by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 24, 2013 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

By Thistle Pettersen and Beth Ulion / Deep Green Resistance

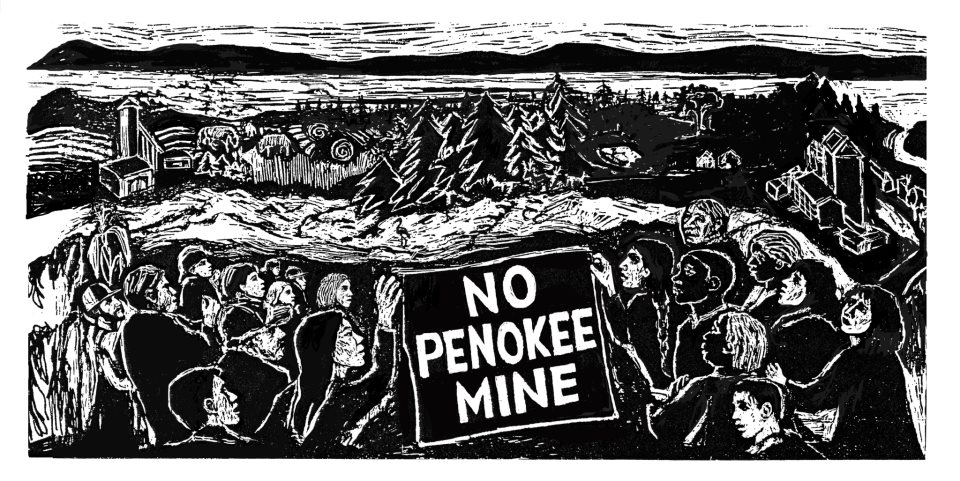

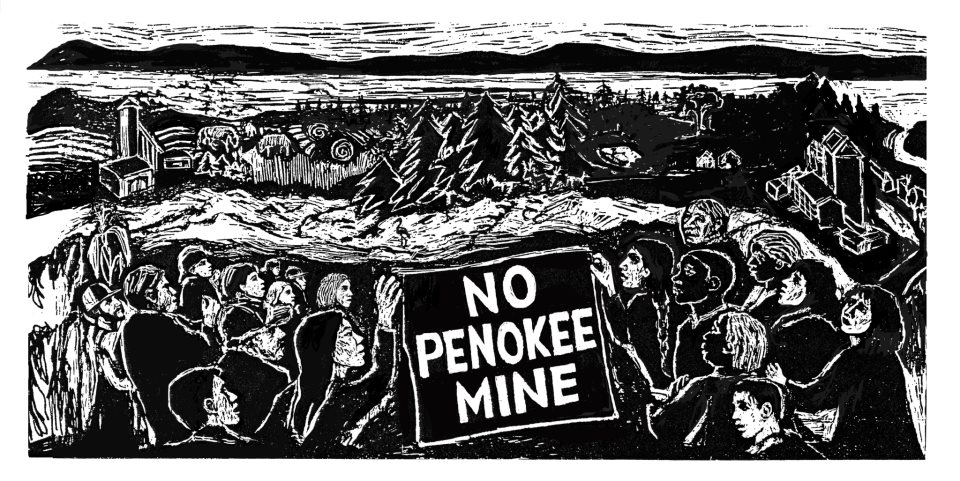

A proposed iron mining effort would create the largest open pit mine in the world in northern Wisconsin.The 22,000 acres of mountain-top removal-style strip mining would potentially dump millions of tons of waste rock into the headwaters of the Bad River, polluting everything downstream including beautiful Copper Falls State Park, the Bad River Ojibwe Reservation, crucial wetland Kakagon Sloughs, and Lake Superior.

Many local residents fear that the huge mine will eat into nearby sulfide-mineral deposits, causing sulfuric acid mine drainage to leach into the surrounding watershed for decades.

The Wisconsin State legislature recently slashed environmental regulations in an attempt to make an easier entry for Gogebic Taconite (G-Tac), a Florida-based company owned by the Cline Group, is also well known for its coal mining operations in Illinois and West Virginia.

This is just one struggle in a worldwide battle against extreme resource extraction – but this time, it’s one we can win. Activists have a good head start, and there is a lot of dedicated support for those who are planning to occupy the Penokee Hills to deliver a message to G-Tac: we are drawing a line in the sand, and they will not be allowed one inch of this sacred land.

Bad River Tribal members are asking for solidarity from allies all over the Great Lakes Region.

Activists will gather at the Central Wisconsin Action Camp May 17-19th in Stevens Point, WI.

This is a great opportunity to meet others from around Central and South Wisconsin and throughout the midwest, and build direct-action skills for this historic struggle.

The crew organizing this event could really use a little help, too! Especially for those of you who are in or near Stevens Point or Madison, assistance in organizing logistics like camp setup, food, etc, as well as additional skill trainings, are greatly appreciated!

As capacity may be somewhat limited, and with the intention of building a solid group of anti-mining activists who can move into the future together, organizers are asking that you please register on the website:

centralwiactioncamp.wordpress.com

centralwiactioncamp@gmail.com

If you are unable to make it to the action camp, you can still plug in by traveling even farther north the following weekend, May 24th-26th for a benefit variety show and camp out at Copper Falls State Park. The variety show fund raiser will be at the Bad River Lodge and Casino on Friday night, the 24th. Money raised at this community-building event will go towards the Penokee Hills Education Project to defend the land from harmful mining. The Red Cliff hoop dancers, Thistle and Thorns, and Barbara With are all acts on this bill that will make it a very special night of performances and comradeship with locals.

The campout is being organized by members of the Bad River Tribe and will include tours of the land where the mine is slated to be put in. Mike Wiggins, chair of the Bad River, will greet and spend time with campers. It will be a beautiful and educational weekend in the great north woods!

If you are interested in attending either of these two weekends or both of them, please contact DGR member Thistle Pettersen to plug into ride shares happening from Madison. thistle@riseup.net.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 21, 2013 | ANALYSIS, Mining & Drilling

By Joshua Headley / Deep Green Resistance New York

We ought not at least to delay dispersing a set of plausible fallacies about the economy of fuel, and the discovery of substitutes [for coal], which at present obscure the critical nature of the question, and are eagerly passed about among those who like to believe that we have an indefinite period of prosperity before us. –William Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question (1865)

There are, at present, many myths about green energy and its efficiency to address the demands and needs of our burgeoning industrial civilization, the least of which is that a switch to “renewable” energy will significantly reduce our dependency on, and consumption of, fossil fuels.

The opposite is true. If we study the actual productive processes required for current “renewable” energies (solar, wind, biofuel, etc.) we see that fossil fuels and their infrastructure are not only crucial but are also wholly fundamental to their development. To continue to use the words “renewable” and “clean” to describe such energy processes does a great disservice for generating the type of informed and rational decision-making required at our current junction.

To take one example – the production of turbines and the allocation of land necessary for the development, processing, distribution and storage of “renewable” wind energy. From the mining of rare metals, to the production of the turbines, to the transportation of various parts (weighing thousands of tons) to a central location, all the way up to the continued maintenance of the structure after its completion – wind energy requires industrial infrastructure (i.e. fossil fuels) in every step of the process.

If the conception of wind energy only involves the pristine image of wind turbines spinning, ever so wonderfully, along a beautiful coast or grassland, it’s not too hard to understand why so many of us hold green energy so highly as an alternative to fossil fuels. Noticeably absent in this conception, though, are the images of everything it took to get to that endpoint (which aren’t beautiful images to see at all and is largely the reason why wind energy isn’t marketed that way).

Because of the rapid growth and expansion of industrial civilization in the last two centuries, we are long past the days of easy accessible resources. If you take a look at the type of mining operations and drilling operations currently sustaining our way of life you will readily see degradation and devastation on unconscionable scales. This is our reality and these processes will not change no matter what our ends are – these processes are the degree with which “basic” extraction of all of the fundamental metals, minerals, and resources we are familiar with currently take place.

In much the same way that the absurdities of tar sands extraction, mountaintop removal, and hydraulic fracturing are plainly obvious, so too are the continued mining operations and refining processes of copper, silver, aluminum, zinc, etc. (all essential to the development of solar panels and wind turbines).

It is not enough – given our current situation and its dire implications – to just look at the pretty pictures and ignore everything else. All this does, as wonderfully reaffirming and uplifting as it may be, is keep us bound in delusions and false hopes. As Jevons affirms, the questions we have before us are of such overwhelming importance that it does no good to continue to delay dispersing plausible fallacies. If we wish to go anywhere from here, we absolutely need uncompromising (and often brutal) truth.

A common argument among proponents of supposed “green” energy – often prevalent among those who do understand the inherent destructive processes of fuels, mining and industry – is that by simply putting an end to capitalism and its profit motive, we will have the capacity to plan for the efficient and proper management of remaining fossil fuels.

However, the efficient use of a resource does not actually result in its decreased consumption, and we owe evidence of that to William Stanley Jevons’ work The Coal Question. Written in 1865 (during a time of such great progress that criticisms were unfathomable to most), Jevons devoted his study to questioning Britain’s heavy reliance on coal and how the implication of reaching its limits could threaten the empire. Many covered topics in this text have influenced the way in which many of us today discuss the issues of peak oil and sustainability – he wrote on the limits to growth, overshoot, energy return on energy input, taxation of resources and resource alternatives.

In the chapter, “Of the economy of fuel,” Jevons addresses the idea of efficiency directly. Prevalent at the time was the thought that the failing supply of coal would be met with new modes of using it, therefore leading to a stationary or diminished consumption. Making sure to distinguish between private consumption of coal (which accounted for less than one-third of total coal consumption) and the economy of coal in manufactures (the remaining two-thirds), he explained that we can see how new modes of economy lead to an increase of consumption according to parallel instances. He writes:

The economy of labor effected by the introduction of new machinery throws laborers out of employment for the moment. But such is the increased demand for the cheapened products, that eventually the sphere of employment is greatly widened. Often the very laborers whose labor is saved find their more efficient labor more demanded than before.

The same principle applies to the use of coal (and in our case, the use of fossil fuels more generally) – it is the very economy of their use that leads to their extensive consumption. This is known as the Jevons Paradox, and as it can be applied to coal and fossil fuels, it so rightfully can be (and should be) applied in our discussions of “green” and “renewable” energies – noting again that fossil fuels are never completely absent in the productive processes of these energy sources.

We can try to assert, given the general care we all wish to take in moving forward to avert catastrophic climate change, that much diligence will be taken for the efficient use of remaining resources but without the direct questioning of consumption our attempts are meaningless. Historically, in many varying industries and circumstances, efficiency does not solve the problem of consumption – it exasperates it. There is no guarantee that “green” energies will keep consumption levels stationary let alone result in a reduction of consumption (an obvious necessity if we are planning for a sustainable future).

Jevons continues, “Suppose our progress to be checked within half a century, yet by that time our consumption will probably be three or four times what it now is; there is nothing impossible or improbable in this; it is a moderate supposition, considering that our consumption has increased eight-fold in the last sixty years. But how shortened and darkened will the prospects of the country appear, with mines already deep, fuel dear, and yet a high rate of consumption to keep up if we are not to retrograde.”

Writing in 1865, Jevons could not have fathomed the level of growth that we have attained today but that doesn’t mean his early warnings of Britain’s use of coal should be wholly discarded. If anything, the continued rise and dominance of industrial civilization over nearly all of the earth’s land and people makes his arguments ever more pertinent to our present situation.

Based on current emissions of carbon alone (not factoring in the reaching of tipping points and various feedback loops) and the best science readily available, our time frame for action to avert catastrophic climate change is anywhere between 15-28 years. However, as has been true with every scientific estimate up to this point, it is impossible to predict that rate at which these various processes will occur and largely our estimates fall extremely short. It is quite probable that we are likely to reach the point of irreversible runaway warming sooner rather than later.

Suppose our progress and industrial capitalism could be checked within the next ten years, yet by that time our consumption could double and the state of the climate could be exponentially more unfavorable than it is now – what would be the capacity for which we could meaningfully engage in any amount of industrial production? Would it even be in the realm of possibility to implement large-scale overhauls towards “green” energy? Without a meaningful and drastic decrease in consumption habits (remembering most of this occurs in industry and not personal lifestyles) and a subsequent decrease in dependency on industrial infrastructure, the prospects of our future are severely shortened and darkened.

BREAKDOWN is a biweekly column by Joshua Headley, a writer and activist in New York City, exploring the intricacies of collapse and the inadequacy of prevalent ideologies, strategies, and solutions to the problems of industrial civilization.

Photo by Andreas Gücklhorn on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 21, 2013 | Indigenous Autonomy, Protests & Symbolic Acts

By Survival International

As Brazil marks its annual ‘Day of the Indian’ today, hundreds of Brazilian Indians of various tribes invaded and occupied part of the country’s Congress this week, to protest at attempts to change the law regarding their land rights.

The Indians are outraged about a proposed constitutional amendment that would weaken their hold on their territories. They fear that ‘PEC 215’, by giving Congress power in the demarcation process, will cause further delays and obstacles to the recognition and protection of their ancestral land.

The Indians say they will not stop protesting until the planned amendment is scrapped.

Alongside Directive 303, amendment 215 is a result of pressure by Brazil’s powerful rural lobby group which includes many politicians who own ranches on indigenous land.

It could spell disaster for thousands of indigenous peoples who are waiting for the government to fulfil its legal duty to map out their lands.

Whilst Brazil’s sugar-cane industry booms, benefitting from plantations on indigenous land, the Guarani Indians of Mato Grosso do Sul suffer from malnutrition, violence, murder and one of the highest suicide rates in the world. Guarani spokesman Tonico Benites explains, ‘Guarani suicide is happening and increasing as a result of the delay in identifying and demarcating our ancestral land’.

Elsewhere in the country, indigenous peoples are fighting for their land to be protected from waves of invasions at the hands of loggers, ranchers, miners and settlers. The Awá Indians in the north-eastern Amazon are now Earth’s most threatened tribe. The uncontacted Awá will not survive unless action is taken now to protect their forest.

Yesterday, the Yanomami association Hutukara organized a demonstration of about 400 Yanomami in Ajarani, in the eastern part of their territory. This area has been occupied by cattle ranchers for decades. Despite a court order to leave, they have refused to do so.

Hutukara’s vice-president Maurício Ye’kuana said, ‘The presence of the ranchers in the region has caused huge harm to the indigenous people and to the environment, such as deforestation and burning of the forest. We want an end to this.’

Meanwhile Munduruku Indians have been protesting for months against the proposal to build a series of hydro-electric dams along the Tapajós, a large tributary of the Amazon.

Last month the military and police launched ‘Operation Tapajós’ in an attempt to stamp out the Indians’ protests against the arrival of technical teams surveying the area for the first dam, São Luis do Tapajós.

On 16 April a federal judge ordered that this operation be suspended, and that the Indians and other affected communities be consulted before technical studies are carried out. The judge also ruled that an environmental impact assessment should be carried out on the cumulative impact of all the dams planned for the Tapajós.

From Survival International: http://www.survivalinternational.org/news/9172

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 17, 2013 | Strategy & Analysis

By now we should all be familiar with what’s at stake. The horrific statistics—200 species driven extinct daily, every child born with hundreds of toxic chemicals already in their bodies, every living system on the planet in decline—haunt us as we go about our work in a world that refuses to hear, listen, or act on them. After decades of traditional organizing and activist work, we’re beginning to come to terms with the need for a dramatic shift in strategy and tactics, and indeed in how we conceptualize the task before us.

It is not enough any longer (if it ever was) to build a reformist social movement, one more faction among many attempting to fix the failings within our society. With industrial civilization literally tearing apart the biosphere and skinning the planet alive, we can afford no other goal than to build a resistance movement capable of—and determined to succeed in—bringing down industrial civilization, by any means necessary.

We know this will require decisive underground action to be successful, and starting all but from scratch, this begins with promoting the need for militant resistance; trying to garner acceptance and normalization of the fact that without militant resistance—including sabotage and direct attacks on key nodes of industrial infrastructure—there is little, if any, hope that earth will survive much longer.

However, the pervasive ideology of the dominant culture leaves most of its members unwilling to even consider dialogue on the topic of militant resistance, much less adopting it as a strategy. One manifestation of this is the all-too-widely held belief that nonviolent resistance is more always more effective than violent resistance.

The most common explanation provided to justify this idea is that violent movements alienate potential supporters, while nonviolent movements are more likely to mobilize “the masses” around a cause, and that without mass participation and support, there can be no social or political change.

For example, several years ago two university professors conducted a statistical comparison of violent and nonviolent social movements in the 20th century, with the goal of determining the relative effectiveness of violent and nonviolent strategies. The survey was limited to anti-occupation & anti-colonial movements, as well as those that sought regime change or the end of an oppressive government. In 2011, the findings were published in a book called Why Civil Resistance Works. The authors concluded that, based on their data, nonviolent movements are statistically twice as effective as violent ones, and they explained this as being due to the propensity of nonviolent movements to elicit greater participation from the general population.

An underlying premise—unstated by those who espouse this line of reasoning—is that without popular support and engagement, movements cannot achieve their aims. While it is certainly the case that mass movements can be effective in creating social change, that is by no means always the case. The simple (and perhaps unfortunate) truth is that some causes will never enjoy popular support, regardless of what strategies or tactics they use. In a deeply, fundamentally misogynistic and racist culture, a culture that has as its foundation the slow dismemberment of the living world, the support and enthusiasm of the majority is by no means a signifier that a cause is a worthwhile one. And a lack of that popular support doesn’t mean a cause or movement isn’t righteous.

We would do well to remember that the majority of Germans didn’t support any resistance against the Nazis, and even a decade after the war ended and the atrocities of the Nazi genocide were well known, most Germans still opposed even the idea of a theoretical resistance to Nazi rule.

Similarly, a movement to dismantle civilization will never enjoy the support or participation of a mass movement. Far too many people are completely dependent upon it, or too attached to the material privilege and prosperity it affords them for their allegiance, or simply unable to question the only way of life they ever known, or all of the above. The truth is that any effort to stop civilization will always be a minority, not only without popular support, but likely directly opposed by the majority of the dominant culture. This is a sobering fact that, while perhaps difficult to come to terms with, we need to accept and build our strategy around. Rather than starting from the abstract position of “nonviolence works” and building a strategy for our movement from there, we should start with the material realities of our situation—the time, resources, and numbers of participants available to us.

This is why framing the whole discussion within a ‘violent/nonviolent’ dichotomy is problematic. When we reduce the complexities of entire movements and strategies down to the simple categories of ‘violent’ and ‘nonviolent,’ we relegate all discussion about strategy to theoretical and conceptual realms, glossing almost entirely over the nuances and dynamics of particular struggles. And it’s these details that determine what strategies will be effective. If we want to decide on an effective strategy, we need to first examine closely and critically our situation, and determine from there what will be most effective.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we know that we won’t ever have the numbers of participants required for strategies of popular nonviolence. It doesn’t matter how effective nonviolent strategies and movements may be in other situations; we’re not in those situations and without the necessary numbers, nonviolent strategies hold no promise for us. We need to halt industrial civilization in its tracks, and that position isn’t one that can muster a mass movement.

Which brings us back to the need for decisive underground action. Unlike nonviolent strategy, which is dependent upon mobilize huge numbers of participants, a strategy of militant attacks on key nodes of industrial infrastructures—a strategy of decisive ecological warfare—doesn’t require mass participation or support. Coordinated and repeated attacks against systemic weak points or bottle necks can cause systems disruption and cascading systems failure, resulting in the collapse of industrial activity and civilization—which must be our goal if we profess any love for life on this planet.

Given that industrial infrastructure is the foundational pillar of support for the function and existence of industrial civilization, and that these infrastructure networks are sprawling, fragile, and poorly protected; coordinated sabotage presents the best strategy and hope for a movement to bring down civilization.

Recognizing the need for underground action and the key role it must play if we’re to be successful as a movement doesn’t mean disavowing all nonviolent action. We need bio-diverse movements and cultures of resistance, and for some objectives nonviolent strategies are appropriate and smart and should be pursued. But we also need to recognize the limitations of various strategies, and especially the limitations of our own situation.

To reiterate, we will only ever be a small movement; we’ll never enjoy the support and participation required by mass nonviolent campaigns. The unfortunate truth is that most folks won’t ever willingly challenge the basis of their own way of life, much less organize to confront power and dismantle that way of life.

We also don’t have much time: according to conservative estimates, we have five years to stop the development and construction of fossil fuel infrastructure before being locked into catastrophic runaway climate change.

Those limitations—the lack of numbers and the short time available, combined with the fragility and vulnerability of the physical infrastructures of planetary murder—are what should point us away from mass nonviolence and towards a strategy of strategic sabotage. Coming to terms with and acting upon that reality isn’t always easy, but the sooner we’re able to let go of our misinformed and misguided dreams of a mass movement, the sooner we can start the real work of building a serious resistance movement.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 11, 2013 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Protests & Symbolic Acts

By Imani Altemus-Williams / Waging Nonviolence

At 9 am on an overcast morning in paradise, hundreds of protesters gathered in traditional Hawaiian chant and prayer. Upon hearing the sound of the conch shell, known here as Pū, the protesters followed a group of women towards Monsanto’s grounds.

“A’ole GMO,” cried the mothers as they marched alongside Monsanto’s cornfields, located only feet from their homes on Molokai, one of the smallest of Hawaii’s main islands. In a tiny, tropical corner of the Pacific that has warded off tourism and development, Monsanto’s fields are one of only a few corporate entities that separates the bare terrain of the mountains and oceans.

This spirited march was the last of a series of protests on the five Hawaiian islands that Monsanto and other biotech companies have turned into the world’s ground zero for chemical testing and food engineering. Hawai’i is currently at the epicenter of the debate over genetically modified organisms, generally shortened to GMOs. Because Hawai’i is geographically isolated from the broader public, it is an ideal location for conducting chemical experiments. The island chain’s climate and abundant natural resources have lured five of the world’s largest biotech chemical corporations: Monsanto, Syngenta, Dow AgroSciences, DuPont Pioneer and BASF. In the past 20 years, these chemical companies have performed over 5,000 open-field-test experiments of pesticide-resistant crops on an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 acres of Hawaiian land without any disclosure, making the place and its people a guinea pig for biotech engineering.

The presence of these corporations has propelled one of the largest movement mobilizations in Hawai’i in decades. Similar to the environmental and land sovereignty protests in Canada and the continental United States, the movement is influenced by indigenous culture.

“All of the resources that our kapuna [elders] gave to us, we need to take care of now for the next generation,” said Walter Ritte, a Hawai’i activist, speaking in part in the Hawaiian indigenous language.

“That is our kuleana [responsibility]. That is everybody’s kuleana.”

In Hawaiian indigenous culture, the very idea of GMOs is effectively sacrilegious.

“For Hawaii’s indigenous peoples, the concepts underlying genetic manipulation of life forms are offensive and contrary to the cultural values of aloha ‘ʻāina [love for the land],” wrote Mililani B. Trask, a native Hawaiian attorney.

Deadly practices

Monsanto has a long history of making chemicals that bring about devastation. The company participated in the Manhattan Project to help produce the atomic bomb during World War II. It developed the herbicide “Agent Orange” used by U.S. military forces during the Vietnam War, which caused an estimated half-million birth deformities. Most recently, Monsanto has driven thousands of farmers in India to take their own lives, often by drinking chemical insecticide, after the high cost of the company’s seeds forced them into unpayable debt.

The impacts of chemical testing and GMOs are immediate — and, in the long-term, could prove deadly. In Hawaii, Monsanto and other biotech corporations have sprayed over 70 different chemicals during field tests of genetically engineered crops, more chemical testing than in any other place in the world. Human studies have not been conducted on GMO foods, but animal experiments show that genetically modified foods lead to pre-cancerous cell growth, infertility, and severe damage to the kidneys, liver and large intestines. Additionally, the health risks of chemical herbicides sprayed onto GMO crops cause hormone disruption, cancer, neurological disorders and birth defects. In Hawaii, some open-field testing sites are near homes and schools. Prematurity, adult on-set diabetes and cancer rates have significantly increased in Hawai’i in the last ten years. Many residents fear chemical drift is poisoning them.

Monsanto’s agricultural procedures also enable the practice of monocropping, which contributes to environmental degradation, especially on an island like Hawai’i. Monocropping is an agricultural practice where one crop is repeatedly planted in the same spot, a system that strips the soil of its nutrients and drives farmers to use a herbicide called Roundup, which is linked to infertility. Farmers are also forced to use pesticides and fertilizers that cause climate change and reef damage, and that decrease the biodiversity of Hawai’i.

Food sovereignty as resistance

At the first of the series of marches against GMOs, organizers planted coconut trees in Haleiwa, a community on the north shore of Oahu Island. In the movement, protesting and acting as caretakers of the land are no longer viewed as separate actions, particularly in a region where Monsanto is leasing more than 1,000 acres of prime agricultural soil.

During the march, people chanted and held signs declaring, “Aloha ‘āina: De-occupy Hawai’i.”

The phrase aloha ‘āina is regularly seen and heard at anti-GMO protests. Today the words are defined as “love of the land,” but the phrase has also signified “love for the country.” Historically, it was commonly used by individuals and groups fighting for the restoration of the independent Hawaiian nation, and it is now frequently deployed at anti-GMO protests when people speak of Hawaiian sovereignty and independence.

After the protest, marchers gathered in Haleiwa Beach Park, where they performed speeches, music, spoken-word poetry and dance while sharing free locally grown food. The strategy of connecting with the land was also a feature of the subsequent protest on the Big Island, where people planted taro before the march, and also at the state capitol rally, where hundreds participated in the traditional process of pounding taro to make poi, a Polynesian staple food.

The import economy is a new reality for Hawaii, one directly tied to the imposition of modern food practices on the island. Ancient Hawai’i operated within the Ahupua’a system, a communal model of distributing land and work, which allowed the islands to be entirely self-sufficient.

“Private land ownership was unknown, and public, common use of the ahupua’a resources demanded that boundaries be drawn to include sufficient land for residence and cultivation, freshwater sources, shoreline and open ocean access,” explained Carol Silva, an historian and Hawaiian language professor.

Inspired by the Ahupua’a model, the food sovereignty movement is building an organic local system that fosters the connections between communities and their food — a way of resisting GMOs while simultaneously creating alternatives.

Colonial history

The decline of the Ahupua’a system didn’t only set Hawai’i on the path away from food sovereignty; it also destroyed the political independence of the now-U.S. state. And indeed, when protesters chant “aloha ‘āina” at anti-GMO marches, they are alluding to the fact that this fight isn’t only over competing visions of land use and food creation. It’s also a battle for the islands’ political sovereignty.

Historically, foreign corporate interests have repeatedly taken control of Hawai’i — and have exploited and mistreated the land and its people in the process.

“It’s a systemic problem and the GMO issue just happens to be at the forefront of public debate at the moment,” said Keoni Lee of ʻŌiwi TV. “ʻĀina [land] equals that which provides. Provides for who?”

The presence of Monsanto and the other chemical corporations is eerily reminiscent of the business interests that led to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Throughout the 19th century, the Hawaiian Kingdom was recognized as an independent nation. That reality changed in 1893, when a group of American businessmen and sugar planters orchestrated a U.S. Marine’s armed coup d’etat of the Hawaiian Kingdom government.

Five years later, the U.S. apprehended the islands for strategic military use during the Spanish-American War despite local resistance. Even then-President Grover Cleveland called the overthrow a “substantial wrong” and vowed to restore the Hawaiian kingdom. But the economic interests overpowered the political will, and Hawai’i remained a U.S. colony for the following 60 years.

The annexation of Hawai’i profited five sugarcane-manufacturing companies commonly referred to as the Big Five: Alexander & Baldwin, Amfac (American Factors), Castle & Cooke, C. Brewer, and Theo H. Davies. Most of the founders of these companies were missionaries who were actively involved in lobbying for the annexation of the Hawaiian islands in 1898. After the takeover, the Big Five manipulated great political power and influence in what was then considered the “Territory of Hawaii,” gaining unparalleled control of banking, shipping and importing on the island chain. The companies only sponsored white republicans in government, creating an oligarchy that threatened the labor force if it voted against their interests. The companies’ environmental practices, meanwhile, caused air and water pollution and altered the biodiversity of the land.

The current presence of the five-biotech chemical corporations in Hawai’i mirrors the political and economic colonialism of the Big Five in the early 20th century — particularly because Monsanto has become the largest employer on Molokai.

“There is no difference between the “Big Five” that actually ruled Hawai’i in the past,” said Walter Ritte. “Now it’s another “Big Five,” and they’re all chemical companies. So it’s almost like this is the same thing. It’s like déjàvu.”

Rising up

At the opening of this year’s legislative session on January 16, hundreds of farmers, students and residents marched to the state capitol for a rally titled “Idle No More: We the People.” There, agricultural specialist and food sovereignty activist Vandana Shiva, who traveled from India to Hawai’i for the event, addressed the crowd.

“I see Hawai’i not as a place where I come and people say, ‘Monsanto is the biggest employer,’ but people say, ‘this land, its biodiversity, our cultural heritage is our biggest employer,’” she said.

As she alluded to, a major obstacle facing the anti-GMO movement is the perception that the chemical corporations provide jobs that otherwise might not exist — an economic specter that the sugarcane companies also wielded to their advantage. Anti-GMO organizers are aware of how entrenched this power is.

“The things that we’re standing up against are really at the core of capitalism,” proclaimed Hawaiian rights activist Andre Perez at the rally.

Given the enormity of the enemy, anti-GMO activists are attacking the issue from a variety of fronts, including organizing mass education, advocating for non-GMO food sovereignty and pushing for legislative protections. Organizers see education, in particular, as the critical element to win this battle.

“Hawai’i has the cheapest form of democracy,” said Daniel Anthony, a young local activist and founder of a traditional poi business. “Here we can educate a million people, and Monsanto is out.”

Others are using art to educate the public, such as Hawaiian rapper Hood Prince, who rails against Monsanto in his song “Say No to GMO.” This movement is also educating the community through teach-ins and the free distribution of the newly released book Facing Hawaii’s Future: Essential Information about GMOs.

Hawai’i has already succeeded in protecting its traditional food from genetic engineering. Similar to the way the Big Five controlled varying sectors of society, the biotech engineering companies are financially linked to the local government, schools and university. Monsanto partially funds the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources at the University of Hawaii. The university and the Hawaii Agriculture Research Center began the process of genetically engineering taro in 2003 after the university patented three of its varieties. Once this information became widely known, it incited uproar of objection from the Hawaiian community. Taro holds spiritual significance in the islands’ indigenous culture, in which it is honored as the first Hawaiian ancestor in the creation story.

“It felt like we were being violated by the scientific community,” wrote Ritte in Facing Hawaii’s Future. “For the Hawaiian community, taro is not just a plant. It’s a family member. It’s our common ancestor ‘Haloa …. They weren’t satisfied with just taking our land; now they wanted to take our mana, our spirit too.”

The public outcry eventually drove the university to drop its patents.

Anti-GMO activists are hoping for further successes in stopping genetic food engineering. In the current legislative session, there are about a dozen proposed bills pushing GMO regulation, labeling and a ban on all imported GMO produce. These fights over mandating GMO labeling and regulation in Hawai’i may seem like a remote issue, but what happens on these isolated islands is pivotal for land sovereignty movements across the globe.

“These five major chemical companies chose us to be their center,” said Ritte. “So whatever we do is going to impact everybody in the world.”

From Waging Nonviolence: http://wagingnonviolence.org/feature/the-struggle-to-reclaim-paradise/