by DGR News Service | Dec 5, 2021 | Direct Action, Human Supremacy, Mining & Drilling, Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

Sentenced to eight years in prison for acts of sabotage, water protector Jessica Reznicek reflects on her faith-driven resistance.

By Cristina Yurena Zerr

This article was first published in the German newspaper taz, and has been translated and edited for Waging Nonviolence.

On June 28, the federal court in Des Moines, Iowa was silent and filled to capacity. Fifty people were there to witness the sentencing of 40-year old Jessica Reznicek, charged with “conspiracy to damage an energy production facility” and “malicious use of fire.” The prosecution, asking for an extended sentence, argued that Reznicek’s acts could be classified as domestic terrorism.

This was not the first time Reznicek had been on trial, but this time she was facing a prison sentence of up to 20 years.

Sitting across from her was U.S. District Court Judge Rebecca Goodgame Ebinger, the prosecutor and an FBI agent. Numerous police officers in bulletproof vests stood around the courtroom. The defendant was called upon to give her closing speech.

In her loud, clear voice, Reznicek told them about her strong connection to the water. In her childhood she regularly went to the river to swim and play. But that’s no longer possible, she said, because the two rivers that run through Des Moines — Iowa’s capital — are now poisoned by agrobusiness pesticides and waste.

It was for these very personal reasons that she decided to fight the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, Reznicek told those in attendance. At least eight leaks, she explained, had already occurred in 2017, with 20,983 gallons of crude oil leeching into soils and the waterways. “I was acting out of desperation,” she said, describing her motivations for sabotage.

“Indigenous tradition teaches us that water is life. Scripture teaches that in the beginning, God created the waters and the earth and that it was good.” With these words, she ended her closing argument. The prison sentence followed shortly thereafter: eight years in federal prison, three years of probation, and a restitution of $3,198,512.70 to the corporation Energy Transfer.

The Des Moines River (Cristina Yurena Zerr)

On July 24, 2017 — two years before sentencing — Jessica Reznicek can be seen in a shaky video with her activist partner Ruby Montoya, a former elementary school teacher who was 27 at the time. They stand in front of a group of journalists next to a busy street. The speech they give would drastically change their lives.

After several months of secretly sabotaging one of the country’s most controversial construction projects, the two women, whose paths would later part, went public. “We acted for our children because the world they inherit does not meet their needs. There are over five major bodies of water here in Iowa, and none of them are clean. After having explored and exhausted all avenues of process, including attending public hearings, gathering signatures for valid requests for environmental impact statements, participating in civil disobedience, hunger strikes, marches and rallies, boycotts and encampments, we saw the clear refusal of our government to hear the people’s demands.”

That’s why Reznicek and Montoya burned five machines at a pipeline construction site in Iowa on election night in November 2016. They would later change their methods, using a welding torch to dismantle the pipeline’s surface-mounted steel valves, delaying construction by weeks. “After the success of this peaceful action, we began to use this tactic up and down the pipeline, throughout Iowa,” the two women say.

But no media reported on their activities; the corporation cited other — false — reasons for the delay. When the activists noticed during an action that oil was already flowing in the pipes, they decided to go public, as they had to admit a kind of defeat.

The two women appear clear and determined on this day in the summer of 2017 as they take turns reciting their pre-written text. “If there are any regrets, it is that we did not act enough.” They end their speeches and are led away in handcuffs by three police officers.

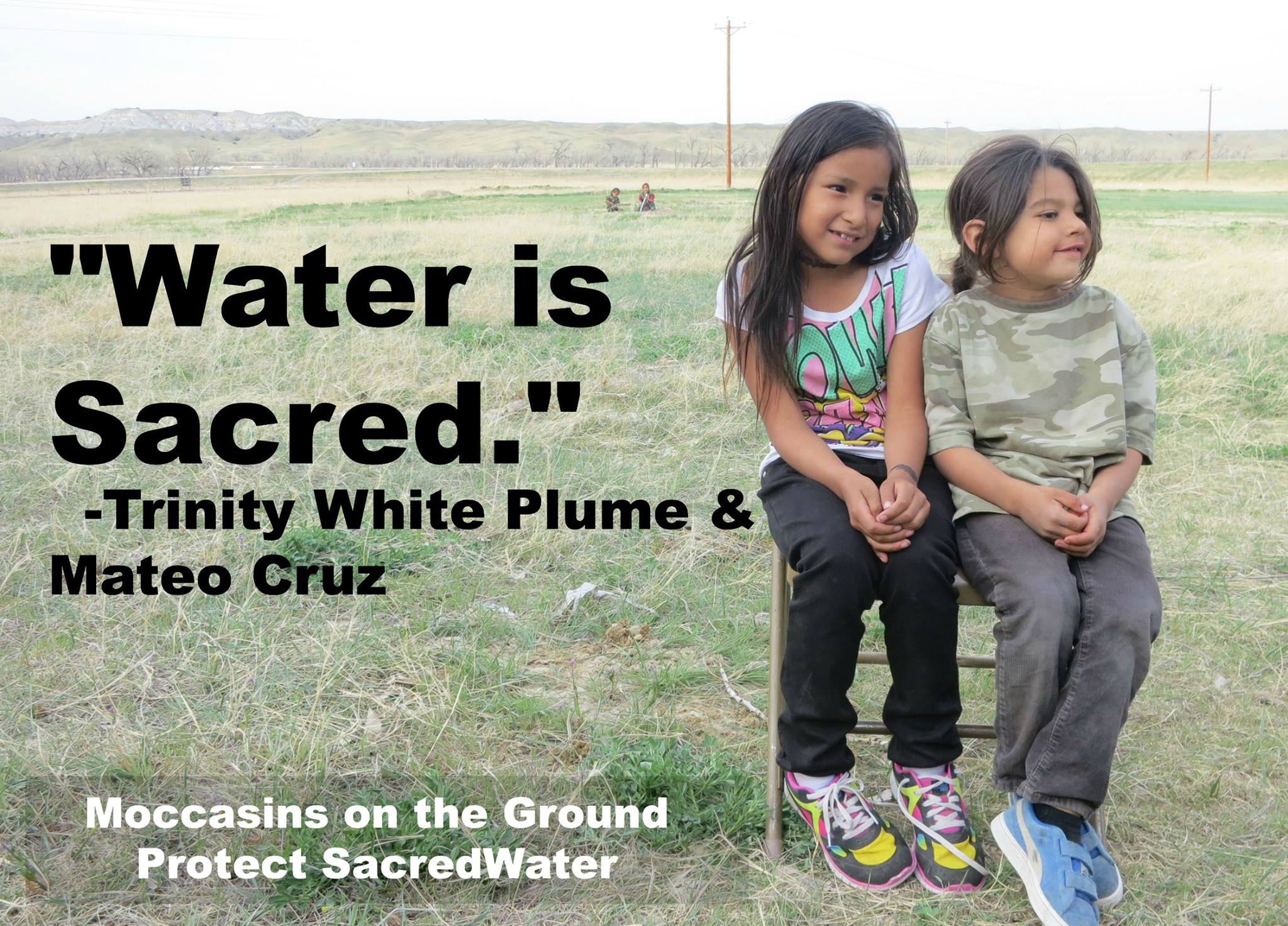

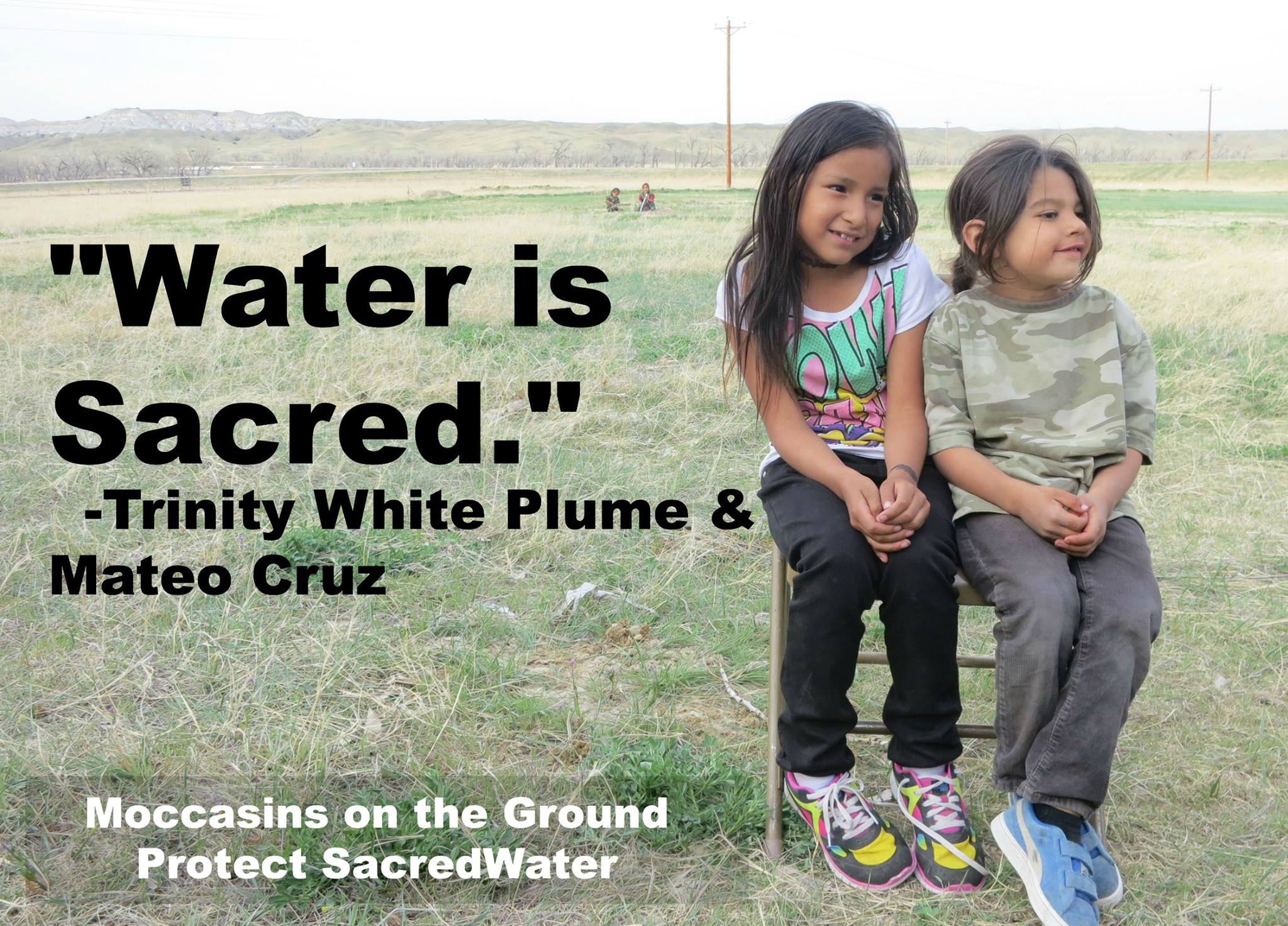

Using the slogan “Mni wiconi,” meaning “Water is Life,” in the Lakota (Sioux) language, a broad movement was organized in 2016 against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The protest of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe garnered national and international attention.

The tribe sees the construction of the pipeline as a threat to their water supply because the pipeline runs under Lake Oahe, which is near the reservation. Other bodies of water are also at risk because the pipeline crosses under rivers and lakes in many places, which could contaminate the drinking water of many people in the event of an accident. In addition, ancient burial sites and sacred places of great cultural value would be threatened by the construction. Opponents of the pipeline speak of ecological racism — not only because Indigenous rights to self-government would be curtailed, but also because the construction of so-called Man Camps (temporary container cities for construction workers who move from other states) would lead to prostitution and an increase in violence against Indigenous women.

Their government — the Sioux Tribe is a sovereign nation — issued a resolution back in 2015 saying the pipeline “poses a serious risk to the very survival of our tribe and […] would destroy valuable cultural resources.” Construction would also break the Fort Laramie Treaty, which guarantees them the “undisturbed use and occupation” of reservation land. But their arguments went unheard by both the company and the government.

The operating company said the pipeline would not harm the environment, would not affect Indigenous rights and would not pose a threat to drinking water supplies. But the protest, which stretches across several states along the pipeline, has developed into one of the largest environmental movements in the United States. Native Americans from different nations and reservations are joining, along with landowners, environmental organizations and left-wing autonomous movements.

Reznicek first heard about the pipeline when she was released from prison six years ago, after serving a two-month stint for her protest against a U.S. military weapons contractor in Omaha, Nebraska. An organizer from Standing Rock had come to Des Moines to mobilize people for the protest. “I decided that I wanted to learn more about Indigenous ceremony, understanding that I am a white person, I cannot just go in and express my demands. And I also wanted to focus on stopping the Dakota Access Pipeline Project. So I drove up to Standing Rock.”

Where it all began

On a road on the outskirts of Des Moines — a city home to numerous insurance companies — large trees tower above the wooden row houses, providing shade on a hot July day.

Above the porch of one of the houses hangs a small sign that reads “Catholic Worker House.” In front of the back part of the building are tables and benches with people sitting on them. Music is playing, people are singing, someone is asleep on a bench.

In the kitchen of the house, Jessica Reznicek stands in front of the stove and slices five chicken breasts, freeing the meat from the bones. Next to them is a large pot of mashed potatoes, into which she generously spreads butter. “Our guests love butter,” Reznicek laughs. The kitchen looks as if many meals have been cooked there. Posters with anti-war messages and protest slogans are hung around the small room. On the windowsill in front of Reznicek is a statue of a bishop with a rosary around his neck.

Twice a week, Jessica Reznicek cooks for the homeless guests who come here. Usually they eat together in the living room, but since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the food is distributed through the window.

“I like the days when I’m in charge of the kitchen. It takes my mind off all the things that are going on in my head,” Reznicek says as she begins washing a mountain of dishes.

Two years have passed since her protests were made public. A year ago, Jessica Reznicek moved back into the community, spending time there on house arrest. Here, where it all began, her long journey ends. She has one week left before needing to report to prison.

Just before the food is served, the kitchen and living room fill up. Two of Reznicek’s friends are there, residents of the house and volunteers from outside — together they begin to serve food to the guests.

Reznicek has been in and out of the house for 10 years. Most people know her story: “The one who blew up the pipeline?” asks Jimmy — one of the homeless guests — laughing as he tastes the still-warm mashed potatoes. The fact that she will soon be gone saddens many of the residents. For the majority of them, prison is a familiar place. But no one here has been incarcerated as long as Jessica Reznicek will be.

The Dingman House, named after a late bishop in Des Moines, is one of four side-by-side buildings of the Catholic Worker community. Christianity and anarchism meet here. In these self-organized “houses of hospitality,” which function independently of the church, people live and work among the poor in the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount. The Christian message of social justice and solidarity with the marginalized becomes everyday practice. There is not much overlap with the institutional Catholic Church. In the bathroom, where homeless guests can shower, there are free condoms; trans people find shelter here and women sometimes lead church services.

Preparations for prison

The Berrigan House across the street — named after two priests who became known for their actions of civil disobedience against the Vietnam War — has always been a place of resistance, where protest actions are planned and activists find shelter. This is where Reznicek prepared her actions against the pipeline.

As in the house next door, the walls are covered with posters calling for resistance against war, racism and injustice. It is a colorful, chaotic and untidy atmosphere. Reznicek and her friends Alex and Monty sit at the table in the living room. The two are among her closest supporters. They just had a video conversation with Reznicek’s lawyer to discuss the final steps before she goes to jail.

A month after Reznicek is sentenced to eight years in prison, they launched a campaign called “Water Defenders Are Never Terrorists.” Within a few weeks, they were able to collect thousands of signatures. Their goal: a petition to President Joe Biden and Congress demanding the terrorism charges be dropped.

The list of things to do before Reznicek goes to prison is long: return the electronic ankle bracelet, pick up the copy of her high school transcript she needs so she won’t have to attend classes in jail. T-shirts demanding her release are to be printed. Reznicek also wants to develop photos that Alex will later send to her in prison so she can decorate her cell with them. But they also want to see her favorite musical Rent, go dancing one more time, invite friends and celebrate. There is a lot of laughter when the three get together.

Jessica Reznicek’s supporters Monty and Alex in the Christian Berrigan House. (Cristina Yurena Zerr)

After the meeting, Jessica Reznicek packs a vacuum cleaner and cleaning supplies and heads out. With permission from her probation officer, she started cleaning private homes a year ago. She also worked at a pizzeria from time to time.

Why is Jessica Reznicek willing to spend eight years of her life in prison because of her commitment to clean water? She was studying political science in Des Moines and married when she learned about the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. Shortly after, she decided to go to New York for the protests. This meant the end of her marriage. From the East Coast, she began a new life of sorts, always on the move, searching for a way to make her contribution to a more just world.

Reznicek traveled twice to Palestine and Israel, where she was deported for protesting in solidarity with the Palestinian people. She visited the Zapatistas in Mexico and spent time in Central America with the Indigenous people of Guatemala. In South Korea, she protested the construction of a U.S. Navy base. “So I feel like all of these experiences culminated at this point in my life when I heard about the Dakota Access Pipeline.”

The Catholic Worker community in Des Moines was central to her politicization. She stumbled upon the organization after returning to Iowa from New York. There begins what she later calls a conversion: a return to the Christian faith and her Catholic roots. At the same time, this means a radicalization in the struggle against injustice: Jesus Christ is seen Catholic Workers as a revolutionary who stood up for the disenfranchised, for the weak and the poor. He wanted to drive the kings from their thrones and bring justice. And he died on the cross without resisting his judgement.

Three months after Jessica Reznicek made her actions public in 2017, the Berrigan home was surrounded by the FBI. “It was like 4:30 in the morning when they were pounding on the door. The house was actually shaking. I ran downstairs and could see around 50 agents through the window with big guns and vests.”

When she opened the door, the house was stormed by about 50 uniforms. She was thrown to the ground and held at gunpoint, she said.

She then spent a year in hiding, calling it her wanderings. “I wasn’t necessarily underground. I think that I was running and I was hiding, but it was not exclusively from the federal government. I was not hiding from prison. I was hiding from everything.”

When she broke down after 10 months in Colorado, she finally realized she needed help. It won’t come from people or places, Reznicek says, but from her relationship with God. After this experience, she realized she wanted to live in a place where she could encounter God, so she decided to enter a Benedictine convent as a novice. But no sooner does she arrive than Reznicek is again picked up by the FBI and charged. They send her back to Des Moines — to the Berrigan home — to await the verdict under house arrest.

For the last four days before she goes to prison, Jessica Reznicek was given permission to visit the sisters at the convent community in Duluth. After her incarceration, she would like to move there or — if that’s not possible — live as close to the convent as she can.

On August 11th, Benedictine sisters drove Jessica Reznicek to the women’s prison in Wascea, Minnesota, four hours away. There, 714 women currently live behind the walls and fences.

Three hundred miles to the north is the town of Bemidji, home of Energy Transfer, the energy company to which Reznicek will be in debt for the rest of her life. A new pipeline called Line 3 has been under construction at this location for several years. As with the Dakota Access Pipeline, the region’s Indigenous inhabitants — the Anishinaabe and Ojibwe tribes — will be most affected by the project.

“Today I feel sad to be saying my final goodbyes to loved ones,” Reznicek said. “I am strengthened, however, knowing that I’m still standing with integrity during this very important moment in history, as there truly is no other place to be standing at a time like this.”

With these words she takes leave of her friends and turns to face the prison gates.

by DGR News Service | Sep 23, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Toxification

This article originally appeared in Resilience.

Editor’s note: In order for the planet to survive, we must act in its defense. We can not rely on governments or corporations to do it. This is why Deep Green Resistance is organizing actions to confront the power structures—patriarchy, capitalism, colonialism, and civilization—largely responsible for the plunder of land and people.

By Alan Jay Richard

This is a story of victory for the earth and of the end of the Keystone XL pipeline. It also involves the Dakota Access pipeline and the Standing Rock Lakota reservation, indeed the entire world, all of which is threatened by our desperate last burst of fossil fuel exploitation. It is a story of what the dogged persistence and creativity of indigenous people and their allies can do against the kind of power we’ve been told is impossible to resist. But it’s a story without a guaranteed ending. The ending depends on us.

In 2004, small indigenous nations living near the Alberta Tar Sands project, the largest unconventional oil extraction effort in the world, began reaching out for help. Not only was the project interfering with their water, fishing, and hunting infrastructure, but rare and unusual cancers were appearing. They contacted policy experts at the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in Washington, D.C., who met with them in 2005 and saw photographic documentation of the devastation. These experts began to gather data and to raise awareness in the United States, on whose special refineries the project relied. Experts focused on the unique risks posed by tar sands at every stage of production, including extraction, transportation, and refinement. It wasn’t enough, but without the testimony and photographs supplied by indigenous people, experts would not have noticed for some time.

In 2008, approximately two dozen people from indigenous nations and environmental activist groups met to develop an overall strategy. The groups decided that the most promising activist target was the Keystone XL (KXL) pipeline, proposed by the giant TransCanada (now TC Energy) corporation to move the tar sands to refineries on the Texas Gulf Coast. Stopping the pipeline would rob the Tar Sands project of financial justification. The unusually expensive techniques required for extracting, transporting, and refining tar sands made them unusable when the global barrel price was low, and any increases in the cost of production would make investors flee.

This small group of people had almost no support. Going up against the Keystone XL pipeline meant taking on the Republican Party, half the Democratic Party, the U.S. government, the Canadian government, and the entire oil industry. But with the presence of indigenous organizers in this group, they soon discovered they had something far more important.

Attendees at the meeting began spreading the word. Clayton Thomas-Muller, a climate activist belonging to the Columb Cree Nation of Manitoba and an attendee, noticed that the pipeline would be running through the Oglala aquifer, a route that, in addition to being an environmental scourge, also threatened indigenous sovereignty. He began using his existing connections from previous anti-pipeline campaigns in indigenous nations to persuade tribal councils to pass resolutions opposing KXL, which they took directly to President Obama in 2011. He continued to work on tribal organizing throughout the effort to stop KXL. By 2010, Jane Kleeb of Bold Nebraska became aware of the Keystone XL threat. She attended the first State Department hearing on the pipeline in York, Nebraska in May out of curiosity without even knowing what tar sands were. At the hearing, she noticed that over 100 farmers and ranchers spoke out individually against the pipeline project and the only person speaking for it represented a union of construction workers on the pipeline. Kleeb thought the pipeline could be stopped if she could persuade Nebraska’s increasingly resistant farmers and ranchers to join indigenous people and environmentalists. To do this, she relied on indigenous support, including Muller’s. As a result, 150 tribes from the United States and Canada met in her state to sign an agreement opposing pipeline construction. The indigenous people she worked with also gave her good organizing and spiritual advice. First, stay rooted in real, concrete stories, not abstract principles. Second, never give up. The latter was remarkable guidance, especially coming from people who have endured what indigenous people in North America have endured.

The pipeline rose to national awareness in 2011, when former NASA climate scientist James Hansen wrote an essay arguing that it would be “game over for the climate” if the Alberta tar sands were fully developed. After this, 350.org got involved. They arranged for scores of celebrities to engage in civil disobedience in front of the White House. Here in Texas, Cindy Spoon, a graduate student at the University of North Texas, co-founded the Tar Sands Blockade after the White House protests and, following Kleeb’s lead, began organizing local pipeline resistance in communities along the Texas portion of the planned route. The Tar Sands Blockade, and the Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance that grew out of it, used bold, theatrical, and courageous tactics to block construction of the pipeline. Cindy also followed the guidance Kleeb had received from indigenous people in Nebraska, to stay rooted in stories and never give up. Tar Sands Blockade kept the issue in the news in Texas and Oklahoma, and occasionally in the national news, long after President Obama had already approved construction of the southern half. And we cost TC Energy a lot of money.

Cindy Spoon personally recruited a friend of mine and fellow activist for an arrest-risking direct action effort. I attended a training camp she organized and eventually got myself arrested at a KXL pumping station under construction in Seminole County, Oklahoma. Indigenous people were crucial agents in this experience. I and my colleague were thrown into what turned out to be the “Indian tank” at the county jail. The local Seminole men in jail with us that day were neither surprised to hear about the utterly unprincipled way power works in the United States, nor surprised to find us to be relatively naïve about it. But the men who spoke most freely with us also insisted on another kind of power. One guy wanted to form a circle and have each of us read something from the Bible that meant something to us and explain what it meant. During one of his turns, he quoted a verse from Matthew 19 about all things being possible with God. He looked at us and said, “this means you keep going, no matter what.” Stay rooted in real stories, and never give up.

For years after the intense efforts of 2011 and 2012, the fight against the KXL remained precarious. President Obama temporarily delayed it, but Trump attempted to accelerate it. Indigenous groups continued to resist, leading efforts against the northern half of the pipeline. And then indigenous people broadened the fight, linking it to the Dakota Pipeline resistance on the Standing Rock reservation, where the effort took on a more explicit indigenous spiritual context. In the morning, Lakota women walked to Cannonball River for a water ceremony. At dawn, local people chanted in the Lakota language. At night, Lakota elders tended a sacred fire, saying “Water is life. Defend the sacred.” In December 2016, Chief Arvol Looking Horse, 19th keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe and Bundle, visited the camp where his son was a leader. Reminding those present of the millions of attacks on the integrity of the earth community, he insisted that power lies in the common indigenous commitment to the sacredness of the physical world. He gave the same guidance Jane Kleeb had received from indigenous activists. Our struggle, he said, must be tireless and “prayer-filled,” rooted in stories drawn from experience, and we must never give up. He reassured them they would be victorious because, though people may believe this isn’t their fight, “Standing Rock is everywhere.” This sentence was, I have heard from friends who were present, the missing piece of the puzzle, exposing the unreality of indifference. Yes. It is everywhere. Nowhere on earth is safe from this threat, and we are all in the midst of it.

In January 2021, President Biden signed an executive order revoking the permit for the last phase of the KXL pipeline. By this time, investors had already been fleeing. The efforts of Clayton Thomas-Muller, Jane Kleeb, Cindy Spoon and indigenous activists across the pipeline route were bearing fruit. On June 9, TC Energy (TransCanada) abandoned the project. With the Keystone XL dead, the Alberta Tar Sands is likely to follow.

The Dakota Access pipeline, however, remains active. The sacred water on which the people of Standing Rock depend remains threatened. We can celebrate a genuine victory with the end of the KXL and it is appropriate to be grateful for the indigenous guidance responsible for this victory. Nevertheless, the struggle continues and it is our struggle, not just someone else’s. We may be afraid to feel ourselves in the midst of it, but we are. The guidance remains true:

Stay rooted in real stories. Never give up. Standing Rock is everywhere.

by DGR News Service | Jun 17, 2014 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling

Deep Green Resistance is dedicated to the fight against industrial civilization and its legacy of racism, patriarchy, and colonialism. For this reason, DGR would like to publicly state its support for the Oglala Lakota in their current fight against the genocidal mining operations of the Cameco Corporation.

Cameco is currently attempting to expand its already illegal resource extraction campaign despite undeniable evidence that their abuse of the Earth is leading to increased rates of cancer, diabetes, and other life-threatening illnesses among the Lakota people.

The only acceptable action on the part of the Cameco Corporation is immediate cessation of any and all mining activities in the ancestral home of the Lakota people; anything else will be met with resistance, and DGR will lend whatever support it can to those on the front lines.

The indigenous peoples of this land have always been at the forefront of the struggle against the dominant culture’s ecocidal violence, and DGR would like to offer its support and encouragement to Debra White Plume, the Lakota activist group Owe Aku, and all other indigenous women and men fighting for the future of the planet. The time for resistance is long past, and we are thankful every day that the Earth has warriors like the Oglala Lakota fighting in its defense.

For more information, please visit Owe Aku International at http://oweakuinternational.org/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 2, 2013 | Indigenous Autonomy, Obstruction & Occupation

By J. G. / Deep Roots Collective

Monday morning September 2nd protestors swarmed and created a road block for cars leaving Whiteclay. Activists marched through the town and blocked entrances into the various liquor stores. Today’s action is part of an ongoing campaign to stop liquid genocide on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

The town of Whiteclay lies less than 300 feet from the border of Pine Ridge, where the sale and consumption of alcohol is prohibited. While Whiteclay has a population of 14, there are 4 liquor stores in the town, selling 13,000 can of beer each day mostly to the Oglala Lakota in Pine Ridge making $34 million in revenue annually.

Lauren Lorenruiz came from Salt Lake City, Utah to stand in opposition to liquor sales, “The reason I am here today is because Whiteclay is poison…What we are seeing is a place of exploitation, a place of wrong-doing. These kinds of establishments are designed solely to destroy people so its profit over people and its inherently wrong… It has been tearing apart the Lakota people for over 100 years and we’re ready for it to stop.”

A protestor from Connecticut stated, “As an ally to the Lakota people I think that solidarity is in sacrifice. As a non- native white person I have a form of privilege that I can bring attention to these issues.”

Two days previous, people from all over the country marched into White Clay for the second annual Women’s March and Day of Peace to bring awareness of the harms caused by alcoholism.

Even with the highly contentious vote to legalize alcohol in Pine Ridge Pine Ridge activists remain undeterred. Present at the Women’s Day of Peace, Oglala Lakota activist Olowan Martinez spoke to how alcohol has had a devastating impact on the people of Pine Ridge and continues to be used as a chemical weapon of genocide against the Lakota people and their culture to this day, “They use alcohol to trick us and now we trick ourselves.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 24, 2013 | Human Supremacy

By Lexy Garza and Rachel

View video of the event at the Deep Green Resistance Youtube channel

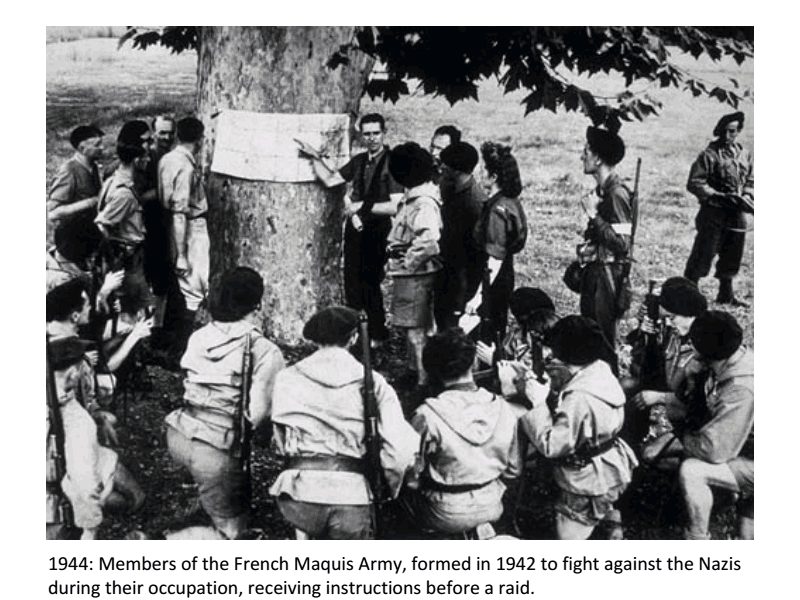

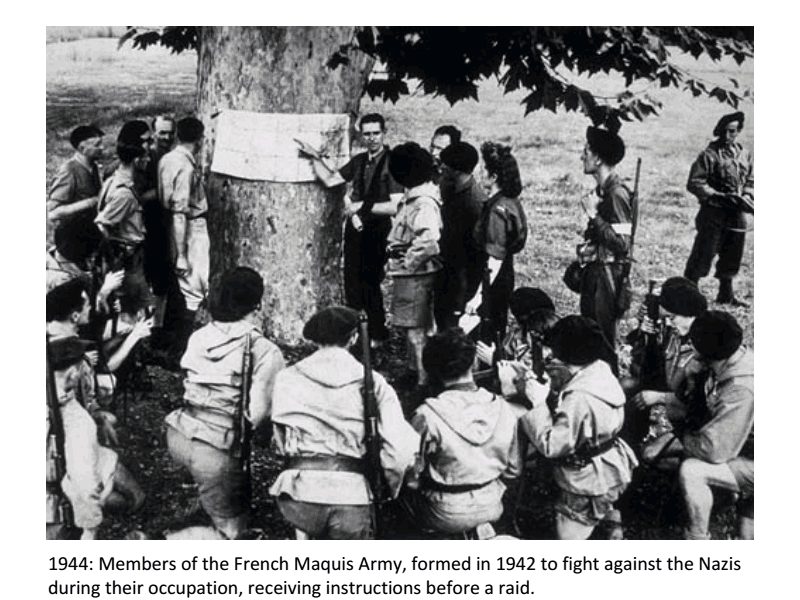

Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

This quote by Spanish writer and philosopher George Santayana was posted on the wall in my high school history classroom. The idea, as my history teacher explained, it is that learning about history is vitally important because by knowing and understanding past events, we can actively shape the future. According to my teacher’s view, at least the view he shared with his students, the history in our textbooks is objective, time-tested truth, and nothing more nor less.

Some time after that class ended, I read another George Santayana quote, which is somewhat less often quoted, “history is a pack of lies about things that never happened told by people who weren’t there.”

Taken at face value, this statement goes to the other extreme and completely writes off the history we’re taught as lies, as intentionally untrue. I think that both these views let us off too easy, because the stories we call history, and the process by which some stories become the dominant stories, the ones we teach to our children, is more complex than the dichotomy of truth vs. lie.

Another often repeated idea about history is that it’s “written by the victors.” This gets closer to a nuanced look at what history means and what it does.

For instance, in 1890 the US army massacred 300 Lakota men, women and children at Wounded Knee, burying them in a mass grave. Twenty US soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor for this atrocity, just one of the many perpetrated by European colonizers who called genocide their manifest destiny. The vast majority of “historical” accounts throughout the decades don’t call Wounded Knee a massacre; they lend it a false legitimacy by calling it a battle. The same goes for the Washita massacre carried out by Custer in 1868. So-called historical accounts refer to this event as the Battle of the Washita. As it’s been said, “When a white army battles Indians and wins, it is called a great victory, but if they lose it is called a massacre.”

These and countless other examples show us that what we call history is certainly not objective truth. The voices of the colonized and the conquered do not get included in the version of the past we call history. That’s what it means to be colonized: genocide means the mass killing and eradication of entire peoples, but it also means the eradication of their culture, their stories, and the power to pass those stories on to future generations.

In his book A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn wrote, “I knew that a historian (or a journalist, or anyone telling a story) was forced to choose, out of an infinite number of facts, what to present, what to omit. And that decision inevitably would reflect, whether consciously or not, the interests of the historian.”

So this is the question we want to address– What interests are represented by the dominant story? Whose interests does the dominant story serve, and whose does it erase?

But before we get to that, there’s another question– Why does any of this matter? Why does it matter where our popular history comes from, and why does it matter what gets omitted?

It matters because our understanding of history informs our strategy in the present. Our ability to imagine what is possible is shaped by our understanding of the past. Therefore, our actions in the present are shaped by our understanding of the past. And right now, our actions in the present could not be more crucial.

200 species are pushed to extinction every single day. [1]

A Cornell research survey that found that water, air, and soil pollution account for 40% of human deaths worldwide [2]

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change states unequivocally that for the climate to remain stable and in their words “manageable,” the average temperature rise cannot exceed 2 degrees Celsius. Yet virtually nothing decisive has been done to try and meet that 2 degrees Celsius limit. [3]

According to the International Energy Agency’s November 2010 assessment, which does not include the self-reinforcing feedback loops that many experts anticipate, the global average temperature rise of Earth will hit the 3.5 degrees Celsius mark in 2035, and some climate models have predicted a rise of 11 degrees by the end of the century. [4]

In the short term, we’re already seeing the beginnings of the floods, fires, droughts, and superstorms.

Plankton populations are collapsing, amphibian populations are collapsing, 90% of large fish in the ocean are gone [5].

The fabric of life on Earth is collapsing and humans are not exempt, though the effects aren’t obvious from here behind the military barricade of the US Empire.

The Global Humanitarian Forum recently put out a prediction that, by 2030, 100 million people could be dying annually as a direct result of climate change, based on how many are currently being killed due to climate change, which is around 300,000 per year [6].

We, not only the human we, but the global we of life on Earth are facing a crisis on a scale the planet has never seen, and the reality is that we are losing this fight right now.

With all the world at stake, we need to form and implement a strategy that can work. The latest Climate Commission report has warned that 80% of global fossil fuel reserves will have to stay in the ground if the planet is to avoid dangerous climate change. Our governments and the corporations that run them plan to burn every last drop of oil, every last speck of coal, and every last whiff of gas, and right now, the strategy of the mainstream environmental movement has no hope of stopping them, or even of substantially slowing them down.

If we are to avert the catastrophic dismemberment of our planet, we will need to see past the lies of the dominant culture and recognize its narratives—the mainstream narratives of social change—for the falsity that they are. Ultimately, we will need to move beyond legal & aboveground tactics as a whole movement, and make room for strategic sabotage and militant action in the tool chest of resistance.

References

[1] UN Environment Programme, Ahmed Djoghlaf, http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/aug/16/nature-economic-security

[2][http://news.cornell.edu/stories/2007/08/pollution-causes-40-percent-deaths-worldwide-study-finds] (direct link to report: http://www.springerlink.com/content/101592/).

[3] UN Framework Convention on Climate Change**

[4] International Energy Agency’s November 2010 assessment**

[5] http://www.cnn.com/2003/TECH/science/05/14/coolsc.disappearingfish/

[6] http://www.ghf-ge.org/human-impact-report.pdf

This is the first part of a two piece series on strategic resistance by Lexy Garza and Rachel. Continue to Part II

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org