- A security crackdown in the Philippines targeting an armed communist insurgency has swept up environmental and land defenders in a raid on Oct. 31.

- International humanitarian and church groups have also been included in the military’s list of “legal front groups” of the outlawed New People’s Army and tied to terror financing.

- Security forces rounded up a total of 63 activists: 57 on the island of Negros and six in Manila. They include leaders of peasant groups, farmers, and anti-reclamation activists.

- At least six of the arrested critical groups are environmental and land defenders advocating for land campaigns on Negros and against the ongoing Manila Bay reclamation.

MANILA — Environment and land rights leaders were among the activists rounded up in a new wave of arrests in the Philippines as part of the government’s extensive counter-insurgency campaign to flush out sympathizers of the outlawed New People’s Army (NPA) while international humanitarian groups, alongside local church groups, were accused of being “legal communist fronts” and aiding terrorism.

A total of 57 activists were arrested on Oct. 31 in Negros, an island 850 kilometers (530 miles) from Manila, while another six were arrested in Manila on Nov. 5. Among the arrested are farmers and peasant group leaders fighting for their land rights in Negros Island and activists opposing the ongoing Manila Bay reclamation project. They were arrested in security crackdowns on major left-leaning organizations, with search warrants issued by a court in Metro Manila on Oct. 30.

Environmental groups have denounced the arrests, which they say involved “planting evidence” in the form of explosives and guns in the homes of activists. Kalikasan PNE, an environmental NGO, says the tactic is similar to President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, known locally as Tokhang, which has left nearly 6,000 people dead since 2016.

“We condemn this recent surge of Tokhang-style raids and arrests against land and environmental defenders and other activists by the police and military forces,” Clemente Bautista, international network coordinator of Kalikasan PNE, said in a statement. He added that the strategy “fits a national and global trend of criminalization of land rights and environmental activism not only in the Philippines but globally,” echoing the findings of the recent “Enemies of the State?” report by the environmental watchdog Global Witness.

“[M]any governments are manipulating their legal systems and intimidating defenders with aggressive criminal and civil cases, often to further the interests of big business,” the report says. “This often goes hand-in-hand with incendiary rhetoric that brands defenders as ‘terrorists’ or criminals in other guises, making attacks on them more likely and seemingly legitimate.”

International humanitarian organizations and church groups have also been branded by the Philippine military as “legal fronts” for the NPA, according to a list shown to lawmakers in a briefing on Nov. 6. The military identified 18 organizations — including Oxfam Philippines; the National Council of Churches in the Philippines (NCCP), a fellowship of Protestant and non-Catholic churches; and the Farmers Development Center (Fardec), a nonprofit — as “front organizations of local communist terrorist groups (CTG).”

In another list, Oxfam International and Oxfam UK were labeled as “foreign funding agencies wittingly or unwittingly providing funds to CTG front organizations.”

“Oxfam categorically denies these accusations,” the organization said in a statement, adding that the new development is a “troubling situation” that places “communities and partners we work with at risk.”

“In a country where poverty remains, and poor communities are continually struck by disasters, we strongly believe that organizations like ours should be encouraged, rather than hindered, from undertaking our programs,” Oxfam Philippines said.

The Department of National Defense and the military have since clarified that the list is “unverified” and that the organizations listed are “not red-tagged” — that is, not affiliated with the banned Communist Party and its armed wing, the NPA. Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana said the list was based on “documents captured from all operations in the country,” news outlet Rappler reported.

In April, the country’s police warned students about getting involved in potential communist groups outside schools, and the rhetoric heightened in August when the government accused some NGOs and state schools of being hotbeds of subversion. This is the first time, however, that international development organizations and church groups have landed on such a list.

Groups were on high alert as early as September after reports of possible raids circulated among them. Kalikasan PNE filed complaints with the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), and the group and its partners, Global Witness and the World Resources Institute (WRI), have also engaged in a series of public forums and dialogues with representatives of the U.S. State Department and U.S. Congress on Oct. 26 over the incidents.

Sixty-four local lawmakers, three belonging to the affected party-list groups, have also demanded an end to the government’s crackdown on activists, party-list groups Bayan Muna, Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU), and Gabriela Women’s Party. Both Bayan Muna and Gabriela are left-leaning organizations that currently hold congressional seats in the Philippines’ party-list system, in which underrepresented or single-issue parties receive a quota of congressional seats.

In Negros: Land rights leaders, party-list members arrested

The wave of arrests, however, is not new in Negros, where President Duterte dispatched seven military units and an additional 300 police personnel in August to quell a state of “lawlessness” that saw a spate of killings with 15 people gunned down in July alone.

Fifty-seven people were arrested as suspected members of the communist insurgency, while the military raided the offices of groups including the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW). Among those arrested were Danny Tabura of the KMU’s Negros chapter and John Milton Lozande, an NFSW representative who conducts land cultivation campaigns in Negros. These campaigns, locally called bungkalan, are a source of tension as they involve farmers taking over contested farmlands that are covered by the agrarian reform law but have yet to be titled and distributed. Lozande was eventually released alongside 48 other activists, leaving eight others who are still detained.

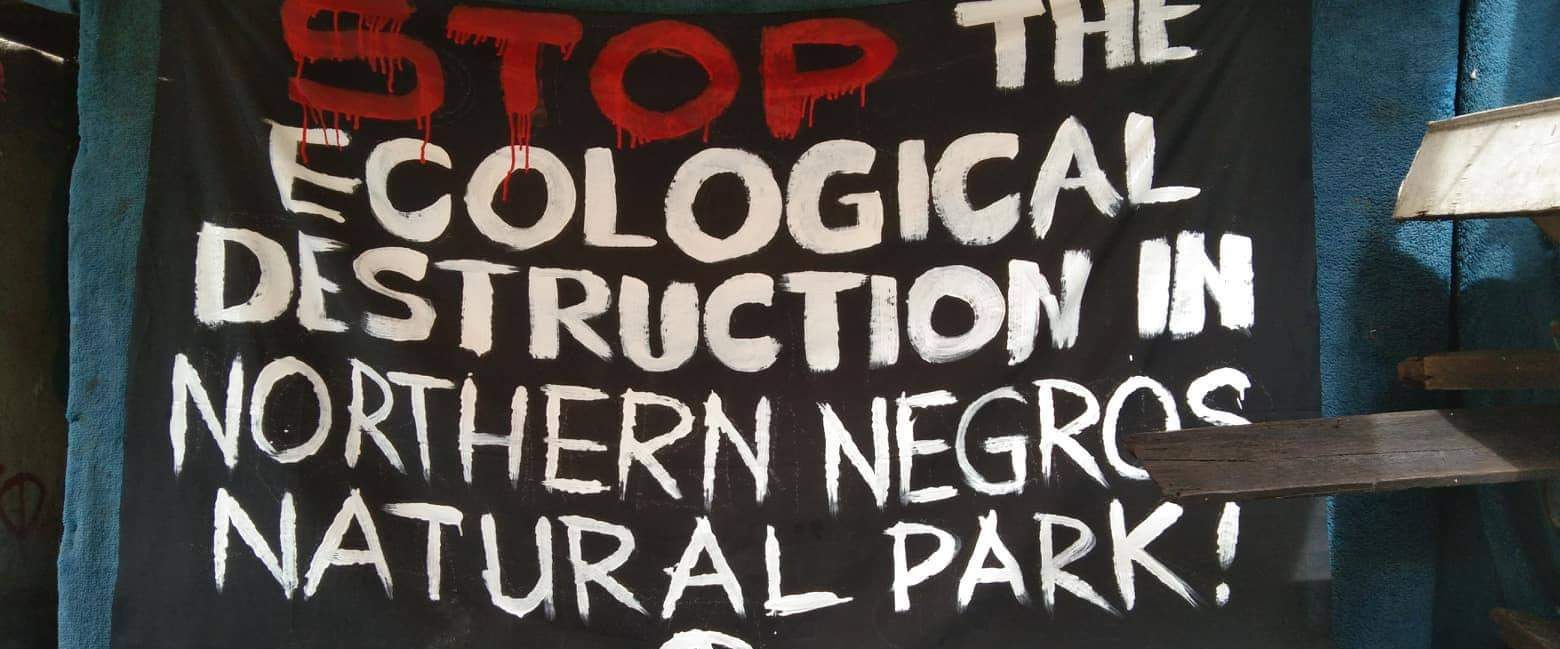

Nine sugarcane farmers and environmental defenders, including four women and two children, were killed in one such dispute in Sagay, a city in Negros, on Oct. 20, 2018. They were among the 30 environmental and land defenders killed in the Philippines that year, according to Global Witness, which named the country the most dangerous in the world for defenders. Since the Sagay massacre, the island has seen two waves of counter-insurgency campaigns, which the government called Sauron I and Sauron II, that resulted in the arrests of peasant group leaders and the killings of local officials, farmers and social workers.

Small farmers and indigenous peoples account for 81 percent of murdered land and environmental defenders under the Duterte administration, said Leon Dulce of Kalikasan PNE. “This shows that the unabated killings of farmers is the single biggest blow to the country’s environmental protection efforts,” he added. “Protecting the lives and rights of farmers will allow them to continue their innate role of protecting watersheds and agricultural lands.”

In Manila: Anti-reclamation activists rounded up

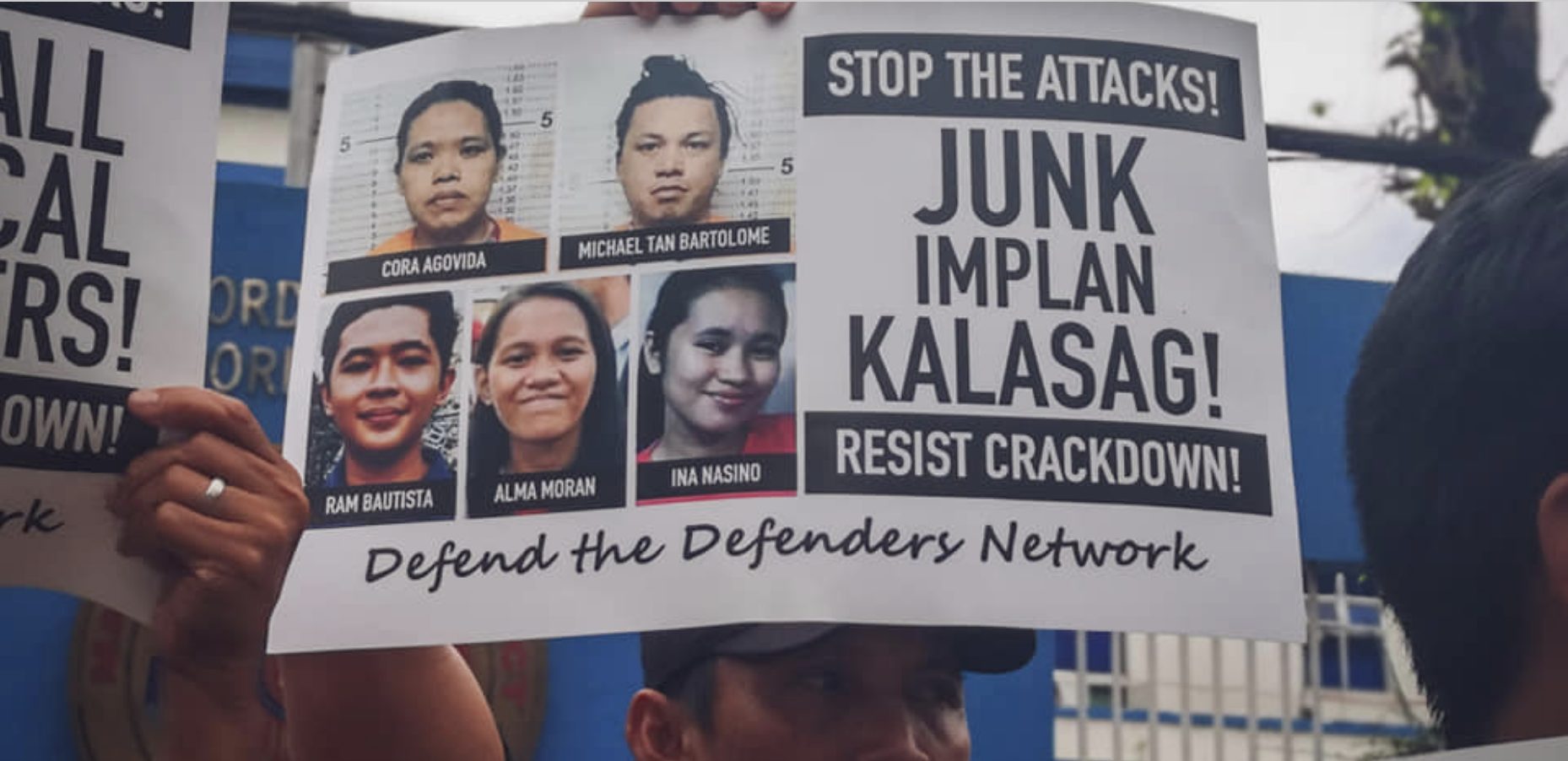

Of the six activists arrested in Manila, four were opponents of the ongoing Manila Bay reclamation project, which will cover 2,627 hectares (6,491 acres) of coastal and foreshore areas in the capital’s biggest body of water. Among them was Cora Agovida, a spokeswoman for Gabriela, the women’s party, and a campaigner against land reclamation in the capital’s bay. The three other anti-land reclamation activists arrested were Ram Carlo Bautista, Alma Moran and Reina Mae Nasino, all members of the Manila chapter of the Bayan Muna party.

All four are part of Manila Baywatch, a watchdog coalition of environmental and human rights groups monitoring the Manila Bay inter-agency rehabilitation program that Duterte created on Feb. 19. The rehabilitation cost of the bay is estimated at 47 billion pesos ($924 million) and includes massive relocation projects for illegal settlers. The grassroots campaign seeks to “ensure that the rehab program addresses the threats of ecological destruction, flooding, and community displacement posed by reclamation projects.”

“The Duterte administration is cracking down on Manila-based activists who exposed its sham Manila Bay rehab program for paving the way for reclamation development,” Dulce said. “The Manila Police District must be investigated and held accountable for their attacks are clearly meant to pave the way for reclamation and other infrastructure projects at all costs, including costing people’s rights and lives.”

Manila Bay, home to the Port of Manila, one of Asia’s oldest harbors and the heart of the Philippines’ shipping, industrial and commercial activities, is the site of 19 reclamation projects that are under development. Six of these projects are in the “detailed engineering stage,” or close to being implemented, according to data from the Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA).

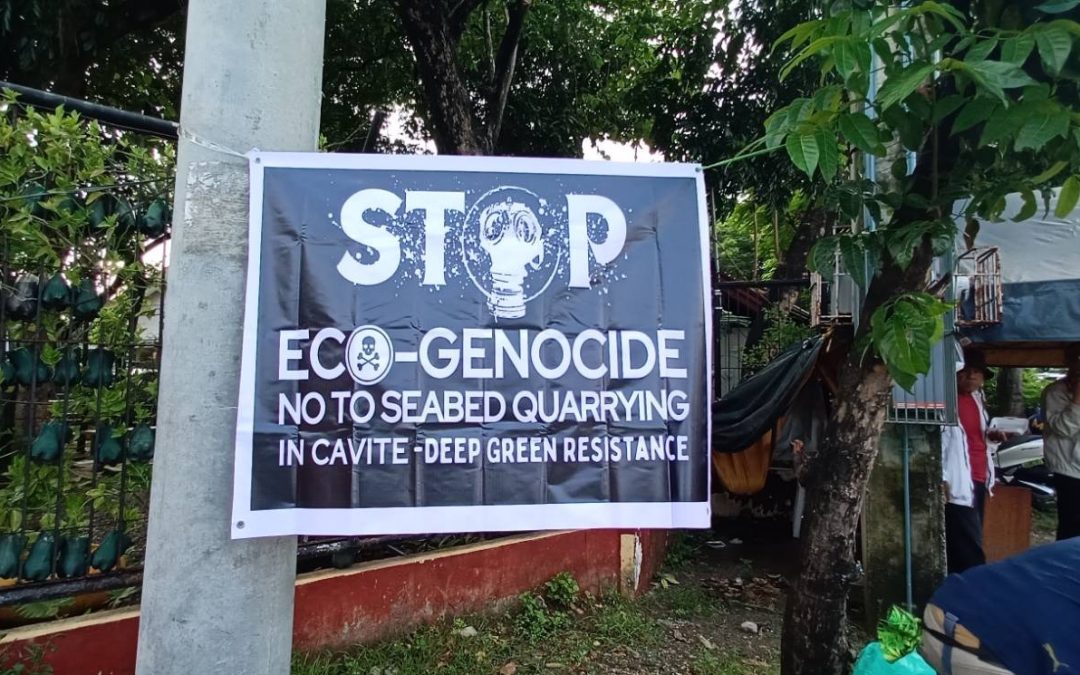

These reclamation projects include the 148-hectare Manila Solar City project and the contested Manila-Cavite Coastal Road and Reclamation Project (MCCRRP), which will encroach on Las Piñas-Parañaque Critical Habitat and Ecotourism Area (LPPCHEA), a Ramsar site that’s a key stopping point for migratory birds.

Banner image of the arrested activists in Manila who oppose the Manila Bay reclamation program. Image courtesy of Defend Negros Movement

![Against the Seabed Quarry in Manila [Statement]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/07/Seabed-Quarry-Tarp-scaled-e1690767078438-1080x675.jpg)