by DGR News Service | Feb 7, 2019 | Movement Building & Support

Resistance News

February 7, 2019

by Max Wilbert

Deep Green Resistance

max@maxwilbert.org

https://www.deepgreenresistance.org

Current atmospheric CO2 level (daily high at Mauna Loa): 411.37 PPM

A free monthly newsletter providing analysis and commentary on ecology, global capitalism, empire, and revolution.

For back issues, to read this issue online, or to subscribe via email or RSS, visit the Resistance News web page.

Most of these essays also appear on the DGR News Service, which also includes an active comment section.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

In this issue:

- Workshops and Training: Bring Deep Green Resistance activists to your community

- Communists call for protection for women’s spaces

- Ecologists rise up to Rojava

- Biko: Some African Cultural Concepts

- Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples Lead Global “Red January” Protests

- Political Education 101

- Implementing Decisive Ecological Warfare

- Why Decisive Dismantling and Warfare?

- Green Technology FAQ

- Submit your material to the Deep Green Resistance News Service

- Further news and recommended reading / podcasts

- How to support DGR or get involved

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

In certain situations, preaching nonviolence can be a kind of violence. Also, it is the kind of terminology that dovetails beautifully with the “human rights” discourse in which, from an exalted position of faux neutrality, politics, morality, and justice can be airbrushed out of the picture, all parties can be declared human rights offenders, and the status quo can be maintained.”

– Arundhati Roy

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Workshops and Training: Bring Deep Green Resistance activists to your community

[Link] Cost: Sliding scale. We generally ask that you cover travel, food, and lodging but may request a stipend for the trainers if your budget allows. We will work with you to make the training affordable. We can also assist with promoting your training.

Content: Our trainings are tailored to your needs. Typical subjects we cover include:

- Grand strategy

- Campaign strategy

- Non-violent direct action tactics: practical skills training (climbing, tripods and other structures, lockboxes, etc.)

- Know your rights, police interactions, and jail support

- Security culture

- Community organizing

- Leadership and decision-making

- Secure communications

- Resistance art

- Liberalism vs. Radicalism

- Intro to Decisive Ecological Warfare (DGR strategy)

Direct Assistance: What if you need help instead of training? Our activists will travel to your location and work with you for up to 10 days on campaign planning, strategy, recruitment, outreach, tactics, etc.

Interested?

Contact Us: training@deepgreenresistance.org

For sensitive info: Contact us securely via PGP. (Download our PGP key here, fingerprint 6DD7 D435 6E52 88FF CB50 ADBF 5DD0 30E2 B1A8 616A)

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Communists call for protection for women’s spaces

[Link] by Morning Star (Communist Party of Britain)

COMMUNISTS called for protection of women’s spaces and preservation of “separate spaces and distinct services to protect women from violence and abuse” today.

The party’s biennial congress said that women’s rights won over decades of struggle were “under sustained ideological attack,” thanks to the “growth and ascendancy of neoliberal philosophy across a range of intellectual fields.”

It adopted a resolution expressing concern at “the divisive debate around self-identification which conflates ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ which could threaten the rights of women and girls” and committed members to fight for a wider understanding of these problems in the labour movement.

Delegates discussed the attacks on women who raised concerns about self-identification and attempts to no-platform or silence them, including attacks on the Morning Star for agreeing to publish articles on the subject.

Mover Mary Davis of the London district said that socialism would be unattainable without “an understanding of the link between women’s oppression and class exploitation.”

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Ecologists rise up for Rojava

[Link] The Mesopotamian Ecology Movement and Make Rojava Green Again call on all ecologists to join the global action days on January 27th and 28th in solidarity with the green revolution in Rojava.

The call was signed by the following organisations and individuals:

Organisations:

- Earth First (UK)

- Extinction Rebellion International

- Institute for Social Ecology (USA)

- Earth Strike

- Symbiotic Horizon (UK)

- Ende Gelände (Germany)

- Hambacher Forst Besetzung (Germany)

- Kurdistan Solidarity Network (UK)

- Hunt Saboteur Association (UK)

- Revolutionärer Aufbau Schweiz (Switzerland)

- Demand Utopia (USA)

- System Change Not Climate Change (Austria)

- Kollektif Solidarité Liège-Rojava (Belgium)

- Deep Green Resistance (USA)

- YXK – Verband der Studierenden aus Kurdistan (Germany)

- Rote Hilfe International

- Rojavakomiteerna (Sweden)

- Red Phoenix Sports Club Dublin (Ireland)

- The Black Throng Orchestra (Sweden)

- Plan C (UK)

- TATORT Kurdistan (Germany)

- Internationaler Kultur- und Solidaritätsverein Regensburg (Germany)

- Interventionistische Linke, Ortsgruppen: Hamburg, Berlin, Rhein-Neckar, Nürnberg (Germany); Linksjugend solid Ortsgruppen Berlin Spandau, Konstanz (Germany)

- Landsforeningen Økologisk Byggeri (Denmark)

- Defend Rojava Köln (Germany)

- Klimakollektivet

- Free the Soil

People:

- Jean Ziegler – Sociologist, Author, Member of the Advisory Committee of the UN Human Rights Council, CH

- Dorian Wallace – Composer, Pianist, US

- David Graeber – anthropologist and activist, US

- Gökay Akbulut – Member of Parliamant DIE LINKE, Germany

- Anja Flach – writer and activist, Germany

- Thomas Schmiedinger – Political Scientist, Austria

- John Parker – Specialist for Arboriculture and Landscape, UK

- Kerem Schamberger – communication scientist, Germany

- Giovanni Russo Spena – Laywer, Italy

- Simon Jacob – Chairman of the Central Council of Oriental Christians, Germany

- Chris Williamson – Member of Parliament Labour Party, UK

- Ismail Küpeli – Historian and Political Scientist, Germany

- Eva Bulling-Schröter – Umweltausschuss DIE LINKE, Bavaria

- Mohammed Elnaiem – Minister of Foreign Affairs in 400+1 black liberation movement, UK

- Dilar Dirik – Kurdish Women Movement and writer, UK

- Tannie Nyboe – Ecologist, Denmark

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Biko: Some African Cultural Concepts

[Link] by Steve Biko

One of the most difficult things to do these days is to talk with authority on anything to do with African Culture. Somehow Africans are not expected to have any deep understanding of their own culture or even of themselves. Other people have become authorities on all aspects of the African life or to be more accurate on Bantu life. Thus we have the thickest of volumes on some of the strangest subjects – even “the feeding habits of the Urban Africans,” a publication by a fairly “liberal” group, Institute of Race Relations.

In my opinion, it is not necessary to talk with Africans about African culture. However, in the light of the above statements one realises that there is so much confusion sown, not only amongst casual non-African readers, but even amongst Africans themselves, that perhaps sincere attempt should be made emphasising the authentic cultural aspects of the African people by Africans themselves.

Since that unfortunate date – 1652 – we have been experiencing a process of acculturation. It is perhaps presumptuous to call it “acculturation” because this term implies a fusion of different cultures.

In our case this fusion has been extremely one-sided. The two major cultures that met and “fused” were the African Culture and the Anglo-Boer Culture.

Whereas the African culture was unsophisticated and simple, the Anglo-Boer culture had all the trappings of a colonialist culture and therefore was heavily equipped for conquest.

Where they could, they conquered by persuasion, using a highly exclusive religion that denounced all other Gods and demanded a strict code of behaviour with respect to clothing, education ritual and custom. Where it was impossible to convert, fire-arms were readily available and used to advantage. Hence the Anglo-Boer culture was the more powerful culture in almost all facets. This is where the African began to lose a grip on himself and his surroundings.

Thus in taking a look at cultural aspects of the African people one inevitably finds himself having to compare. This is primarily because of the contempt that the “superior” culture shows towards the indigenous culture. To justify its exploitative basis, the Anglo Boer culture has at all times been directed at bestowing an inferior status to all cultural aspects of the indigenous people.

I am against the belief that African culture is time-bound, the notion that with the conquest of the African all his culture was obliterated. I am also against the belief that when one talks of African culture one is necessarily talking of the pre-Van Riebeeck culture. Obviously the African has had to sustain severe blows and may have been battered nearly out of shape by the belligerent cultures it collided with, yet in essence even today, one can easily find the fundamental aspects of the pure African culture in the present day African. Hence in taking a look at African culture, I am going to refer as well to what I have termed the modern African culture.

One of the most fundamental aspect of our culture is the importance we attach to Man. Ours has always been a Man-centred society. Westerners have in many occasions been surprised at the capacity we have for talking to each other – not for the sake of arriving at a particular conclusion but merely to enjoy the communication for its own sake. Intimacy is a term not exclusive for particular friends but to a whole group of people who find themselves either through work or through residential requirements.

In fact, in the traditional African culture, there is no such thing as two friends. Conversation groups were more or less naturally boys whose job was to look after cattle periodically meeting at popular spots to engage in conversation about their cattle, girlfriends, parents, heroes, etc. All commonly shared their secrets, joys and woes. No one felt unnecessarily an intruder into someone else’s business. The curiosity manifested was welcome. It came out of a desire to share. This pattern one would find in all age groups. House visiting was always a feature of the elderly folk’s way of life. No reason was needed as a basis for visits. It was always part of our deep concern for each other.

These are things never done in the Westerner’s culture. A visitor to someone’s house, with the exception of friends, is always met with the question “what can I do for you?” This attitude to see people not as themselves but as agents for some particular function either to one’s disadvantage or advantage is foreign to us. We are not a suspicious race. We believe in the inherent goodness of man. We enjoy man for himself. We regard our living together not as an unfortunate mishap warranting endless competition among us but as a deliberate act of God to make us a community of brothers and sisters jointly involved in the quest for a composite answer to the varied problems of life. Hence in all we do we always place Man first and hence all our action is usually jointly community oriented action rather than the individualism which is the hallmark of the capitalist approach. We always refrain from using people as stepping stones. Instead we are prepared to have a much slower progress in an effort to make sure that all of us are marching to the same tune.

Nothing dramatises the eagerness of the African to communicate with each other more than their love for song and rhythm. Music in the African culture features in all emotional states. When we go to work, we share the burdens and pleasures of the work we are doing through music. This particular facet strangely enough has filtered through the present day. Tourists always watch with amazement the synchrony of music and action as African working at a road side use their picks and shovels with well-timed precision to the accompaniment of a background song. Battle songs were a feature of the long march to war in the olden days. Girls and boys never played any games without using music and rhythm as its basis. in other words with Africans, music and rhythm were a not luxuries but part and parcel of our way of communication. Any suffering we experienced was made much more real by song and rhythm. There is no doubt that the so called “Negro spirituals” sung by Black slaves in the States as they toiled under oppression were indicative of their African heritage…

Attitudes of Africans to property again show just how un-individualistic the African is. As everybody here knows, Africans always believe in having many villages with a controllable number of people in each rather than the reverse. This obviously was a requirement to suit the needs of a community-based and man-centred society. Hence most things where jointly owned by the group, for instance there was no such thing as individual land ownership. The land belonged to the people and was under the control of the local chief on behalf of the people. When cattle went to graze it was on an open veld and not on anybody’s specific farm.

Farming and agriculture, though on individualistic family basis, had many characteristics of joint efforts. Each person could by a simple request and holding a special ceremony, invite neighbours to come and work on his plots. This service was returned in kind and no remuneration was ever given.

Poverty was a foreign concept. This could only be really brought about to the entire community by an adverse climate during a particular season. It never was considered repugnant to ask one’s neighbours for help if one was struggling. In almost all instances there was help between individuals, tribe and tribe, chief and chief, etc. even in spite of war.

Another important aspect of the African culture is our mental attitude to problems presented by life in general. Whereas the Westerner is geared to use a problem-solving approach following very trenchant analyses, our approach is that of situation-experiencing. I will quote from Dr. Kaunda to illustrate this point:

“The westerner has an aggressive mentality. When he sees a problem he will not rest until he has formulated some solution to it. He cannot live with contradictory ideas in his mind; he must settle for one or the other or else evolve a third idea in his mind, which harmonises or reconciles the other two. And he is vigorously scientific in rejecting solutions for which there is no basis in logic. He draws a sharp line between the natural and the supernatural, the rational and non-rational, and more often than not, he dismissed the supernatural and non-rational as superstition…

“Africans, being a pre-scientific people do not recognise any conceptual cleavage between the natural and supernatural. They experience a situation rather than face a problem. By this I mean they allow both the rational and non-rational elements to make an impact upon them and any action they may take could be described more as a response of the total personality of the situation than the result of some mental exercise.”

This I find a most apt analysis of the essential difference in the approach to life of these two groups. We as a community are prepared to accept that nature will have its enigmas which are beyond our powers to solve. Many people have interpreted this attitude as lack of initiative and drive yet in spite of my belief in the strong need for scientific experimentation, I cannot help feeling that more time also should be spent in teaching man and man to live together and that perhaps the African personality with its attitude of laying less stress on power and more stress on man is well on the way to solving our confrontation problems.

All people are agreed that Africans are a deeply religious race. In the various forms of worship that one found throughout the Southern part of our continent, there was at least a common basis. We all accepted without any doubt the existence of a God. We had our own community of saints. We believed – and this was consistent with our views of life – that all people who died had a special place next to God. We felt that communication with God, could only be through these people. We never knew anything about hell – we do not believe that God can create people only to punish them eternally after a short period on earth.

Another aspect of religious practices was the occasion of worship. Again we did not believe that religion could be featured as a separate part of our existence on earth. It was manifest in our daily lives. We thanked God through our ancestors before we drank beer, married, worked, etc. we would obviously find it artificial to create special occasions for worship. Neither did we see it logical to have a particular building in which all worship would be conducted. We believed that God was always in communication with us and therefore merited attention everywhere and anywhere.

It was the missionaries who confused our people with their new religion. By some strange logic, they argued that theirs was a scientific religion and ours was mere superstition in spite of the biological discrepancies so obvious in the basis of their religion. They further went on to preach a theology of existence of hell, scaring our fathers and mothers with stories about burning in eternal flames and gnashing of teeth and grinding of bone. The cold cruel religion was strange to us but our fore-fathers were sufficiently scared of the unknown impending anger to believe that it was worth a try. Down went our cultural values!

Yet it is difficult to kill the African heritage. There remains, in spite of the superficial cultural similarities between the detribalised and Westerner, a number of cultural characteristics that mark out the detribalised as an African…

The advent of the Western culture had changed our outlook almost drastically. No more could we run our own affairs. We were required to fit in as people tolerated with great restraint in a western type society. We were tolerated simply because our cheap labour is needed. Hence we are judged in terms of standards we are not responsible for. Whenever colonisation sets in with its dominant culture, it devours the native culture and leaves behind a bastardised culture. This is what has happened to the African culture. It is called a sub-culture purely because the African people in the urban complexes are mimicking the white man rather unashamedly.

In rejecting Western values therefore, we are rejecting those things that are not only foreign to us but that seek to destroy the most cherished of our beliefs – that the coner-stone of society is man himself – not just his welfare. Not his material well being but just man himself with all his ramifications. We reject the power-based society of the Westerner that seems to be ever concerned with perfecting their technological know-how while losing out on their spiritual dimension. We believe that in the long run the special contribution to the world by Africa will be in this field of human relationship. The great powers of the world may have done wonders in giving an industrial and military look, but the greatest gift still has to come from Africa – giving the world a more human face.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

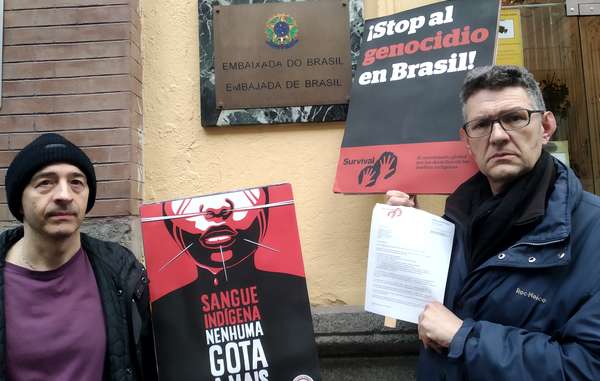

Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples Lead Global “Red January” Protests

[Link] By Survival International

Protests against the anti-indigenous policies of Brazil’s President Bolsonaro are occurring in Brazil and around the world to mark his first month in power.

Demonstrators held placards declaring “Stop Brazil’s genocide now!” and “Bolsonaro: protect indigenous land.”

The protests have been led by APIB, the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, as the culmination of their “Indigenous blood – not a single drop more” campaign, known as “Red January.”

Before he was elected president, Mr Bolsonaro was notorious for his racist views. Among his first acts on assuming power was to remove responsibility for indigenous land demarcation from Brazil’s Indigenous Affairs Department FUNAI, and hand it to the notoriously anti-Indian Agriculture Ministry, which Survival labelled “virtually a declaration of war against Brazil’s tribal peoples.”

President Bolsonaro also moved FUNAI to a new ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights headed by an evangelical preacher, a move designed to drastically weaken FUNAI.

Emboldened by the new President and his long history of anti-indigenous rhetoric, attacks by ranchers and gunmen against Indian communities have risen dramatically.

The territory of the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indians, for example, has been invaded, endangering uncontacted tribespeople there; and hundreds of loggers and colonists are planning to occupy the land of the Awá, one of Earth’s most threatened tribes.

But Brazil’s indigenous people have reacted with defiance. “We’ve been resisting for 519 years. We won’t stop now. We’ll put all our strength together and we’ll win,” said Rosilene Guajajara. And Ninawa Huni Kuin said: “We fight to protect life and land. We will defend our nation.”

APIB said: “We have the right to exist. We won’t retreat. We’ll denounce this government around the world.”

Survival International’s Director Stephen Corry said today: “Having suffered 500 years of genocide and massacres, Brazil’s tribal peoples are not going to be cowed by President Bolsonaro, however abhorrent and outdated his views are. And it’s been inspiring to see how many people around the world are standing with them.”

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Political Education 101

[Link] by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

The idea for this article came to me when I heard a man say at a demonstration that he was confused because he didn’t know if he was “right” or “left”. It therefore seems important to define such seemingly basic political terms as sharply and clearly as possible.

The terms “left” and “right” as political terms have their origins in the French Revolution. At the first French National Assemblies, the traditionally “more honorable” seat to the right of the President of Parliament was reserved for the nobility, so that the bourgeoisie sat on the left. Therefore, those who want more equality are called “left” until today, while those who want to preserve existing power structures are called “right”.

Some definitions:

“By ‘left’ we mean a commitment to social change towards greater equality – political, economic or social. By ‘right’ we mean the support of a more or less hierarchical social order and an opposition to change towards equality”.1

“Right”: who tries to stabilize and preserve the respective centers of power (e.g. monarchy, economic elites) and the structures on which this power is based (e.g. church, colonialism, slavery, corporate capitalism).

“Left”: who advocates the recognition of the equality of all human beings and for a democratic containment of power.2

The French philosopher Geoffroy de Lagasnerie defines “left” as follows: “To define the left, I increasingly rely on a term from Sartre – authenticity. I believe that the point is to be authentic in one’s relationship to the world, to free oneself from all the preconditions that define one’s own situation. One must not bend oneself, one must not gloss over the reality of the world as it is, and that means one cannot do anything other than stand up against this world. To be left basically means not to close one’s eyes to the truth. (…) Pierre Bourdieu has, in my opinion, provided the best definition. He said: To be right means to believe that the problems of the world are that there is no order. So we need more order. The left, on the other hand, is convinced that there is too much order, so it wants more disorder. The left must defend itself against the excess of order, against the ruling systems, against oppression, against persecution, against criminal oppression. It must create disorder, chaos, resistance.”

Ultimately, these definitions can be reduced to two fundamentally different conceptions: “right”: Humans are minors and must be controlled and educated by a ruling power. “left”: Humans are of age and must be as free as possible.

Liberalism:

“Liberalism (Latin liber “free”; liberalis “concerning freedom, liberal”) is a fundamental position of political philosophy and a historical and contemporary movement that strives for a liberal political, economic and social order. Liberalism emerged from the English revolutions of the 17th century.”3

“For the first time in many countries, nation states and democratic systems emerged from liberal citizen movements.“4

Historical liberalism essentially meant the liberation of the bourgeoisie from the rule of the church and aristocracy. In particular, liberalism plays an extremely important role in the emergence of modern capitalism and the history of the United States. Lierre Keith, co-author of the book Deep Green Resistance, explains the history of liberalism in dept in the chapter Liberals and Radicals:

“(…) classical liberalism was the founding ideology of the US, and the values of classical liberalism—for better and for worse—have dispersed around the globe. The ideology of classical liberalism developed against the hegemony of theocracy. The king and church had all the economic, political, and ideological power. In bringing that power down, classic liberalism helped usher in the radical analysis and political movements that followed. But the ideology has limits, both historically and in its contemporary legacy.

“The original founding fathers of the United States were not after a human rights utopia. They were merchant capitalists tired of the restrictions of the old order. The old world had a very clear hierarchy. This basic pattern is replicated in all the places that civilizations have arisen. There’s God (sometimes singular, sometimes plural) at the top, who directly chooses both the king and the religious leaders. These can be one and the same or those functions can be split. Underneath them are the nobles, the priests, and the military. (…) Beneath them are the merchants, traders, and skilled craftsmen. The base of the pyramid contains the bulk of the population: people in slavery, serfdom, or various forms of indenture. And all of this is considered God’s will, which makes resistance that much more difficult psychologically. Standing up to an abuser—whether an individual or a vast system of power—is never easy. Standing up to capital “G” God requires an entirely different level of courage, which may explain why this arrangement appears universally across civilizations and why it is so intransigent.

“In the West, one of the first blows against the Divine Right of Kings was in 1215, when some of the landed aristocracy forced King John to sign Magna Carta. It required the king to renounce some privileges and to respect legal procedures. (…) Magna Carta plunged England into a civil war, the First Baron’s War. (…)

“The American Revolution can be seen as another Baron’s revolt. This time it was the merchant-barons, the rising capitalist class, waging a rebellion against the king and the landed gentry of England. They wanted to take the king and the aristocrats out of the equation, so that the flow of power went God➝property owners. When they said ‘All men are created equal,’ they meant very specifically white men who owned property. That property included black people, white women, and more generally, the huge pool of laborers who were needed to turn this continent from a living landbase into private wealth. (…) Under the rising Protestant ethic, amassing wealth was a sign of God’s favor and God’s grace. God was still operable, he’d just switched allegiance from the old inherited powers to the rising mercantile class.

“Classical liberalism values the sovereignty of the individual, and asserts that economic freedom and property rights are essential to that sovereignty. John Locke, called the Father of Liberalism, made the argument that the individual instead of the community was the foundation of society. He believed that government existed by the consent of the governed, not by divine right. But the reason government is necessary is to defend private property, to keep people from stealing from each other. This idea appealed to the wealthy for an obvious reason: they wanted to keep their wealth. From the perspective of the poor, things look decidedly different. The rich are able to accumulate wealth by taking the labor of the poor and by turning the commons into privately owned commodities; therefore, defending the accumulation of wealth in a system that has no other moral constraints is in effect defending theft, not protecting against it. Classical liberalism from Locke forward has a contradiction at its center. It believes in human sovereignty as a natural or inalienable right, but only against the power of a monarchy or other civic tyranny. By loosening the ethical constraints that had existed on the wealthy, classical liberalism turned the powerless over to the economically powerful, simply swapping the monarchs for the merchant-barons. Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, provided the ethical justification for unbridled capitalism.“

In the meantime, capitalism and the mercantile class have conquered the whole world. Money rules the world, as we all know.

The liberal ideology and its underlying individualism has proven itself as one of the most effective instruments of power, because people who believe that they are free will not resist. “I freed hundreds of slaves. And I would have freed hundreds more if they but known they were slaves,“ said Harriet Tubman.

Yet the first step toward real freedom comes with the radical analysis: “One of the cardinal differences between liberals—those who insist that Everything Will Be Okay—and the truly radical is in their conception of the basic unit of society. This split is a continental divide. Liberals believe that a society is made up of individuals. Individualism is so sacrosanct that, in this view, being identified as a member of a group or class is an insult. But for radicals, society is made up of classes (economic ones in Marx’s original version) or any groups or castes. In the radical’s understanding, being a member of a group is not an affront. Far from it; identifying with a group is the first step toward political consciousness and ultimately effective political action.”

The basic problems today are still essentially the same as in the famous story of Robin Hood, which takes place at the time of the above mentioned Magna Carta: The rich oppress the poor and steal from them. But by now, a huge pile of ideology has been added to justify this oppression and theft.

Neoliberalism:

During the 20th century, liberalism has emerged into neoliberalism, which has been described by Rainer Mausfeld as “the most powerful and sophisticated indoctrination system a political ideology has ever seen”.5

“Neoliberalism, unlike traditional capitalism, is (…) from the beginning consciously twinned with a massive formation of ideology. It was clear to the founding fathers — who came from very different fields — of that what constitutes neoliberal ideology today, that this program is never feasible democratically.

“So they knew — and Hayek explicitly says it — that they have to conquer the language, they have to conquer the brains. Neoliberalism depends on that more than any other ideology. More than any, including communism. One can say in all other things that there is something positive behind it, even though it has been betrayed and might be something completely different now.

“Neoliberalism, ‘take it from below and give it to the top,’ as a gigantic redistribution programme, was from the beginning geared towards extreme formation of ideology. And it is so ingenious and so refined — it goes back to Lippman, Bernays and so on — that they have consciously developed techniques, so that what today is called the neoliberal self is so highly fragmented and actually consists only of false identities. The identity is, ideally, their Facebook account, the smartphone they use, the car they drive, the type of Rolex they wear, the food they eat and so on. Identities have become market products that can be bought. This fragmentation has the advantage that an integral self, which could be a core of resistance, is actually no longer there in a totalitarian structure, because the grown social solidarity no longer exists.

“I am part of a community only through solidarity with others. But if I no longer identify myself with others as a community, but with market products, then solidarity will also be destroyed.

“…neoliberalism has from the beginning actually stressed the importance of [destroying] our psychological resistance to the decomposition of society, which was explicit when Thatcher said “there is no community”. There is only a pile of atomized individuals and their task is to optimize their individual use as best they can. Everyone is a small “Me Inc.” and if someone fails, he/she was just a poor “Me Inc.” -that’s what the market regulates- […] and if someone succeeds, he/she has adapted well to the market. So neoliberalism is a kind of infamous combination and not just an economic program. Neoliberalism is totalitarian in the sense that — Thatcher also said that — […] ‘it’s not just about the economy, it’s about conquering the brains.’

“It is, so to speak, as ideology invisible. Many of us in our society have the feeling: the society in which there is no longer any real ideology — unlike in Russia or China — that’s us. This invisibility of ideology itself is one of the most gigantic achievements of ideology production.”6

At the beginning of the 20th century, the famous catastrophe of the Titanic has already shown us in strong pictures and metaphors how this technocracy will end. In neoliberalism, the upper classes are still dancing, while the lower classes are already drowning. Those on top don’t know (and don’t want to know) how those below are doing.

The ideology rains down from top to bottom:

“The Titanic is unsinkable! Everything is fine! We are all fine! And if you’re not well, it’s your own fault, you just don’t row hard enough.”

They don’t want to see that the whole ship is already sinking.

With the words of Max Wilbert: “We are well along the path towards global fascism, total war, ubiquitous surveillance, normalized patriarchy and racism, a permanent refugee crisis, water and food shortages, and ecological collapse. We need to build legitimate movements to dismantle global capitalism. All work is useful towards this end.”

It’s time for a global uprising. The lower classes should organize and turn their gaze — and their weapons — to the top.

Our common goal must be to deprive the rich of their ability to steal from the poor and the powerful of their ability to destroy the planet.

Stand up.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Implementing Decisive Ecological Warfare

[Link] Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

It’s important to note that, as in the case of protracted popular warfare, Decisive Ecological Warfare is not necessarily a linear progression. In this scenario resisters fall back on previous phases as necessary. After major setbacks, resistance organizations focus on survival and networking as they regroup and prepare for more serious action. Also, resistance movements progress through each of the phases, and then recede in reverse order. That is, if global industrial infrastructure has been successfully disrupted or fragmented (phase IV) resisters return to systems disruption on a local or regional scale (phase III). And if that is successful, resisters move back down to phase II, focusing their efforts on the worst remaining targets.

And provided that humans don’t go extinct, even this scenario will require some people to stay at phase I indefinitely, maintaining a culture of resistance and passing on the basic knowledge and skills necessary to fight back for centuries and millennia.

The progression of Decisive Ecological Warfare could be compared to ecological succession. A few months ago I visited an abandoned quarry, where the topsoil and several layers of bedrock had been stripped and blasted away, leaving a cubic cavity several stories deep in the limestone. But a little bit of gravel or dust had piled up in one corner, and some mosses had taken hold. The mosses were small, but they required very little in the way of water or nutrients (like many of the shoestring affinity groups I’ve worked with). Once the mosses had grown for a few seasons, they retained enough soil for grasses to grow.

Quick to establish, hardy grasses are often among the first species to reinhabit any disturbed land. In much the same way, early resistance organizations are generalists, not specialists. They are robust and rapidly spread and reproduce, either spreading their seeds aboveground or creating underground networks of rhizomes.

The grasses at the quarry built the soil quickly, and soon there was soil for wildflowers and more complex organisms. In much the same way, large numbers of simple resistance organizations help to establish communities of resistance, cultures of resistance, that can give rise to more complex and more effective resistance organizations.

The hypothetical actionists who put this strategy into place are able to intelligently move from one phase to the next: identifying when the correct elements are in place, when resistance networks are sufficiently mobilized and trained, and when external pressures dictate change. In the US Army’s field manual on operations, General Eric Shinseki argues that the rules of strategy “require commanders to master transitions, to be adaptive. Transitions—deployments, the interval between initial operation and sequels, consolidation on the objective, forward passage of lines—sap operational momentum. Mastering transitions is the key to maintaining momentum and winning decisively.”

This is particularly difficult to do when resistance does not have a central command. In this scenario, there is no central means of dispersing operational or tactical orders, or effectively gathering precise information about resistance forces and allies. Shinseki continues: “This places a high premium on readiness—well trained Soldiers; adaptive leaders who understand our doctrine; and versatile, agile, and lethal formations.” People resisting civilization in this scenario are not concerned with “lethality” so much as effectiveness, but the general point stands.

Resistance to civilization is inherently decentralized. That goes double for underground groups which have minimal contact with others. To compensate for the lack of command structure, a general grand strategy in this scenario becomes widely known and accepted. Furthermore, loosely allied groups are ready to take action whenever the strategic situation called for it. These groups are prepared to take advantage of crises like economic collapses.

Under this alternate scenario, underground organizing in small cells has major implications for applying the principles of war. The ideal entity for taking on industrial civilization would have been a large, hierarchal paramilitary network. Such a network could have engaged in the training, discipline, and coordinated action required to implement decisive militant action on a continental scale. However, for practical reasons, a single such network never arises. Similar arrangements in the history of resistance struggle, such as the IRA or various territory-controlling insurgent groups, happened in the absence of the modern surveillance state and in the presence of a well-developed culture of resistance and extensive opposition to the occupier.

Although underground cells can still form out of trusted peers along kinship lines, larger paramilitary networks are more difficult to form in a contemporary anticivilization context. First of all, the proportion of potential recruits in the general population is smaller than in any anticolonial or antioccupation resistance movements in history. So it takes longer and is more difficult to expand existing underground networks. The option used by some resistance groups in Occupied France was to ally and connect existing cells. But this is inherently difficult and dangerous. Any underground group with proper cover would be invisible to another group looking for allies (there are plenty of stories from the end of the war of resisters living across the hall from each other without having realized each other’s affiliation). And in a panopticon, exposing yourself to unproven allies is a risky undertaking.

A more plausible underground arrangement in this scenario is for there to have been a composite of organizations of different sizes, a few larger networks with a number of smaller autonomous cells that aren’t directly connected through command lines. There are indirect connections or communications via cutouts, but those methods are rarely consistent or reliable enough to permit coordinated simultaneous actions on short notice.

Individual cells rarely have the numbers or logistics to engage in multiple simultaneous actions at different locations. That job falls to the paramilitary groups, with cells in multiple locations, who have the command structure and the discipline to properly carry out network disruption. However, autonomous cells maintain readiness to engage in opportunistic action by identifying in advance a selection of appropriate local targets and tactics. Then once a larger simultaneous action happened (causing, say, a blackout), autonomous cells take advantage of the opportunity to undertake their own actions, within a few hours. In this way unrelated cells engage in something close to simultaneous attacks, maximizing their effectiveness. Of course, if decentralized groups frequently stage attacks in the wake of larger “trigger actions,” the corporate media may stop broadcasting news of attacks to avoid triggering more. So, such an approach has its limits, although large-scale effects like national blackouts can’t be suppressed in the news (and in systems disruption, it doesn’t really matter what caused a blackout in the first place, because it’s still an opportunity for further action).

When we look at some struggle or war in history, we have the benefit of hindsight to identify flaws and successes. This is how we judge strategic decisions made in World War II, for example, or any of those who have tried (or not) to intervene in historical holocausts. Perhaps it would be beneficial to imagine some historians in the distant future—assuming humanity survives—looking back on the alternate future just described. Assuming it was generally successful, how might they analyze its strengths and weaknesses?

For these historians, phase IV is controversial, and they know it had been controversial among resisters at the time. Even resisters who agreed with militant actions against industrial infrastructure hesitated when contemplating actions with possible civilian consequences. That comes as no surprise, because members of this resistance were driven by a deep respect and care for all life. The problem is, of course, that members of this group knew that if they failed to stop this culture from killing the planet, there would be far more gruesome civilian consequences.

A related moral conundrum confronted the Allies early in World War II, as discussed by Eric Markusen and David Kopf in their book The Holocaust and Strategic Bombing: Genocide and Total War in the Twentieth Century. Markusen and Kopf write that: “At the beginning of World War II, British bombing policy was rigorously discriminating—even to the point of putting British aircrews at great risk. Only obvious military targets removed from population centers were attacked, and bomber crews were instructed to jettison their bombs over water when weather conditions made target identification questionable. Several factors were cited to explain this policy, including a desire to avoid provoking Germany into retaliating against non-military targets in Britain with its then numerically superior air force.”

Other factors included concerns about public support, moral considerations in avoiding civilian casualties, the practice of the “Phoney War” (a declared war on Germany with little real combat), and a small air force which required time to build up. The parallels between the actions of the British bombers and the actions of leftist militants from the Weather Underground to the ELF are obvious.

The problem with this British policy was that it simply didn’t work. Germany showed no such moral restraint, and British bombing crews were taking greater risks to attack less valuable targets. By February of 1942, bombing policy changed substantially. In fact, Bomber Command began to deliberately target enemy civilians and civilian morale—particularly that of industrial workers—especially by destroying homes around target factories in order to “dehouse” workers. British strategists believed that in doing so they could sap Germany’s will to fight. In fact, some of the attacks on civilians were intended to “punish” the German populace for supporting Hitler, and some strategists believed that, after sufficient punishment, the population would rise up and depose Hitler to save themselves. Of course, this did not work; it almost never does.

So, this was one of the dilemmas faced by resistance members in this alternate future scenario: while the resistance abhorred the notion of actions affecting civilians—even more than the British did in early World War II—it was clear to them that in an industrial nation the “civilians” and the state are so deeply enmeshed that any impact on one will have some impact on the other.

Historians now believe that Allied reluctance to attack early in the war may have cost many millions of civilian lives. By failing to stop Germany early, they made a prolonged and bloody conflict inevitable. General Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, said as much during his war crimes trial at Nuremburg: “[I]f we did not collapse already in the year 1939 that was due only to the fact that during the Polish campaign, the approximately 110 French and British divisions in the West were held completely inactive against the 23 German divisions.”

Many military strategists have warned against piecemeal or half measures when only total war will do the job. In his book Grand Strategy: Principles and Practices, John M. Collins argues that timid attacks may strengthen the resolve of the enemy, because they constitute a provocation but don’t significantly damage the physical capability or morale of the occupier. “Destroying the enemy’s resolution to resist is far more important than crippling his material capabilities … studies of cause and effect tend to confirm that violence short of total devastation may amplify rather than erode a people’s determination.” Consider, though, that in this 1973 book Collins may underestimate the importance of technological infrastructure and decisive strikes on them. (He advises elsewhere in the book that computers “are of limited utility.”)

Other strategists have prioritized the material destruction over the adversary’s “will to fight.” Robert Anthony Pape discusses the issue in Bombing to Win, in which he analyzes the effectiveness of strategic bombing in various wars. We can wonder in this alternate future scenario if the resisters attended to Pape’s analysis as they weighed the benefits of phase III (selective actions against particular networks and systems) vs. phase IV (attempting to destroy as much of the industrial infrastructure as possible).

Specifically, Pape argues that targeting an entire economy may be more effective than simply going after individual factories or facilities:

Strategic interdiction can undermine attrition strategies, either by attacking weapons plants or by smashing the industrial base as a whole, which in turn reduces military production. Of the two, attacking weapons plants is the less effective. Given the substitution capacities of modern industrial economies, “war” production is highly fungible over a period of months. Production can be maintained in the short term by running down stockpiles and in the medium term by conservation and substitution of alternative materials or processes. In addition to economic adjustment, states can often make doctrinal adjustments.

This analysis is poignant, but it also demonstrates a way in which the goals of this alternate scenario’s strategy differed from the goals of strategic bombing in historical conflicts. In the Allied bombing campaign (and in other wars where strategic bombing was used), the strategic bombing coincided with conventional ground, air, and naval battles. Bombing strategists were most concerned with choking off enemy supplies to the battlefield. Strategic bombing alone was not meant to win the war; it was meant to support conventional forces in battle. In contrast, in this alternate future, a significant decrease in industrial production would itself be a great success.

The hypothetical future historians perhaps ask, “Why not simply go after the worst factories, the worst industries, and leave the rest of the economy alone?” Earlier stages of Decisive Ecological Warfare did involve targeting particular factories or industries. However, the resisters knew that the modern industrial economy was so thoroughly integrated that anything short of general economic distruption was unlikely to have lasting effect.

This, too, is shown by historical attempts to disrupt economies. Pape continues, “Even when production of an important weapon system is seriously undermined, tactical and operational adjustments may allow other weapon systems to substitute for it.… As a result, efforts to remove the critical component in war production generally fail.” For example, Pape explains, the Allies carried out a bombing campaign on German aircraft engine plants. But this was not a decisive factor in the struggle for air superiority. Mostly, the Allies defeated the Luftwaffe because they shot down and killed so many of Germany’s best pilots.

Another example of compensation is the Allied bombing of German ball bearing plants. The Allies were able to reduce the German production of ball bearings by about 70 percent. But this did not force a corresponding decrease in German tank forces. The Germans were able to compensate in part by designing equipment that required fewer bearings. They also increased their production of infantry antitank weapons. Early in the war, Germany was able to compensate for the destruction of factories in part because many factories were running only one shift. They were not using their existing industrial capacity to its fullest. By switching to double or triple shifts, they were able to (temporarily) maintain production.

Hence, Pape argues that war economies have no particular point of collapse when faced with increasing attacks, but can adjust incrementally to decreasing supplies. “Modern war economies are not brittle. Although individual plants can be destroyed, the opponent can reduce the effects by dispersing production of important items and stockpiling key raw materials and machinery. Attackers never anticipate all the adjustments and work-arounds defenders can devise, partly because they often rely on analysis of peacetime economies and partly because intelligence of the detailed structure of the target economy is always incomplete.” This is a valid caution against overconfidence, but the resisters in this scenario recognized that his argument was not fully applicable to their situation, in part for the reasons we discussed earlier, and in part because of reasons that follow.

Military strategists studying economic and industrial disruption are usually concerned specifically with the production of war materiel and its distribution to enemy armed forces. Modern war economies are economies of total warin which all parts of society are mobilized and engaged in supporting war. So, of course, military leaders can compensate for significant disruption; they can divert materiel or rations from civilian use or enlist civilians and civilian infrastructure for military purposes as they please. This does not mean that overall production is unaffected (far from it), simply that military production does not decline as much as one might expect under a given onslaught.

Resisters in this scenario had a different perspective on compensation measures than military strategists. To understand the contrast, pretend that a military strategist and a militant ecological strategist both want to blow up a fuel pipeline that services a major industrial area. Let’s say the pipeline is destroyed and the fuel supply to industry is drastically cut. Let’s say that the industrial area undertakes a variety of typical measures to compensate—conservation, recycling, efficiency measures, and so on. Let’s say they are able to keep on producing insulation or refrigerators or clothing or whatever it is they make, in diminished numbers and using less fuel. They also extend the lifespan of their existing refrigerators or clothing by repairing them. From the point of view of the military strategist, this attack has been a failure—it has a negligible effect on materiel availability for the military. But from the perspective of the militant ecologist, this is a victory. Ecological damage is reduced, and with very few negative effects on civilians. (Indeed, some effects would be directly beneficial.)

And modern economies in general are brittle. Military economies mobilize resources and production by any means necessary, whether that means printing money or commandeering factories. They are economies of crude necessity. Industrial economies, in contrast, are economies of luxury. They mostly produce things that people don’t need. Industrial capitalism thrives on manufacturing desire as much as on manufacturing products, on selling people disposable plastic garbage, extra cars, and junk food. When capitalist economies hit hard times, as they did in the Great Depression, or as they did in Argentina a decade ago, or as they have in many places in many times, people fall back on necessities, and often on barter systems and webs of mutual aid. They fall back on community and household economies, economies of necessity that are far more resilient than industrial capitalism, and even more robust than war economies.

Nonetheless, Pape makes an important point when he argues, “Strategic interdiction is most effective when attacks are against the economy as a whole. The most effective plan is to destroy the transportation network that brings raw materials and primary goods to manufacturing centers and often redistributes subcomponents among various industries. Attacking national electric power grids is not effective because industrial facilities commonly have their own backup power generation. Attacking national oil refineries to reduce backup power generators typically ignores the ability of states to reduce consumption through conservation and rationing.” Pape’s analysis is insightful, but again it’s important to understand the differences between his premises and goals, and the premises and goals of Decisive Ecological Warfare.

The resisters in the DEW scenario had the goals of reducing consumption and reducing industrial activity, so it didn’t matter to them that some industrial facilities had backup generators or that states engaged in conservation and rationing. They believed it was a profound ecological victory to cause factories to run on reduced power or for nationwide oil conservation to have taken place. They remembered that in the whole of its history, the mainstream environmental movement was never even able to stop the growth of fossil fuel consumption. To actually reduce it was unprecedented.

No matter whether we are talking about some completely hypothetical future situation or the real world right now, the progress of peak oil will also have an effect on the relative importance of different transportation networks. In some areas, the importance of shipping imports will increase because of factors like the local exhaustion of oil. In others, declining international trade and reduced economic activity will make shipping less important. Highway systems may have reduced usage because of increasing fuel costs and decreasing trade. This reduced traffic will leave more spare capacity and make highways less vulnerable to disruption. Rail traffic—a very energy-efficient form of transport—is likely to increase in importance. Furthermore, in many areas, railroads have been removed over a period of several decades, so that remaining lines are even now very crowded and close to maximum capacity.

Back to the alternative future scenario: In most cases, transportation networks were not the best targets. Road transportation (by far the most important form in most countries) is highly redundant. Even rural parts of well-populated areas are crisscrossed by grids of county roads, which are slower than highways, but allow for detours.

In contrast, targeting energy networks was a higher priority to them because the effect of disrupting them was greater. Many electrical grids were already operating near capacity, and were expensive to expand. They became more important as highly portable forms of energy like fossil fuels were partially replaced by less portable forms of energy, specifically electricity generated from coal-burning and nuclear plants, and to a lesser extent by wind and solar energy. This meant that electrical grids carried as much or more energy as they do now, and certainly a larger percentage of all energy consumed. Furthermore, they recognized that energy networks often depend on a few major continent-spanning trunks, which were very vulnerable to disruption.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Why Decisive Dismantling and Warfare?

[Link] Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There is one final argument that resisters in this scenario made for actions against the economy as a whole, rather than engaging in piecemeal or tentative actions: the element of surprise. They recognized that sporadic sabotage would sacrifice the element of surprise and allow their enemy to regroup and develop ways of coping with future actions. They recognized that sometimes those methods of coping would be desirable for the resistance (for example, a shift toward less intensive local supplies of energy) and sometimes they would be undesirable (for example, deployment of rapid repair teams, aerial monitoring by remotely piloted drones, martial law, etc.). Resisters recognized that they could compensate for exposing some of their tactics by carrying out a series of decisive surprise operations within a larger progressive struggle.

On the other hand, in this scenario resisters understand that DEW depended on relatively simple “appropriate technology” tactics (both aboveground and underground). It depended on small groups and was relatively simple rather than complex. There was not a lot of secret tactical information to give away. In fact, escalating actions with straightforward tactics were beneficial to their resistance movement. Analyst John Robb has discussed this point while studying insurgencies in countries like Iraq. Most insurgent tactics are not very complex, but resistance groups can continually learn from the examples, successes, and failures of other groups in the “bazaar” of insurgency. Decentralized cells are able to see the successes of cells they have no direct communication with, and because the tactics are relatively simple, they can quickly mimic successful tactics and adapt them to their own resources and circumstances. In this way, successful tactics rapidly proliferate to new groups even with minimal underground communication.

Hypothetical historians looking back might note another potential shortcoming of DEW: that it required perhaps too many people involved in risky tactics, and that resistance organizations lacked the numbers and logistical persistence required for prolonged struggle. That was a valid concern, and was dealt with proactively by developing effective support networks early on. Of course, other suggested strategies—such as a mass movement of any kind—required far more people and far larger support networks engaging in resistance. Many underground networks operated on a small budget, and although they required more specialized equipment, they generally required far fewer resources than mass movements.

Continuing this scenario a bit further, historians asked: how well did Decisive Ecological Warfare rate on the checklist of strategic criteria we provided at the end of the Introduction to Strategy.

Objective: This strategy had a clear, well-defined, and attainable objective.

Feasibility: This strategy had a clear A to B path from the then-current context to the desired objective, as well as contingencies to deal with setbacks and upsets. Many believed it was a more coherent and feasible strategy than any other they’d seen proposed to deal with these problems.

Resource Limitations: How many people are required for a serious and successful resistance movement? Can we get a ballpark number from historical resistance movements and insurgencies of all kinds?

- The French Resistance. Success indeterminate. As we noted in the “The Psychology of Resistance” chapter: The French Resistance at most comprised perhaps 1 percent of the adult population, or about 200,000 people. The postwar French government officially recognized 220,000 people (though one historian estimates that the number of active resisters could have been as many as 400,000). In addition to active resisters, there were perhaps another 300,000 with substantial involvement. If you include all of those people who were willing to take the risk of reading the underground newspapers, the pool of sympathizers grows to about 10 percent of the adult population, or two million people. The total population of France in 1940 was about forty-two million, so recognized resisters made up one out of every 200 people.

- The Irish Republican Army. Successful. At the peak of Irish resistance to British rule, the Irish War of Independence (which built on 700 years of resistance culture), the IRA had about 100,000 members (or just over 2 percent of the population of 4.5 million), about 15,000 of whom participated in the guerrilla war, and 3,000 of whom were fighters at any one time. Some of the most critical and decisive militants were in the “Twelve Disciples,” a tiny number of people who swung the course of the war. The population of occupying England at the time was about twenty-five million, with another 7.5 million in Scotland and Wales. So the IRA membership comprised one out of every forty Irish people, and one out of every 365 people in the UK. Collins’s Twelve Disciples were one out of 300,000 in the Irish population.

- The antioccupation Iraqi insurgency. Indeterminate success. How many insurgents are operating in Iraq? Estimates vary widely and are often politically motivated, either to make the occupation seem successful or to justify further military crackdowns, and so on. US military estimates circa 2006 claim 8,000–20,000 people. Iraqi intelligence estimates are higher. The total population is thirty-one million, with a land area about 438,000 square kilometers. If there are 20,000 insurgents, then that is one insurgent for every 1,550 people.

- The African National Congress. Successful. How many ANC members were there? Circa 1979, the “formal political underground” consisted of 300 to 500 individuals, mostly in larger urban centers. The South African population was about twenty-eight million at the time, but census data for the period is notoriously unreliable due to noncooperation. That means the number of formal underground ANC members in 1979 was one out of every 56,000.

- The Weather Underground. Unsuccessful. Several hundred initially, gradually dwindling over time. In 1970 the US population was 179 million, so they were literally one in a million.

- The Black Panthers. Indeterminate success. Peak membership was in late 1960s with over 2,000 members in multiple cities. That’s about one in 100,000.

- North Vietnamese Communist alliance during Second Indochina War. Successful. Strength of about half a million in 1968, versus 1.2 million anti-Communist soldiers. One figure puts the size of the Vietcong army in 1964 at 1 million. It’s difficult to get a clear figure for total of combatants and noncombatants because of the widespread logistical support in many areas. Population in late 1960s was around forty million (both North and South), so in 1968, about one of every eighty Vietnamese people was fighting for the Communists.

- Spanish Revolutionaries in the Spanish Civil War. Both successful and unsuccessful. The National Confederation of Labor (CNT) in Spain had a membership of about three million at its height. A major driving force within the CNT was the anarchist FAI, a loose alliance of militant affinity groups. The Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) had a membership of perhaps 5,000 to 30,000 just prior to revolution, a number which increased significantly with the onset of war. The CNT and FAI were successful in bringing about a revolution in part of Spain, but were later defeated on a national scale by the Fascists. The Spanish population was about 26 million. So about one in nine Spaniards were CNT members, and (assuming the higher figure) about one in 870 Spaniards was FAI members.

- Poll tax resistance against Margaret Thatcher circa 1990. Successful. About fourteen million people were mobilized. In a population of about fifty-seven million, that’s about one in four (although most of those people participated mostly by refusing to pay a new tax).

- British suffragists. Successful. It’s hard to find absolute numbers for all suffragists. However, there were about 600 nonmilitant women’s suffrage societies. There were also militants, of whom over a thousand went to jail. The militants made all suffrage groups—even the nonmilitant ones—swell in numbers. Based on the British population at the time, the militants were perhaps one in 15,000 women, and there was a nonmilitant suffrage society for every 25,000 women.

- Sobibór uprising. Successful. Less than a dozen core organizers and conspirators. Majority of people broke out of the camp and the camp was shut down. Up to that point perhaps a quarter of a million people had been killed at the camp. The core organizers made up perhaps one in sixty of the Jewish occupants of the camp at the time, and perhaps one in 25,000 of those who had passed through the camp on the way to their deaths.

It’s clear that a small group of intelligent, dedicated, and daring people can be extremely effective, even if they only number one in 1,000, or one in 10,000, or even one in 100,000. But they are effective in large part through an ability to mobilize larger forces, whether those forces are social movements (perhaps through noncooperation campaigns like the poll tax) or industrial bottlenecks.

Furthermore, it’s clear that if that core group can be maintained, it’s possible for it to eventually enlarge itself and become victorious.

All that said, future historians discussing this scenario will comment that DEW was designed to make maximum use of small numbers, rather than assuming that large numbers of people would materialize for timely action. If more people had been available, the strategy would have become even more effective. Furthermore, they might comment that this strategy attempted to mobilize people from a wide variety of backgrounds in ways that were feasible for them; it didn’t rely solely on militancy (which would have excluded large numbers of people) or on symbolic approaches (which would have provoked cynicism through failure).

Tactics: The tactics required for DEW were relatively simple and accessible, and many of them were low risk. They were appropriate to the scale and seriousness of the objective and the problem. Before the beginnings of DEW, the required tactics were not being implemented because of a lack of overall strategy and of organizational development both above- and underground. However, that strategy and organization were not technically difficult to develop—the main obstacles were ideological.

Risk: In evaluating risk, members of the resistance and future historians considered both the risks of acting and the risks of not acting: the risks of implementing a given strategy and the risks of not implementing it. In their case, the failure to carry out an effective strategy would have resulted in a destroyed planet and the loss of centuries of social justice efforts. The failure to carry out an effective strategy (or a failure to act at all) would have killed billions of humans and countless nonhumans. There were substantial risks for taking decisive action, risks that caused most people to stick to safer symbolic forms of action. But the risks of inaction were far greater and more permanent.

Timeliness: Properly implemented, Decisive Ecological Warfare was able to accomplish its objective within a suitable time frame, and in a reasonable sequence. Under DEW, decisive action was scaled up as rapidly as it could be based on the underlying support infrastructure. The exact point of no return for catastrophic climate change was unclear, but if there are historians or anyone else alive in the future, DEW and other measures were able to head off that level of climate change. Most other proposed measures in the beginning weren’t even trying to do so.

Simplicity and Consistency: Although a fair amount of context and knowledge was required to carry out this strategy, at its core it was very simple and consistent. It was robust enough to deal with unexpected events, and it could be explained in a simple and clear manner without jargon. The strategy was adaptable enough to be employed in many different local contexts.

Consequences: Action and inaction both have serious consequences. A serious collapse—which could involve large-scale human suffering—was frightening to many. Resisters in this alternate future believed first and foremost that a terrible outcome was not inevitable, and that they could make real changes to the way the future unfolded.

** *** ***** ******* *********** *************

Green Technology and Renewable Energy FAQ

[Link] Q: Will green technology save the planet?

A: No. Wind turbines, solar PV panels, and the grid itself are all manufactured using cheap energy from fossil fuels. When fossil fuel costs begin to rise such highly manufactured items will simply cease to be feasible.

Solar panels and wind turbines aren’t made out of nothing. They are made out of metals, plastics, and chemicals. These products have been mined out of the ground, transported, processed, manufactured. Each stage leaves behind a trail of devastation: habitat destruction, water contamination, colonization, toxic waste, slave labor, greenhouse gas emissions, wars, and corporate profits.

The basic ingredients for renewables are the same materials that are ubiquitous in industrial products, like cement and aluminum. No one is going to make cement in any quantity without using the energy of fossil fuels. And aluminum? The mining itself is a destructive and toxic nightmare from which riparian communities will not awaken in anything but geologic time.

From beginning to end, so called “renewable energy” and other “green technologies” lead to the destruction of the planet. These technologies are rooted in the same industrial extraction and production processes that have rampaged across the world for the last 150 years.

We are not concerned with slightly reducing the harm caused by industrial civilization; we are interested in stopping that harm completely. Doing so will require dismantling the global industrial economy, which will render impossible the creation of these technologies.

Q: Aren’t renewable energies like solar, wind, and geothermal good for the environment?

A: No. The majority of electricity that is generated by renewables is used in manufacturing, mining, and other industries that are destroying the planet. Even if the generation of electricity were harmless, the consumption certainly isn’t. Every electrical device, in the process of production, leaves behind the same trail of devastation. Living communities — forests, rivers, oceans — become dead commodities.

The emissions reductions that renewables intend to achieve could be easily accomplished by improving the efficiency of existing coal plants, businesses, and homes, at a much lower cost. Within the context of industrial civilization, this approach makes more sense both economically and environmentally.

That this approach is not being taken shows that the whole renewables industry is nothing but profiteering. It benefits no one other than the investors.

Q: Does “renewable” mean that they last forever?

A: No. Solar panels and wind turbines last around 20–30 years, then need to be replaced. The production process of extracting, polluting, and exploiting is not something that happens once, but is continuous – and is expanding very rapidly. Renewables can never replace fossil fuel infrastructure, as they are entirely dependent on it.

Q: Will renewable energy save the economy?

A: Renewable energy technologies rely heavily on government subsidies, taken from taxpayers and given directly to large corporations like General Electric, BP, Samsung, and Mitsubishi. While the scheme pads their bottom lines, it doesn’t help the rest of us.

Further, this is the wrong question to ask. The industrial capitalist economy is dispossessing and impoverishing billions of humans and killing the living world. Renewable energy depends on centralized capital and power imbalance. We don’t benefit from saving that system.

Instead of advocating for more industrial technology, we need to move to local economies based on community decision-making and what our local landbases can provide sustainably. And we need to stop the global economy on which renewable energy depends.

Q: Ok, metal extraction is harmful. What about recycling the materials?

A: Recycling may be “more efficient” than virgin extraction, but it is not a solution to environmental problems. In fact, it contributes to them.

Recycling the aluminum, steel, silicon, copper, rare earth metals, and other substances used in “green technologies” can only be done at great cost to the planet. Recycling these substances is extremely energy intensive, releases large amounts of greenhouse gases, and contributes to groundwater pollution and toxification of the planet.

Recycling metals requires global trade, as the recycling mostly takes place in impoverished countries with lax environmental and health regulations. It is extremely dangerous for the workers. Many parts of renewable technologies cannot be recycled.

Q: Ok, renewable technologies have some impacts, but they’re still better than fossil fuels, right?

A: Renewable energy technologies are better than fossil fuels in the same sense that a single bullet wound is “better” than two bullet wounds. Both are grievous injuries.

Do you want to shoot the planet once or twice?

The only way out of a double bind is to smash it: to refuse both choices and craft a completely different path. We support neither fossil fuels or renewable tech.

Even this bullet analogy isn’t completely accurate, since renewable technologies, in some cases, have a worse environmental impact than fossil fuels.

More renewables doesn’t mean less fossil fuel power, or less carbon emissions. The amount of energy generated by renewables has been increasing, but so has the amount generated by fossil fuels. No coal or gas plants have been taken offline as a result of renewables.

Only about 25% of global energy use is in the form of electricity that flows through wires or batteries. The rest is oil, gas, and other fossil fuel derivatives. Even if all the world’s electricity could be produced without carbon emissions, it would only reduce total emissions by about 25%. And even that would have little meaning, as the amount of energy being used is increasing rapidly.

It’s debatable whether some “renewables” even produce net energy. The amount of energy used in the mining, manufacturing, research and development, transport, installation, maintenance, grid connection, and disposal of wind turbines and solar panels may be more than they ever produce; claims to the contrary often do not take all the energy inputs into account. Renewables have been described as a laundering scheme: dirty energy goes in, clean energy comes out.