by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 3, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Indigenous Autonomy

by Marcela Belchior / Adital via Intercontinental Cry

What would initially appear to be the end of the line for the culture and survival of the Krenak indigenous people, impacted by the pollution of the Rio Doce, from the Mariana tragedy, in southeastern Brazil [state of Minas Gerais], could rekindle a 25 year struggle. After being left unable to live without the water of the river, the Krenak population is mobilized around a possible solution for the continuity of the community: to expand the demarcated area of the indigenous territory in the region and to migrate to a new location.

In an interview with Adital, Eduardo Cerqueira, member of the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), Eastern Regional office, which comprises the states of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo and the extreme south of Bahia, affirms that, as a way to resist the tragedy, the Krenak community [is calling] on the federal government to expand the demarcated area into 12,000 adjacent hectares, embracing the region where the State Park of Sete Salões, one of the Units of Conservation of nature belonging to the Government of Minas Gerais, is currently located.

“We find the strategy interesting, given that the existing area no longer provides conditions for survival. Something must be done”, attests Cerqueira. At present, the demarcated area of Krenak territory covers 4700 hectares. In this zone, extending more than three kilometers along the Doce River have been impacted and rendered unfit for drinking, fishing, bathing and irrigating vegetation in the vicinity, in the municipality of Resplendor, where 126 Krenak families live.

The State Park Parque de Sete Salões was created in 1998, and includes the municipalities of Conselheiro Pena, Itueta and Santa Rita do Itueto, corresponding to one of the largest remnants of Atlantic Forest in eastern Minas Gerais, with mountains, forests and waterfalls. Besides this, the area demanded has potential for indigenous community tourism, receiving visitors and marketing crafts, without damage to the environment.

The territory of the Krenak population, in Minas Gerais, was demarcated in the 1990s, but the entire length of the park was excluded, which today could once again be placed on the agenda. In the early 2000s, the Indigenous people filed a claim with the National Indian Foundation (Funai) and the federal government conducted a technical study on the matter, which to date has not been published. In the opinion of the Krenak, now, the situation is more than appropriate to fulfill the historical demand of the population.

“Various indigenous leaders are concerned about the territorial question. Now, it is a matter of necessity for this concern to be the focus of discussion. (…) This part of the region was not affected by the tailings [pollution],” defends the indigenous advocate. According to the CIMI counselor, since the socioenvironmental tragedy, the indigenous peoples affected have been assisted with emergency support, by means of tank trucks supplying water, transfer of basic food baskets and financial support for the families, which would ensure the community’s survival only in the short term.

“This tragedy was intensified by a period of severe drought. For over a year there has been no rain in the region. Because of this, the tributaries of the Rio Doce are dry. (…) The terrain is not favorable to agriculture. Livestock would be the most common form of indigenous survival, but it is not possible, without water,” explains Cerqueira.

Geovani Krenak laments the death of the Rio Doce: “we are one, people and nature, only one,” he says. Photo: Reproduction.

UNDERSTANDING THE CASE

A torrent of mud composed of mining tailings (residual waste, impurities and [chemical] material used for flushing out minerals) has been flooding the 800 kilometer length of the Rio Doce since November 5, after the rupture of the Fundão dam, of the Samarco mining company. This is controlled by Vale, responsible for innumerable and grave socioenvironmental damages in Brazil, and the multinational Anglo-Australian BHP Billiton, two of the largest mining companies in the world.

In addition to burying an entire district, impacting several others and polluting the Rio Doce, extending through the states of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo and Bahia, the mud reached the sea over the weekend, even further amplifying the environmental damage, which could take more than two decades before signs of recovery even begin to present. In addition to the destruction of fauna and flora, seven deaths and 17 disappearances have so far been recorded.

KRENAK PEOPLE CLOSE ROAD IN PROTEST

Early last week, representatives of the Krenak indigenous people, whose tribe is situated on the banks of the Rio Doce, interrupted, in protest, the Vitória-Minas Railroad. Without water for more than a week, they said they would leave only when those responsible for the tragedy talk with them. “They destroyed our lives, they razed our culture and ignore us. This we do not accept,” asserted Aiah Krenak to the press.

Considered sacred, in a culture whose cosmological worldview is based on the interconnection between all beings – humans, plants, animals, etc., the river that flows through the tribe was utilized by 350 Indians, for consumption, bathing and cleansing. “With the people, this is not separate from us, the river, trees, the creatures. We are one, people and nature, only one”, says Geovani Krenak.

Krenak people protest on the Vitória-Minas Railroad. Photo: Reproduction.

Seated along the tracks, under a 41C. degree sun, Indians chanted music in gratitude to the river, in the Krenak language. “The river is beautiful. Thank you, God, for the river that feeds and bathes us. “The river is beautiful. Thank you, God, for our river, the river of all of us,” the words of shaman Ernani Krenak, 105 years of age, translated for the press.

His sister, Dekanira Krenak, 65 years old, is attentive to the impact of the death of the river affecting not only the indigenous peoples, being a source of resources for many communities. “It is not ‘us alone’, the whites who live on the riverbank are also in great need of this water, they coexist with this water, many fishermen [feed their] family with the fishes,” she points out.

Camped on site in tarpaulin shacks and sleeping mats in the open air, the Indians, now, must also face an unbearable swarm of insects. “It was never like this,” says Geovani Krenak. “These mosquitoes came with the polluted water, with fish that once fed us and that are now descending the river, dead, he reports.

Article originally published in Portuguese at

Adital. Translated to English for Intercontinental Cry by M.A. Kidd. Republished with permission of Intercontinental Cry.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 27, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest

By Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense via Intercontinental Cry

Image: Mural in São Paulo, Brazil (Photo: Monica Kaneko/flickr). Some Rights Reserved

Altamira, Brazil. The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) on Tuesday authorized the Belo Monte Dam’s operating license, which allows the dam’s reservoirs to be filled. The authorization was granted despite clear noncompliance with conditions necessary to guarantee the life, health and integrity of affected communities; the same conditions that IBAMA called essential in its technical report of September 22. IBAMA’s decision makes no reference to conditions needed to protect affected indigenous peoples.

“We can’t believe it,” said Antonia Melo, leader of Movimiento Xingú Vivo para Siempre, who was displaced by the dam’s construction. “This is a crime. Granting the license for this monster was an irresponsible decision on the part of the government and IBAMA. The president of IBAMA was in Altamira on November 5 and received a large variety of complaints. Everyone – riverside residents, indigenous representatives, fishermen, and members of the movement – talked about the negative impacts we’re living with. And now they grant the license with more conditions, which will only continue to be violated.”

In an official letter to IBAMA on November 12, the president of the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) concluded that conditions necessary for the protection of affected indigenous communities had clearly not been met. However, he gave free reign for the environmental authority to grant the operating license “if deemed appropriate.”

“The authorization clearly violates Brazil’s international human rights commitments, especially with respect to the indigenous communities of the Xingú River basin. Those affected populations are protected by precautionary measures granted in 2011 by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which the Brazilian government continues to ignore,” said María José Veramendi, attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA).

The license allows for the filling of two of the dam’s reservoirs on the Xingú River, an Amazon tributary. It is valid for six years and is subject to compliance with certain conditions; progress will be monitored through semiannual reports. Such conditions should have been met before the dam’s license was even considered, let alone granted.

“Environmental licensing is a way to mitigate the effects, control damage and minimize the risks that the dam’s operation entails for the community and the environment. By disrespecting and making flexible the licensing procedures, the government is allowing economic interests to prevail and ignoring its duty to protect the public interest,” said Raphaela Lopes, attorney with Justiça Global.

AIDA, Justiça Global, and the Para Society of Defense of Human Rights have argued on both national and international levels that the conditions needed for Belo Monte to obtain permission to operate have not been met. The project must still guarantee affected and displaced populations access to essential services such as clean water, sanitation, health services and other basic human rights.

“The authorization of Belo Monte, a project involved in widespread corruption scandals, contradicts President Rousseff’s recent statement before the United Nations, in which she declared that Brazil would not tolerate corruption, and would instead aspire to be a country where leaders behave in strict accordance with their duties. We hope that the Brazilian government comes to its senses, and begins to align its actions with its words,” said Astrid Puentes Riaño, co-director of AIDA.

The green light for Belo Monte couldn’t have come at a worse moment. On November 5th, two dams impounding mine waste—owned by Samarco, a company jointly overseen by Vale and BHP Billiton—broke in the city of Mariana, Minas Gerais, causing one of the greatest environmental disasters in the country’s history. A slow-moving flood of mud and toxic chemicals wiped out a village, left 11 dead and 12 missing, and affected the water supply of the entire region, destroying flora and fauna for hundreds of miles around. The toxic flood has since reached the sea. The company’s operating licenses had expired two years ago.

Approval of Belo Monte’s operating license comes just six days before the start of the Paris climate talks, the most important meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in recent history. Once in operation, Belo Monte will emit greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide and methane; as the world’s third-largest dam, it will become a significant contributor to climate change.

By authorizing Belo Monte, the government of Brazil is sending a terrible message to the world. Ignoring its international commitments to protect human rights and mitigate the effects of climate change, the government is instead providing an example of how energy should not be produced in the 21st Century.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 11, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

Elvira Nascimento

Cyntia Beltrão reports from Brazil on what may be the country’s worst environmental disaster ever, at the Samarco open pit project jointly owned by Vale and BHP Billiton:

Last Thursday, November 5th, two dams containing mine tailings and waste from iron ore mining burst, burying the small historic town of Bento Rodrigues, district of Mariana, Minas Gerais state. The village, founded by miners, used to gain its sustenance from family farming and from labor at cooperatives. For many years, the people successfully resisted efforts to expel them by the all-powerful mining company Vale (NYSE: VALE, formerly Vale do Rio Doce, after the same river now affected by the disaster). Now their land is covered in mud, with the full scale of the death toll and environmental impacts still unknown.

Officially there are almost thirty dead, including small children, with several still missing. The press and the government hide the true numbers. Independent journalists say that the number of victims is much larger.

The environmental damage is devastating. The mud formed by iron ore and silica slurry spread over 410 miles. It reached one of the largest Brazilian rivers, the Rio Doce (“Sweet River”), at the center of our fifth largest watershed. The Doce River already suffers from pollution, silting of margins, cattle grazing in the basin land, and several eucalyptus plantations that drain the land. This year Southeastern Brazil, a region with a normally mild climate, endured a devastating drought. Authorities imposed water rationing on several major cities. Meanwhile, miners contaminate ground water and exploit lands rich in springs. The Doce River, once great and powerful, is now almost dry, even in its estuary. The mud of mining waste further injures the life of the river.

We do not know if the mud is contaminated by mercury and arsenic. Samarco / Vale says it isn’t, but we know that its components, iron ore and silica, will form a cement in the already dying river. This “cement” will change the riverbed permanently, covering the natural bed and artificially leveling its structure. The mud is sterile, and nothing will grow where it was deposited. A fish kill is already occuring. We do not know the full extent of impacts on river life or for those who depend on the river’s waters.

Soon the dirty mud will reach the sea, where it will cause further damage, to the important Rio Doce estuary and to the ocean.

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 6, 2015 | Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the second in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the first part.

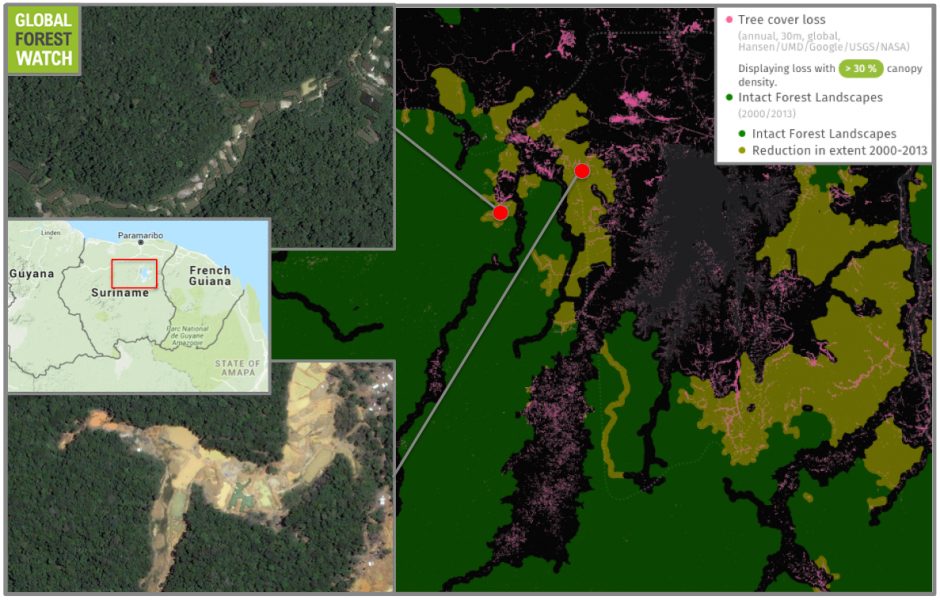

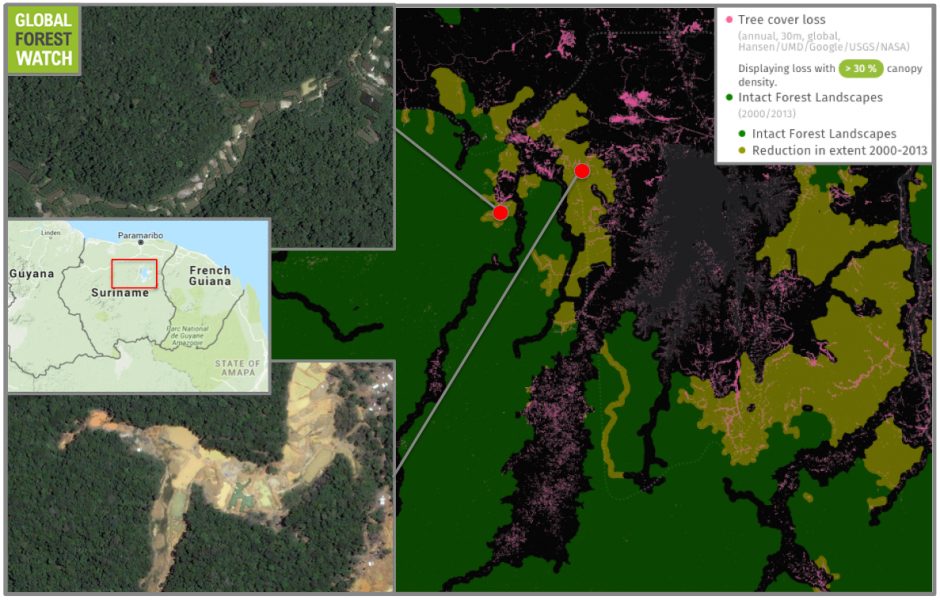

- Gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014.

- Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of local communities.

- With gold prices continuing to rise overall despite recent drops and Suriname’s political economy deeply entrenched in resource extraction, conservationists worry mining expansion will be hard to stop.

High gold prices combined with lax land use regulations have led to an explosion in mining in Suriname. A recent report by the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) finds that gold mining in the small South American country grew by 893 percent between 2000 and 2014, and is threatening the health and ways of life of many communities in the region.

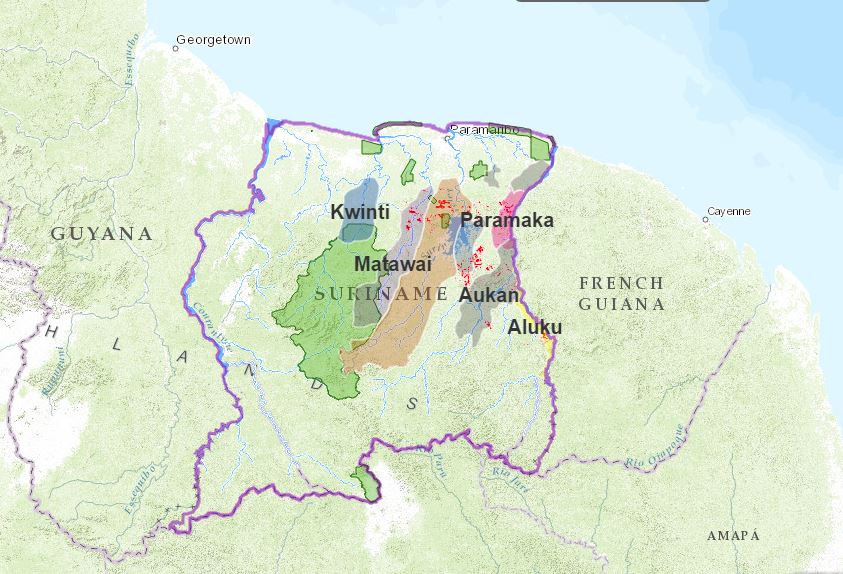

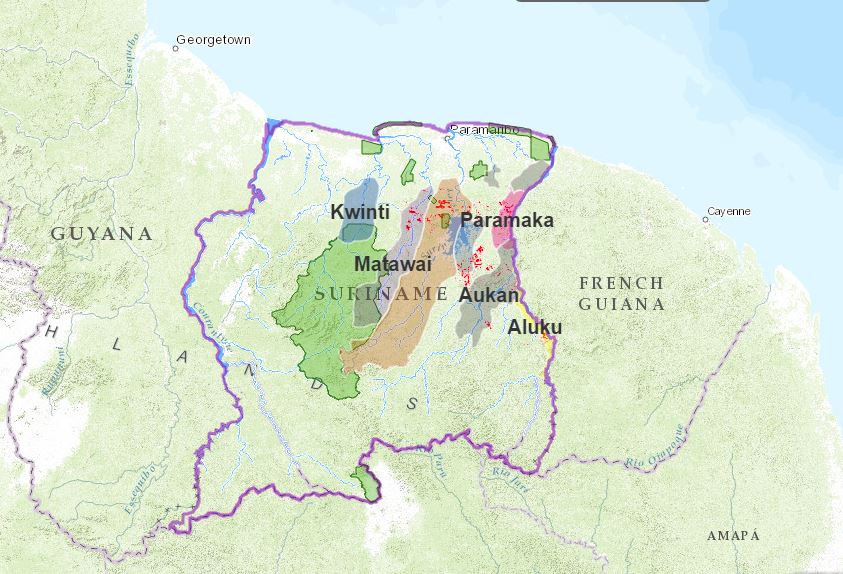

Much of the small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname is taking place within the boundaries of the traditional territories of the Maroons – descendants of formerly enslaved people of African heritage who escaped from plantations during Dutch colonial rule and established thriving communities in the country’s hinterlands after successfully fighting for their freedom.

Suriname’s six main Maroon communities all reside along rivers leading upstream deep into the rainforest, the report says. The majority of Maroons live in the central-eastern part of the country – where the mineral-rich Greenstone Belt and gold deposits are located. Through statistical analysis, the ACT discovered that encroachment of gold mining is significantly more severe within Maroon territories than outside of them. The team writes that only one Maroon community far from the Greenstone Belt is currently not seeing any gold mining on their lands.

Suriname boasts large tracts of intact forest landscapes (IFLs), which are continuous, undisturbed areas of primary forest. However, Global Forest Watch shows significant IFL degradation, with the country experiencing nearly 17,000 hectares of tree cover loss in its IFLs between 2001 and 2014. Much of this is happening in areas with gold mining activity.

Mining extent (red) in Maroon-occupied areas. Image courtesy of the ACT.

For some Maroon groups, small-scale gold mining has become a major component of their landscape and their daily lives. In many of their villages – particularly in Paramaka, Aukan and Matawai communities – villagers have become economically dependent on gold mining. Anthropologist Marieke Heemskerk has shown that in some Maroon villages, 70 to 80 percent of households get their regular income from family members working in gold mines. Villagers with informal concessions are able to collect fees from the garimpeiros – the Brazilian miners – and others working on their lands, and some have become quite wealthy as a result.

The Matawai Maroons who live along the Saramacca River in central Suriname, are among the smallest of the Maroon communities in terms of population. Their territory covers about 560,000 hectares and many of their villages are among the most remote and least-known in the country. Consequently, the Saramacca River, the surrounding ecosystem and the villages themselves remained relatively quiet and peaceful while other Maroon communities were contending with the pressures of inland colonization and resource extraction.

The northern portion of the Matawai territory, however, is located in the reaches of the Greenstone Belt. Being close to populated settlements, they are easily accessible via roads. This has allowed rapid expansion, with a number of the northern Matawai villages located at ground-zero for Suriname gold mining.

“According to our calculations derived from deforestation data, 81.51% of all deforestation in the Matawai territory is due to gold mining,” the report says.

Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.Community members from the Matawai villages of Boslanti and Vertrouw learning to use GPS technology in a village mapping exercise. Photo courtesy of the ACT.

Four Matawai villages – Nyun Jakobkondre, Balen, Misalibi, and Bilawatra have been particularly impacted by the large gold mines that encircle them. In fact, much of the small-scale mining in the region is done by Maroons themselves, which is threatening their traditional livelihoods of hunting, fishing, woodworking, etc.

“As more Maroons in the Matawai community and elsewhere are becoming dependent on partaking in mining for household income, these and other local practices are eroding,” said Rudo Kemper, GIS and Web Development Coordinator for the ACT. “Many of the Matawai youth in particular are no longer as interested in traditional activities, as they know that there are lucrative profits to be made working in the mines.”

To make matters worse, mining activities has polluted waterways with mercury, which is used to separate the gold ore from sediment. Mercury can act as a neurotoxin, and has contaminated river fish, which are no longer safe to eat. Arable land is also threatened. According to Kemper, “in areas like Nyun Jakobkondre, the gold mining is taking place so close to the village that fertile land for cultivation is becoming scarcer.”

Nieuw Koffiekamp, a village settled by Maroons after it was relocated because of floods, is now located right in the middle of one of the most prosperous and mineral-rich veins of the Greenstone Belt. Known as Gros Rosebel, the area was one of the first industrial mining concessions in Suriname. Villagers have been using the area for sustainable livelihoods for generations, but the ACT report alleges they were neither consulted with nor informed about the concession. Years later, the government set up a task force dedicated to relocating the village once more. The village continues to fight for its existence, despite being literally fenced in by gold mining activity. Community members argue they have the right to extract resources from their own land and thus participate in small-scale gold mining.

Even Brownsberg Nature Park, a 14,000-hectare reserve and popular tourist destination, hasn’t been spared from the clutches of mining. From early on, gold miners have been active within its boundaries, where an estimated 924 hectares of primary forest has been lost to gold mining. In 2012, deforestation in the park reached an all-time high, with 200 hectares of forest cleared. In that same year, public awareness about mining inside Brownsberg began increasing when WWF–Guianas published a report with aerial photography of the damage to the park. “Since then,” Kemper said, “the rates of small-scale mining in the boundaries of the park have dropped somewhat, although deforestation caused by mining in the park [continues] to expand.”

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining boom threatens communities in Suriname

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 5, 2015 | Property & Material Destruction

By Telesur

Venezuelan Energy Minister Luis Motta Domínguez reported that more than a dozen attacks had taken place in less than a week.

Venezuelan Electrical Energy Minister Luis Motta Dominguez reported that 13 attacks on Venezuela’s electrical grid took place over the last week, in an attempt to destabilize the Dec. 6 National Assembly elections.

Motta Dominguez presented the information at a press conference on Monday.

“The electrical system in the 18 days of October has received 13 attacks, 13 acts of sabotage, which also destabilizes the system,” he said. “They are intended to disturb and disrupt the elections on December 6.”

Dominguez said that “in previous elections, there were power outages just two days before the elections, and they are repeating the pattern.”

The minister of electrical energy reported the intrusion of armed people in the Corpoelec depot. | Photo: @MPPEE

According to Motta Dominguez the sabotage began on October 13 at a power plant in Zulia state, located in the northwestern corner of the country, where they cut part of the wiring. The owner showed pictures explaining a failure in the Guyana A line.

“The next attack was in Falcon (located in the northwest of the country), where a citizen was found manipulating a power transformer,” Motta Dominguez said. He also reported three attempts to hack the official website of Corpoelec, the state corporation responsible for Venezuelan power.

The minister reported an explosion and fire in a power transformer in Tachira – located in the Andes mountains, to the southwest of the country – which has affected two electrical substations. It was determined that the damage was caused by two bullet holes, leaving the people of Tachira without 200 megawatts of energy.

“Note that all the attacks are concentrated in Falcon, Zulia and Tachira, all border states,” he concluded. “It is no accident.”

Read more at: Massive Electrical Sabotage Reported in Venezuela