by DGR News Service | Sep 1, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

This short introduction to the concept of “mutual aid” was originally published by Keith O’Connell in Oh Shit! What Now? Mutual aid is placed in opposition to social Darwinism which promotes competition, and the power of the ruling class under capitalism. While Deep Green Resistance is not an anarchist organization, we draw heavily on the mutual aid tradition.

By Keith O’Connell / Oh Shit! What Now?

Capitalism can inspire people to do many amazing things, as long as there is a profit to be made. But in the absence of a profit motive, there are many important tasks that it will not and cannot ever accomplish, from eradicating global poverty and preventable diseases, to removing toxic plastics from the oceans. In order to carry out these monumental tasks, we require a change in the ethos that connects us to one another, and to the world that sustains us. A shift away from capitalism … towards mutual aid.

Anarchists work toward two general goals. First they want to dismantle oppressive, hierarchical institutions. Second, they want to replace those institutions with organic, horizontal, and cooperative versions based on autonomy, solidarity, voluntary association, mutual aid and direct action. Through mutual aid, anarchism takes shape as a practice in care, exchanging resources and solidarity, information, support, even comfort, care, and understanding. People give what they can and get what they need. When a group comes together to push for a change; when social outsiders come together to share or explore ideas and new ways of living, these are all forms of mutual aid.

Of course, mutual aid is obviously not a new idea, nor is it exclusive to anarchists. However, to understand this specific embrace of mutual aid, we need to go back over 100 years, to the writings of the famous Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, who just so happened to also be an accomplished zoologist and evolutionary biologist.

Back in Kropotkin’s day, the field of evolutionary biology was heavily dominated by the ideas of Social Darwinists such as Thomas H. Huxley. By ruthlessly applying Charles Darwin’s famous dictum “survival of the fittest” to human societies, Huxley and his peers had concluded that existing social hierarchies were the result of natural selection, or competition between free sovereign individuals, and were thus an important and inevitable factor in human evolution.

Not too surprisingly, these ideas were particularly popular among rich and politically powerful white men, as it offered them a pseudo-scientific justification for their privileged positions in

society, in addition to providing a racist rationalization of the European colonization of Asia, Africa and the Americas. Kropotkin attacked this conventional wisdom, when in 1902 he published a book called “Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution,” in which he proved that there was something beyond blind, individual competition at work in evolution.

It is a concept that is familiar to many anarchists, but often not fully understood. Mutual aid doesn’t mean automatic solidarity with whoever asks for it, nor does it mean that anarchists have an obligation to enter into relationships with other oppositional forces. It is not a bartering system; it rejects the “tit-for-tat” psychology of modern capitalism while challenging the notion of communist distribution. It means to be able to give freely and take freely: from each according to her/his ability, to each according to her/his need. Mutual aid is only possible between and among equals (which means among friends and trusted long-term allies). Solidarity, on the other hand (since it is offered to and asked for by ad hoc allies), needs to include the reality of reciprocation.

Do you ever spend time thinking about where the food you eat, or the clothes you wear come from? What about the labor and materials that went into building your house, or your car? Left to fend for ourselves without the comforts of civilization, few among us would survive a week, let alone be able to produce a fraction of the myriad commodities we consume every day.

From the great pyramids commissioned by the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, to today’s globe-spanning production and supply chains, the primary function of the ruling class has always been to organize human activity. And everywhere that they have done so, they have relied on coercion. Under capitalism, this activity is organized through either direct violence, or the internalized threat of starvation created by a system based on private ownership of wealth and property.

In an era of a dwindling welfare state with social safety net provisions crumbling, the importance of mutual aid and support networks could not be more important. The examples of such models are many. Clients at a syringe exchange share a place to stay. Such mutual aid networks helped keep many alive and off the streets, where they inevitably would have been swept up by police and sent to the de facto poor person’s housing provider: city jail.

In San Francisco, when people lose lovers to the AIDS crisis, neighborhood members formed a group called the Mary Widowers. This mutual aid group helps widowers cope with their losses, find new spaces for care, work, love, art, and fun. Mutual aid helps people survive.

Syringe exchange activist Donald Grove helped organize an underground syringe exchange program called Moving Equipment. “It was about creating a basis of mutual self support from which we could do this other stuff. And much of that support was born of an ethos of care among social outsiders. User organizing, people want it to be about political campaigns and stuff like that but what I see is that users are already organized in a hostile environment about just providing basic survival needs. To say that is not enough is to demand that everything and all political models act and look like the dominant political model. Sometimes self care is enough.”

Imagine a world in which human activity was not organized on the basis of ceaseless competition over artificially scarce resources, but the pursuit of the satisfaction of human needs … and you will understand a vision of the world that anarchists seek to create.

What is Mutual Aid? from sub.Media on Vimeo.

by DGR News Service | Aug 29, 2020 | Human Supremacy

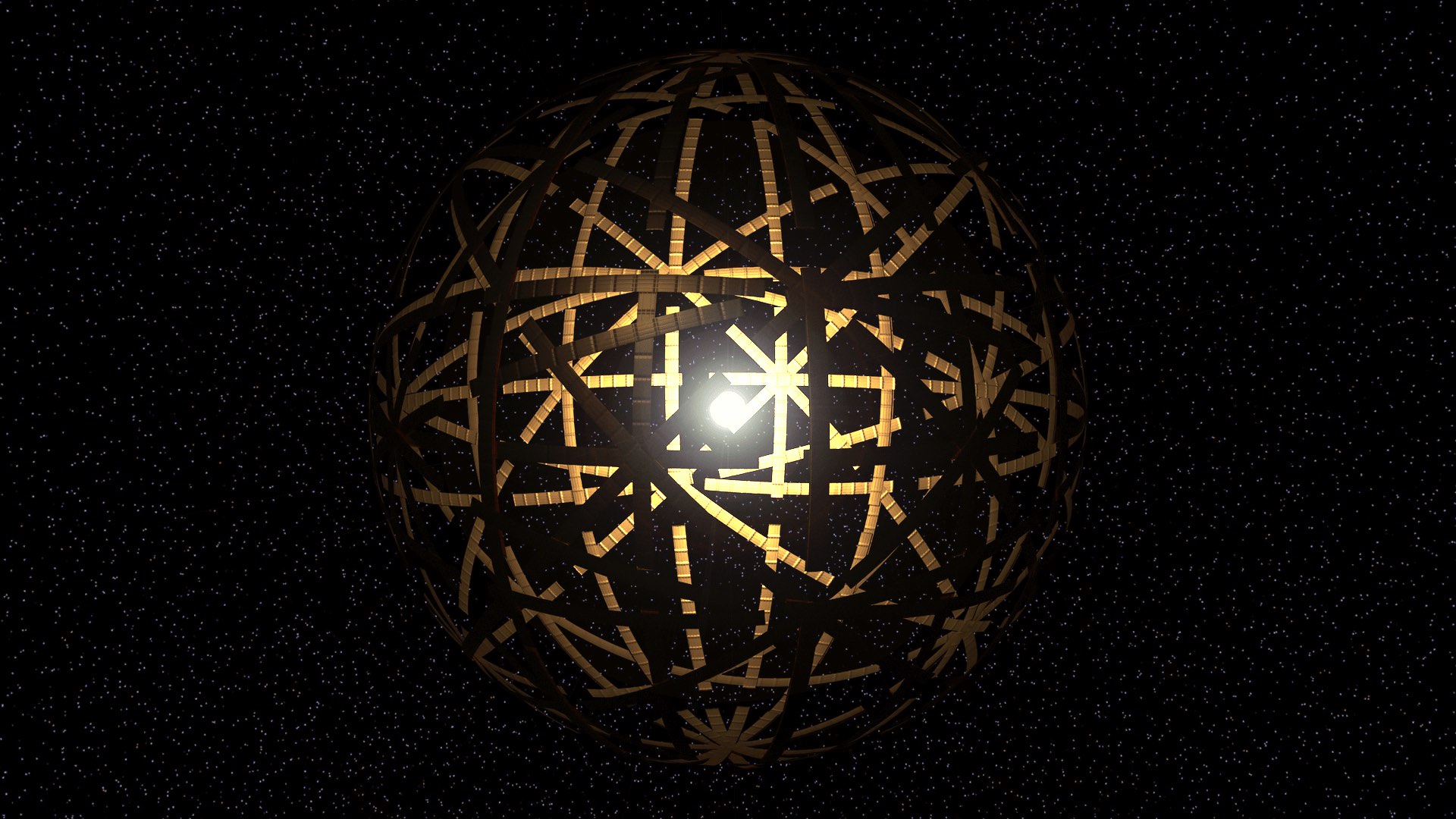

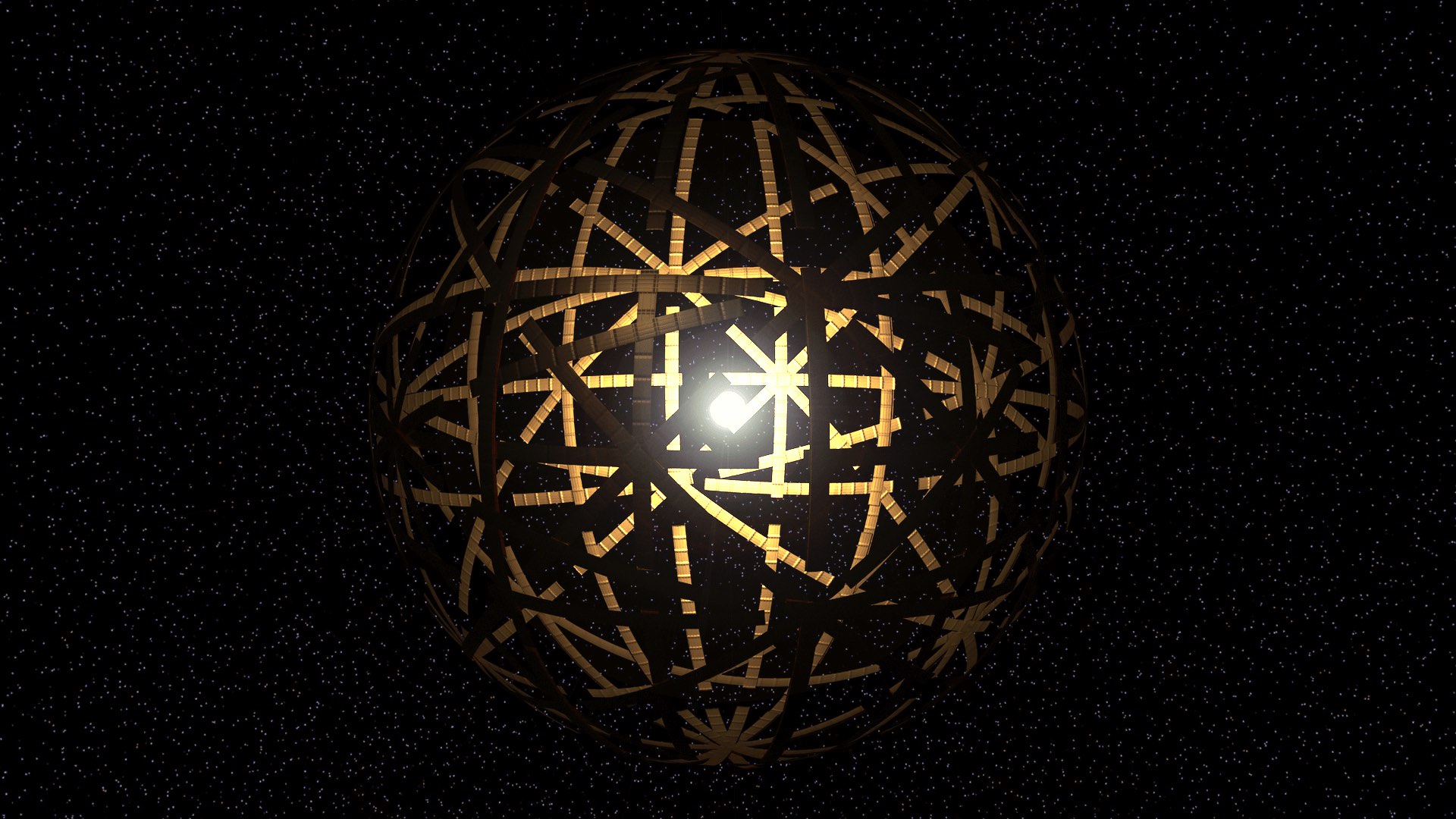

This is the second in a series of articles reflecting on a recent study which predicts collapse of industrial society within a few decades. In the first essay, Max Wilbert discusses how in the long-run, collapse will benefit both humans and nature alike. This second essay in the series explores a “solution” proposed by the original authors of the study—a “Dyson sphere”—and why it will not save us from a collapse.

By Salonika / DGR Asia-Pacific

A Dyson sphere is a theoretical energy harvesting, a metal sphere that completely encompasses a star, and harnesses 100% of the solar energy. The solar panels that form its membranes would capture and transmit energy to Earth’s surface through microwave or laser. A concept that originated from a science fiction, it has been considered to be the ultimate “solution” to an industrial civilization’s ever increasing demand for energy.

There are a lot of problems with this theoretical solution. The authors of the study themselves are skeptical about the possibility of building a Dyson sphere by the time of their predicted collapse. We are going to deal with this issue in later parts of this series. In this piece, I will explore the improbable scenario that a Dyson sphere is built to fulfill the fantastical visions of the technocrats and whether that could prevent the ensuing collapse.

Is energy crisis the only crisis we are facing?

The obsession of the current environmental movement with renewable energy could easily confuse anyone regarding the scale of the ecological crisis that we are facing. We now witness a mass delusion that the energy crisis is, in fact, the only crisis that civilization is facing. In reality, the energy crisis represents just a facet of the ecological crisis.

Let’s consider global deforestation, which was used in the model for the study. The authors assert that once the Dyson sphere is used to “solve” our energy problems, the global deforestation would halt, ensuring the longevity of human civilization on Earth. This assertion is based on an unstated assumption that forests are being cleared primarily for fuel. As a matter of fact, fuel is only one driver of deforestation. Forests are also cleared for agriculture, cattle ranching, human settlements, buildings, mining, and roads. Unlimited energy does not “solve” or remove these pressures.

The same is true for all other forms of ecocide. Ninety percent of large fish in the oceans are gone, not to exploit their bodies for fuel, but due to overconsumption of fish as food. Bees colonies are collapsing, not for fuel, but, scientists estimate, due to pesticides, malnutrition, electromagnetic radiation, and genetically modified crops. Two hundred species are disappearing every day. That’s one every six minutes. That’s a result of habitat destruction, climate change, overexploitation, and toxification, not the need for energy.

A Dyson sphere (if it is ever created) could solve only the so-called energy crisis. All the other crises – habitat destruction, toxic environmental pollution, land clearing for agriculture, mining, overexploitation of species, and so on – would still continue. Indeed, the very existence of a Dyson sphere could increase the exploitation of the environment.

How is a Dyson sphere created?

First, a Dyson sphere would bemore massive than Earth itself. It would demands an astronomical (pun intended!) amount of raw materials, particularly metals. Procurement of these raw materials would require resource extraction on an unprecedented scale. Resource extraction (like mining) is one of the primary causes of environmental degradation, including global deforestation. Proponents advocate mitigating this harm by mining asteroids rather than planet Earth, but developing and building the fleet of spacecraft necessary for such an endeavor would necessarily begin on Earth, and would be incredibly harmful. In a single launch, a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket emits 1352 tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. (That’s nearly 300 times what an average car emits every year.)

Once created, a Dyson sphere would also need to be maintained. On average, a solar panel lasts about 25-30 years, after which the amount of energy produced will decline by a significant amount. It means that in every thirty years, the entire Dyson sphere would have to be rebuilt again. Let’s assume that the solar panels of the Dyson sphere would be more durable than the ones we use now. Even so, they will be subjected to different risks, like damage from asteroids or comets. A Dyson sphere would create a perpetual demand for (and, inevitably, overconsumption of) nonrenewable materials.

Additionally, the Dyson sphere could not function on its own. A new set of infrastructures would need to be built in order to utilize the energy harnessed. These include laser beam or microwave transmitters for wireless energy transmission from space to earth, additional photovoltaic cells in Earth to receive the transmitted solar energy, transmission wires (and poles) to supply the energy to industrial areas, and batteries to store the energy for when clouds block microwave transmission.

These building blocks come with additional costs. Wireless transmission of such vast quantities of energy can potentially cause eye and skin damage and other harm to human health, change the weather, and are potential culprits behind bees colony collapse. And what about birds? Traditional transmission lines are a prime cause of deforestation. Photo-voltaic cells usually end up in landfills or are sent to a developing country with lax environmental laws. Creating, maintaining, and disposing of solar panels pollutes the environment at every step.

An Authoritarian Technic

Lewis Mumford distinguishes between authoritarian technics and democratic technics based on whether a piece of technology requires a large-scale hierarchical structure, and whether it reinforces this structure. The Dyson sphere can be considered an authoritarian technic based on both of these criteria. The Dyson sphere requires a massive hierarchical infrastructure to exist in the first place: only specific group of individuals – those who have access and control over these infrastructures – can control its creation. Once created, it will be used to perpetuate the very hierarchical structure that created the conditions for its existence.

A Dyson sphere could exist only in an explicitly human supremacist, and implicitly colonial and patriarchal, culture. It will require resource extraction (primarily mining), on a scale much larger than what we have seen before. Extraction is inherently an ecocidal practice based on forced labor. It has been responsible for the destruction of numerous biospheres, and displacement of both humans and nonhuman communities.

The beneficiaries of this so-called technological “innovation” would be those who are already on the upper rungs of the hierarchical structure. Those on the bottom, on the other hand, would face the consequences. The same is true for other forms of technological innovations that we use every day. Consider a cell phone, for example. For the “haves” of the industrialized society, cell phones are little short of a basic necessity of life, the cost of which are covered by the “have-nots” through perpetual conflicts over resources, forced labor in modern day sweatshops, or even their lives.

The Root of the Problem: Overconsumption

Most importantly, the Dyson sphere does not address the core cause of the civilization’s impending collapse: overconsumption. Despite the claims that technology contributes to efficiency of resource consumption, technology seems to have very little (or even adverse) effect on the global energy consumption. With the exception of 2009 (the year of the global economic recession), consumption has only increased each year since 1990. When the demand for a product is constantly rising, no matter how efficient the production process gets, it will lead to greater consumption of resources.

On the contrary, the authors present a Dyson sphere as a solution to their predicted population collapse. They assume that, the perpetual energy source would lead to a lowered consumption of natural resources, allowing a sustained human population of 10 billion. Even if the culture’s energy demands are met by the perpetual source, in face of a growing (industrialized) human population, we can only presume, the need for more food, more land, more “progress,” and – inevitably – more deforestation.

Furthermore, an implicit (yet obvious) motive for creation of a Dyson sphere is to facilitate our increasing levels of consumption. It will promote an energy intensive way of life. The more energy intensive a way of life is, the more it is based on (over)consumption. In fact, the very existence of a Dyson sphere would demand an exploitation of resources.

A Dyson sphere would not halt deforestation; neither would it stop the acidification of oceans. We’re facing an emergency: an imminent collapse. Many nonhumans have already faced its brutal reality (think about the last member of the species that died while you were reading this article). Now is not the time to indulge in fantasies of a non-existent technology that will salvage the civilization: it is the time to stop whatever is causing the collapse (hint: it’s overconsumption).

Salonika is a member of Deep Green Resistance Asia-Pacific. She believes that the needs of the natural world should trump the wants of the extractive culture.

Featured image: rendering of Dyson swarm by Kevin M. Gill, cc-by-2.0.

by DGR News Service | Aug 27, 2020 | Toxification

The production of plastics must halt. It is the only way to stop the influx of toxic substances into streams, rivers, lakes, oceans, and into our own bodies. This piece, which is made up of excerpts from a longer article, discusses new research into microplastics found in human organs.

by Krissy Waite / Common Dreams

“The best way to tackle the problem is to massively reduce the amount of plastic that’s being made and used.”

… Arizona State University scientists on Monday presented their research on finding micro- and nanoplastics in human organs to the American Chemical Society…

Microplastics are plastics that are less than five millimeters in diameter and nanoplastics are less than 0.001 millimeters in diameter. Both are broken down bits of larger plastic pieces that were dumped into the environment. According to PlasticsEurope.org, 359 million tons of plastic was produced globally in 2019.

Previous research has shown that people could be eating a credit card’s worth of plastic a day; a study published in 2019 suggests humans eat, drink, and breathe almost 74,000 microplastic particles a year. Microplastics have been found in places ranging from the tallest mountains in the world to the depths of the Mariana Trench.

The Arizona State University scientists developed and tested a new method to identify dozens of plastics in human tissue that could eventually be used to collect global data on microplastic pollution and its impact on people. To test the technique, the scientists used 47 tissue samples from lung, liver, spleen, and kidney samples collected from a tissue bank. Researchers then added particles to the samples and found they could detect microplastics in every sample.

These specific tissues were used because these organs are the most likely to be exposed to, filter, or collect plastics in the human body. Because the samples were taken from a tissue bank, scientists also were able to analyze the donors’ lifestyles including environmental and occupational exposures.

“It would be naive to believe there is plastic everywhere but just not in us,”

Rolf Halden, a scientist on the team, told The Guardian. “We are now providing a research platform that will allow us and others to look for what is invisible—these particles too small for the naked eye to see. The risk [to health] really resides in the small particles … This shared resource will help build a plastic exposure database so that we can compare exposures in organs and groups of people over time and geographic space.”

The researchers found bisphenol A (BPA) in all 47 samples and were also able to detect polyethylene terephthalate (PET)—a chemical used in plastic drink bottles and shopping bags. They also found and analyzed polycarbonate (PC) and polyethylene (PE). These particles can end up in human bodies through the air or by consuming wildlife like seafood that has eaten plastic; or by consuming other foods with trace amounts of plastic from packaging. The team also developed a computer program that converts the collected data on plastic particle count into units of mass and area.

“In a few short decades, we’ve gone from seeing plastic as a wonderful benefit to considering it a threat,”

Charles Rolsky, a member of the team, said in a press release. “There’s evidence that plastic is making its way into our bodies, but very few studies have looked for it there. And at this point, we don’t know whether this plastic is just a nuisance or whether it represents a human health hazard.”

This article was first published on 17th August 2020.

by DGR News Service | Aug 26, 2020 | Mining & Drilling

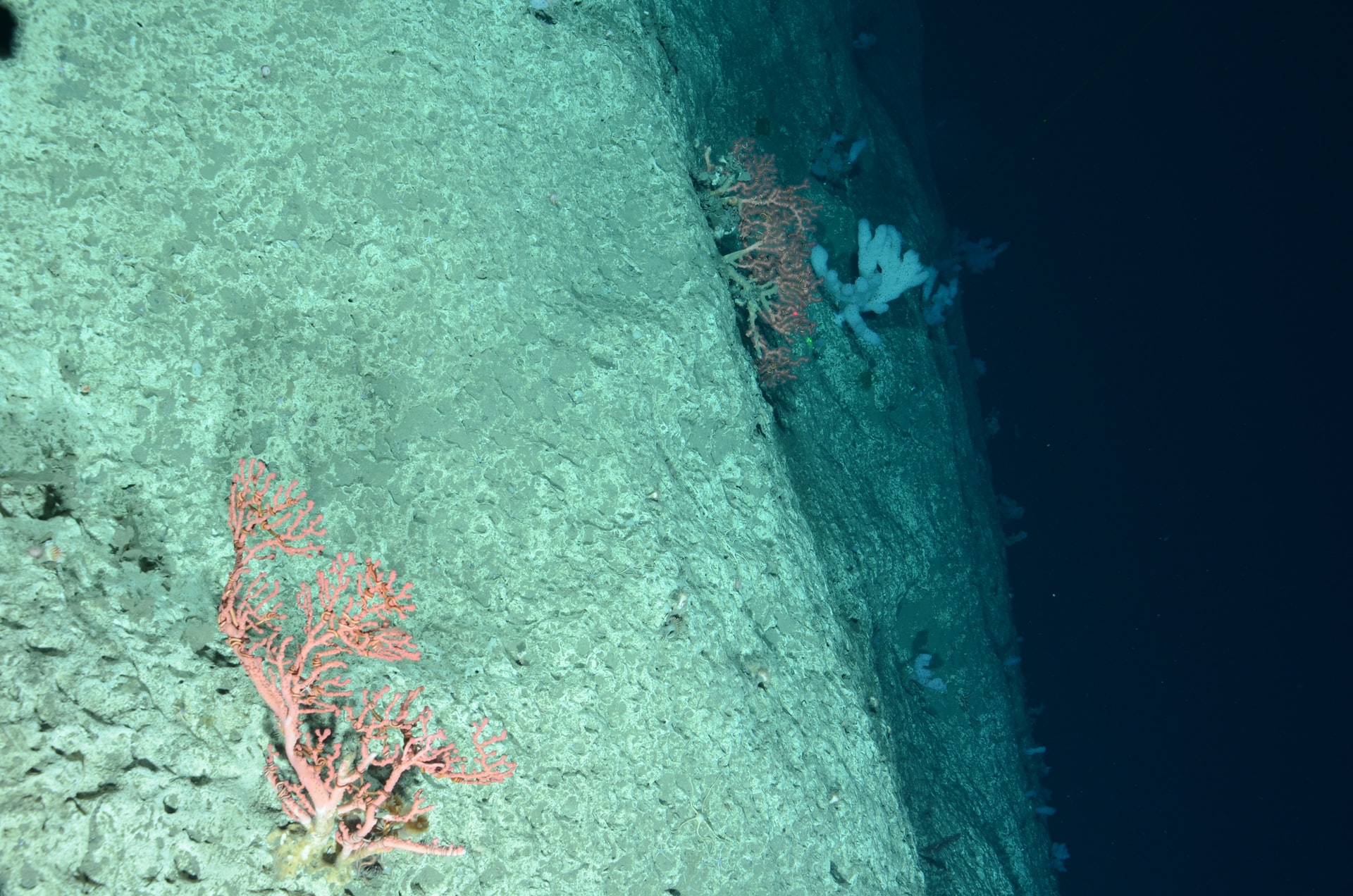

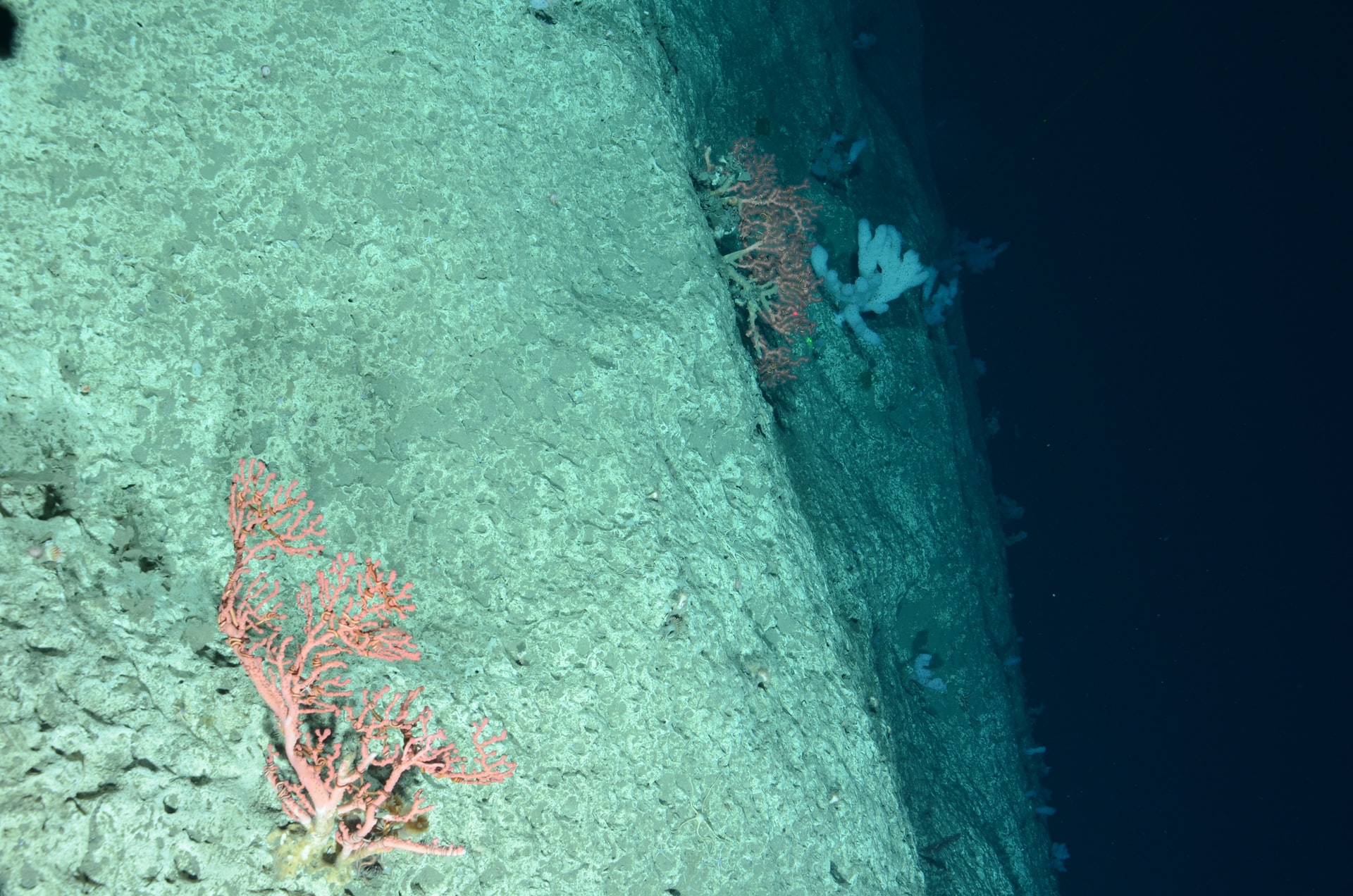

In this article Julia Barnes describes the process of seabed mining and calls for organized resistance to this new ecocidal extraction industry. This article was originally published in Counterpunch

They want to mine the deep sea.

We shouldn’t be surprised. This culture has stolen 90% of the large fish, created 450 de-oxygenated areas, and murdered 50% of the coral reefs. It has wiped out 40% of the plankton. It has warmed and acidified the water to a level not seen since the Permian mass extinction. And indeed, there is another mass extinction underway. Given the ongoing assault on the ocean by this culture, there is serious question as to whether the upper ocean will be inhabitable by the end of this century.

For some people, a best-case scenario for the future is that some bacteria will survive around volcanic vents at the bottom of the ocean.

Deep sea mining is about to make that an unlikely possibility. It’s being touted as history’s largest mining operation. They have plans to extract metals from deposits concentrated around hydrothermal vents and nodules – potato sized rocks – which are scattered across the sea floor. Sediment will be vacuumed up from the deep sea, processed onboard mining vessels, then the remaining slurry will be dumped back into the ocean. Estimates of the amount of slurry that will be processed by a single mining vessel range from 2 to 6 million cubic feet per day. I’ve seen water go from clear to opaque when an inexperienced diver gives a few kicks to the sea floor.

Now imagine 6 million cubic feet of sediment being dumped into the ocean. To put that in perspective, that’s about 22,000 dump trucks full of sediment – and that’s just one mining vessel operating for one day. Imagine what happens when there are hundreds of them. Thousands of them.

Plumes at the mining site are expected to smother and bury organisms on the sea floor. Light pollution from the mining equipment would disrupt species that depend on bio-luminescence. Sediment plumes released at the surface or in the water column would increase turbidity and reduce light, disrupting the photosynthesis of plankton.

A few environmental groups are calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining.

Meanwhile, exploratory mining is already underway. An obscure organization known as the International Seabed Authority has been given the responsibility of drafting an underwater mining code, selecting locations for extraction, and issuing licenses to mining companies. Some companies claim that the damage from deep sea mining could be mitigated with proper regulations. For example, instead of dumping slurry at the surface, they would pump it back down and release it somewhere deeper.

Obviously, regulations will not stop the direct harm to the area being mined. But even if the most stringent regulations were put in place, there still exists the near-certainty of human error, pipe breakage, sediment spills, and outright disregard for the rules.

As we’ve seen with fisheries, regulations are essentially meaningless when there is no enforcement. 40% of the total catch comes from illegal fishing. Quotas are routinely ignored and vastly exceeded. On land, we know that corporations will gladly pay a fine when it is cheaper to do so than it is to follow the rules. But all this misses the point which is that some activities are so immoral, they should not be permitted under any circumstances.

Permits and regulations only serve to legalize and legitimize the act of deep sea mining, when a moratorium is the only acceptable response.

Canadian legislation effectively prohibits deep sea mining in Canada’s territorial waters. Ironically, Canadian corporations are leading the effort to mine the oceans elsewhere. A spokesperson from the Vancouver-based company Deep Green Metals attempted to defend deep sea mining from an environmental perspective,

“Mining on land now takes place in some of the most biodiverse places on the planet. The ocean floor, on the other hand, is a food-poor environment with no plant life and an order of magnitude less biomass living in a larger area. We can’t avoid disturbing wildlife, to be clear, but we will be putting fewer organisms at risk than land-based operations mining the same metals.” (as cited in Mining Watch).

This argument centers on a false choice.

It presumes that mining must occur, which is absurd. Then, it paints a picture that the only area affected will be the area that is mined. In reality, the toxic slurry from deep sea mining will poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles, with heavy metals like mercury and lead expected to bio-accumulate in everyone from plankton, to tuna, to sharks, to cetaceans.

A study from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that “A very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.”

The idea that fewer organisms are at risk from deep sea mining is an egregious lie.

Scientists have known since 1977 that photosynthesis is not the basis of every natural community. There are entire food webs that begin with organic chemicals floating from hydrothermal vents. These communities include giant clams, octopuses, crabs, and 10-foot tube worms, to name a few. Conducting mining in these habitats is bad enough, but the effects go far beyond the mined area.

Deep sea mining literally threatens every level of the ocean from surface to seabed. In doing so, it puts all life on the planet at risk. From smothering the deep sea, to toxifying the food web, to disrupting plankton, the tiny organisms who produce two thirds of the earth’s oxygen, it’s just one environmental disaster after another.

The most common justification for deep sea mining is that it will be necessary to create a bright green future.

A report by the World Bank found that production of minerals such as graphite, lithium, and cobalt would need to increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the growing demand for so-called renewable energy. There is an article from the BBC titled “Electric Car future May Depend on Deep Sea Mining”. What if we switched the variables, and instead said “the future of the ocean depends on stopping car culture” or “the future of the ocean depends on opposing so-called renewable energy”. If we take into account all of the industries that are eviscerating the ocean, it must also be said that “the future of the ocean depends on stopping industrial civilization”.

Evidently this culture does not care whether the ocean has a future. It’s more interested in justifying continued exploitation under the banner of green consumerism. I do not detail the horrors of deep sea mining to make a moral appeal to those who are destroying the ocean. They will not stop voluntarily. Instead, I am appealing to you, the reader, to do whatever is necessary to make it so this industry cannot destroy the ocean.

Julia Barnes is a filmmaker, director of Sea of Life and of the forthcoming film Bright Green Lies.

Featured image: deep-sea coral, Paragorgiaarborea, on the edge of Hendrickson Canyon roughly 1,775 meters or nearly 6000 feet underwater in the Toms Canyon complex in the western Atlantic. NOAA photo.

by DGR News Service | Aug 20, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

This is the first in a series of articles reflecting on a recent study which predicts collapse of industrial society within a few decades. By destroying the ecological foundation on which all life depends, civilization makes collapse inevitable. Max Wilbert describes the destruction caused by the industrial civilization, and what we can do for a just transition to a more sustainable way of life.

by Max Wilbert

A new study published in Scientific Reports finds that there is a 90% chance of civilization collapsing irreversibly within the next 20 to 40 years.

The report, published on May 6th by Dr. Gerardo Aquino, a research associate at the Alan Turing Institute in London, and Professor Mauro Bologna of the Depratment of Electronic Engineering at the University of Tarapacá in Chile, uses statistical and logistical modeling to look at destruction of the planet, and specifically focuses on deforestation and population growth.

By plugging in statistics and trends in resource consumption and running thousands of model-runs with different assumptions, Aquio and Bologna predict the most likely course of future human society.

The researchers conclude that civilization has a “very low probability, less than 10% in the optimistic estimate, to survive without facing a catastrophic collapse.”

This should not be a surprise. The form of social organization we call civilization (a way of life based on the growth of cities) began around 10,000 years ago, and since then this form of society has reduced the number of trees around the world by at least 46 percent—and those who do remain are, on average, much smaller and younger. At current rates of deforestation, nearly every tree on the planet will be gone within the next 100-200 years.

On top of this, civilization (and it’s modern form, industrial civilization) is causing a global mass extinction event, changing the composition of the atmosphere and instigating global climate change, polluting the highest mountains and deepest ocean trenches with industrial chemicals and plastics, desertifying and eroding vast portions of the planet’s soils via agriculture, and fragmenting and shattering what habitat does remain intact via networks of roads and urbanization.

Most people perceive collapse as a terrible thing, and indeed a global collapse will result in a great deal of suffering, disease, and death. But the reality is, a vast amount of suffering is happening now, caused by the continued functioning of industrial civilization. A full forty percent of all human deaths are caused by air, water, and soil pollution according to Cornell research. The CoViD-19 pandemic is a direct result of civilization and the destruction of forests.

On top of this, collapse at this point may be inevitable. As the book Deep Green Resistance explains, “We are in overshoot as a species. A significant portion of the people now alive may have to die before we are back under carrying capacity, and that disparity is growing. Every day carrying capacity is driven down by hundreds of thousands of humans, and every day the human population increases by more than 200,000. The people added to the overshoot each day are needless, pointless deaths. Delaying collapse, they argue, is itself a form of mass murder.”

If you are concerned about this, as I am, as we all should be, you should be working to relocalize food production and smooth the transition away from industrial agriculture. Collapse has both positive aspects (declines in pollution, reduction in logging, end of international shipping, reduction in energy consumption, etc.) and negative aspects (collapse of social structures, medical systems, increased demands on local forests, etc.). These need to be managed and prepared for.

In the long-term, collapse will benefit both humans and nature by stopping industrial civilization and its pollution, global warming, desertification, and so on. Another physicist, Tim Garrett from the University of Utah, has conducted research into global warming and concluded that “only complete economic collapse will prevent runaway global climate change.”

There are over 400 oceanic dead zones created by fertilizer and nutrient runoff from industrial farms. Only one has recovered: the dead zone in the Black Sea, which healed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the crash of industrial farming in the area. The area is now home to healthy wildlife and fish populations which support a stronger local economy.

Ultimately, our health and success as human beings is inseparable from the health of the planet. To destroy the Earth for temporary enrichment a slow form of suicide. But deeper than that, it is matricide, patricide, fratricide. It is the murder of one’s own family. We will only thrive when the natural world, our kin, are thriving as well. Human beings are not doomed to destroy the planet. We can live in other ways, and indeed, that is our only hope.

Featured image by the author.

Our next piece will discuss how a Dyson sphere (one of the proposed “solutions” in the original article) will not save us from a collapse.