by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 9, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

What if some forms of limited resistance were undertaken? What if there was a serious aboveground resistance movement combined with a small group of underground networks working in tandem? (This still would not be a majority movement—this is extrapolation, not fantasy.) What if those movements combined their grand strategy? The abovegrounders would work to build sustainable and just communities wherever they were, and would use both direct and indirect action to try to curb the worst excesses of those in power, to reduce the burning of fossil fuels, to struggle for social and ecological justice. Meanwhile, the undergrounders would engage in limited attacks on infrastructure (often in tandem with aboveground struggles), especially energy infrastructure, to try to reduce fossil fuel consumption and overall industrial activity. The overall thrust of this plan would be to use selective attacks to accelerate collapse in a deliberate way, like shoving a rickety building.

If this scenario occurred, the first years would play out similarly. It would take time to build up resistance and to ally existing resistance groups into a larger strategy. Furthermore, civilization at the peak of its power would be too strong to bring down with only partial resistance. The years around 2011 to 2015 would still see the impact of peak oil and the beginning of an economic tailspin, but in this case there would be surgical attacks on energy infrastructure that limited new fossil fuel extraction (with a focus on the nastier practices like mountain-top removal and tar sands). Some of these attacks would be conducted by existing resistance groups (like MEND) and some by newer groups, including groups in the minority world of the rich and powerful. The increasing shortage of oil would make pipeline and infrastructure attacks more popular with militant groups of all stripes. During this period, militant groups would organize, practice, and learn.

These attacks would not be symbolic attacks. They would be serious attacks designed to be effective but timed and targeted to minimize the amount of “collateral damage” on humans. They would mostly constitute forms of sabotage. They would be intended to cut fossil fuel consumption by some 30 percent within the first few years, and more after that. There would be similar attacks on energy infrastructure like power transmission lines. Because these attacks would cause a significant but incomplete reduction in the availability of energy in many places, a massive investment in local renewable energy (and other measures like passive solar heating or better insulation in some areas) would be provoked. This would set in motion a process of political and infrastructural decentralization. It would also result in political repression and real violence targeting those resisters.

Meanwhile, aboveground groups would be making the most of the economic turmoil. There would be a growth in class consciousness and organization. Labor and poverty activists would increasingly turn to community sufficiency. Local food and self-sufficiency activists would reach out to people who have been pushed out of capitalism. The unemployed and underemployed—rapidly growing in number—would start to organize a subsistence and trade economy outside of capitalism. Mutual aid and skill sharing would be promoted. In the previous scenario, the development of these skills was hampered in part by a lack of access to land. In this scenario, however, aboveground organizers would learn from groups like the Landless Workers Movement in Latin America. Mass organization and occupation of lands would force governments to cede unused land for “victory garden”—style allotments, massive community gardens, and cooperative subsistence farms.

The situation in many third world countries could actually improve because of the global economic collapse. Minority world countries would no longer enforce crushing debt repayment and structural adjustment programs, nor would CIA goons be able to prop up “friendly” dictatorships. The decline of export-based economies would have serious consequences, yes, but it would also allow land now used for cash crops to return to subsistence farms.

Industrial agriculture would falter and begin to collapse. Synthetic fertilizers would become increasingly expensive and would be carefully conserved where they are used, limiting nutrient runoff and allowing oceanic dead zones to recover. Hunger would be reduced by subsistence farming and by the shift of small farms toward more traditional work by hand and by draft horse, but food would be more valuable and in shorter supply.

Even a 50 percent cut in fossil fuel consumption wouldn’t stave off widespread hunger and die-off. As we have discussed, the vast majority of all energy used goes to nonessentials. In the US, the agricultural sector accounts for less than 2 percent of all energy use, including both direct consumption (like tractor fuel and electricity for barns and pumps) and indirect consumption (like synthetic fertilizers and pesticides).12 That’s true even though industrial agriculture is incredibly inefficient and spends something like ten calories of fossil fuel energy for every food calorie produced. Residential energy consumption accounts for only 20 percent of US total usage, with industrial, commercial, and transportation consumption making up the majority of all consumption.13 And most of that residential energy goes into household appliances like dryers, air conditioning, and water heating for inefficiently used water. The energy used for lighting and space heating could be itself drastically reduced through trivial measures like lowering thermostats and heating the spaces people actually live in. (Most don’t bother to do these now, but in a collapse situation they will do that and more.)

Only a small fraction of fossil fuel energy actually goes into basic subsistence, and even that is used inefficiently. A 50 percent decline in fossil fuel energy could be readily adapted to form a subsistence perspective (if not financial one). Remember that in North America, 40 percent of all food is simply wasted. Of course, poverty and hunger have much more to do with power over people than with the kind of power measured in watts. Even now at the peak of energy consumption, a billion people go hungry. So if people are hungry or cold because of selective militant attacks on infrastructure, that will be a direct result of the actions of those in power, not of the resisters.

In fact, even if you want humans to be able to use factories to build windmills and use tractors to help grow food over the next fifty years, forcing an immediate cut in fossil fuel consumption should be at the top of your to-do list. Right now most of the energy is being wasted on plastic junk, too-big houses for rich people, bunker buster bombs, and predator drones. The only way to ensure there is some oil left for basic survival transitions in twenty years is to ensure that it isn’t being squandered now. The US military is the single biggest oil user in the world. Do you want to have to tell kids twenty years from now that they don’t have enough to eat because all the energy was spent on pointless neocolonial wars?

Back to the scenario. In some areas, increasingly abandoned suburbs (unlivable without cheap gas) would be taken over, as empty houses would become farmhouses, community centers, and clinics, or would be simply dismantled and salvaged for material. Garages would be turned into barns—most people couldn’t afford gasoline anyway—and goats would be grazed in parks. Many roads would be torn up and returned to pasture or forest. These reclaimed settlements would not be high-tech. The wealthy enclaves may have their solar panels and electric windmills, but most unemployed people wouldn’t be able to afford such things. In some cases these communities would become relatively autonomous. Their social practices and equality would vary based on the presence of people willing to assert human rights and social justice. People would have to resist vigorously whenever racism and xenophobia are used as excuses for injustice and authoritarianism.

Attacks on energy infrastructure would become more common as oil supplies diminish. In some cases, these attacks would be politically motivated, and in others they would be intended to tap electricity or pipelines for poor people. These attacks would steepen the energy slide initially. This would have significant economic impacts, but it would also turn the tide on population growth. The world population would peak sooner, and peak population would be smaller (by perhaps a billion) than it was in the “no resistance” scenario. Because a sharp collapse would happen earlier than it otherwise would have, there would be more intact land in the world per person, and more people who still know how to do subsistence farming.

The presence of an organized militant resistance movement would provoke a reaction from those in power. Some of them would use resistance as an excuse to seize more power to institute martial law or overt fascism. Some of them would make use of the economic and social crises rippling across the globe. Others wouldn’t need an excuse.

Authoritarians would seize power where they could, and try to in almost every country. However, they would be hampered by aboveground and underground resistance, and by decentralization and the emergence of autonomous communities. In some countries, mass mobilizations would stop potential dictators. In others, the upsurge in resistance would dissolve centralized state rule, resulting in the emergence of regional confederations in some places and in warlords in others. In unlucky countries, authoritarianism would take power. The good news is that people would have resistance infrastructure in place to fight and limit the spread of authoritarians, and authoritarians would have not developed as much technology of control as they did in the “no resistance” scenario.

There would still be refugees flooding out of many areas (including urban areas). The reduction in greenhouse gas emissions caused by attacks on industrial infrastructures would reduce or delay climate catastrophe. Networks of autonomous subsistence communities would be able to accept and integrate some of these people. In the same way that rooted plants can prevent a landslide on a steep slope, the cascades of refugees would be reduced in some areas by willing communities. In other areas, the numbers of refugees would be too much to cope with effectively.14

The development of biofuels (and the fate of tropical forests) is uncertain. Remaining centralized states—though they may be smaller and less powerful—would still want to squeeze out energy from wherever they could. Serious militant resistance—in many cases insurgency and guerilla warfare—would be required to stop industrialists from turning tropical forests into plantations or extracting coal at any cost. In this scenario, resistance would still be limited, and it is questionable whether that level of militancy would be effectively mustered.

This means that the long-term impacts of the greenhouse effect would be uncertain. Fossil fuel burning would have to be kept to an absolute minimum to avoid a runaway greenhouse effect. That could prove very difficult.

But if a runaway greenhouse effect could be avoided, many areas could be able to recover rapidly. A return to perennial polycultures, implemented by autonomous communities, could help reverse the greenhouse effect. The oceans would look better quickly, aided by a reduction in industrial fishing and the end of the synthetic fertilizer runoff that creates so many dead zones now.

The likelihood of nuclear war would be much lower than in the “no resistance” scenario. Refugee cascades in South Asia would be diminished. Overall resource consumption would be lower, so resource wars would be less likely to occur. And militaristic states would be weaker and fewer in number. Nuclear war wouldn’t be impossible, but if it did happen, it could be less severe.

There are many ways in which this scenario is appealing. But it has problems as well, both in implementation and in plausibility. One problem is with the integration of aboveground and underground action. Most aboveground environmental organizations are currently opposed to any kind of militancy. This could hamper the possibility of strategic cooperation between underground militants and aboveground groups that could mobilize greater numbers. (It would also doom our aboveground groups to failure as their record so far demonstrates.)

It’s also questionable whether the cut in fossil fuel consumption described here would be sufficient to avoid runaway global warming. If runaway global warming does take place, all of the beneficial work of the abovegrounders would be wiped out. The converse problem is that a steeper decline in fossil fuel consumption would very possibly result in significant human casualties and deprivation. It’s also possible that the mobilization of large numbers of people to subsistence farming in a short time is unrealistic. By the time most people are willing to take that step, it could be too late.

So while in some ways this scenario represents an ideal compromise—a win-win situation for humans and the planet—it could just as easily be a lose-lose situation without serious and timely action. That brings us to our last scenario, one of all-out resistance and attacks on infrastructure intended to guarantee the survival of a livable planet.

Continue reading at Scenario: All-Out Infrastructure Attack

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 5, 2018 | The Solution: Resistance

Featured image: Occupy Wall Street. Wikipedia

by Derrick Jensen

We hold these truths to be self-evident:

That the real world is the source of our own lives, and the lives of others. A weakened planet is less capable of supporting life, human or otherwise. Thus the health of the real world is primary, more important than any social or economic system, because all social or economic systems are dependent upon a living planet: without a living planet you don’t have any social or economic systems whatsoever. It is self-evident that to value a social system that harms the planet’s capacity to support life over life itself is literally insane, in terms of being out of touch with physical reality.

That any way of life based on the use of nonrenewable resources is by definition not sustainable.

That any way of life based on the hyperexploitation of renewable resources is by definition not sustainable: if, for example, there are fewer salmon return every year, eventually there will be none. This means that for a way of life to be sustainable, it must not harm native communities: native prairies, native forests, native fisheries, and so on.

That the real world is interdependent, such that harm done to rivers harms those humans and nonhumans whose lives depend on these rivers, harms forests and prairies and wetlands surrounding these rivers, harms the oceans into which these rivers flow. Harm done to mountains harms rivers flowing through them. Harm done to oceans harms everyone directly or indirectly connected to them.

That you cannot argue with physics. If you burn carbon-based fuels, this carbon will go into the air, and have effects in the real world.

That creating and releasing poisons into the world will poison humans and nonhumans.

That no one, no matter now rich or powerful, should be allowed to create poisons for which there is no antidote.

That no one, no matter how rich or powerful, should be allowed to create messes that cannot be cleaned up.

That no one, no matter how rich or powerful, should be allowed to destroy places humans or nonhumans need to survive.

That no one, no matter how rich or powerful, should be allowed to drive human cultures or nonhuman species extinct.

That reality trumps all belief systems: what you believe is not nearly so important as what is real.

That on a finite planet you cannot have an economy based on or requiring growth. At least you cannot have one and expect to either have a planet or a future.

That the current way of life is not sustainable, and will collapse. The only real questions are what will be left of the world after that collapse, and how bad things will be for the humans and nonhumans who come after. We hold it as self-evident that we should do all that we can to make sure that as much of the real, physical world remains intact until the collapse of the current system, and that humans and nonhumans should be as prepared as possible for this collapse.

That the health of local economies are more important than the health of a global economy.

That a global economy should not be allowed to harm local economies or landbases.

That corporations are not living beings. They are certainly not human beings.

That corporations do not in any real sense exist. They are legal fictions. Limited liability corporations are institutions created explicitly to separate humans from the effects of their actions—making them, by definition, inhuman and inhumane. To the degree that we desire to live in a human and humane world—and, really, to the degree that we wish to survive—limited liability corporations need to be eliminated.

That the health of human and nonhuman communities are more important than the profits of corporations.

We hold it as self-evident, as the Declaration of Independence states, “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends [Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness], it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it. . . .” Further, we hold it as self-evident that it would be more precise to say that it is not the Right of the People, nor even their responsibility, but instead something more like breathing—something that if we fail to do we die. If we as a People fail to rid our communities of destructive institutions, those institutions will destroy our communities. And if we in our communities cannot provide meaningful and nondestructive ways for people to gain food, clothing, and shelter then we must recognize it’s not just specific destructive institutions but the entire economic system that is pushing the natural world past breaking points. Capitalism is killing the planet. Industrial civilization is killing the planet. Once we’ve recognized the destructiveness of capitalism and industrial civilization—both of which are based on systematically converting a living planet into dead commodities—we’ve no choice, unless we wish to sign our own and our children’s death warrants, but to fight for all we’re worth and in every way we can to overturn it.

#

Here is a list of our initial demands. When these demands are met, we will have more, and then more, until we are living sustainably in a just society. In each case, if these demands are not met, we will, because we do not wish to sign our own and our children’s death warrants, put them in place ourselves.

We demand that:

- Communities, including nonhuman communities, be immediately granted full legal and moral rights.

- Corporations be immediately stripped of their personhood, no longer be considered as persons under the law.

- Limited liability corporations be immediately stripped of their limited liability protection. If someone wants to perpetrate some action for which there is great risk to others, this person should be prepared to assume this risk him- or herself.

- Those whose economic activities cause great harm—including great harm to the real, physical world—be punished commensurate with their harm. So long as prisons and the death penalty exist, Tony Hayward of BP and Don Blankenship of Massey Coal, to provide two examples among many, should face the death penalty or life in prison without parole for murder, both of human beings and of landbases. The same can be said for many others, including those associated with these specific murders and thefts, and including those associated with many other murders and thefts.

- Environmental Crimes Tribunals be immediately put in place to try those who have significantly harmed the real, physical world. These tribunals will have force of law and will impose punishment commensurate with the harm caused to the public and to the real world.

- The United States immediately withdraw from NAFTA, DR-CAFTA, and other so-called “free trade agreements” (if it really is “free trade,” then why do they need the military and police to enforce it?) as these cause immeasurable and irreparable harm to local economies in the United States and abroad, and to the real, physical world. They cause grievous harm to working people in the United States and elsewhere. Committees should be formed to determine whether to try those who signed on to NAFTA for subverting United States sovereignty, and for Crimes Against Humanity for the deaths caused by these so-called free trade agreements.

- The United States remove all support for the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Both of these organizations cause immeasurable and irreparable harm to local economies in the United States and abroad, and to the real, physical world. They cause grievous harm to working people in the United States and elsewhere.

- The United States recognize that it is founded on land stolen from indigenous peoples. We demand a four stage process to rectify this ongoing atrocity. The first stage consists of immediately overturning the relevant parts of the 1823 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Johnson v. M’Intosh, which includes such rationalizations for murder and theft as, “However extravagant the pretension of converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest may appear; if the principle has been asserted in the first instance, and afterwards sustained; if a country has been acquired and held under it; if the property of the great mass of the community originates in it, it becomes the law of the land, and cannot be questioned.” We demand that this pretense, this principle, not only be questioned but rejected. The second is that all lands for which the United States government cannot establish legal title through treaty must immediately be returned to those peoples from whom it was stolen. Large scale landowners, those with over 640 acres, must immediately return all lands over 640 acres to their original and rightful inhabitants. Small scale landowners, those with title to 640 acres or less, who are “innocent purchasers” may retain title to their land (and this same is true for the primary 640 acres of larger landowners), but may not convey this title to others, and on their deaths it passes back to the original and rightful inhabitants. The third phase is for the United States government to pay reparations to those whose land they have taken commensurate with the harm they have caused. The fourth phase is for each and every treaty between the United States government and sovereign indigenous nations to be revisited, with an eye toward determining whether the treaties were signed under physical, emotional, economic, or military duress and whether these treaties have been violated. In either of these cases the wrongs must be redressed, once again commensurate with the harm these wrongs have caused.

- The United States government will provide reparations to those whose families have been harmed by chattel slavery, commensurate with the harm caused.

- Rivers be restored. There are more than 2 million dams in the United States, more than 60,000 dams over thirteen feet tall and over 70,000 dams over six and a half feet tall. Dams kill rivers. If we removed one of these 70,000 dams each day, it would take 200 years to get rid of them all. Salmon don’t have that time. Sturgeon don’t have that time. We demand that no more dams be built, and we demand the removal of five of those 70,000 dams per day over the next forty years, beginning one year from today. Remember, physical reality is more important than your belief system.

- Native prairies, wetlands, and forests be restored, at a rate of five percent per year. Please note that tree farms or “forests” managed for timber are not the same as native forests, any more than lawns or corn fields are prairies, and any more than concrete sluices are wetlands. Please note also that if all of the prairies and forests east of the Mississippi River were restored, the United States could be a net carbon sink within five years, even without reducing carbon emissions.

- An immediate end to clearcutting, “leave tree,” “seed tree,” “shelter tree” and all other “even age management” techniques, no matter what they are called, and no matter what rationales are put forward by the timber industry and the government. All remaining native forests are immediately and completely protected.

- An immediate end to destruction of prairies and wetlands. All remaining prairies and wetlands are immediately protected.

- The United States government immediately begin strict enforcement of the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, and other acts aimed at protecting the real, physical world. All programs associated with these Acts must be fully funded. This includes the immediate designation of Critical Habitat for all species on the wait list.

- Each year the United States must survey all endangered species to ascertain if they are increasing in number and range. If not, the United States government will do what is required to make sure they do.

- The United States government do whatever is necessary to make sure that there are fewer toxins in every mother’s breast milk every year than the year before, and that there are fewer carcinogens in every stream every year than the year before.

- The United States government do whatever is necessary to make sure that there are more migratory songbirds every year than the year before, that there are more native fish every year than the year before, more native reptiles and amphibians, and so on.

- Immediate closure of all US military bases on foreign soil. All US military personnel are to be immediately brought home.

- An immediate ban on the direct or indirect use of mercenaries (“military contractors”) by the US government and all associated entities.

- A reduction in the US military budget by 20 per year, until it reaches 20 percent of its current size. Then it will be maintained at no larger than that except in case of a war that is declared only by a direct vote of more than 50 percent of US citizens (and to last only as long as 50 percent of US citizens back it). This will provide the “peace dividend” politicians lyingly promised us back when the Soviet Union collapsed, and will balance the US budget and more than pay for all necessary domestic programs.

- The United States officially recognize that capitalism is based on subsidies, or as Dwayne Andreas, former CEO of ADM said, “There isn’t one grain of anything in the world that is sold in a free market. Not one! The only place you see a free market is in the speeches of politicians.” He’s right. For example, commercial fishing fleets worldwide receive more in subsidies than the entire value of their catch. Timber corporations, oil corporations, banks, would all collapse immediately without massive government subsidies and bailouts. Therefore, we demand that the United States government stop subsidizing environmentally and socially destructive activities, and shift those same subsidies into activities that restore the real, physical, world and that promote local self-sufficiency and vibrant local economies. Instead of subsidizing deforestation, subsidize reforestation. Instead of subsidizing the oil industry, subsidize relocalization. Instead of subsidizing fisheries depletion, subsidize fisheries restoration. Instead of subsidizing plastics production, subsidize cleaning plastics from the ocean. Instead of subsidizing the production of toxics by the chemical industries, subsidize the cleaning up of these toxics, both from our bodies and from the rest of the real, physical world.

- Scientific consensus is that to prevent even more catastrophic climate change than we and the rest of the world already face, net carbon emissions must be reduced by 80 percent. Because we wish to continue to live on a habitable planet, we demand a carbon reduction of 20 percent of current emissions per year over the next four years.

- The enshrinement in law of the right for workers to collectively bargain. In case of strikes, if police are brought in at all, it must be to protect the right of workers to strike. If police force anyone to come to terms, they must force the capitalists.

- That laws against rape be enforced, even against those who are rich, even those who are famous athletes, even those who are politicians, even those who are entertainers.

- The enshrinement in law of the precautionary principle, which states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm to the public or the real, physical world, then the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those taking the action. In the absence of conclusive proof, no action may be taken. For example, no chemicals would be allowed to be released into the environment without conclusive proof that they will not harm the public or the environment.

- No new chemicals be released into the real, physical world until all currently used chemicals have been thoroughly tested for toxicity, and if found to have any significant chance of harming the public or the environment, these chemicals must be immediately and without exception withdrawn from use.

- The immediate, explicit, and legally binding recognition that perpetual growth is incompatible with life on a finite planet. We demand that economic growth stop, and that economies begin to contract. We demand immediate acknowledgement that if we do not begin this contraction voluntarily, that this contraction will take place against our will, and will cause untold misery.

- That overconsumption and overpopulation must be addressed in methods that are not racist, colonialist, or misogynist. We must recognize that humans, and especially industrial humans, have overshot the planet’s carrying capacity. We must recognize further that while overconsumption is more harmful than overpopulation, both are harmful. We must further recognize that right now, more than fifty percent of the children who are born are not wanted. We demand that all children be wanted. We recognize that the single most effective strategy for making certain that all children are wanted is the liberation of women. Therefore we demand that women be given absolute reproductive freedom, and that all forms of reproductive control be freely available to women. We demand that those who attempt to deny women this freedom be punished by law.

- The United States government put an immediate end to absentee land ownership. No one shall be allowed to own land more than one-quarter of a mile from his or her home.

- Land ownership patterns change. Land ownership is more concentrated in the United States than in many countries the United States derides as antidemocratic: five percent of farmers in Honduras own 67 percent of the arable land, while in the United States five percent of landowners (not citizens) own 75 percent of the land (California is in many ways worse: twenty-five landowners own 58 percent of the farmland). To rectify this, no one shall be allowed to own more than 640 acres. All title to individual or corporate land holdings over 640 acres are to be immediately forfeited. These lands will be first in line for restoration to native forest, prairie, wetland, and so on. Lands not suitable for these purposes will be used to provide housing for those who cannot afford it.

- An immediate end to factory farming and to monocrop agriculture, two of the most destructive activities humans have ever perpetrated. We demand a return to perennial polycultures.

- An immediate end to soil drawdown. Because soil is the basis of terrestrial life, no activities will be allowed which destroy topsoil. All properties over sixty acres must have soil surveys every ten years (on every sixty acre parcel), and if they have suffered any decrease of health or depth of topsoil the lands will be confiscated and given to those who will build up soil.

- An immediate end to aquifer drawdown. No activities will be allowed which draw down aquifers.

- Provision of free food, shelter, and medical necessities to all residents.

- Immediate increase in the tax rate to 95 percent for all gross earnings over one million dollars per year by persons or entities.

- An immediate and permanent halt to all fracking, mountaintop removal, tar sands extraction, nuclear power, and offshore drilling.

- An immediate and permanent halt to all energy production that is harmful to the real, physical world. This includes the manufacture of solar photovoltaics, windmills, hybrid cars, and so on.

- Removal of plastic from the ocean. Each year the ocean must have 5 percent less plastic in it than the year before.

- Each year the oceans must have 5 percent more large fish than the year before.

- The United States Constitution be rewritten to destroy the primacy it gives to the privatization of profits and the externalization of costs by the wealthy, and to make its primary purpose not the preservation of the wealth and power of the already wealthy and powerful, but rather to protect human and nonhuman communities—to protect the real, physical world—and enforcably to deprive the rich of their ability to steal from the poor and the powerful of their ability to destroy the planet.

#

We hold these further truths also to be self-evident:

That demands without means to enforce them are nothing more than begging. We are not begging. We are demanding.

Power is not a mistake, and those in power will not suddenly have attacks of conscience. Social change has never occurred through waiting for the rich or powerful to develop consciences, and it never will.

Those in power will not act different than they have acted all along, and they will not act against the power of capital. We hold it as self-evident that the rich and powerful have no reason to stop the rich from stealing from the poor nor the powerful from destroying more of the real, physical world than they already have. That is, they have no reason except us. Our lives and the life of the planet that is our only home is on the line. We no longer have the luxury of allowing those in power to continue. If those in power won’t accede to these demands, then they need to not be in power, and we need to remove them from power, using any means necessary.

We hold it as self-evident, as the Declaration of Independence states, “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends [Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness], it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it. . . .”

It is long past time we asserted our rights.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

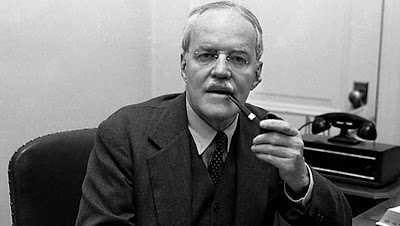

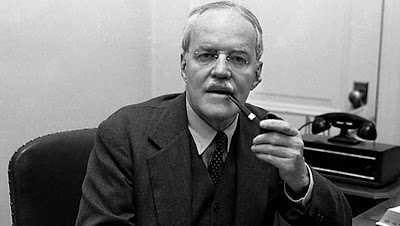

American diplomat and lawyer Allen Dulles (1893-1969), the 5th Director of Central Intelligence and once head of the CIA listed 73 Rules of Spycraft.

“The greatest weapon a man or woman can bring to this type of work in which we are engaged is his or her hard common sense. The following notes aim at being a little common sense and applied form. Simple common sense crystallized by a certain amount of experience into a number of rules and suggestions.

- There are many virtues to be striven after in the job. The greatest of them all is security. All else must be subordinated to that.

- Security consists not only in avoiding big risks. It consists in carrying out daily tasks with painstaking remembrance of the tiny things that security demands. The little things are in many ways more important than the big ones. It is they which oftenest give the game away. It is consistent care in them, which form the habit and characteristic of security mindedness.

- In any case, the man or woman who does not indulge in the daily security routine, boring and useless though it may sometimes appear, will be found lacking in the proper instinctive reaction when dealing with the bigger stuff.

- No matter how brilliantly given an individual, no matter how great his goodwill, if he is lacking in security, he will eventually prove more of a liability than asset.

- Even though you feel the curious outsider has probably a good idea that you are not what you purport to be, never admit it. Keep on playing the other part. It’s amazing how often people will be led to think they were mistaken. Or at least that you are out ‘in the other stuff’ only in a very mild way. And anyhow, a person is quite free to think what he likes. The important thing is that neither by admission or implication do you let him know.

- Security, of course, does not mean stagnation or being afraid to go after things. It means going after things, but reducing all the risks to a minimum by hard work.

- Do not overwork your cover to the detriment of your jobs; we must never get so engrossed in the latter as to forget the former.

- Never leave things lying about unattended or lay them down where you are liable to forget them. Learn to write lightly; the “blank” page underneath has often been read. Be wary of your piece of blotting paper. If you have to destroy a document, do so thoroughly. Carry as little written matter as possible, and for the shortest possible time. Never carry names or addresses en clair. If you cannot carry them for the time being in your head, put them in a species of personal code, which only you understand. Small papers and envelopes or cards and photographs, ought to be clipped on to the latter, otherwise they are liable to get lost. But when you have conducted an interview or made arrangements for a meeting, write it all down and put it safely away for reference. Your memory can play tricks.

- The greatest vice in the game is that of carelessness. Mistakes made generally cannot be rectified.

- The next greatest vice is that of vanity. Its offshoots are multiple and malignant. Besides, the man with a swelled head never learns. And there is always a great deal to be learned.

- Booze is naturally dangerous. So also is an undisciplined attraction for the other sex. The first loosens the tongue. The second does likewise. It also distorts vision and promotes indolence. They both provide grand weapons to an enemy.

- It has been proved time and again, in particular, that sex and business do not mix.

- In this job, there are no hours. That is to say, one never leaves it down. It is lived. One never drops one’s guard. All locations are good for laying a false trail (social occasions, for instance, a casual hint here, a phrase there). All locations are good for picking something up, or collecting…for making a useful acquaintance.

- In a more normal sense of the term “no hours,” it is certainly not a business where people put their own private arrangements before their work.

- That is not to say that one does not take recreation and holidays. Without them it is not possible to do a decent job. If there is a real goodwill and enthusiasm for the work, the two (except in abnormal circumstances) will always be combined without the work having to suffer.

- The greatest material curse to the profession, despite all its advantages, is undoubtedly the telephone. It is a constant source of temptation to slackness. And even if you do not use it carelessly yourself, the other fellow, very often will, so in any case, warn him. Always act on the principle that every conversation is listened to, that a call may always give the enemy a line. Naturally, always unplug during confidential conversations. Even better is it to have no phone in your room, or else have it in a box or cupboard.

- Sometimes, for quite exceptional reasons, it may be permissible to use open post as a channel of communications. Without these quite exceptional reasons, allowing of no alternative, it is to be completely avoided.

- When the post is used, it will be advisable to get through post boxes; that is to say, people who will receive mail for you and pass it on. This ought to be their only function. They should not be part of the show. They will have to be chosen for the personal friendship which they have with you or with one of your agents. The explanation you give them will depend on circumstances; the letters, of course, must be apparently innocent incontinence. A phrase, signature or embodied code will give the message. The letter ought to be concocted in such fashion as to fit in with the recipient’s social background. The writer ought therefore to be given details of the post boxes assigned to them. An insipid letter is in itself suspicious. If however, a signature or phrase is sufficient to convey the message, then a card with greetings will do.

- Make a day’s journey, rather than take a risk, either by phone or post. If you do not have a prearranged message to give by phone, never dial your number before having thought about your conversation. Do not improvise even the dummy part of it. But do not be too elaborate. The great rule here, as in all else connected with the job, is to be natural.

- If you have phoned a line or a prospective line of yours from a public box and have to look up the number, do not leave the book lying open on that page.

- When you choose a safe house to use for meetings or as a depot, let it be safe. If you can, avoid one that is overlooked by other houses. If it is, the main entrance should be that used for other houses as well. Make sure there are no suspicious servants. Especially, of course, be sure of the occupants. Again, these should be chosen for reasons of personal friendship with some member of the organization and should be discreet. The story told to them will once again depend on circumstances. They should have no other place in the show, or if this is unavoidable, then calls at the house should be made as far as possible after dark.

- Always be yourself. Always be natural inside the setting you have cast for yourself. This is especially important when meeting people for the first time or when traveling on a job or when in restaurants or public places in the course of one. In trains or restaurants people have ample time to study those nearest them. The calm quiet person attracts little attention. Never strain after an effect. You would not do so in ordinary life. Look upon your job as perfectly normal and natural.

- When involved in business, look at other people as little as possible, and don’t dawdle. You will then have a good chance of passing unnoticed. Looks draw looks.

- Do not dress in a fashion calculated to strike the eye or to single you out easily.

- Do not stand around. And as well as being punctual yourself, see that those with whom you are dealing are punctual. Especially if the meeting is in a public place; a man waiting around will draw attention. But even if it is not in a public place, try to arrive and make others arrive on the dot. An arrival before the time causes as much inconvenience as one after time.

- If you have a rendezvous, first make sure you are not followed. Tell the other person to do likewise. But do not act in any exaggerated fashion. Do not take a taxi to a house address connected with your work. If it cannot be avoided, make sure you are not under observation when you get into it. Or give another address, such as that of a café or restaurant nearby.

- Try to avoid journeys to places where you will be noticeable. If you have to make such journeys, repeat them as little as possible, and take all means to make yourself fit in quietly with the background.

- Make as many of your difficult appointments as you can after dark. Turn the blackout to good use. If you cannot make it after dark, make it very early morning when people are only half awake and not on the lookout for strange goings-on.

- Avoid restaurants, cafes and bars for meetings and conversations. Above all never make an initial contact in one of them. Let it be outside. Use abundance of detail and description of persons to be met, and have one or two good distinguishing marks. Have a password that can be given to the wrong person without unduly exciting infestation.

- If interviews cannot be conducted in a safe house, then take a walk together in the country. Cemeteries, museums and churches are useful places to bear in mind.

- Use your own judgment as to whether or not you ought to talk to chance travel or table companions. It may be useful. It may be the opposite. It may be of no consequence whatsoever. Think, however, before you enter upon a real conversation, whether this particular enlargement of the number of those who will recognize and spot you in the future is liable or not to be a disadvantage. Always carry reading matter. Not only will it save you from being bored, it is protective armor if you want to avoid a conversation or to break off an embarrassing one.

- Always be polite to people, but not exaggeratedly so. With the following class of persons who come to know you — hotel and restaurant staffs, taxi drivers, train personnel etc., be pleasant.

- Someday, they may prove useful to you. Be generous in your tips to them, but again, not exaggeratedly so. Give just a little more than the other fellow does – unless the cover under which you are working does not permit this. Give only normal tips. however, to waiters and taxi drivers, etc., when you are on the job. Don’t give them any stimulus, even of gratification, to make you stick in their minds. Be as brief and casual as possible.

- Easiness and confidence do not come readily to all of us. They must be assiduously cultivated. Not only because they help us personally, but they also help to produce similar reactions in those we are handling.

- Never deal out the intense, the dramatic stuff, to a person before you have quietly obtained his confidence in your levelheadedness.

- If you’re angling for a man, lead him around to where you want him; put the obvious idea in his head, and make the suggestion of possibilities come to him. Express, if necessary – but with great tact — a wistful disbelief in the possibilities at which you are aiming. “How fine it would be if only someone could… but of course, etc. etc.” And always leave a line of retreat open to yourself.

- Never take a person for granted. Very seldom judge a person to be above suspicion. Remember that we live by deceiving others. Others live by deceiving us. Unless others take persons for granted or believe in them, we would never get our results. The others have people as clever as we; if they can be taken in, so can we. Therefore, be suspicious.

- Above all, don’t deceive yourself. Don’t decide that the other person is fit or is all right, because you yourself would like it to be that way. You are dealing in people’s lives.

- When you have made a contact, till you are absolutely sure of your man — and perhaps even then — be a small but eager intermediary. Have a “They” in the background for whom you act and to whom you are responsible. If “They” are harsh, if “They” decide to break it off, it is never any fault of yours, and indeed you can pretend to have a personal grievance about it. “They” are always great gluttons for results and very stingy with cash until “They” get them. When the results come along, “They” always send messages of congratulation and encouragement.

- Try to find agents who do not work for money alone, but for conviction. Remember, however, that not by conviction alone, does the man live. If they need financial help, give it to them. And avoid the “woolly” type of idealist, the fellow who lives in the clouds.

- Become a real friend of your agents. Remember that he has a human side so bind him to you by taking an interest in his personal affairs and in his family. But never let the friendship be stronger than your sense of duty to the work. That must always be impervious to any sentimental considerations. Otherwise, your vision will be distorted, your judgment affected, and you may be reluctant, even, to place your men in a position of danger. You may also, by indulgence toward him, let him endanger others.

- Gain the confidence of your agents, but be wary of giving them more of yours than is necessary. He may fall by the way side; he may quarrel with you; it may be advisable for a number of reasons to drop him. In that case, obviously, the less information he possesses, the better. Equally obviously, if an agent runs the risk of falling into the hands of the enemy, it is unfair both to him and the show to put him in possession of more knowledge than he needs.

- If your agent can be laid off work periodically, this is a very good thing. And during his rest periods, let him show himself in another field and in other capacities.

- Teach them at least the elements of technique. Do not merely leave it to his own good judgment, and then hope for the best. Insist, for a long time at least, on his not showing too much initiative, but make him carry out strictly the instructions which you give him. His initiative will he tested when unexpected circumstances arise. Tell him off soundly when he errs; praise him when he does well.

- Do not be afraid to be harsh, or even harsh with others, if it is your duty to be so. You are expected to be likewise with yourself. When necessity arises neither your own feelings not those of others matter. Only the job — the lives and safety of those entrusted to you — is what counts.

- Remember that you have no right to expect of others what you are not prepared to do yourself. But on the other hand, do not rashly expose yourself in any unnecessary displays of personal courage that may endanger the whole shooting match. It often takes more moral courage to ask another fellow to do a dangerous task than to do it yourself. But if this is the proper course to follow, then you must follow it.

- If you have an agent who is really very important to you, who is almost essential to your organization, try not to let them know this. Infer, without belittling him, that there are other lines and other groups of a bigger nature inside the shadow, and that — while he and his particular group are doing fine work — they are but part of a mosaic.

- Never let your agent get the bit between his teeth and run away with you. If you cannot manage it easily yourself, there are always the terrible “They.”

- But if your agent knows the ground on which he is working better than you, always be ready to listen to his advice and to consult him. The man on the spot is the man who can judge.

- In the same way, if you get directives from HQ, which to you seem ill-advised, do not be afraid to oppose these directives. You are there for pointing things out. This is particularly so if there is grave danger to security without a real corresponding advantage for which the risk may be taken. For that, fight anybody with everything you’ve got.

- If you have several groups, keep them separate unless the moment comes for concerted action. Keep your lines separate; and within the bounds of reason and security, try to multiply them. Each separation and each multiplication minimizes the danger of total loss. Multiplication of lines also gives the possibility of resting each line, which is often a very desirable thing.

- Never set a thing really going, whether it be big or small, before you see it in its details. Do not count on luck. Or only on bad luck.

- When using couriers, who are in themselves trustworthy — (here again, the important element of personal friendship ought to be made to play its part) — but whom it is better to keep in the dark as to the real nature of what they are carrying, commercial smuggling will often provide an excellent cover. Apart from being a valid reason for secrecy, it gives people a kick and also provides one with a reason for offering payment. Furthermore, it involves a courier in something in which it is in his own personal advantage to conceal.

- To build this cover, should there be no bulk of material to pass, but only a document or a letter, it will be well always to enclose this properly sealed in a field dummy parcel with an unsealed outer wrapping.

- The ingredients for any new setup are: serious consideration of the field and of the elements at your disposal; the finding of one key man or more; safe surroundings for encounter; safe houses to meet in; post boxes; couriers; the finding of natural covers and pretext for journeys, etc.; the division of labor; separation into cells; the principal danger in constructing personal friendships between the elements (this is enormously important); avoidance of repetition.

- The thing to aim at, unless it is a question of a special job, is not quick results, which may blow up the show, but the initiation of a series of results, which will keep on growing and which, because the show has the proper protective mechanism to keep it under cover, will lead to discovery.

- Serious groundwork is much more important than rapid action. The organization does not merely consist of the people actively working but the potential agents whom you have placed where they may be needed, and upon whom you may call, if need arises.

- As with an organization, so with a particular individual. His first job in a new field is to forget about everything excepting his groundwork; that is, the effecting of his cover. Once people label him, the job is half done. People take things so much for granted and only with difficulty change their sizing-up of a man once they have made it. They have to be jolted out of it. It is up to you to see that they are not. If they do suspect, do not take it that all is lost and accept the position. Go back to your cover and build it up again. You will at first puzzle them and finally persuade them.

- The cover you choose will depend upon the type of work that you have to do. So also will the social life in which you indulge. It may be necessary to lead a full social existence; it may be advisable to stay in the background. You must school yourself not to do any wishful thinking in the sense of persuading yourself that what you want to do is what you ought to do.

- Your cover and social behavior, naturally, ought to be chosen to fit in with your background and character. Neither should be too much of a strain. Use them well. Imprint them, gradually but steadfastly on people’s minds. When your name crops up in conversation they must have something to say about you, something concrete outside of your real work.

- The place you live in is often a thorny problem. Hotels are seldom satisfactory. A flat of your own where you have everything under control is desirable; if you can share it with a discreet friend who is not in the business, so much the better. You can relax into a normal life when you get home, and he will also give you an opportunity of cover. Obviously the greatest care is to be taken in the choice of servants. But it is preferable to have a reliable servant than to have none at all. People cannot get in to search or fix telephones, etc. in your absence. And if you want to not be at home for awkward callers (either personal or telephonic), servants make that possible.

- If a man is married, the presence of his wife may be an advantage or disadvantage. That will depend on the nature of the job — as well as on the nature of the husband and wife.

- Should a husband tell his wife what he is doing? It is taken for granted that people in this line are possessed of discretion and judgment. If a man thinks his wife is to be trusted, then he may certainly tell her what he is doing — without necessarily telling her the confidential details of particular jobs. It would be fair to neither husband nor wife to keep her in the dark unless there were serious reasons demanding this. A wife would naturally have to be coached in behavior in the same way as an agent.

- Away from the job, among your other contacts, never know too much. Often you will have to bite down on your vanity, which would like to show what you know. This is especially hard when you hear a wrong assertion being made or a misstatement of events.

- Not knowing too much does not mean not knowing anything. Unless there is a special reason for it, it is not good either to appear a nitwit or a person lacking in discretion. This does not invite the placing of confidence in you.

- Show your intelligence, but be quiet on anything along the line you are working. Make others do the speaking. A good thing sometimes is to be personally interested as “a good patriot and anxious to pass along anything useful to official channels in the hope that it may eventually get to the right quarter.”

- When you think a man is possessed of useful knowledge or may in other ways be of value to you, remember that praise is acceptable to the vast majority of men. When honest praise is difficult, a spot of flattery will do equally well.

- Within the limits of your principles, be all things to all men. But don’t betray your principles. The strongest force in your show is you. Your sense of right, your sense of respect for yourself and others. And it is your job to bend circumstances to your will, not to let circumstances bend or twist you.

- In your work, always be in harmony with your own conscience. Put yourself periodically in the dock for cross examination. You can never do more than your best; only your best is good enough. And remember that only the job counts — not you personally, excepting satisfaction of a job well done.

- It is one of the finest jobs going. no matter how small the part you play may appear to be. Countless people would give anything to be in it. Remember that and appreciate the privilege. No matter what others may do, play your part well.

- Never get into a rut. Or rest on your oars. There are always new lines around the corner, always changes and variations to be introduced. Unchanging habits of work lead to carelessness and detection.

- If anything, overestimate the opposition. Certainly never underestimate it. But do not let that lead to nervousness or lack of confidence. Don’t get rattled, and know that with hard work, calmness, and by never irrevocably compromising yourself, you can always, always best them.

- Lastly, and above all — REMEMBER SECURITY.

PS. The above points are not intended for any cursory, even interested, glance. They will bear — each of them — serious attention, and at least occasional re-perusal. It is probable, furthermore, that dotted here and there among them will be found claims that have particular present application for each person who reads them. These, naturally, are meant to be acted upon straightaway.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 1, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part, you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop!

—Mario Savio, Berkeley Free Speech Movement

To gain what is worth having, it may be necessary to lose everything else.

—Bernadette Devlin, Irish activist and politician

BRINGING IT DOWN: COLLAPSE SCENARIOS

At this point in history, there are no good short-term outcomes for global human society. Some are better and some are worse, and in the long term some are very good, but in the short term we’re in a bind. I’m not going to lie to you—the hour is too late for cheermongering. The only way to find the best outcome is to confront our dire situation head on, and not to be diverted by false hopes.

Human society—because of civilization, specifically—has painted itself into a corner. As a species we’re dependent on the draw down of finite supplies of oil, soil, and water. Industrial agriculture (and annual grain agriculture before that) has put us into a vicious pattern of population growth and overshoot. We long ago exceeded carrying capacity, and the workings of civilization are destroying that carrying capacity by the second. This is largely the fault of those in power, the wealthiest, the states and corporations. But the consequences—and the responsibility for dealing with it—fall to the rest of us, including nonhumans.

Physically, it’s not too late for a crash program to limit births to reduce the population, cut fossil fuel consumption to nil, replace agricultural monocrops with perennial polycultures, end overfishing, and cease industrial encroachment on (or destruction of) remaining wild areas. There’s no physical reason we couldn’t start all of these things tomorrow, stop global warming in its tracks, reverse overshoot, reverse erosion, reverse aquifer drawdown, and bring back all the species and biomes currently on the brink. There’s no physical reason we couldn’t get together and act like adults and fix these problems, in the sense that it isn’t against the laws of physics.

But socially and politically, we know this is a pipe dream. There are material systems of power that make this impossible as long as those systems are still intact. Those in power get too much money and privilege from destroying the planet. We aren’t going to save the planet—or our own future as a species—without a fight.

What’s realistic? What options are actually available to us, and what are the consequences? What follows are three broad and illustrative scenarios: one in which there is no substantive or decisive resistance, one in which there is limited resistance and a relatively prolonged collapse, and one in which all-out resistance leads to the immediate collapse of civilization and global industrial infrastructure.

NO RESISTANCE

If there is no substantive resistance, likely there will be a few more years of business as usual, though with increasing economic disruption and upset. According to the best available data, the impacts of peak oil start to hit somewhere between 2011 and 2015, resulting in a rapid decline in global energy availability.1 It’s possible that this may happen slightly later if all-out attempts are made to extract remaining fossil fuels, but that would only prolong the inevitable, worsen global warming, and make the eventual decline that much steeper and more severe. Once peak oil sets in, the increasing cost and decreasing supply of energy undermines manufacturing and transportation, especially on a global scale.

The energy slide will cause economic turmoil, and a self-perpetuating cycle of economic contraction will take place. Businesses will be unable to pay their workers, workers will be unable to buy things, and more companies will shrink or go out of business (and will be unable to pay their workers). Unable to pay their debts and mortgages, homeowners, companies, and even states will go bankrupt. (It’s possible that this process has already begun.) International trade will nosedive because of a global depression and increasing transportation and manufacturing costs. Though it’s likely that the price of oil will increase over time, there will be times when the contracting economy causes falling demand for oil, thus suppressing the price. The lower cost of oil may, ironically but beneficially, limit investment in new oil infrastructure.

At first the collapse will resemble a traditional recession or depression, with the poor being hit especially hard by the increasing costs of basic goods, particularly of electricity and heating in cold areas. After a few years, the financial limits will become physical ones; large-scale energy-intensive manufacturing will become not only uneconomical, but impossible.

A direct result of this will be the collapse of industrial agriculture. Dependent on vast amounts of energy for tractor fuel, synthesized pesticides and fertilizers, irrigation, greenhouse heating, packaging, and transportation, global industrial agriculture will run up against hard limits to production (driven at first by intense competition for energy from other sectors). This will be worsened by the depletion of groundwater and aquifers, a long history of soil erosion, and the early stages of climate change. At first this will cause a food and economic crisis mostly felt by the poor. Over time, the situation will worsen and industrial food production will fall below that required to sustain the population.

There will be three main responses to this global food shortage. In some areas people will return to growing their own food and build sustainable local food initiatives. This will be a positive sign, but public involvement will be belated and inadequate, as most people still won’t have caught on to the permanency of collapse and won’t want to have to grow their own food. It will also be made far more difficult by the massive urbanization that has occurred in the last century, by the destruction of the land, and by climate change. Furthermore, most subsistence cultures will have been destroyed or uprooted from their land—land inequalities will hamper people from growing their own food (just as they do now in the majority of the world). Without well-organized resisters, land reform will not happen, and displaced people will not be able to access land. As a result, widespread hunger and starvation (worsening to famine in bad agricultural years) will become endemic in many parts of the world. The lack of energy for industrial agriculture will cause a resurgence in the institutions of slavery and serfdom.

Slavery does not occur in a political vacuum. Threatened by economic and energy collapse, some governments will fall entirely, turning into failed states. With no one to stop them, warlords will set up shop in the rubble. Others, desperate to maintain power against emboldened secessionists and civil unrest, will turn to authoritarian forms of government. In a world of diminishing but critical resources, governments will get leaner and meaner. We will see a resurgence of authoritarianism in modern forms: technofascism and corporation feudalism. The rich will increasingly move to private and well-defended enclaves. Their country estates will not look apocalyptic—they will look like eco-Edens, with well-tended organic gardens, clean private lakes, and wildlife refuges. In some cases these enclaves will be tiny, and in others they could fill entire countries.

Meanwhile, the poor will see their own condition worsen. The millions of refugees created by economic and energy collapse will be on the move, but no one will want them. In some brittle areas the influx of refugees will overwhelm basic services and cause a local collapse, resulting in cascading waves of refugees radiating from collapse and disaster epicenters. In some areas refugees will be turned back by force of arms. In other areas, racism and discrimination will come to the fore as an excuse for authoritarians to put marginalized people and dissidents in “special settlements,” leaving more resources for the privileged.2 Desperate people will be the only candidates for the dangerous and dirty manual labor required to keep industrial manufacturing going once the energy supply dwindles. Hence, those in power will consider autonomous and self-sustaining communities a threat to their labor supply, and suppress or destroy them.

Despite all of this, technological “progress” will not yet stop. For a time it will continue in fits and starts, although humanity will be split into increasingly divergent groups. Those on the bottom will be unable to meet their basic subsistence needs, while those on the top will attempt to live lives of privilege as they had in the past, even seeing some technological advancements, many of which will be intended to cement the superiority of those in power in an increasingly crowded and hostile world.

Technofascists will develop and perfect social control technologies (already currently in their early stages): autonomous drones for surveillance and assassination; microwave crowd-control devices; MRI-assisted brain scans that will allow for infallible lie detection, even mind reading and torture. There will be no substantive organized resistance in this scenario, but in each year that passes the technofascists will make themselves more and more able to destroy resistance even in its smallest expression. As time slips by, the window of opportunity for resistance will swiftly close. Technofascists of the early to mid-twenty-first century will have technology for coercion and surveillance that will make the most practiced of the Stasi or the SS look like rank amateurs. Their ability to debase humanity will make their predecessors appear saintly by comparison.

Not all governments will take this turn, of course. But the authoritarian governments—those that will continue ruthlessly exploiting people and resources regardless of the consequences—will have more sway and more muscle, and will take resources from their neighbors and failed states as they please. There will be no one to stop them. It won’t matter if you are the most sustainable eco-village on the planet if you live next door to an eternally resource-hungry fascist state.

Meanwhile, with industrial powers increasingly desperate for energy, the tenuous remaining environmental and social regulations will be cast aside. The worst of the worst, practices like drilling offshore and in wildlife refuges, and mountaintop removal for coal will become commonplace. These will be merely the dregs of prehistoric energy reserves. The drilling will only prolong the endurance of industrial civilization for a matter of months or years, but ecological damage will be long-term or permanent (as is happening in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge). Because in our scenario there is no substantive resistance, this will all proceed unobstructed.

Investment in renewable industrial energy will also take place, although it will be belated and hampered by economic challenges, government bankruptcies, and budget cuts.3 Furthermore, long-distance power transmission lines will be insufficient and crumbling from age. Replacing and upgrading them will prove difficult and expensive. As a result, even once in place, electric renewables will only produce a tiny fraction of the energy produced by petroleum. That electric energy will not be suitable to run the vast majority of tractors, trucks, and other vehicles or similar infrastructure.

As a consequence, renewable energy will have only a minimal moderating effect on the energy cliff. In fact, the energy invested in the new infrastructure will take years to pay itself back with electricity generated. Massive infrastructure upgrades will actually steepen the energy cliff by decreasing the amount of energy available for daily activities. There will be a constant struggle to allocate limited supplies of energy under successive crises. There will be some rationing to prevent riots, but most energy (regardless of the source) will go to governments, the military, corporations, and the rich.

Energy constraints will make it impossible to even attempt any full-scale infrastructure overhauls like hydrogen economies (which wouldn’t solve the problem anyway). Biofuels will take off in many areas, despite the fact that they mostly have a poor ratio of energy returned on energy invested (EROEI). The EROEI will be better in tropical countries, so remaining tropical forests will be massively logged to clear land for biofuel production. (Often, forests will be logged en masse simply to burn for fuel.) Heavy machinery will be too expensive for most plantations, so their labor will come from slavery and serfdom under authoritarian governments and corporate feudalism. (Slavery is currently used in Brazil to log forests and produce charcoal by hand for the steel industry, after all.)4 The global effects of biofuel production will be increases in the cost of food, increases in water and irrigation drawdown for agriculture, and worsening soil erosion. Regardless, its production will amount to only a small fraction of the liquid hydrocarbons available at the peak of civilization.

All of this will have immediate ecological consequences. The oceans, wracked by increased fishing (to compensate for food shortages) and warming-induced acidity and coral die-offs, will be mostly dead. The expansion of biofuels will destroy many remaining wild areas and global biodiversity will plummet. Tropical forests like the Amazon produce the moist climate they require through their own vast transpiration, but expanded logging and agriculture will cut transpiration and tip the balance toward permanent drought. Even where the forest is not actually cut, the drying local climate will be enough to kill it. The Amazon will turn into a desert, and other tropical forests will follow suit.

Projections vary, but it’s almost certain that if the majority of the remaining fossil fuels are extracted and burned, global warming would become self-perpetuating and catastrophic. However, the worst effects will not be felt until decades into the future, once most fossil fuels have already been exhausted. By then, there will be very little energy or industrial capacity left for humans to try to compensate for the effects of global warming.

Furthermore, as intense climate change takes over, ecological remediation through perennial polycultures and forest replanting will become impossible. The heat and drought will turn forests into net carbon emitters, as northern forests die from heat, pests, and disease, and then burn in continent-wide fires that will make early twenty-first century conflagrations look minor.5 Even intact pastures won’t survive the temperature extremes as carbon is literally baked out of remaining agricultural soils.

Resource wars between nuclear states will break out. War between the US and Russia is less likely than it was in the Cold War, but ascending superpowers like China will want their piece of the global resource pie. Nuclear powers such as India and Pakistan will be densely populated and ecologically precarious; climate change will dry up major rivers previously fed by melting glaciers, and hundreds of millions of people in South Asia will live bare meters above sea level. With few resources to equip and field a mechanized army or air force, nuclear strikes will seem an increasingly effective action for desperate states.

If resource wars escalate to nuclear wars, the effects will be severe, even in the case of a “minor” nuclear war between countries like India and Pakistan. Even if each country uses only fifty Hiroshima-sized bombs as air bursts above urban centers, a nuclear winter will result.6Although lethal levels of fallout last only a matter of weeks, the ecological effects will be far more severe. The five megatons of smoke produced will darken the sky around the world. Stratospheric heating will destroy most of what remains of the ozone layer.7 In contrast to the overall warming trend, a “little ice age” will begin immediately and last for several years. During that period, temperatures in major agricultural regions will routinely drop below freezing in summer. Massive and immediate starvation will occur around the world.

That’s in the case of a small war. The explosive power of one hundred Hiroshima-sized bombs accounts for only 0.03 percent of the global arsenal. If a larger number of more powerful bombs are used—or if cobalt bombs are used to produce long-term irradiation and wipe out surface life—the effects will be even worse.8 There will be few human survivors. The nuclear winter effect will be temporary, but the bombing and subsequent fires will put large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, kill plants, and impair photosynthesis. As a result, after the ash settles, global warming will be even more rapid and worse than before.

Nuclear war or not, the long-term prospects are dim. Global warming will continue to worsen long after fossil fuels are exhausted. For the planet, the time to ecological recovery is measured in tens of millions of years, if ever.9 As James Lovelock has pointed out, a major warming event could push the planet into a different equilibrium, one much warmer than the current one.10 It’s possible that large plants and animals might only be able to survive near the poles.11 It’s also possible that the entire planet could become essentially uninhabitable to large plants and animals, with a climate more like Venus than Earth.

All that is required for this to occur is for current trends to continue without substantive and effective resistance. All that is required for evil to succeed is for good people to do nothing. But this future is not inevitable.

Image: public domain

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 30, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

We live in a surveillance state. As the Edward Snowden leaks and subsequent reporting has shown, government and private military corporations regularly target political dissidents for intelligence gathering. This information is used to undermine social movements, foment internecine conflict, discover weaknesses, and to get individuals thrown in jail for their justified resistance work.

As the idea of the panopticon describes, surveillance creates a culture of self-censorship. There aren’t enough people at security agencies to monitor everything, all of the time. Almost all of the data that is collected is never read or analyzed. In general, specific targeting of an individual for surveillance is the biggest threat. However, because people don’t understand the surveillance and how to defeat it, they subconsciously stop themselves from even considering serious resistance. In this way, they become self-defeating.

Surveillance functions primarily by creating a culture of paranoia through which the people begin to police themselves.