Featured image: the 1774 burning of the cargo ship Peggy Stewart, an escalation of the Boston Tea Party.

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Tactics and Targets” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

For me, nonviolence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon.

—Nelson Mandela

Deeds, not words!

—Slogan of the Women’s Social and Political Union

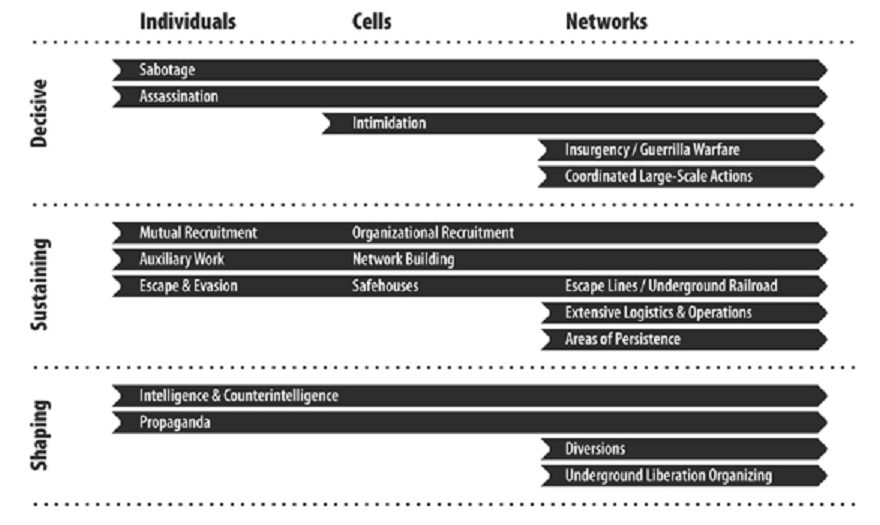

Recall that all operations—and hence all tactics—can be divided into three categories:

- Decisive operations, which directly accomplish the objective.

- Sustaining operations, which directly assist and support those carrying out decisive operations.

- Shaping operations, which help to create the conditions necessary for success.

Where tactics fall depends on the strategic goal. If the strategic goal is to be self-sufficient, then planting a garden may very well be a decisive operation, because it directly accomplishes the objective, or part of it. But if the strategic goal is bigger—say, stopping the destruction of the planet—then planting a garden cannot be considered a decisive operation, because it’s not the absence of gardens that is destroying the planet. It’s the presence of an omnicidal capitalist industrial system.

If one’s strategic goal is to dismantle that system, then one’s tactical categories would reflect that. The only decisive actions are those that directly accomplish that goal. Planting a garden—as wonderful and important as that may be—is not a decisive operation. It may be a shaping or sustaining operation under the right circumstances, but nothing about gardening will directly stop this culture from killing the planet, nor dismantle the hierarchical and exploitative systems that are causing this ecocide. Remember, the world used to be filled with indigenous societies which were sustainable and enduring. Their sustainability did not prevent civilization from decimating them again and again.

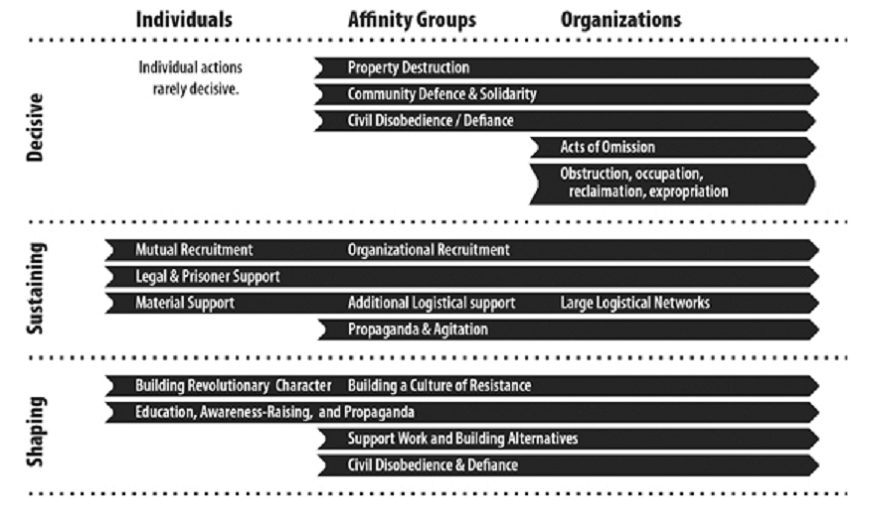

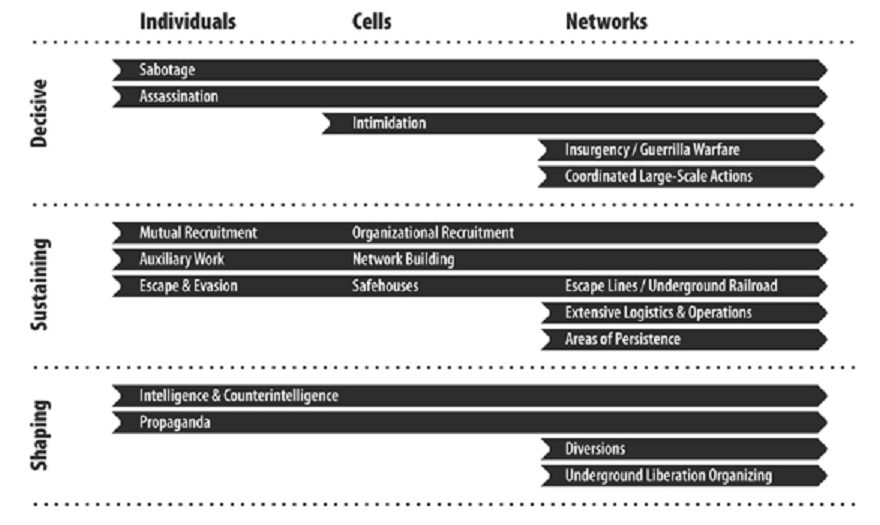

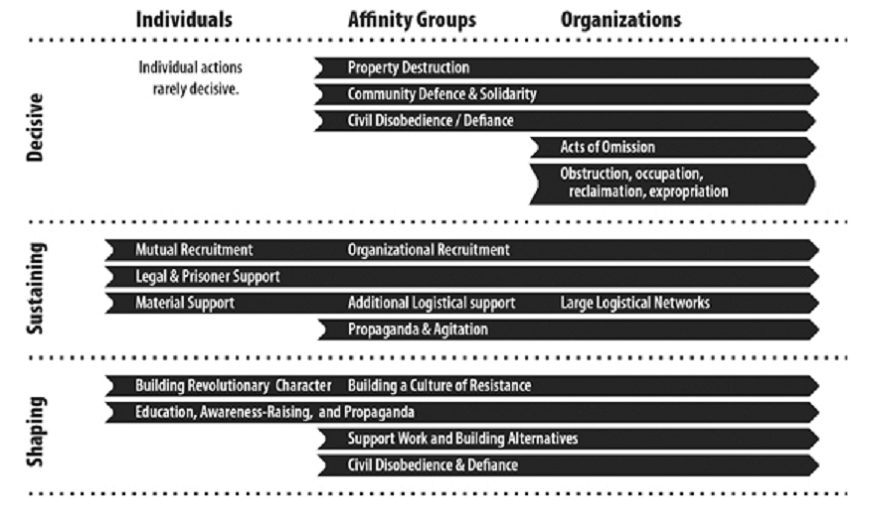

In this chapter we’ll break down aboveground and underground tactics into the three operational categories. For each class of operations, we’ll further break tactics down by scale for individuals, affinity groups, and larger organizations. This is summarized in Figures 13-1 and 13-2 below. As a rule, any tactic an individual can carry out can also be accomplished by a larger organization. So the tactics for each scale can nest into the next, like Russian matryoshka dolls.

Figure 13-1

Figure 13-2

Every resistance movement has certain basic activities it must carry out: things like supporting combatants, recruitment, and public education. These activities may be decisive, sustaining, or shaping, as shown in the illustration. And they may be carried out at different scales. Operations like education, awareness raising, and propaganda (shown under aboveground shaping) may occur across the range from the individual to large organizations. The scope of education may change as larger and larger groups take it on, but the basic activities are the same.

Other operations change as they are undertaken by larger groups and networks. Look in the underground tactics under sustaining. Individuals may use escape and evasion themselves, to start with. Once a cell is formed, they can actually run their own safehouse. And once cells form into networks, they can combine their safehouses to form escape lines or an entire Underground Railroad. The basic operation of escape and evasion evolves into a qualitatively different activity when taken on by larger networks. A similar dynamic is at work in recruitment; individuals are limited to mutual recruitment, but established groups can carry out organizational recruitment and training.

And, of course, some resistance units are too small to take on certain tasks, as we shall discuss. Individuals have few options for decisive action aboveground. Underground, they are limited in their sustaining operations, because secrecy demands that they limit contact with other actionists whom they could support. But once organizations become large enough, they can embrace new operations that would otherwise be out of their reach. Aboveground, large movements can use acts of omission like boycotts or they can occupy and reclaim land. And underground networks can use their spread for coordinated large-scale actions or even guerrilla warfare.

ABOVEGROUND TACTICS

Broadly speaking, aboveground tactics are those that can be carried out openly—in other words, where the gain in publicity or networking outweighs the risk of reprisals. Underground tactics, in contrast, are those where secrecy is needed to carry out the actions to avoid repression or simply to do the actions. The dividing line between underground and aboveground can move. Its position depends on two things: the social and political context, and the audacity of the resisters.

There have been times when sabotage and property destruction have been carried out openly. Conversely, there have been times when even basic education and organizing had to happen underground to avoid repression or reprisals. This means, explicitly, that when we use the term underground we do not necessarily mean acts of sabotage or violence: smuggling Jews out of Nazi Germany was an underground activity, and the Underground Railroad was by definition, er, underground. One of the most important jobs of radicals is to push actions across the line from underground to aboveground. That way, more people and larger organizations are able to use what was once a fringe tactic.1

Provoking open defiance of the laws or rules in question also impairs the ability of elites to exercise their power. The South African government, for example, was terrified that people of color in South Africa would simply stop obeying the law of the apartheid government. In even the most openly fascist state, the police force is still a minority of the population. If enough people disobey as part of their daily activities, then the country becomes ungovernable; there aren’t enough police to force everyone to perform their jobs at gunpoint.

When enough serious people have gathered to push a tactic back into the aboveground arena, those in power have few choices. If they continue to insist that the law be obeyed, resistance sympathizers may increasingly disregard any laws as dissidents begin to view the government as generally illegitimate—often a government’s worst nightmare. Or the government may offer concessions or change the law. Any of the above could be considered a victory. Usually governments strive to retain the image of control through selective concessions or legislation because the other road ends with civil unrest, revolution, or anarchy.

The cases of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X exemplifies how a strong militant faction can enhance the effectiveness of less militant tactics. In his book Pure Fire: Self-Defense as Activism in the Civil Rights Era, Christopher B. Strain explains that Martin Luther King Jr. pushed his agenda by using Malcolm X “to illustrate the alternative to legislative reform: chaos.… King would usually present the matter in terms of a choice: ‘We can deal with [the problem of second-class citizenship] now, or we can drive a seething humanity to a desperation it tried, asked, and hoped to avoid.’ … [He] suggested if white leaders failed to heed him ‘millions of Negroes, out of frustration and despair’ will ‘seek solace’ in Malcolm X, a development that ‘will lead inevitably to a frightening racial nightmare.’ ”2 But Strain emphasizes that King and Malcolm X were by no means enemies. “Despite their differing opinions, both men recognized that their brands of activism were complementary, serving to shore up the other’s weaknesses.”3

Some presume that Malcolm X’s “anger” was ineffective compared to King’s more “reasonable” and conciliatory position. That couldn’t be further from the truth. It was Malcolm X who made King’s demands seem eminently reasonable, by pushing the boundaries of what the status quo would consider extreme.

Pushing boundaries doesn’t have to involve underground property destruction or violence. Breaking antisegregation laws through lunch counter sit-ins, for example, pushed the limits of acceptability during the civil rights struggle. The second generation of suffragists, too, got tired of simply asking for what they wanted and started breaking the law. In both cases, the old guard activists were leery at first.

To be perfectly explicit: it isn’t just militants who can push the boundaries; even nonviolent groups can and should be pushing the envelope for militancy—vocally and through their actions—wherever and whenever possible. It’s hard to overstate the importance of this for any grand strategy of resistance. In this way, and many others, aboveground and underground activists are mutually supportive and work in tandem.

DECISIVE OPERATIONS ABOVEGROUND

Open property destruction is not always decisive. Take the Plowshares Movement activists, who break into military installations and use hammers and other tools to attack everything from soldiers’ personal firearms to live nuclear weapons, after which they wait and accept personal legal responsibility for their actions. There’s no doubt that this involves bravery—obviously it requires a lot of guts to take a sledgehammer to a hydrogen bomb—but these acts are not intended to be decisive. They are chiefly symbolic actions; neither the intent nor the effect of the action is to cause a measurable decrease in the military arsenal. (Presumably they could accomplish this if they really wanted to; anyone with the wherewithal to bypass military security and get within arm’s reach of a live nuclear warhead could probably do it more than once.)

In fact, open property destruction as a decisive aboveground tactic is historically rare. Remember, those in power view their property as being more important than the lives of those below them on civilization’s hierarchy. If large amounts of their property are being destroyed openly, they have few qualms about using violent retaliation. Because of this, situations where property can be destroyed openly tend to be very unstable. If those in power retaliate, the resistance movement either falters, shifts underground, or escalates. The Boston Tea Party is an excellent example. After the dumping of tea in December 1773, a boycott was imposed on British tea imports. In October 1774, the ship Peggy Stewart was caught attempting to breach the boycott while landing in Annapolis, Maryland. Protesters burned the ship to the waterline, a considerable escalation from the earlier dumping of tea. Within a year, mere property destruction segued into armed conflict and the Revolutionary War broke out.

Aboveground acts of omission are the more common tactical choice. An individual’s reduced consumption is not decisive, for reasons already discussed; in a society running short of finite resources like petroleum, well-meaning personal conservation may simply make supplies more available to those who would put them to the worst use, like militaries and corporate industry. But large-scale conservation could reduce the rate of damage slightly, and buy us more time to enact decisive operations, or, at least, when civilization does come down, leave us with slightly more of the world intact.

The expropriation or reclamation of land and materiel can be very effective decisive action when the numbers, strategy, and political situation are right. The Landless Workers Movement in Latin America has been highly successful at reclaiming “underutilized” land. Their large numbers (around two million people), proven strategy of reclaiming land, and political and legal framework in Brazil enable their strategy.

Many indigenous communities around the world engage in direct reoccupation and reclamation of land, especially after prolonged legal land claims, with mixed success. There are enough examples of success to suggest that direct reclamation can be successful, especially with wider support from both indigenous and settler communities. The specifics of conflicts like those at Kanehsatake and Oka, Caledonia, Gustafsen Lake, Ipperwash, and Wounded Knee (1973), are too varied to get into here. But it’s clear that indigenous land reclamations attack the root of the legitimacy—even the existence—of colonial states, which is why those in power respond so viciously to them, and why those struggles are so critical and pivotal for broader resistance in general.

SUSTAINING OPERATIONS ABOVEGROUND

Sustaining operations directly support resistance. For individuals aboveground, that means finding comrades through mutual recruitment or offering material or moral support to other groups. But individual mutual recruitment can be difficult (although this is easier if the recruiter in question is strongly driven, charismatic, well organized, persuasive, and so on). Affinity groups, with more people available to prospect, screen, and train new members, are able to recruit and enculturate very effectively. Individual recruiters have personality, but a group, even a small one, has a culture—hopefully a healthy culture of resistance.

Aboveground sustaining operations mostly revolve around solidarity, both moral and material. Legal and prisoner support are important ways of supporting direct action. So are other kinds of material support, fund raising, and logistical aid. The hard part is often building a relationship between supporters and combatants. There can be social and cultural barriers between supporters (say, settler solidarity activists) and those on the front lines (say, indigenous resisters). Indigenous activists may be tired of white people telling them how to defend themselves or perhaps simply wary of people whom they don’t know whether they should trust.

Propaganda and agitation supporting a particular campaign or struggle are other important sustaining actions. Liberation struggles like those in South Africa and Palestine have been defended internationally by vocal activists and organizers over decades. This propaganda has increased support for those struggles (both moral and material) and made it more difficult for those in power to repress resisters.

Larger organizations can undertake sustaining operations like fund raising and recruitment on a larger scale. They may also do a better job of training or enculturation. A single affinity group has many benefits, but can also be a bubble, a cultural fishbowl of people who come together because they believe the same thing. Being part of a larger network can mean that a new member gets a more well-rounded experience. Of course, the opposite can happen—dysfunctional large groups can quash ideological diversity. Often in “legitimate” groups that means quashing more radical, militant, or challenging beliefs in favor of an inoffensive liberal approach.

The converse problem is factionalism. There’s a difference between allowing internal dialogue and dissent, on one hand, and having acrimonious internal conflicts (like in the Black Panthers or the Students for a Democratic Society), on the other. The larger an organization is the harder it is to walk the line between unity and splintering (especially when the COINTELPRO types are trying hard to destroy any effective operation).

Larger organizations have a better capacity for sustaining operations (and decisive operations, for that matter) than individuals and small groups, but they rarely apply it effectively. Internal conflicts limit operations to the lowest common denominator: the lowest risk, the lowest level of internal controversy, and the lowest level of effectiveness. The big green and big leftist organizations will only go as far as holding press conferences and waving signs. Meanwhile, indigenous people who are struggling (often at gunpoint) to defend and reclaim their lands are ignored if they act outside the government land claims process. Tree sitters, even those who are avowedly nonviolent, get ignored by the big green organizations when police and loggers come in to attack them. The big organizations almost always fail to deploy their resources for sustaining operations when and where they are needed most. On a moral level, that’s deeply deplorable. On a strategic level, it’s unspeakably stupid. On a species and planetary level, it’s simply suicidal.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be that way. Effective resistance movements in history are usually composed of a cross section of many different organizations on many different scales, performing the different tasks best suited to them, and larger organizations are an important part of that. History has shown that it’s possible for large organizations to operate in solidarity and with foresight. Even if they don’t actually carry out decisive operations themselves, large aboveground organizations can offer incredibly important support.

SHAPING OPERATIONS ABOVEGROUND

Most day-to-day aboveground resistance actions are shaping operations of one kind or another. But many actions could be sustaining or shaping operations, depending on the context. Building a big straw-bale house out in the country would be considered a shaping operation if the house were built simply for the purpose of building a straw-bale house. But if that building were used as a retreat center for resistance training, it might then become part of sustaining operations. Consider the Black Panthers. A free breakfast program for children that was devoid of political content would have been a charity or perhaps mutual aid. A breakfast program integrated within a larger political strategy of education, agitation, and recruitment became a sustaining operation (as well as a threat to the state).

One of the most important shaping operations is building a culture of resistance. On an individual level, this might mean cultivating the revolutionary character—learning from resisters of the past, and turning their lessons into habits to gain the psychological and analytical tools needed for effective action. Building a culture of resistance goes hand in hand with education, awareness raising, and propaganda. It also ties into support work and building alternatives, especially concrete political and social alternatives to the status quo. As always, every action must be tied into the larger resistance strategy.

Most large organizations focus on shaping operations without making sure they are tied to a larger strategy. They try to raise awareness in the hopes that it will lead indirectly to change. This can be a fine choice if made deliberately and intelligently. But I think that most progressive organizations eschew decisive or sustaining operations because they simply don’t consider themselves to be resistance organizations; they identify strongly with those in power and with the culture that is destroying the planet. They keep trying to convince those in power to please change, and it doesn’t work, and they fail to adjust their tactics accordingly. The planet keeps dying, and people drop out of doing progressive work by the thousands, because it so often doesn’t work. We simply don’t have time for that anymore. We need a livable planet, and at this point a livable planet requires a resistance movement.