Power Propaganda

How Electricity was (and is) Sold to America

By Elisabeth Robson / RadFemBiophilia’s Newsletter

In 1915, General Electric released a silent promotional film titled The Home Electrical offering a glimpse into a gleaming, frictionless future. The film walks viewers through a model electric home: lights flicked on at the wall, meals cooked without fire, laundry cleaned without soap and muscle. A young wife smiles as she moves effortlessly through her day, assisted by gadgets that promised to eliminate drudgery and dirt. This was not a documentary—it was a vision, a fantasy, a sales pitch. At the time, only a small fraction of American households had electricity at all, and nearly 90% of rural families still relied on oil lamps, wood stoves, hand pumps, and washboards. But the message was clear: to be modern was to be electric—and anything less was a kind of failure.

At the dawn of the 20th century, electricity was still a symbol of wealth, not a tool of survival. Most urban households that had it used it only for lighting; refrigeration, electric stoves, or washing machines were luxuries among luxuries. In rural America, most farms and small towns remained off-grid through the 1920s. The electric grid simply didn’t go there. Private utilities, driven by profit, had no interest in building costly infrastructure where it wouldn’t quickly pay off.

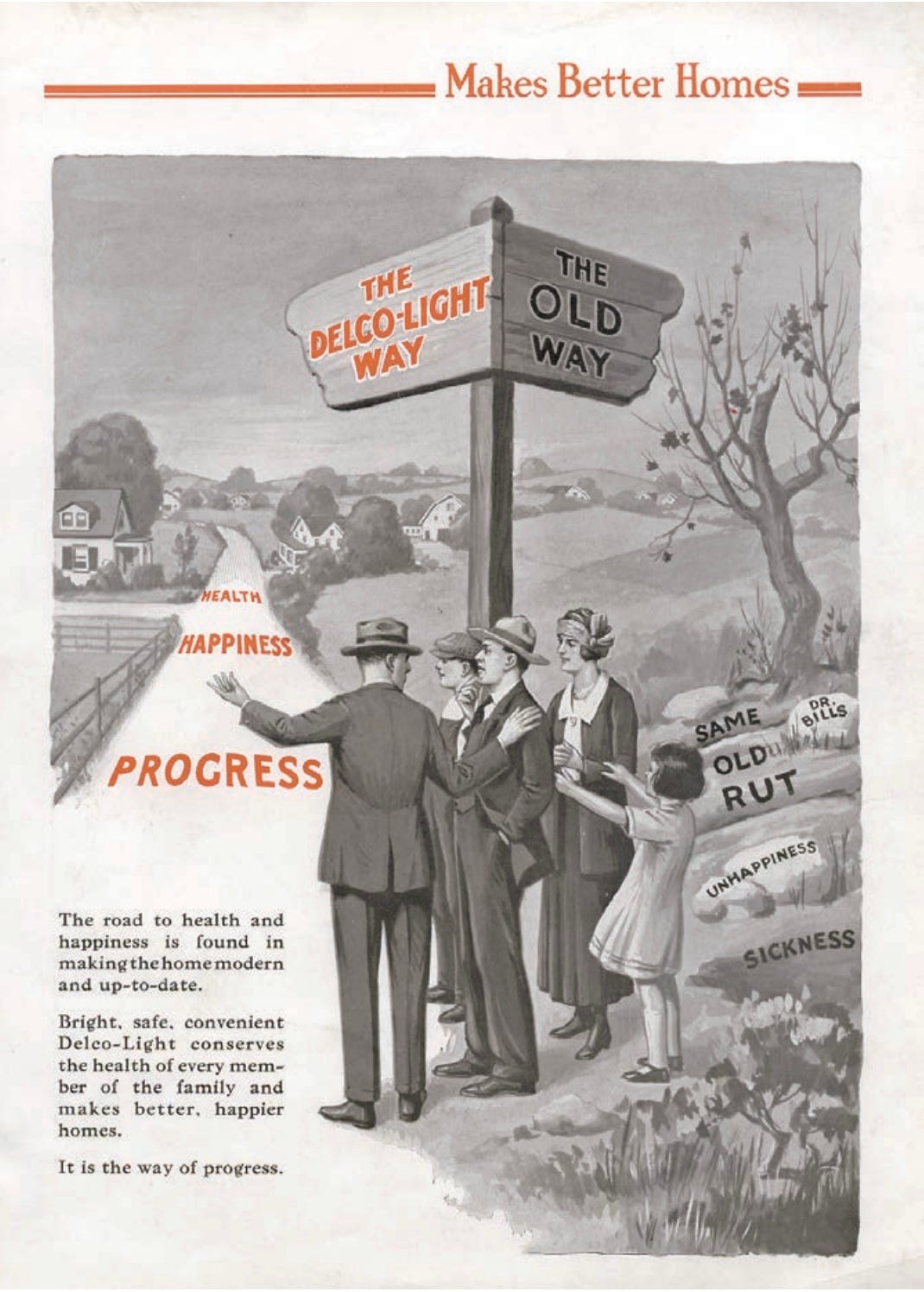

And yet, propaganda told a different story. In magazines, World’s Fairs, and promotional pamphlets, electricity was shown as the cornerstone of health, cleanliness, efficiency, and modern womanhood. Electric appliances promised to save time, reduce labor, and lift families—especially women—into the new century. But this future was just out of reach for most people. A growing divide opened up: between those who lived by the rhythms of sun and fire, and those whose lives were quietly reshaped by the flick of a switch.

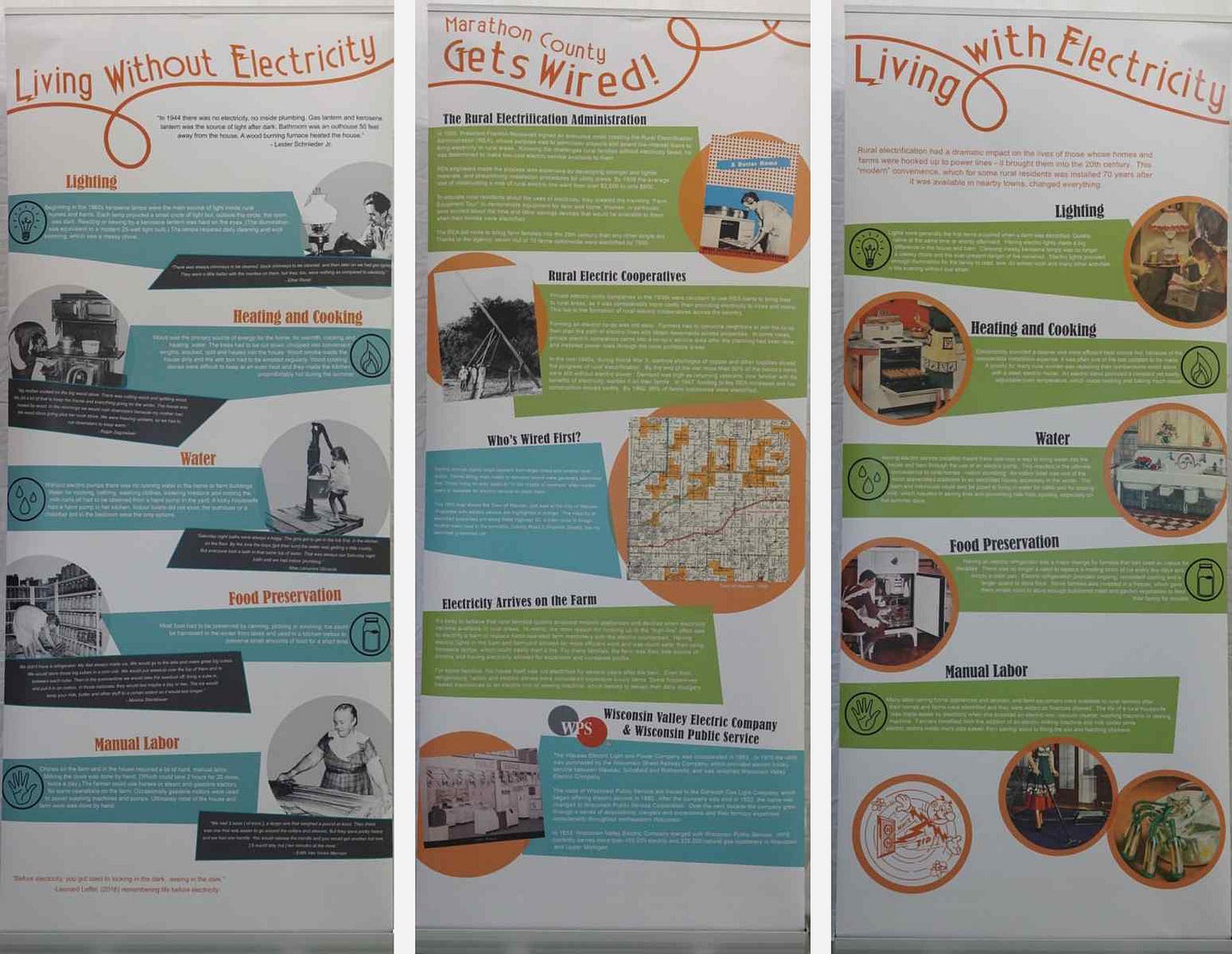

To live without electricity meant pumping water by hand, chopping and hauling wood for heat and cooking, cleaning clothes with a washboard, and preserving food with salt, smoke, or ice if you had it. It meant darkness after sundown unless you had oil or candles. These were difficult, time-consuming tasks—but also deeply embedded in older, place-based ways of life. People were less dependent on centralized systems. They mended clothes instead of buying new ones, and their food came from the land, not refrigerated trucks.

Yet the narrative of “progress” didn’t tolerate this complexity. By the 1920s and ‘30s, utilities and appliance manufacturers framed non-electric life as backward, dirty, and even unpatriotic. Their message: to be modern was to be electric.

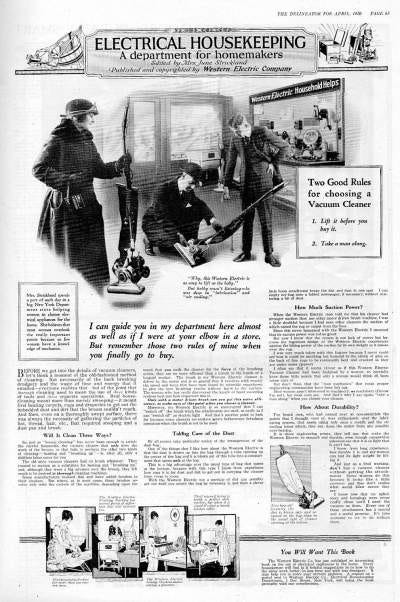

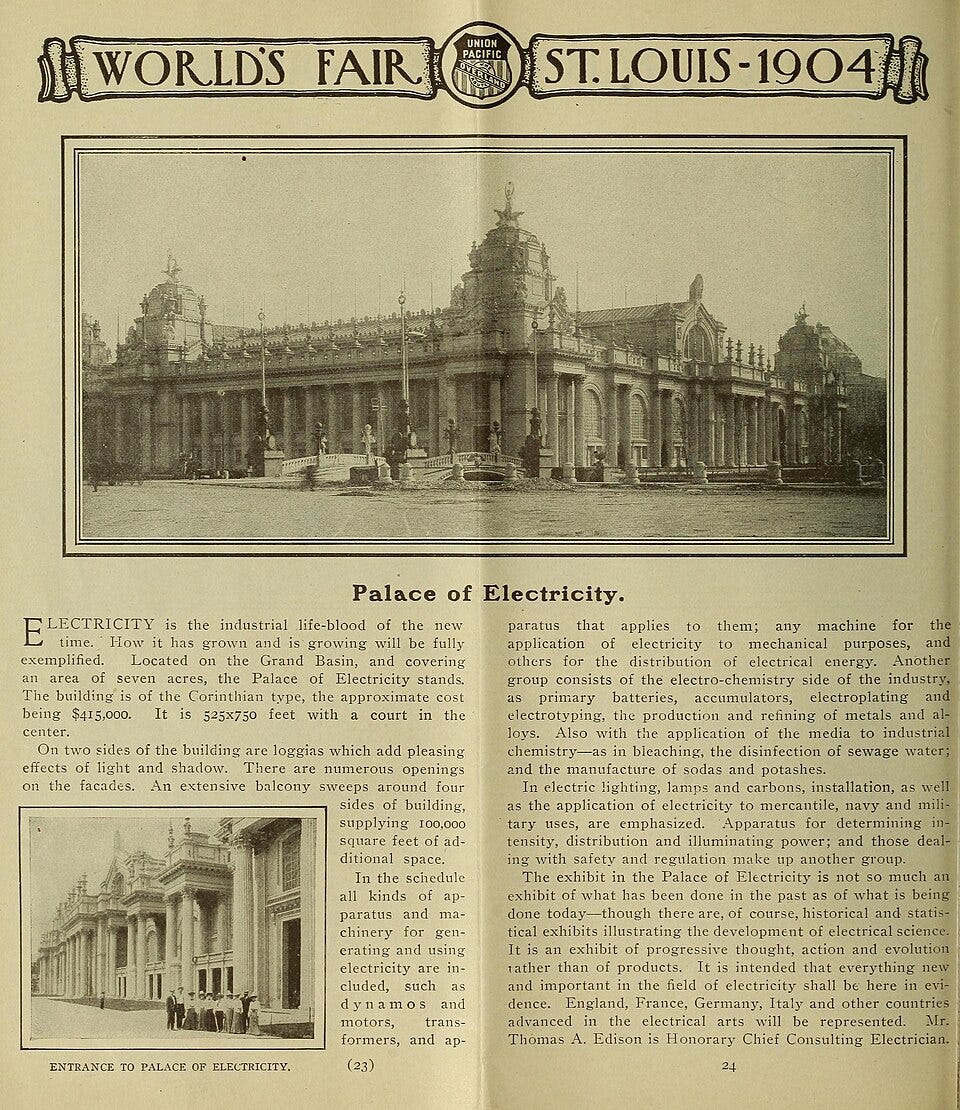

This vision of electrified modernity wasn’t just implicit; it was relentlessly promoted through the dazzling spectacles of world’s fairs and the persuasive language of print advertising. Electricity was framed not only as a technological advance but as a moral and social imperative—a step toward cleanliness, order, and even national progress. At places like the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, entire palaces were built to glorify electricity, their glowing facades and futuristic interiors turning utility into fantasy. Meanwhile, companies like Western Electric and General Electric saturated early 20th-century magazines with ads that equated electric appliances with a better life—especially for women. These messages didn’t merely advertise products; they manufactured desire, anxiety, and aspiration. To remain in the dark was no longer quaint—it was backward.

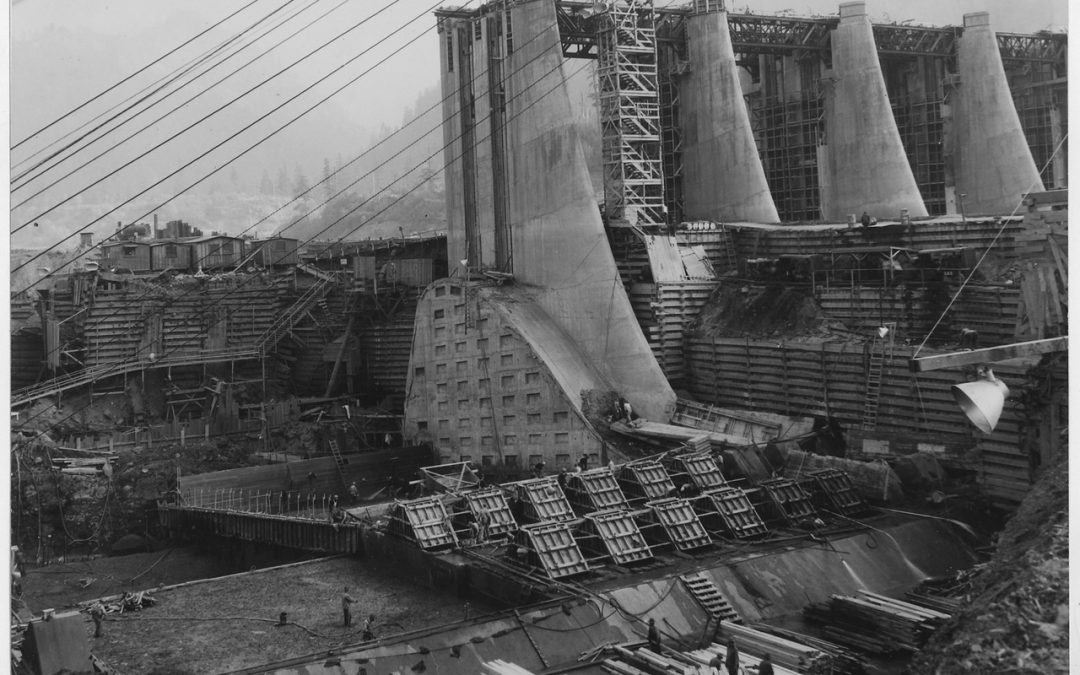

At the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, the Palace of Electricity was more than an exhibit—it was theater. Illuminated by thousands of electric bulbs, the building itself was proof of concept: a monument to the power and promise of electrification. Inside, visitors encountered displays of the latest electric appliances and power systems, all framed as marvels of human ingenuity. Nearby, the Edison Storage Battery Company showcased innovations in energy storage, while massive dynamos hummed behind glass. The fair suggested not just that electricity was useful, but that it was destiny.

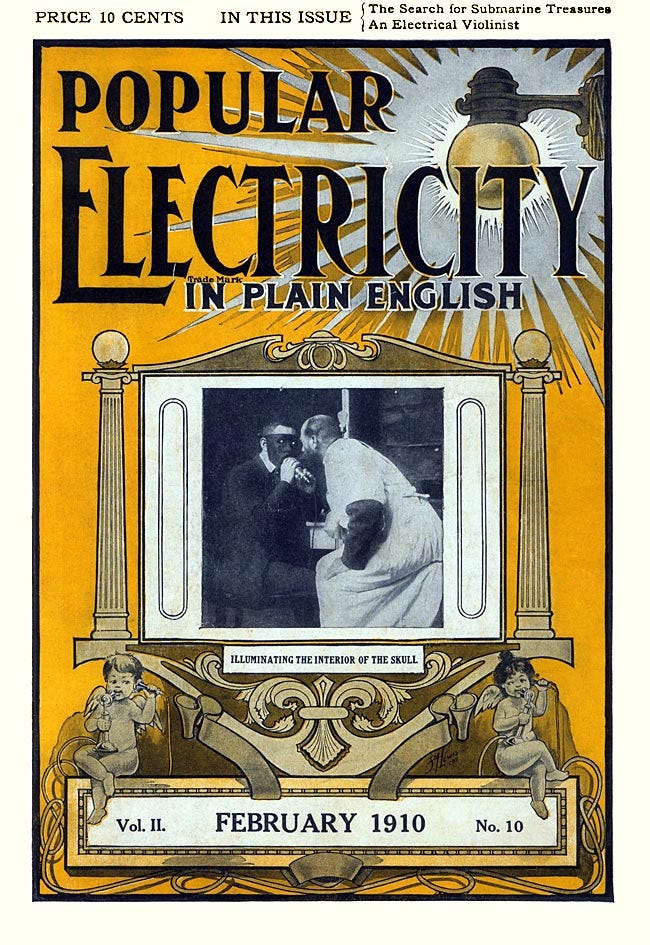

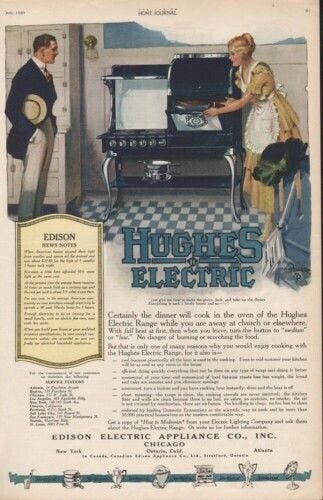

This theatrical framing of electricity as progress carried into everyday life through print advertisements. A 1910 issue of Popular Electricity magazine illustrated a physician using electric light in surgery, suggesting that even health depended on electrification. In a 1920 ad for the Hughes Electric Range, a beaming housewife is pictured relaxing while dinner “cooks itself,” thanks to the miracle of electricity. Likewise, a Western Electric ad from the same year explained how to build an “electrical housekeeping” system—one that offered freedom from drudgery, but only if the right appliances were purchased.

These messages targeted emotions as much as reason. They played on fears of being left behind, of being an inadequate housewife, of missing out on modernity. Electricity was no longer merely about illumination—it became a symbol of transformation. The more it was portrayed as essential to health, domestic happiness, and national strength, the more it took on the aura of inevitability. A home without electricity was not simply unequipped; it was a failure to progress. Through ads, exhibits, and films, electricity was sold not just as a convenience, but as a moral good.

And so the groundwork was laid—not only for mass electrification, but for the idea that to live well, one must live electrically.

Before the Toaster: Industry was the First Beneficiary of Electrification

While early 20th-century advertisements showed electricity as a miracle for housewives, the truth is that industry was the first and most powerful customer of the electric age. Long before homes had refrigerators or lightbulbs, factories were wiring up to electric motors, electric lighting, and eventually, entire assembly lines driven by centralized power. Electricity made manufacturing more flexible, more scalable, and less tied to water or steam—especially important in urban areas where land was tight and labor plentiful.

By the 1890s, industries like textiles, metalworking, paper mills, and mining were early adopters of electricity, replacing steam engines with electric motors that could power individual machines more efficiently. Instead of a single massive steam engine turning shafts and belts throughout a factory, electric motors allowed decentralized control and faster adaptation to different tasks. Electric lighting also extended working hours and improved productivity, particularly in winter months.

Electrification offered not just operational efficiency but competitive advantage—and companies knew it. By the 1910s and 1920s, large industrial users began lobbying both utilities and governments for better access to power, lower rates, and more reliable service. Their political and economic influence helped shape early utility regulation and infrastructure investment. Many state utility commissions were lobbied heavily by industrial users, who often negotiated bulk discounts and prioritized service reliability over residential expansion.

This dynamic led to a kind of two-tiered system: electrification for factories was seen as economically essential, while electrification for homes was framed as aspirational—or even optional. In rural areas especially, private utilities refused to extend lines unless they could first serve a profitable industrial customer nearby, like a lumber mill or mine.

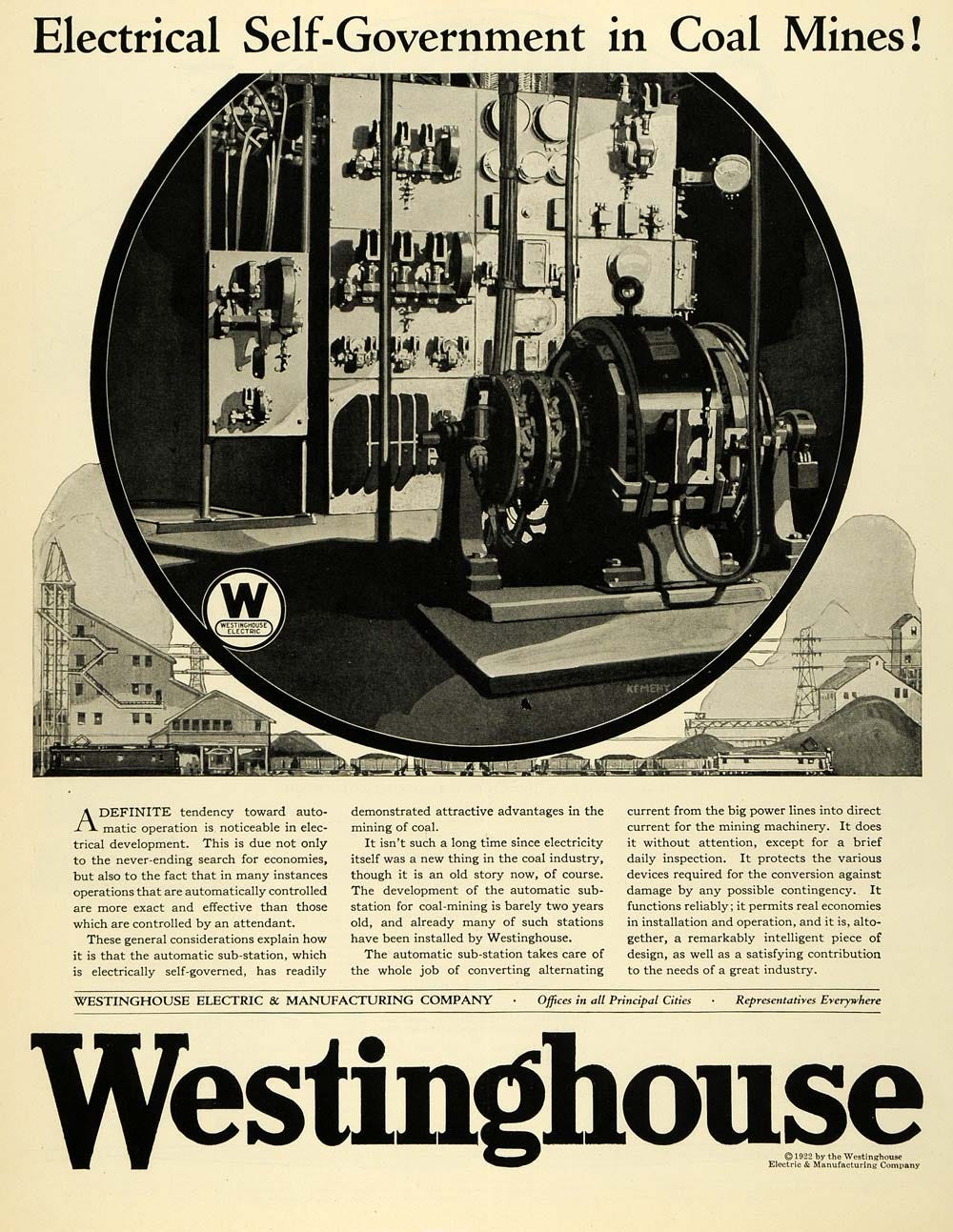

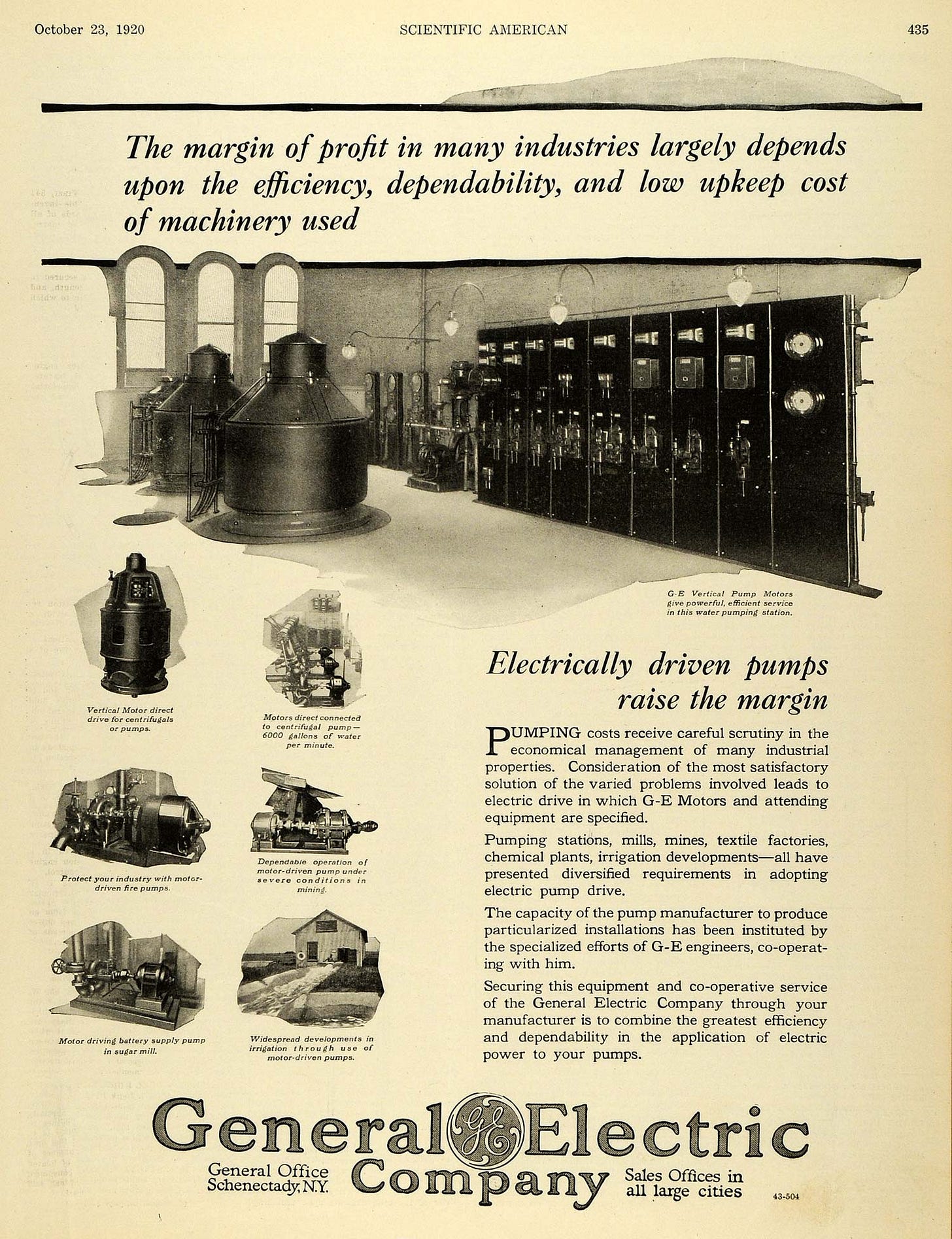

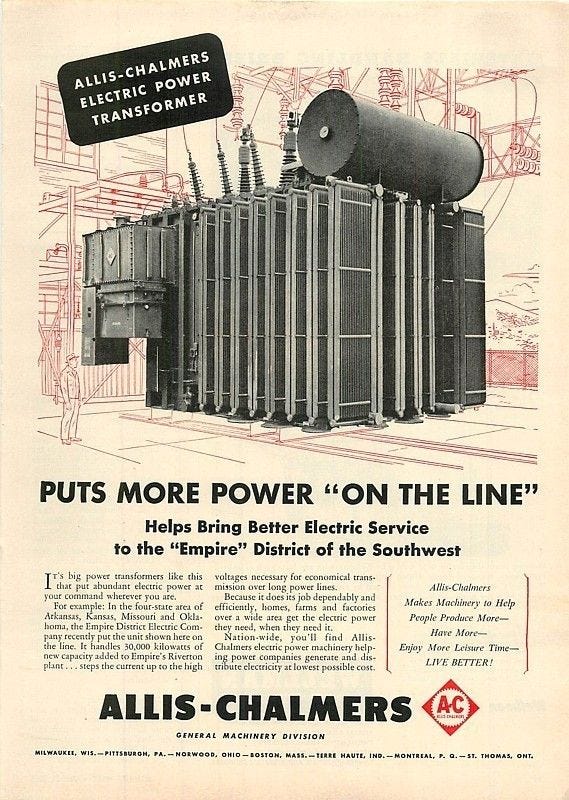

Meanwhile, companies that produced electrical equipment—like General Electric, Westinghouse, and Allis-Chalmers—stood to gain enormously. They pushed for industrial electrification through trade shows, engineering conferences, and direct lobbying. Publications like Electrical World and Power magazine ran glowing stories about new industrial applications, highlighting speed, productivity, and cost savings. GE and Westinghouse didn’t just sell light bulbs and home gadgets—they also built turbines, dynamos, and entire systems for industrial-scale customers.

And industry didn’t just demand electricity—industry helped finance it. Many early power plants, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast, were built explicitly to serve one or more large factories, and only later expanded to provide residential service. These plants often operated on a model of “load factor optimization”: power usage by factories during the day and homes at night ensured a steady demand curve, which maximized profits.

By the 1920s, the logic was clear: industry came first, homes came second—but both served the larger vision of an electrified economy. And this industrial-first expansion became one of the justifications for public electrification programs in the 1930s. If electricity had become so essential to national productivity, how could it remain out of reach for most rural Americans?

Niagara Falls Power Plant: Built for Industry

In 1895, the Niagara Falls Power Company, led by industrialist Edward Dean Adams and with technological help from Westinghouse Electric and Nikola Tesla, completed the Adams Power Plant Transformer House—one of the first large-scale hydroelectric plants in the world.

This plant didn’t exist to power homes. Its primary purpose was to serve nearby industries: electrochemical, electrometallurgical, and manufacturing firms that required vast amounts of energy. The ability to harness hydropower made Niagara Falls a magnet for energy-intensive factories.

Founded in 1891, Carborundum relocated to Niagara Falls in 1895 to take advantage of the abundant hydroelectric power. They manufactured silicon carbide abrasives, known as “carborundum,” using electric furnaces that operated at high heat. The company was the second to contract with the Niagara Falls Power Company, underscoring the plant’s role in attracting energy-intensive industries.

The promise of abundant cheap power made Niagara Falls the world capital of electro-chemical and electro-metallurgical industries, which included such companies as the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA), Carborundum (which developed the world’s hardest abrasive as well as graphite), Union Carbide, American Cyanamid, Auto-Lite Battery, and Occidental Petroleum. These were enterprises that depended upon abundant cheap power. At its industrial peak, in 1929, Niagara Falls was the leading manufacturer in the world of products using abrasives, carbon, chlorine, and ferro-alloys.

Niagara National Heritage Area Study, 2005, U.S. Department of the Interior

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Niagara Falls became a hub for industrial activity, primarily due to its abundant hydroelectric power. The establishment of the Niagara Falls Power Company in 1895 marked the beginning of large-scale electricity generation in the area. This readily available power attracted energy-intensive industries, including aluminum production, electrochemical manufacturing, and abrasives. Companies like the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (later Alcoa) and the Carborundum Company set up operations to capitalize on the cheap and plentiful electricity.

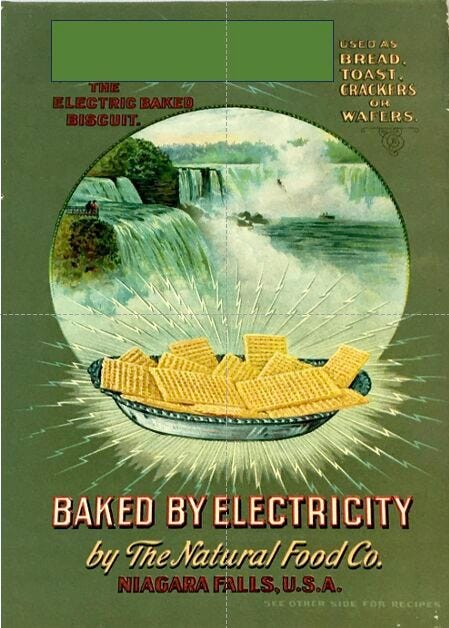

Even food companies jumped on the opportunity for abundant electricity. The founder of the Shredded Wheat Company (maker of both Shredded Wheat and Triscuit), Henry Perky, built a large factory directly at Niagara Falls, choosing the site precisely because of its access to cheap, abundant hydroelectric power. When the Triscuit cracker was first produced in 1903, the factory was powered entirely by electricity—a key marketing point. Early ads bragged that Triscuits were “Baked by Electricity,” which was a novel and futuristic idea at the time.

However, this rapid industrial growth came at a significant environmental cost. The freedom afforded to early industry in Niagara Falls meant that area waterways became dumps for chemicals and other toxic substances. By the 1920s, Niagara Falls was home to a dynamic and thriving chemical sector that produced vast amounts of industrial-grade chemicals via hydroelectric power. This included the production of chlorines, degreasers, explosives, pesticides, plastics, and myriad other chemical agents.

The success at Niagara set a precedent: electricity could fuel industrial expansion, and factories began lobbying for access to centralized electric power. States and cities recognized that electrification attracted investment, jobs, and tax revenue. This created political pressure to expand grids and build new generation capacity—not to homes first, but to industrial parks and cities with manufacturing bases.

The environmental impact was profound. In 1986, Canadian researchers discoveredthat the mist from the falls contained cancer-causing chemicals, leading both the U.S. and Canada to promise cleanup efforts. Moreover, the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls became infamous for being the site of one of the worst environmental disasters involving chemical wastes in U.S. history. The area was used as a dumping ground for nearly 22,000 tons of chemical waste, leading to severe health issues for residents and eventual evacuation of the area.

This historical example underscores the complex legacy of electrification—while it spurred industrial advancement and economic growth, it also led to environmental degradation and public health crises.

The Salesman of the Grid: Samuel Insull and the Corporate Vision of a Public Good

Even as electricity was still being marketed as a lifestyle upgrade—offering clean kitchens, lighted parlors, and “freedom from drudgery”—Samuel Insull was reshaping the electrical industry behind the scenes in ways that would bring electricity to both homes and factories on an unprecedented scale. A former secretary to Thomas Edison, Insull became the president of Chicago Edison (later Commonwealth Edison) and transformed the electric utility into a regional power empire. He championed centralized generation, long-distance transmission, and, most importantly, load diversity: the idea that combining industrial and residential customers would create a steadier, more profitable demand curve.

Industry, after all, consumed massive amounts of electricity during the day, while households peaked in the evenings. By blending these demands, utilities could justify larger power plants that ran closer to capacity around the clock—making electricity cheaper to produce per unit and more profitable to sell.

Insull’s holding companies and financial structures helped finance this expansion, often using consumer payments to support new infrastructure. This helped expand the grid outward—to serve not just wealthy homes and big factories, but small towns and middle-class neighborhoods. Electrification became a virtuous cycle: the more customers (especially industrial ones) you had, the more power you could afford to generate, which brought in more customers. The industrial appetite for power and the domestic aspiration for comfort were two sides of the same system.

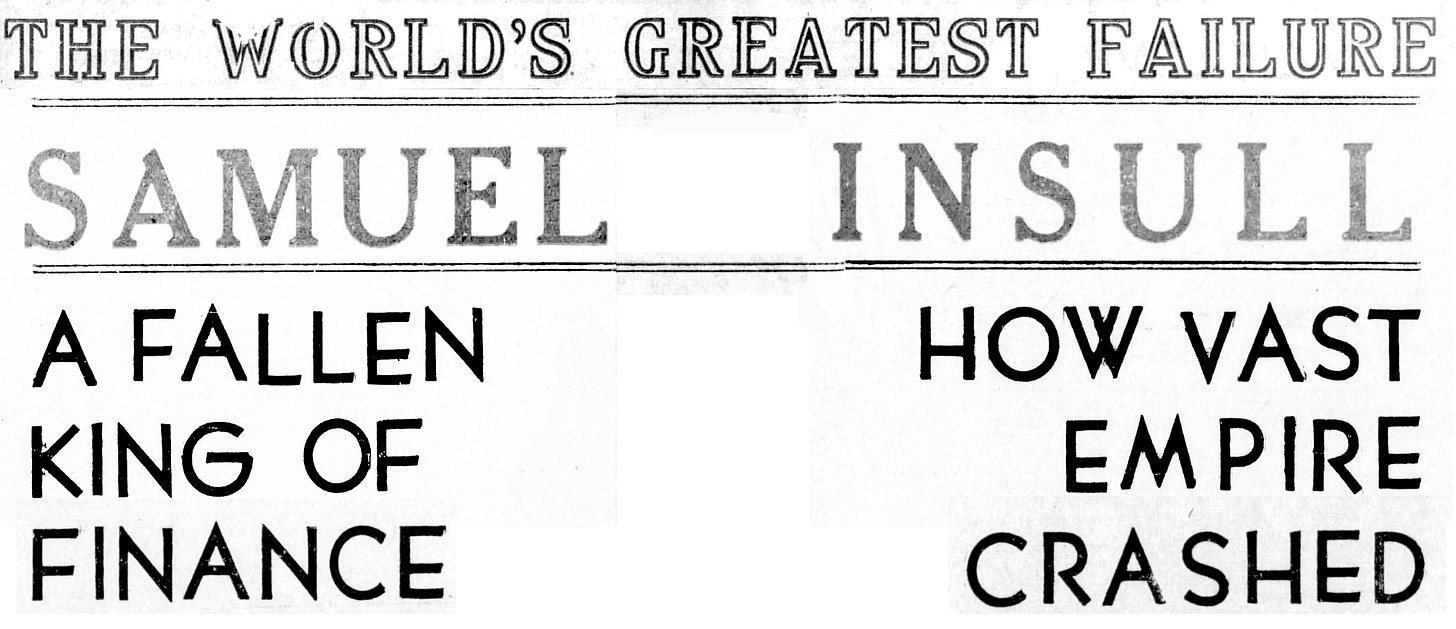

By the early 20th century, Insull had consolidated dozens of smaller electric companies into massive holding corporations, effectively inventing the modern utility monopoly. His genius wasn’t technical but financial: he pioneered the use of long-term bonds and ratepayer-backed financing to build expansive infrastructure, including coal-fired power plants and transmission lines that could serve entire cities and suburbs.

Insull also understood that to secure profits, electricity had to become not a luxury, but a public necessity. He lobbied for—and helped shape—state-level utility commissions that regulated rates but guaranteed companies a return on investment. He promoted a pricing model in which larger customers subsidized smaller residential ones, making electricity seem affordable while expanding the customer base. In speeches and newspaper campaigns, Insull insisted that electricity was a public service best delivered by private enterprise—so long as that enterprise was shielded from competition and supported by the state.

But Insull’s vision had limits. His business model was urban, corporate, and capital-intensive. It thrived in cities where growth and profits were assured—but left rural America behind. Even by the late 1920s, nearly 90% of rural households still had no electricity, and private utilities had little interest in changing that. When Insull’s financial empire collapsed during the Great Depression—leaving thousands of investors penniless—it triggered a wave of backlash and set the stage for Roosevelt’s 1930s public electrification programs.

The failure of Insull’s empire didn’t just expose the risks of private monopolies; it also reframed electricity as too essential to be left entirely in corporate hands. If the promise of electrification was to reach beyond city limits, it would take more than advertising. It would take state power.

Electricity as a Public “Good”

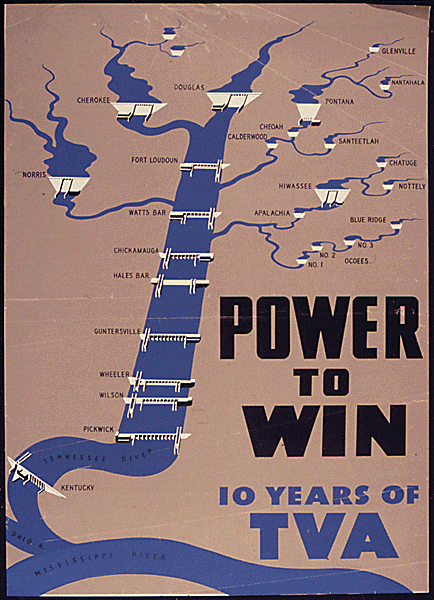

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal ushered in that power—both literally and figuratively. Federal programs like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) tackled electrification as a national mission. The TVA aimed to transform one of the poorest regions in the country through public power and flood control. The REA extended loans to rural cooperatives to build distribution lines where private utilities refused to go. The WPA, though more broadly focused on employment and infrastructure, supported the building of roads, dams, and even electric grids that tied into the new public utilities.

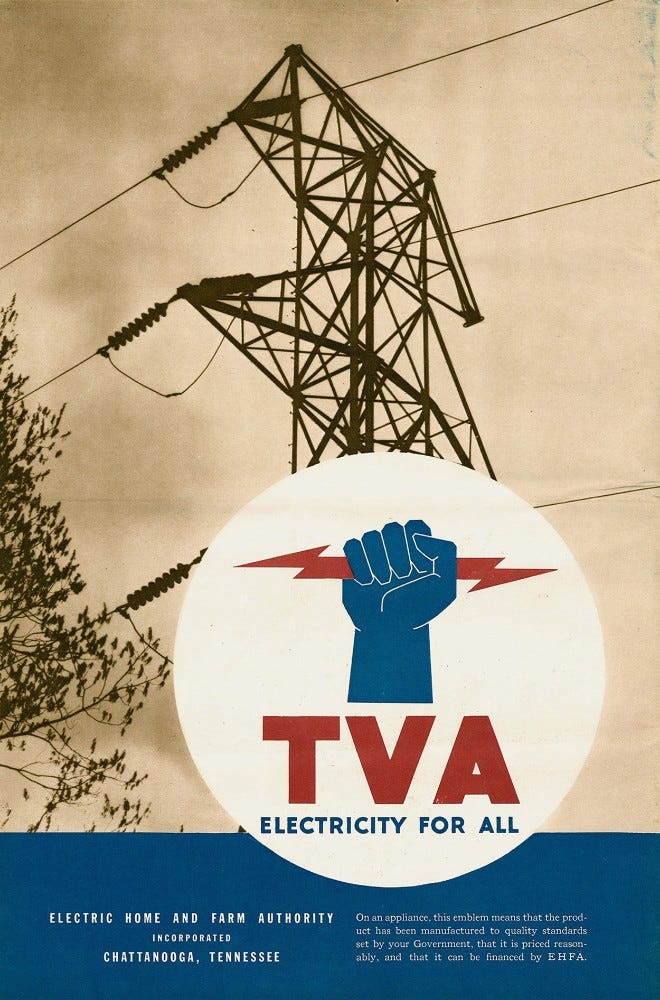

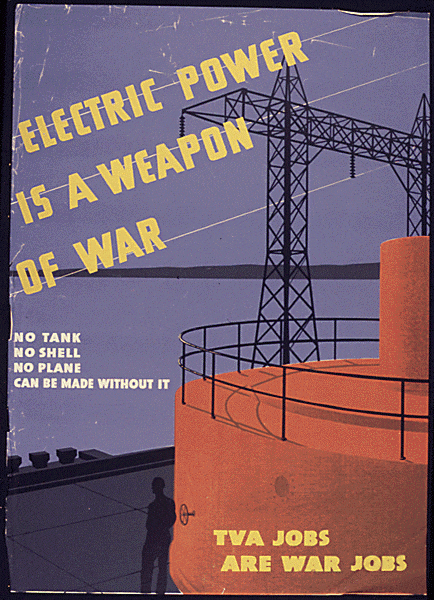

But these were not just engineering projects—they were nation-building efforts, wrapped in the language and imagery of progress. Government-sponsored films, posters, and exhibits cast electrification as a patriotic duty and a moral good. In The TVA at Work (1935), a TVA propaganda film, darkness and floods give way to light as electricity reaches the rural South, promising flood control, education, health, and hope.

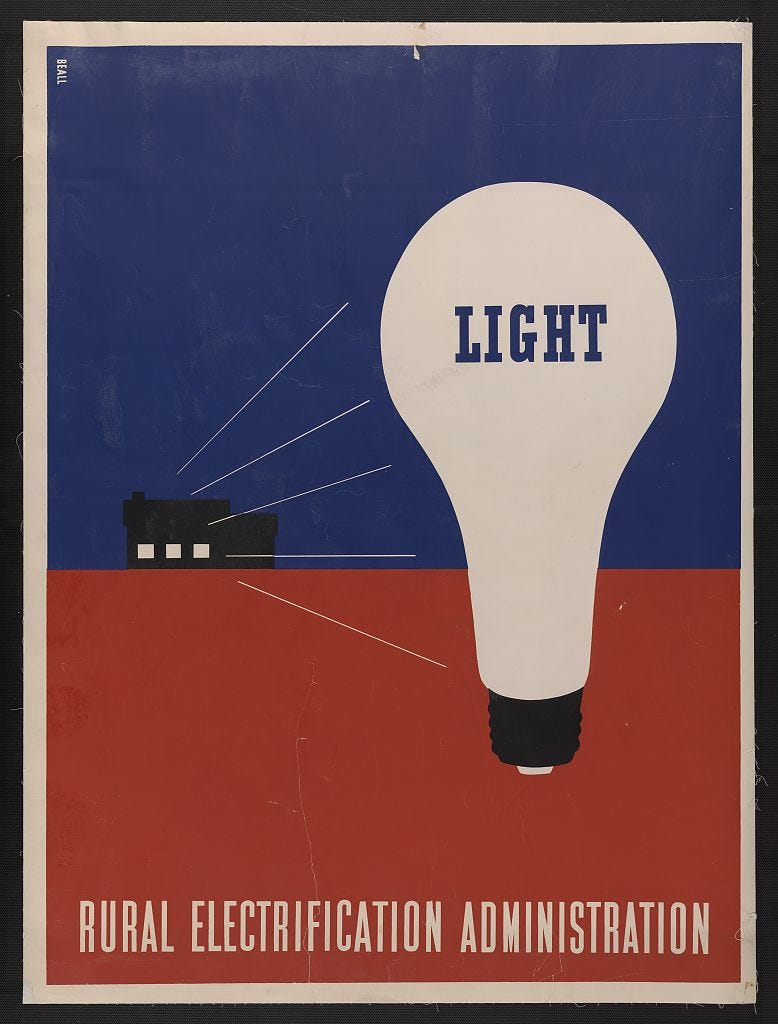

Posters issued by the REA featured glowing farmhouses surrounded by darkness, their light a beacon of the federal government’s benevolence. Electrification was no longer a luxury product to be sold—it was a public right to be delivered. And propaganda helped recast the electric switch as not just a convenience, but a symbol of democratic progress.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the business of providing electricity was largely in private hands, dominated by powerful industrialists who operated in a fragmented and often exploitative landscape. Rates varied wildly, service was inconsistent, and rural areas were left behind entirely. Out of this chaos emerged a slow, contested movement to treat electricity not as a luxury good for profit but as a regulated public utility—something closer to a right.

Roosevelt’s electrification programs—especially the TVA and the REA—aimed to provide public benefits rather than private profit. But in reality, most rural Americans didn’t vote on where dams and coal-fired power plants would go, how the landscape would be transformed, or who would manage the power. The decision-making remained highly centralized, and the voice of the people was filtered through federal agencies, engineers, and bureaucrats. If this was democracy, it was a technocratic form—focused on distributing benefits, not sharing power.

Still, for many rural communities, the arrival of electricity felt like democratic inclusion: a recognition by the federal government that their lives mattered too. New Deal propaganda leaned into this feeling. Posters, pamphlets, and films portrayed electrification as a patriotic triumph—uniting the country, modernizing the nation, and bringing light to all Americans, not just the urban elite.

FDR fiercely criticized utility companies for their opposition to these efforts. In one speech, he called out their “selfish purposes,” accusing them of spreading propaganda and corrupting public education to protect their profits. His administration’s Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 was designed to break up massive utility holding companies, increase transparency, and limit the abusive practices that had flourished under Insull’s system.

By the end of the 1930s, electricity had changed in the eyes of the law and the public. It was no longer a commodity like soap or phonographs. It was essential—a regulated utility, under public scrutiny, increasingly expected to reach all people regardless of profit margins.

How Rural Communities Organized for Electricity

Reaching everyone required more than federal mandates; it required rural people—many of whom had never flipped a light switch—to believe electricity was not just possible, but necessary. New Deal propaganda didn’t just promote electrification; it made it feel like a patriotic obligation. In posters, films, and traveling exhibits, electricity was depicted as a force of national renewal, radiating from power plants and wires like sunlight over a darkened land. Farmers who had once relied on kerosene lanterns saw glowing visions of electric barns, modern kitchens, and clean, running water. The message was clear: this wasn’t charity—it was justice.

The REA offered low-interest loans to communities willing to organize themselves into cooperatives. But before wires could be strung, people had to organize—drawing maps, knocking on doors, pooling resources. That kind of coordination didn’t happen spontaneously. It was sparked, in large part, by persuasive media.

REA films like Power and the Land (1940) dramatized the transformation of farm life through electricity. Traveling REA agents brought these short films and illustrated pamphlets to town halls, church basements, and grange meetings, showing everyday people that their neighbors were already forming co-ops—and thriving. REA’s Rural Electrification News magazine featured testimonials from farm wives, who praised electric irons, cream separators, and the ability to read after sunset. Electrification wasn’t just about comfort; it was about dignity and opportunity.

A TVA poster from the period shows power lines bringing power for farm fields, homes, and factories. The subtext was unmistakable: electricity was the pulse of a modern democracy. You didn’t wait for it. You organized for it.

And people did. Between 1935 and 1940, rural electrification—driven by this blend of policy and persuasion—expanded rapidly. By 1940, more than 1.5 million rural homes had electricity, up from barely 300,000 just five years earlier. The wires came not just because the government built them, but because people demanded them, formed cooperatives, and rewired their lives around a new kind of infrastructure—one they now believed they deserved.

When FDR created the REA in 1935, fewer than 10% of rural homes had electricity. By 1953, just under two decades after the REA’s launch, over 90% of U.S. farms had electric service, much of it delivered through cooperatives that had become symbols of rural self-determination.

The Federal Power Act

In 1935, the same year Roosevelt signed executive orders establishing the Rural Electrification Administration, Congress passed the Federal Power Act—an often-overlooked but foundational shift in how electricity was governed in the United States. At the time, only about 60% of American homes had electricity, and the vast majority of rural households remained off the grid. Industry was rapidly becoming reliant on continuous, 24/7 electric power to run increasingly complex machinery and production lines, making reliable electricity essential not just for homes but for the nation’s economic engine.

The Act expanded the jurisdiction of the Federal Power Commission, granting it authority to regulate interstate transmission and wholesale sales of electricity. This marked a decisive move away from the era of laissez-faire monopolies toward public oversight. Industry players, eager for dependable and affordable power to sustain growth and competition, played a subtle but important role in pushing for federal regulation that would stabilize the market and ensure widespread, reliable access. The Act framed electricity not as a luxury commodity but as a vital service that required accountability and coordination. In tandem with the New Deal electrification programs, it laid the legal groundwork for treating electricity as a public good—setting the stage for how electricity would be mobilized, mythologized, and mass-produced during wartime.

Electricity as Patriotic Duty

By the end of the 1930s, electricity had changed in the eyes of the law and the public. It was no longer a commodity like soap or phonographs. It was essential—a regulated utility, under public scrutiny, increasingly expected to reach all people regardless of profit margins.

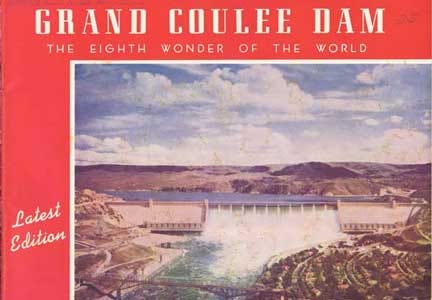

But as the nation edged closer to war, the story of electricity changed again. The gleaming kitchens and “eighth wonder of the world” dams of New Deal posters gave way to a new message: power meant patriotism. Electricity was no longer just a household convenience or symbol of rural uplift—it was fuel for victory.

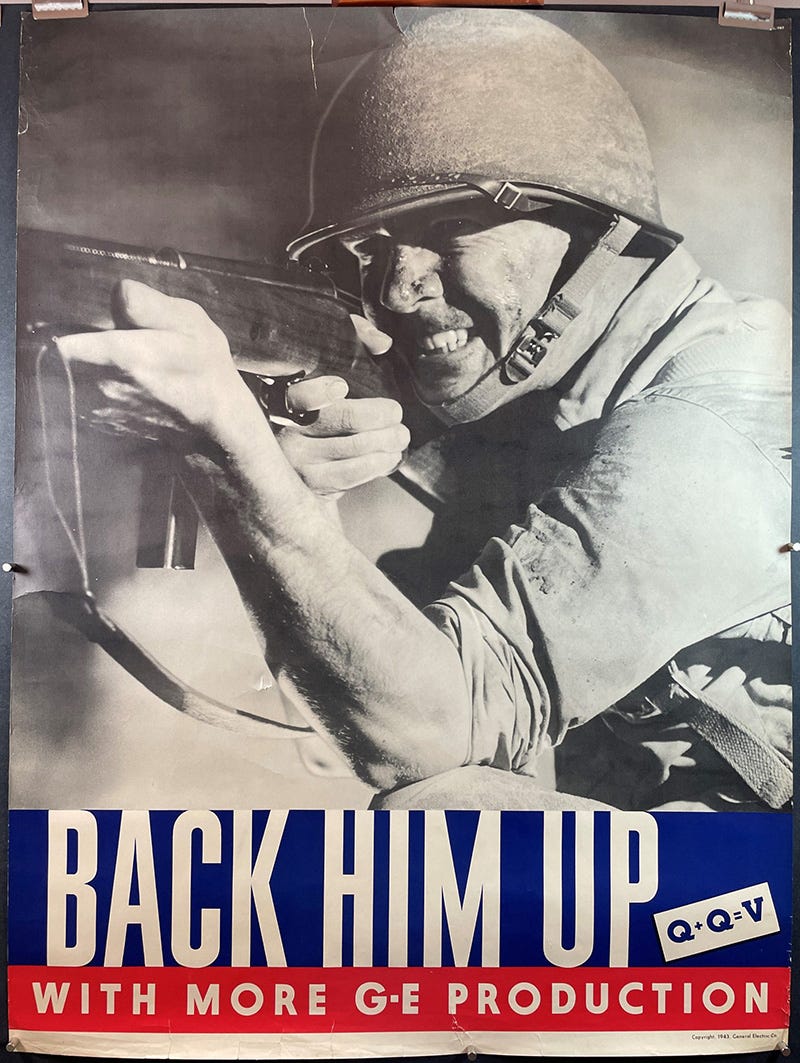

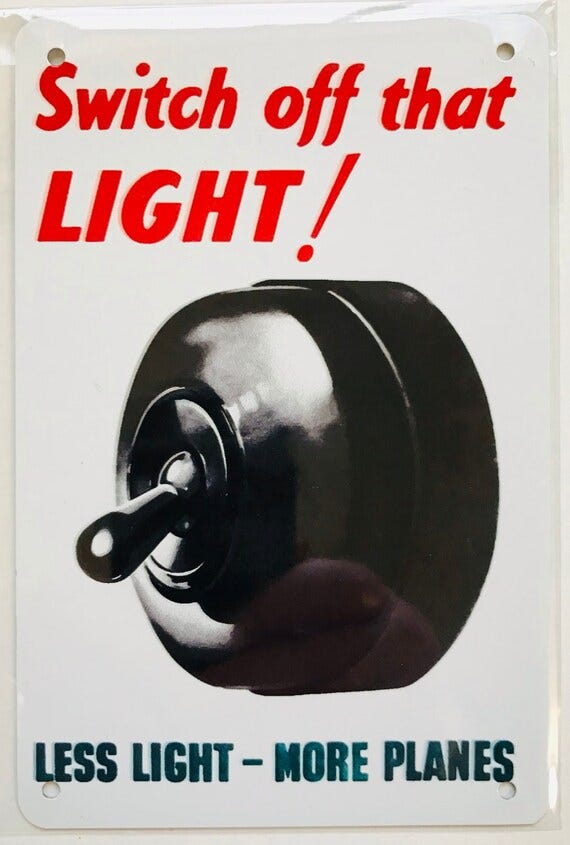

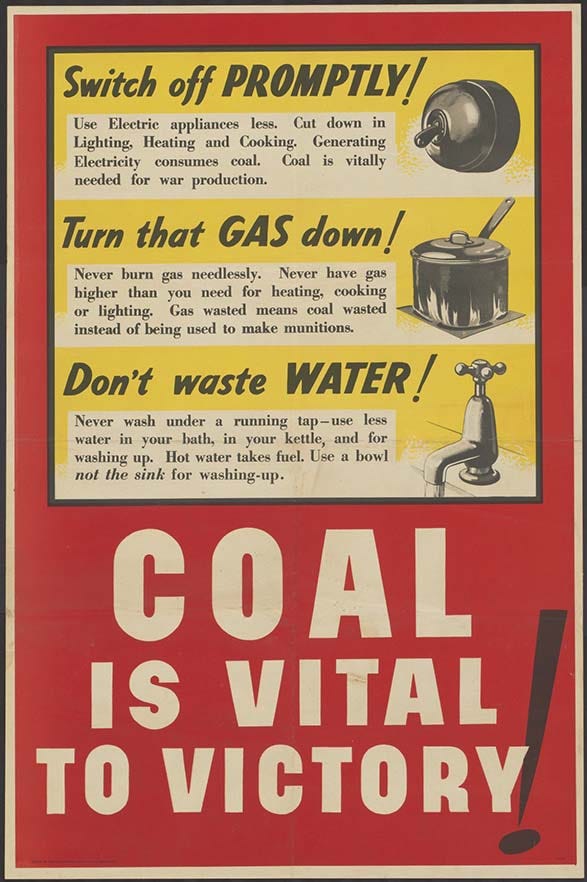

Even before the U.S. formally entered World War II, government and industry launched campaigns urging Americans to think of their energy use as a form of service. Factories were electrified at full tilt to produce planes, tanks, and munitions. Wartime posters and advertisements called on citizens to “Do Your Part”—to conserve power at home so it could be redirected to the front. Lights left on unnecessarily weren’t just wasteful; they were unpatriotic.

One striking 1942 poster from the U.S. Office of War Information featured a light switch with the message: “Switch off that light! Less light—more planes.” Another encouraged energy conservation by asking people to switch lights off promptly because “coal is vital to victory” (at this time 56% total electricity on U.S. grids was generated by coal).

For women, especially, electricity was again positioned as a moral responsibility. Earlier ads had promised electric gadgets to free housewives from drudgery; now, propaganda reminded them that their efficient use of electric appliances was part of the national war strategy. The same infrastructure built by New Deal programs now helped turn the rural power grid into an engine of military supply.

Electricity had become inseparable from national identity and survival. To use it wisely was to serve the country. To waste it was to betray the war effort. This was no longer a story of gadgets and progress—it was a story of sacrifice, duty, and unity under the banner of light.

Nowhere was this message clearer than in the materials produced by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), which managed the massive hydroelectric output of the Columbia River dams in the Pacific Northwest. In the early 1940s, the BPA commissioned a series of posters to dramatize the link between public power and wartime production. One of the most iconic, “Bonneville Fights Time,” shows a welder in a protective mask, sparks flying, framed by dynamic lines of electricity and stylized clock hands. The message: electric power enabled faster, more precise welding—crucial for shipbuilding, aircraft, and munitions production.

The poster’s bold composition connected modernist design with national urgency. Bonneville’s electricity wasn’t just flowing to light bulbs—it was flowing to the war factories of the Pacific coast, to the shipyards of Portland and Seattle, and to the aluminum plants that turned hydroelectric power into lightweight warplanes. These images promoted more than technical efficiency; they sold a vision of democratized power mobilized for total war.

Through such propaganda, the promise of public power was reimagined—not just as a civic good, but as a weapon that could help win World War II.

Electrifying the American Dream

When the war ended, the messaging around electricity shifted again—from sacrifice to surplus. Wartime rationing gave way to a marketing explosion, and the same electrified infrastructure that had powered victory was now poised to power prosperity. With factories retooled for peace-time commerce, and veterans returning with GI Bill benefits and dreams of suburban life, the home became the new front line of American identity—and electric gadgets were its weaponry.

The postwar boom fused electricity with consumption, convenience, and class mobility. Advertisements no longer asked families to conserve power for the troops; they encouraged them to buy electric dishwashers, toasters, vacuum cleaners, televisions. Owning a full suite of appliances became a marker of success, a tangible reward for patriotism and patience. Electricity was no longer just a utility—it was the lifeblood of modern living, sold with the same glamour and intensity once reserved for luxury cars or perfumes.

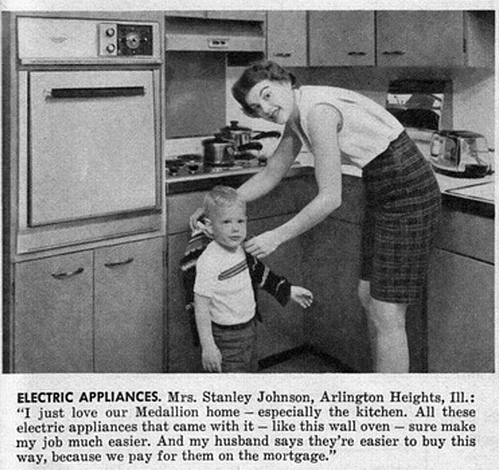

Utilities and manufacturers teamed up to keep the vision alive. The Live Better Electrically campaign, launched in 1956 and endorsed by celebrities like Ronald Reagan, urged Americans to “go all-electric”—not just for lighting and appliances, but for heating, cooking, and even air conditioning. The campaign painted a glowing picture of total electrification, backed by images of smiling housewives, sparkling kitchens, and obedient gadgets. In one ad, a mother proudly paints a heart on her electric range as her children and husband laugh and smile. The future, once uncertain, had been domesticated.

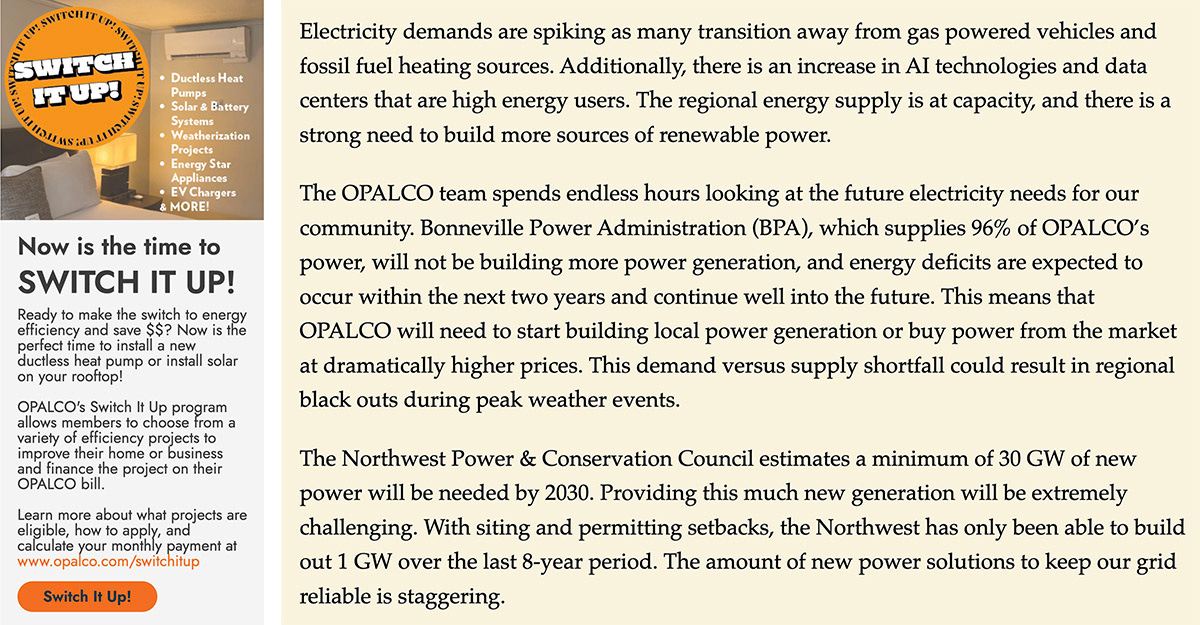

Nowhere was the all-electric ideal more vividly branded than in the Gold Medallion Home, a product of The Live Better Electrically campaign. These homes were awarded a literal gold medallion by utilities if they met a full checklist: electric heat, electric water heater, electric kitchen appliances, and sufficient wiring to support a future of plugged-in living. Promoted through glossy ads and celebrity endorsements, the Medallion Home symbolized upward mobility, domestic modernity, and patriotic participation in a high-energy future. It was a propaganda campaign that blurred the line between consumer aspiration and infrastructure planning. Today’s “electrify everything” efforts—encouraging heat pumps, EVs, induction stoves, and smart panels—echo this strategy. Once again, homes are being refashioned as sites of technological virtue and national progress, marketed through a familiar mix of lifestyle promise and utility coordination. The medallion has changed shape, but the message remains: the future lives here.

This was propaganda of abundance. And behind it was an unspoken truth: electrification had won. What had once been sold as fantasy—glimpsed in world’s fair palaces or GE films—was now embedded in daily life. The flick of a switch no longer symbolized hope. It had become habit.

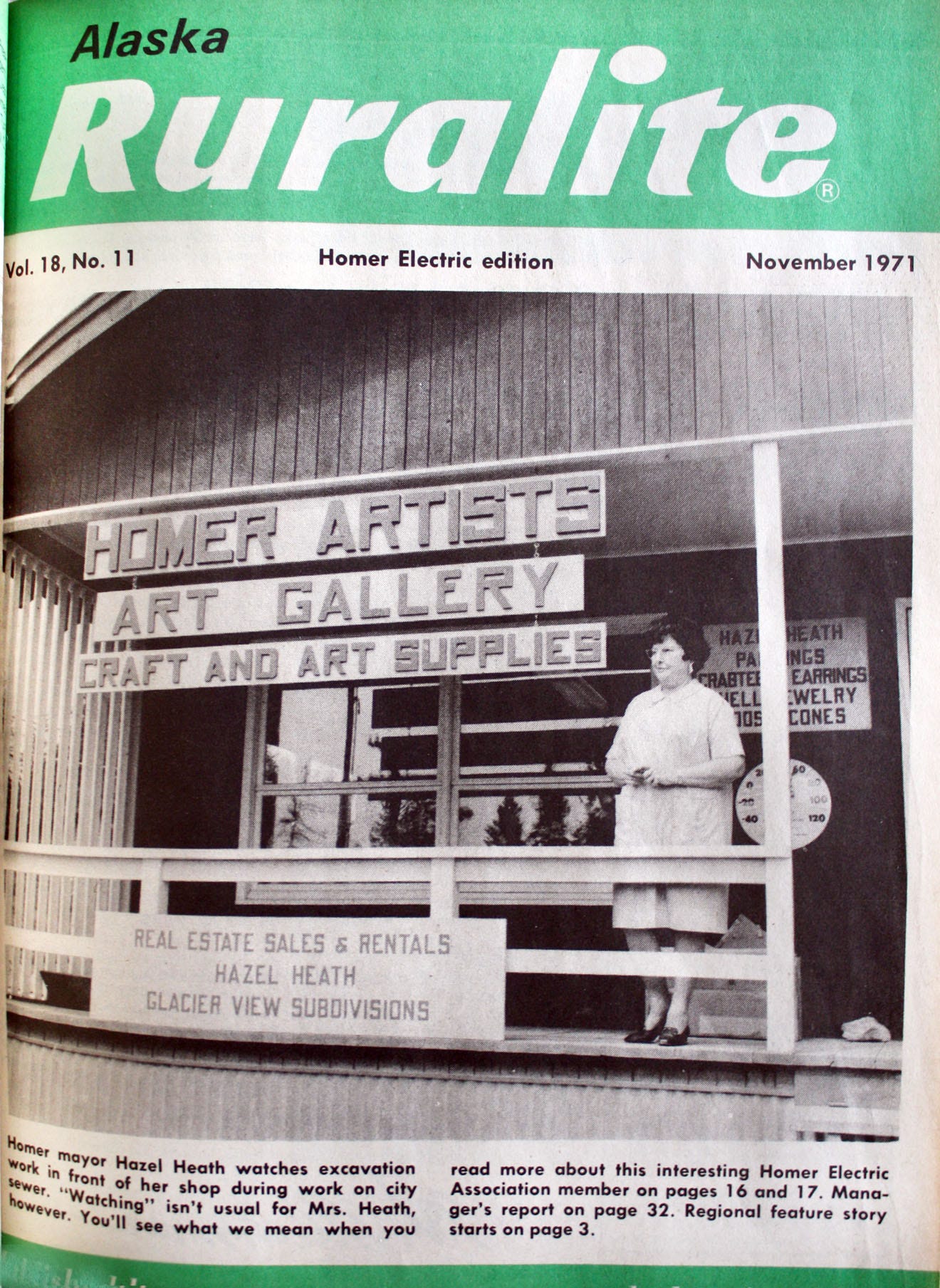

Ruralite

Ruralite magazine serves as the flagship publication of Pioneer Utility Resources, a not-for-profit communications cooperative to serve the rural electric cooperatives (or co-ops) across the western United States. It was—and remains—a shared publication platform for dozens of small, locally owned utility co-ops that formed in the wake of the REA.

Each electric co-op—often based in small towns or rural counties—can customize part of the magazine with local news, board updates, outage reports, and community features. But the bulk of the magazine is centrally produced, offering ready-made content: stories about electric living, energy efficiency, co-op values, new technologies, and the benefits of belonging to a cooperative utility system.

In this sense, Ruralite functions as a kind of regional PR organ: a hybrid of lifestyle magazine, customer newsletter, and soft-sell propaganda tool. It is funded by and distributed through electric co-ops themselves, landing monthly in the homes of hundreds of thousands of rural residents.

Though it debuted in 1954—well after the apex of New Deal electrification programs—Ruralite can be seen as a direct descendant of that era’s propaganda infrastructure, repackaged for peacetime and consumer prosperity. The TVA had its posters, the REA had its pamphlets, and Ruralite had glossy photo spreads of farm wives with gleaming electric ranges.

Where New Deal propaganda had rallied Americans to support rural electrification as a national project of fairness and modernity, Ruralite shifted the tone toward comfort, aspiration, and consumer loyalty. It picked up the baton of electrification as cultural transformation, reinforcing the idea that electric living wasn’t just a right—it was the new rural ideal.

Ruralite framed rural electrification not as catching up to the cities, but as leading the way in a new era—one where rural values, ingenuity, and resourcefulness would power the country forward. In this way, co-ops and their members became symbols of progress, not just beneficiaries of it.

This was propaganda not by posters or patriotic slogans, but through community storytelling. Ruralite grounded its messaging in local personalities, recipes, and relatable anecdotes, while embedding calls to adopt more appliances, update homes, and trust in the local co-op as a benevolent, forward-looking institution.

Today, Ruralite remains rooted in local storytelling, but its tone aligns more with contemporary consumer lifestyle media. Sustainability, renewables, and energy efficiency now appear alongside nostalgic rural features and recipes. Yet despite the modern packaging, the core narrative remains consistent: electricity is integral to the good life. That through-line—from a beacon of modernization to a pillar of local identity—demonstrates how the publication has adapted without abandoning its propagandistic roots.

In the current energy landscape, Ruralite plays a quiet but significant role in advancing the “electrify everything” agenda—the 21st-century push to decarbonize buildings, transportation, and infrastructure by transitioning away from fossil fuels to electric systems.

While Ruralite doesn’t use overtly political language, it steadily normalizes new electric technologies like heat pumps, EVs, induction stoves, and solar arrays. Features on homeowners who upgraded to electric water heaters, profiles of co-ops launching EV charging stations, or DIY guides for energy audits all reinforce the idea that the electric future is practical, responsible, and here. The message is aspirational but grounded in small-town pragmatism: this isn’t Silicon Valley hype—it’s your neighbor electrifying their barn or replacing a propane furnace or reminiscing about life without electricity.

Ruralite continues the legacy of New Deal-era propaganda by promoting ever-greater electricity use—now through electric vehicles and heat pumps instead of fridges and space heaters—reinforcing the idea that progress always means more power, more consumption, and more infrastructure. Its storytelling still serves a strategic function—ensuring electricity remains not just accepted, but desired, in every American home.

Postwar Peak and Decline of Electrification Propaganda

By the 1960s, most American homes—urban and rural—had been electrified. The major battle to electrify the country was won. As a result, the overt electrification-as-progress propaganda that had dominated the New Deal era and postwar boom faded. Electricity became mundane: a background utility, no longer something that needed to be sold as revolutionary.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the focus of public discourse shifted toward energy crises and conservation. Rather than expanding electrification, the government and utilities started encouraging Americans to use less, not more—a notable, if temporary, reversal. The 1973 oil shock, Three Mile Island (1979), and rising distrust in institutions tempered the earlier utopian energy messaging.

However, electrification propaganda never vanished entirely. It just narrowed. Publications like Ruralite and utility co-ops continued localized campaigns, pushing upgrades (like electric water heaters or electric stoves) in rural areas and maintaining a cultural narrative of electric life as modern and efficient.

The Renewables-Era Revival of Electrification Propaganda

In the late 1990s and especially the 2000s, a new wave of electrification propaganda began to emerge, but this time under the banner of climate action. Instead of promoting electricity as luxury or convenience, the new message was: electrify everything to save the planet.

This “green” electrification push encourages:

- Electric vehicles (EVs) to replace gasoline cars

- Heat pumps to replace fossil fuel heating systems

- Induction stoves over gas ranges

- Grid modernization and massive renewable build-outs (wind, solar, batteries)

The messaging echoes earlier propaganda in tone—glossy, optimistic, often uncritical—but reframes the moral purpose: not modernization for its own sake, but decarbonization. The tools remain similar: media campaigns, federal incentives, public-private partnerships, and co-op publications like Ruralite, which has evolved to reflect this new narrative.

Modern utility outreach events like co-op utility Orcas Power and Light Cooperative’s (OPALCO) EV Jamboree—where electric vehicles are showcased, test drives offered, and electrification is framed as exciting and inevitable—echo the strategies of the REA’s mid-century traveling circuses. Just as the REA brought portable demonstrations of electric appliances and farm equipment to rural fairs to sell the promise of a brighter, cleaner, more efficient life, today’s utilities stage events to generate enthusiasm for electric vehicles, heat pumps, and smart appliances. In both cases, the goal is not just education but persuasion—selling a future tied to deeper dependence on the electric grid.

One of the most striking revivals is the push for nuclear power, long dormant after public backlash in the 1980s. Once considered politically radioactive and dangerous, nuclear is now rebranded as a clean energy savior. The Biden administration has supported small modular reactor (SMR) development and extended funding for existing nuclear plants. More recently, President Donald Trump announced plans to reinvest in nuclear infrastructure, positioning it as a strategic national asset and imperative for national security and industry. The messaging is clear: nuclear is back, and it’s being sold not just as a technology, but as a patriotic imperative.

The Green Delusion and the Digital Demand: Modern Propaganda for an Electrified Future

In the 21st century, electrification propaganda has been reborn—not as a tool to bring light to rural homes or sell refrigerators, but as a moral and technological mandate. This time, it’s cloaked in the language of sustainability, innovation, and decarbonization. Utilities, tech giants, and government agencies now present an electrified future as inevitable and ethical. But beneath the rhetoric lies a powerful continuity with the past: electricity must still be sold to the public, and propaganda remains the vehicle of persuasion.

The contemporary campaign is driven by a potent mix of actors. Investor-owned utilities plaster their websites with wind turbines and solar panels, promoting the idea that they are leading the charge toward a cleaner future. Federal and state governments offer rebates and incentives for EVs, solar panels, heat pumps, and induction stoves, framing these changes not only as personal upgrades, but as civic duties. Corporate giants like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon amplify the message, touting their commitment to “100% renewable” operations—while quietly brokering deals for bespoke gas and nuclear plants to keep their operations online, and selling their digital services to fossil fuels companies.

Deceptive practices are proliferating alongside the expansion of renewable energy infrastructure. Companies developing utility-scale solar projects often mislead communities about the scale, impact, and permanence of proposed developments—if they engage with them at all. Local residents frequently report being excluded from the planning process, receiving vague or misleading information, or being outright lied to about how the projects will alter their environment. As Dunlap et al. document in their paper ‘A Dead Sea of Solar Panels:” Solar Enclosure, Extractivism and the Progressive Degradation of the California Desert, such tactics are not anomalies but part of a systemic pattern:

[W]e would flat out ask them [the company] questions and their answers were not honest … [it] led me to believe they really didn’t care about us. They had charts of where lines were going to be, and later, we found out that it wasn’t necessarily the truthful proposal. And you’re thinking: ‘why do you have to deceive us?’

— Desert Center resident, quoted in ‘A Dead Sea of Solar Panels:’ solar enclosure, extractivism and the progressive degradation of the California desert, by Dunlap et. al.

These projects, framed publicly as green progress, often mask an extractive logic—one that mirrors the practices of fossil fuel development, only cloaked in the language of sustainability.

At the heart of this new energy push lies a paradox: the renewable future requires more electricity than ever before. Electrifying transportation, heating, and industry demands a massive expansion of grid infrastructure—new transmission lines, more generation, and more raw materials. But increasingly, the driver of this expansion is data.

Artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and cryptocurrency mining are extraordinarily power-hungry. Modern AI models require vast data centers, each consuming megawatts of electricity—often 24/7. In his May 2025 Executive Order promoting nuclear energy, President Donald Trump made this explicit: “Advanced nuclear reactors will power data centers, AI infrastructure, and critical defense operations.” Here, electricity isn’t just framed as a public good—it’s a strategic asset. The demand for clean, constant energy is now justified not by light bulbs or quality of life, but by national security and economic dominance in the digital age.

This shift has profound implications. The public is once again being asked to accept massive infrastructure projects—new power generation plants and transmission corridors, subsidies for private companies, and increased energy bills—as the price of progress. Utilities and politicians assure us that this growth is green, even as the material and ecological costs of building out renewables and data infrastructure are hidden from view. The new propaganda is sleeker, data-driven, and more morally charged—but at its core, it performs the same function as its 20th-century predecessors: to justify a massive increase in power use.

A particularly insidious thread in this new wave of propaganda is the claim that artificial intelligence will “solve” climate change. This narrative, repeated by CEOs, media outlets, and government officials, frames AI as a kind of techno-savior: capable of optimizing energy use, designing better renewables, and fixing broken supply chains. But while these applications are technically possible, they are marginal compared to the staggering energy footprint of building and running large-scale AI systems. Training a single frontier model can consume as much power as a small town.Once operational, the server farms that host these models run 24/7, devouring electricity and water—often in drought-prone areas—and prompting utilities to fire up old coal and gas plants to meet projected demand.

Under the guise of “solving” the climate crisis, the AI boom is accelerating it. And just like earlier propaganda campaigns, the messaging is carefully crafted: press releases about “green AI” and “green-by-AI” along with glossy reports touting efficiency gains distract from the physical realities of extraction, combustion, and carbon emissions. The promise of virtual solutions is being used to justify real-world expansion of energy-intensive infrastructure. If previous generations were sold the dream of electrified domestic bliss, today’s consumers are being sold a dream of digital salvation—packaged in clean fonts and cloud metaphors, but grounded in the same old logic of growth at all costs.

The Material Reality of “Electrify Everything”

While the language of “smart grids,” “clean energy,” and “electrify everything” suggests a sleek, seamless transition to a more sustainable future, the material realities tell a very different story. Every CPU chip, electric vehicle, solar panel, wind turbine, and smart meter is built from a global chain of extractive processes—mined lithium, cobalt, copper, rare earth elements, steel, silicon, and more—often sourced under environmentally destructive and socially exploitative conditions. Expanding the grid to support these technologies requires not just energy but immense physical infrastructure: transmission lines slicing through forests and deserts, substations and data centers devouring land and power, and constant maintenance of an aging, overstretched network.

Yet this reality is largely absent from public-facing narratives. Instead, we’re fed slogans like “energy humanism” and “clean electrification”—terms that obscure the industrial scale and catastrophic impacts of what’s being proposed. Like the early electrification propaganda that portrayed hydropower as endlessly abundant and benevolent (salmon and rivers be damned), today’s messaging continues to erase the costs of extraction, land use, and energy consumption, promoting technological salvation without acknowledging the planetary toll.

The scale of extraction required to electrify everything is staggering. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), reaching global climate goals by 2040 could require a massive increase in demand for minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. For lithium alone, the World Bank estimates production must at least quadruple by 2040 to meet EV and battery storage needs. Copper—essential for wiring and grid infrastructure—faces a predicted shortfall of 6 million metric tons per year by 2031, even as global demand continues to surge with data centers, EVs, and electrification programs.

Mining companies have seized the moment to rebrand themselves as climate heroes. Lithium Americas, which plans to operate the massive Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada, is described as “a cornerstone for the clean energy transition” and touts itself as a boon for local employment, even while the company destroys thousands of acres of critical habitat. The company promises jobs, school funding, and tax revenue—classic propaganda borrowed from 20th-century industrial playbooks. But local resistance, including from communities like the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, underscores the deeper truth: these projects degrade ecosystems, threaten sacred sites, and deplete water resources in arid regions.

Another mining giant, Rio Tinto, has aggressively marketed its “green” copper and lithium projects in Serbia, Australia, and the U.S. as “supporting the green energy revolution,” while downplaying community opposition, pollution risks, and the company’s long history of environmental destruction. Their PR materials highlight “sustainable mining,” “low-carbon futures,” and “partnering with communities,” despite persistent local protests and growing global awareness of mining’s high environmental costs.

What’s missing from these narratives is any serious reckoning with the energy required to mine, transport, refine, and manufacture these materials, along with the energy needed to power the growing web of electrified infrastructure. As the demand for data centers, EV fleets, AI training clusters, and smart grids accelerates, we are rapidly expanding industrialization in the name of sustainability, substituting fossil extractivism with mineral extractivism rather than questioning the ever-increasing energy and material throughput of modern society.

Across the U.S., utilities are aggressively promoting electric vehicles, heat pumps, and “smart” appliances as part of their electrification campaigns—often framed as climate solutions. Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) in California, for example, offers rebates on EVs and encourages members to electrify their homes and transportation. Yet at the very same time, utilities like PG&E also warn that the electric grid is under strain and must expand dramatically to meet rising demand. This contradiction is rarely acknowledged. Instead, utilities position grid expansion as inevitable and green, framing it as “modernization” or “resilience.” What’s omitted is that electrifying everything doesn’t reduce energy use—it shifts and increases it, requiring vast new infrastructure, more centralized control, and continued extractivism.

The public is told that using more electricity will save the planet, while being asked to accept more pollution and destroyed environments along with new transmission lines, substations, and higher rates to pay for it all.

From Luxury to Necessity: Total Dependence on a Fragile Grid

The stability of the electricity grid requires electricity supply to constantly meet electricity demand, which in turn, requires numerous entities that operate different components of the grid to coordinate with each other.

Over the last century, electricity has shifted from a shimmering novelty to an unspoken necessity—so deeply embedded in daily life that its absence feels like a crisis. This transformation did not happen organically; it was engineered through decades of propaganda, from World’s Fairs and government-backed campaigns to glossy co-op magazines and modern “electrify everything” initiatives. What began as a promise of convenience became a system of total dependence.

Today, every layer of modern life—communication, healthcare, finance, water delivery, food preservation, transportation, and farming—relies on a constant, invisible stream of electrons. Yet the grid that supplies them is increasingly strained and precarious. As utilities push electric vehicles, heat pumps, and AI-fueled growth, and states (like Washington State) offer tax incentives to electricity-hungry industries, they simultaneously warn that the grid must expand rapidly to avoid collapse. The public is told this expansion is progress. But the more electrified our lives become, the more vulnerable we are to its failures.

This was laid bare in March 2024, when a massive blackout in Spain left over two million people without power and seven dead. Train systems halted. ATMs stopped working. Hospitals ran on limited backup power. Food spoiled, water systems faltered, and thousands were stranded in elevators and subways. The cause? A chain of technical failures made worse by infrastructure stretched thin by new demands and the rapid expansion of renewables. Spanish officials called it a “wake-up call.” But for many, it was a terrifying glimpse into just how brittle the electric scaffolding of modern life has become.

Contrast that with life just 130 years ago, when the vast majority of Americans lived without electricity. Homes were lit by kerosene and heated by wood. Water was drawn from wells. Food was preserved with salt or root cellars. Communities were far more self-reliant, and daily life, while harder in some ways, was not exposed to the singular point of failure that defines today’s electrified society.

Before widespread electrification, communities were more tightly knit by necessity. Without the conveniences of refrigeration, electric heating, or instant communication, people relied on one another. Neighbors shared food, labor, stories, and tools. Social life centered around common spaces—markets, churches, schools, porches. Mutual aid was not a political slogan but a basic survival strategy. Electricity helped alleviate certain physical burdens, but it also enabled a more atomized existence: private appliances replace shared labor, television and now Netflix replace neighborhood gatherings, and online connection supplants physical community.

The electrification of everything, sold as liberation, has created a new form of total dependence. We have not simply added electricity to our lives—we have rewired life itself to require it. And as the grid stretches to accommodate AI servers, data centers, electric fleets, and “smart” everything, the question we must ask is no longer how much we can electrify—but how much failure we can endure.

It’s hard to imagine life today without electricity—yet just 130 years ago, almost no one had it, and communities thrived in very different ways. Our deepening dependence on the grid is not simply our choice; technologies like AI and massive data centers are being imposed upon us, often without real consent or public debate.

As we barrel toward ecological collapse—pervasive pollution, climate chaos, biodiversity loss, and the sixth mass extinction—our blind faith in endless electrification risks bringing us back to a state not unlike that distant past, but under far more desperate circumstances. Now more than ever, we must question the costs we ignore and face the difficult truth: the future we’re building may demand everything we take for granted, and then some.

References

America & the World: The Legacy of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair

Gains from factory electrification: Evidence from North Carolina, 1905–1926

Powering American Farms: The Overlooked Origins of Rural Electrification

Niagara National Heritage Area Study, 2005, U.S. Department of the Interior

From Insull to Enron: Corporate (Re)Regulation After the Rise and Fall of Two Energy Icons

Samuel Insull and the Movement for State Utility Regulatory Commissions

Live Better Electrically: The Gold Medallion Electric Home Campaign

The Mouth of the Kenai: Almanac: Electrifying news you can use

A pivot to renewable energy by the Philippine government has led to a wave of hyrdoprojects projects across the Cordillera region. Image by Andrés Alegría / Mongabay.

A pivot to renewable energy by the Philippine government has led to a wave of hyrdoprojects projects across the Cordillera region. Image by Andrés Alegría / Mongabay. Hydropower projects have met with differening receptions in Cordillera villages such as Balbalan, Mabaca and Buaya. Image by Andrés Alegría / Mongabay.

Hydropower projects have met with differening receptions in Cordillera villages such as Balbalan, Mabaca and Buaya. Image by Andrés Alegría / Mongabay. The Cal-oan River, also known as Mabaca River, where Australian-owned JBD Water Power Inc. (JWPI) has two planned hydropower projects. Image by Michael Beltran.

The Cal-oan River, also known as Mabaca River, where Australian-owned JBD Water Power Inc. (JWPI) has two planned hydropower projects. Image by Michael Beltran. Farmer Gohn Dangoy, of the Naneng tribe, says proposed dams have already caused deep divisions in his community. Image by Michael Beltran.

Farmer Gohn Dangoy, of the Naneng tribe, says proposed dams have already caused deep divisions in his community. Image by Michael Beltran. A man in Kalinga Province wears a shirt reading “No to Dam.” Image by Michael Beltran.

A man in Kalinga Province wears a shirt reading “No to Dam.” Image by Michael Beltran. Residents of villages close to the Chico River meet to discuss plans to dam the river for hydroelectricity. Image by Michael Beltran.

Residents of villages close to the Chico River meet to discuss plans to dam the river for hydroelectricity. Image by Michael Beltran.