by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 23, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

We live inside an unprecedented surveillance state. Government and corporations monitor all non-encrypted digital communications for the purposes of political control and profit.

Political dissidents who wish to challenge capitalism need to learn to use more secure methods for communication, research, and other digital tasks. This guide is aimed at serious dissidents and revolutionaries. It is not aimed at the everyday activist, who will likely find these practices to be overkill.

Privacy vs. Security

It is important to understand that privacy and security are two different things. Privacy is related to anonymity. Security protects from eavesdropping, but does not necessarily anonymize.

To use an analogy: privacy means that the government doesn’t know who sent the message, but can read the contents. Security means they know who sent the message, but cannot read it. This is a simplified understanding, but it’s important to distinguish between the two.

In general, most aboveground activists who are already operating in the public sphere prioritize security. Underground operators and revolutionaries generally prioritize anonymity, since being unmasked and identified is the primary danger. Of course, this is a generalization. Both security and privacy are important for anyone involved in anti-capitalist resistance.

Note that these tools require some relatively advanced technological skills. However, it’s worth learning to use these tools. Whonix is probably the easiest to use for a beginner.

Operating Systems

An operating system, or OS, is the basic software running on a computing device. Windows and Mac OS are the most common operating systems. However, Linux is the most secure family of operating systems. This guide will look at operating systems for desktop computer use.

The following information is copied from the websites for these projects.

TAILS

Tails is a live system that aims to preserve your privacy and anonymity. It helps you to use the Internet anonymously and circumvent censorship almost anywhere you go and on any computer but leaving no trace unless you ask it to explicitly.

It is a complete operating system designed to be used from a USB stick or a DVD independently of the computer’s original operating system. It is Free Software and based on Debian GNU/Linux.

Tails comes with several built-in applications pre-configured with security in mind: web browser, instant messaging client, email client, office suite, image and sound editor, etc.

Tails relies on the Tor anonymity network to protect your privacy online:

- all software is configured to connect to the Internet through Tor

- if an application tries to connect to the Internet directly, the connection is automatically blocked for security.

Tor is an open and distributed network that helps defend against traffic analysis, a form of network surveillance that threatens personal freedom and privacy, confidential business activities and relationships, and state security.

Tor protects you by bouncing your communications around a network of relays run by volunteers all around the world: it prevents somebody watching your Internet connection from learning what sites you visit, and it prevents the sites you visit from learning your physical location.

Using Tor you can:

- be anonymous online by hiding your location,

- connect to services that would be censored otherwise;

- resist attacks that block the usage of Tor using circumvention tools such as bridges.

To learn more about Tor, see the official Tor website, particularly the following pages:

- Tor overview: Why we need Tor

- Tor overview: How does Tor work

- Who uses Tor?

- Understanding and Using Tor — An Introduction for the Layman

Using Tails on a computer doesn’t alter or depend on the operating system installed on it. So you can use it in the same way on your computer, a friend’s computer, or one at your local library. After shutting down Tails, the computer will start again with its usual operating system.

Tails is configured with special care to not use the computer’s hard-disks, even if there is some swap space on them. The only storage space used by Tails is in RAM, which is automatically erased when the computer shuts down. So you won’t leave any trace on the computer either of the Tails system itself or what you used it for. That’s why we call Tails “amnesic”.

This allows you to work with sensitive documents on any computer and protects you from data recovery after shutdown. Of course, you can still explicitly save specific documents to another USB stick or external hard-disk and take them away for future use.

https://tails.boum.org/

Whonix

Whonix is a desktop operating system designed for advanced security and privacy. Whonix mitigates the threat of common attack vectors while maintaining usability. Online anonymity is realized via fail-safe, automatic, and desktop-wide use of the Tor network. A heavily reconfigured Debian base is run inside multiple virtual machines, providing a substantial layer of protection from malware and IP address leaks. Commonly used applications are pre-installed and safely pre-configured for immediate use. The user is not jeopardized by installing additional applications or personalizing the desktop. Whonix is under active development and is the only operating system designed to be run inside a VM and paired with Tor.

Whonix utilizes Tor’s free software, which provides an open and distributed relay network to defend against network surveillance. Connections through Tor are enforced. DNS leaks are impossible, and even malware with root privileges cannot discover the user’s real IP address. Whonix is available for all major operating systems. Most commonly used applications are compatible with the Whonix design.

https://www.whonix.org/

Qubes OS

Qubes OS is a security-oriented operating system (OS). The OS is the software that runs all the other programs on a computer. Some examples of popular OSes are Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, Android, and iOS. Qubes is free and open-source software (FOSS). This means that everyone is free to use, copy, and change the software in any way. It also means that the source code is openly available so others can contribute to and audit it.

Why is OS security important?

Most people use an operating system like Windows or OS X on their desktop and laptop computers. These OSes are popular because they tend to be easy to use and usually come pre-installed on the computers people buy. However, they present problems when it comes to security. For example, you might open an innocent-looking email attachment or website, not realizing that you’re actually allowing malware (malicious software) to run on your computer. Depending on what kind of malware it is, it might do anything from showing you unwanted advertisements to logging your keystrokes to taking over your entire computer. This could jeopardize all the information stored on or accessed by this computer, such as health records, confidential communications, or thoughts written in a private journal. Malware can also interfere with the activities you perform with your computer. For example, if you use your computer to conduct financial transactions, the malware might allow its creator to make fraudulent transactions in your name.

Aren’t antivirus programs and firewalls enough?

Unfortunately, conventional security approaches like antivirus programs and (software and/or hardware) firewalls are no longer enough to keep out sophisticated attackers. For example, nowadays it’s common for malware creators to check to see if their malware is recognized by any signature-based antivirus programs. If it’s recognized, they scramble their code until it’s no longer recognizable by the antivirus programs, then send it out. The best of these programs will subsequently get updated once the antivirus programmers discover the new threat, but this usually occurs at least a few days after the new attacks start to appear in the wild. By then, it’s too late for those who have already been compromised. More advanced antivirus software may perform better in this regard, but it’s still limited to a detection-based approach. New zero-day vulnerabilities are constantly being discovered in the common software we all use, such as our web browsers, and no antivirus program or firewall can prevent all of these vulnerabilities from being exploited.

How does Qubes OS provide security?

Qubes takes an approach called security by compartmentalization, which allows you to compartmentalize the various parts of your digital life into securely isolated compartments called qubes.

This approach allows you to keep the different things you do on your computer securely separated from each other in isolated qubes so that one qube getting compromised won’t affect the others. For example, you might have one qube for visiting untrusted websites and a different qube for doing online banking. This way, if your untrusted browsing qube gets compromised by a malware-laden website, your online banking activities won’t be at risk. Similarly, if you’re concerned about malicious email attachments, Qubes can make it so that every attachment gets opened in its own single-use disposable qube. In this way, Qubes allows you to do everything on the same physical computer without having to worry about a single successful cyberattack taking down your entire digital life in one fell swoop.

Moreover, all of these isolated qubes are integrated into a single, usable system. Programs are isolated in their own separate qubes, but all windows are displayed in a single, unified desktop environment with unforgeable colored window borders so that you can easily identify windows from different security levels. Common attack vectors like network cards and USB controllers are isolated in their own hardware qubes while their functionality is preserved through secure networking, firewalls, and USB device management. Integrated file and clipboard copy and paste operations make it easy to work across various qubes without compromising security. The innovative Template system separates software installation from software use, allowing qubes to share a root filesystem without sacrificing security (and saving disk space, to boot). Qubes even allows you to sanitize PDFs and images in a few clicks. Users concerned about privacy will appreciate the integration of Whonix with Qubes, which makes it easy to use Tor securely, while those concerned about physical hardware attacks will benefit from Anti Evil Maid.

How does Qubes OS compare to using a “live CD” OS?

Booting your computer from a live CD (or DVD) when you need to perform sensitive activities can certainly be more secure than simply using your main OS, but this method still preserves many of the risks of conventional OSes. For example, popular live OSes (such as Tails and other Linux distributions) are still monolithic in the sense that all software is still running in the same OS. This means, once again, that if your session is compromised, then all the data and activities performed within that same session are also potentially compromised.

How does Qubes OS compare to running VMs in a conventional OS?

Not all virtual machine software is equal when it comes to security. You may have used or heard of VMs in relation to software like VirtualBox or VMware Workstation. These are known as “Type 2” or “hosted” hypervisors. (The hypervisor is the software, firmware, or hardware that creates and runs virtual machines.) These programs are popular because they’re designed primarily to be easy to use and run under popular OSes like Windows (which is called the host OS, since it “hosts” the VMs). However, the fact that Type 2 hypervisors run under the host OS means that they’re really only as secure as the host OS itself. If the host OS is ever compromised, then any VMs it hosts are also effectively compromised.

By contrast, Qubes uses a “Type 1” or “bare metal” hypervisor called Xen. Instead of running inside an OS, Type 1 hypervisors run directly on the “bare metal” of the hardware. This means that an attacker must be capable of subverting the hypervisor itself in order to compromise the entire system, which is vastly more difficult.

Qubes makes it so that multiple VMs running under a Type 1 hypervisor can be securely used as an integrated OS. For example, it puts all of your application windows on the same desktop with special colored borders indicating the trust levels of their respective VMs. It also allows for things like secure copy/paste operations between VMs, securely copying and transferring files between VMs, and secure networking between VMs and the Internet.

How does Qubes OS compare to using a separate physical machine?

Using a separate physical computer for sensitive activities can certainly be more secure than using one computer with a conventional OS for everything, but there are still risks to consider. Briefly, here are some of the main pros and cons of this approach relative to Qubes:

Pros

- Physical separation doesn’t rely on a hypervisor. (It’s very unlikely that an attacker will break out of Qubes’ hypervisor, but if one were to manage to do so, one could potentially gain control over the entire system.)

- Physical separation can be a natural complement to physical security. (For example, you might find it natural to lock your secure laptop in a safe when you take your unsecure laptop out with you.)

Cons

- Physical separation can be cumbersome and expensive, since we may have to obtain and set up a separate physical machine for each security level we need.

- There’s generally no secure way to transfer data between physically separate computers running conventional OSes. (Qubes has a secure inter-VM file transfer system to handle this.)

- Physically separate computers running conventional OSes are still independently vulnerable to most conventional attacks due to their monolithic nature.

- Malware which can bridge air gaps has existed for several years now and is becoming increasingly common.

(For more on this topic, please see the paper Software compartmentalization vs. physical separation.)

Get Qubes

Qubes OS is free to use, can run , and integrates with Whonix for secure web browsing and internet usage via Tor.

https://www.qubes-os.org/

Summary

- TAILS is a “live” OS that runs from a USB stick or DVD, and can be used to browse anonymously from any computer. It doesn’t save files or history; it is designed mainly for ephemeral use.

- Whonix is an OS made to run as a virtual machine, and provide security and anonymity for web browsing by routing all connections via the Tor browser.

- Qubes OS is made to use as a permanent OS, and uses compartmentalization for security. Whonix is automatically installed inside Qubes. Used by Edward Snowden.

Image: Chris, https://www.flickr.com/photos/44730926@N07/32681532676, CC BY 2.0

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 11, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: power line sabotaged by the African National Congress

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Tactics and Targets” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

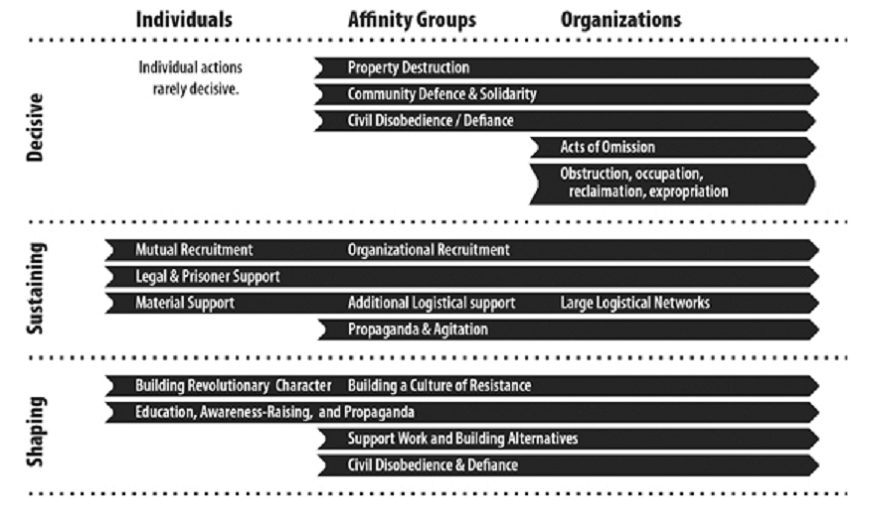

Some tactics can be carried out underground—like general liberation organizing and propaganda—but are more effective aboveground. Where open speech is dangerous, these types of tactics may move underground to adapt to circumstances. The African National Congress, in its struggle for basic human rights, should have been allowed to work aboveground, but that simply wasn’t possible in repressive apartheid South Africa.

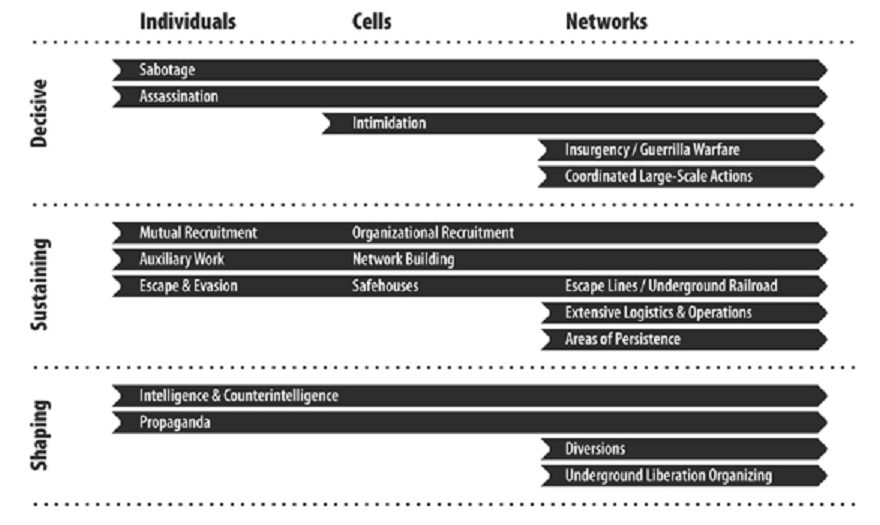

And then there are tactics that are only appropriate for the underground, obligate underground operations that depend on secrecy and security. Escape lines and safehouses for persecuted persons and resistance fugitives are example of those operations. There’s a reason it’s called the “underground” railroad—it’s not transferable to the aboveground, because the entire operation is completely dependent on secrecy. Clandestine intelligence gathering is another case; the French Resistance didn’t gather enemy secrets by walking up to the nearest SS office and asking for a list of their troop deployments.

Some tactics are almost always limited to the underground:

- Clandestine intelligence

- Escape

- Sabotage and attacks on materiel

- Attacks on troops

- Intimidation

- Assassination

As operational categories, intelligence and escape are pretty clear, and few people looking at historical struggles will deny the importance of gathering information or aiding people to escape persecution. Of course, some abolitionists in the antebellum US didn’t support the Underground Railroad. And many Jewish authorities tried to make German Jews cooperate with registration and population control measures. In hindsight, it’s clear to us that these were huge strategic and moral mistakes, but at the time it may only have been clear to the particularly perceptive and farsighted.

Sabotage and attacks on materiel are overlapping tactics. Oftentimes, sabotage is more subtle; for example, machinery may be disabled without being recognized as sabotage. Attacks on materiel are often more overt efforts to destroy and disable the adversary’s equipment and supplies. In any case, they form an inclusive continuum, with sabotage on the more clandestine end of the scale.

It’s true that harm can be caused through sabotage, and that sabotage can be a form of violence. But allowing a machine to operate can also be more violent than sabotaging it. Think of a drift net. How many living creatures does a drift net kill as it passes through the ocean, regardless of whether it’s being used for fishing or not? Destroying a drift net—or sabotaging a boat so that a drift net cannot be deployed—would save countless lives. Sabotaging a drift net is clearly a nonviolent act. However, you could argue conversely that not sabotaging a drift net (provided you had the means and opportunity) is a profoundly violent act—indeed, violent not just for individual creatures, but violent on a massive, ecological scale. The drift net is an obvious example, but we could make a similar (if longer and more roundabout) argument for most any industrial machinery.

You’re opposed to violence? So where’s your monkey wrench?

Sabotage is not categorically violent, but the next few underground categories may involve violence on the part of resisters. Attacks on troops, intimidation, assassination, and the like have been used to great effect by a great many resistance movements in history. From the assassination of SS officers by escaping concentration camp inmates to the killing of slave owners by revolting slaves to the assassination of British torturers by Michael Collins’s Twelve Apostles, the selective use of violence has been essential for victory in a great many resistance and liberation struggles.

Attacks on troops are common where a politically conscious population lives under overt military occupation. In these situations, there is often little distinction between uniformed militaries, police, and government paramilitaries (like the Black and Tans or the miliciens). The violence may be secondary. Sometimes the resistance members are trying to capture equipment, documents, or intelligence; how many guerrillas have gotten started by killing occupying soldiers to get guns? Sometimes the attack is intended to force the enemy to increase its defensive garrisons or pull back to more defended positions and abandon remote or outlying areas. Sometimes the point is to demonstrate the strength or capabilities of the resistance to the population and the occupier. Sometimes the point is actually to kill enemy soldiers and deplete the occupying force. Sometimes the troops are just sentries or guards, and the primary target is an enemy building or facility.

Of course, for these attacks to happen successfully, they must follow the basic rules of asymmetric conflict and general good strategy. When raiding police stations for guns, the IRA chose remote, poorly guarded sites. Guerrillas like to go after locations with only one or two sentries, and any attack on those small sites forces the occupier to make tough choices: abandon an outpost because it can’t be adequately defended or increase security by doubling the number of guards. Either benefits the resistance and saps the resources of the occupier.

And although in industrial conflicts it’s often true that destroying materiel and disrupting logistics can be very effective, that’s sometimes not enough. Take American involvement in the Vietnam War. The American cost in terms of materiel was enormous—in modern dollars, the war cost close to $600 billion. But it wasn’t the cost of replacing helicopters or fueling convoys that turned US sentiment against the war. It was the growing stream of American bodies being flown home in coffins.

There’s a world of difference—socially, organizationally, psychologically—between fighting the occupation of a foreign government and the occupation of a domestic one. There’s something about the psychology of resistance that makes it easier for people to unite against a foreign enemy. Most people make no distinction between the people living in their country and the government of that country, which is why the news will say “America pulls out of climate talks” when they are talking about the US government. This psychology is why millions of Vietnamese people took up arms against the American invasion, but only a handful of Americans took up arms against that invasion (some of them being soldiers who fragged their officers, and some of them being groups like the Weather Underground who went out of their way not to injure the people who were burning Vietnamese peasants alive by the tens of thousands). This psychology explains why some of the patriots who fought in the French Resistance went on to torture people to repress the Algerian Resistance. And it explains why most Germans didn’t even support theoretical resistance against Hitler a decade after the war.

This doesn’t bode well for resistance in the minority world, where the rich and powerful minority live. People in poorer countries may be able to rally against foreign corporations and colonial dictatorships, but those in the center of empire contend with power structures that most people consider natural, familiar, even friendly. But these domestic institutions of power—be they corporate or governmental—are just as foreign, and just as destructive, as an invading army. They may be based in the same geographic region as we are, but they are just as alien as if they were run by robots or little green men.

Intimidation is another tactic related to violence that is usually conducted underground. This tactic is used by the “Gulabi Gang” (also called the Pink Sari Gang) of Uttar Pradesh, a state in India.4 Leader Sampat Pal Devi calls it “a gang for justice.” The Gulabi Gang formed as a response to deeply entrenched and violent patriarchy (especially domestic and sexual violence) and caste-based discrimination. The members use a variety of tactics to fight for women’s rights, but their “vigilante violence” has gained global attention. With over 500 members, they can exert considerable force. They’ve stopped child marriages. They’ve beaten up men who perpetrate domestic violence. The gang forced the police to register crimes against Untouchables by slapping police officers until they complied. They’ve hijacked trucks full of food that were going to be sold for a profit by corrupt officials. Their hundreds of members practice self-defense with the lathi (a traditional Indian stick or staff weapon). It’s no surprise their ranks are growing.

Gulabi Gang

Many of these examples tread the boundary of our aboveground-underground distinction. When struggling against systems of patriarchy that have closely allied themselves with governments and police (which is to say, virtually all systems of patriarchy), women’s groups that have been forced to use violence or the threat of violence may have to operate in a clandestine fashion at least some of the time. At the same time, the effects of their self-defense must be prominent and publicized. Killing a rapist or abuser has the obvious benefit of stopping any future abuses by that individual. But the larger beneficial effect is to intimidate other would-be abusers—to turn the tables and prevent other incidents of rape or abuse by making the consequences for perpetrators known. The Gulabi Gang is so popular and effective in part because they openly defy abuses of male power, so the effect on both men and women is very large. Their aboveground defiance rallies more support than they could by causing abusive men to die in a series of mysterious accidents. The Black Panthers were similarly popular because they publically defied the violent oppression meted out by police on a daily basis. And by openly bearing arms, they were able to intimidate the police (and other people, like drug dealers) into reducing their abuses.

There are limits to the use of intimidation on those in power. The most powerful people are the most physically isolated—they might have bodyguards or live in gated houses. They have far more coercive force at their fingertips than any resistance movement. For that reason, resistance groups have historically used intimidation primarily on low-level functionaries and collaborators who give information to those in power when asked or who cooperate with them in a more limited way.

No resistance movement wants to engage in needless cycles of violence and retribution with those in power. But a refusal to employ violent tactics when they are appropriate will very likely lead to more violence. Many abolitionists did not support John Brown because they considered his plan for a defensive liberation struggle to be too violent—but Brown’s failure led inevitably to a lengthy and gruesome Civil War (as well as continued years of bloody slavery), a consequence that was orders of magnitude more violent than Brown’s intended plan.

This leads us to the last major underground tactic: assassination.

In talking about assassination (or any attack on humans) in the context of resistance, two key questions must be asked. First, is the act strategically beneficial, that is, would assassination further the strategy of the group? Second, is the act morally just, given the person in question? (The issue of justice is necessarily particular to the target; it’s assumed that the broader strategy incorporates aims to increase justice.)

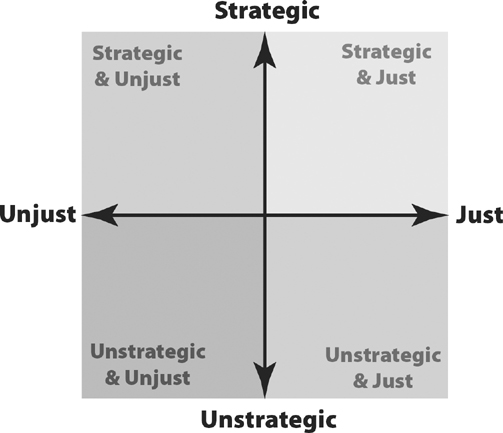

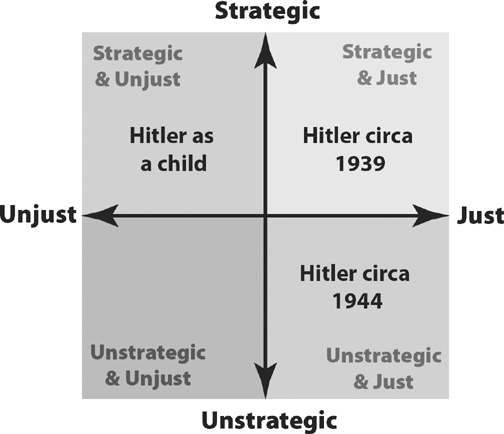

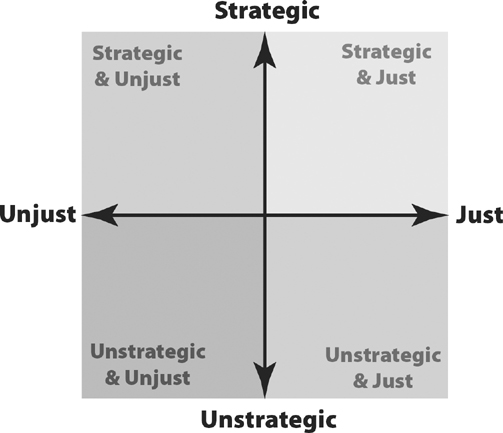

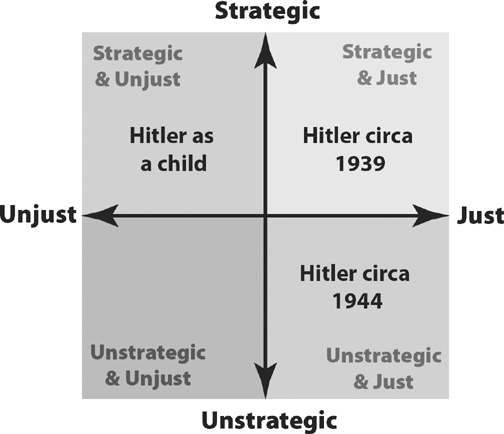

As is shown on my two-by-two grid of all combinations, an assassination may be strategic and just, it may be strategic and unjust, it may be unstrategic but just, or it may be both unstrategic and unjust. Obviously, any action in the last category would be out of the question. Any action in the strategic and just category could be a good bet for an armed resistance movement. The other two categories are where things get complex.

Figure 13-3

Once Hitler had risen to power in the late 1930s, though, his aim was clear, as he had already been whipping up hate and expanding his control of Nazi Germany. At that point, it would have been both strategic and just to assassinate him. Indeed, elements in the Wehrmacht (army) and the Abwehr (intelligence) considered it, because they knew what Hitler was planning to do. Unfortunately, they were indecisive, and did not commit to the plan. Hitler soon began invading Germany’s neighbors, and as his popularity soared, the assassination plan was shelved. It was years before inside elements would actually stage an assassination attempt.

Figure 13-4

That famous attempt took place—and failed—on July 20, 1944.5What’s interesting is that the Allies were also considering an attempt on Hitler’s life, which they called Operation Foxley. They knew that Hitler routinely went on walks alone in a remote area, and devised a plan to parachute in two operatives dressed as German officers, one of them a sniper, who would lay in wait and assassinate Hitler when he walked by. The plan was never enacted because of internal controversy. Many in the SOE and British government believed that Hitler was a poor strategist, a maniac whose overreach would be his downfall. If he were assassinated, they believed, his replacement (likely Himmler) would be a more competent leader, and this would draw out the war and increase Allied losses. In the opinion of the Allies it was unquestionably just to kill Hitler, but no longer strategically beneficial.

There is no shortage of situations where assassination would have been just, but of questionable strategic value. Resistance groups pondering assassination have many questions to ask themselves in deciding whether they are being strategic or not. What is the value of this potential target to the enemy? Is this an exceptional person or does his or her influence come from his or her role in the organization? Who would replace this person, and would that person be better or worse for the struggle? Will it make any difference on an organizational scale or is the potential target simply an interchangeable cog? Uniquely valuable individuals make uniquely valuable targets for assassination by resistance groups.

Of course, in a military context (and this overlaps with attacks on troops), snipers routinely target officers over enlisted soldiers. In theory, officers or enlisted soldiers are standardized and replaceable, but, in practice, officers constitute more valuable targets. There’s a difference between theoretical and practical equivalence; there might be other officers to replace an assassinated one, but the replacement might not arrive in a timely manner nor would he have the experience of his predecessor (experience being a key reason that Michael Collins assassinated intelligence officers). That said, snipers don’t just target officers. Snipers target any enemy soldiers available, because war is essentially about destroying the other side’s ability to wage war.

The benefits must also outweigh costs or side effects. Resistance members may be captured or killed in the attempt. Assassination also provokes a major response—and major reprisals—because it is a direct attack on those in power. When SS boss Reinhard Heydrich (“the butcher of Prague”) was assassinated in 1942, the Nazis massacred more than 1,000 Czech people in response. In Canada, martial law (via the War Measures Act) has only ever been declared three times—during WWI and WWII, and again after the assassination of the Quebec Vice Premier of Quebec by the Front de Libération du Québec. Remember, aboveground allies may bear the brunt of reprisals for assassinations, and those reprisals can range from martial law and police crackdowns to mass arrests or even executions.

There’s an important distinction to be made between assassination as an ideological tactic versus as a military tactic. As a military tactic, employed by countless snipers in the history of war, assassination decisively weakens the adversary by killing people with important experience or talents, weakening the entire organization. Assassination as an ideological tactic—attacking or killing prominent figures because of ideological disagreements—almost always goes sour, and quickly. There are few more effective ways to create martyrs and trigger cycles of violence without actually accomplishing anything decisive. The assassination of Michael Collins, for example, by his former allies led only to bloody civil war.

DECISIVE OPERATIONS UNDERGROUND

Individuals working underground focus mostly on small-scale acts of sabotage and subversion that make the most of their skill and opportunity. Because they lack escape networks, and because they must be opportunistic, it’s ideal for their actions to be what French resisters called insaisissable–untraceable or appearing like an accident—unless the nature of the action requires otherwise.

Individual saboteurs are more effective with some informal coordination—if, for example, a general day of action has been called. It also helps if the individuals seize an opportunity by springing into action when those in power are already off balance or under attack, like the two teenaged French girls who sabotaged trains carrying German tanks after D-Day, thus hampering the German ability to respond to the Allied landing.

One individual resister who attempted truly decisive action was Georg Elser, a German-born carpenter who opposed Hitler from the beginning. When Hitler started the World War II in 1939, Elser resolved to assassinate Hitler. He spent hours every night secretly hollowing out a hidden cavity in the beer hall where Hitler spoke each year on the anniversary of his failed coup. Elser used knowledge he learned from working at a watch factory to build a timer, and planted a bomb in the hidden cavity. The bomb went off on time, but by chance Hilter left early and survived. When Elser was captured, the Gestapo tortured him for information, refusing to believe that a single tradesperson with a grade-school education could come so close to killing Hitler without help. But Elser, indeed, worked entirely alone.

Underground networks can accomplish decisive operations that require greater coordination, numbers, and geographic scope. This is crucial. Large-scale coordination can turn even minor tactics—like simple sabotage—into dramatically decisive events. Underground saboteurs from the French Resistance to the ANC relied on simple techniques, homemade tools, and “appropriate technology.” With synchronization between even a handful of groups, these underground networks can make an entire economy grind to a halt.

The change is more than quantitative, it’s qualitative. A massively coordinated set of actions is fundamentally different from an uncoordinated set of the same actions. Complex systems respond in a nonlinear fashion. They can adapt and maintain equilibrium in the face of small insults, minor disruptions. But beyond a certain point, increasing attacks undermine the entire system, causing widespread failure or collapse.

Because of this, coordination is perhaps the most compelling argument for underground networks over mere isolated cells. I’ll discuss coordinated actions in more detail in the next chapter: Decisive Ecological Warfare.

SUSTAINING OPERATIONS UNDERGROUND

Since individuals working underground are pretty much alone, they have very few options for sustaining operations. They may potentially recruit or train others to form an underground cell. Or they may try to make contact with other people or groups (either underground or aboveground) to work as an auxiliary of some kind, such as an intelligence source, especially if they are able to pass on information from inside a government or corporate bureaucracy. But making this connection is often very challenging.

Individual escape and evasion may also be a decisive or sustaining action, at least on a small scale. Antebellum American slavery offers some examples. In a discussion of slave revolts, historian Deborah Gray White explains, “[I]ndividual resistance did not overthrow slavery, but it might have encouraged masters to make perpetual servitude more tolerable and lasting. Still, for many African Americans, individual rebellions against the authority of slaveholders fulfilled much the same function as did the slave family, Christianity, and folk religion: it created the psychic space that enabled Black people to survive.”6

Historian John Michael Vlach observes: “Southern plantations actually served as the training grounds for those most inclined to seek their freedom.” Slaves would often escape for short periods of time as a temporary respite from compelled labor before returning to plantations, a practice often tolerated by owners. These escapes provided opportunities to build a camp or even steal and stock up on provisions for another escape. Sometimes slaves would use temporary escapes as attempts to compel better behavior from plantation owners.7 In any case, these escapes and minor thefts helped to build a culture of resistance by challenging the omnipotence of slave owners and reclaiming some small measure of autonomy and freedom.

Individuals have some ability to assert power, but recruitment is key in underground sustaining operations. A single cell can gather or steal equipment and supplies for itself, but it can’t participate in wider sustaining operations unless it forms a network by recruiting organizationally, training new members and auxiliaries, and extending into new cells. One underground cell is all you need to create an entire network. Creating the first cell—finding those first few trusted comrades, developing communications and signals—is the hardest part, because other cells can be founded on the same template, and the members of the existing cell can be used to recruit, screen, and train new members.

Even though it’s inherently difficult for an underground group to coordinate with other distinct underground groups, it is possible for an underground cell to offer supporting operations to aboveground campaigns. It was an underground group—the Citizen’s Commission to Investigate the FBI—that exposed COINTELPRO, and allowed many aboveground groups to understand and counteract the FBI’s covert attacks on them. And the judicious use of sabotage could buy valuable time for aboveground groups to mobilize in a given campaign.

There are clearly campaigns in which aboveground groups have no desire for help from the underground, in which case it’s best for the underground to focus on other projects. But the two can work together on the same strategy without direct coordination. If a popular aboveground campaign against a big-box store or unwanted new industrial site fails because of corrupt politicians, an underground group can always pick up the slack and damage or destroy the facility under construction. Sometimes people argue that there’s no point in sabotaging anything, because those in power will just build it again. But there may come a day when those in power start to say “there’s no point in building it—they’ll just burn it down again.”

Underground cells may also run a safehouse or safehouses for themselves and allies. Single cells can’t run true underground railroads, but even single safehouses are valuable in dealing with repression or persecution. A key challenge in underground railroads and escape lines is that the escapees have to make contact with underground helpers without exposing themselves to those in power. Larger, more “formalized” underground networks have specialized methods and personnel for this, but a single cell running a safehouse may not. If an underground cell is conscientious, its members will be the only ones aware that the safehouse exists at all, which puts the burden on them to contact someone who requires refuge.

Mass persecution and repression has happened enough times in history to provide a wealth of examples where this would be appropriate. The internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II is quite well-known. Less well-known is the internment of hundreds of leftist radicals and labor activists starting in 1940. Leading activists associated with certain other ethnic organizations (especially Ukrainian), the labor movement, and the Communist party were arrested and sent to isolated work camps in various locations around Canada. A few managed to go into hiding, at least temporarily, but the vast majority were captured and sent to the camps, where a number of them died.8 In a situation like that, an underground cell could offer shelter to a persecuted aboveground activist or activists on an invitational basis without having to expose themselves openly.

Many of these operations work in tandem. Resistance networks from the SOE to the ANC have used their escape lines and underground railroads to sneak recruits to training sites in friendly areas and then infiltrated those people back into occupied territory to take up the fight.

Underground networks may be large enough to create “areas of persistence” where they exert a sizeable influence and have developed an underground infrastructure rooted in a culture of resistance. If an underground network reaches a critical mass in a certain area, it may be able to significantly disrupt the command and control systems of those in power, allowing resisters both aboveground and underground a greater amount of latitude in their work.

There are a number of examples of resistance movements successfully creating areas of persistence. The Zapatistas in Mexico exert considerable influence in Chiapas, so much so that they can post signs to that effect. “You are in Zapatista rebel territory” proclaims one typical sign (translated from Spanish). “Here the people give the orders and the government obeys.” The posting also warns against drug and alcohol trafficking or use and against the illegal sale of wood. “No to the destruction of nature.”9 Other Latin American resistance movements, such as the FMLN in El Salvador and the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, created areas of persistence in Latin America in the late twentieth century. Hamas in Palestine and Hezbollah in Lebanon have similarly established large areas of persistence in the Middle East.

SHAPING OPERATIONS UNDERGROUND

Because working underground is dangerous and difficult, effective resisters mostly focus on decisive and sustaining operations that will be worth their while. That said, there are still some shaping operations for the underground.

This includes general counterintelligence and security work. Ferreting out and removing informers and infiltrators is a key step in allowing resistance organizations of every type to grow and resistance strategies to succeed. Neither the ANC nor the IRA were able to win until they could deal effectively with such people.

Underground cells can also carry out some specialized propaganda operations. For reasons already discussed, propaganda in general is best carried out by aboveground groups, but there are exceptions. In particularly repressive regimes, basic propaganda and education projects must move underground to continue to function and protect identities. Underground newspapers and forms of pirate radio are two examples. Entire, vast underground networks have been built on this principle. In Soviet Russia, samizdat was the secret copying of and distribution of illegal or censored texts. A person who received a piece of illegal literature—say, Vaclav Havel’s Power of the Powerless—was expected to make more copies and pass them on. In a pre–personal computer age, in a country where copy machines and printing presses were under state control, this often meant laboriously copying books by hand or typewriter.

Underground groups may also want to carry out certain high-profile or spectacular “demonstration” actions to demonstrate that underground resistance is possible and that it is happening, and to offer a model for a particular tactic or target to be emulated by others. Of course, demonstrative actions may be valuable, but they can also degrade into symbolism for the sake of symbolism. Plenty of underground groups, the Weather Underground included, hoped to use their actions to “ignite a revolution.” But, in general—and especially when “the masses” can’t be reasonably expected to join in the fight—underground groups must get their job done by being as decisive as possible.

Editor’s note: continue reading at Target Selection.

by DGR News Service | Nov 9, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

November 9, 2018

by Max Wilbert

Deep Green Resistance

max@maxwilbert.org

https://www.deepgreenresistance.org

Current atmospheric CO2 level: 406 PPM

A free monthly newsletter providing analysis and commentary on ecology, global capitalism, empire, and revolution.

For back issues, to read this issue online, or to subscribe via email or RSS, visit the Resistance News web page.

These essays also appear on the DGR News Service, which also includes an active comment section.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

In this issue:

- Underground action calendar

- Honduran Migrant March: A Refugee Crisis Caused by US Policy and US Partners

- Apocalypto

- Run for Sacred Water

- Oppression and Subordination

- Guiding Principles of Deep Green Resistance

- Evaluating Strategy

- Capitalism is Killing the World’s Wildlife Populations, not ‘Humanity’

- Submit your material to the Deep Green Resistance News Service

- Abovegound tactics and operations

- Further news and recommended reading / podcasts

- How to support DGR or get involved

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

“We’ve got to stop thinking like vandals and start thinking like field generals.”

– Lierre Keith

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Underground Action Calendar

[Link] The Underground Action Calendar exists to publicize and normalize the use of militant and underground tactics in the fight for justice and sustainability. We include below a wide variety of actions from struggles around the world, especially those in which militants target infrastructure, because we believe this sort of action is necessary to dismantle civilization. Listing an action does not necessarily mean we support or stand behind the goals, strategies, or tactics of those actionists.

This page highlights specific actions. See also our Resistance Profiles for broader information on the strategies, tactics, goals, and effectiveness of various historic and contemporary resistance groups.

If you know of a published action appropriate to add to the Calendar, contact us at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

NOTE: We ONLY accept communications about actions that are already publicly known in one form or another. DO NOT send original communiques directly to this email address. THIS IS NOT A SECURE MEANS OF COMMUNICATION.

Several recent entries on the Underground Action Calendar:

——————————————————

| June 2018 |

Pennsylvania, US |

Liquidation system of excavator on pipeline construction site sabotaged, in such a way as to inflict permanent damage |

Vehicle |

Monkey

wrenching |

| May 24, 2018 |

Birima, Kirkuk, Iraq |

Two power lines destroyed simultaneously, triggering blackouts in two cities |

Powerline, Towers |

|

| May 2018 |

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

Cable housing of cell tower torched |

Telecomms |

Arson |

| April 3, 2018 |

Exton, Pennsylvania, US |

Tractors for pipeline construction sabotaged |

Vehicle |

Monkey

wrenching |

View the full Underground Action Calendar database, which contains hundreds of actions dating back more than 50 years, here.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Honduran Migrant March: A Refugee Crisis Caused by US Policy and US Partners

[Link] by Honduras Solidarity Network

On October 12, 2018, hundreds of women, men, children, youth and the elderly decided to leave Honduras as a desperate response to survive. The massive exodus that began in the city of San Pedro Sula, reached more than 3 thousand people by the time the group crossed to Guatemala. The caravan, which is headed north to Mexico first, and to the United States as the goal- is the only alternative this people have to reach a bit of the dignity that has been taken from them. They are not alone in their journey. Various waves of Hondurans, whose numbers increase every hour, are being contained by Honduran security forces on their border with El Salvador and Guatemala.

The Honduras Solidarity Network in North America condemns any threats and acts of repression against the refugee caravan, human rights activists and journalists that accompany their journey. The conditions of violence, marginalization and exploitation in which this refugee crisis find its origins, have been created, maintained and reproduced by US-backed social, economic and military interventionist policies, with the support of its Canadian and regional allies. We call on people in the US to reject the criminalization, prosecution, detention, deportation and family separation that threaten the members of this march and the lives of all those refugees forced from their homes in the same way. We urge a change of US policy in Honduras and to cut off security aid to stop human rights abuses and government violence against Hondurans.

This refugee crisis has been exacerbated by the governments of Guatemala and Mexico, who subservient to Donald Trump’s administration, have chosen the path of repression. Bartolo Fuentes, a Honduran journalist and spokesperson for the refugees, has been detained in Guatemala. Meanwhile the Mexican government has sent two planeloads of its National Police to the border with Guatemala. Irineo Mujica, a migrant rights activist and photojournalist, was arrested in Chiapas by agents of the Mexican National Institute of Migration when he was getting ready to support the Honduran migrant march. Today (Friday) in the afternoon, tear gas was fired into the group as they tried to come into Mexico on the border bridge. Honduran human rights organizations report that a 7 month old baby was killed.

The massive forced flight of people from Honduras is not new; it is the legacy of US intervention in the country. Since the 2009 US-backed coup in Honduras, the post-coup regime has perpetuated a system based on disregard for human rights, impunity, corruption, repression and the influence of organized crime groups in the government and in the economic power elite. Since the coup, we have seen the destruction of public education and health services through privatization. The imposition of mining, hydro-electric mega-projects and the concentration of land in agro-industry has plunged 66 percent of the Honduran population into poverty and extreme poverty. In the last 9 years, we have witnessed how the murder of Berta Cáceres and many other activists, indigenous leaders, lawyers, journalists, LGBTQ community members and students has triggered a humanitarian crisis. This crisis is reflected in the internal displacement and the unprecedented exodus of the Honduran people that has caught the public’s eye during recent days.

The fraudulent November 2017 elections, in which Juan Orlando Hernández -president since questionable elections in 2013- was re-elected for a second term in violation of the Honduran constitution, sparked a national outrage. The people’s outrage was confronted by an extremely violent government campaign with military and US-trained security forces to suppress the protests against the fraud. The result of the repression was more than 30 people killed by government forces, more than a thousand arrested and there are currently 20 political prisoners being held in pre-trial prison.

To the repression, intimidation and criminalization faced by the members of the refugee caravan, we respond with a call for solidarity from all the corners of the world. In the face of the violence that has led to the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Hondurans, we demand an end to US military and security aid to Juan Orlando’s regime, not as the blackmail tool used by Donald Trump, but as a way to guarantee the protection of the human rights of the Honduran people. We demand justice for Berta Cáceres, for all the victims of political violence as a consequence of the post coup regime, and the approval of the Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act H.R. 1299. We demand freedom for all the political prisoners in Honduras. We demand the US end the criminalization, imprisonment, separation, deportation and killing of migrants and refugees.

Today we fight so that every step, from Honduras to the north of the Americas, is dignified and free.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Apocalypto

[Link] by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

It is very difficult for me to live in this culture.

I just can’t psychologically survive in the high performance society, where everyone is passionately exploiting themselves, while all life on this planet is being destroyed.

I have severe depression and anxiety disorders, and I have to take good care of myself to be able to take care of my son.

It is very difficult for people who have never experienced poverty to understand what poverty means. The constant nagging fear. The permanent stress and psychological terror of state authorities on which you are dependent, that harass you and try to keep you small and oppressed.

Now they want me to work underpaid, shitty jobs again. I already had a stroke not long ago. I can’t do these jobs and I can‘t stand the pressure.

I live in the age of the greatest mass extinction in 65 million years. And the cause of this mass extinction is our glorious western civilization.

Empire.

Indeed, almost all imperial forces have joined into one: The West.

“In the last eighteen months, the greatest build-up of military forces since World War Two — led by the United States — is taking place along Russia’s western frontier…The United States is encircling China with a network of bases, with ballistic missiles, battle groups, nuclear-armed bombers,” writes John Pilger.

Looks like the West is encircling the strongest probable future enemies, preparing for war.

Full spectrum dominance.

The understanding of the fact that this culture is always at war, and will indeed kill all life on planet earth made me shift my loyalty and become an activist.

My loyalty does not belong to empire and industrial capitalism. My loyalty belongs to the suppressed, the poor, the dying planet.

Where are you when we need people to take responsibility for our fellow creatures, human and nonhuman, and defend them? Always working on your professional self-fulfillment, performing until you burn out.

Do you distract yourself so manically with your work, so you don’t have to see what is happening around us? That the insects disappear, the songbirds disappear, the masses impoverish?

That the West is already bombing the near and middle east to ashes and dust and prepares for more, while you try to overtake yourself, become faster and better, without even stopping once to understand the obvious fact that this system is heading for collapse?

Instead you wonder where all the refugees come from. (Of course they come for a share of the cake of our western wealth, they might even try to take your precious job! You better join one of the aspiring right-wing movements.)

Imperialism creates the illusion of wealth as far as the masses are concerned. It usually serves to hide the fact that the ruling classes are gobbling up the natural resources of the home territory in an improvident manner and are otherwise utilizing the national wealth largely for their own purposes. Eventually the general public is called upon to pay for all of this, frequently after the military machine can no longer maintain external aggression.

–Jack Forbes

Capitalism 2.0 comes with a like-button and a smiling emoji, and it will always tell you that everything is fine.

Capitalism is exploitation, but neoliberalism is the smart self-exploitation of the alienated and indoctrinated individual. Exploitation on steroids.

Indoctrination is cheaper and more efficient than violence. It is thus called “soft power.” It works with research-based psycho-politics, and the smart manipulation of human feelings and desires.

Capitalism creates an exploited class of workers that will probably organize and resist (as it did many times).

Neoliberalism creates a population of totally alienated and indoctrinated machine-like zombies, who suppress their own humanity. Each individual a perfect slave, with a software programmed in its brain. Owner Inside®.

Zombie apocalypse.

You might already be a zombie, living in your middle class-bubble or your digital hallucination, but I am still a human being, sensitive as a frightened child, with a healthy portion of empathy and love. I‘m trying to live awake and conscious in this real, physical world, and what I see is mass extinction, ecological catastrophe and imperialist wars. Trauma.

Facing the truth isn’t easy.

I carry a trauma with me from reading A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies by Bartolome de Las Casas.

I carry a trauma with me from reading Jack Forbes’ Only Approved Indians. He writes: “If a creature learns to completely accept captivity or slavery, if they erase all thoughts of freedom, they can suppress the pain. But if one wants to be free, one has to face the pain; one has to agonize, to suffer, through all of the terror.”

That’s where you are. Completely accepting captivity and slavery, driving out the pain.

That‘s where I am. Going through all the terror. Trying to free myself (and the world) of this culture.

I carry a trauma with me from reading Derrick Jensen‘s Endgame.

And I carry a deep trauma with me from seeing that he is right, from seeing my fellow beings and relatives disappear, the insects, the birds, the amphibians, all of my beloved nature, in rapid decline.

I most certainly carry a lot of trauma with me from my parents and grandparents, since I was born only 34 years after World War II. I certainly carry a trauma from watching all the documentaries and from visiting the concentration camp in Dachau.

You do not understand my language. I can say what I want, but you don‘t understand. You do not even understand the language “stroke” (red alert; Individual doesn’t function anymore within this insane culture).

Government to medical complex: Repair individual and re-integrate into the machine.

Sorry, doesn’t work for me. I’m out.

I need a lot of quiet and peaceful time to deal with all the trauma. I can’t just rush through my life and work ever harder to help to accomplish the neoliberal agenda and make Europe more competitive for the global economy (that’s how the politicians sold it to us; in fact, the rich are getting richer and the poor poorer, as always).

Mental illnesses such as depression or burnout are the expression of a deep crisis of freedom. They are a pathological sign that today freedom often turns into coercion. We think we are free today. But in reality we exploit ourselves passionately until we collapse…Neoliberalism is even capable of exploiting freedom itself. The performance society creates more productivity than the disciplinary society, because it makes excessive use of freedom. It doesn’t exploit against freedom, but it exploits freedom itself. Everything that belongs to practices and expressions of freedom, such as emotion, play and communication, is now exploited. It is not efficient to exploit someone against his or her will. With the external exploitation, the yield is very small. Only self-exploitation, as the exploitation of freedom, produces the greatest yield. The first stage of burnout syndrome is, paradoxically, euphoria. Euphorically I plunge into the work. In the end I collapse and slide into depression.

—Byung-Chul Han

What will you do when the next economic collapse hits?

What will you do when you loose your job and can‘t numb yourself anymore with your work?

Alcohol, drugs, suicide?

Better to face the truth, go through all the terror, declare your loyalty to justice and life on planet earth and become a revolutionary.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Run for Sacred Water

[Story] by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Last week, I was invited to join a Sacred Water Run-Walk in Nevada by Chief Johnnie Bobb of the Western Shoshone National Council. Chief Bobb attended the Sacred Water, Sacred Forests gathering back in May, and we exchanged contact information.

I decided to attend last minute after his phone call, and gathered my supplies and energies. It is a 14 hour drive from my home in Oregon to the area the walk was to take place, so I took two days to make the drive. I stopped along the way and purchased as much food and supplies as I could afford, although I didn’t know exactly what was needed.

I slept on the night of October 1st in my car at the Swamp Cedars, where we were supposed to meet. The Swamp Cedars are an ecologically unique stand of Rocky Mountain Junipers on the bottom of Spring Valley. Pure water coming out of the ground, shade from the trees, and rich grasses that brought in game animals made this area a gathering place for Newé (Western Shoshone/Goshute) people for thousands of years. It is also why the people were gathered here when they were massacred by the U.S. Calvary, one of several massacres here.

I was awoken before the dawn the next morning when Rupert Steele, the chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, pulled in next to me. We spoke for a while, and then others started to arrive. The others included about 15 or 20 other people from 12 different indigenous nations.

Mr. Steele and Chief Johnnie Bobb both said prayers and burned sage as the sun rose over Spring Valley. I introduced myself to various people, including the woman who organized the run (Beverly Harry). I told her about the food, which she was happy about. Then the runners started out. I stuck around for a while and made some coffee for the elders. One of them asked me to join them in the run-walk, a great honor. I ended up doing 10 miles that day. We did it relay style, so at least one person from the group ran or walked every mile.

We covered 100 miles that first day, then stayed at Cathedral Gorge State Park. We had a nice night around the fire and got to know each other a bit better. I was able to stay through the second day. We covered another 75 miles the second day, and then I had to leave. The runners continued down to the Moapa Paiute reservation.

Our network against the water grab is growing. There were some solid people there. In the event SNWA begins to build the pipeline, there will be serious resistance.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Oppression and Subordination

[Story] by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance.

At this moment, the liberal basis of most progressive movements is impeding our ability, individually and collectively, to take action. The individualism of liberalism, and of American society generally, renders too many of us unable to think clearly about our dire situation. Individual action is not an effective response to power because human society is political; by definition it is built from groups, not from individuals. That is not to say that individual acts of physical and intellectual courage can’t spearhead movements. But Rosa Parks didn’t end segregation on the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system. Rosa Parks plus the stalwart determination and strategic savvy of the entire black community did.

Liberalism also diverges from a radical analysis on the question of the nature of social reality. Liberalism is idealist. This is the belief that reality is a mental activity. Oppression, therefore, consists of attitudes and ideas, and social change happens through rational argument and education. Materialism, in contrast, is the understanding that society is organized by concrete systems of power, not by thoughts and ideas, and that the solution to oppression is to take those systems apart brick by brick. This in no way implies that individuals are exempt from examining their privilege and behaving honorably. It does mean that antiracism workshops will never end racism: only political struggle to rearrange the fundamentals of power will.

There are three other key differences between liberals and radicals. Because liberalism erases power, it can only explain the subordinate position of oppressed groups through biology or some other claim to naturalism. A radical analysis of race understands that differences in skin tone are a continuum, not a distinction: race as biology doesn’t exist. Writes Audrey Smedley in Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview,

Race originated as the imposition of an arbitrary value system on the facts of biological (phenotypic) variations in the human species.… The meanings had social value but no intrinsic relationship to the biological diversity itself. Race … was fabricated as an existential reality out of a combination of recognizable physical differences and some incontrovertible social facts: the conquest of indigenous peoples, their domination and exploitation, and the importation of a vulnerable and controllable population from Africa to service the insatiable greed of some European entrepreneurs. The physical differences were a major tool by which the dominant whites constructed and maintained social barriers and economic inequalities; that is, they consciously sought to create social stratification based on these visible differences.3

Her point is that race is about power, not physical differences. Racializing ideology was a tool of the English against the Irish and the Nazis against the Jews, groups that could not be distinguished by phenotypic differences—indeed, that was why the Jews were forced to wear yellow stars.

Conservatives actively embrace biological explanations for race and gender oppression. White liberals usually know better than to claim that people of color are naturally inferior, but without the systematic analysis of radicalism, they are stuck with vaguely uncomfortable notions that people of color are just … different, a difference that is often fetishized or sexualized, or that results in patronizing attitudes.

Gender is probably the ultimate example of power disguised as biology. There are sociobiological explanations for everything from male spending patterns to rape, all based on the idea that differences between men and women are biological, not, as radicals believe, socially created. This naturalizing of political categories makes them almost impossible to question; there’s no point in challenging nature or four million years of evolution. It’s as useless as confronting God, the right-wing bulwark of misogyny and social stratification.

The primary purpose of all this rationalization is to try to remove power from the equation. If God ordained slavery or rape, then this is what shall happen. Victimization becomes naturalized. When these forms of “naturalization” are shown to be self-serving rationalizations the fall-back position is often that the victimization somehow is a benefit to the victims. Today, many of capitalism’s most vocal defenders argue that indigenous people and subsistence farmers want to “develop” (oddly enough, at the point of a gun); many men argue that women “want it” (oddly enough, at the point of a gun); foresters argue that forests (who existed on their own for thousands of years) benefit from their management.

With power removed from the equation, victimization looks voluntary, which erases the fact that it is, in fact, social subordination. What liberals don’t understand is that 90 percent of oppression is consensual. As Florynce Kennedy wrote, “There can be no really pervasive system of oppression … without the consent of the oppressed.”4 This does not mean that it is our fault, that the system will crumble if we withdraw consent, or that the oppressed are responsible for their oppression. All it means is that the powerful—capitalists, white supremacists, colonialists, masculinists—can’t stand over vast numbers of people twenty-four hours a day with guns. Luckily for them and depressingly for the rest of us, they don’t have to.

People withstand oppression using three psychological methods: denial, accommodation, and consent. Anyone on the receiving end of domination learns early in life to stay in line or risk the consequences. Those consequences only have to be applied once in a while to be effective: the traumatized psyche will then police itself. In the battered women’s movement, it’s generally acknowledged that one beating a year will keep a woman down.

While liberals consider it an insult to be identified with a class or group, they further believe that such an identity renders one a victim. I realize that identity is a complex experience. It’s certainly possible to claim membership in an oppressed group but still hold a liberal perspective on one’s experience. This was brought home to me while I was stuck watching television in a doctor’s waiting room. The show was (supposedly) a comedy about people working in an office. One of the black characters found out that he might have been hired because of an affirmative action policy. He was so depressed and humiliated that he quit. Then the female manager found out that she also might have been ultimately advanced to her position because of affirmative action. She collapsed into depression as well. The emotional narrative was almost impossible for me to follow. Considering what men of color and all women are up against—violence, poverty, daily social derision—affirmative action is the least this society can do to rectify systematic injustice. But the fact that these middle-class professionals got where they were because of the successful strategy of social justice movements was self-evidently understood broadly by the audience to be an insult, rather than an instance of both individual and movement success.

Note that within this liberal mind-set it’s not the actual material conditions that victimize—it’s naming those unjust conditions in an attempt to do something about them that brings the charge of victimization. But radicals are not the victimizers. We are the people who believe that unjust systems can change—that the oppressed can have real agency and fight to gain control of the material conditions of their lives. We don’t accept versions of God or nature that defend our domination, and we insist on naming the man behind the curtain, on analyzing who is doing what to whom as the first step to resistance.

The final difference between liberals and radicals is in their approaches to justice. Since power is rendered invisible in the liberal schema, justice is served by adhering to abstract principles. For instance, in the United States, First Amendment absolutism means that hate groups can actively recruit and organize since hate speech is perfectly legal. The principle of free speech outweighs the material reality of what hate groups do to real human people.

For the radicals, justice cannot be blind; concrete conditions must be recognized and addressed for anything to change. Domination will only be dismantled by taking away the rights of the powerful and redistributing social power to the rest of us. People sometimes say that we will know feminism has done its job when half the CEOs are women. That’s not feminism; to quote Catharine MacKinnon, it’s liberalism applied to women. Feminism will have won not when a few women get an equal piece of the oppression pie, served up in our sisters’ sweat, but when all dominating hierarchies—including economic ones—are dismantled.

There is no better definition of oppression than Marilyn Frye’s, from her book The Politics of Reality. She writes, “Oppression is a system of interrelated barriers and forces which reduce, immobilize and mold people who belong to a certain group, and effect their subordination to another group.”5 This is radicalism in one elegant sentence. Oppression is not an attitude, it’s about systems of power. One of the harms of subordination is that it creates not only injustice, exploitation, and abuse, but also consent.

Subordination has also been defined for us. Andrea Dworkin lists its four elements:6

- Hierarchy

Hierarchy means there is “a group on top and a group on the bottom.” The “bottom” group has fewer rights, fewer resources, and is “held to be inferior.”7

- Objectification

“Objectification occurs when a human being, through social means, is made less than human, turned into a thing or commodity, bought and sold … those who can be used as if they are not fully human are no longer fully human in social terms.”8

- Submission

“In a condition of inferiority and objectification, submission is usually essential for survival … The submission forced on inferior, objectified groups precisely by hierarchy and objectification is taken to be the proof of inherent inferiority and subhuman capacities.”9

- Violence

Committed by members of the group on top, violence is “systematic, endemic enough to be unremarkable and normative, usually taken as an implicit right of the one committing the violence.”10

All four of these elements work together to create an almost hermetically sealed world, psychologically and politically, where oppression is as normal and necessary as air. Any show of resistance is met with a continuum that starts with derision and ends in violent force. Yet resistance happens, somehow. Despite everything, people will insist on their humanity.

Coming to a political consciousness is not a painless task. To overcome denial means facing the everyday, normative cruelty of a whole society, a society made up of millions of people who are participating in that cruelty, and if not directly, then as bystanders with benefits. A friend of mine who grew up in extreme poverty recalled becoming politicized during her first year in college, a year of anguish over the simple fact that “there were rich people and there were poor people, and there was a relationship between the two.” You may have to face full-on the painful experiences you denied in order to survive, and even the humiliation of your own collusion. But knowledge of oppression starts from the bedrock that subordination is wrong and resistance is possible. The acquired skill of analysis can be psychologically and even spiritually freeing.

Once some understanding of oppression is gained, most people are called to action.

Read more from the Deep Green Resistance book online.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Guiding Principles of Deep Green Resistance

[Link] Statement of Principles

The soil, the air, the water, the climate, and the food we eat are created by complex communities of living creatures. The needs of those living communities are primary; individual and social morality must emerge from a humble relationship with the web of life.

Civilization, especially industrial civilization, is fundamentally destructive to life on earth. Our task is to create a life-centered resistance movement that will dismantle industrial civilization by any means necessary. Organized political resistance is the only hope for our planet.

Deep Green Resistance works to end abuse at the personal, organizational, and cultural levels. We also strive to eradicate domination and subordination from our private lives and sexual practices. Deep Green Resistance aligns itself with feminists and others who seek to eradicate all social domination and to promote solidarity between oppressed peoples.

When civilization ends, the living world will rejoice. We must be biophilic people in order to survive. Those of us who have forgotten how must learn again to live with the land and air and water and creatures around us in communities built on respect and thanksgiving. We welcome this future.

Deep Green Resistance is a radical feminist organization. Men as a class are waging a war against women. Rape, battering, incest, prostitution, pornography, poverty, and gynocide are both the main weapons in this war and the conditions that create the sex-class women. Gender is not natural, not a choice, and not a feeling: it is the structure of women’s oppression. Attempts to create more “choices” within the sex-caste system only serve to reinforce the brutal realities of male power. As radicals, we intend to dismantle gender and the entire system of patriarchy which it embodies. The freedom of women as a class cannot be separated from the resistance to the dominant culture as a whole.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Evaluating Strategy

[Link] Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

Resistance is not one-sided. For any strategy resisters can come up with, those in power will do whatever they can to disrupt and undermine it. Any strategic process—for either side—will change the context of the strategy. A strategic objective is a moving target, and there is an intrinsic delay in implementing any strategy. The way to hit a moving target is by “leading” it—by looking slightly ahead of the target. Don’t aim for where the target is; aim for where it’s going to be.

Too often we as activists of whatever stripe don’t do this. We often follow the target, and end up missing badly. This is especially clear when dealing with issues of global ecology, which often involve tremendous lag time. We’re worried about the global warming that’s happening now, but to avert current climate change, we should have acted thirty years ago. Mainstream environmentalism in particular is decades behind the target, and the movement’s priorities show it. The most serious mainstream environmental efforts are for tiny changes that don’t reflect the seriousness of our current situation, let alone the situation thirty years from now. They’ve got us worried about hybrid cars and changing lightbulbs, when we should be trying to head off runaway global warming, cascading ecological collapses, the creation of hundreds of millions of ecological refugees or billions of human casualties, and the social justice disasters that accompany such phenomena. If we can’t avert global ecological collapse, then centuries of social justice gains will go down the toilet.