefits. It rewards some to keep the dream alive. It is also a cover for the business owners, managers and shareholders to justify their wealthy position. They can say they earned their money through hard work. Of course many inherited their wealth. [40]

There is also the capitalist myth that low worker wages mean lower prices for consumers. This has some truth in it but it is mainly a justification for low worker wages and high business managers wages. By this logic, higher manager wages result in higher consumer prices but there is generally lower investment in production costs (equipment and infrastructure). This results in low worker wages and fewer jobs [41]

Ha-Joon Chang in 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism describes how US managers are over-priced:

“US managers are over-priced in more than one sense. First, they are over-priced compared to their predecessors. In relative terms (that is, as a proportion of average worker compensation), American CEOs today are paid around ten times more than their predecessors of the 1960s, despite the fact that the latter ran companies that were much more successful, in relative terms, than today’s American companies. US managers are also over-priced compared to their counterparts in other rich countries. In absolute terms, they are paid, depending on the measure we use and the country we compare with, up to twenty times more than their competitors running similarly large and successful companies. American managers are not only over-priced but also overly protected in the sense that they do not get punished for poor performance. And all this is not, unlike what many people argue, purely dictated by market forces. The managerial class in the US has gained such economic, political and ideological power that it has been able to manipulate the forces that determine its pay.” [42]

Myth – capitalism fits well with human nature

The arguments goes that humans are naturally selfish, greedy and competitive. People that work hard are successful and outcompete their competitors, and are therefore rewarded financially. Capitalism also allows for other aspects of human nature such as altruism, patience and kindness. This is done through the creation of welfare systems and charities. [43]

Robert Jensen’s response to this is:

“There is a theory behind contemporary capitalism. We’re told that because we are greedy, self-interested animals, an economic system must reward greedy, self-interested behavior if we are to thrive economically. Are we greedy and self-interested? Of course. At least I am, sometimes. But we also just as obviously are capable of compassion and selflessness. We certainly can act competitively and aggressively, but we also have the capacity for solidarity and cooperation. In short, human nature is wide-ranging. Our actions are certainly rooted in our nature, but all we really know about that nature is that it is widely variable. In situations where compassion and solidarity are the norm, we tend to act that way. In situations where competitiveness and aggression are rewarded, most people tend toward such behavior. Why is it that we must choose an economic system that undermines the most decent aspects of our nature and strengthens the most inhuman? Because, we’re told, that’s just the way people are. What evidence is there of that? Look around, we’re told, at how people behave. Everywhere we look, we see greed and the pursuit of self-interest. So, the proof that these greedy, self-interested aspects of our nature are dominant is that, when forced into a system that rewards greed and self-interested behavior, people often act that way. Doesn’t that seem just a bit circular?”

And Ha-Joon Chang response to capitalism’s human nature arguement is:

“Self-interest is a most powerful trait in most human beings. However, it’s not our only drive. It is very often not even our primary motivation. Indeed, if the world were full of the self- seeking individuals found in economics textbooks, it would grind to a halt because we would be spending most of our time cheating, trying to catch the cheaters, and punishing the caught. The world works as it does only because people are not the totally self-seeking agents that free-market economics believes them to be. We need to design an economic system that, while acknowledging that people are often selfish, exploits other human motives to the full and gets the best out of people. The likelihood is that, if we assume the worst about people, we will get the worst out of them.” [44]

Myth – capitalism and democracy work well together

The argument goes that capitalism is built on democracy. Everyone gets one vote so they have equal political power, which is not affected by their race, gender or views. Capitalism also encourages people to get involved in all aspects of society to get what they want. This includes getting involved with both governance and the government, from voting in elections to standing in local or national elections. [45]

Robert Jensen explains how capitalism is anti-democratic:

“This one is easy. Capitalism is a wealth-concentrating system. If you concentrate wealth in a society, you concentrate power. Is there any historical example to the contrary? For all the trappings of formal democracy in the contemporary United States, everyone understands that the wealthy dictates the basic outlines of the public policies that are acceptable to the vast majority of elected officials. People can and do resist, and an occasional politician joins the fight, but such resistance takes extraordinary effort. Those who resist win victories, some of them inspiring, but to date concentrated wealth continues to dominate. Is this any way to run a democracy? If we understand democracy as a system that gives ordinary people a meaningful way to participate in the formation of public policy, rather than just a role in ratifying decisions made by the powerful, then it’s clear that capitalism and democracy are mutually exclusive. Let’s make this concrete. In our system, we believe that regular elections with the one-person/one-vote rule, along with protections for freedom of speech and association, guarantee political equality. When I go to the polls, I have one vote. When Bill Gates goes the polls, he has one vote. Bill and I both can speak freely and associate with others for political purposes. Therefore, as equal citizens in our fine democracy, Bill and I have equal opportunities for political power. Right?”

Not everyone does get to vote, some such as criminals no longer have that right. Many don’t bother to vote as the options between several capitalist political parties feel very limited. Government can’t go against global capitalism as the Greek Syriza government found out when it tried to reject austerity in 2015. There is also the problems and unfairness of the First Past the Post voting system, which benefits rightwing, extreme pro-capitalist parties. Also, these parties do better in elections when voter turnout is lower. [46]

Richard Wolff makes the point that we spend half of our time in undemocratic companies. A small group of people (boards of directors and shareholders) make decisions in businesses that affect the workers such as if the business shuts down and moves overseas, who loses their job and who gets the profits. But the workers do not have any say in these decisions. Outside the workplace, people get to vote in our local communities and national government. [47]

Ha-Joon Chang explains that companies should not be run in the interest of their owners:

“Shareholders may be the owners of corporations but, as the most mobile of the ‘stakeholders’, they often care the least about the long-term future of the company (unless they are so big that they cannot really sell their shares without seriously disrupting the business). Consequently, shareholders, especially but not exclusively the smaller ones, prefer corporate strategies that maximize short-term profits, usually at the cost of long-term investments, and maximize the dividends from those profits, which even further weakens the long-term prospects of the company by reducing the amount of retained profit that can be used for re-investment. Running the company for the shareholders often reduces its long-term growth potential.” [48]

Myth – Capitalism gradually balances differences across countries through free markets and free trade.

The arguement goes that countries can use their competitive advantage to benefit themselves and also access goods and services from the rest of the world. [49]

Ha-Joon Chang describes how free-market policies rarely make poor countries rich. The capitalist argument is:

“After their independence from colonial rule, developing countries tried to develop their economies through state intervention, sometimes even explicitly adopting socialism. They tried to develop industries such as steel and automobiles, which were beyond their capabilities, artificially by using measures such as trade protectionism, a ban on foreign direct investment, industrial subsidies, and even state ownership of banks and industrial enterprises. At an emotional level this was understandable, given that their former colonial masters were all capitalist countries pursuing free-market policies. However, this strategy produced at best stagnation and at worst disaster. Growth was anaemic (if not negative) and the protected industries failed to ‘grow up’. Thankfully, most of these countries have come to their senses since the 1980s and come to adopt free-market policies. When you think about it, this was the right thing to do from the beginning. All of today’s rich countries, with the exception of Japan (and possibly Korea, although there is debate on that), have become rich through free-market policies, especially through free trade with the rest of the world. And developing countries that have more fully embraced such policies have done better in the recent period.

His response:

“Contrary to what is commonly believed, the performance of developing countries in the period of state-led development was superior to what they have achieved during the subsequent period of market-oriented reform. There were some spectacular failures of state intervention, but most of these countries grew much faster, with more equitable income distribution and far fewer financial crises, during the ‘bad old days’ than they have done in the period of market- oriented reforms. Moreover, it is also not true that almost all rich countries have become rich through free-market policies. The truth is more or less the opposite. With only a few exceptions, all of today’s rich countries, including Britain and the US – the supposed homes of free trade and free market – have become rich through the combinations of protectionism, subsidies and other policies that today they advise the developing countries not to adopt. Free-market policies have made few countries rich so far and will make few rich in the future.” [50]

Endnotes

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Ha-Joon Chang, 2011, introduction

- https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

- Jody Dean 11m https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZhUvNkJve-w

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Commune#Casualties; Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune of 1871, John M. Merriman, 2016; https://libcom.org/history/1871-the-paris-commune)

- #ACFM episode – Trip 10 How It Feels to Be Free, from 11m https://novaramedia.com/2020/05/10/trip-10-how-it-feels-to-be-free/

- #ACFM episode – Trip 10 How It Feels to Be Free, from 13m https://novaramedia.com/2020/05/10/trip-10-how-it-feels-to-be-free/

- #ACFM episode – Trip 10 How It Feels to Be Free, from 36 mins https://novaramedia.com/2020/05/10/trip-10-how-it-feels-to-be-free/

- #ACFM episode – Trip 10 How It Feels to Be Free, from 14m https://novaramedia.com/2020/05/10/trip-10-how-it-feels-to-be-free/

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jun/23/why-is-life-expectancy-falling, https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/11/peak-life-expectancy.html, https://www.workers.org/2018/12/40054/

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Ha-Joon Chang, 2011, thing 10)

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 13

- https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 6

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 22

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 1

- https://www.alternet.org/2015/09/robert-reich-capitalism-can-be-reformed-americas-wealthy-class-will-fight-it/

- Anticapitalism and Culture: Radical Theory and Popular Politics, Jeremy Gilbert, 2008, page 108, also see Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy, Anatole Kaletsky, 2011, <ahref=”https://www.alternet.org/2015/09/robert-reich-capitalism-can-be-reformed-americas-wealthy-class-will-fight-it/” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”>https://www.alternet.org/2015/09/robert-reich-capitalism-can-be-reformed-americas-wealthy-class-will-fight-it/

- Tribune Magazine, Spring 2020 The Era of State-Monopoly Capitalism, Grace Blakely page 29, https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/06/the-era-of-state-monopoly-capitalism

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 16

- Tribune Magazine, Spring 2020, Planning the Future page 69, https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/07/planning-the-future

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 19

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 18

- https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/maximising-shareholder-value-irony

- https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/03/socialism-innovation-capitalism-smith/

- Anticapitalism and Culture, page 109

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXxVj9MHaCw, Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change, William R. Catton Jr, 1982, https://www.counterpunch.org/2007/04/30/anti-capitalism-in-five-minutes/

- Contending Economic Theories: Neoclassical, Keynesian, Marxian, Richard Wolff and Stephen Resnick, 2012, page 52

- Richard Wolff 44m https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UMbw0d-ebo0&t=289s)

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 23

- https://fivebooks.com/best-books/new-capitalism-anatole-kaletsky/ and https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B004P1JEZW/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_bibl_vppi_i0

- https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

- Richard D. Wolff Lecture on Worker Coops: Theory and Practice of 21st Century Socialism https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1WUKahMm1s 46m

- https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/corporation-tax-cut/

- see Capitalist class project section from https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/04/29/what-is-neoliberalism/

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11498135/Why-lower-corporation-tax-means-more-for-Treasury.html – download word doc of article Why lower corporation tax means more for Treasury

-

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 21

-

https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

-

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 20

-

https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2018/07/peak-inequality

-

(Capitalism say ‘we earned it’ Richard Wolff Marxism 101 27m and justification why employer paid so much RW Understanding Marxism 117m

-

Capitalism Hits the Fan, Richard Wolff, 2010, Real Costs of Exec Money Grabs

-

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 14

-

https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

-

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 5

-

https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

-

https://behindthenumbers.ca/2011/04/14/who-benefits-from-low-voter-turnout/

-

Richard Wolff 21m https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ynbgMKclWWc

-

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 2

-

https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/07/31/why-do-people-support-capitalism/

-

23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, thing 7

by DGR News Service | Sep 7, 2021 | Building Alternatives, Education, Strategy & Analysis

This article is from the blog buildingarevolutionarymovement.

In this post I’ll explain why people say they support capitalism and then the actual reasons why people support capitalism. To end capitalism we need to understand why people support it. I’m listing the positives in the post that I don’t agree with. In future posts I’ll describe the myths of capitalism and the reasons why we need an alternative.

It’s easy and common to conflate capitalism, liberalism, neoliberalism and free market economics. Many use them interchangeably and I’m going to go with that for this post.

Why people say they support capitalism

There isn’t a viable alternative economic system. Capitalism’s supporters agree that capitalism isn’t perfect but it’s all we’ve got. [1]

The moral argument for capitalism is based on individual freedom being a natural right that pre-exists society. Society is valued and justified because it benefits humans and enhances economic freedom, instead of limiting it.

The practical argument for capitalism is that many forms of centrally controlled governments have been tried and failed. Therefore privately owned and controlled means of production is the only viable way to run economies. [2]

Everything is better under capitalism. Capitalism has resulted in improved basic standards of living, reduction in poverty and increased life expectancy. There is also the argument that Western capitalist countries have the happiest populations because they can consume whatever products and services they like. [3]

Economics arguments. Capitalism results in exponential growth, which allows companies and individuals to benefit. This relates to the idea of, ‘A rising tide lifts all boats’, where if the rich get richer, then this will benefit everyone. Capitalism produces a wide range of goods and services based on what is wanted or can solve a problem. It is argued that capitalism is economically efficient because it creates incentives to provide goods and services in an efficient way. The competitive market forces companies to improve how they are organised and use resources efficiently. [4]

In 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Ha-Joon Chang describes the free market ideology:

“We have been told that, if left alone, markets will produce the most efficient and just outcome. Efficient, because individuals know best how to utilize the resources they command, and just, because the competitive market process ensures that individuals are rewarded according to their productivity. We have been told that business should be given maximum freedom. Firms, being closest to the market, know what is best for their businesses. If we let them do what they want, wealth creation will be maximized, benefiting the rest of society as well. We were told that government intervention in the markets would only reduce their efficiency. Government intervention is often designed to limit the very scope of wealth creation for misguided egalitarian reasons. Even when it is not, governments cannot improve on market outcomes, as they have neither the necessary information nor the incentives to make good business decisions. In sum, we were told to put all our trust in the market and get out of its way.

Following this advice, most countries have introduced free-market policies over the last three decades – privatization of state-owned industrial and financial firms, deregulation of finance and industry, liberalization of international trade and investment, and reduction in income taxes and welfare payments. These policies, their advocates admitted, may temporarily create some problems, such as rising inequality, but ultimately they will make everyone better off by creating a more dynamic and wealthier society. The rising tide lifts all boats together, was the metaphor.” [5]

Capitalism has brought significant technology innovations. These included smartphones; the internet with rapid home delivery; streaming movies; social media; and automation has dramatically increased labour productivity. [6] Business invests in research and development to create better products and remain competitive. Employees work to improve their best practice to increase their productivity. [7] Supporters of capitalism argue that capitalism is very flexible and adaptable at dealing with society’s problems as they develop. An example would be climate change, with technologies such as renewables, carbon capture, nuclear power and geoengineering.

Capitalism is a social good and provides services to others. Selfishly working to make money means producing goods and services that others need. Even overpaid professions such as playing sport, or unpopular professions such as banking. This means that people can earn money and solve a problem for someone else. [8]

Capitalism promotes equality. This is the ‘American Dream’ idea that you may start out poor but if you work hard, you can be successful and rich. This is also known as meritocracy. [9]

Capitalism fits well with human nature. Humans are naturally selfish, greedy and competitive. People that work hard are successful and outcompete their competitors, and are therefore rewarded financially. Capitalism also allows for other aspects of human nature such as altruism, patience and kindness. This is done through the creation of welfare systems and charities. [10]

Capitalism and democracy work well together. Capitalism is built on democracy. Everyone gets one vote so they have equal political power, which is not affected by their race, gender or views. [11] Capitalism also encourages people to get involved in all aspects of society to get what they want. This includes getting involved with both governance and the government, from voting in elections, to standing in local or national elections. [12]

Capitalism gradually balances differences across countries through free markets and free trade. Countries can use their competitive advantage to benefit themselves and also access goods and services from the rest of the world. [13]

Capitalism maintains low taxes, which is good for workers and businesses. Low business taxes encourages companies to stay and provide more jobs by reinvesting the money they would pay in tax into the company. Some also argue that low business tax generates more tax for the government. [14]

Allan H. Meltzer, who wrote ‘Why Capitalism’, argues that capitalism has three strengths: economic growth, individual freedom, and it is adaptable to the many diverse cultures in the world. [15] He makes the case for capitalism in more detail:

“Capitalist systems are not rigid, nor are they all the same. Capitalism is unique in permitting change and adaptation, and so different societies tend to develop different forms of it. What all share is ownership of the means of production by individuals who remain relatively free to choose their activities, where they work, what they buy and sell, and at what prices. As an institution for producing goods and services, capitalism’s success rests on a foundation of a rule of law, which protects individual rights to property, and, in the first instance, aligns rewards to values produced. Working hand in hand with the rule of law, capitalism gives its participants incentives to act as society desires, typically rewarding hard work, intelligence, persistence and innovation. If too many laws work against this, capitalism may suffer disruptions. Capitalism embraces competition. Competition rewards those who build value, and buyers with choices and competitive prices. Like any system, capitalism has successes and failures—but it is the only system known to humanity that increases both growth and freedom. Instead of ending, as some critics suppose, capitalism continues to spread—and has spread to cultures as different as Brazil, Chile, China, Japan, and Korea. It is the only system humans have found in which personal freedom, progress and opportunities coexist. Most of the faults and flaws on which critics dwell are human faults. Capitalism is the only system that adapts to all manner of cultural and institutional differences. It continues to spread and adapt, and will for the foreseeable future.” [16]

Reasons why people actually support capitalism

So why do ordinary people continue to support capitalism or not actively seek an alternative economic system? This is a huge, complex question so I don’t plan to answer this in detail now. I do want to outline some broad reasons.

There is no alternative (tina). When Margaret Thatcher used this phrase, she meant that capitalism was the only viable economic and political system. In the 21st century it has become near impossible for most to imagine a coherent alternative to capitalism, this is known as ‘Capitalist Realism’. [17] The dominant narrative is that any attempts to organise societies in a non-capitalist way have been complete failures, and this has been accepted by many. Movements, leaders and parties which have attempted to reform capitalism by creating measures to bring about a fairer, more equal and less harsh society, have been attacked, distorted, misrepresented and finally crushed, examples being Corbynism in the UK, Bernie Sanders in the USA, and Syriza in Greece. This results in ‘disaffected consent,’ which I wrote about in this post. [18]

Need a job to pay bills. People are understandingly cautious about supporting an alternative to capitalism that might disrupt their lives and make things more difficult or worse. However unpopular and unstable capitalism is, it does allow a large number of people to live.

Want a fairer capitalism. Many that are struggling just want capitalism reformed to make their lives a bit better, rather than grand plans to change everything. These are seen as achievable, reasonable, small changes. Many are too busy trying to survive and provide for their families to engage with politics themselves – meetings, groups, campaigns are all too time consuming. They want this done for them by political parties.

Have not experienced collective struggle and don’t understand things could better under a different economic system. The left is historically weak, so many that want things to be better have no experience, knowledge, access and interest in left organisations and institutions, eg the trade unions. Many are anti-left and identify with the Tories.

Way out of poverty. For many born poor, capitalist society offers some that work hard and are lucky the chance to get rich, or if not rich then to have a comfortable lifestyle.

Personally benefit from capitalism. For those that enjoy the benefits of capitalism, this is a powerful motivator to keep things as they are. They have worked hard for their money and private property, and are looking forward to retirement with a pension plan. The Tories are the political party of capitalism. Many may not really like the Tories but they are perceived to be good at running the economy and maintaining the status quo. For many this is the deciding factor.

Bought off by consumption. The decline in real wages since the 1970s, and the lack of opportunities to make meaningful democratic inputs into political decision making, has been compensated by the expansion of consumption – homes, cars, electrical equipment, furniture, holidays etc. This has been made possible by the explosion of household debt and cheap goods from Asia. [19]

Economics as a subject is based only on the the theories of those who support it. University courses in economics are only taught by those that support capitalism. They do not teach the significant problems with capitalism or the viable alternatives. [20]

Endnotes

- https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/

- https://www.quora.com/What-are-the-strongest-arguments-in-defense-of-capitalism?share=1

- https://www.dailywire.com/news/5-statistics-showing-how-capitalism-solves-poverty-aaron-bandler, https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enlightenment_Now

- https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/, https://vittana.org/17-pros-and-cons-of-capitalism, https://netivist.org/debate/pros-and-cons-of-capitalism

- 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Ha-Joon Chang, 2010, Introduction

- https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/12/erik-olin-wright-real-utopias-anticapitalism-democracy/

- https://vittana.org/17-pros-and-cons-of-capitalism

- https://vittana.org/17-pros-and-cons-of-capitalism and https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/

- https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/ and https://vittana.org/17-pros-and-cons-of-capitalism

- https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/

- https://listverse.com/2010/12/24/top-10-greatest-benefits-of-capitalism/

- https://vittana.org/17-pros-and-cons-of-capitalism

- https://netivist.org/debate/pros-and-cons-of-capitalism

- https://www.conservativehome.com/thecolumnists/2018/04/chris-grayling-the-argument-for-capitalism-over-socialism-cannot-be-won-with-a-history-lesson.html and https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11498135/Why-lower-corporation-tax-means-more-for-Treasury.html – download word doc of article Why lower corporation tax means more for Treasury

- Why Capitalism, Allan Meltzer, 2012, page ix

- https://www.writersreps.com/Why-Capitalism

- Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher, 2009, page 2

- https://buildingarevolutionarymovement.org/2020/04/29/what-is-neoliberalism/

- Neoliberal Culutre, Jeremy Gilbert, 2016, page 25

- Richard D. Wolff Lecture on Worker Coops: Theory and Practice of 21st Century Socialism, 3 mins, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1WUKahMm1s

by DGR News Service | Aug 31, 2021 | Culture of Resistance, Education

This article is from the blog buildingarevolutionarymovement.

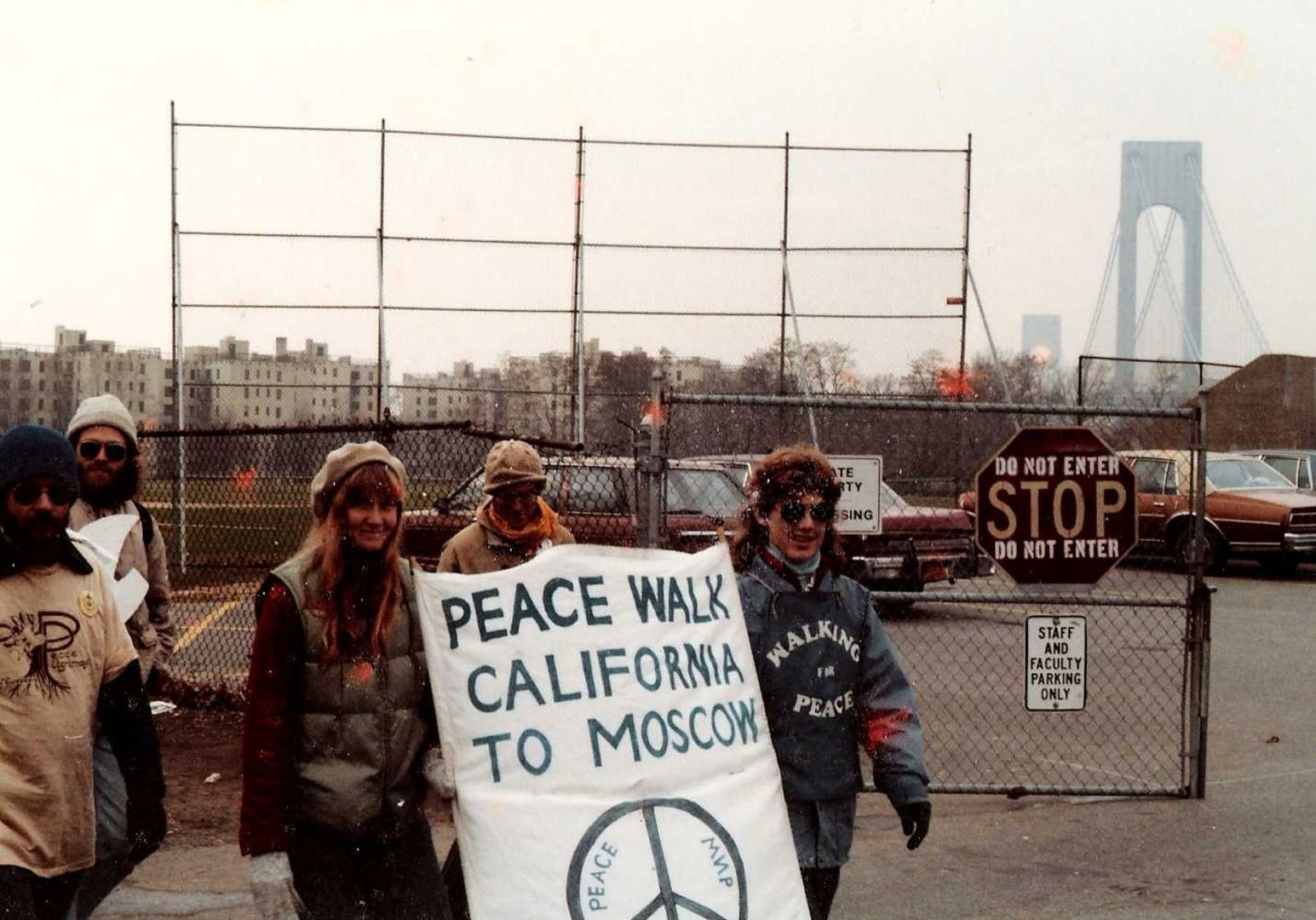

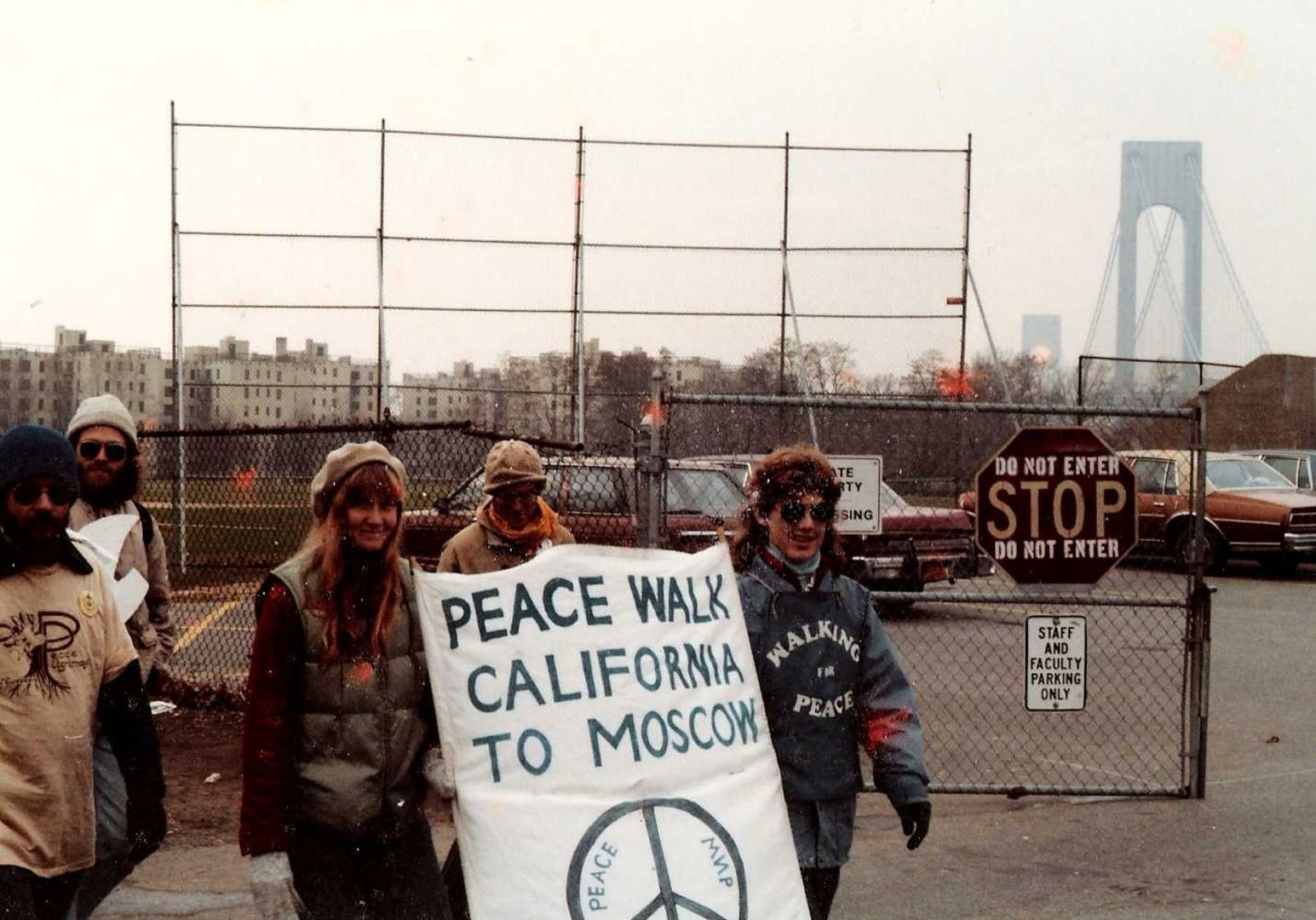

Featured image: Members of Walk of the People, a 7,000-mile peace walk from California to Russia, reach New York City in 1984. Photo by Kevin James Shay.

This post describes different types of social movements. These are broad classifications and generally social movements are made up from a combination of types. Their type can change at different points in the social movements lifecycle.

Reform movements seek to change some parts of society without completely transforming it. They normally exist in democratic societies where criticism of existing institutions is acceptable. Examples include environmental protection campaigns and introducing a minimum wage.

Revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of the existing social system and replace it with a greatly different one. These include Communist movements and the 1960s counterculture movement.

Redemptive movements are trying to find meaning and aim to create inner change or spiritual growth in people. Examples include Alcoholics Anonymous and the New Age movement.

Alternative movements are focused on self-improvement and changes to individual beliefs and behaviour. Examples include the local food movement and alternative health movement.

Resistance movements seek to block a planned change or undo a change already made to society. Examples include the Ku Klux Klan and pro-life movements.

Migratory movements are large numbers of people that leave a country and settle in another place. They are a migratory social movement when they have a shared focus of discontent, purpose, or goal to move to a new location. Examples of migratory social movements include the Zionist movement, Jews moved to Israel and the movement of people from East Germany to West Germany.

Utopian movements aim to create an ideal or perfect society which is in people’s imaginations but not in reality. It is based on the idea that people are basically good, cooperative and altruistic. Examples include the nineteenth-century Utopian socialist movements of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. Also the Sarvodaya movement. [1]

Political movements are collective attempts by groups of individuals to change government policy or society. This can include: “to extend the criteria for inclusion within decision making; to reveal and fight against bias that privileges certain interests over others within the political system; to gain access to and influence within existing decision-making processes; to open up new channels for the expression of previously excluded demands.” [2]

Cultural movements are movements of ideas and performances rather than interests and politics. They do not have a clear political focus; are not a reaction to collective interests, injustices or demands made by movements on the streets; they are more focused on artefacts and performances of mobilisations such as music, dress and shared experiences rather than marches, demonstrations and protests; these movements have great influences through public opinion and attitudes than through legislation or policy change. Examples include Romanticism and the Hippie movement. [3]

Antagonistic movements challenge society and its politics in fundamental ways. It questions the allocation of resources between social groups and classes, and the ideological and organisation basis of production, distribution and exchange of key social and economic goods. Examples include radical environmentalists critique of economic growth that is incompatible with environmental protection and anti-capitalist movements use of direct action for ideological reasons against liberal democracy instead of instrumental changes to influence policy. [4]

Claimant movements aims to change the distribution of resources, roles and rewards within society and organisations. Examples include the mobilisation of low waged workers, disabled campaigns for equal access to public buildings and transport, and campaigns to reduce the age of consent for homosexual sexual relations. [5]

Countermovements or countercultures attempt to create forms of expression and association which are opposed to mainstream cultural norms of society. Examples include the youth movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the North American Beat Generation. [6]

Defensive social movements attempt to defend established traditions, customs, practices, and forms of social interactions from changes due to modernisation. There are also known as Resistance movements. Examples include the German anti-nuclear movement, Ku Klux Klan and pro-life movements. [7]

Global social movements (Transnationalism) operate at the international level, coordinating activities and resources that is focused on a shared goal for social and political change. Globalisation has resulted in improved communications, international mobility and cultural exchange and global governance institutions and corporations. Examples include the anti-globalisation movement, global justice movement and fossil fuel divest movement. [8]