by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 22, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

Trump’s election has sabotaged any prospect of reigning in the global warming crisis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

On Tuesday night, the American people decided to elect Donald J. Trump, a billionaire business mogul and reality TV star who has been accused of raping or otherwise sexually assaulting twenty-three women, who has called for banning immigration to the United States, and who has built a campaign on virulent racism.

He received more than 60 million votes.

There is a lot to process. Those conversations, about the growing tide of white supremacy, about Trump’s pending sexual assault cases, about the fact that Hillary Clinton won the popular vote, about the left’s failure to engage with the white community on issues of race, and about the gerrymandering and voter disenfranchisement that characterizes the American system, are already taking place.

I want to focus here on one specific issue: global warming. As I’m writing this, I’m sitting in the sun outside my home. It’s November, and temperatures are more than 20 degrees above the typical average here. This year, 2016, is predicted to be the hottest year on record, beating out last year, which beat out the previous year, which beat out the previous year, each of the last five setting a new mark.

Records are being smashed aside like bowling pins. We are in the midst of a global catastrophe, and it is even worse than previously thought. On the day after the election, news broke that the climate is more sensitive to global warming than most calculations had suspected.

The study in question predicted nearly double the warming that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had previously expected. The new data predicts between 9 and 14 °F warming by 2100, enough to potentially lead to the extinction of the human species and flip the Earth into a completely new regime more similar to Venus than Earth. Michael Mann, one of the most well-known climate scientists in the world, says these findings and the changing political situation may mean “game over for the climate.”

Into this mess strides Donald Trump, who has said that if elected, he would “immediately approve” the Keystone XL pipeline, roll back environmental regulations, further subsidize the fossil fuel industry, and back out of the Paris climate agreement. Coal and oil stocks, as well as shares of equipment companies and railroads, jumped in price after news of his victory hit.

Right now, thousands of native people and allies are gathering on the cold plains of North Dakota in an attempt to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. Under President Obama, such popular movements had a chance—a small chance, but a chance—of success. Under Trump, there won’t be so much leniency, and the road to victory will be much harder.

Right now, thousands of native people and allies are gathering on the cold plains of North Dakota in an attempt to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. Under President Obama, such popular movements had a chance—a small chance, but a chance—of success. Under Trump, there won’t be so much leniency, and the road to victory will be much harder.

History is clear; social movements have generally flourished under slightly more progressive administrations, and waned under right wing leadership. What does this mean for our strategy?

I would like to have a peaceful transition to a sane and sustainable world, but it seems increasingly impossible. The American people have shown themselves to be a reactionary force, clinging to their privilege as if it can shield them against the arrows that originate in American foreign policy. Immigrants come here because their lands have been destroyed for American capitalism, and groups like ISIS have emerged from a slurry of war, oil, racism, and fundamentalism.

Perhaps, then, we need a different type of change. When it comes to protecting the planet, stopping pipelines needs to be one of our first priorities. And like other Earth-destroying machinery, pipelines are very vulnerable. They stretch on for miles with no guards, no fences, and no protection.

Recently, a number of activists, including some who I know, were able to approach and shut down all five pipelines that carry tar sands oil into the United States in a coordinated act of non-violent civil disobedience. Their action was brave, but its long-term efficacy depends on whether courts will agree with them that their action was necessary and create a precedent to normalize actions of this type. With another Antonin Scalia on the way to the Supreme Court, a positive outcome is in doubt.

Coordinated action of another type could be more effective in protecting the planet. In plain language, I speak of sabotage. Individuals or networks of people conducting coordinated, small-scale sabotage over a widespread area could cripple the fossil fuel system with a minimum of expense, technical expertise, personnel, and risk. It is simple to disappear into the night, and with proper security culture the possibility of capture is remote. We’ve seen how vulnerable this network is; anyone could do this.

Coordinated action of another type could be more effective in protecting the planet. In plain language, I speak of sabotage. Individuals or networks of people conducting coordinated, small-scale sabotage over a widespread area could cripple the fossil fuel system with a minimum of expense, technical expertise, personnel, and risk. It is simple to disappear into the night, and with proper security culture the possibility of capture is remote. We’ve seen how vulnerable this network is; anyone could do this.

It isn’t idle speculation that such attacks would have a substantial impact. Its actually been done before, most notably in Nigeria, where indigenous people in the Niger River Delta have risen against polluting oil companies many times over the past several decades. Most recently, attacks on oil pipelines earlier this year shut down some 40 percent of Nigeria’s oil processing. Months later, the oil industry still hasn’t recovered.

To many people, this plan will sound insane. Modern life is dependent upon oil in so many ways. But when oil is killing the planet and those in power will not respond to rational argumentation or peaceful protest, and when sixty million people are willing to vote a climate-denying sexual abuser into office, what options are we left with? It is time for serious escalation.

Max Wilbert is a writer, activist, and organizer with the group Deep Green Resistance. He lives on occupied Kalapuya Territory in Oregon.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 19, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Via Deep Green Resistance UK

2016 is predicted to be the hottest year since records began and environmental devastation is increasing. With so little time left and the whole world at stake, are the radical changes to halt climate change and ecocide being made? The simple answer is no, based on species extinction and the continuing global extraction and burning of fossil fuels.

Resistance movements need to be strategic to be effective. This involves selecting appropriate tactics to use and if a tactic is not effective, then choosing another. Nonviolent direct action (NVDA) is important to our struggle to stop environmental destruction, but it is only one tactic. I have found discussions about the appropriate uses of nonviolence, force, and violence unclear and often confusing, which led me to research the topic in greater depth.

Within activist communities and broader society, there are two widely-held perspectives on nonviolence. Some choose NVDA for strategic reasons. They may also see the importance of using force in some situations, if appropriate, but may or may not ever use force themselves. There are also those people who oppose the use of force no matter the circumstances. Any criticism in my articles is directed at the latter perspective as those who hold this perspective routinely mandate nonviolence across whole movements, and categorically reject the use of force or militant resistance, even in self defense. I will refer to people from this perspective as “nonviolence fundamentalists.”

In future articles I will explore what thinkers of the last 150 years have about these ideas, starting with violence. For now I will list those on either side of the debate that I have studied. There are of course others.

Nonviolence fundamentalists include:

Those that support NVDA and the use of force/militant resistance include:

I would also add that most of the people that have written about violence, nonviolence, the use of force or militant resistance are men. I extensively researched women’s contribution to these topics and included everything relevant, without shoehorning them in to appear right on. Women have been very active in struggles using force and nonviolence tactics but it is mainly men that have written about it. This is consistent with men’s dominance in most areas of life. If I have overlooked anyone, I apologise and do set me straight. Some of the amazing women that have been so important to past struggles include Harriet Tubman, Blanca Canales, Angela Davis, Kathleen Neal Cleaver, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Ulrike Meinhof, Ida Wells-Barnett, and Sojourner Truth.

Featured image: Nonviolent Direct Action at Livermore Lab, byJames Heddle/EON

This is the first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 10, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image by Vanessa Vanderburgh

By Joanna Pinkiewicz / Deep Green Resistance Australia

Most people in the industrial civilized world will come to a point of crisis, loosely translated from its Greek origin as: “testing time” or “an emergency event.”

An ongoing feeling of pressure, instability or a threat can all bring on such crisis. These events shake our whole being, alarm our physical bodies and rupture our rational mind. The advice for dealing with a crisis that is perceived as “personal” or “individual” often follows a set of clear, practical steps:

- Slow your breath to anchor yourself in the present

- Take a note of your emotions or bodily sensations

- Open up and express your thoughts

- Pursue a valued course of action

The last step is particularly interesting, as it suggests questioning: What do I value the most? What do I stand for? How do I want to see myself respond?

As much as a crisis brings many negatives, such as anxiety and depression, it also brings an opportunity to re-examine our lives and expand our understanding of what is happening in the world or to the world around us. It forces us to examine and to make a choice: are we going to be a bystander or are we going to become courageous in the face of a looming threat?

Research on the psychology of resistance suggests, that access to support and the right type of information is crucial to help those wanting to understand what is really happening to us and the world, as well as, what can be done to address it.

The authors of Courageous Resistance, The Power of Ordinary People list certain factors that contribute to ordinary people becoming resisters in the face of injustice or impending threat. These include a combination of:

- Preconditions: previous attitudes, experiences and internal resources

- Networks: ongoing relationships with people that offered information, resources and assistance and

- The Context itself: political climate, severity of the situation

We understand courageous resistance to be a conscious process of decision making, which is affected not only by who the decision maker is, but where they are and who they know at the particular time they become aware of a grave injustice…

We define “courageous resisters” along three dimensions: First, they are those who voluntarily engage in other-oriented, largely selfless behaviour with significantly high risk or cost to themselves or their associates. Second, their actions are the result of a conscious decision. Third, their efforts are sustained over time. [i]

Humanity today faces ongoing stress from living in the civilized world. By and large, we have managed to adapt to changes that have been imposed on us, such as higher density living and working conditions. However the escalated threat of armed violence and impending effects of climate change bring on new types of crises, which needs not only immediate response, but creation of a completely new culture. The current culture likes us to believe that the crises we are experiencing are “individual,” due to a weakness or an illness. If we choose to believe this, we are more likely to suffer from helplessness and not participate in creating this new culture.

Aric McBay explains this in Deep Green Resistance, Strategy To Save The Planet:

If someone is dissatisfied with the way society works, they say, then it is that individual’s personal emotional problem. Furthermore, the individual traumas perpetuated by those in power on individual people, on groups of people, and on the land, can seem random at first glance. But if we can trace them back to their common roots—in capitalism, in patriarchy, in civilization at large—then we can understand them as manifestations of power imbalance, and we can overcome the learned helplessness…[ii]

To begin to create a culture of resistance individuals must drop loyalty to the oppressive status quo and its systems. Two things may prevent us from fully committing to resistance: fear of punishment or separation from our kin (friends, family). While loss of “belief” in “redeeming” the existing culture is a first step towards resistance, separation from dependency on the existing systems is gradual.

As building an effective resistance culture is a long process involving generations, we must be wise at preserving our health and using our resources.

Listed below are steps that effective groups or communities follow in response to a crisis that is not personal, but wide spread and caused by either natural (earthquake, flood) or man-made circumstances (occupation, oppression, ecocide).

- Prepare: clarify our values, recruit people, gather resources, and devise the strategy

- Respond: assign roles and responsibilities, implement strategy

- Recover: extend support networks, rebuild communities, and establish new organizations

Resilience building will come from commitment and co-operation in all of those stages. After the recovery from a crisis, a group gains valuable experience and is able to refine the “emergency” response plan and train newcomers.

Experience of past resisters demonstrates rise in organisational, strategic and physical skills among individuals as well and rise in strength and independence of a group.

I am thankful for my crisis. Like a loud warning siren it told me that things are not right in the world, that I must increase my awareness and prepare for the future.

My crisis led me to discover techniques and practices that reconnected me with my body. I discovered that reconstruction of mental and physical health goes hand in hand with protecting the environment. By recognising the physical and spiritual nourishment we receive from our forests, rivers, oceans, a commitment to environmental action is born.

Taking responsibility was the first step to my healing and the beginning of an authentic life. Such path does not require perfection, but courage and imagination to create new ways of living and existing. To work as a collective in the name of all nature’s communities is a revolutionary path of resistance we desperately need today.

Deep Green Resistance is a global radical environmental organization with a strategy to address our impending planetary crisis. We have recruited capable and experienced individuals to guide and work together in implementing our strategy and fulfill our vision to dismantle the industrial civilization, assist the planet’s recovery and build sustainable communities with decentralized governance.

Join the many existing chapters or start a new one! Become a conscious resister!

Notes:

[i] Thalhammer, Kristina E.; O’Loughlin, Paula L.; Glazer, Myron Peretz; Glazer, Penina Migdal; McFarland, Sam; Shepela, Sharon Toffey; Stoltzfus, Nathan. Courageous Resistance, The Power of Ordinary People. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

[ii] McBay, Aric; Keith, Lierre; and Jensen, Derrick. Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2011.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 27, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Strategy & Analysis

By Zoe Blunt / WildCoast.ca

“I’m in love. With salmon, with trees outside my window, with baby lampreys living in sandy streambottoms, with slender salamanders crawling through the duff. And if you love, you act to defend your beloved.” — Derrick Jensen

Pacific Coast people have always defended the places we love. Most of British Columbia is unceded indigenous land; native peoples have never abandoned, sold, or traded their land away. Many fought fiercely against the power of the British Empire. Cannonballs are sometimes still found embedded in centuries-old trees along the shore – leftovers from the gunboats that tried to suppress indigenous uprisings in the late 1800s.

Nuu-chah-nulth war canoes (Edward Curtis, BC Historical Society)

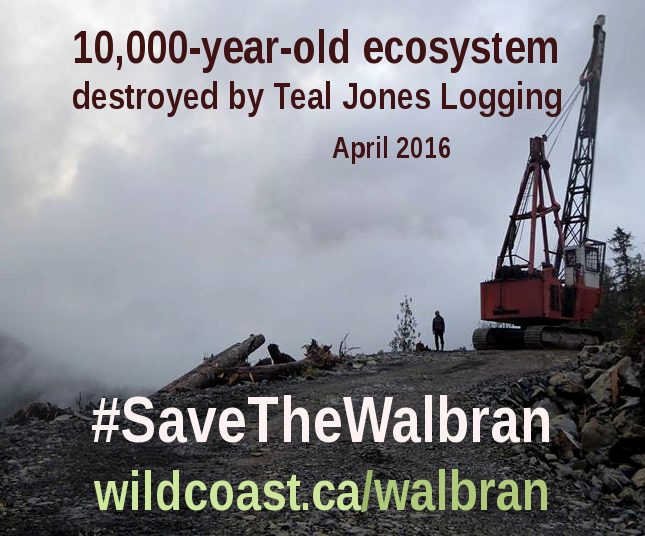

A century later, descendants of the settlers have joined forces to battle corporate raiders. In the 1980s and 1990s, a groundswell of eco-organizing brought thousands of people together to stop clearcut logging in the cathedral forests of Vancouver Island’s Pacific coast, where timber companies were busy converting ten-thousand-year-old ecosystems into barren stumpfields and pulp for paper.

During those years, police arrested hundreds in Clayoquot Sound and the Walbran Valley at mass civil disobedience protests. Young and old alike sat in the middle of the logging roads and linked arms. The resistance went far beyond the peaceful and symbolic: unknown individuals spiked thousands of trees to make the timber dangerous to sawmills. Shadowy figures burned logging bridges and vandalized equipment. The skirmishes went on for over a decade.

Clayoquot Sound, 1993

We won a few battles. Several coastal valleys are protected as parks. But many of them have been logged. And now the logging companies are coming back for the valleys that remain unprotected.

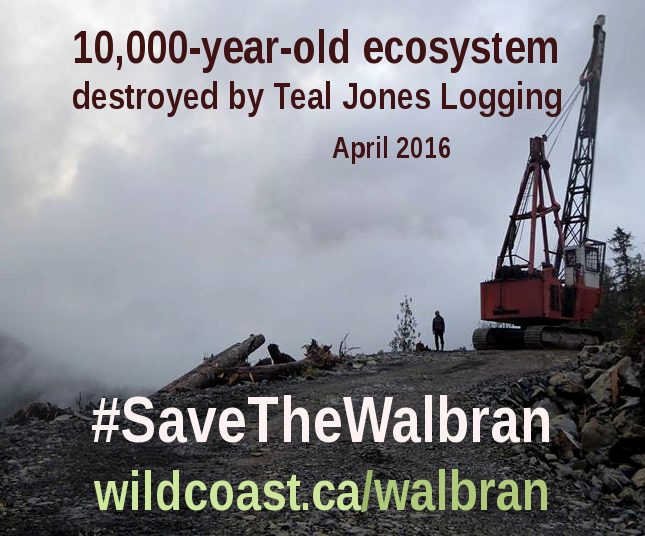

One of the worst corporate offenders is Teal Jones, the company currently bulldozing the majestic Walbran Valley, two hours west of Victoria, BC. They are laying waste to a vibrant rainforest for short-term profit, without the consent of the Pacheedaht First Nation, the Qwa-ba-diwa people, or anyone else outside of government and industry. Teal Jones does not even own the land; it was taken from indigenous people in the name of the BC government sixty years ago.

Pacheedaht territory, Vancouver Island BC

This year, the elected leadership of the Pacheedaht First Nation threw its support behind building a longhouse in the contested valley, on the land that has sustained them for countless generations. At the same time, locals are pushing back against the logging by occupying roads and logging sites. This in spite of the company’s court order telling police to arrest anyone who blocks their work. Forest defenders are regrouping, but the destruction continues.

Women for the Walbran and Forest Action Network are ramping up to break the deadlock. We’re hosting direct action trainings to share skills and develop strategies for defending ecosystems. The agenda includes tactics like non-violent civil disobedience, occupying tree-tops, and backcountry stealth. We’ll have info on legal rights, indigenous solidarity, and more.

Tree-sit occupation, Langford BC. (Photo: Ingmar Lee)

Our adversary, Teal Jones, is a relatively small company. Its owners are relying on the police to protect their “right” to strip public forests on Pacheedaht traditional territory. Profit margins are slim, and lawyers are expensive. The forest defenders are poor, but we have community support and a wide array of strategies for beating Teal Jones at its own game. Every tool in the box: we can launch a mass civil disobedience campaign, carry out hit-and-run raids on costly machines, coordinate a knockout legal strategy, or deliver the tried-and-true “death by a thousand cuts” with a combination of tactics.

However it plays out, Teal Jones is on borrowed time in the Walbran. But that’s cold comfort when the machines are mowing down thousand-year-old forests like grass.

Photo: Walbran Central

The forest defenders do have certain advantages. On the practical side, we’re investing in the gear and training that will provide the leverage to win. We have a legal defense fund that’s both a war chest for litigation and a safety net for those who risk their freedom on the front lines. But our best defense is the thousands of people who love this land like life itself. Many live nearby and visit every chance they get, others came once and fell in love, and untold numbers have yet to see the Walbran’s wildlife firsthand, but they hold it in their hearts.

Photo: Walbran Central

Those who love the land are a community. We are the organizers, sponsors, and volunteers who drive this movement forward. Everyone who shares these values can be a part of it; no contribution is too small. We’re going all-out to defend the forests, rivers, bears, cougars, otters, and eagles of the Walbran Valley. They sustain us and we give back by fighting to protect them.

Walbran River, the heart of the Walbran Valley, spring 2016. (Photo: Walbran Central)

Remember: Forest Defenders Are Heroes!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 16, 2016 | Climate Change, Education, Strategy & Analysis

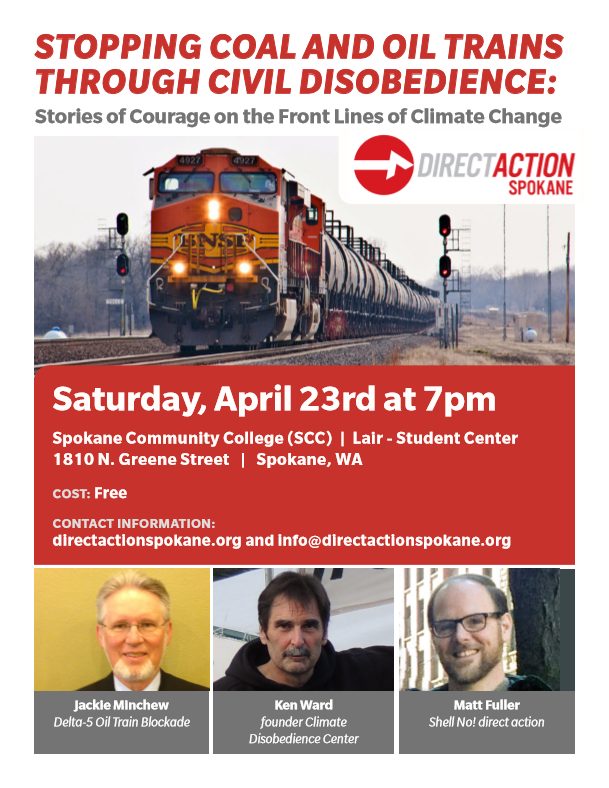

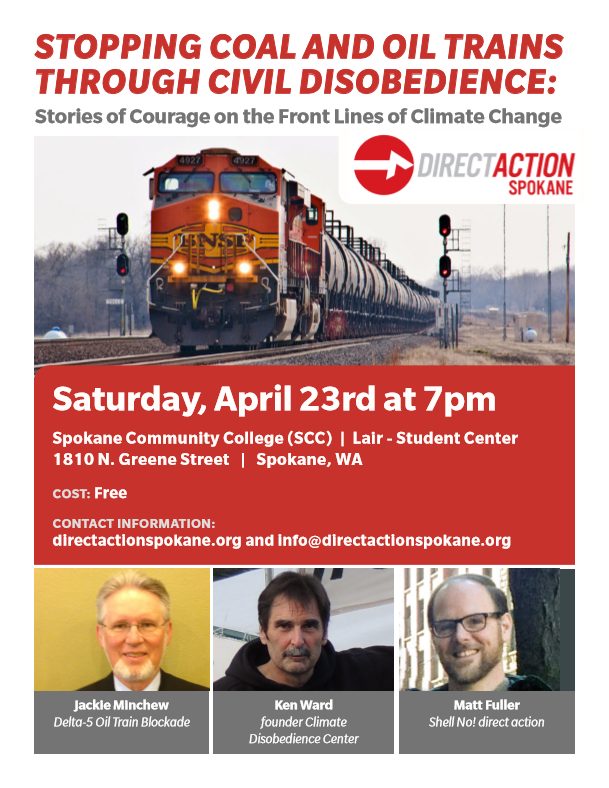

Stopping Coal and Oil Trains Through

Civil Disobedience: Stories of Courage

on the Front Lines of Climate Change

Saturday, April 23rd at 7pm

Spokane Community College – Lair Student Center

Free admission

Featured speakers:

Event host – Direct Action Spokane

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 21, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

By Stephanie McMillan / One Struggle

This essay originally appeared in Idées Nouvelles Idées Prolétariennes. Featured artwork by Stephanie McMillan

Individualism is the ideology of competition, of capitalism. It consists of prioritizing one’s perceived immediate personal interests above collective interests, and being blind to the fact that one’s long-term personal interests actually correspond to the interests of the whole. This leads people to behave in ways that are detrimental to the collective, and ultimately to each individual as well.

Under capitalism, society does not meet the needs of the people, and we are structurally prevented from meeting our needs collectively. Capitalism’s engine is competition. There is competition between classes as well as within classes. Within the working class, the capitalist system pits each person (or family) against all others in a struggle for survival.

Humans are social animals who, before agriculture arose and society was divided into classes, lived in bands. Our species evolved with a natural tendency to cooperate. But when people living under capitalism attempt to express this tendency, they are sharply discouraged. For example, when strangers spontaneously assist one another after a disaster, they are quickly dispersed and ordered to leave this task to the state.

The capitalist class holds ideological hegemony (dominance and control) over the whole society. They exert constant pressure to shape our ideas, thoughts, and emotions in ways that serve them. Therefore, unless we make a conscious contrary effort, the ideologies that serve this dominant class are spontaneously felt as “normal” or “natural.”

Individualism is a powerful ideological weapon that the capitalist class (the bourgeoisie) uses to crush the subjectivity of the working class (the proletariat), and thus to prevent the potential liberation of the world from capitalist rule. Individualism is promoted and fortified by every possible cultural and economic means. We are indoctrinated from birth. Parents are compelled to teach their children to survive in the competitive framework (which they have no choice about living in) by “getting ahead,” to “look out for number one,” to put oneself in the best position possible (i.e., through education, or seeking a rich mate) to accumulate wealth for personal security.

Individualism is the ideology of the petit bourgeoisie (those who circulate capital by selling either services or goods, who tend to aspire to belong to the ruling class). It manifests itself as the striving for market power, for personal advancement, for comforts, for security and stability within the framework of the system. In contrast, proletarian ideology seeks to overturn the capitalist system and meet our needs collectively. But capitalism has been able to indoctrinate even members of the working class in petit bourgeois ways of thinking, to manipulate them into acting against their own interests, in ways that benefit capitalists instead.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

As proletarian militants, we are no less subject to ideological domination than anyone else. The difference is that we are consciously aware of it, to varying degrees, and thus we are able to combat it. In order to fight the system, we must fight its dominant ideologies at every level: in society as a whole, in our organizations, and in our own individual hearts and minds.

This is an active and constant process of struggle. It will continue even after the ruling class has been defeated politically— we are so deeply conditioned that it may take generations to uproot their poisonous ideas. Ultimately, it will require that we construct a society (an economy, in particular) that retains no structural or social mechanism for rewarding individualism.

We should not be ashamed to discover individualism in our own hearts, or shame others for manifesting it— it is inevitable in capitalist society. Instead, the way to fight it is to bring it to light, examine it in relation to our overall political goals, and then consciously reject it (over and over again, as it will constantly re-arise).

Ideological strength requires an underpinning of political unity; these advance together. The motive for struggle on the ideological front is not to serve some abstract morality, but to achieve a specific political goal.

Individualism is not the same as individuality. Combatting individualism does not mean that everyone must be identical (which is impossible anyway) or that anyone should suppress their own thoughts, desires, or particular characteristics. On the contrary, we must recognize the value of each individual as inherent, and at the same time as it relates to the collective. Each person has specific strengths to contribute to our common work, and these should be enhanced and supported. Our weaknesses should be shared so we can help each other overcome them. We appreciate diversity and differences among us, which contribute to a dynamic social/political life, increasing our range of possibilities in action and thought. (In fact, for any motion to occur at all, in a dialectical process, differences are required, by definition). In groups, as in any aspect of the natural world, diversity ensures resilience, flexibility, adaptability, and evolution.

In order to struggle against individualism, we must recognize its manifestations. In political organizations, there are many ways that this destructive ideology materializes. They include (not exclusively) these 12 common types:

1) Misplaced priorities. Nothing is as important and urgent as crushing capitalism. Nothing. Countless lives will continue to be destroyed until we accomplish this task. The future existence of all life on Earth is at risk as long as this system exists. Everything we do should be, in some way, in service to our cause. Of course our basic needs must be met, which beyond self-reproduction (subsisting) also include maintaining one’s health and balance (mental, emotional, physical, social and cultural). These should support and renew our capacity to contribute to revolution. Even if we eliminate frivolous activities from our lives, we still have to make difficult choices about how we spend our time, because the system keeps us very busy in our effort to survive and meet our responsibilities. (This overload is intentionally devised so we are too overwhelmed to resist). Therefore we have to constantly evaluate how much energy we give to particular activities, make correct choices even when they are painful, and order our lives in favor of the revolutionary struggle.

2) Competition among ourselves. This can involve using one’s experience, knowledge, accomplishments, abilities or personality to gain personal power or prestige, and to repress the collective will. Instead, we should all strive to strengthen our collective democratic functioning by assisting each comrade to express her/himself, to overcome weaknesses, build strength, and maximize participation. We should struggle among ourselves within a framework of overall unity, in order to discover the truth together, and not attempt to impose one’s own will over others (whether their disagreements are verbalized or silent), or monopolize any aspect of work. Individual power without collective power is useless and can never defeat our enemy.

3) A lack of commitment. In order to increase consumption of commodities, capitalist society obsessively pushes self-indulgence as an ideal. (“Because you’re worth it.”) It has created concepts of “comfort,” “fun” and “satisfaction” that correspond to their economic need for us to buy things. Whatever doesn’t please us in the moment, we are encouraged to abandon and replace. This leads to a market-based approach to life, including toward nature, love, spirituality, political work, and everything else. Unfortunately, political work is not comfortable, fun, and instantly gratifying in the ways that we are conditioned to desire. Instead it is challenging, complex, and requires immense persistence. When this fact is discovered, a common response is to abandon it.

4) Laziness. Some people believe they’ve performed a great deed by joining an organization and declaring support for the cause. They stop here, congratulating themselves and posting revolutionary quotations all over Facebook. But this is like confusing the starting point in a marathon with the finish line. We can’t stand on unearned laurels, but have to run the full distance: to do the hard work of constructing theory, defining a political line, and building organizations—pushing ourselves through to victory and beyond.

5) Passivity. Letting others always take the lead, and refusing to take initiative (once a collective approach has been decided) is an avoidance of responsibility. Each person should strive to participate and contribute to the maximum of her/his potential, to express ideas without fear, and be willing to do whatever work is necessary.

6) Hero/martyr complex. While it’s essential to work to one’s maximum capacity and strive to increase it, it can be tempting to overestimate what one’s capacity actually is. A juggler with too many eggs will drop some of them. Similarly, taking on too many tasks and making too many commitments will result in failure to carry all of them out. Unreliability leads to uncertainty and paralysis for the other members of an organization, who have interconnected tasks that depend on one another for success. In addition, it could cause the person to burn out, rendering them totally ineffective. Instead of attempting personally to handle every task, we should help others share responsibilities. We have to accept that some tasks will not be accomplished (as well or at all) until sufficient collective capacity is built.

7) Defensive/aggressive ego. In a collective endeavor, criticism should never be personal; thus there is no reason to be personally offended by it. We should not only be willing to listen to criticism with an open mind, but to welcome constructive criticism, and learn to evaluate our own work in the spirit of understanding our weaknesses in order to overcome them. Criticism of the work of a comrade or ally should always be offered in a constructive manner, with the intention of assisting their work. An alternative should be suggested along with it. We should not pick each other apart for every small mistake (which can be very demoralizing), but focus on fundamental issues.

8) Self-expression. Intellectuals (especially in academia) attempt to generate novel ideas for professional or “personal branding” purposes, rather than focusing on constructing theory to concretely assist class struggle. This is theory for theory’s sake, or intellectualism. This practice converts theory into just another commodity, a gift to our enemy. The way to combat this is to produce our ideas (in whatever form) collectively. For artists, the concept of “art for art’s sake” is a way to justify creating work without political or social content. This means squandering one’s creativity and skills by offering them for the benefit of the ruling class, instead of for the working class. Intellectuals and artists should participate in other areas of political work, or they won’t fully understand their subjects.

9) Self-esteem. Working hard is good, but not so good if there is an underlying motive of elevating one’s own social position or being the center of attention. We do not need to build our self-esteem by seeking admiration, praise and flattery. Our self-respect and sense of connection should come from being an effective social agent for our class, connected to countless others within a historical process. We should appreciate one another as comrades, and let each other know when we’re doing good work, but not be motivated by a desire for public recognition.

10) Friend sourcing. Because of the atomization of our society, and consequent feelings of isolation, sometimes people join and use organizations as a means to alleviate loneliness, to make friends or develop relationships, whereas it should be the other way around: allowing friendships to arise from a foundation of political unity. If the personal aspect of a relationship is made primary over the political aspect, this can interfere with political functioning. Political agreement or disagreement can be falsely based on emotion. Underlying conflicts can manifest as personal attacks hidden under the guise of political disagreements, picking quarrels, harassment, or avoidance of common work because of discomfort. This creates a negative atmosphere which can sidetrack people’s attention and undermine group cohesion. There is no room for drama in political organizations. We should focus on our overall goal, and be good comrades first, friends second.

11) Liberalism. Tolerating destructive behavior because one doesn’t like conflict or want to “rock the boat,” allows that behavior to continue and increase. Manifestations of liberalism include gossiping behind people’s backs instead of bringing up problems collectively, failing to take opportunities to assert revolutionary ideas in appropriate situations, witnessing (or being subject to) oppressive acts or speech without saying anything, failing to hold comrades accountable, supporting or attacking views based on feelings about the person expressing them, and tolerating mediocrity in our work. These all result in an unprincipled peace that can lead to group apathy.

12) Going off the rails. The members of a revolutionary organization act only within the framework of political unity. Strength comes from disciplined collectivity, and individual initiative must be based on this foundation. Taking action as an individual in ways that have no relationship to collectively agreed-upon strategy or goals can be dangerous. For example, committing an illegal act (impulsively or from a concealed plan) without the knowledge and agreement of the collective, puts others at risk, damages collective work, and destroys mutual trust. Failing to take the safety of the organization seriously and to abide by its security protocols is inexcusable.

Everything in capitalist society is geared to stop us from organizing to fight for revolution. We feel constant pressure to cave in to individualism. We are tempted with possibilities for self-advancement if we abandon the struggle, or are threatened with the opposite if we don’t fall in line. If we insist on rejecting individualism, this can cost us our jobs. Friends may tell us we’re crazy, boring, or depressing to talk to. Our family members might tell us that we are failing in our responsibilities to them when we devote time to political work. On TV and in movies, we are given poisonous models of human behavior.

Resisting all these influences is class struggle on the ideological front. We have to keep our bearings, pick our battles wisely, and refuse to kneel down under pressure. In our organizations, we must assist one another to overcome individualism and all enemy influences.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

Right now, thousands of native people and allies are gathering on the cold plains of North Dakota in an attempt to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. Under President Obama, such popular movements had a chance—a small chance, but a chance—of success. Under Trump, there won’t be so much leniency, and the road to victory will be much harder.

Right now, thousands of native people and allies are gathering on the cold plains of North Dakota in an attempt to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. Under President Obama, such popular movements had a chance—a small chance, but a chance—of success. Under Trump, there won’t be so much leniency, and the road to victory will be much harder. Coordinated action of another type could be more effective in protecting the planet. In plain language, I speak of sabotage. Individuals or networks of people conducting coordinated, small-scale sabotage over a widespread area could cripple the fossil fuel system with a minimum of expense, technical expertise, personnel, and risk. It is simple to disappear into the night, and with proper security culture the possibility of capture is remote. We’ve seen how vulnerable this network is; anyone could do this.

Coordinated action of another type could be more effective in protecting the planet. In plain language, I speak of sabotage. Individuals or networks of people conducting coordinated, small-scale sabotage over a widespread area could cripple the fossil fuel system with a minimum of expense, technical expertise, personnel, and risk. It is simple to disappear into the night, and with proper security culture the possibility of capture is remote. We’ve seen how vulnerable this network is; anyone could do this.