by DGR News Service | Sep 18, 2021 | Agriculture, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis, Worker Exploitation

This article originally appeared in Climate & Capitalism.

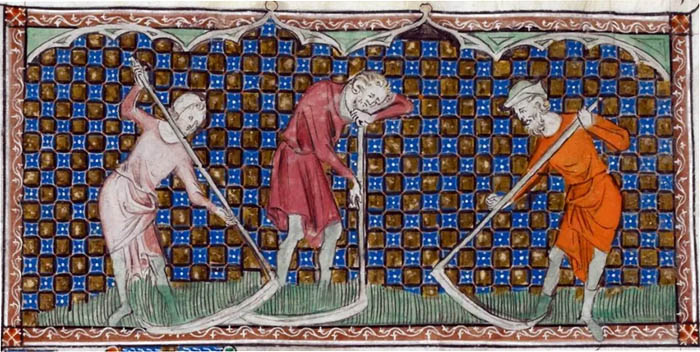

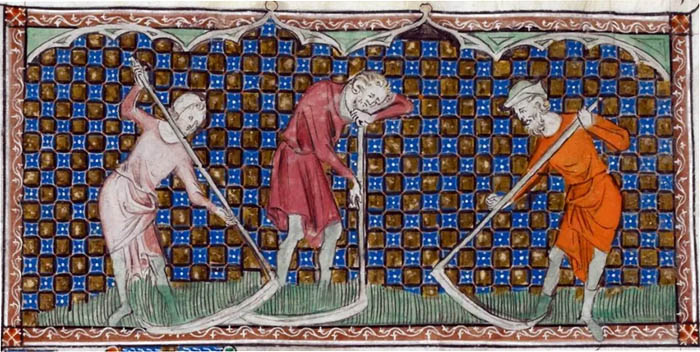

Featured image: Harvesting grain in the 1400s

Editor’s note: We are no Marxists, but we find it important to look at history from the perspective of the usual people, the peasants, and the poor, since liberal historians tend to follow the narrative of endless progress and neglect all the violence and injustice this “progress” was and is based on. Garrett Hardin’s annoying but very influential essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” is a good example, and we are thankful to the author for debunking it.

“All progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil.” (Karl Marx)

Articles in this series:

Commons and classes before capitalism

‘Systematic theft of communal property’

Against Enclosure: The Commonwealth Men

Dispossessed: Origins of the Working Class

Against Enclosure: The Commoners Fight Back

by Ian Angus

To live, humans must eat, and more than 90% of our food comes directly or indirectly from soil. As philosopher Wendell Berry says, “The soil is the great connector of lives…. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life.”[1]

Preventing soil degradation and preserving soil fertility ought to be a global priority, but it isn’t. According to the United Nations, a third of the world’s land is now severely degraded, and we lose 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil every year. More than 1.3 billion people depend on food from degraded or degrading agricultural land.[2] Even in the richest countries, almost all food production depends on massive applications of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides that further degrade the soil and poison the environment.

In Karl Marx’s words, “a rational agriculture is incompatible with the capitalist system.”[3] To understand why that is, we need to understand how capitalist agriculture emerged from a very different system.

****

For almost all of human history, almost all of us lived and worked on the land. Today, most of us live in cities.

It is hard to overstate how radical that change is, or how quickly it happened. Two hundred years ago, 90% of the world’s population was rural. Britain became the world’s first majority-urban country in 1851. As recently as 1960, two-thirds of the world’s people still lived in rural areas. Now it’s less than half, and only half of those are farmers.

Between the decline of feudalism and the rise of industrial capitalism, rural society was transformed by the complex of processes that are collectively known as enclosure. The separation of most people from the land, and the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a tiny minority, were revolutionary changes in the ways that humans lived and work. It happened in different ways and at different times in different parts of the world, and is still going on today.

Our starting point is England, where what Marx labelled “so-called primitive accumulation” first occurred.

Common Fields, Common Rights

In medieval and early-modern England, most people were poor, but they were also self-provisioning — they obtained their essential needs directly from the land, which was a common resource, not private property as we understand the concept.

No one actually knows when or how English common farming systems began. Most likely they were brought to England by Anglo-Saxon settlers after Roman rule ended. What we know for sure is that common field agriculture was widespread, in various forms, when English feudalism was at its peak in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The land itself was held by landlords, directly or indirectly from the king. A minor gentry family might hold and live on just one manor — roughly equivalent to a township — while a top aristocrat, bishop or monastery could hold dozens. The people who actually worked the land, often including a mix of unfree serfs and free peasants, paid rent and other fees in labor, produce or (later) cash, and had, in addition to the use of arable land, a variety of legal and traditional rights to use the manor’s resources, such as grazing animals on common pasture, gathering firewood, berries and nuts in the manor forest, and collecting (gleaning) grain that remained in the fields after harvest.

“Common rights were managed, divided, and redivided by the communities. These rights were predicated on maintaining relations and activities that contributed to the collective reproduction. No feudal lord had rights to the land exclusive of such customary rights of the commoners. Nor did they have the right to seize or engross the common fields as their own domain.”[4]

Field systems varied a great deal, but usually a manor or township included both the landlord’s farm (demesne) and land that was farmed by tenants who had life-long rights to use it. Most accounts only discuss open field systems, in which each tenant cultivated multiple strips of land that were scattered through the arable fields so no one family had all the best soil, but there were other arrangements. In parts of southwestern England and Scotland, for example, farms on common arable land were often compact, not in strips, and were periodically redistributed among members of the commons community. This was called runrig; a similar arrangement in Ireland was called rundale.

Most manors also had shared pasture for feeding cattle, sheep and other animals, and in some cases forest, wetlands and waterways.

Though cooperative, these were not communities of equals. Originally, all of the holdings may have been about the same size but in time considerable economic differentiation took place.[5] A few well-to-do tenants held land that produced enough to sell in local markets; others (probably a majority in most villages) had enough land to sustain their families with a small surplus in good years; others with much less land probably worked part-time for their better-off neighbors or for the landlord. “We can see this stratification right across the English counties in Domesday Book of 1086, where at least one-third of the peasant population were smallholders. By the end of the thirteenth century this proportion, in parts of southeastern England, was over a half.”[6]

As Marxist historian Rodney Hilton explains, the economic differences among medieval peasants were not yet class differences. “Poor smallholders and richer peasants were, in spite of the differences in their incomes, still part of the same social group, with a similar style of life, and differed from one to the other in the abundance rather than the quality of their possessions.”[7] It wasn’t until after the dissolution of feudalism in the fifteenth century that a layer of capitalist farmers developed.

Self-Management

If we were to believe an influential article published in 1968, commons-based agriculture ought to have disappeared shortly after it was born. In “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Garrett Hardin argued that commoners would inevitably overuse resources, causing ecological collapse. In particular, in order to maximize his income, “each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons,” until overgrazing destroys the pasture, and it supports no animals at all. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”[8]

Since its publication in 1968, Hardin’s account has been widely adopted by academics and policy makers, and used to justify stealing indigenous peoples’ lands, privatizing health care and other social services, giving corporations ‘tradable permits’ to pollute the air and water, and more. Remarkably, few of those who have accepted Hardin’s views as authoritative notice that he provided no evidence to support his sweeping conclusions. He claimed that “tragedy” was inevitable, but he didn’t show that it had happened even once.[9]

Scholars who have actually studied commons-based agriculture have drawn very different conclusions. “What existed in fact was not a ‘tragedy of the commons’ but rather a triumph: that for hundreds of years — and perhaps thousands, although written records do not exist to prove the longer era — land was managed successfully by communities.”[10]

The most important account of how common-field agriculture in England actually worked is Jeanette Neeson’s award-winning book, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820. Her study of surviving manorial records from the 1700s showed that the common-field villagers, who met two or three times a year to decide matters of common interest, were fully aware of the need to regulate the metabolism between livestock, crops and soil.

“The effective regulation of common pasture was as significant for productivity levels as the introduction of fodder crops and the turning of tilled land back to pasture, perhaps more significant. Careful control allowed livestock numbers to grow, and, with them, the production of manure. … Field orders make it very clear that common-field villagers tried both to maintain the value of common of pasture and also to feed the land.”[11]

Village meetings selected “juries” of experienced farmers to investigate problems, and introduce permanent or temporary by-laws. Particular attention was paid to “stints” — limits on the number of animals allowed on the pasture, waste, and other common land. “Introducing a stint protected the common by ensuring that it remained large enough to accommodate the number of beasts the tenants were entitled to. It also protected lesser commoners from the commercial activities of graziers and butchers.”[12]

Juries also set rules for moving sheep around to ensure even distribution of manure, and organized the planting of turnips and other fodder plants in fallow fields, so that more animals could be fed and more manure produced. The jury in one of the manors that Neeson studied allowed tenants to pasture additional sheep if they sowed clover on their arable land — long before scientists discovered nitrogen and nitrogen-fixing, these farmers knew that clover enriched the soil.[13]

And, given present-day concerns about the spread of disease in large animal feeding facilities, it is instructive to learn that eighteenth century commoners adopted regulations to isolate sick animals, stop hogs from fouling horse ponds, and prevent outside horses and cows from mixing with the villagers’ herds. There were also strict controls on when bulls and rams could enter the commons for breeding, and juries “carefully regulated or forbade entry to the commons of inferior animals capable of inseminating sheep, cows or horses.”[14]

Neeson concludes, “the common-field system was an effective, flexible and proven way to organize village agriculture. The common pastures were well governed, the value of a common right was well maintained.”[15]

Commons-based agriculture survived for centuries precisely because it was organized and managed democratically by people who were intimately involved with the land, the crops and the community. Although it was not an egalitarian society, in some ways it prefigured what Karl Marx, referring to a socialist future, described as “the associated producers, govern[ing] the human metabolism with nature in a rational way.”[16]

Class Struggles

That’s not to say that agrarian society was tension free. There were almost constant struggles over how the wealth that peasants produced was distributed in the social hierarchy. The nobility and other landlords sought higher rents, lower taxes and limits on the king’s powers, while peasants resisted landlord encroachments on their rights, and fought for lower rents. Most such conflicts were resolved by negotiation or appeals to courts, but some led to pitched battles, as they did in 1215 when the barons forced King John to sign Magna Carta, and in 1381 when thousands of peasants marched on London to demand an end to serfdom and the execution of unpopular officials.

Historians have long debated the causes of feudalism’s decline: I won’t attempt to resolve or even summarize those complex discussions here.[17] Suffice it to say that by the early 1400s in England, the feudal aristocracy was much weakened. Peasant resistance had effectively ended hereditary serfdom and forced landlords to replace labor-service with fixed rents, while leaving common field agriculture and many common rights in place. Marx described the 1400s and early 1500s, when peasants in England were winning greater freedom and lower rents, as “a golden age for labor in the process of becoming emancipated.”[18]

But that was also a period when longstanding economic divisions within the peasantry were increasing. W.G. Hoskins described the process in his classic history of life in a Midland village.

“During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries there emerged at Wigston what may be called a peasant aristocracy, or, if this is too strong a phrase as yet, a class of capitalist peasants who owned substantially larger farms and capital resources than the general run of village farmers. This process was going on all over the Midlands during these years …”[19]

Capitalist peasants were a small minority. Agricultural historian Mark Overton estimates that “in the early sixteenth century, around 80 per cent of farmers were only growing enough food for the needs of their family household.” Of the remaining 20%, only a few were actual capitalists who employed laborers and accumulated ever more land and wealth. Nevertheless, by the 1500s two very different approaches to the land co-existed in many commons communities.

“The attitudes and behavior of farmers producing exclusively for their own needs were very different from those farmers trying to make a profit. They valued their produce in terms of what use it was to them rather than for its value for exchange in the market. … Larger, profit orientated, farmers were still constrained by soils and climate, and by local customs and traditions, but also had an eye to the market as to which crop and livestock combinations would make them most money.”[20]

As we’ll see, that division eventually led to the overthrow of the commons.

Primitive Accumulation

For Marx, the key to understanding the long transition from agrarian feudalism to industrial capitalism was “the process which divorces the worker from the ownership of the conditions of his own labor,” which itself involved “two transformations … the social means of subsistence and production are turned into capital, and the immediate producers are turned into wage-laborers.”[21]

“Nature does not produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labor-power. This relation has no basis in natural history, nor does it have a social basis common to all periods of human history. It is clearly the result of a past historical development, the product of many economic revolutions, of the extinction of a whole series of older formations of social production.”[22]

A decade before Capital was published, Marx summarized that historical development in an early draft.

“It is … precisely in the development of landed property that the gradual victory and formation of capital can be studied. … The history of landed property, which would demonstrate the gradual transformation of the feudal landlord into the landowner, of the hereditary, semi-tributary and often unfree tenant for life into the modern farmer, and of the resident serfs, bondsmen and villeins who belonged to the property into agricultural day laborers, would indeed be the history of the formation of modern capital.”[23]

In Section VIII of Capital Volume 1, titled “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation of Capital,” he expanded that paragraph into a powerful and moving account of the historical process by which the dispossession of peasants created the working class, while the land they had worked for millennia became the capitalist wealth that exploited them. It is the most explicitly historical part of Capital, and by far the most readable. No one before Marx had researched the subject so thoroughly — Harry Magdoff once commented that on re-reading it, he was immediately impressed by the depth of Marx’s scholarship, by “the amount of sheer digging, hard work, and enormous energy in the accumulated facts that show up in his sentences.”[24]

Since Marx wrote Capital, historians have published a vast amount of research on the history of English agriculture and land tenure — so much that a few decades ago, it was fashionable for academic historians to claim that Marx got it all wrong, that the privatization of common land was a beneficial process for all concerned. That view has little support today. Of course it would be very surprising if subsequent research didn’t contradict Marx in some ways, but while his account requires some modification, especially in regard to regional differences and the tempo of change, Marx’s history and analysis of the commons remains essential reading.[25]

*****

The next installments in this series will discuss how, in two great waves of social change, landlords and capitalist farmers “conquered the field for capitalist agriculture, incorporated the soil into capital, and created for the urban industries the necessary supplies of free and rightless proletarians.”[26]

To be continued ….

[1] Wendell Berry, Wendell Berry: Essays 1969-1990, ed. Jack Shoemaker (Library of America, 2019), 317.

[2] https://www.unccd.int/news-events/better-land-use-and-management-critical-achieving-agenda-2030-says-new-report

[3] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. David Fernbach, vol. 3, (Penguin Books, 1981), 216

[4] John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman, “Marx and the Commons,” Social Research (Spring 2021), 2-3.

[5] See “Reasons for Inequality Among Medieval Peasants,” in Rodney Hilton, Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism: Essays in Medieval Social History (Hambledon Press, 1985), 139-151.

[6] Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381 (Routledge, 2003 [1973]), 32.

[7] Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free, 34.

[8] Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons, Science, December 13, 1968.

[9] Ian Angus, The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons, Climate & Capitalism, August 25, 2008; Ian Angus, Once Again: ‘The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons’, Climate & Capitalism, November 3, 2008.

[10] Susan Jane Buck Cox, No Tragedy of the Commons, Environmental Ethics 7, no. 1 (1985), 60.

[11] J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 113.

[12] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 117.

[13] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 118-20.

[14] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 132.

[15] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 157.

[16] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 3, trans. David Fernbach, (Penguin Books, 1981), 959.

[17] For an insightful summary and critique of the major positions in those debates, see Henry Heller, The Birth of Capitalism: A Twenty-First Century Perspective (Pluto Press, 2011).

[18] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, trans. Martin Nicolaus (Penguin Books, 1973), 510.

[19] W. G. Hoskins, The Midland Peasant: The Economic and Social History of a Leicestershire Village (Macmillan., 1965), 141.

[20] Mark Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy, 1500-1850 (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 8, 21.

[21] Karl Marx, Capital Volume, 1, 874.

[22] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, 273.

[23] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 252-3.

[24] Harry Magdoff, “Primitive Accumulation and Imperialism,” Monthly Review (October 2013), 14.

[25] “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation” — Chapters 26 through 33 of Capital Volume 1 — can be read on the Marxist Internet Archive, beginning here. The somewhat better translation by Ben Fowkes occupies pages 873 to 940 of the Penguin edition.

[26] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, 895.

by DGR News Service | Mar 17, 2023 | ANALYSIS, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling

Editor’s Note: Taking the context of Maryland’s forests, the following piece analyses how the mainstream environmental movement and pro-industry management actors have used deliberately misinterpreting to outright creation of information to justify commercial activities at the expense of forests. Industrial deforestation is harmful for the forests and the planet. The fact that this obvious piece of information should even be stated to educated adults affirms the successful (and deceitful) framing of biomass as an environmentally friendly way out of climate crisis. The same goes for deep sea mining.

By Austin

Most would agree that we live in an age of multiple compounding catastrophes, planetary in scale. There is controversy, however, regarding their interrelationships as well as their causes. That controversy is largely manufactured. In the following pages I will describe the state of “forestry” in the state of Maryland, USA, and connect that to regional, national, and international stirrings of which we should all be aware. I will continue to examine connections between international conservation organizations, the co-optation of the environmental movement, the youth climate movement, and the financialization of nature. Full disclosure. I am writing this to human beings on behalf of all the non-human beings and those yet unborn who are recognized as objects to be converted to capital or otherwise used by the dominant culture. I am not a capitalist. I am a human being. I occupy unceded land of unrecognized peoples which is characterized by poisoned air, water and soil, devastated forest ecosystems, decapitated mountains, and collapsing biodiversity. I am of this earth. It is to the land, water and all of life that I direct my affection and gratitude as well as my loyalty.

Last winter, amid deep concerns about the present mass extinction and an unshakeable feeling of helplessness, I began to search for answers and ecological allies. I compiled a running list of local, regional, national, and international organizations that seemed to have at least some interest in the environment. The list quickly swelled to hundreds of entries. I attempted to assess the organizations based upon their mission, values, goals, publications and other such things. I hoped that the best of the best of these groups could be brought together around ecological restoration and the long-term benefits of clean air, water, healthy soil supporting vigorous growth of food and medicine, and rebounding biodiversity throughout our Appalachian homeland. Progress was and continues to be slow. Along the way, I encountered an open stakeholder consultation (survey) regarding a risk assessment of Maryland’s forests. As an ethnobotanist with special interests in forest ecology and stewardship, Indigenous societies and their traditional ecological knowledge, symbiotic relationships, and intergenerational sustainability, I realize that my unique perspectives could be helpful to the team conducting the assessment. I proceeded to submit thought provoking responses to each question. Because the consultation period was exceedingly brief and outreach to stakeholders was weak at best, and because the wording of the questions felt out of alignment with the purported purpose of the survey, I sensed that something was awry. So I saved my answers and resolved to stay abreast of developments.

Summer came around, I became busy, and the risk assessment survey faded from my mind until a friend recently emailed me a draft of the document along with notice of a second stakeholder consultation and the question: should we respond? This friend happens to own land registered in the Maryland Tree Farm Program. The selective outreach to forest landowners with large acreage was an indication as to who is and who is not considered a “stakeholder” by the committee.

After reviewing the Consultation Draft: A Sustainability Risk Assessment of Maryland’s Forests I felt sick. Low to Negligible was the risk assignment for every single criteria. I re-read the document – section by section – noting the ambiguity, legalese and industry jargon, lack of definitions, contradictory statements, false claims, poorly referenced and questionable sources, and more. Have you heard of greenwashing? Every tactic was represented in the 82 page document. Naturally, then, I tracked down and reviewed many of the referenced materials and I then investigated the contributors and funders of the report.

To understand the Sustainability Risk Assessment of Maryland’s Forests, one must also review the <a href=”https://ago-item-storage.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/90fbcb6e1acd4f019ad608f77ac2f19c/Final_Forestry_EAS_FullReport_10-2021.pdfMaryland Forestry Economic Adjustment Strategy, part one and two of Maryland Department of Natural Resources Forest Action Plan, and Seneca Creek Associates, LLC’s Assessment of Lawful Sourcing and Sustainability: US Hardwood Exports, and of course American Forests Foundation’s Final Report to the Dutch Biomass Certification Foundation (DBC) for Implementation of the AFF’s 2018 DBC Stimulation Program in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, and Louisiana. Additionally, it is helpful to note that the project development lead and essential supporters each operate independent consultancies that: offer “technical and strategic support in navigating complex forest sustainability and climate issues,” “provide(s) services in natural resource economics and international trade,” and “produced a comprehensive data research study for the Dutch Biomass Certification Foundation on the North American forest sector,” according to their websites.

Noting, furthemore, that on the Advisory Committee sits a member of the Maryland Forests Association (MFA). On their website they state: “We are proud to represent forest product businesses, forest landowners, loggers and anyone with an interest in Maryland’s forests…” They also state: “Currently, Maryland’s Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard uses a limiting definition of qualifying biomass that makes it difficult for wood to compete against other forms of renewable energy,” oh yes, and this extraordinarily deceptive bit from a recent publication, There’s More to our Forests than Trees:

When the tree dies, it decays and releases carbon dioxide and methane back into the atmosphere. However, we can postpone this process and extend the duration of carbon storage. If we harvest the tree and build a house or even make a chair with the wood, the carbon remains stored in these products for far longer than the life of the tree itself! This has tremendous implications for addressing the growing levels of carbon dioxide, which lead to increased warming of the earth’s atmosphere. It means harvesting trees for long-term uses helps mitigate climate change. We can even take advantage of the fact that trees sequester carbon at different rates throughout their lifespan to maximize the carbon storage potential. Trees are more active in sequestering carbon when they are younger. As forests age, growth slows down and so does their ability to store carbon. At some point, a stand of trees reaches an equilibrium where the growth and carbon-storing ability equals the trees that die and release carbon each year. Thus, a younger, more vigorous stand of trees stores carbon at a much higher rate than an older one.

Just in case you were convinced by that last bit, my studies in botany and forest ecology support the following finding:

“In 2014, a study published in Nature by an international team of researchers led by Nathan Stephenson, a forest ecologist with the United States Geographical Survey, found that a typical tree’s growth continues to accelerate (emphasis mine) throughout its lifetime, which in the coastal temperate rainforest can be 800 years or more.

Stephenson and his team compiled growth measurements of 673,046 trees belonging to 403 tree species from tropical, subtropical and temperate regions across six continents. They found that the growth rate for most species “increased continuously” as they aged.

“This finding contradicts the usual assumption that tree growth eventually declines as trees get older and bigger,” Stephenson says. “It also means that big, old trees are better at absorbing carbon from the atmosphere than has been commonly assumed.” (Tall and old or dense and young: Which kind of forest is better for the climate?).

Al Goertzl, president of Seneca Creek (a shadowy corporation with a benign name that has no website and pumps out reports justifying the exploitation of forests) who is featured in MFA’s Faces of Forestry, wouldn’t know the difference, he identifies as a forest economist. In another publication marketing North American Forests he is credited with the statements: “There exists a low risk that U.S. hardwoods are produced from controversial sources as defined in the Chain of Custody standard of the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC).” and “The U.S. hardwood-producing region can be considered low risk for illegal and non-sustainable hardwood sourcing as a result of public and private regulatory and non-regulatory programs.” The report then closes with this shocker: “SUSTAINABILITY MEANS USING NORTH AMERICAN HARDWOODS.”

Why are forest-pimps conducting the risk assessment upon which future decisions critical to the long-term survival of our native ecosystem will be based? What is really going on here?

A noteworthy find from Forest2Market helps to clarify things:

“Europe’s largest single source of renewable energy is sustainable biomass, which is a cornerstone of the EU’s low-carbon energy transition […] For the last decade, forest resources in the US South have helped to meet these goals—as they will in the future. This heavily forested region exported over <7 million metric tons of sustainable wood pellets in 2021 – primarily to the EU and UK – and is on pace to exceed that number in 2022 (emphasis mine) due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, which has pinched trade flows of industrial wood pellets from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.”

Sustainability means using North American hardwoods.

If it has not yet become clear, the stakeholder consultation for the forest sustainability risk assessment document which inspired this piece was but a small, local, component of an elaborate sham enabling the world to burn and otherwise consume the forests of entire continents – in comfort and with the guilt-neutralizing reassurance that: carbon is captured, rivers are purified, forests are healthy and expanding, biodiversity is thriving and protected, and “the rights of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples are upheld” as a result of our consumption. (FSC-NRA-USA, p71) That is the first phase of the plan – manufacturing / feigning consent. Next the regulatory hurdles must be eliminated or circumvented. Cue the Landscape Management Plan (LMP).

“Taken together, the actions taken by AFF [American Forest Foundation] over the implementation period have effectively set the stage for the implementation of a future DBC project to promote and expand SDE+ qualifying certification systems for family landowners in the Southeast US and North America, generally.”

“As outlined in our proposal, research by AFF and others has demonstrated that the chief barrier for most landowners to participating in forest certification is the requirement to have a forest management plan. To address this significant challenge, AFF has developed an innovative tool, the Landscape Management Plan (LMP). An LMP is a document produced through a multi-stakeholder process that identifies, based on an analysis of geospatial data and existing regional conservation plans, forest conservation priorities at a landscape scale and management actions that can be applied at a parcel scale. This approach also utilizes publicly available datasets on a range of forest resources, including forest types, soils, threatened and endangered species, cultural resources and others, as well as social data regarding landowner motivations and practices. As a document, it meets all of the requirements for ATFS certification and is fully supported by PEFC and could be used in support of other programs such as other certification systems, alongside ATFS. Once an LMP has been developed for a region, and once foresters are trained in its use, the LMP allows landowners to use the landscape plan and derive a customized set of conservation practices to implement on their properties. This eliminates the need for a forester to write a complete individualized plan, saving the forester time and the landowner money. The forester is able to devote the time he or she would have spent writing the plan interacting with the landowner and making specific management recommendations, and / or visiting additional landowners.

With DBC support, AFF sought to leverage two existing LMPs in Alabama and Florida and successfully expanded certification in those states. In addition, AFF combined DBC funds with pre-existing commitments to contract with forestry consultants to design new LMPs in Arkansas and Louisiana. DBC grant funds were used to cover LMP activities between July 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018 for these states, namely stakeholder engagement, two stakeholder workshops (one in each state Arkansas and Louisiana) and staffing.” (American Forest Foundation, 2, 7).

It is clear that global interests / morally bankrupt humans have been busy ignoring the advice of scientists, altering definitions, removing barriers to standardization / certification, and manufacturing consent; thus enabling the widespread burning of wood / biomass (read: earth’s remaining forests) to be recognized as renewable, clean, green-energy. Imagine: mining forests as the solution to deforestation, biodiversity loss, pollution, climate change, and economic stagnation. Meanwhile, mountains are scalped, rivers are poisoned, forests are gutted, biological diversity is annihilated, and the future of all life on earth is sold under the guise of sustainability.

Sustainability means USING North American hardwoods!

The perpetual mining of forests is merely one “natural climate solution” promising diminishing returns for Life on earth. While the rush is on to secure the necessary public consent (but not of the free, prior, and informed variety) to convert the forests of the world into clean energy (sawdust pellets) and novel materials, halfway around the planet and 5 kilometers below the surface of the Pacific another “nature based solution” that will utterly devastate marine ecosystems and further endanger life on earth – deep sea mining (DSM) – is employing the same strategy. Like the numerous other institutions that are formally entrusted with the protection of forests, water, air, biodiversity, and human rights, deep sea mining is overseen by an institution which has contradictory directives – to protect and to exploit. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has already issued 17 exploration contracts and will begin issuing 30-year exploitation contracts across the 1.7 million square mile Clarion-Clipperton zone by 2024 – despite widespread calls for a ban / moratorium and fears of apocalyptic planetary repercussions. After decades of environmental protection measures enacted by thousands of agencies and institutions throwing countless billions at the “problems,” every indicator of planetary health that I am aware of has declined. It follows, then, that these institutions are incapable of exercising caution, acting ethically, protecting ecosystems, biodiversity or indigenous peoples, holding thieves, murderers and polluters accountable, or even respecting their own regulatory processes. Haeckel sums up industry regulation nicely in a recent nature article regarding the nascent DSM industry:

“…Amid this dearth of data, the ISA is pushing to finish its regulations next year. Its council met this month in Kingston, Jamaica, to work through a draft of the mining code, which covers all aspects — environmental, administrative and financial — of how the industry will operate. The ISA says that it is listening to scientists and incorporating their advice as it develops the regulations. “This is the most preparation that we’ve ever done for any industrial activity,” says Michael Lodge, the ISA’s secretary-general, who sees the mining code as giving general guidance, with room to develop more progressive standards over time.

And many scientists agree. “This is much better than we have acted in the past on oil and gas production, deforestation or disposal of nuclear waste,” says Matthias Haeckel, a biogeochemist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany.” (Seabed Mining Is Coming — Bringing Mineral Riches and Fears of Epic Extinctions).

Of course, this “New Deal for Nature” requires “decarbonization” while producing billions of new electric cars, solar panels, wind mills, and hydroelectric dams. The metals for all the new batteries and techno-solutions have to come from somewhere, right? According to Global Sea Mineral Resources:

“Sustainable development, the growth of urban infrastructure and clean energy transition are combining to put enormous pressure on metal supplies.

Over the next 30 years the global population is set to expand by two billion people. That’s double the current populations of North, Central and South America combined. By 2050, 66 percent of us will live in cities. To support this swelling urban population, a city the size of Dubai will need to be built every month until the end of the century. This is a staggering statistic. At the same time, there is the urgent need to decarbonise the planet’s energy and transport systems. To achieve this, the world needs millions more wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicle batteries.

Urban infrastructure and clean energy technologies are extremely metal intensive and extracting metal from our planet comes at a cost. Often rainforests have to be cleared, mountains flattened, communities displaced and huge amounts of waste – much of it toxic – generated.

That is why we are looking at the deep sea as a potential alternative source of metals.”

(DSM-Facts, 2022).

Did you notice how there is scarcely room to imagine other possibilities (such as reducing our material and energy consumption, reorganizing our societies within the context of our ecosystems, voluntarily decreasing our reproductive rate, and sharing resources) within that narrative?

Do you still wonder why the processes of approving seabed mining in international waters and certifying an entire continent’s forests industry to be sustainable seem so similar? They are elements of the same scheme: a strategy to accumulate record profits through the valuation and exploitation of nature – aided and abetted by the non-profit industrial complex.

“The non-profit industrial complex (or the NPIC) is a system of relationships between: the State (or local and federal governments), the owning classes, foundations, and non-profit/NGO social service & social justice organizations that results in the surveillance, control, derailment, and everyday management of political movements.

The state uses non-profits to: monitor and control social justice movements; divert public monies into private hands through foundations; manage and control dissent in order to make the world safe for capitalism; redirect activist energies into career-based modes of organizing instead of mass-based organizing capable of actually transforming society; allow corporations to mask their exploitative and colonial work practices through “philanthropic” work; and encourage social movements to model themselves after capitalist structures rather than to challenge them.” (Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex | INCITE!).

The emergence of the NPIC has profoundly influenced the trajectory of global capitalism largely by inventing new conservation and the youth climate movement –

The “movement” that evades all systemic drivers of climate change and ecological devastation (militarism, capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, patriarchy, etc.). […] The very same NGOs which set the Natural Capital agenda and protocols (via the Natural Capital Coalition, which has absorbed TEEB) – with the Nature Conservancy and We Mean Business at the helm, are also the architects of the term “natural climate solutions”. (THE MANUFACTURING OF GRETA THUNBERG – FOR CONSENT: NATURAL CLIMATE MANIPULATIONS [VOLUME II, ACT VI]).

In the words of artist Hiroyuki Hamada:

“What’s infuriating about manipulations by the Non Profit Industrial Complex is that they harvest the goodwill of the people, especially young people. They target those who were not given the skills and knowledge to truly think for themselves by institutions which are designed to serve the ruling class. Capitalism operates systematically and structurally like a cage to raise domesticated animals. Those organizations and their projects which operate under false slogans of humanity in order to prop up the hierarchy of money and violence are fast becoming some of the most crucial elements of the invisible cage of corporatism, colonialism and militarism.” (THE MANUFACTURING OF GRETA THUNBERG – FOR CONSENT: THE GREEN NEW DEAL IS THE TROJAN HORSE FOR THE FINANCIALIZATION OF NATURE [ACT V]).

We must understand that the false solutions proposed by these institutions will suck the remaining life out of this planet before you can say fourth industrial revolution.

“That is, the privatization, commodification, and objectification of nature, global in scale. That is, emerging markets and land acquisitions. That is, “payments for ecosystem services”. That is the financialization of nature, the corporate coup d’état of the commons that has finally come to wait on our doorstep.” (THE MANUFACTURING OF GRETA THUNBERG – FOR CONSENT: NATURAL CLIMATE MANIPULATIONS [VOLUME II, ACT VI].

An important point must never get lost amongst the swirling jargon, human-supremacy and unbridled greed: If we do not drastically reduce our material and energy consumption – rapidly – then We (that is, all living beings on the planet including humans) have no future.

In summary, decades of social engineering have set the stage for the blitzkrieg underway against our life-giving and sustaining mother planet in the name of sustainability industrial civilization. The success of the present assault requires the systematic division, distraction, discouragement, detention, and demonization (reinforced by powerful disinformation) and ultimately the destruction of all those who would resist. Remember also: capital, religion, race, gender, class, ideology, occupation, private property, and so forth, these are weapons of oppression wielded against us by the dominant patriarchal, colonizing, ecocidal, empire. That is not who We are. Our causes, our struggles, and our futures are one. Unless we refuse to play by their rules and coordinate our efforts, We will soon lose all that can be lost.

Learn more about deep sea mining (here); sign the Blue Planet Society petition (here) and the Pacific Blue Line statement (here). Tell the forest products industry that they do not have our consent and that you and hundreds of scientists see through their lies (here); divest from all extractive industry, and invest in its resistance instead (here). Inform yourself, talk to your loved-ones and community members and ask yourselves: what can we do to stop the destruction?

All flourishing is mutual. The inverse is also true.

“…future environmental conditions will be far more dangerous than currently believed. The scale of the threats to the biosphere and all its lifeforms—including humanity—is in fact so great that it is difficult to grasp for even well-informed experts […] this dire situation places an extraordinary responsibility on scientists to speak out candidly and accurately when engaging with government, business, and the public.” – Top Scientists: We Face “A Ghastly Future”

—Austin is an ecocentric Appalachian ethnobotanist, gardener, forager, and seed saver. He acknowledges kinship with and responsibility to protect all life, land, water, and future generations—

Banner photo by Rachel Wente-Chaney on Creative Commons

by DGR News Service | May 6, 2022 | ANALYSIS, Listening to the Land, Male Supremacy

Editor’s note: Writing from the mountains of Kerala, rewilder and restorationist Suprabha Seshan explores the pandemic and the war of patriarchy vs. the planet. “It is my sworn mission to salvage the ones burned, maimed, poisoned or reconstituted from the living earth by the fires of industrial civilisation,” she writes. This essay was first published in Turkish in Jineoloji magazine, a publication of the women’s movement of Kurdistan.

The Covid-19 pandemic, lethal as it is, is instrumental to capital’s assault on the living world. Looming through the terrors unleashed by free-flying strands of DNA are gargantuan infrastructural projects, including medical, green and digital. These are intent on destroying the web of life. Out of this extermination project, will spew more illnesses, disorders, infections, infestations, and devastations.

I urge us to address the relation between the militarised-capitalist-supremacist mindset and the living body of the earth. The latter includes you and me, our beloved human families, friends, communities and peoples, and also our non-human kith and kin. In this essay, I refer to the former as The Patriarch.

~~~

An active extermination event is at large, distinct from previous mass deaths of species through passive geologic processes. The current event involves slavery, ecocide and genocide. To understand Covid-19 while this is going on, would be like trying to understand a friend or family member’s 0.05% chance of dying from a natural ailment, when there is a psychopath with a shotgun in the room.

Domination, disorder, disease, debilitation, torture, slavery, unhappiness, fear, addictions, death and decay are essential for The Patriarch. Assembled from the reconstituted bodies of the living world, with extermination intrinsic to his existence, he will not stop until he consumes all. Ecocide and genocide are his mission.

The fundamental driving force of capital, I believe, is the imperative to conquer all life (including human bodies, hearts and minds). Unless this is negated, we cannot nurture the more subtle aspects of the enduring relationships between humankind and other-than-humankind.

While The Patriarch reduces many persons to touchscreen modalities, he confines and debilitates others. He even suffocates entire populations in the gas chambers of modern civilisation – the polluted cities – and burns others in wastelands resulting from the furnaces of his industries.

This kind of extermination has been going on for a while, perhaps since about 1492 when Europeans gifted smallpox wrapped in blankets to native Americans. Some people think it began way before, during the birth of civilisations – of militarised-hierarchical-extractive entities distinct from the myriad small cultures growing slowly over millennia in sustaining land bases. I find the nature of capital, particularly technocratic-militarised capital, egregious to a new extreme. The Patriarch is insatiable. I also believe he is insane. He has begun to devour his own body.

~~~

I am a conservationist living in a community in the rainforests of the Western Ghat mountains in southern India. I protect endangered species, restore rainforest habitat, and educate youth. We are many women in this place. Together with the men who also live and work here, we have an intimate knowledge of the plants and animals who create this biome, who are all sovereign beings in their own right.

These non-humans – or other-than-humans – also give us our foods and medicines, our ecologies and cultures, our material and immaterial bases. In return we try to protect them, nurture them, and see them through these terrible apocalyptic times. Together we work on a collective ecology, acknowledging our inseparableness from each other in the web of life. We are deeply intertwined through our physical beings: our cells, juices and tissues, our senses, limbs and nerves, and every organ and follicle. Through our bodies we create cultures, biomes and ecospheres. All these are being exterminated by the toxic forces of technologised-capitalistic patriarchy.

It is indeed my deep and fervent wish to examine the work of an unsee-able, unknow-able micro-being on humans. But I believe this will never be wholly known, and certainly not in a reductive way. Reciprocal mutualistic relationships rooted in interbeing grow in intimacy while remaining free and wild. They are like a dance between creatures – between men, women and others; adults and children; humans and nonhumans; between plants, animals, fungi, clouds, winds, rain, rocks, mountains, algae, forests, grasslands and oceans. This mutualism includes viruses, and the SARS-CoV-2 virus, too.

However, I believe the pandemic needs to be examined in the infernal light of omnicide (planetary to cellular). We cannot afford to ignore the background to the viral outbreak. We cannot forget the various “cides” that are going on – ecocide, gynocide, bactericide, fungicide, vermicide, infanticide, weedicide, genocide, climate-cide – and even cosmocide, the destruction of a cosmic body, the planet.

We are not at the beginning of a catastrophe, as the climate-mongers will have us believe. Rather, we are already towards the end of an altogether incomprehensible horror. The orchestration of capital through this pandemic threatens further the direct perception of The Patriarch’s endgame. He wreaks further havoc on his hapless slaves through various fear tactics. He exerts his enormous machines on all his subjugates such as indigenous peoples, marginalised classes, races and castes, women and children. He deploys them on the last forests, waters, winds and habitats. All the above, human and non-human, are swept under the rubric of “resources to be managed”. He also invents new enemies from the very body of the earth which sustains him, like the SARS Corona Virus.

~~~

As an ecologist serving the rainforests of the Western Ghats, it has been my lifelong enquiry to look at how a biome can recover from assault – from colonial-neocolonial-capitalistic-civilisational assault. I know, and the biome knows, that it can heal from most travesties and injuries, and that it will do its utmost to replenish itself and the planet. But the opposing faction, which for the moment we are calling The Patriarch, is gathering momentum. For the arsenal he has accrued – an arsenal built and assembled from the living body of the planet – is in fact, simultaneously disassembling, as he is now also turning on himself. He is running out of other resources.

In this utter disconnect, a monstrous creature devouring himself, he further debilitates humans and non-humans and the living community of earthly existence. He is not open to reason, though he sounds like he is. Nor is he open to life, though he needs it and appropriates it, particularly its very metabolic and life-engendering powers. Saying he is allied to the natural world, he severs himself from it in manifold ways. It doesn’t take much to see that The Patriarch’s language alienates him from his own body, and the body of the earth and the people. His actions separate him more and more from humans and non-humans, without whom he would perish in an instant.

There is no doubt, for me, that The Patriarch’s machinery must stop. My sincere observation is that only non-humans will stop him. Humans are at a gun point more insidious than what non-humans face. Non-humans are not hooked as humans are to The Patriarch. None of the other species – the ones within us and the ones without, those who inhabit our human bodies (the micro-biomes and macro-biomes without whom we could not even have a so-called human existence), and those whose bodies within which we dwell – none are dependent on him. They don’t need him for anything.

~~~

As of this writing, 0.05% of the human population has died from Covid, according to the WHO. The BBC news earlier this week said another half-million people in Europe will die by next year, unless vaccinated. If the data are to be believed, and if the projections are to be trusted, perhaps 5 million people will die altogether from Covid-19. We must do everything to prevent such a terrible thing. Of course. But, critical to recovery of humankind from its various acute and chronic ailments is a return of habitat, of clean air, and clean water, and nature-based relationships for humans to dwell amongst. The cleansing of lungs and livers and other organs, the opening of the senses, and the revival of rivers and wetlands, oceans and aquifers, and the vast ancient forests and human-non-human relations requires The Patriarch to be stopped. Humans are more dependent on all these than we are on The Patriarch. Whom to choose? The Patriarch, or life?

~~~

I’ve heard it said that the virus has no moral brief, but the starker reality is that it carries with it a potent ecological brief, a message saying that unless the world is fecund again, pandemics will speed up the obliteration of the human species, itself a marvelous creation of nature, already weakened by war, by generations of slavery to capital, by poison and dead-numbing effects of digital weaponry, radiation, forced migration, wage slavery, mental anguish and terrible violence on women, children, people of colour and indigenous peoples – all required by The Patriarch as cogs in his capitalist-industrial-technocratic machine.

~~~

The virus, invented in a laboratory or not, is a biological entity that enters human bodies, causes symptoms as it goes about its own mission, propagating itself, tangling with host genomes, creating new conditions, challenging us in its own way, and like any infection, or deemed infection, it pushes our immune systems. Other viruses create other conditions, many of which are beneficial. Overall, the benefits outweigh the diseases.

The virome consists of vast assemblages of viruses in each and every body, habitat and biome. It surrounds us, fills and subsumes our every thought, breath and action. Viruses are the most abundant biological entities on earth. They make us who we are. Like with every aspect of the living cosmos, much of what happens is beneficial, and viral life seems to beget more life, creating our genetic identities. Evolutionary studies show that all life begets more life, despite the occasional disruption or cataclysmic event.

~~~

If invented, then the virus is not different from other invented beings, like dog breeds, plant breeds and even the eugenist caste creations, where, through exercise of a supremacist caste or class’s control, another caste or class or creature’s love, life and passions are harnessed, culled, consumed, engineered, enslaved, extorted, and artifacted to serve the supremacist project (factory farms, factory labour, pet industry, plant industry, monoculture agriculture, industrial fishery, dams-on-rivers, humans-in-slums, human trafficking, domestic labour, untouchable peoples and many more forms of subjugation).

~~~

Domesticated dogs go feral sometimes. They attack people sometimes. The dogs get impounded, spayed or killed, and there is a furor for a while. Domesticated plants go feral sometimes, usually after generations of breeding and enslavement, or after a natural disaster, like a volcanic explosion, or the desertification caused by modern civilisation. They, too, seem to invade territories controlled by humans for other purposes, including other plants deemed more useful. The new problem plants get weedicided, eradicated, and turned into biomass for some other project. This phenomenon gets new names, such as “the science and practice of invasion biology.”

Humans too, go feral, sometimes. They try to take back the control and agency they were systematically denied. They become targets of world leaders and other supremacists.

Now the virus is going feral. Viral. The solutions to this are confinements, containments, fear-mongering and authoritarian technics such as lockdowns and mandates regarding vaccines.

In all these instances, the aggressors, the hosts, the pathogens and the victims are actually contingent to the projects of The Patriarch. Besides, we all know that this virus and its quick evolving progeny can beat any vaccine. We all know The Patriarch needs the virus, the vaccines and human beings.

The Patriarch needs life for all his projects. It is his own dependency on human and non-human others, that he hates more than anything else. Would that we were all machines! He would not be so burdened, guilty, tormented. Machines can be turned on and off, in an instant.

~~~

During the lockdowns, the stopping of vehicles affected every human and non-human. A great number of humans were corralled in. There was no traffic. Other humans and non-humans surged onto streets. The exuberance of the latter offset the tragedy of the former (people desperate to get home). Many studies show that when air, water and land traffic stopped, biodiversity increased in most areas. This was true in our home in the Western Ghats too. Freshwater life had a reprieve from the pesticides washing into the streams and rivers. Insects bred unhindered by insecticides (momentarily unavailable because of the collapse of supply chains). Everywhere, people started gardening in balconies and yards, while others returned to hunting and foraging. Although this hurt some non-humans, overall, it was a return to another kind of life, and a far more direct existence. In the forest, friends reported seeing animals come closer, and they also reported some increase in illegal hunting. Men forced to take to the gun instead of the shopping bag. Men have always hunted for food. Now this ancient way of living is illegal only because The Patriarch legitimises another kind of degradation; the devouring of the land by his forces to feed his industrial systems and machines, including the slaves that work them and now wholly depend on them.

Actual human impact on this forest, man to tree, man to river, women to plants, people to the commons, is minimal compared to the post-Hiroshima assault on the whole biome. We cannot equate hand to hand combat to the unleashing of a nuclear or chemical arsenal, like Round up or Endosulfan or Agent Orange. Or the arsenal of earth-moving machinery.

~~~

I’ve heard that whales could once again hear each other sing underwater during the lockdowns, because of the reduction in ocean traffic. Friends say Olive Ridley turtles increased in certain coastal areas for a brief period, because of a near complete halt in trawling and netting. Air pollution dropped because of the grounding of aircraft, and great murmurations of birds could fly freely without hindrance from war planes and cargo planes and passenger planes. I know from my personal experience that I could walk through the streets of Bangalore without my eyes smarting from pollution, and I saw more birds and butterflies in the city than ever before. The resilience of life is obvious. It’s possible to see what it is capable of all the time.

I know the resilience of my own body, of human beings, non-human beings and of the great earth herself.

~~~

The increase in human numbers by over 4% in this same period overshadows the effect of one life form on another, but is not mentioned. However, human will is even more broken and hijacked by the Patriarch’s projects, by capitalism. Furthermore, the increase in other kinds of machines, industrial infrastructure and invasive medicine (all wreaking ecocide or genocide somewhere in the world) pales, in turn, the effect of the increase in human numbers, and even more the effect of one little, invisible life form on some of humankind.

I also heard that young people turned suicidal, and that mental illness rose during this great human confinement, another term for the lockdowns. Already estranged from the rest of the cosmos, modern humans are even more lonely. Indigenous people know the antidotes to loneliness and breakdown are communities of humans and non-humans. The Patriarch and his henchmen divide millions more from their loved ones while they live and also while they die. I cannot think of anything more terrifying than this.

~~~

As a rainforest activist, it is my daily work to find alliance amongst humans and non-humans to stop further assault. This is no simple task, as most humans see the so-called benefits of capitalism as great, and that life has never been so good. The assault on their bodies through the toxification of the environment, which has led to severely compromised immune systems – a necessary precondition for new diseases to run rife – is unperceivable, because of clever filters in place, addictions, and the numbing effects of petroleum-based lifestyles. Most people are hooked to modern capitalistic systems as providers of life, healers of disease and rescuers from death. A capitalist technocrat is like God. He is a life-giver and a death-controller. He can also assuage, deprive, save, confine and kill in the name of God, or science, for whatever he considers to be the greater common good. To which we are all subject. To which we cannot say no. This great hijacking of the human will is the horrific achievement of the pandemic.

So I seek alliance amongst those not yet wholly hijacked.

~~~

As a rewilder and restorationist, it is my sworn mission to salvage the ones burned, maimed, poisoned or reconstituted from the living earth by the fires of industrial civilisation. My friends, comrades and I run refuges for non-humans, and also humans. We see the need for safe houses, halfway homes, and intensive care units for our plant and animal kith and kin, and also for women, children, marginalised and indigenous peoples, and anyone wishing to break free from The Patriarch’s projects. We need every possibility to regroup and re-enter relationships where humans and non-humans can support each other, so that we may resist the last onslaughts. I find rewilding to be a worthy vocation.

As a member of the web of life, of the still substantial community of life, I try to unravel the effects of one member of this community, the virus, on another member of this same community, the human being. Unfortunately, without addressing the mission of The Patriarch, of omnicidal capital, we cannot examine our true relations with our non-human kith and kin.

~~~

Humans are slaves to The Patriarch. So is the great planet with its winds and lands and waters with trees and elephants and butterflies. So are the forests of my region. The Patriarch needs us alive and needs us dead for his project. It’s a real question how liberation will come. With a domination imperative unique in the entire life of the cosmos, he needs dead wood and living wood and feral wood (ecosystem services of forests). He needs dead water and living water and feral water (for irrigation, tidal and hydropower). He needs dead wind and living wind and feral wind (for air-conditioning, ventilators and turbines). He needs dead plants and animals and living plants and animals and feral plants and animals (for food and medicines and now for climate-saving biodiversity). Now he even needs dead fungi and living fungi and feral fungi (for more biodiversity). He needs dead viruses and living viruses and feral viruses (for evolution and now for vaccines and the great global reset). He needs dead humans, and living humans and feral humans (for research, trade, war and terrorism and slavery).

~~~

I see Covid-19 as a project of The Patriarch, of supremacist powers in the ruling class destroying people and saving people. Our lives are clenched in their hands. They have become the arbiters of human-non-human community, of the very web of existence. They give life, and they take away the foundation of life, through creating new hooks and needs. At the same time they destroy genuine relationships and our capacity to remember what the land was once like. However, because life is as powerful as it is, and because the forests are as resilient and fecund as they are, the world leaders and technocrats aim to harness life’s myriad powers for their projects. Where before they sought land, spices, plants, animals and slaves from the global South, and wood, water and minerals, now they hunt ecosystems and planetary forces (tides, sunshine, clouds, biomes (evolution itself) and slaves everywhere. It is the exuberance and wholeness of life that they seek to devour to fuel their existence.

~~~

I am witness to the land coming alive every moment of every day, so I know the full powers of life are still working. Life’s fecundity is unstoppable, it surges under every type of condition. Like the pigs in factory farms who have babies under impossible conditions, or men and women growing families during war, or forests having baby forests even when the whole climate is shifting, life creates life all the time and everywhere. The ever-entwining forests and winds and waters, with their immense creative forces, both tantalise and threaten The Patriarch, because life achieves with joy and felicity what he cannot ever do. He cannot create life yet, he can only try to force it to create itself. Whether under gun point or nuclear blasts, or dioxins in the cell of every creature, life is the regenerative force he wishes to tap into. Genetic and geologic engineering are only steps along the way.

~~~

I, too, am a creature of nature. Endowed with a particular passion, a wonderment of what this alive, half-alive, wild, half-wild, feral, domesticated, enslaved, tortured way of existence is. Aware that I am a part of all this through my body, my mind, my senses and other faculties, I experience inter-being in everything I do, everything I am, in every aspect of my body-being. I cannot even call it mine, as I feel the work of the forest through the lungs, and the skin and the gut and the mind of this body, itself a biome of sorts. This is the awakening from the nightmare that happened after some years of living here. I came alive to the undeniable truth that we are all inextricably intertwined. That ecology is the non-negotiable, ever-vital matrix in which I am completely held. That I also take part in it, through every action, and non-action, even in my sleep and dreams. As I awoke to The Patriarch’s shadow project, I awoke to the natural world’s life engendering service. Ecology makes more of itself and lives and thrives upon itself. Capitalism, the latest and most devastating avatar of patriarchy, and of ego, makes more of itself and lives and feeds upon its now disassembling self.

~~~

The Patriarch forms himself not in the image of some god; he tries to gain advantage to himself through the exuberance of life. His ego needs our eco.

However, he is a toxic mimic, imitating the form of creation but not its content. He is bent on destruction; total annihilation.

Unlike life. She lives and thrives through community and love and joy and play and inter-being and fecundity and beauty.

~~~

In solidarity with Kurdish women in their extraordinary mission, and through these thoughts, joining the clarion call for Life to overrun the patriarch wholly: to dismantle every cog and wheel of his stupendous machine. Let’s unhinge him. Let’s ally with eco, not his insufferable ego!

Suprabha Seshan is a rainforest conservationist. She lives and works at the Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary, a forest garden and community-based conservation centre in the Western Ghat mountains of Kerala. Her essays can be found in The Indian Quarterly, The Indian Express, Scroll.in, Hard News, and Economic and Political Weekly. She is currently working on her book, Rainforest Etiquette in a World Gone Mad, forthcoming from Context, Westland Publishers. She is an environmental educator and restoration ecologist, an Ashoka Fellow, and winner of the 2006 Whitley Fund for Nature award.

by DGR News Service | May 22, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization

This is part 3 of a series that originally appeared on Climate and Capitalism. You can read part 1 and part 2.

Featured image: The Spanish Armada off the English Coast, by Cornelis Claesz. van Wieringen, ca. 1620

THE FIRST COD WAR

How England’s government-licensed pirates stole the Newfoundland fishery from Europe’s largest feudal empire

By Ian Angus

In 1575, a moderately successful Bristol merchant named Anthony Parkhurst purchased a mid-sized ship and began organizing annual cod fishing expeditions to Newfoundland. Unlike most of his peers, he travelled with the fishworkers; while they were catching and drying cod, he explored “the harbors, creekes and havens and also the land, much more than ever any Englishman hath done.” In 1578, he estimated that about 350 European ships were active in the Newfoundland cod fishery — 150 French, 100 Spanish, 50 Portuguese, and 30 to 50 English — as well as 20 to 30 Basque whalers.[1]

In fact, there were many more ships in the Newfoundland fisheries than that — sailing close to shore, Parkhurst apparently did not see the several hundred French ships that worked on the Grand Banks every year. Nevertheless, as historian Laurier Turgeon writes, his figures allow a comparison to the more famous treasure fleets that sailed from the Caribbean to Spain in the same period.

“Even if one accepts Parkhurst’s simplistic figures, the Newfoundland fleet — comprising between 350 and 380 vessels crewed by 8,000-10,000 men — could have more than matched Spain’s transatlantic commerce with the Americas, which relied on 100 ships at most and 4,000-5,000 men in the 1570s — its best years in the sixteenth century.…

“However approximate, these figures demonstrate that the Gulf of St. Lawrence was a pole of attraction for Europeans on a par with the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. Far from being a fringe area worked by only a few fishermen, the northern part of the Americas was one of the great seafaring routes and one of the most profitable European business destinations in the New World.”[2]

Despite the profits others made, Parkhurst found that “the English are not there in such numbers as other countries.” A decade earlier, he would have found far fewer. And yet, by 1600 the number of English ships that travelled annually to the Newfoundland fishery had more than tripled, while Spanish ships had all but disappeared. To understand how and why that happened, we must take a brief detour into European geopolitics.

England versus Spain

John Cabot had claimed the new land for England in 1497, but the government didn’t follow up, and few English merchants and fishers were interested. England’s internal market for fish was well served by cod from Iceland and herring from the North Sea, and the wealthy London merchants who dominated England’s foreign trade were conservative and resistant to change. As John Smith later wrote of English merchants’ reluctance to invest in American colonies where fishing was the major industry, they chose not to risk their wealth on “a mean and a base commoditie” and the “contemptible trade in fish.”[3]

The few English expeditions to Newfoundland before 1570 were organized by smaller merchants and shipowners who were not part of the London merchant elite: they sailed not from London or even Bristol, but from smaller ports in the West Country, the southwestern “toe” of England.

As a result, English ships in Newfoundland were substantially outnumbered by ships from continental Europe for most of the 1500s. This reflected the imbalance of power in Europe, where England was a minor country on the periphery, while Spain controlled an immense empire. After Spain annexed Portugal in 1581, the total capacity of its merchant ships was close to 300,000 tons, compared to England’s 42,000. Spain claimed, and could enforce, exclusive access to “all the areas outside Europe which seemed at the time to offer any possibility of outside trading.”[4]

But England’s economy was expanding, and a growing number of English entrepreneurs and adventurers sought to break Spain’s economic power, especially its domination of transatlantic trade. Between 1570 and 1577, for example, at least thirteen English expeditions challenged Spain’s monopoly by trading slaves and other commodities in the Caribbean.[5] Throughout Elizabeth I’s reign (1558–1603) the organizers and supporters of such ventures lobbied hard for what Marxist historian A.L. Morton called “a constant if unformulated principle of English foreign policy — that the most dangerous commercial rival should also be the main political enemy.”[6]

Economic rivalry was reinforced by religious conflict. England was officially Protestant, while Spain was not only Catholic, but home to the feared and hated Inquisition. When a Protestant-led rebellion against Spanish rule in the Netherlands broke out in 1566, Dutch refugees were welcomed in England, English supporters raised money to buy arms for the rebels, and wealthy English Calvinists organized companies of English soldiers to join the fight. Spanish officials, in return, actively supported efforts to overthrow Elizabeth and install a Catholic monarch. In 1570, Pope Pius V added to the conflict by excommunicating “the pretended Queen of England.” He ordered English Catholics not to obey Elizabeth, and declared that killing her would not be a sin.

Queen Elizabeth I

As the Marxist historian Christopher Hill wrote of conflicts in England in the next century, “whether we should describe the issues as religious or political or economic is an unanswerable question.”[7]

When Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558, Spain was the richest and most powerful country in Europe, and England was too weak to challenge it directly. Instead, Elizabeth surreptitiously supported a maritime guerilla war against Spain’s merchant ships and colonies, a freelance war for profit conducted by government-licensed raiders who paid their own expenses and kept most of what they stole. Such legal pirates were later dubbed privateers — I will use that term to distinguish them from traditional pirates, although in practice it was difficult to tell them apart.

Piracy had been endemic in England for centuries, especially on the southern coast; the pirates “were skilled sailors, organized in groups, and often protected by such influential landowning families as the Killigrews of Cornwall . … the risks of piracy were fairly low, the profits large.”[8] Many of the mariners who signed on as privateers in Elizabeth’s time had been pirates before, and would return to piracy when their privateering licenses expired. The successful ones were feted at court, and the most successful received knighthoods. If they were captured by Spanish officials, they faced execution as common pirates, but in England privateering was a respectable profession, dominated by “west country families connected with the sea, for whom Protestantism, patriotism and plunder became virtually synonymous.”[9]

In theory, privateers were licensed under an ancient law that permitted merchants to recover goods stolen by foreign vessels, but that was usually a legal fiction.

“The promoter of a venture had merely to perform a routine which amounted to buying a license from the Lord Admiral through his court. Many did not even bother with this formality, but obtained a private note from the Lord Admiral direct, or even sailed without license altogether, strong in the conviction that any objectors could be bought off in the unlikely event of a day of reckoning.”[10]

Promoters, usually ship owners, financed privateering ventures by selling shares to investors, who ranged from rich merchants and government officials to local tradesmen and shopkeepers. Ten or fifteen percent of the loot went to the crown, and the remainder was split three ways, between investors, the promoter, and the captain and crew.

While men from all classes took part, most privateering voyages in Elizabeth’s time were organized and led by men who were outside of London’s merchant elite. Most came from the West Country, home territory not only for pirates but for most of the English fishing expeditions to Newfoundland. A common theme in contemporary discussions of fishing was its importance as a training ground for the navy, but it was also a training ground for piracy. Historian Kenneth Andrews has shown that English merchant ships often engaged in both trading and raiding on the same voyages[11] so it would be surprising if some of the seafarers who carried fishers to Newfoundland didn’t also attack merchant ships, if only in the off-season.

Perhaps the most successful Elizabethan privateer was one-time slave trader Sir Francis Drake. He is best-remembered for circumnavigating the globe, but he did that not for the thrill of discovery, but to evade capture after he looted Spanish treasure ships on the coast of Peru. The booty he brought back earned his backers, including the Queen, an astonishing 4600% profit on their investment.

In Part Two, I quoted Perry Anderson’s description of Spain’s 16th Century plunder of gold and silver in Central and South America as “the most spectacular single act in the primitive accumulation of European capital during the Renaissance.”[12] The English campaign of licensed piracy during Elizabeth’s reign can be called primitive accumulation once-removed — some great capitalist fortunes originated as pirate booty, stolen from the thieves who stole it from the Aztecs and Incas.

Open war between England and Spain broke out in 1585, when Elizabeth publicly declared support for the Dutch rebels and officially sent soldiers to aid them. When Spain’s King Philip II responded by prohibiting trade with England and seizing English merchant ships in Spanish ports, Elizabeth encouraged privateers to increase their attacks on Spanish shipping, and Philip began planning a direct attack on England.

On May 30 1588, a fleet of 130 ships carrying 19,000 soldiers set out from Lisbon to invade England and overthrow Elizabeth. Two months later, the Great Armada was in disarray, soundly defeated by a smaller English force. Only 67 Spanish ships and fewer than 10,000 men survived.